Abstract

For at least 40 years, social and behavioral scientists have argued that their disciplines need to do more to help solve real world practical problems. But doing this has proved difficult. In this paper, I describe three success stories where social and behavioral sciences have contributed important solutions and draw out evidence-based lessons for policy-makers, practitioners, university researchers and others who want to promote social and behavioral science informed actionable solutions to real world problems.

Partner engaged, solution-oriented research: Three success stories

Using third-party policing to improve school attendance

Academic school achievement depends heavily on school attendance with little evidence of any safe threshold of school absence (Hancock, Shepherd, Lawrence, & Zubrick, Citation2013). Third-party policing (Mazerolle & Ransley, Citation2006) attempts to control crime using non-offending third-party actors. Third-party policing strategies can be coercive as when police use landlords to discourage tenants in poor neighborhoods from making what are perceived to be 911 nuisance calls (Desmond & Valdez, Citation2013). But third-party policing strategies can also support rather than punish. In Queensland, Australia, parents or guardians of students with high levels of unauthorized school absences face an escalating series of government responses culminating in prosecution and fines. Children from poor families are disproportionately at risk.

The Ability School Engagement Program (ASEP) (Mazerolle, Antrobus, Bennett, & Eggins, Citation2017) is a partnership between researchers, Queensland Police Service and the Queensland Education Department to co-design and implement an intervention that “explained the legal escalation framework to the truants and their parents in a way that would raise awareness of the truancy laws, foster perceptions of the legitimacy of the laws, empower participants to willingly re-engage with school, and thereby, increase their school attendance” (Mazerolle et al., Citation2017, p. 470).

The intervention, implemented via family conferencing, was examined using a randomized field trial, in Brisbane, Australia. The control condition was business-as-usual response. Trial results showed that the program reduced official and self-reported truancy, assisted students to attend school and improved school attendance perceptions and behavior (Mazerolle et al., Citation2017).

ASEP also contributed to the knowledge base for third-party policing by showing when police can forge productive partnerships with third parties. Productive partnerships occur when police collaborate with partners rather than coercing them. Since third-party partners are often agencies with objectives like social welfare, police-third-party partnerships targeting different partners' goals likely yield more effective and less punitive approaches to crime control (Mazerolle, Citation2014).

Building commercial applications and new industries to support Indigenous people in remote regions

Spinifex is 69 species of native Australian grasses (genus Triodia) found in regional and remote Australia over one quarter of the Australian continent. Spinifex currently has no significant commercial use. In 2008, a research team including an architect-anthropologist, an architectural scientist, a nano-bio-engineer/material scientist, a botanist, a botanist-ecologist and an Aboriginal partner started a project using Western science and Indigenous knowledge to identify the properties and technology potential of spinifex grass (Memmott et al., Citation2009).

The project has yielded new information about the anthropology of traditional Indigenous spinifex uses (Memmott, Citation2012; Powell, Fensham, & Memmott, Citation2013), the biology, genetics, and ecology of Triodia, and optimal harvesting and land-management techniques (Gamage, Memmott, Firn, & Schmidt, Citation2014). Spinifex nanocellulose fibrils have properties (Amiralian, Annamalai, Memmott, & Martin, Citation2015) that make them suitable for commercial applications, including condoms, surgical gloves, compounded rubber (Hosseinmardi, Annamalai, Wang, Martin, & Amiralian, Citation2017), paper and packaging (Raj et al., Citation2016), ultrafine filtration and renewable carbon fibres (Gaddam et al., Citation2017; Jiang et al., Citation2017). They are easily and economically processed (Amiralian et al., Citation2015).

An agreement between the University and the Aboriginal Corporation informed by principles in Australian native title legislation, Australian law’s recognition that Indigenous people have rights to their land based on traditional laws and customs, provides for joint commercialization of intellectual property. This agreement creates an institutional framework for spinifex commercialization that may help establish viable Aboriginal-owned industries in remote Australia where none currently exists. The research agreement also shows how to build effective research and commercial partnerships between Australian Aboriginal people and western organizations like universities.

Addressing antisocial behavior among public housing tenants

In 2013, the Australian state of Queensland introduced a three strikes antisocial behavior policy for tenants living in state-owned housing. Tenants could receive strikes for behaviors such as excessive noise, loud music and parties, not keeping a property clean and tidy, or deliberate and minor damage. Households receiving three strikes in 12 months could be evicted. Tenants could also be evicted for “dangerous and severe actions” such as seriously damaging the property or being charged by police for injuring a neighbor.

In the year after the policy was introduced, 2.5% of households received a strike, with nearly two-thirds for disruptive behavior. In the 2 years after the policy’s introduction the annual eviction rate more than tripled (Jones, Phillips, Parsell, & Dingle, Citation2014). In response, the state government commissioned a study of the policy’s rationale and implementation, its impact on tenants, and the evidence of the effectiveness of such approaches particularly in relation to tenants with substance abuse and mental health problems (Jones et al., Citation2014).

The study showed that the policy did not appropriately account for the circumstances of public housing tenants with mental health and substance misuse problems and was therefore likely ineffective in reducing antisocial behavior. The research also suggested how to improve the policy and recommended a further review that explicitly recognized public housing’s role in supporting tenants with complex needs (Jones et al., Citation2014).

The research sponsor, the Queensland Mental Health Commission, subsequently prepared a report to state Parliament (i.e. the state legislature), recommending specific changes to the three strikes policy, broader changes to public housing policy and closer integration with other policy agencies such as the state health department (Queensland Mental Health Commission, Citation2015). The state accepted and supported all recommendations and sought appropriate funding through the government budget process.

The Mental Health Commission also commissioned an independent evaluation of how it was able to secure effective policy and practice change in this instance. This evaluation identified three key drivers of successful research translation to policy and practice: the quality of the research evidence in the original commissioned project; the collaboration model among the Queensland Mental Health Commission, researchers, other government agencies and other public housing stakeholders; and the leadership of the Commission in scoping the original research, preparing the Parliamentary report and presenting a balanced, comprehensive view of the policy issues relating to public housing for tenants with mental health and substance abuse issues to the state legislature (KPMG, Citation2017).

Lessons for encouraging more solution-oriented social and behavioral science

These three examples are successful applications of solution-oriented social and behavioral science. They are solution-oriented because they attempt to solve “real world” practical problems (Fox & Sitkin, Citation2015; Furman, Citation2016; Flyvbjerg, Citation2001; Miller, Citation2014; Watts, Citation2017; Western, Citation2016Citation). They are successful because they achieve outcomes – new research findings, policy and practice changes, commercialization and economic opportunities, better understandings of research-policy linkages – that would not have occurred otherwise. They are also distinctive because they were explicitly designed to realize practical, “extra-academic” outcomes as well as standard research outcomes and outputs.

Researchers and policy makers are sometimes described as operating in “two communities” (Nutley & Davies, Citation2000) or “parallel universes” (Brownson, Royer, Ewing, & McBride, Citation2006) with different objectives, institutional logics, cultures, incentives and timeframes. However, these communities are not completely separate; within them policy-makers and researchers interact but often in comparatively unstructured ways (Newman, Cherney, & Head, Citation2016). The same is true of university researchers and businesses, not-for-profits and civil society associations (Bastow, Dunleavy, Tinkler, & Aguilera, Citation2014). For social and behavioral science contributions to policy, practice and other social and economic outcomes to be more than accidental, we need to create purposeful linkages across organizations and sectors (Bastow et al., Citation2014). The mature form of such a linkage is an effective partnership between researchers and others, oriented to solving a practical problem, with a durable relationship between organizations that goes beyond individuals. Such a partnership should have common, synergistic and mutually beneficial objectives and outcomes (Bastow et al., Citation2014; Jasny et al., Citation2017; Shneiderman, Citation2016; Shneiderman & Hendler, Citation2017). Effective partnerships between university and non-university actors undergird the examples at the beginning of this paper.

Successful partnerships come from different forms of engagement between university researchers, policy makers and others. University researchers engage with governments, policy makers, businesses and not-for-profits in many ways. Academic service on external boards and committees and engagement interactions such as cross-sectoral roundtables, workshops and conferences are intended to foster knowledge transfer and dissemination. Direct research engagement takes place through episodic and spot-contracting and strategic commissioning of university researchers by third parties, and through larger partnerships and shared research programs that go beyond individual projects while technology transfer and the establishment of startups and spinouts focus on commercializing intellectual property (Bastow et al., Citation2014).

Partnerships in which university researchers work directly on a non-university actor’s practical problem increase the likelihood that research solutions will be adopted (Cherney, Head, Boreham, Povey, & Ferguson, Citation2013; Lindblom & Cohen, Citation1979) over more passive strategies that assume that if researchers produce relevant research other actors will take it up. Partnering on a real world problem ensures that researchers work on problems relevant to partners with those partners, who are often also solution adopters. One critical goal is therefore to get researchers to work on partners’ practical problems. The more fundamental goal, however, is to design elements of the research ecosystem to produce outcomes that all participants (policy-makers, service deliverers, researchers, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders) value.

Partner-engaged, solution-oriented research can be initiated by research sponsors outside universities or by university researchers. Governments, businesses, foundations, and other organizations who initiate projects tend to rely on activities like episodic and spot contracting, strategic commissioning and longer term partnerships (Bastow et al., Citation2014) where the non-university organization defines the problem to be solved and provides funding along with appropriate accountabilities to ensure progress towards the solution. This is a mission-driven “connected science” model that specifically links funding to an end product and funds what is required for delivery (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, Citation2017). It contrasts with supporting investigator-initiated basic science and assuming that research findings will then be applied to practical problems and translated to policy and practice.

US examples of the connected model include the funding programs associated with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA, https://www.darpa.mil/about-us/about-darpa; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, Citation2017), related Department of Defense coordination of research and technology development linked to the Cold War (Sarewitz, Citation2016), the social science research procurements for Johnson’s Great Society programs in the 1960s (Prewitt, Citation2016), the Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy, Citation2017), and the contemporary commissioning of sponsored projects. Other funding programs based on the connected model include the Grand Challenges program of the Gates Foundation (Grand Challenges, Citation2017), the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Program (European Commission, Citation2017) and the programs of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (Chan Zuckerberg Foundation, Citation2018).

Lessons for policy makers and other representatives of non-university organizations

The connected model of research investment is a starting point for policy-makers and others who want to directly engage university researchers on actionable solutions to real world problems. But there are other ways external actors can help build engagement and effective partnering, starting with understanding what researchers value and incorporating this into research investment frameworks and project scopes. Researchers particularly value being able to address scientifically important research questions with the potential for new knowledge (Hemsley-Brown, Citation2004) that lead to high quality academic publications. Allowing or requiring researchers to publish findings and providing access to key resources like data and policy expertise can make working on partners’ problems much more attractive to university researchers.

Policy makers and others can also recognize and communicate the value of solving practical problems to university researchers. Many want to produce work that is relevant beyond the academy but university reward systems can work against this interest (see below). Partners who can align project outputs with researchers’ incentives and help researchers see and realize other concrete benefits will find it easier to enlist researchers in their projects.

Different drivers and incentive systems foster researcher engagement with non-university partners. Funding agencies such as the National Science Foundation (Citation2015), Research Councils UK and the Australian Research Council incorporate broader social and economic impacts into their program assessment criteria. Working with non-university partners allows researchers to show engagement and impact that helps make funding proposals more competitive. Many countries also undertake system-wide assessments of the real world impact of university research such as the UK’s Research Evaluation Framework (REF, Citation2014) or Australia’s Engagement and Impact Assessment (Australian Research Council, Citation2015) that create favorable environmental conditions for partner-engaged research.

Solving practical problems also potentially advances social and behavioral science because solutions need to work in the real world. This requirement can discipline researchers to make replicable breakthroughs (Watts, Citation2017) that will work repeatedly. Working to solve real problems does not guarantee replicability, but focusing on solutions that will be used in real settings and contexts directs researchers to solutions that work consistently and robustly including in contexts that may differ from those in which they were developed. Understanding what works and when can drive social and behavioral science breakthroughs that researchers value highly

Designing and using appropriate program models also facilitates research partnering. The connected model of research investment links funding to desired practical outcomes. But university researchers value working on problems they choose. Funding programs for connected research differ in the extent to which they allow researchers to initiate projects. For discrete projects, the required outcome is usually set by the project sponsor, but larger connected funding programs often allow researchers to initiate projects. In the United States, for instance, the Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E) supports research into new energy technologies through a combination of directed programs and open funding calls (Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy, Citation2017). In Australia the Try Test and Learn Fund of the Federal Department of Social Services (Social Security) supports rapid development, piloting and evaluation of innovative solutions to long-term welfare dependence. Projects can be proposed by university researchers, the private sector, not-for-profits, the Department itself, other state and federal agencies, and consortia of these groups. Successful projects are co-designed with the Department but undertaken by project teams with access to departmental resources, such as data on income support (welfare) recipients (Australian Department of Social Services, Citation2017).

Appropriate program models need to be accompanied by effective agreements or contracts. Research projects sponsored by government, business and not-for-profits are typically covered under agreements that address different parties’ accountabilities, milestones and deliverables. Effective agreements address issues such as the research plan and relevant responsibilities, intellectual property ownership, data requirements, ownership and sharing, publication rights, commercialization, dispute resolution and partnership termination. (Jasny et al., Citation2017; Shneiderman & Hendler, Citation2017)

Lessons for university researchers and administrators

University researchers and administrators can also encourage partner-engaged, solution-oriented research by working on problems that matter to sponsors and research end-users. Under the connected model, non-university partners typically set project objectives. But university researchers who want to engage non-university partners also benefit from initiating real world focused projects that will be of value to external partners. Working on real world problems creates a strong incentive for end-users to engage with the research and researchers (Fox & Sitkin, Citation2015; Furman, Citation2016). Working on real problems increases the relevance of university research and also creates conditions for research innovation and scientific breakthroughs as I note below.

However, partner-engaged solution-oriented research may also demand new forms of research practice incorporating new insights to solutions, partnering, collaboration and teamwork. Putting partnerships at the center can broaden research teams beyond social science and beyond universities while allowing researchers to work in realistic settings on real questions with real data to solve problems and produce high quality research outputs (Shneiderman, Citation2016). This approach implies an expanded view of the full project lifecycle, from co-identifying and co-developing a shared awareness of the problem or functional requirement to be addressed, determining an approach, prototyping and testing a solution, moving to scaled up implementation, and then looking to “scale out” to new (real) contexts, settings and problems (Shneiderman, Citation2016). This approach parallels and extends the movement from “bench to bedside” in medical and public health research and “bench to curbside” in justice research (Mazerolle et al., Citation2017; Szilagyi, Citation2009), which is sometimes seen as moving from basic science to small-scale trials and finally scaled-up intervention in real settings. The full project lifecycle corresponds to a Science, Engineering and Design (SED) approach to research (Shneiderman, Citation2016), where science, including social and behavioral science, provides understanding, description and explanation, engineering helps develop solutions and design brings different parties together to identify needs and requirements (Shneiderman, Citation2016). This approach also blurs the distinction between basic and applied research because in producing solutions researchers also produce new knowledge and advance theory (Fox & Sitkin, Citation2015; Haskins & Margolis, Citation2015; Shneiderman, Citation2016; Shneiderman & Hendler, Citation2017).

SED principles have two direct implications for research practice. Projects that follow the full life-cycle from co-designing questions and problems, to developing, testing and implementing scaled solutions, will use many theories, methods, data and research designs. No single approach adequately covers the full project life-cycle because research objectives and contexts differ across the life-cycle and between subprojects (Fox & Sitkin, Citation2015) and because workable solutions demand appropriate theory and evidence however derived. At some parts of the research process, for example, researchers may need to assess if a solution works. Depending on context and problem this may require a strong causal analysis, but it may be enough to know if a solution predicts an outcome (Kleinberg, Ludwig, Mullainathan, & Obermeyer, Citation2015). For causal analysis, an experimental approach like a randomized controlled trial or a lab experiment may be appropriate. But if a solution has to work in highly variable complex contexts, if institutional or policy constraints prohibit randomization (Brownson et al., Citation2006; Fox & Sitkin, Citation2015), or if researchers are moving from prototyping to real world implementation, other methods such as non-experimental econometric evaluation (Khandker, Koolwal, & Samad, Citation2009), meta-analyses, systematic reviews, causal Bayes nets, process tracing (Cartwright & Hardie, Citation2012), detailed ethnographic case-studies (Moran, Citation2016; Shneiderman & Plaisant, Citation2006) or computer simulations (Mazerolle, Baxter, et al., Citation2017; Sullivan, Welsh, & Ilchi, Citation2017) may be needed.

Research teams trying to solve real world problems will frequently be multidisciplinary as well as involving university and non-university partners. For policy and practice research and research with business and not-for-profits, stakeholder communities and end-users may also be a core part of project teams or key project participants. Other team members who bring expert policy, practical or professional knowledge, data experts, and so on can also be critical. Teams may also be multidisciplinary because developing solutions demands diverse expertise and functional team capabilities. The examples at the beginning of this paper included researchers from social and behavioral science, humanities, life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, and design and practice professions, as well as policy-makers, enduser groups and relevant communities.

Solution-oriented social and behavioral science also requires functionally differentiated teams; interdependent team members, working on problem design, conceptualization, data collection and analysis, prototyping, resourcing, business development, implementation, knowledge transfer and so on. Whereas multidisciplinary research frequently involves bringing different disciplinary lenses to a common research question, solution-oriented research across a project lifecycle involves bringing different functional specialists together to address aspects of solution development, validation and refinement for different contexts. Building a team like this is analogous to building a team for a large construction or engineering project that requires different specialists working interdependently towards a common objective.

Solution-oriented research partnering also requires university researchers to listen actively to partners. This is a very substantial cultural shift. As substantive and research experts, it is tempting for university researchers to start partnerships by “telling” rather than listening. Telling involves researchers applying their definition of the situation to a partner’s problem at the expense of the partner’s understanding. It may, for instance, involve researchers redefining or defining a problem to enable a straightforward social and behavioral science solution, proposing a solution before properly understanding a problem, or trying to impose an approach that reflects scientific best practice but is not commercially, practically or politically implementable (Brownson et al., Citation2006). University researchers who want genuine partnerships working on partners’ problems, need to listen rather than tell to properly understand a problem as partners define it, and to understand partners’ needs and constraints. University researchers also need to recognize, respect and take advantage of the different types of policy, practical, and technical expertise that non-university partners bring to a research team. Contributions by partners can greatly strengthen research, as I note below.

Universities can support researchers to build effective partnerships by creating fit-for-purpose research institutions. Partnerships require specialist professional support in areas like research development, legal review, intellectual property, contract management, project management and research ethics. Moreover, even extensive partnerships often depend on strong personal relationships between a few individuals with mutual trust and shared knowledge of each others’ organizations and objectives. These conditions make effective partnering difficult and may disincentivize it unless university researchers have appropriate professional support. Fit-for-purpose research institutions like appropriately configured and resourced university research institutes and centers help solve this problem by building institutionalized linkages and partnership capabilities that go beyond personal relationships and qualities.

Research institutions like this often have an explicit solution-oriented social and behavioral science mission and accompanying organizational narrative describing the value and benefits of solution-oriented research to wider society, partners and stakeholders, and researchers. They also require a critical mass of high quality researchers in core capability areas, research leaders who can model effective non-university partnering and engagement and specialized professional services support in areas such as research development, legal, contract and intellectual property management, project management, finance and human resources. Solution-oriented research may also need specialized physical and technical infrastructure and facilities for designing and prototyping, collecting, storing and analyzing data and clear policies and procedures establishing transparent and fair terms and conditions for collaboration within and outside the organization.

Finally, because solution-oriented research differs from traditional university research in objectives, mission and outcomes, institutional reward and recognition systems should be designed accordingly. Inside universities academic and disciplinary cultures do not always reward and recognize partnering. But realigning university recruitment and reward systems to recognize cross-disciplinary and cross-sectoral partnering and solutions-based research outcomes is possible. New reward and incentive systems should complement existing systems as solution-oriented partner-engaged research complements discipline-oriented research. Recognizing and rewarding factors like non-university employment, non-traditional academic research outputs, or cross-disciplinary and cross-sectoral research collaboration in university hiring, tenure and promotion illustrates some potential changes (Klein & Falk-Krzesinski, Citation2017).

Implications for graduate and postdoctoral training

Regardless of discipline, at least 50% of doctoral graduates will not achieve long-term traditional teaching and research academic appointments in universities (McGagh et al., Citation2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine, Citation2017). Equally, partner-engaged, solution-oriented research inside universities draws on skills and experiences that traditional disciplinary research training sometimes neglects. Using social and behavioral science to solve real problems provides a way to rethink graduate and postdoctoral training to accommodate the diverse labor market opportunities doctoral and postdoctoral graduates now face.

Such a reconfigured approach acknowledges that the primary purpose of research training is to produce a doctoral or postdoctoral graduate who is well equipped for jobs inside and outside universities. Training can then be embedded within a comprehensive researcher development framework (for example, Vitae, Citation2010) that includes researcher domains or competencies such as engagement and influence, research governance, and personal effectiveness as well as disciplinary and technical knowledge and ability.

In practice, this type of research training may incorporate structured experiences of university-non-university partnering, such as co-design with government, industry and not-for-profits of doctoral projects, workplace internships, and/or data or resource sharing, and activities to develop transferrable skills, such as disciplinary knowledge, data and methods skills, communication, problem solving, project management, creativity, teamwork and working with others outside the organization, that are relevant to university and non-university based research (Sinche et al., Citation2017).

A comprehensive vehicle like an academic portfolio of skills, experiences and outputs enables graduates to recognize and evidence their skills and experiences to employers (McGagh et al., Citation2016), while making available current and time series data on doctoral graduate employment outcomes helps students choose schools and programs and understand associated outcomes (McGagh et al., Citation2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine, Citation2017). This kind of training aims to build traditional disciplinary knowledge and “intellectual self-confidence” (American Historical Association, Citation2017) to go beyond immediate expertise to work on problems that are set by partners rather than chosen by researchers, including the confidence to work in unfamiliar ways with others who have different perspectives and expertise.

What are the benefits?

Solution-oriented social and behavioral science built on partnerships has the potential to benefit science and reinvigorate research fields, improve the quality of policy and program solutions, democratize research and benefit stakeholder communities, improve returns on research investment, and contribute to the public-value (Brewer, Citation2013) of university research.

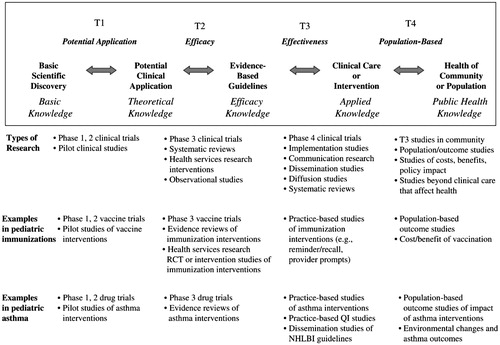

These benefits come in a number of ways. Solution-oriented research is necessarily future-oriented because solutions implemented in real world settings need to work robustly in contexts that researchers do not always anticipate or test. Moving solutions from idealized to realistic conditions and understanding how robust they are to contextual variations and real world implementation creates opportunities and requirements to advance fields and develop a cumulative evidence base (Mazerolle et al., Citation2017). Again, this is analogous to “bench to bedside” or translation pathway models in health sciences (Szilagyi, Citation2009) that encompass basic scientific discovery, limited application and testing, and scaled-up real world implementation, with different research designs, methodologies and approaches along the way. illustrates such a pathways model from pediatrics that incorporates basic research through to public health population implementation.

Figure 1. Example translational research framework for studies of pediatric asthma. RCT indicates randomized control trial; QI indicates quality improvement; NHLBI indicates National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Reprinted from Szilagyi, Citation2009 with permission from Academic Pediatrics).

Not all solution-focused projects will encompass this spectrum but developing and implementing solutions focuses research and discovery on targeted questions and requires researchers to be theoretically and methodologically open to different but appropriate ways of tackling research questions. Helping solve hard practical problems also appeals intrinsically to many researchers, stimulating their motivation and creativity.

Requiring solutions to work effectively in real world contexts also means that research projects benefit greatly from involving the stakeholder communities to whom solutions are often addressed. Involving stakeholders who are affected by research democratizes research and builds stakeholder expertise into research solutions. This last can help protect against researcher error that might come from overly abstract, unrealistic or partial disciplinary and theoretical perspectives.

In the 1960s, psychologists developed the marshmallow test to show that children who deferred gratification, by waiting 15 min after being offered a marshmallow so as to receive a second one, had better later cognitive and behavioral outcomes than children who preferred to eat one immediately and forego the second (Shoda, Mischel, & Peake, Citation1990). However a recent extension of the marshmallow experiment shows that mother’s education and social background largely explain differences in deferring gratification and among children with similar social backgrounds deferring gratification or not makes little difference (Watts, Duncan, & Quan, Citation2018). Other research suggests why some children do not wait – in poor families eating the first marshmallow quickly may be sensible when daily life is uncertain and waiting on a future promise is risky (Calarco, Citation2018).

That unpredictability and lack of control over circumstances encourage different behavioral responses than when life is ordered is evident to researchers who have worked with such communities. Early community engagement would have quickly alerted researchers to limitations in the marshmallow test evidence arising from the narrowness of the sample. Such engagement is especially critical when researchers develop interventions from research studies, because once we move from closed and idealized research conditions to open systems in the real world, interventions that are not robust to people’s diverse circumstances can do harm as well as side-tracking a research agenda. In justice services, research frameworks, such as a life course perspective (Piquero, Farrington, & Blumstein, Citation2003), that recognize connections between longitudinal, macro and micro-contexts, highlight the complexity that scaled-up solutions need to accommodate.

Deep partnering to develop, monitor and evaluate solutions promotes an evidence-based approach to policy and program development, implementation and adaptation. It may also encourage more prudent research investment by shortening the pathway from research to real world impact and raising the likelihood that research-based solutions will be adopted or trialed.

Implications for the justice sector

In the justice sector, solutions have focused on reducing crime and disorder and improving quality of life and life outcomes. The current trend to marketized justice solutions which involve governments, private sector organizations, non-profits, charities and civil society associations, competing and collaborating to deliver justice services (Tomczak, Citation2013) aligns at one level with a solution-oriented approach to research based on deep partnering. Establishing market-based systems to drive developments in technologies, instruments, processes and programs for delivering justice services, parallels the arguments in this paper about developing research ecosystems to encourage partnering between university researchers and others in solution-oriented social and behavioral science (Mazerolle et al., Citation2017; Tomczak, Citation2013).

One key challenge in moving to solution-oriented research, however, is for researchers to maintain an appropriate stance in relation to desired outcomes. Marketized justice solutions, for instance, can have many objectives, from controlling costs, redefining the role of the public sector and establishing new principles to allocate resources, to reducing and controlling crime, maintaining public safety and social order, and improving outcomes for victims and perpetrators. They can also have multiple and unintended consequences, including consequences that harm as well as benefit.

Researchers will differ in how they prioritize objectives, but working toward explicit solutions to partners’ problems may force researchers to think explicitly about their values in a way that traditional investigator-initiated research does not and to build safeguards against harm into the research process. Solution-oriented research may also sharpen divisions within research communities around values as well as theories and methods. In justice services, as in other policy areas, solutions are not politically neutral, even when they are rigorously evidence-based. Deciding what problems matter, and what parameters or priorities frame the “solution-space” to distinguish acceptable solutions from unacceptable ones are political and normative questions that go beyond science and social science. Researchers who adopt a solution-focused orientation will need to think about their boundaries or limits in relation to the problems they work on and the kinds of solutions they entertain. Different researchers will have different views on these issues.

Researchers will also need to think seriously about avoiding and minimizing harm. The emerging policy framework of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) may offer a useful approach. RRI has two objectives: to specify normative anchors to define the “right” research and innovation outcomes and to direct research to achieve those outcomes (Von Shomberg, Citation2013). RRI involves all stakeholders in research and innovation processes from the outset and creates mutually responsive and shared responsibilities for outcomes and processes (Klaasen, Kupper, Rijnen, Vermuelen, & Broerse, Citation2014). In practice RRI opens research and solution development to ongoing deliberation by relevant societal actors about solution objectives, approaches, applications and outcomes. RRI processes explicitly include diverse actors and stakeholders and ongoing anticipation and reflection about values, objectives, assumptions and research practices. The framework entails commitments to open and transparent research, solution finding and public engagement, and responsiveness and adaptiveness to new knowledge, perspectives, views and norms (Klaasen et al., Citation2014). RRI tries to democratize solution-oriented research to include all stakeholders in ongoing deliberations and monitoring about desired outcomes and how to get there. RRI has been embedded in the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Funding Framework (European Commission, Citation2017).

Constructing scientific objectives as problems needing solutions or challenges to be overcome and embedding research within appropriate institutions and frameworks has driven innovation in computing, jet propulsion, lasers, satellites, cell phones, the Internet, GPS, digital imaging, nuclear and solar power and sequencing the human genome (DeLisi, Citation2008; Sarewitz, Citation2016). Social and behavioral science based on solving real world problems and partnering deeply within and outside universities has substantial promise for improving policy and practice, enhancing relevance and impact, generating innovative breakthrough research, and building the public value of social and behavioral science.

Acknowledgement

I thank Ben Shneiderman, Al McEwan, Bruce Western, Lorraine Mazerolle, Paul Memmott, Darren Martin, Janeen Baxter and Duncan Watts for helpful comments and conversations that have shaped this paper. Ning Xiang provided very effective research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mark Western

Mark Western is Director of the Institute for Social Science Research, at The University of Queensland, Australia.

References

- Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy. (2017). ARPA-E. Retrieved from https://arpa-e.energy.gov/?q=program-listing.

- American Historical Association (2017). Intellectual self confidence. Retrieved from https://www.historians.org/jobs-and-professional-development/career-diversity-for-historians/career-diversity-resources/five-skills/intellectual-self-confidence.

- Amiralian, N., Annamalai, P. K., Memmott, P., & Martin, D. J. (2015). Isolation of cellulose nanofibrils from Triodia pungens via different mechanical methods. Cellulose, 22(4), 2483–2498. doi:10.1007/s10570-015-0688-x

- Amiralian, N., Annamalai, P. K., Memmott, P., Taran, E., Schmidt, S., & Martin, D. J. (2015). Easily deconstructed, high aspect ratio cellulose nanofibres from Triodia pungens: An abundant grass of Australia's arid zone. RSC Advances, 5(41), 32124–32132. doi:10.1039/C5RA02936H

- Australian Department of Social Services (2017). Try, test and learn fund. Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/review-of-australias-welfare-system/australian-priority-investment-approach-to-welfare/try-test-and-learn-fund.

- Australian Research Council (2015). Engagement and impact assessment. Retrieved from http://www.arc.gov.au/engagement-and-impact-assessment.

- Bastow, S., Dunleavy, P., Tinkler, J., & Aguilera, N. (2014). The impact of the social sciences: how academics and their research make a difference. Simon Bastow, Patrick Dunleavy, Jane Tinkler, Natalie Aguilera (Eds.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Brewer, J. D. (2013). The public value of the social sciences: An interpretive essay London: Bloomsbury.

- Brownson, R. C., Royer, C., Ewing, R., & McBride, T. D. (2006). Researchers and policymakers: Travelers in parallel universes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(2), 164–172. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.004

- Calarco, J. M. (2018). Why rich kids are so good at the marshmallow test. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/06/marshmallow-test/561779/.

- Cartwright, N., & Hardie, J. (2012). Evidence-based policy: A practical guide to doing it better Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Chan Zuckerberg Foundation (2018). Chan Zukerberg initiative. Retrieved from https://chanzuckerberg.com/.

- Cherney, A., Head, B., Boreham, P., Povey, J., & Ferguson, M. (2013). Research utilization in the social sciences. Science Communication, 35(6), 780–809. doi:10.1177/1075547013491398

- DeLisi, C. (2008). Meetings that changed the world: Santa Fe 1986: Human genome baby-steps. Nature, 455(7215), 876–877. doi:10.1038/455876a

- Desmond, M., & Valdez, N. (2013). Unpolicing the urban poor: Consequences of third-party policing for inner-city women. American Sociological Review, 78(1), 117–141. doi:10.1177/0003122412470829

- European Commission (2017). Horizon 2020. The EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. Bent Flyvbjerg (Ed.); translated by Steven Sampson Oxford, UK, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Fox, C. R., & Sitkin, S. B. (2015). Bridging the divide between behavioral science & policy. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(1), 1–12. doi:10.1353/bsp.2015.0004

- Furman, J. (2016). Applying behavioral sciences in the service of four major economic problems. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2(2), 1–9. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/662204 doi:10.1353/bsp.2016.0011

- Gaddam, R. R., Jiang, E., Amiralian, N., Annamalai, P. K., Martin, D. J., Kumar, N. A., & Zhao, X. S. (2017). Spinifex nanocellulose derived hard carbon anodes for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, 1, 1090–1097. doi:10.1039/C7SE00169J

- Gamage, H. K., Memmott, P., Firn, J., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Harvesting as an alternative to burning for managing spinifex grasslands in Australia. Advances in Ecology, 2014, 1.

- Grand Challenges (2017). Grand challenges. Retrieved from https://grandchallenges.org/#/map.

- Hancock, K. J., Shepherd, C. C. J., Lawrence, D., & Zubrick, S. R. (2013). Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts. Canberra. Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Haskins, R., & Margolis, G. (2015). Show me the evidence: Obama's fight for rigor and evidence in social policy Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Hemsley-Brown, J. (2004). Facilitating research utilisation: A cross-sector review of research evidence. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 17(6), 534–552. doi:10.1108/09513550410554805

- Hosseinmardi, A., Annamalai, P. K., Wang, L., Martin, D., & Amiralian, N. (2017). Reinforcement of natural rubber latex using lignocellulosic nanofibers isolated from spinifex grass. Nanoscale, 9(27), 9510–9519. doi:10.1039/C7NR02632C

- Jasny, B. R., Wigginton, N., McNutt, M., Bubela, T., Buck, S., Cook-Deegan, R., … Watts, D. (2017). Fostering reproducibility in industry-academia research. Science (New York, N.Y.), 357(6353), 759. doi:10.1126/science.aan4906

- Jiang, E., Amiralian, N., Maghe, M., Laycock, B., McFarland, E., Fox, B., … Annamalai, P. K. (2017). Cellulose nanofibers as rheology modifiers and enhancers of carbonization efficiency in polyacrylonitrile. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 5(4), 3296–3304. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b03144

- Jones, A., Phillips, R., Parsell, C., & Dingle, G. (2014). Review of systemic issues for social housing clients with complex needs. Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. https://www.qmhc.qld.gov.au/about/publications/browse/research-reports/final-report-review-of-systemic-issues-housing-clients-with-complex-needs-september-2014-issr.

- Khandker, S., Koolwal, G. B., & Samad, H. A. (2009). Handbook on impact evaluation quantitative methods and practices. Washington: World Bank Publications.

- Klaasen, P., Kupper, F., Rijnen, M., Vermuelen, S., & Broerse, J. (2014). Policy brief on the state of the art of RRI and a working definition of RRI. https://www.rri-tools.eu/documents/10184/104615/RRI+Tools+Policy+ Brief+(EN).pdf/82ffca72-df32-4f0b-955e-484c6514044c

- Klein, J. T., & Falk-Krzesinski, H. J. (2017). Interdisciplinary and collaborative work: Framing promotion and tenure practices and policies. Research Policy, 46(6), 1055–1061.

- Kleinberg, J., Ludwig, J., Mullainathan, S., & Obermeyer, Z. (2015). Prediction policy problems. American Economic Review, 105(5), 491–495. doi:10.1257/aer.p20151023

- KPMG (2017). Key drivers of policy and practice change in social housing. Queensland Mental Health Commission Final Report. KPMG. https://www.qmhc.qld.gov.au/documents/keydriversofpolicyandpracticechangeinsocialhousingfinalreportpdf. Brisbane, Australia.

- Lindblom, C. E., & Cohen, D. K. (1979). Usable knowledge: Social science and social problem solving. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Mazerolle, L. (2014). The power of policing partnerships: Sustaining the gains. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(3), 341–365. doi:10.1007/s11292-014-9202-y

- Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Eggins, E. (2017). Reducing truancy and fostering a willingness to attend school: Results from a randomized trial of a police-school partnership program. Prevention Science, 18(4), 469–480. doi:10.1007/s11121-017-0771-7

- Mazerolle, L., Baxter, J., Cobb‐Clark, D., Haynes, M., Lawrence, D., & Western, M. (2017). From bench to curbside. Criminology & Public Policy, 16(2), 501–510. doi:10.1111/1745-9133.12287

- Mazerolle, L., & Ransley, J. (2006). Third party policing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- McGagh, J., Marsh, H., Western, M., Thomas, P., Hastings, A., Mihailova, M., & Wenham, M. (2016). Review of Australia’s research training system. Report for the Australian Council of Learned Academies. Australian Council of Learned Academies. Canberra, Australia.

- Memmott, P. (2012). Bio-architectural technology and the dreamtime knowledge of spinifex grass. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 24(1), 65–66.

- Memmott, P., Martin, D., de Silva, D. S. M., Flutter, N., Gamage, H., Schmidt, S., & Fensham, R. (2009). Towards novel biomimetic building materials: Evaluating aboriginal and western scientific knowledge of spinifex grass. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, Brisbane, Australia.

- Miller, T. R., Wiek, A., Sarewitz, D., Robinson, J., Olsson, L., Kriebel, D., & Loorbach, D. (2014). The future of sustainability science: A solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustainability Science, 9(2), 239–246. doi:10.1007/s11625-013-0224-6

- Moran, M. (2016). Serious whitefella stuff: When solutions became the problem in Indigenous affairs. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2017). Graduate training in the social and behavioral sciences: Proceedings of a workshop–in brief. Washington, DC: T. N. A. Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017). Returns to federal investments in the innovation system: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- National Science Foundation (2015). Perspectives on broader impacts. (NSF 15-008). National Science Foundation. Alexandria, VA. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/od/oia/publications/Broader_Impacts.pdf.

- Newman, J., Cherney, A., & Head, B. W. (2016). Do policy makers use academic research? Reexamining the “two communities” theory of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 76(1), 24–32. doi:10.1111/puar.12464

- Nutley, S., & Davies, H. T. O. (2000). Getting research into practice: Making a reality of evidence-based practice: Some lessons from the diffusion of innovations. Public Money & Management, 20(4), 35–42. doi:10.1111/1467-9302.00234

- Piquero, A., Farrington, D., & Blumstein, A. (2003). The criminal career paradigm. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 30(30), 359–506. doi:10.1086/652234

- Powell, O., Fensham, R. J., & Memmott, P. (2013). Indigenous use of spinifex resin for hafting in north-eastern Australia. Economic Botany, 67(3), 210–224. doi:10.1007/s12231-013-9238-3

- Prewitt, K. (2016). 09/19/2017). Can social science matter? Retrieved from http://items.ssrc.org/can-social-science-matter/

- Queensland Mental Health Commission (2015). Ordinary report social housing systemic issues for tenants with complex needs. Brisbane, Queensland: Queensland Mental Health Commission Retrieved from https://www.qmhc.qld.gov.au/about/publications/browse/research-reports/final-report-review-of-systemic-issues-housing-clients-with-complex-needs-september-2014-issr.

- Raj, P., Mayahi, A., Lahtinen, P., Varanasi, S., Garnier, G., Martin, D., & Batchelor, W. (2016). Gel point as a measure of cellulose nanofibre quality and feedstock development with mechanical energy. Cellulose, 23(5), 3051–3064. doi:10.1007/s10570-016-1039-2

- REF (2014). REF 2014 Research Excellence Framework. Retrieved from http://www.ref.ac.uk/.

- Sarewitz, D. (2016). Saving science. The New Atlantis, 49, 4–40.

- Shneiderman, B. (2016). The new ABCs of research: Achieving breakthrough collaborations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shneiderman, B., & Hendler, J. (2017). It's the partnership, stupid. Issues in Science and Technology, 33, 37–40.

- Shneiderman, B., & Plaisant, C. (2006). Strategies for evaluating information visualization tools: Multi-dimensional in-depth long-term case studies. Proceedings of the 2006 AVI workshop on BEyond time and errors: novel evaluation methods for information visualization. Venice, Italy. doi: 10.1145/1168149.1168158 1–7.

- Shoda, Y., Mischel, W., & Peake, P. K. (1990). Predicting adolescent cognitive and self-regulatory competencies from preschool delay of gratification: Identifying diagnostic conditions. Developmental Psychology, 26(6), 978–986. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.978

- Sinche, M., Layton, R. L., Brandt, P. D., O’Connell, A. B., Hall, J. D., Freeman, A. M., … Brennwald, P. J. (2017). An evidence-based evaluation of transferrable skills and job satisfaction for science PhDs. PLoS One, 12(9), e0185023. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185023

- Sullivan, C. J., Welsh, B. C., & Ilchi, O. S. (2017). Modeling the scaling up of early crime prevention. Criminology & Public Policy, 16(2), 457–485.

- Szilagyi, P. G. (2009). Translational research and pediatrics. Academic Pediatrics, 9(2), 71–80. Retrieved from doi:10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.002

- Tomczak, P. J. (2013). The penal voluntary sector in England and Wales: Beyond neoliberalism? Criminology & Criminal Justice, 14(4), 470–486. doi:10.1177/1748895813505235

- Vitae (2010). Introducing the researcher development framework to employers. In V. C. R. A. C. Limited (Ed.). https://www.vitae.ac.uk/vitae-publications/rdf-related/introducing-the-vitae-researcher-development-framework-rdf-to-employers-2011.pdf/view: Vitae.

- Von Shomberg, R. (2013). A vision of responsible innovation. In R. Owen, M. Heintz & J. Bessant (Eds.), Responsible Innovation. London: John Wiley.

- Watts, D. J. (2017). Should social science be more solution-oriented? Nature Human Behaviour, 1(1), 0015. doi:10.1038/s41562-016-0015

- Watts, T. W., Duncan, G. J., & Quan, H. (2018). Revisiting the marshmallow test: A conceptual replication investigating links between early delay of gratification and later outcomes. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1159–1177. doi:10./0956797618761661

- Western, M. C. (2016). We need more solution-oriented social science: On changing our frames of reference and tackling big social problems. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/06/06/we-need-more-solution-oriented-social-science/.