ABSTRACT

The greatest achievement of ASEAN’s intra-regional economic cooperation since its inception in 1976 is the realization of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), which started with tariff cuts in 1993. AFTA was completed in January 2018 with the elimination of intra-regional tariffs. The AFTA itself is an FTA of an unusually high standard internationally, with the level of liberalization exceeding even that of the TPP 11. However, when examined from the aspect of utilization, in the case of Thailand’s exports to ASEAN, more than 30% do not use AFTA for one reason or another. This indicates that there are points of improvement in the system of the AFTA and in the customs procedures that are indispensable in using the AFTA. Furthermore, some member countries have introduced non-tariff barriers to protect their domestic industries while eliminating tariffs, which is contrary to the principles of AFTA. ASEAN has been expanding the scope of its economic cooperation since 2008 with the aim of establishing the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), but even so, what the industrial world is seeking in the “post-AFTA” periods are trade-related measures such as the “facilitation of customs procedures” and the “elimination of non-tariff barriers.” Nowadays, when mega FTAs such as RCEP and TPP11 is being constructed one after another, ASEAN needs to transform itself into the most advanced regional cooperation organization in terms of liberalization level, scope, and rules if it is to maintain its centripetal force for direct investment.

1 Introduction

The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was established at the end of 2015. At the ASEAN Economic Minister’s Retreat held in Malaysia from late February to March 2015, ASEAN described that “the formal establishment of the AEC by end-2015 marks a major milestone in ASEAN’s effort to fulfil the goal of an integrated region” and that the integration work would continue beyond 2015. At the 27th ASEAN Summit held in November 2015, the ASEAN Community Vision 2025, which includes an achieving of the ASEAN Economic Community by 2025 was adopted. This Vision comprises an accompanying document, the AEC Blueprint 2025, which sets out the integration process.

The economic integration process has been handed over from AEC 2015, which aimed to establish an economic community by the end of 2015, to AEC 2025, which aims to further strengthen the integration with a new target year of 2025. AEC 2025 states that the strategic direction of ASEAN’s economic integration in the next decade is to achieve “more deeply-and widely-integrated regional economy”.

The ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), which was launched in 1993 to eliminate tariffs within the ASEAN region, saw the first six member countries – ASEAN-6 – eliminate tariffs in 2010, followed by the partial elimination of tariffs by the ASEAN’s newer members, namely Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Viet Nam(CLMV) – in 2015. The remaining tariffs on particular items were also eliminated in January 2018, marking the great success of AFTA.

With the completion of AFTA where the elimination of tariffs on ASEAN-origin products was achieved, what do Japanese industries based in ASEAN seek in ASEAN integration? According to a survey done by JETRO, they do not foster high expectations on the gains from the liberalization of trade in services or the liberalization of movement of natural persons. Rather, it is the “further facilitation of customs procedures” that promote trade in goods, followed by the “elimination of non-tariff barriers” (See )Footnote1.

Table 1. Expectation toward the deepening of AEC (Top five items)

Since the completion of AFTA tariff elimination in 2018, ASEAN has focused on facilitating and simplifying tariff reduction and exemption procedures and trade procedures. Typical examples include the ASEAN-Wide Self Certification (AWSC) and ASEAN Single Window (ASW), which allows electronic exchange of certificates of origin, and ASEAN Customs Transit System (ACTS), which enables intra-regional bonded transit of multi-country shipments between member countries bordering. On the other hand, there have been moves that run counter to liberalization, such as the introduction of non-tariff barriers in line with the completion of AFTA (the removal of tariff barriers). The seeds of protectionism within the region must be steadily nipped in the bud so that ASEAN’s free trade is not described as “superficial liberalization”.

The institutions, rules of use, and trade facilitation measures that ASEAN has continuously developed and reviewed since the establishment of the AFTA have been transplanted into multilateral FTA frameworks such as ASEAN+1 FTA and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement signed in November 2020. ASEAN’s institutions and rules are propagated in the Asia-Pacific region. For example, the RCEP introduced the Declaration of Origin by an approved exporter and electronic format of certificate of origin, which ASEAN has been trying to introduce in the region in response to requests from industry. There are very few papers that refer to the role and centrality of ASEAN in the formation of FTA institutions and rules in the Asia-Pacific region. In addition, while it is said in various media reports that “RCEP is a framework led by China,” this paper aims to show that ASEAN has been constructing RCEP while demonstrating its centrality.

In light of these circumstances, this paper examines the efforts, achievements, and challenges to date concerning trade liberalization and trade facilitation measures, with a particular focus on trade in goods within the context of the “single market and production base” that was positioned as the core of the four pillars of AEC 2015 and the “highly integrated and cohesive economy” that was succeeded by AEC 2025.

2 ASEAN’s intra-regional FTA initiatives

2.1 Background to the establishment of AFTA

The idea of AFTA was first conceived at the 22nd ASEAN Economic Ministers’ Meeting held in 1990 when they agreed to adopt the concept of a unified and effective ASEAN preferential tariff on certain industrial products, including cement, fertilizer, and pulp. The following July, at the 24th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting in Thailand, Prime Minister Anand formally proposed the idea of AFTA. Thereafter, adjustments were made to the scope and content of the agreement, and at the 4th ASEAN Summit held on January 28th, 1992, the Framework Agreement on Enhancing ASEAN Economic Cooperation was adopted, in which the formation of AFTA within 15 years was specified.

Specific measures for the reduction of tariffs and the elimination of non-tariff barriers are set out in the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (AFTA-CEPT Agreement), which was adopted alongside the Framework Agreement on Enhancing ASEAN Economic Cooperation on January 28th, 1992Footnote2. The AFTA-CEPT Agreement is an initiative to create a free trade area within the ASEAN region through the elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers. The main objectives of the AFTA were (1) to strengthen the horizontal division of labor within the ASEAN region and increase the international competitiveness of local companies in ASEAN countries, (2) to expand the size of the market and secure economies of scale to attract foreign investment, and (3) to prepare for a global free trade systemFootnote3.

Regarding (1), when Prime Minister Anand proposed AFTA in 1991, a discussion paper prepared and distributed by the Thai government states that “freeing trade within ASEAN would attract investments and increase industrial exports, with multinational corporations setting up multi-plant operations in line with the globalization of industrial production”Footnote4.

Regarding (2), the so-called “South Tour Talks”, in which Deng Xiaoping, China’s supreme leader at that time, visited Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shanghai, and other cities in early 1992 to advocate a shift to a socialist market economy, raised expectations of an accelerated market economy and triggered a Chinese investment boom. ASEAN, which aims to achieve economic growth by leveraging foreign investment, became increasingly concerned about this trend.

Regarding (3), at that time, the world was in the midst of a trend toward the creation of regional economic blocs. In South America, an agreement on the establishment of MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market) was signed in March 1991, and in Europe, the Maastricht Treaty was signed in February 1992, giving birth to the European Union (EU). In North America, the United States and Canada signed a free trade agreement in 1989, and after preliminary negotiations with Mexico in 1990, the trilateral North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) negotiations began in 1991 and was signed in December 1992.

In response to these major changes in world affairs, ASEAN became increasingly anxious that “the ASEAN member-countries’ ability to compete effectively for markets and investments would be severely hampered unless they achieved the efficiencies of a large, integrated regional market”Footnote5 , which rationalized ASEAN to establish AFTA.

2.2 The acceleration and deepening of AFTA

ASEAN launched AFTA in 1993. It is important to note that AFTA, compared to modern FTAs, went beyond the initial commitments by widening the sector coverage, expanding the number of countries covered, and repeatedly accelerated tariff reductions, with the efforts of ASEAN members who unanimously focused on making AFTA attractive and comprehensive.

Initially, tariff reductions were applied to all manufactured goods, including capital goods and processed agricultural and fishery products, however, it excluded agricultural fishery-related items that were categorized as HS codes 01–24. In December 1995, about three years after the launch of AFTA, agricultural products were added to the list of items subject to tariff reductions. The background to this is closely related to developments in multilateral trade negotiations. The Uruguay Round of the GATT was concluded in December 1993, and the agricultural negotiations resulted in the reduction of protective measures, including tariffs. Based on this, ASEAN has been considering the inclusion of agricultural products in the AFTA, and it reached an agreement in the 26th ASEAN Economic Ministers Meeting (AEM)Footnote6. In the same year in 1995, Vietnam followed by Laos and Myanmar in 1997 and Cambodia in 1999, in conjunction with their accession to ASEAN.

Regarding the front-loaded tariff reduction schedule, it was decided that the target year for tariff reduction would be preponed to 2003, which is five years ahead of the initial target year of 2008, at the 5th AFTA Council Meeting held in September 1994. In particular, the Asian Financial Crisis, which occurred in July 1997 was a significant trigger for the repeated decisions to move up the tariff reduction schedule.

Due to the Asian Financial Crisis that spread throughout ASEAN from the plunge of Thai Baht in July 1997, many media commentators and academic analysts viewed that “ASEAN member-countries would retreat into their national shells because of the financial crisis” and that “AFTA, in fact, was dead”Footnote7. However, ASEAN, which was seriously concerned about the reduction of foreign investment from the area, repeatedly applied an accelerated tariff reduction schedule and emphasized their motivation toward tariff elimination.

At the 13th AFTA Council Meeting held in September 1999, the final target of AFTA was updated from 0–5% level to complete elimination of tariff. Furthermore, two months later, at the 3rd Informal ASEAN Summit held in the Philippines, it was decided that the timing of tariff elimination for ASEAN-6 and CLMV would be moved up by five years and three years to 2010 and 2015, respectively.

As aforementioned, while AFTA was viewed as “dead”, ASEAN was unified in this unprecedented crisis by holding a new ambitious target of tariff elimination and by accelerating and deepening the AFTA schedule and elimination deadline. This vigorous attitude of ASEAN was welcomed with surprise and praised by the international community.

In response to serious economic issues that could not be dealt with by a single country, as was the case with the Asian Financial Crisis, ASEAN strengthened intra-regional economic cooperation and encouraged collective action, such as setting out to enhancing liberalization. This has fostered ASEAN’s credibility as a desirable investment destination and has elevated the AFTA into an attractive FTA that emphasizes a high level of liberalization.

3 Implementation status and achievements of trade liberalization

3.1 Progress in the liberalization of trade in goods

Out of the many economic measures implemented by ASEAN, the industrial group paid the most attention to the liberalization of the movement of goods, the so-called AFTA. Initially, the AFTA-CEPT Agreement was an extremely short agreement with only 10 articles. After the agreement came into effect, due to changes in the economic environment, such as the Asian Financial Crisis, several protocols were adopted against the backdrop of various institutional changes, such as the expansion of the scope of the agreement and the acceleration of the reduction of AFTA preferential tax rates, through economic ministerial meetings and summit meetings. Also, among the various measures, there were some measures whose legal basis was ambiguous because there were only included in agreements made at the AFTA Council and Summit Meetings and in joint and press statements.

Based on this, ASEAN has consolidated all previous initiatives, obligations, and commitments on tariff and non-tariff intra-regional trade into one comprehensive document, the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA)Footnote8. This document consists of 11 chapters and 98 articles and has been institutionally upgraded to an FTA of international standard.

The goal of AFTA is to eliminate tariffs in 2010 for ASEAN-6, in 2015 for CLMV, and the remaining tariffs on 7% of the total number of items in 2018. Nevertheless, some unprocessed agricultural products that have been designated on the Sensitive List (SL) and Highly Sensitive List (HSL), and arms and ammunition classified in the General Exception List (GEL) are excluded.

AFTA was completed in January 2018, when CLMV eliminated tariffs on the remaining 7% tariff residual items. At the ASEAN Economic Ministers Meeting (AEM) held in September 2019, the liberalization rate of AFTA was 99.3% for ASEAN-6, 97.7% for CLMV, and 98.6% for ASEAN as a whole. This is a higher rate than the 98% level of TPP11, which has concluded.

In addition, an overview of the evolution of simple average AFTA preferential tariff rates allows us to reflect on the efforts of member countries to reduce tariffs. As seen in , simple average AFTA preferential tariff rates at six key points in the 25 years from the start of AFTA to its completion were measured: 1993, when the ASEAN-6 launched AFTA; 2003, when Declaration of ASEAN Concord II launched AEC and the tariffs on the items categorized in the Inclusion List (IL) was reduced to 0 to 5% level; 2008, when the integration process was launched based on the AEC Blueprint; 2010 and 2015 were the deadlines for the tariff elimination for ASEAN-6 and CLMV respectively; and finally, 2018 was the year of completion of AFTA. This table illustrates that ASEAN has been steadily working on tariff reduction for the past 25 years.

Table 2. Simple Average Preferential Tax Rate Trends

3.2 Usage of AFTA

The AFTA has become a high-level FTA representing Asia with very few exceptional items. Nonetheless, even if ASEAN develops the AFTA as part of its intra-regional economic cooperation, its significance is only proven through its usage by companies. For this reason, it is important to understand the actual status of AFTA usage by companies.

However, most of the ASEAN member countries do not disclose information related to the use of AFTAs. In this context, Thailand has disclosed the value of exports for which it has issued FTA certificates of origin. The FTA utilization rate (nominal FTA utilization rate) can be calculated by placing the export value for which FTA certificates of origin are issued by the country, published by the Thai Ministry of Commerce, in the numerator and dividing it by the Thailand’s export value to that country.Considering the steady reduction of intra-regional tariffs, the rate of AFTA use in Thailand’s exports to the ASEAN region has been increasing. As seen in , while the AFTA utilization rate in Thailand was less than 10% in 2000, the rate of usage has increased along with the tariff reductions, reaching approximately 40% in 2019. AFTA is mainly used on automobile-related products in Thailand. For example, five of the top 10 items in Thailand’s AFTA-using exports (on a six-digit HS basis) fall into that categoryFootnote9.

Table 3. Trends in the Usage of AFTA in Thailand’s exports to ASEAN

In particular, the usage of FTAs is progressing for ASEAN member countries with large population sizes. Specifically, exports to Indonesia and the Philippines account for about 70%, and exports to Vietnam, which once rose to about 65% in 2015, account for over 60% in 2019. Thus, AFTA has become an indispensable infrastructure for intra-regional exports.

Up to now, the procedures for obtaining a certificate of origin, etc. for FTAs have required the cooperation of many suppliers and other parties to obtain the various information necessary for certification of origin, which is a time-consuming and costly process. For this reason, there are many cases where FTAs are not used on purpose when the lot size is small, or the MFN tariff level is low. Therefore, when exporting to countries with large populations or high MFN tariff levels, the rate of FTA use tends to higher.

The AFTA utilization rates shown here are in nominal terms. This is because many countries, such as Singapore, have already eliminated tariffs on an MFN basis, and some items, such as electronics and electrical equipment, have eliminated tariffs on a global MFN basis through the World Trade Organization (WTO) Information Technology Agreement (ITA). Therefore, there are many cases where countries engaged primarily in the production and trade of IT-related products do not have an incentive to use FTA.

Indeed, according to the simple average MFN tax rate of ASEAN member countries, from the perspective of Thailand’s exports, the MFN tax rate is in the single digits for all countries except for Singapore and Brunei with almost 0% tax rate. Moreover, their share of MFN duty-free items is also 100% and 95.8%, respectively, hence there is no need to use AFTA for most items in exports to these two countries. On contrary, Malaysia’s simple average MFN tax rate is 5.6%, and its share of MFN duty-free items accounts for 66.3% of the total in terms of the number of items and about 80% in terms of the value of imports. As a result, Thailand’s AFTA utilization rate for Malaysia is also lower than that of the other ASEAN-6, excluding Singapore, and remains at around 30% (See ).

Table 4. Simple Average MFN tariff rates and tariff elimination rates for ASEAN member countries

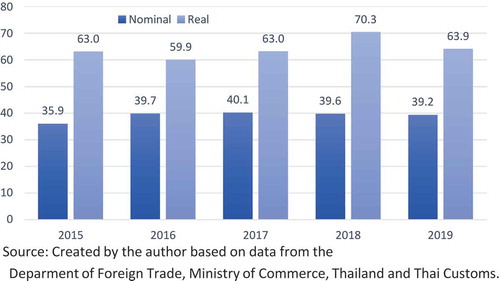

In calculating the aforementioned AFTA utilization rate, the “real utilization rate,” which is calculated by excluding MFN duty-free items and some items that are not covered by AFTA from the base export value, and using the export value of items for which AFTA can be used as the denominator, can confirm the actual status of AFTA use by companiesFootnote10(See ).

Although the real utilization rate exceeded 70% in 2018, it has generally remained in the low 60% range. Also, more than 30% of the value of taxable goods exports to ASEAN do not use AFTA for some reason. Among the FTAs that Thailand has concluded, the highest real utilization rate is in Australia (96.5% in 2007), which shows that AFTAs are often underused in exports to ASEAN compared to Japan (91.9% in 2007) and China (90.0% in 2007).Even though AFTA has a high level of liberalization, which is on par with TPP11, the real FTA utilization rate is low. One reason for this is that there are cases where import tariffs are exempted in the importing country due to investment incentives, especially when the relevant exports are integrated into the supply chain. Other reasons include a lack of awareness and understanding of the FTA system, especially among small and medium-sized companies and companies that handle small-lot cargo, and the fact that some companies consider the procedures involved in using FTAs to be cumbersome because of the cost and efforts required throughout the procedure that does not commensurate with the value of their exports.

In the survey conducted by JETRO in 2020, the most common reason given for not being able to use (or not using) FTAs was the “ignorance of systems and procedures,” which accounted for 42.6% of the total of 140 companies out of 329, followed by “not knowing whether the items are applicable or not” (109 companies, 33.1%). Hence, ASEAN countries must continue to provide basic information on the systems and procedures for using FTAs. Moreover, this was followed by “the volume and value of imports and exports are small” (92 companies, 28.0%), “procedures are complicated and costly (e.g., obtaining certificates of origin)” (17.0%, 56 companies) and “the administrative burden is excessive (e.g., checking whether rules of origin are met) at 12.2% (40 companies). Concerning AFTA, which has already achieved tariff elimination, constant efforts to improve the system are also necessary.

Improving procedures for the use of AFTA and trade facilitation within the region are essential to increase the real utilization rate. Although the AFTA was already completed in January 2018, ASEAN is working on improving the system, easing the conditions of use, and removing non-tariff barriers to encourage further use of the AFTA as part of the AEC 2025. The following section will review ASEAN’s efforts focusing on these aspects.

4 Improving the AFTA utilization system and trade facilitation

4.1 Shift of focus on facilitation from tariff elimination

Since 2008, ASEAN has been conducting integration work based on the AEC Blueprint 2015. The AEC 2015 has set four strategic goals: A) a single market and production base, B) a competitive economic region, C) equitable economic development, and D) integration into the global economy. In this context, the greatest achievement of AEC 2015 is the realization of AFTA. Besides, there has been numerous progress in strengthening physical, institutional, and human connectivity, and some of the CLMV are beginning to realize the benefits of integration, such as by being included in GVCs. With regard to the elimination of AFTA tariffs under the AEC 2015, the remaining issue to be resolved by the time the AEC was launched at the end of 2015, is the elimination of tariffs on some items of CLMV, which was scheduled for January 2018.Footnote11

The strategic objectives of AEC 2025 are now five pillars, with an additional one pillar from the four pillars of AEC 2015. Specifically, these are: A) a highly integrated and cohesive economy, B) a competitive, innovative, and dynamic ASEAN, C) enhanced connectivity and sectoral cooperation, D) a strong, inclusive, people-oriented, and people-centered ASEAN, and E) a global ASEAN. Of these, C) is the newly added goal where “a single market and production base” has been replaced by “a highly integrated and cohesive economy.”

A more specific implementation plan for AEC 2025 is the “AEC 2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan” (CSAP), which was approved by the AEC Council, composed of economic ministers, in February 2017. While AEC 2025 developed more detailed work plans for 23 areas, CSAP summarized the main measures in each area.

In terms of trade in goods under the strategic objective of “a highly integrated and cohesive economy,” the CSAP includes three Strategic Measures and 40 Key Action Lines. The first three strategic measures are: (1) strengthening ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) further, (2) simplify and strengthen the implementation of the Rules of Origin (ROO), and (3) accelerate and deepen the implementation of trade facilitation measures. Of the 40 major action plans for overall trade in goods, 32 measures were established under (3), indicating that the emphasis of trade in goods has shifted from tariff reduction and elimination to trade facilitation. In the following sections, we will review the efforts of each of these strategic measures.

4.2 Strengthen ATIGA further

The first strategic measure, “strengthen ATIGA further”, consists of the reduction or elimination of some leftover tariffs from the AFTA. The remaining issues from AEC 2015 to AEC 2025 are 1) elimination of tariffs on the remaining 7 percent tariff residual items deferred for CLMV; and 2) the reduction or elimination of tariffs on petroleum products, for which Vietnam and Cambodia have been granted special deferments. The latter is required to be eliminated by 2024 to 2025.

Regarding (1), in January 2018, CLMV eliminated tariffs on the tariff residual items, except for certain unprocessed agricultural products designated as SL or HSL items, and arms and ammunition under GEL. The number of items eliminated ranged from 640 to 670 in each country, with a total of 2,645 items in the four countries.

Apart from tariffs, research and examination of the applicability of automatic MFN (most-favored-nation clause) have been raised as part of the strengthening of provisions for the establishment of “ASEAN centrality.” In addition to the ASEAN+1 FTA, member countries have also concluded their own bilateral FTAs outside the ASEAN framework. Although the main focus lies in unprocessed agricultural products for which tariffs remain, in some cases, the FTA rates with these countries are lower than the rates provided by AFTA as seen in . If there is an automatic MFN clause that is limited to a small number of items, companies using AFTAs will automatically receive the lowest preferential rate. From the perspective of the companies, this would reduce the burden of using the FTA and increase the attractiveness of AFTA.

Table 5. Example of tariff rate reversal between AFTA and ASEAN+1 FTA (Vietnam)

ASEAN also aims to strengthen the ATIGA notification process. ATIGA Annex 1 identifies 13 measures that member countries are required to notifyFootnote12. Currently, member countries must notify the ASEAN Secretariat and the Senior Economic Officials Meeting (SEOM), however, this is not being done thoroughly and the regulations are being revised to allow reporting from other member countries.

4.3 Simplify and strengthen the implementation of the Rules of Origin (ROO)

The second of the three strategic measures for trade in goods under the CSAP of AEC 2025 is to “simplify and strengthen the implementation of the Rules of Origin (ROO).” This outlines three major action plans: a) enhancing the Rules of Origin (ROO), b) simplifying the certification procedures of origin determination, and c) encourage the utilization of Trade Facilitation platforms, in particular the mechanism already in place such as ASEAN Single Window (ASW), ASEAN Trade Repository (ATR), ASEAN Solutions for Investments, Services and Trade (ASSIST), etc.

With regard to a) enhancing the Rules of Origin (ROO), ASEAN is examining the possibility of introducing the full accumulation rules adopted in TPP11 into ATIGA. ASEAN has been reviewing its rules of origin intending to promote the use of AFTA. When AFTA was launched, the general rule of origin stated that the ASEAN Regional Value Contents (RVC) must be 40% or higher. However, in August 2008, in response to the needs of businesses, ASEAN decided to adopt a selective system with the Customs Tariff Change Criteria (CTC). As a result, when determining the origin of export items, companies can now be issued a Certificate of Origin Form D based on CTC rules as ASEAN origin if the CTC criteria are met, even for items that previously did not meet the 40% RVC threshold. In reviewing AFTA’s rules of origin, ASEAN encouraged AFTA to have greater flexibility than the ASEAN+1 FTAFootnote13. If the rules of the ASEAN+1 FTA are more liberalized for a particular product, the AFTA rules of origin have been adapted to the rules of the ASEAN+1 FTA. For CTCs in particular, most of them have introduced Change in Tariff Heading (CTH), which requires a four-digit change in the HS code.According to Medalla (Citation2015), the revised AFTA rules of origin are more liberal than those of other ASEAN+1 FTAs, with the Liberal Coequal Rule accounting for 84.3% of the total number of items (5,224)Footnote14. With the introduction of the selective system, companies no longer need to limit their procurement to local markets or the ASEAN region when using CTC, opening the door to global procurement and enabling companies to reduce the cost of managing rules of origin depending on the industry and item.

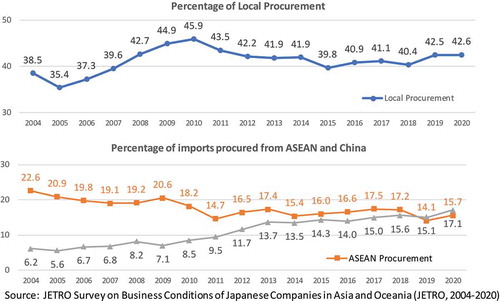

The impact of the introduction of the selective system in the rules of origin in 2008 can be glimpsed in the procurement of Japanese companies in ASEAN. The ratio of local procurement peaked in 2010 and has been on a downward trend, and the same is true for procurement within the ASEAN region. The FTAs promoted by ASEAN has produced solid results in “attracting investment” and “expanding exports through FTA usage by companies”. For example, the automobile industry made intensive investments in Thailand and Indonesia to establish major production and export bases and expanded exports from these bases to other countries in the region, but this was based on the reduction or elimination of intra-regional tariffs through the use of AFTA. On the other hand, the ratio of “local procurement” and “intra-regional procurement” has fallen, indicating that the expansion of local and intra-regional procurement and the development of industries, which were initially envisioned by ASEAN as part of the effects of concluding the FTA, have fallen short of their expectations ().

Regarding the “full accumulation rule” that ASEAN is considering to introduce, ASEAN introduced a similar rule in 2004. This is a “partial cumulation rule” that provides relief for items with a value-added of between 20% and 40%. In the case of intermediate goods with a value-added of “20% or more but less than 40%” that cannot be classified as originated in the contracting party, only the originating value of the intermediate goods can be extracted and accumulated. On the other hand, in the case of “full accumulation,” items that exceed the threshold are still considered to be of Contracting Party origin, and “roll-up” can be applied to accumulate the entire value of the intermediate good. For the items that do not meet the threshold, only the originating portion of the value of the intermediate goods can be accumulated, regardless of the percentage of value-added within the party. In other words, the lower limit of value-added within a contracting party, which is applied in the partial accumulation of AFTA is expanded to “over 0%.”

Additionally, when calculating the Regional Value Content (RVC) in the originality assessment for the use of AFTAs, the country concerned has been specifying whether to use the Indirect Method or the Direct Method. The Indirect Method calculates the percentage of origin by deducting non-originating materials from the free on board (FOB) price, while the Direct Method calculates the percentage of origin by calculating materials considered to be originating and the value-added at the relevant factory. If companies can choose which method to use depending on whether or not they receive information on origin from suppliers, etc., the rules will be more flexible for users.

With regard to b) simplifying the certification procedures of origin determination, in addition to further simplification of Form D and Operational Certification Procedures (OCP), the realization of the ASEAN-Wide Self-Certification (AWSC) Scheme has been set as a goal. The self-certification system does not require Form D issuance procedures, which is expected to reduce the workload and administrative burden on companies. It is also expected to improve the situation of stagnation in procedures due to differences in holidays among member countries, and the situation of cargo arriving at the customs office of the importing country before obtaining Form D, and cargo being held until the Form D arrival, which has been seen in either land or air transportation.

ASEAN has conducted two AWSC Pilot Projects (PP) of different nature: the first one, launched in November 2010, which is based on the current AFTA third-party certification system, and the second one, signed in January 2014, which is more restrictive and available only to manufacturers. However, the official introduction has been postponed due to the lack of sufficient examples in the PP of the second SC, which started late, and the need to revise the OCP. In the end, 505 companies in the region participated in the first SCPP, and 154 companies in the second SCPPFootnote15.

At the AEM held in August 2018, the ATIGA Revised Protocol I was signed based on the implementation of the AWSCFootnote16. Member countries continued to go through the ratification process, and Brunei, as the tenth and final country, notified the ASEAN Secretary-General of the completion of its national procedures on August 21st, 2020, which led to the implementation of the ASWC 30 days later, on September 20th, 2020. The AWSC is available to “certified exporters” (CE)Footnote17 , who register their CEs with the ASEAN Secretariat’s AWSC-CE Database, allowing importing countries to verify and confirm their CEs.

In principle, the AWSC can be used for any transaction type allowed by the current Form D by providing the necessary information. CEs will usually prepare a “declaration of origin” on the invoice. When a third country (or a company) intervenes in the transactions between the exporting country and the importing country through intermediary trade, etc., the invoice obtained by the importing country is issued by the third country company and does not contain a “declaration of origin.” In such cases, the exporter can make a “declaration of origin” on commercial documents other than the invoice, such as billing statements (B/S), delivery order (D/O), and packing list, which can be used in intermediary trade.

Furthermore, successive certificates of origin, so-called the Back to Back Certificates of origin, which are used in transaction patterns where both commercial flow and logistics are via a third country (intermediate country), can be used as a “Back to Back Declaration of Origin.” The exporter in the country of origin needs to obtain a “declaration” from the manufacturer and a valid certificate of origin. Although there are several conditions attached to this system, such as those companies exporting to the region using the system in intermediate countries where inventory is stored must also obtain CE certification, the system is available for this type of transaction.

Some elements of the second SCPP have also been adopted. The number of signatories who can make a “declaration of origin” has been increased to 10 but is still limited. In the declaration of origin, the signatory is required to certify that the designated goods meet all the requirements and to sign the declaration in his or her handwriting on a piece printed or stamped with the signatory’s name. Adding to that, the “declaration of origin” is required to state information such as export items, HS codes, and the origin criteria used in the determination as listed in .

Table 6. Major differences between first and second SCPP and the AWSC

The AWSC is also designed to be less burdensome for companies in terms of compliance. Unlike the self-certification system introduced by Japan and other countries, the examination of origin itself is conducted by the competent ministry as before, and companies only need to make a “declaration of origin” themselves at the time of export.

Finally, the ASEAN Single Window (ASW) is a representative example of c) encourage the utilization of Trade Facilitation platforms. ASW is an initiative to significantly reduce the time and cost of customs procedures by having trade-related documents and information electronically and centrally accepted and processed, and by having them instantly transmitted to the relevant organizations through the centralized contact point in the importing country after the centralized decision-making on customs clearance.

For ASW, the exchange of e-ATIGA Form D, electronic certificates of origin, began in January 2018 in five countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Since then, countries that have not yet joined the program have gradually joined with a delay, and with the participation of Laos as the tenth and final country in August 2020, the exchange has begun in ten countries. In the future, following the exchange of e-ATIGA Form D at ASW, exchange tests for electronic ASEAN Customs of Declaration Document (ACDD) and electronic Sanitary and Phytosanitary Certification (e-Phyto) will be launched in sequence. In the meantime, the expansion of electronic certificates of origin is being considered. In the future, the ASEAN+1 FTA is also expected to gradually begin negotiations with dialogue countries to introduce electronic certificates of origin.

4.4 Accelerate and deepen the implementation of trade facilitation measures

The last of the three strategic measures in trade in goods under the CSAP of AEC 2025 is to “accelerate and deepen the implementation of trade facilitation measures.” It is divided into four major areas: (1) trade in goods, (2) trade facilitation, (3) customs, and (4) Standards, Technical Regulations and Conformity Assessment Procedures (STRACAP).

In particular, in area (2), ASEAN aims to reduce trade transaction costs by 10% by 2020, double intra-ASEAN trade in 2025 compared to 2017, and improve the performance of its members, including their international rankings of the World Economic Forum and the World Bank through the implementation of the Action Plan. It sets out seven strategic objectives and outlines actions to be taken under these objectives as listed in .

Table 7. Seven Key Action Plans under AEC 2025 Trade Facilitation Strategic Action Plans

In terms of actions to be taken, the report also addresses non-tariff measures (NTMs)/non-tariff barriers (NTBs)Footnote18 , which were not well addressed in AEC 2015. It specifies “standstill” which means that mutual notification in NTMs should be ensured and that no new trade-restrictive measures should be introduced, “rollback” which means that existing trade-restrictive measures should be reduced or eliminated gradually, and guidelines that should be developed for assessment to identify NTMs that have elements of trade barriers.

As mentioned earlier, AFTA was completed in January 2018, and the liberalization of trade in goods through the elimination of tariffs is ASEAN’s greatest achievement. However, there are still issues to be addressed in order to become a “truly free trade area.” Among them, the greatest challenge is the persistence and proliferation of NTMs and NTBs. Even if tariffs are eliminated, if new NTBs are introduced or remain, they will hinder the free flow of goods that has been promoted under AFTA.

New NTMs and NTBs were introduced in January 2018 to replace the elimination of tariffs of CLMV and the completion of AFTA. Specifically, in October 2017, prior to the elimination of tariffs in January 2018, Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade issued Decree 116, requiring emission and safety inspections for each import lot (a vessel) by vehicle type, as well as submission of a Vehicle Type Approval (VTA) issued by the government of the producing country. Although the Vietnamese authorities have stated that the purpose of introducing these regulations is to “protect consumers and the environment,” it is clear that the purpose is to restrict automobile imports. While promoting the elimination of tariffs, the NTBs were introduced to protect the domestic industry.

Since then, major automobile producing countries in ASEAN have raised this issue with the Coordinating Committee on the implementation of ATIGA (CCA), and several private companies have filed complaints through the ASEAN Settlement on Investment, Services, and Trade (ASSIST). ASSIST is a web-based system for the private sector to file complaints when they encounter obstacles in trade, investment, and service sectors. If the complaint is formally accepted, they will be notified of corrective measures within 60 daysFootnote19.

The companies that were most affected by the issuance of Decree 116 by Vietnam are Japanese automobile companies that have been reorganizing their bases and formulating regional strategies on the premise of the completion of the AFTA in January 2018. Concerning this regulation, an executive from the ASEAN regional office of a major Japanese automobile company said “Decree 116 was a surprise to us.” In fact, in January 2017, Toyota Motor Corporation switched to importing CBU(Completely Build Up) from Indonesia for the “Fortuner,” a passenger pickup vehicle (PPV) developed based on a pickup truck that it had been producing CKD(Completely Knocked Down) in Vietnam, on the assumption that the AFTA would be completed in January 2018. However, following the sudden announcement of Decree 116, it became difficult to import the same vehicle from Indonesia after January 2018. As a result, Toyota was at the mercy of the Vietnamese government, as it was forced to move the “Fortuner” assembly line back to Vietnam in May 2019.

Indonesia’s Trade Minister Lukita, who has strongly urged the revision of the regulations, has so far pressured the Vietnamese government that he will file a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) if it does not comply with the revised regulations (statement dated February 28 2018)Footnote20. In the meantime, the Thai and Indonesian governments, as part of their efforts to support companies’ exports, issued special VTAs at the request of exporters, and exports of CBU vehicles from both countries to Vietnam resumed about four months later. With the issuance of Decree 116, exports of finished vehicles to Vietnam were suspended for a time, but the Thai and Indonesian governments worked with the private sector, and exports of finished vehicles gradually resumed. As the effect of Decree 116 on import restrictions waned, the Vietnamese government amended the Decree in February 2020, removing the obligation to submit VTAs and easing inspections by import lot and model to once every 36 months.

Notwithstanding, the Vietnamese government is currently considering new measures. In Notice No.377 dated November 11 2020, Deputy Prime Minister Trinh Dinh Dung instructed the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, and other relevant ministries to propose measured to enhance tax incentives, including the Special Consumption Tax (SCT), to promote the domestic automobile industry and lead to industry development. The review of the SCT has been on the agenda for discussion since around 2019. Although the SCT rate was determined by displacement, the Ministry of Industry and Trade is considering raising the tax rate but excluding the value of locally procured parts from the tax base (vehicle price)Footnote21. The SCT itself may be regarded as a de facto import tariff, in which case it may be accused of violating the WTO’s principle of national treatment.

If ASEAN neglects Vietnam’s introduction of these measured, there is a concern that other member countries will follow suit by adopting similar measures in the future. Indonesia followed Vietnam’s Decree 116 by effectively imposing restrictions on the volume of automobile imports in the fall of 2018. If protectionist measures spread in a chain reaction to ASEAN, which has long been a promoter and beneficiary of free trade, ASEAN itself may lose its reputation and its centripetal force for direct investment in response to its pro-free trade stance.

ASEAN has no devolved powers, and sovereignty is vested in each member country. Hence, if a member country seeks to introduce measures that go against liberalization, such as NTBs, the other member countries are limited in what they can do, such as exerting peer pressure. As for NTBs/NTMs, ASEAN has so far committed to the elimination of NTBs with a deadline under AEC 2015. However, in reality, the number of NTBs/NTMs has been increasing year by year, showing the limitations of ASEAN without intervention authority. For example, the introduction of NTM must be reported to ASEAN, and the website of the ASEAN Secretariat discloses the reported NTMs as the “Non-Tariff Measures Database.” From 2011 to June 2020, 868 NTMs were reported to ASEAN, and the number of reported NTMs has been increasing every year since the completion of AFTA in 2015Footnote22. In this context, ASEAN approved the “Guidelines on NTMs/NTBs” at the 32nd AFTA Council Meeting in August 2018. The purpose of the guideline is to a) improve the transparency and management of NTMs in accordance with the rights and obligations of ATIGA and the WTO, and b) provide a general framework to enable ASEAN members to pursue their legitimate policy objectives while minimizing the trade-distorting effects of NTMs. Five principles are put forward here: (1) necessity and proportionality, (2) consultation and engagement, (3) transparency, (4) nondiscrimination and impartiality, and (5) periodic review.Footnote23

The guideline states that NTMs shall be ensured that they are not more restrictive than necessary to achieve legitimate public policy objectives and that member countries preparing legislation shall endeavor to implement a pre-qualification procedure based on the Regulatory Impact Assessment methodology or a similar methodology for (1). It also states that member countries shall endeavor to provide appropriate opportunities and timeframes for stakeholders in their countries and other member countries to comment on the proposed draft NTM and to consult with affected national stakeholders for (2). For (2), it states that member countries should notify the Senior Economic Officials’ Meeting (SEOM) and the ASEAN Secretariat at least 60 days before the entry into force of any measure introduction or amendment, and to provide an opportunity for prior consultation with other member countries before the measure is adopted. Again, this is only a guideline and is not legally binding. NTMs/NTBs remains the biggest challenge in realizing a true AFTA.

4.5 Facilitation of intra-regional border trade

Trade facilitation is mainly focused on border measures such as customs procedures, but efforts are also being made for cross-border transportation. In particular, the five ASEAN countries located in the Mekong region, and Malaysia and Singapore, which are connected to the South through Thailand have been making these efforts. Although the East-West Economic Corridor, Southern Economic Corridor, and other cross-border road networks have been developed, there have been various issues on the soft infrastructures, such as customs clearance at border crossings and procedures for passing through some countries.

ASEAN signed the ASEAN Framework Agreement on the Facilitation of Goods in Transit (AFAGIT) in December 1998, and it entered into force in October 2000. However, the details of matters necessary for its implementation are to be outlined in nine Annexed Protocols, which need to be signed and ratified separately. Many of these protocols have been gradually signed and entered into force since the end of the 1990s. Among them, Protocol No.7 on transit customs clearance, which is essential for transit shipments across multiple countries, was finally signed in 2015. With the signing of the Protocol, the ASEAN Customs Transit System (ACTS) is now ready for implementation.

ACTS is a system that allows for bonded transportation in intermediate countries for cross-border transportation between three or more countries. There is no need to make different customs declarations at each border, and no need to transship goods to different vehicles in each country. Transportation experiments have been conducted through the North-South Economic Corridor and the East-West Economic Corridor, and the system officially started operation (live operation) in November 2020. Except for Myanmar, which will join the project later, the six participating countries will be connected by land routes. To use the system, it is necessary to register as a transit trader with each country’s customs office, which can be an importer or exporter, freight forwarder, carrier, or subcontractors, or a customs broker. In addition, if you are certified as an Authorized Transit Trader (ATT), you can start transporting transit cargo from your facilities and even make the destination your facilities.

Based on business needs, there are plans to expand the service to Indonesia, the Philippines, and Brunei, which use other transport modes such as maritime transport. As in the case of ASEAN, the European Union (EU), which has expertise in transporting goods between multiple countries by land, has been developing the environment as part of its ASEAN Regional Integration Support from the European Union (ARISE).

5 Conclusion

Although AFTA began with the start of intra-regional tariff reduction in 1993, the level of liberalization has surpassed even that of TPP11, making it an FTA with a high level of liberalization rarely seen internationally. As mentioned above, at the time of its creation, the purpose of the AFTA was to “attract investment and increase exports of industrial products through the operation of multiple factories by multinational corporations in response to the globalization of industrial production.” At the time, Japanese companies were the main players with multiple bases in ASEAN and complementing each other among their bases. In fact, with regard to the ASEAN Industrial Cooperation (AICO) scheme, an accelerated measure of AFTA preferential tariffs of 0–5% or less, the majority of the companies using the scheme were Japanese automobile companies. In this sense, it can be said that ASEAN and Japanese companies have been working together to promote economic cooperation in the region.

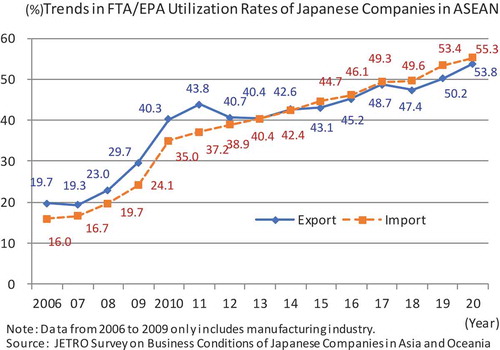

Looking at the use of FTAs by Japanese companies in ASEAN according to the survey conducted by JETRO, the FTA utilization rate by companies in ASEAN has been rising steadily; in the 2020 survey, 53.8% of the companies responding to the survey used FTAs for exports, and 55.3% for imports (See ). Among the FTAs that ASEAN has concluded, AFTA is the most used. Of the Japanese companies in ASEAN that import and export within the region (732 exporters and 695 importers), 58.1% (425 exporters) and 57.6% (400 importers) use the AFTA.

In November 2020, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed after eight years of negotiations since the declaration of the launch of negotiation in late 2012. RCEP is the world’s largest FTA, encompassing about 30% of the world’s economy and population each, with ASEAN at its center. As the RCEP, TPP11, and other mega-FTAs come to fruition one after another, ASEAN needs to emerge as the most advanced regional cooperative organization in terms of the level and scope of liberalization within this framework to maintain its centripetal force. With five years remaining until AEC 2025, ASEAN’s centrality will be maintained by accelerating and deepening its integration and steadily accumulating achievements.

Additional information

Seiya Sukegawa is Professor at the Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Kokushikan University, Tokyo Japan. He is Ph.D. in Economics, Graduate School of Economics,Kyushu University. He joined Japan External Organization (JETRO) . After assuming the position of Senior Director for global strategy, ASEAN at JETRO, he joined the Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Kokushikan University as a Associate Professor. His research focuses on economic integration of ASEAN, FTA strategy of ASEAN, and International Economics. His recent publications include Tanitsuno sijo to seisankichi wo mezasu ASEAN:AFTA niyoru boueki jiyuuka wo chushin ni [ASEAN aiming for “single market and production base”:Focusing on trade liberalization by AFTA],JAAS Ajia Kenkyu(Asian Studies)Vol.62, No.3(2016) and The Actual Condition of FTA Utilization and Improvement Measures of Japanese Firm in ASEAN, KETRI(Korea E-Trade Research Institute) E-Trade Review Vol.16, No.3 (2018) . He is a co-editor of publications on ASEAN Integration including ASEAN Keizaikyodotai no jitsugen to Nihon [ASEAN Wide Market Integration and Japan],Tokyo:Bunshindo,2014.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 JETRO(2018), “Survey on Business Conditions.”

2 Preferential tariffs granted under AFTA are sometimes referred to as “CEPT tariffs” because they were initially tariffs under the AFTA-CEPT Agreement, and “ATIGA tariffs” after the AFTA-CEPT Agreement was replaced by the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010. To avoid confusion, the term “AFTA preferential tariffs” or “AFTA tariffs” will be used throughout this chapter.

3 Hayashi, “AFTA to wa?” 36.

4 Severino, Southeast Asia in search, 223.

5 Severino, Southeast Asia in search, 223.

6 ASEAN, AFTA Reader Volume II.

7 Severino, Southeast Asia in search, 226–227.

8 ATIGA was signed in February 2009 and came into effect in May 2010.

9 According to the Foreign Trade Administration of the Ministry of Commerce, the top exports using AFTA in 2019 are commercial vehicles (diesel type/weight 5 tons or less), Cane or beet sugar, passenger motor vehicles (diesel type/1,500–2,500 cc), Petroleum oils and oils obtained from bituminous minerals (excluding crude oil) and their preparations (excluding light oil and its preparations), air conditioners (window or wall types), passenger motor vehicles (gasoline type/1,000–1,500 cc) Air conditioners (for window or wall mounting), passenger motor vehicles (gasoline type/1,000 to 1,500 cc), passenger motor vehicles (1,500 to 3,000 cc), mineral water and other types of engines used to vehicles of HS87, polypropylene.

10 Thailand’s Department of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Commerce, releases only the export value of ASEAN as a whole.

11 See “รายงานสถานการณ์การใช้สิทธิประโยชน์ทางการค้าภายใต้ความตกลง FTA[Report on the use of commercial benefits under the FTA agreement] ” of the Department of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand.

12 These include: a)Tariffs; b)Quotas; c)Surcharges; d)Quantitative restrictions; e)Other non-tariff measures; f)Customs valuation; g)Rules of Origin; h)Standards, Technical Regulations and Conformity Assessment Procedures; i)Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures; j)Export taxes; k)Licensing Procedures (import and export); l)Foreign exchange controls related to imports and exports; m)Application of the ASEAN Harmonized Tariff Nomenclature beyond the 8-digit level for tariff purposes.

13 The 20th AFTA Council Meeting held on August 21 2006.

14 Excludes alternative rule of CTC 2digit and RVC, which is inferior in terms of flexibility. The other ASEAN+1 FTAs are AKFTA with 79.2%, AJCEP with 59.2%, and AANZFTA with 67.0%, which are lower than AFTA.

15 Referred to the AWSC workshop document, “ASEAN-wide Self-Certification (AWSC) Overview and benefits,” held by the ASEAN Secretariat on September 15 2020.

16 According to Mr. Rong Narong, Deputy Director-General, Trade Negotiation Department, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand, only seven countries were able to sign on the same day (interview, September 3 2018). The final signing by all member countries was completed on January 22 2019.

17 The competent authorities of the member countries will recognize those companies that wish to use the AWSC that have expensive experience in export procedures, are manufacturers or exporters with a good understanding of ATIGA’s rules of origin requirements, have no record of false applications related to rules of origin, and have a good compliance system for risk management, as CEs.

18 According to “Guidelines for the Implementation of ASEAN Commitments on Non-Tariff Measures on Goods”, NTMs is defined as policy measures other than customs tariffs that can potentially have an economic effect on international trade in goods, changing quantities traded, or prices or both. On the other hand, NTBs are defined as measures other than tariffs, which effectively prohibit or restrict imports or exports of goods within Member States.

19 However, ASIST is only a non-binding “consultative mechanism” and is expected to play a complementary role to the ASEAN Protocol on Enhanced Dispute Settlement Mechanism (EDSM).

20 In the end, no WTO dispute settlement has been filed in this case. However, according to the Weekly Thai Economic Bulletin of July 17 2019, the case was reported to the WTO’s Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Committee) in Geneva in June 2019, according to Mr. Wanchai, Director-General of the Industrial Product Standards Office, Ministry of Industry, Thailand.

21 For details, please refer to https://vietnamnet.vn/vn/oto-xe-may/tin-tuc/xe-noi-thua-xe-nhap-gia-re-2-nam-de-xuat-uu-dai-thue-tieu-thu-dac-biet-o-to-van-dam-chan-569347.html。

22 However, some countries, such as Vietnam, have introduced NTM without notifying ASEAN in the past, but there are some cases in which the past NTMs were reported together at one time, so the year of NTM implementation may differ from the year of notification.

23 See “รายงานสถานการณ์การใช้สิทธิประโยชน์ทางการค้าภายใต้ความตกลง FTA[Report on the use of commercial benefits under the FTA agreement] ” of the Department of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand.

Bibliography

- ASEAN. “AFTA Reader Volume II, March 1995.” Accessed February 28, 2021a. https://asean.org/?static_post=industry-focus

- ASEAN. “ASEAN Economic Integration Brief, No.05/June 2019.” Accessed December 30, 2020a.https://asean.org/storage/2019/06/AEIB_5th_Issue_Released.pdf

- ASEAN. “ASEAN Economic Integration Brief, No.08/November 2020.” Accessed December 30, 2020b. https://asean.org/storage/AEIB_No.08_November-2020.pdf

- ASEAN. “Guidelines for the Implementation of ASEAN Commitments on Non-Tariff Measures on Goods”. Accessed February 28, 2021b. https://asean.org/storage/2018/12/Guidelines_for_the_Implementation_of_ASEAN_Commitments_on_NTMs-July_2018-AEM-AFTAC_32.pdf

- ASEAN. “Joint Press Statement of the 22nd ASEAN Economic Ministers’ Meeting,” Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia on 29-30 October 1990. Accessed December 30, 2020c. https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/formidable/18/1990-22nd-AEM.pdf

- Hayashi, T. “AFTA to Wa?” [What Is AFTA?].” In AFTA: ASEAN Keizai Tougou No Jitsujyou to Tenbou [AFTA (ASEAN Free Trade Area): The Actual Situation and Prospects of ASEAN Economic Integration], edited by T. Aoki, 35–36. Tokyo: Japan External Trade Organization, 2001.

- Ishikawa, K., S. Kazushi, and S. Seiya. Asean Keizaikyoudoutai: Higashi Ajia Tougou No Kaku to Nariuruka? [ASEAN Economic Community: Can It Become the Core of East Asian Integration?]. Tokyo: Japan External Trade Organization, 2009.

- Ishikawa, K., S. Kazushi, and S. Seiya. ASEAN Keizaikyoudoutai to Nihon: Kyodai Shijyou No Tanjyou [ASEAN Economic Community and Japan: The Birth of a Giant Integrated Market]. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2013.Ishikawa, Koichi, Shimizu Kazushi, and Sukegawa Seiya. ASEAN Keizaikyoudoutai No Sousetsu to NIhon [Realization of the ASEAN Economic Community and Japan].. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2016.

- Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). “2018 JETRO Survey on Business Conditions of Japanese Companies in Asia and Oceania.” Accessed February 28, 2021. https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/en/reports/survey/pdf/rp_firms_asia_oceania2018.pdf

- Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). “2019 JETRO Survey on Business Conditions of Japanese Companies in Asia and Oceania.” Accessed December 30, 2020. https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/en/reports/survey/pdf/rp_firms_asia_oceania2019.pdf

- Kasuga, H. “Thailand-Malaysia Rikuro Tsukan 24Jikan Taisei E.” [Thailand-Malaysia border Customs will be open 24 hours.] World Economic Review IMPACT No.1415, 2019, Institute for International Trade and Investment. Accessed December 30, 2020. http://www.world-economic-review.jp/impact/article1415.html

- Medalla, E. M. “Toward an Enabling Set of Rules of Origin for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership” Discussion Paper Series №2015-29.Manila: Philippine Institute for Development Studies, 2015.

- Severino, R. C. Southeast Asia in Search of an ASEAN Community: Insight from the Former ASEAN Secretary-General. Singapore: Institute of South East Asia Studies (ISEAS, 2006.

- Sukegawa, S., “Asean No Jiyuuboueki Kyoutei (FTA): AFTA Wo Chyushin Ni.” [Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of ASEAN: Focusing on AFTA]. PhD diss., Kyushu University, 2019.