ABSTRACT

In the 2019 European Union (EU) renewed Strategy for Central Asia, the promotion of democracy in the post-soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan is singled out as one of the key priorities. This article aims to examine whether there is an alignment between the EU self-perception on democracy promotion and its external perception in local media. The question is addressed through quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the EU key documents for Central Asia and local media outlets from 2019 to 2022, using the Nvivo software. The research findings indicate that both self- and external perceptions align in the context of the EU human rights promotion for Central Asia. Drawing upon these findings, this article argues that the EU democracy promotion endeavours are predominantly grasped in Central Asia within the sphere of human rights, while comprehension of other facets of the EU democracy promotion agenda remains intricate. Consequently, as the EU normative agenda faces ongoing scrutiny within Central Asia, it is advocated that the EU undertake a thorough reassessment of its approach in the region, aiming to foster deeper understanding and alignment with local perceptions.

Introduction

The European Union (EU), a firm advocate of global democracy, seeks stable, democratic, and economically thriving neighbours (European Union Global Strategy Citation2016). Central Asia, dubbed the EU’s ‘neighbor of neighbors' (Spaiser Citation2018), draws EU engagement due to its strategic interest and the EU's eastern enlargement, coupled with the recognition of region’s energy resources (Fawn Citation2022; Hoffmann Citation2010). Bilateral cooperation, governed by Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCAs), except Turkmenistan, and the EU-Kazakhstan Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA), forms the basis of EU-Central Asia connections. The 2019 Strategy guides interregional collaboration, emphasizing democratic values and prioritizing democratization in Central Asia (European Union Strategy for Central Asia Citation2019), succeeding the previous 2007 version (Korosteleva and Bossuyt Citation2019).

Examining perceptions is crucial for nuanced insights into policy efficacy (Elgstrom and Chaban Citation2015; Holsti Citation1970), with discussions on the EU democracy promotion agenda in Central Asia (Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011; Hoffmann Citation2010; Hönig and Tumenbaeva Citation2022; Sharshenova Citation2018) supplemented by the general Central Asian viewpoint on the EU (Arynov Citation2022a; Bekenova and Collins Citation2019; Ospanova, Sadri, and Yelmurzayeva Citation2017). Scholars have studied EU democracy and good governance promotion efforts in Central Asia, considering how they are perceived by different segments of the population (Arynov Citation2022b; Bossuyt and Davletova Citation2022; Spaiser Citation2018). A key question remains: Is there an alignment between the EU self-representation as an actor engaged in democracy promotion and its external perception in local media? This article addresses this question through quantitative and qualitative content analysis of key EU documents for Central Asia and local media outlets from 2019 to 2022. The data were sorted manually and analyzed using NVivo software (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). A transparent, fully structured Methodology section precedes the Results and Discussion sections.

The primary goal of this article is to examine the alignment or misalignment between the EU self-perception based on the legal framework and Central Asian media perceptions. Although the EU democracy promotion is perceived in Central Asia as a threat (Arynov Citation2021), there is no evidenced local media perception on the issue. In this article, we argue that the EU democracy promotion programme is primarily comprehensible to Central Asia only in the area of human rights, while comprehension of other facets of the EU democracy promotion agenda remains intricate. Our findings indicate that both self- and external perceptions align in the context of the EU promotion of human rights in Central Asia.

Grounded in the theoretical framework of ‘self’ and ‘external’ perceptions (Bengtsson and Elgström Citation2012; Elgstrom and Chaban Citation2015; Holsti Citation1970; Lucarelli Citation2007), the research distinguishes between EU normative power (Borzel Citation2022; Manners Citation2002) and cultural perspectives shaping its perception in non-European countries (Ariely, Zahavi, and Hasdai-Rippa Citation2023; Ariely and Zahavi Citation2023; Aydin-düzgit Citation2018; Chaban and Holland Citation2019; Elgstrom Citation2010; Holland Citation2005; Larsen Citation2014; Lucarelli and Fioramonti Citation2009; Olivier and Fioramonti Citation2010). The paper provides insights into EU normative roles, democracy promotion, and perceptions in Central Asia.

Below, the theoretical section covers democracy promotion, ‘self’ and ‘external’ perceptions frameworks, and literature on EU democracy promotion in Central Asia. The background section reviews EU democracy promotion instruments for the region. The methodology section details data collection, coding, analysis, and limitations. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion on self and media perceptions in Central Asia, presenting the results.

Conceptualizing democracy promotion and perceptions

Understanding democracy promotion

The promotion of democracy and foreign democratization has gained significant prominence in the foreign policy doctrines of the United States and the EU, particularly since the end of the Cold War (Kurki Citation2010). This agenda is rooted in the principles of western liberal democracy, as outlined by Dahl (Citation1989, 108–114), which continues to be central to contemporary debates on democratization (Diamond Citation2021). Democracy promotion is often understood as external ‘assistance,' ‘encouragement,' ‘support,' or ‘inspiration’ aimed at fostering democratization processes (Kurki Citation2010).

The European foreign policy approach to democracy promotion aligns with the constructivist concept of the EU normative power, as outlined by Manners (Citation2002). European aid for democracy promotion and development assistance can often overlap, as they both contribute to democratization efforts. According to Knack (Citation2004), this aid can have three primary mechanisms for promoting democracy:

Technical Assistance involves providing support and resources for electoral processes, strengthening legislatures and judiciaries as checks on executive power, and promoting civil society organizations, including a free press.

Conditionality is applied through mechanisms such as the EU's Generalized Scheme of Preferences (GSP) or GSP + . Compliance with democratic norms can be encouraged by offering trade benefits, such as exporting local products to the European Union without tariffs or tax duties.

Socioeconomic Development is focused on improving education and increasing per capita incomes are factors that can contribute to the democratization process. Enhanced education and higher incomes create conditions conducive to democratization (Knack Citation2004, 251).

Democracy promotion encompasses factors that influence pro-democratic socialization and the promotion of political debate and pressure within cooperative security groupings (Youngs Citation2010, 3).

Rustow (Citation1970) proposed an ambiguous suggestion that proponents of democracy should employ various tactics, such as pushing, misleading, seducing, or persuading non-democratic actors to encourage them to adopt democratic behaviours. The underlying premise is that the cost–benefit calculation for non-democratic actors needs to be altered. The maintenance of non-democratic norms should become more costly than accepting the expenses associated with transitioning to democratic standards. This shift in the cost–benefit analysis of elites is referred to as conditionality, and it is believed to eventually lead to democratization (Rustow Citation1970).

This analytical approach suggests that external actors have the capacity to utilize different means of democracy promotion, including political discourse and negotiation, capacity building, strategic counsel, and conditionality. These approaches aim to make the continuation of non-democratic governance costly for domestic political elites, thus incentivizing a transition towards democracy (Hoffmann Citation2010).

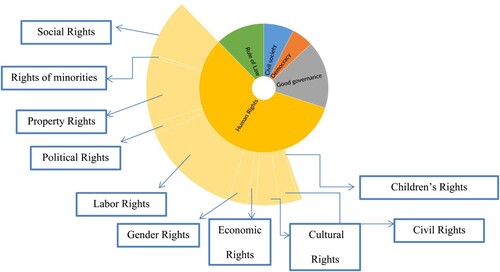

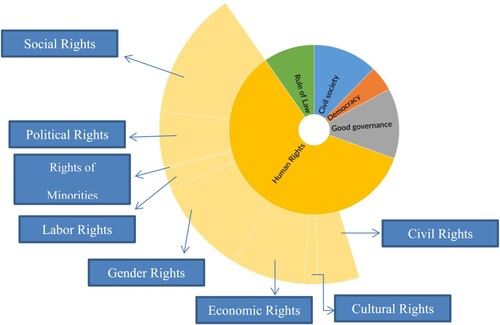

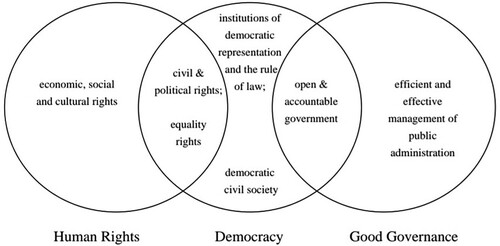

The EU, recognized as a significant normative actor (Manners Citation2002), actively seeks to share its expertise in areas such as good governance, the rule of law, and human rights through the aforementioned technical and development aid (Hönig and Tumenbaeva Citation2022), conditionality, and training mechanisms (Hoffmann Citation2010). These areas of expertise can be divided into different groups, as illustrated in , based on the work of Crawford (Citation2000) cited in Warkotsch (Citation2008).

Figure 1. Conceptual Linkages of Human Rights, Democratization and Good Governance. Source: (Warkotsch Citation2008).

This article primarily focuses on the EU democracy promotion efforts in the specific areas identified by Crawford (Citation2000), as categorized within multilateral and bilateral formats of cooperation with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The analysis in the article examines both the self-perception of the EU in these areas of democracy promotion and how it is externally perceived by the Central Asian states. By examining the self-perception and external perceptions of the EU democracy promotion initiatives, the article aims to shed light on any potential alignments or discrepancies between the EU's intended goals and how they are perceived by the Central Asian countries.

Defining the self- and external perceptions

To examine the alignment or misalignment between the EU self-perception and local media perceptions on the EU democracy promotion for Central Asia, we turn to the definitions of perceptions, which refer to the patterns of roles (Holsti Citation1970). Arguably, they can be understood as the impression or expectation of an actor's behaviour by others. According to Lucarelli (Citation2007), ‘roles … are determined both by the actor’s own perceptions of appropriate behavior and by the expectations of other actors'. Bengtsson and Elgström (Citation2012) define the political actor’s role by three main dimensions, such as role conception, role prescription and role performance. The role conception relates to the actor's self-perception or how they view their own role. The role prescription, on the other hand, pertains to the expectations placed on the actor's behaviour or the external perception of others. The role performance involves the assessment of the actor's actual activity or how well they fulfil their perceived role.

In this article, we focus on the issues of self- and external perceptions, which align with the concepts of role conception and role prescription. These terms can be used interchangeably to explore how the EU perceives its own role in democracy promotion and how it is perceived by others.

Based on the foregoing, we agree that the concept of political perception is divided into ‘self’ and ‘external’ types, defined by Elgstrom and Chaban as ‘identifiable political worldviews, with images of ‘self’ and relevant ‘others’’ (Elgstrom and Chaban Citation2015). Therefore, political self-perception is linked to how a subject positions itself and constructs an image around its identity and activities. Conversely, external perception refers to how others perceive the subject (Chaban, Elgstrom, and Holland Citation2006; Scheipers and Sicurelli Citation2007).

The concept of self-perception is manifested in the legal framework, rhetoric, and actions of the actor, with the role of news media being emphasized in shaping external perceptions (Brewer Citation2006; Elgstrom and Chaban Citation2015; Valkenburg, Semetko, and De Vreese Citation1999).

The media is situated at the intersection of information flows between elites and the public, making them significant contenders for the position of international image-shapers (Elgstrom and Chaban Citation2015). Media-generated images have the power to shape the perceptions of their audiences (Powlick Citation1995). As an illustration, mass media serves as a central source of economic news, significantly influencing Americans’ economic perceptions (Blood and Phillips Citation1995; Mutz Citation1994; Soroka Citation2006; Soroka, Stecula, and Wlezien Citation2015). Considerable experimental evidence exists, demonstrating the substantial influence of media coverage on perceptions of various issues (Iyengar and Kinder Citation1987; Nelson, Clawson, and Oxley Citation1997). Certain studies show that media coverage can strongly mold the attitudes and perceptions of specific audiences (Gilens Citation1999; Kellstedt Citation2003).

Literature review on the EU self- and external perceptions of democracy promotion

The EU self-perception centres on normative principles like democracy, human rights, and solidarity, promoting a positive self-image as a benevolent partner globally (Arynov Citation2022a). Established treaties, including Maastricht (Citation1992) and Lisbon (Citation2007), emphasize the EU's commitment to these values, guiding its international actions (Treaty of Maastricht Citation1992). The 2019 EU Strategy for Central Asia underlines the role of creating a conductive environment for civil society, journalists, and human rights defenders (The EU Strategy for Central Asia Citation2019). However, recent critiques label the EU democracy promotion in Central Asia as limited, self-interested, or fragile (Axyonova Citation2014; Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011; Hoffmann Citation2010; Hönig and Tumenbaeva Citation2022; Pierobon Citation2022; Sharshenova Citation2018; Wetzel, Orbie, and Bossuyt Citation2015). Diverse studies explore EU democracy promotion challenges in Central Asia. Hoffmann (Citation2010) notes hurdles in governance and democracy promotion at the government level, often driven by external aspirations rather than a genuine commitment to governance principles. Wetzel, Orbie, and Bossuyt (Citation2015) highlight a lack of an internally agreed democracy framework, hindering effective external promotion. Hönig and Tumenbaeva (Citation2022) link aid distribution in Central Asia to democratic setbacks within the EU and its member states. Bossuyt and Kubicek (Citation2011) propose a nuanced, tailored strategy acknowledging regional differences, focusing on specific aspects in each country. Axyonova (Citation2014) studies determinants influencing EU efforts in Central Asia, while Sharshevova (Citation2018) exposes a discrepancy between European normative rhetoric and self-interested behaviour towards the region. Axyonova and Bossuyt (Citation2016) find a gap between advocated civil society organizations and practical support of the EU, favouring certain groups. Keijzer and Bossuyt (Citation2020) explore the EU's evolving approach toward Central Asian civil society, favouring collaboration with professionalized groups. Overall, these studies call for more inclusive strategies of the EU supporting grassroots initiatives in Central Asia.

The EU normative agenda faces criticism not only in the context of Central Asia but also in other regions globally (Chaban et al. Citation2013; Fioramonti and Lucarelli Citation2009; Lucarelli Citation2014; Sicurelli Citation2015; Pardo Citation2015). Larsen's (Citation2014) findings suggest that, while the EU is seen as a development supporter, its normative role faces challenges globally. Cultural perspectives significantly shape these perceptions (Ariely, Zahavi, and Hasdai-Rippa Citation2023; Aydin-düzgit Citation2018; Chaban and Holland Citation2019).

The literature review sets the stage for addressing the fundamental question of aligning the EU's positive normative self-representation with external perceptions in Central Asia, emphasizing the complexity and multifaceted nature of these dynamics.

Background on the EU democracy promotion agenda for Central Asia

To investigate the alignment or misalignment between the EU self-perception and local media perceptions regarding the EU democracy promotion efforts in Central Asia, we delve into the background of the EU democracy promotion agenda for the region. Commencing in 1991, the EU's primary financial aid programme for post-Soviet states, known as Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Independent States (TACIS), was not specifically oriented towards democratization. Its main emphasis was on promoting trade and investment and enhancing government capacities (Hoffmann Citation2010).

In 2001, the IBPP-Support to Civil Society and Local Initiatives programme was established within the TACIS framework (Axyonova Citation2012). This programme aimed to provide funding for small-scale projects executed by European NGOs, local authorities, and non-profit organizations in the CIS countries, including Central Asia (2012). Between 2001 and 2007, a total of 43 projects received support through the IBPP in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, with grants ranging from €100,000 to €200,000 (2012). The programme concluded in 2007, except for Uzbekistan, where it continued until 2015 (Keijzer and Bossuyt Citation2020).

The Non-State Actors and Local Authorities (NSA/LA) programme emerged as a continuation of the IBPP under the newly established Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI) in 2007. It remained active from 2007 until 2014 when it was succeeded by the Civil Society Organizations and Local Authorities (CSO-LA) programme (2020). Both programmes embody a practical approach to external assistance, aiming to enhance the capacities of Civil Society Organizations in delivering services, particularly to the most vulnerable sections of society. Additionally, they strive to promote these organizations’ involvement in shaping policy decisions. Consequently, the emphasis is less on building institutions for post-socialist transitions and more on reducing poverty and providing essential services (2020).

The CSO-LA programme includes local authorities as potential beneficiaries, whereas the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) focuses on providing financial support to civil society actors engaged in human rights and democratic development issues (2020). It is worth noting, the EIDHR is an informal grouping of 43 NGOs operating at the EU-level, primarily in Brussels, with a separate budget established in 2004 (Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011). In addition, the EIDHR operates without the need for signing agreements with the governments of the target countries (Keijzer and Bossuyt Citation2020). In this respect, it should ‘complement the various other tools for implementation of EU policies on democracy and human rights' (Axyonova Citation2012). The present instrument is a successor to the European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights, which was created in 1994 and focused predominantly on human rights related actions. The more recent EIDHR programme documents put an equal emphasis on the support to human rights, democratization processes and strengthening civil society (2012).

One of the most recent projects operated under the EIDHR in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan was called BRYCA (Building Resistance in Youth in Central Asia), aimed at countering the influence of illegal hate speech and misinformation online and on social media. The project was completed in 2020 (EEAS BRYCA Factsheet Citation2020). However, the amount of funding granted for projects under this instrument is relatively small compared to the funds allocated for democratic efforts under the Development and Cooperation Instrument (DCI) (European Commission Citation2010).

Arguably, central to the EU’s democratic promotion purposes referred to the legal basis of the 2019 Strategy, PCAs and EPCAs are the Human Rights Dialogue and the Rule of Law Initiative.

The Rule of Law Initiative, being implemented by member states in collaboration with the Commission, has been begun towards the end of 2008, intended to improve collaboration between the EU’s judicial institutions and administration and its Central Asian partners in a primarily multilateral framework of a ministerial-level political conversation (Hoffmann Citation2010). But these efforts were focused on business and trade-related legal and judicial changes rather than reforms that directly influence governance and democracy (2010). The initiative’s impact was ranked as very low, arguing that it is simply another ‘political talking shop undercutting the EU’s resolve to back up strategic aims with actual action' (Isaacs Citation2009, 4). Currently, under the Initiative, the 2020 updated Rule of Law programme is going on until 2024 for all five Central Asian states with the EU € 8 million contribution (EEAS Rule of Law program Citation2020). The recent programme consists of three main actions: (1) facilitating the creation of a common legal space between Europe and Central Asia and enhancing human rights protection; (2) promoting transparency and action against economic crime; (3) promoting efficient functioning of state institutions and public administration for the main target groups such as national governments, officials of beneficiary institutions (judges, prosecutors, law enforcement officers, civil servants), business associations, national parliaments, line ministries, constitutional, supreme and ordinary courts, high judicial councils, legal professionals (EEAS Rule of Law program Citation2020).

Since 2008, the EU and Central Asian governments have elevated their interaction under the Human Rights Dialogue, making it a regular occurrence at a human rights ministerial summit (Russell Citation2019). In addition to these summits, meetings at various governmental levels, as well as civil society and media seminars, contribute to the ongoing discourse (2019). However, it has been argued that the promotion of a democratic electoral system and political rights of participation has received little attention in these dialogues (Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011). Only a few passing mentions have been made regarding the significance of independent media for the growth of a pluralistic society, as well as close cooperation with the Council of Europe's Venice Commission and the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) (2011).

Since 2019, the EU-Central Asia Civil Society Forum has served as a platform for civil society representatives from both regions to contribute to the advancement of EU-Central Asia collaboration (EEAS Factsheet on the EU-Central Asia relations Citation2022). The forum aims to generate new and innovative proposals and recommendations on how civil society can further participate and be more involved in local-level programming and policy execution related to the EU-Central Asia Strategy. It brings together representatives from civil society, researchers, media experts, the private sector, and government experts (EEAS Factsheet on the EU-Central Asia relations Citation2022).

Based on the above discussions on the EU-Central Asia relations, there is evidence of the EU's ongoing commitment to the development of democracy in the region (Hönig and Tumenbaeva Citation2022). Therefore, the theoretical approach proposed by Crawford (Citation2000) in remains relevant in reflecting the EU's democracy promotion agenda for Central Asia in recent times.

Methodology and limitations

To examine the alignment or misalignment between the EU self-perception and Central Asian media perceptions, the analysis was divided into two parts. First, we conducted a content analysis of key EU-Central Asia legal documents, focusing on Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCAs) with Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, as well as the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Kazakhstan. The 2019 renewed EU strategy for Central Asia is also examined, excluding Turkmenistan due to limited bilateral ties. This data for the document analysis was downloaded from the EU official websites in English language.

Second, we performed a content analysis on major Central Asian news outlets—Tengrinews.kz (Kazakhstan), 24.kg (Kyrgyzstan), Asiaplustj.info (Tajikistan), and Kun.uz (Uzbekistan). Media analysis covered news articles from January 2019 (the year of the most recent EU strategy adoption) to September 2022, using keywords ‘European Union’ and ‘EU.’ The data for media analysis was collected in Russian, reflecting the region's lingua franca (Ibrayeva et al. Citation2019) further the results were translated into English. Media analysis involved manual data collection, by sorting the headlines of the news pieces, covering all aspects of only EU-Central Asia cooperation, excluding the news pieces, which mention the EU, but not related to the topic. The selection process comprised two stages for each of the keywords ‘EU’ and ‘European Union’. Initially, a preliminary collection of articles was obtained. Subsequently, articles were systematically categorized based on their titles and content, focusing on themes pertinent to EU-Central Asia relations across various spheres of cooperation.

Using NVivo software for quantitative (word frequency, coding) and qualitative (word trees) techniques. Coding procedure includes manual sorting by two first authors of primary categories (‘democracy,’ ‘human rights,’ ‘good governance,’ ‘civil society,’ ‘rule of law’) based on Warkotsch’s (Citation2008) theoretical framework. ‘Human rights’ code includes sub-codes for detailed coverage.

This research has several limitations. First, there's subjectivity in data categorization. Second, it excludes additional EU-Central Asia documents, such as initiatives, programmes, action plans, strategies, and speeches by EU officials, which could potentially impact research findings. However, this omission is strategic for consistency in evaluating the broad democracy promotion agenda across EU-Central Asia relations. Third, the study doesn't incorporate alternative sources of local media or social media platforms, which could provide diverse insights, though verifying information accuracy on these platforms presents challenges (Ibrayeva et al. Citation2019; Ribeiro Citation2018). Furthermore, it doesn't address the domestic democracy situation and media censorship in Central Asia, considering the ongoing transition process, making progress evaluation from a European perspective challenging (Costa Buranelli Citation2021). Lastly, the article does not address the intricacies of media representations, public perceptions, and the policy-making processes within Central Asian states. Given that the research aims to identify the alignment or misalignment between EU democracy promotion efforts and their media reflections in Central Asia, it lacks a thorough examination of the policy-making procedures specific to these Central Asian contexts.

Results

Based on the content analysis of EU documents and Central Asian media outlets, there is an alignment between the EU’s self- and external perceptions regarding human rights promotion. Both analyses highlight human rights as central to the EU democracy promotion in Central Asia. However, the focus differs, since the EU documents address a broad range of rights with significant attention to good governance and the rule of law, while media sources emphasize social and gender rights, linking EU initiatives to broader European influence and support mechanisms.

Both EU documents and media sources show ‘human rights’ mentioned 62 and 64 times respectively, which is almost equal parameter. The cumulative human rights code count is higher in media analysis (259) compared to documents (244). EU documents discuss a wider range of rights, while media analysis highlights social and gender rights more prominently in local coverage.

Good governance is referenced more frequently in EU documents (72 mentions) than in media sources (58 mentions). The rule of law is also more prominent in documents (52 mentions) compared to media (42 mentions). Civil society and democracy receive fewer mentions in both analyses but are more frequently referenced in media (civil society: 53 mentions, democracy: 21 mentions) than in EU documents (both 32 mentions).

EU documents frame democracy promotion within a broader context of modernization, cooperation, and economic prosperity. Media sources perceive the EU’s efforts as tied to European influence, emphasizing border control, development, and educational assistance, suggesting arguably a view that the EU's democracy promotion is part of a larger geopolitical strategy.

EU documents implicitly promote democracy through themes like good governance and the rule of law, rarely using the explicit phrase ‘promotion of democracy.’ In contrast, media analysis explicitly mentions human rights and directly links these to the EU's democracy promotion efforts.

Discussion

The EU self-perception on democracy promotion towards Central Asia: content analysis of the EU documents for Central Asia

To perform a comprehensive content analysis of pertinent documents, we procured the 2019 EU Strategy for Central Asia, alongside the Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCAs) with Kyrgyzstan (1995), Tajikistan (2004), and Uzbekistan (1996). We examined the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) between the EU and Kazakhstan (Citation2015). However, our scrutiny revealed a noteworthy absence of the term ‘democracy’ among the frequently used words, as elucidated in :

Table 1. Top 20 frequent words in the EU documents for Central Asia.

This revelation holds significance, suggesting either the term ‘democracy’ is not prominently featured or that it embodies a nuanced and multifaceted concept (Warkotsch Citation2008). The quantitative analysis results indicate a minimal recurrence of the term ‘democracy,’ ranging from 0.01% to 0.02%, signifying its limited prevalence in the scrutinized documents. Conversely, the term ‘rights’ surfaced 2133 times, constituting 0.10% of the analyzed texts and ranking 11th among the top 20 most frequently used words. This observation implies that although the explicit mention of ‘democracy’ is subdued, the emphasis on ‘rights’ aligns with the broader EU democracy promotion agenda, underscoring its salience in the context of EU-Central Asia relations.

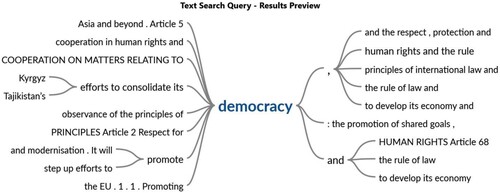

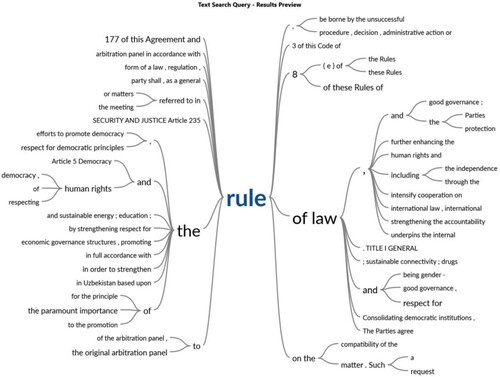

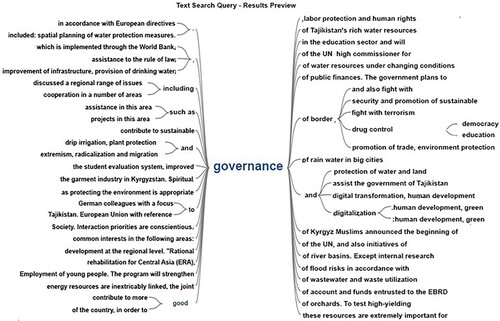

Furthermore, we conducted an analysis of word trees generated by NVivo, accessible in Appendix A, to explore key concepts. This method utilizes a graphical representation inspired by the traditional ‘keyword-in-context' technique (Wattenberg and Viegas Citation2008). These figures provide a visual depiction of word associations pertaining to ‘democracy’ (Warkotsch Citation2008), offering detailed linkages and valuable insights.

In Figure A1 (Appendix A), the interconnection of ‘democracy’ with phrases like ‘human rights,’ ‘rule of law,’ ‘develop economy,’ and ‘principles of international law’ suggests a nuanced understanding of democracy that spans legal, economic, and international dimensions. This implies a comprehensive approach to democracy promotion by the EU, acknowledging its multifaceted nature.

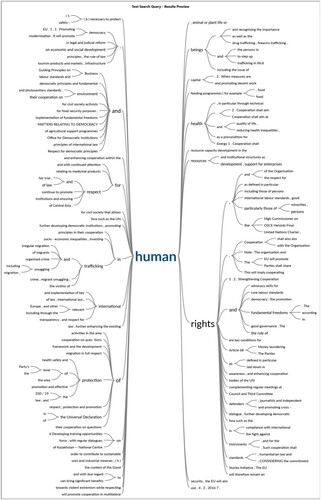

Figure A2 (Appendix A) underscores a close relationship between ‘human rights’ and terms such as ‘democracy,’ ‘rule of law,’ ‘migration,’ ‘labor standards,’ ‘health,’ and ‘civil society.’ The inclusion of phrases like ‘irregular migration' points to potential EU concerns, highlighting a specific focus on educational and job prospects in Central Asian nations. This reveals a strategic emphasis on addressing socio-economic factors within the human rights discourse.

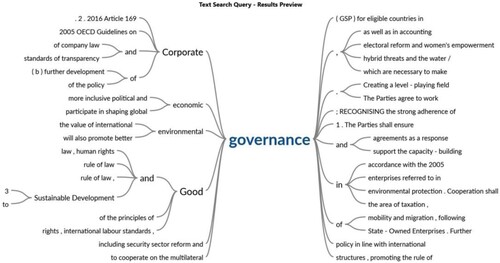

Figure A3 establishes a direct link between ‘good governance’ and terms like ‘rule of law,’ ‘rights,’ ‘reform,’ and ‘environment.’ This indicates a holistic governance approach that integrates legal, rights-based, and environmental considerations. The EU's engagement appears comprehensive, addressing multiple facets of governance in its democracy promotion efforts.

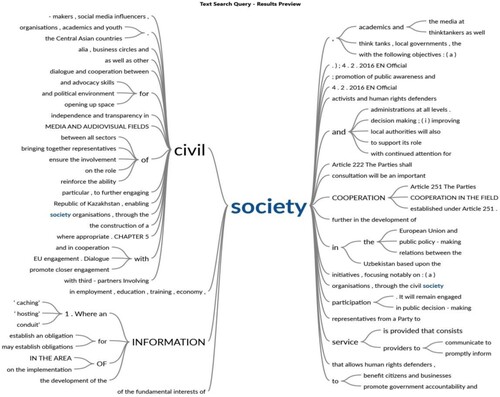

Figure A4 illustrates the correlation between ‘civil society’ and terms like ‘media,’ ‘human rights defenders,’ ‘academics and youth,’ and ‘think tankers.’ This emphasizes a multifaceted engagement strategy with diverse civil society actors, showcasing a broad and inclusive approach to civil society involvement in democracy promotion.

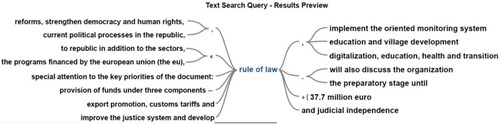

Figure A5 reveals a direct relationship between ‘rule of law’ and terms like ‘democracy,’ ‘good governance,’ ‘law,’ ‘rules,’ and ‘human rights.’ This empirical support for the theoretical overlap of democracy, rule of law, human rights, good governance, and civil society indicates a coherent and integrated approach by the EU in promoting these interconnected notions in Central Asia.

The observed direct matches between ‘democracy,' ‘human rights,' ‘good governance,' ‘civil society,' ‘rule of law,' and phrases such as ‘to develop economy,’ ‘economic and social development,' ‘economic governance,' and ‘economy' (Figures A1–A5) contribute to a nuanced understanding of the interplay between the EU democracy promotion agenda and economic development, suggesting a reciprocal relationship or mutual influence (Knack Citation2004).

The documents highlight the EU's vigorous commitment to democratic principles in Central Asia, as reflected in word pairings such as ‘promotion' and ‘effort' (Figures A1, A5). Additionally, the presence of a cluster containing terms like ‘promotion,' ‘protect,' and ‘respect' (Figure A2) underscores the EU's dedication to advancing, modernizing, and safeguarding democratic values in the region, which aligns with Kurki’s (Citation2010) suggestion on the democracy promotion.

Furthermore, coding of the identified notions, as illustrated in both and Figure A6 (accessible in Appendix A), accentuates that human rights codes emerge as the predominant elements associated with the EU democracy promotion efforts in Central Asia. The cumulative count of human rights codes stands at 244, aligning with the outcomes of the word-level analysis (), where the term ‘rights’ prominently features.

Table 2. Amount of codes’ references in the EU documents for Central Asia.

The spectrum of human rights codes encompasses diverse dimensions, encompassing social, minority, property, political, labour, gender, economic, cultural, civil, and children's rights. Notably, labour rights emerge prominently with 58 references, while ‘human rights’ itself appears 62 times across the analyzed documents. Conversely, children's rights and minority rights register the lowest number of mentions.

Further examination reveals substantial references to the domains of good governance (72 references) and the rule of law (52 references). In contrast, civil society (32 references) and democracy itself (32 references) are mentioned with the least frequency within the EU's democracy promotion agenda for Central Asia. This suggests that the civil society sector receives comparatively less attention within the EU's comprehensive agenda for promoting democracy in the region. This finding aligns with Axyonova and Bossuyt’s (Citation2016) observation of a disparity between the EU's practical support for civil society and the advocacy efforts of civil society organizations. Similarly, Keijzer and Bossuyt (Citation2020) examine the EU's approach towards Central Asian civil society, highlighting partnerships mostly with professionalized groups.

In summary, the content analysis of EU documents for Central Asia, as illustrated in Figures A1 and A5, indicates a strong association between democracy promotion and the EU's efforts towards modernization and cooperation in the region. This underscores the EU's proactive stance but very general in promoting and advancing democratic values and practices in Central Asia.

Although the explicit phrase ‘promotion of democracy' is infrequently used in EU documents for Central Asia, the word trees presented in Figures A1–A5 provide a more nuanced understanding of its multifaceted agenda for the region. This suggests that the EU considers democratic development, good governance, and the rule of law (as highlighted in ) as integral to promoting economic prosperity in the Central Asian republics.

Significantly, the EU places considerable emphasis on human rights in its Central Asia agenda. The prominence of the term ‘rights,’ ranking 11th among the top 20 most frequently used words, and the presence of 244 related codes underscore the EU's commitment to advancing and safeguarding various dimensions of rights, establishing human rights as a pivotal component of its broader democracy promotion strategy in the region.

Based on the results of the document analysis, it can be concluded that the EU's democracy promotion agenda encompasses a very broad context. This breadth arguably constrains its practical implementation (Axyonova Citation2014; Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011; Hoffmann Citation2010; Sharshenova Citation2018) and results in ineffective external promotion (Wetzel, Orbie, and Bossuyt Citation2015).

Central Asian perception on the EU democracy promotion based on the local media content analysis of news articles

For a meticulous and in-depth examination of local news coverage pertaining to EU-Central Asian democracy promotion relations, we implemented a content analysis strategy targeting the four preeminent news outlets: Asiaplustj.info, Kun.uz, Tengrinews.kz, and 24.kg.

Tengrinews.kz, acknowledged as Kazakhstan's largest information site, garnered recognition as one of the top 30 Kazakhstan news websites by Journalists.feedspot.com in 2023. As of June 24, 2021, cpj.org identified Kun.uz and 24.kg as the most widely followed general news websites in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, respectively. Additionally, Asiaplustj.info secured its position as the largest and most extensively read resource for Tajik users, attracting an approximate daily audience of 30,000 unique visitors, as per caa-network.org's ranking on October 30, 2019.

A comprehensive dataset comprising 270 articles was meticulously collected and subjected to scrutiny. The ensuing table furnishes the precise percentage distribution of the data across each media source ().

Table 3. Frequency of news articles on the European Union, according to news outlet and year.

Within the chosen media sources, 24.kg and Asiaplustj.info demonstrated the highest percentage of news articles, underscoring their prominence. In contrast, Tengrinews.kz and Kun.uz exhibited a similar volume of articles. Notably, the increased frequency of the terms ‘Tajikistan’ and ‘Kyrgyzstan’ suggests heightened media coverage in the outlets’ landscapes regarding the EU-Central Asian narrative in those states.

The outcomes of the word-level media content analysis reveal a strikingly low repetition percentage for the term ‘democracy’ in news articles from Central Asian outlets, ranging from 0.06% to 0.11%. This absence is further stressed by the term's omission from the top 20 most frequently used words in the analyzed articles.

delves into the frequency distribution of words such as ‘society,’ ‘development,’ ‘euro,’ ‘rights,’ ‘business,’ and ‘economy’ in the scrutinized news articles. The prominence of ‘rights’ in the word frequency hierarchy suggests a possible focus on the EU's human rights agenda in the purview of local media outlets.

Table 4. Top 20 frequent words in the Central Asian media outlets that mention the EU-Central Asia relations. Translated from Russian the frequency of words.

The EU emerges as a perceived supporter of financial development and a pivotal economic and business partner for Central Asia. The notable presence of ‘development’ and ‘euro’ among the top-ranking words signifies the EU's recognition as a provider of financial aid and a facilitator of economic growth. The recurrent mentions of ‘business’ and ‘economy’ further corroborate the prevailing perception of the EU as a significant economically in the region. This finding aligns with Arynov’s (Citation2022a) argument that the EU is associated economic opportunities in the region.

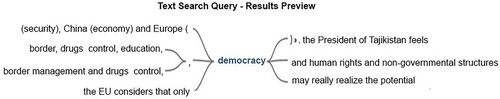

Drawing parallels with the content analysis of EU documents for Central Asia, we present word trees in Appendix B, specifically Figures B1–B5, elucidating linkages between key concepts – ‘democracy,' ‘human rights,’ ‘good governance,' ‘civil society,' and the ‘rule of law.'

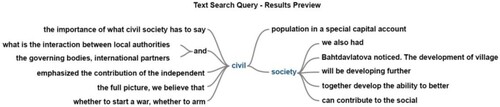

Figure B1 exhibits intricate connections between ‘democracy’ and key phrases such as ‘security,’ ‘borders’ (repeated 2 times), ‘drug control’ (repeated 2 times), ‘education,’ ‘EU,’ ‘Europe,’ ‘human rights,’ and ‘non-governmental structures.’ These linkages suggest a discernible interrelation between democracy and these thematic elements within the Central Asian context. The findings imply that the EU's democracy promotion efforts are closely perceived as tied to security, border management, drug control, education, and human rights in the region.

In Figure B2, a direct linkage emerges between ‘human rights’ and specific terms like ‘democracy’ (occurring 4 times), ‘democratic processes’ (occurring 2 times), ‘rule of law’ (occurring 4 times), ‘EU’ or ‘European Union’ (occurring 4 times), ‘education’ (occurring 2 times), ‘economic development’ (occurring 1 time), and ‘border control’ (occurring 1 time). This analysis signifies the entwined nature of human rights with democracy, rule of law, and European institutions in the Central Asian media discourse.

Figure B3 presents a clear association between ‘good governance’ and terms such as ‘water resources’ (appearing three times), ‘human rights’ (appearing once), ‘rule of law’ (appearing once), and ‘project’ and ‘program’ (appearing once each). Phrases like ‘border control’ and ‘EU’ recur consistently across Figures B1–B3. This interplay underscores the multifaceted nature of good governance, perceived by Central Asian media outlets as encompassing water resource management, human rights considerations, rule of law, and project-oriented initiatives, all within the overarching framework of EU involvement.

In Figure B4, a close relationship is depicted between ‘civil society’ and terms like ‘local authorities,’ ‘governing bodies,’ and ‘development’ (each repeated once). This signifies that the EU's approach to Central Asian civil society is observed as engagement with local authorities and governing bodies in Central Asian media outlets.

Figure B5 illustrates a direct link between ‘rule of law’ and terms such as ‘democracy’ (occurring once), ‘human rights’ (occurring once), ‘reforms’ (occurring once), ‘EU’ (occurring once), ‘health’ (occurring once), and ‘education’ (occurring twice). This indicates a local media understanding of the rule of law, encompassing democracy, human rights, reforms, health, and education within the EU's democracy promotion agenda in Central Asia.

Connections between ‘democracy’, ‘human rights’, and ‘good governance’ with terms like ‘border’ and ‘border control’ (repeated in Figures B1–B3), as well as ‘EU’ and ‘Europe’ (repeated in Figures B1, B2, B3, and B5), suggest a perceptual link between democracy and European identity in local media. Recurrent mentions of ‘border’ and ‘border control’ indicate a positive association between EU projects like BOMCA and CADAP and the intertwined aspects of border security, drug control, and democratization in the eyes of Central Asians.

Figures B2 and B5 highlight alignments between ‘human rights,' ‘rule of law,' and the phrases ‘economic development' and ‘development.' This echoes the word-level analysis, where ‘development' emerged prominently (as stated in ), enhancing our understanding of the interconnected pursuits of democracy promotion and development by the EU in Central Asia. This implies a symbiotic relationship, suggesting that an educated populace and democratization serve as mutual catalysts for economic growth (Knack Citation2004).

The inclusion of ‘education’ in connection with ‘democracy,’ ‘human rights,’ and the ‘rule of law’ (as depicted in Figures B1, B2, and B5), alongside the explicit connections observed between democracy, human rights, and the rule of law (across Figures B1, B2, B4, and B5), underscores the intricate interplay of these ideas within the perspectives on the EU held in Central Asia.

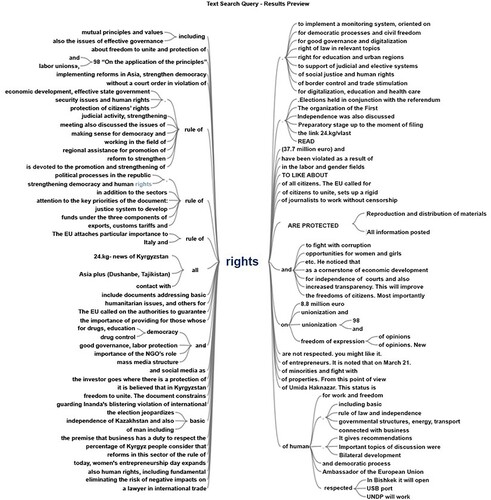

and Figure B6 (Appendix B) collectively illuminate the coding results, revealing the prevalence of human rights codes as the foremost components associated with the EU's endeavours to foster democracy in Central Asia. This insight is derived from a meticulous examination of content extracted from the Central Asian news sources. The cumulative count of human rights codes reaches 259, aligning seamlessly with the outcomes obtained from the word-level scrutiny (), where the term ‘rights’ occupies a significant position.

Table 5. Amount of codes’ references in the Central Asian media outlets that mention EU-Central Asia relations.

The spectrum of human rights codes encompasses a diverse array of dimensions, including social, minority, political, labour, gender, economic, cultural, and civil rights. Among these, social rights find expression 58 times within the scrutinized texts. The explicit term ‘human rights’ itself is explicitly mentioned 64 times across the surveyed news outlets. In contrast, labour rights and minority rights receive the least frequent mentions among the enumerated categories.

The investigation also brings to light substantial references to the domains of good governance (with 58 references) and civil society (with 53 references) (). Conversely, the concepts of the rule of law (with 42 references) and democracy itself (with 21 references) emerge with the least frequency of mention within the ambit of the EU's initiatives to promote democracy in Central Asia ().

The perception is particularly emphasized through the lenses of border control, development, and education assistance. The EU's stance on human rights matters in Central Asia, with a specific focus on social and gender rights (as depicted in Figure B6), stands out prominently. These dimensions are accentuated and underscored through the lens of local media coverage, underscoring their understanding of the EU's focal points and undertakings within the region.

A deduction can be drawn from these findings, suggesting that regional news sources perceive the EU's efforts to bolster democracy as intricately tied to European influence, arguably implying that the EU democracy promotion is part of a broader geopolitical strategy. This finding corroborates the assertions of Sharshevova (Citation2018), Fawn (Citation2022), and Arynov (Citation2022a) that the EU's activities in the region are driven and perceived by its interests.

Conclusion

In this article, we argue that the EU democracy promotion efforts in Central Asia are primarily perceived through the framework of human rights, while comprehension of other facets of the EU democracy promotion agenda remains intricate. Our findings demonstrate an alignment between both self- and external perceptions concerning the EU human rights promotion in the region.

This study successfully achieves its primary goal of examining the alignment or misalignment between the EU's self-perception and external perception, based on a content analysis of the EU legal framework and Central Asian media. Our findings address the research question and indicate that human rights are the only area of alignment reflected in the media of Central Asian states. Despite this alignment, there is a difference in focus: EU documents cover a broader spectrum of rights, whereas media analysis emphasizes social and gender rights more prominently.

Consequently, the EU normative agenda continues to face misinterpretation outside the EU (Larsen Citation2014) including Central Asia. Furthermore, we align with scholars such as Bossuyt and Kubicek (Citation2011) and Wetzel, Orbie, and Bossuyt (Citation2015) in advocating for a reassessment of the EU normative agenda for Central Asia to achieve greater comprehension and alignment with local perceptions. Arguably, the EU might need to enhance its communication strategies by highlighting the interconnectedness of human rights with other democratic principles, such as support for civil society, good governance and the rule of law, to foster a more comprehensive understanding of its efforts.

Future research could delve deeper into understanding the specific factors contributing to the comprehension gap between Central Asia and the EU democracy promotion agenda, particularly in areas beyond human rights. Addressing these gaps and emphasizing a comprehensive democracy-based approach could enhance the EU's impact on democracy promotion in the region. Such kind of empirical research could provide evidence-based recommendations for policymakers aiming to enhance the effectiveness of EU democracy promotion efforts in the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ariely, G., and H. Zahavi. 2023. Evaluating the Impact of the EU’s Normative Message of the ‘EU as a Model’ on External Public Perceptions: An Experimental Study in Israel, European Security. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2023.2225163.

- Ariely, G., H. Zahavi, and T. Hasdai-Rippa. 2023. “National Identity as a Cultural Filter: External Perceptions of the EU in Israel.” Journal of European Integration 45 (6): 945–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2023.2212851.

- Arynov, Z. 2022a. “Opportunity and Threat Perceptions of the EU in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 734–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2021.1917516.

- Arynov, Z. 2022b. “Hardly Visible, Highly Admired? Youth Perceptions of the EU in Kazakhstan.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 13 (1): 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/18793665211058187.

- Axyonova, V. 2012. “EU Human Rights and Democratisation Assistance to Central Asia: In Need of Further Reform.”.

- Axyonova, V. 2014. “The European Union's Democratization Policy for Central Asia: Failed in Success Or Succeeded in Failure?”. Vol. 11. Columbia University Press.

- Axyonova, V., and F. Bossuyt. 2016. “Mapping the Substance of the EU's Civil Society Support in Central Asia: From neo-Liberal to State-led Civil Society.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 49 (3): 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2016.06.005.

- Aydin-düzgit, S. 2018. “Legitimizing Europe in Contested Settings: Europe as a Normative Power in Turkey?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 612–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12647.

- Bekenova, K., and N. Collins. 2019. “Knowing me, Knowing you: Media Portrayal of the EU in Kazakhstan.” Europe-Asia Studies 71 (7): 1183–1204.

- Bengtsson, R., and O. Elgström. 2012. “Conflicting Role Conceptions? The European Union in Global Politics.” Foreign Policy Analysis 8 (1): 93–108.

- Blood, D. J., and P. C. B. Phillips. 1995. “Recession Headline News, Consumer Sentiment, the State of the Economy and Presidential Popularity: A Time Series Analysis 1989–1993.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 7 (1): 2–22.

- Börzel, T. A. 2022. "EU Democracy Projection: Does the EU Practice What It Preaches?." Mediterranean Politics 27 (4): 553-562.

- Bossuyt, F., and N. Davletova. 2022. “Communal Self-Governance as an Alternative to Neoliberal Governance: Proposing a Post-Development Approach to EU Resilience-Building in Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 788–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2022.2058913.

- Bossuyt, F., and P. Kubicek. 2011. “Advancing Democracy on Difficult Terrain: EU Democracy Promotion in Central Asia.” European Foreign Affairs Review 16 (5): 639–658.

- Brewer, P. R. 2006. “National Interest Frames and Public Opinion About World Affairs.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 11 (4): 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X06293725.

- Chaban, N., O. Elgström, S. Kelly, and L. S. Yi. 2013. "Images of the EU Beyond its Borders: Issue-Specific and Regional Perceptions of European Union Power and Leadership." JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (3): 433-451.

- Chaban, N., O. Elgstrom, and M. Holland. 2006. “The European Union as Others see it.” European Foreign Affairs Review 11: 245–262.

- Chaban, N., and M. Holland. 2019. “Introduction. Partners and Perceptions.” In Shaping the EU Global Strategy. The European Union in International Affairs, edited by N. Chaban and M. Holland. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92840-1_1

- Costa Buranelli, F. 2021. “Central Asian Regionalism or Central Asian Order? Some Reflections.” Central Asian Affairs 8 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.30965/22142290-bja10015.

- Crawford, G. 2000. “Promoting Democratic Governance in the South.” European Journal of Development Research 12 (1): 23–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810008426751.

- Dahl, R. 1989. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Diamond, L. 2022. "Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective: Scope, Methods, and Causes." In Democratic Regressions in Asia, 22-42. Routledge.

- EEAS Factsheet. 2020. BRYCA project URL:https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/foe_bryca_eidhr_12.6.2020.pdf.

- EEAS Factsheet on the EU- Central Asia relations. 2022. URL:https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EU-Central%20Asia%20relations%20factsheet.pdf.

- EEAS. The EU Rule of Law Program for Central Asia. 2020. URL:https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/central-asia-rule-law-programme_en.

- Elgstrom, O. 2010. “Partnership in Peril? Images and Strategies in EU–ACP Economic Partnership Agreement Negotiations.” In External Perceptions of the European Union as a Global Actor, edited by S. Lucarelli, 137–146. London: Routledge.

- Elgstrom, O., and N. Chaban. 2015. “Studying External Perceptions of the EU: Conceptual and Methodological Approaches.” In Perceptions of the EU in Eastern Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by B. Muller, 17–33. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137405470_2.

- European Commission. 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/what/human-rights/documents/mip_eidhr_2011-2013_for_publication2_en.pdf.

- EU and Kazakhstan. 2015. Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between the EU and Kazakhstan. 2015. Available at: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22016A0204(01)

- European Union Global Strategy. 2016. “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe”. URL:https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf.

- European Union Strategy for Central Asia. 2019. “The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership.” May 15. URL:https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019JC0009&from=EN.

- Fawn, R. 2022. "‘Not Here for Geopolitical Interests or Games’: The EU’s 2019 Strategy and the Regional and Inter-Regional Competition for Central Asia." Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 675–698.

- Fioramonti, L., and S. Lucarelli. 2009. "Self-Representations and External Perceptions–Can the EU Bridge the Gap?. External Perceptions of the European Union as a Global Actor 7: 218–256.

- Gilens, M. 1999. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race. Media, and the Politics of. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hoffmann, K. 2010. “The EU in Central Asia: Successful Good Governance Promotion?” Third World Quarterly 31 (1): 87–103.

- Holland, M., N. Chaban, J. Bain, K. Stats, and P. Sutthisripok. 2005. “EU in the Views of Asia-Pacific Elites: Australia, New Zealand and Thailand.” NCRE Research Series No. 5, December 2005, pp. 1–23.

- Holsti, K. J. 1970. “National Role Conceptions in the Study of Foreign Policy.” International Studies Quarterly 14 (3): 233–309. https://doi.org/10.2307/3013584.

- Hönig, A.-L., and S. Tumenbaeva. 2022. “Democratic Decline in the EU and Its Effect on Democracy Promotion in Central Asia.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 35 (4): 424–458.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Ibrayeva, G., et al. 2019. “Consumption of News Content on the Internet in Central Asia.” Institute for War and Peace Reporting Central Asia. https://doi.org/10.46950/201902.

- Isaacs, R. 2009. “The EU’s Rule of Law Initiative in Central Asia.” EUCAM Policy Brief 9: 1–6.

- Iyengar, S., and D. R. Kinder. 1987. “News That Matters. Chicago: Univ”.

- Keijzer, N., and F. Bossuyt. 2020. “Partnership on Paper, Pragmatism on the Ground: The European Union’s Engagement with Civil Society Organisations.” Development in Practice 30 (6): 784–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1801589.

- Kellstedt, P. M. 2003. The Mass Media and the Dynamics of American Racial Attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Knack, S. 2004. “Does Foreign Aid Promote Democracy?” International Studies Quarterly 48 (1): 251–266.

- Korosteleva, E., and F. Bossuyt. 2019. “The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities or ‘The Same Old Song’?.” LSE IDEAS Dahrendorf forum Debating Europe. Dahrendorf Forum. URL: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/74465/1/EU-CA%20strategy%20piece_final.pdf.

- Kurki, M. 2010. “Democracy and Conceptual Contestability: Reconsidering Conceptions of Democracy in Democracy Promotion .” International Studies Review 12 (3): 362–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2010.00943.x.

- Larsen, H. 2014. “The EU as a Normative Power and the Research on External Perceptions: The Missing Link.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (4): 896–910.

- Lucarelli, S. 2007. “The European Union in the Eyes of Others: Towards Filling a Gap in the Literature.” European Foreign Affairs Review 12 (3): 249–270. https://doi.org/10.54648/eerr2007025.

- Lucarelli, S. 2014. “Seen from the Outside: The State of the Art on the External Image of the EU.” Journal of European Integration 36 (1): 1–16.

- Lucarelli, S., and L. Fioramonti. 2009. External Perceptions of the European Union as a Global Actor. New York: Routledge.

- Manners, I. 2002. “Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms?” Journal of Common Market Studies 40: 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00353.

- Mutz, D. C. 1994. “Contextualizing Personal Experience: The Role of Mass Media.” Journal of Politics 56 (3): 689–714.

- Nelson, T. E., R. A. Clawson, and Z. M. Oxley. 1997. “Media Framing of a Civil Liberties Conflict and its Effect on Tolerance.” American Political Science Review 91 (3): 567–583.

- Olivier, G., and L. Fioramonti. 2010. “The Emerging “Global South”: The EU in the Eyes of India, Brazil and South Africa.” In External Perceptions of the European Union as an International Actor, edited by S. Lucarelli, 105–119. New York: Routledge.

- Ospanova, B., H. A. Sadri, and R. Yelmurzayeva. 2017. “Assessing EU Perception in Kazakhstan’s Mass Media.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 8 (1): 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2016.08.002.

- Pardo, S. 2015. Normative Power Europe Meets Israel: Perceptions and Realities. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Pierobon, C. 2022. “European Union, Civil Society and Local Ownership in Kyrgyzstan: Analysing Patterns of Adaptation, Reinterpretation and Contestation in the Prevention of Violent Extremism (PVE).” Central Asian Survey 41 (4): 752–769.

- Powlick, P. J. 1995. “The Sources of Public Opinion for American Foreign Policy Officials.” International Studies Quarterly 39 (4): 427–451. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600801.

- Ribeiro, F. N., et al. 2018. “Media Bias Monitor: Quantifying Biases of Social Media News Outlets at Large-Scale.” Paper presented at the Twelfth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social media. URL:https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM18/paper/view/17878/17020.

- Russell, M. 2019. Connectivity in Central Asia: Reconnecting the Silk Road. Belgium, Brussels: EPRS: European Parliamentary Research Service. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1335092/connectivity-in-central-asia/1941326/.

- Rustow, D. 1970. “Transition to Democracy: Towards a Dynamic Model.” Comparative Politics 2 (3): 337–363.

- Scheipers, S., and D. Sicurelli. 2007. “Normative Power Europe: A Credible Utopia?” Journal of Common Market Studies 45 (2): 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00717.x.

- Sharshenova, A. 2018. The European Union’s Democracy Promotion in Central Asia. Ibidem: Stuttgart.

- Sicurelli, D. 2015. “‘The EU as a Promoter of Human Rights in Bilateral Trade Agreements: The Case of the Negotiations with Vietnam’.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 11 (2): 230–245.

- Soroka, S. N. 2006. “Good News and bad News: Asymmetric Responses to Economic Information.” The Journal of Politics 68 (2): 372–385.

- Soroka, S. N., D. A. Stecula, and C. Wlezien. 2015. “It's (Change in) the (Future) Economy, Stupid: Economic Indicators, the Media, and Public Opinion.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 457–474.

- Spaiser, O. A. 2018. The European Union’s Influence in Central Asia: Geopolitical Challenges and Responses. Lexington: Books.

- The EU Strategy for Central Asia. 2019. “The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019JC0009

- Treaty of Lisbon. 2007. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2007:306:FULL:EN:PDF

- Treaty of Maastricht. 1992. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:JOC_1992_224_R_0001_01

- Valkenburg, P. M., H. A. Semetko, and C. H. De Vreese. 1999. “The Effects of News Frames on Readers’ Thoughts and Recall.” Communication Research 26 (5): 550–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365099026005002.

- Warkotsch, A. 2008. “Normative Suasion and Political Change in Central Asia.” Caucasian Review on International Affairs 2 (4): 62–71. http://cria-online.org/Journal/5/NORMATIVE%20SUASION.pdf.

- Wattenberg, M., and F. B. Viegas. 2008. “The Word Tree, an Interactive Visual Concordance.” IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 14 (6): 1221–1228.

- Wetzel, A., J. Orbie, and F. Bossuyt. 2015. “One of What Kind? Comparative Perspectives on the Substance of EU Democracy Promotion.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28 (1): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2015.1019726.

- Youngs, R. 2010. The EU's Role in World Politics: A Retreat from Liberal Internationalism. London: Routledge.