ABSTRACT

The Baillieu Library of the University of Melbourne hosts one of the finest old masters’ print collections in Australia, the equivalent of a state institution or national gallery. Begun with a donation made in 1959 by Dr Orde Poynton, it was enriched in the early sixties thanks to bequests and acquisitions orchestrated by Joseph Burke, Melbourne’s first Herald Chair of Fine Arts, and enhanced by the participation of key figures in the Australian art world. Prompted by new archival discoveries, this paper retraces how the print collection was created, highlighting the acquisitions made in the period 1960–1966. The paper highlights the collection’s teaching function and emphasises how its development was supported by an extraordinary synergy between art historians and local philanthropists.

In the catalogue of his old master’s print collection published in 1666, French connoisseur Michel de Marolles categorised his prints according to the traditional subjects that were taught in schools at the time: grammar, arithmetic, rhetoric, dialectic, music, mathematics, astronomy and physics (de Marolles, Citation1666). Made up of more than 123.000 prints, his collection was purchased in 1667 by Colbert for the Bibliothèque National de France (then Bibliothèque Royal), the first institution to open its print room to scholars. Marolles was the first writer to draw attention on the educational potential of prints. This potential is at the basis of university print collections, an institutional type of collecting predicated on the threefold utility of prints as collecting objects, educational instruments and sources of historical documentation. Little research has been conducted on the history of university print collecting (Griffiths, Citation2016, p. 439). Academic institutions developed gatherings of prints starting from the second half of the seventeenth century, always as a result of public or private donations. In 1653 former alumni Johannes Thysius donated his print collection to the University of Leiden (Mourits, Citation2016). Eight years later, the University of Basel received the collection of the Amerbach family, which was formed in the period 1570–1590 and concentrated on Swiss art of the early Renaissance (Rowlands, Citation1991). Samuel Pepys, Henry Aldrich and George Clarke bequeathed their collections to colleges in Cambridge and Oxford in 1703, 1710 and 1736 respectively. Outside Europe, Frances Grey donated his collection of 3000 engravings to Harvard in 1856 (Cohn, Citation1986). His prints went on to enlarge a bequest of £500 and several boxes of books made almost a century earlier by Thomas Hollis, an ancestor of Dr Orde Poynton, the principal benefactor to the University of Melbourne’s print collection (Anderson, Citation2011, p. 10).

As with many other university print rooms, the University of Melbourne’s print collection was created thanks to an unexpected gift.Footnote1 On 3 December 1958, Vice Chancellor Sir George Paton, received a letter from the British medical doctor Orde Poynton stating his intention to donate his old master’s prints for the benefit of graduates and students. A year later, Poynton donated his entire collection, which contained examples by almost every master printed from the 16th to the 19th centuries, all in the finest condition. Poynton selected the University of Melbourne because of the newly built Baillieu Library, which was inaugurated on 21 March 1959 by Prime Minister Robert Menzies. He was intrigued by the potential of a state-of-the-art facility, and willing to contribute to the oldest Department of Fine Arts in Australia. Celebrated as ‘a gift revolutionary importance in the history of not only our own university library, but of university libraries in Australia’, Poynton’s collection had been developed thanks to a series of acquisitions made in England in the period 1929–1935 and eventually shipped to Australia in 1948 (Burke, Citation1960a). Netherlandish and Italian Old Masters such as Rembrandt, Dürer, Aldegrever, Hollar and Agostino Carracci were widely represented, while a substantial group of minor masters’ works constituted its special feature.Footnote2 The prints were donated with a specific teaching purpose. On 9 April 1960, Poynton wrote:

I am unable to subscribe to the current heresy that the principal function of a university is research. Far more important is to teach and maintain the cultural tradition of our civilisation now in such a dilapidated state. If my library and prints do no more than represent the interest of an English gentleman of 100 years ago, they may be a small contribution to interest students in this tradition. (Poynton, Citation1960).

Poynton imagined his prints used to organise temporary exhibits and envisioned the creation of a print room in the Baillieu Library. The University of Melbourne’s Herald Chair of Fine Arts, Professor Joseph Burke, who felt the obligation to concentrate on adding to the print collection, abandoning the previous plan of building a Fine Arts collection including painting and sculpture, supported his vision.Footnote3 Burke was aware of the importance of prints for teaching purposes, an issue particularly relevant to Australia, were early modern works were often unavailable. In 1959, the 337 undergraduate and 3 postgraduate students of the Department of Fine Arts attended seminars at the National Gallery of Victoria, where an old master’s print collection had been assembled since 1891–1892 with prints purchased at the famous Seymour Haden sale in London (Burke, Citation1960a). Poynton’s donation allowed students to work in proximity to the library, creating benefits for both teaching and research.

As noted by deputy librarian G.J. Macfarlan, the prints were stored in Solander boxes purchased from the firm of G.W. Gilbert in London and placed on steel shelving mounted in the newly built print room, which was located on the second floor of the Baillieu Library, adjacent to the Fine Arts Library (Macfarlan, Citation1961). The print room was open for students, staff and visitors to the university, who were given the opportunity to examine many fine impressions, some of which were missing from the collection in the National Gallery of Victoria. A scheme for the cataloguing and classification of the print collection was drawn up in September 1961 following the advice of Dr Ursula Hoff, the Keeper of Prints at the National Gallery. It was decided that the prints would be arranged first by the nationality of the engraver and then by period. Each engraver was given a Cutter number and works were arranged either chronologically or numerically. In some cases, parallel arrangements were made since different size prints by the same artist were stored in different size boxes. In these cases, an additional symbol was incorporated into the call number to indicate the size of the storage box.

Having been donated with the hope that ‘in the longer run someone else might leave the university a similar collection’, Poynton’s prints became the impetus for an extraordinary season of bequests and new acquisition (Poynton, Citation1960). Made in the quinquennium 1961–1966, they were orchestrated by Professor Burke and supported by an exceptional synergy between art historians and local philanthropists, namely the Lindsay family and the Society of Collectors.

Appointed as Herald Chair of Fine Arts on 25 March 1946, Joseph Burke was an authority on the British art of the eighteenth century (Anderson, Citation2005) (). Born in 1913, he was educated at the Benedictine school, Worth Abbey, in West Sussex before electing to study Fine Arts at the newly created Courtauld Institute at the University of London. Described by Lord Kenneth Clark as ‘a good scholar with a wide range of interests’, Burke greatly appreciated works on paper and especially those by Hogarth (Clark, Citation1946).Footnote4 Shortly after his arrival in Melbourne, he founded the Society of Collectors, a sophisticated group of fifty members whose aim was to promote collecting in Australia and to help the University to build up a Fine Arts collection. The Society of Collectors was inspired to the Society of Dilettanti, founded in London in 1734 by a group of British men who had returned from the Grand Tour, and had discovered the collecting of antiquities and indulged in the patronage of neoclassical artists (Anderson, Citation2005, p. 91). Burke brilliantly transposed the idea of a society concerned with historical and contemporary collecting to an Australian context, assembling a group of collectors including Australia Prime Minister Robert Menzies, newspaper proprietor Sir Kenneth Murdoch, the Director of the National Gallery of Victoria Daryl Lindsay, the Chairman of the Trustees of the Adelaide Art Gallery Sir Edward Morgan, Colonel Aubrey Gibson, philanthropist Kenneth Myer and the University of Melbourne’s Vice-Chancellor Sir George Paton.

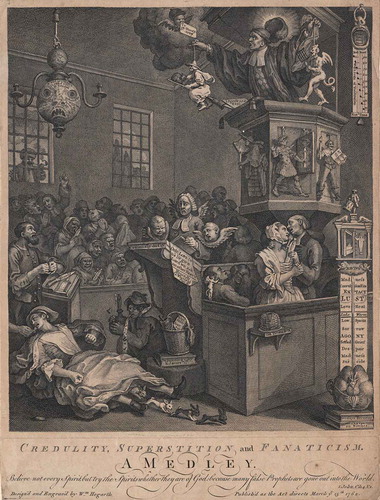

The Society of Collectors’ philanthropic effort was essential for the development of the Baillieu library print collection. In February 1961, the society’s president Aubrey Gibson committed to raise funds in order of £500 per annum and authorised the purchase of a small group of early Hogarth prints, as well as the acquisition of 2500 British illustrations of the period 1770–1830, including 400 by Stothard (Burke, Citation1961a). The prints were ordered from David Low Booksellers (Chinnor, Oxfordshire) a shop highly recommended by Poynton. Hogarth’s prints included illustrations from Hudibras, Don Quixote and Cassandra, as well as the engraved Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism, a Medley (). The remaining images were cut out of periodicals and purchased with the purpose of favouring Blake studies at the University of Melbourne. To this end, Professor Burke noted: ‘they are certainly not collectors’ pieces, but will be useful for Blake studies, because they show the work of the main illustrators of his period (Burke, Citation1961b). The acquisition enlarged the already substantial holdings of Hogarth’s prints donated to the Baillieu library by Poynton and laid significant foundations for the university to develop as a centre of Hogarth scholarship.Footnote5 The prints also represented a resource for the field of eighteenth-century studies. This was particularly relevant to Australia’s own narratives, being the period in which the European settlement first took place.

Figure 2. William Hogarth, Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism, a Medley, engraving, 1762, 46.3 × 33 cm. Special Collections, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

On 3 October 1961, Joseph Burke left Melbourne to spend one month as Commonwealth Visitor at the University of London. He arrived in England on November 12 and elected to remain in London for further three months to conduct research for the eighteenth-century volume he was writing for the Oxford History of English Art (Burke, Citation1961d). Although his commitments included three lectures to be delivered at the Courtauld Institute as well as visits to Oxford and Paris, he devoted part of his time to the development of the University of Melbourne’s print collection. With respect to this, in December 1961, he asked Sir Anthony Blunt to organise a seminar aimed at discussing the future of the Baillieu library collection (Burke, Citation1962a). Held at the Courtauld Institute, the seminar saw the participation of twelve world-renowned scholars including Ernst Gombrich, John White and the Librarian of the Warburg Institute Otto Kurz, and highlighted the opportunity for new acquisitions, especially in the areas of lesser known engravers and reproductive prints. Specifically, the panel suggested that the university library purchase those large systematic collections often overlooked by Print Departments in Museums, which were generally interested in creating comprehensive collections of the great masters and selecting only representative collections of the minor figures.Footnote6

It was in the immediate aftermath of this seminar that, while making enquiries to art dealers, Burke was informed by Colnaghi’s director Sir James Byam Shaw about nine volumes of Sadeler family’s engravings that were once part of the print collection of Elizabeth Seymour Percy (1716–1776), Duchess of Northumberland, one of the pre-eminent female collectors in 18th century England (Lo Conte, Citation2018). The volumes represented one of the world’s largest gatherings of images by members of the Sadeler family, the most successful of the dynasties of Flemish engravers that were dominant in Northern European printmaking in the later 16th and 17th centuries (). Fitting precisely with the advice received from the Courtauld seminar, the collection was presented to Burke in late December 1961, as shown in a letter Burke received on 4 January 1962 from Colnaghi’s representative A.H. Driver. Driver’s letter highlights the exceptional nature of the Sadeler collection, which is ‘unusually extensive’ and ‘more complete than that of the British Museum’ (Driver, Citation1962). Moreover, it mentions that the volumes were once part of the Print Library at Syon House, where they were purchased by Colnaghi’s on 11 April 1951.Footnote7 Valued at £600, the collection included ‘nine volumes containing about 1200 prints by the Sadeler family and other engravers of the late sixteenth century, some after their own designs, but mostly after Flemish, German and Italian artists of the period, especially Marten de Vos’ (Driver, Citation1962). It also encompassed a number of duplicates, which were an integral part of the original conditions of the volumes.

Figure 3. Aegidius II Sadeler after Paul Bril, Mountain Landscape with Hermit, engraving, 19.0 × 26.6 cm. (plate); vol. IV Raphael Part Second, Rare Books, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

Bearing in mind the teaching function envisaged for the print collection, it is evident how this opportunity unexpectedly arising on the London art market stimulated Burke’s interest, persuading him to purchase the volumes. After his return to Melbourne in March 1962, he contacted Aubrey Gibson to ask for the support of the Society of Collectors. Burke noted:

While making enquiries in London, one important collection did turn up and seemed to fit perfectly with the advice I had been given. This is a collection of sixteenth century engravings. There are 1200 prints in all, so that the price per print is very cheap. Because the reproductive ones are after Flemish, German and Italian artists of the sixteenth century, they would fit admirably with the special emphasis that our teaching places on this period and would give us for the first time a starting point for original research by postgraduate students. (Burke, Citation1962a).

Gibson personally undertook to raise the sum needed amongst the members of the Society of Collectors (Burke, Citation1962b). By 12 April 1962, £485 had been raised, while a further £100 was added by Orde Poynton with the specific purpose of purchasing the duplicates (Poynton, Citation1962).

The nine volumes purchased by the Society of Collectors offer an exceptional overview of the Sadeler family’s artistic activity, whose contribution to the history of printmaking is highlighted by a plethora of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sources (Baldinucci Citation1686, pp. 26–27; Le Comte, Citation1700, pp. 144–157; Von Sandrart, Citation1675, p. 355). Their acquisition highlights the atmosphere of enthusiastic collaboration surrounding the development of the university print collection, as well as Burke’s ability to develop contacts with prestigious institutions such as the Courtauld and the Warburg Institutes in London. Thanks to the generosity of the Society of Collectors, the university acquired an invaluable resource for students of the late Renaissance and Baroque art, as the Sadelers’ prints were essential for the transmission of stylistic models between northern and southern Europe. To this end, their prints after Renaissance painters allowed Flemish and Netherlandish artists to become familiar with the pictorial novelties developed in Italy during the second half of the sixteenth century. Similarly, their impressions after Flemish artists introduced in Italy the pictorial language developed by in Central and Northern Europe (Pellegrini, Citation1992).

Alongside Orde Poynton and the Society of Collectors, a key benefactor to the university print collection was Peter Lindsay, the son of the late Sir Lionel Lindsay, who donated from his father’s collection. Lionel was one of Australia’s finest artists and a personal friend of many members of the Society of Collectors (Mendelssohn, Citation1988). He was particularly close with Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who thought of him being ‘worth his weight in gold, because of his enlightenment and conversation’ (Menzies, Citation1961). Developed from 1927, the Lindsay print collection had been progressively enlarged from the mid-thirties, when its owner was appointed as a trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. It included works by Rembrandt, Dürer and Piranesi, a complete set of Turner’s Liber Studiorum (1807–1819) and Callot’s Miseries of war (1633). Furthermore, it encompassed prints by nineteenth-century British and American artists, and twentieth century impressions by Norman and Lionel Lindsay (Lindsay, Citation1961b). On 13 July 1961, Peter Lindsay bequeathed to the university an almost complete selection of his father’s bookplates, fine wood engravings made for personalities Lionel knew and admired (Lindsay, Citation1961a). Three months later, he gifted ten of Lionel Lindsay’s etchings and drypoints, providing the university library with works by Australia’s most accomplished printmaker (Lindsay, Citation1961c).Footnote8

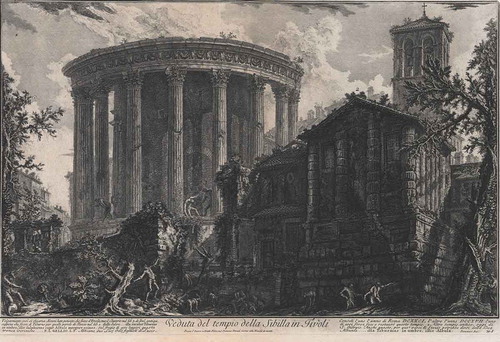

Aside from donating original prints by his father, Peter Lindsay conceded to the Fine Arts Department the first offer on the purchase of old masters prints from the Lindsay collection (Lindsay, Citation1961a). To avoid duplicating items already in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Burke invited Ursula Hoff, the gallery’s keeper of prints, to travel to Sydney at the university’s expenses and make recommendations about prints to be added at the Poynton collection (Burke, Citation1961c). Born in London and growing up in Hamburg, Hoff was an authority on early modern prints (Palmer, Citation2008). Since 1947, she had joined the teaching staff of the Fine Arts Department at the University of Melbourne, lecturing part-time and reinforcing her teaching by conducting seminars in the print room at the National Gallery of Victoria. On 22 November 1961, Hoff made her suggestions for purchasing from the Lindsay collection (Hoff, Citation1961). Her list included forty-five impressions dating from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. The prints were categorised in three main teaching areas. The first group focused on prints from the German Renaissance; the second included seventeenth century reproductive engravings; the third covered works from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and included five large etchings from Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Vedute di Roma (). Valued at £235, the impressions were paid thanks to a Capital Equipment Fund for Research approved in 1961 by the Australian Universities Commissions. The fund consisted of a £2000 Triennium Grant, of which £500 was to be spent of the university print collection (Cumming, Citation1962).

Figure 4. Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Sybil Temple at Tivoli, etching, 1780–1785, 42.6 × 61.1 cm. Special Collections, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

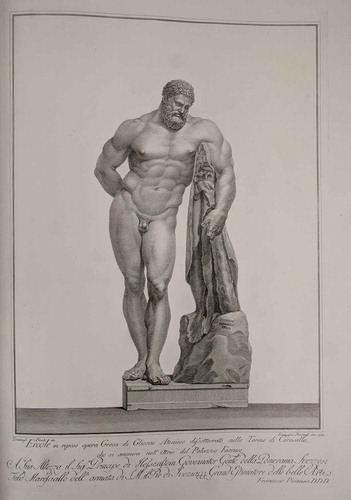

In the following months, Hoff continued to visit the Lindsay’s residence to add both to the National Gallery and the university collections. On 14 November 1962, she suggested the acquisition of a large volume of ancient statues by Francesco Piranesi (1758–1810), Giovanni Battista’s son (). Hoff’s suggestion came with a handwritten note:

The description of the book is very vague. I take it to be Choix de Meilleures Statues Antiques, Rome 1769. It should contain 42 plates, consecutively numbered 822 to 863. If complete and the plates are good impressions the price is certainly reasonable (Hoff, Citation1962).

Figure 5. Francesco Piranesi, Farnese Hercules. In Choix de Meilleures Statues Antiques. Rare Books, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

Comprising 40 copperplate engravings, the volume was purchased for £20 with funds from the Society of Collectors and arrived safely in Melbourne on 14 March 1963 (Burke, Citation1963). Since then, it was lost, before being located thanks to information provided by this research.Footnote9 Although heavily damaged, the grey cartoon boards have preserved the large plates, which are in a good state. As recognised by Hoff, the album corresponds indeed to Choix de Meilleures Statues Antiques, a collection of 41 classical statues engraved in the period 1780–1792, and eventually published by Tessier as volume number 28 of the second Paris edition of Piranesi’s works. An indication on the album’s provenance is provided by the bookplate, which includes the coat of arms of Lord Reay as well as elements of the arms of the Mackay clan (Bangor-Jones, Citation2000, pp. 35–99). The name of Alexander George Mackay, alongside with the Latin motto manu forti, demonstrates that the volume was once in the collection of the 8th Lord of Reay, who in 1805 took part in the capture of Cape Town. Even though the heavily damaged status of the boards makes it difficult to identify the edition, the volume was certainly purchased in Italy since pencil notations indicating the price for each print are noted using scudi and baiocchi: the major coins circulating in Rome until 1865. Reproducing the most influential statues from classical antiquity, the volume was the first Piranesi album to ever enter the Baillieu collection, preceding by more than a decade the acquisition of the almost completed first Paris edition of Piranesi’s works, once in the collection of Melbourne’s first catholic bishop, James Alipius Goold, purchased by the university between April 1974 and December 1975 with funds from the Ivy May Pendlebury bequest (Holden, Citation2014, pp. 161–166).

In 1963 the Baillieu library print collection was further enhanced by the bequest of the English connoisseur and dealer Harold Wright, whose gift of prints focused on the work of Lionel Lindsay and his British contemporaries William Palmer Robins and Stuart Brown. Wright was a director of Colnaghi’s and an internationally renowned print-seller and connoisseur (Maskill, Citation2009). Throughout his career he knew and fostered many printmakers, this was reflected in his personal collection, the majority of which was sold in 1962 at Sotheby’s London (Maskill, Citation2009, p. 102). The component of the Wright collection gifted to the university of Melbourne comprised 1153 prints. The collection had been waiting in the British Museum for its assessment and acquisition. The Museum’s policy of the day was not to acquire the oeuvre of contemporary artists, but to focus on refining acquisitions of the great masters. As a result, the British Museum chose to retain only six drawings, returning the rest of the collection to Wright’s wife, Isobel, who suggested that the prints should be divided between the University of Melbourne and the National Gallery of New Zealand. The sequence of events is narrated by Burke:

In a recent letter she [Isobel] has referred to a very generous proposal that she mentioned to me in England, namely, her intention to present the collection of Lionel Lindsay’s work that Wright formed to suitable institutions. The British Museum has taken some, but the bulk is still intact. Because her husband has friendship with New Zealand and Daryl Lindsay in this country, she suggested that the collection might be divided between Melbourne and Wellington (Burke, Citation1962c).

The prints were shipped in October 1962 via the British Museum to the University of Melbourne, where they were divided between the Baillieu library and the National Gallery of New Zealand (now Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa) (Bell, Citation1962). Through the Wright bequest, the Baillieu acquired the largest collection of Lionel Lindsay’s works of any university in Australia. The collection had a remarkable teaching potential. In this regard, Stone has recently noted that the strength of Wright’s collection was the ability to visually illustrate to students the changes that occur to the plate in different states, as many prints evolve through multiple working impressions (Stone, Citation2019, p. 7).

The teaching function envisioned by Joseph Burke and Orde Poynton for the Baillieu library print collection has shaped the study of art history at the University of Melbourne. The size of the collection and its standing as a teaching resource were reaffirmed in 1966 by the offer of a significant group of reproductive engravings of old masters from the National Gallery of Victoria. Suggested by Ursula Hoff, the loan was organised with the purpose of making ‘the collection available for demonstration to students of fine art’. It included about 1,500 items, most of which nineteenth century engravings reproducing paintings from the Renaissance. As Burke noted, the prints reproduced pictures that were either lost or known to have been destroyed, thus constituting an undoubted resource for both students and researchers (Inglis & Wilson, Citation2011, p. 103). In September 1978, the university appointed the first curator of prints, Geoffrey Down, a graduate of the Melbourne’s Fine Arts Department. The curator’s duties included (i) the organisation and cataloguing of the Baillieu print collection; (ii) the conservation and preservation of the material in the collection; (iii) making the collection available to scholars and students as a research and teaching resource; (iv) mounting exhibitions in the Baillieu library print room (Inglis & Wilson, Citation2011, pp. 116–118). By the end of 1979, an undergraduate subject was added to the curriculum in Fine Arts. Entitled ‘Studies in Prints’, it was taught by Down in the print room and introduced honours art history students to the European tradition of printmaking from the 15th to the 20th centuries. Students could request prints be displayed, although access to the works was always supervised. The prints were presented in mounts and placed on tables or on stands where they could be scrutinised or placed alongside other examples for minute comparison.

The enthusiasm for print studies informed the research of many scholars within the Fine Arts Department and prompted the creation of a formal internship that helped students to take up supervised cataloguing and research projects in the print room. With the print room closing in 1996, requests to view material in the collection were made through the Special Collections Reading Room. In response to this situation, the recently appointed Herald Chair of Fine Arts Professor Jaynie Anderson sought funding to develop a suite of ‘online subjects’ that would draw upon and, indeed, celebrate the quality and teaching potential of the collection. Anderson was awarded a Talmet Grant to develop the ‘Virtual Print Room’, a project that took print studies ‘out of the rarefied world of the conventional print room and placed it at the forefront of modern technology’ (Anderson, Citation2011, p. 8). The ‘Virtual Print Room’ helped the library to digitise their collection and introduced Melbourne’s postgraduates to pioneering studies in the history of printmaking. Not only the subject imparted knowledge of printmaking history, techniques and print curatorship, but also allowed students to familiarise with the methods and processes involved in staging a public exhibition in a gallery space.

In the past decade, the teaching function of the university collection has been enhanced even more by innovative approaches to teaching such as object-based learning, a mode of education that involves the active integration of authentic or replica material objects into the learning environment (Jamieson, Citation2017). To this end, under the impulse of current Herald Chair of Fine Arts, Professor Anne Dunlop, classes dedicated to the study of old master’s prints are regularly organised in the Leigh Scott Room of the Baillieu library to support the teaching of the Art History Department. Furthermore, the new Arts West building, inaugurated in 2016, has dedicated object-based learning laboratories in order to create a learning environment where skills are imparted through practical experience and exploration.Footnote10 The laboratories allow students to work with the university’s collections in new and exciting ways, enriching their learning experiences.

The synergy between art historians and philanthropists that characterised the development of the university print collection testifies to an understanding of the essential role played by prints in the study and practice of art history. In this regard, the use of innovative technologies and teaching methods serve the purpose of ideas already developed in the eighteenth century. In the appendix dedicated to the usefulness and use of prints attached to the 1752 translation of Boutet’s Traité de la peinture in mignature, the author states: ‘by means of prints, one may easily see the works of several masters on a table, one may form an idea of them, judge by comparing them with another […] and by practicing it often, contract a habit for good taste and good manner, especially if this is done in the company of anybody that had discernment in these things and can distinguish what is good, from what but is indifferent’. (Boutet, Citation1752, p. 148). For seventy years, the Baillieu Library print collection has provided staff and students with the rare privilege of working closely with remarkable works of art. The extraordinary season of acquisitions and bequests that allowed for its creation shaped the teaching of art history in Australia’s oldest Department of Fine Arts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Angelo Lo Conte

Angelo Lo Conte is Assistant Professor at the Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University. He has been the recipient of postdoctoral research fellowships at the Rosand Library and Study Centre Venice (2018); the Ian Potter Museum, Melbourne (2017); the Australian Institute of Art History, University of Melbourne, Melbourne (2016).

Notes

1. ‘Print room’ is a term widely used by art historians and print curators to identify a room within a museum or a library hosting a collection of old master’s prints.

2. The collection is available online at https://library.unimelb.edu.au/collections/special-collections.

3. ‘It was originally planned to try and form a small University Fine Arts collection including painting [..] this project should be abandoned, and we should concentrate entirely on building up the print collection’ (Burke, Citation1960b).

4. Burke’s lifelong interest in Hogarth is demonstrated in his research and writing. His editing in 1955 of Hogarth’s aesthetic treatise The Analysis of Beauty (1753) established him as one of the foremost Hogarth scholars of the twentieth century.

5. For a well-reasoned account of Hogarth prints in the Baillieu Library, see James (Citation1998). James states that the Baillieu holds over 50 Hogarth prints that have no acquisition. Those correspond to the group purchased in 1961 thanks to the generosity of the Society of Collectors.

6. ‘Such collections do not in fact appear very often and are reasonably inexpensive because few print departments are thinking on these lines. Their aim is comprehensive collections of the great masters and select but representative collections of the minor figures’ (Burke, Citation1962a).

7. The ‘Print Library from Syon House’ was sold at Sotheby’s London on 11 April 1951. The Melbourne volumes are identifiable with Lots 315 (Sadeler: the works of Sadeler family, after M. De Vos, some by De Passe and others, 3 vol.) and 316 (J. Sadeler: a very extensive collection of his works, mounted in eight volumes). Sotheby’s London, Catalogue of fine engravings and etchings, 10–11 April 1951, 37.

8. Lindsay’s prints included: A street balcony, Guadalupe; Basque Houses, San Sebastian; Old Saumur; Trinity, Melbourne University; The Little Pool, Yarra, Melbourne; Latrobe Street, Courtyard; St. Patrick’s, Melbourne; Snowy River; Drafting; The Return.

9. Catalogue number 760.0442 PIRA Shelf 120.

10. Information on the object-based learning laboratories is available online at https://arts.unimelb.edu.au/articulation/editions/2016-editions/december-2016/object-based-learning-a-new-mode-in-arts-west.

References

- Anderson, J. (2005). Interrogating Joe Burke and his legacy. Melbourne Art Journal, 8, 88–101.

- Anderson, J. (2011). Orde Poynton and the Baillieu Library. In K. Stone (Ed.), Print matters at the Baillieu (pp. 7–20). Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne.

- Baldinucci, F. (1686). Cominciamento e progresso dell’arte dell’intagliare in rame [Origin and progress in the art of copper engraving]. Florence: P. Matini.

- Bangor-Jones, M. (2000). From clanship to crofting: Land ownership, economy and the church in the province of Strathnaver. In J. Baldwin (Ed.), The province of Strathnaver (pp. 35–99). Edinburgh: Scottish Society for Northern Studies.

- Bell, H. (1962, October 24). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 120, University of Melbourne.

- Boutet, C. (1752). The art of printing in miniature. London: Hodges and Cooper.

- Burke, J. (1960a, March 29). Letter to Orde Poynton. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1960b, October 3). Letter to Orde Poynton. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1961a, February 21). Letter to Orde Poynton. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1961b, April 20). Letter to Orde Poynton. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1961c, September 15). Letter to Peter Lindsay. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1961d, September 30). Letter to the secretary of the London Library. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0039, 35, 16/11, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1962a, March 29). Letter to Aubrey Gibson. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1962b, April 12). Letter to R. A. Cumming. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1962c, July 5). Letter to John Ilott. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 120, University of Melbourne.

- Burke, J. (1963, March 14). Letter to Peter Lindsay. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Clark, K. (1946, March 3). Letter to John Medley. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 2000.0126, University of Melbourne.

- Cohn, M. B. (1986). Francis Calley Gray and art collecting for America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museum.

- Cumming, R. A. (1962, February 1). Letter to Franz Phillip. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- de Marolles, M. (1666). Catalogue de livres d’estampes et de figures en taille douce: Avec un dénombrement des pieces qui y sont contenuës. Fait à Paris en l’année 1666 [Catalogue of the printed books and old master’s prints: With the enumeration of the artworks included]. Paris: Frederic Leonard.

- Driver, A. H. (1962, January 4). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Griffiths, A. (2016). The print before photography: An introduction to European printmaking 1550-1820. London: The British Museum.

- Hoff, U. (1961, November 22). Letter to Franz Philip. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Hoff, U. (1962, November 14). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Holden, C. (2014). Piranesi grandest tour. Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing.

- Inglis, A., & Wilson, M. (2011). Prints at the Baillieu Library: Teaching and learning from the collection. In K. Stone (Ed.), Print Matters at the Baillieu (pp. 103–113). Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne.

- James, K. (1998). Hogarth in the Baillieu: Precedents and projections (Unpublished master’s thesis). The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC.

- Jamieson, A. (2017). Object-based learning. A new way of teaching in Arts West. University of Melbourne Collections, 20, 13–14.

- Le Comte, F. (1700). Cabinet des singularités d’architecture, peinture, et gravure [Cabinet of architectural, pictorial and engraving peculiarities]. Paris: Le Clerc.

- Lindsay, P. (1961a, July 13). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Lindsay, P. (1961b, August 7). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Lindsay, P. (1961c, October 19). Letter to Mr Course. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Lo Conte, A. (2018). How one global collection of Old Master prints was created: Nine albums by the Sadeler family in the Baillieu Library of the University of Melbourne. Journal of the History of Collections, 30(2), 339–350.

- Macfarlan, G. J. (1961, September 5). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 120, University of Melbourne.

- Maskill, D. (2009). Imperial lines: Harold Wright (1885-1961): Printmaking and collecting at the end of the empire. Melbourne Art Journal, 11/12, 86–103.

- Mendelssohn, J. (1988). Lionel Lindsay: An artist and his family. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Menzies, R. (1961, September 11). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 122, University of Melbourne.

- Mourits, E. (2016). Een kamer gevuld met de mooiste boeken: De bibliotheek van Johannes Thysius (1622-1653) [A room filled with the most beautiful books: The library of Johannes Thysius (1622-1653)] (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Leiden, Leiden.

- Palmer, P. (2008). Centre of the periphery: Three European art historians in Melbourne. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

- Pellegrini, F. (1992). I Sadeler a Venezia [The Sadeler in Venice]. In C. L. Virdis (Ed.), Una dinastia di Incisori: I Sadeler (pp. 5–10). Padua: Programma cop.

- Poynton, O. (1960, April 9). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Poynton, O. (1962, April 7). Letter to Joseph Burke. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Archives, 1986.0037, 10, 119, University of Melbourne.

- Rowlands, J. (1991). A Swiss cabinet of wonders: The Amerbach-Kabinett in Basel. Apollo, 134(353), 58–60.

- Stone, K. (2019). Horizon lines: The ambition of a print collection. In K. Stone (Ed.), Horizon lines: Marking 50 years of print scholarship (pp. 3–23). Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne Library.

- Von Sandrart, J. (1675). L’Academia todesca della architettura, scultura e pittura [The German academy of architecture, sculpture and painting]. Nuremberg: Nürnberg Sandrart.