ABSTRACT

This article argues for the concept of public library as contemplative space. Public libraries, beyond their information access and public sphere functions, have an important role to play in cultivating the inner lives of their patrons. This situation is even more acute given the psychosocial maladies of our information age. This focus on contemplation is related to the growing interest in mindfulness both in LIS and wider society. However, contemplation is a wider and more effective term to use, as it can refer to a wide range of practices focused on enhancing interiority and promoting a deepened sense of meaning and purpose. Public libraries have an important role to play in providing more affordable, equitable, and inclusive access to contemplative practices through programming and other activities. The article also discusses specific examples of public library as contemplative space. These examples chart a course and vision for a deeper and potentially transformative understanding of how libraries can be effective contemplative spaces for society. In this vision, the health, well-being, and inner lives of patrons are front and centre.

Introduction

In the increasingly privatised and neoliberal societies we live in, public spaces are becoming a scarce resource. This phenomenon is not restricted to countries in the Western and so-called developed parts of the world, but also include areas in the Global South, where a majority of the world’s population lives (Pyati & Kamal, Citation2012). Given this reality, institutions such as galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs) have an important role to play in revitalising both the concept and living reality of public space. In this article, I focus on public libraries in a Western context (with a bias towards North America, given my geographic location), but the points I raise will likely have applicability to different GLAM contexts and other geographic areas as well, including Australia and New Zealand. Specifically, I focus on public libraries and their potential to serve as enhanced contemplative spaces for wider society. Therefore, the conceptual framework I introduce in this article (and by extension for the field of library and information science [LIS]) is public library as contemplative space.

This framework is crucial and necessary, particularly in a technologically dystopian neoliberal age. With psychosocial maladies related to the information age (e.g. overload, burnout, distraction, etc.) becoming more disturbingly evident by the day, what role can public libraries and librarians play in alleviating these concerns? This question is at the heart of this article. Given this premise, I advocate for librarians and LIS scholars to develop and highlight more the already existing contemplative potential in public libraries (such as meditation and yoga classes), while also reimagining the ways in which these institutions can contribute to the psychospiritual well-being of their patrons. The following sections will flesh out this framework further, one which weaves together diverse concepts and fields including: library as place; contemplative studies; critical studies of information and technology; information dystopia; critique of neoliberalism; commodification; and progressive or critical librarianship. As we will see, all of these elements are crucial for LIS to develop a coherent, forceful, and political response to these immense challenges we face. LIS scholars and practitioners have an important societal contribution to make in promoting the concept of public library as contemplative space, but we cannot wait any further. Therefore, we must act in a timely and critically informed fashion.

Library in the Soul of the User

The concept of library as place (Leckie, Citation2004, p. 233) has been a popular one in LIS for several years. This focus on library as place has usually been defined in relation to the concept of the ‘public sphere’ (Habermas, Citation1964, p. 50). This focus on the public sphere puts issues of information and democracy at the forefront, with public libraries having a crucial role to play in facilitating the free flow of information in a democratic society (Buschman, Citation2003). Moreover, research on library as place can include discussions about how libraries can promote the development of social capital, particularly in enhancing the social outcomes of marginalised patrons and populations (Griffis & Johnson, Citation2014).

In a slightly different vein, Wayne Wiegand (Citation2015) has challenged the dominant discourse in LIS surrounding the importance of libraries in promoting democracy. His research on public libraries has highlighted the significant role these institutions play in the promotion of leisure reading and storytelling in society, which is often overlooked in the dominant library as place discourse (Wiegand, Citation2015). This focus on leisure reading opens up new avenues to explore how public libraries are facilitating the inner lives of their patrons. Thus, we can easily overemphasise the civic importance of public libraries, while ignoring the valuable affective dimensions of these institutions. Furthermore, as Doug Zweizig (Citation1973) noted in his dissertation, LIS as both a field and profession needs to focus more on the ‘library in the life of the user’ and less on the ‘user in the life of the library’ (p. 15). While this statement has great merit, I propose that the LIS field and profession move further to consider the question of the library in the soul of the user.

This question I pose therefore speaks to the theme of this special issue, namely the ways in which public libraries can address the whole person. It is in this spirit I propose viewing public libraries also as contemplative spaces. This focus on contemplation is related to the growing interest in mindfulness in LIS (see Moniz, Eshleman, Slutzky, & Moniz, Citation2016); however, contemplation is a broader concept that encompasses various other traditions and practices that can allow for a deepened sense of meaning and purpose (Komjathy, Citation2018). As such, public libraries can be places of introspection, sanctuaries for soul and spirit, and sacred spaces, but in a secular setting. This emphasis on the contemplative dimensions of libraries is especially important, given the age of anxiety, distraction, and information overload that we live in.

The organisation of the article is as follows. The next section discusses in more detail the different meanings of contemplation, and brings LIS into discussion with the emerging field of contemplative studies. I follow this section with an exploration of the contemplative resurgence in society, particularly in relation to some of the psychosocial concerns of the information age. Following this discussion, I examine how the growing popularity of contemplative practices in society has a dark side, namely their increasing commodification. Given this reality, public libraries can serve as more accessible and affordable options for contemplative practice; as such, there are links between public library as contemplative space and progressive librarianship. The last section of the article explores some areas for future research and action, including an examination of the role of meditation classes in public libraries and how librarians might potentially guide patrons in using technology in a more mindful way.

Beyond Mindfulness: Library as Contemplative Space

Mindfulness is a buzzword in today’s world, as many of us have heard of it and some of us may have also practised it. Mindfulness, according to Jon Kabat-Zinn (Citation1994) ‘means paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally’ (p. 4). This definition of mindfulness is a dominant secular understanding of the concept, particularly with its emphasis on present moment awareness and elements of self-observation and self-inquiry. Given the scattered and chaotic nature of our thoughts (e.g. dwelling on the past, worrying about the future), mindfulness is a timely intervention in the age we live in.

Mindfulness can be related to meditation, but it also extends to a mode of awareness and a way of being that ultimately permeates everyday life (Kabat-Zinn, Citation1994). Mindfulness has roots in Buddhism, but in its current Westernised form, often does not make explicit reference to these origins (Purser & Loy, Citation2013). While the Westernisation of originally Eastern practices such as mindfulness runs the danger of cultural appropriation (Komjathy, Citation2018), secularisation is a dominant trend which has also expanded the reach of these practices.

There are numerous scientifically verified benefits of mindfulness practice, including enhanced cognitive performance, stress reduction, and general improvements in mental health (Tang, Holzel, & Posner, Citation2015). Given the efficacy of mindfulness, there is growing awareness within LIS about incorporating mindfulness into various aspects of the profession. For instance, Moniz et al. (Citation2016) discuss applying mindfulness to diverse areas such as: helping students with anxiety issues when working on research papers; aiding information literacy, particularly in relation to the guidelines of the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL); work in the service of others, especially at the reference desk; and the development of more thoughtful and caring library leaders. Moreover, Anzalone (Citation2015) describes the benefits of mindfulness in a law library setting, including the ability to be more present with patrons, dealing with workplace conflict and anxiety in healthier ways, as well as practicing better self-care in a high-stress environment.

As we can see, mindfulness has a number of benefits for librarianship and may be a perfect and logical fit for the field (Moniz et al., Citation2016). However, as mentioned earlier, mindfulness is only one example of contemplative practice, and library work need not be constrained to this one definition, however popular or timely. Therefore, I propose instead that librarianship engages more deeply with the concept of contemplation, and contemplative practice broadly speaking. This embrace of contemplation is more inclusive (particularly in our increasingly multicultural societies) and may also more accurately reflect the actual and potential work of libraries.

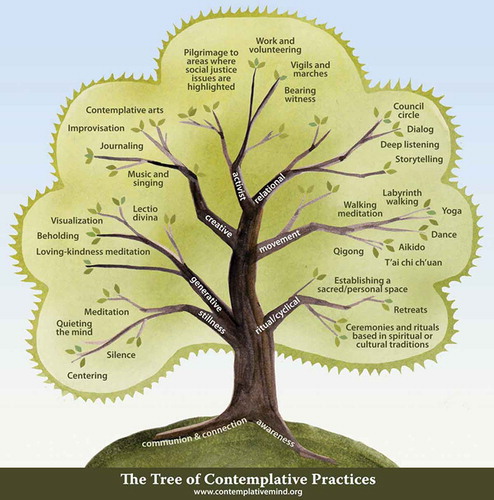

To give a better sense of the meaning of contemplative practice, the religious studies scholar Louis Komjathy (Citation2018) in his book Introducing contemplative studies emphasises the general characteristics of contemplative practice to be ‘attentiveness, awareness, interiority, presence, silence, transformation, and a deepened sense of meaning and purpose’ (p. 55). A number of religious and secular traditions all have these shared characteristics, and contemplation in this sense need not be conflated with the philosophical elitism of Plato or its more exclusive definition in Catholicism (e.g. contemplative prayer) (Komjathy, Citation2018). Keeping in line with this broad definition of contemplation, The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society (CMind), which is one of the major organisations supporting contemplative studies in higher education, has developed The Tree of Contemplative Practices, which describes the wide variety of contemplative practices available in society (see ).

In this conceptualisation, the roots of contemplative practice lie in awareness, as well as communion and connection. The various branches of this tree refer to the different typologies of contemplative practice: (1) stillness; (2) generative; (3) creative; (4) activist; (5) relational; (6) movement; and (7) ritual/cyclical. Therefore, practices like mindfulness and meditation can fit into the category of ‘stillness’ practices, while yoga and qigong can be categorised as ‘movement’ practices, and so on. Moreover, the broadness of these categories can be inclusive of many other contemplative practices from various spiritual and religious traditions, and also include less obvious forms of contemplation including improvisation, music, pilgrimages, and vigils (The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society, Citationn.d.).

The CMind tree that I have just highlighted is certainly not the final or most authoritative word on what constitutes contemplation or contemplative practice. However, I include it here as an influential definition of contemplative practice, and also to highlight the inclusive nature of what constitutes contemplation. With these points in mind, we can already see the contemplative dimensions of public libraries at work. For instance, they can be places of stillness and quiet for patrons, creative spaces of enjoyment (e.g. the presence of makerspaces, art classes, etc.), venues for deep listening and storytelling, and even places of conscious movement (e.g. the presence of yoga and tai chi classes), to name just a few. Later on I discuss some more specific examples and places of further inquiry into the nature of public libraries as contemplative spaces. But what I want to emphasise now is the increasing relevance of public libraries as contemplative spaces.

Ironically, while these institutions emphasise their role as purveyors of information, their more profound contributions may actually lie in the promotion of the inner lives of their patrons (Wiegand, Citation2015). This point is particularly true in an age of information overload; thus while many patrons still come to the library in search of information, an increasing number of patrons may actually be seeking refuge from hyper-stimulation and the overly demanding claims of technology. In essence, we may be escaping information when entering the library, and not always seeking it as is most often assumed. Given this context, the following section highlights the psychosocial perils of the information age, and illustrates how the wider contemplative resurgence in society is related to them.

Contemplation in an Age of Overload

Information Dystopia

While there is endless academic debate about the factors that constitute an ‘information society’ or ‘information age’ (Webster, Citation2014, p. 10), there is growing consensus that certain aspects of technological change are having unforeseen psychosocial consequences. For instance, nearly five decades ago the futurologist Alvin Toffler (Citation1970) discussed the idea of ‘information overload’ (p. 314), such that the growing amount of information in the world would be so much as to render people helpless and incapacitated to deal with this onslaught. While such statements may feel like an exaggeration, they are not so easily dismissed, particularly in relation to peoples’ current experiences with information and communication technologies (ICTs). For example, Bawden and Robinson (Citation2009) discuss the various ‘pathologies of information’ (p. 180) that plague our current age, including information overload, information anxiety, and frustrations with the impermanence of digital information. Moreover, there is concern about how social media can adversely affect intimate relationships (Turkle, Citation2015), with the psychologist Jean Twenge (Citation2017) describing how smartphone use may be related to a steep increase in mental health issues for teens. In addition, ICTs can shorten and make our attention spans more diffuse, often promoting distraction and the pursuit of less than efficient forms of multitasking behaviour (Levy, Wobbrock, Kaszniak, & Ostergren, Citation2012).

Keeping in line with this information dystopia, Jonathan Crary (Citation2013) describes an all-encompassing drive by governments and corporations to make our lives governed by a constant culture of alertness, such that sleep is our only refuge from a 24/7 deluge of consumerism. In addition, the philosopher Byung-Chul Han (Citation2015) describes our current age as a ‘burnout society’ (p. 35), with many of us in a constant state of doing and achieving, all the while feeling constantly unsatisfied and unfulfilled. Given this bleak picture, what are we to do? Unfortunately, the underlying context and potential solutions to these issues are complex. However, contemplative practices are being deployed to deal with some of these psychosocial concerns and can be quite effective at an individual level. The next section covers in more detail how contemplation can offer some relief and hope in this information dystopia.

Contemplative Interventions into Information Dystopia

Over the last decade or so, we are seeing a growing interest in contemplative practices in Western societies, particularly those that are more secular in nature. While this resurgence of contemplative practice is not solely related to the individual and social dysfunction I have described above, we can attribute a dominant strand of this renewed interest to a need for stress relief. As mentioned earlier, mindfulness has grown in popularity, especially as a stress relief tool. A prime example of this reality is Kabat-Zinn’s (Citation2013) greatly influential work on mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). The MBSR programme is a well-established, increasingly global, and acclaimed program with the primary focus of using mindfulness as a way to alleviate stress, pain, and illness (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2013).

In a slightly different vein but keeping in line with a more LIS and technology focus, University of Washington iSchool professor Levy’s (Citation2016) work on contemplative approaches to technology use is of great value. Stated simply, Levy (Citation2016) urges us to bring mindful awareness (e.g. awareness of our breathing, posture, body sensations, etc.) to our personal technology use habits, which is particularly useful in an age of information overload and anxiety. If technology use and its associated social demands are major causes of stress for individuals, then it makes eminent sense to use contemplative methods to help us understand more clearly how we use technology and consequently how we can modify our behaviour to develop more personally meaningful and healthy technology use habits. As Levy (Citation2016) notes, few of us realise something as routine as email checking can be such a highly emotional exercise; in fact, much of our technology use habits are about mediating relationships. If mindful awareness can lead to healthier and less reactive relationships with our technological tools (and by extension with other people), then perhaps we have made our own experience of the information age somewhat less dystopian.

On a related note, the MIT professor Turkle (Citation2015) discusses how excessive use of our technological devices and social media may lead to a loss of meaningful connections and conversations, especially of a face-to-face nature. Therefore, it becomes important to foster time for personal reflection and solitude, particularly as these activities can get us in touch with a deeper sense of meaning and purpose (Turkle, Citation2015). While she does not mention the word contemplation directly, her emphasis on using technology in a more balanced and less obsessive way has contemplative overtones. In addition, another way to conceive of healthier uses of technology might include taking a technology sabbatical (i.e. ‘unplugging’), either occasionally or on a regular basis in one’s life (Levy, Citation2016; Powers, Citation2010).

Commodification and Exclusion

Neoliberalism in the Information Age

While I have discussed aspects of information dystopia and how contemplative approaches can respond to this crisis, this discussion has mainly focused on what we can do at an individual level. However, this crisis is one that is also firmly rooted in problematic social, economic, and political contexts. In particular, we must understand that we live in a neoliberal era; the information age itself is deeply intertwined with neoliberal political, economic, and cultural changes. Harvey (Citation2005) traces the origins of neoliberal ideology from the late 70s/early 80s, with figures such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan playing a large role in its global spread, as much of the world’s countries are now (either implicitly or explicitly) operating under neoliberal conditions. As an ideology and a set of political-economic practices, neoliberalism posits that human well-being is best promoted by ‘liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade' (Harvey, Citation2005, p. 2). Moreover, deregulation, privatisation, and the withdrawal of the state from most areas of social provision (including public libraries) is often associated with it (Harvey, Citation2005). Growing social and economic inequality is often the result (Reich, Citation2015; Stiglitz, Citation2013), with even the richest country in the world, the United States, exhibiting disturbing levels of inequality and poverty (Alston, Citation2017).

The aforementioned social, political, and economic developments can be directly linked to the psychosocial concerns mentioned earlier. For instance, governments that have lessened or abandoned their social welfare provisions in favour of more market-based solutions can leave individuals in positions where they have to fend for themselves in terms of finding appropriate medical care, education, and so on. Workplaces have also invested less in their employees over time, shedding full-time positions with pensions and increasing the numbers of flexible and part-time workers, ironically (or rather perversely) in the name of freedom and worker choice (Boltanski & Chiapello, Citation2007).

Commodification of Contemplative Practices

In line with the logic of neoliberalism, contemplative practices are also becoming heavily commodified, and a dominant understanding of their value is through their ability to become valuable commodities. In the case of mindfulness, we can see this process at work in the phenomenon of McMindfulness (Purser & Loy, Citation2013). McMindfulness describes a reality in which mindfulness and capitalism seamlessly blend into each other, with the Buddhist roots of mindfulness (particularly Buddhist social ethics such as right livelihood, right speech, etc.) obscured by an overly secularised and commodified orientation (Purser & Loy, Citation2013). Thus, mindfulness can become a catch-all phrase and method which is then deployed in a variety of disparate fields, with seemingly predictable and uniform results. With a deracinated and commodified mindfulness the norm, can an assassin or corporate raider also be mindful (Purser & Loy, Citation2013)? Therefore, mindfulness without wholesome intentions and positive mental qualities may not really be mindfulness at all (Purser & Loy, Citation2013).

Kabat-Zinn (Citation1994) notes that mindfulness is not trying to ‘sell you anything, especially not a new belief system or ideology’ (p. 6). While this statement may be true at a practice-based and experiential level, it is not entirely accurate in describing the social realities of mindfulness practice. For, as Wilson (Citation2014) notes in Mindful America: The Mutual Transformation of Buddhist Meditation and American Culture, mindfulness is big business. Specifically, Wilson (Citation2014) observes how ‘mindfulness itself can never be commodified, because the act of awareness cannot be literally packaged, bottled, measured, transmitted, weighed, or measured' (p. 136). However, he further discusses that:

Given this conundrum, peddlers of mindfulness must take two indirect approaches: they must either sell auxiliary products designed to introduce or augment mindfulness, or sell their expertise at teaching mindfulness and delivering the benefits of mindfulness. (p. 136)

For example, the presence of expensive mindfulness and meditation retreats, various gadgets (e.g. exorbitantly priced sitting cushions, meditation timers, fragrances/incense, etc.), and the celebrity-like status of famous mindfulness teachers all bear testimony to these observations. While some would argue there is nothing wrong with making huge sums of money in the business of mindfulness (particularly in a capitalist society), we must consider issues of access, affordability, and privilege. Therefore, who has access to practices like mindfulness and which types of people are part of the mindfulness movement have to be considered. Thus, factors such as race, economic status, class, gender, and sexual orientation come into focus, including issues of white privilege in mindfulness practice (Ng & Purser, Citation2015).

Contemplation and Progressive Librarianship

Given the impact of neoliberalism and commodification on contemplative practices, we can begin making connections between contemplative practice in the library and the wider critique of neoliberalism within LIS. For the last few decades, scholars in LIS have been concerned with the growing commodification and corporatisation of library services, with Buschman (Citation2003) in particular concerned with the creeping in of business culture and logic into library services. As such, neoliberalism has become such a dominant feature of our cultural life that public libraries are adapting to this reality through the use of language such as customer instead of patron/user, and the imitation of services in market-driven spaces like bookstores and other retail stores (Buschman, Citation2003). This reality can lead to greater exclusion of certain populations (e.g. homeless people, disadvantaged minorities, etc.) in favour of more ‘desirable’ customers. Therefore, the essential function of libraries in promoting the public sphere can be in jeopardy, as the public is viewed more as a collection of individuals and customers, rather than as a group of citizens (Buschman, Citation2017).

This situation has led LIS scholars such as Trosow (Citation2014) to declare more concretely how the profession can resist neoliberal trends. Specifically, Trosow and other more activist-oriented LIS scholars and librarians are drawn to the growing subfield of progressive librarianship (sometimes known as critical librarianship). Progressive librarianship can be described as an approach that ‘protects the public sphere, resists marketization, defends the notion of information as a public good, and which builds general support for public information services’ (Trosow, Citation2014, p. 17).

The previous discussion on the commodification of contemplative practices in society dovetails nicely with the progressive librarianship movement. Specifically, given the exorbitant costs of certain popular contemplative practices described above, public libraries can serve as low-cost and accessible spaces for the public to engage in contemplative practices. For instance, yoga classes, meditation groups, tai chi classes, etc. can all be provided at public libraries at either little to no cost. Moreover, public libraries provide a secular and non-sectarian space for people of all faiths (including no faith whatsoever) to engage in contemplative practices, whether of a formal or informal variety. Therefore, public libraries can support the public sphere by also providing more equitable and inclusive access to contemplative practices, irrespective of income, class, race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and so forth. As far as I am aware, no research has yet looked at this connection between enhanced access to contemplative practices as part of the progressive librarianship framework. More work and research is needed to flesh out this connection. With this point in mind, the next section explores some possible avenues for further action and research.

Moving Forward: A Framework for Action and Research

This section is more speculative and aspirational in nature, as it sketches a framework for both a future research and action-oriented agenda in LIS within the concept of public library as contemplative space. This framework is meant for LIS practitioners and scholars alike. Given its exploratory nature, I invite others to take up these agenda items, critique them, and think of other areas that come to mind. As such, this effort is not meant to be an exhaustive or comprehensive one; rather, it is meant to stimulate discussion and further inquiry.

Meditation Classes at Public Libraries

At this point, an understudied phenomenon in public libraries is the increasing presence of meditation and/or mindfulness programmes. From a cursory perusal of the websites of a few major public library websites in Australia and North America (see, for example, Meditation Station at Haymarket Library, Sydney: https://whatson.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/events/meditation-station-haymarket-library; New York Public Library: https://www.nypl.org/events/programs/2019/05/18/meditation-and-relaxation; London, Ontario [Canada] Public Library: http://www.londonpubliclibrary.ca/blog/2017/04/18/mmstaff/noon-meditation-coming-back-central-library-%E2%80%93-may-2), we can see the promotion of meditation programs at libraries. One idea for a research study would be to understand the impacts of these programs on patrons. A study by LIS researchers and/or practitioners might address questions such as: (1) What are some of the reasons and motivations for patrons to attend these programs? (2) Why are people choosing to learn mindfulness or meditation specifically at the library? (3) Have they learned mindfulness or meditation in other venues, and if so, how does their library experience compare to other ones in private centres? and (4) What does the presence of these programs tell us about the nature or potential of libraries to be contemplative spaces? These questions are just a sampling of what could be considered. Moreover, researchers can begin with pilot studies in one or a few libraries, with the potential to scale the research up to include a more systematic study of different library systems in a region and/or a country.

What this research agenda can highlight as well is the nature of public libraries as contemplative spaces in relation to other contemplative spaces in wider society. In other words, how might contemplative space in a public library compare to the experience someone may have in a quiet church, mosque, synagogue, or temple? What role is the library playing in the soul of the user, particularly in relation to these other spaces? Should public libraries adopt some of the qualities of these other spaces (albeit in a secular manner) or provide an alternative type of contemplative space compared to more overtly religious and spiritual ones? In addition, with religious affiliation and formal attendance at religious services declining across the Western world, more people are identifying as spiritual but not religious (Carrette & King, Citation2005). With this point in mind, what role do public libraries play in facilitating this increasingly spiritual but less religious orientation of the general populace? Can we conceive of the library then as a place of spiritual uplift for patrons?

Librarians as Contemplative Technology Stewards

While the previous example has more of a research focus with implications for action, another area to consider involves an activist agenda for librarians. Specifically, given the information dystopia described in this article, can we imagine a new role for public librarians as being that of contemplative technology stewards for patrons? In particular, I am drawing on Levy’s (Citation2016) work on contemplative approaches to technology, which I discussed earlier. With Levy’s approach in mind, can we imagine a professional world in which more librarians become contemplative practitioners themselves? And with this sustained knowledge and practice of contemplation, can they apply this expertise to the use of technology? The consideration of these questions would certainly require a radical change in LIS education, with Masters of Library and Information Science (MLIS) students needing the option to take courses on mindfulness and contemplation within their LIS curriculum, along with having the ability to get trained as contemplative teachers in a particular tradition (most likely done outside of formal study).

Despite these caveats, however, there may be tremendous potential in this shift of orientation. Public librarians who are skilled contemplative practitioners and who also practice mindful and healthy approaches to technology use can be a great asset to patrons who are overwhelmed by the demands of the information age. For instance, librarians can run programs for patrons on how certain technological habits can increase stress levels, and work with patrons to find more effective strategies for technological use. Furthermore, the very fact that some public librarians will have contemplative skill sets can change the value of the profession; more than providing access to information and resources, the public librarian can be increasingly seen as someone who contributes to the health and well-being of both patrons and the wider communities they serve. This focus on well-being is also important in how librarians can use contemplative practices for self-care in high-stress environments (Anzalone, Citation2015), and also to foster compassion and kindness in the service of patrons (Chabot, Citation2019).

Spiritual and Religious Information Needs

In addition to the more concrete examples mentioned above, some other lines of inquiry regarding contemplation and public libraries come to mind. For example, we may also want to consider the public library’s role in addressing the spiritual and religious information needs of patrons. Thus, patrons may come to the public library with certain spiritual and religious questions in mind, particularly if they are concerned with learning more about a particular spiritual and religious tradition. If we conceive of public libraries also as contemplative spaces, what types of resources and programs can support these needs?

Moreover, the case of spiritual or religious information behaviour is often filled with existential questions about the nature of reality and life’s ultimate purpose (Chabot, Citation2019). Given the depth of this phenomenon, are librarians and the wider field of LIS comfortable with making room as well for the existential and spiritual needs of patrons? In addition, spiritual or religious revelation may force us to question the meaning of ‘information’ itself, as these types of insights often come from within and are not necessarily measurable or easily identified in the outside world (Chabot, Citation2019). Thus, should public librarians be open as well to providing meditation cushions, yoga mats, and other contemplative spaces and accoutrements in order to facilitate the spiritual, ‘inner’ information needs of patrons (Chabot, Citation2019)?

Contemplative Activism

On a final note, I would like to address the issue of neoliberalism and its effects on both public libraries and contemplative practice. I mentioned earlier how neoliberalism is related to the structural factors that contribute to an information dystopia; as such, individual approaches to push back against the stresses and maladies of our age (including engaging in contemplative practice at public libraries) may not be adequate. Thus, one can do a copious amount of mindfulness or yoga practice, but the material realities of inconsistent work, low pay, inadequate benefits, and defunding of social services (including public libraries) will continue to cast their odious shadows. This conundrum is not so easily resolved.

However, as mentioned earlier, the sub-field of progressive or critical librarianship does offer some hope in pushing back at an advocacy and policy level against the egregious excesses of neoliberal policies. More work is certainly needed on this level, but contemplative practice also has much to offer in promoting a progressive librarianship agenda. For instance, there is a long history of contemplative activism in global struggles for social change, which usually combines deep reflection and critically informed action (Pyati, Citation2018). The work and lives of such luminaries as Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. come to mind, with their focus on peaceful resistance and civil disobedience in the Indian independence and U.S. civil rights struggles, respectively. In addition, mindfulness and other contemplative approaches are being incorporated into anti-oppression and social justice struggles, to help us understand our own biases, find more compassion for others who are suffering, and also for our own self-care (Berila, Citation2014; Magee, Citation2016). With these points in mind, activist librarians who engage in contemplative practice may be better able to find the inner strength and calm they need to advocate for a post-neoliberal library future.

Conclusion

This article has argued for the concept of public library as contemplative space. Building on the concept of the library in the life of the user, I have also advocated for the consideration of the library in the soul of the user. Thus public libraries, beyond their information access and public sphere functions, have an important role to play in cultivating the inner lives of their patrons. This situation is even more acute given the psychosocial maladies of our information age. In addition, neoliberalism exacerbates the conditions of this information dystopia.

I have discussed the important emerging interest in mindfulness both in LIS and wider society, as this phenomenon is related to and can address some of these dystopian concerns. However, contemplation is a wider and more effective term to use, as it can include mindfulness but also can refer to a wide range of practices such as yoga, tai chi, qigong, conscious movement, the cultivation of sacred space, and so on. While contemplative practices can provide relief from stress and foster inner peace, they are also being commodified and made less accessible in a neoliberal age. Therefore, public libraries have an important role to play in providing more affordable, equitable, and inclusive access to contemplative practices through programming and other activities. As such, this ability to combat the commodification of contemplative practice also brings the concept of public library as contemplative space into conversation with progressive or critical librarianship.

In terms of specific examples of public library as contemplative space, I have discussed potential research studies of meditation and mindfulness programs in public libraries, as well as the possibility of public librarians taking on the role of mindful technology stewards for patrons and the general public. While these examples are more speculative and aspirational, they chart a course and vision for a deeper and potentially transformative understanding of how libraries can be effective contemplative spaces for society. In this vision, the health, well-being, and inner lives of patrons are front and centre.

I end this article with a quote from the great Trappist monk, writer, and social activist Thomas Merton. Though he died over 50 years ago, his words on contemplation and the contemplative life still retain their vitality, freshness, and urgency. He writes:

… since the direct and pure experience of reality in its ultimate root is man’s [sic] deepest need, contemplation must be possible if man [sic] is to remain human. If contemplation is no longer possible, then man’s [sic] life has lost the spiritual orientation upon which everything else – order, peace, happiness, sanity – must depend. (Merton, Citation1968, pp. 225–226)

I hope, therefore, that I have contributed in some way to understanding the potential of public libraries and the library profession to help us remain human, particularly in these challenging times.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ajit K. Pyati

Ajit K. Pyati is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Information and Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario (London, Canada).

References

- Alston, P. (2017, December 15). Statement on visit to the USA, by professor Philip Alston, United Nations special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22533

- Anzalone, F. M. (2015). Zen and the art of multitasking. Law Library Journal, 107(4), 2015–2027.

- Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of information: Overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 180–191.

- Berila, B. (2014). Contemplating the effects of oppression: Integrating mindfulness into diversity classrooms. Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 1(1), 55–68.

- Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, E. (2007). The new spirit of capitalism. London: Verso.

- Buschman, J. (2003). Dismantling the public sphere: Situating and sustaining librarianship in the age of the new public philosophy. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Buschman, J. (2017). The library in the life of the public: Implications of a neoliberal age. Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 87(1), 55–70.

- Carrette, J., & King, R. (2005). Selling spirituality: The silent takeover of religion. New York: Routledge.

- The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. (n.d.). The Tree of Contemplative Practices. Retrieved from http://www.contemplativemind.org/practices/tree

- Chabot, R. (2019). The information practices of New Kadampa Buddhists: From “dharma of scripture” to “dharma of insight” (Doctoral dissertation). Scholarship@Western. Retrieved from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6099/

- Crary, J. (2013). 24/7: Late capitalism and the ends of sleep. London: Verso.

- Griffis, M. R., & Johnson, C. A. (2014). Social capital and inclusion in rural public libraries: A qualitative approach. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 46(2), 96–109.

- Habermas, J. (1964). The public sphere: An encyclopedia article. ( S. Lennox & F. Lennox Trans.). New German Critique, 3, 49–55.

- Han, B.-C. (2015). The burnout society. Stanford, CA: Stanford.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hachette.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living. New York: Bantam.

- Komjathy, L. (2018). Introducing contemplative studies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Leckie, G. (2004). Three perspectives on libraries as public spaces. Feliciter, 50(6), 233–236.

- Levy, D. M. (2016). Mindful tech. New Haven, CT: Yale.

- Levy, D. M., Wobbrock, J. O., Kaszniak, A. W., & Ostergren, M. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation training on multitasking in a high-stress information environment. Proceedings of the 38th Graphics Interface Conference 2012 (pp. 45–52). Toronto.

- Magee, R. V. (2016). The way of Colorinsight: Understanding race and law effectively through mindfulness-based colorinsight practices. Georgetown Journal of Modern Critical Race Perspectives, 8, 251–302.

- Merton, T. (1968). The contemplative life in the modern World. In P. F. O’Connell Ed., 2013, Thomas Merton: Selected essays (pp. 225–231). Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

- Moniz, R., Eshleman, J. H., Slutzky, H., & Moniz, L. (2016). The mindful librarian: Connecting the practice of mindfulness to librarianship. Waltham, MA: Chandos.

- Ng, E., & Purser, R. (2015). White privilege and the mindfulness movement. Buddhist peace fellowship. Retrieved from http://www.buddhistpeacefellowship.org/white-privilege-the-mindfulness-movement/

- Powers, W. (2010). Hamlet’s Blackberry: A practical philosophy for building a good life in the digital age. New York: Harper Collins.

- Purser, R., & Loy, D. (2013, July 1). Beyond McMindfulness. Huffpost. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com

- Pyati, A. (2018, December 16). The importance of thoughtful resistance in the age of Trump. The Conversation. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com.

- Pyati, A. K., & Kamal, A. M. (2012). Rethinking community and public space from the margins: A study of community libraries in Bangalore’s slums. Area, 44(3), 336–343.

- Reich, R. B. (2015). Saving capitalism: For the many, not the few. New York: Vintage.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2013). The price of inequality: How today’s divided society endangers our future. New York: Norton.

- Tang, Y., Holzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 16, 213–225.

- Toffler, A. (1970). Future shock. New York: Random House.

- Trosow, S. E. (2014). The commodification of information and the public good: New challenges for a progressive librarianship. Progressive Librarian, 43, 17–29.

- Turkle, S. (2015). Reclaiming conversation: The power of talk in a digital age. New York: Penguin.

- Twenge, J. M. (2017, September). Have smartphones destroyed a generation? The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com

- Webster, F. (2014). Theories of the information society (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

- Wiegand, W. A. (2015). Tunnel vision and blind spots reconsidered: Part of our lives (2015) as a test case. Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 85(4), 347–370.

- Wilson, J. (2014). Mindful America: The mutual transformation of Buddhist meditation and American culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zweizig, D. (1973). Predicting amount of library use: An empirical study of the public library in the life of the adult public (Doctoral dissertation) Retrieved from WorldCat.