ABSTRACT

Several studies have examined the success of populist leaders in recent decades. These studies focus on both supply side factors that concern the traits of populist actors and demand side factors in the form of characteristics of the supporters. However, we still lack a solid understanding of how these supply and demand side factors interact to explain the support of populist leaders. We contribute to this literature by examining the interplay of two central supply side factors, people-centeredness and anti-immigration policies, and two demand side factors, political dissatisfaction and generational differences, in determining populist support. We test these explanations by leveraging a choice-based conjoint analysis embedded in a representative sample of the Finnish population (n = 1030). The results show that while people-centeredness enhance the favourability of prospective political leaders among the general population, only anti-immigration policies appeal to the politically dissatisfied. In contrast to recent studies, we find no evidence that populist leader traits would be more favoured by younger generations. These results indicate that the interplay between supply and demand may well be more intricate than what previous studies suggest.

Introduction

The electoral success of populist politicians during the recent decades has ushered in a rapidly growing body of research on political populism. Studies of populism have examined how various factors affect the appeal of populist leaders, but the underlying reasons are still not well understood. In particular, there is currently no adequate understanding of how the interplay between the supply side factors, that is, the traits of populist actors, and the demand side factors, such as the characteristics of the voters, shape the electoral appeal of populist politicians.

Several recent studies have made important contributions in studying the support for populist parties (Kessel Citation2013; Kestilä-Kekkonen and Söderlund Citation2014; Oesch Citation2008). While these studies provide important insights, there are still few studies that have examined the complex interactions between supply and demand factors to account for the appeal of populism. For example, right-wing populism typically go hand-in-hand with promoting anti-immigration policies (Iakhnis et al. Citation2018; Mudde Citation2007). When a potential leader at the same time espouses anti-elitism and anti-immigration policies, it is difficult to ascertain what aspect is more important. Moreover, most of the literature on populism focuses either on supply or demand side factors when explaining support for populist parties (Kessel Citation2013; Mudde Citation2007). While supply side explanations emphasize the actions of populist actors in mobilizing support, demand side explanations focus on the characteristics of the supporters. What is frequently missing is an account of the interplay between demand and supply in shaping support for populist leaders and/or parties. In other words, certain actions of populist actors may appeal to particular segments of the population, while other actions appeal to other segments. This would entail that it is futile to try to establish the relative importance of supply and demand factors without considering their interplay.

Additionally, survey studies may underestimate actual support for populist politicians, as people may find it difficult to admit supporting provocative candidates using divisive rhetoric. Our paper forms part of an emerging literature that has begun to examine the interplay of the supply and demand side factors in examining the success of populist politicians using experimental methods (Neuner and Wratil Citation2020).Footnote1 We here focus on two central supply side factors: the extent of people-centeredness and anti-immigration policies. While these are by no means the only relevant features, most scholars agree that they are central features of right-wing populism. We are here particularly interested in examining how specific these supply factors of populism interact with demand factors in the form pf respondents’ characteristics. Again we are forced to restrict our selection and focus on the interplay with levels of political dissatisfaction and age, since recent studies suggest that the dissatisfied and younger citizens are more accepting of populist leaders (Foa et al. Citation2020; Foa and Mounk Citation2020; Mounk Citation2018; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019).

Our study was pre-registered for hypotheses, data collection, and analyses at Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/f6gr4/?view_only=e0b732f5f1934f3cb9e07084966b258d. We leverage evidence from a choice-based conjoint analysis to examine the specific effects of people-centeredness and anti-immigration policies and examine whether their effects vary across level of dissatisfaction and age cohort.

The results show that people-centeredness increases the favorability of political leaders, but only supporting anti-immigration policies appeal particularly to the politically dissatisfied. We find no differences across age groups, meaning there is not any evidence that younger people favour populist leaders more than older citizens.

The appeal of populist leaders: demand and supply side factors

Populism is a contested concept, and it has been difficult to find agreement on a definition among scholars. While disagreements persist, most scholars now adopt an ideational approach to the topic, which entails that populism is considered a thin ideology that pits the will of the people against the preferences of a corrupt political elite (Mudde Citation2017). We follow this approach and define populism as an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the general will of the people (Mudde Citation2004, 543). This implies that populism is a thin-centered ideology that coalesces with other ideologies and ideas. This conceptualization of populism has led to a fruitful research agenda. For the present purposes, it is particularly relevant to note the recent studies that consider populism to be a multidimensional construct, composed of two or more concept components such as anti-elitism, belief in popular sovereignty and a Manichean outlook on society (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2021; Wuttke, Schimpf, and Schoen Citation2020). This not only means that it is possible to go beyond viewing populism as a dichotomy to determine the extent to which people’s attitudes or parties resemble the populist ideal (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2021). This multidimensionality also opens up the possibility that different aspects of populism may appeal to different groups of potential supporters (Osuna Citation2020). This brings us to our central aim here, which is to examine the interplay between explanatory factors in shaping support for political actors, be they parties or their leaders, who are an important part of the success (Michel, Garzia, and da Silva F Citation2020).

Previous studies examining the success of populist parties usually focus on examining supply and demand side factors. The supply factors focus on characteristics of the presumptive populist leaders and their actions (Kessel Citation2013; Kestilä-Kekkonen and Söderlund Citation2014; Mudde Citation2007). This entails that the supply factors essentially concern different populist strategies for mobilizing support among the population. This could, for example, concern communication that emphasizes the need to empower ordinary people over corrupt political elites, which is a typical strategy for populist parties (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019).

The demand factors concern the characteristics of the supporters of populist parties and leaders. Here populist supporters are often characterized by being dissatisfied with the current political system (Kitschelt Citation2002; Voogd and Dassonneville Citation2020), but other characteristics such as economic hardship, cultural and social factors have also been argued to play important roles in determining who votes for populist parties (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Citation2020; Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016). This shows that quite diverse groups have been argued to support populist parties, and there is still no agreement on what segments are more receptive to the populist message.

Our argument entails that certain supply side strategies appeal more strongly to certain supporters, whereas other strategies appeal to other groups. While this assertion may not be particularly novel, the implications have not always been fully appreciated in studies of populism since it becomes paramount to consider the interplay between supply and demand to understand why populist leaders gain success. While exceptions do exist, this insight is rarely headed in empirical studies of populism that often focus on one specific explanation or a set of explanations.

Our aim here is not to settle conclusively what factors are more important in this interplay between supply and demand, but instead to demonstrate that this provides a viable new approach to studying the phenomenon. Consequently, we also do not aspire to examine all conceivable aspects of populism, as this would be unattainable within a single study. Instead, we explore the interplay between central supply close to the definition of populism and demand side factors that feature prominently in the concurrent debate on who are the populist supporters. As concerns supply side factors, we focus on the agency of populist leaders rather than strategies of more conventional parties (Kessel Citation2013, 179–180). This first concerns people-centeredness, which is posited as the essential feature of populism by the many studies that adopt the definition offered by Mudde (Citation2004). The focus on the antagonism between the pure common people and a corrupt elite is an intrinsic part of populism that is often used to explain the surge of populist leaders in different guises (Canovan Citation1999; Mudde Citation2004; Polk, Rovny, and Bakker Citation2017). By attacking the political establishment and emphasizing that traditional political elites have neglected the worries of ordinary people, populist leaders seek to boost support. In line with this proposition, we expect that promising to emphasize the will of the people has a positive effect on support for a presumptive populist leader:

H1a: Pursuing decisions that reflect the will of ordinary citizens has a positive effect on favorability

H1b: Pursuing anti-immigration policies has a positive effect on favorability.

The list of potential characteristics is virtually endless, but we here focus on two demand side factors that have featured prominently in previous research and have important and non-straightforward implications for how populism affect society: political dissatisfaction and generational differences.

The rise of populism is frequently associated with the increase in political dissatisfaction that most democracies have witnessed during the last decades (Geurkink et al. Citation2020; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Kaltwasser and Hauwaert 2019; Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016). When people no longer trust the political system and doubt the responsiveness of political decision-makers, people may become more attuned to populist messages that emphasize so-called ‘corrupt elites and freeloading immigrants' and become more willing to select leaders who reject the traditional political establishment. All of this suggests that the politically dissatisfied are particularly inclined to listen to the populist message (Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016). Therefore, we test the following hypotheses:

H2a: The positive effect of pursuing decisions that reflect the will of ordinary citizens is stronger among people with high political dissatisfaction.

H2b: The positive effect of pursuing anti-immigration policies is stronger among people with high political dissatisfaction.

According to Inglehart and others (Norris Citation1999), younger citizens may be dissatisfied with the current political system, but they remain attached to fundamental democratic principles. Mounk questions this optimistic interpretation of historical trends and maintain that younger generations are today less eager to embrace democracy. He also notes that young people are more likely to identify as radical and vote for anti-system parties in several countries (Mounk Citation2018, 121). Their rejection of the status quo may mean that young people are unable to resist the appeal of populism. Furthermore, younger people often still lack formal education and are unfamiliar with formal politics, which may also make them more likely to support populist outsiders to the political establishment (Schmuck and Matthes Citation2015). In arguing that younger citizens could be more receptive to the populist message, Mounk follows in the footsteps of Ignazi (Citation1992), who much earlier argued that the rise of populist parties is at least partly a reaction to the changes in values in previous decades. The portrayal of younger generations as less optimistic for the future has gained prominence since the financial crises that began in 2008, which reduced employment opportunities for young people and accelerated trends towards precarious employment, although there are considerable variations across countries (Schoon and Bynner Citation2019). This situation has been argued to increase the tendency for young people to vote for populist alternatives to the established parties (Zagórski, Rama, and Cordero Citation2021). We therefore examine whether the populist leader traits appeal more to the younger generations, as suggested by the extant literature. We test the following hypotheses:

H3a: The positive effect of pursuing decisions that reflect the will of ordinary citizens is stronger among younger generations.

H3b: The positive effect of pursuing anti-immigration policies is stronger among younger generations.

A conjoint analysis of the appeal of populism

We examine these hypotheses in a choice-based conjoint analysis that allows us to both identify the specific effects of the supply side factors and their interplay with demand side factors by examining differences in effects across sub-groups in the population.

The conjoint experiment was embedded in a survey (n = 1030) with quotas ensuring that the sample resembled the Finnish population when it comes to age, gender, and place of living, as shown in .

Table 1. Respondent characteristics.

Since the characteristics of the respondents match the general population when it comes to age, gender, and region of living, we do not use weighting when analysing the results.

Finland provides an interesting background for the study. On the one hand, it is an established multiparty democracy with a strong legacy of consensual political decision-making (Karvonen Citation2014). At the same time, the populist party Finns Party has in all parliamentary elections since 2011 gained 17–19% of the votes and even formed part of the government 2015–2017, which shows that there is support for populist thoughts in the population, as was already pointed out in 2006 (Kestilä Citation2006). It has also been shown that about 16–25% of all citizens born after 1980 voted for the Finns party in the elections 2011–2019, which shows that young people are receptive to the populist message in Finland (Westinen, Pitkänen, and Kestilä-Kekkonen Citation2020).

The survey was conducted during 29 May–1 June 2020 via Qualtrics. The respondents first completed questions on basic socio-demographic information, before answering a series of questions about their general political attitudes and preferences. Following this, the respondents completed the conjoint experiment. The target sample was 1000 respondents, but in the end, 1030 respondents filled in the survey. Power analysis has often been more difficult for conjoint analyses since the units of analyses are choices made rather than respondents. However, a recent contribution makes it possible to gauge the power of conjoint designs (Lukac and Stefanelli Citation2020). Through simulations, the shiny app makes it possible to gauge the power of the conjoint experiment when varying key parameters such as sample size, number of comparisons, effect sizes (Average Marginal Component Effects) and attribute levels (Stefanelli and Lukac Citation2020). We used this approach to examine what effect sizes were detectable with our experiment. In our conjoint, the 1030 respondents perform six tasks, and we include a maximum of three attribute levels. This entails that we can estimate relatively small effects sizes of AMCE = 0.03 with an estimated statistical power of 80%, and effects sizes of 0.04 with a statistical power of 95%. We are therefore able to detect even small effects with a high degree of power.

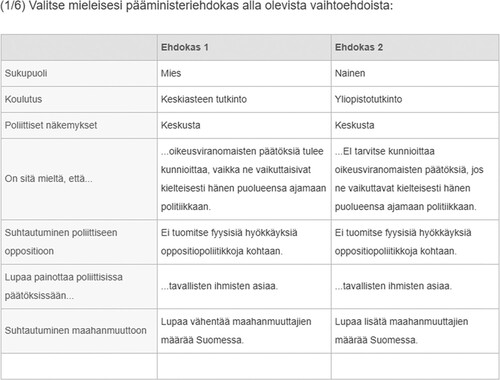

In the choice-based conjoint survey experiment, we presented respondents with comparisons of two profiles presented as prospective prime ministers and asked them to pick the one they would prefer as prime minister of Finland. We deliberately asked people to select a prospective prime minister rather than a candidate in an election since we are interested in what characteristics make a profile a suitable leader rather than a candidate someone would vote for, as this choice may be affected by idiosyncratic factors. A screenshot of the conjoint in Qualtrics and a translation into English is included in the appendix. The profiles were constructed by randomizing the attribute levels of seven attributes included in our conjoint, which consist of theoretically informed discrete values that are likely to affect evaluations of prospective prime ministers. Each of the respondents was asked to make six evaluations.

We use conjoint analysis since it is possible to examine the effects of multiple traits on evaluations (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014, Citation2015; Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020), meaning we can identify the separate effects of people-centeredness and supporting anti-immigration policies. While other techniques are also possible to use, conjoint analysis provides a powerful tool for examining the relative importance of different characteristics of candidates or potential political leaders (Breitenstein Citation2019; Christensen, Rosa, and Grönlund Citation2020; Kirkland and Coppock Citation2018; Saikkonen and Christensen Citation2022). An advantage of conjoint analysis for the current purposes is that it limits problems with social desirability bias (Horiuchi, Markovich, and Yamamoto Citation2021). Since respondents are asked to evaluate several aspects simultaneously without explicitly mentioning specific populist parties or leaders, respondents do not have to feel that they disclose controversial attitudes, which makes it more likely that they will answer truthfully. Finally, a central part of conducting conjoint analysis is to assess differences across subgroups (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020), which makes it an ideal tool to examine the interaction between the supply and demand side factors. shows the attributes included in the conjoint.

Table 2. Conjoint attributes and attribute levels.

We examine the people-centeredness of the leader profiles by including an attribute that gauges the extent to which leaders promise that decisions will reflect the will of ordinary citizens compared to either compromises between political elites or compromises between relevant social groups in society. While following the decisions of citizens may be seen as following traditional models of democratic representation, this construction reflects the definition of Mudde (Citation2004, 543), since the last attribute reflects the populist notion that politics should reflect the will of the people,, whereas the other two attribute levels aligns with elitist and pluralist ideals of decision-making, which constitute the two opposites of populism. Although it may be argued that this measure does not capture anti-elitism, it does capture people-centeredness as a central aspect of populism, and indirectly the idea of the sovereign will of the undivided people that should prevail over political elites in political decision-making (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2021; Wuttke, Schimpf, and Schoen Citation2020).

For anti-immigration policies, we include an attribute describing attitudes on promises on immigration policies. In Finland, as in many other countries, immigration policies constitute the central element on the political agenda for populist parties (Grande, Schwarzbözl, and Fatke Citation2019; Hutter and Kriesi Citation2022; Lutz Citation2019; Rydgren Citation2008). It is, therefore, appropriate to examine this element here to ensure that the attribute is relevant to respondents. This attribute incorporates three levels, as the prospective leader can promise to maintain the status quo, increase the number of immigrants, or reduce the number of immigrants.

We also include two basic democratic norms. Transgressions of norms are frequently attributed to populist leaders, and while they empirically frequently go together, such transgressions are not a defining feature of populism, but the question of whether populism makes such transgressions more acceptable forms part of the empirical analyses. The first norm concerns the rule of law and the basic democratic principle that politicians should respect the insulation of judicial officials from political pressure. This attribute includes two levels; one where the profile clearly states that decisions from judicial officials will be respected even when they have adverse effects, while the other level is the abstention of such promises in the case where the decision could have adverse effects. The other democratic norm concerns violence against opposition politicians, where the first level involves a clear condemnation of violence against opposition candidates, the second level describes the absence of such condemnations while the third involves the profile inciting violence against opposition candidates to grasp the extent of the commitment to democratic norms. While our original aim was to examine the effect of these separately (Saikkonen and Christensen Citation2022), we now explore the interaction between these democratic norms and the two supply side factors to see whether their effects are interdependent. At the same time, we also explore the interaction between the two supply factors to see whether their effects are interdependent.

The other attributes included are important elements of describing a realistic prospective political leader in the conjoint. Left/right ideology is an important characteristic of all political leaders, and this we divide into three attribute levels (Leftist, centrist, rightist). This attribute could potentially affect the impact of other attributes since partisanship has been shown to affect evaluations of profiles (Breitenstein Citation2019; Kirkland and Coppock Citation2018). However, we believe this risk is negligible in a Finnish context where oversized coalition governments across ideological divides continues to be the norm (Karvonen Citation2014, 7).Footnote2 We, therefore, included this attribute to make the profile more convincing to respondents.

We also include two basic background characteristics that are common to include in conjoint experiments of candidate evaluations (Breitenstein Citation2019; Christensen et al. Citation2021; Kirkland and Coppock Citation2018): gender (male vs female) and education (Low, Intermediate, high educational attainment). These attributes do not have substantial interest in this case but help make the comparisons more realistic and provide benchmarks for assessing how important the effects of other characteristics are.

The variables are coded as follows. The conjoint variables are all categorical variables, where all attribute levels are coded as dummy variables indicating whether the attribute in question was shown or not, while the dependent variable is whether a given profile was chosen or not in a comparison.

To gauge political dissatisfaction, we rely on three attitudes: Political trust, Satisfaction with democracy, and External political efficacy. These aspects have all been argued to be imperative signs of political dissatisfaction with the way the political system functions (Geurkink et al. Citation2020; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016). Political trust is measured with an index based on respondents’ trust in parliament, politicians, political parties and government (each item scored 0–10, index 0–40, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94). The respondents were classified into three categories: Dissatisfied (trust scores 0–14, 19.6%), Intermediate (15–25, 38.4%), Satisfied (26–40, 42.0%).Footnote3 Satisfaction with democracy is measured with a single item where respondents indicate their level of satisfaction with the way democracy works in Finland on a scale 0–10. Respondents who indicate 0–4 are classified as having low satisfaction (18.4%), those who pick 5 are classified as intermediate (10.8%), while those scoring 6–10 are classified as having high satisfaction (70.9%). For external efficacy, we form an index based on answers to three questions scored on a five-point Likert scale [(1) Elected representatives quickly forget the worries of ordinary citizens (R), (2) Citizens’ opinions are taken into account in political decision-making, (3) Politicians do not care about the opinions of ordinary people (R), Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75]. The index range 0–12 with higher scores indicating higher external efficacy. Respondents scoring 0–3 were classified as dissatisfied (37.4%), 4–6 as intermediate (44.4%) and those scoring 7–12 were regarded as satisfied (18.3%).

For generations, we divide respondents into four categories corresponding to familiar generational divides: Baby boomers, Generation X, Millennials and Generation Z. While there is no absolute threshold for this division, we broadly rely on thresholds used in other studies (Foa et al. Citation2020), whereby those born 1944–1964 are considered Baby boomers (27.5% of respondents); those born 1965–1979 are considered Generation X (28.5%), those born 1980–1994 are considered Millennials (29.7% Citation2020, and those born after 1995 are grouped as Generation Z (14.3%). In line with the extant literature, we consider Millennials and Generation Z as ‘younger generations' as opposed to the generations born before 1980.

All analyses are linear regression analyses with standard errors clustered at the respondent level (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). The coefficients are interpreted as Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCE), expressing how much the probability of choosing a leader changes on average when an attributes is switched from the reference category to the particular attribute level (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). We include interaction effects between all attributes and the political dissatisfaction and generation variables to examine the interplay between demand and supply (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). The conditional AMCEs show effect sizes across the groups of respondents. When determining the substantial relevance of interaction effects, we do not just rely on formal tests of significance (Brambor, Clark, and Golder Citation2006), but also assess the practical implications by seeing whether the effects have similar magnitudes and directions for different values of the moderator. Finally, we report marginal means (MM) that describe the level of favorability toward leaders who embody a particular attribute level across all other attributes (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020). While the AMCE depends on the reference category used, which can lead to misleading interpretations, the marginal mean describes the popularity of a given attribute level without using a reference category (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020). The results are presented in coefficient plots (Jann Citation2014) while the regression models are found in the appendix.

Results

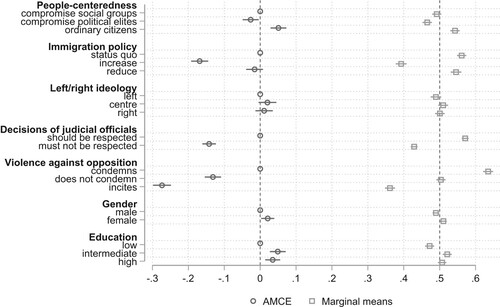

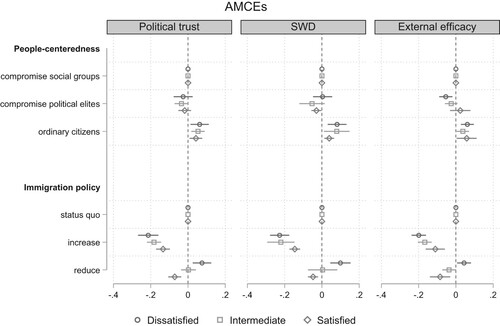

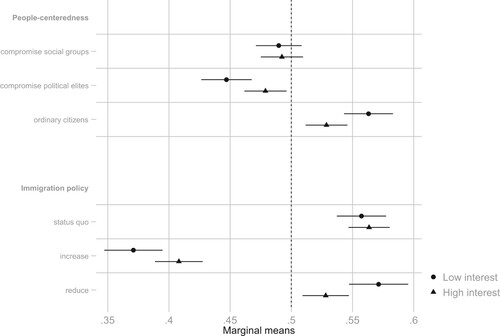

We start with examining the direct effects. In , we report AMCEs and marginal means from the analyses.

The results support H1a since it has a positive effect on favorability when profiles emphasize that decisions will reflect the will of ordinary citizens over compromises among social group in society (AMCE = .05, MM = .54, p < .001). For H1b on the effect of an anti-immigration stance, promising to reduce integration has a negligible and non-significant negative effect on favorability compared to advocating the status quo (AMCE = −0.02, MM = 0.55, p = 0.195), and we therefore reject this hypothesis, although it should be noted that there is a strong negative effect of promising to increase immigration (AMCE = 0.17, MM = 0.39, p < 0.001), showing that there is little support for more immigration in the population.

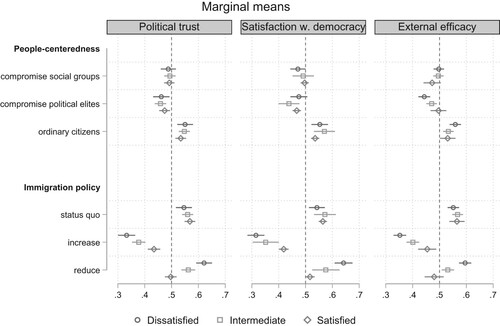

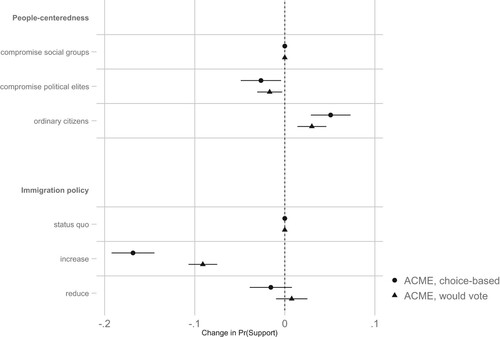

The analyses in concern H2a and H2b and differences across political dissatisfaction. Since AMCEs can be misleading when examining conditional effects, we here follow the recommendations of Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Citation2020), and only report marginal means, but the AMCEs can be found in the appendix. To make the figures easier to read, we only include the attributes of interest for our hypotheses.

The results for H2a on differences in effects of people-centeredness across levels of political dissatisfaction show that there is a single significant interaction term at a conventional p < 0.05 threshold for all three attitudes. This is for external efficacy and concerns the interaction term between compromise political elites and high dissatisfaction (B = 0.08, p = 0.019), and the plot also shows that respondents select profiles emphasizing that decisions should reflect the will of the people slightly more frequently (conditional MM = 56, compared to 0.53 when respondents are satisfied or intermediate). Such differences may be expected due to the intrinsic anti-elitist element in feeling that the system is unresponsive (Geurkink et al. Citation2020, 251–252). Nevertheless, the practical implications are limited, and there are no signs that political dissatisfaction strengthens the people-centric element when it comes to political trust and satisfaction with democracy. Since we do not find that the appeal of people-centrism has a stronger effect among the dissatisfied, H2a is not supported.

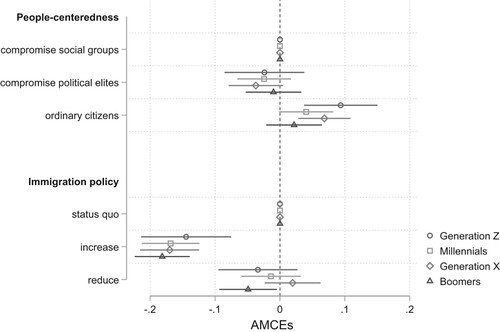

When it comes to H2b and differences in effects of anti-immigration policies across levels of dissatisfaction, there are significant interaction effects for all three attitudes. The differences entail that profiles promising to reduce integration are particularly popular among the dissatisfied regardless of how we measure it, and the conditional MMs are in the range of .60–.64. Hence, the results suggest that the appeal of anti-immigration policies is particularly strong among the politically dissatisfied respondents, which supports H2b. shows the differences across different generations.

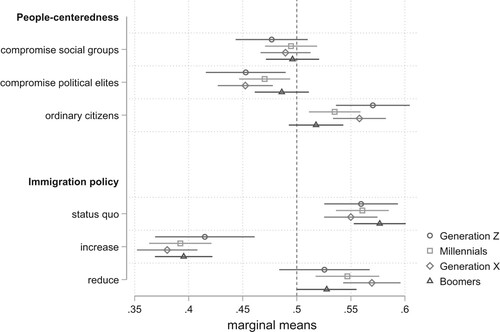

For H3a, there are significant interaction effects for Baby Boomers and emphasizing that decision reflect the will of the people (B = −0.07, p = 0.045). This entails that the marginal mean among this generation is slightly lower (MM = 0.52) compared to other generations, which may show a heritage of the consensual political culture that was dominant in Finland (Karvonen Citation2014). Profiles emphasizing the will of the people are most popular among Generation Z (MM = 0.57), but less so among Millennials who were the target of most of the critique (Foa et al. Citation2020; Foa and Mounk Citation2020; Mounk Citation2018). Since there is no general evidence that younger generations are growing increasingly attentive to people-centrism, we interpret the result for Generation Z to be a life cycle effect rather than a generational effect. Consequently, we therefore reject H3a.

When it comes to anti-immigration and H3b, there are no significant interaction effects, and a visual inspection does not indicate that effects are stronger among the younger generations. We therefore also reject H3b. All of this suggests that the generational differences were quite limited.

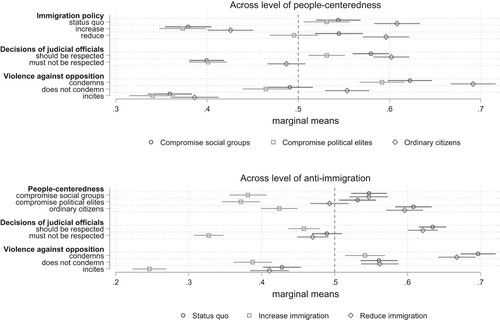

Finally, we also explore whether there are more indirect effects of the supply side factors by examining whether they interact with each other, and whether the supply side factors interact with the two democratic norms included in the conjoint. These analyses were not pre-registered, and we therefore do not propose hypotheses.

We find no significant interaction effects between people-centeredness and pursuing anti-immigration policies, which means that these two supply side factors function completely independently rather than reinforce each other, as might be suspected based on previous research (Iakhnis et al. Citation2018).

Concerning the democratic norms, people-centeredness does seem to affect how ignoring the rule of law affects favourability, since there are significant interaction terms (must not be respected X compromise political elites B = 0.05, p = 0.019; must not be respected # ordinary citizens B = 0.07, p = 0.002). As can be seen in , these interaction effects entail that the respondents are much more forgiving of not respecting the rule of law when the profile promises to enact policies in line with what ordinary citizens want, since they select such a profile about 50% of the time (MM = 0.49), whereas they otherwise punish such transgressions of democratic norms (Compromise social groups MM = 0.40; Compromise political elites MM = 0.40). There are no significant interaction effects between people-centeredness and how profiles consider violence against the opposition, which suggests that the effects of these are similar across the level of people-centeredness. We also find no significant interaction effects for pursuing anti-immigration policies, which entails that respondents are less likely to select profiles that promise to increase immigration under all circumstances.

While these findings are exploratory and by no means conclusive, they indicate that it may be worthwhile to explore how supply side factors interact with other strategies to understand the lure of populism.

Robustness tests

We conducted several robustness checks that are included in the appendix. First we confirm that results are stable across tasks and left/right placement, as is required (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). Since these requirements are fulfilled we may interpret the AMCEs as causal effects. We also examined whether the choice-based design affected the results, since respondents may be forced to select an unappealing profile, when faced with a selection of two unappealing profiles. To see whether results are similar when we allow respondents to avoid selecting an unwanted profile, we asked a follow-up question asking whether they would vote for the selected profile, which gives the possibility to indicate that the selected profile is also not favourable. When we examine the results, we see that the substantial results are very similar, even if the effects as expected are slightly weaker. Finally, we examine the homogeneity of the effects by examining differences across gender, education and political interest. Here there is evidence that while gender differences are negligible, the effects of the supply-side factors are stronger among people with low education and low political interest. We do not explore these findings further as they do not form part of the preregistration. Nevertheless, these results also indicate that it is important to examine differences across sub-groups since certain groups are more receptive to the appeal of populist supply-side factors.

All in all, these robustness tests increase our confidence in the validity of our results.

Conclusion

These results have several important implications for the study of who support populist leaders. First, they underline the importance of disaggregating aspects of the populist phenomena and examining their interplay (Neuner and Wratil Citation2020; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Osuna Citation2020; Wuttke, Schimpf, and Schoen Citation2020). We here focused on two central supply-side factors aspects of populism in contemporary Europe, namely people-centeredness and pursuing anti-immigration policies. Our results show that across the general population in Finland, people-centeredness can boost the popularity of prospective leaders, whereas the impact of an anti-immigration stance appears to be limited.

However, there were important differences across different subgroups in the population, which shows that it is important to examine the interplay of the supply side factors with demand side characteristics to appreciate the appeal of populism.

We find that the two supply factors appeal to different segments of the populist marketplace. Hence, populism is not a uniform entity, but consists of separate ideas and messages that populist leaders can use to appeal to different groups of people. A noticeable difference was that pursuing anti-immigration policies appeals particularly strongly to people with high levels of political dissatisfaction, while we find no similar effect when it comes to people-centeredness, where the effect is even across the level of dissatisfaction. This may seem somewhat counterintuitive considering the affinity between anti-elitism and political dissatisfaction, but it is in line with results from similar studies (Neuner and Wratil Citation2020).

This result indicates that political dissatisfaction may not necessarily reflect a deep-rooted mistrust of the political elites, but dissatisfaction with their unwillingness to enact desired policy goals such as stricter immigration policies. This also suggests that the popularity of leaders using populist appeals among the dissatisfied hinges less on their attacks on the political establishment and more on their attacks on ethnic minorities and immigrants (Rydgren Citation2008). In other words, the lure of populism is not just about discontent with the ruling elite, but also about specific policy goals. To the extent that dissatisfaction plays a role, it is rooted in dissatisfaction with what people perceive as too liberal migration policies rather than a disdain with the notion that elites make political decisions.

But people-centrism may nonetheless play an important role in our understanding the lure of populism, since our exploratory analyses suggested that people may be more forgiving of democratic transgressions when people promise to work for the people rather than the elites. This may explain why populist leaders are frequently associated with behaviour considered to be antithetical to the democratic spirit (Grossman et al. Citation2021; Mounk Citation2018; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Svolik Citation2020). Even if populism per se is not necessarily opposed to democracy in the sense of majoritarian rule, the supporters are willing to overlook populist leaders circumventing the rule of law, which is connected to the liberal protection of basic rights and protection of minorities, that we today often consider an inherent part of democracy (Mounk Citation2018). Since our results here were exploratory in nature, more research is necessary to understand how populist messages makes people willing to forgive even serious violations of basic democratic norms.

In contrast with recent literature (Foa et al. Citation2020; Mounk Citation2018; Foa and Mounk Citation2020), we found no evidence that neither people-centeredness nor pursuing anti-immigration policies have a stronger appeal to younger generations. Hence there is little to suggest that younger citizens are more prone to support populism, as these previous contributions suggested. Overall, our results show very little indication that there are large generational differences in the appeal of popularity messages. This lack of inter-generation differences is interesting considering the amount of literature that has touted the importance of changing values across generations. While we are unable to settle the mechanisms conclusively, our results at least suggest that they work in a similar fashion across age groups.

While we do not claim that these results conclusively settle all issues concerning the lure of populism, we believe that these findings demonstrate the need to examine the interplay between supply and demand to comprehend the appeal of different aspects of populism. Nevertheless, some caveats are in order. Most importantly, the attributes we include do not capture all relevant aspects of the complex concepts they are meant to represent. It may be questioned whether the emphasis on people-centrism and that the general will of the people should prevail adequately capture the anti-elitist and Manichean traits of populism that are often argued to go hand in hand with the emphasis on the people (Mudde Citation2004, Citation2017). Be that as it may, our aim here was to demonstrate that it is advantageous to examine the interplay between supply and demand rather than settle what aspects are more important in the process. There is therefore a need for more research on what aspects of populism are more pertinent and how these are best operationalized.

Furthermore, previous studies show that effects may well differ across contexts (Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016), which means it is pertinent to examine similar issues in a comparative perspective. Finally, some of the non-significant results across subgroups may be due to a lack of statistical power to detect weak effects. Future studies should therefore test these relationships across different contexts and including more respondents. Nevertheless, our results, in line with the work of Neuner and Wratil (Citation2020), show that it is important to consider the interplay between explanatory factors. Furthermore, while other approaches may also provide important insights, conjoint analysis provide a valuable approach for examining the appeal of populism and the complex interplay between the supply and demand side factors. We believe it is imperative to examine this in further detail to comprehend the success of populist leaders.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues at the Department of Political Science, Åbo Akademi University for help with constructing the conjoint experiment. We also thank the editors and the three anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In terms of design, our study resembles Neuner and Wratil (Citation2020), but we focus on different demand and supply side factors and their interaction effects.

2 This assumption is supported by the empirical evidence since we find no significant interaction effects between the ideological attribute and all other attributes, suggesting that this does not affect the results.

3 We tested an alternative approach to classifying respondents into three groups based on the mean +/- 1 standard deviation. The results were substantially similar, but the sizes of the groups differed considerably, as might be suspected.

References

- Brambor, T., W. R. Clark, and M. Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1093/pan/mpi014.

- Breitenstein, S. 2019. “Choosing the Crook: A Conjoint Experiment on Voting for Corrupt Politicians.” Research & Politics 6 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1177/2053168019832230.

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47 (1): 2–16. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00184.

- Christensen, H. S., T. Järvi, M. Mattila, and Å. von Schoultz. 2021. “How Voters Choose one out of Many: A Conjoint Analysis of the Effects of Endorsements on Candidate Choice.” Political Research Exchange 3 (1): Article 1892456. doi:10.1080/2474736X.2021.1892456.

- Christensen, H. S., M. S. L. Rosa, and K. Grönlund. 2020. “How Candidate Characteristics Affect Favorability in European Parliament Elections: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment in Finland.” European Union Politics 21 (3): 519–540. doi:10.1177/1465116520929765.

- Foa, R. S., A. Klassen, M. Slade, A. Rand, and R. Collins. 2020. The Global Satisfaction with Democracy Report 2020. Cambridge: Centre for the Future of Democracy. Accessed 5 January 2022. https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/publications/global-satisfaction-democracy-report-2020/

- Foa, R. S., and Y. Mounk. 2019. “Youth and the Populist Wave.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 45 (9–10): 1013–1024. doi:10.1177/0191453719872314.

- Geurkink, B., A. Zaslove, R. Sluiter, and K. Jacobs. 2020. “Populist Attitudes, Political Trust, and External Political Efficacy: Old Wine in New Bottles?” Political Studies 68 (1): 247–267. doi:10.1177/0032321719842768.

- Grande, E., T. Schwarzbözl, and M. Fatke. 2019. “Politicizing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (10): 1444–1463. doi:10.1080/13501763.2018.1531909.

- Grossman, G., D. Kronick, M. Levendusky, and M. Meredith. 2021. “The Majoritarian Threat to Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1–10. doi:10.1017/XPS.2020.44.

- Hainmueller, J., D. Hangartner, and T. Yamamoto. 2015. “Validating Vignette and Conjoint Survey Experiments Against Real-World Behavior.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (8): 2395–2400. doi:10.1073/pnas.1416587112.

- Hainmueller, J., D. J. Hopkins, and T. Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (01): 1–30. doi:10.1093/pan/mpt024.

- Horiuchi, Y., Z. Markovich, and T. Yamamoto. 2021. “Does Conjoint Analysis Mitigate Social Desirability Bias?” Political Analysis, 1–15. doi:10.1017/pan.2021.30.

- Hutter, S., and H. Kriesi. 2022. “Politicising Immigration in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 341–365. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853902.

- Iakhnis, E., B. Rathbun, J. Reifler, and T.J. Scotto. 2018. “Populist Referendum: Was ‘Brexit’ an Expression of Nativist and Anti-Elitist Sentiment?” Research & Politics 5: 2. doi:10.1177/2053168018773964.

- Ignazi, P. 1992. “The Silent Counter-Revolution.” European Journal of Political Research 22 (1): 3–34. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00303.x.

- Inglehart, R. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization : Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jann, B. 2014. “Plotting Regression Coefficients and Other Estimates.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 14 (4): 708–737. doi:10.1177/1536867X1401400402.

- Kaltwasser, C. R., and S. M. Van Hauwaert. 2020. “The populist citizen: Empirical evidence from Europe and Latin America.” European Political Science Review 12 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S1755773919000262.

- Karvonen, L. 2014. Parties, Governments and Voters in Finland: Politics Under Fundamental Societal Transformation. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Kessel, S. v. 2013. “A Matter of Supply and Demand: The Electoral Performance of Populist Parties in Three European Countries.” Government and Opposition 48 (2): 175–199. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.14.

- Kestilä-Kekkonen, E., and P. Söderlund. 2014. “Party, Leader or Candidate? Dissecting the Right-Wing Populist Vote in Finland.” European Political Science Review 6 (04): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S1755773913000283.

- Kestilä, E. 2006. “Is There Demand for Radical Right Populism in the Finnish Electorate?” Scandinavian Political Studies 29 (3): 169–191. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2006.00148.x.

- Kirkland, P. A., and A. Coppock. 2018. “Candidate Choice Without Party Labels.” Political Behavior 40 (3): 571–591. doi:10.1007/s11109-017-9414-8.

- Kitschelt, H. 2002. “Popular Dissatisfaction with Democracy: Populism and Party Systems.” In Democracies and the Populist Challenge, edited by Y. Mény and Y. Surel, 179–196. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. Accessed 4 April 2022. doi:10.1057/9781403920072_10.

- Leeper, T. J., S. B. Hobolt, and J. Tilley. 2020. “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 28 (2): 207–221. doi:10.1017/pan.2019.30.

- Lukac, M., and A. Stefanelli. 2020. Conjoint Experiments: Power Analysis Tool. Accessed 4 January 2022. https://mblukac.shinyapps.io/conjoints-power-shiny/

- Lutz, P. 2019. “Variation in Policy Success: Radical Right Populism and Migration Policy.” West European Politics 42 (3): 517–544. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1504509.

- Meijers, M. J., and A. Zaslove. 2021. “Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach.” Comparative Political Studies 54 (2): 372–407. doi:10.1177/0010414020938081.

- Michel, E., D. Garzia, F. da Silva F, and A. De Angelis. 2020. “Leader Effects and Voting for the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe.” Swiss Political Science Review 26 (3): 273–295. doi:10.1111/spsr.12404.

- Mounk, Y. 2018. The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom is in Danger and How to Save it. Harvard University Press.

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 542–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

- Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C. 2017. “Populism: An Ideational Approach.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by R. K. Cristóbal, P. Taggart, and P. O. Espejo, 27–47. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Neuner, F. G., and C. Wratil. 2020. “The Populist Marketplace: Unpacking the Role of “Thin” and “Thick” Ideology.” Political Behavior, doi:10.1007/s11109-020-09629-y.

- Norris, P. 1999. Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Authoritarian Populism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Oesch, D. 2008. “Explaining Workers’ Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland.” International Political Science Review 29 (3): 349–373. doi:10.1177/0192512107088390.

- Osuna, J. J. O. 2020. “From Chasing Populists to Deconstructing Populism: A New Multidimensional Approach to Understanding and Comparing Populism.” European Journal of Political Research, doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12428.

- Polk, J., J. Rovny, R. Bakker, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, J. Koedan, et al. 2017. “Explaining the Salience of Anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data.” Research & Politics 4: 1. doi:10.1177/2053168016686915.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, C., and S. M. Van Hauwaert. 2020. “The Populist Citizen: Empirical Evidence from Europe and Latin America.” European Political Science Review 12 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S1755773919000262.

- Rydgren, J. 2008. “Immigration Sceptics, Xenophobes or Racists? Radical Right-Wing Voting in Six West European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 47 (6): 737–765. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00784.x.

- Saikkonen, I. A.-L., and H. S. Christensen. 2022. “Guardians of Democracy or Passive Bystanders? A Conjoint Experiment on Elite Transgressions of Democratic Norms.” Political Research Quarterly. Online First, doi:10.1177/10659129211073592.

- Schmuck, D., and J. Matthes. 2015. “How Anti-Immigrant Right-Wing Populist Advertisements Affect Young Voters: Symbolic Threats, Economic Threats and the Moderating Role of Education.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (10): 1577–1599. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.981513.

- Schoon, I., and J. Bynner. 2019. “Young People and the Great Recession: Variations in the School-to-Work Transition in Europe and the United States.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 10 (2): 153–173. doi:10.1332/175795919X15514456677349.

- Spruyt, B., G. Keppens, and F. Van Droogenbroeck. 2016. “Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It?” Political Research Quarterly 69 (2): 335–346. doi:10.1177/1065912916639138.

- Stefanelli, A., and M. Lukac. 2020. Subjects, Trials, and Levels: Statistical Power in Conjoint Experiments. 18 November. SocArXiv. Accessed 6 April 2022. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/spkcy/

- Svolik, M. W. 2020. “When Polarization Trumps Civic Virtue: Partisan Conflict and the Subversion of Democracy by Incumbents.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 15 (1): 3–31. doi:10.1561/100.00018132.

- Voogd, R., and R. Dassonneville. 2020. “Are the Supporters of Populist Parties Loyal Voters? Dissatisfaction and Stable Voting for Populist Parties.” Government and Opposition 55 (3): 349–370. doi:10.1017/gov.2018.24.

- Westinen, J., V. Pitkänen, and E. Kestilä-Kekkonen. 2020. “Perussuomalaisten äänestäjäkunnan muutos 2011–2019.” In Politiikan Ilmastonmuutos – Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019, edited by S. Borg, E. Kestilä-Kekkonen, and H. Wass, 308–332. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriön julkaisuja.

- Wuttke, A., C. Schimpf, and H. Schoen. 2020. “When the Whole is Greater than the Sum of its Parts: On the Conceptualization and Measurement of Populist Attitudes and Other Multidimensional Constructs.” American Political Science Review 114 (2): 356–374. doi:10.1017/S0003055419000807.

- Zagórski, P., J. Rama, and G. Cordero. 2021. “Young and Temporary: Youth Employment Insecurity and Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Europe.” Government and Opposition 56 (3): 405–426. doi:10.1017/gov.2019.28.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Screenshot from Qualtrics

shows a screenshot of how the conjoint appeared in Qualtrics.

Appendix 2. Translation of the conjoint vignette in Qualtrics

Introduction to the conjoint

People have different views on what kind of prime minister they would ideally like to lead Finland. People may also have different expectations regarding the personality traits, opinions, and behavior of the prime minister.

In the next section, we want to know more about what type of person you think would be best suited as the Prime Minister of Finland. Next, we present various descriptions of potential prime ministerial candidates. The descriptions contain information about the backgrounds and political opinions of different individuals.

You will be shown six pairs of potential prime ministerial candidates. We ask you to choose after each pair the candidate that you think would be best suited for the Prime Minister of Finland.

Read the description of each candidate carefully before making your decision.

Attributes

Choose your preferred Prime Minister-candidate from the options below:

Follow-up question:

Would you vote for this candidate in elections? Yes/No

Appendix 3. Deviations from the preregistration

We here outline all deviations from our pre-registration of hypotheses, data collection, variable coding and analysis. The pre-registration was registered 26 May 2020 and can be found at: https://osf.io/f6gr4/?view_only=e0b732f5f1934f3cb9e07084966b258d

The attribute ‘people-centeredness' is in the pre-registration referred to as populism.

We slightly changed the formulation of the first set of hypotheses to clarify our intentions, but the basic intentions are identical.

H1a was changed from ‘It has a positive effect on favorability when candidates pursue decisions that reflect the will of ordinary citizens compared to pursuing decisions that reflect a compromise' to ‘Pursuing decisions that reflect the will of ordinary citizens has a positive effect on favorability'.

H1b was changed from ‘It has a positive effect on favorability when candidates pursue anti-immigration policies compared to pursuing status quo policies' to ‘Pursuing anti-immigration policies has a positive effect on favorability'.

In the pre-registration, the reference category was stated to always be the first category, but we realized that this made it difficult to comprehend the results in an intuitive manner. We therefore recoded ‘People-centeredness' and ‘Anti-immigration policy' so the reference categories were altered to make understanding the results more intuitive in comparison to how the hypotheses are stated.

For people-centeredness, the reference category was changed from ‘demands of ordinary citizens' to ‘Compromises between relevant social groups'

For Anti-immigration, the reference category was changed from ‘reduce number of immigrants' to ‘maintain status quo'.

Appendix 4. Regression analyses

The following include the regressions models of all analyses that are presented in the main text in figures.

Table A1. Regressions models

Appendix 5. Conditional AMCEs

These results show the conditional average marginal component effects for differences in causal effects across political dissatisfaction () and generations (). They show no substantial differences to the results reported in the main text.

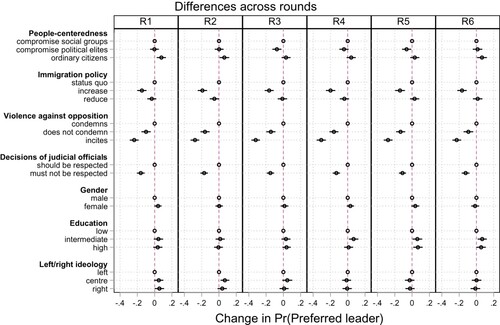

Appendix 6. Left/right ordering and number of tasks

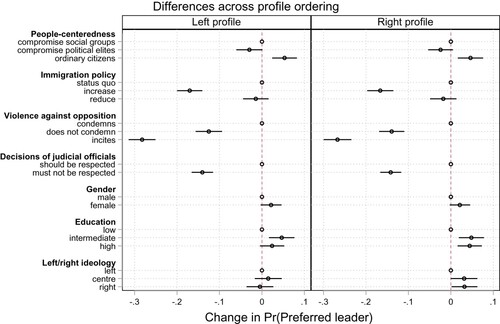

We here test whether the results are similar across rounds and profile ordering, since this is one of the main assumptions underpinning the analysis (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014).

shows differences across the six comparisons that each respondent evaluated. While there is a risk that respondents answer differently across rounds, for example due to survey fatigue or because of carry over effects from previous comparisons. However, here we see that the answers are reasonably stable across the six rounds for all attributes, even if some weak effects grow insignificant in some rounds.

Another assumption concerns profile ordering, which is examined in .

For the results to be valid, the order of the presentation of profiles should have no effect on the outcomes. Here we also conclude that the effects are reasonably similar for the right and left profiles even if some effects appear to be weaker in the profile to the left.

Appendix 7. Willingness to vote as dependent variable

Since the choice-based design may affect results, since respondents may be forced to select a profile they do not support when faced with a selection of two unappealing profiles. We therefore asked a follow-up question asking whether they would vote for the selected profile, which avoids the enforced choice between two arbitrary candidates.

The substantial results are very similar, even if the effects as expected are slightly weaker. A people-centred approach still increases the likelihood that a person would vote for the selected candidate, while promising to increase immigration has a clear negative effect on the likelihood that respondents will also vote for a candidate.

We interpret this to mean that the results generally reflect a genuine preference for the chosen candidate and are not artefacts of the choice-based design.

Appendix 8. Alternative characteristics of the population

We here examine differences across other respondent characteristics to see how these influence the results. These are not included in the main presentation since they did not form part of the preregistration.

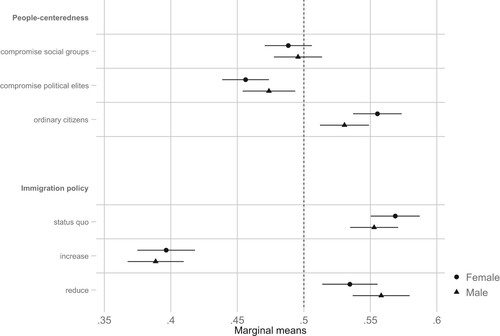

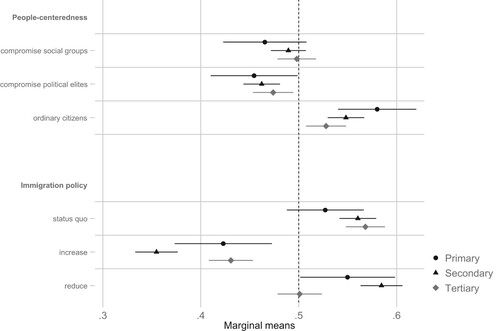

The results for male and female respondents are generally very similar.

For education, we see some evidence that people-centeredness has a stronger appeal among those with low education, although these profiles are preferred by all categories. We also see that profiles promising to increase immigration are less popular regardless of education, but even less so among those with intermediate levels of education. In a similar vein, people with primary or secondary education are more likely to prefer profiles that will reduce immigration while the differences for the highly educated are negligible. This shows that it is mainly those with lower education who feels threatened by immigration.

Finally, we see that those who are less interested in political matters prefer profiles with a people-centered approach and these also more likely to select a profile that promises to reduce immigration.