ABSTRACT

Managing change is documented as a critical issue for all organisations. Due to its complexity, a clear understanding of how university libraries can meet this challenge is yet to emerge. As libraries experience significant disruption as a result of technological development driving change, this qualitative research study advances a conceptual framework, based on relevant existing literature, for performance improvement. The research identified resources, relevance, stakeholders, strategy, government policy, and university infrastructure as contributing elements to effectively manage change in Australian public sector university libraries. This paper builds on this analysis to identify a shift in Australian university library management style and construct frameworks that may address challenges of change for these organisations.

Introduction

Organisational change is one of the most frequently studied topics within organisational management and subjected to considerable research and discussion. Change occurring in the twenty-first century has a character and speed that is without precedent (Burnes, Citation2004; Dobbs, Manyika, & Woetzel, Citation2015; Viardot, Citation2017). Significant changes are induced by the interplay of globalisation, capital, trade, labour mobility and information technology during the past four decades (Durrani & Smallwood, Citation2008; World Economic Forum, Citation2018, Citation2019). Artificial intelligence (AI) will change even more job roles through profound developments in automation, computers, research, and service delivery. AI in this fourth industrial revolution (4IR) will unsettle jobs and lives disproportionally in an era where no analogous industrial revolution precedent exits (Chalmers in Adams; Citation2017, Williams in O’Neill, Citation2017). These changes are significantly and continuously influencing higher education (CAUL, Citation2014; Davis, Citation2013; Manning, Citation2018). It has become critical for university libraries to effectively adapt to change and remain relevant to learning in universities (Harland, Stewart, & Bruce, Citation2017; Koz, Citation2014; MOU, Citation2016). The library needs to restructure it functions, services and accessibility to resources to add value to university business in an environment of increased exposure to market forces and competition (Harland et al., Citation2017; Koz, Citation2014; MOU, Citation2016).

Forces for Change impacting on Australian university libraries

Although some changes are induced by forces such as advancing technologies, globalisation and changing needs of higher education combine to induce transformation in university libraries worldwide, different issues impact more on libraries in diverse regions of the world based on a wide variety of socio-economic conditions (Afebende et al., Citation2016). For example, in the US internationalisation of education is the leading force for driving change in academic libraries (Click, Wiley, & Houlihan, Citation2017). Similarly, in African countries, the major challenge is chronic financial constraints and inadequate infrastructure (Jain & Akakandelwa, Citation2016). The literature shows four key factors that impact on the Australian higher education sector with a consequential effect on Australian university libraries.

The first factor is the declining government funding of Australian universities. Government funding to Australian universities has gradually decreased from a full contribution in 1974 to 40.1 per cent in 2002 (ABS, Citation2004), and by approximately a further 33 per cent reduction by 2007 (Guthrie & Neumann, Citation2007). A further cut of 20 per cent was imposed in 2016 (Carrington, O’Donnell, & Rao, Citation2016; Conifer, Citation2016) with an additional A$2.2 billion fiscal reduction in 2017/2018 (Karp, Citation2018). These severe reductions in public spending have resulted in Australian universities receiving amongst the lowest level of public investment in higher education among industrial economies (Carrington et al., Citation2016; Conifer, Citation2016) at 30th out of OECD countries (Universities Australia, Citation2017). The curtailments of public funding have provided much of the impetus for profound changes in university libraries such as reduced staff numbers and trimmed or refined collection development policies (University of Tasmania Library, Citation2016; Wood, Miller, & Knapp, Citation2007).

The second factor is the rapid advancement in information and communication technologies (ICT). The Internet has had a decisive impact on information sharing, conversation, and collaboration, causing far-reaching changes in higher education as well as in its libraries (Baker, Citation2014aa; Sorgo, Bartol, Dolnicar, & Podgornik, Citation2017). The Internet also underpins major changes in university libraries in access brokerage, privacy, global access, collection management, space planning, information delivery, and library use (Anderson, Citation2015; Baker, Citation2014; Brabazon, Citation2016; Gibbons, Citation2007; Uzwyshyn, Smith, Coulter, Stevens, & Hyland, Citation2013).

The third factor library leaders need to consider in response to change is the diversity of the student population. The student population can range from baby boomers to millennials, or the ‘Net’ generation, with vastly different characteristics in each generation (Gregory, Citation2015; Oblinger, Citation2003). A significant element of the changing student population in universities includes an increasing number of time-poor students who juggle studies with either family life or work or both (Gregory, Citation2015; Oblinger, Citation2003; Popp, Citation2012). Millennials use computers and the Internet extensively: physical, as opposed to virtual access, is shunned (Gregory, Citation2015; Lippincott, Citation2005; Oblinger & Oblinger, Citation2005) to communicate and study, shop and socialise online, and therefore spend fewer hours in the library (Oakley & Vaughan, Citation2007). Consequently, millennials expect library services that reflect the capabilities of the most current websites (Gregory, Citation2015; Lippincott, Citation2005; Oakley & Vaughan, Citation2007). They relish the ease of using the library collection and databases and save their time by enabling instant, seamless and complete access to information from any locality 24 hours, seven days per week (Islam, Mok, Xiuxiu, & Leng, Citation2018; Popp, Citation2012).

The fourth factor are the extensive changes in the methods of university teaching, learning and research. Students are no longer required to be ‘on campus’ to access materials or attend classes. The advancement of ICT facilitates the emphasis on life-long learning, problem-based learning, student-centred learning, online teaching, learning and research, and the convenient delivery of learning material in multiple modes (Duderstadt, Citation2009; Goodman, Melkers, & Pallais, Citation2019; Jamieson, Citation2013; Tangney, Citation2014).

Changing role of the university library

Until the late 20th Century, the library was considered the centre of the campus and deemed to be an essential part of university life, a place that all students, academics and researchers had to visit for their information needs (Darnton, Citation2008). It was, and remains, the responsibility of the library to acquire and curate information resources required for university teaching, learning and research (Darnton, Citation2008). Due to the impact of the array of factors that induce change, swift changes are occurring in the university environment resulting in the purpose and expectations of a university library being changed comprehensively (Bostick & Irwin, Citation2014; Darnton, Citation2008; Sandhu, Citation2015). The continued relevance of the library as part of the university structure as well as the need for its adaptation to changing times is well documented (ALIA, Citation2014; Johnson et al., Citation2015). Today, due to the dominance of digital publishing coupled with digitisation of existing library print collections, libraries break previous physical barriers and have opened digital collections to all (Anderson, Citation2015; Duderstadt, Citation2009).

Furthermore, the transition of higher education from an instruction-centred to a learning-centred paradigm displays a need for appreciating varying students’ requirements in the context of learning styles. Refocussing on students’ scholastic needs has resulted in the academic library becoming a proactive partner in the learning process rather than just a space that assists with the provision of resources (Choy & Goh, Citation2016): this is a key example of change. The provision of learning spaces and other facilities for group teaching/learning has resulted in the university library becoming a hub for collaborative learning, social engagement, and creativity which promotes social constructivist learning (Childs, Matthews, & Walton, Citation2013; Jamieson, Citation2013; Sandhu, Citation2015).

Due to advances in ICT, and to cater to the changing nature of their clients, academic library collection development policies have changed from ownership to access. Digital information resources are the dominant formats of the Internet age (Levine-Clark, Citation2014; Pan & Howard, Citation2010). Rather than owning e-resources, university libraries subscribe to individual e-resources and packages and provide access to a wide range of free information through the Internet (McRobbie, Citation2003; Rossmann & Arlitsch, Citation2015). This shift has resulted in electronic resources that do not occupy the same amount of space as physical resources (Johnson, Citation2016; O’Connor & O’Connor, Citation2007). The move to electronic resources has meant that students no longer need to visit the physical library (Johnson, Citation2016)

The change in usage of library spaces has resulted in the sense of the library existing beyond physical walls (Baker, Citation2014; O’Connor & O’Connor, Citation2007), dramatically changing the function of the modern university library (Johnson et al., 2015; Sinikara, Citation2013). The library was once seen as a repository of knowledge in the form of hardcopy resources that were systematically stored for students and academics to retrieve the necessary information and as a place of silent information seeking and intellectual reflection (Darnton, Citation2008). Today, the library fosters discussion to create collective wisdom by providing appropriate collaborative spaces for student-centred learning (Bieraugel & Neill, Citation2017; Bostick & Irwin, Citation2014; Jamieson, Citation2013; Watkins & Kuglitsch, Citation2015; Wells, Citation2014). Such informal learning depends on a wide range of physical environments such as specific spaces for group study and discussion, and meeting spaces within the library or the university campus facilitating interaction, stimulation, self-services, and collaboration in cyberspace, as well as reflection/quiet study spaces and the remaining physical collections (Childs, Matthews, & Walton, Citation2013b; Jamieson, Citation2013; Kranich, Lotts, & Springs, Citation2014; Wainwright, Citation2005).

The Australian federal government played the prime funding role for universities from the 1940 s (Emmanuel & Reekie, Citation2004). This altered: from the turn of the century, significant changes in Australian higher education policies have resulted in the gradual but increasing withdrawal of government funding to a partially subsidised system with costs shared by the Government and student fees (ABS, Citation2004; Conifer, Citation2016). As a result, Australian universities have been compelled to generate finance from sources, including the demand-driven domestic and international student market, which have resulted in higher education institutions implementing operating practices more closely aligned with business principles (Kemp & Norton, Citation2014; Oakley & Vaughan, Citation2007). This change of management practices within Australian universities has resulted in passing on fiscal pressure to cost centres (Emmanuel & Reekie, Citation2004; Oakley & Vaughan, Citation2007), including libraries, and other student support structures thus placing them under scrutiny related to need, relevance, or value creation.

Managing change

Successfully managing change involves careful management of how stakeholders associate with the organisation to foster synergistic relationships underpinned by purpose (Freeman, Citation2005; Harrison & Wicks, Citation2013; Watson, Wilson, Smart, & Macdonald, Citation2018). According to Freeman (Citation2005), achieving healthy stakeholder relationships requires attention to four conditions: being mindful of the impact of one’s actions on others, as well as their possible effects; being mindful of stakeholder behaviours, values, backgrounds, social contexts, and the issues that management stands for; understanding stakeholder relationships; and balancing stakeholder interests over time. As implied, these four conditions aim to add worth to satisfy the interests of both private and public sector organisations (Harrison & Wicks, Citation2013). A study of university library change management suggests that the leading cause of failure of most change efforts is the lack of a thorough investigation of stakeholder needs (Koz, Citation2014) signalling the significance of the sustainable value for stakeholders in university libraries (e.g. students, staff and senior university management) in managing change effectively.

The literature also suggests the significance of strategic planning to manage change and sustain the relevance of an organisation (Kilkelly, Citation2014) by assisting leaders in thinking, learning and acting purposefully (Bryson, Citation2011). Strategic planning addresses issues such as aims and objectives, course of action, the resources necessary for achieving goals and objectives, while understanding an organisation’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (Graetz, Rimmer, Lawrence, & Smith, Citation2006). The effective implementation of strategic plans, including competent performance measurement, is critical as the inefficient execution of a plan will lead to mediocre performance (Lamberg, Tikkanen, Nokelainen, & Suur-Inkeroinen, Citation2009; Saver, Citation2015). Therefore, strategic planning has been a widely used method for managing change in university libraries as better client-oriented outcomes have been achieved (Michalak, Citation2012; Williamson, Citation2008). University libraries have been implementing existing or in-house strategic planning methods with a high level of competence and skill to achieve improved performance and traction with the clientele but with no wide acclaim or recognition within the sector (Parker, Citation1997; Percival, Citation2015; Pinfield, Cox, & Rutter, Citation2019).

Aims of the research

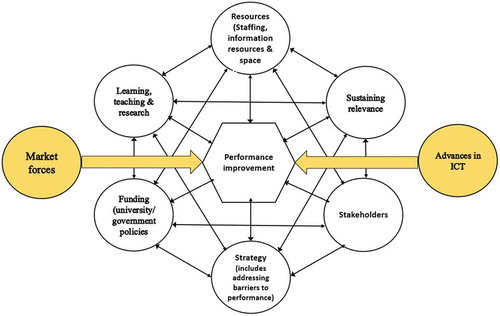

This research aimed to gain an insight into, and new knowledge of the complexities of managing change in Australian university libraries by investigating current change management practices of the chief librarians in Australian University Libraries (AULs) as they approach these issues. The conceptual framework to guide this research () included six fundamentals of performance improvements which emerged from existing related literature: resources, relevance, stakeholders, strategy, funding, and learning/teaching/research. The concept ‘Resource’ also includes physical library buildings associated with space planning, modifications to collections and other associated developments. As : -Conceptual framework – below shows, all six fundamentals are interconnected as well as performance improvement of the organisation. The original version of the conceptual framework first appeared in the PhD thesis of Gunapala (Citation2017). Based on later research by Pinfield et al. (Citation2019), the improved framework shows the inter-relationships between the fundamentals with added clarity.

This research followed the qualitative constructivist approach. The Primary data collection was captured through interviewing chief university librarians of 18 universities out of the 37 public universities in Australia. The selected universities were from all states of Australia except Tasmania and the Northern Territory. The interviews were face-to-face using a semi-structured questioning approach based on themes and concepts derived from the literature review. The interviews were conducted until data saturation began to surface in the twelfth interviewee. Though the interviews were in 2014, the data collected remains valid as the change process continues rapidly. Observation data was also gathered to a lesser extent through visiting Australian academic libraries and gaining insights into elements such as the attractiveness of the library building, space facilities available, and print collection areas of the library. Library reports/plans/policies were accessed through the web pages of AULs and provided additional primary data about library management. Information from journal articles, books, websites and reports have been integrated into the research as secondary data. The data analysis was conducted thematically using a Microsoft Excel matrix. A second matrix recorded commentary from literature based on relevant themes and concepts in circumstances where the observations of the informants aligned. The sub-sections below are devoted to data analysis and discuss the findings of the research (see Gunapala [PhD thesis], Citation2017),

Impact of government funding policy on university libraries

From the literature (secondary data) funding cuts to higher education are having an impact on services, teaching and research and have had an increased impact since 2006 (Barneveld & Chiu, Citation2018). In 2007 as the Rudd government came to power federally, Australia’s ‘public expenditure on higher education had fallen to be amongst the lowest of any OECD nation. In fact, during the Howard [government] years, the level of public funding per student declined by an astounding 30%’ (Crittenden, Citation2009). There was a hiatus, albeit brief, from May 2009 to 30 June 2013 when the Australian government allocated an essential 5.7 USD billion increase of funding to higher education (HE) (Australian Government Treasury, Citation2009).

Sixteen of the 18 informants and library reports (primary data) acknowledged the adverse effect of the rapid decrease in public funding for AULs (University of New South Wales Library, Citation2015; University of Tasmania Library, Citation2011; Victoria University Library, Citation2012, Citation2015). One informant stated that the library funding in 2014 (i.e. during the interview for primary data collection) remained unchanged from the 2008 level in dollar terms. Another informant was concerned about the library’s future due to continual funding decline. However, the repercussions of declining public funding in AULs were not uniform. For example, one AUL was not affected by declining funds because of the investment strategies of the university. For another, having adequate support from the senior university management was a deciding factor in remaining unaffected by the declining public funding for universities. All informants agreed that good relationships with the senior university management (which includes finance officers and the heads of the academic community, such as deans, program managers and pro-vice chancellors) were essential to obtain the necessary funding to function appropriately. The informants overwhelmingly agreed that the way to achieve their budgets was to make senior and influential university staff aware of the library’s value to the university’s strategic goals of supporting learning, teaching and research. Two informants expressed that the senior university management viewed the library and other non-academic areas of the university as the easiest targets for funding cuts as public funding declines, particularly by enacting staff redundancies. Two informants who were not affected by declining public funding to universities claimed that their libraries remained as the centres of education in their universities. There were two significant reasons attributed by numerous informants to maintaining a budget to fund and support the primary functions of the library. Firstly, eight informants believed that wealthy universities could operate well within an environment of declining public funding due to established multiple income sources. Secondly, if senior management considered the library an essential part of the university in delivering tertiary education, library budgets were maintained. Therefore, this research finds two necessary requisites for receiving adequate funding for the library: making the senior university management understand and appreciate the value of library for the university; and the ability of library leadership to maximise the return on investment.

Library collection and space

There appear to be two main changes relating to library information resources. As the Rubin (Citation2017) stated along with all the informants, electronic materials have become the dominant format of library information resources. They consume more than half of the library information resource budget (Rubin, 2017). Four informants stated that they were spending about 80 per cent of their materials budget on electronic resources. In 2015 ALIA predicted an 80 per cent e-book collection in libraries freeing up space for other student services but requiring budget growth as the move to e-resources resembles a runaway train if not a bullet train (Harvey, Citation2015). The second change was the ‘just-in-time’ collection development policy. Pre-1990 s, the library was viewed by management as a storehouse and a gatekeeper to knowledge (Darnton, Citation2008; Johnson et al., Citation2015). The library was the centre of university education, acquiring information (in printed format) on a just-in-case basis to support current and future information needs of students and academics (Chang & Bright, Citation2012; Lugg, Citation2011). As the literature and all informants indicated, libraries were essentially transaction-oriented (acquiring, processing, and circulating information resources) which may be described as transaction-oriented management (TOM). Post-1990 s, the university library collections development policy was transformed due to advancing ICT (e.g. transition from print to electronic publications, the Internet and the Web), competing pressures for library space, the high cost of print book retention and management, and the convenience of electronic publications for archival and virtual access (Baker, Citation2014; O’Connor & O’Connor, Citation2007). ‘Just-in-case’ has changed to a ‘just-in-time’ policy to address changing needs of the library and its clients leading to a demand-driven strategy using advances in ICT and facilitating instant online access to resources (Lugg, Citation2011; Swords, Citation2011). Sixteen (out of 18) informants mentioned this change in collection development policy in their libraries reflecting the 80/20 ratio predicted by ALIA in 2015 (Harvey, Citation2015).

All informants acknowledged the introduction of off-site storage (Wright, Jilovsky, & Anderson, Citation2012), or more recently, on-site automated storage and retrieval systems (ASRCs) (Burton & Kattau, Citation2013) as strategies to store less-used print books in libraries economically. Two informants outlined the benefits of their ASRCs for quick retrieval of print books allowing for more collaborative study spaces. The researcher’s visits to libraries also revealed the limited use of floor space for print collections in AULs. New AULs were eager to implement a preferred electronic policy, discarding their existing duplicate print collections. Five informants from more established university libraries indicated that their libraries persevered their extensive print collections, and therefore had comparatively more library spaces allocated for bookshelves for print materials which were rarely used by library clients.

Collaborative study spaces in libraries emerged primarily to meet the needs of changing students’ learning approaches induced by increased access to resources through the Internet (Bostick & Irwin, Citation2014; MOU, Citation2015); and ever-changing university teaching and learning strategies through the use of online platforms (Chan, Citation2014; Gensler, Citation2014). The library space is both virtual and physical. This trend has also resulted in declining service points such as reference/information and circulation desks which once were the norm (Abbasi, Elkadi, Horn, & Owen, Citation2012; Bostick & Irwin, Citation2014), and witnessed by the researcher’s library visits.

Maintaining relevance

A prevailing view among numerous experts is that libraries need to remain relevant to the key clientele i.e. students, with library spaces supported by technology, a more relaxed social atmosphere, and relaxed library rules (Bostick & Irwin, Citation2014; Johnson et al., Citation2015). All informants also acknowledged this issue. Library spaces now consist of various facilities such as rooms for students practising presentations, restaurants, resting places (e.g. sleep pods), learning labs, gaming labs, general meeting spaces and ‘makerspaces,’ (Australian National University (ANU), Citation2015; University of Technology Sydney Library (Citation2014, Citation2016)), and even spaces for therapy dogs to help students relax (Sessoms, Citation2014; Victoria University Library, Citation2016a). A library ‘makerspace’ is an area and/or service that provides library patrons opportunities to engage. Students can create intellectual and physical materials using a range of resources such as computers, editing tools 3-D printers, and traditional arts and crafts pursuits. Some newer universities were successful in obtaining funding for new buildings for modern libraries. There was a common understanding that libraries are useful as cultural centres or hubs that encourage collaboration for learning and creativity (Head, Citation2016; Shapiro, Citation2016). One informant revealed that many library staff still retain the belief that the physical library space is critical despite the increasing significance of the future of the library in the online/virtual environment. A significant finding based on the interviews was that changing the physical space-bound mindset of library staff was considered critical for the university and its library to remain relevant in the future.

Attempts by Australian universities to transform library spaces as learning and meeting places were successful to varying degrees. Some libraries have buildings of historical value. Two informants mentioned the expensive and less successful nature of renovating such premises to the present-day needs. One informant saw the significance of a satisfactory location of the library as important to attract students as well as academics to the library. For another informant, it was the inspiring building as well as the attractive and well-located library canteen that boosted the attendance of students and academics to their library. Spaces for collaborative learning and socialising in the library were considered by all participants to represent the future form of the library. The researcher observed areas in some of the old library buildings that would be complicated and expensive to renovate for present-day needs despite some reading rooms having little use at the time. Established universities viewed these legacies as a problem in swiftly adapting to the changing university library environment.

Transformation of human resources in AULs is surging ahead on several fronts. Universities in Australia have resorted to staff reduction strategies in the wake of declining public funding. The gravity of the staff cuts was largely identical for 16 libraries with two of the informants declaring that their libraries followed the strategy of postponing new recruitment for positions that fell vacant. For those libraries which were financially solvent, the practice was two-pronged: not to reduce staff positions but not to recruit any new staff despite formal positions becoming available. The library reports of AULs (East, Citation2010; Victoria University Library, Citation2006, Citation2014) revealed that the reduction of staff in AULs was one of the natural ways of meeting the challenges of declining public funding. The libraries addressed related challenges of maintaining or improving the operating efficiency by adopting new technologies and methods like the acquisition of electronic materials, introducing self-service in many areas like circulation, and remodelling cataloguing, acquisitions and reference services. The literature indicates the beginning of the transformation of these processes from about the 1990 s, with libraries relying on advancing ICT as well as better management practices to stay relevant (Marcum, Citation2016; Partridge et al., Citation2011; Sharda, Citation2016).

Effective use of knowledge and skills by all stakeholders in universities – and wider society – increases the efficiency and the desired outcomes achievable in an institution (Fleming, Coffman, & Harter, Citation2005; Raju, Citation2014; Wiseman & McKeown, Citation2010). A study by Corrall (Citation2010) found a diminishing significance in librarianship but the crucial need to acknowledge the increasing significance of information and communication technology (ICT) and other discipline knowledge to be necessary skills for effectively managing university libraries. While reaffirming this blended academic librarian model, this research further elaborated the critical nature of knowledge in ICT, business and management, and disciplinary knowledge over traditional qualifications in librarianship when recruiting librarians for universities. Two informants interviewed for this research did not possess librarianship educational qualifications but did graduate from ICT bachelor courses. While all informants of this study emphasised the changing nature of skills required for AULs, one informant also noted the importance of creating a satisfactory staff culture within the institution for effective management.

Many informants cited unattractive employment conditions as well as unhealthy (less) turnover of staff as barriers to attracting staff with required new knowledge and skills. Therefore, as many informants affirmed, they used one or more recruitment methods such as targeted recruitment, salary matching, rovers, studentships, and graduate traineeships to attract such new knowledge and skills to their libraries. Academic commentary from Blackman (Citation2006), Chow (Citation2014) and the World Economic Forum (World Economic Forum, Citation2016), as well as all informants, acknowledged the merits and importance of staff development methods, such as staff rotation, specialist skill training, encouraging research, innovation and empowerment through learning from what others do, attending conferences, plus scope to hold higher positions temporarily, to develop new knowledge and skills in existing staff. However, many informants expressed the difficulty of allocating enough funding for staff development due to drastically declining funding to their libraries. All informants declared the need for the review of existing library and information science curricula to provide necessary new knowledge for AULs, although it is impractical to provide all required knowledge (i.e. IT, business and management, and disciplinary knowledge in addition to librarianship) in a library and information studies (LIS) curriculum. Eight informants emphasised the advantage of making LIS courses postgraduate, as opposed to undergraduate, and including an understanding of the future challenges of academic libraries.

Meeting stakeholder needs

Satisfying stakeholder needs is critical for organisational performance (Freeman, Wicks & Parmar, Citation2004; Provasnek, Sentic, & Schmid, Citation2017), including university libraries (Booth, McDonald, & Tiffen, Citation2010; Gray & Barker, Citation2015), and was reported as such in all AUL annual reports. Based on this research, an engagement-oriented management (EOM) approach to satisfy the needs of stakeholders such as clients, staff and senior university management is considered optimal (Gunapala, Citation2017). Many informants of this research thought that their students demand a satisfactory service since they pay for their education. All informants, AUL annual reports, and the literature (Bell, Citation2014; Mitchell, Citation2008) acknowledged libraries support of students and academic staff through the provision of facilities such as e-resources, collaborative study spaces and support (including technology-mediated) for diverse teaching, learning and research (e.g. face-to-face and online, and backing for blended learning and MOOCs). All AULs reported their efforts to engage with senior university management to bid for and secure funding, and to align themselves with university business goals by economical use of funds allocated to improve performance based on stakeholder expectations.

As they adapt to disrupting change, university libraries have embraced non-traditional responsibilities in areas where they have the expertise (Grabowski et al., Citation2016), to provide value-adding services to stakeholders. All the informants elaborated on non-traditional responsibilities adopted, which included university publishing, managing research repositories and research databases, collaborating with academics in supporting curriculum preparation, and the use of e-resources in online learning management systems (Blackboard, Canvas and Moodle) to aid lectures and tutorials.

As discussed above, numerous significant shifts occurred in library management over the last few decades due to forces of ICT driven change. Those shifts are: from a centre of the campus to another cost centre of the university; from a collection-centred to a client-centred library; from supporting information needs of clients to supporting teaching, learning and research, and performing non-traditional responsibilities; attraction of clients to the library as opposed to the necessity of visiting as in a bygone era; diminishing significance of knowledge of librarianship, and increasing importance of knowledge or expertise in business and management, ICT, and disciplinary knowledge; change from just-in-case collection development policy to demand-driven policy; from the significance of a purely physical library to a physical and virtual library; and transaction-oriented management (TOM) to an engagement-oriented management (EOM) (Dale, Beard, & Holland, Citation2016; Gunapala, Citation2017).

Re-examination of the conceptual framework

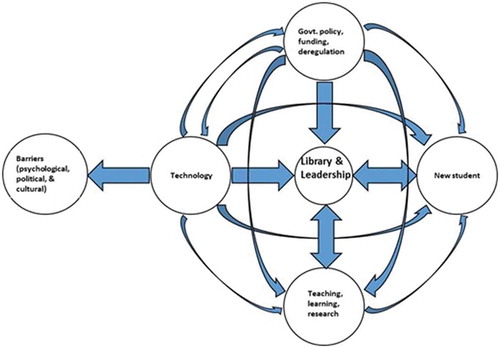

The research revealed that the influence of, or the relationship between, the factors affecting changing university library environments is a complex web as graphically presented in . The figure explains two-way relationships between the library and the new student, and the library and university teaching, learning and research. These relationships demonstrate the library’s focus or engagement with clients and the andragogical resources available for service efficiency. Government policy in university funding and the introduction of market forces are also having a profound influence on AULs (Goncalves, Citation2018; Gunapala, Citation2017). Budget cuts also affect students, as well as the university teaching, learning and research. They can induce a drastic reduction in full-time staff numbers, and the use of technology for cost-saving and ongoing delivery of efficient services (Howes, Citation2018). Technology seems to have the most profound influence on libraries from all directions as for all industry sectors (World Economic Forum, Citation2016). Technology is also indirectly impacting on libraries through its influence on government policy, students, and university teaching, learning and research (World Economic Forum, Citation2018). While these forces ‘disruptively’ influence the university library performance (positively and negatively), there are also forces which stand as barriers to libraries’ adaptation to change. According to the academic commentary, these barriers are psychological, political, strategic or cultural (Coetzee & Stanz, Citation2007; Graetz et al., Citation2006; Hoffman & Henn, Citation2008). Two informants also pointed out that staff mindsets can be a barrier in adapting to the changing AUL environment. Informants also indicated a range of other obstacles such as staffing, finance, power plays within university bureaucracies, employment agreements and the unions to a name some examples. These barriers, or the restraining forces, hinder when an organisation plans to move away from the status quo, causing change efforts to go awry or become stalled.

Psychological barriers, such as denial, can adversely affect the planning and implementation of change management efforts due to inaccurate understanding (Tedlow, Citation2010). Barriers to effective implementation of change strategies include rejection of some information, clinging to old ways of thinking, not having a united voice among decision-makers, and a lack of motivation and unity among staff members (Graetz et al., Citation2006); these all present as potential or actual blockers.

Based on the above information, this research developed an original conceptual framework, as in , to mirror significant factors influencing the AUL environment. Both market forces (introduced along with government policy, funding cuts, and deregulation of higher education) and advancement in ICT were having a profound effect on managing change. The prevailing literature also reveals that barriers to performance result in 70 per cent of change implementation or performance failures (By, Citation2005; Caboni, Citation2011; Tasler, Citation2017). Therefore, addressing barriers to successful change implementation needs to be a critical aspect of a change strategy.

Future of the university library

As all informants stated, and Harvey (Citation2015), the mainstream library information resources are digital resources, delivered online (Feldman, Citation2015). Higher education institutions have embraced increasing online delivery of education. All the informants and the literature pointed to the declining significance in traditional roles (i.e. acquisition, cataloguing, circulation, and reference service) and the emerging importance of collaborative library spaces and non-traditional functions such as publishing, research data management, information literacy and working with academic staff concerning teaching, learning and research (Feldman, Citation2015; Simons & Searle, Citation2014).

Views of experts (ACRL, Citation2006; Darnton, Citation2008; Johnson et al., Citation2015; Sandhu, Citation2015), as well as all informants, indicate a paradigm shift in the context of university libraries during the past few decades. Accordingly, the literature and the views of the informants show a change in the objectives of the future academic library as listed below:

Providing access to an array of quality educational information from anywhere, anytime, through the Internet (Gibbons, Citation2007; all informants).

The library cannot anymore own or provide access to all the information clients want. Information is endless, everywhere and exploding. Therefore, production and consumption of information far exceed the ability of the library to contain, manage, and control all of it (Baker, Citation2014a; Gibbons, Citation2007; all informants)

In an environment of rapidly advancing ICT, access to higher education is becoming global, and the library should enrich access to its electronic content and support learning, teaching, and research online (Lewis, Citation2016; Uzwyshyn et al., Citation2013; all informants).

Libraries connect people with quality information and support teaching, learning, and research (Levine-Clark, Citation2014; Lugg, Citation2011; all informants).

To find information, clients first go to user-friendly search engines (Deniz & Geyik, Citation2015; Flynn, Citation2010; all informants).

Libraries are attempting to win back students by providing friendly, student-centred, inspiring learning spaces (physical/virtual) for collaborative and individual study to learn, create and innovate knowledge (Gensler, Citation2014; Jamieson, Citation2013; all informants)

The library should be innovative in what it can do to add value to the university business rather than continue to do what was traditionally done (Marcum, Citation2016; O’Connor & O’Connor, Citation2007; all informants).

The purpose of the AULs should suit deregulated higher education in which market forces operate, and therefore function under marketing and business management fundamentals (Lewis, Citation2016; Sen, Citation2010; all informants).

Therefore, the purpose of the library today may be described as adding value to higher education business by connecting clients with information and facilitating teaching, learning, research, creativity and innovation of knowledge. How libraries can serve this purpose can be diverse, and each library may attempt to address its objectives in a way that suits them.

The informants of this research differed about the future of AULs. One group was confident that there will always be a future for libraries; while others were uncertain because of the rapidly changing environment fuelled by technological changes, shifting requirements and priorities of library users. Factors such as developments in publishing, distribution/sales, the convenience of access, ease of use, financial pressures, changing consumer behaviour and emerging new markets will have a sweeping effect on higher education libraries (Sayre & Riegelman, Citation2018).

In the future, information may be available in a digitised or another advanced format at a minimal cost (Sayre & Riegelman, Citation2018). With massive digitisation occurring, could there be one university library in Australia accessed online? Smarter search engines may make the information search more relevant, retrieval faster, more convenient, and user-friendly (Manoff, Citation2015). Most of the teaching, learning and research in higher education institutions might be available online. Therefore, the library as a physical entity may shrink with increasingly smaller print collections but continue to have the responsibility of recording, managing, and providing access to information produced by universities (Varheim, Skare, & Lenstra, Citation2019). The library may be only one of the places in the university providing collaborative learning spaces. Still, it may also be a meeting place or hub with many other facilities such as canteens, or a lounge atmosphere with outstanding fifth generation (5 G) Wi-Fi access. As competition may intensify from the private sector and other libraries to provide library services at a cost, universities may choose to outsource services to maximise the return on investment. Therefore, only the smart library may survive (Lyons, Rayner, & Samantha, Citation2016).

Stakeholder focussed library

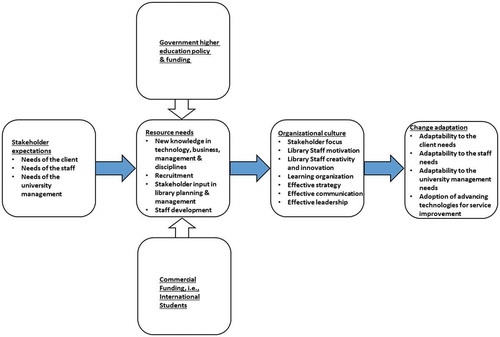

As the associated literature explained (Freeman, Citation2005; Shore & Kupferberg, Citation2014), and as agreed by all informants, stakeholder-focused strategies lead to enhanced performance and service delivery due to positive and negative commentary on performance. The informants also agreed with the literature that relevant knowledge, skills and capabilities are essential for the superior performance of organisations (Hallam, Citation2014; Violante, Citation2013). Knowledge and skills in technology are critical at a time of revolutionary advancement in ICT that underpins the complexities of change in AULs. The informants have acknowledged the need for disciplinary knowledge, in closely working with the academic staff to support teaching, learning, and research. Knowledge of business and management, such as marketing, strategic thinking, client service, human resource management, and leadership, was found to be critical for effective performance management in AULs (Shore & Kupferberg, Citation2014). To focus on the changing needs of students and academics, and add value to university business goals, satisfactory communication with all stakeholders and getting their feedback is essential in forming a stakeholder-focused organisation. Considering these findings, is a framework proposed for effective management of change in AULs. The framework was designed to meet the needs of its stakeholders, particularly students, academic staff, library staff, and the senior university management, in an environment of rapid change. The framework consists of four components.

1. Expectations of stakeholders: Satisfactory engagement with stakeholders (e.g. students, academics, and senior university management) is critical to align with stakeholder expectations. In a market-driven, deregulated higher education environment, adding value to the business is the key to staying relevant.

2. Resource needs: Resources to facilitate performance and satisfy stakeholder expectations in AULs are essential (Hines & Simons, Citation2015). While adopting relevant ICT is critical, knowledge of technology, business, management and disciplinary expertise is vital in managing university libraries in a competitive higher education environment. Appropriate recruitment practices that suit the new organisational demands help recruit people with essential new knowledge, skills and capabilities (Hines & Simons, Citation2015). Therefore, university libraries may need a flexible recruitment policy to offer competitive employment conditions in attracting such people to the library profession. Representatives of different stakeholder groups can be useful in management and planning meetings as a mechanism for feedback and adding value to university business, including to facilitate obtaining funding for the library. Furthermore, a satisfactory staff development process assists the development of organisational knowledge, skills, and capabilities during changing times.

3. Organisational culture: This component includes stakeholder-focused management, motivated staff for creativity and innovation, learning organisation culture, an organisation with an effective strategy, communication, and leadership to promote satisfactory performance. Stakeholder focus, along with staff knowledge, skills and capability building, and appropriate strategy, contributes to the adaptive process of an organisation.

4. Change adaptation: Completion of the first three components of the framework is fundamental in achieving the change adaptation objective as it meets the needs of all stakeholders, in addition to adopting advancing ICT in the process for service improvement.

The framework also emphasises the need for the attention to environmental/socio-political factors such as government higher education policy changes, including the support of commercial ventures, to transform libraries as value-adding constituents of universities. While the framework assists in making the library structure and the resources change-ready, it is possible to implement it in combination with any other change management plans or strategies. Continually adapting to changing environments is critical as the change is a permanent phenomenon (By, Citation2005; Jun & Rowley, Citation2014). As change is constant, continuous change management strategy is critical for performance improvement (Berlach, Citation2011; Victor & Frankeiss, Citation2002). Therefore, the proposed framework of the stakeholder-focused future library facilitates the constant change adaptation of the library to meet the demands of all stakeholders.

Conclusion

This qualitative study investigated the complexities of the rapidly changing AUL environment and the practices of libraries to address the related challenges and provides various theoretical insights. Firstly, the study provides an understanding of the complexities and the challenges imposed by the rapidly changing environment of the traditional university library and the issues that library leadership must address for them to adapt promptly and appropriately to create value for its continued relevance. Secondly, the findings in this research reveal a shift in AUL management from transaction-oriented management (TOM) model to engagement-oriented management (EOM) model from about the 1990 s. Introduction of market forces to higher education with declining public funding made this shift even more complicated. Thirdly, as the new knowledge is critical for effective library performance, AULs are making various innovative efforts to attract and retain staff with such expertise and experience using non-traditional methods of advertising and filling vacant positions. Fourthly, modernising LIS curricula within the library, university schools and in-house library staff development programs is also critical to provide new knowledge and skills necessary to address the skill gaps of AULs. The fifth aspect of this research has developed two frameworks to address the challenges of change in AULs. The change implementation framework recommended points to many critical elements for continuous performance improvement and highlights two vital forces, market forces and advancing ICT, on managing change. The change implementation framework also emphasises the need to address barriers to performance as part of the strategy. The other key aspect of this framework is the stakeholder-focused library framework designed for effectively managing change for continued performance improvement. The proposed shift implementation framework consists of four components: stakeholder expectations, resource needs, organisational culture, and effective change adaptation. The framework also emphasises the need to pay attention to government higher education policy changes as well as the appropriate commercial ventures for performance improvement.

The rapidly changing AUL environment brings significant challenges to library management requiring suitable amendments to policy and practice. This research recommends AULs to organise discussion forums to bring in academics and students periodically to discuss the challenges facing the library. While the library should encourage research on relevant issues, library leadership must look outside their comfort zone, particularly to the business sector, to investigate best practices. Libraries might consider amending their recruitment policy and practices to attract people with required new knowledge and skills and also funding appropriate staff development program for existing staff to help performance improvement. Findings of this research are primarily relevant to AULs but may also have relevance to university libraries in other countries depending on the environmental context and the impact of technological advances globally. However, as the participants of this research were limited to chief university librarians, it would be useful to obtain the perspectives of other staff and to include clients, or even conduct multiple case studies or mixed-method studies in future studies.

Managing change in university libraries is complex and not readily understandable. Therefore, any prescriptions for effectively managing change at this stage of transformation appear to be pre-emptive, or at best notional. The fundamental strategy for the library administrator is to appreciate the emerging reality and ensure adaptability, keeping the focus on adding and creating value to the teaching, learning and research outcomes of the university. In a rapidly changing environment, AULs expect to add value for the money spent and to explore new opportunities and exploit non-traditional knowledge, skills and capabilities that are becoming critical in finding their way forward. Change is part of our growth and our future. A university library is an integral component of the learning experience, but functions as a repository of knowledge and wisdom that extends far beyond the life of an individual library. While continuing research is essential to address the challenges of rapid change for AULs satisfactorily: effectively managing change is not only critical but existential.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matara Gunapala

Matara Gunapala completed his PhD thesis ‘The Complexities of Change, Leadership and Technology in Australian University Libraries’ at RMIT University in 2017.

Alan Montague

Alan Montague is a Senior Lecturer in human resource management at RMIT University

Sue Reynolds

Sue Reynolds is a Senior Lecturer in information management at RMIT University

Huan Vo-Tran

Vo-Tran, Huan is a Lecturer in information management at RMIT University

References

- Abbasi, N., Elkadi, H., Horn, A., & Owen, S. (2012). Transforming academic library spaces: An evaluation study of Deakin University library at the Melbourne Burwood Campus using TEALS. Retrieved from http://conferences.alia.org.au/alia2012/Papers/3_Anne.Horn.pdf

- ABS. (2004). Australian social trends. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/174FDA6313BDC7DECA256EB40003596E/$File/41020_2004.pdf

- ACRL. (2006). Changing roles of academic and research libraries. Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/issues/value/changingroles

- Afebende, G., Ma, L. F. H., Mubarak, M., Torrens, A. F., Ferreira, S. M. S. P., Beasley, G., & Ford, B. J. (2016). A pulse on the world of academic libraries: Six regions, six insights. College & Research Libraries News, 77(8), 389–395.

- ALIA. (2014). Future of the information science profession. Australian Library and Information Association Canberra Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/sites/default/files/documents/advocacy/ALIA-Future-of-the-Profession-ALL.pdf

- Anderson, R. (2015). A quiet culture war in research libraries – And what it means for librarians, researchers and publishers. Retrieved from http://insights.uksg.org/articles/10.1629/uksg.230/

- ANU. Australian National University Library. (2015). Annual report. Retrieved from http://anulib.anu.edu.au/files/document-collection/2015-sis-annual-report.pdf

- Australian Government Treasury. (2009). 2009–2010 Commonwealth Budget. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from aps://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview200910

- Baker, S. C. (2014). Library as a verb: Technological change and the obsolescence of place in research. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 17, 25–31.

- Baker, S. C. (2014a). Making it work for everyone: HTML5 and CSS level 3 for responsive, accessible design on your library’s Web site. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 8, 118–136.

- Barneveld, K., & Chiu, O. (2018). A portrait of failure: Ongoing funding cuts to Australia’s cultural institutions. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(1), 3–18.

- Bell, S. J. (2014). Staying true to the core: Designing the future academic library experience. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(3), 369–382.

- Berlach, R. G. (2011). The cyclical integration model as a way of managing major educational change. Education Research International, 2011, 1–8.

- Bieraugel, M., & Neill, S. (2017). Ascending Bloom’s pyramid: Fostering student creativity and innovation in academic library spaces. College and Research Libraries, 78(1), 35–52.

- Blackman, D. (2006). Knowledge creation and the learning organisation. In P. Murray, D. Poole, & G. Jones (Eds.), Contemporary issues in management and organisational behaviour (pp. 246–273). South melbourne: Thomson.

- Booth, M., McDonald, S., & Tiffen, B. (2010). A new vision for university libraries: Towards 2015. Paper presented at the VALA 2010 Conference. Retrieved from http://www.vala.org.au/vala2010/papers2010/VALA2010_105_Booth_Final.pdf

- Bostick, S., & Irwin, B. (2014). Library design in the age of technology planning for a changing environment. Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences Paper, (3). Retrieved from http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iatul/2014/plenaries/3

- Brabazon, T. (2016). The University of Google: Education in the (post) information age. London: Routledge.

- Bryson, J. M. (2011). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organisation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Burnes, B. (2004). Managing change: A strategic approach to organisational dynamics (4 ed.). Harlow, England: Prentice Hall.

- Burton, F., & Kattau, M. (2013). Out of sight but not lost to view: Macquarie University Library’s stored print collection. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 44(2), 102–112.

- By, R. T. (2005). Organisational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5(4), 369–380.

- Caboni, T. (2011). Exploring organisational change best practice: Are there any clear-cut models and definitions? International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 3(1), 60–68.

- Carrington, R., O’Donnell, C., & Rao, D. S. P. (2016). Australian university productivity growth and public funding revisited. Studies in Higher Education, 43(8), 1417–1438.

- CAUL. (2014). Strategic directions 2014-2016. Retrieved from Canberra http://www.caul.edu.au/about-caul/caul-strategic-plan

- Chalmers, J. (2017, September 27) in Adams, P. (Broadcaster). (2017). When robots come for your job. Late Night Live. Radio National Australian Broadcasting Commission. Sydney. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/latenightlive/when-the-robots-come/8992662

- Chan, D. L. H. (2014). Space development: A case study of HKUST Library. New Library World, 115(5/6), 250–262.

- Chang, A., & Bright, K. (2012). Changing roles of middle managers in academic libraries. Library Management, 33(4/5), 213–220.

- Childs, S., Matthews, G., & Walton, G. (2013). Space in the university library - an introduction. In G. Matthews & G. Walton (Eds.), University libraries and space in the digital world (pp. 1–19). Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

- Childs, S., Matthews, G., & Walton, G. (2013b). Space, use and university libraries - the future? In G. Matthews & G. Walton (Eds.), University libraries and space in the digital world (pp. 201–215). Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

- Chow, A. (2014). Leading change and the challenges of managing a learning organisation in Hong Kong. Journal of Management Research, 6(2), 22–38.

- Choy, F., & Goh, S. (2016). A framework for planning academic library spaces. Library Management, 37(1/2), 13–28.

- Click, A. B., Wiley, C. W., & Houlihan, M. (2017). The internationalization of the academic library: A systematic review of 25 years of literature on international students. College and Research Libraries, 78(3), 328–358.

- Coetzee, C., & Stanz, K. (2007). ‘Barriers-to-change’ in a governmental service delivery type organistion. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33(2), 76–82.

- Conifer, D. (2016). Budget 2016: University fee deregulation scrapped but universities still facing big cuts. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-05-03/morrison-abandons-uni-fee-deregulation/7380564

- Corrall, S. (2010). Educating the academic librarian as a blended professional: A review and case study. Library Management, 31(8/9), 567–593.

- Crittenden, S. (2009, December 13) Gillard’s University Reforms. Background Briefing Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/rn/backgroundbriefing/stories/2009/2718734.htm

- Dale, P., Beard, J., & Holland, M. (2016). University libraries and digital learning environments. London; New York: Routledge.

- Darnton, R. (2008). The library in the new age. The New York Review of Books, 55(10), 1–8.

- Davis, G. E. A. (2013). An agenda for Australian higher education 2013-2016. Canberra: Universities Australia.

- Deniz, M. H., & Geyik, S. K. (2015). An empirical research on general internet usage patterns of undergraduate students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 895–904.

- Dobbs, R., Manyika, J., & Woetzel, J. (2015). The four global forces breaking all the trends. Retrieved from http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-four-global-forces-breaking-all-the-trends

- Duderstadt, J. J. (2009). Possible futures for the research library in the 21st century. Journal of Library Administration, 49, 217–225.

- Durrani, S., & Smallwood, E. (2008). Innovation and change: The QLP-Y approach to staff development. Library Management, 29(8/9), 671–690.

- East, J. (2010). The Universoty of Queensland Library: A centenary history, 1910-2010. St Lucia, Qld: Queensland University Library.

- Emmanuel, I., & Reekie, G. (2004). Financial management and governance in HEIS: Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Education & Training. Retrieved from www.oecd.org/australia/33642632.PDF

- Feldman, S. (2015, November 25). Campus libraries rethink focus as materials go digital. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Video-Campus-Libraries/234341

- Fleming, J. H., Coffman, C., & Harter, J. K. (2005). Manage you human sigma. Harvard Business Review, 83(7/8), 106–114.

- Flynn, M. (2010). From dominance to decline? The future of bibliographic discovery, access and delivery. Paper presented at the World Library and Information Congress: 76th IFLA General Conference and Assembly, Gothenburg, Sweden. Retrieved from http://www.ifla.org/past-wlic/2010/71-flynn-en.pdf

- Freeman, R. E. (2005). The development of stakeholder theory: An idiosyncratic approach. In K. G. Smith & M. A. Hitt (Eds.), Great minds in management: The progress of theory development (pp. 417–435). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Parmar, B. (2004). Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited”. Organisation Science, 15(3), 364–369. doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0066

- Gensler. (2014). Why do students really go to the library? Future of the academic library. Retrieved from http://www.gensler.com/design-thinking/research/future-of-the-academic-library

- Gibbons, S. (2007). The academic library and the net gen student. Chicago: American Library Association.

- Gonçalves, P. (2018). From boom to bust: An operational perspective of demand bubbles. System Dynamics Review, 34(3), 389–425.

- Goodman, J., Melkers, J., & Pallais, A. (2019). Can online delivery increase access to education? Journal of Labor Economics, 37(1), 1–34.

- Grabowski, C., et al.. (2016). Today’s non-traditional student: Challenges to academic success and degree completion. Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 8(3). Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1377

- Graetz, F., Rimmer, M., Lawrence, A., & Smith, A. (2006). Managing organisational change (2nd ed.). Milton,Qld: John Wiley.

- Gray, R., & Barker, A. (2015). Increasing student engagement: Implementing an online model in a university library. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2015/Gray_Barker.pdf

- Gregory, M. (2015). University of Adelaide Library of the future:recommendations for a bold and agile university library. Retrieved from https://www.adelaide.edu.au/library/about/projects/lotf/Library_of_the_Future_Report_Final.pdf

- Gunapala, M. (2017). The complexities of change, leadership and technology in Australian university libraries (PhD thesis). RMIT University. Retrieved from https://researchbank.rmit.edu.au/view/rmit:162340

- Guthrie, J., & Neumann, R. (2007). Economic and non-financial performance indicators in universities: The establishment of a performance-driven system for Australian higher education. Public Management Review, 9(2), 231–252.

- Hallam, G. (2014). Victorian public libraries - our future, our skills: Research report. Melbourne: State Library of Victoria.

- Harland, F., Stewart, G., & Bruce, C. (2017). Ensuring the academic library’s relevance to stakeholders: The role of the library director. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(5), 397–408.

- Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2013). Stakeholder theory, value, and firm performance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(1), 97–124.

- Harvey, R. (2015). Editorial. The Australian Library Journal, 64(3), 163–164.

- Head, A. J. (2016). Planning and designing academic library learning spaces: Expert perspectives of architects, librarians, and library consultants. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2885471

- Hines, S., & Simons, M. (2015). Library staffing for the future. Advances in Library Administration and Organization, 34, lii.

- Hoffman, A. J., & Henn, R. (2008). Overcoming the social and psychological barriers to green building. Organisation & Environment, 21(4), 390–419.

- Howes, T. (2018). Effective strategic planning in Australian universities: How good are we and how do we know? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 40(5), 442–457.

- Islam, A. Y. M. A., Mok, M. M. C., Xiuxiu, Q., & Leng, C. H. (2018). Factors influencing students’ satisfaction in using wireless internet in higher education: Cross-validation of TSM. The Electronic Library, 36(1), 2–20.

- Jain, P., & Akakandelwa, A. (2016). Challenges of Twenty-First Century academic libraries in Africa. African Journal of Library, Archives and Information Science, 26(2), 147–155.

- Jamieson, P. (2013). Reimagining space for learning in the university library. In G. Matthews & G. Walton (Eds.), University libraries and space in the digital world (pp. 141–154). Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

- Johnson, L., Becker, S. B., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2015). NMC horizon report:2015 library edition. Retrieved from https://www.nmc.org/publication/nmc-horizon-report-2015-library-edition/

- Johnson, T. M. (2016). Let’s get virtual: Examination of best practices to provide public access to digital versions of three-dimensional objects. Information Technology and Libraries (Online), 35(2), 39–55.

- Jun, W., & Rowley, C. (2014). Change and continuity in management systems and corporate performance: Human resource management, corporate culture, risk management and corporate strategy in South Korea. Business History, 56(3), 485–508.

- Karp, P. (2018). $2.2bn funding cut to universities ‘a cap on opportunity for all’. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/feb/28/22bn-funding-cut-to-universities-a-cap-on-opportunity-for-all

- Kemp, D., & Norton, A. (2014). Review of the demand driven funding system. Canberra: Ministry of Education.

- Kilkelly, E. (2014). Creating leaders for successful change management. Strategic HR Review, 13(3), 127–129.

- Koz, O. (2014). Library, what’s library? Non-traditional library assessment. Paper presented at the Kansas Library Association, College and University Libraries Section (CULS) Spring 2014 Conference, Lawrence, Kansas. Retrieved from http://works.bepress.com/olga_koz/5/

- Kranich, N., Lotts, M., & Springs, G. (2014). The promise of academic libraries turning outward to transform campus communities. College & Research Libraries News, 75(4), 182–186.

- Lamberg, J., Tikkanen, H., Nokelainen, T., & Suur-Inkeroinen, H. (2009). Competitive dynamics, strategic consistency, and organisational survival. Strategic Management Journal, 30(1), 45–60.

- Levine-Clark, M. (2014). Access to everything: Building the future academic library collection. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(3), 425–437.

- Lewis, D. W. (2016). Reimagining the academic library. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lippincott, J. K. (2005). Net generation students and libraries. In D. G. Oblinger & J. L. Oblinger (Eds.), Educating the net generation (pp. 197–211). EDUCAUSE.

- Lugg, R. (2011). Collecting for the moment: Patron driven acquisitions as a disruptive technology. In D. A. Swords (Ed.), Patron-driven acquisitions: History and best practices (pp. 7–22). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Lyons, R. E., Rayner, & Samantha, & SpringerLink. (2016). The academic book of the future. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Manning, K. (2018). Organizational theory in higher education (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Manoff, M. (2015). Human and machine entanglement in the digital archive: Academic libraries and socio-technical change. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(3), 513–530.

- Marcum, D. (2016). Library leadership for the digital age. Retrieved from file:///E:/Research/Full%20text%20material/Library%20leadership%20role.pdf

- McPherson, E., & Ganendran, J. (2010). Rolling out the learning commons - issues and solutions. Paper presented at the ALIA Access 2010. Retrieved from http://conferences.alia.org.au/access2010/pdf/Paper_Thu_1100_Elizabeth_MCPherson.pdf

- McRobbie, M. A. (2003, April 21–22) The library and education: Integrating information landscapes – emerging visions for access in the 21st century library.

- Michalak, S. C. (2012). This changes everything: Transforming the academic library. Journal of Library Administration, 52(5), 411–423.

- Mitchell, E. (2008). Place planning for libraries: The space near the heart of the college. In J. M. Hurlbert (Ed.), Defining relevancy: Managing the new academic library (pp. 35–51). Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited.

- MOU. (2015). Monash University building program. Retrieved from https://www.monash.edu/library/about/initiatives/fmp

- MOU. (2016). Monash University Library annual plan. Retrieved from http://www.monash.edu/library/about/reports/annual-plan

- O’Connor, S., & O’Connor, S. (2007). The heretical library manager for the future. Library Management, 28(1/2), 62–71.

- Oakley, S., & Vaughan, J. (2007). Higher education libraries. In S. Ferguson (Ed.), Libraries in the twenty-first century: Charting new directions in information services (pp. 43–57). Wagga Wagga, NSW: Charles Stuart University, Centre for Information Studies.

- Oblinger, D. G. (2003, July/August). Understanding the new students: Boomers, gen-xers and millennials. Educause Review, 2003, 37–47.

- Oblinger, D. G., & Oblinger, J. L. (2005). Introduction. In D. G. Oblinger & J. L. Oblinger (Eds.), Educating the net generation (pp. 1.1–1.5). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/bookshelf/272

- Pan, D., & Howard, Z. (2010). Distributing leadership and cultivating dialogue with collaborative EBIP. Library Management, 31(7), 494–504.

- Parker, D. (1997). Total quality service at the Victoria University of Technology library. Teaching matters: Proceedings of a symposium (pp. 101–111). Melbourne: Victoria University of Technology.

- Partridge, H., Hanisch, J., Hughes, H. E., Henninger, M., Carroll, M., Combes, B., & Ellis, L. (2011). Re-conceptualising and re-positioning Australian library and information science education for the 21st century. Final report. Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

- Percival, K. (2015). University libraries 2015 planning. Retrieved from https://blogs.adelaide.edu.au/library/2015/04/16/university-libraries-2015-planning/

- Pinfield, S., Cox, A. M., & Rutter, S. (2019). Extending McKinsey’s 7S model to understand strategic alignment in academic libraries. Library Management, 40(5), 313–326.

- Popp, M. P. (2012). Changing world, changing libraries. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 52(2), 84–89.

- Provasnek, A. K., Sentic, A., & Schmid, E. (2017). Integrating eco‐innovations and stakeholder engagement for sustainable development and a social license to operate. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(3), 173–185.

- Raju, J. (2014). Knowledge and skills for the digital era academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(2), 163–170.

- Rossmann, D., & Arlitsch, K. (2015). From acquisitions to access: The changing nature of library budgeting. Journal of Library Administration, 55(5), 394–404.

- Rubin, R. E. (2017). Foundations of library and information science. American Library Association.

- Sandhu, G. (2015). Re-envisioning library and information services in the wake of emerging trends and technologies. 4th International Symposium on Emerging Trends and Technologies in Libraries and Information Services (pp. 153–160).

- Saver, C. (2015). Strategic succession planning essential to OR economic success. OR Manager, 31(1), 1–9.

- Sayre, F., & Riegelman, A. (2018). The reproducibility crisis and academic libraries. College and Research Libraries, 79(1), 2.

- Sen, B. (2010). Theory, research and practice in library management 8: Market orientation. Library Management, 31(4/5), 344–353.

- Sessoms, N. (2014, winter). Therapy dogs relieve stress for students. UAMS Library News, 2014(150), 1.

- Shapiro, S. D. (2016). Engaging a wider community: The academic library as a center for creativity, discovery, and collaboration. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 22(1), 24–42.

- Sharda, H. (2016). Cost cutting at what cost? Australian university scenario. Retrieved from http://www.aair.org.au/app/webroot/media/pdf/AAIR%20Fora/Forum2005/Others/Sharda.pdf

- Shore, D. A., & Kupferberg, E. D. (2014). Preparing people and organisations for the challenge of change. Journal of Health Communication, 19(3), 275–281.

- Simons, N., & Searle, S. (2014). Redefining ‘the librarian’: In the context of emerging e-research services. Paper presented at the VALA 2014. Retrieved from http://www98.griffith.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/handle/10072/63599/91677_1.pdf?sequence=1

- Sinikara, K. (2013). Opening a new Helsinki University Main library – A future vision, service design and collaboration. IFLA Newsletter, 2013(1), 4–13.

- Sorgo, A., Bartol, T., Dolnicar, D., & Podgornik, B. B. (2017). Attributes of digital natives as predictors of information literacy in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(3), 749–767.

- Swords, D. A. (2011). Introduction. In D. A. Swords (Ed.), Patron-driven acquisitions: History and best practices (pp. 1–5). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Tangney, S. (2014). Student-centred learning: A humanist perspective. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(3), 266–275.

- Tasler, N. (2017). Stop using the excuse “Organizational change is hard”. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/07/stop-using-the-excuse-organizational-change-is-hard%C2%A0

- Tedlow, R. S. (2010). Denial: Why business leaders fail to look facts in the face - and what to do about it. New York: Penguin.

- Universities Australia. (2017). Australia’s public spend on tertiary education lags Estonia and Turkey as a share of GDP. Retrieved from https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/media-item/australias-public-spend-on-tertiary-education-lags-estonia-and-turkey-as-a-share-of-gdp/

- University of New South Wales Library. (2015). Annual report 2015. Retrieved from http://annualreport.unsw.edu.au/2014/sites/all/files/file_link_year_content_file/AR_internals_2015_0405_sml.pdf

- University of Tasmania Library. (2011). Annual report 2011. Retrieved from ttp://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/278543/2011-Library-Annual-Report-web.pdf

- University of Tasmania Library. (2016). Future vision. Retrieved from http://www.utas.edu.au/library/about/library-future-vision

- University of Technology Sydney Library. (2014). Year in review. Retrieved from http://www.lib.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/attachments/page/YearInReview_2014_MR.pdf

- University of Technology Sydney Library. (2016). What is the future library. Retrieved from http://www.lib.uts.edu.au/future-library/vision

- Uzwyshyn, R., Smith, A. M., Coulter, P., Stevens, C., & Hyland, S. (2013). A virtual, globally dispersed twenty-first century academic library system. The Reference Librarian, 54, 226–235.

- Varheim, A., Skare, R., & Lenstra, N. (2019). Examining libraries as public sphere institutions: Mapping questions, methods, theories, findings, and research gaps. Library & Information Science Research, 41(2), 93–101.

- Viardot, E. (2017). Managing change and transformation for corporate sustainability. The Timeless Principles of Successful Business Strategy (pp. 77–90). Berlin: Springer.

- Victor, P., & Frankeiss, A. (2002). The five dimensions of change: An integrated approach to strategic organisational change management. Strategic Change, 11(1), 35–42.

- Victoria University Library. (2006). Annnual report. Melbourne: Author

- Victoria University Library. (2012). Annnual report. Melbourne: Author

- Victoria University Library. (2014). Annual report. Retrieved from https://www.VictoriaUniversityLibrary.edu.au/sites/default/files/about-us/pdfs/VictoriaUniversityLibrary-2014-annual-report.pdf

- Victoria University Library. (2015). Annual report. Melbourne: Author

- Victoria University Library. (2016a). Victoria University Library and records and archives services strategic plan 2016 to 2020. Retrieved from https://www.VictoriaUniversityLibrary.edu.au/sites/default/files/library/pdfs/library-strategic-plan-2016-2020.pdf

- Victoria University Library. (2016b). Pause exam pressure with dog therapy. Retrieved 1from https://www.VictoriaUniversityLibrary.edu.au/news-events/news/pause-exam-pressure-with-dog-therapy

- Violante, G. L. (Ed.). (2013). The new Palgrave dictionary of economics online. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wainwright, E. J. (2005). Strategies for university academic information and service delivery. Library Management, 26(8/9), 439–456.

- Watkins, A., & Kuglitsch, R. (2015). Creating connective library spaces: A librarian/student collaboration model. In B. L. Eden (Ed.), Enhancing teaching and learning in the 21st-century academic library: Successful innovations that make a difference (pp. 157–170). New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Watson, R., Wilson, H., Smart, P., & Macdonald, E. K. (2018). Harnessing difference: A capability‐based framework for stakeholder engagement in environmental innovation. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(2), 254–279.

- Wells, A. (2014). Agile management: Strategies for success in rapidly changing times – An Australian University Library perspective. IFLA Journal, 40(1), 30–34.

- Williams, B., (2017) in O’Neill M (2017). The AI Race, Lateline 8 Aug 2017. Australian Broadcasting Commission Sydney. Retrieved from http://iview.abc.net.au/programs/ai-race/NS1732H001S00#playing (now removed from access)