ABSTRACT

In the present study, we analyze the relationship between domestic and international online publicity and individual outcomes of suspects in three recent politically salient cases in Russia. The analysis is based on the data from Telegram – one of the most politically relevant online platforms in contemporary Russia, – Google News and data about individual criminal cases. We find that international online publicity is associated with decreased likelihood of imprisonment for individual suspects, while the relationship between the latter and domestic publicity is less straightforward. Our findings contribute to the scholarship on the connection between (online) publicity and political repression relevant for Russia and, potentially, other autocracies.

Introduction

In the present study, we focus on three recent criminal cases with high political salience in Russia – an authoritarian state with repressive judicial system (Van der Vet Citation2018). Repressive legislation in the country is passed swiftly but its application is unpredictable (Gel’man Citation2016) with politicians and high-ranking officials being able to influence judges’ decisions – a practice known as ‘telephone law' (Van der Vet Citation2018; Sakwa Citation2010). This makes Russia a suitable case study in the context of the relationship between political repression by legal means and publicity. Since the judges can be influenced by the state, the outcomes of legal cases can also be determined by the state rather than by the judges. This way, the judicial system of the country serves as a political repression mechanism. In the present paper, we test the relationship between online publicity – domestic and international, as proxied by Telegram (domestic) and Google News (international) – and the outcomes of individual cases in politically salient criminal cases in Russia. Though the focus of the present study is on the case studies from Russia, it is possible that our findings are applicable to other authoritarian states that employ legal means to repress the dissenters such as China or Turkey.

State repression and publicity

Scholars coming from different subfields of social science do not always agree on the definition of political repression. In this paper, we broadly understand political repression as ‘repressive actions directed at individuals and groups based on their current or potential participation in non-institutional efforts for social, cultural or political change' (Earl Citation2011, 262). Repression can take many different forms (Tilly Citation1978); however, we focus specifically on one – arrests of dissidents by the state.

Domestic publicity

According to the rational choice literature, in order to decide whether to resort to repression or not, political actors make a rational cost–benefit calculation that includes four major factors: costs, benefits, the likelihood of success and availability of options other than repression (e.g. Duvall and Stohl Citation1983; Pierskalla Citation2010; Davenport Citation2007; Walter Citation1972; Moore Citation2000). In this logic, the state resorts to repression when it is perceived as the optimal choice in a given situation.

In terms of the potential costs of repressive actions, publicity is an important factor. State repression that does not attract a lot of attention is less costly than one that does. Publicity increases the cost of repression but does not necessarily deter the state from using it. Wide publicity about repressive actions can be used by the state strategically in order to scare the public and increase the perceived costs of challenging the regime (Bak, Sriyai, and Meserve Citation2018).

Still, wide domestic publicity about state repression can help public mobilization against the repressive regime as collective action is facilitated by the diffusion of information regarding the government’s activities and weaknesses (Tilly Citation1978). In this respect, online resources and social media are particularly useful as they dramatically increase the public’s access to information, including about the government’s activities, especially in the regimes with non-free media (Christensen and Garfias Citation2018; Ruijgrok Citation2017). As the examples of the Arab Spring, Gezi Park protests in Turkey, and Euromaidan in Ukraine show, social media can tremendously aid protest mobilization through the circulation of information about repressive actions of the state (Lawrence Citation2013; Leshchenko Citation2014; Odabaş and Reynolds-Stenson Citation2018).

Information about repression to be shared among domestic audiences might also be desirable for the government. That is the case when the government expects state violence to ‘cause significant fear among potential dissidents and increase subjective costs of anti-regime movements' (Bak, Sriyai, and Meserve Citation2018, 4). In this case, the regime might welcome domestic publicity about state repression to signal to the public that the state is powerful and able to control potential dissent (Huang Citation2015). However, there is evidence that contemporary autocrats tend to try to conceal state repression as they aim not to be feared but rather loved by the public (Guriev and Treisman Citation2018).

Potential domestic publicity can thus either deter the state from repression or encourage to engage in it, depending on the perceived influence of the publicity on the domestic audiences. If the state expects that circulation of information about repression will lead to mass anti-regime mobilization, it might evaluate the cost of repression as too high for a specific purpose. On the contrary, if the state expects that publicity will scare the audiences and discourage them from protesting, it will go forward with the repressions and, possibly, even facilitate the spread of information about them.

International publicity

While domestic publicity is important, in consolidated autocratic regimes dissidents do not always have enough resources to stand against their government alone. They thus might reach out to the international audiences to attract attention to the abusive actions of the authoritarian state and encourage foreign actors to engage in naming and shaming of the state for the human rights violations. International solidarity can both mobilize domestic audiences and put external pressure on an abusive government (Bak, Sriyai, and Meserve Citation2018).

Intuitively, international naming and shaming should deter the governments from repression since it can have negative consequences for a state such as damaging a state’s reputation and undermining its soft power (Nye Citation2013) or inciting sanctions against the abusive state leading to reduced foreign aid (Lebovic and Voeten Citation2009) and hampered state exports (Peterson, Murdie, and Asal Citation2018). Empirical evidence on the effects of naming and shaming on repression is, however, mixed. It leads to decreased repression in states that have strong economic connections to other countries (Franklin Citation2008) and decreases the likelihood of atrocities (Krain Citation2012) yet its effect varies across different forms of repression (Hafner-Burton Citation2008) and regime types (Hendrix and Wong Citation2013) leading to decreases in repression in some cases and having no effect or even increasing the level of repression in others.

The effects of both, domestic publicity and international naming and shaming, are highly contextual. The findings about these effects on specific cases of political repression are not generalizable across different regimes and forms of repression. However, the examination of such individual cases can shed light on the effects of publicity on repression in specific contexts and inform both, the broader field of studies on the interconnections between repression and publicity, and research that focuses on the politics of a given country. In the context of Russia specifically given the repressive nature of the judicial system and the fact that the courts’ decisions can be influenced by high-ranking officials, lawyers themselves have mentioned that wide publicity – or the lack of it – can influence the outcomes of the criminal cases (Van der Vet Citation2018), though this was not empirically tested before. Further, even though an extant body of research has examined the relationship between domestic and international publicity and political repression on an aggregate level, little has been done in terms of examining this relationship on a micro level – i.e. examining the connection between publicity about specific individuals and the outcomes of the cases against them. With this in mind, in the present paper, we focus on a several cases of political repression in Russia, namely the so-called ‘Moscow case' (Moskovskoie Delo) of 2019, the ‘New Greatness' (Novoe Velichie) case and ‘the Network’ case (Delo Seti), and examine the relationship between domestic and international publicity (media naming and shaming) and the outcomes of the cases of individual suspects in the aforementioned cases. In the next section we outline the research questions, then present background information, provide details on the data and methodology, and finally describe and discuss the results.

Research questions

As previous research shows that the effects of publicity on repression are highly contextual, we opted for examining explorative research questions about the relationship between publicity and repression rather than formulating concrete hypotheses.

We are interested in both, domestic and international publicity, and its association with the outcomes of the cases of individual suspects in three politically salient criminal cases in Russia. Specifically, we examine the following research questions:

RQ1: Is there a relationship between the level of domestic online publicity about a suspect and the final decision on their criminal case and, if so, what is the direction of the relationship?

RQ2: Is there a relationship between the level of international online publicity about a suspect and the final decision on their criminal case and, if so, what is the direction of the relationship?

We explore whether increased levels of domestic and/or international publicity about a specific suspect are associated with increased or decreased likelihood that a suspect is going to be sentenced to a real jail term resulting in a binary outcome variable: fulfilled (imprisonment) or unfulfilled (all other outcomes) repression against a suspect. With an acquittal rate in criminal cases of just 0.25% (Carroll Citation2019) in Russia, a case that goes to court usually ends with a conviction, which is particularly true for politically salient trials. Contemporary Russian legal system is characterized as repressive (Ledeneva Citation2013; Hendley Citation2015) with the judges being ‘unable or unwilling to stand up to powerful interests in cases with political and/or economic salience' (Hendley Citation2015). For this reason, we treat suspended sentences and fines as de facto cases of ‘unfulfilled repression'. That being said, this should be regarded as ‘unfulfilled repression’ at a particular point in time only, as suspended sentences might at a later point be reconsidered and turned into real sentences thus turning into ‘fulfilled repression'. Similarly, we treat cases in which suspects were released before trial as ‘unfulfilled repression'. In total, we examine 41 cases of individual suspects in three politically salient criminal cases, 21 of which received real sentences. We omitted the cases of the suspects who fled Russia.

Background

The three criminal cases that we examine in the present study are different in the nature of criminal charges. What unites them is that they are all politically salient: the cases have attracted major attention from politically interested groups in Russia, and the prominent Russian human rights group Memorial officially recognizes the sentenced suspects in all three cases as political prisoners (Memorial Citation2019). While we cannot state with confidence that these cases were initiated with political interests in mind, we argue that regardless of that they became politically salient, which made their outcomes relevant in the context of political repression. Due to the high salience of the cases, the state could use them to demonstrate its power to the public and thus induce fear among potential dissidents (Bak, Sriyai, and Meserve Citation2018). Alternatively, increased salience of the cases and publicity around them could raise potential perceived costs of repression for the state and deter it from repression. Thus, the high political salience of the cases in question makes them relevant in the context of the analysis conducted in this study. In addition, we analyze only cases with several suspects thus not including politically salient cases with single suspects (e.g. the case of Svetlana Davydova). The decision to focus on group cases only is motivated by the specifics of our research questions: we are interested in the situations where people facing identical or very similar charges received different decisions on their cases, and in the relationship between publicity and the differences in the outcomes. Further, we stick to the cases that were opened against regular citizens, not higher-profile opposition figures such as Aleksey Naval’nyy (Navalny) and Lyubov’ Sobol’. We suggest that with such highly visible and prominent opposition figures, the decisions are likely made in a logic very different from that applied to regular citizens, thus making cases of Navalny or Sobol’ incomparable to the ones discussed. Finally, we focused on the cases that occurred in recent years. As we highlight in the overview of previous research, the relationship between publicity and repression is highly contextual. We thus assume that this relationship might have changed over the years, hence we conclude that in the context of the present analysis it is best to focus on the cases that took place recently, roughly at the same time. Below, we briefly outline each of the cases in question.

The Moscow case

In July 2019, following the exclusion of independent candidates from the Moscow legislature elections to be held in September, peaceful protests began in Moscow. The response from the authorities was brutal, with mass detentions and numerous cases of police violence against the peaceful protesters (Oliynyk Citation2019). Following the protests, several criminal cases against the protesters were opened, and in July–November 2019, 25 people were arrested on the charges of ‘mass rioting’ and/or assaulting police. Several groups, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have decried the arrests saying that the charges are ungrounded (Human Rights Watch Citation2019; Amnesty International Citation2019), and even in the cases where protesters might have committed infractions, the sentences were excessive (Human Rights Watch Citation2019).

The New Greatness

In December 2017, 10 residents of the Moscow region were charged with creating an extremist group (Article 282.1 of the Russian Penal Code) ‘New Greatness', allegedly for the purposes of the violent overthrow of the government and constitutional order of Russia. They met online, on a Telegram chat, in 2017 and were discussing a wide range of topics, some of them political. At some point, a user referred to as ‘Ruslan D.' joined the group. He tried to direct the conversation to political topics and suggested writing a manifest for the ‘organization' that he named the ‘New Greatness'. Later Ruslan D. became the only witness against the other members of the group chat, and the written manifest that he suggested drafting was the major piece of evidence against them. Journalists suspect that Ruslan D. was a member of Russian law enforcement agencies (likely – security service, FSB), and the case thus was fabricated by the FSB. This point of view is shared by the Memorial human rights group (“The Members of New Greatness Are Political Prisoners, Memorial Says|Human Rights Center MEMORIAL” Citationn.d.). In August 2020, the suspects in the case received their sentences. All of them were convicted with some receiving suspended sentences while others received real terms ranging from 6 to 7 years in prison.

The Network

The Network allegedly was a terrorist organization in several Russian cities including Penza and St. Petersburg. The alleged members of the Network were arrested in 2017 and charged with terrorism. They were convicted in February 2020 receiving sentences ranging from 6 to 18 years in prison. According to human rights groups, including Amnesty International, the alleged organization never existed (“Russia: Prosecution for Membership of a Non-Existent ‘Terrorist’ Organization Must Stop” Citationn.d.). Amnesty International has also expressed concern regarding the alleged ill-treatment and torture of the suspected by Russian law enforcement agencies to force them to ‘confess' (Prilutskaya Citationn.d.).

Data and methods

Data

We have combined several data sources: information about the suspects in the three cases and data on the levels of domestic and international publicity about each of them. Information about the suspects included the dates of arrests, dates of decisions on the cases (i.e. trials or dates when suspects were released pre-trial), and the final decisions on the cases. The final decisions were coded along the following categories: fined/released (pre-trial)/suspended sentence/real sentence. Those were then recoded to a binary variable (fulfilled repression for real sentences, unfulfilled repression for everything else).

Data on domestic publicity

To assess the intensity of domestic publicity about each of the suspects, we used data collected from the Telegram messaging platform. There are several reasons for using Telegram data in this case. In general, Russia has a non-free media system being on 149th place out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 World Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders Citation2020). Since Russian mainstream media are subject to state censorship, they are unlikely to publish politically sensitive information, such as news about repression in general and politically salient criminal cases in particular. In such a media environment, mentions of the three cases by mainstream media cannot be used as a proxy of the general level of domestic publicity since they are likely to underrepresent the actual level of attention. Of course, there also exist independent media such as Mediazona or Meduza. However, we would argue that these media are used more by opposition-minded citizens rather than by the general public, and some such media as Mediazona are specifically focused on criminal cases in Russia. Thus mentions in these media do not necessarily reflect the level of general publicity about criminal cases. Telegram, on the other hand, is used by high shares of the Russian population, including opposition-leaning, pro-government and apolitical users. The platform is not subject to censorship and offers privacy-enhancing features aimed at protecting users’ identities (Urman and Katz Citation2020). For this reason, it is widely popular with Russians and is actively being used for the dissemination of political information in Russia by a number of ideologically different actors (Akbari and Gabdulhakov Citation2019; Salikov Citation2019). These include independent media, journalists and bloggers (i.e. Mediazona and Stalingulag), state media and state media journalists (i.e. Russia Today, Vladimir Solov’yev and Margarita Simon’yan), human rights organizations (i.e. OVD-Info), oppositional politiciants (i.e. Aleksey Navalny and Lyubov’ Sobol’) and even Russian political elites (i.e. Natal’ya Poklonskaya and Ramzan Kadyrov). For this reason, we suggest that Telegram data can serve as a reliable proxy of general domestic publicity in Russia about politically sensitive events.

Telegram is primarily a messaging platform but its channels feature allows using the platform for information dissemination. Channels are public feeds which can be created by anyone while remaining anonymous. However, only specific users (channel administrators) can post to a given channel. Other users can access a channel and messages posted to it (unless it is private in which case only users with a specific link can access the channel’s content) and subscribe to a channel to regularly receive the updates from it in the form of messages. On public channels, one can also see the number of views for each message. This data is openly available to all registered users of Telegram. We included the data from 2341 Russian public Telegram channels that focus on news and politics. The data was collected using Telegram’s open API and Telethon Python library (Exo Citation2020). Following Urman and Katz (Citation2020), we used Exponential Discriminative Snowball sampling (Goodman Citation1961; Biernacki and Waldorf Citation1981; Baltar and Brunet Citation2012). With the aim to collect an ideologically balanced sample of Russian Telegram channels, we started with two channels as the initial seeds, one that can be classified as pro-regime (the channel of the Russian state propagandist Vladimir Solov’yev), and one that can be classified as anti-regime (the channel of Stalingulag blogger who advocates anti-regime views). These specific channels were chosen because at the time of the start of the data collection (December 2019) they had the highest number of subscribers among the Russian political Telegram channels (according to Tgstat.com website). For each of the two channels, we collected all their messages and then performed the following procedure: first, we extracted mentions of other channels from the collected messages for a given channel, and then collected the messages from the channel that was mentioned most often. In the next step, we collected the messages from the channel that was most mentioned by the first and the second channels combined. Then the same procedure was repeated for every next channel collected.

The collected channels were continuously updated and new messages were collected until 31 August 2020, after the trials concerning all the suspects were finished. Out of the collected corpus, we then selected all the messages from these channels that mention suspects in one of the three cases. First, we compiled the lists of all the first and last names of the suspects in Cyrillic script, including the name forms in different grammatical cases as well as the short forms of the first names (i.e. for Aleksey Minyaylo we used Aleksey [Алексей] as well as Lesha [Леша] and Lyosha [Лёша]). We used both, first name + last name and last name + first name combinations. However, we did not include the messages that mentioned only the last names to avoid inconsistencies: some suspects have uncommon last names (i.e. Minyaylo), others have common last names (i.e. Zhukov) which could include messages about other topics. Using only combinations of first and last names means that some mentions of the suspects were omitted. However, we find that this is not a major problem as we used consistent filtering for all the suspects regardless of how common their last names are thus gauging the general levels of publicity about each in a comparable manner.

As a second filtering step, for each suspect, we selected only the messages that were posted between the day a suspect was arrested and the day when the final decision on their case (i.e. during a court trial) was made. This was necessary in order to filter out the messages that either are not related to the case (i.e. those posted before a suspect’s arrest and deal with the other activities of a given suspect) or could not have influenced the outcome of the case (i.e. those posted after the final decision on the trial was made).Footnote1 In the end, we used the messages from 2341 Russian-speaking Telegram channels each of which has mentioned one of the suspects at least once.

Data on international publicity

In order to assess the levels of international publicity, we collected the data on the mentions of each suspect by foreign news media between the date a person was arrested and the date when the final decision on their case was made. To do so, we relied on the Google News data since it indexes all major international media sources. We queried Google News for each suspect’s name (in Latin script), and then checked whether they were mentioned by the foreign media or not. We coded the results as a binary variable (1 is a suspect was mentioned by more than 1 international source; 0 if they were not mentioned at all or were mentioned just by 1 source). In addition, we counted only the mentions by topically diverse sources oriented at diverse international audiences (i.e. The New York Times, The Guardian, Der Spiegel), not the English-language sources focused specifically on Russia and/or other Eastern European and post-Soviet states (the mentions by The Moscow Times, English-language edition of the Russian Meduza online media, and Radio Free Europe were not counted). This was done as we are interested in the levels of international publicity that can reach broad foreign audiences, not in the publicity oriented at the audiences interested specifically in Russia and Russian news.

Methods

We tested whether we observe statistically significant relationships between (a) the levels of domestic publicity and (b) the presence of international publicity about a certain suspect and the outcome of their case.

To investigate the nature of domestic publicity in detail, we analyzed not just the aggregate numbers but the timeline of mentions of each suspect between the time of their arrest and the final decision on their case. We split the periods between arrest and decision into subsections (later referred to as bins). Since the duration of the periods between arrest and decision differed vastly between the cases and suspects, we looked not at the absolute numbers of days but rather at relative periods (i.e. first half of the period between arrest and decision and last half, rather than first 10 days and last 10 days). We tested bins of 2–10 equal subsections, meaning that when split into 10 subsections each bin represents 10% of the time between the arrest and the decision with the minimum duration of a bin being 2 days. For each subsection we calculated the values corresponding to three variables, and ran point-biserial correlations for each subsection-variable vs outcome combination:

Average: The average number of mentions of the suspect in this bin

Max: The highest number of mentions of the suspect in a day in this bin

Zeroes: The number of days without any mention of the suspect in this binDue to the nature of the data on international publicity, the analysis here was less fine-grained. To test for the presence of the relationship between the outcome of a suspect’s case and the presence of absence of international publicity about them (binary variable), we used Fisher’s exact test to test whether there is a statistically significant relationship between two binary or categorical variables when the number of observations in the sample is low. (Kim Citation2017)

Results

Domestic publicity potentially matters if one times it right

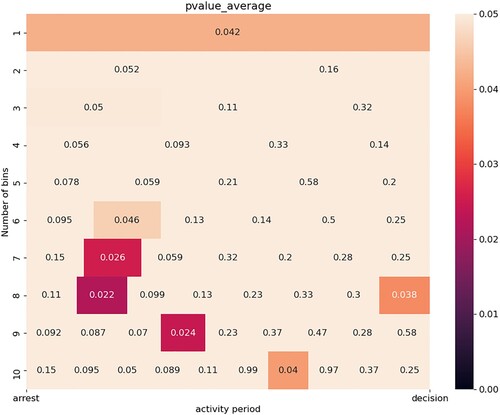

Overall, we find a statistically significant relationship between the average number of mentions of a specific suspect per day over the entire activity period (Number of bins = 1) and the outcome in their case. The correlation coefficient equals −0.32 (p-value = 0.042, CI95% −0.57 to −0.012) thus indicating that increased domestic publicity is associated with a decreased likelihood of a suspect to receive a real sentence. In , the number of bins is shown on the y-axis and the p-values for all the bins are reported in the rows of the heatmap. The x-axis is normalized to represent the period between arrest and decision. The colour-coding shows all p-values higher than 0.05 in the lightest colour and lower p-values in darker colours. We find that a higher amount of domestic publicity in the cases in question is associated with a decreased likelihood of a suspect receiving a real sentence. While this relationship holds overall, there is no pattern that would suggest that the average mentions have a significant relationship to outcome in any specific part of the activity period.

Figure 1. p-values for correlations between average values in different bins and the outcomes of individual cases.

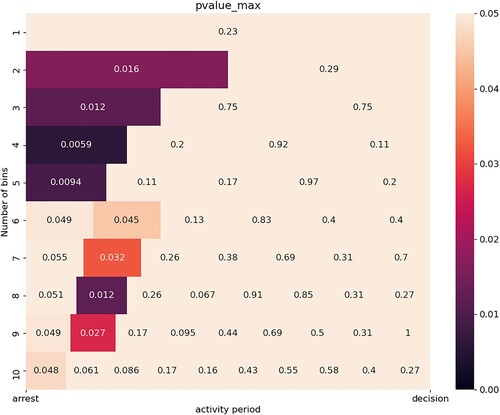

Figure 2. p-values for correlations between max values in different bins and the outcomes of individual cases.

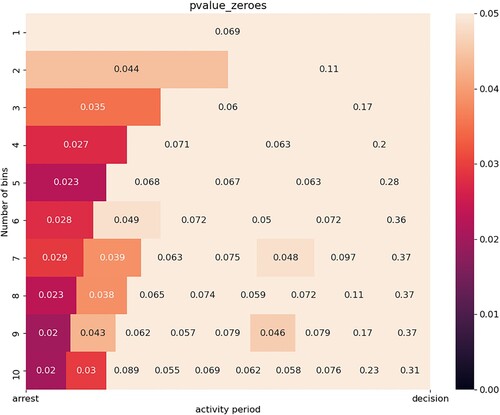

Figure 3. p-values for correlations between zero values in different bins and the outcomes of individual cases.

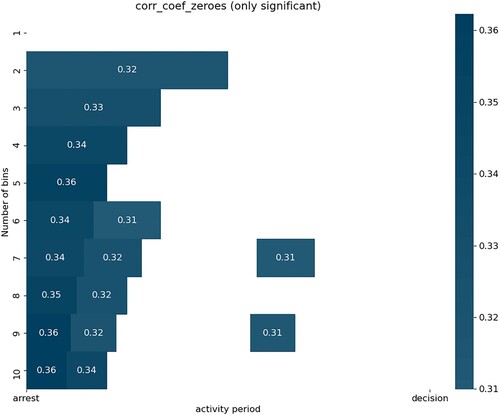

While the average is a proxy for the overall level of discussion of a subject’s case among domestic audiences, the max is a proxy for the intensity of these discussions. The higher a peak in the various bins, the more intense the discussion has been. Zeroes on the other hand is a proxy for whether or not the discussion is sustained over a period of time. If there are zero mentions of a suspect’s case, it can be assumed that the discussion about them is not ongoing. When analyzing the relationships for max and zeroes, we can observe a clear pattern for the relationship between these variables and the outcome (see ).

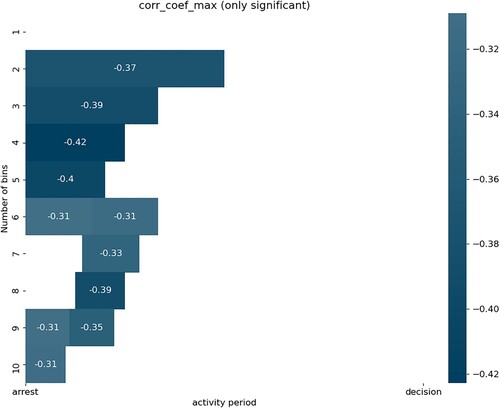

The analysis shows that the relationships between high levels of domestic publicity (max) or its complete absence (zeroes) and the outcomes of individual cases is significant in the early stages after one’s arrest. The relationship between number of mentions and the outcome is sizeable (see and ). The significant correlation coefficients vary between 0.3 and 0.4 (or −0.4 and −0.3, depending on the directionality of the relationship). In the case of the max value, the coefficients are negative because the higher the max value, the less likely is an outcome of 1 (fulfilled repression) and positive in zeroes as the more days with no mention the more likely is an outcome of 1 (fulfilled repression). In addition, as levels of publicity tend to be correlated in adjacent time periods (i.e. between the first and second bins), we suggest it is the early-on publicity (bin 1) that drives the observed relationship.

Figure 4. Coefficients for all significant relationships between max values in different bins and the outcomes of individual cases.

Figure 5. Coefficients for all significant relationships between zero values in different bins and the outcomes of individual cases.

The findings are especially important since as our data suggests, many cases saw a surge of mentions around the date of the final court decision. However, this has no association with the case outcome with the relationship being insignificant in later bins. Furthermore, of the three variables we tested, only max and zeroes show this profile, suggesting that early sustained and intense publicity has an influence on the decision.

The max value coefficients are strongest in the first stages of the activity period. Hence, widespread publicity early on is seemingly associated with a decreased likelihood of a suspect receiving a real jail term. Furthermore, the association between the presence of days without mentions (zeroes) early on and the outcome shows the importance of sustained publicity.

That being said, given the nested nature of our data, it is, as we mention in the methodology, possible that our observations are distorted due to the nested nature of the data. To test this, we ran a fixed effects logit regression as described in the Methodology. Out of the three independent variables, only the zeroes variable was significantly (p < 0.1) associated with case outcomes (Estimate = 0.01). The full resulting table is reported in the Supplementary Material. The results of the regression analysis thus indicate that our observations regarding the importance of early-on publicity might stem from the fact that the Moscow Case received more publicity than the two other cases in our sample and, at the same time, the share of individuals who did not receive real sentences was higher in this case than in the two others – however, it is unclear if the latter can be attributed to the publicity or to other differences with the two other cases. Nonetheless, even in the fixed effects regression the absence of mentions of individuals is still associated with individual outcomes even accounting for the unobserved differences between the three cases, again showing the importance of sustained and constant domestic publicity. We discuss the implications and possible interpretations of the discrepancies in the significance of different variables in the two types of the analyses in the Discussion section.

International publicity matters

We find a statistically significant relationship between the presence of wide international publicity about a suspect and the outcome of their case. The p-value of Fisher’s exact test is equal to 0.006, international publicity is also a significant predictor of the outcome of the case in the fixed effects logit regression (p < 0.05, Estimate = −1.31, see the Supplementary Material for the full table). The observed relationship indicates that the presence of international publicity is associated with decreased likelihood that the respective suspect is sentenced to a real jail term. Only around 17% of the suspects about whom international publicity was present were sentenced to real jail terms. Among the suspects without international publicity, around 65% received real jail terms, with the share of those receiving real terms in the overall sample being approximately 51%.

Is domestic publicity alone enough?

Given that there is a significant relationship between the international publicity and case outcomes, as well as a significant relationship between the number of days without the mentions of an individual in domestic sources and the outcome of the case, we found it would be worthwhile to also analyze the relationship between domestic publicity and international publicity to check if those are related and one might be mediating the other. We find a strong relationship between the two. As demonstrated in , the relationship is statistically significant and substantial for average mentions (average), the highest number of mentions at any point between arrest and decision (max) and days with no mention (zeroes) over the entire activity period and international publicity.

Table 1. Correlations between international publicity and different variables related to domestic publicity.

This led us to further question our findings. Since the number of days without mentions (zeroes) and international publicity are significantly correlated with the outcomes as well as with each other, we found it important to investigate the potential relationship between the two and the outcomes. For that, we ran a logit regressions with fixed effects where the dependent variable was the case outcome, and the independent variables were international publicity, zeroes metric and the interaction between the two. The two independent variables remained significant at p < 0.1, however, the interaction term was not significant (see the Supplementary Material for the full table), suggesting that the observed effects are not conditional on one another.

Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study is that we do not take the legal and procedural differences between the three cases in question into account. We acknowledge that these might have had major influence on case outcomes. However, since we decided to focus on the connection between political repression and publicity, we deliberately left out all the factors except for a case to be politically salient and concern multiple suspects with different case outcomes. The rationale behind this decision is further described in the Background section, and the implications are laid out in the Discussion.

For our analysis, we rely on two different sets of data: Telegram data to measure the level of domestic publicity about individual suspects, and Google News data to measure the presence or absence of international publicity about the suspects. The two datasets, as well as corresponding variables, are different in nature, thus making the analysis performed on this data not fully comparable. At the same time, we suggest that obtaining fully comparable media data in this particular case would not have been possible due to the differences between the Russian and Western media systems. Our data on international publicity is largely based on the legacy media that are indexed by Google News. Obtaining the same kind of data for Russia (i.e. legacy media only, indexed by Google News and/or Yandex News) would not yield usable results since the Russian media system is not free, and legacy media are prone to pro-government bias and/or censorship when it comes to political topics. At the same time, Russia has an abundance of alternative media ranging from online-only outlets established in recent years to bloggers and platform-specific small media that exist in the form of Telegram channels-only. When it comes to political topics, Telegram is an especially vibrant platform in this respect. Western media are barely present on Telegram, and Western media systems and news consumers are less reliant on alternative media than their Russian counterparts, hence international data obtained from alternative media would not have been comparable to the Russian one, and as major international media and organizations are not active on Telegram, we could not have collected the corresponding data from there.

Of course, one option could have been gathering Twitter data by querying Twitter for the names of the suspects in Cyrillic and in Latin. We did not pursue this idea for several reasons. First, Twitter is less popular in Russia than Telegram. Second, even with Cyrillic–Latin distinction, it would have been difficult to separate domestic data from international (i.e. tweets in Latin could have been posted by domestic actors trying to attract international attention, while tweets in Cyrillic could be coming from the actors based in the countries that also use Cyrillic – i.e. some former post-Soviet states). Third, Twitter is rather frequently subjected to attacks from bots, including both pro-Russian-government and anti-Russian-government ones (Stukal et al. Citation2019), which affects the quality of Twitter data. Finally, we were interested in publicity provided by media (both, legacy and alternative) and comparatively popular bloggers, which we were able to measure using Telegram and Google News data, but Twitter data would not have been useful in this respect since Twitter is dominated by posts from individual users.

For the reasons listed above, we believe that, though the two datasets we used in this paper are different in nature and not fully comparable, they are still useful for our analysis and allow us to reliably answer our research questions.

Discussion

We found statistically significant relationships with the correlation coefficients being equal to around ∼0.3 (or −0.3, depending on the directionality) between domestic publicity and outcomes of individual cases, with the relationship being the strongest in the early stage of case development, and being only present if there is international publicity. We suggest that the observed relationship might have two explanations in terms of the mechanisms behind it.

The level of publicity represents the cost for authoritarian regimes to execute repression. The higher the level of publicity, the more public resistance the regime will have to take into account. We would like to note that here, by the regime, we broadly understand politicians representing an authoritarian government as well as high-ranking officials, including those from secret services (i.e. FSB in Russia) and, possibly, prosecuttion and the police. Since in all cases in question the suspects were regular citizens rather than high-profile activists or opposition politicians, we cannot state with confidence whether these specific cases were initiated from the sanction of and then controlled by high-ranking political actors such as the presidential administration. Still, as they gained political salience, we would expect them to be noted and controlled for at least by high-ranking local officials and/or officers, who could interfere with the process and call off a case if they would expect repressive actions to lead to a wide public discontent or otherwise see the cost of repression as being too high. We suggest that it is the easiest to call off a case and, for instance, release suspects pre-trial or control the outcomes of the trials more closely if such cost–benefit analysis is conducted in the early stages after a case was opened, which could potentially explain why early publicity correlates with a decreased likelihood of a suspect receiving a real jail term. However, if the case has progressed already fairly far through the judicial system, the investment of the regime is higher and thus the likelihood of a reversal of the repression decision is less likely as the progress of the case represents a sunk cost. This mechanism might explain the fact that we see the association only between early and sustained publicity and the case outcomes, but not between publicity at later stages and outcomes. An alternative explanation for the observed relationship, departing from the rational choice interpretations, and relating to the described limitation of cases being legally different is that sustained early-on publicity increases the suspects’ chances to receiving quality legal protection early in their case. For instance, suspects who could not afford a lawyer, could, in case they received a lot of publicity, be protected by highly qualified legal professionals funded by public donations and/or working at dedicated NGOs such as Agora or OVD-Info. Thus, increased access to resources such as legal protection is another potential mechanism explaining the observed relationship between publicity and decreased likelihood of receiving a real sentence. Furthermore, it is possible that domestic publicity generates the kind of attention necessary to draw international publicity to the case. This is particularly likely as domestic publicity has a significant relationship early in the activity period.

Overall, international publicity is more strongly related to the outcomes of individual cases than the domestic one. Based on the results, we suggest that attracting wide international attention to specific individuals who are persecuted for political reasons before their cases go to trial might decrease the chances of these individuals receiving real jail terms. With the association between publicity and repression being context-specific as found by previous studies, we find it would be useful to further test the observed relationship in other politically salient cases in Russia and beyond.

Regardless of the type (domestic or international) of publicity and the mechanism behind its relation to the outcomes (i.e. through the cost–benefit analysis performed by the state, the suspects’ increased access to legal protection or both), we find that publicity is related to the outcomes of politically salient individual cases in Russia, highlighting the importance of public attention generated by the media and civil society in contemporary Russia. That being said, we would like to note that our observations pertain to the period that was several years ahead of the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The invasion has changed the political landscape inside Russia and was accompanied by a massive crackdown on the remaining independent media and anti-war and anti-regime activists. In light of this, it is likely that the importance of public attention to specific cases has been decreased and our findings are no longer relevant in Russia post-invasion. Nonetheless, it is possible that similar relationships can be observed in other authoritarian regimes such as Turkey which, we suggest, is worth a further study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The raw data underlying the analysis (e.g. original raw Telegram messages) for privacy and ethical reasons – some of these might have been deleted by creators; further, given the increased rate of repression against political expression on social media in Russia, we believe publicly sharing the messages within the context of this paper could potentially attract attention to the users who posted them and put them in danger. Thus, the raw data can only be obtained from the corresponding author (A.U.) for academic purposes only upon request. However, in line with the Basic Data Sharing policy, we are making publicly available the aggregated data on the number of mentions of each case suspect on Telegram across different periods, and the data on the case outcomes and presence of international publicity (thus the aggregated data necessary to reproduce our findings). This data is available from Figshare https://figshare.com/s/c58c10e8445d8f050ae5 (note that we are sharing a ‘private link' that ensures the anonymity of the authors for blind peer-review; we will replace this private link with a publicly accessible and searchable DOI upon publication of the manuscript).

Notes

1 The only exemption from this filtering rule is the case of Pavel Ustinov as in this particular case the court has changed its decision after the initial trial and switched the punishment for Ustinov from the real to the suspended sentence after weeks later following an appeal and a massive public campaign in Ustinov’s support. This is the only case where a real sentence was replaced with a suspended one following an appeal (unlike in the other cases, i.e. that of Nikita Chirtsov), hence it is treated differently. For Ustinov we treat September 30, the date when the decision on his appeal mas made, as the final decision date.

References

- Akbari, A., and R. Gabdulhakov. 2019. “Platform Surveillance and Resistance in Iran and Russia: The Case of Telegram.” Surveillance & Society 17 (1/2): 223–231. doi:10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12928.

- Amnesty International. 2019. “Urgent Action: Stop the Prosecution of Peaceful Protesters (Russian Federation: UA 112.19).” Amnesty International USA. 2019. https://www.amnestyusa.org/urgent-actions/urgent-action-stop-the-prosecution-of-peaceful-protesters-russian-federation-ua-112-19/.

- Bak, D., S. Sriyai, and S. A. Meserve. 2018. “The Internet and State Repression: A Cross-National Analysis of the Limits of Digital Constraint.” Journal of Human Rights 17 (5): 642–659. doi:10.1080/14754835.2018.1456914.

- Baltar, F., and I. Brunet. 2012. “Social Research 2.0: Virtual Snowball Sampling Method Using Facebook.” Internet Research 22 (1): 57–74. doi:10.1108/10662241211199960.

- Biernacki, P., and D. Waldorf. 1981. “Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling.” Sociological Methods & Research 10 (2): 141–163. doi:10.1177/004912418101000205.

- Carroll, O. 2019. “Russian Justice System Criticised after Acquittal Rate Drops to 0.25%.” The Independent. May 29, 2019. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/russia-justice-system-low-acquittal-rate-uk-crown-court-a8935016.html.

- Christensen, D., and F. Garfias. 2018. “Can You Hear Me Now? How Communication Technology Affects Protest and Repression.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 13 (1): 89–117. doi:10.1561/100.00016129.

- Davenport, C. 2007. “State Repression and Political Order.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.101405.143216.

- Duvall, R. D., and M. Stohl. 1983. “Governance by Terror.” In The Politics of Terrorism, 2nd ed. edited by M. Stohl, 179–219. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Publishing.

- Earl, J. 2011. “Political Repression: Iron Fists, Velvet Gloves, and Diffuse Control.” Annual Review of Sociology 37 (1): 261–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102609.

- Exo, L. 2020. Telethon: Full-Featured Telegram Client Library for Python 3 (version 1.11.2). Python. https://github.com/LonamiWebs/Telethon.

- Franklin, J. C. 2008. “Shame on You: The Impact of Human Rights Criticism on Political Repression in Latin America.” International Studies Quarterly 52 (1): 187–211. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00496.x.

- Gel’man, V. 2016. “The Politics of Fear: How Russia’s Rulers Counter Their Rivals.” Russian Politics 1 (1): 27–45. doi:10.1163/24518921-00101002.

- Goodman, L. A. 1961. “Snowball Sampling.” Annals of Mathematical Statistics 32 (1): 148–170. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177705148.

- Guriev, S., and D. Treisman. 2018. “Informational Autocracy: Theory and Empirics of Modern Authoritarianism.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2571905. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2571905.

- Hafner-Burton, E. M. 2008. “Sticks and Stones: Naming and Shaming the Human Rights Enforcement Problem.” International Organization 62 (4): 689–716. doi:10.1017/S0020818308080247.

- Hendley, K. 2015. “Resisting Multiple Narratives of Law in Transition Countries: Russia and Beyond.” Law & Social Inquiry 40 (2): 531–552. doi:10.1111/lsi.12132.

- Hendrix, C. S., and W. H. Wong. 2013. “When Is the Pen Truly Mighty? Regime Type and the Efficacy of Naming and Shaming in Curbing Human Rights Abuses.” British Journal of Political Science 43 (3): 651–672. doi:10.1017/S0007123412000488.

- Huang, H. 2015. “Propaganda as Signaling.” Comparative Politics 47 (4): 419–444. doi:10.5129/001041515816103220.

- Human Rights Watch. 2019. “The ‘Moscow Case’: What You Need to Know.” Human Rights Watch. October 30, 2019. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/10/30/moscow-case-what-you-need-know.

- Kim, H.-Y. 2017. “Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Chi-Squared Test and Fisher’s Exact Test.” Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 42 (2): 152–155. doi:10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152.

- Krain, M. 2012. “J’accuse! Does Naming and Shaming Perpetrators Reduce the Severity of Genocides or Politicides?: Naming and Shaming Perpetrators.” International Studies Quarterly 56 (3): 574–589. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2012.00732.x.

- Lawrence, A. 2013. “Repression and Activism among the Arab Spring’s First Movers: Morocco’s (Almost) Revolutionaries.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2299323. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2299323.

- Lebovic, J. H., and E. Voeten. 2009. “The Cost of Shame: International Organizations and Foreign Aid in the Punishing of Human Rights Violators.” Journal of Peace Research 46 (1): 79–97. doi:10.1177/0022343308098405.

- Ledeneva, A. V. 2013. Can Russia Modernise?: Sistema, Power Networks and Informal Governance. Null Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leshchenko, S. 2014. “The Maidan and Beyond: The Media’s Role.” Journal of Democracy 25 (3): 52–57. doi:10.1353/jod.2014.0048.

- Memorial. 2019. “Memorial Publishes New Lists of Political Prisoners in Russia | Human Rights Center MEMORIAL.” 2019. https://memohrc.org/en/news_old/memorial-publishes-new-lists-political-prisoners-russia.

- Moore, W. H. 2000. “The Repression of Dissent: A Substitution Model of Government Coercion.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44 (1): 107–127. doi:10.1177/0022002700044001006.

- Nye, J. S. 2013. “What China and Russia Don’t Get About Soft Power.” Foreign Policy (blog). April 29, 2013. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/04/29/what-china-and-russia-dont-get-about-soft-power/.

- Odabaş, M., and H. Reynolds-Stenson. 2018. “Tweeting from Gezi Park: Social Media and Repression Backfire.” Social Currents 5 (4): 386–406. doi:10.1177/2329496517734569.

- Oliynyk, K. 2019. “Blood, Broken Legs, And Mass Detentions: 2019s Moscow Protests.” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. December 23, 2019. https://www.rferl.org/a/moscow-protests-2019-photos-detentions-blood-broken-legs/30330552.html.

- Peterson, T. M., A. Murdie, and V. Asal. 2018. “Human Rights, NGO Shaming and the Exports of Abusive States.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (3): 767–786. doi:10.1017/S0007123416000065.

- Pierskalla, J. H. 2010. “Protest, Deterrence, and Escalation: The Strategic Calculus of Government Repression.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 54 (1): 117–145. doi:10.1177/0022002709352462.

- Prilutskaya, N. n.d. “Russian Federation: The Network Case, Shrouded in Secrecy and Marred by Numerous Torture Allegations,” 5.

- Reporters Without Borders. 2020. “2020 World Press Freedom Index | Reporters Without Borders.” RSF. 2020. https://rsf.org/en/ranking.

- Ruijgrok, K. 2017. “From the Web to the Streets: Internet and Protests Under Authoritarian Regimes.” Democratization 24 (3): 498–520. doi:10.1080/13510347.2016.1223630.

- “Russia: Prosecution for Membership of a Non-Existent ‘Terrorist’ Organization Must Stop.” n.d. Accessed November 2, 2020. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/02/russia-prosecution-for-membership-of-a-non-existent-terrorist-organization-must-stop/.

- Sakwa, R. 2010. “The Dual State in Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs 26 (3): 185–206. doi:10.2747/1060-586X.26.3.185.

- Salikov, A. 2019. “Telegram as a Means of Political Communication and Its Use by Russia’s Ruling Elite.” Politologija 3 (95): 83–110. doi:10.15388/Polit.2019.95.6.

- Stukal, D., S. Sanovich, J. A. Tucker, and R. Bonneau. 2019. “For Whom the Bot Tolls: A Neural Networks Approach to Measuring Political Orientation of Twitter Bots in Russia.” SAGE Open 9 (2): 2158244019827715. doi:10.1177/2158244019827715.

- “The Members of New Greatness Are Political Prisoners, Memorial Says|Human Rights Center MEMORIAL.” n.d. Accessed November 2, 2020. https://memohrc.org/en/news_old/members-new-greatness-are-political-prisoners-memorial-says.

- Tilly, C. 1978. From Mobilization to Revolution. 1st. ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publ.

- Urman, A., and S. Katz. 2020. “What They Do in the Shadows: Examining the Far-Right Networks on Telegram.” Information, Communication & Society 0: 1–20. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1803946.

- Van der Vet, F. 2018. “‘When They Come for You’: Legal Mobilization in New Authoritarian Russia.” Law & Society Review 52 (2): 301–336. doi:10.1111/lasr.12339.

- Walter, E. V. 1972. Terror and Resistance: A Study of Political Violence with Case Studies of Some Primitive African Communities. Terror and Society 1. London: Oxford University Press.