ABSTRACT

This paper looks at the mobilizing effect of personal networks on the individual propensity to favour some types of political participation over others, in a context of changing participation repertoires. We rely on original egocentric network data gathered via a unique online survey conducted among a quota sample of 2801 Belgian citizens. We show that dominant political behaviour(s) in a network diffuse as byproduct of social proximity and influence: the more someone has been exposed to a certain type of participation in the past, the more this person is likely to be recruited in the same type of participation in the future (engagement), or, if this person was already active, to retain the same participatory behaviour (retention). Moreover, our results point to a cross-over dissuasive effect across types of participation that keeps citizens away from certain participatory behaviours. In particular, exposure to online and instiutionalized participation in their personal network decreases respondents’ likelihood to engage in non-insitutionalized participation. Overall, we stress the added-value of a meso-level approach that embeds citizens in their personal network to understand their participatory choices.

Introduction

Political participation has faced major changes in the last decades (Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier Citation2010). Institutionalized types of participation such as associational and party memberships are in decline (Dalton and Wattenberg Citation2000; Marien and Quintelier Citation2011; van Haute, Paulis, and Sierens Citation2017) while non-institutionalized and online types of participation are expanding (Klingemann and Fuchs Citation1995; Norris Citation2002; Stolle, Hooghe, and Micheletti Citation2005; Gibson and Cantijoch Citation2013; Theocaris and van Deth Citation2018).

In this context, a central question for participation scholars is to explain how citizens make a choice and favour some types of political participation over others. However, the classic explanatory models developed in the literature heavily focus on the determinants of the intensity of participation in general rather than its nature, or of a specific type of participation. What is still largely missing, is a better understanding of how citizens make a choice within the action repertoire that is offered to them (Tilly Citation1993).

Furthermore, classic and more recent studies focus mainly on micro- and macro-level explanatory factors of political participation (Leighley Citation1995; Bäck, Teorell, and Westholm Citation2011; Hooghe and Marien Citation2012; Vrablikova Citation2014; Hooghe and Quintelier Citation2014; Quaranta Citation2018). In doing so, they contribute to a better understanding of who gets involved in politics, why, and under which opportunity structure. However, they do not shed much light on the process of political engagement and the triggers of participation, i.e. the factors that turn potential participators into politically active citizens. They fail to explain why, in a given macro context and facing an equal level of resources, some citizens engage in politics while others don’t. Investigating these dimensions calls for an analysis of the role of intermediate, meso-level factors, and especially the role of mobilization by social groups or agencies (Leighley Citation2008; Morales Citation2009; Campbell Citation2013). While the role of mobilizing agencies is somewhat better documented, the mobilizing effects of social groups and personal networks have only received passing attention (Zuckerman Citation2005; Lazer Citation2011; Rolfe Citation2013). Furthermore, group/network-based studies are mostly limited to electoral participation and how political discussion among peers influences the decision to vote or to take part in campaign activities (Beck Citation2002; McClurg Citation2003; Wolf, Morales, and Ikeda Citation2010; Bello Citation2012; Sinclair Citation2012; Lupton and Thornton Citation2017; Ladini, Mancosu, and Vezzoni Citation2018; Carlson, Abrajano, and Bedolla Citation2020). Interestingly, Galesic et al. (Citation2018) have demonstrated that asking about social circles is a better predictor of national election turnout and results than asking about personal intention. In the same vein, a recent innovative experimental study (Freden, Rheault, and Indridason Citation2020) has restated how much interpersonal networks matter for vote choices. Despite vivid scientific discussions about the relationship between networks and engagement in the electoral process, other types of political participation remain neglected. Similarly, how networks affect how citizens operate a choice between various types of participation (institutionalized vs. non-institutionalized vs. online) remain underexplored.

This paper intends to fill these gaps by looking at the mobilizing effect of personal networks on the individual propensity to favour some types of political participation over others. The underlying goal is to emphasize that, in politics – as in life more generally, individuals do not act in a social vacuum but in close relation to their close network of peers. Most political actions are collective by nature and political participation has a strong relational dynamic (Siegel Citation2009).

Exploring the association between citizens’ ‘real-life’ personal networks and their political engagement is particularly relevant today, in a world characterized by an increasing impact of social media. Indeed, while digital platforms have expanded participatory channels, enlarged individuals’ social network, and eased the interaction between them (Freden, Rheault, and Indridason Citation2020), their emergence has pushed participation scholars to re-evaluate ‘real-life’ dynamics of social influence through the lenses of network theory and analysis (Lazer Citation2011; Campbell Citation2013). Even more recently, the COVID crisis has also recalled the relevance of the online and offline interpersonal dynamics (Chamberlain Citation2020; Van Bavel, Baicker, and Boggio Citation2020).

This study uses a personal network perspective as main theoretical and methodological tool. We rely on a unique online survey conducted among a quota sample of 2801 Belgian citizens. We start by stressing the importance of adding a meso-level, personal network perspective to the study of political participation. We then present our data and methods that apply personal network empirical tools to survey methods. Finally, the results of our analyses are presented and discussed. We show how participatory habits and characteristics of citizens’ personal network predict their likelihood to engage in politics and their choice between different types of participation.

Political participation and the role of social networks

Political participation is a central field of research in political science. It has generated numerous debates and explanatory models. These models focus mainly on micro- and macro-level factors. Micro-level studies revolve around three main models: (1) the resources model, which emphasizes the role of socio-economic status and inequalities in participation (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Citation1995); (2) the socio-psychological model, which stresses the role of attitudes that favour participation; and (3) the rational choice model that highlights individual motivations behind participation (Olson Citation1965; Whiteley Citation1995; Bäck, Teorell, and Westholm Citation2011). Macro-level studies have partly looked at the political opportunity structure of participation (e.g. Norris Citation2002; Gallego Citation2008; Hooghe and Marien Citation2012; Dalton Citation2017). These studies focus on cultural, structural and institutional explanations shaping the ‘structures of opportunities for civic engagement’ (Norris Citation2002, 25).

These studies have contributed to our knowledge of who gets involved, why, and under which context. Yet they are not without shortcomings. Micro-level studies tend to consider individuals out of their social contexts as ‘atomized actors floating unanchored’ (Knoke Citation1990, 1058). Furthermore, they consider participation as an individual undertaking despite its often very collective nature (Leighley Citation1995; Lazer Citation2011). Lastly, ‘opportunities to participate are not equally or randomly distributed in the population’ (Leighley Citation2008, 46) and individual-level inequalities in participation may in fact reflect inequalities in participation opportunities, as shown by Rosenstone and Hansen (Citation1993).

If macro-level studies put individuals back into their context, they do not shed light on how the process works: How and when do political opportunities lead to actual participation? Under which circumstances do resources, attitudes, and motivations get turned into participatory behaviour? Answering these questions calls for an investigation of intermediate explanatory factors, and especially the role of mobilization by social groups or agencies. Yet these factors have largely been neglected in the literature.

Recently, the mobilizing effect of social relations has attracted a growing attention as a result of the increasing inter-connectedness of our modern societies. Most notably among the pioneers, Brady, Verba, and Schlozman (Citation1995) adapted their resources model to recognize mobilization as a crucial factor when they state that citizens who do not participate in politics do so either because they can’t (they lack the resources), because they don’t want to (they lack the mindset and motivation) or because nobody asked (they are isolated ‘from recruitment networks through which citizens are mobilized to politics’) (Citation1995, 271).

Two main sub-fields have contributed to the growing attention to these ‘network’ factors and their effect on political participation. First, sociologists have early on looked at the role of personal networks in the recruitment processes in non-electoral politics (e.g. Klandermans and Oegema Citation1987; Passy Citation2003; Diani and McAdam Citation2003). They underline that personal networks allow individuals to socialize, to be recruited, and thereby enhance their disposition to participate, but also to repeat their participation in social movements, protests, or radical activist groups (Schussman and Soule Citation2005; Saunders et al. Citation2012). These ‘network capitalists’ argue that social relationships are important as they give access to resources of various kinds (material, immaterial, instrumental, emotional, etc.). They can thus have consequences on various social and behavioural outcomes, such as political participation. Moreover, it has been shown that the structure formed by interpersonal relationships (network density, size, etc.) influences social and political collective action, as the relationships between individuals make them interdependent in their contributions to a common goal (Gould Citation1993; Siegel Citation2009).

Second, political communication and election studies have analysed individuals’ decision to engage in elections and campaigns as a by-product of the form and content of their social networks (Huckfeldt and Sprague Citation1987; Coleman Citation1988; Knoke Citation1990; La Due Lake and Huckfeldt Citation1998; Huckfeldt et al. Citation2000; Burt Citation2000; Putnam Citation2000; McClurg Citation2003; Zuckerman Citation2005; Sinclair Citation2012; Campbell Citation2013; Ahn, Huckfeldt, and Ryan Citation2014). Election studies have also looked at social networks through their analysis of campaign techniques, including canvassing, door-to-door, get-out-to-vote initiatives, or the role of opinion leaders and mobilizing agencies (e.g. Rosenstone and Hansen Citation1993; Gerber and Green Citation2000a, Citation2000b).

However, these studies are limited to electoral participation and how ‘networks’ of political discussion among peers influence the decision to vote, vote choice, or the probability to take part in election campaign activities (like donations). Few researchers have extended this framework to other types of political participation, or to the analysis of the choice between types of participation.

This paper fills these gaps and looks at the mobilizing effect of personal networks on the individual decision to participate politically and the choice between types of political engagement. More specifically, it analyses how individuals turn into types of politically active citizens and the role that the ‘others’ play in that process. To do so, it mobilizes the literature on behavioural diffusion in social network analysis (SNA) (Valente Citation1995; Rogers Citation2003) applied to participatory behaviours. We argue that individuals’ personal networks and the characteristics of these networks play a decisive role. We assume that, in their personal networks, citizens (ego) get stimulus from other relevant agents (alters), and that these may influence the way ego behaves. As stimulus, we focus on the type of participation that alters are engaged in, and on their social and political profile.

From network diffusion theories, we can expect that the exposure to participation stimuli matters. The more agents are exposed to a (political) behaviour in their proximate environment, the more they will be pushed to adopt the same (political) behaviour. This is known as the ‘exposure’ effect. Depending on how much someone is exposed to politically active agents, ‘networks may increase individual chances to become involved, and strengthen activists’ attempts to further the appeal of their causes’ (Diani Citation2004, 339). Exposure to peers’ political engagement is shown particularly relevant to explain mobilization processes in social movements, sects, clubs or any kind of voluntary associations (Diani and McAdam Citation2003), but also in politics and political groups (Beck Citation2002; McClurg Citation2003; Zuckerman Citation2005; Sinclair Citation2012; Morisi and Plescia Citation2018). Nickerson (Citation2008) finds a contagion effect in his study that shows that voting intentions and voting choices are viral within households, using a field experiment with a ‘get out the vote’ mailing as the treatment. In another field experiment, Sinclair (Citation2012) supports the same finding, but finds out that it does not diffuse to other households. In the same vein, Fowler (Citation2005) stresses that a modest degree of contagion can cause a chain reaction which, in turn, substantially raises aggregate voter turnout. He estimates that one person’s decision to vote can affect up to four other individuals. Similarly, Siegel (Citation2009) simulates the structure of social networks and shows that network ties channel civic participation. Therefore, when alters are themselves already committed to some type(s) of political participation, they can then stimulate ego’s probability to engage in the same type of political activities as a result of peer-pressure and mimicking behaviour. Without ignoring the tricky causal relationship between the exposure to participation and the individual behavioural output (McAdam and Paulsen Citation1993), we follow the theoretical direction put forward by a substantial amount of research. Hence, we hypothesize that the higher ego’s exposure to a specific type of political participation in his/her social network, the higher ego’s likelihood to engage in the same type political participation (H1).

Exposure to a specific type of political participation can not only have an effect on ego’s likelihood of engaging in that type of participation, but it can also have a cross-over effect on ego’s likelihood to engage in other types of political participation. This is a consequence of the normative power of social networks, which has been shown particularly salient for citizens’ voting duty (Gerber, Green, and Larimer Citation2010) or for humanitarian actions (Roblain et al. Citation2020). Through interpersonal relations, civic norms are imprinted and citizens develop an internalized sense of civic duty (Campbell Citation2013). A network where institutionalized participation is the norm in terms of political behaviour can push ego to perceive non-institutionalized participation as the ‘wrong’ participatory behaviour to adopt, and conversely. Furthermore, at the individual level, Dalton (Citation2008) has shown that different sets of norms lead to different types of political participaiton. Hence, we expect that the higher ego’s exposure to institutionalized participation in his/her social network, the lower ego’s likelihood to engage in non-institutionalized participation, and vice-versa (H2).

Finally, the overall composition of personal networks matters as well when considering political action (Knoke Citation1990; Zuckerman Citation2005). We know that individual socio-demographic characteristics and political attitudes are crucial determinants of political participation and types of participation at the individual level (Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier Citation2010). In the same way, the social and political profiles of alters in the network play a significant role too, providing ego’s individual attributes a social dimension (Campbell Citation2013). For instance, it is shown that education acts as a status-sorting mechanism within social networks for some types of participation (Persson Citation2015), while exposure to people with greater political knowledge conducts to higher levels of political involvement (Campbell Citation2013). Furthermore, there is evidence that social networks contribute to reinforce social and political inequalities inherent to politics, rather than overcome them. Party organization studies have shown that the homogeneous composition of party members’ networks in terms of attitudes and socio-demographics prevents parties from reaching other profiles than the ‘usual suspects’ (i.e. male, older, educated, interested, etc.) thereby explaining their recruitment shortage in certain social categories (Paulis Citation2019). Hence, we expect that the higher ego’s exposure to alters who have high levels of social and political resources in his/her social network, the higher ego’s likelihood to engage in institutionalized participation (H3a). Conversely, it is acknowledged that the youth and women are underepresented in party-based participation while more prone to unconventional politics (Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier Citation2010). Hence, we expect that the higher ego’s exposure to alters who have low levels of social and political resources in his/her social network, the higher ego’s likelihood to engage in non-institutionalized participation (H3b). Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier (Citation2010) suggested nonetheless that non-institutionalized types of participation strongly reduce or even reverse gender and age inequalities but increase patterns of inequality due to education. From that, we may expect to see a slightly different pattern for gender/age and education, especially when related to non-institutionalized participation.

Data and methods

Data

The survey method is a common technique to collect and generate data on personal networks (Bernard et al. Citation1990; Marsden Citation1990; Crossley Citation2015; Perry, Pescosolido, and Borgatti Citation2018) and political participation (Gibson and Cantijoch Citation2013; Vrablikova Citation2014). Therefore, in order to get insight into the mobilizing effect of personal networks on the individuals’ decision to participate politically, we rely on a unique online survey conducted via Qualtrics, which is both a software and a platform that provides panels of online survey respondents. Our online survey was conducted between June and July 2016 among a quota sample of 2801 Belgian citizens (quotas based on region, age and gender) retrieved from Qualtrics’ panels. The sample offers a good representation of the population, with a slight underrepresentation of younger respondents (). The survey was administered in Dutch and French and conducted in-between electoral cycles to minimize the impact of additional external stimulus on participatory behaviours.

Table 1. Representativeness of the Sample.

Measurement and description of the dependent variable

Over time, surveys have extended questions related to participatory behaviours, from asking about voting and party-related activities, to non-institutionalized types of political activities like protest, boycott or petitioning (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Citation1995; Norris Citation2002; Vrablikova Citation2014), and more recently, online types of political engagement (social media like/following, etc.) (Gibson and Cantijoch Citation2013). Our questionnaire included items relating to these three types of participation (institutionalized, non-institutionalized, and online), which are now extensively covered by most comparative political surveys. We followed the wording of the European Social Survey Programme (ESS8-2016, B15-22) and adapted it in order to measure both the past and future participatory behaviours of our respondents.

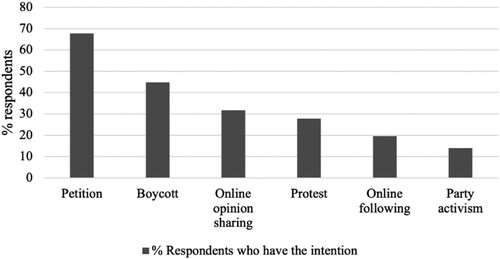

Our main dependent variable measures the respondent’s intention to engage in political participation (ego’s participation intention). We focus on ego’s intention to participate, so that alters’ participation in the past can be assumed to precede and predict ego’s future intention to participate. We measured this intention with following question: ‘Could you please indicate whether it is likely or not that you will engage in the following activities in the future?’ (likely/not likely): (1) sign a petition (paper or online); (2) take part in a protest or public meeting; (3) boycott or buy on purpose specific products for political, ethical or environmental reasons; (4) be active for a party and/or a candidate; (5) like or become friend with a candidate or a party on social media (FB or Twitter); (6) give or share political opinions online (on social media or traditional media websites). Note that voting was not included as an item, as voting is compulsory in Belgium. As far as the distribution for each political activity is concerned, emphasizes that petition and boycott were the two most selected items among prospective participants, whereas party activism attracted much less intention.

All in all, 77.5% of our sample reported an intention to participate in (at least one) political activity. This figure indicates a relatively high proportion of prospective participants. We ran a principal component analysis (PCA)Footnote1 bound to three dimensions that match the three types of activities identified in the literature and existing surveys: non-institutionalized activities (petition, protest and boycott), online activities (online following, opinion sharing), and institutionalized activities (party activism). These three dimensions of intention to participate were then used as our three (continuous) dependent variables in the analyses.

Part of these prospective participants were already politically active at the time of the survey (70.5% of the respondents reported to have undertaken at least one activity within the year preceding the survey, see the distribution per types of activity in Appendix 1). Our analyses therefore control for the respondents’ past participatory behaviours (see our modelling strategy below). This allows to assess to what extent personal networks are a mobilizing factor for inactive citizens (recruitment), but also a factor that affects the intention to continue being active (retention), and contribute to the debate on novices and repeaters (Saunders et al. Citation2012).

Measurement and description of the independent variables

In social networks analysis, there are two ways to measure an individual’s network. The personal (egocentric) network approach looks at one individual (ego) and its direct personal network, such as family, neighbours, colleagues, etc. (alters), as opposed to the whole (sociocentric) approach that looks at the entire relational structure of bounded groups. In this study, we focus on personal networks even if we acknowledge that a respondent’s personal network is only a part of sets of relationships (Hâncean, Molina, and Lubbers Citation2016). Personal network data can easily be collected via quantitative survey designs (Crossley Citation2015). The most frequent technique is to ask respondents (1) to raise a list of names of people who satisfy a certain definition of a social relationship (name-generater), (2) to collect information about these people (name-interepreter) and (3) to inform how they are tied to each other (name-interrelater). Personal network data have been collected through surveys since the beginning of the 1960s (e.g. Wellman Citation1979; Laumann Citation1973) and were systematized in the 1980s. Burt (Citation1984) was the first to include questions documenting personal networks in the US General Social and Election Surveys. Since then, the technique has been widely developed and accepted, also in online settings (Manfreda, Vehovar, and Hlebec Citation2014; Crossley Citation2015; Eagle and Proeschold-Bell Citation2015; Perry, Pescosolido, and Borgatti Citation2018).

In order to measure our respondents’ personal network, we included a name-generating procedure in our survey. The first step asked our respondents to list the first names of a maximum of ten individuals who they consider important in their social life and regularly interacted with over the last year (name-generator). This treshold was set to map ego’s proximate network of ‘significant others’ (Burt Citation1984; Bidart and Charbonneau Citation2011; Crossley Citation2015; Lin Citation2001), i.e. individuals with the greatest impact on ego’s political attitudes and behaviours. Network studies estimate that ego discusses important matters with less than a dozen people (Degenne and Forsé Citation1994) and naming between 5 and 10 alters was demonstrated to be enough to capture the network of significant others (Kogovsek and Hlebec Citation2019; Merluzzi and Burt Citation2013). Furthermore, any increase in the number of alters to be mentioned by ego increases the cognitive burden of filling in the questionnaire, especially for online surveys more prone to dropout (Ferligoj and Hlebec Citation1999; Manfreda, Vehovar, and Hlebec Citation2014; Marin and Hampton Citation2007; Marsden Citation2011).

Our dataset excludes respondents who did not mention any personal network, as well as invalid mentions (typos rather than names) (N = 99). reports the distribution of our sample on the number of alters reported by the respondents. On average, respondents report 6.2 alters, i.e. important persons with whom they have interacted in the last year. Only 14.1% of the sample named only one alter, and more than a third mentioned 10 names. While this upper threshold might be seen as a limitation, we argue that it is a good tradeoff between getting an estimate of respondents’ proximate network and getting them to provide reliable information about that proximate network. The central explanatory factors in this study are these information about the alters, rather than the structural properties of the personal network (which are only included as control variables).

Table 2. Size of Respondents’ Personal Network.

The second step of the name generating procedure asked respondents to report the type of social relations that links them with these alters. We also asked respondents to report social and political characteristics about these alters, using the same questions asked for ego. We focused on information that respondents were most likely to know and left aside other predictors of participation to minimize false reporting, biases of social projection and subjectivity (Crossley Citation2015; Aeby Citation2016). While some of these biases may remain, network scholars have stressed that social influence is not always driven by real and accurate knowledge of what alters do politically, but rather by subjective and normative perceptions (Gerber and Rogers Citation2009). Hence, we assume that information reported by respondents for their personal network, real or biased, work as cognitive heuristics which orientate respondents’ own future behaviours.

In order to test our first two hypotheses (H1 and H2), we measured ego’s exposure to a specific type of political participation in their personal network. In the survey, respondents were asked ‘Could you indicate if the members of your social network have engaged in the following activities in the last 12 months?’ (Yes/No/Don’t know): (1) signed a petition (paper or online); (2) taken part in a protest or public meeting; (3) boycotted or bought on purpose specific products for political, ethical or environmental reasons; (4) been active for a party and/or a candidate; (5) liked or became friend with a candidate or a party on social media (FB or Twitter); (6) gave or shared political opinions online (on social media or traditional media websites).

Our first set of independent variables, exposures to alters’ participation, measure the proportion of alters who have engaged in each political activity (N of alters engaged in the activity in relation to total N of alters). We have computed a rate of exposure that ranges from 0 (no alter engaged in the political activity) to 100 (all alters engaged in the political activity).

When looking at the mean exposure rates presented in , the rank order of frequency of political activities is identical than the one presented for ego (). Petitioning is the political act that our respondents are the most exposed to through their alters (34.1%). It means that, for a network of 10 alters, on average at least three of them are reported to have undertaken this specific activity. It is followed by boycott (22.6%), online opinion sharing (19.8%) and protest (18.7%). Respondents are less exposed to party-based activities like online or offline party activism, as the lower mean exposure rates in suggests. This is not surprising since this type of participation is more time-consuming and is therefore less undertook by citizens, translating into lower proportion of both egos and alters active in party-based activities (see the distribution in Appendix 1). Furthermore, party-based participation is overall in decline (Van Biezen, Mair, and Poguntke Citation2012), while citizens increasingly engage in non-institutionalized types of participation (Norris Citation2002; Hooghe, Oser, and Marien Citation2016; Quaranta Citation2018; Portos, Bosi, and Zamponi Citation2020). Overall, respondents report lower levels of political participation for their alters than for themselves. This may reveal that social desirability weights heavier on the respondents’ self-reporting than on their reporting of their alters’ participation, or that some of the respondents are not fully informed of their alters’ participatory behaviours.

Table 3. Mean Exposure to Alters’ Participation, in %.

Like for the dependent variable, we ran a principal component analysis (PCA)Footnote2 on the six political activities with the three fixed factors. It allows us to compute our three independent variables, measuring exposure to three types of political activities: non-institutionalized activities (petition, protest and boycott), online activities (online following, opinion sharing), and institutionalized activities (party activism). In addition, since about a third of the respondents (951 out of 2801) reported none of their alters as engaged in political activities, we computed an additional independent variable, exposure to political apathy, which takes the value of 1 if all the alters are politically inactive, and 0 if not.

The third hypothesis (H3a and H3b) requires to measure the social and political profile of alters. Therefore, our second set of independent variables focuses on the characteristics of the alters, and more specifically their socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender and education) and their reported attitudes towards politics (political interest and party identification). We concentrate on exposure rates to ‘high’ levels of socio-demographic and attitudinal predispositions that are known to increase the odds of institutionalized participation at the individual level (Van Haute and Gauja Citation2015; Campbell Citation2013). Therefore, we dichotomized alters’ socio-demographic characteristics to oppose lower and higher levels of resources among alters, to test H3.

introduces alters’ characteristics, measured as the proportion of alters in the respondent’s network who are reported to have these predispositions towards insitutionalized politics (N of alters with the characteristics in relation to the total N of alters). As the table shows, the networks of our respondents are quite well distributed across gender, age and education. The mean values suggest that a half of the network is male, older than 45 and holds a high school or university degree. In terms of political attitudes, the average proportion of alters that are perceived as politically interested or as identifying with a party is around 40%. It means that, if someone has named 10 alters, (s)he reports on average 4 of them as politically interested and/or identified with a party. The distribution plots of these variables (Appendix 2) display more variation, meaning that the social and political characteristics of ego’s network differs across individuals.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for Alters’ Characteristics.

Finally, the last step of our name-generating procedure gave the respondents the opportunity to report in a matrix box whether their alters knew each other (name-interrelater). From that information, an index of network density was computed by dividing the number of actual connections within the network by the number of potential connections. It ranges from 0 (for a network where none of the alters know each other) to 1 (all alters know each other).

The mean value of the density index is 0.5 (SD = .34), suggesting that on average one in two alters in our respondents’ personal network know each other. It is not surprising given the nature of the personal networks that are measured (significant others). The distribution shown in underlines that density varies from one personal network to another. In this study, density is used as control variable in the analyses. For larger networks the number of ties is usually preferred to density, as density is highly affected by the network size (Crossley Citation2015). However, in our case the difference is limited given the limited size of ego networks.

Table 5. Density of Respondents’ Personal Network.

Modelling strategy

We used a network analysis software to compute our network measures, exposure to alters’ participation and socio-demographic characteristics (independent vairables) and network size and density (control variables). Then, we estimated their effect on ego’s intention to participate through a multilinear regression model run in Stata. Our model predicts the likelihood of a respondent’s likelihood of undertaking the three participation types. The model first introduces the independent variables that relates to exposure to alters’ participation types (H1 & H2) and then those related to alters’ social and political profile (H3a & b). Finally, we control for ego’s past participatory behaviours, network size and density, as well as other individual predictors of participation (age, gender, education, political interest, political satisfaction and party identification, all measured for ego (see the Appendix 5 for the operationalization and the summary statistics). In addition, we ran the same analysis using a split sample to test our results across two groups of participants: respondents who are currently inactive but report an intention to participate in the future (recruitment of novices), and respondents who were already politically active and intend to continue being active in the future (retention of repeaters). This allows us to differentiate the recruitment vs. retention power of personal networks.

Multivariate analyses

presents the outcomes of the models. A first interesting result is the relatively high R square when only including the personal network variables, especially for non-institutinalized (17.5%) and online (15.1%) participation. The predictive power of the personal network characteristics is lower for institutionalized participation (4.5%). It means that the (reported) participatory habits and social and political characteristics of alters is a good predictor of ego’s likelihood to engage in political activities, especially for non-institutionalized and online activities. Galesic (2008) had emphasized the role of personal networks on vote choices. Our analysis suggests that this finding extends to other types of political participation as well.

Table 6. Explaining Ego’s Intention to Participate.

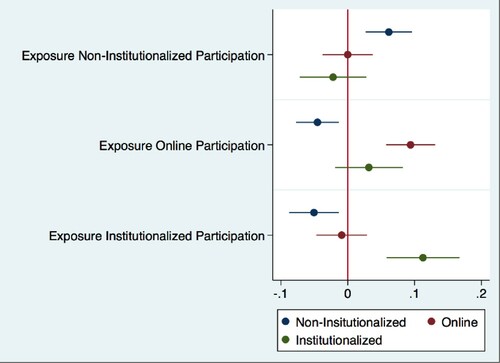

The results support our first expectation across the three participation types: the higher the exposure to one type of political participation, the higher ego’s intention to engage in that same type of political participation (H1 supported). It is true for all types of participation (non-institutionalized, online, and institutionalized). In other words, personal networks contribute to a dynamics where citizens consider opting for political behaviours that match their networks’ behaviours. The larger the proportion of alters engaged in one type of political activity, the higher ego’s intention to behave similarly and engage in the same type of political activity in the future. This suggests that dominant political behaviour(s) in a network diffuse within the network as by product of social influence. Networks act as triggers of mobilization. Previous studies had emphasized this trigger effect of networks (Diani Citation2004; McClurg Citation2003; Sinclair Citation2012). What our study adds is evidence of mimicking behaviours leading ego to favour some types of participation over others, thereby contributing to a better understanding of how individuals operate a choice among an action repertoire.

When controlling for ego’s current level of participation, network size and density, and other individual predictors, the effect of exposure to alters’ participation remains stable and significant. It means that, controlling for ego’s current level of political engagement in all three types of political activities, being exposed to alters who are actively engaged in a specific type of participation is related to a higher intention for ego to engage in the same type of activity in the future. The effect is even reinforced for ego’s intention to engage in institutionalized participation (higher regression coefficient in the full model with controls). We find a similar effect for non-participation: exposure to a fully inactive network significantly decreases ego’s intention to participate politically in all three types of activities, although it remains statistically significant only for non-institutionalized participation once the control variables are included in the model. This is probably due to the correlation between political apathy and socio-demographic characteristics.

Beyond the direct effect of exposure by type of participation, the results plotted in stress further cross-over effects across types of participation, as expected by H2. Exposure to institutionalized and online participation decreases ego’s intention to take part in non-institutionalized participation, and this holds when controlling for individual factors. However, we found no evidence that the relationship works in the other direction: exposure to non-institutionalized participation does not affect intentions to engage in institutionalized or online participation. Moreover, the exposure to institutionalized and online participation are both positively related to each other, albeit not in a significant way after introducing control variables. This is probably because the cumulative cross-over effect is not only present in ego’s personal network, but also in ego’s current participatory behaviours, the control variables capturing the main effect. The close connection and cumulative effect between institutionalized and online participation may be due to the fact that one of the item measuring online participation is highly party oriented. Overall, our findings confirm a normative ‘dissuasive’ power of personal networks (Roblain et al. Citation2020) that keeps ego away from certain participatory behaviours, but only in one direction: exposure to institutionalized and online participation decreases ego’s likelihood to be active in non-institutionalized politics, but not vice-versa. This means that H2 is only partially supported. These findings complement Dalton’s research (Citation2008) on citizenship norms and participation and studies on the cumulative aspect of participation (Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier Citation2010), by showing the role of meso-level, network factors in these dynamics.

Figure 2. Regression Plots of the Main Model. Note: control variables included and 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

Our second set of independent variables, i.e. the exposure to alters’ social and political characteristics, have overall a weak effect on ego’s intention to participate. Furthermore, the effects do not go in the expected direction, with exposure to resources being linked to a higher likelihood to engage in institutionalized participation (H3a) and a lower likelihood to engage in non-institutionalized participation (H3b). Rather, social and political resources of alters play in different ways. The social composition of ego’s network mostly affects ego’s intention to engage in non-institutionalized participation: being exposed to a network that is more female and better educated slightly increases ego’s likelihood of engaging in non-institutionalized participation, even when control variables are included. The positive relationship between gender and non-institutionalized participation has been shown at the individual level (Marien et al. Citation2010; Memoli Citation2016); our study confirms it at the group level, further substantiating the idea that non-institutionalized politics is favourable to female involvement and reduces gender inequalities inherent to political participation. Similarly, our study confirms the positive relationship between education and non-institutionalized participation (Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier Citation2010) at the group level. Furthermore, we find that the exposure to older alters slightly decreases ego’s online participation, even when controlling for individual factors. Our study confirms the digital divide when it comes to age and online politics.

Finally, the political composition of ego’s network also matters for ego’s intention to engage in political activities. Being exposed to politically interested alters increases ego’s likelihood to engage in non-institutionalized and online activities (but it is not significant once the controls are included); being exposed to party identifiers increases ego’s likelihood to engage in institutionalized politics (even with controls). Exposure to alters’ party identification negatively impacts non-insitutionalized participation and is positively related to online participation, but the effects do not remain significant when the controls are included. Overall, alters’ partisanship matters more than their level of politicla interest, and it reinforces institutionalized participation but deters from non-institutionalized participation, thereby operating in a similar way as exposure to institutionalized politics.

Regarding our control variables, interestingly we can see from the full model in Appendix 3 that people already engaged in institutionalized politics are less likely to continue in the future. This result stresses a major retention issue faced by most political parties, as already emphasized at the individual level by Pettitt (Citation2020).

Robustness check

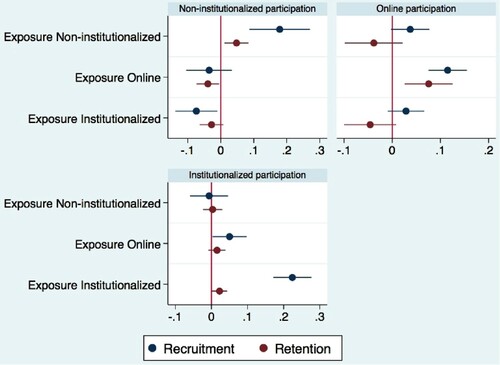

was plotted on the basis of the outcomes of the split sample model (see Appendix 4). It gives support to the three following findings.

Figure 3. Regression Plots of the Split Sample Multivariate Analysis. Note: control variables included and 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

The positive effect of exposure to alters’ participation is statistically significant for the recruitment and the retention of ego in all three types of participation. It means that alters’ participation acts as a trigger for being newly recruited in the same political activities, but also favours retention of ego’s engagement in these political activities. Interestingly, this robustness check systematically shows a much stronger effect of exposure to alters’ participation on ego’s recruitment (blue dots) than on their retention (red dots). This is especially the case for insitutionalized participation. Exposure to alters’ institutionalized participation plays less in explaining ego’s continuing intention to participate in institutionalized politics. It means that even with a personal network engaged in institutionalized politics, a respondent who is already engaged in this type of participation is more difficult to retain. It highlights retention difficulties for parties and can bring new insights into the debate on membership decline (Pettitt Citation2020).

We also find additional support for the cross-over effects. The plots show that exposure to institutionalized participation decreases above all the recruitment in non-institutionalized politics, and to a lesser extent retention in non-institutionalized an online participation. Exposure to (non)-institutionalized participation decreases mostly the retention in online participation. And finally, exposure to online participation increases recruitment in institutionalized politics and vice-versa, although these relationships do not hold for retention. It means that being exposed to alters who share political opinions and support parties and candidates online increases ego’s likelihood to become active in a party offline. This is in line with other studies showing a spillover effect between online and offline spheres (Conroy, Feezell, and Guerrero Citation2012; Gil de Zúñiga, Jung, and Valenzuela Citation2012; Vissers and Stolle Citation2014; Lane et al. Citation2017). Overall, these findings point to the importance of distinguishing between first-time participants and repeaters, as already pointed by Saunders et al. (Citation2012) for protest participation.

Finally, the magnitude of the effect of exposure to alters’ characteristics is not more substantial when the sample is splitted. It nonetheless supports the two observations made earlier: exposure to male alters decreases ego’s likelihood of retention in non-institutionalized politics, whereas exposure to higher education categories increases the recruitment in non-institutionalized politics. Additionally, we find that exposure to alters who feel close to a party positively affects only the propensity to be recruited in institutionalized politics, but not retention.

Conclusion

This paper looked at the mobilizing effect of personal networks on the individual propensity to favour some types of political participation over others. Theoretically, the paper fills a gap in the literature that tends to focus on explaining the intensity rather than the nature of participatory behaviours. It also offers a much-needed focus on the role of personal networks to complement micro- and macro-level approaches. Empirically, the paper relies on original personal network data gathered via a unique online survey conducted among a quota sample of 2801 Belgian citizens.

Our analyses point to four main findings. First, our results confirm the interest of adopting a personal network approach to political participation. The participatory habits and, to a lesser extent, the social and political characteristics of alters are good predictors of ego’s likelihood ito engage in political activities, and so across the three types of participation considered in the study. It validates the interest of a meso-level perspective that focuses on personal networks.

Second, our results confirm that the higher the exposure to one type of political participation, the higher ego’s intention to engage in that same type of political participation. It is true for all types of participation, even when distinguishing between newly recruited participants and those who are retained. In other words, citizens consider opting for political behaviour(s) that match their networks’ behaviours, pointing to a process of diffusion as byproduct of social proximity and influence. Networks act as triggers of mobilization but also matter for the retention of participants.

Third, our findings also point to cross-over effects across types of participation. We emphasize a normative ‘dissuasive’ power of personal networks that keeps citizens away from certain participatory behaviours. The most robust cross-effect goes in the following direction: citizens who are surrounded by alters engaged in the two other types of participation are pushed away from non-institutionalized participation. Additionnally, we show that exposure to institutionalized participation negatively affects the recruitment in non-institutionalized activities, whereas exposure to online participation affects retention the most.

Finally, we show that the social composition of ego’s network affects ego’s intention to engage in non-institutionalized participation. Being integrated in a network with more women and alters with higher levels of education increases the likelihood of ego’s participation in non-institutionalized activities. We show that alters’ gender impacts retention, while education affects recruitment in non-insitutionalized politics. Moreover, older personal networks are related to lower likelihood of online participation, stressing a digital divide. We thus substantiate at the group level prior findings found at the individual level. The political composition of the network affects ego’s intention to engage in institutionalized participation: exposure to party identifiers favours institutionalized participation, and above all the recruitment of new participants in this type of participation.

Interestingly, our study points toward major retention issues for political parties. It sheds light on the potential reasons behind the decline in institutionalized participation: social reproduction leads to homogeneous networks that make renewal difficult. At the same time, our findings also point to potential solutions to these difficulties. For example, online strategies could be an avenue to revitilize institutionalized politics, as exposure to alters’ online participation positively affects citizens’ intention to be active in a party.

More largely, we show that the way people participate in politics is not determined in a social vacuum but depends strongly on what proximate, significant others are and do. In doing so, the paper extends the existing knowledge in two directions. First, it provides a better understanding of how citizens make a choice within the action repertoire that is offered to them, of how they favour some types of political participation over others. Second, it contributes to explaining why, in a given macro context and facing an equal level of resources, some citizens (continue to) engage in politics while others won’t. It highlights the importance of personal networks as triggers of participation, i.e. the factors that turn potential participators into politically active citizens. It also points to boosters of retention, i.e. factors that encourage already active citizens to renew their political engagement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = .742; Chi-Square (15) = 2221.067, p = .000. Total variance explained: 69.3%.

2 Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = .820; Chi-Square (15) = 3941,482, p = .000. Total variance explained: 74.6%.

References

- Aeby, G. 2016. Who are my people? Strengths and limitations of ego-centered network analysis: A case illustration from the Family tiMes survey. FORS Working Paper Series, paper 2016-2.

- Ahn, T., R. Huckfeldt, and J. Ryan. 2014. Experts, Activists, and Democratic Politics Are Electorates Self-Educating? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bäck, H., J. Teorell, and A. Westholm. 2011. “Explaining Modes of Participation: A Dynamic Test of Alternative Rational Choice Models.” Scandinavian Political Studies 34 (1): 74–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00262.x

- Beck, P. 2002. “Encouraging Political Defection: The Role of Personal Discussion Networks in Partisan Desertions to the Opposition Party and Perot Votes in 1992.” Political Behavior 24 (4): 309–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022549726887

- Bello, J. 2012. “The Dark Side of Disagreement? Revisiting the Effect of Disagreement on Political Participation.” Electoral Studies 31 (4): 782–795. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.004

- Bernard, R., E. Johnsen, P. Killworth, C. McCarty, G. Shelley, and S. Robinson. 1990. “Comparing Four Different Methods for Measuring Personal Social Networks.” Social Networks 12 (3): 179–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(90)90005-T

- Bidart, C., and J. Charbonneau. 2011. “How to Generate Personal Networks: Issues and Tools for a Sociological Perspective.” Field Methods 23 (3): 266–286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X11408513

- Brady, H. E., S. Verba, and K. L. Schlozman. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” American Political Science Review 89 (2): 271–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2082425

- Burt, R. 1984. “Network Items and the General Social Survey.” Social Networks 6 (4): 293–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(84)90007-8

- Burt, R. 2000. “The Network Structure of Social Capital.” Research in Organizational Behavior 22: 345–423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(00)22009-1

- Campbell, D. 2013. “Social Networks and Political Participation.” Annual Review of Political Science 16: 33–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-033011-201728

- Carlson, L., M. Abrajano, and T. Bedolla. 2020. Talking Politics: Political Discussion Networks and the New American Electorate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chamberlain, J. 2020. Coronavirus has revealed the power of social networks in a crisis. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-has-revealed-the-power-of-social-networks-in-a-crisis-136431.

- Coleman, J. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94: 95–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Conroy, M., J. T. Feezell, and M. Guerrero. 2012. “Facebook and Political Engagement: A Study of Online Political Group Membership and Offline Political Engagement.” Computers in Human Behavior 28 (5): 1535–1546. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.012

- Crossley, N. 2015. Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets. London: Sage.

- Dalton, R. S. 2008. “Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation.” Political Studies 56: 76–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

- Dalton, R. S. 2017. The Participation Gap. Social Status and Political Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R., and M. P. Wattenberg. 2000. Parties Without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Degenne, A., and M. Forsé. 1994. Les Réseaux Sociaux. Paris: Armand Colin. (1ère édition).

- Diani, M. 2004. “Networks and Participation.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by D. Snow, S. Soule, and H. P. Kriesi, 339–359. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Diani, M., and D. McAdam. 2003. Social Movements and Networks. Relational Approaches to Collective Action. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Eagle, D., and R. Proeschold-Bell. 2015. “Methodological Considerations in the Use of Name Generators and Interpreters.” Social Networks 40: 75–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2014.07.005

- Ferligoj, A., and V. Hlebec. 1999. “Evaluation of Social Network Measurement Instruments.” Social Networks 21 (2): 111–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(99)00007-6

- Fowler, J. 2005. “Turnout in a Small World.” In The Social Logic of Politics, edited by A. Zuckerman, 269–288. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Freden, A., L. Rheault, and I. Indridason. 2020. “Betting on the Underdog: The Influence of Social Networks on Vote Choice.” Political Science Research and Methods. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.21

- Galesic, M., W. Bruine De Bruin, M. Dumas, A. Kapteyn, J. E. Darling, and E. Meijer. 2018. “Asking About Social Circles Improves Election Predictions.” Nature Human Behaviour 2: 187–193.

- Gallego, A. 2008. “Unequal Political Participation in Europe.” International Journal of Sociology 37 (4): 10–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/IJS0020-7659370401

- Gerber, A. S., and D. P. Green. 2000a. “The Effect of a Nonpartisan Get-Out-The-Vote Drive: An Experimental Study of Leafleting.” The Journal of Politics 62: 846–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00035

- Gerber, A. S., and D. P. Green. 2000b. “The Effects of Canvassing. Telephone Calls. and Direct Mail on Voter Turnout: A Field Experiment.” American Political Science Review 94: 653–663. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2585837

- Gerber, A. S., D. P. Green, and C. Larimer. 2010. “An Experiment Testing the Relative Effectiveness of Encouraging Voter Participation by Inducing Feelings of Pride or Shame.” Political Behavior 32: 409–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9110-4

- Gerber, A. S., and T. Rogers. 2009. “Descriptive Social Norms and Motivation to Vote: Everybody’s Voting and so Should You.” The Journal of Politics 71 (1): 178–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608090117

- Gibson, R., and M. Cantijoch. 2013. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Participation in the Age of the Internet: Is Online Political Engagement Really Different to Offline?” The Journal of Politics 75 (3): 701–716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000431

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., N. Jung, and S. Valenzuela. 2012. “Social Media Use for News and Individuals’ Social Capital, Civic Engagement and Political Participation.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17 (3): 319–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x

- Gould, R. 1993. “Collective Action and Network Structure.” American Sociological Review 58 (2): 182–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2095965

- Hâncean, M.-G., J. L. Molina, and M. J. Lubbers . 2016. “Recent Advancements, Developments and Applications of Personal Network Analysis.” International Review of Social Research 6 (4): 137–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/irsr-2016-0017

- Hooghe, M., and S. Marien. 2012. “A Comparative Analysis of the Relation Between Political Trust and Forms of Political Participation in Europe.” European Societies 15 (1): 131–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2012.692807

- Hooghe, M., J. Oser, and S. Marien. 2016. “A Comparative Analysis of ‘Good Citizenship’: A Latent Class Analysis of Adolescents’ Citizenship Norms in 38 Countries.” International Political Science Review 37 (1): 115–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114541562

- Hooghe, M., and E. Quintelier. 2014. “Political Participation in European Countries. The Effect of Authoritarian Rule, Corruption, Lack of Good Governance and Economic Downturn.” Comparative European Politics 12 (2): 209–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2013.3

- Huckfeldt, R., and J. Sprague. 1987. “Networks in Social Context: The Social Flow of Political Information.” American Political Science Review 81: 1197–1216. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1962585

- Huckfeldt, R., J. Sprague, and J. Levine. 2000. “The Dynamics of Collective Deliberation in the 1996 Election: Campaign Effects on Accessibility, Certainty, and Accuracy.” American Political Science Review 94 (3): 641–651. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2585836

- Klandermans, B., and D. Oegema. 1987. “Potentials, Networks, Motivations, and Barriers: Steps Towards Participation in Social Movements.” American Sociological Review 52 (4): 519–531. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2095297

- Klingemann, H.-D., and D. Fuchs. 1995. Citizens and the State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Knoke, D. 1990. Political Networks. The Structural Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kogovsek, T., and V. Hlebec. 2019. “Measuring Personal Networks with Surveys.” Metodoloski Zvezki 16 (2): 41–55.

- La Due Lake, R., and R. Huckfeldt. 1998. “Social Capital, Social Networks, and Political Participation.” Political Psychology 19 (3): 567–584. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00118

- Ladini, R., M. Mancosu, and C. Vezzoni. 2018. “Electoral Participation, Disagreement, and Diversity in Social Networks: A Matter of Intimacy?”. Communication Research 47 (7): 1056–1078.

- Lane, D. S., D. H. Kim, S. S. Lee, B. E. Weeks, and N. Kwak. 2017. From Online Disagreement to Offline Action: How Diverse Motivations for Using Social Media Can Increase Political Information Sharing and Catalyze Offline Political Participation. Social Media+Society.

- Laumann, E. 1973. Bounds of Pluralism: The Forms and Substance of Urban Social Networks. New York: Wiley.

- Lazer, D. 2011. “Networks in Political Science: Back to the Future.” PS: Political Science and Politics 44 (1): 61–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096510001873

- Leighley, J. 1995. “Attitudes, Opportunities and Incentives: A Field Essay on Political Participation.” Political Research Quarterly 48 (1): 181–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299504800111

- Leighley, J. 2008. “Commentary on ‘Attitudes. Opportunities and Incentives: A Field Essay on Political Participation’.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (1): 46–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907311890

- Lin, N. 2001. “The Position Generator: Measurement Techniques for Investigations of Social Capital.” In Social Capital: Theory and Research, edited by N. Lin, K. Cook, and R. Burt, 57–81. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Lupton, R., and J. Thornton. 2017. “Disagreement, Diversity, and Participation: Examining the Properties of Several Measures of Political Discussion Network Characteristics.” Political Behavior 39 (3): 585–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9371-7

- Manfreda, K., V. Vehovar, and V. Hlebec. 2014. “Collecting Ego-Centred Network Data via the Web.” Metodološki Zvezki 1 (2): 295–321.

- Marien, S., M. Hooghe, and E. Quintelier. 2010. “Inequalities in Non-institutionalised Political Participation : A Multi-Level Analysis of 25 Countries.” Political Studies 58: 187–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

- Marien, S., and E. Quintelier. 2011. “Trends in Party Membership in Europe. Investigation Into the Reasons for Declining Party Membership.” In Party Membership in Europe: Exploration Into the Anthills of Party Politics, edited by E. van Haute, 34–60. Brussels: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

- Marin, A., and K. Hampton. 2007. “Simplifying the Personal Network Name Generator. Alternatives to Traditional Multiple and Single Name Generators.” Field Methods 19 (2): 163–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X06298588

- Marsden, P. 1990. “Network Data and Measurement.” Annual Review of Sociology 16 (1): 435–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.002251

- Marsden, P. 2011. “Survey Methods for Network Data.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis, edited by J. Scott, and P. Carrington, 370–388. London: Sage.

- McAdam, D., and R. Paulsen. 1993. “Specifying the Relationship Between Social Ties and Activism.” The American Journal of Sociology 99 (3): 640–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/230319

- McClurg, S. 2003. “Social Networks and Political Participation: The Role of Social Interaction in Explaining Political Participation.” Political Research Quarterly 56 (4): 448–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290305600407

- Memoli, V. 2016. “Unconventional Participation in Time of Crisis: How Ideology Shapes Citizens’ Political Actions.” The Open Journal of Sociopolitical Studies 9 (1): 127–151.

- Merluzzi, J., and R. Burt. 2013. “How Many Names are Enough? Identifying Network Effects with the Least Set of Listed Contacts.” Social Networks 35 (3): 331–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2013.03.004

- Morales, L. 2009. Joining Political Organisations: Institutions, Mobilisation and Participation in Western Democracies. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Morisi, D., and C. Plescia. 2018. “Learning from the Other Side: How Social Networks Influence Turnout in a Referendum Campaign.” Italian Political Science Review 48 (2): 155–175.

- Nickerson, D. 2008. “Is Voting Contagious? Evidence from Two Field Experiments.” American Political Science Review 102: 49–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055408080039

- Norris, P. 2002. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press.

- Passy, F. 2003. “Social Networks Matter. But How?” In Social Movements and Networks. Relational Approaches to Collective Action, edited by M. Diani, and D. McAdam, 21–47. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Paulis, E. 2019. “What’s Going Around? A Social Network Explanation of Youth Party Membership.” Intergenerational Justice Review 5 (1): 9–24.

- Perry, B., B. Pescosolido, and S. Borgatti. 2018. Egocentric Network Analysis. Foundations, Methods and Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Persson, M. 2015. “Social Network Position Mediates the Effect of Education on Active Political Party Membership.” Party Politics 220 (5): 724–739. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812453368

- Pettitt, R. 2020. Recruiting and Retaining Party Activists. Lodon: Palgrave.

- Portos, M., L. Bosi, and L. Zamponi. 2020. “Life Beyond the Ballot Box: The Political Participation and Non-Participation of Electoral Abstainers.” European Societies 22 (2): 231–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2019.1610785

- Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Quaranta, M. 2018. “Repertoires of Political Participation: Macroeconomic Conditions, Socioeconomic Resources, and Participation Gaps in Europe.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 59 (4): 319–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715218800526

- Roblain, A., M. Hanioti Kokkoli, E. Paulis, and E. van Haute. 2020. “The Social Network of Solidarity With Migrants : The Role of Perceived Injuctive Norms on Intergroup Helping Behaviors.” European Journal of Social Psychology 50 (6): 1306–1317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2700

- Rogers, E. 1962/1971/1983/1995/2003. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

- Rolfe, M. 2013. Voter Turnout: A Social Theory of Political Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenstone, S. J., and J. M. Hansen. 1993. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: MacMillan.

- Saunders, C., M. Grasso, C. Olcese, E. Rainsford, and C. Rootes. 2012. “Explaining Differential Protest Participation: Novices, Returners, Repeaters, and Stalwarts.” An International Quarterly 17 (3): 263–280.

- Schussman, A., and S. A. Soule. 2005. “Process and Protest: Accounting for Individual Protest Participation.” Social Forces 84 (2): 1083–1108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0034

- Siegel, D. A. 2009. “Social Networks and Collective Action.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 122–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00361.x

- Sinclair, B. 2012. The Social Citizen. Peer Networks and Political Behavior. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Stolle, D., M. Hooghe, and M. Micheletti. 2005. “Politics in the Supermarket: Political Consumerism as a Form of Political Participation.” International Political Science Review 26 (3): 245–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105053784

- Theocaris, Y., and J. van Deth. 2018. “The Continuous Expansion of Citizen Participation: A New Taxonomy.” European Political Science Review 10 (11): 139–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773916000230

- Tilly, C. 1993. “Contentious Repertoires in Great Britain, 1758-1834.” Social Science History 17 (2): 253–280.

- Valente, T. 1995. Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations. Cresskil: Hampton Press.

- Van Bavel, J., K. Baicker, P. Boggio, et al. 2020. “Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response.” Nature Human Behaviour 4: 460–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

- Van Biezen, I., P. Mair, and T. Poguntke. 2012. “Going, Going … Gone? The Decline of Party Membership in Contemporary Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 51 (1): 24–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01995.x

- Van Haute, E., and A. Gauja. 2015. Party Members and Activists. London: Routledge.

- van Haute, E., E. Paulis, and V. Sierens. 2017. “Assessing Party Membership Figures: The MAPP Dataset.” European Political Science 17 (3): 366–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-016-0098-z

- Vissers, S., and D. Stolle. 2014. “Spill-Over Effects Between Facebook and On/Offline Political Participation? Evidence from a Two-Wave Panel Study.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11 (3): 259–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.888383

- Vrablikova, K. 2014. “How Context Matters? Mobilization, Political Opportunity Structures, and Non-Electoral Political Participation in Old and New Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (2): 203–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013488538

- Wellman, B. 1979. “The Community Question: The Intimate Networks of East Yorkers.” American Journal of Sociology 84 (5): 1201–1231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/226906

- Whiteley, P. 1995. “Rational Choice and Political Participation. Evaluating the Debate.” Political Research Quarterly 48 (1): 211–213.

- Wolf, M., L. Morales, and K. Ikeda. 2010. Political Discussion in Modern Democracies: A Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Zuckerman, A. 2005. The Social Logics of Politics. Personal Networks as Contexts for Political Behaviour. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.