Abstract

Bilateral gynandromorphism is a condition in which an individual has both male and female phenotypes distributed symmetrically on the body. We describe the first case of a likely gynandromorphic bearded tit, which was trapped in Poland. The bird had a black moustache and grey-blue plumage on the right side of the head, which is typical for males, and lacked this plumage coloration on the left side, which is typical of females. The entire bill was brown, consistent with a typical female, while the undertail coverts were buff with randomly distributed black spots, which represents a mixture feature of both sexes. The observation is discussed in light of earlier cases of gynandromorphic birds.

Introduction

Gynandromorphism is a rare phenomenon in which male and female features occur simultaneously within the same individual. In bilateral gynandromorphism, male and female plumages are distributed symmetrically on both sides of the body (Fusco & Minelli Citation2023). The right side is usually masculine while the left is feminine, which corresponds to the distribution of testis and ovary, respectively (Kumerloeve Citation1987). Avian gynandromorphs are male:female chimeras, which possess mainly ZZ or WZ chromosomes in cells on the respective side of the body (Zhao et al. Citation2010).

To date, bilateral gynandromorphism has been found in about 43 bird species (). Although usually described in Passerines (31 species), cases have also been recorded from the orders Anseriformes, Galliformes, Columbiformes, Coraciformes, Piciformes, Falconiformes and Psittaciformes (). The majority of wild gynandromorphic species (n = 40) have been recorded in Palearctic (50%) and Nearctic regions (20%; ; Newton Citation2003). The remaining 30% were recorded in Neotropical, Afrotropical, Australasian and Indomalayan regions (; Newton Citation2003). This geographical distribution of reported gynandromorphism in birds most likely reflects the tradition and intensity of ornithological studies. Typically, one case in a species has been described; however, multiple observations are also known (e.g. Rodríguez-Ruíz & Castro-Gutiérrez Citation2022). Our knowledge about the occurrence of gynandromorphism among avian taxa remains limited and incomplete because it is based on occasional observations with no systematic research.

Table I. Bird species in which gynandromorphic individuals have been recorded. Abbreviations: AFR – Afrotropical; AUS – Australasian; IND – Indomalayan; NEA – Nearctic; NEO – Neotropical; PAL – Palearctic region; cap – captive (Newton Citation2003). In references (below the table) we indicate the first record of gynandromorphism and observations after 1993.

Here, we describe the first record of a gynandromorphic individual in the bearded reedling (Panurus biarmicus, Panuridae, Passeriformes), a reed-dwelling, monogamous species, with a distinct dichromatism. Males have black, dropping “moustaches” on the cheeks, bright blue-grey heads and black under-tail coverts. Females lack moustaches and have buff-brown heads and buff under-tail coverts. Males have yellow-orange bills while those of females are brown (Cramp Citation1998; Svensson et al. Citation2010).

Methods

The unusual bird was captured during a ringing campaign conducted as part of a long-term project on the biology and ecology of the bearded reedling in southern Wielkopolska (western Poland; Stępniewski Citation1995, Citation2011, Citation2012; Surmacki and Stępniewski Citation2007; Surmacki et al. Citation2015). The bird was caught twice, on 25 and 29 September 2022, at Zgliniec fishery ponds (51°58’7.38”N, 16°43’11.98”E), in mist nets (40 x 2.5 m, mesh 16 mm). During the first capture, the following biometric measurements were taken: weight (0.01 g, spring balance), the right folded wing length (1 mm, ruler), the tail length (1 mm, ruler), and the right tarsus length (0.1 mm, calliper). All measurements followed the protocol issued by the Ornithological Station at the Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences (http://www.stornit.gda.pl). Plumage colour was assessed visually by JS who has vast experience with the species (has ringed 6798 individuals in basic plumage, http://www.stornit.gda.pl). According to skull pneumatization and iris colour, the bird was in the first year of life and had undergone the first basic moult (Wilson & Hartley Citation2006; Demongin Citation2016; Stępniewski unpublished data). The bird had no visible abdominal fat reserves. After taking photographs, the bird was marked with aluminium ring and released.

We prepared a list of species in which presumably gynandromorphic individuals have been recorded, based on reviews by Kumerloeve (Citation1987) and Patten (Citation1993). To update information from these sources, we searched Google Scholar and Scopus databases by entering the terms “gynandromorphic” and “bird”. We used bird taxonomy from the International Ornithological Committee (IOC) World Bird List (Version 13.1, https://www.worldbirdnames.org/new/).

Results

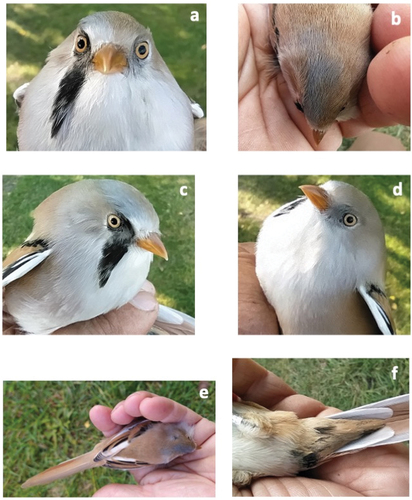

The most striking feature of the individual was the difference between the right and left sides of the head (). On the right side of the head there was a typical black moustache (). On closer inspection, individual brighter spots could be seen on it, especially in the lore area (). The crown was a blue-grey, forming a kind of a half-cup, which ranged from the forehead to the nape, where it faded (). Ear-coverts were buffish with just a hint of blue-grey (). The cheek behind the moustache was whitish (). In general, the right side of the head was brighter than that of a typical male. On the left side of the head, there was no sign of a moustache (), the ear-coverts were buffish and the cheek was white. The crown on the left side was tawny-brown, similar to the back of the crown ().

Figure 1. The bearded tit (Panurus biramicus) showing bilateral sexual plumage dimorphism. (a) head-on portrait, (b) upper part of the head, (c) right, male-like side of the head, (d) left, female-like side of the head, (e) upper part part of the body, (f) under-tail coverts.

The throat and the breast on both sides were almost pure white and the bill was uniformly brown (). The coloration of the back was plain tawny-brown, without any streaking (), while the undertail-covers were buff but with several black spots (). The coloration of the tail and wings was typical for adult bearded reedlings (; Cramp Citation1998).

Results of the biometric measurements were as follows: weight: 15.30 g; wing length: 64 mm; tarsus length: 24.3 mm; tail length: 83 mm, moustache length: 20 mm.

Discussion

Here, we report the first described example of a gynandromorphic bearded reedling, and also the first in the monotypic Panuridae family. Because bilateral gynandromorphism is very rare, new cases accumulate slowly. The last record of gynandromorphism in a new bird species was in 1993 (Patten Citation1993).

The described individual had some plumage characteristics that suggest that it was bilaterally gynandromorphic individual. The right side of the head had a black moustache and a blue-grey colour, which were completely absent on the left side of the head. A bird could be definitively categorized as possessing this abnormality on the basis of molecular analysis performed on genetic material from the two sides, e.g. feathers (Zhao et al. Citation2010). We did not collect feather samples for two reasons. First, we realized it could be a gynandromorphic bird only after we released the animal. Second, according to Polish law, prior approval from the Local Ethical Commission is required to collect tissue samples from protected species. Because we were not aware that we were dealing with a possibly gynandromorphic individual, we also did not measure both sides of the bird, which would have helped to assess bilateral sexual dimorphism in the skeleton (e.g. Abella Citation2002).

Most of the right side of the bird’s body displayed the typical male phenotype. According to Kumerloeve (Citation1987), this appearance is typical for avian gynandromorphs and has been recorded in 85% of cases. Some bilaterally gynandromorphic birds exhibit a sharp border line that demarcates male and female halves. Such a situation has been observed in a northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis, Peer and Motz Citation2014) and a black-throated blue warbler (Setophaga caerulescens, Patten Citation1993). In other cases, however, the difference between sides is blurred to some extent. For example, in a gynandromorphic black redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros), the right side of the bird had a typically male appearance, while the left was a mixture of female and male features but appeared female dominant (Martinez Citation2020). A similar variant of gynandromorphism was described in an evening grosbeak Hesperiphona vespertina, Laybourne Citation1967). Sometimes particular body parts are divided into male and female halves, while others are not. For example, in the northern cardinal described by Jones and Bartlett (Citation2017), there was a sharp demarcation on the breast, belly, and undertail coverts, whereas the entire head was consistent with a female. Even in birds with a clear demarcation of sides, some subtle phenotypes specific to one sex may be present on the other side (e.g. Patten Citation1993; Graves Citation1996; Abella Citation2002).

The distribution of sex-specific plumage characters in this bearded tit seems to be a mixture of all variants of the gynandromorphism described above. Although the male moustache and blue-grey head occurred on the right side, the entire bill was horn-brown, a feature consistent with typical bearded tit females (Cramp Citation1998). Moreover, the undertail-coverts were mainly buff; however, there were also some scattered black feathers. Thus, this plumage region was a mixture of female and male characteristics with a predominance of the former. Moreover, even the most typical of the male traits were somewhat subdued. The moustache was brighter than is typical of males in the studied population. Moreover, the blue-grey hood was smaller than in typical males, as it usually extends almost to the moustache tip and covers the cheeks (Cramp Citation1998; Svensson et al. Citation2010).

Further studies are needed to elucidate the occurrence and variation of bilateral gynandromorphism over avian taxa. One source of data that is not yet fully explored is specimens in museum collections (e.g. Laybourne Citation1967; Jones & Bartlett Citation2017). Finally, more anatomical and genetic analyses are needed to explain the phenotypic variation of bilateral gynandromorphism in birds.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Lynn Siefferman for her valuable comments on an early version of the manuscript and her help with language revision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abella JC. 2002. Capture of two probable gynandromorphic House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) in NE Spain. Revista Catalana d’Ornitologia 19:25–29.

- Agate RJ, Grisham W, Wade J, Mann S, Wingfield J, Schanen C, Palotie A, Arnold AP. 2003. Neural, not gonadal, origin of brain sex differences in a gynandromorphic finch. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 100(8):4873–4878. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0636925100.

- Brenner SJ, DaRugna OA, McWilliams SR. 2019. Observations of certain breeding behaviors in a bilateral gynandromorph Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 131:625–628. DOI: 10.1676/18-179.

- Brown P. 2015. Rose-breasted Grosbeak Bilateral Gynandromorph. Bird Observer 43:316–318.

- Cramp S. 1998. The Complete Birds of the Western Palearctic on CD-ROM. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DaCosta JM, Spellman GM, Klicka J. 2007. Bilateral gynandromorphy in a White-ruffed Manakin (Corapipo altera). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119(2):289–291. DOI: 10.1676/06-093.1.

- Demogin L. 2016. Identification guide to birds in the hand. Beauegard-Vendon: Beauegard-Vendon, Laurent Demongin

- Fusco G, Minelli A. 2023. Descriptive versus causal morphology: Gynandromorphism and intersexuality. Theory in Biosciences 142(1):1–11. DOI: 10.1007/s12064-023-00385-1.

- Graves GR, Patten MA, Dunn JL. 1996. Comments on a probable gynandromorphic Black-throated Blue Warbler. The Wilson Bulletin 108:178–180.

- Jones AW, Bartlett HT. 2017. A bilateral gynandromorph Northern Cardinal from South Bass Island. Ohio Biological Survey Notes 7:14–16.

- Kumerloeve H. 1987. Le gynandromorphisme chez les oiseaux-recapitulation des données connues. Alauda 55:1–9.

- Laybourne RC. 1967. Bilateral gynandrism in an Evening Grosbeak. Auk 84(2):267–272. DOI: 10.2307/4083196.

- Martinez N. 2020. Observations on a presumed bilateral gynandromorph Black Redstart Phoenicurus ochruros paired with a male. Ornis Svecica 30:31–37. DOI: 10.34080/os.v30.20412.

- Mas R. 2013. Observation of a possible gynandromorph House Sparrow Passer domesticus in Mallorca (in Spanish with English summary). L’Anuari Ornitològic de les Balears 28:7–10.

- Morris KR, Hirst CE, Major AT, Ezaz T, Ford M, Bibby S, Doran TJ, Smith CA. 2018. Gonadal and endocrine analysis of a gynandromorphic chicken. Endocrinology 159(10):3492–3502. DOI: 10.1210/en.2018-00553.

- Muñoz-Gil J, Marín-Espinoza G, Pacheco N, Zavala-Marcano R. 2015. Ginandromorfismo bilateral en Agapornis sp. (Psitaciformes: Psittaculidae). The Biologist (Lima) 13:161–163.

- Newton I. 2003. The speciation and biogeography of birds. London, UK: Academic Press.

- Patten MA. 1993. A probable bilateral gynandromorphic Black-Throated Blue Warbler. The Wilson Bulletin 105:695–698.

- Peer BD, Motz RW. 2014. Observations of a bilateral gynandromorph Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 126:778–781. DOI: 10.1676/14-025.1.

- Rodríguez-Ruíz ER, Castro-Gutiérrez SB. 2022. Un caso de ginandromorfía en el Cardenal Norteño (Cardinalis cardinalis) en México, con una revisión de otros casos en Norteamérica. Ornitología Colombiana 21:30–37. DOI: 10.59517/oc.e544.

- Stępniewski J. 1995. Ausgewählte Aspekte der Brutbiologie der Bartmeise Panurus biarmicus: Beobachtungen am Loniewskie See in West-Polen. Vogelwelt 116:263–272.

- Stępniewski J. 2011. Liczebność, rozmieszczenie i siedlisko lęgowe wąsatki Panurus biarmicus na Jeziorze Łoniewskim w Wielkopolsce w latach 1986–2011 (in Polish with English summary). Ornis Polonica 52:247–254.

- Stępniewski J. 2012. Biologia lęgowa wąsatki Panurus biarmicus na Jeziorze Łoniewskim w latach 1987–2009 (in Polish with English summary). Ornis Polonica 53:233–248.

- Surmacki A, Stępniewski J. 2007. Do weather conditions affect the dynamics of bearded tit Panurus biarmicus populations throughout the year? A case study from western Poland. Annales Zoologici Fennici 44:35–42.

- Surmacki A, Stępniewski J, Stępniewska M. 2015. Juvenile sexual dimorphism, dichromatism and condition-dependent signaling in a bird species with early pair bonds. Journal of Ornithology 156:65–73. DOI: 10.1007/s10336-014-1108-y.

- Svensson L, Grant PJ, Mullarney K, Zetterström D. 2010. Collins bird guide: The most complete guide to the birds of Britain and Europe. 2nd ed. London: Harper Collins.

- Weggler M. 2005. Sexualverhalten und Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit eines wahrscheinlich gynandromorphen Hausrotschwanzes Phoenicurus ochruros (in German with English summary. Ornithol Beob 102:145–152.

- Wilson J, Hartley I. 2006. Changes in eye colour of juvenile Bearded Tits Panurus biarmicus and its use in determining breeding productivity. Ibis 149:407–411. DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00630.x.

- Zhao D, McBride D, Nandi S, McQueen HA, McGrew MJ, Hocking PM, Lewis PD, Sang HM, Clinton M. 2010. Somatic sex identity is cell autonomous in the chicken. Nature 464:237–243. DOI: 10.1038/nature08852.