ABSTRACT

This paper examines the issue of digital capability at the research team level, specifically their ability to adapt to an uncertain digital future. Within higher education, there is a driving imperative to adapt to the new digital environment not only in areas involved in learning and teaching but also among research teams. While libraries play an important role in developing the digital literacy of researchers as individuals, little attention has been paid to the digital capability of the research team. A review of the literature was undertaken of digital transformation frameworks and models across business, government and higher education. No applicable models or frameworks were found to be suitable for a research team environment. A digital capability model was developed, drawing upon the critical elements discussed in the literature. This model enables library staff to assess the digital capability of the research team, allowing them to not only tailor their services to specific research teams but also driving changes to overall service offerings to better meet the needs of researchers across the organisation. Using this model changes the nature of library staff’s conversation with research team leaders.

Introduction

As Gray and Rumpe (Citation2017, p. 307) suggest, digital transformation (Dx) is an important trend that is enhancing innovation in a wide range of sectors, such as business, government, and academic institutions. While unconvinced that the term has been precisely defined, they observe that it can be deconstructed; implying that many changes in society, business, and industry will be driven by information technologies, which will ultimately lead to changed business models within those sectors. The authors of the current study conclude that models about Dx do not play a prominent role in the current discussion in the research literature about Dx. They attribute the lack of models to the possibility that people researching and applying digital transformation are not aware of the suitability of frameworks and models to facilitate and assess the progress of an organisation in transforming to the new digital environment.

Within higher education, there is a driving imperative to adapt to the new digital environment not only in areas involved in learning and teaching but also among research teams. In this paper, the authors have specifically examined the issue of the digital capability of research teams to adapt to an uncertain digital future. They have undertaken a critical literature review surrounding Dx from several broad areas to identify any suitable models or conceptual frameworks that could be applied to a research team environment. In addition, they have identified the key elements that influence digital capability within research teams and have described how service providers, such as libraries, could use such a model to tailor their service responses to meet specific research team needs.

For the purposes of this paper, the term ‘research team’ is used to describe a group of people working together in a committed way towards a common research goal. It usually is comprised of some key individuals, such as a Principal Investigator, who has the primary responsibility of a study and is usually a senior or experienced researcher. Other members of the team may include co-investigators, data managers, study coordinators, research administrators, statisticians, research support librarians, and research students; each bringing their respective skills and expertise to the team.

From the specific perspective of libraries, while some have staff embedded within faculty/centre research teams and/or research projects, others offer a suite of research support services from within the library. The authors have examined the role of the library in supporting researchers and research teams more explicitly in the literature review.

Literature Review

In examining the literature about Dx, the authors have focused on three main sectors suggested by Gray and Rumpe (Citation2017): business, government, and higher education. The rationale was that these would be the most likely candidates for providing either a model or conceptual framework that could be applied or adapted to a research team environment. In addition, the authors examined the role of information technology departments and the library as two key institutional research support services in higher education in assisting the organisation to address the challenges of Dx.

The literature examined was limited to English language; searches were conducted between November 2018 and October 2019. The authors did not exclude any relevant publications based on format. The initial literature search used Google Scholar and was based on combining ‘digital transformation’ with other keywords such as ‘team’, ‘model’, ‘framework’, and ‘capability’, as well as the names of the relevant sectors. The authors then combined ‘research team’ with other keywords such as ‘digital capability’ and ‘capacity’. The search criterion of publication date was limited to content published since 2010, as the authors concluded that research since that date would produce the latest body of research, given the rapid growth of Dx in the selected categories.

The following sections are not intended to provide an exhaustive analysis of all the publications that the authors reviewed, but rather instead to highlight the key themes that were identified.

Digital Transformation in Business

In 2015, the World Economic Forum (Citation2018) launched its Digital Transformation of Industries (DTI) project, whose primary objective is to analyse the impact of digital technologies on business and society, and to provide insights and tools required for business model changes. In a recent report (Weinelt & Knickrehm, Citation2017), the Forum has observed that surviving in such a rapidly changing environment depends on the ability to re-think every aspect of one’s business. Business, in this sense, means the core activity of the organisation, regardless of the sector to which it belongs. The report identifies four ‘digital’ areas on which to concentrate: business models, operating models, skills, and metrics for success. With regard to operating models, ‘digital leaders follow a lean approach to both core and support functions. With this in mind, 90% of companies have significantly adjusted operations in the past two years’ (Weinelt & Knickrehm, Citation2017, p. 15). Therefore, agility is considered an important element. This is reinforced in the section on work culture.

Fitzgerald, Kruschwitz, Bonnet, and Welch (Citation2014) have examined the need for companies to embrace digital technology as a new strategic imperative. In a survey that elicited responses from 1,559 executives and managers in a wide range of industries, it was found that 63% said the pace of technology change in their organisation was too slow, with ‘lack of urgency’ cited as the major obstacle (p. 2). Companies were measured against an index of digital maturity developed at MIT, which has four main categories: Beginner, Conservative, Fashionista and Digirati (p. 2). An important finding was that ‘Today’s emerging technologies … demand different mindsets and skill sets than previous waves of transformative technology’ (p. 6). Although the digital maturity index developed by Fitzgerald et al. (Citation2014) was too broad to be particularly useful for the authors’ current study, their report mentions several important themes: (1) the need for a well-defined corporate vision; (2) the importance of an improved customer experience; and (3) the need to build the skills of the workforce.

Vey, Fandel-Meyer, Zipp, and Schneider (Citation2017, p. 22) concur that many companies do not yet appreciate the depth of impact which Dx will bring. They attribute this to four main reasons: ‘the striking impact of advanced digitization is not yet fully recognized (1); there is a lack of imagination and strategy, coupled with increasing unpredictability (2); a lack of agility and insufficient encouragement towards innovation (3); and a lack of pertinent competencies and insufficient innovation culture (4)’ (p. 22). In addition, the commitment to digital weakens below the executive leadership level. The researchers advocate the importance of customer experience and the enhancement of workforce capabilities.

Solis (Citation2016, p. 2) has defined Dx as ‘The realignment of, or new investment in technology, business models, and processes to drive new value for customers and employees to effectively compete in an ever-changing digital economy’. He goes on to suggest that although there may not be a ‘universal map’ (p. 2) to guide businesses through proven processes, maturity is based on focusing on six main elements within an organisation: (1) governance and leadership; (2) people and operations; (3) customer experience; (4) data and analytics; (5) technology integration; and (6) digital literacy. A combined analysis of each of these elements helps an organisation to determine at which of the six stages of Solis’ Dx maturity framework it is currently positioned.

In Solis’ Dx maturity model, there is a strong focus on the need to plan within a constantly evolving business environment, based on good governance and leadership. Customer experience is also an important driver. As one of his six key elements, he mentions digital literacy, i.e. the ways in which expertise is introduced into the organisation, which picks up the aforementioned theme of workforce capability. Solis has also highlighted the need for technology integration across the organisation to unite groups, functions and processes so as to provide a holistic customer experience. Within a research organisation, this could be similar to building common technology and data platforms, methods, and processes to unite research teams and provide collaborators with a holistic view of their research goals.

In terms of the current paper, one of the most useful studies within the business domain is that of Henriette, Feki, and Boughzala (Citation2015). In their findings (p. 440), they have identified some of the key areas within a business that tend to be affected by Dx. In regard to business models, this includes reshaping current models, especially because of the impact of the ‘customer value proposition’. While customer relationship is important to transforming operational processes, so, too, are the knowledge and skills of the workforce.

In summary, although the authors did not identify a model or framework within the business sector that could be applied easily to a research team environment, they noted some common themes that were potentially applicable to the current study. These included a very strong focus on the customer, along with not only strong leadership to drive necessary change but also the need to enhance workforce digital capabilities.

Digital Transformation in Government

The European Commission has released several reports that highlight the need for government to work in conjunction with other stakeholders to accelerate the Dx process. The requirement for changes in current policymaking and regulatory frameworks, for example, is a natural consequence of the rapid deployment of new digital technologies (Strategic Policy Forum on Digital Entrepreneurship, Citation2016a, p. 2).

In another report, cities and regions are seen as ‘launch pads’ that can help ‘drive growth and prosperity through digital transformation’ (Strategic Policy Forum on Digital Entrepreneurship, Citation2016b, p. 2). In its recommendations on how cities and regions can be ‘launch pads’ for Dx, the European Commission has introduced a model to accelerate the process. Referred to as a ‘blueprint’, it highlights several key components: leadership to ensure ‘a forward-looking digital strategy and [to] build a shared vision around it’ (p. 2); key technological infrastructure; and transforming the digital skills of the local population. As the authors will discuss later, these elements have useful synergies with the research sector.

In their discussion of the capability of agencies within the US digital government domain to initiate innovation, Cresswell, Pardo, and Canestraro (Citation2006) have described the development of a set of toolkits. Sixteen basic dimensions have formed the basis for the resultant tools (p. 299); these range from business architecture to leadership to resource management to technology knowledge.

The Australian Government, for its part, has taken a leadership role by establishing a Digital Transformation Agency [https://www.dta.gov.au/], with the primary purpose of improving people’s experience of government services by making the latter easier to use. In partnership with the Australian Public Service Commission (Citation2019), the Agency has launched a ‘Building Digital Capability’ initiative, which focuses on ‘developing specialist digital skills, transforming agency culture through leadership, and attracting and retaining digital talent’.

As with the business sector, the authors did not locate an applicable model or framework; however, the government sector echoed some of the same themes: leadership to drive change, focus on the customer (‘people’), and the importance of developing workforce digital skills.

Digital Transformation in Higher Education

According to Parker (Citation2018), the higher education (HE) sector is just beginning a major transformation, of which one of the principal drivers is technology. As a result, institutions are facing challenges arising from digital disruption, specifically the need to rethink structures, processes, and culture (Brown, Reinitz, & Wetzel, Citation2019; Grajek & Reinitz, Citation2019). Weller and Anderson (Citation2013) have proposed a framework for ‘analysing an institution’s ability to adapt to digital challenges’. Based on the concept of resilience, they have incorporated factors such as latitude and resistance to measure the impact of established practice on how adept a system is at absorbing change. They focus on governance (culture) as applied at the institutional level.

Applying an institutional level perspective, PwC (Citation2015, p. 10) champions the need for the modern university to have a ‘digital blueprint’, which will help ensure that thinking digitally will be embedded in all areas of the institution. Similarly, O’Brien (Citation2018, p. 6) has stated, ‘digital transformation is affecting the entire higher education enterprise. Yet evidence from EDUCAUSE research shows that comprehensive approaches to digital transformation are not evenly distributed’.

Although PwC (Citation2015) does not offer a model as such, its blueprint on how universities can leverage new digital capabilities is based on four fundamental premises. These are:

(1) Understand that digital transformation affects every part of the university, not just IT; (2) Link all digital activity to the university’s overall vision and strategy; (3) Invest in communities built around willing and capable digital innovators; and (4) Adopt a design approach that focuses on customer needs, not the university’s internal structure (pp. 7-8).

The need for high-level strategic direction coupled with a customer focus echoes some of the elements previously described for the preceding sectors.

In the UK, Jisc actively works with universities and colleges to ensure that their staff are equipped for a changing digital environment. While the focus is on developing digital capability, the organisational framework developed by Jisc (Citation2017b) examines the main activities that will need attention to lead to digital change across an educational organisation’s core business. The latter are defined as ICT infrastructure; content and information research and innovation; communication; learning, teaching and assessment; and organisational digital culture (p. 1). Of interest to the authors of the current study are the elements used to define the digital capability (‘ICT proficiency’) of higher education staff. They are information data and media literacies; digital creation, problem solving and innovation; digital learning and development; digital communication, collaboration and participation; and digital identity and wellbeing (Jisc, Citation2017a, p. 1).

Reeves and Pearlman (Citation2017, p. 3) have described the importance that EDUCAUSE ascribes to digital capability: ‘Digital capabilities describe the application of technology to the core functions of an enterprise. EDUCAUSE uses maturity and deployment indices to track digital capabilities within higher education. Maturity indices measure the capability to deliver IT services and applications in a given area’. Although their report’s target audience is the institution, the report discusses several aspects that would be equally relevant to research teams: a maturity index based on five categories, which range from ‘absent’ to ‘optimized’, and six dimensions of maturity, of which ‘data efficacy’ and ‘technical infrastructure’ would be particularly relevant.

Digital Transformation in Research Teams

O’Brien (Citation2018, p. 6) makes the point that

Technologies, whether they are related to research, the classroom, or student success initiatives powered by analytics, are not working silently in the background like a water tap waiting to be turned on or an electric switch waiting to be flipped. Rather, these and related technologies are mission-critical strategic assets that determine in many respects how well an institution is able to accomplish its strategic objectives.

According to Galanek and Brooks (Citation2018), with regard to faculty, the current focus of higher education IT tends to be on its role in supporting learning, teaching, and students. As a result, ‘we often pay far too little attention to the role of technology in faculty research’ (p. 3).

That said, a review of the literature worldwide highlights a strong awareness of the need to upskill researchers to work with new tools and methods. For example, Europe would seem to have a comprehensive, high-level perspective on how researchers can best leverage the benefits from Dx. In its report on skills and human resources for e-infrastructures, the European Commission (Citation2012, p. 5) stated:

The aim of e-Infrastructures activity is to achieve by 2020 a single and open digital European research area where researchers can access the expertise, resources and instruments they need online. Every researcher should become digital, know how to benefit from technologies for scientific purposes, use relevant tools for tackling grand challenges of today through computing and data-driven research approaches, and benefit from worldwide connections and collaborations. However, making this a reality for all researchers relies on access and availability of suitable e-Infrastructures as well as on their skills to deploy e-Science approaches. This requires considering the development of necessary human capital base for e-Infrastructures development, service provision and efficient scientific usage.

The Researcher Development Framework, developed by Vitae (Citation2010), is a tool that supports ‘the personal, professional and career development of researchers in higher education’ in the UK (p. 1). ‘Descriptors’ are clustered together under four domains, which are used to identify the characteristics of excellent researchers. While one domain is focused on personal effectiveness, the other three domains are relevant to a discussion on Dx when a ‘digital literacy’ lens is applied to these domains. For example, to engage, influence and have impact, researchers need to have a high level of digital capability, especially if their research objective is to be a leader in their field of research and if the field of research involves big data or advanced information and communications technology (ICT).

In Australia, Luca and Wolski (Citation2013) have developed a Good Practice Framework (GPF) for research training to respond to the Government’s agenda for research training and to promote Australian excellence in research training. One of the drivers for the framework is the requirement of universities to ensure that ‘researchers are being given the required skills to produce new knowledge of world-class quality, which supports and fulfils their careers’ (p. 1). The relatively newly formed Australian Research Data Commons (Citation2019) also provides tools to help researchers improve their digital skills across a wide range of topics.

One of the challenges with the above examples – and similar references – is that the focus is on ‘researchers’, rather than research teams, as a generic category. Another challenge is that there tends to be a focus on digital skills rather than the broader category of digital capability.

One notable exception is the study of research capacity building in Australia by Holden, Pager, Golenko, and Ware (Citation2012), who have created a tool to measure research capacity and culture (RCC) at organisational, team and individual levels. It contains a series of statements relevant to these three domains that ‘respondents rate on a scale of 1–10, with one being lowest skill or success level and 10 being highest possible skill or success level. Items are scored separately for each domain.’ (p. 63). The tool can then be used to evaluate research capacity within the team, the results of which may assist in the development of targeted intervention strategies.

Institutional Research Support Services

In addressing the challenges of Dx, organisations depend on a supportive digital infrastructure to achieve their strategic goals. In the context of this paper, the authors have expanded the concept of infrastructure to include staff expertise, along with the more traditional concepts of networks, systems, hardware and digitally-equipped spaces.

Information Technology

Within Australian universities, service providers, such as ICT units, have been grappling with the problem of how best to provide services to enable researchers to lift their digital capacity and capability (Brennan, Citation2016; Moran & Betbeder-Matibet, Citation2016). Similarly, at the national level, the Federal Government has been focusing on research infrastructure investment in transformative programmes of activities. In its 2015 Status Report on eResearch Capability (Australia. Department of Education and Training, Citation2015), one of the areas for improvement was take-up by the research community and the need for more outreach and relevant training for research groups. The subsequent 2016 National Research Infrastructure Roadmap (Australia. Department of Education and Training, Citation2016) addressed the skills issue but also highlighted the need for collaboration to develop the infrastructure and services required by researchers.

In a recent EDUCAUSE report, Galanek and Brooks (Citation2018) have reported on the results of a 2017 faculty survey of 157 institutions in seven countries. While these institutions generally supported their faculty’s research, there was a need for software and hardware infrastructure and the ability to get real-time, specialised IT support to assist with technology needs (p. 4). Of particular interest to the authors of this paper were the findings from faculty who conduct research at data-intensive institutions. The majority of the latter identified the priority areas of need as adequate bandwidth, data storage, and computational resources. Although Galanek and Brooks do not propose any model or framework, they do provide examples of the survey questions that targeted this cohort (p. 17). These would be useful for developing checklists to assess digital capability of research teams.

In another EDUCAUSE report from the 2018 EDUCAUSE Task Force on Digital Transformation (Citation2018), it was noted that IT leaders have a role to play in helping institutions understand the urgency and potential in developing the required infrastructure and to help institute new research capabilities.

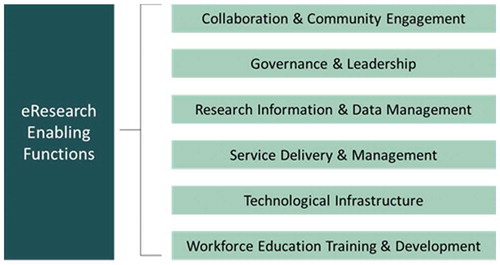

Researchers (Holewa, Wolski, McAvaney, & Dallest, Citation2015) from an Australian research support organisation and three Australian universities have collaborated to produce a maturity model for measuring a research organisation’s progress in implementing university-wide services for researchers and supporting research e-infrastructures. The key elements of the maturity model are summarised in below.

Figure 1. The six dimensions of eResearch enabling functions of the maturity model. Reproduced with permission from authors.

This model can be used to self-assess current service delivery to ascertain where intervention strategies are needed at the whole-of-institution level. This model approaches the digital capability problem from a service provider’s perspective and a number of the functions are similar to those discussed previously for Dx. The recipient of services is generally viewed as being at the discipline level, however, rather than at the research team level.

Library

Academic and research libraries have been actively supporting researchers for many years, which is well documented in the literature. Traditionally, there has tended to be a focus on information behaviour and information literacy. Brewerton (Citation2012, p. 86), for example, used a ‘researcher life cycle’ approach to identify researcher information needs. His study discussed areas of current activity by subject librarians to support researchers, areas of limited engagement, and areas of potential ‘next step’ activity. It also investigated skills sets required for current and future services and highlighted gaps that would need to be addressed both locally and profession-wide. Additionally, Atkinson (Citation2016) has reported on ways in which academic libraries support research in the context of the research lifecycle.

However, more recently library and information science (LIS) literature has focused on the importance of the research data lifecycle, with particular emphasis on aspects such as research data management and data literacy (Federer, Lu, & Joubert, Citation2016; Koltay, Citation2017), and the possible roles for academic and research libraries. Recently, Haddow and Mamtora (Citation2017, p. 89) have reported on ‘research into the extent and nature of research support services at Australian academic libraries, how the services are managed, and the factors that influence their development and delivery’. At a very broad level, Burton, Lyon, Erdmann, and Tijerina (Citation2018) have examined the potential and challenges of successfully implementing data science in libraries.

As part of its strategic direction, the Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL Citation2019) is implementing a ‘Digital Dexterity Framework’. Based on the work done by Jisc as described above, it outlines ‘the skills and capabilities that students will need to succeed in the workforce of the future’ (p1). Libraries, along with other institutional stakeholders, have a key role in helping to build digital dexterity capacity among this cohort. While the framework is targeted at students, the skills and capabilities it describes could also be applied to researchers generally.

Notwithstanding the excellent work being undertaken by libraries, a full review of the relevant literature on their support for researchers is beyond the scope of the current paper. That said, the authors are particularly interested in ways in which librarians specifically support research teams. A common attribute of library research support initiatives/services is that, unlike services from other institutional support elements such as research offices, they tend to be focused on the individual rather than on an actual team, which is a very different perspective. It is not the individual researchers within a project team who deliver on a research unit’s goals, and thereby ultimately the organisation’s strategic goal. Instead, it is the combined work of that research team.

Recognising the importance of this perspective, Rick Luce (Citation2008), in writing about research libraries, has specifically mentioned librarians as part of research teams: ‘Changes in research libraries must be driven by and reflect the needs of the research communities they seek to support … Our responses will require a shift in focus from delivering products (e.g., reference services or publications) to process (e.g., supporting team science).’

In discussing research data management support at UniSA, Morgan, Duffield, and Walkley Hall (Citation2017, p. 300) have noted that ‘the Library frequently initiates conversations with key researchers and research groups about RDM’. Hickson, Poulton, Connor, Richardson, and Wolski (Citation2016) have outlined research support for a small, university social science research centre. Recently, authors (Brown, Wolski, & Richardson, Citation2015; Foutch, Citation2016; Matusiak & Sposito, Citation2017; Shin, Citation2019; Tang & Hu, Citation2019) have discussed examples of librarians participating as members of faculty or centre research projects.

A global research initiative in which librarians are currently playing an important role is that of supporting the adoption of the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID). In an introductory webinar (Brown, Citation2014), ORCID organised a panel of international experts to explore ways in which libraries this initiative. ‘Together, we will explore the ways that libraries can reach out to specific groups of researchers (from graduate students to senior faculty) … ’ An article by Akers, Sarkozy, Wu, and Slyman (Citation2016) has suggested that librarians could promote ORCID by raising awareness not only among researchers and specific groups of researchers but also among university administrators and other research support staff.

Key Themes from Literature Review

As discussed above, common themes from the previous sectors have included: leadership, workforce, customer focus, technology infrastructure, and a whole of organisation approach. Several references have also identified themes particularly relevant to the higher education research environment: technology integration (Solis), innovation (Vey), and culture (Vey).

From a research team perspective, researchers do not work in isolation; research is typically undertaken as a team activity. Given that the identified themes have mainly been drawn from studies of groups, not individuals, they would be applicable in a research team environment. The one major area of difference is ‘customer focus’. Organisations, particularly in business and government, use the customer as the primary focus because the latter are the key to their ongoing success. However, the authors’ premise is that focusing instead on clear research goals, and supporting objectives, is the key to the success of most research organisations.

A Proposed Model of Digital Capability for Research

What appears to be lacking in the literature are Dx frameworks that apply to research teams or that describe the more concrete aspects of building team digital capability. This paper is intended to help fill that gap and therefore proposes a digital capability model specifically for research teams.

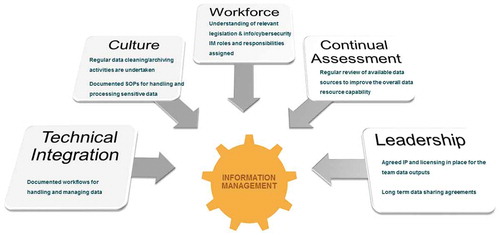

From the literature, the authors have identified five key dimensions for helping to achieve Dx within an organisation: workforce, continual assessment, culture, technical integration, and leadership. A common factor across all the sectors reviewed is the emphasis on the need to build digital capability, with specific reference to the workforce. Other dimensions regularly mentioned in the literature are the need to continually assess progress; a culture supporting innovation and agility; technical integration across the organisation to have a single view of the main focus area (in most cases this was the customer or client); and, finally, appropriate leadership to ensure a forward-looking digital strategy.

In addition, the authors have identified a number of operational capabilities relevant to research teams: governance (Holewa et al., Citation2015), information (data) management (Federer et al., Citation2016; Holewa et al., Citation2015; Koltay, Citation2017; Reeves & Pearlman, Citation2017), technology infrastructure (Galanek & Brooks, Citation2018; Holewa et al., Citation2015), analytical techniques (Reeves & Pearlman, Citation2017; Solis, Citation2016), and process agility (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2014; Solis, Citation2016). Information management, technology infrastructure and governance (i.e. management at the operational level) are common capabilities across all sectors. The level of process agility and analytical capability are specifically relevant to research because of the rapid developments in technologies, data sources and methods.

The level of maturity in these capabilities will determine how well the team responds to changes in the environment. While individuals bring their own set of skills and capability to the team, it is how well the team functions as a unit in a digital environment which will determine the team’s performance.

The authors have used the proposed digital capability model () below to describe these capabilities in more detail. By using the research goal as the central focus, an examination of each of these can provide information about the overarching digital capabilities of the research team. This assessment could be conducted by a service provider or other assessor external to the research team.

Information Management

In this paper, information management (IM) maturity refers to those research team capabilities required for sourcing, managing, and preserving data in a data-intensive research environment. In an age of big data (size and numbers of data sets and the variety of data collected), it is essential that the research team has a sound understanding of information management practices and robust curation processes. Solis (Citation2016, p. 2) has identified data as one of the six main elements to focus on to assess progress through a Dx exercise. Jisc (Citation2017b) has also highlighted information literacies that need to improve within institutions.

Reeves and Pearlman (Citation2017, p.3) have identified six elements which comprise a maturity index for analytics capability at the institutional level. One of these, data efficacy, has relevance to research information management capability within research teams. Maturity in data efficacy may be reflected in the documented policies and processes in place to manage the quality, standardisation, and validity of data and outputs.

When considering how to gauge the maturity of the information management capabilities within the team, the authors propose that evidence of a developing capability is whether the team knows where all research team data is located, along with an understanding of what the data is and the value of each data set.

A second test for identifying developing capability is evidence that the team is addressing compliance and risk issues. The research team should be familiar with all the current and emerging regulatory, legal, and contractual constraints that may have an impact on research activity. For example, in the current international research environment, jurisdiction becomes an issue, as does changing legislation in various partner countries (e.g. European Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)) on their research activities. As an aspirational base line for developing capability, the team should be aware of the regulatory environment and where to go to obtain more expert advice, should it not exist within the team.

Similarly, teams with more mature, established IM capabilities may also have some documented standard operating procedures for handling and storing data, so that all team members follow the same procedures and processes and new staff are being inducted into these procedures.

It is worth noting that none of these capability dimensions exists in isolation. Uplifting the team skills on IM practices will not only provide a more mature understanding of risk and compliance but will also lead to a more data-centric research culture. Addressing compliance requirements and developing risk mitigation strategies should also present opportunities to investigate integrating data workflows and systems as well as taking advantage of institutional and research community ICT infrastructure.

Analytical Techniques

In the current age of cognitive computing and data intensive research, increasing the use of data manipulation tools and code development occurs within research teams. Therefore, it is essential for the team to review the data and analytical techniques used by the team in response to rapid advances in technologies, techniques, new sources of data, etc. Solis (Citation2016, p. 2) has identified analytics as one of the six focus areas to assess progress through a Dx exercise.

Because of rapid advances in digital technologies and practices nationally and internationally, the research team needs to continually review whether the right data is being collected and the right analytical tools are being used to maximise the research outcomes sought. This could involve checking for alternative sources of data, changing data collection methods, locating additional data, and doing regular environmental scans of both the literature and public sites to see if new techniques, analytical tools, and analysis methods are emerging. Given the lag time in publishing articles, participating in research community networks becomes a critical source of information. However, given that new techniques and methods are emerging across disciplines and from social enterprise, industry and commerce, there is a need to look further afield, i.e. beyond the specific research community involved.

Reeves and Pearlman (Citation2017) have identified investment and resourcing as an issue in ensuring that the workforce is prepared not only to do the analysis but also to undertake the relevant support tasks (e.g. data analysts, data librarians/managers). This self-assessment could also be used to ensure the right level of investments and resources are committed in software and IT technology development to support the ongoing scale of research required.

Given both the need for the reproducibility of research and the result of staff turnover within research teams, there is also a need to have mature processes around documenting or having well understood processes in place that can track data from collection through to publishing (and the reverse). This may include the need to document software versions used or instances in which specific code is stored that was used to manipulate data.

Process Agility

Because of rapid changes in technology and emerging sources of new data, it is essential that research teams have not only robust workflows for collecting, processing, analysing, and managing data, but also the capacity to modify or enhance those processes and methods quickly if the case arises to adapt to new opportunities, such as new technologies or data sources.

Solis (Citation2016, p. 2) has identified maturity in operations as another requirement for Dx as well as the use of systematic processes and functions to allow organisations to have a holistic view of an organisation’s, or, in this case, research team’s activities. Increasingly, because of rapid changes in operations, it is important for both the research team leader and each of the team members to have this holistic view to leverage opportunities arising from rapid change.

The literature has also highlighted the need for speed to change technologies. Organisations need to have the ability to respond quickly to new technologies and execute changes. For example, Fitzgerald et al. (Citation2014) highlighted that the majority of the companies they surveyed stated that the pace of technology change in their organisation was too slow. Some companies have tried to address this particular problem in different ways. Monsanto (Swanson & Singla, Citation2018), for instance, has a code marketplace for business and community-led IT development to promote innovation and enhancements from outside the group. In their labs, they promote the use of IT platforms with flexible workflows to accommodate new pipelines.

Evidence of a developing capability of process agility is that processes and infrastructure match the scale of data required to achieve the research goal. It not only has to meet current demand but, given the lag time in developing new infrastructure and software processes, there should also be a plan and process in place to review current capability against future demands.

Technology Infrastructure

Investing in the right technology is critical. However, overinvesting in technologies (as well as the time taken to deploy those technologies) that lock teams into specific methods and processes that are not adaptable to new opportunities and change can be problematic. Several authors (Solis, Citation2016, p. 2; Agarwal, Gao, DesRoches, & Jha, Citation2010) have specifically identified technology integration as one of the critical elements on which to focus when assessing progress through a Dx exercise.

While Solis (Citation2016) has highlighted the need for technology integration to provide a holistic customer experience, the authors suggest that, in the context of a research team, having a holistic view of technology infrastructure (hardware and software) is also essential to unite research teams, functions and processes. This is probably more critical in those research teams where research activity crosses organisational boundaries and national boundaries, and the technology infrastructure is located in various institutions.

The literature has also identified the need for leadership to develop key technological infrastructure. Jisc (Citation2017b) has identified ICT infrastructure as one of the core areas that will need to be addressed by institutions to equip themselves for a digital culture. Reeves and Pearlman (Citation2017) have also singled out technology infrastructure as one of six dimensions for assessing the maturity of the digital capability of institutions. In Australia, as in many other countries, libraries and ICT service providers within institutions, and even the national government, have been addressing the technology infrastructure issue and the uptake by the larger research community (Australia, Department of Education and Training, Citation2016; Holewa et al., Citation2015). Leveraging technology needs to be driven from within the research team and aligned closely with meeting the needs for achieving their research goals.

An example of an established leadership capability in this domain is the existence of an ICT plan to underpin the research plan that reflects:

the right level of infrastructure available to meet research requirements (e.g. digital asset preservation)

access to the right level of computation resources and software tools to process and analyse data

the right level of technology platforms in place to process and manage data with minimal manual intervention

the right level of cybersecurity in place to address risks and compliance

Governance

Vey et al. (Citation2017) have highlighted the importance of good governance by recognising that for organisations to address the impact of Dx, the leaders need to have imagination and put strategies in place to address those impacts and, more importantly, to develop organisational cultures to respond to those impacts. They have noted that in many organisations the commitment to digital weakens below the executive level. Several authors have also observed that leadership alone will not deliver digital transformation, e.g. the need to develop a digital workforce and the key technical infrastructure (Cresswell et al., Citation2006; Strategic Policy Forum on Digital Entrepreneurship, Citation2016b, p. 2). In this paper, the term ‘governance’ is used from the perspective of how governance within the research team is ‘operationalising’ Dx strategies and developing cultural change (e.g. workforce management, planning and monitoring, and resource allocation).

Anne et al. (Citation2017), in their study of measuring digital capacity in the humanities, looked at the four levels of interest in developing and investing digital capabilities: the individual, department, institution and regional/national/consortia. While the current paper is focused on the governance of the research team, the team does not exist in isolation. For example, one measure of an established capability in governance is how well the team is leveraging existing digital technologies and digital capabilities. There may be suitable technologies already in use within its own academic department, within its parent institution, and with external agencies. These existing resources can be leveraged to lift digital capability at the broader level to meet research goals (e.g. storage, servers, joint application development, and training). This includes utilising what is available and seeking out resources for their team (e.g. applying for grants or internal funding, and participating in departmental, institutional, and national planning events). Anne et al. (Citation2017) have also noted the importance of the governance role in seeking out and developing sustainable solutions for systems and infrastructure, which is reflected, for example, in the importance of research team leaders engaging with the different interest groups investing in digital capability within the institution and within the research community.

Discussion

The five operational capabilities in the proposed model cover a range of factors for which a research team needs to ascertain its readiness in responding to a rapidly evolving digital environment. While the model implies that these capabilities are mutually exclusive, there is considerable overlap between them; as progress is made in one capability area, it has a corresponding beneficial impact on other capabilities. For example, as technology adoption increases, so do skills and knowledge in other capability areas.

While this paper refers to a research team as if it were a self-contained entity within an organisation, it is recognised that many research activities cross institutional, national, and (sometimes) international boundaries. Therefore, research teams may have opportunities to develop research partnerships with other teams and to draw upon the mature capabilities of a research partner to complement and support their own team and to bridge any identified gaps. Alternatively, they may be able to draw upon resources already available within their own institution by building relationships with internal service providers, e.g. infrastructure from information technology services or IP/licencing advice from the library and/or institutional lawyers. It is their relationship with the library that is the focus of the current paper.

As mentioned previously, libraries are currently revisiting existing research support services and developing new offerings, e.g. software and data carpentry (Khan & Du, Citation2018); however, these services tend to target either interested researchers in general or within a discipline and are designed to address a designated gap. The authors’ premise is that libraries could use a more holistic approach as the basis for initiating a conversation with a research team as opposed to individuals. The primary objective would be to gauge the level of maturity within the research team and to identify the gaps that need further development for the team to achieve its desired research goals.

For example, using the digital capability model ( above), library staff would focus on ways in which they could help support the five areas of operational capability. An obvious example of an area which aligns very nicely with libraries is information management. The authors have used this capability area to illustrate how to frame a discussion with a research team, which incorporates each of the supporting dimensions ().

Figure 3. Example of assessing information management capability of a research team. Copyright belongs to the authors.

Preparatory Phase

In implementing the model, the authors would suggest that library staff select several research teams from different disciplines, e.g. health and business. By applying the model to different disciplines, library staff can identify not only common requirements but also discipline specific aspects.

Additionally, library staff would document the questions they want to raise with the team leader so as to develop an accurate picture of the team’s capability. Some questions may be common across all disciplines, while some may be discipline specific. The Appendix is a guide to the topics that could form the basis for the questionnaire by providing examples of evaluation indicators as they relate to each of the five transformation dimensions and operational capabilities. These examples allow library staff to tailor the assessment questions to their particular institution. For example, an indicator of maturity in information management may be how well the research team uses institutional services (e.g. supported data management planning tool) or infrastructure (e.g. secure storage).

In the case of information management, for each of the five transformation dimensions in the first column of the Appendix, there is at least one example provided in the third column of a measurable indicator applicable specifically to that capability. (above) is a visual representation of this relationship.

The authors suggest that these questions be forwarded to the research team leader prior to the meeting so that the latter understands the context for the discussion and has adequate time in which to develop a response.

Meeting with Research Team

The format of the actual meeting with the research team will depend on what has been negotiated with the team leader as the best approach. It could range from a meeting with just the team leader or with the whole team in a workshop format. The purpose of this meeting is for the library staff to explore the respective strengths and weaknesses of the team regarding the indicators as identified in the Appendix. The information gathered from this activity will ideally produce a team profile, which can then be used for follow-up activities. How the information is gathered will vary according to the respective research team, considering factors such as culture, location, and availability.

Post Meeting

Having developed an initial team profile, library staff would then identify where they could immediately contribute to developing the research team’s digital capability. For example,

Documentation and team understanding of core data workflows reflecting the use of agreed open standards with loosely coupled processes rather than tight rigid processes with in-house standards. (Culture)

Plans and grant applications addressing processing requirements (Leadership) (also Culture)

Another important activity would be to identify additional gaps where other support service colleagues might contribute their expertise. It is at this point that the degree of the library’s coordination with other key internal service providers comes to the fore in developing a tailored programme to address all identified gaps. Tang and Hu (Citation2019, p. 15) have identified the need for the library to connect with other divisions on campus, working in partnership to extend the value of services to researchers. As a result of collaboration with other service providers, the library will ideally build a more valuable relationship with the research team leader.

Because of the application of the model by library staff to at least two quite different disciplines, it is also important to identify any potential common gaps as well as those that are discipline specific. This will enable better tailoring of services, responses, and resource allocation.In summary, the library’s goal is threefold: (1) develop a detailed capability profile of the research team; (2) identify pain points which the library could help address, and (3) identify pain points which, while not in the library’s domain, could potentially be addressed by partnering with other internal service providers. From the information gathering exercise outlined above, library staff can now draft a programme of work tailored specifically to meet the needs of designated research teams.

Conclusion

An increasingly important goal of research organisations is the need for continuous development and adaptation of digital capacity at the day-to-day operational level. To achieve this, there is a need for an evidence-based tool for service providers to assess the capability and capacity of research team at that level. However, having the staff skills or access to technology alone does not guarantee that a team will adapt to the new fast-moving digital environment.

In this paper, the authors have described the key elements of an evidence-based model of digital capability with capacity-building principles and structured reflection and action. The operational capabilities and dimensions for transformation identified in this paper are useful discussion points to assess a research team’s capability. Institutional support teams, e.g. library staff, can assess their client groups to identify gaps where they can contribute expertise.

While this is a top down evaluation to assess digital capability for transforming research teams, the authors have not discussed the ability to bring about transformational change through the next generation of researchers, e.g. the digital capability of PhD students. Changing the digital capability and culture of a research institution is a complex process; hence, the identified operational capabilities and dimensions should be considered flexible enough to enable changes and adjustment within the local environment.

The major advantage of the proposed digital capability model is that it enables both support service providers and research teams to set their own priorities, control local capability building activities, and evaluate progress in building capability in specific areas from their own perspective and needs.

Assessing their client research team’s capabilities not only allows service providers within institutions to tailor their services to specific research teams but may also drive changes to overall service offerings to better meet the needs of researchers across the organisation. Using this model changes the nature of the conversation with research team leaders.

While this model targets research team digital capability, it is applicable to assessing the capability of other teams within universities. Further research is required to develop a range of questions for a complete assessment checklist.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Malcolm Wolski

Malcolm Wolski is the Director, eResearch Services, at Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. In this role, he oversees the development, management, and delivery of eResearch services to support the University’s research community, which includes the associated information management systems, infrastructure, and data management services. He has particular responsibility for improving research data management practices, infrastructure, and collaborative solutions. Malcolm is a contributor nationally and internationally in the areas of information management and research data support.

Michelle Krahe

Michelle Krahe is a research professional with a passion for development, strategy and innovation in health. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow to the Pro Vice Chancellor (Health) at Griffith University and a Visiting Research Fellow at Gold Coast University Hospital. Michelle has over 12 years’ experience in clinical research, working in academia, health services and research institutes. She was formerly the Research Development Officer at Gold Coast University Hospital and has held senior research general and specialist positions at the Menzies Health Institute Queensland, UNSW (The Kirby Institute), University of Newcastle and the Central Coast Local Health District.

Joanna Richardson

Joanna Richardson is Library Strategy Advisor at Griffith University. Previously she was responsible for scholarly content and discovery services, including repositories, research publications and resource discovery. Joanna has also worked as an Information Technology Librarian in university libraries in both North America and Australia and has been a lecturer in library and information science. Recent publications have been centred on library support for research and research data management frameworks.

References

- Agarwal, R., Gao, G., DesRoches, C., & Jha, A. K. (2010). Research commentary—The digital transformation of healthcare: Current status and the road ahead. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 796–809.

- Akers, K. G., Sarkozy, A., Wu, W., & Slyman, A. (2016). ORCID author identifiers: A primer for librarians. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 35(2), 135–144.

- Anne, K., Carlisle, T., Dombrowski, Q., Glass, E., Gniady, T., Jones, J., … Sipher, J. (2017). Building capacity for digital humanities: A framework for institutional planning. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2017/5/building-capacity-for-digital-humanities-a-framework-for-institutional-planning

- Atkinson, J. (2016). Academic libraries and research support: An overview. In J. Atkinson (Ed.), Quality and the academic library (pp. 135–141). Cambridge, MA: Chandos.

- Australia, Department of Education and Training. (2015). Status report on the NCRIS eResearch capability summary. Canberra, ACT: The Department. Retrieved from https://docs.education.gov.au/node/38205

- Australia, Department of Education and Training. (2016). 2016 National research infrastructure roadmap. Canberra, ACT: The Department. Retrieved from https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/ed16-0269_national_research_infrastructure_roadmap_report_internals_acc.pdf

- Australian Public Service Commission. (2019). Building digital capability. Retrieved from https://www.apsc.gov.au/building-digital-capability

- Australian Research Data Commons. (2019). Audience researchers. Retrieved from https://ardc.edu.au/resource_audience/researchers/

- Brennan, E. (2016). eResearch discussion paper. Retrieved from http://bio.mq.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Macquarie-University-eResearch-Discussion-Paper-January-2016.docx

- Brewerton, A. (2012). Re-skilling for research: Investigating the needs of researchers and how library staff can best support them. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 18(1), 96–110.

- Brown, J. (2014). New webinar: Libraries, researchers and ORCID. Retrieved from https://orcid.org/blog/2014/10/21/new-webinar-libraries-researchers-and-orcid

- Brown, M., Reinitz, B., & Wetzel, K. (2019). Digital transformation signals: Is your institution on the journey? Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2019/10/digital-transformation-signals-is-your-institution-on-the-journey

- Brown, R. A., Wolski, M., & Richardson, J. (2015). Developing new skills for research support librarians. Australian Library Journal, 64(3), 224–234.

- Burton, M., Lyon, L., Erdmann, C., & Tijerina, B. (2018). Shifting to data savvy: The future of data science in libraries. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved from http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/33891/

- Council of Australian University Librarians. (2019). Digital dexterity framework. Retrieved from https://www.caul.edu.au/programs-projects/digital-dexterity/digital-dexterity-framework

- Cresswell, A. M., Pardo, T. A., & Canestraro, D. S. (2006). Digital capability assessment for egovernment: A multi-dimensional approach. In M. Wimmer, H. J. Scholl, Å. Grönlund, & K. Viborg Andersen (Eds.), International conference on electronic government (pp. 293–304). Berlin: Springer.

- EDUCAUSE, 2018 Task Force on Digital Discrimination. (2018). Report. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2018/11/dxtaskforcereport.pdf

- European Commission. (2012). Skills and human resources for e-infrastructures within horizon 2020; report on the consultation workshop. Brussels: Author. Retrieved from https://www.innovationpolicyplatform.org/system/files/European_Commission_2012-Skills%20and%20Human%20Resources%20for%20e-Infrastructures%20within%20Horizon%202020_5.pdf

- Federer, L. M., Lu, Y. L., & Joubert, D. J. (2016). Data literacy training needs of biomedical researchers. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(1), 52–57.

- Fitzgerald, M., Kruschwitz, N., Bonnet, D., & Welch, M. (2014). Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT Sloan Management Review, 55(2), 1–12.

- Foutch, L. J. (2016). A new partner in the process: The role of a librarian on a faculty research team. Collaborative Librarianship, 8(2), 80–83. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol8/iss2/6/

- Galanek, J. D., & Brooks, D. C. (2018). Supporting faculty research with information technology. Research report. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2018/6/supporting-faculty-research-with-information-technology

- Grajek, S., & Reinitz, B. (2019, July 8). Getting ready for digital transformation: Change your culture, workforce, and technology. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2019/7/getting-ready-for-digital-transformation-change-your-culture-workforce-and-technology

- Gray, J., & Rumpe, B. (2017). Models for the digital transformation. Software & Systems Modeling, 16(2), 307–308.

- Haddow, G., & Mamtora, J. (2017). Research support in Australian academic libraries: Services, resources, and relationships. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 23(2–3), 89–109.

- Henriette, E., Feki, M., & Boughzala, I. (2015). The shape of digital transformation: A systematic literature review. In S. Kokolakis, M. Karyda, E. N. Loukis, & Y. Charalabidis (Eds.), Information Systems in a Changing Economy and Society: MCIS 2015 Proceedings(pp. 431–443. Atlanta, GA: Association for Information Systems. Retrieved from https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2015/10/

- Hickson, S., Poulton, K. A., Connor, M., Richardson, J., & Wolski, M. (2016). Modifying researchers’ data management practices: A behavioural framework for library practitioners. FLA Journal, 42(4), 253–265.

- Holden, L., Pager, S., Golenko, X., & Ware, R. S. (2012). Validation of the research capacity and culture (RCC) tool: Measuring RCC at individual, team and organisation levels. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 18(1), 62–67.

- Holewa, H., Wolski, M., McAvaney, C., & Dallest, K. (2015, May). The HWMD maturity model: A foundational framework to measure effectiveness of institutional research e-infrastructures. Paper presented at THETA 2015, Gold Coast, Australia. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/69204

- Jisc. (2017a). Building digital capabilities: The six elements defined. Retrieved from http://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6611/1/JFL0066F_DIGIGAP_MOD_IND_FRAME.PDF

- Jisc. (2017b). Developing digital capability: An organisational framework. Retrieved from http://ji.sc/digicap_org_frame

- Khan, H. R., & Du, Y. (2018, August). What is a data librarian?: A content analysis of job advertisements for data librarians in the United States academic libraries. Paper presented at IFLA 2018, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Retrieved from http://library.ifla.org/2255/1/139-khan-en.pdf

- Koltay, T. (2017). Data literacy for researchers and data librarians. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 49(1), 3–14.

- Luca, J., & Wolski, T. (2013). Higher degree research training excellence: A good practice framework. Perth, Australia: Edith Cowan University. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2013/928/

- Luce, R. E. (2008). A new value equation challenge: The emergence of eResearch and roles for research libraries. In CLIR (Ed.), No brief candle: Reconceiving research libraries for the 21st century (pp. 42–50). Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources. Retrieved from https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub142/luce/

- Matusiak, K. K., & Sposito, F. A. (2017). Types of research data management services: An international perspective. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 754–756.

- Moran, G., & Betbeder-Matibet, L. (2016, March). eResearch at UNSW: Recent developments. Presented at 7th National AERO Forum, Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from http://aero.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/I-UNSW-AeROForum2016.pdf

- Morgan, A., Duffield, N., & Walkley Hall, L. (2017). Research data management support: Sharing our experiences. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 66(3), 299–305.

- O’Brien, J. (2018). Digital transformation and technology narratives. EDUCAUSE Review, 53(2), 4,6. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/~/media/files/articles/2018/3/er182103.pdf

- Parker, S. (2018). Reimagining tertiary education: From binary system to ecosystem. Retrieved from https://home.kpmg/au/en/home/insights/2018/08/reimagining-tertiary-education.html

- PwC. (2015). The 2018 digital university: Staying relevant in the digital age. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.co.uk/assets/pdf/the-2018-digital-university-staying-relevant-in-the-digital-age.pdf

- Reeves, J., & Pearlman, L. (2017). Digital capabilities in higher education, 2016: Analytics. Research report. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2017/9/digital-capabilities-in-higher-education-2016-analytics

- Shin, E. J. (2019). Collaborative research and publishing of librarians and research teams from other academic fields. Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 53(3), 143–159.

- Solis, B. (2016). The six stages of digital transformation. Retrieved from https://www.prophet.com/thinking/2016/04/the-six-stages-of-digital-transformation/

- Strategic Policy Forum on Digital Entrepreneurship. (2016a). A digital compass for decision makers: Toolkit on disruptive technologies, impact and areas for action. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/17924

- Strategic Policy Forum on Digital Entrepreneurship. (2016b). Blueprint for cities and regions as launch pads for digital transformation. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/16762/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

- Swanson, J., & Singla, N. (2018). Inside Monsanto’s digital transformation. Retrieved from https://blogs.oracle.com/datascience/inside-monsantos-digital-transformation

- Tang, R., & Hu, Z. (2019). Providing Research Data Management (RDM) services in libraries: Preparedness, roles, challenges, and training for RDM practice. Data and Information Management, 3(2), 1–18.

- Vey, K., Fandel-Meyer, T., Zipp, J. S., & Schneider, C. (2017). Learning & development in times of digital transformation: Facilitating a culture of change and innovation. International Journal of Advanced Corporate Learning, 10(1), 22–32.

- Vitae. (2010). Vitae researcher development framework. Retrieved from https://www.vitae.ac.uk/vitae-publications/rdf-related/researcher-development-framework-rdf-vitae.pdf

- Weinelt, B., & Knickrehm, M. (2017). Unlocking $100 trillion for business and society from digital transformation. Geneva: World Economic Forum. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/digital-transformation/wp-content/blogs.dir/94/mp/files/pages/files/dti-executive-summary-20180510.pdf

- Weller, M., & Anderson, T. (2013). Digital resilience in higher education. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 16(1), 53–66. Retrieved from http://www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/2013/Weller_Anderson.pdf

- World Economic Forum. (2018). Developing transformation roadmaps for a digital enterprise. Geneva: Author. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/projects/developing-transformation-roadmaps-for-a-digital-enterprise

Appendix

Examples of evaluation indicators as they relate to each of the five transformation dimensions and operational capabilities.