ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic required an agile and quick transformation of services in university libraries in the wake of government health directives. As an evidence-based library, engaging in the collection of evidence and reflective practice was a natural extension of the pandemic response. Once the critical response period had passed, staff at the University of Southern Queensland set about capturing the Library’s pandemic response within the wider context of society, government, and university activities in the form of a timeline. The timeline served to document actions taken in a time of crisis, recognise the staff workload involved, acknowledge the milestones achieved, and identify new performance measures to evaluate the impact of COVID-safe services This article offers a lived experience of how a university library can apply an evidence-based practice approach to inform decisions and drive improvements to service delivery. The timeline activity was not just about documenting what the Library did and when. It generated a source of evidence which has proved to be a useful tool in planning the return to campus activities and informing decision making about ‘COVID normal’ service models.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was a rapidly evolving situation that caught much of the world, including the international library and information community, by unwelcome surprise (Kosciejew, Citation2020). Disaster management responses from academic libraries demonstrated the potential of digital to provide alternatives to physical activities and services and appear to have accelerated the adoption of digital service delivery by staff and clients (International Federation of Library Associations, Citation2020). University of Southern Queensland (USQ) Library reacted in a similar way to other academic libraries – migrating services to digital channels, supporting staff to work remotely, and investing in electronic and digital alternatives to physical collections while campus spaces were closed to the public. Once the initial COVID-19 ‘pivot’ was complete, library staff committed to gathering evidence about their pandemic response, reporting the ‘story’ of the library’s crisis management response in a timeline. By using evidence-based processes to document rapid change, library leaders were able to make informed decisions, report against relevant performance measures, and identify continuous service improvements applicable to COVID-safe operations. The article reports how a university library can apply an evidence-based practice approach to capturing and reporting on disaster management activities.

Evidence-based Practice, Information Visualisation and Academic Libraries

Evidence-based practice supports libraries in demonstrating value and impact to stakeholders, making informed decisions, and understanding user needs. It is a structured way of working that brings rigour to the processes of collecting, interpreting, and applying valid and reliable evidence to support decision-making and continuous service improvement in librarianship (Howlett & Thorpe, Citation2018). Evidence-based practice promotes an applied approach that is ongoing and reflective, in which library staff position themselves to respond to challenges and leverage opportunities within their library’s local context (Thorpe, Citation2018). In academic libraries, evidence is increasingly important as a way of measuring, demonstrating, and communicating value to stakeholders. In the COVID-19 pandemic era, the value of scientific evidence is well understood with librarians and information professionals relying on reliable, valid guidelines and testing regimes to implement safe practices in collections, services, and spaces (OCLC, Citation2020). While library leaders and staff were forced to make quick and agile decisions about service delivery with very little evidence to work with in the early days of the pandemic (Council of Australian University Librarians [CAUL], Citation2020a), libraries with a culture of evidence-based practice have subsequently documented and contributed to the library and information science evidence base. Sharing stories through webinars (CAUL, Citation2020b; O’Sullivan, Citation2020), blog posts, (Bourdages, Citation2020; Cowell, Citation2020), and scholarly publications (Kosciejew, Citation2020), may come to be considered a distinguishing hallmark of the library sector during the COVID era.

One way of effectively communicating evidence is through visualisations, such as graphs, infographics, and images. Information visualisation has been adopted across industries as an analytical tool and as a way of enhancing understanding and generating insights from data. Varian (Citation2009) defines information visualisation as ‘the ability to take data – to be able to understand it, to process it, to extract value from it, to visualize it and to communicate it’. Visualisations provide overviews of patterns and trends more effectively than lines of text. In academic libraries, data visualisations have been used to analyse collection usage and subject holdings, to inform decision making about acquisitions and deselection, and to analyse scholarly communication citations (Finch & Flenner, Citation2016). Chen (Citation2017) emphasises the purpose of visualisation as one of gaining insights, as well as enabling effective communication.

One of the driving forces behind the adoption of information visualisation in academic libraries has been the ability to increase the way in which a library’s value is communicated to its end user. Grieves (Citation2019) reports that the infographic approach to data visualisation provides an effective alternative to written reports, by presenting tailored and targeted ‘stories’ for maximum impact. Little is reported in the literature about how data and information visualisation can contribute an evidence-based libraries toolkit. USQ Library’s lived experience of applying evidence-based practice principles to service delivery and communication using visualisations offer an insight.

COVID-19 and Australian Academic Libraries

Australian academic libraries reported a variety of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, with approximately half required to close their physical campus locations during 2020 (CAUL, Citation2020a). Australian university library leaders responded to their institutional context (Greenhall, Citation2020) and government health directives, transforming access to content, spaces, and services, while supporting their staff to adapt to remote working arrangements. The range of responses included:

providing alternatives options for information provision,

negotiating free access to content with publishers,

maintaining existing services,

migrating services to digital channels,

managing workplace arrangements and staff concerns,

addressing health and hygiene safety for staff and clients (O’Sullivan, Citation2020).

As O’Sullivan (Citation2020) reported, Australian university libraries had been transitioning to digital services for more than 20 years and were relatively well prepared for the challenges of online service delivery. The pandemic created opportunities for university libraries to engage creatively with their communities. For example, using makerspace equipment to 3-D print personal protective equipment (USQ News, Citation2020), and commissioning portraits to honour the contribution of individuals within the university during the pandemic (University of Adelaide, Citation2020). These opportunities for demonstrating agility and innovation, as well as for enhanced communication with the university community and stakeholders called for robust decision making and the ability to communicate with influence – the benefits of applying an evidence-based practice approach.

The Case Study

USQ is a multi-campus, regional university in Queensland, Australia, with more than 27,000 undergraduate students (University of Southern Queensland, Citation2020). USQ Library supports the learning, teaching and research outcomes of students and staff, providing access to digital and physical information resources, digital fluency, research support, and academic study skills at three campuses and virtually. Library leadership and staff use qualitative and quantitative approaches to interpret, apply, measure, and communicate the library’s contributions to the university community. USQ Library demonstrated an explicit commitment to becoming an evidence-based organisation, by employing a Coordinator of Evidence-Based Practice in 2017. The Coordinator engages library staff in developing deep understandings of their business and client needs, supporting a culture of continuous service improvement, promoting robust decision making and demonstrating value to clients and stakeholders (Howlett & Thorpe, Citation2018).

USQ Library’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic began in February 2020 with a growing awareness of the virus’ potential to impact library services and university business. Work began to support international students who were unable to return to studies on campus, adapting library spaces for physical distancing, and making more teaching and learning resources accessible online. Contingency plans during March 2020 changed rapidly with plans created on one day superseded by events, requiring daily or even hourly revisions (Greenhall, Citation2020). Following government health directives, the University’s executive closed the three campuses to staff, students, and the public on 25 March 2020. USQ Library moved to an exclusively online service model. Library staff who could work from home were instructed to do so. Staff who remained onsite, due to a lack of home internet access, took on the responsibility for digitising physical content for staff and students. All teaching, learning, peer support and research support activities transitioned to online only. With 75% of students studying online pre-pandemic (University of Southern Queensland, Citation2020), the Library had a strong digital offer prior to COVID-19. Additional funding was sought and granted to purchase electronic versions of textbooks. Campus libraries remained closed for more than 3 months and were among the first spaces to reopen in July 2020 for Semester 2.

In April 2020, with 92% of library staff working remotely, library leadership shifted their focus to reflecting on the library’s responses to the pandemic crisis. The authors identified the need to record the service responses and changes made, to learn from the experience, celebrate successes, plan for future disasters, and make informed decisions about ongoing service improvements. Library leadership saw the value in documenting the immense effort that teams contributed during the pivot to remote working and the opportunity to learn from the lessons of COVID-19. The team began to gather evidence about the library’s pandemic response and considered ways in which to present evidence to show how the library contributed to the university during the crisis. Evidence collection focussed on recording what changes each team had made to their service offer, when the changes were implemented, and how new and alternative service offers were being evaluated. A mixed methods approach to data collection was adopted to provide the context and story of each service change, rather than solely focussing on quantitative data activity reports. From the outset, it was acknowledged that this evidence gathering activity would document a unique moment in the life of USQ Library. It was anticipated that this snapshot would prove useful for future decision making around the pandemic or other crisis scenarios.

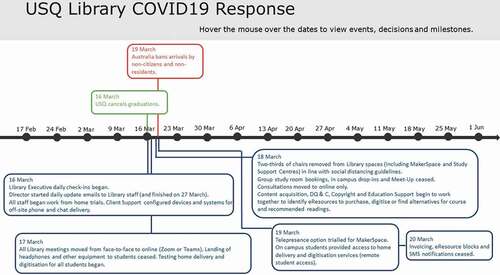

When it came time to analyse, evaluate and communicate the story of USQ Library’s COVID-19 response, the Associate Director (Library Experience) recommended a creative response to reporting the evidence. The suggestion was made to depict this information visually in a timeline to show the activities that occurred each week. The Coordinator accepted the challenge to design an interactive timeline which showed the rapid pace of iterative decision making during the early weeks and the ongoing service improvements that were subsequently introduced. Service changes were documented and positioned within the broader context of the pandemic at the community and university level. The timeline was built using Microsoft PowerPoint with multiple slides feeding data into the top-level timeline. When the viewer moved their cursor along the timeline, information displayed from the relevant week, from February 17 to 1 June 2020. Different font colours were used indicate the three different sources of information:

Blue for USQ Library’s activities and achievements.

Red for environmental impacts, such as changes to government health directives.

Green for university-wide decisions (Howlett, Citation2020).

The first draft of the timeline focussed on documenting the incident response actions during March 2020. shows an image of the timeline from prior to the campus closure.

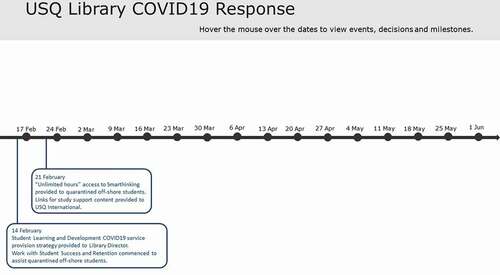

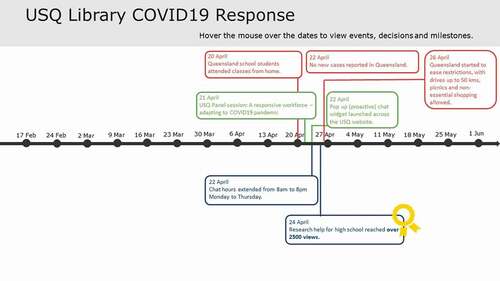

The timeline was then backdated to incorporate several initiatives that were implemented in February 2020. shows activity designed to support international students who were unable to return to study in Australia. As the draft was refined, milestones were added to highlight achievements, as well as reactions and responses. The Coordinator collated outcomes data and included these as achievements to the timeline. shows an image of the timeline following the campus closure with a milestone achievement highlighted by a yellow rosette symbol.

Discussion

The timeline visualisation painted a vivid picture of how USQ Library staff rapidly responded and transformed services, and how they continued to implement service improvements as they settled into remote working arrangements. The benefits to the library’s leadership team were manifold. Firstly, it provided an opportunity to document and position the COVID-19 responses in relation to the wider environment and context. The timeline reflected to staff that the library leadership team acknowledged the impact of the iterative approaches on staff workload management and the client experience. The addition of the milestones to the timeline ‘story’ provided the opportunity to celebrate achievements of library teams who worked hard to ensure that students, teaching and research staff could continue to access information resources and library services via digital channels.

Documenting the steps taken to shut down the campus libraries subsequently provided a roadmap for planning and coordinating return to campus plans. This prompted staff to reflect on what services could be resumed, which ones needed to be adapted to COVID-19 safe practices, and which services might not resumed either because it was unsafe to do so, or because the service had been superseded with a successful, user-centred digital substitute. For example, Online Study Support sessions attracted hundreds of students during the campus closure. With the return to full on-campus services, study support sessions remain exclusively online, and attendance in 2021 continues to attract hundreds of participants.

As the library leadership team reviewed the timeline, the evidence pointed to new performance measures that were required to evaluate the impact of transformed services. Examples included the number of e-textbooks purchased, the amount spend on e-text purchases, the number of free e-resources that were added and activated in the library’s content management system, the number of pages digitised as course readings, and the attendance and engagement rates at online study sessions. These measures were adopted as performance indicators as the year progressed.

Experimenting with visualisation techniques to present the evidence of the library’s pandemic responses as a visualisation has been an effective way to communicate with staff, community, and industry. The minimalist design has proven useful in an applied, practical setting (Eaton, Citation2017). The timeline situates the activities and outcomes in the broader environmental and institutional context, depicting the library’s responses as a visually engaging and easily understood ‘story’. Experimenting with visualisation with the COVID-19 response ‘dataset’ has also increased confidence among staff in trialling creative and alternative approaches to reporting. It has demonstrated the effectiveness and impact that visualisations can have to communicate evidence with influence. With the rollout of vaccines underway in Australia, it is hoped that the timeline will exist as an artefact of a unique period in the history of USQ Library and stand as a testament to the resilience and innovation of staff.

Conclusion

During COVID-19, innovation was driven by necessity as Australian university libraries responded to a rapidly changing environment and strove to meet client needs in a time of ambiguity, uncertainty, and adversity. Academic libraries have been critical in ensuring the continuation of learning, teaching and research during lockdown periods. Visualisation can be a useful part of an evidence-based libraries toolkit, providing insight for the analysis of data and to effectively communicate outcomes to stakeholders. Capturing the activities and impacts of the COVID-19 transformation at USQ Library provided a snapshot of an agile and targeted response to the pandemic crisis. Visualising the evidence gathered as a timeline has provided a linear narrative situated within the relevant context of the university and government restrictions which reinforces the role and importance of the library in periods of crisis (Kosciejew, Citation2020). As an evidence-based practice initiative, the timeline documented what library staff did and when, and as a snapshot of what happened, it has become a source of evidence, which informed decision making in the following months. The timeline demonstrates how a university library can apply evidence-based processes in a crisis. The documentation of USQ Library’s response, and the application and communication of this evidence through the timeline, is a lived experience of that.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Clare Thorpe

Clare Thorpe is the Acting Director, Library Services at University of Southern Queensland (USQ) where she provided strategic direction, leadership and innovative management through the rapid and unprecedented change and uncertainty caused by COVID-19. As a practitioner-researcher, Clare uses a range of methodologies to apply evidence-based practice to collection management, user experience, staff development, teaching and learning design.

Alisa Howlett

Alisa Howlett is Coordinator of Evidence-Based Practice at the University of Southern Queensland library. Her professional experience in library and information science (LIS) spans over 10 years in a variety of information settings. Alisa’s research, mainly in evidence-based practice, has been published and presented internationally.

References

- Bourdages, L. (2020, September 8). “I’m baaaaack” – My experiences with going back to campus and back to the library during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hack Library School. https://hacklibraryschool.com/2020/09/08/im-baaaaack-my-experiences-with-going-back-to-campus-and-back-to-the-library-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- Chen, H. M. (2017). Information visualisation. Library Technology Reports, 53(3), 1–30. https://journals.ala.org/index.php/ltr/issue/view/633

- Council of Australian University Librarians. (2020a). ANZ university libraries take innovative steps to enhance service while combating the spread of COVID-19. https://www.caul.edu.au/news/anz-university-libraries-take-innovative-steps-enhance-services-while-combating-spread-covid-19

- Council of Australian University Librarians. (2020b). Lightning talks by university library staff on innovative library responses to COVID-19 [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSuf5hghucA

- Cowell, J. (2020, June 30). Measuring library impact during COVID-19. Medium. https://janecowell8.medium.com/measuring-library-impact-during-covid-19-1c9812b46c28

- Eaton, M. (2017). Seeing library data: A prototype data visualisation application for librarians. Journal of Web Librarianship, 11(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2016.1239236

- Finch, J. L., & Flenner, A. R. (2016). Using data visualisation to examine an academic library collection. College and Research Libraries, 77(6), 765–778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.6.765

- Greenhall, M. (2020). COVID-19 and the digital shift in action. Research Libraries UK. https://www.rluk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Covid19-and-the-digital-shift-in-action-report-FINAL.pdf

- Grieves, K. (2019). University Library Services Sunderland: Articulating value and impact through visual presentation of combined data sets. In S. Killick & F. Wilson (Eds.), Putting library assessment to work (pp. 154–161). Facet Publishing.

- Howlett, A. (2020). USQ Library COVID19 Response [video]. USQ Panopto. https://usq.au.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=0372fe03-91ea-4fb8-b507-acf4017b6a88

- Howlett, A. & Thorpe, C. (2018). ‘It’s what we do here’: Embedding evidence-based practice at USQ Library [Paper presentation]. The Asia-Pacific Library and Information Conference, Gold Coast, Australia. https://eprints.usq.edu.au/34729/

- International Federation of Library Associations. (2020, July 29). Attitudes and actions: What might COVID-19 change in the way we think? Library Policy and Advocacy Blog. https://blogs.ifla.org/lpa/2020/07/29/attitudes-and-actions-what-might-covid-19-change-in-the-way-we-think/

- Kosciejew, M. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic, libraries, and information: A thematic analysis of initial international responses to COVID-19. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 70(4/5), 304–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-04-2020-0041

- O’Sullivan, C. (2020, May 28). Australian universities demonstrating dexterity in the face of COVID-19 [video]. Vimeo. https://player.vimeo.com/video/423444642

- OCLC. (2020). REALM project - REopening archives, libraries, and museums. https://www.oclc.org/realm/home.html

- Thorpe, C. (2018). Evidence-based practice: Evaluating our collections and services. ANZTLA EJournal, 21, 87–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31046/anztla.v0i21.953f

- University of Adelaide. (2020). Community legends program. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/community/legends

- University of Southern Queensland. (2020). USQ Annual Report 2019. https://www.usq.edu.au/about-usq/governance-leadership/plans-reports

- USQ News. (2020, April). 3D printing on the COVID-19 frontline. https://www.usq.edu.au/news/2020/04/3D-facemasks

- Varian, H. (2009). Hal Varian on how the Web challenges managers. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/hal-varian-on-how-the-web-challenges-managers