ABSTRACT

While selfies continue to be characterised as part of a narcissistic moment in current history, when embedded as part of a library engagement project, they convey a wealth of nuanced material about their subjects, the role of the library, and perceptions about memory. Social photography, through applications such as Instagram, can reveal much about the social and cultural life of a place and its people and in turn, generate insights into what is valued. Yet few studies have focussed on libraries and Instagram, and almost none to date have examined the public library context. This article examines publicly-generated Instagram data created during a large library project in Australia to argue that the role of the library as memory collector and shaper of histories about people and place is critical to the exchange that occurred via way of selfies. Photographic portraits of the self – intimate and personal digital objects – are eagerly exchanged in turn for an opportunity to be remembered and for participating in a project that assembles and shapes public memory. Findings suggest that social photography projects containing intersections of people, libraries and memorialising a moment in time are powerful ways in which library publics can be engaged.

Introduction

Selfies continue to be characterised as part of a narcissistic moment in current history (Gerges, Citation2018). Yet when they become embedded as part of a library outreach and engagement project, they convey a wealth of nuanced material about their subjects, the role of the library, and the perceptions of memory. However, social photography and selfies, through applications such as Instagram, can reveal much about the social and cultural life of a place and its people and in turn, generate insights into what is valued (see for example, Arias, Citation2018; Budge, Citation2017, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Budge & Burness, Citation2018; Burness, Citation2016; Manovich, Citation2014-2016; Stylianou-Lambert, Citation2017; Suess, Citation2018; Tifentale & Manovich, Citation2013; Warfield, Citation2014). Yet few studies have focussed on libraries and Instagram, and almost none to date have examined public libraries, their users and their Instagram posts.

This article examines publicly-generated Instagram data created during a large library project in New South Wales (NSW), Australia that asked: what does the face of NSW look like in 2018? Through content analysis of visual and text-based data, I argue that the role of the library as memory collector and shaper of histories about people and place is critical to the exchange that occurred via way of selfies.

Social Photography and Instagram

Social photography, a subset of photography, evolved through the capacities of twenty-first century digital technologies (for example, smart phones), and the introduction of social media in the mid-2000s. Instagram, due to the sheer number of its users – estimated to be one billion monthly (Constine, Citation2018) – is a central player in the social photography arena as it currently stands in 2019. As an app, Instagram relies on the networked impact of social photography to be effective.

Photography (both still and video) has become a large part of what is shared on social media because of the high-quality camera capabilities of smart phones and their ease of use. In the early years, Flickr, a photo-sharing platform launched in 2000, played a significant role in launching and popularising the idea of social photography. Today that space is commanded by Instagram. However, as a form of photography, social photography is evolving all the time.

Instagram stands as a significant platform where much social life is represented and explored and then shared with the world. This is played out through vast social networks enabled via algorithms and the active use of those who engage with the platform (Hochman & Manovich, Citation2013). Launched in 2010, Instagram commands increasing power and attracts much attention across a range of industries and sectors due to its significant uptake among the general population. Interestingly and importantly, 80% of Instagram users come from outside the United States (Booton, Citation2016) indicating its global use and reach, beckoning researchers to consider what that might enable us to ‘see’ and understand about contemporary cultural and social life. Libraries too have come to understand the power of social photography and the capacity to reveal more about its audiences as the research in this article showcases.

Social Media, Social Photography and Libraries

To date, there has been almost no research about social photography, particularly Instagram, in relation to libraries. While Twitter has captured the imaginations of researchers interested in the nexus between libraries and social media (see for example, Jones & Harvey, Citation2016; Cavanagh, Citation2015; Canty, Citation2012) there has been very little research that explores the realm of social photography (an extremely visual medium by nature) and libraries, especially public libraries. The little attention that has been given to this space includes an industry panel discussion in Australia about professional Instagram profiles held relatively early on in the life of Instagram as a platform (Abbott, Donaghey, Hare, & Hopkins, Citation2013), and work by Tekulve and Kelly (Citation2013) describing how they use Instagram on behalf of their institutions (in the USA) to engage library users. The information in Tekulve and Kelly’s article is primarily focussed on the pragmatics of Instagram use for library staff, including the benefits. While some attention is paid to library users and their Instagram content via way of small contests hosted by libraries, very little attention is given to the content of the posts made by library publics and what this might suggest about their perception of the library (or any library), themselves and what they value.

This scarcity of scholarship focusing on social photography and libraries is probably due to the emergent nature of this field of inquiry and the ways in which scholars have tended to focus on text-heavy social media platforms because visual media-oriented platforms (such as Instagram) require specific analytical skill sets. Despite this, studies exploring the content of museum visitor Instagram posts have recently occurred in the museum sector (see for example, Budge, Citation2017; Budge & Burness, Citation2018; Suess, Citation2018) and may offer insights from which the world of public libraries can learn and adapt to their particular nuanced contexts. Some of these studies have highlighted how exhibition material has been of central focus to the posts shared on Instagram (Budge, Citation2017; Budge & Burness, Citation2018; Suess, Citation2018) rather than self-portraiture photography (colloquially known as ‘selfies’) as mainstream media coverage suggests.

In summary, studies of museum visitor-generated Instagram content indicates that museum and exhibition objects are of immense interest (Budge, Citation2017; Budge & Burness, Citation2018), that visitors possess agency and authority in their practices, and that Instagram assists in this process (Budge & Burness, Citation2018). In addition, visitors’ use of Instagram is connected to extending their aesthetic experience (Suess, Citation2018). In the broader field of music festivals, Nicholas Carah argues that images posted on Instagram and other platforms ‘work as a device for registering relationships and experiences from material cultural spaces on the databases of social media’ (Citation2014, p. 4) suggesting the relevance of studying this phenomenon in the library context.

Cultural Institutions and Engaging with Publics

Most cultural institutions, including libraries, value knowing about and engaging with their various publics. This is important for both internal and external reasons. Internally, cultural institutions need to understand the visitor perspective and visitation patterns in order to remain responsive (Zorloni, Citation2010). Externally, most institutions are required to report visitation and satisfaction data to their boards and funding bodies for both transparency and reasons justifying the arts in light of uncertain government spending (Bentley, Citation2009). Thus, understanding the patterns, behaviours and interests of visitors is important and libraries possess a desire to keep abreast of this information like any other cultural institution (Pöldaas, Citation2015).

Visitation studies is a field of scholarly inquiry with increasing interest and the range of methods and theoretical approaches undertaken is developing (Davidson, Citation2015). Cultural tourism too, offers great insight into methods being used (see Kastenholz, Eusebio, & Carneiro, Citation2013). There is much that can be drawn from these areas of study to inform cultural institutions seeking to deepen their engagement with their various publics. Methodological usage is one domain in which much can be learned with Emily Dawson and Eric Jenson arguing for developing approaches that challenge the status quo and offer a more ‘contextually sensitive framework’ (Citation2011, p. 127).

There are various ways visitation studies are carried out. For example, simply quantifying visitation and short exit surveys are popular, however, these methods are surface level and are limited in terms of the insights they can generate. Observations are another method used but this, like all research methods, requires careful consideration of ethics so as not to create an intrusion into the visitor’s experience (Linaker, Citation2018). Other methods need to be deployed in order to get to the heart of understanding who library publics are, what they look like and value. Focus groups are one such avenue (see for example, Kelly, Citation2018). Social photography is another innovative method that enables a deeper, visual oriented exploration of these key questions pushing beyond what can be known via other quantitative or brief qualitative methods (such as exit surveys).

Memory

The role of memory is deeply entwined in the workings of cultural institutions and this is especially so with libraries as custodians and shapers of history. Edward Casey argues that memory is composed of four types: ‘individual memory, social memory, collective memory, and public memory proper’ (Citation2004, p. 20). Within this schema, social memory is ‘the memory held in common by those who are affiliated either by kinship ties, by geographical proximity in neighbourhoods, cities, and other regions, or by engagement in a common project. In other words, it is memory shared by those who are already related to each other, whether by way of family or friendship or civic acquaintance’ (p. 21). Public memory, however, ‘is both attached to a past (typically an originating event of some sort) and acts to ensure a future of further remembering of that same event’ (p. 17). Large public libraries with significant mandates act like monuments in creating and reinforcing public history in that they do ‘not merely embody or represent an event (or person, or group of persons), but strive to preserve its memory in times to come’ (p. 18).

The nexus between social and public memory serves as an interesting intersection in which projects with library publics in social domains (such as social media) can be examined. In this article, I use Casey’s conceptions of memory as a framework to understand the meanings associated with social acts contributing to public memory in relation to publicly-generated Instagram data created during a large library project in 2018–2019 at the State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW) in Sydney, Australia.

Research Approach

In mid-2018, the SLNSW set out to understand what the face of Australia’s most populous state looks like through a project titled #NewSelfWales. Through Instagram and a four-month in-gallery exhibition, the public was asked to submit self-portraits (or selfies) which the Library would collect and keep alongside their extensive portrait collection in the form of paintings and photographs. On Instagram, the hashtag #NewSelfWales was used as a way to collect the public portraits posted there.

Later in the project photos were also generated by an in-gallery photobooth established in a gallery showcasing both the public portraits and those in the library collection (see ). The research articulated here focusses on the Instagram-generated data.

Figure 1. Gallery image of #newselfwales exhibition, State Library of NSW, Sydney Photography credit: author’s own.

The research approach undertaken involved content analysis of visual and text-based data based on the methods used in previous studies of this nature (Arias, Citation2018; Budge, Citation2017; Budge & Burness, Citation2018; Suess, Citation2018). Content analysis requires the researcher to study the information contained in posts at both a detailed, micro-level and at a broader, macro-level. This work involves generating meaningful descriptions that become codes and then themes, that explain the content that users have uploaded to Instagram. During this process, the researcher considers the literature and the key findings, concerns and insights gained from previous research and can draw on this to shape codes and themes from the data at hand. Sometimes content analysis occurs using computers which automate the process however, this approach was not undertaken in the #newselfwales project. Computerised automated content is still evolving as a technology and is highly flawed at understanding images and in relation to interpreting nuances in both text and image-based content.

A three-stage sampling approach was established and implemented as the most feasible and manageable way to handle the data given that at the outset, the quantity of posts to be produced by visitors was unknown. We decided to sample over three time periods during the life of the project – beginning, middle and the end – as a way to generate a good cross-section of Instagram posts. The first sample of 200 posts was generated during the pre-launch period, about six weeks out from the opening of the exhibition space: 22 August 2018. Selecting a sample from this point and not the very beginning of the post period (when the hashtag first ‘went live’ on 1 June 2018) means we were more likely to encounter ‘authentic’ posts from the community and not those made as part of the Library promotion of the project including those of Instagram Influencers. The second sampling period occurred during the middle of the project and a week following the launch the exhibition: 12 October 2018. We anticipated this being a peak period of activity for the project hashtag given a series of gallery launches was planned for early October. The third and final sample of posts was generated on 1 February 2019, just a short period before the exhibition closed on 17 February. In each of the sampling periods 200 of the most recent posts in date/time order were accessed and placed into a stable digital environment for research purposes. In all, over the three sampling periods, 600 Instagram posts using the project hashtag were studied out a total of 1734 posts made by those who posted during the project period. We found that the majority of posts were made during the beginning of the project during the first and second sampling periods.

Handling the Data

We drew from Sarah Pink’s approach in Doing Visual Ethnographies (Citation2013) and Gillian Rose in Visual Methodologies (Citation2012) when working with Instagram data due to the extensive visual properties an Instagram post contains. To ensure we were working with a stable data set (Instagram users can delete or add posts at any time) we ‘captured’ the data by taking it from the live Instagram environment to a static one. Using the project hashtag as a tool to identify relevant posts for the study sample, we then deposited these into a digital file so that they could be maintained for exploration during analysis.

The content of posts, both visual and text, were then ‘read’ – the process described earlier of studying the content at both the micro- and macro-levels – and coded using a thematic approach. Data were explored for patterns and relationships, and to ‘find[ing] explanations for what is observed’ through segmenting and reassembling (Boeije, Citation2010, p. 76). A central focus was to ‘ask questions of the data’ as we worked through analysis of it (Neuman, Citation2000, p. 420). The research questions, purpose, and overall design guided analysis. From here patterns and themes emerged quickly. We used a process of inductive coding (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008) to group the data. That is, the codes were developed from the data itself using a bottom-up method (rather than imposing preconceived codes).

Findings: Identity, Memory and the Library

Thematic analysis of the data generated by Library publics indicates that trust, memory, identity, diversity, and place play a role in understanding those who associate with NSW today and what it is they value. Due to space constraints, the findings regarding the role of memory and the Library as instigator of the project are explored here with the other findings being discussed in forthcoming publications.

Photographic portraits of the self, while intimate and personal digital objects, are eagerly exchanged in turn for an opportunity to be remembered and for participating in a project that assembles and shapes public memory. The following two examples are shown with permission from the Instagram post owners and allow for an understanding of how the visual and text components intersect to manifest traces of memory. Other data is discussed in ways that do not easily identify the creators of the post in line with ethical guidelines for social media research (Haimson, Andalibi, & Pater, Citation2016).

Most posts in the data set studied showed traces of participants wanting to be remembered, and of participating in the Library’s project as an avenue for this. is representative of posts that were frequently seen. Here the creator of the post, @miscelleni, speaks to her ‘surprise’ at seeing herself in the projected images of portraits that constituted the project exhibition. These comprised portraits from the Library’s collection and from the public. As we see in her text, @miscelleni’s surprise is due to forgetting that she had posted to the project hashtag and then seeing herself on the gallery wall along with a myriad of historic portraits from the collection when she visited the Library in person. There is a sense of delight and pride of being part of the project and implied here is a positive connection in having her portrait displayed and sitting together with those of others (both famous and not). As such, we gain a sense of the project’s importance to the visitor who owns the Instagram post. The role of the Library here is significant. This is reinforced through the use of two extra hashtags: #statelibrarygalleries and #slnsw indicating that she connects herself to the Library as a place and wants others to know (her followers for example, and those who can access the post via the hashtags) that she is part of something the Library is doing: a project collecting and showcasing the face of NSW. While it is not clear from this simple post whether the visitor is explicitly aware of the collected nature of her portrait and how this will constitute a part of the Library’s archive, and in turn public memory of this moment in time (2018–2019) and what the people of NSW looked like, one can infer this might be the case because her portrait is displayed in an official collected capacity in the Library’s gallery. As such, it is sanctioned by the Library as ‘worthy’ of being collected and shared, and of part of constructing memory of time and place through the project’s aims.

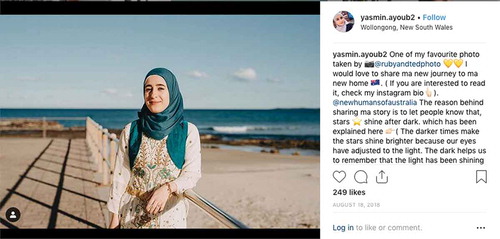

, submitted by @yasmin.ayoub2 is an example of different kind of post to that seen in , but one that was predominant in the data set. That is, it is a direct portrait (not indirect such as the post in ) and it is deeply imbued with identity, place and belonging, themes that were significant findings in this study. It is also reflective of posts that illustrate ways in which being seen, and in association, being remembered, are implied within the visual and text-based components that make up the Instagram post. Here the post’s subject, @yasmin.ayoub2, is sharing a post steeped in place, Australia, and more specifically Wollongong as indicated through the geotag at the top of the post under her Instagram name. However, the text serves to underscore that being in this place (Australia) is significant because it is her ‘new home’ and there is evidence that her journey there has been a difficult one with references to having travelled through ‘darker times’.

Yasmin references another organisation’s Instagram account: @newhumansofaustralia, a site that introduces the faces and stories of new Australians as a way of ‘Celebrating the voices of migrants and refugees who call Australia home’ (@newhumansofaustralia). Visually what we see in @yasmin.ayoub2’s post is a young woman wearing decorative, embroidered clothing and a blue hijab standing near a beach, presumably in Wollongong. Australia’s largest cities are very culturally diverse, so one might not necessarily ‘read’ Yasmin’s visual cues as being of someone who has recently migrated to Australia, yet her post emphasises this point, and importantly this is the portrait she tagged with the #newselfwales project hashtag on Instagram. This indicates that she made a concerted choice to think about how she wanted to represent herself in the project, how she wanted to be remembered, as well as how the idea of Australians at this point in history would be remembered collectively.

In her striking story on @newhumansofaustralia (using the same image as that in ) of moving from Syria to Australia in 2014 as a 16 year-old-girl, Yasmin signs off the post:

‘We feel we belong here.

Yasmin

Syria

Arrived 2014.’

Here we get a strong sense that belonging as Australians is important to Yasmin and her family and by telling this story through her post and the one on @newhumansofaustralia and submitting this information to the Library’s #newselfwales project, she is offering something distinct and important to the way in which public memory of NSW and ‘Australian-ness’ at this time in history might be perceived in the future.

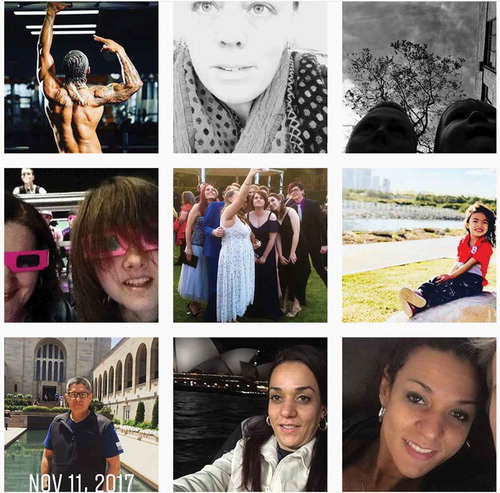

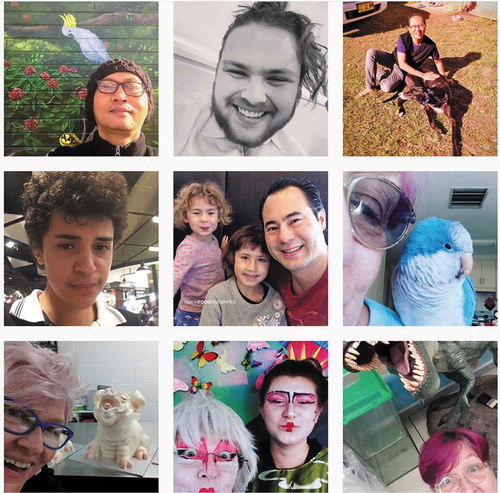

In general, the notion of memory and of being remembered was communicated through the data in a number of ways, including images, hashtags and comments. The faces seen through the portraits are varied in age, gender, cultural diversity, and visual composition, however, all constitute an offering to the project through the use of the hashtag. This suggests that those submitting the posts were aware of the project’s objective – collecting the face of NSW in order to know what it looks like – making sure that their photograph contributes to the construction of this broader image. and are an overview of just 18 images submitted providing examples of how such portraits manifested visually.

Hashtags too were a way for those participating in this project to communicate much about themselves, what they are value, and how being remembered is linked to their contribution. The use of hashtags on social media are powerful connecting devices that enable people to become visible alongside others who are using or searching through hashtags on Instagram. Michele Zappavigna refers to this as ‘ambient affiliation’ (Citation2014, p. 97) whereby imagined audiences are engaged with through a series of sharing and communication practices following the various protocols established in particular online communities allowing for ‘searchable talk’ (p. 100). For example, one young contributor, along with his portrait and name included the following hashtags:

#teenauthor #teenfilmakers #film #bookworm #booknerd #reading #bookblog #bookblogger #bookish #bookaddict #bookstagram #popular #instagood #booknerdigans #instareads #writing #books #bookgram #booklover #publishing #wip #amwriting #pubtip #authors #writers #smashwords #followme #picoftheday

Such hashtags give a strong indication of his values and what he wants to be associated with and remembered by in his contribution to assembling memory of this time in NSW.

Yet another contributor included these hashtags to support her image, which is photographically distorted using a fish eye lens, taken inside the Library near shelves of books: #wackywednesday #humpday #librarylife #statelibrarynsw #NewSelfWales #Australianart #gadigalcountry

Again, like the previous example, we can see what it is that she values and how she wants to be remembered. Significantly, she has used the hashtag #gadigalcountry indicating her recognition of and desire to be connected with the Indigenous peoples of Australia.

Another contributor posted the following hashtags alongside her close-up selfie: #weekend #newselfwales #happy #polishwoman #brunette #wintertime #coffeetime #frozen. Here we see a range of key words that communicate her values and interests in being connected with through memory. For example, the use of #polishwoman suggests her cultural identity is part of how she would like to be remembered. This hashtag has almost three million posts indicating that this contributor wishes to connect with a large community and communicate her decision to post her image to the project hashtag: #newselfwales. Zappavigna reminds us, ‘The essential principle behind a user’s Instagram stream is an ongoing display of self to the ambient audience’ (Citation2016, p. 277) and hashtags enable this through their coordinated distribution capacities (Bruns & Burgess, Citation2011).

Comments were used by many contributors as a way to explain and emphasise something about their portrait and themselves, and often these were interwoven with hashtags highlighting the way communication on social media has evolved to a point where this style of writing – comments-threaded-with-hashtags – has become commonplace. The following examples from a number of posts serve to illustrate how comments transpired:

‘Contributing to the #NewSelfWales wall at the #sydfest Silent Disco #statelibrarynsw #sydfest19 #Sydney’

‘Loved wandering around the exhibitions, installations and projects held during Sydney Festival this week. There are over 20,000 portraits in the State Library’s collection. Each one has its own story and collectively they provide a rich and fascinating history of the people of New South Wales. This exhibition adds contemporary faces to the collection and new portraits are being added as quickly as the present becomes the past.’

‘My Portrait as part of the collection. #statelibrarynsw #statelibrary #portraits #community #history #newselfwales’

‘shared my portrait at the State Library of NSW #newselfwales #photo #history #statelibrarynsw #statelibrary #portraits #community’

‘A life lived in fear is a life half lived.

Introducing the thing I did in 2018 which I feared the most: posing nude for @niqolet_lewis at @nas_au

XXI • The World • 168 × 102 cm’

Through the photographs, hashtags and comments that comprise the posts submitted to the project via Instagram, it is possible to see how identity is deeply embedded in these digital artefacts. The Library, through this project, played a critical role in how this generating of self manifested. Photographic portraits of the self constitute intimate and personal digital objects. However, these objects were eagerly exchanged in turn for an opportunity to be remembered and for participating in a project that assembles and shapes public memory. Such intimate objects share ‘exposed and vulnerable’ components, and as Casey reminds us, this is an important part of understanding how public memory with its ‘medley of voices’ (Citation2004, p. 25) is formed.

Conclusions

This project provided an important intersection between the social and public and through this nexus, memory. Instagram posts, primarily of portraits created by the public, comprise the social activity. These posts created reverberations (being visible, connecting with others) through the social networking capacities that underpin how Instagram and other social media operate. The public component is enacted both in terms of the invitation to participate, the platform on which this occurred (a public and very popular one), but also the role of the Library in collecting, forming, and representing history as the oldest and largest public library in the state of NSW. Thus memory, and especially public memory due to its ability to connect with the past and ensure remembering in the future (Casey, Citation2004), is at its core, what #newselfwales is establishing: a way of thinking about the people of NSW (and indeed Australia) in 2018. The memory of this time is formed through the project and the Library as simultaneously its initiator and gatekeeper (inviter), shaper, collector, repository and memorialiser of this time for future generations. The Library is crucial in this role of public memory shaper because like monuments which work to represent an event (Casey, Citation2004) libraries also work to preserve public memory of a time for future generations. Furthermore, as Casey argues public memory ‘serves as an encircling horizon’ and becomes ‘an active resource on which current discussion and action draw’ (p. 25).

The project #newselfwales embodies (through digital photographic portraits) the people of NSW with windows into who they are, what they value, and how it is they wish to be remembered. Data generated via this project was possible because of the Library’s role as official owner and collector of the outcome. Findings suggest that social photography projects containing intersections of people, libraries and memorialising a moment in time are powerful ways in which library publics can be engaged. Implications include considering the role of memory in the success of similar digital library projects involving crowd-sourced data. The Library’s standing amongst the public, and its perception as an institution imbued with authority suggests that this is why participants so eagerly offered their portraits to the project. Thus, the intersection of the social and public enabled the development of a personal crowd-sourced digital artefact that will help shape public memory of this time and place in history.

Acknowledgments

This research primarily took place on the traditional lands of the Cadigal people of the Eora nation. I acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land and pay my respects to elders past, present and emerging. I would like to acknowledge and thank the State Library of NSW, particularly DX Lab Leader Paula Bray, whose team designed the project #newselfwales which gave rise to this research collaboration. I wish to thank our project research assistant, Dr Helen Benny for her invaluable support and Dr Lachlan MacDowall for his early collaboration. A special thanks to participants who gave permission to include their posts in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kylie Budge

Dr Kylie Budge researches the intersections between people and technology and society. She has an interest in how these connections manifest to produce new knowledge about communication and cultural practices. Kylie is Senior Research Fellow (Urban Living & Society) at Western Sydney University in Sydney, Australia. Previously she worked in the GLAM sector at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney. She has published in a range of journals, books, blogs, and other online media, and is a devoted Instagram user.

References

- Abbott, W., Donaghey, J., Hare, J., & Hopkins, P. (2013). An Instagram is worth a thousand words: An industry panel and audience Q & A. Library Hi Tech News. Retrieved from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/LHTN-08-2013-0047/full/html

- Arias, M. P. (2018, April 18–21). Instagram trends: Visual narratives of embodied experiences at the museum of islamic art. Paper presented at MW18: Museums and the Web 2018, Vancouver.

- Bentley, P. (2009). Putting a value on museums. Museum Matters. Museums Australia NSW. Retrieved from https://www.amaga.org.au/sites/default/files/uploaded-content/field_f_content_file/nswmm1802ma.pdf

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. London, England: Sage.

- Booton, J. (2016). Most Instagram users are outside the U.S. Market Watch. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/most-instagram-users-are-outside-the-us-2016-06-21

- Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011, August 25–27). The use of twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. Paper presented at the 6th European Consortium for Political Research General Conference, Reykjavik. University of Iceland.

- Budge, K. (2017). Objects in focus: Museum visitors and Instagram. Curator: The Museum Journal, 60(1), 67–85.

- Budge, K. (2018a). Visitors in immersive museum spaces and Instagram: The role of self, place-making, and play. The Journal of Public Space, 3(3), 121–138.

- Budge, K. (2018b). Encountering people and place: Museums through the lens of Instagram. Australasian Journal of Popular Culture, 7(1), 107–121.

- Budge, K., & Burness, A. (2018). Museum objects and Instagram: Agency and communication in digital engagement. Continuum, 32(2), 137–150.

- Burness, A. (2016). New ways of looking: Self-representational social photography in museums. In T. Stylianou-Lambert (Ed.), Museums and visitor photography: Redefining the visitor experience (pp. 90–127). Edinburgh and Boston: MuseumsEtc.

- Canty, N. (2012). Social media in libraries: It’s like, complicated. Alexandria: the Journal of National and International Library and Information News, 23(2), 41–54.

- Carah, N. (2014). Curators of databases: Circulating images, managing attention and making value on social media. Media International Australia, 150, 137–142.

- Casey, E. (2004). Public memory in place and time. In K. R. Phillips (Ed.), Framing public memory (pp. 17–44). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Cavanagh, M. F. (2015). Micro-blogging practices in Canadian public libraries: A national snapshot. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 48(3), 247–259.

- Constine, J. (2018). Instagram hits 1 billion monthly users, up from 800M in September. The Crunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2018/06/20/instagram-1-billion-users/

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Davidson, L. (2015). Visitor studies: Towards a culture of reflective practice and critical museology for the visitor-centred museum. In C. McCarthy (Ed.), Museum practice. Volume 4 in the series international handbooks of museum studies (pp. 503–527). Oxford and Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

- Dawson, E., & Jenson, E. (2011). Towards a contextual turn in visitor studies: Evaluating visitor segmentation and identity-related motivations. Visitor Studies, 14(2), 127–140.

- Gerges, M. (2018, May 3). So what if selfies are narcissistic? Canadian Art. Retrieved from https://canadianart.ca/features/so-what-if-art-selfies-are-narcissistic/

- Haimson, O., Andalibi, N., & Pater, J. (2016). Ethical use of visual social media content in research publications. Australasian Human Research Ethics Consultancy Services. Retrieved from https://www.ahrecs.com/uncategorized/ethical-use-visual-social-media-content-research-publications

- Hochman, N., & Manovich, L. (2013). Zooming into an Instagram city: Reading the local through social media. First Monday, 18. Retrieved from https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/%20article/view/4711

- Jones, M., & Harvey, M. (2016). Library 2.0: The effectiveness of social media as a marketing tool for libraries in educational institutions. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(1), 3–19.

- Kastenholz, E., Eusebio, C., & Carneiro, M. (2013). Studying factors influencing repeat visitation of cultural tourists. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 19(4), 343–358.

- Kelly, L. (2018). Exhibitions about people: What appeals to visitors? Museums | Digital | Research Learning. Retrieved https://musdigi.wordpress.com/2018/11/06/exhibitions-about-people-what-appeals-to-visitors/

- Linaker, L. (2018). The importance of tracking and observing visitors in cultural institutions. Museum Whisperings. Retrieved from https://museumwhisperings.blog/2018/02/25/the-importance-of-tracking-and-observing-visitors-in-cultural-institutions/

- Manovich, L. (2014-2016). On broadway [website]. Retrieved from http://manovich.net/index.php/exhibitions/on-broadway

- Neuman, L. (2000). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Pöldaas, M. (2015). Public libraries as a venue for cultural participation in the eyes of the visitors. Media Transformations, 11, 106–122.

- Rose, G. (2012). Visual methodologies (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. (2017). Photographing in the art museum: Visitor attitudes and motivations. Visitor Studies, 20(2), 114–137.

- Suess, A. (2018). Instagram and art gallery visitors: Aesthetic experience, space, sharing and implications for educators. Australian Art Education, 39(1), 107–122.

- Tekulve, N., & Kelly, K. (2013). Worth 1,000 words: Using Instagram to engage library users. Brick and Click Libraries Symposium. Retrieved from https://ecommons.udayton.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1020&context=roesch_fac

- Tifentale, A., & Manovich, L. (2013). Selfiecity: Exploring photography and self-fashioning in social media. Retrieved from http://manovich.net/content/04-projects/086-selfiecity-exploring/selfiecity_chapter.pdf

- Warfield, K. (2014). The treachery and the authenticity of images. TEDxKPU. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jho-2IZ_tnE

- Zappavigna, M. (2014). Ambient affiliation in microblogging: Bonding around the quotidian. Media International Australia, 151(1), 97–103

- Zorloni, A. (2010). Managing performance indicators in visual art museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 25(2), 167–180.

- Zappavigna, M. (2016). Social media photography: Construing subjectivity in Instagram images. Visual Communication, 15(3), 271–292.