ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this research is to expose political functions of the delegates to the local people’s congresses in China. It focuses on the local people’s congress delegates selected from the circles of the People’s Liberations Army (PLA).

Using the data from the Jiangsu Province Yangzhou Municipal People’s Congress from 1998 to 2015, this research examines how the information gathering function of the local people’s congresses has changed over the last decade or so. In particular, analyzing the contents of the bills submitted to the people’s congress by the delegates selected from the PLA circles, this research depicts how the PLA has gradually started expressing its demands through the people’s congresses over the last decade.

At the end of the 1990s, the PLA almost never submitted bills to the local people’s congresses. In regards to this reason, an individual familiar with the local people’s congresses responded that “even if the PLA had any demands it did not submit bills since it was able to solve these issues within its own system.” However, in the recent years, the PLA has been submitting its requests to the people’s congresses in the form of bills. This research explores the political meaning of the change in the relationship between the local people’s congresses and the PLA.

1 Introduction

How does the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) utilize the people’s congresses? The aim of this paper is to make clear how the PLA expresses its concerns and wishes during the session of the people’s Congresses.

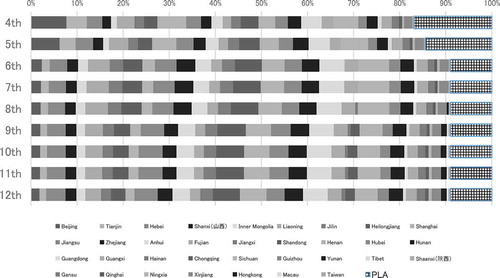

The PLA sends a considerable number of internally elected member delegates to people’s congresses. For example, there are 2987 delegates at the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) and 268 are from the PLA. When the NPC is in session, these PLA delegates form a PLA delegation. During this time, the NPC’s nearly 3000 delegates meet to listen to the reports on the activities of government agencies. While they may vote to make decisions, they do not deliberate on proposed bills. Deliberation occurs within the 35 individual delegations that comprise the NPC. NPC delegates, in addition to those from the PLA, form delegations based on their electoral districts. In other words, the 34 delegations represent these areas (province-level administrative districts). Of all the 35 total delegations, the PLA delegation is the largest (see and ). This is also true at the province level and in the lower people’s congresses as well.

Table 1. Membership of the NPC.

Existing research has not focused on the activities of PLA delegates during people’s congresses. It is clear that the PLA uses the people’s congresses—China’s authoritative and legislative agencies—as tools to make requests that will influence policy decisions.

The PLA drafts the necessary laws to realize its demands and then presents them to these legislative bodies. For example, the Central Military Commission’s Legislation Bureau drafted and submitted to the NPC’s Standing Committee the “Military Personnel Insurance Law of the People’s Republic of China” in order to address the laws relating to PLA injury insurance, death insurance, post-retirement medical and senior citizen insurance, and benefits for military families.Footnote1 Furthermore, in the process of deliberations, the PLA presents opinions regarding modifying laws drafted by other state agencies so that its interests will not be harmed. For example, during deliberations regarding the draft of the “Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China” that was written by the Legislative Affairs Commission of the NPC’s Standing Committee, the Central Military Commission’s Legislation Bureau submitted modification proposals regarding military-related items.Footnote2

The PLA also engages in various activities in addition to legislative duties. PLA delegates submit bills, proposals, comments, and opinions to the congresses. Delegates at people’s congresses bring together the requests of the areas that elected them (their electoral districts)Footnote3 in the form of bills, propositions, comments, and opinions. After the presidium of the people’s congress in question accepts the requests, it examines the content and sends them to the related government agencies. The PLA delegates also present to the congresses the requests of the PLA (through their respective electoral districts) in the same form.

Electoral district “inspections” are also an important part of the activities of congress delegates. During inspections, delegates share the decisions and plans of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the government with their electoral districts. Furthermore, based on the information collected during inspections, they submit bills, proposals, criticisms, and opinions to the people’s congresses. As a result of these submissions, the CCP and the government can learn about new developments in the society. Of course, PLA delegates are also engaged in these inspections.Footnote4

In order to reveal how the PLA expresses its interests at people’s congresses, this paper focuses on the bills, proposals, reviews, and opinions submitted by PLA delegates. To this end, let us consider why the PLA chooses this channel to submit its requests to the government.

There are many ways that the PLA can influence policy decision-makers such as the CCP and the government. For example, top PLA members attend CCP meetings. The Central Military Commission’s vice chairperson is also a member of the CCP’s Politburo. The meetings of the Politburo are probably the best opportunity for the PLA to communicate its requests to policy decision-makers. It is the same for the provinces: military region commanders and military sub-region commanders are also members of local party committees’ standing committees and their meetings are certainly an important opportunity for them as well (see and ). The PLA’s wishes are also likely communicated through personal networks that exist between the top PLA officials and the top government officials. People’s congresses are only one of several ways for the PLA to exercise its influence over policy decisions.

Table 2. The Standing Members of Jiangsu Provincial Committee of the CCP.

Table 3. The Standing Members of Yangzhou Municipal Committee of the CCP.

The analysis in this paper focuses on the activities of the PLA both at the NPC and local people’s congresses. Through interview surveys I conducted, I found that in the past, PLA delegates almost never submitted proposed bills and the like to local people’s congresses.Footnote5 However, PLA delegates have recently been doing so at local people’s congresses. Thus, I think it is important to also answer the question of why PLA delegates have come to do so in recent years.

This paper analyzes the PLA delegates’ motives behind submitting proposed bills and others forms of request to people’s congresses and discusses the relationship between the PLA and government agencies. However, from a substantive perspective, this is a discussion of the relationship between the PLA and society. This paper concludes that in recent years, in order to communicate its wishes and concerns to the government, the PLA has decided to submit bills, propositions, comments, and opinions to people’s congresses because PLA reforms have adjusted its relationship with society.

The present article is organized as follows. In Section 1, I clearly state the theoretical perspective of the function of nominally democratic institutions in authoritarian politics. Section 2, I review the previous studies on China’s authoritarian politics and China’s democratic institutions. Section 3, I provide an overview of the PLA delegates’ activities at people’s congresses in recent years. The purpose of the conclusion is I explain how the relationship between people’s congresses and society is changing while discussing the relationship between the PLA and government agencies.

2 The function of nominally democratic institutions in authoritarian politics

Why does the PLA choose the people’s congress as a tool to communicate its wishes to policy-decision makers? In order to answer this question, there is a need to understand the function of nominally democratic institutions (such as the people’s congress) in authoritarian politics.

There is considerable research on the political functions of nominally democratic institutions (legislatures, elections, political parties, etc.) within authoritarian politics that argues that these institutions play the role of maintaining the regime.

Svolik (2012) asserts that in authoritarian politics, leaders have political issues that they must solve in order to maintain the existing regime.Footnote6 In order to overcome these issues, political leaders use nominally democratic institutions.Footnote7 The first issue that must be overcome by political leaders is the sharing of power between themselves and other power-holders within the regime. Political leaders cannot steer a regime alone; instead, they create ruling circles in conjunction with these power-holders. When doing so, political leaders may become anxious that the other power-holders will become alienated and try to mount a political challenge. Thus, political leaders need to make sure other power-holders have the peace of mind they need and that they are secure in their loyalty.

The second issue political leaders must face is their relationship with the public. Political leaders may worry that the public surrounding them might also mount a challenge. Thus, there is the issue of how to prevent these challenges before they occur and how to obtain public support.

In order to overcome these issues, leaders in authoritarian regimes use nominally democratic institutions. Nominally democratic institutions in authoritarian politics have three political functions. Their first function is to prevent the alienation of power-holders within the regime. To ensure that the power-holders within the ruling circle will not become alienated, political leaders use nominally democratic institutions to provide them with peace of mind. They give the power-holders positions in certain institutions and promise to share their gains with them. By giving them positions based on institutionalized legislative and other such procedures, leaders become unable to arbitrarily deprive them of their positions. This is how power-holders within the regime maintain peace of mind.

The second function is to control and diminish (latent) anti-regime forces. For political leaders, nominally democratic institutions are opportunities to learn about, divide, and dissolve such forces. By selectively giving positions to members of forces that oppose the regime or that are within the regime and criticize its leader (latent anti-regime forces), individuals are divided and prevented from uniting.

The third function is the heightening of the effectiveness of governance. Through democratic systems, political leaders can collect the information necessary for policy decisions. Nominally democratic institutions are useful for understanding developments within the public, hearing society’s interests and discontent regarding policies, and establishing the policies necessary to prevent challenges from the public before they arise.

3 China’s authoritarian politics and nominally democratic institutions

As in nominally democratic institutions in other authoritarian regimes, people’s congresses in China have the political function of contributing to the maintenance of the existing system.

O’Brien sees people’s congresses as a way to rationalize rules and include society.Footnote8 The former refers to the development of regulations regarding governance, the legal institutionalization of political power, and restrictions on the political power of individual leaders. The latter refers to the CCP forming interest-based mutual relationships with various societal actors, incorporating them into the regime, and making the first move against political challenges to the CCP’s one-party rule as well as strengthening it. Cho points out that the CCP uses people’s congresses as sites for societal inclusion: delegates can directly exchange opinions with organs that represent the interests of specific groups.Footnote9 The submission of proposed bills and other documents by delegates functions to improve the effectiveness of the rule of law.

O’Brien categorizes delegates at the people’s congresses into three types.Footnote10 First, there are those who do nothing, understanding their position to be an honorary political post. He calls such delegates “inactives.” They are unrelated to heightening the effectiveness of governance. The second group consists of “agents.” These agents play the role of conveying CCP and state policies to their electoral districts. Third, there are “remonstrators.” These individuals, who are well-versed in the conditions of their electoral districts, share with the CCP and the government the developments in society and concerns regarding policies, both of which are needed by policy decision-makers to effectively do their jobs. O’Brien describes the activities of the latter two types of delegates abstractly as serving as “a bridge (qiaoliang) from the leadership to the citizenry.” He argues that in this way, through people’s congresses, the CCP can determine the location of cracks and conflicts in Chinese society and exert influence over the democratic parties (minzhu dangpai) and unaffiliated individuals that represent the middle and elite class.

Over the past 20 years, delegates at people’s congresses have come to function more as agents and remonstrators. It is unclear whether this is a result of reforms or the efforts of delegates themselves. The CCP has actively worked toward getting delegates to function as such. At the meeting of the leading cadres of the NPC and the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (National PCC) that was held in May 1990 (immediately after the Tiananmen Square protests), the CCP’s General Secretary, Jiang Zemin, argued that people’s congress delegates are indispensable “democratic channels” for “supporting the stability of society,” appropriately handle contradictions and problems that arise in the process of constructing socialism, “convey public opinion,” offer “a basis for Party and state policy decisions,” and so on.Footnote11 He said that the role of delegates should be “facilitating cooperation with the public,” conveying their “correct opinions to the top officials,” and, when encountering the public’s “clearly incorrect opinions,” “explain patiently and forcefully to convince” them otherwise for their benefit.

In a speech at a ceremony in September 2004 commemorating 50 years since the people’s congress system was established, Hu Jintao said the following regarding the role of delegates:

People’s congresses are widely representative, powerful organs of the state that are comprised of delegates from various fields. They are an important bridge that links the Party and the state with the masses. They are important channels for realizing ordered political participation that express the wishes of the people…Delegates need to construct close ties with the masses, listen to the voices of the masses, deeply understand the actual living conditions of people, fully reflect their will, and bring together the wisdom of the masses.Footnote12

Subsequently, the CCP sent out a notice to strengthen the function of the people’s congress as “an important bridge that links the Party and the state with the masses.” In April 2005, the Politburo released “Brief Comments on the Chinese Communist Party’s NPC Standing Committee Party Group Further Stimulating the NPC Delegates’ Activities and Strengthening the Construction of the NPC Standing Committee.”Footnote13

Tomoki Kamo has found that delegates not only act as agents and remonstrators but also “representatives” that represent the interests of their electoral districts.Footnote14 Rather than bridges that extend from the CCP and the government to Chinese society (such as agents and remonstrators), they are “bridges that extend from Chinese society to the Party and the government.” Unlike the former two types of delegates that aim to contribute to appropriate policy decisions by the CCP and the government, as representatives of their electoral districts, they aim to convey their districts’ wishes in the policy decision-making process of the CCP and the government.Footnote15

Research from the 1990s clarified that delegates function as agents and remonstrators, and research after the turn of the millennium shows that delegates also act as representatives. We can understand this development in relationship as a reflection of the expansion of delegates’ political functions, thus raising the question of why these functions changed in this way. Evidence has yet to be found to prove that the CCP strategically developed the functions of the people’s congress in order to adapt to the societal diversification accompanying the shift to a market-oriented economy, or that the people’s congress delegates themselves changed how they function in response to this diversification.

Of course, the expanded functions of the people’s congress can be seen as an accomplishment of the CCP’s reforms. The aforementioned statements by Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintiao as well as publications beginning in the 1990s advocated for the heightened function of people’s congresses. Furthermore, since the 1990s, the chairperson of the NPC Standing Committee has continued to serve as a member of the Politburo’s Standing Committee. The people’s congresses came to be seen as central actors in provincial politics. This is evidenced by the repeated trial-and-error reforms that have been carried out, for example, party committee secretaries serving as the chairs of local people’s congress standing committees and at other times, as the heads of local governments.

4 The activities of the PLA during the people’s congress

Why does the PLA choose to use the people’s congresses? Why do they submit bills, proposals, comments, and opinions during these sessions? To answer such questions, in this section, I analyze the submission of bills by PLA delegates to the NPC.Footnote16 I have chosen not to consider proposals, comments, and opinions because more rigorous conditions must be met to submit a bill.

In order to submit a bill, a delegate must obtain the signatures of over 30 other delegates who approve of its submission (including the submitter’s signature). When a delegate submits a proposal, comment and opinion, there is no need for co-submitters. As a result, bills are understood to represent the will of the people more broadly than proposals. Additionally, while proposals, comments, and opinions are also crucial items to analyze and understand the concerns of the PLA at certain times, bills are simply more important.Footnote17

The bills submitted by PLA delegates at the NPC can be generally divided into three types. Let us consider the bills submitted at the first session of the NPC’s tenth congress (213 in total) that was held in 2003. Materials for this session are relatively organized.Footnote18 First, there are bills relating to the development of the economy and society. These aimed to solve the issues that arose amidst the economic reforms and the establishment of the socialist market economy. These bills sought to establish or modify the laws regarding monopolies, communications, newspapers, compulsory education, national redress, crime, and the handling of labor disputes, and they also asserted the need for regional economic growth (the building of roads, the development of Western China, and so on). This category also includes bills that called for preventing and addressing environmental pollution and destruction arising from new construction in cities. (However, no such bills were submitted during the year in question.)

The second category involved proposed bills related to national security and foreign policy: anti-terrorism, national defense tax, national defense security, border management, the management of naval bases and surrounding ocean areas, military security concerns when building large-scale infrastructure, national defense construction, the protection of marine interests, and so on.

The third involves bills related to benefits for military members and their families. There were bills relating to the establishment of a national defense tax law, standards of pay and improvements of the benefits provided to military members and their families, assistance for military members in finding jobs after retiring from the military, and so on.

It appears that there is a correlation between the content of the bills and the background of the PLA delegates who submitted them. Of the 23 bills submitted by PLA delegates at the NPC during that year, 13 were related to economic and societal development. Of these, 10 were submitted by a person who had served as a vice minister at the Electronics Industry Ministry and Machinery and Electronics Industry Ministry and then subsequently, as vice-minister of the Commission for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense. This person is said to have consistently engaged in business related to the production and management of military arsenal. Furthermore, it appears that he recommended that the national defense industry be made private and worked to develop a Chinese-made color television.Footnote19

Furthermore, there were six bills related to national security and foreign policy. A bill related to the management of naval ports and surrounding ocean areas was drafted and submitted by an NPC delegate who was a vice admiral in the navy; an anti-terrorism bill was submitted by an NPC delegate who was the vice-commander of the Lanzhou Military District, and a national border management bill was submitted by an NPC delegate who was the Commander of the Inner Mongolia Military District. As can be seen, the content of the bills and the occupations of those who submitted them are related.

The same can be said for bills that involved benefits for military members and their families. The drafters/submitters were delegates with long careers in the PLA’s General Logistics Department and one had a long career as a political commissar (specifically, the vice political commissar of the Jinan Military District). In other words, the PLA delegates at the NPC with experience of being in charge of benefits for PLA members submitted such bills.

As is clear from the above explanation, PLA delegates are interested in diverse fields. Based on their knowledge, experiences, and interests, PLA delegates at the NPC and local people’s congresses express their concerns in the form of proposed bills. Why does the PLA communicate its wishes to the government through its delegates in the form of bills submitted to people’s congresses?

The third category of bills—those related to benefits for military members and their families—is useful in answering this question. Such bills are submitted every year to the NPC. In the same way, PLA delegates frequently submit related bills, proposals, comments, and opinions at the local people’s congresses. At the Yangzhou Municipal People’s Congress in Jiangsu Province, which is the subject of a long-term research project of mine, PLA representatives submitted six bills between 1998 and 2012, and 29 proposals, comments, and opinions.

The content can be divided into three categories: (1) PLA benefits and a safety net for its members after retirement, (2) road and living environment improvements in the areas in which PLA-related individuals live, and (3) other. While bills and the like related to national defense and security issues were submitted to the NPC, one does not find them in the local congresses. Rather, most of them are related to issues involving the lives of PLA members. Let us focus on the first two types of bills and the proposals, comments, and opinions.

The issues they address cannot be solved within the PLA (in this case, the Yangzhou Municipal military sub-district). For example, with regard to PLA member benefits and post-retirement safety net improvements, the government department in charge of civil affairs—which is in charge of supporting the military and providing benefits to the members’ families, as well as the post-retirement employment of former military members—handles such bills. Ministries related to transportation, construction, and environmental protection are in charge of road and living environment improvements.

It is imperative that the PLA consult and cooperate with the government if it wants to address such issues. In other words, for the PLA, the submission of bills proposals, comments, and opinions is an indispensable process to ensure that these issues are on the agenda and it also makes clear which ministry is in charge of addressing such issues.

5 Conclusion: the changing relationship between the PLA and society

In the past, the PLA did not submit bills, proposals, comments, and opinions. Why do they do so now? In the background are changes in the relationship between the PLA and society. The PLA once had a very close relationship with Chinese society. In addition to its original combat responsibilities, duties included political propaganda to garner public support as well as industrial activities for its economic survival.Footnote20

While there were plans to change it into an organization that focused entirely on the combat duties intrinsic to a military organization, after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, this plan was abandoned. During the rule of both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, the military’s involvement in industrial activities continued because the influence of the former leader “was deep-rooted” and “China itself lacked the financial, economic, and technological ability to convert this military into a modern military force.”Footnote21

Significant adjustments to the relationship between the PLA and society began in 1998. In April of that year, the Central Military Commission issued the “Implementation Opinion Regarding Non-Military Operation Units Not Engaging in Business Production.”Footnote22 As a result, in order to respond to concerns within the PLA regarding improved benefits for its members and their families as well as requests related to the improvement of roads and living environments where PLA-related individuals lived, state resources were needed. The resources of the PLA alone gradually became insufficient.Footnote23 This resulted in the need to submit these concerns to the people’s congresses in the form of bills, proposals, comments, and opinions.

The relationship between society and the PLA will likely continue to be adjusted in the future. A Ministry of Defense press release dated November 27, 2015 stated that the fee-based services provided to those not related to the PLA (e.g., the opening of military hospitals to the public, renting out military facilities, and the “Art and Cultural Troupe”) would cease, even though they were permitted to continue after the aforementioned 1998 hiatus of business/industrial activities.Footnote24 The halting of the Opera Troupe’s activities—which played the role of selling CCP policies to society—was symbolic of the adjustments that were made to the relationship between society and the PLA.

After the release of the aforementioned implementation opinion, the PLA’s place in Chinese politics and its relationship to Chinese society slowly began to change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tomoki Kamo

Dr. Tomoki Kamo is a Professor of Chinese politics and Foreign Policy at the Faculty of Policy Management at Keio University. His research and teaching focus on Chinese politics, comparative politics, and international relations of East Asia. He was a visiting scholar Graduate Institute of Political Science, National Taiwan Normal University (Taiwan) (2010) and Institute for Ease Asian Studies, Center of Chinese Studies, University of California, Berkeley (2011–2012) and a visiting associate professor of College of International Affairs, National Chengchi University (Taiwan) (2013–2013). Previously he served as a visiting research fellow at Consulate-General of Japan in Hong Kong (2001–2003) and studied at Fudan University (1995–1996). He was also appointed as a consul to the Consulate-General of Japan in Hong Kong (2016–2018). He received his B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. of Media and Governance from Keio University. His recent publication includes: Chinese Politics in Time (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2018; The Sources of China’s Foreign Policy (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2016; The Rise of China as a Superpower (in Japanese), Tokyo: Ichigeisya Press, 2016; From the Revolution to the Open Door Policy (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2011; Transition of China's Party-State System: Demands and Response (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2012; and Contemporary Chinese Politics and People’s Congresses: Reforms of People’s Congresses and Changes in the “Guiding-Guided” (Lingdao–Bei Lingdao) Relationship (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2006.

Notes

1 Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui, “Guanyu Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Junren Baoxianfa.”

2 Quangguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui, “Dijiujie Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui.”

“Electoral district” refers to the area that elects a delegate to a people’s congress, or the organization to which he or she belongs, such as their place of work.

4 Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui, “Quanguo Renda Jiefangjun Tuan Bufen Daibiao.”

5 Based on the interviews with individuals affiliated with the people’s congresses of G. Municipality (January 2002), W. Municipality (February 2002), Q. Municipality (March 2003), and Y. Municipality (August 2006).

6 Svolik, The Politics of Authoritarian Rule, 3–10.

7 See, for example, Gandhi and Ruiz-Rufino, Routledge Handbook of Comparative Political Institutions, and Kubo, Ken’ishugi Taisei ni okeru Gikai to Senkyo no Yakuwari.

8 O’Brien, Reform Without Liberalization, 5–6.

9 Cho, Y. N., Local People’s Congresses in China, Caps2-4.

10 O’Brien, “Agents and Remonstrators”, 359–380.

11 Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxian Yanjiushi, “Guanyu Jianchi he Wanshan renmin Daibiao Dahui Zhidu”, 940–947.

12 Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxian Bianji Weiyuanhui, 225–241.

13 Quanguo Renda Changweihui Bangongting and Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxuan Yanjiuhui. Renmin Daibiao Dahui Zhidu Zhongyao Wenxuan Xuanbian, 1362–1373.

14 Kamo, “Gendai Chugoku ni okeru Min’i Kikan no Seijiteki Yakuwari”, 11–46.

15 Individual delegates do not fall into only one category. Sometimes they might act as agents, and at other times as representatives. Alternatively, they might be remonstrators and representatives at the same time.

16 Japan’s National Institute for Defense Studies compiled China Security Report 2012 in which the PLA delegates’ submission of bills, propositions, comments, and opinions at the NPC is considered in detail.

17 PLA delegates in the NPC do not necessarily take an active approach to submitting bills. While the PLA boasts over 260 delegates at the NPC, the number of bills they submit is not high compared to delegates belonging to other delegations at the NPC. With that said, the bills submitted by PLA delegates involve issues that are widely seen as important within the PLA. They provide information necessary for understanding what the PLA is doing at the NPC.

18 Unfortunately, only the bills’ authors/drafters and titles have been publicly released, not concrete information on their content. See, for example,

19 Jiancha Ribao, April 17.

20 Hiramatsu,Chugokugun Gendaika to Kokubo Keizai, 75.

21 Ibid.

22 Komagata, ”Kaihogun Bijinesu to Kokubo Kogyo”, 351.

23 Hiramatsu (pp. 75–117) and Komagata (pp. 744–375) systematically explain the background to the expansion of the PLA’s industrial and business activities as well as the reasons that they came to be banned.

24 Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Guofangbu, “Guofangbu Juxing Shenhua Guofang.”

Bibliography

- Cho, Y. N. Local People’s Congresses in China: Development and Transition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Daxue, B. L. 2006. “Zhang Xuedong: Cong Guangchang Dao Jun”. [Zhang Xuedong: From Factory to the Army]. Jiancha Ribao [Procuratorate Daily], April 17. Accessed June 6 2018. http://www.bit.edu.cn/xww/rwfc/41665.htm

- Gandhi, J., and R. Ruiz-Rufino. Routledge Handbook of Comparative Political Institutions. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Hiramatsu, S. Chugokugun Gendaika to Kokubo Keizai [The Modernization of the Chinese Military and the National Defense Economy]. Tokyo: Keiso Shobo, 2000.

- Kamo, T. “Gendai Chugoku Ni Okeru Min’i Kikan No Seijiteki Yakuwari: Dairisha, Kangensha, Daihyosha, Soshite Kyoen” [The Political Role of Democratic Institutions in Present-Day China: Agents, Remonstrators, Representatives and Joint Performances].” Ajia Keizai 54, no. 4 (2013): 11–46.

- Kamo, T., and H. Takeuchi. “Representation and Local People’s Congress in China: A Case Study of the Yangzhou Municipal People’s Congress.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 18, no. 1 (2013): 41–60. doi:10.1007/s11366-012-9226-y.

- Komagata, T. “Kaihogun Bijinesu to Kokubo Kogyo (Gunmin Tenkan, Unmin Kenyo)” [The PLA’s Business Activities and the National Defense Industry (The Privatization of the Military Industry and Military – Civilian Inter-Operability).” In Chugoku Wo Meguru Anzen Hosho [On China’s National Security], edited by T. Murai, J. Abe, R. Asano, and J. Yasuda, 344–375. Vol. 351. Tokyo: Mineruva Shobo, 2007.

- Kubo, K. “Ken’ishugi Taisei Ni Okeru Gikai to Senkyo No Yakuwari: Tokushu Ni Atatte” [The Role of Legislatures and Elections in Authoritarian Regimes: On the Publication of the Special Issue].” Ajia Keizai 54, no. 4 (2013): 2–10.

- National Institute for Defense Studies. China Security Report 2012. Tokyo: National Institute for Defense Studies, 2012. Accessed June 6, 2018. http://www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/chinareport/pdf/china_report_EN_web_2012_A01.pdf

- O’Brien, K. Reform without Liberalization: China’s National People’s Congress and the Politics of Institutional Change. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- O’Brien, K. “Agents and Remonstrators: Role Accumulation by Chinese People’s Congress Deputies.” The China Quarterly 138 (1994): 359–380. doi:10.1017/S0305741000035797.

- Quanguo Renda Changweihui Bangongting and Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxuan Yanjiuhui. Renmin Daibiao Dahui Zhidu Zhongyao Wenxuan Xuanbian (Si), [Selected Works of People’s Congress System, Volume IV], 1362–1373. Beijing: Zhonggongzhongyang Zhuanfa ‘Zhonggong Quanguo Renda Changweihui, 2015.

- Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui. “Dijiujie Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui Falu Weiyuanhui Guanyu ‘Zhonghua Renmin Gonghehuo Lifafa’ (Cao’an) Shenyi Jieguo Baogao” [Report of the Law Committee of the National People’s Congress on the Results of Its Deliberation over the Draft Law of the People’s Republic of China on Legislation Law]. Zhongguo Renda Wang, December 17, 2000. Accessed June 6, 2018. http://www.npc.gov.cn/wxzl/gongbao/2000-12/17/content_5008937.htm

- Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui. “Jiefangjun Daibiaotuan Baosong Yi’an” [Bills of the PLA Delegation of the National Peoples Congress]. Di Shi Jie Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui Di Yi Ci Huiyi, March 2003. Accessed June 24 2016, http://www.npc.gov.cn/bill/proscenium!queryById.action?condition.dbtid=40AA4D59449F304EE04379000405304E&yajs=23

- Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui. “Guanyu Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Junren Baoxianfa (Cao’an) De Shuoming” [Explanation of on the Draft Law of the People’s Republic of China on Military Personnel Insurance Law]. Zhongguo Renda Wang, August 21, 2012. Accessed June 6, 2018. http://www.npc.gov.cn/wxzl/gongbao/2012-08/21/content_1736412.htm

- Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui. “Quanguorenda Jiefangjun Tuan Bufen Daibiao Dao Nanjing Shicha” [PLA Delegation of the National People’s Congress Arrived Nanjing Municipal]. Zhongguo Renda Wang, January 14, 2015. Accessed June 6 2018, http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/dbgz/dbhd/2015-01/14/content_1894256.htm

- Svolik, M. W. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxian Bianji Weiyuanhui. Hujintao Wenxuan Di Er Juan, [Selected Works of Hu Jingtao, Volume II], 225–241. Beijing: Remmin Chubanshe, 2016.

- Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxian Yanjiushi. Shisanda Yilai Zhongyao Wenxian Xuanji, Zhong, [Selected Works of Since 13th Party Congress, Volume II], 940–947. Beijing: Renmin Chubanshe, 1991.

- Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Guofangbu, “Guofangbu Juxing Shenhua Guofang He Jundui Gaige Zhuanti Xinwen Fabiaohui” [Defense Ministry’s Special Press Conference on National Defense and Military Reform]. Guofangbuwang, November 27, 2015. Accessed June 6 2018, http://www.mod.gov.cn/affair/2015-11/27/content_4635503.htm