ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to study why politicians in the same elected assembly perceive political polarization differently, as well as whether and how this influences perceptions of their behaviour. The findings reveals that there is a relationship between local politicians’ perceptions of polarization and winner-loser partisanship and trust. The results show that politicians who have higher levels of trust perceive a lower level of antagonistic behaviour. Being a political winner (in a ruling party coalition) or loser (in opposition) fosters a specific form of partisanship, which affects politicians’ perceptions. Politicians who are winners tend to perceive lower levels of polarization and antagonistic behaviour. More insight into how and why political actors perceive the same situation differently could potentially foster a greater understanding – a political empathy – among political combatants, facilitating interaction. The study is based on data from a survey conducted among all councillors in the 290 municipalities in Sweden.

Introduction

Political polarizationFootnote1 – especially between parties and coalitions of parties – is discussed and addressed worldwide (cf. Abramowitz and Saunders Citation2008). While parties that stand for distinct political alternatives are a prerequisite for a functioning representative democracy, parties that are too far apart and unwilling to compromise may bring democratic processes to an unacceptable standstill. However, it has proven to be surprisingly difficult to determine the scope of polarization, and the degree to which it changes over time. One reason for this, as highlighted by earlier studies, is that there is often a gap between actual polarization (based on objective measures) and perceived polarization (measured as attitudes). As perceived polarization is subjective, it is a given that actor’s perception may vary. How and why such variation occur is of great importance to further our understanding on decision-making processes in democratic systems and will be the main focus of this article.

As perceived polarization among people and political elites fosters a negative view of, or even animosity towards, political opponents (i.e. affective polarization) (Abramowitz and Webster Citation2018; Hetherington Citation2009; Mason Citation2015; Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Citation2012; Westfall et al. Citation2015; Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Citation2006), perceptions of polarization are just as important – if not more so – as actual polarization in shaping peoples’ behaviour (Enders and Armaly Citation2019) and attitudes.

To establish respectful political deliberations in polarized situations, some measure of political empathy is needed among political actors in order to understand how opponents perceive the situation and how and why their perceptions might differ from one’s own (compare Batson and Ahmad Citation2009). However, findings suggest, unhelpfully, that experiences of empathy are biased towards one’s own group, i.e. those who are like us. And counter-intuitively, empathy may exacerbate political polarization (Simas, Clifford, and Kirkland. Citation2020), creating an ‘empathy gap’ (Gutsell and Inzlicht Citation2012) towards political opponents. The driving force behind such empathy gaps is often party partisanship.

Polarization is related to partisanship (Carlin and Love Citation2018), but where the former refers to the (perceived) distance between parties, the latter refers to people’s affiliation with specific parties. This affiliation can forge very strong bonds among party members in terms of social identity or group identification (Conover Citation1984), creating effects of partisanship where partisans tend to perceive the world in ways that align with the interest of their party (and diverge from the interests of political opponents). Earlier studies clearly link partisanship to people’s political perceptions and in this study, we will take the analysis further and investigate whether partisanship also is a force behind perception of polarization.

It is here crucial to recognize how party partisanship relates to a party’s status as a political winner (in government) or loser (in opposition) (compare Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Citation2006; Gilljam and Karlsson Citation2015). In a two-party system, party affiliation and winner/loser-status normally coincide, as one party is in government when the other is not. However, in multi-party parliamentary systems, governments are often formed by coalitions rather than a single party. This means that a party and its elected representatives end up as members of a political team of parties, either a winning ruling majority coalition or a losing opposition. This team membership fundamentally affects party members and representatives in different ways, and winner-loser effects show up in many ways, for example in people’s trust in public authorities, their satisfaction with democracy or the economy, etc., where those aligned with winner parties normally are more content and losers more dissatisfied (e.g. Esaiasson, Gilljam, and Karlsson Citation2013; Hooghe and Okolikj Citation2020).

These winner-loser effects differ from effects of classical party partisanship in that members of the same party may find themselves in different political teams (winner-loser-wise) over time and in different tires of government or municipalities. To be a winner or loser is thus not inherent to belonging to a particular party. However, the winner-loser effects are intertwined with effects of party partisanship, as it is party affiliation that determines winner-loser status and aligns party interests with other parties in the same ‘political team’.

Belonging to a winning or losing political team involves emotional reactions, with shared pride in victory and bitterness in defeat. Belonging to a group, either in or out of power, also generates different experiences; with actors in winning majorities regularly overcoming resistance while actors in opposition are more likely to encounter obstacles and must work harder to achieve their political goals. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, all members of the ruling majority have a shared responsibility for decisions made and results achieved during the election period. In both success and failure, they are all in the same boat and share an interest in defending their actions to critics. Opposition members, on the other hand, all have the incentive to (re)gain political power, and even when the opposition is split between very different political groups, they share a common enemy and an interest in presenting the ruling coalition in a less favourable light.

Taking all these factors into account, this means that belonging to a winning or losing political team is likely to shape actors’ perceptions of their opponents and the political distance between them, i.e. polarization. And when differences in perceptions are greater between political teams than within them, it is, by definition, a winner-loser partisanship effect, especially when the composition of political teammates, to whom actors are partisan, may vary from situation to situation depending on the parliamentary setting.

Most studies concerning perception of polarization and partisanship have focused on citizens and their views on the societies in which they live. However, for political elites – especially elected political representatives – perceptions of polarization and partisanship are not just a general reflection on the state of society but concern their everyday lives and their deliberations and relationships with colleagues in an elected assembly. The need for more knowledge of relationships between political representatives is highlighted by findings from earlier studies, which note that the greatest variation in perceptions of polarization among representatives lies among individuals within the same elected assembly, rather than between different assemblies (Skoog and Karlsson Citation2018). It appears that politicians within the same elected assembly may perceive the level of polarization very differently.

Furthermore, we know from earlier studies that both partisanship and polarization are linked to trust (Carlin and Love Citation2018). Trust is a personal characteristic that affects an individual’s dispositions and perceptions (Newton Citation2007), aspects that are crucial in initiating, establishing, and maintaining social relations (Balliet and Van Lange Citation2013). Carlin and Love (Citation2018) argue that partisanship and trust are closely related, as partisanship tends to cause trust gaps in relation to opponents. They also show that such trust gaps are associated with how political polarization is perceived.

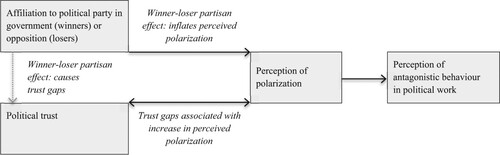

Previous studies have thus suggested that perception of political polarization is associated with partisanship and trust as well as with fostering negative views of opponents, jeopardizing cooperation, hampering political influence, and leading to acts of disrespectful and antagonistic behaviour among political actors. Causal relationships between these phenomena are hard to establish, however, we would argue that winner-loser partisanship is a driving force, in the sense that an individual’s current perceptions and behaviour are much more likely the result of being a winner or loser in the previous election, rather than the other way around.

The aim of this article is to study why politicians in the same elected assembly perceive political polarization differently, as well as whether and how this influences their behaviour. We are especially interested in analysing potential effects of two factors that previous scholars have suggested are important in shaping how people experience social and political situations: winner-loser partisanship and trust. We will also investigate whether and how perceptions of polarization are related to perceptions of antagonistic behaviour among political parties in the everyday work of governing.

A study of perceptions of polarization among politicians places major demands on the data. A study such as this would ideally require as many units of analysis (individual politicians) as possible, clustered in numerous different contexts (elected assemblies) with valid and identical indicators of different forms of party conflicts as well as information about the parliamentary situation in terms of governing coalitions and oppositions as well as experience of trust. A comparative local government approach is therefore an ideal research design. The analysis in this study is based on data from a survey conducted in 2012–2013 among all local councillors (9,725 respondents, i.e. a 79 per cent response rate) in Sweden’s 290 municipalities (Karlsson and Gilljam Citation2014). On this basis, our research questions are:

To what extent do partisanship and levels of trust affect perceptions of political polarization among local councillors in Sweden?

To what extent do perceptions of political polarization explain antagonistic behaviour among local councillors in Sweden?

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses what perception of political polarization is, how partisanship and trust can be expected to affect it, and concomitantly, how political polarization is related to antagonistic behaviour. Section 3 presents our case and discusses methodological aspects and sources of data, as well as the indicators for the dependent and independent variables. Section 4 presents our findings and Section 5 discusses how partisanship and trust affect perceptions of political polarization and what implications this might have for strengthening democratic practices.

Effects of partisanship and trust on perceived polarization and antagonistic behaviour

Polarization is the distance between opposing opinions and interests, i.e. the degree of dissent between political parties. Differing opinions and interests are a key mechanism in a functional democracy. Political parties are created to represent different social groups, political ideas, and programmes. Tensions between parties often concern disagreements over political principles and issues. Parties might disagree on political objectives or what constitutes a good society, and parties with similar objectives might differ on how they should be pursued (DiMaggio, Evans, and Bryson Citation1996; Bakker et al. Citation2015). A high degree of political dissent between parties means that their positions on political issues are a long way apart; whereas a low degree means that their positions are more similar. Earlier studies have also found that political dissent is of major relevance to the parliamentary arena (Lantto Citation2005; Skoog Citation2019, Citation2021). In the context of this study, polarization constitutes determinants of perceived policy differences between political opponents.

Effects of partisanship and trust

Perceptions of polarization are likely to be affected by many different aspects. Among earlier studies, two interrelated factors stand out in particular: winner-loser partisanship and trust These factors are, on the one hand, distinct social qualities that are based in how we perceive ourselves, our relationships, and political institutions in general. Earlier studies have shown, on the other hand, that the factors may also be dependent on one another, as partisanship is associated with trust gaps (Carlin and Love Citation2018). Consequently, in a study where the effect of one of the factors is estimated, the effect of the other must be checked.

There is no polarization between opponents without combatants, and in a parliamentary democracy they are constituted by political teams in the form of parties or coalitions of parties. Belonging to a political coalition or party and being its representative constitutes more than adherence to an ideology upon which political programmes are built. It is also about being a member of a group – how one identifies (see for example, de Vries and van Kersbergen Citation2007). Identifying with a group, i.e. group identity, entails the incorporation of group membership into the self-concept (Conover Citation1984, 761; Huddy Citation2003). From this perspective, being a member of a party or coalition is not simply about a set of shared beliefs or values, but also concerns feelings of psychological attachment to a political group (Campbell et al. Citation1960; Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Citation2002; Mason Citation2015). Scholars have found evidence that how one identifies can foster partisanship (Greene Citation2004), which in turn has significant effects on both behaviour and perceptions. Supporting a team may alter one’s perception of events, and in terms of basic psychological effects of group identity and partisanship, there are similarities between politics and sports. Studies have been conducted of the reactions of people to their sporting team being defeated, with loyalty to a group involving emotional reactions and a shared pride in victory and bitterness in defeat. It also involves rationalization mechanisms in which defeat is attributed to external factors or foul play by the opposing team. This functions to protect the group’s standing and, by extension, one’s own sense of pride (Mann Citation1974).

From this perspective, affiliation with a political team could influence an actor’s perceptions of polarization and antagonistic behaviour, particularly if their team is in a winning or losing position. Such positions are determined by electoral results that shape the composition of governments, the positions of those elected, and who has influence over the political agenda. The winner/loser assignments have crucial effects for the positions of political actors in the battles to come, with each new debate or decision-making situation constituting a new fight to be fought and thus renewing the sense of winning or losing.

Scholars of political behaviour have previously demonstrated several vital effects of being a political winner or loser. For example, there is a tendency to prefer practices that are beneficial for the party and to interpret situations in a way that puts the party in a favourable light, i.e. the home team effect (Gilljam and Karlsson Citation2015; Holmberg Citation1999). We also know that candidates who have won an election are less supportive of proposals to change institutions, while those who have lost an election are more encouraging of such changes (Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Citation2006). These results could be interpreted as an effect of self-interest. However, winning is also associated with a greater democratic content (Blais and Gélineau Citation2007) and perceptions of electoral fairness (Kernell and Mullinix Citation2019), with winners more inclined to give positive evaluations of leaders, policies, and economic conditions (Anderson and Tverdova Citation2001; Ginsberg and Weissberg Citation1978). Winning consequently seems to put many things in a more positive light.

Being a political winner or loser also generates objectively different experiences as winning is associated with being in power. When the influence of individual political actors varies, the resistance they experience from their opponents will also differ, and when actors who are on the winning side regularly overcome all resistance in political processes, it is likely that their perception of polarization will be lower. Conversely, political actors on the losing side are more likely to experience obstacles in their efforts as they must work harder to achieve their political goals. Those most deprived of influence may even perceive their political efforts as a perpetual struggle against invincible opponents.

However, there are studies of voters, where economic perceptions are shaped to a greater extent by economic realities than by partisanship (see for example Lewis-Beck, Nadeau, and Elias Citation2008; de Vries, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2018; Okolikj and Hooghe Citation2022). As the focus here is on political representatives, we argue that, while these results are relevant, there is still a need to study whether there is a winner-loser partisanship effect.

Moreover, as the ruling majority bears more responsibility for policy decisions, it is plausible that they are exposed to critique and conflicting views from citizens, which might heighten their perceptions of polarization. Based on the works of earlier scholars, we nevertheless argue that mechanisms such as group identity, winner-loser partisanship and differing experiences of political work all affect actors’ perceptions of polarization in the same direction:

H1. Representatives of parties in the ruling majority (”the winners”) perceive polarization between political opponents as being of a lower magnitude than representatives of parties in opposition (“the losers”)

A possible interpretation of this correlation is that polarization has an effect on trust. For example, among voters, low levels of trust lead to protest votes, and voters with a high level of trust are perhaps more likely to vote for established parties. This creates a situation where trust leads to partisanship.

However, trust is not restricted to personal dispositions and characteristics; it is also dependent on life experiences. The degree to which actors have been personally involved in a situation or event has a major influence on their perceptions of the world (Jervis Citation2017). Political representatives are not merely observers, they are active participants in political processes that form their impressions of actors and institutions. They have experiences that are likely to shape their trust in the specific local actors and institutions with which they are engaged. This means that we can expect those with a high level of specified trust in local actors and institutions to perceive less polarization. Even though causality is impossible to prove, our hypothesis relating to generalized and specified trust is:

H2. Representatives with high levels of trust perceive polarization between political opponents as having a lower magnitude than representatives with low levels of trust.

Effects on perceived antagonistic behaviour in political processes

Perceptions of polarization between political opponents may also be connected to the quality of the relationship between actors. While causality is hard to pin down, we share the position of most earlier scholars that it is more likely for opinions to influence behaviour than the other way around. For example, earlier studies teach us that the distance between interests and opinions in elected assemblies may influence the political climate and how political actors behave towards each other. Antagonistic behaviour is a concept that refers to acts of open critiquing of other political parties and disrespectful strategic actions in order to stop other actors from exerting political influence (Lantto Citation2005; Skoog Citation2019). In contrast, cooperative behaviour entails parties downplaying existing party differences and endeavouring to achieve agreement across party lines. Studies of coalition formation show that there is a greater likelihood of cooperation between parties with similar positions on political issues, while parties that are further apart will have trouble cooperating (Adams and Merrill Citation2009; de Swaan and Rapoport Citation1973). This illustrates the fact that there is a relationship between how far apart – or close together – political positions are and how party representatives behave towards each other. However, the dimension of antagonistic behaviour is a wider phenomenon than is discussed in the literature on coalition formation, comprising relationships between all parties, not just the partners within a coalition. High levels of polarization might foster a negative view of political opponents (so-called affective polarization) (Abramowitz and Webster Citation2018; Hetherington Citation2009; Mason Citation2015; Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Citation2012; Westfall et al. Citation2015; Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Citation2006), and lead to increases in antagonistic behaviour in everyday political situations (Skoog and Karlsson Citation2018).

However, as this study’s focus is on perceptions, it is important to recognize that causal relations between opinions and behaviour are more convoluted. If polarization of political views among parties is more likely to affect political behaviour than vice versa, it is not necessarily the case that people’s perceptions of polarization independently affect perceptions of the opponent’s behaviour. It is for example possible that politicians’ perceptions on whether their opponents behave constructively or antagonistically may colour their perception on whether these opponents’ positions on policies are closer or further away from their own.

Acknowledging the problems of establishing causal relationships, it is still worth testing whether assumptions in earlier studies that heightened levels of actual polarization among political actors is accompanied by increased actual antagonistic behaviour in political processes also in the realm of perceptions of these phenomena.

H3: Heightened levels of perceived political polarization among political actors is associated with increased perceptions of antagonistic behaviour in political processes

Methodology

The Swedish case

These hypotheses will be tested in relation to data from Swedish local governments. Sweden is a unitary, decentralized state, with the degree of ideological polarization remaining at a high level over a long period of time (Oscarsson et al. Citation2021), and with political parties represented at all tiers of government. Members of local councils are elected on party mandates in local elections and are responsible for issues across the entire political spectrum, from land allocation to childcare services (Hesse and Sharpe Citation1991; Loughlin, Hendriks, and Lidström Citation2011). There is also a high level of party politicization in Swedish local politics (Klok and Denters Citation2013), with the system based on parliamentary principles (Bäck Citation2003).

It is often claimed that one difference between politics at local and national level is that national politics is characterized to a greater extent by polarization and conflicts between political parties. However, while earlier studies have described a situation in which Swedish local politics was dominated by consensual democracy until the 1950s and 1960s, there has been an increase in party polarization in subsequent decades. In addition, even though norms of consensual democracy are still present in the discourse surrounding Swedish local democracy, this trend has led to a more conflict-oriented approach in the municipalities, with local politics evolving towards majority rule and away from the traditional ideals of unity government (Lantto Citation2005; Skoog Citation2019). In summary, being a party-based political system based on parliamentary principles where political conflicts potentially focus on a wide array of issues makes Swedish local government an excellent choice for our study.

The survey

The data used in this study derives from the unique KOLFU survey of all local councillors in the 290 municipalities in Sweden that was carried out in 2012–2013. Depending on the size of the municipality, a local council in 2012 consisted of 31–101 councillors, elected on party lists in general elections every four years. The survey accumulated 9725 responses, which is a response rate of 79 per cent. The response rate was over 60 per cent in 85 per cent of the 290 municipalities. Overall, there are no major differences between the response rates of representatives from different political parties (Karlsson and Gilljam Citation2014).

Dependent variables: perceived polarization and antagonistic behaviour in political processes

The key dependent variable for H1 and H2 is the indicator for perception of polarization, which refers to the positions that political actors take on political issues. It is measured as follows:

In the KOLFU survey, the councillors were asked to consider the statement: ‘There are major policy differences between the ruling majority and the opposition’. The councillors responded on an eleven-point scale from ‘the statement is absolutely wrong’ to ‘the statement is absolutely correct’. In this study, this indicator is coded 0–10 when used as a dependent variable (and 0–1 when used as an independent variable). The mean value among all councillors on the 0–10 scale is 5.7 and the municipalities with the highest and lowest perceived degree of political dissent were Stockholm (7.7) and Tibro (1.7).

An additional dependent variable is introduced in order to test H3: the indicator for perceived antagonistic behaviour. We know from earlier studies that the distance between political actors’ opinions and interests has major consequences for levels of antagonistic behaviour. This refers to the climate in which politicians interact and practice their roles as representatives. In the KOLFU survey, the councillors were asked: ‘Is the political work [in your municipality] primarily characterised by consensus or party conflicts?’. The councillors responded on an eleven-point scale and the answers are coded on a scale from 0 (primarily consensus) to 10 (primarily party conflicts). The mean value among all councillors in Sweden was 4.4 and the municipalities with the highest and lowest perceived antagonistic behaviour were Landskrona (8.4) and Tibro (1.1).

The two variables on political polarization and antagonistic behaviour correlate (Pearson’s r = 0.22). This means that they are related phenomena, but only a limited part of the variation in one of the variables is potentially explained by the other.

Multi-level analysis

We know from earlier studies that the degree of polarization and political conflict at the local level is related to structural factors at the municipal level. Polarization is mainly explained by the size of the demos, while social fragmentation, fiscal stress and party contestation increase antagonistic behaviour. However, in this article we are not focusing on contextual and structural factors that might explain variation among municipalities. Instead, we are looking for factors at the individual level that explain why politicians in the same municipality perceive the degree of polarization differently. Fixed-effects linear multilevel regression models are therefore used in order to distinguish individual factors from factors at the municipal level. Using this method makes it possible to assess the amount of variation between municipalities (the intra-class correlation) by estimating a random-intercept-only model (null model).

Results of a null model analysis () show that 8 per cent of the variation in perceived political dissent is found among the 290 municipalities in which representatives are clustered, while 92 per cent of the variation is found among individual representatives. About 21 per cent variation in perceived antagonistic behaviour is found at the municipal level, while 79 per cent is found among individual representatives. The variation among representatives within the municipalities is thus much greater than the variation between municipalities. It is this individual variation, where councillors in the same council disagree on the polarization levels, that is the focus of this article.

Table 1. Perceived political polarization and antagonistic behaviour. Multilevel regression analysis – varying intercept only model.

Main independent variables

The first hypothesis (H1) concerns the effects concomitant on being a political winner or loser. In this context, we will use two indicators: primarily parliamentary position (being part of the ruling majority or the opposition), and as a complement, formal rank.

After local elections, the winning parties form a ruling majority in all municipalities. The governing coalitions, which can vary greatly in size and composition, normally govern the municipality throughout the entire election period (Bäck Citation2003). Some 54 per cent of Swedish local councillors represent parties that are part of the local ruling majority (or sometimes a ruling minority), and 46 per cent are members of opposition parties.

However, being part of the majority or the opposition is not the only factor that determines whether politicians are winners or losers. There is a clear hierarchy in each municipality, with councillors having a higher and lower formal rank, which also corresponds with their perceived influence over political affairs (Karlsson and Gilljam Citation2014). The experiences of a high-ranking opposition councillor may be more similar to a political winner than a marginalized backbencher from a party in the ruling majority. In this analysis, a formal rank index is used as indicator, with the most highly ranked offices, chairs of executive boards – ‘the mayors’ – and chairs of councils having the value 1. The following ranks and their values are: deputy chair of the executive board, the council, as well as chairs of council committees: 0.8; members of the executive board and deputy chairs of council committees: 0.6; members of council committees and deputy members of the executive board 0.4; deputy members of council committees 0.2; and councillors with no other assignments (i.e. backbenchers): 0.

As councillors in the governing majority are more likely to be appointed to a higher post, on average, majority members have a higher value in the formal position index (0.53) than opposition members (0.43). By including the formal rank indicator alongside the parliamentary position indicator (the prime indicator for winner/loser) in the models, the effect of parliamentary position is controlled for spurious effects of formal position.

The second hypothesis (H2) concerns the effects of trust. The primary indicator for general, or interpersonal, trust is based on the question, ‘In your opinion, to what extent is it possible to trust people in general?’, where the responses were provided on an eleven-point scale, from ‘it is not possible to trust people in general’ (here: 0) to ‘it is possible to trust people in general’ (1). Ideally, an indicator for general trust in the political system of the country as a whole should be included in the model. However, as no such question was included in the survey, a complementary indicator for general democratic satisfaction is used in the model, based on the survey question, ‘On the whole, how satisfied are you with how democracy works in Sweden’, where responses were provided on a four-point scale from great satisfaction (here: 1) to great dissatisfaction (0). Satisfaction is not the same as trust, though interpreted carefully, our hope is that this indicator will provide information on whether the councillors’ view of the political system as a whole is positive or negative.

In addition, we will use two indicators that concern the role of specified local political trust as an intermediary factor: Perception of the responsiveness of the ruling majority and trust in the Executive Board. The first indicator is based on the survey question, ‘In your opinion, to what extent has the governing majority in your municipality attempted to satisfy the will of the people after the last election?’, followed by an eleven-point response scale from ‘to a very little extent’ (here: 0) to ‘to a very great extent’ (1). The indicator for trust in the local Executive Board is based on the question, ‘How much trust do you have in the way the following institutions perform their work: [the Executive board in your municipality]?’, where the responses were provided on an eleven-point scale, from ‘very low’ (here: 0) to ‘very high’ level of trust (1).

Descriptive information regarding the dependent and independent variables used in this study are presented in , as well as bivariate correlations between the dependent and independent variables. Correlations among all independent variables, including control variables, are presented in .

Table 2. The variables of the analyses, descriptive information (mean, standard deviation and number of cases) and correlation (Pearson’s r) with dependent variables.

Table 3. Correlation analysis (Pearson’s r) among independent variables.

Control variables

In order to check the effects of our main independent variables, three party political variables are included in the models. The first concerns potential effects of ideology. In collectivist ideologies such as socialism and feminism, individuals are seen as members of different social groups with diverging interests, giving rise to power struggles and conflicts between them (Liedman Citation2012). It is therefore conceivable that socialist politicians will interpret party relations as more conflictual than followers of more individualistic or conservative ideologies. We therefore check for ideology by including a control variable for councillors representing The Left Party and The Social Democrats, classified here as socialists (42 per cent).

As representatives of the Sweden Democrats are in opposition everywhere, affiliation to this party is also checked to ensure that the effect of not belonging to a party in government is separate from the effect of being a Sweden Democrat. In addition, as earlier results indicate that the presence of a local (i.e. non-national) party could be a factor that exacerbates local conflicts (Skoog and Karlsson Citation2018), we also include membership of a local party as a control variable. About 3 per cent of the respondents in KOLFU are Sweden Democrats and 3 per cent represent local parties (both are somewhat underrepresented compared to other parties).

We also include demographic factors such as educational level, gender, and age as control variables. About 52 per cent of the respondents in KOLFU have a university education, with the respondents ranging in age from 18 (lowest = 0) to 89 (highest = 1), with a mean age of 53 (0.49), and 43 per cent of the respondents are women.

Further, we have also included a number of variables at the municipal level as control variables. One category is the structural variables relating to social fragmentation in the locality (income inequality/Gini-coefficient; ethnic heterogeneity/proportion of immigrants; centre/periphery balance), size of the municipality, fiscal stress (economic growth; solvency of local authorities), party sizes, and several indicators of political contestation (party concentration; size of the ruling majority; broad ruling coalition; contestation based on sizes of political blocks; frequency of shifts of power). The effects of these municipal level context variables are analysed in an earlier study where the dependent variable was the conflict level at the municipal level (Skoog and Karlsson Citation2018). Another category is the aggregated versions of the individual independent variables (i.e. for gender, the proportion of women on the council, for socialist ideology, the proportion of socialists on the council, etc.). The findings from these analyses on contextual effects will not be discussed in the analysis.

Model strategy

The analysis is carried out in 5 multilevel regression models. In model 1 (), the indicator for perception of political polarization is the dependent variable and the indicators for parliamentary position, formal rank, general democratic satisfaction, and interpersonal trust are included as independent variables along with all the control variables. In model 2, the indicators for local political trust (trust in the Executive Board; perceived responsiveness of ruling majority) are added as independent variables. In models 3–5, the indicator for perceived antagonistic behaviour is the dependent variable. In models 3–4 the independent variables are the same as in models 1 and 2 respectively.

Table 4. Factors explaining local councillors’ perception of polarization and antagonistic behaviour in their own municipality (multilevel regression analysis. two levels. estimates of fixed effects, SE in parenthesis).

The reason for adding the indicators of local political trust in a separate model is the relatively strong correlations between those indicators and antagonistic behaviour (see ). This model design enables us to keep the effects of local trust from corrupting the other results and to determine whether the effects of independent variables are direct effects or channelled through local political trust. Moreover, as we are not able to establish whether our interpretation of the correlation between the two is correct, a different causal relationship is possible. However, if the hypothesis is to be trusted, then our interpretation is reasonable. In model 5, the indicator for perceived polarization is introduced as an independent variable in relation to antagonistic behaviour in political processes.

If H1 is correct, we would expect significant negative effects of being a member of a ruling majority and of having a higher value in the formal rank-index, i.e. political winners perceive polarization levels to be of a lower magnitude than political losers. If H2 is correct we would expect a negative effect of having high levels of interpersonal trust, a negative effect of having a high level of general democratic satisfaction, a negative effect of perceiving the local governing majority as responsive and having high levels of trust in the Executive Board, i.e. representatives with high levels of trust perceive that polarization levels have a lower order of magnitude. If H3 is correct, we would expect positive effects of perceived political polarization on perceptions of antagonistic behaviour in political processes, i.e. an increased level of perceived political polarization leads to an increase in antagonistic behaviour in political processes.

In order to facilitate comparisons of the effects produced by the analysis, all continuous independent variables are recoded in the models, so that 1 represents the maximum value and 0 the minimum value of each variable. Independent variables are not standardized in any other way. In all analyses, the two dependent variables (political dissent and perceived antagonistic behaviour) are coded as 0–10.

Results

The results of the multiple multilevel regression analyses are presented in .

In models 1–2, being a member of the ruling majority has a negative effect on perception of polarization. This is in line with H1, i.e. that politicians on the winning political side perceive polarization to be of a lesser magnitude. The results of the other indicator of winner and loser, the formal rank index, also produce negative effects in all models that are in line with H1, however, these results are not statistically significant. This means that formal position has no effect on perceived polarization. With regards to H1, this means that aspects of winner/loser related to party membership and partisanship are more relevant than individual positions and, given that caveat, H1 is confirmed. This confirms that being part of a ruling party coalition or the political opposition fosters a specific form of winner-loser partisanship which affects politicians’ perceptions.

Results from models 1–2, where perceived polarization is the dependent variable, show that the indicators for generalized trust have no effects on perception of polarization. Furthermore, results in model 2 indicate that none of the indicators of specified local trust have a statistically significant effect on perception of polarization, thus contradicting and not confirming H2. This implies that trust has no effect on how representatives perceive polarization between political opponents.

Results of model 5, where perceived antagonistic behaviour is dependent variable, show that the indicator for perceived political polarization, i.e. political dissent, produces a statistically significant and positive effect that is in line with H3. This implies that H3 is confirmed and that an increase in perceived polarization between the majority and opposition is accompanied by an increase in antagonistic behaviour in political processes. Results of models 3–5 also show that two indicators for winner and loser, i.e. (primarily) being a member of the governing majority and formal rank index, have a negative effect on antagonistic behaviour. However, in model 5, the effect of the formal rank index is not statistically significant when both political dissent and local political trust are introduced in the model. In short, this implies that politicians who are winners tend to perceive levels of polarization and antagonistic behaviour as being of a lower order of magnitude.

Further, results from models 3–5 indicate that general democratic satisfaction is associated with perceived antagonistic behaviour and that interpersonal trust has a weaker, but nevertheless significant, influence. A reasonable interpretation is that representatives who have more generalized trust tend to experience a lower level of antagonistic behaviour. Effects of both indicators are partly direct, partly channelled through local political trust. Specified local trust has negative effects on antagonistic behaviour, i.e. people who have higher trust in the Executive Board and perceive the ruling majority as more responsive towards citizens also tend to experience antagonistic behaviour in political processes as being of a lower magnitude. These results indicate that politicians who have higher levels of trust perceive a lower level of antagonistic behaviour ().

Figure 2. Results on the relationship between partisanship, trust, perceived polarization and antagonistic behaviour.

Note: The winner-loser partisan effect on trust (in grey) is controlled for, and confirmed, in a control analysis not presented in this paper.

Turning to results concerning control variables: the results from models 1 and 2 show that being a socialist has a substantial positive effect. In model 3, being a socialist also has a positive effect – weaker than in models 1–2, but still significant. However, in model 5, where antagonistic behaviour is the dependent variable and perceived polarization is introduced as an independent variable, the positive effect of being a socialist is no longer significant. This implies that being a socialist has a direct positive effect on the perception of polarization, but only a weaker and indirect effect on antagonistic behaviour – via political dissent. A plausible interpretation is that perception of political positions is affected by ideology while behaviour is not.

We also know from earlier studies that the presence of local protest parties is associated with an increase in polarization and antagonistic behaviour (Skoog and Karlsson Citation2018). However, our results show that it is not the representatives of local protest parties who perceive a heightened polarization. Instead, it seems to be the other members of the assembly that experience an increased level of polarization when local protest parties enter a parliamentary arena. Furthermore, previous results have indicated that the presence of the Sweden Democrats, despite being associated with party political turbulence at all tiers of government, does not affect the general level of conflict in local politics. The results of this study even suggest that Sweden Democratic’s representatives tend to perceive a lower level of conflict than representatives of other parties. However, since both local party representatives and, in particular, Sweden Democrats have lower levels of generalized trust, there are indirect effects on perception of polarization that provide contra-indications against these direct effects.

Male representatives and representatives with a higher level of education tend to perceive polarization as lower, but education and gender have no effect on perception of antagonistic behaviour. Results in all models indicate that older representatives tend to perceive a lower level of both polarization and antagonistic behaviour.

Overall, it is notable that the explanatory powers of the models at the individual level are much stronger in relation to perceptions of antagonistic behaviour than to perceived political polarization.

Let us agree to disagree!

Whereas earlier studies on what causes polarization have mainly focused on factors at the structural level, this study has put the focus on individuals’ perceptions of polarization. So, what contributions does this study make in relation to earlier research?

This study shows that there is a variation in individuals’ perceptions of polarization, in the form of perceived policy differences between political opponents, that in part can be explained by a factor we have named winner-loser partisanship. Being part of a political coalition or party also entails having emotional responses to group experiences, with each debate or political decision won, potentially producing a shared pride in victory, or shared grief for the losers after each lost battle. We also argue that, as influence over political affairs differs according to position in a political hierarchy, their experiences may vary. A principal result is that we find support for our hypothesis that political winners, i.e. members of the governing majority, will perceive that political polarization is of a lesser magnitude. However, we found no support for our indicator regarding formal rank, which implies that aspects of winner/loser related to party membership and partisanship are more relevant than individual positions.

Earlier research has established that partisanship is associated with trust gaps (Carlin and Love Citation2018; Karlsson Citation2017). However, the findings of this study contradict these results in that we found no effect of either general trust or specific local trust on perceived political polarization, and our analysis thus provides no support for a trust gap effect.

Another main finding is that our hypothesis provides support that an increase in perceived political polarization is associated with an increase in perceived antagonistic behaviour. We also found that high levels of general and local specific trust are correlated with perceived antagonistic behaviour. This might imply that high trust politicians are likely to perceive that levels of antagonistic behaviour are of a lesser magnitude.

Perhaps one reason that our results did not support the hypothesis that a trust gap will lead to an increase in perceived polarization and that instead we found that high trust politicians will perceive a lower level of antagonistic behaviour, is that earlier scholars may have interpreted polarization and antagonistic behaviour as the same phenomenon. However, even though both are affected by partisanship and have similarities, they are separate phenomena with different characteristics that are mostly caused by different factors.

It should perhaps not be surprising that politicians’ trust in both political institutions and other people have stronger correlations with how they perceive their colleagues and their behaviour than with their perceptions of their colleagues’ positions. The winner/loser hypothesis – that politicians on the winning political side would have the perception that polarization levels are lower – was supported. However, with regard to perceived antagonistic behaviour, the effects of being a winner or loser are closely related to effects of local trust.

Finally, this new knowledge regarding the importance of individual perception of polarization and the association of perceived polarization and antagonistic behaviour – and which factors form such perceptions – offers new insights into how democratic processes might be strengthened. Even though it is essential for a democracy that political representatives display their disagreements openly, there needs to be a balance between harmony and war for democracy to function. A healthy democracy demands that political actors display a certain degree of interpersonal understanding of the perspectives of others, and that it is sometimes better to respectfully agree to disagree than to go to war. Hopefully, this study has contributed some new and useful tools that might assist politicians in assessing each other’s positions and actions, and if this in turn could contribute to a more respectful communication of disagreements among political adversaries, a more inclusive and empathetic environment might be achieved.

Political empathy, not simply for an insider group but – especially – for political opponents, is not only important in facilitating interactions and respectful deliberations between political actors; respectful manners might also foster mutual trust. We know from earlier studies that individuals change their behaviour based on their trust in others (Balliet and Van Lange Citation2013), and findings from this study also specifically show that increased trust could lead to a decrease in antagonistic behaviour in political processes. This means that mutual trust and political empathy for the situations of other political actors can pave the way for the focus to be placed on the different political positions and interests of political actors that is a necessity for vigorous democratic systems.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (64.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Polarization sometimes refers to state and distance between parties/party coalitions at a certain time, and sometimes to a process where this distance increases over time (compare DiMaggio, Evans, and Bryson Citation1996). We focus here on polarization in the former sense.

References

- Abramowitz, A. I., and K. L. Saunders. 2008. “Is Polarization a Myth?” The Journal of Politics 70 (2): 542–555. doi:10.1017/S0022381608080493

- Abramowitz, A. I., and S. W. Webster. 2018. “Negative Partisanship: Why Americans Dislike Parties But Behave Like Rabid Partisans.” Political Psychology 39 (suppl. 1): 119–135. doi:10.1111/pops.12479

- Adams, J., and S. Merrill, III. 2009. “Policy-seeking Parties in a Parliamentary Democracy with Proportional Representation: A Valence-Uncertainty Model.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (3): 539–558. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000562

- Allport, G. W. 1961. Pattern and Growth in Personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Anderson, C. J., and Y. V. Tverdova. 2001. “Winners, Losers, and Attitudes About Government in Contemporary Democracies.” International Political Science Review 22 (4): 321–338. doi:10.1177/0192512101022004003

- Bäck, H. 2003. Explaining Coalitions. Uppsala: University of Uppsala.

- Bakker, R., C. De Vries, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, G. Marks, J. Polk, J. Rovny, M. Steenbergen, and M. A. Vachudova. 2015. “Measuring Party Positions in Europe The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File 1999–2010.” Party Politics 21 (1): 143–152. doi:10.1177/1354068812462931

- Balliet, D., and P. A. M. Van Lange. 2013. “Trust, Conflict, and Cooperation: A Meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (5): 1090–1112. doi:10.1037/a0030939

- Batson, C. D., N. Y. Daniel. 2009. “Using Empathy to Improve Intergroup Attitudes and Relations.” Social Issues and Policy Review 3 (1): 141–177.

- Blais, A., and F. Gélineau. 2007. “Winning, Losing and Satisfaction with Democracy.” Political Studies 55 (2): 425–441. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00659.x

- Bowler, S., T. Donovan, and J. A. Karp. 2006. “Why Politicians Like Electoral Institutions: Self-Interest, Values, or Ideology?” The Journal of Politics 68: 434–446. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00418.x

- Campbell, A., P. E. Converse, W. E. Miller, and D. E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: Wiley.

- Carlin, R. E., and G. J. Love. 2018. “Political Competition, Partisanship and Interpersonal Trust in Electoral Democracies.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (1): 115–139. doi:10.1017/S0007123415000526

- Conover, P. J. 1984. “The Influence of Group Identifications on Political Perception and Evaluation.” The Journal of Politics 46 (3): 760–785. doi:10.2307/2130855

- de Swaan, A., and A. Rapoport. 1973. Coalition Theories and Cabinet Formations. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Deutsch, M. 1958. “Trust and Suspicion.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 2 (4): 265–279. doi:10.1177/002200275800200401

- de Vries, C. E., S. B. Hobolt, and J. Tilley. 2018. “Facing up to the Facts: What Causes Economic Perceptions?” Electoral Studies 51: 115–122. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2017.09.006

- de Vries, C., and K. van Kersbergen. 2007. “Interest, Identity and Political Allegiance in the European Union.” Acta Politica 42: 307–328. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500184

- DiMaggio, P., J. Evans, and B. Bryson. 1996. “Have Americans’ Social Attitudes Become More Polarized?” American Journal of Sociology 102 (3): 690–755. doi:10.1086/230995

- Enders, A. M., and M. T. Armaly. 2019. “The Differential Effects of Actual and Perceived Polarization.” Political Behavior 41 (3): 815–839. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9476-2

- Esaiasson, P., M. Gilljam, and D. Karlsson. 2013. “Sources of Elite Democratic Satisfaction: How Elected Representatives Evaluate Their Political System.” In Stepping Stones. Research on Political Representation, Voting Behavior, and Quality of Government, edited by S. Dahlberg, H. Oscarsson, and L. Wängnerud, 39–58. Gothenburg: Department of Political Science. University of Gothenburg.

- Fukuyama, F. 1995. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Free Press Paperbacks.

- Gilljam, M., and D. Karlsson. 2015. “Ruling Majority and Opposition: How Parliamentary Position Affects the Attitudes of Political Representatives.” Parliamentary Affairs 68 (3): 555–572. doi:10.1093/pa/gsu007

- Ginsberg, B., and R. Weissberg. 1978. “Elections and the Mobilization of Popular Support.” American Journal of Political Science 22 (1): 31–55. doi:10.2307/2110668

- Green, D. P., B. Palmquist, and E. Schickler. 2002. Partisan Hearts and Minds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Greene, S. 2004. “Social Identity Theory and Political Identification.” Social Science Quarterly 85 (1): 136–153. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08501010.x

- Gutsell, J. N., and M. Inzlicht. 2012. “Intergroup Differences in the Sharing of Emotive States: Neural Evidence of an Empathy Gap.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 7 (5): 596–603.

- Hesse, J. J., and L. J. Sharpe, eds. 1991. Local Government and Urban Affairs in International Perspective. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Hetherington, M. J. 2009. “Review Article: Putting Polarization in Perspective.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (2): 413–448. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000501

- Holmberg, S. 1999. “Down and Down We Go: Political Trust in Sweden.” In Critical Citizens, edited by P. Norris, 103–122. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hooghe, M., and M. Okolikj. 2020. “The Long-term Effects of the Economic Crisis on Political Trust in Europe: Is there a Negativity Bias in the Relation Between Economic Performance and Political Support?” Comparative European Politics 18: 879–898. doi:10.1057/s41295-020-00214-5

- Huddy, L. 2003. “Group Identity and Political Cohesion.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, edited by D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, and R. Jervis, 511–558. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Iyengar, S., G. Sood, and Y. Lelkes. 2012. “Affect, not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (3): 405–431. doi:10.1093/poq/nfs038

- Jervis, R. 2017. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Karlsson, D. 2017. “Inter-level Trust in a Multilevel Political System.” Scandinavian Political Studies 40 (3): 289–311. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.12089

- Karlsson, D., and M. Gilljam. 2014. Svenska politiker: om de folkvalda i riksdag, landsting och kommun. Stockholm: Santérus.

- Kernell, G., and K. J. Mullinix. 2019. “Winners, Losers, and Perceptions of Vote (Mis)Counting.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 31 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edx021

- Klok, P.-J., and B. Denters. 2013. “The Roles Councillors Play.” In Local Councillors in Europe, edited by B. Egner, D. Sweeting, and P.-J. Klok, 63–83. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Lantto, J. 2005. Konflikt eller samförstånd? [Conflict or consensus?]. Stockholm: Akademitryck AB.

- La Porta, R., F. Lopes-de Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny. 1997. “Trust in Large Organizations.” The American Economic Review 87 (2): 333–338.

- Lewicki, R. J., and B. B. Bunker. 1996. “Developing and Maintaining Trust in Work Relationships.” In Trust in Organizations, edited by R. M. Kramer, and T. R. Tyler, 114–139. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., R. Nadeau, and A. Elias. 2008. “Economics, Party, and the Vote: Causality Issues and Panel Data.” American Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 84–95. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00300.x

- Liedman, S.-E. 2012. Från Platon till kriget mot terrorismen [From Plato to the War on Terror]. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag.

- Loughlin, J., F. Hendriks, and A. Lidström (eds.). 2011. The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mann, L. 1974. “On Being a Sore Loser: How Fans React to Their Team's Failure.” Australian Journal of Psychology 26 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1080/00049537408254634

- Mason, L. 2015. ““I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 128–145. doi:10.1111/ajps.12089

- McKnight, D. H., L. L. Cummings, and N. L. Chervany. 1998. “Initial Trust Formation in New Organizational Relationships.” Academy of Management Review 23 (3): 473–490. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926622

- Newton, K. 2007. “Social and Political Trust.” In The Oxford Handbook Political Behaviour, edited by R. J. D. Dalton, and H. D. Klingemann, 342–369. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Norén Bretzer, Y. 2005. Att förklara politiskt förtroende. Göteborg: Grafikerna i Kungälv.

- Okolikj, M., and M. Hooghe. 2022. “Is There a Partisan Bias in the Perception of the State of the Economy? A Comparative Investigation of European Countries, 2002–2016.” International Political Science Review 43 (2): 240–258. doi:10.1177/0192512120915907

- Oscarsson, H., T. Bergman, A. Bergström, and J. Hellström. 2021. Demokratirådets rapport 2021: polariseringen i Sverige. [The Democracy Council's Report 2021 Polarisation in Sweden]. SNS förlag.

- Putnam, R. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Princeton: Princeton university press.

- Riek, B. M., E. W. Mania, and S. L. Gaertner. 2006. “Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-analytic Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10 (4): 336–353. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4

- Robinson, S. L. 1996. “Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract.” Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (4): 574–599. doi:10.2307/2393868

- Simas, E. N., S. Clifford, and J. H. Kirkland. 2020. “How Empathic Concern Fuels Political Polarization.” American Political Science Review 11 (1): 258–269.

- Skoog, L. 2019. Political Conflicts – Dissent and Antagonism among Political Parties in Local Government. Göteborg: Brandfactory.

- Skoog, L. 2021. “Where Did the Party Conflicts Go? How Horizontal Specialization in Political Systems Affects Party Conflicts.” Politics & Policy 49 (2): 390–413. doi:10.1111/polp.12397

- Skoog, L., and D. Karlsson. 2018. “Causes of Party Conflicts in Local Politics.” Politics 38 (2): 182–196. doi:10.1177/0263395716678878

- Uslaner, E. M. 2000. “Producing and Consuming Trust.” Political Science Quarterly 115 (4): 569–590. doi:10.2307/2657610

- Uslaner, E. M. 2002. The Moral Foundations of Trust. New York: Cambridge university press.

- Westfall, J., L. Van Boven, J. R. Chambers, and C. M. Judd. 2015. “Perceiving Political Polarization in the United States: Party Identity Strength and Attitude Extremity Exacerbate the Perceived Partisan Divide.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 10 (2): 145–158. doi:10.1177/1745691615569849