ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: This study aims to examine how internalized stigma differs in opioid use disorder (OUD) based on sociodemographic and clinical variables, and to what extent internalized stigma is related to treatment motivation, perceived social support, depression, and anxiety levels.

METHODS: One hundred forty-five individuals with OUD included. Sociodemographic and clinical data form, the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI), Treatment Motivation Questionnaire (TMQ), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory were utilized in the study to collect data. Bivariate and partial correlation coefficients between variables were computed. ISMI and TMQ scores were compared between patients with depressive symptoms and patients without depressive symptoms by using t-test and Mann Whitney U test.

RESULTS: Internalized stigma was high among male patients with heroin use disorder. There was a positive correlation between internalized stigma score and treatment motivation, depression, and anxiety levels. On the other hand, there was a negative correlation between internalized stigma score and multidimensional perceived social support.

CONCLUSION: Internalized stigma occupies an important place in the treatment of OUD, which occurs with frequent relapses and which is hard to treat. Not only application for treatment but also adherence to treatment and treatment motivation at maintenance phase bestow a complicated relationship with depression and anxiety. In the struggle against internalized stigma, it plays a vital role to mobilize people’s social support systems, to educate families on the issue and to get in touch with support units exclusive to heroin users.

Introduction

Stigma is a multidimensional construct with different types including public, perceived, enacted, and internalized stigma, which are described by different researches [Citation1]. Stigmatization is an assignment of negative perceptions to an individual because of perceived difference from the population at large. Being a member of an ethnical group, having a disability, and substance use are among the common possible reasons of stigmatization [Citation2].

Internalized stigma refers to an individual’s adoption of negative stereotypes in the society, and as a result, retreating themselves from the society due to negative feelings, such as unworthiness and embarrassment [Citation3]. Although there are some studies in the literature suggesting that internalized stigma appears prior to public stigma and most of the time internalized stigma emerges independently from public stigma, there are also studies which argue that public stigma leads to internalized stigma [Citation4].

Initial studies on stigma were carried out on public stigma. Recently, in the fight against stigma, it has been understood that internalized stigma is a more accessible field, which is easier to study. Therefore, measurement tools are being developed and the target has been shifted to this field of research [Citation5,6].

Psychiatric patients are extremely sensitive to both public stigma and internalized stigma and effects of stigmatization on patients with various diagnoses have been studied extensively. In a study on patients with schizophrenia, both internalized stigma and insight to illness were positively correlated with suicidality [Citation7]. In other studies, internalized stigma was found to be correlated with severity of psychiatric symptoms while it reduced with adherence to treatment and control of symptoms [Citation8–14]. In patients with depression, symptom severity also correlated with internalized stigma [Citation12,Citation15–17]. According to those studies, it may be important to tackle patient’s internalized stigma in order to handle treatment of psychiatric disorders because internalized stigma impairs treatment compliance, insight, social interaction, and life quality of patients.

Substance use disorder (SUD) is among the most highly stigmatized psychiatric disorders. Indeed, some researchers consider the categorization of alcohol–SUD as a mental illness to be a stigma itself [Citation4]. Partly reflecting those concerns, in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [Citation18], the term “addiction” was removed because it was believed that it is a vogue term causing negative connotations in individuals and society; instead, a new term “substance use disorder” (which was envisaged to be a more neutral term) was used.

Studies which tackle internalized stigma in SUD from multiple aspects are quite limited. It has been shown that treatment-seeking patients’ beliefs on morality and immorality are associated with more internalized stigma and greater social distance [Citation19]. There are also some studies which indicate that healthcare professionals consider OUD as a moral and behavioural problem rather than as an illness [Citation20,Citation21]. Several studies have identified internalized stigma as a significant barrier for accessing healthcare and substance/alcohol use treatment services [Citation22].

Under the light of this literature, it is believed that internalized stigma is of significant importance in management of OUD. In this study, we aimed at examining internalized stigma in OUD from multiple angles. For this purpose, we evaluated the relationship between internalized stigma and treatment motivation in individuals with OUD. Furthermore, we examined internalized stigma’s relationship with social support, depression, and anxiety symptoms.

Method

Sample of the study

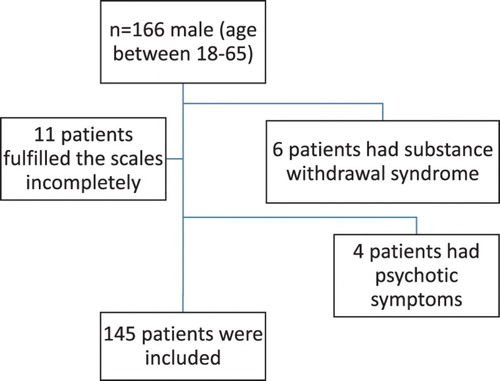

The study sample consisted of 166 consecutive male patients (aged 16-65) who received outpatient treatment at the Ankara Numune Research and Training Hospital's Alcohol and Substance Addiction Treatment and Research Center (ASATRC) Outpatient Clinic between November 2014 and March 2015. were evaluated for potential inclusion. The final sample of the study consisted of 145 patients (). The Ethical Board of Ankara Numune Training and Research Hospital approved the study with the number E14-296 on 17 September 2014.

Psychological scales

Sociodemographic and clinical data form

This form is composed of 15 questions aiming to identify sociodemographic and substance use characteristics. This descriptive information form includes questions regarding demographic features such as age, gender, profession, occupation, education and income levels, marital status, place of residence and cohabitation, and questions regarding clinical variables such as substance use duration, prior treatment/admission at ASATRC and previously received treatments.

The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale

The scale which was developed by Ritsher et al. is a 29-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure internalized stigma. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version were tested and confirmed by Ersoy [Citation9]. The scale is composed of five subscales (Alienation, Perceived Discrimination, Social Withdrawal, Stereotype Endorsement, and Stigma Resistance) and it measures people’s subjective experiences of stigma. Items of “Stigma Resistance” are reverse coded. The total score of Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) Scale (which is obtained by adding up points of five subscales) ranges from 4 to 116. High scores in ISMI Scale indicate that individual’s internalized stigma is negatively more severe [Citation9].

Treatment Motivation Questionnaire

Treatment Motivation Questionnaire (TMQ) is a 26-item self-report questionnaire which measures the reasons of each case for participating and pursuing an alcohol/SUD treatment. Factorial analyses show that the questionnaire has four identifiable factors called internalized motivation, external motivation, interpersonal help-seeking, and confidence in treatment. The reliability and validity of Turkish version of TMQ in alcohol dependents were carried out by Evren et al. [Citation23].

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a 12-item scale which measures the extent to which individuals assess social support from three sources. The scale is composed of four items in each of the three groups, which are family, friends, and significant others (prospective spouse, dated person, relative, neighbour, doctor, etc.).

Beck Depression Inventory

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) measures physical, emotional, cognitive, and motivational symptoms experienced in depression. It was developed by Beck et al. in 1961 and validity and reliability studies regarding its Turkish version were carried out by Tegin in 1980 and by Hisli in 1989. In this study, the cutoff was determined as 17, and it was reported that scores equal to or above 17 in the BDI could differentiate, with 90% accuracy, the depression which requires therapy.

Beck Anxiety Inventory

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was developed by Beck et al. in 1988 and its Turkish translation was offered by Ulusoy et al. for use. It is a self-report scale which is used to determine the frequency of anxiety symptoms experienced by individuals.

Statistical analysis

Shapiro–Wilk test was used as the normality test. Continuous variables were compared using Student t-test and Mann–Whitney U test when the data are not normally distributed. Correlations between variables were tested using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients. Partial correlation coefficient was calculated while controlling depression on the relationship between internalized stigma and treatment motivation. A p-value <.05 was considered as significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS ver.23.0.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

and show the demographic and clinical characteristics of the individuals with OUD. The mean age of patients who participated in the study was 23.7 ± 5.5 ( and ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of heroin users.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of heroin users.

While 77 patients (53.1%) met only heroin use disorder diagnostic criteria within the last year, the remaining 68 patients (46.9%) were using amphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, and synthetic cannabinoids occasionally (not regularly) in addition to heroin.

It was found out that 97 of the patients (66.9%) had previously applied to ASATRC for treatment, and 37 of the patients had been admitted to ASATRC as inpatients. Twenty-one patients had received inpatient treatment once; 16 patients had received inpatient treatment twice.

ISMI, TMS, MSPSS, BDI, and BAI scores of patients

It was found that mean ISMI Scale score was 81.3 ± 15.3 (40–113), the mean score of Alienation subscale was 18.1 ± 4.3 (6–36), the mean score of Stereotype Endorsement subscale was 18.5 ± 4.6 (7–28), the mean score of Perceived Discrimination subscale was 13.6 ± 3.8 (5–26), the mean score of Social Withdrawal subscale was 16.84 ± 4.52 (6–24), and the mean score of Stigma Resistance subscale was 14.41 ± 2.49 (7–20).

In terms of treatment motivation, the mean score of TMQ was 72.6 ± 14.4 (24–96), the mean score of internalized motivation subscale was 36.9 ± 8.9 (0–44), the mean score of external motivation was 8.2 ± 3.3 (0–16), the mean score of interpersonal help-seeking subscale was 14.5 ± 5.5 (0–24), and the mean score of confidence in treatment subscale was 13.1 ± 4.1 (3–20).

It was detected that the mean score of MSPSS was 55.4 ± 16.8 (14–84), the mean score of family social support subscale was 24.03 ± 5.19 (4–28), the mean score of friends social support subscale was 15.9 ± 7.8 (4–28), and the mean score of significant others social support subscale was 15.5 ± 8.6 (4–28).

It was observed that the mean score of BDI was 25.5 ± 12.9 (0–57), and the mean score of BAI was 29.8 ± 15.9 (0–63). When depression symptoms were evaluated based on cutoff 17, it was found out that 111 subjects showed depression symptoms to the extent of requiring therapy.

The relationship between sociodemographic and clinical data with internalized stigma scores

Our study revealed that internalized stigma is high among male patients with OUD. It was found that the overall score of stigma is higher in patients with low income (81.4 ± 16.1, p = .144). It was shown that overall stigma scores of patients who do not have any employment history were higher compared to those who have regular jobs (83.8 ± 13.9, p = .863); and the stigma resistance of the former was low (13.9 ± 2.8, p = .607). However, the differences between sociodemographic data and overall scale and subscale scores for internalized stigma in mental illnesses were not statistically significant. In terms of clinical variables, it was found that overall scores of alienation were significantly lower in patients who have not applied to ASATRC before compared to those who have applied.

The relationship between ISMI Scale and TMQ scores

There was a positive relationship between Alienation and overall score for TMQ, subscales of internalized motivation, interpersonal help-seeking; between Stereotype Endorsement and overall score for TMQ, subscales of internalized motivation, external motivation, interpersonal help-seeking; between overall score for TMQ and subscales of internalized motivation, external motivation, interpersonal help-seeking; between social withdrawal and overall score for TMQ, subscales of internalized motivation, external motivation, interpersonal help-seeking; between Stigma Resistance and subscale of confidence in treatment; and between overall score for ISMI Scale and overall score for TMQ, subscales of internalized motivation, external motivation, interpersonal help-seeking ().

Table 3. The relationship between ISMI Scale and TMQ scores.

Positive correlation was found between overall score for internalized stigma scale in patients with depression and overall score for TMQ (p = .001, r = 0.314). It was observed that when depressive state was under control, there was still a positive correlation between internalized stigma and treatment motivation even though power of the correlation was weak (p = .001, r = 0.267).

The relationship between ISMI Scale and MSPSS scores

There was a weak significantly negative relationship between overall score for MSPSS and subscales of social support from friends, social support from significant others; between Stereotype Endorsement and overall score for MSPSS, subscales of social support from friends; between Perceived Discrimination and overall score for MSPSS, subscales of social support from friends and social support from significant others; between Social Withdrawal and overall score for MSPSS, subscales of social support from friends and social support from significant others; between Stigma Resistance and overall score for MSPSS, subscale of social support from significant others; and between overall score for ISMI Scale and overall score for MSPSS, subscales of social support from friends and social support from significant others ().

Table 4. The relationship between ISMI Scale and MSPSS scores.

The relationship between ISMI Scale and BDI and BAI scores

There was a positive relationship between overall score for ISMI Scale as well as its subscales and BDI and BAI scores ().

Table 5. The relationship between ISMI Scale and BDI and BAI scores.

Subjects were divided into two groups as those “who have depression symptoms” and those “who do not have depression symptoms” according to BDI 17 cutoff criterion, and scores for ISMI Scale for both groups were presented in .

Table 6. The relationship between ISMI Scale and depression symptoms.

Discussion

The relationship between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and internalized stigma

In our study, it was revealed that internalized stigma was high among male patients with OUD. This finding is consistent with previous studies in the literature [Citation4]. However, the number of related studies in this field is limited. Although it may seem as a limitation to have only male patients with OUD in the sample of the study, it is however a nice representation of the society because it is well known that the majority of individuals with opioid use disorder in the society are men. This situation can be associated with the fact that men with OUD are perceived to be more aggressive and dangerous compared to women, thus experiencing more public stigma. There is a strong need for studies which examines the role of gender in internalized stigma in OUD.

It was also observed that income levels of patients were low and less than half of them continue to work; therefore, the overall stigma scores of patients who had low income and who did not have any employment history were found to be higher. This is an indication of the fact that perception of stigma has impacts on individual’s status in the society, individual’s social functioning, and eventually the income. However, the relationship between these economic and sociodemographic characteristics of patients and internalized stigma was not found statistically significant in this study. These results are consistent with many studies in the literature [Citation8,Citation12,Citation16,Citation24].

Although not statistically significant, it was found that alienation scores of patients who did not apply to ASATRC before were significantly higher compared to those who had ASATRC history. It is not surprising to see that individuals with SUD who are highly likely to alienate themselves from society are less willing in terms of treatment and getting help from ASATRC. On the other hand, it is suggested that treatment process increases labelling and thus, internalized stigma. One of the significant examples which can be given for this suggestion is that methadone treatment (which is marketed with big hopes) has not attracted the expected attention, and patients with SUD who have this treatment usually keep their treatment as a secret [Citation25,Citation26].

When six dimensions (concealability, disruptiveness, course, peril, aesthetics, and origin, which play important roles in individual’s sensitivity to stigma) are analysed, it is possible to mention that individuals with SUD meet these criteria. Heroin use turns into an addiction and a chronic process in a short time, and its concealability gets even harder at the same speed. The efforts of patients, who show decreasing self-care, shrinking social environment, and withdrawal symptoms time to time, are most of the time insufficient in concealing their OUD. Society perceives such people as dangerous and unpredictable, and puts the blame on their moral and personality traits for their actions. All these increase public stigma even more. People’s existence abilities at social, occupational and economic levels, which are considered to be the most effective factors in stigma, are the ones which individuals with opioid use disorder frequently and rapidly lose [Citation4].

In a study on patients with alcohol use disorder and their relatives carried out by Arıkan et al. in 2004, it was shown that patients’ relatives considered OUD more as a personality problem; both patients and their relatives perceived substance use as a moral weakness and personality shortcoming; however, it was concluded that the increase in the number of inpatients decreased this perception [Citation27].

The relationship between treatment motivation and internalized stigma

It has been shown in many studies that internalized stigma jeopardizes the adherence to the treatment [Citation28]. In our study, it is presupposed that treatment motivation has an important role in adherence to the treatment and the increase in stigma can hinder treatment motivation. However, a positive relationship between internalized stigma and treatment motivation was not found in the current study. This finding which may seem as a contradiction can be explained with transtheoretical model of change which posits that there are five stages of behavioural change in SUD, namely precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance [Citation29,Citation30]. In a limited number of studies carried out in this field, similar to our findings, it has been established that individuals with SUD are initially very eager and motivated for treatment. However, it has been shown that their eagerness and motivation decrease with the onset of treatment process; the chances of their maintenance with the treatment in long term and getting positive results are quite low [Citation31,Citation32]. Most of the time, such people get stuck in the preparation stage in which they think that change would be useful for themselves and they would try to change later on; therefore, most of the time, action and maintenance stages do not follow this stage [Citation33]. In maintenance stage, being ready for change becomes a more important concept than being ready for the treatment. Our study involved patients with heroin use disorder who applied to ASATRC, or in other words, who were already in the stages of preparation and action. Therefore, there was a positive relationship between treatment motivation levels and stigma levels. It is worth pursuing a further study which examines to what extent these patients’ motivation levels change in their long-term follow-ups, or in other words, in the maintenance stage, and its relationship with stigma. As a matter of fact, some studies show that there is a negative relationship between change readiness and internalized stigma [Citation34].

Furthermore, it has been found that social, psychological, and physical negative consequences of alcohol/substance use were associated with the likelihood of behaviour change in OUD and motivation for change during treatment [Citation33]. Even though lack of motivation is considered to be a sign in depressive disorder, in a limited number of studies, it was shown that treatment motivation of patients with depressive disorder was high compared to those who did not have depressive disorder [Citation35–37]. The reason for this could be that individuals start to regard their OUD as the cause of the negative consequences they experience, and for this reason their motivation for treatment increases. In our study, it was shown that social problems such as education, low income level, unemployment, and psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, and stigma were high among patients; therefore, it could be suggested that this could have caused high levels of treatment motivation. It was observed in our study that when depressive condition was under control, there was a similar positive relationship between internalized stigma and treatment motivation. This suggests that internalized stigma increased treatment motivation independently from depression status. However, these patients’ treatments were interrupted frequently and they continued to use substances time to time; therefore, their motivation did not remain consistent in a way to cause a significant behavioural change.

In various studies, it has been shown that internalized motivation is more effective on long-term change than external motivation [Citation33]. Even among those who were legally forced to receive treatment, awareness of the problems related to the substance use determined high participation level into the treatment [Citation33]. When internalized and external motivations exist together, the success of treatment is much higher. For individuals with SUD, external motivation could emerge due to pressure from social circle, law force, and public stigma. It can be thought that when such individuals internalize public stigma, their internalized motivation increases. For this reason, as stigma and perception of stigma increase, levels of internalized and external motivations could increase.

As observed in clinical practice, treatment motivation of individuals with OUD is greatly related to their thinking that they could get rid of their OUD painlessly and effortlessly by using painkillers, muscle relaxants, and a combination of buprenorphine plus naloxone. However, OUD treatment process is not always as comfortable as patients expect. It is commonly observed in ASATRC that individuals with OUD who are motivated for treatment and admission to the clinic in the beginning often demand discharge or leave the clinic without permission shortly after they have admitted to the clinic because of craving withdrawal symptoms and severe pain.

Social withdrawal observed in individuals with OUD increases due to discrimination and stigma they experience. Therefore, individuals may tend to use substances due to the lack of relationship and communication with other people even though they could be in great need for it. On the other hand, their need to establish relationships with the society still continues. This undesirable situation may in turn lead them to treatment and increase their treatment motivation at initial stage.

The relationship between perceived social support and internalized stigma

In our study, a negatively significant relationship was found between internalized stigma and perceived social support. This result is consistent with the study of Livingston and Boyd [Citation8] on people living with mental illness in which it was found that there was a negative relationship between internalized stigma levels and self-esteem, self-efficacy, quality of life, hope, and social support [Citation8] as well as with a study carried out in Turkey in 2013 examining the relationship between internalized stigma in psychiatric inpatients and perceived family support, which showed a strong negative correlation between internalized stigma levels and perceived family support.

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) are of significant importance in terms of social support systems for alcohol and substance users. It has been shown that in a three-year longitudinal study, alcohol users who continued to attend AA stayed sober 35% more in a year than compared to those who did not, and also decreased their drinking by 16% [Citation38].

It is expected to see a decrease in internalized stigma as the perceived social support increases in opioid users. Therefore, it is vital to obtain the family support for people with OUD and to include other social support systems, to decrease internalized stigma and to increase adherence to the treatment.

The relationship between symptoms of depression and anxiety and internalized stigma

In our study, it was observed that depression and anxiety symptoms are high in patients with OUD and it was established that they were positively associated with internalized stigma. There are a limited number of studies in literature which examine the relationship between internalized stigma and anxiety levels. In related studies which included patients diagnosed with psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, and depressive disorder, a positive relationship between anxiety level and internalized stigma was found. It is possible to see that people living with OUD are more prone to think that, similar to the general belief of the society, the situation they are facing results from their mistakes, and they blame themselves for this. This way of thinking increases the already experienced public and internalized stigma even more. In addition, such people may turn the feeling of hate resulting from stigma into depression symptoms such as embarrassment, pessimism, and unworthiness, and in this way they may, in a way, avoid the effects of hate [Citation39]. Therefore, as the feeling of stigma increases, the symptoms of depression and anxiety increase, as well. Consequently, our study conforms to the previous studies in the literature [Citation15,Citation40–42].

Our study group consists of only male outpatients because of its cross-sectional design and characteristics of our patient population in Ankara Numune ASATRC as a limitation. Study design with a larger participation could enable one to explore gender differences and differences between inpatients and outpatients.

Conclusion

There has not been a study in the literature examining the relationship between internalized stigma and relevant variables in patients with OUD in Turkish society so far. This is the first study carried out on this subject, in Turkey. Furthermore, we are of the opinion that this study proves itself to be valuable in terms of offering a different perspective for the relationship between stigma and treatment motivation.

All the results show that internalized stigma occupies an important place in the treatment of OUD, which occurs with frequent relapses and which is hard to treat. Not only application for treatment but also adherence to treatment and treatment motivation at maintenance phase bestow a complicated relationship with depression and anxiety. In the struggle against internalized stigma, it plays a vital role to mobilize people’s social support systems, to educate families on the issue and to get in touch with support units exclusive to individuals with OUD.

It seems possible to increase the success of OUD treatment by understanding the nature of internalized stigma and developing treatment strategies aiming at reducing this perception. In this regard, more studies need to be carried out in this field and a great deal of effort should be put in adjusting stigma and perception of stigma in an effective way at a practical level.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Sarkar S, Balhara YPS, Kumar S, et al. Internalized stigma among patients with substance use disorders at a tertiary care center in India. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2017: 1–14. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2017.1357158

- Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall; 1963. p. 6–7.

- Park SG, Bennett ME, Couture SM, et al. Internalized stigma in schizophrenia: relations with dysfunctional attitudes, symptoms, and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. 2013;205(1):43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.08.040

- Vogel DL, Bitman RL, Hammer JH, et al. Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60(2):311. doi: 10.1037/a0031889

- Tsang HW, Ching S, Tang K, et al. Therapeutic intervention for internalized stigma of severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;173(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.013

- Smith LR, Earnshaw VA, Copenhaver MM, et al. Substance use stigma: reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.019

- Sharaf AY, Ossman LH, Lachine OA. A cross-sectional study of the relationships between illness insight, internalized stigma, and suicide risk in individuals with schizophrenia. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(12):1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.006

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030

- Ersoy MA. Varan A. Ruhsal hastalıklarda içselleştirilmiş damgalanma ölçeği Türkçe formu’nun güvenilirlik ve geçerlik çalışması. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2007;18(2):163–171.

- Mak WW, Wu CF. Cognitive insight and causal attribution in the development of self-stigma among individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(12):1800–1802. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.12.1800

- Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(1):192–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, et al. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(12):1437–1442. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1437

- Lysaker PH, Vohs JL, Tsai J. Negative symptoms and concordant impairments in attention in schizophrenia: associations with social functioning, hope, self-esteem and internalized stigma. Schizophr Res. 2009;110(1):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.015

- Vrbova K, Kamaradova D, Latalova K, et al. Self-stigma and adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders–cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;33(Suppl.):S316).

- Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee Y, et al. Self-stigma and its correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(5):599–601. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.599

- Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003

- Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, et al. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150(1):71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.005

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. p. 14–31.

- Schomerus G, Lucht M, Holzinger A, et al. The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: a review of population studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(2):105–112. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq089

- Miller NS, Sheppard LM, Colenda CC, et al. Why physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol-and drug-related disorders. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):410–418. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00007

- Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, et al. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. BJPsych Int. 2000;177(1):4–7.

- Can G, Tanrıverdi D. Social functioning and internalized stigma in individuals diagnosed with substance use disorder. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(6):441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.07.008

- Evren C, Saatçiolu Ö, Dalbudak E, et al. Tedavi motivasyonu anketi (TMA) Türkçe versiyonunun alkol bağımlısı hastalarda faktör yapısı, geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği. J Depend. 2006;7:117–122.

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Taylor AC, et al. Associations of metacognition and internalized stigma with quantitative assessments of self-experience in narratives of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;157(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.023

- Woods J. Methadone advocacy: the voice of the patient. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68(1):75–78.

- Joseph H, Stancliff S, Langrod J. Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): a review of historical and clinical issues. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67(5–6):347–364.

- Arıkan Z, Yasin Genç D, Çetin Etik D, et al. Alkol ve diğer madde bağımlılıklarında hastalar ve yakınlarında etiketleme. J Depend. 2004;5:52–56.

- Yılmaz E, Okanlı A. The effect of internalized stigma on the adherence to treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(5):297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.05.006

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1982;19(3):276–288. doi: 10.1037/h0088437

- Share D, McCrady B, Epstein E. Stage of change and decisional balance for women seeking alcohol treatment. Addict Behav. 2004;29(3):525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.022

- Lichtenstein E, Lando HA, Nothwehr F. Readiness to quit as a predictor of smoking changes in the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Health Psychol. 1994;13(5):393. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.13.5.393

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Toward a comprehensive, transtheoretical model of change: stages of change and addictive behaviors. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating addictive behaviors. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. p. 3–24.

- DiClemente CC. Motivation for change: implications for substance abuse treatment. Psychol Sci. 1999;10(3):209–213. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00137

- Tsang HW, Fung KM, Chung RC. Self-stigma and stages of change as predictors of treatment adherence of individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;180(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.001

- Cahill MA, Adinoff B, Hosig H, et al. Motivation for treatment preceding and following a substance abuse program. Addict Behav. 2003;28(1):67–79. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00217-9

- Blume AW, Schmaling KB, Marlatt GA. Memory, executive cognitive function, and readiness to change drinking behavior. Addict Behav. 2005;30(2):301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.019

- Blume AW, Schmaling KB, Marlat GA. Motivating drinking behavior change: depressive symptoms may not be noxious. Addict Behav. 2001;26(2):267–272. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00087-3

- Bond J, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The persistent influence of social networks and alcoholics anonymous on abstinence. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(4):579–588. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579

- Heeren T, Edwards EM, Dennis JM, et al. A comparison of results from an alcohol survey of a prerecruited internet panel and the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(2):222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00571.x

- Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Perrin PB, et al. A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(3):264–269. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.001322012

- Mo PK, Lau JT, Yu X, et al. A model of associative stigma on depression and anxiety among children of HIV-infected parents in China. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):50–59. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0809-9

- Cataldo JK, Brodsky JL. Lung cancer stigma, anxiety, depression and symptom severity. Oncology. 2013;85(1):33–40. doi: 10.1159/000350834