Abstract

Myxicola infundibulum Montagu, 1808 is the most reported species of its genus, showing an unusually wide distribution from the Mediterranean area to Australia, North Europe, and North America, a situation deriving from a wide synonymizing of numerous species with M. infundibulum. Recently, genetic analysis confirmed that the Australian form of this species is an introduced taxon from the Mediterranean area, while the examined North American specimens were genetically and morphologically different. In the present paper we travel through the history of M. infundibulum from the first descriptions, trying to trace both the origin of this taxon and the origin of its wide distribution, through an analysis of the descriptions of all valid and invalid taxa to date. We also examined material present in the collection of one of the authors previously identified as M. infundibulum, comparing Mediterranean material to some from the English Channel, and material from North America. This led to the erection of four taxa new to science from material recently collected along the Italian coasts, and the restoration of Myxicola pacifica Johnson, 1901. Delimitation of taxa is based only on morphology, and we propose new morphological features to be considered; however, a molecular examination is planned in the near future.

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7CF64CB2-8B9C-4001-BE57-199B5F95213B

Introduction

The first cladistic analysis of the genus Myxicola, conducted on morphological features, included it in the most plesiomorphic clade within sabellid phylogeny (Fitzhugh Citation1989), where it remained until a recent phylogenetic analysis based on molecular sequence data, which moved the genus to a more apomorphic area, creating the clade Myxicolinae, containing two tribes, named Amphiglenini and Myxicolini (Tilic et al. Citation2020). However, before its relationships with other sabellid genera can be analysed, a large revision at the generic level is needed to understand the diversity and morphological variability within the genus.

Myxicola Koch in Renier Citation1847 (Polychaeta: Sabellidae) is a quite homogeneous genus characterized by a transparent, gelatinous tube, radioles united by a high palmate membrane giving the crown a peculiar shape, abdominal uncinigerous tori forming almost complete cinctures, and an atypical arrangement of dorsal and ventral lips of the peristomial collar (Fitzhugh Citation1989, Citation2003; Capa et al. Citation2011). Myxicola infundibulum (Montagu, Citation1808) is the type species of the genus as well as the most commonly reported taxon. The first difficulty that arises in revising the genus is the lack of a good description and figures of type species as well as the type material.

Although about 20 species have been described in the genus (Read Citation2015), the number of currently accepted species is lower, due to several subsequent synonymizations of different taxa that have led to the interpretation of M. infundibulum as a cosmopolitan taxon (e.g. Fauvel Citation1927; Day Citation1961; Imajima Citation1968; Hutchings & Glasby Citation2004; Edgar Citation2008). As observed by Capa and Murray (Citation2015), who described Myxicola nana Capa and Murray, Citation2015 from Australian waters, it is amazing that the most recent description dates to 1928, with Myxicola fauveli Potts, Citation1928. This was probably due to the poor character definitions and poor descriptions present in literature, such that most of the time any Myxicola specimens collected, especially in faunistic works, were simply identified as M. infundibulum.

With the advent of molecular techniques, some clarifications started to occur. This led to the identification in Australian waters of a taxon identified as M. infundibulum, an anthropogenic translocation out of its natural distribution range (Dane Citation2008). Morphological and genetic analysis conducted on specimens collected from North America (Maine, East Coast), the Mediterranean Sea (French, Italian and Croatian coasts) and Australia (Southern coasts) revealed that the former diverges both morphologically and genetically from the latter two, suggesting a unidirectional relationship of provenience between the two taxa (Dane Citation2008). However, it was taken for granted that the translocated European taxon was M. infundibulum and, once again, the lack of a good morphological analysis did not allow the erection of a new species for the American material. Dane (Citation2008) added the shape of abdominal uncini, which was a new feature in the morphological analysis. More recently, Darbyshire (Citation2019), studying the British Myxicola forms, and in agreement with Knight-Jones’ suggestions (Hayward & Ryland Citation1990), recognized at least two taxa, easily distinguishable for the tip of the radioles, dark in the one collected in the type locality, that should correspond to the type species of M. infundibulum, and white in another taxon that could be Myxicola sarsii Krøyer, Citation1856, one of the species previously synonymized with M. infundibulum.

The current understanding about the number of species and their definition and distributions within the genus Myxicola remains particularly limited, overlooking a whole set of heterogeneous characters related both to the hard structure of the body (i.e. chaetae and uncini) and to the features of the crown (Fitzhugh Citation1989). Dane (Citation2008) showed that the taxon considered M. infundibulum has some additional smaller flanking teeth in addition to the main fang of the abdominal uncini. She also suggested that variation observed between the geographically distant populations studied could be size-related, with larger specimens having a greater number of ‘secondary’ teeth. However, this was not corroborated by the finding in the very small-sized species M. nana Capa and Murray, Citation2015 of larger and more numerous uncinal teeth than in the larger Myxicola taxa (Capa & Murray, Citation2015).

In this study we present a re-evaluation of information contained in old literature, reconstructing the history of the taxon, the origin of its cosmopolitan state and the impact that the absence of type material has had on its taxonomy. In the second part we report results from morphological examination of M. infundibulum material present in the collection of one of the authors (AG), together with specimens more recently collected along the Italian coasts, introducing additional morphological features for separating taxa within the genus and describing several new Mediterranean species, together with the re-establishment of one taxon (M. pacifica Johnson, Citation1901), hitherto synonymized with M. infundibulum.

Materials and methods

Material examined

The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) database allowed us to access the current status of the Myxicola genus, detecting the nominal species synonymized with M. infundibulum and tracing their original descriptions. A re-evaluation of information about the presence of M. infundibulum in the Mediterranean waters through analysis of literature, from a hardcopy archive of one of the authors (AG) and from digitized materials (from Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti), was also performed.

Specimens of Myxicola present in the collection of the Marine Station of Porto Cesareo of the University of Salento (Lecce) (PCZL), located at the Zoological Laboratory of the Salento University (Giangrande et al. Citation2015), were re-examined. The material comes from the English Channel (Cornwall) and Pacific North America (Friday Harbor, WA, USA), together with material from the Mediterranean, collected along the Italian coast, Naples (Tyrrhenian Seas, Western Mediterranean), lake of Faro (Torre Faro, ME, Sicily, Italy), and Croatia (Adriatic Sea). In addition to this material already present in the collection, other specimens were collected along the Apulian coast, Ionian and South Adriatic Seas (Eastern Mediterranean). Lastly, historically sampled specimens of M. infundibulum from theGulf of Naples were analysed at the Darwin Dohrn Museum (DaDoM) of the Stazione Zoologica of Naples for comparison to our material from the same locality, and syntypes of M. pacifica were loaned from the Museum of Comparative Zoology of Harvard University (MCZH), for comparison to our material collected in Friday Harbor.

The vast majority of the Myxicola material comes from shallow waters (1–6 m), and sediment of varying typology (from sandy and muddy soft bottoms to hard substrata of natural and artificial origins). The only exception is the material from Croatia, which was collected at a greater depth (31 m) on sandy substrata (Mikac et al. Citation2013).

Photographs were taken using an SMZ 25 Stereo Microscope equipped with a DS-Ri2 video camera and a NIS–Elements BR 4.30.02 Nikon Instruments video-interactive image analysis system, while drawings were performed with a camera lucida. Specimens present at the DaDoM were analysed with a Leica S9i stereoscope and photographed by means of its dedicated software.

The natural colouration of fresh material makes the detection of possible patterns more difficult; thus, to highlight the staining pattern of the segments, peristomium and collar, worms were stained with methyl green stain, following the procedure of Winsnes (1985): the worms were fully submerged in methyl green dye and left for 1–2 minutes to absorb the stain. They were then transferred to 70% ethanol and left until the excess stain had been removed (approximately 15–20 minutes).

Characters used in the morphological analysis

A set of characters was considered including new features for the genus suggested by Dane (Citation2008) and Capa and Murray (Citation2015).

General body shape

Most descriptions (especially older ones) take into account the general body shape of the animal, distinguishing between uniformly tapering or abruptly rounded, truncated posteriorly and stockier forms. This information could be useful as it is generally linked to the size of the species, as well as for comparison with very old descriptions. However, in more recent years the informative value of this character has been criticized (Dane Citation2008).

Colouration

There is a great variability in colouration of alive individuals, a feature which appears to have been overlooked. An examination of web images of specimens classified as M. infundibulum (with information on the locality of the photo) revealed a great variability of forms and colours of the crown that can hide the presence of different species. The crown can be completely pale or coloured from violet to very dark brown; moreover, often the tip of radioles is darker than the rest of the crown. This characteristic is usually maintained in fixed material.

Biometry

The relative size of various parts has been used in descriptions of Myxicola species and of species belonging to other sabellid genera (Kröyer Citation1856; McIntosh Citation1922; Hayward & Ryland Citation1995; Costa-Paiva et al. Citation2007). The length of the animal and length of the thorax were measured laterally, while the length of the abdomen was calculated from the previous two measurements. The height of the peristomium (from the tip of the triangular lobe to the first chaetiger) and the width were measured ventrally at the fourth thoracic chaetiger. Crown length was measured laterally. Being the measurements of length and width alone not taxonomically reliable characters (Bick Citation2007; Costa-Paiva et al. Citation2007; Capa et al. Citation2011), they were utilized in the description, but not taken into consideration as discriminant features. However, some measurements such as number of thoracic segments, number of abdominal segments, and number of radioles are more homogeneous among the descriptions, allowing us to make comparisons. The ratio between crown and body length seemed particularly important to us; this feature was already emphasized by Dane (Citation2008), and is considered informative for the distinction between closely related species in other sabellid genera in recent studies (Giangrande et al. Citation2021). For this reason, the crown/body length ratio was considered a good feature also for separation of Myxicola taxa.

Crown features

The number of radioles on each side of the branchial crown was counted. Whenever there was a discrepancy between the two sides, the greater number was used for analyses. Palmate membrane height and shape were assessed. Radiolar tip length was measured from the very last pinnula; the shape of the tip was assessed as well as the presence and development of radiolar flanges along its length. The ratio between radiolar tip and radiole length was calculated. Pinnular* shape was assessed, distinguishing between thin and thicker ones as well as between blunt vs pointed tips. Maximum pinnular* length was also assessed within a single radiole. Radiole length was measured from the base, detaching it from the crown. The ratio between pinnula length and radiole length was calculated. The disposition of pinnulae was assessed, distinguishing between alternating and paired disposition through the observation of both transverse and longitudinal sections of the radiole under optical microscopy. The number and shape of hyaline skeletal cells inside the radiole, recently used in the characterization of the new species of Myxicola (Capa & Murray, Citation2015), were assessed. Ventral and dorsal lips, as defined by Fitzhugh (Citation2003) and Capa et al. (Citation2011), were examined, with regards to both general shape and height (along the antero-posterior axis). Dorsal radiolar appendages were analysed. Lastly, the presence of radiolar eyes was also carefully analysed, differentiating between simple and repetitive eyespots and compound eyes with complex structures.

Thorax features

The shape and features of the ventral lobe were assessed. The number of thoracic segments was counted. The shape of thoracic chaetae was detected at chaetigers 1 and 4. Thoracic uncini were detected at chaetiger 4 and analysed, considering the number and disposition of teeth above the main fang and their relative length. Although sabellids are remarkable among polychaetes in having eyespots distributed throughout the body (Fitzhugh Citation1989), and the presence of them on the peristomium and in interramal areas of the thorax was mentioned in early literature pertaining to Myxicola (McIntosh, Citation1922), this feature has been neglected in past descriptions and considered only in descriptions of Myxicola aesthetica (Claparède, Citation1870) (Hayward & Ryland Citation1995). The presence or absence of eyespots on the thorax was therefore judged to be potentially informative (Dane Citation2008). If present, the segment range of eyespots was also recorded, and for the thorax the first segment with eyespots was noted. In relation to this, we made a point of differentiating between properly named interramal eyespots, as have been found in recently described Myxicola species (Capa & Murray Citation2015), and the lateral eyespot (Capa et al. Citation2014), challenging the informative quality of such differentiation. We also assessed the presence or absence of peristomial eyes.

Abdomen features

The number of abdominal segments was assessed. Abdominal chaetae and uncini were detected at chaetigers 21–24, counted and analysed, considering the shape of the breast, the number and disposition of teeth above the main fang and their relative length, as well as the length of the main fang with respect to the breast. Eyespots on the abdomen have not previously been noted at all for the genus Myxicola, whilst pygidial eyespots have been recorded for at least M. infundibulum (Day, Citation1961). For this reason (and likewise for thoracic eyes) we assessed the presence or absence of abdominal eyespots, again differentiating between interramal eyespots properly named and lateral eyespots, and reporting their disposition along the segments. The shape of the pygidium was assessed, together with the presence and disposition of pygidial eyes.

Staining pattern

Methyl green staining was useful only in highlighting the glandular girdle, because in all the examined species the colouration was homogeneous with only the peristomium maintaining a darker colouration with respect to the rest of the body (comprising the crown); the glandular girdle was white. Therefore, it was not considered of diagnostic value.

Results

Part I: Literature analysis

1. Tracing the history of the type species Myxicola infundibulum

The difficulty in identifying the different taxa previously attributed to this species is not only in the presence of very poor descriptions of old material, but also in the absence of type material for this taxon. Moreover, although the original description of M. infundibulum is attributed to Montagu (Citation1808) from material collected from Salt Stone, in the estuary of Kingsbridge (Devonshire, United Kingdom), an almost identical form seems to have been described 4 years earlier by Renier for specimens collected from the Adriatic coasts, as reported by Giuseppe Meneghini (Citation1847).

At present, the species is reported with Montagu as authority in WoRMS (2022), even though Muir and Petersen (Citation2013) underlined how the species has been often reported with Renier as descriptor (e.g. Fauvel Citation1927; Uschakov Citation1955; Hartman Citation1968; Bellan Citation1978; Hobson & Banse Citation1981; Hartmann-Schröder Citation1996; Huang Citation2001; Simboura & Nicolaidou Citation2001), as well as in physiological works and field guides (e.g. Campbell Citation1976; Wirtz Citation1995). In addition, the specific name and authorship M. infundibulum (Grube) has also been used at least twice since 1899 (Nicol & Young Citation1946; Roberts Citation1962 – although Nicol later changed his mind, see Nicol Citation1948). This led to some confusion within the reports of M. infundibulum during the 19th century in European waters, with some authors referring to the description of Montagu as the original one, and others to Renier’s.

Giuseppe Meneghini (Citation1847) not only summarized in his work Renier’s observations about a polychaete that would belong to the taxon “Myxicola infundibulum” but also reported the observations of other naturalists, allowing us to reconstruct the history behind this taxon.

The first description of the animal that would later be named M. infundibulum from Renier dates back to 1804, 4 years before Montagu’s description. Here, Renier (Citation1804) was already solving a problem of synonymy between “Sabella gelatinosa” and “Terebella infundibulum”, where the first was the mucus case of the latter (Tav. alfab. delle Conchiglie Adriat. 1804, p. Xlll, no. 579, note-e). In a second and more in-depth description, again in 1804, Renier changed the name of the species to “Terebella buccina (Terebella Trombetta – Térébelle Trompette)”. In this description we find for the first time the character that stimulated the interest of the naturalists of the 19th century: the peculiar crown shape, with all the radioles tidily disposed and connected by a very high palmate membrane, giving the overall shape of a funnel popping out of the substrate (Renier Citation1804, p. XIX). Based on this and other characters, 3 years later Renier established a new genus for this species, that was named “Tuba divisa (Trombetta divisa)” with the description: “[…] inhabitants of mucus tube, without lateral organs. […] Gills by means of a funnel shaped membrane. Genitals of both sexes visible” (Renier, Citation1807b, Tav. VII).

In the second part of the work, Meneghini lists all the successive descriptions of species having the same peculiar characters noted by Renier. Cuvier (Citation1829-1830, p. 118) reported the species “Sabella villosa” as follows: “[…] there is [one] with gills but as simple funnel around the mouth, [formed] by numerous filets, highly clamped and ciliated on the internal face; foot often imperceptible”; Montagu’s “Amphitrite infundibulum” was also defined by Lamarck (Citation1838, p. 611) as “Equipped with gills forming a funnel with rays on the margin; the singles [gills] are clamped together in a semi-circular membrane fringed on the strip; body sub-naked and smooth”. It is clear that all the features reported are important at the generic level, meaning that they are present in most of the Myxicola species.

We re-evaluated the description of Montagu (Citation1808), from the Salt Stone in the estuary of Kingsbridge, reporting a worm with a long body (20–25 cm in length and up to 160 segments, which decrease in size towards the pygidium), and a crown formed by two semi-circular halves, each constituted by around 37 radioles. The peculiarity of this species is: “[…] the connected fibers of the tentacula, in which it differs from all other hitherto described” Montagu (Citation1808). So, when the animal opens its crown, the two halves form almost an uninterrupted circle, smooth on the outer surface, but tentaculate (with pinnules) in the inner one. Body colour orangish, with white annulation, while crown purple on the outer face and chestnut in the inner one, with radioles’ tip darker. Mouth purple with lips bordered by chestnut. The animal lives in gelatinous tubes composed of strata of different colours, sunken inside the substratum and exposing only the crown into the water column. Interestingly, it has already been proposed that Terebella infundibulum Renier in Meneghini, Citation1847 and Amphitrite infundibulum Montagu, Citation1808 may represent different species, thanks to differences noticed between their original descriptions (e.g. the structure of the tube, which is shown as essentially smooth by Montagu and like drippy candle-wax by Renier) (Muir & Petersen Citation2013).

Meneghini continued citing the studies of Delle Chiaje (Citation1829, Citation1841), who classified the species under the name “Sabella infundibulum”:

Body yellow, ringed and depressed, equipped anteriorly with a roster among the laminar gills, which are violet in the external face and yellowish in the internal one, with little parallel branchial appendices, which make the internal surface hairy, and the semi-circular margin curled blue: cartilaginous transparent tube, depressed, curved.

A similar animal was also described by Forbes (Citation1841, p. XXX) as:

inhabiting a gelatinous tube, submerse in the sandy substrata 3–4 feet below sea surface; the body of red-dusky color formed by possessing 140 segments with two whitish transversal lines each segment and all bearing a fascicle of chaetae on both sides; the head is encircled by two fascicle of gills like a crown, each of them formed by 28 cirri and bearing in the internal side small and very motile pinnulae which create ascendant and descendant current.

Koch is the last person cited by Meneghini in his work, having found an annelid corresponding to the description of Forbes near Trieste. He cited this fact in his lecture at the Gabinetto di Minerva, 18 January 1846, naming it “Myxicola villosa”. In particular he observed that even if the gills are divided into two halves, they form a complete funnel when open, where the crown appears uninterrupted, as in the description of Renier.

Lastly, Meneghini underlined some differences reported by the above-cited naturalists in their descriptions. In particular, he noted a different number of radioles as well as a different number of segments. Moreover, the presence of fascicles of chaetae was not reported by Renier, and both the presence of genital organs on the head and the continuity of the crown were an error made by Renier (the first almost surely due to confusion among the mouth, dorsal and ventral lips and radiolar appendages). Based on these differences, Meneghini concluded that the descriptions reported above, if not ascribable to the same species, surely referred to closely related ones.

The last three works that we re-evaluated are from studies that took place in the same location, namely the Gulf of Naples, but over a time span of 50 years (Claparède, Citation1870, p. 142; Lo Bianco Citation1893; Iroso Citation1921). In all these works the biodiversity of polychaetes inhabiting the area was addressed, and contain both the observation of the presence of the taxon M. infundibulum, and its description. In the first source, after the description of the individuals found in the Gulf of Naples, Claparède discusses the effective identity between the individuals from the British Channel and the Mediterranean ones. In particular, he reports the opinion of Quatrefages, who declares that the Mediterranean Myxicola: “[…] surely have any relationship with Montagu’s Sabella Infundibulum”. However, this opinion was linked to a misconception of Quatrefages, who considered the specimens from Montagu a true Sabella (Quatrefages Citation1866, p. 557). Claparède, instead, states that specimens from Salt Stone and from the Gulf of Naples belong to the same species, or, if not, they are very similar. In fact, he reports that the description of Montagu coincides with the characters observed in the individuals from Naples, except for the length, number of segments and number of radioles (9–10 cm in length against 20–25 cm; 115–125 segments against up to 160; and 20 pairs of radioles against 37). Claparède also describes the presence of dark eye spots, 25 µm in diameter and constituted by a crystalline substance surrounded by pigments, placed behind most of the fascicles of setae. In the paper by Lo Bianco (Citation1893) the author had already placed “Renier” (Citation1847) as the first description of the species, instead of Montagu (Citation1808). He reports a body length of up to 12 cm with a crown length of up to 2.5 cm and around 120 setigers in total (8 thoracic), which he defined as bi-ringed (surely linked to the peculiar disposition of the abdominal uncini). Notably, he reports the first segment as devoid of chaetae, which he describes as capillaries elongated at the extremity, and the whole thorax as devoid of uncini. The abdominal uncini are reported as bi-rostrate. Moreover, a group of interramal eyespots located posteriorly to most bundles of chaetae and a distinct ventral groove is reported. The crown is described as having 20 pairs of radioles with a high number of pinnulae, which stop at the end of the palmate membrane, leaving only the distal end of the radiole to extend beyond it (this means that the palmate membrane end, pinnulae ending point and radiole distal end starting point more or less coincide). Iroso (Citation1921) reported only the presence of the species, without a description of the specimens.

The colouration is also consistent, with a dark-violet crown maintaining a more intense colouration both on the dorsal side of the radioles and in their distal end, while the body is reported as brick-like in colour with some pasty transversal bands (which were not observed in our individuals).

What is apparent is that we cannot be sure that the descriptions from Montagu and Renier refer to the same species, and that the species described by Montagu as M. infundibulum is actually present in the Mediterranean area. In the present paper we followed the indication of WoRMS (2022) considering M. infundibulum sensu Montagu as the type species, considering the better quality of the description as well.

After these first findings, the species was later reported outside Mediterranean and English waters, up to South Africa, North America, Japan and Australia (Fauvel Citation1927; Day Citation1961; Imajima Citation1968; Goldman & Chandler Citation1986; Høisæter Citation1989; Langton & Robinson Citation1990; Hayward & Ryland Citation1995), also displaying a large range of substrata (Smith & Carlton Citation1975), from intertidal to deeper and open waters (Mikac et al. Citation2013). This, however, was also due to the extensive synonymization of several described species with this taxon. At present, this remarkable ecological flexibility, together with the global distribution, has led to uncertainties around the status of M. infundibulum, as it is referred to in different sources in the literature as either cosmopolitan or introduced (Smith & Carlton Citation1975; Boyd et al. Citation2002), suggesting the existence of numerous overlooked taxa.

The process of synonymization of most of the past described taxa with M. infundibulum, resulting in its cosmopolitan distribution, was started by Fauvel (Citation1927), who synonymized M. sarsi Krøyer, Citation1856, M. grubii Krøyer, Citation1856, M. modesta Quatrefages, Citation1866 and M. parasites Quatrefages, Citation1866, plus M. infundibulum both sensu Claparède (Citation1870) and sensu Lo Bianco (Citation1893), making the description of M. infundibulum, present in Fauvel (Citation1927), a mixture of descriptions from all the historically analysed material. As already mentioned, Phyllis Knight-Jones, in her contribution to the Handbook of the Marine Fauna of the British Isles and Northwest Europe (Hayward & Ryland Citation1990), listed M. sarsi as a valid species for the UK with a northern distribution. In the same guide, she described M. infundibulum as having a more southern distribution, and one of the distinguishing features between them was the presence (M. infundibulum) or absence (M. sarsi) of dark tips to the radioles. Officially, however, M. infundibulum is still the accepted name covering both forms.

2. Currently recognized species within the genus Myxicola

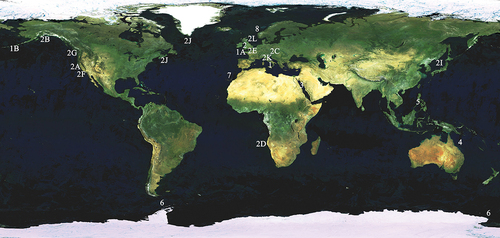

According to what was reported in WoRMS, of the 24 nominal Myxicola species, at the present, only eight are considered valid (); the distribution of these eight species is shown in .

Table I. Species described in the Myxicola genus (*sensu Hayward & Ryland Citation1990) in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS).

As a whole, Myxicola taxa can be divided into two groups according to the number of thoracic chaetigers: taxa having five or fewer thoracic chaetigers (“aesthetica group”) and taxa having eight or nine thoracic chaetigers (“infundibulum group”). Although taxa having fewer than five chaetigers often are small-sized forms, as observed by Capa and Murray (Citation2015), the number of thoracic chaetigers is not always linked to size.

All the accepted species listed thus far share the presence of sufficiently complete descriptions, except for M. sarsi which is mostly lacking what can be considered a true description. All we know for this species is that “[… it has] a cylindrical form, color smooth, with no distinct spots or rings, 12 pairs of gills and 11” of length for the whole animal” (Krøyer Citation1856, p. 9). Also, the type locality is not reported, even if it can be deduced from Krøyer’s general area of study; in the same work Krøyer describes M. steenstrupi from Greenland. Thus, we are not surprised that Capa and Murray (Citation2015) report only six valid species for the genus Myxicola, in addition to M. nana, described in the same article.

Among the accepted species, M. aesthetica and M. nana are easily recognizable thanks to their small dimensions and low number of thoracic segments (<6), with the latter differentiated from the former by a low palmate membrane, presence of a pair of subdistal radiolar eyes and the presence of six teeth of homogeneous size on the main fang, in abdominal uncini. Moreover, M. nana is known from soft-bottom environments in the Corals Sea (Lizard Island, Queensland, Australia), while M. aesthetica is commonly reported on hard substrata or as an epifaunal component of calcareous algae, with an original Mediterranean distribution (Tyrrhenian Sea, Gulf of Naples, Naples, Italy). Other small species of this genus are M. ommatophora Grube, Citation1878 and M. fauveli Potts, Citation1928. The first comes from the Philippine Archipelago and shares with M. nana the presence of subdistal radiolar eyes, but it shows 8 thoracic segments, together with a high number of abdominal segments (116 against 30) and radioles (19–24 pairs against 6 pairs) and a higher palmate membrane (reaching the radiolar tip), making it easily distinguishable from the Australian species. The latter species, described from the Red Sea (Suez Canal, Egypt), shows 8 thoracic segments, an intermediate number of abdominal segments (60–70) and 12 pairs of radioles; peculiarities of this species are an inconspicuous palmate membrane and the subdivision of the radiolar tip into a proximal half, characterized by a lateral prolongation of the radiolar flanges terminating with a round edge, where a concentration of “hyaline cells”, resembling eyespots, is present, and a bare radiolar tip.

A similar general morphology is shared by M. sulcata Ehlers, Citation1912, from the Ross Sea (Victoria Land, Southern Ocean) and re-described by Tovar-Hernández et al. (Citation2017) from the Patagonian Shelf. This species, reported for a variety of depths and substrata (from intertidal to 83 m depth; from sand to coarse sand and shells, to dock pilings) is still a small-sized species, with 8 thoracic and 35–72 abdominal segments and 12–17 pairs of radioles, but with a high palmate membrane.

The last accepted species is M. violacea (Langerhans, Citation1884) from Madeira Islands (Portugal), which is the second smallest reported species (23 mm with the crown), with 8 thoracic, 30–50 abdominal segments and 11 pairs of radioles connected by a high palmate membrane; an interesting set of features is also present, with the presence of peristomial (2 pairs), interramal (one each segment from fourth thoracic segment) and pygidial eyes (6), a radiolar skeleton composed of a row of single hyaline cells and the alternation of larger and smaller abdominal uncini along the tori. The presence of a ciliated epithelium that covers the whole peristomium has also been reported.

Among the remaining 14 listed species (), taxa having five or fewer thoracic chaetigers were synonymized with the M. aesthetica group (M. dinardeensis Saint-Joseph Citation1894 and M. glacialis Bush Citation1905), whilst taxa having eight or nine thoracic chaetigers were synonymized with M. infundibulum (M. affinis Bush Citation1905, M. conjucta 1905, M. grubii and M. steenstrupi Krøyer 1856, M. modesta and M. parasites Quatrefages Citation1866, M. pacifica Johnson Citation1901, M. monacis Chamberlin Citation1919, M. viridis McIntosh Citation1923, M. platychaeta Marenzeller Citation1884, M. michaelseni Augener Citation1918). Fauvel (Citation1927) synonymized four of the taxa now under the name “infundibulum”.

3. Historical roots of the cosmopolitan status of Myxicola infundibulum

The synonymization of several species with M. infundibulum stood for more than 70 years (1847–1923), but the quality of the descriptions oscillated dramatically over time, featuring down in-depth works as well as rough ones. This vacillation seems to be not related to the age of the studies. This does not allow us to treat all the descriptions in the same way; we must rely more on the more complete ones. Moreover, most of the descriptions do not contain comparable illustrations, and the location of type material is usually not stated.

On the other hand, the distribution of the proposed taxa appears to be almost global (except for Antarctic waters), and mostly in the northern hemisphere, but this may be due to a sampling bias as well as to “extrinsic factors” (“author effect” sensu Giangrande and Licciano Citation2004).

We proceeded to examine the descriptions of all the species synonymized with M. infundibulum through the evaluation of all available original works.

Myxicola affinis Bush, Citation1905 (Tubicolous annelids of the tribes Sabellides and Serpulides from the Pacific Ocean. Harriman Alaska Expedition). Type locality Pacific Grove, California, USA.

Body with 8 thoracic segments and 50 abdominal ones. Colour yellow. Body metrics cannot be used in this study, as both body length and first segment length are 4.5 mm (probably a copying error). Crown showing 20 pairs of radioles and very long pinnulae which are greenish in colour. The crown length is 12 mm, 3 mm of which comprises the slender and tapered radiolar tips only. Broadly hooded chaetae and thoracic uncini stouter and less curved.

Myxicola conjuncta Bush, Citation1905 (Tubicolous annelids of the tribes Sabellides and Serpulides from the Pacific Ocean. Harriman Alaska Expedition). Type locality Alaska Pacific coast.

Body yellowish, tapered towards both anterior and posterior end, with 8 thoracic biannulate segments and 107 abdominal. There are 20 pairs of radioles of pale colour, with numerous and very long pinnulae, of intense brown colour; palmate membrane high, just leaving the radiole distal ends, relatively long and tapered, unadorned and free. The halves of the crown are separated ventrally by a triangular fleshy lobe. The largest individuals described were 120 mm long, of which 17 mm comprised the crown. The author reported also shape-changing chaetae, describing long chaetae with short and broad blade terminating in a slender capillary end in the first segment, arranged in circle, and more slender and longer chaetae, with spear-like blade or hastate and long, slender capillary end, in the inner art of the tuft of segments from the sixth to the eighth; only two thoracic uncini each segment are reported. Abdominal chaetae with simple spear and long, slender ends are present; abdominal uncini are characterized by a long and slender main fang, with only one close shorter tooth. No eyes were described.

Myxicola grubii Krøyer, Citation1856; (Afhandling om Ormeslaegten Sabella Linn., isaer med Hensyn til dens nordiske Arter [Alternate title: Bidrag til Kundskab af Sabellerne]. Oversigt over det Kongelige danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Forhandlinger).

The type locality of this taxon reported by WoRMS is the “Danish Exclusive Economic zone”. However, Krøyer specified that the species occurs in the North Adriatic Sea (Trieste).

Body stockier, of pallid pink colour, with a series of dorsal-posterior darker spots; 45–49 segments and width 1/8 of the length. Crown purple with reddish pinnulae, from medium to very short length (1/4 of the body length); 21–24 pairs of radioles, with short radiolar tips, most of them spiralized; buccal cirri (probably dorsal radiolar appendages) very short, club-shape. Body metrics are reported in “pollices” (from Latin, the language in which the description is made), 2.5 for M. grubii and 10 for M. infundibulum. However, it is not reported whether the unit of measure refers to the Latin one, the English one, or some German other, and thus any comparison with other species remains impossible.

Myxicola michaelseni Augener, Citation1918 (Beitrage zur Kenntnis der Meeresfauna Westafrikas). Type locality Namibian Exclusive Economic Zone.

Colouration ranging from a yellowish-gray to whitish with purple shading. Segments more or less distinctly two-ringed, 8 in the thorax and up to 80–90 in the abdomen in the larger individuals. Crown ¼–1/6 length of body, holding up to 19 pairs of radioles (the number of radioles increases with the size of the individuals). Radiolar tip very long, up to half of the length of the whole radiole, with an elongated lanceolate shape; palmate membrane low (the author reports a great variability in the height of the palmate membrane, with some individuals showing membrane just reaching the radiolar tip and others having membrane extending well beyond that point). Thoracic hooks showing two close-fitting, pointed secondary teeth over the main fang, with a tertiary unpaired tooth visible above and between the two secondary teeth, which can hardly be seen in profile; abdominal hooks with a short secondary tooth. The author reports the presence of a row of thin black points on each segment, reduced to 1 or 2 on the chest (= thorax?), with a high probability of interramal eyespots, as the same Augener describes for the pygidium ([…] a row of small black dots, at least ocelli). Interestingly, the absence of radiolar eyes was assessed, as well as the structure of ventral and dorsal lips:

The buccal tentacles, sometimes tinged with a faint purplish color, are triangular, fairly broad, compressed, flap-like processes that rise above the ventral margin of the head and protrude about twice the mid-ventral lobe of the collar: they can also be shorter and be less compressed. The two halves of the head at the base of which the gill leaves rise laterally to the outside. There are two fleshy ear-shaped structures separated by a deep incision, the concave side wall of which is repeatedly indented. The tentacles arise ventrally and internally at the lower ends of the halves of the head. (p. 590)

Myxicola modesta Quatrefages, Citation1866 (Histoire naturelle des Annelés marins et d’eau douce. Annélides et Géphyriens. Librarie Encyclopédique de Roret. Paris). Type locality St. Vaast, Normandy, France. Body brown-greenish, conical, with 8–9 thoracic segments and 41–42 abdominal ones. Head just distinct from the rest of the body, with 2 eyes. Eleven pairs of long radioles with short pinnulae; palmate membrane height, up to the extremity of the radioles. A fascicle of maximum 9 chaetae on each segment’s side, curved and enlarged towards the tip, with a highly stepped disposition with respect to each other. The author did not find thoracic chaetae or lateral/pygidial eyes, but he underlined that this may be due to a preservation bias. Pygidium with mamelon shape that the author believes to be the location of sight. Interesting behavioural observations seem related to this in particular, as the animal appears to be not sedentary, often exiting the tube just secreted and moving with the pygidium in front and the crown folded. Quatrefages reported the lifestyle of both his Myxicola species as being similar to Amphicorini’s species.

Myxicola pacifica Johnson, Citation1901 (The Polychaeta of the Puget Sound region. Proceedings of the Boston Society for Natural History). Type locality Puget Sound.

Body fusiform, with 9 thoracic and 58–88 abdominal segments, short and bi-annulated. Thoracic segments are hardly distinguishable from the abdominal ones. Fourteen pairs of radioles; very high palmate membrane (up to 3 mm from the tip). Largest individual with a body length of 60 mm and crown length of 21 mm. As for M. conjuncta, different types of thoracic chaetae are reported: a more abundant classical hooded chaeta, capillary and very slender and a fewer blunt, spinous chaetae with conical tip. Thoracic uncini with long manubrium, strong main fang and minute teeth. Abdominal chaetae minute and broadly hooded; abdominal uncini very small, with 2–3 teeth over the main fang.

Myxicola parasites Quatrefages, Citation1866 (Histoire naturelle des Annelés marins et d’eau douce. Annélides et Géphyriens. Librarie Encyclopédique de Roret. Paris). Type locality unknown.

Body cylindrical, of 20–22 mm length, brown, with 40 segments well defined; head well distinct from the rest of the body, forming a ring that brings the crown and two nuchal eyes. Nine radioles (not specified if pairs or not) separated each other by large festoon; pinnulae thin but long, coloured with live decise green (due to haemolymph). Palmate membrane is very thin and high (as in M. modesta, see above). Two lateral eyes each segment and 4 pygidial eyes.

Myxicola platychaeta Marenzeller, Citation1884 (Südjapanische Anneliden. II. Ampharetea, Terebellacea, Sabellacea, Serpulacea. Denkschriften der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien). Type locality Japanese Exclusive Economic Zone.

Body cylindrical, yellowish-reddish, the first segments tinged with garnet violet, with 82 segments (9 of which thoracic, one achaetous) slightly ringing. Crown 1/3 the length of the body, with 16 pairs of radioles, connected by a high palmate membrane, although the poor state of preservation makes it difficult to understand how far it extends). In the second thoracic chaetiger only hooded chaetae present, while from the third appear also broad, coarse and curved chaetae that the author considers equated to thoracic uncini of other Myxicola species, but without indentations. Abdominal uncini reported as an “actual hooked bristle”. No eyes observed.

Myxicola steenstrupi Krøyer, Citation1856 (Afhandling om Ormeslaegten Sabella Linn., isaer med Hensyn til dens nordiske Arter [Alternate title: Bidrag til Kundskab af Sabellerne]. Oversigt over det Kongelige danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Forhandlinger). Type locality Greenland; however, the same taxon was reported from the Bay of Fundy by Bush (Citation1905).

Body golden to orange in colour, stocky, 8 thoracic segments, longer than wide; 46–52 abdominal segments, shorter. Body total length of 2.5 inches and maximum width 1/6–1/7 of the body length. Crown long, more than 1/3 of the body length, with 17–21 pairs of radioles; long radiolar tip, almost 1/3 of the crown length. Pinnulae are very long and thin, rigid and wavy, up to 1/3 of the radiole length. Buccal cirri (probably dorsal radiolar appendages) sublaminar in shape, elongated-triangular, shorter than 1/16 of the radioles. Anus terminal. Chaetal brushes are poorly visible in the anterior part of the body and disappear in the posterior part. Chaetae are numerous but small and thin. Tori with uncini not found by the author.

The very poor description of M. villosa Koch, 1847, refers to the work of Giuseppe Meneghini already reported in a previous paragraph.

Myxicola viridis McIntosh, Citation1923, Type locality Atlantic Ocean, British Isles (A monograph of the British marine annelids. Polychaeta, Sabellidae to Serpulidae. With additions to the British marine Polychaeta during the publication of the monograph. Ray Society of London). Body green in colour, elongated, 8 thoracic segments, longer than wide; 39 abdominal segments. Crown with 9–14 pairs of radioles, which fold into a spiral when closed; strap-like short radiolar tip, different from the elongated one seen in M. infundibulum. Peristomium with triangular lobe similar to the one of M. infundibulum. Pygidium papilliform. Peristomial chaetal tuft directed obliquely outward; narrowly hooded chaetae, with thoracic ones larger than abdominal ones. Thoracic uncini acicular, with short and sharp main fang, markedly curved, with only one tooth above it. Abdominal uncini with long and sharp main fang, with one tooth above it long almost as the fang itself; basal posterior prolongation is present.

In addition, we decided to not rely on the description of M. monacis Chamberlin, Citation1919, Type locality Laguna Beach, California (holdfast of seaweed) (New polychaetous annelids from Laguna Beach, California. Journal of Entomology and Zoology of Pomona College), because of its poor quality and approximation of information.

Lastly, a problem of misspelling is present concerning M. sarsii, and M. sarsi. In the same work Kröyer (Citation1856), reports both taxa, considering M. sarsii a synonym for M. infundibulum and M. sarsi a valid species, and this is also reported in WoRMS. However, as already mentioned, a good description is present only for M. sarsii, whilst no description at all is available for M. sarsi. Moreover, Knight-Jones in Hayward and Ryland (Citation1990) listed M. sarsi as a species occurring in English waters. However, as no real description by Knight-Jones nor type specimens are present, the presence of this taxon remains uncertain (T. Darbyshire pers. comm.). In the present paper we have considered M. sarsii a valid species ().

Among the reported taxa synonymized with M. infundibulum we can recognize three groups based on the number of abdominal chaetigers: the first hosts species with a low number of chaetigers (70<)including M. affinis, M. grubii, M. modesta, M. parasites, M. viridis and M. steenstrupi; while M. pacifica, M. michaelseni and M. platychaeta possess an intermediate number (60–90 chaetigers) and only M. conjuncta has up to 100 or more chaetigers, similarly to M. infundibulum sensu Montagu. For most of the analysed species 8 thoracic chaetigers are reported; the exceptions are M. affinis, M. conjuncta and M. platychaeta with 9 thoracic segments. However, we believe that, as for the latter, the peristomium, achaetous, is included in the numeration.

A great variability in the number of radioles across the different species is also present. Here at least two groups can be recovered (we can take into account only the number reported for each species because is not uncommon for preserved materials to lose some body elements, such as the radioles): M. affinis, M. conjuncta, M. grubii and M. steenstrupi have 20 or more pairs of radioles, with a number oscillating between 20 and 24 pairs, while M. modesta, M. parasites, M. platychaeta, M. viridis and M. pacifica have all fewer than 20 pairs of radioles. In particular, M. affinis, M. viridis and M. conjuncta have a very low number of radioles reported, 11 pairs, 9 to 14 pairs, and 9 (not specified whether pairs) respectively, while M. michaelseni has up to 19 pairs of radioles, and probably can be inserted in the first group.

Only Augener and Krøyer took into account the crown/body length ratio, with 1/4–1/6 for M. michaelseni, 1/4 for M. grubii and more than 1/3 for M. steenstrupi, while for M. platychaeta, M. conjuncta and M. pacifica the lengths of the two body elements are reported, allowing us to calculate their ratio (1/3, 1/6 and 1/3, respectively); for all the other taxa no information was reported about this feature.

We must acknowledge that almost all the authors paused on the characteristics of crown, describing it more or less in detail; in this, the description by Augener is the most complete description of the structure of the lips and their appendages. Chaetae and uncini were also poorly described, with some descriptions reporting both thoracic and abdominal ones, and others with just the thoracic ones or without any references. The description of M. viridis is an exception, with both thoracic and abdominal uncini reported in great detail. In fact, M. viridis shows a peculiar abdominal uncinal shape, characterized by the presence of a basal posterior prolongation recalling a handle. It should be noted that for M. conjuncta and M. pacifica a set of shape-changing chaetae, new for the genus, is reported, while the description of M. platychaeta suggests the presence of acicular abdominal uncini. Good drawings of the chaetae are present also for M. affinis.

Generally, however, not all descriptions are accompanied by good illustrations.

The presence and disposition of eyes were described for M. michaelseni, M. modesta and M. parasites, with the former and the latter having the whole set of eyes on the body (nuchal, interramal/lateral and pygidial), while the second has only nuchal eyes. In any case, Augener is the only author who went in search of radiolar eyes, while for the last two species Quatrefages suggests the pygidium as the location of sight, as both taxa were observed moving outside the tube with the pygidium in front and crown folded behind. For M. modesta this should be supported by the mamelon shape of the pygidium.

Lastly, a very problematic situation concerns M. grubii, as the description from Kröyer (Citation1856) is not the product of the examination of new material, but is the direct copy of the description of a specimen from Trieste by Grube (Citation1855), identified as M. infundibulum. Grube (Citation1850) enstablished the genus Eriographis, without a clear definition (except for the occurrence of a mucus tube), and the species Eriographis borealis, without any description, which should be regarded as a nomen nudum (as already pointed out by Kröyer Citation1856). Subsequently, Grube (Citation1855) described the above-cited specimen from Trieste as M. infundibulum and stated its identity with E. borealis. Since the description reported a different taxon with respect to M. infundibulum and with E. borealis being a nomen nudum, Kröyer (Citation1856) gave the name of M. grubii to the specimens described by Grube, completely relying on this last author’s description.

Part II. Taxonomic account

Family Sabellidae Latreille, 1825

Genus Myxicola Koch in Renier, Citation1847

Type species Myxicola infundibulum Montagu, Citation1808

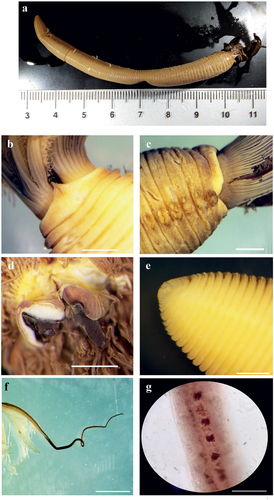

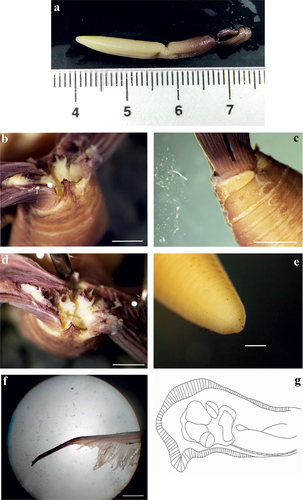

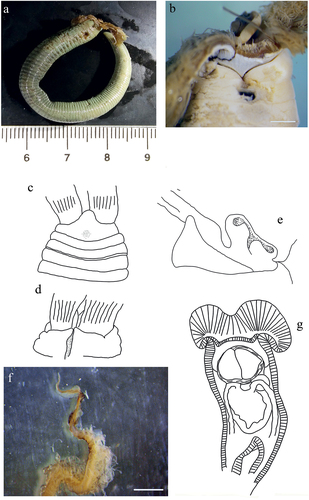

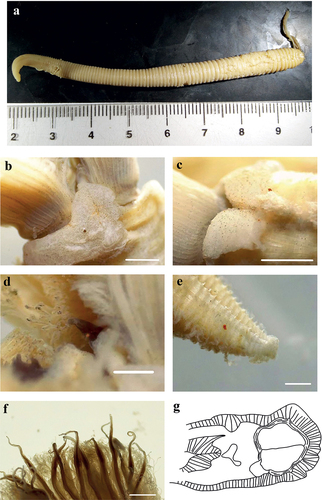

Myxicola sp. 1 ()

Figure 2. Myxicola sp. 1. (a) entire worm; (b) peristomial mid-lateral incision; (c, d) scheme of the peristomal ring: (c) ventral view; (d) dorsal view; (e) complex of ventral and dorsal lips; (f) radiolar tip; (g) scheme of radiolar section. Scale bars: b, f = 1 mm.

Figure 3. Myxicola sp. 1. (a) 1st setiger thoracic chaeta; (b) 4th setiger thoracic chaeta; (c) 24th abdominal chaeta; (d) 4th thoracic uncini; (e) 24th abdominal uncinus, lateral view and scheme of teeth above the main fang. Scale bar: 0.05 mm.

Material examined

1 individual collected from the British channel on the Cornwall coast [50°07′53.7″N, 5°03′46.2″W] 1989, intertidal, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and preserved in 70% ethanol (PCZL S.M. 2.1).

Description

Body yellowish (original colouration probably lost due to fixation), cylindrical but flattened dorso-ventrally (), 7 cm long, crown light brown measuring 1.9 cm, ratio between body and crown length 3.7. Nine thoracic chaetigers and 122 abdominal segments. Glandular girdle close to the posterior edge of the second thoracic chaetiger. Thorax longer than wide. Peristomium higher and triangular ventrally, gently decreasing laterally, leaving visible radiolar lobes and showing a mid-lateral incision that appears to split the same into a ventral and a dorsal half (). Dorsal lips with very short and club-like radiolar appendages, just protruding from the ventral lips, colour unknown (). Pinnular appendages absent; ventral radiolar appendages absent, ventral lips developed and enlarging, extending dorsoventrally along inner surface of base of radiolar lobes and connecting ventrally to the radiolar lobes by a sheet of tissue; parallel lamellae and ventral sacs absent. Crown holding 23 radioles on one lobe and 25 on the other. Despite the loss of colouration, the outer surface of the radioles shows a darker rachis, as well as a darker colouration of the inner surface of the whole crown; radiolar tip not darker than the rest of the radiole. Palmate membrane high, running up to the start of the radiolar tip extended into radiolar flanges of the radiolar tip, enlarging into auricles that wear thin along the same, giving it a triangular shape; radiolar tip blunt (), between 1/5 and 1/6 of the radiole length. Radiolar skeleton composed of 2 cells surrounded by a hyaline matrix, external margin bilobed (). Pinnulae thin, curly and short, around 1/9 of the radiole length, with rounded tip, disposed in strict alternation along the radiole; longer pinnulae located at the distal end of the first half of the radiole, and after decreasing gently in length. Radiolar eyes not visible. Peristomial eyes not visible. Neither interramal nor pygidial eyes visible. Numerous narrowly hooded thoracic notochaetae with long tip, disposed circularly to form a tuft; in the first chaetiger the chaetae are similar to the other thoracic chaetae, but with a shorter and slightly broader hood (). Thoracic uncini from second thoracic chaetiger, curved, with a long fang and a series of distinct small teeth in the first half (). Abdominal uncini with two large, distinct apical teeth, not reaching half of the main fang length; breast rounded, main fang shorter than the breast (). Abdominal neurochaetae narrowly hooded, almost identical to first chaetiger notochaetae ().

Remarks

The examined specimen is in a poor state of preservation, allowing us to analyse only some of the characters used for other specimens, and only the analysis and drawings of the individual performed by one of the authors (AG) in past years gave us access to the inner structures of the crown (lips height and radiolar appendages shape). For these reasons we have decided to not classify this specimen into a new taxon, until new, fresh materials can be examined.

The specimen was collected close to the type locality of M. infundibulum (sensu Montagu), but it seems to differ from the material collected by Darbyshire (Citation2019) in the same area, which shows a dark tip of radioles. Despite the absence of a description of uncini and chaetae, our specimen clearly groups with the other UK form indicated by Darbyshire, showing “white-tipped” radioles. However, an appreciable difference is present in the shape of the triangular lobe, which appears to be more developed in the material by Darbyshire. Comparing our material with the description of Montagu, the size is greatly different, with the specimen from Montagu being almost 3 times larger than our specimen. The same goes for the number of radioles (37 pairs against a maximum of 25). It can be hypothesized that our specimen is just a smaller individual, but the high number of segments (>130) makes it difficult to believe that the specimen was not an adult. Also, alteration of specimens due to preservation and fixation could explain morphometric variation, but it should only account for a shrinking near 50%. Moreover, the difference between our material and Montagu’s description is reinforced by the fact that in the description of Montagu, dark radiolar tips are reported, confirming that its material belongs to the “black-tipped” taxon reported by Darbyshire (Citation2019).

We wish to underline that important differences are also present comparing our material with the M. infundibulum description of Fauvel (Citation1927), in both qualitative aspects, such as the shape of peristomium, and quantitative aspects, such as the number of radioles, which is reported to be up to 40 pairs. However, the description and the drawings reported in Fauvel are quite unclear, and, as already mentioned, it probably is a mixture of characters from different taxa synonymized with M. infundibulum.

Lastly, differences from the other accepted species are based on the number of thoracic segments (9 compared with 3–5 for M. aesthetica and M. nana), the palmate membrane and radiolar tip (respectively, inconspicuous and characterized by lateral prolongations of the radiolar flanges terminating with a group of “hyaline cells” in M. fauveli), macroscopic radiolar eyes (present in M. ommatophora in subdistal position as well as acicular abdominal uncini), peristomial eyes and radiolar skeleton, respectively present and composed just by 1 row of hyaline cells in M. violacea, and thoracic uncini with a single tooth above the main fang in M. sulcata, as well as longer dorsal radiolar appendages.

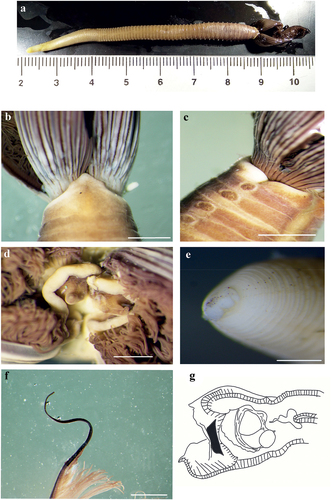

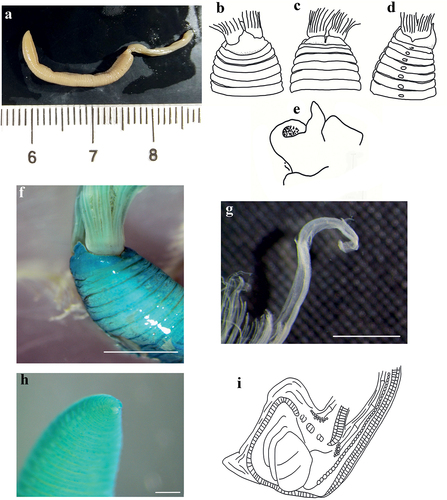

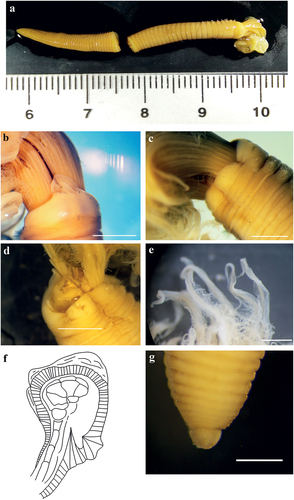

Myxicola sp. 2 ()

Figure 4. Myxicola sp. 2. (a) entire worm from Naples; (b, c) scheme of the peristomal ring: (b) ventral view; (c) lateral view; (d) complex of ventral and dorsal lips; (e) pygidium; (f) radiolar tip; (g) scheme of radiolar section. Scale bar: b, c = 2 mm; d, f = 1 mm, e = 0.5 mm.

Figure 5. Myxicola sp. 2. (a) 1st setiger thoracic chaeta; (b) 4th setiger thoracic chaeta; (c) 24th abdominal chaeta; (d) 4th thoracic uncinus; (e) 24th abdominal uncini, lateral and front view. Scale bar: 0.05 mm.

as Myxicola infundibulum (Eisig, 1910); (Gambi et al., Citation1982)

Material examined

3 specimens collected in the Gulf of Naples in the 1910 and identified as M. infundibulum by Eisig in the same year, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and preserved in 70% ethanol, Darwin Dohrn Museum of the Stazione Zoologica of Naples (Pol. 200, 1910/6/9 318), 3 additional specimens collected during 1985 from the same locality, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and preserved in 70% ethanol (PCZL S.M. 4.1).

Description

A quite markedly elongated body, cylindrical and yellowish in colour, crown light brown with darker tips (). The specimen measures 8.9 cm in body length with 1.65 cm of crown. Eight thoracic chaetigers and 100 abdominal segments. Thorax longer than wide. Glandular girdle close to the posterior edge of the second thoracic chaetiger. Peristomium 2.15 mm high, with an anterior fleshy triangular lobe, rounded, with a barely outlined tip, that divides the crown into two halves ventrally. High ventrally and dorsally, it remains high also laterally, maintaining a more squared shape and showing with a more rounded shape only near mid-lateral incision; junction between body and crown not visible (). Crown holds 23 pairs of radioles; ratio between body and crown length of 5.4. Dorsal lips with elongated, triangular-shaped radiolar appendages (), more flattened dorso-ventrally and with a thinning tip and purple colouration. Pinnular appendages absent; ventral radiolar appendages absent, ventral lips rounded and developed, but low, extending dorsoventrally along inner surface of base of radiolar lobes and connecting ventrally to the radiolar lobes by a sheet of tissue; parallel lamellae and ventral sacs absent. Radioles light in colour at the base of the radiole on the outer surface, becoming progressively dark (brown) especially at the radiolar tip (), connected by a lighter, semi-transparent palmate membrane that runs up to the start of the radiolar tip. Here it follows the radiolar tip, extending into radiolar flanges that give to the structure a quite markedly lanceolate shape. The radiolar tip of this taxon is quite short, with a rounded tip (1/8 of the radiole length). Pinnulae thin, between 1/4 and 1/5 of the radiole length, with rounded and slightly swollen end tip, disposed in pairs along the radiole; the longer pinnulae are located in the distal half of the radiole, then rapidly decrease in length towards the radiolar tip. Radiolar skeleton composed of 2 cells surrounded by a hyaline matrix, radiolar external edge rounded (). Peristomial eyes not visible. Interramal eyes not visible. Pygidium squared and papilliform, well developed antero-dorsally, pygidial eyes not visible (). Numerous narrowly hooded thoracic notochaetae with long tip, disposed circularly to form a tuft; in the first chaetiger the chaetae are similar to the other thoracic chaetae, but with a shorter and slightly broader hood (). Thoracic uncini curved, with a long main fang but no teeth observed above it (). Abdominal uncini showing one large tooth above the main fang, or two with one larger and longer than the other; two small teeth with one smaller apically to them are found rarely (). Breast rounded and long, without handle, main fang shorter than the breast. Abdominal neurochaetae narrowly hooded ().

Remarks

The specimens of this taxon all show a markedly elongated and cylindrical body shape, with the smaller, the medium and the larger specimens having, respectively, 94, 127 and 129 abdominal segments, for a body length from 8 to 12.5 cm. The crown shows a constant length, being 1.6 cm for the larger specimen and 1.7 cm for the smaller two. As a result, the mean ratio between crown and body length is 5.91 ± 1.26.

The description by Fauvel of M. infundibulum shares a set of macro-characteristics with the material from the Gulf of Naples here examined: a maximum length not exceeding 10 cm for fewer than 140 segments, a crown at least 3 times shorter than the body, radioles with purple rachis, high palmate membrane, some shading of darker colour towards the anterior end, and absence of macroscopic eyes; but, as we already pointed out, the description and the drawings reported in Fauvel (Citation1927) seem to be a mixture of characters from descriptions of different material from different sites, including that from the Gulf of Naples.

The presently analysed material comes from the same locality as the materials identified as M. infundibulum by Claparède (Citation1870) Lo Bianco (Citation1893), and Iroso (Citation1921). A comparison with their description shows many similarities arise: the specimens’ size is consistent, with Claparède reporting a length around 10 cm for 115–125 segments and 20 pairs of radioles, while Lo Bianco reported a length of 12 cm for 120 segments. Moreover, both reported 8 thoracic chaetigers. However, some differences can be found. For example, Claparède described the presence of interramal eyes; the absence of them in our material may be an artefact from long lasting in fixed status. Lo Bianco described a longer crown (2.5 cm vs 1.7 cm) and the absence of thoracic uncini and “bi-rostrate” abdominal uncini. We believe that the absence of thoracic uncini can be explained by the objective difficulty in finding them, as even with modern instrumentation they require a careful preparation of the slide to be observed, while the “bi-rostrate” status of the abdominal uncini is consistent with their appearance when lying on one side.

This taxon appears closer to the “black-tipped” one from English waters Darbyshire (Citation2019), sharing an elongated body shape and a decreased crown/body length ratio. However, it can be differentiated especially by the shape of the triangular lobe (clearly divided ventral-medially into sub-lobes), by the length of the radiolar tip (longer and tapering) and by the shape of the radiolar appendages (shorter and flattened dorso-ventrally). Moreover, in specimens from Naples, the colour of the crown is darker along most of its length, and not only on the tip of radioles. Differences can be found also with respect to Montagu’s description of M. cf. infundibulum, especially in size, number of segments and number of radioles. Lastly, other than the darker tip of the radiole, the shape of the triangular lobe distinguishes this taxon from the English “white-tipped” form.

Differences from the other accepted species are related to the number of thoracic segments, which separate this taxon from M. aesthetica and M. nana (8 vs 3–5); to the radiolar tip morphology and the absence of macroscopic eyes, which helps us to separate it from M. fauveli and M. ommatophora (showing, respectively, lateral prolongations of the radiolar flanges terminating with a group of “hyaline cells” and macroscopic radiolar eyes in subdistal position). The radiolar skeleton allows us to differentiate it from M. violacea (which shows just 1 row of hyaline cells), while thoracic uncini and lip structure separate it from M. sulcata (which has a single tooth above the main fang as well as longer dorsal radiolar appendages).

This taxon’s presence in the Gulf of Naples seems to be firm, since it has been collected from the mid-19th century to the late 20th, as other individuals were collected from Pozzuoli (Gulf of Naples, Campania, Italy) (40°48ʹ52.0”N, 14°09ʹ27.7”E), in 1985.

Although the examined features lead us to consider it a different species to M. infundibulum and probably a new taxon, we need fresh material to be collected before we can provide a good description and clarify its systematic position.

Myxicola cosentini Putignano et al. Citation2023 sp. nov.

as M. cf. infundibulum in Giangrande et al. Citation2012()

Holotype

Lake Faro [38.272318°N, 15.628438°E], 2007 collected at 0.5 m to 2 m, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and preserved in 70% ethanol. MNCN 16.01/19245.

Paratypes

9 specimens from the same locality, collected from 2007 to 2011. PCZL S. M. 7.1., one individual fixed in 96° ethanol for DNA analysis.

Description

Holotype complete, with body fully yellowish-light brown in colour, cylindrical, with peristomium slightly darker, crown darker especially on the tips (). The specimen measures 3.5 cm in body length, with 1.35 cm in crown length. Eight thoracic chaetigers and 90 abdominal segments. Glandular girdle close to the posterior edge of the second thoracic chaetiger. Thorax longer than wide. Peristomium 0.81 mm high, with an anterior fleshy triangular lobe, thin and divided into two slender tips by a median groove, that divides the crown into two halves ventrally. High ventrally and dorsally, it decreases laterally, showing the mid-lateral incision; junction between body and crown not visible (). Crown holds 18 radioles on one radiolar lobe and 20 on the other one; ratio between body and crown length 2.6. Dorsal lips with relatively long and club-like radiolar appendages of purple colouration. Pinnular appendages absent, ventral radiolar appendages absent, ventral lips less developed and low, extending dorsoventrally along inner surface of base of radiolar lobes and connecting ventrally to the radiolar lobes by a sheet of tissue; parallel lamellae and ventral sacs absent (). Radioles show purple rachis on the outer surface, light in colour at the base of the radiole and becoming progressively darker towards the tip, connected by a lighter, semi-transparent palmate membrane that runs up to the start of the radiolar tip. Here it follows the radiolar tip, extending into radiolar flanges that become progressively thinner, enhancing the extremely long and tapering appearance of the tip. Radiolar tip darker, long and filiform (<1/4 of the radiole length) (); a series of small, numerous eyespots are appreciable along the radiolar tips, disposed on the sides, up to the distal end (). Pinnulae thin, between 1/6 and 1/7 of the radiole length, with rounded tip, disposed in an alternate pattern along the radiole; the longer pinnulae are located in the distal half of the radiole, then rapidly decrease in length to the starting point of the radiolar tip. Radiolar skeleton composed of 2 cells surrounded by a hyaline matrix and with a bifurcate margin (). Peristomial eyes not visible. Interramal eyes visible from the fourth thoracic chaetiger, in the form of both single and paired eyespots; when in pairs the smaller one is posterior to the larger one. These shift into lateral eyes, as they move dorsally along the abdomen, increasing in number (up to 2–3 units each side) towards the pygidium and situated in a more dispersed way. In the segments immediately anterior to the pygidium, they increase both in number and in dispersion (up to 6 eyespots on each side). Pygidium antero-dorsally flat, with a disc-like shape, pygidial eyes not clearly appreciable (). Numerous narrowly hooded thoracic notochaetae with long tip, disposed circularly to form a tuft; in the first chaetiger the chaetae are similar to the other thoracic chaetae, but with a shorter and slightly broader hood (). Thoracic uncini curved, with few distinct teeth above the first half of the main fang (). Abdominal uncini showing either 2 long teeth above the main fang with one larger and longer than the other, or a single apical long tooth flanked by, at least, 2 small teeth each side slightly shorter than the main fang. Breast squared, main fang longer than the breast (), Abdominal neurochaetae narrowly hooded ().

Remarks

The size varies among individuals, from the smallest specimen of 2.25 cm body length and 1 cm crown length to 8 cm body length and 1.95 cm crown length in the largest, a mean value of 5.6 cm for the body and 1.6 cm for the crown. The ratio between body and crown length increases with size (from ½ to 1/5), but the relationship between increasing body and crown length remains similar (R2 = 0.83), excluding the only incomplete specimen (which is missing almost half of the body). Larger specimens show a higher number of segments than smaller ones, but some specimens had the very last segments damaged, making the relationship with size uncertain: the smallest specimen shows 70 segments, the largest 119 (although it may lack the very last setigers) while an intermediate one (e.g. 5.9 cm in body length) has 131 segments. Peristomium height increases linearly with body size (R2 = 0.83), with a mean length of 1.6 mm; the same goes for thorax length (R2 = 0.98). Crown holding an unequal number of radioles between radiolar lobes for all the specimens analysed; although this can be due to a poor state of preservation (loss of radioles), the sign of the presence of radioles, even if broken, was clear, making difficult to believe that this is not a state for this character peculiar to this species. The number of radioles increases with the size of specimens (R2 = 0.84), with the smallest having 16–17 radioles and the largest 20–23. No significant relationships between crown length, the length of the pinnulae and length of radiolar tip (with respect to the length of their radiole) were found in the statistical analysis.

This taxon shares with the “black-tipped” form of UK material (probably M. infundibulum s.s.) long and dark radiolar tips. However, the crown of M. cosentini is all darker in appearance; moreover, the continuation of the palmate membrane into radiolar flanges along the radiolar tip maintains a filiform aspect in the new taxon, while it is lanceolate in the English material. Further differences lie in the general shape of the animal, stockier and more flattened dorso-ventrally, and in the shape of the triangular lobe, which, despite being divided ventrally into two halves, is clearly longer and thinner. Lastly, the two forms differ in the shape of the radiolar appendages, which are longer and cylindrical in the new taxon. The size of the new taxon allows us to separate it also with respect to the original description of Montagu, while the shape of the triangular lobe and morphology of the radiolar tip differentiate it from the “white-tipped” English form.

The long radiolar tip clearly differentiates this species from all the other taxa collected along the Italian coast and examined in the present paper, as well as from M. sulcata; this feature, together with the whole structure of the radioles, differentiates this species also from M. fauveli and M. violacea. Finally, the absence of macroscopic radiolar eyes and the number of thoracic segments separate it from M. ommatophora, M. nana and M. aesthetica.

Comparison with the other new taxa presently described will be discussed in their respective Remarks sections.

Etymology

The species is named after Prof. Andrea Cosentino, who collected the specimens.

Distribution and ecology

Faro Lake, located within the Oriented Natural Reserve of Capo Peloro–Lago di Ganzirri (Ionian Sea), is a brackish-water environment connected to the Strait of Messina through open channels which is exploited for mollusc aquaculture. It shows ecoclines and environmental patchiness that make it highly exposed and attractive for allochthonous marine species. The area has therefore been cited as a hotspot for the entry and spread of alien marine species in the Central Mediterranean (Cosentino et al. Citation2009). In this environment have been reported the presence of the large-sized sabellid species Acromegalomma lanigerum (Grube, Citation1846), inhabiting the soft bottom at low depth with M. cosentinii sp. nov., Branchiomma boholense (Grube, Citation1878), inhabiting the hard bottom of the lake’s two seaward inlets and of the channel that connects the basin with the neighbouring lake of Ganzirri; and further observations of B. luctuosum.

Myxicola giuliae Putignano et al. Citation2023 sp. nov.

()

Holotype

Marina di Brindisi, Brindisi (Apulia, Italy) [40.659187°N, 17.963017°E] in March 2022 at 3–6 m depth and fixed in 70° ethanol. MNCN 16.01/19244.

Paratypes

7 specimens from the same locality and site, 4 of which lack the posterior part of the body. PCZL S.M. 5.2, two individuals fixed in 96° ethanol for DNA analysis; 1 specimen incomplete from the area of integral protection of Torre Guaceto MPA (Brindisi) [40.751067°N, 17.743967°E], collected he 15 September 2022 at 17 m depth and fixed in 70° ethanol (PCZL S.M. 5.3); 2 specimens (one incomplete) from Santa Caterina di Nardò [40.140614°N, 17.979802°E], collected the 11 September 2022 at 5–6 m depth and fixed in 70° ethanol (PCZL S.M. 5.4); 1 specimen incomplete from Mar Piccolo of Taranto [40.480487°N, 17.268607°E], collected the 13 October 2022 at 2–3 m depth and fixed in 70° ethanol (PCZL S.M. 5.6).

Description