ABSTRACT

Despite the increasing digitalisation of special collections, Australian university libraries continue to house tangible original works contributing to collective state, national and global heritage. The protection of special collections relates to the international aspirations provided by the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 Priority 3. Currently over five hundred separately grouped university library special collections are recorded in Australia. Globally, there is limited research into university librarian comprehension of how to plan for the protection of special collections. A survey targeted the 35 Australian university libraries identified for inclusion in the study, via the Council for Australian University Librarians (CAUL) database. Eleven (31%) responses qualified for analysis. Of the respondents, the findings include 92% hold tangible special collections as part of their university library collection; 90% do not have a specific plan for the protection of special collections and 90% have experienced a disaster event at some point in their library career. The research concludes that special collections held by Australian universities are at risk and that the role of the university librarian is undervalued in the global efforts to protect cultural and historical heritage in the event of a disaster.

Introduction

Australian university libraries, meaning libraries attached to a higher education institution, supporting students, curriculum and research faculties, are typically managed by a University Librarian or Director. While traditionally university libraries are perceived to be concerned with hard copy books and journals, many are at the forefront of technical innovations and end user developments. However, despite the increasing digitalisation of collections, university libraries continue to hold tangible original works within their collections, providing a rich source of research material for scholars. The notion of university libraries acting as ‘repositories of cultural heritage’ was highlighted by Bansal (Citation2015, p. 10), while Ugwuanyi, Ugwu & Ezema (Citation2015, p. 2) posed the question ‘is the ability to safeguard and preserve their collections…uppermost in their policies?’ This informed the research question: Do university libraries in Australia actively plan to protect special collections from disaster?

Special collections consist of material preserved for future generations and are often very old, rare, unique or fragile, and hold historical, cultural or significant research value (Cullingford, Citation2016, pp. 25–47). Special collections are often a result of an individual’s collection reflecting their personal interests, subsequently donated to the University. Special collections are predominantly managed and located separately from mainstream collections, to ensure future preservation requirements, such as monitored environmental controls of temperature, humidity and light levels, and with access subject to strict rules and regulations.

Australian university libraries hold numerous historical and culturally valuable items making an invaluable contribution to collective state, national and global heritage. In Australia, university libraries have in excess of 500 separately grouped special collections with each collection holding numerous items. However, an exact figure is hard to determine as the public database held by the Council of University Librarians (CAUL) listing special collections in university libraries has not been updated since 2014 (Cass, Citation2014). Examples of special collections include the Monash University Library Rare Books Collection; University of Melbourne European music, first editions and music manuscripts collection and James Cook University which houses the Eddie Koiki Mabo Library collection.

This research employs the term ‘disaster’ as this word is commonly understood in the wider community. The planning for and management of a disaster is called emergency management. Occurring over a short time frame, a disaster is often referred to as a ‘serious disruption of the functioning of a community which involves widespread human, material, economic or environmental loss and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources’ (Terminology – UNISDR, Citation2017). In academia, disasters are viewed as a consequence of inappropriately managed risk – a product of hazards and vulnerability (Quarantelli, Citation1998).

According to Alegbeleye (Citation1993), disaster occurs in a library when any event causes a sudden removal of records and documents from accessibility and use. Research on the planning and management of disasters in libraries has focussed on case studies involving first hand experiences (Corrigan, Citation2008; Grant, Citation2000; Maylone, Citation1980; Newman & Harris, Citation2015; Saunders, Citation1993); practical advice on developing an emergency management plan (Allain & Vallas, Citation2014; IFLA, Citation2006; Yasue, Citation2012) or how to recover and restore items such as sodden books smoke affected journals or damaged special collection items which need specific expertise for handling (Cullingford, Citation2016, pp. 25–47).

Literature Review

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) includes categories of heritage that is immoveable such as historic sites or monuments; and moveable, such as books, films, artwork and artefacts (UNESCO, Citation2016). It can also be tangible, such as buildings, sites and artefacts and intangible such as folklore, language and customs (Graham & Spennerman, Citation2006; Newman & Harris, Citation2015). However, the focus globally and within Australia has been primarily with the protection of immoveable, tangible heritage rather than moveable, tangible heritage such as books.

The infamous Florence Flood in 1966 is recognised as a major turning point in cultural preservation for tangible, moveable heritage. Creating approximately 600,000 tons of mud, rubble and sewage, affecting Florence, Italy, the flood destroyed and damaged numerous collections of books, invaluable manuscripts and fine art. The National Central Library of Florence was cut off and over 1,300,000 items, a third of the holdings, were damaged (Devine, Citation2005). The event led to numerous guidelines for mass-treatment advice for stabilising wet and damaged materials over the next 20 years (Tandon, Citation2013). It is often cited as the turning point in emergency management planning and recovery for libraries as ‘within the field of preservation…it generated new thinking, collaborative approaches and a wealth of innovative advances that continue to be used and adapted worldwide’ (Scott & Wellheiser, Citation2003, p. 114–115; McCracken, Citation1995, p. 2).

Other examples of university library disasters include quick onset mould growth at the University of Iowa Law Library in 2002, which destroyed numerous rare books (Kraft, Citation2006). The University of Tulane library had losses totalling over $30 million as a result of Hurricane Katrina, and the experiences are well documented by Corrigan (Citation2008). Earthquakes affecting library collections have been reported as case studies by the Imperial University Library (1923); California State University library (1994); Stamford University (1981) and the University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (2005). The 2004 tsunami destroyed the Madras University Library and the Aceh Documentation and Information Centre, known for its collection of rare books and manuscripts (Revolvy, Citation2018).

Civil unrest and war have also affected university libraries. The burning of the Library of Alexandria, often marked as the first Library of the World, is a famous historical example, and in WWII, numerous libraries were lost including over 200,000 books alone in the National University of Tsing Hua in Peking (Van der Hoeven & van Albada, Citation1996). The Central University library in Bucharest (1989) was destroyed during the Romanian Revolution. The University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina was destroyed during the siege of Sarajevo (Tomljanovich & Zećo, Citation1996). Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) destroyed 8,000 books and 10,000 manuscripts when they looted and ransacked the library at the University of Mosul in 2014 (Jadallah, Citation2017; MacDiarmid, Citation2017). Fire has also impacted on university libraries such as in 2015 fire at the Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences in Moscow (The Guardian, Citation2015); the fire in the Dalhousie University Law Library (1985) in Canada and in the University of Edinburgh Artificial Intelligence Library (2002). Libraries can also be affected by public disorder or protests. Universities can face protesters, especially if involved in controversial issues, where they may find themselves unwillingly involved, as demonstrated in 2016 when students at University of Sydney protested against the Federal Education Minister speaking at the Fisher library and riot police were called in (Burke, Citation2016). Threats to libraries include theft, as illustrated in the 1980s in USA when James Shinn stole over $1 million worth of books from university libraries (Falciani, Citation2017), followed by Stephen Blumberg in the 1990s, whose haul of rare books totalled over $5 million (Basbanes, Citation1999).

The Cooperative Action by Victorian Academic Libraries (CAVAL) 2003 survey on disaster response included incidents cited by Australian university libraries over a 6 year period (1997–2003). Examples included a fire hose which burst, affecting the Rare Book room; power failure across multiple sites caused by a bushfire; the loss of a complete library in a bushfire; a sewage spill; a small fire and flooding caused by workmen which disrupted services, and multiple examples of storm damage caused by hail, resulting in a university having to close libraries for a period of time and limiting services. In South Australia, the Barr Smith Library at the University of Adelaide suffered a major flood in March 2005 when construction works damaged a watermain on North Terrace Campus inundating the library and campus buildings with over 200,000 l of water and 40 t of mud. It damaged the IT server room and almost closed the University for three days with a strong possibility of closing the University for a semester, with projected losses of $90 million in lost revenue (Beaumont, Citation2008). In early 2018, a severe storm caused half a meter flooding to the library at Australian National University in Canberra, damaging electrical distribution boards, air conditioning and ventilation systems and IT infrastructure, in addition to damaging microfilm collections, books, serials and journals (Baker, Citation2018) and recently the Law Library at the University of Tasmania was damaged following a severe storm (Blackwood, Citation2018). McCracken (Citation1995) comments each library disaster that occurs serves to remind of the importance of planning and when items ‘within a rare book collection …are lost, the institution has failed in a significant portion of its primary goal’ (McCracken, Citation1995, p. 3). The failure to plan for disasters is ‘a failure of the library to protect collections’ (Cuthbert & Doig, Citation1994, p. 17).

In Australia there have been attempts to assist Australian university libraries with emergency management planning by CAVAL who produced a ‘Disaster Response Plan’ (CAVAL Risk Management Group, Citation2005). The Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) has produced the manuals ‘ALIA Guide to Disaster Planning, Response and Recovery’ (Australian Library and Information Association, Citation2010) and ‘ALIA Disaster Planning for Libraries’ (ALIA, Citation2010).

Given the case studies of disasters affecting university libraries, there has been few research studies conducted globally with specific focus on university librarian knowledge for library disaster management. Echezona, Ugwu, and Ozioko (Citation2012) conducted research in South East Nigeria in which 51.2% of university librarians surveyed had low levels of disaster management knowledge, with 48.8% stating that any knowledge came from academic literature. A study conducted in North-East Nigeria surveyed 21 university library leaders, with 71.4% not sensitised to disaster preparedness (Maina Abareh, Citation2014). In Europe a study by Kostagiolas, Araka, Theodovou & Bokos (Citation2011) found, through their survey of 22 Greek university libraries, that 90% had no disaster management plan. Pierard et al. refer in the 2016 paper, to a survey conducted in 1992 by Amigos Library Services in which 75% of university library respondents had no disaster plan and also quote the 2004 Heritage Health Index findings in which 66%–80% of libraries responding to their survey had no emergency plan (Pierard et al., Citation2016, p. 309).

Only two Australian surveys were located which deal specifically with emergency management planning in university libraries. The first was conducted in 1996 by CAUL and sought information regarding university library involvement in regional disaster planning (Council of Australian University Librarians, Citation1996). The second survey was conducted by CAVAL in 2003 and focused on response plans from 16 Australian university libraries (CAVAL, Citation2003).

There are a number of common barriers suggested by Cuthbert & Doig (Citation1994, p. 13) regarding why university libraries and library senior management conduct limited investment in emergency management planning. Primary reasons cited include time or budget constraints; the belief that insurance cover would pay out on historical or valuable items; that statistically a disaster is unlikely to happen or they believed they did not hold historical items of significance. These barriers are also reflected in the findings of this study.

Building capacity to respond to disasters within a library, Graham and Spennemann (Citation2006) comment that ‘if cultural heritage is fortunate enough to survive the physical impact of the disaster itself – will it survive the decisions made during or after the disaster? The effects of ill-considered management action can be devastating’. This highlights the vital role university librarians have. Leadership within the context of disasters has often been discussed as ‘technical’ or ‘adaptive’ (Heifetz, Linsky, & Grashow, Citation2009). Technical challenges require leaders with specific expertise, but adaptive challenges require creative solutions to evolving situations. Adaptive leadership is defined by implementing change that ‘enables the capacity to thrive in crisis environments’ (Hayashi & Soo, Citation2012, p. 80). Educational institutions, according to Hannah, Uhl- Bien, Avolio & Cavarretta (Citation2009, p. 901) are examples of ‘naïve organisations’ as they ‘see low probability of such events occurring; they are less likely to apply resources to prepare for such events’. This view was also reflected in our research findings.

Various librarian researchers (Hernon, Giesecke, & Alire, Citation2008; Hernon & Rossiter, Citation2006; Kreitz, Citation2009; Wilkinson, Citation2015) have conducted studies on the relationship between emotional intelligence and library leaders, and the personal attributes of university library emergency management response teams. Wilkinson (Citation2015) found a strong relationship between the two, and this may inform university librarians who to train and appoint to emergency management teams. They found that leadership during disasters was carried out through teamwork and initiative and manifested through quick decisions. Parker (Citation2012) notes the significance of motivation and trust library management provided before the 1997 flooding at Morgan Library, Colorado State University, noting employees stated their ability to innovate and adapt during the disaster was the result of a pre-event environment where experimentation and trial and error were welcomed by library management.

Matthews and Eden (Citation1996) discovered that many librarians did not know the value of their collections. The question of insurance for items which are deemed irreplaceable, is evident in the limited literature related to insurance of special collections (Cady, Citation1999). However, in the majority of cases, collections do survive, unless destroyed by fire or theft, so can be treated and restored, which costs (Cady, Citation1999; Cullingford, Citation2016; Kostagiolas et al., Citation2011). In addition, making contact and alliances with key suppliers, qualified moisture control vendors and salvage companies (such as the international company BELFOR or Australian based Steamatic) can save time during the response and recovery phase. Contracts can be established in advance for emergency services and can save days of negotiations that a wet library collection does not have to spare (Corrigan, Citation2008; Lengfellner, Citation2011; Raman & Zach, Citation2010).

Emergency management plan templates can be sourced by a simple web search; however, few are university library relevant or can be adapted for special collections. A notable exception is the University of Edinburgh (University of Edinburgh, Citation2013) which developed an emergency plan template for special collections and d-Plan which is a free online line generator for library emergency management plans (d-Plan, Citation2006).

Method

This research is the first known into emergency management knowledge held by university librarians in Australia for special collections. The aim was to investigate knowledge held by Australian university librarians in relation to emergency management, specifically in relation to protecting items of historical or cultural interest held in special collections. The research study did not include emergency management for museums, art galleries or physical sites of historical importance connected to universities. It did not include special collections held by Australian universities at overseas campuses or discuss personal or private libraries held by academics or university archives.

Data for this study was collected during the period of 01 June to 31 August 2017. Using a purposeful sampling strategy (Palinkas et al., Citation2013), 39 university librarians were identified and selected for participation. Four were excluded as their university did not hold special collections, they were involved in an advisory capacity in this study or there was no university librarian in position at that time. Ethics approval was provided by Charles Sturt University.

The data collecting instrument adopted for this study was an online survey requiring participants to provide basic information about their professional background, information about held special collections, previous experience of disasters and lessons identified, emergency management plans and who developed plans, training for staff, insurance and salvage provisions and factors influencing or preventing the development of plans. The final section was an open-ended comment box.

Thirty-five surveys were dispatched. Following a review of submissions, 11 responses were accepted giving a return rate of 31%. The data is presented in percentages.

Results

The response rate of 31% represents approximately a third of the university librarians approached, providing a relevant baseline of current preparedness and knowledge levels within Australia.

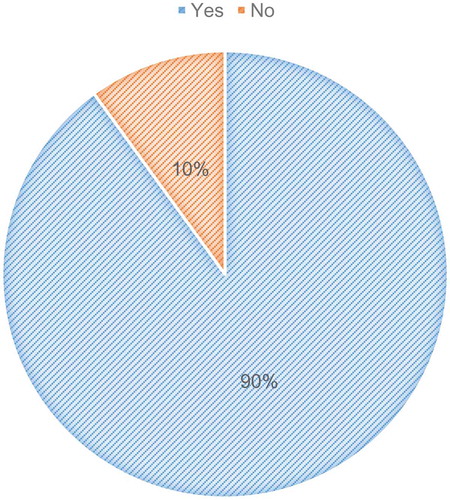

All respondents held the position of university librarian (UL) or equivalent. Three per cent had been UL for less than 2 years; 17% had been UL for between 2 and 5 years; 33% had been UL for between 6 and 10 years and 17% had been UL for more than 11 years. All held tangible special collections within their university library. Twenty-seven per cent did not house special collections in a purpose built or separate facility (either off site or in house) while 73% did. Ninety per cent had experienced a disaster at some stage during the course of their library career (See ).

From the 90% of respondents who had experienced a disaster, a number of lessons were drawn from their collective experiences. The lessons noted included recovery took more time, staff and space than anticipated, and keeping emergency management plans and associated staff responsibilities delineated and updated regularly.

There was agreement between respondents that dissemination of plans and procedures to staff should be regular and that a risk register is an essential element of any plan, while also accepting that the library will have limited control over the building environment. Disaster bins are normally domestic wheelie bins containing items useful in the immediate response such as plastic sheeting, gloves, cloths, water soaking pads and buckets. Libraries with filled disaster bins and whose staff had received relevant training in basic emergency collection preservation management techniques stated the bin was useful for aiding immediate response to unfolding disasters. Also of note were comments indicating the need for a business continuity plan, ensuring key services continued with minimal disruption and pre-disaster sourcing of temporary storage options for collections, alongside professional conservation and salvage advice provided pre-disaster to assist during the recovery phase.

Fifty-five per cent noted their current library had experienced a disaster. Flooding was the main cause cited, with both minor and major disruption caused by natural and man-made hazards such as storms or burst pipes.

Sixty-three per cent had an emergency management plan for general library collections with 29% stating the emergency management plan is included within the overall institutional (or university wide) emergency plan; 71% had a stand alone plan specific to the main library collection.

Of the 63% who had an emergency management plan specific to the main library collection, 14.5% stated the emergency management plan was generated by a junior staff member, 71% said it was created by an internal group from within the University and 14.5% said it was created by internal and external consultants. Of the 63% with a plan, 29% said the plan was updated bi-annually and 71% said the plan was updated yearly.

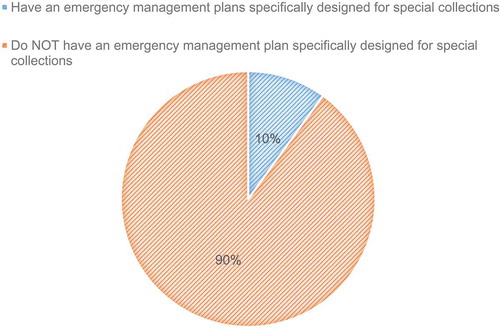

Of note to this research, 90% of respondents do not have specific emergency management plan for special collections (See ). One respondent, however, did note that their library was considering developing an emergency management plan for special collections.

Having access to a template for an emergency management plan was a key influence for those who had one for the main library collection. Previous training in disaster management gave valuable background knowledge to librarians when responding to incidents. In instances of a plan being created for the main library collection, respondents stated that senior university management were supportive of a plan, primarily based on previous disaster experiences. Respondents noted that of little influence in their development of a plan was any existing university-wide policy requirement to have one.

In university libraries containing emergency management plans for special collections, it was predominately the special collections librarian who had driven the construction of a plan. Thus, the allocation of a particular staff member was a key influence and driver in plan completion. One respondent noted the requirement of the insurance company to have an emergency management plan for special collections, as part of the insurance coverage. Of less influence was the support or requirement from senior university management for related university-wide emergency management policies.

The factors preventing the development of an emergency management plan for a main library collection included (highest ranking influence to lowest) having limited staff and resources; time or budget implications and limited knowledge about how to construct a plan; the requirement to plan was not driven by senior university management; being unable to source a plan that was suitable for their needs and the feeling that the chances of a disaster occurring were so small it was not worth the effort.

The influences which prevented the development of an emergency management plan for special collections included (highest ranking influence to lowest) having limited staff and resources, time or budget implications and limited knowledge about constructing a plan. They were also unable to source a plan that was suitable for their needs and many felt the chances of a disaster occurring were so small it was not worth the effort. In addition, the requirement was not driven by senior university management.

Thirty-seven per cent rated having an emergency management plan for main library collections as highly important; 45% rated it fairly important and 18% rated it important. Having an emergency management plan for special collections was rated as more important, with 45% rating it of high importance and 18% said it was very important; 9% fairly important; 9% important; 9% not that important and 9% unrated.

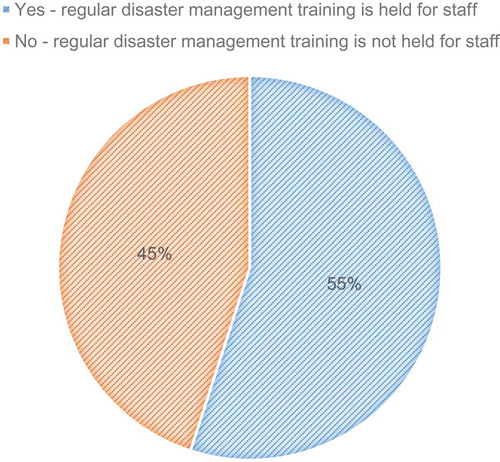

Forty-five per cent do not hold regular disaster management training, see .

Figure 1. Response to the question ‘Have you directly experienced a library disaster (this includes minor floods, fires, insect damage, and major natural event) either with a library collection or special collection at ANY time during your career?’.

Figure 2. Response to the question ‘Do you have an emergency management plan for Special Collections?’.

Figure 3. Response to the question ‘Do you hold regular emergency/disaster training for your staff (excluding fire drills)?’.

Reasons given for not holding training include the low priority of training in disasters within the university, limited time and budget, lack of priority, the risk of a disaster was too low or that they were planning to conduct training in the future. Ninety per cent of UL would be willing to commit funds and resources for training in special collections disaster management depending on cost, with 10% willing to commit in principle.

Seventy-three per cent stated special collection insurance is part of institutional insurance coverage with 18% stating special collections had independent insurance coverage. Nine per cent gave no response to this question. None of the respondents subscribe to a commercial disaster recovery company.

Discussion and Research Implications

In this section, we discuss a number of implications drawn from both the research and literature, in an endeavour to inform the planning and preservation for special collections in Australian university libraries.

Recording Lessons Learned

Within the Australian context, there are a number of opportunities in connection to special collections and disasters that could be explored. The research highlights that a barrier to producing an emergency plan is the belief that the occurrence of a disaster was highly unlikely. The literature has shown that university libraries are frequently affected by disasters, perhaps more than realised by university librarians. Although participants in our research felt the risk of disaster was low, 90% indicated they had experienced a disaster in a library at some point during their career. This is a disconcerting finding, as at face value it appears to indicate that lessons are not being learned as a result of prior experience.

As Fullerton (Citation2004) notes in her comments on the 1985 fire at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, key lessons to share included a lack of preparedness by the library to deal with a disaster; the importance of external emergency services having detailed knowledge of the building and which areas contained sensitive materials; back-up and crossovers in roles and knowledge without depending on particular individuals and a lack of planning for media, spectators or spontaneous volunteers. Recovery from this incident of a few hours took more than a year and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, yet it was ‘a minor incident, hardly noticeable on the scale of major library disasters over the years’ Fullerton (Citation2004, p. 178).

Roberts (Citation2015) describes how an earthquake affected the delivery of services at the University of Canterbury, which was closed for three weeks following an earthquake in 2012. When the University re-opened 3 weeks later, large tents were established in the carpark for lecture rooms, and a limited library service based on a live chat reference service and reliance on electronic resources, were managed. Library management need to consider how they might deliver critical services if these systems, processes or facilities are not available. The most critical work for the University of Canterbury concerned the essential systems and processes. The library team created a vulnerability matrix for core services, allowing them to identify preparedness measures that would have the greatest impact for core services.

At the University of Auckland, Grant (Citation2000) describes how, during a major power outage, building security was the major issue as staff discovered that the emergency door locks in the library worked on battery power which lasted only 14 h, at which point the doors simply drifted open. Since then the library has installed simple door bolts. Grant notes the Disaster Preparedness Plan was updated regularly, but heavily focussed on damage to the collection rather than a continuity of services. Case studies such as these provide a wealth of first-hand experience and a central point for knowledge sharing that could inform the pre-disaster planning of university librarians.

The Australia database listing special collections held by university libraries has not been updated since 2014 and to the authors’ knowledge no database of disasters experienced by university libraries, both in Australia and globally is available. The combination of both data sets would be particularly useful in assessing the risks and possible resilience building measures that could investigated for the future.

Collaboration

Investigations regarding a network of special collections libraries, perhaps utilising the new ALIA Rare Books and Special Collections network, can be established as a first step in improving communication and knowledge exchange within the field. Longer term cooperative bi-lateral and multi-lateral agreements with a range of cultural institutions at state level is an example of best practice that could be considered (Gorman, Citation2007; Newman & Harris, Citation2015). Structures or agreements can pool resources when required, and harness expertise. For example, Arts Victoria established a protocol after 2012 bushfires for responding to disasters that impact on cultural heritage (AICCM, Citationn.d.) and the DisACT network in Canberra (Anbg.gov.au, Citation2010) is another example.

Librarians should also be aware of how their actions are feeding into the global efforts of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, to protect items of cultural importance, specifically via Priority 3 which states ‘investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience via public and private investment, is a cost-effective mechanism to enhance the economic, social, health and cultural resilience of persons’. (United Nations, Citation2015, pp. 18–20).

Template Development

Despite relevant developments in relation to emergency management planning and recovery the reality is many libraries, despite good intentions, have yet to ‘realise those intentions in the form of a plan or through integrated planning’ (Scott & Wellheiser, Citation2003, p. 4). Although the University of Edinburgh (University of Edinburgh, Citation2013) has a free online emergency plan template it is not Australian university library specific and the research results demonstrate that the lack of a suitable template was a prohibitive factor in producing an emergency plan, either for main or special library collections. The development of an appropriate emergency management template, created in collaboration with relevant partners, requires serious consideration.

Role of Librarians

The concept of ‘Build Back Better’ was developed from the recovery efforts following the Indian Ocean Tsunami in 2004 (Mannakkara & Wilkinson, Citation2014). Pierard et al. (Citation2016) recommend a planning framework for libraries that moves beyond immediate emergency response and towards a longer-term goal of strategic resilience. The context of Building Back Better Libraries (BBBL) is library spaces and facilities, library collections, library services and the implementation and monitoring role of a library disaster team.

Kostagiolas et al. (Citation2011) state that there has been a gradual shift from reactive measures to proactive actions within libraries across the globe when dealing with emergency management issues. They posit the university librarian needs to argue the case for disaster planning even if university administrators, under political and inner university pressures, neglect the needs of libraries. Our research results demonstrate that the driving factor behind the creation of an emergency management plan came from special collections librarians or university librarians, not from senior management within the university system. This highlights the need for university librarians to drive the change. Library management need to consider how they might deliver critical services if systems, processes or facilities are not available. When library employees realise that impact of a disaster can be reduced or eliminated though their own awareness and actions, this leads to an increase in library resilience in the face of disaster.

Conclusion

Special collections are a vital part of global heritage. While the issue of what constitutes heritage or cultural importance is a controversial discussion within itself, it is evident that the protection of cultural heritage held in university libraries as special collections is under researched.

The expertise of university librarians should not be undervalued. University librarians are able to assist in the global efforts informed by the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 Priority 3 (United Nations, Citation2015) to protect cultural and historical heritage in disasters through ensuring adequate plans are not only in place, but regularly revised and practiced.

An emergency management plan will never be perfect – adaptability is the key and this skill needs to be reflected and encouraged by the university librarian. Demonstrating adaptive leadership and considering essential systems, services and processes, will assist in creating a vulnerability matrix which will allow university librarians to identify preparedness measures. By engaging in relevant preparedness measures, special collections are better placed to be protected by library teams who can adapt to the changing nature of a disaster.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johanna Garnett

Johanna Garnett holds a BA Hons in History and Politics and Masters in Emergency Management and is currently undertaking a Postgraduate Certificate in Terrorism and Security Studies via Charles Sturt University. Her research interest includes building resilience of cultural and historical heritage to disruptive events. Johanna has previously worked in partnership with well-recognised historical homes in the UK and has a background in Public Relations and Communications.

Paul Arbon

Paul Arbon is a Matthew Flinders Distinguished Professor, internationally regarded in the field of resilience. He is Director of the Torrens Resilience Institute (TRI), a centre of excellence in the development of advanced thinking in the concepts of disruption and resilience. Becoming an Institute of Flinders University in 2014, TRI is a university-wide, interdisciplinary institute, assisting Federal and State Governments, emergency services, organisations and society to enhance leadership and management capabilities, thus, enabling them to prepare for, and respond better to, disruptive challenges.

David Howard

David Howard is currently University Librarian and Director of Student Success at RMIT University, having previously held the positions of University Librarian at Flinders University, South Australia and Edith Cowen University in Western Australia. He holds a Master’s Degree in Project Management and BA in History and Asian Studies. David has held various management positions in both technical and client services in several academic libraries since 2000. He is on several national and international committees connected to university libraries including the Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) and Council of Australian University Librarians Electronic Information Resources Consortium (CEIRC).

Valerie Ingham

Valerie Ingham lectures in Emergency Management at Charles Sturt University. She has extensive experience in the design and delivery of tertiary level programmes in emergency management, fire services, adult education and community services. She is a founding member of the Bangladesh Australia Disaster Research Group and her research interests include perceptions of risk and resilience in Bangladeshi and Australian communities, building community resilience and disaster recovery in the Blue Mountains NSW, time-pressured decision-making, and the tertiary education of emergency managers and fire investigators.

References

- AICCM. (n.d.). Disaster response. [online] Retrieved from https://aiccm.org.au/disaster/disaster-response

- Alegbeleye, B. (1993). Disaster control planning for libraries, archives and electronic data processing centres in Africa. Ibadan: Option Book Information Services.

- ALIA. (2010). ALIA - Disaster planning for libraries. Melbourne: Author. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/sites/default/files/documents/ALIA_Disaster_Planning_Libsfinal.pdf

- Allain, C., & Vallas, P. (2014). “Keep collections alive” The 12 January 2014 flood at the BnF as a lesson for the improvement of the emergency plan. Presentation, IFLA Conference, 2014, Lyon.

- Anbg.gov.au. (2010). DISACT - ACT Public collections disaster recovery. [Canberra] . Retrieved from http://www.anbg.gov.au/disact/

- Australian Library and Information Association. (2010). ALIA guide to disaster planning, response and recovery for libraries. Melbourne: ALIA. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/information-and-resources/disaster-planning

- Baker, E. (2018). Sunday’s deluge caused ‘extensive’ damage to ANU library, construction site. Canberra Times. Retrieved from http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/canberra-deluge-causes-extensive-flood-damage-to-books-in-anus-chifley-library-20180226-h0wnpj.html.

- Bansal, J. (2015). Disaster management in libraries: An overview. Gyankosh- the Journal of Library and Information Management, 6(1), 9.

- Basbanes, N. (1999). A gentle madness (1st ed., pp. 465–519). New York, NY: H. Holt.

- Beaumont, S. (2008). The water incident. Presentation, South Australia State Library, South Australia.

- Blackwood, F. (2018). Hobart flooding declared ‘catastrophe’ as wild Tasmanian storm eases and tracks north. ABC News. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-05-11/tasmanian-hobart-flood-and-storm-damage-declared-a-catastrophe/9752564

- Burke, L. (2016). The real fight behind uni of sydney student protests. News.Com.Au. Retrieved from http://www.news.com.au/finance/work/careers/the-real-fight-behind-the-violent-sydney-university-student-protests/news-story/58b8b177088e674adf28b336643c52f6

- Cady, S. (1999). Insuring the academic library collection. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 25(3), 211–215.

- Cass, L. (2014). Special collections in Australian University Libraries - Information for CAUL. Retrieved from http://archive2010.caul.edu.au/caul-programs/research/special-collections

- CAVAL. (2003). Disaster response plans survey. Melbourne: Author. Retrieved from http://www.caval.edu.au/assets/files/CRMG/RMG_TOR06.pdf

- CAVAL Risk Management Group. (2005). Library disaster response plan. Melbourne: CAVAL. Retrieved from http://www.caval.edu.au/assets/files/CRMG/DisasterPlan_generic_inc_OHSupdate24Aug05.pdf

- Corrigan, A. (2008). Disaster: Response and recovery at a major research library in New Orleans. Library Management, 29(4/5), 293–306.

- Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL). (1996). Regional Disaster Planning. [online]. Casuarina, Northern Territory: CAUL. Retrieved from http://archive.caul.edu.au/surveys/disaster.htm

- Cullingford, A. (2016). The special collections handbook (2nd ed., pp. 25–47). London: Facet Publishing.

- Cuthbert, S., & Doig, J. (1994). Disaster plans: Who needs them? Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 25(1), 13–18.

- Devine, S. (2005). The Florence flood of 1966: A report on the current state of preservation at the libraries and archives of Florence. The Paper Conservator, 29(1), 15–24.

- dPlan™: The Online Disaster-Planning Tool. (2006). Dplan.org. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from http://www.dplan.org/

- Echezona, R., Ugwu, C., & Ozioko, R. (2012). Disaster management in university libraries: Perceptions, problems and strategies. Journal of Library & Information Science, 2(1), 56–64. Retrieved from http://irjlis.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/6_IR033.pdf

- Falciani, S. (2017). The rare-book thief who looted college libraries in the ‘80s. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved April 23, 2018, from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/james-shinn-book-thief

- Fullerton, J. (2004). Disaster preparedness at the National Library of Australia. In World Library and Information Congress: 70th IFLA General Conference and Council (pp. 2–6). https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla70/papers/144e-Fullerton.pdf

- Gorman, M. (2007). The wrong path and the right path. New Library World, 108(11/12), 479–489.

- Graham, K., & Spennemann, D. (2006). Disaster management and cultural heritage: An investigation of knowledge and perceptions of New South Wales Rural fire service brigade captains. Australian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, (1), 5–31.

- Grant, A. (2000). Benighted! How the University library survived the auckland power crisis. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 31(2), 61–68.

- The Guardian. (2015). Fire in major Russian library destroys 1m historic documents. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/31/fire-russian-library-moscow-institute

- Hannah, S., Uhl-Bien, M., Avolio, B., & Cavarretta, F. (2009). A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(6), 897–919.

- Hayashi, C., & Soo, A. (2012). Adaptive leadership in times of crisis. Prism: A Journal of the Center for Complex Operations, 4, 1. Retrieved from https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-2854798871/adaptive-leadership-in-times-of-crisis

- Heifetz, R., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press.

- Hernon, P., Giesecke, J., & Alire, C. (2008). Academic librarians as emotionally intelligent leaders. The Library Quarterly, 79(3), 389–392.

- Hernon, P., & Rossiter, N. (2006). Emotional intelligence: Which traits are most prized? College & Research Libraries, 67, 260–275.

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). (2006). IFLA disaster preparedness and planning: A brief manual. Paris: IFLA-PAC. Retrieved from https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/8068

- Jadallah, A. (2017). Library burned [Image]. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/battle-against-isis-to-retake-mosul-iraq/5/

- Kostagiolas, P., Araka, I., Theodorou, R., & Bokos, G. (2011). Disaster management approaches for academic libraries: An issue not to be neglected in Greece. Library Management, 32(8/9), 516–530.

- Kraft, N. (2006). Major and minor mold outbreaks: Summer of 2002. Public Library Quarterly, 25(3–4), 127–141.

- Kreitz, P. (2009). Leadership and emotional intelligence: A Study of University Library directors and their senior management teams. College & Research Libraries, 70(6), 531–554.

- Lengfellner, L. (2011). Survey of emergency preparedness in the mobius academic libraries for fire, weather and earthquake Hazards (Masters). University of Central Missouri.

- MacDiarmid, C. (2017). Mosul University after ISIL: Damaged but defiant [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/01/mosul-university-isil-damaged-defiant-170120090207277.html

- Maina Abareh, H. (2014). Survey of disaster preparedness by heads of academic libraries in North-Eastern Nigeria. Global Journal of Academic Librarianship, 3(1), 45–57. Retrieved from http://www.irphouse.com/gjal/gjalv3n1_05.pdf

- Mannakkara, S., & Wilkinson, S. (2014). Re-conceptualising “Building Back Better” to improve post-disaster recovery. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 7(3), 327–341.

- Matthews, G., & Eden, P. (1996). Disaster management training in libraries. Library Review, 45(1), 30–38.

- Maylone, R. (1980). Preparing for emergencies and disasters (1st ed., pp. 354–357). Washington, D.C: Office of Management Studies, Association of Research Libraries.

- McCracken, P. (1995). Disaster planning in museums and libraries: A critical literature review. Katharine Sharp Review, (1): 1–9. Retrieved from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/78236

- Newman, D., & Harris, S. (2015). Lessons in disaster recovery from hurricane ivan: The Case of the University of the West Indies (UWI) Mona Library. In IFLA world library and information congress, 1–29. Cape Town: IFLA. Retrieved from http://library.ifla.org/1253/1/223-newman-en.pdf

- Palinkas, L., Horwitz, S., Green, C., Wisdom, J., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2013). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544.

- Parker, S. (2012). Innovation and change: Influences of pre-disaster library leadership in a post-disaster environment. Advances in Library Administration and Organization, 121–204. doi:10.1108/s0732-0671(2012)0000031006

- Pierard, C., Shoup, J., Clement, S., Emmons, M., Neely, T., & Wilkinson, F. (2016). Building back better libraries: Improving planning amidst disasters. Advances in Library Administration and Organization, 307–333. doi:10.1108/s0732-067120160000036014

- Quarantelli, E. (1998). “Where we have been and where we might go”, What is a Disaster? A dozen perspectives on the question (1st ed., pp. 146–159). London: Routledge.

- Raman, P., & Zach, L. (2010). Protecting information resources before and after emergencies. Information Outlook, 14(3), 25–27. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.flinders.edu.au/docview/347838903?accountid=10910

- Revolvy, L. (2018). “Library damage resulting from the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake” on Revolvy.com. Retrieved from https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Library+damage+resulting+from+the+2004+Indian+Ocean+earthquake&uid=1575

- Roberts, S. (2015). The library without walls: Striving for an excellent law library service post-earthquake. Legal Information Management, 15(04), 252–260.

- Saunders, M. (1993). How a library picked up the pieces after IRA blast. Library Association Record, 95(2), 100–101.

- Scott, J., & Wellheiser, J. (2003). An ounce of preservation: Integrated disaster planning for archives, libraries and record centres. Journal of the Society of Archivists, 24(1), 114–115. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/57611435/6A72A57B63C0425BPQ/2?accountid=10910

- Tandon, A. (2013). ICCROM program on disaster and risk management. Rome, Italy: ICCROM.

- Terminology - UNISDR. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology

- Tomljanovich, W., & Zećo, M. (1996). The National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the current war. The Library Quarterly, 66(3), 294–301.

- Ugwuanyi, R., Ugwu, M. E., & Ezema, K. (2015). Managing disasters in University Libraries in South East Nigeria: Preventative, technological and coping measures. Library Philosophy and Practice. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3456&context=libphilprac

- United Nations. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030. (2015). New York, NY: p. 19. Retrieved from. http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/43291.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2016) and International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property. Paris.

- University of Edinburgh. (2013). Disaster response and recovery plan for Rare/Unique collections. Edinburgh: Author. Retrieved from http://www.lhsa.lib.ed.ac.uk/conservation/DR&RPlan_edited_18.11.13.pdf

- Van der Hoeven, H., & van Albada, J. (1996). Lost memories - Libraries and archives destroyed in the twentieth century. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/webworld/mdm/administ/pdf/LOSTMEMO.PDF

- Wilkinson, F. (2015). Emotional intelligence in library disaster response assistance teams: Which competencies emerged? College & Research Libraries, 76(2), 188–204.

- Yasue, A. (2012). Disaster plans for collections: A “Must” for libraries. Daigaku-Toshokan-Kenkyu, 94, 32–38.