ABSTRACT

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has been leading economic integration within many structural changes in the world economy. ASEAN, established in 1967, has promoted regional economic integration since 1976. It started to work toward realizing the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) in 1992 and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2003. ASEAN finally established the AEC at the end of 2015. The AEC is the most developed and advanced economic integration in East Asia. ASEAN is deepening the AEC for the next goal, AEC 2025. ASEAN also led East Asian cooperation initiatives, including ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6, and ASEAN+1 FTAs. ASEAN proposed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and led the RCEP negotiations. Currently, rising protectionism and the US–China trade friction has great negative impacts on ASEAN and East Asia. Furthermore, the outbreak of COVID-19 has done great damage to ASEAN and East Asia. ASEAN is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and strengthening the AEC steadily amidst growing protectionism and COVID-19 pandemic. The RCEP agreement was finally signed in November 2020. The RCEP is the first East Asian mega FTA. The RCEP has great meaning in ASEAN and East Asia. ASEAN secured ASEAN centrality in East Asian economic integration. The AEC and the RCEP will become more important amidst rising protectionism, and during and in the post-pandemic era.

1 Introduction

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has been leading economic integration in East Asia, the fastest growth center in the world economy. ASEAN was established in 1967 and has promoted regional economic integration since 1976. It started to work toward realizing the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) in 1992 and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2003. At the end of December 2015, ASEAN finally established the AEC. The AEC’s goals include the free movement of goods, services, capital, investment, and skilled labor, and narrowing the economic gap and many other issues. The AEC is the most advanced economic integration in East Asia. The AEC is promoting ASEAN and East Asian economic development. In 2015, ASEAN set the new goal, AEC 2025. ASEAN has also been the hub of East Asian multi-layered cooperation initiatives, including ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6, and ASEAN+1 free trade agreements (FTAs). ASEAN proposed and had been leading negotiations of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Currently, the world economy is extremely difficult. Protectionism and trade friction are expanding worldwide. The United States (US) has increased trade friction with China and other countries. The spread of protectionism and trade friction has a major negative impact on the world economy. The evolving East Asian economy has been hard hit. Furthermore, recently, coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has greatly damaged the world and East Asian economies. In November 2020, the RCEP agreement was finally signed by 15 East Asian countries. This might signal turning points for the future.

This special issue focuses on the AEC and East Asia in the changing world economy. The AEC is striving to continue economic development in ASEAN and East Asia. This issue examines the AEC from various aspects, including the AEC’s background. The authors have been studying ASEAN integration and the AEC for a long time. They are members of the ASEAN Study Group in Tokyo (ASGT) in the ASEAN Japan Center (AJC): Shimizu (the chairman of ASGT), Ishikawa (a board member of ASGT), Sukegawa (a board member of ASGT), and Fujita (the secretary general of AJC). Fukunaga and Bi are the main members of the ASGT. They examine the AEC and East Asia as excellent ASEAN experts. The AJC and ASGT have held many symposiums and joint meetings with ASEAN. Three board members (Shimizu, Ishikawa and Sukegawa) have edited and published many books, and were editors of three publications on the AEC (2009, 2013, 2016).

This paper will consider the AEC and East Asian economic integration, including the RCEP, in the structural changes of the world economy. This is also an introductory paper for this special issue and the latest paper on the deepening of the AEC and the signing of the RCEP. The author has analyzed ASEAN and East Asian economic integration within the structural changes of the world economy on a specific and long-term basis.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the development of intra-ASEAN economic cooperation and the proposal of the AEC. Section 3 discusses ASEAN and East Asia within the context of changes after the global financial crisis. Section 4 discusses ASEAN and East Asia and rising protectionism and US-China trade friction. Section 5 examines the deepening of the AEC and the signing of the RCEP in the rising protectionism and the outbreak of the COVID-19. Section 6 presents the conclusion.

2 The Development of Intra-ASEAN Economic Cooperation and the Proposal of the AEC

2.1 Intra-ASEAN Economic Cooperation in the World Economy 1976–1990

In East Asia, ASEAN has been the sole source of regional cooperation and integration. Founded in 1967, ASEAN began intra-ASEAN economic cooperation at the 1st ASEAN Summit in 1976. This economic cooperation was carried out according to “ASEAN’s Strategy for Collective Import Substituting Industrialization for Heavy and Chemical Industries (ASEAN’s strategy for CISI).” However, the strategy suffered a setback due to failures resulting from conflicts in economic interests among the ASEAN countriesFootnote1.

At the 3rd ASEAN Summit in 1987, “ASEAN’s strategy for CISI” was replaced with a new strategy, “ASEAN’s strategy for Collective FDI-dependent and Export-oriented Industrialization (ASEAN’s strategy for CFEI).” This was because the base of intra-ASEAN economic cooperation had changed due to structural changes in the world economy. A decisive turning point came in the form of the “Plaza Accord” in September 1985. After the “Plaza Accord,” the international division of labor by multinational companies (MNCs) began to take place at a faster pace due to the high yen and cheap dollar. Foreign direct investment (FDI) from Japan in Asian newly industrializing economies (NIES) and ASEAN countries increased rapidly. In addition, ASEAN countries made a drastic change to their foreign capital policies in the mid-1980s, from FDI-regulated policies to FDI-attractive policies. These fundamental changes in the conditions of intra-ASEAN economic cooperation forced the switch from the previous “ASEAN’s strategy for CISI” to the new strategy. At the heart of this new strategy was the Brand-to-Brand (BBC) Complementation Scheme, which was an auto parts complementation schemeFootnote2.

2.2 Intra-ASEAN Economic Cooperation in the Changes in 1990s

ASEAN’s strategy for CFEI reached a new phase, along with historical structural changes surrounding ASEAN starting in 1991 due to changes in the cold war framework and rapid economic growth in East Asia. These changes promoted the deepening and widening of intra-ASEAN cooperation.

The ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and ASEAN Industrial Cooperation (AICO) were promoted as extensions of ASEAN’s strategy for CFEI. The AFTA was agreed upon by ASEAN leaders at the 4th ASEAN Summit in January 1992. ASEAN leaders then signed the “Framework Agreement on Enhancing Economic Cooperation”Footnote3 and the “ASEAN Agreement on the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) Scheme for the AFTA.”Footnote4 The AFTA had been promoted to realize a FTA (its tariffs were under 5%), originally by 2008Footnote5. The AICO, a new industrial cooperation scheme developed the BBC scheme, which was finalized and signed on April 27, 1996Footnote6 , and promoted.

The change in the cold war structure was the decisive factor for globalization in East Asia. This change led to the expansion of the market and economic space for ASEAN. Furthermore, Indochina countries joined ASEAN: Vietnam joined in 1995, Myanmar and Laos in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999. Consequently, ASEAN now extends throughout Southeast Asia.

However, ASEAN countries were hurt by the Asian economic crisis. This crisis began in Thailand with its currency crisis in 1997, which immediately had a great impact on other ASEAN countries. ASEAN countries faced serious problems, including negative economic growth, a decline in demand, and stagnant FDI.

With the 1997 Asian economic crisis as a turning point, intra-ASEAN economic cooperation entered a new phase because the structures of the world economy and the East Asian economy surrounding ASEAN had changed significantly. The first change was China’s rapid growth and its expanding influence. The second change was stagnation in the liberalization of trade by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the evolution of FTAs. The third change was increased interdependency throughout East Asia, including China. The structural change after the Asian economic crisis required a deepening of intra-ASEAN economic cooperation for ASEAN.

2.3 The Proposal of the AEC in 2003 and the AEC Blueprint of 2007

The 9th ASEAN Summit meeting in Bali, Indonesia, in October 2003, was a significant turning point for ASEAN. The “Declaration of ASEAN Concord II” at the 9th Summit meeting presented a plan to realize an ASEAN community, which consisted of the ASEAN Security Community (ASC), the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), and the ASEAN Social and Cultural Community (ASCC)Footnote7.

The AEC was regarded as the core of the three communities. The “Declaration of ASEAN Concord II” stated that “AEC is the realization of the end-goal of economic integration as outlined in ASEAN Vision 2020, to create a stable, prosperous, and highly competitive ASEAN economic region in which there is a free flow of goods, services, investment, and a freer flow of capital, equitable economic development, and reduced poverty and socio-economic disparities by the year 2020.”Footnote8 The goal was to realize a single market or a common market that included factor movement. For that reason, this idea had the potential to strengthen ASEAN economic integration.

The attraction of FDI remained a very important issue for the AEC, that is, the AEC’s concept had an aspect of ASEAN’s strategy for CFEI. The former secretary-general of the ASEAN Secretariat, Rodolfo C. Severino, stated that ASEAN leaders were deeply concerned over the weakened ability of ASEAN countries to attract foreign direct investment and that ASEAN leaders were convinced that the only way for Southeast Asia to meet these challenges was to deepen the integration of the ASEAN economy in a way that was credible to investorsFootnote9. For ASEAN member countries, FDI and exports remained the key to development. However, China and India emerged as major competitors. Under these circumstances, ASEAN heads sought the deepening of intra-ASEAN economic cooperation to attract additional FDI.

At the 13th ASEAN Summit in November 2007, ASEAN leaders adopted the “ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint (AEC Blueprint).”Footnote10 The AEC Blueprint was a roadmap for each ASEAN member country’s compliance within the AEC by 2015Footnote11. The AEC Blueprint rested on four pillars: “A. Single Market and Production Base,” “B. Competitive Economic Region,” “C. Equitable Economic Development,” and “D. Integration into the Global Economy.” The central pillar, “A. Highly Integrated and Cohesive Economy,” included “A1. Free flow of goods,” “A2. Free flow of services,” “A3. Free flow of investment,” “A4. Freer flow of capital,” and “A5. Free flow of skilled labor.”Footnote12 ASEAN’s goal was to realize the AEC by 2015 according to the AEC Blueprint.

2.4 The Results of Intra-ASEAN Economic Cooperation

ASEAN has achieved steady results thus far through intra-ASEAN economic cooperation. The AFTA had been promoted and tariffs in ASEAN had been eliminated gradually through the AFTA and the CEPT. In January 2003, the AFTA (its tariff was under 5%) was established by the ASEAN 6 countries (Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand). Eventually, in January 2010, the AFTA (its tariff was almost 0%) was fully established among the ASEAN 6. Then, tariffs on all items (99.65%) were eliminated among the ASEAN 6. Simultaneously, the tariffs on almost all items (98.96%) were reduced to 0%–5% in CLMV (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam). The AFTA utilization rates by individual states increased. For example, 61.3% of exports from Thailand to Indonesia in 2010 used AFTAFootnote13. The ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA), which developed the CEPT, entered into force in May 2010.

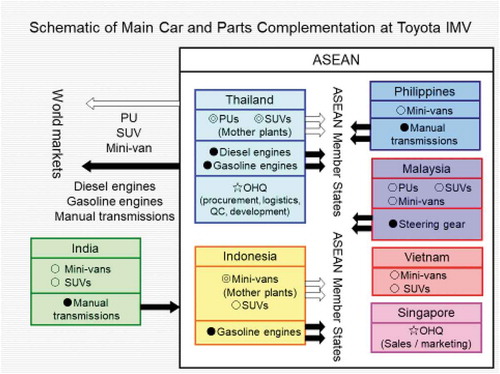

ASEAN integration policies supported production networks in industry. The automotive industry was a typical example. Toyota Motor Corp., which held a large share of the ASEAN automotive market, had been complementing main auto parts in the ASEAN region under the BBC, the AICO and the AFTA. As an extension of these complementation, Toyota began to produce a strategic world car: the Innovative International Multipurpose Vehicle (IMV) in Thailand for the first time in the world in August 2004. The world’s largest production base for this IMV was in ASEAN, specifically, Thailand. The AFTA supported the production and complementation of IMV and its main parts (). This was a good match between the ASEAN integration policies and the corporate production networkFootnote14.

2.5 ASEAN and East Asian Regional Cooperation

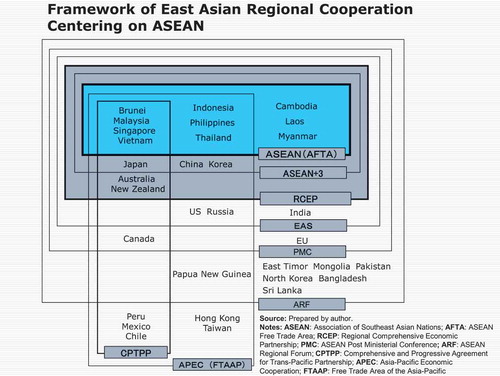

ASEAN led East Asian regional cooperation, including ASEAN+3, East Asia Summit (EAS), and ASEAN+1 FTAs. With ASEAN as a crucial axis, East Asian regional cooperation was implemented in a multi-layered fashion (). Each regional cooperation has been formed with its own purpose and members in response to political and economic changes in East Asia. Therefore, regional cooperation in East Asia has been formed in multiple layered. And ASEAN was at the center of this East Asian regional cooperation.

Figure 2. Framework of East Asian Regional Cooperation Centering on ASEAN

Originally, ASEAN had sought wider economic cooperation over an extensive region, including East Asia, because of its key mission of intra-ASEAN economic cooperation. The acquisition of foreign capital, including FDI and financial assistance, and securing export markets were important factors affecting intra-ASEAN economic cooperation. It was in line with ASEAN’s Strategy for CFEI. Therefore, it remained inevitable for ASEAN to secure foreign capital and export markets and to establish a wider framework including East Asian regional cooperation and the FTAFootnote15.

East Asian regional cooperation developed in the wake of the Asian financial crisis. ASEAN+3 (APT: ASEAN Plus Japan, China, and Korea) Summit meetings were held in December 1997 during the Asian economic crisis. In May 2000, the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) was agreed upon at the APT Finance Ministers Meeting in Chiang Mai. The CMI was an extension of the ASEAN Swap Arrangements (ASP) signed in 1977 and a new development in monetary and financial cooperation, not only for ASEAN, but also for the East Asian regionFootnote16.

In a series of ASEAN summits in December 2005, the first EAS was held in December 14. The number of participating countries in the 1st EAS were 16, including 10 ASEAN countries and Japan, China, South Korea, India, Australia, and New Zealand. The EAS has since been convened annually.

ASEAN+1 FTAs have been rapidly explored since 2000. ASEAN has been the hub of five FTAs. The first ASEAN+1 FTA was the ACFTA. ASEAN and China signed the “Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Co-operation between ASEAN and China”Footnote17 in November 2002. ASEAN established five ASEAN+1 FTAs: the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA), the ASEAN–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (AJCEP), the ASEAN–Korea Free Trade Agreement (AKFTA), the ASEAN–India Free Trade Area (AIFTA), and the ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Area (AANZFTA).

However, the wider FTA for East Asia as a whole was not established and the Japan–China–Korea FTA was also not established. With regard to the wider East Asian FTA, Japan proposed the Comprehensive Economic Partnership in East Asia (CEPEA) including 16 members of the EAS, and China proposed the East Asian regional Free Trade Area (EAFTA) including 13 members of APT. However, these agreements were not concluded.

3 ASEAN and East Asia in the Changes after the Global Financial Crisis: The AEC, the RCEP and the TPP

3.1 The Structural Changes after the Global Financial Crisis and the TPP and the RCEP

The 2008 global financial crisis required a change in ASEAN and East Asian economic cooperation. In the structural changes following the global financial crisis of 2008, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) began to have a greater significance and had an enormous impact on the realization of East Asian economic integrationFootnote18.

The world financial crisis caused great damage to ASEAN and East Asia. However, ASEAN and East Asia recovered more rapidly than other areas, including the US and Europe, in the post-global financial crisis era. ASEAN and East Asia became the main production base and the main market of intermediate goods in the world economy, and became the main growing market for final goods in the world economy through its fast-growing income and its large population. ASEAN and East Asia had come to seek not only export markets outside the region, but also internal marketsFootnote19.

Meanwhile, in the structural changes in the world economy, the US changed its growth policy and joined the TPP with the aim of expanding its exports to East Asia. The US required not only internal demand but also external demand because US demand, which is dependent on financial growth and overconsumption, was decreasing. Then, the important export market for the US became East Asia, which was recovering from the financial crisis and growing rapidly. US President Obama set forth a plan to double exports in January 2010 and declared that the US would participate in the TPP covering East Asia and the Asia Pacific region.

The TPP, originally the P4, including Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore, came into effect in 2006. However, once the US, Australia, Peru, and Vietnam joined the group, the TPP became very significant in the world economy. TPP negotiations began in eight countries in March 2010, and Malaysia joined in October that same year.

While the TPP was establishing itself, Japan and China made a joint proposal at the ASEAN+6 economic ministers meeting in August 2011 and agreed to advance an FTA for the entire East Asian region between the Japan-led CEPEA and the China-led EAFTA. This lay the foundation for ASEAN’s proposal of the RCEP.

At the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in November 2011, Japan also announced that it would begin discussions with the countries involved in the TPP negotiations. This increased the impact of the TPP. Canada and Mexico also joined the TPP negotiations.

3.2 ASEAN’s Proposal of the RCEP

Under these circumstances, at the 19th ASEAN summit in November 2011, ASEAN proposed a new ASEAN-led East Asian mega-FTA: the RCEP, along with the extension of CEPEA and EAFTA, and the ASEAN+1 FTAs, and presented the “ASEAN Framework for Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).”Footnote20

This was because ASEAN wanted to maintain its centrality in East Asian regional cooperation and economic integration. ASEAN had to pursue “the second best policy” to propose and lead the RCEP in the TPP negotiations on the changes after the global financial crisisFootnote21. For ASEAN, the traditional East Asian regional cooperation framework was the best. So far, there have been five ASEAN+1 FTAs. ASEAN has become the hub of ASEAN+1 FTAs; there were no FTAs between Japan, China, and Korea. However, ASEAN had to propose the RCEP to maintain ASEAN centrality in East Asia, when Japan and China compromised and proposed an East Asian Mega-FTA under the pressure of the TPP.

On August 30 2012, the first “ASEAN Economic Ministers Plus ASEAN FTA Partners Consultations” was held, and ministers agreed to recommend to government leaders the “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the RCEP.”Footnote22 On November 20 2012, the leaders of ASEAN and ASEAN’s FTA partners announced the launch of negotiations for the RCEP and endorsed the “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the RCEP.”Footnote23

According to the “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the RCEP,” the objective of launching RCEP negotiations was to achieve a modern, comprehensive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement among the ASEAN member states and ASEAN’s FTA Partners. The RCEP would cover trade in goods, trade in services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement and other issues, and negotiations for the RCEP would recognize “ASEAN Centrality” in the emerging regional economic architectureFootnote24.

3.3 The Impact of TPP negotiations

The progress of the TPP negotiations supported the other stalled FTAs’ negotiations. On March 15 2013, Japan formally announced its participation in TPP negotiations. This had a further impact on East Asian economic integration. The stalled FTA negotiations were quickly revived. On March 25, Japan and the European Union (EU) declared the commencement of the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) negotiations. On March 26, Japan, China, and South Korea held their first discussions toward a Japan–China–Korea FTA. In addition, the first RCEP negotiation round took place in May 2013. Japan officially participated in TPP negotiations’ 18th round in July 2013.

The TPP agreement was finally concluded on October 5 2015, at the TPP ministerial meeting in Atlanta, in the US. Furthermore, on February 4 2016, the TPP agreement was signed by 12 participating countries in Auckland, New Zealand. The text of the TPP includes 30 chaptersFootnote25. The next task was to make the TPP effective.

The TPP would be a mega FTA that represents approximately 40% of the world’s GDP. It would involve 12 Asia-Pacific countries, including Japan, and the US. The East Asian participants were Japan and four ASEAN countries, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei. The TPP’s distinguishing features were its high level of trade liberalization and its inclusion of new trade rules.

The TPP was expected to have a great impact on the East Asian economy and support East Asian economic integration, including the AEC and the RCEP. When the TPP negotiations advanced, East Asian economic integration also progressed. The TPP was expected to promote the negotiation of the RCEP and influence some of the rule making of the AECFootnote26.

3.4 Establishment of the AEC and the New AEC Goal “AEC 2025”

3.4.1 Establishment of the AEC at the End of 2015

ASEAN finally established the AEC at the end of 2015 in response to the changes in the world economy. This was a great milestone for ASEAN economic integration. ASEAN remained the most developed and advanced economic integration in East Asia.

ASEAN held the 27th ASEAN Summit Meeting and related Summits in November 2015. ASEAN declared the establishment of the AEC at the end of 2015 in the “Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the establishment of the ASEAN Community”Footnote27 on November 22. ASEAN adopted three important documents on AEC: the “ASEAN Economic Community 2015: Progress and Key Achievements,”Footnote28 the “ASEAN Integration Report 2015,”Footnote29 and the “ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together”Footnote30 at the 27th ASEAN Summit on November 21 2015.

The AEC had a great result on the elimination of tariffs in the pillar “A. Single Market and Production Base” in the “AEC Blueprint 2015.” Furthermore, ASEAN also had an unexpected great result in the pillar “D. Integration into the Global Economy.”

ASEAN achieved the elimination of almost all tariffs in all ASEAN states through the AFTA in January 2015. This was the first great result of the AEC. The elimination of tariffs was the most important and central goal presented in “A1. Free flow of goods” of “A. Single Market and Production Base” in “AEC Blueprint 2015.” On January 1 2015, CLMV eliminated most all tariffs, except for the 7% tariff items, which were postponed until January 2018. In January 2010, ASEAN 6 had already achieved the elimination of almost all tariffs. On January 1 2015, ASEAN 6 eliminated their intra-regional tariffs in 99.2% of the tariff lines. For CLMV, the figure stood at 90.86%. The ASEAN average was 95.99%Footnote31. This was the highest level in all East Asian FTAsFootnote32.

As for the goal “A1. Free flow of goods, ASEAN also improved the rules of origin (ROO), introduced a self-certification scheme, and promoted customs integration, and the ASEAN Single Window (ASW). ASEAN also tried to eliminate non-tariff barriers, but this was very difficult to achieve and the goal was postponed to 2025. ASEAN gradually promoted “A2. Free flow of services,” “A3. Free flow of investment,” “A4. Freer flow of capital” and “A5. Free flow of skilled labor”.

The goal in pillar “B. Competitive Economic Region” includes competition policy, consumer protection, intellectual property rights (IPR), infrastructure development, etc. The goal in pillar “C. Equitable Economic Development” includes SME development and the Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI). As for these goals, ASEAN has worked on many projects on transportation, energy, intellectual rights, and narrowing the gaps in ASEAN; however, the achievement of these goals was rescheduled to beyond 2015.

The final goal in pillar “D. Integration into the global economy” was achieved earlier than planned. This was because the ASEAN+1 FTAs had been completed and ASEAN had proposed and led the RCEP. This was another significant result for the AEC in 2015.

3.4.2 The New AEC Goal “AEC 2025”

At the 27th ASEAN Summit on November 21 2015, ASEAN adopted the new AEC goal “AEC 2025” for 2025. ASEAN sought to deepen the AEC beyond its establishment in 2015 in line with the “AEC 2025” for 2025. “AEC Blueprint 2025” included in “ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together” presented the goals of “AEC 2025” and its five pillars.

“AEC 2025” stated the firm goals for 2025, beyond the establishment of the AEC in 2015. The basic structure of “AEC 2025” was inherited from “AEC 2015. Compared to “AEC 2015,” some new areas were added to “AEC 2025” and a new pillar, “C. Enhanced Connectivity and Sectoral Cooperation”Footnote33 ().

Table 1. AEC 2015 (2007) and AEC 2025 (2015)

The five pillars of “AEC 2025” were “A. A Highly Integrated and Cohesive,” “B. A Competitive, Innovative and Dynamic ASEAN,” “C. Enhanced Connectivity and Sectoral Cooperation,” “D. A Resilient, Inclusive, People-Oriented and People-Centered ASEAN,” and “E. A Global ASEAN.”

The central pillar “A. A Highly Integrated and Cohesive Economy” included “A1 Trade in Goods,” “A2 Trade in Services,” “A3 Investment Environment,” “A4 Financial Integration, Financial Inclusion, and Financial Stability,” “A5 Facilitating Movement of Skilled Labor and Business Visitors,” and “A6 Enhancing Participation in Global Value Chains.”

4 ASEAN and East Asia in the Rising Protectionism and US-China Trade Friction

4.1 The US Withdrawal from the TPP and Japan’s Proposal of the CPTPP

US president Trump’s actions on protectionism and trade friction have damaged the world economy, including the ASEAN and East Asian economies. Trump was elected in the US presidential election on November 8 2016, and took office as president of the United States on January 20 2017. He subsequently changed the trading landscape significantly. On January 23 2017, Trump signed an executive order withdrawing the US from the TPP. Trump also reversed the US trade policy that had driven the world’s free trade system in order to negotiate bilateral FTAs instead of multilateral FTAs.

The US withdrawal from the TPP also greatly affected the economic integration of ASEAN and East Asia. Before the US withdrawal from the TPP, the TPP supported the development of the AEC and the RCEP negotiations. However, it became impossible for the TPP to accelerate economic integration in East AsiaFootnote34.

In the difficult situation following the US withdrawal from the TPP and rising protectionism, Japan proposed the TPP11, excluding the US. The TPP11 negotiations were launched in May 2017, and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) was agreed on at the Ministerial Meeting in November 2017. The CPTPP was signed by 11 countries on March 8Footnote35. Six countries completed their domestic procedures by November, and the CPTPP finally entered into force on December 30. The CPTPP was a mega-FTA representing a population of 500 million people, about 13% of world GDP, and 15% of total trade, although CPTPP was smaller than the original TPP.

The CPTPP was expected to promote trade liberalization and rule making in the Asia-Pacific region. It will be a template for future Mega-FTAs. Furthermore, another Japan-led Mega-FTA, the Japan–EU EPA came into force on February 1 2019.

4.2 The Trade Friction between the US and China

Along with the US withdrawing from the TPP, Trump caused significant trade friction by imposing high tariffs on imports from countries around the world. In particular, trade friction with China from 2018 onward has had a major negative impact on the world economy. The rising protectionism, including the US–China trade frictions, caused great damage to ASEAN and East Asian economies, because ASEAN and East Asia had developed rapidly in the freer trade and investment environment in the world economy.

On March 23 2018, the US imposed additional tariffs of 25% and 10% on steel and aluminum, respectively, based on Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. In retaliation to this measure, China imposed additional tariffs on fruits and pork from the US on April 2Footnote36.

Furthermore, as measures against China were implemented, the US imposed an additional 25% tariffs on imports of 34 USD billion from China on July 6, under Article 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. On the other hand, China imposed 25% tariffs on imports of 34 USD billion from the US as a retaliatory measure. In the second round, on August 23 2018, the US put additional 25% tariffs on imports of 16 USD billion from China. In response to this measure, China imposed an additional 25% tariffs on imports of 16 USD billion from the US. In the third round, on September 24 2018, the US put an additional 10% tariffs on imports of 200 USD billion from China and China imposed an additional 5%–10% tariffs on 60 USD billion of imports from the US.

In 2019, the US–China trade friction escalated further. On May 10, US raised an additional 10% tariffs on imports of 200 USD billion from China to 25%. In opposition, China raised an additional 5%–10% tariffs on 60 USD billion of imports from the US. In the fourth round, on September 1 2019, the US launched part of the fourth measures for China and put an additional 15% tariffs on imports of 120 USD billion from China and China imposed an additional 5%–10% tariffs on 75 USD billion of imports from the United States.

4.3 The AEC and the RCEP in the Rising Protectionism

Amidst the rising protectionism, ASEAN developed the AEC steadily. ASEAN adopted the AEC “2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan (CSAP)” and ASEAN finally completed tariff elimination within the AEC and the AFTA.

On February 6 2017, the “2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan (CSAP)”Footnote37 was endorsed by the ASEAN Economic Ministers and the ASEAN Economic Community Council Ministers. The AEC 2025 CSAP was a concrete action plan based on the AEC 2025 Blueprint. On August 14 2018, ASEAN updated the AEC 2025 CSAPFootnote38.

On January 1 2018, ASEAN finally completed tariff elimination through the AFTA and the ATIGA. The tariffs on 7% of the items in the CLMV were eliminated. The elimination of these tariffs had been postponed for three years on January 1 2015. Tariffs on more than 600 items in CLMV were eliminated.

The AFTA has been a highest-level FTA representing East Asia. For example, in September 2019, the liberalization rate of AFTA reached 99.3% for ASEAN 6, 97.7% for CLMV, and 98.6% for ASEAN as a whole. This is a higher rate than the 98% level of the CPTPP. Furthermore, the AFTA has actually been used by ASEAN states. For examples, the AFTA utilization rate in Thailand’s exports reached about 67.1% and 69.4% in its exports to Indonesia and the Philippines, and 61.6% in its exports to Vietnam in 2019Footnote39.

But there were some problems for trade liberalization and ASEAN economic integration. For example, there was the problem of Vietnam’s non-tariff measures (NTMs): “Decree 116”. On January 1 2018, Vietnam’s 30% tariffs on automobiles and automobile parts were eliminated. However, Vietnam adopted a very strict import ban policy through “Decree 116” on January 1 2018. Despite the elimination of tariffs by AFTA, automobile imports were stopped by “Decree 116.” Imports of automobiles from Thailand resumed in March 2018 and imports from Indonesia resumed in April, but sales of imported cars from January to June 2018 had decreased by 49.5%Footnote40.

The “Decree 116” measures were the NTMs against the deepening of ASEAN economic integration. ASEAN had to deal with the problems of economic integration in rising protectionism. Thailand and Indonesia submitted these issues to the Coordinating Committee of the ATIGA. Two companies filed complaints against Vietnam’s measures through ASEAN Solutions for Investments, Services, and Trade (ASSIST). The ASEAN Secretariat registered these cases in the Matrix of Actual Cases on NTMsFootnote41. Subsequently, in February 2020, “Decree 116” was amended and its measures were greatly relaxed.

By 2018, the RCEP had not concluded negotiations between 16 countries. By 2019, the 16 countries had still not concluded the RCEP negotiations due to objections by India. The “Joint Leaders’ Statement on RCEP” at the third RCEP Summit in November 2019 said, “We noted 15 RCEP Participating Countries have concluded text-based negotiations for all 20 chapters and essentially all their market access issues and tasked legal scrubbing by them to commence for signing in 2020,” and said “India has significant outstanding issues, which remain unresolved. All RCEP participating countries will work together to resolve these outstanding issues in a mutually satisfactory way.”Footnote42 However, an Indian official said India could not join the RCEP under its current terms, and India did not participate in the subsequent negotiation meetings.

5. The Deepening of the AEC and the Signing of the RCEP in the Rising Protectionism and the COVID-19 Outbreak

5.1 The Rising Protectionism and the COVID-19 Outbreak

On January 15 2020, the US and China signed the “Economic and Trade Agreement of the Government of the US and the Government of China.” In this first-stage agreement, China promised to increase imports of agricultural and industrial products from the US by 200 USD billion. On the other hand, the US agreed that it would reduce an additional 15% tariffs on imports of 120 USD billion from China to 7.5%Footnote43. The agreement came into effect on February 14, and tariffs were reduced.

However, the additional 25% tariffs on the 1st −3rd rounds were maintained. The issues of industrial subsidies related to “Made in China 2025” remained. Between the US and China, there has been a battle for hegemony over the high-tech industry. The US also tightened regulations on Huawei. China will maintain “Made in China 2025,” and it will be difficult to resolve these issues.

In this difficult situation, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world. It inflicted great damage on ASEAN and East Asia. In ASEAN, infections were particularly high in Indonesia and the Philippines. All ASEAN and East Asian countries were damaged by supply and demand shocks. In 2020, ASEAN’s economy was projected to contract by 3.8% in 2020, the first economic contraction in 22 yearsFootnote44. In this environment, ASEAN had to deal with the outbreak in COVID-19 in various stages on recovery and keep production networks functioningFootnote45. During the break of COVID-19, the US–China conflicts expanded further.

5.2 ASEAN’s Response against the COVID-19 and the Deepening of the AEC

ASEAN responded to the outbreak of the COVID-19. ASEAN developed the AEC steadily and secured the ASEAN centrality in East Asian economic integration in the growing global protectionism and the COVID-19 pandemic.

ASEAN and East Asian regional cooperation took regional measures against the COVID-19. ASEAN and East Asian regional cooperation and integration will be even more important in and after the COVID-19 crisis. ASEAN agreed to the establishment of the “COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund” at a special ministerial meeting on April 9 2020. On April 14, the “Special ASEAN Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)” and the “Special ASEAN+3 Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)” were held. ASEAN demonstrated ASEAN’s highest level of commitment to a collective response to the outbreak of COVID-19 at the summitFootnote46. The leaders of ASEAN+3 affirmed ASEAN’s commitment to enhance national and regional capacities to prepare for and respond to pandemics, and to ensure adequate financing the establishment of the “COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund.”Footnote47 At the summit, Japan, China, and Korea announced many support initiatives for ASEAN on the break of the COVID-19. Japan announced to support the establishment of the “COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund,” and proposed the establishment of an “ASEAN Center for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases.”

At the 37th ASEAN Summit on November 12 2020, ASEAN stated that ASEAN welcomed the commitments and pledges of ASEAN member states, dialogue partners, and other external partners in contributing to the “COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund.” ASEAN also stated that ASEAN had launched the “ASEAN Regional Reserve of Medical Supplies (RRMS) for Public Health Emergencies,” and announced the establishment of the “ASEAN Center for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases (ACPHEED).”Footnote48

Furthermore, ASEAN adopted the “ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework (ACRF)”Footnote49 and “Implementation Plan of ASEAN Recovery Framework.”Footnote50 The “ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework” serves as a consolidated exit strategy from the COVID-19 crisis. It articulated ASEAN responses through the different stages of recovery by focusing on key sectors and segments of society that are most affected by the pandemic, setting broad strategies, and identifying measures for recovery in line with sectoral and regional prioritiesFootnote51.

ASEAN developed the AEC steadily for 2025 in the growing protectionism and the outbreak of the COVID-19. The AEC will be inevitable for ASEAN in the rising protectionism and in and after the outbreak of the COVID-19. The 52nd ASEAN Economic Ministers Meeting (AEM) in August 2020 and the 37th ASEAN Summit in November 2020 confirmed AEC’s progress in these difficult times. Regarding the “Trade in Goods” pillar, ASEAN implemented the ASEAN-wide Self-Certification (AWSC) policy in September 20 2020, which would further reduce trade transaction costs and simplify certification procedures. The ASEAN Customs Transit System (ACTS) was launched on November 2 2020, to facilitate the cross-border movement of goods in transit. ASEAN signed a new mutual recognition agreement (MRA): the “MRA on Type Approval for Automotive Products.” ASEAN has also completed the signing of the “ASEAN Trade in Services Agreement (ATISA)” to develop the current AFAS and the “Fourth Protocol to Amend the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA).”Footnote52

The AEC is the most advanced economic integration in East Asia. The AEC completed the elimination of tariffs in 2018 through the AFTA. The AFTA is the highest-level FTA representing East Asia. There are still many challenges including the elimination of the NTMs, the trade facilitations and other issues for the next goal: AEC2025. ASEAN will further promote the free flow of goods, services, investment, capital and skilled labor, and many issues for AEC 2025. Furthermore, ASEAN will improve the AEC in response to the new changes due to the COVID-19.

The structural change in terms of the digitalization of the economy precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic will continue. The AEC has been supporting production networks in manufacturing in the region. This support will be inevitable in and after COVID-19. In addition, it will be more important to support digitalization including electronic commerce (EC), as well and production networks.

ASEAN signed the “ASEAN Agreement on Electronic Commerce” in Hanoi on January 22 2019. This agreement is coming into effect. Brunei ratified the agreement on September 21 2020. This was the eighth ratification of members. At the 37th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN stated that ASEAN looked forward to the adoption of the ASEAN Digital Masterplan 2025 to achieve inclusive, resilient, and sustainable economic growth in the region, especially during and in the post-pandemic eraFootnote53.

5.3 The Signing of the RCEP and ASEAN

5.3.1 The Signing of the RCEP in November in 2020

In November 2020, two major changes took place that would have a great impact on ASEAN and East Asia in the midst of growing protectionism and the global spread of COVID-19. First, Joe Biden won the 2020 US presidential election held on November 6. Biden takes office as president of the US in January 2021 and will change Trump’s current trade policies.

Furthermore, and very importantly, the RCEP agreement was finally signed by the leaders of 15 East Asian countries at the 4th RCEP Summit on November 15 2020. This was a great result for ASEAN and East Asian economic integration.

The “Joint Leader’s Statement on the RCEP” stated “We were pleased to witness the signing of the RCEP Agreement, which comes at a time when the world is confronted with the unprecedented challenge brought about by the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) global pandemic … We believe that the RCEP, being the world’s largest free trade arrangement, represents an important step forward toward an ideal framework of global trade and investment rules.”Footnote54 It also stated, “We also note that the RCEP Agreement is the most ambitious free trade agreement initiated by ASEAN, which contributes to enhancing ASEAN centrality in regional frameworks and strengthening ASEAN cooperation with regional partners,”Footnote55 about ASEAN’s role and the ASEAN centrality, and added “We are committed to ensuring that RCEP remains an open and inclusive agreement. Further, we would highly value India’s role in RCEP and reiterate that the RCEP remains open to India.”Footnote56

5.3.2 The Contents of the RCEP

The purpose of the RCEP is to be a modern, comprehensive, high-quality, and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement (EPA) for East Asian nations. An important feature of the RCEP is that of ASEAN’s centrality in East Asia. The RCEP’s goal is also to form a larger and advanced FTA beyond the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs.

The agreement has 20 chapters, covering a range of areas regarding trade liberalization and rules, including “Trade in Goods (Chapter 2),” “Trade in Services (Chapter 8),” “Investment (Chapter 10),” “Intellectual Property (Chapter 11),” “Electronic Commerce (Chapter 12),” “Competition (Chapter 13),” and “Economic and Technical Cooperation (Chapter 15)”Footnote57 ().

Table 2. The Chapters of the RCEP Agreement

The RCEP Agreement updated the coverage of the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs and contains provisions and many improved points beyond the existing ASEAN+1 FTAFootnote58. Furthermore, “Chapter 16: Government Procurement” is a new chapter not included in the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs.

In “Trade in Goods (Chapter 2),” many tariffs on items will be eliminated beyond the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs. Some tariffs of items will be removed immediately, although some tariffs will take a longer time to eliminate. Overall, tariffs are likely to be eliminated on 91% of all products. The unified rules of origin (ROO) (Chapter 3) will be important for members and corporations compared to the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs.

Many chapters, including “Trade in Services (Chapter 8),” “Investment (Chapter 10),” “Intellectual Property (Chapter 11),” “Electronic Commerce (Chapter 12),” and “Competition (Chapter 13)” contain advanced provisions beyond the existing ASEAN+1 FTA. For example, “Electronic Commerce (Chapter 12)” includes two new provisions: the free flow of data among members and the prohibition of data localization when compared to the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs.

This is the first step of the RCEP agreement. It will be essential for members to improve and develop the agreement, step by step, like the AFTA.

5.3.3 The Meanings of the Signing of the RCEP and the ASEAN Centrality in the East Asian Economic Integration

The RCEP will have great meaning to ASEAN and East Asia. The RCEP is the first mega-FTA for East Asia, which is at the center of world growth. There have been no mega-FTAs between East Asian nations, except for the AEC and ASEAN+1 FTAs. The members of the RCEP represent around 30% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), population, and trade, and the RCEP includes the first FTA for Japan, China, and South Korea.

The RCEP will have great benefits for ASEAN and East Asia. The first benefit of the RCEP is the encouragement of trade in goods and services and investment across East Asia, thus contributing to the continued economic development of the region as a whole. Second, it will contribute to the establishment of new and advanced rules. Third, it will facilitate the establishment of production networks or supply chains in ASEAN and East Asia. Fourth, the RCEP will help narrow the economic gaps between advanced and developing countries within the region.

The signing of the RCEP is very significant for ASEAN, because it will contribute to the economic development of ASEAN going forward, and especially important, it secures the ASEAN centrality in East Asian economic integration. The RCEP is a mega-FTA proposed and promoted by ASEAN, not by Japan or China. ASEAN proposed it in November 2011, and led the negotiations. Originally, ASEAN proposed a new ASEAN-led East Asian mega-FTA: the RCEP and presented the “ASEAN Framework for Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)” in November 2011. The ASEAN chair of the year has chaired the RCEP Ministerial Meetings. The RCEP Trade Negotiating Committee (TNC), the main negotiating committee of the RCEP, has been chaired and led by Indonesia’s Iman Pambagyo, the Director-General for International Trade Negotiation, Ministry of Trade of Indonesia. ASEAN has been the most important key player in the RCEP.

It will be more important for ASEAN to maintain the initiative in the RCEP in the future. As stated above, ASEAN must maintain the initiative in East Asian regional cooperation and economic integration due to the character of the original intra-ASEAN economic cooperation. That is, ASEAN must secure foreign capital and export markets, establish a wider framework, and maintain the initiative in its wider framework.

The RCEP will also be very significant for Japan because it accounts for half of Japan’s trade value. Furthermore, the RCEP is Japan’s third mega-FTA following the CPTPP and the Japan–EU EPA to counter protectionism. China was expected to join a mega-FTA during its conflict with the US. At the same time, the inclusion of China in the RCEP framework will be important for RCEP members for future trade and rules within the scheme. Unfortunately, India declined to sign the agreement this time around, but the door remains open to India’s entry in the futureFootnote59. India’s return to the RCEP will be important for all members.

Finally, the signing of the RCEP is expected to trigger the gradual overcoming of the challenging global economic situation characterized by protectionism and the COVID-19 pandemic. The CPTPP and the Japan–EU EPA have already been enacted. This third mega-FTA will have a positive impact on protectionism. In addition, the signing of the RCEP will have a positive influence on the new US trade policy.

6 Conclusion

ASEAN has led economic integration within many structural changes in the world economy. ASEAN finally established the AEC at the end of 2015. The AEC is the most developed and advanced economic integration in East Asia, which is now the center of world growth. ASEAN is deepening the AEC for the next goal “AEC 2025” in the changing world economy. ASEAN also has led East Asian cooperation initiatives, including ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6, and ASEAN+1 FTAs. ASEAN proposed the RCEP and led the RCEP negotiations.

Currently, rising protectionism and the US–China trade friction has had a significantly negative impact on ASEAN and East Asia. Furthermore, the outbreak of COVID-19 has inflicted great damage to ASEAN and East Asia. ASEAN is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. ASEAN is deepening the AEC steadily amid growing protectionism and COVID-19 pandemic.

The RCEP agreement was finally signed at the 4th RCEP Summit on November 15 2020. The RCEP is the first East Asian mega-FTA. The RCEP has great meaning in ASEAN and East Asia. ASEAN has secured ASEAN centrality in East Asian economic integration. The signing of the RCEP is expected to trigger the gradual overcoming of the challenging global economic situation characterized by protectionism and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The AEC and the RCEP will become more important amidst rising protectionism, and during and in the post-pandemic era.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kazushi Shimizu

Dr. Kazushi Shimizu is a Professor at Kyushu University. He obtained his Ph.D. at the Graduate School of Economics, Hokkaido University. He is a specialist in ASEAN economic integration and East Asian economic integration. He is the chairman of the ASEAN Study Group in Tokyo (ASGT) in the ASEAN Japan Centre (AJC). His major publications include: Intra-ASEAN Economic Cooperation (Kyoto: Minerva Shobo, 1998), “East Asian Regional Economic Cooperation and FTA,” in East Asian Regionalism from a Legal Perspective, Nakamura, T. (ed.), Routledge, 2009, “The ASEAN Economic Community and Japan in the World Economy,” Asian Studies, Japan Association for Asian Studies (JAAS), Vol. 62, No. 3 (2016), and “ASEAN and East Asian Trade Order,” in Asian Economic Integration and Protectionism, Ishikawa, K., Shimizu, K. and Umada, K. eds. (Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2019). He is a co-editor of publications on the AEC, including the ASEAN Economic Community (Tokyo: JETRO, 2009), the ASEAN Economic Community and Japan (Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2013), the Establishment of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan (Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2016).

Notes

1. Refer to Shimizu, Ikinaikeizaikyoryoku no Keizaigaku, Chapter 1–3.

2. Refer to Shimizu, Ikinaikeizaikyoryoku no Keizaigaku, Chapter 4–5.

3. ASEAN, “The Framework Agreement on Enhancing Economic Cooperation.”

4. ASEAN, “The ASEAN Agreement on the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) Scheme for the AFTA.”

5. Refer to Sukegawa, “Buppinboueki no Jiyuka hemuketa ASEAN no Torikumi, Sukegawa,” about the AFTA.

6. ASEAN, “Basic Agreement on the ASEAN Industrial Cooperation Scheme.”

7. ASEAN, “Declaration of ASEAN Concord.”

8. Ibid.

9. Severino, Southeast Asia in Search of an ASEAN Community, 342–343.

10. ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint.

11. Refer to Ishikawa, “ASEAN Keizaikyudoutai no Sousetsu to Sonoigi,” and Ishikawa, “ASEAN Economic Community and Economic Integration in ASEAN.”

12. ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint.

13. Sukegawa, “Buppinboueki no Jiyuka Enkatsuka hemuketa ASEAN no Torikumi,” 49–51.

14. Shimizu, “East Asian Regional Economic Cooperation and FTA,” 11–12, Shimizu, Sekaikeizai to ASEAN, 8–9.

15. Shimizu, “East Asian Regional Economic Cooperation and FTA, ” 12–13 and Shimziu, “ASEAN to Higashiajia Keizaitougou,” 295–296.

16. Refer to Shimizu, “East Asian Regional Economic Cooperation and FTA,” 13–14.

17. ASEAN, “Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Co-operation Between ASEAN and the People’s Republic of China.”

18. Refer to Shimizu, “Sekaikeizai to ASEAN Keizaikyoudoutai.”

19 Ibid, 11–12.

20. ASEAN, “Framework for Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.”

21. Shimizu, “ASEAN to Higashiajia Keizaitougou,” 295–296.

22. ASEAN, “First ASEAN Economic Ministers Plus ASEAN FTA Partners Consultations August 30 2012, Siem Reap, Cambodia Joint Media Statement.”

23. ASEAN, “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.”

24. Ibid.

25. MFAT of NZ, “Text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.”

26. Refer to Shimizu, “ASEAN Keizaitougou no Shinka to Amerika TPP Ridatsu.”

27. ASEAN, “The Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the establishment of the ASEAN Community.”

28. ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community 2015: Progress and Key Achievements.

29. ASEAN, ASEAN Integration Report 2015.

30. ASEAN, ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together.

31. ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community: Progress and Key Achievements 2015.

32. ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community: Progress and Key Achievements 2015, ASEAN, “ASEAN Integration Report 2015,” Ishikawa, Shimizu and Sukegawa, eds., ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai no Sousetsu to Nihon, and Ishikawa, “ASEAN Economic Community and Economic Integration in ASEAN,” about the realization of the AEC.

33. Refer to Ishikawa, “ASEAN Keizaikoudoutai no Sousetsu to Sonoigi, Ishikawa,” Ishikawa, “ASEAN Economic Community and Economic Integration in ASEAN,” and Fukunaga, “ASEAN Keizaikyodotai 2025Vision,” about “AEC 2025.”

34. Refer to Shimizu, “ASEAN Keizaitougou no Shinka to Amerika TPP Ridatsu.”

35. MFAT of NZ, “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.”

36 Refer to Ohashi, China Shock no Keizaigaku, about the trade friction and conflicts between the US and China.

37. ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community 2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan.

38. ASEAN, Economic Community 2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan (updated).

39 Refer to Sukegawa (Citation2021), “ASEAN’s Initiatives for Free Trade in East Asia under AEC.”

40. FOURIN, Ajia-Jidousha-Geppou, August 2018, 44–45.

41. Interviews with Dr. H.E. Alladdin D Rillo, Deputy Secretary-General of ASEAN for the ASEAN Economic Community at the ASEAN Secretariat in September 2018 and the ASEAN Japan Center (AJC) in September 2019.

42. ASEAN, “Joint Leader’s Statement on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).”

43. USTR, “Economic and Trade Agreement on the government of the US and the government of China”

44. ASEAN, ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework.

45. Refer to Kimura, “Exit Strategies for ASEAN Member States: Keeping Production Networks Alive Despite the Impending Demand Shock.”

46. ASEAN, “Declaration of the Special ASEAN Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).”

47. ASEAN, “Joint Statement of the Special ASEAN Plus Three Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).”

48. ASEAN, “Chairman’s Statement of the 37th ASEAN Summit Hanoi, November 12 2020 Cohesive and Responsive”

49. ASEAN, ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework.

50. ASEAN, Implementation Plan of ASEAN Recovery Framework.

51 ASEAN, ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework.

52. ASEAN, “Chairman’s Statement of the 37th ASEAN Summit Hanoi, November 12 2020 Cohesive and Responsive.”

53. Ibid.

54. ASEAN, “Joint Leader’s Statement on the RCEP.”

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. ASEAN, “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.”

58. ASEAN, “Summary of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.”

59. ASEAN, “Ministers’ Declaration on India’s Participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)”

Bibliography

- ASEAN, ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.asean.org/storage/2015/12/ASEAN-2025-Forging-Ahead-Together-final.pdf.

- ASEAN, ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework. Accessed January 10, 2021a. https://asean.org/storage/FINAL-ACRF_adopted_37th-ASEAN-Summit_18122020.pdf.

- ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community 2015: Progress and Key Achievements. Accessed January 10, 2021b. https://www.asean.org/wpcontent/uploads/images/2015/November/media-summary-ABIS/AEC2015ProgressandKeyAchievements_04.11.2015.pdf.

- ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community 2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan. Accessed January 10, 2021c. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Consolidated-Strategic-Action-Plan-endorsed-060217rev.pdf.

- ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community 2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan (Updated). Accessed January 10, 2021d. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Updated-AEC-2025-CSAP-14-Aug-2018-final.pdf.

- ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint. Accessed January 10, 2021e. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/archive/5187-10.pdf.

- ASEAN. “ASEAN Framework for Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.” Accessed January 10, 2021f. https://asean.org/?static_post=asean-framework-for-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership.

- ASEAN, ASEAN Integration Report 2015. Accessed January 10, 2021g. https://asean.org/storage/2015/12/ASEAN-Integration-Report-2015.pdfhttps://asean.org/storage/2015/12/ASEAN-Integration-Report-2015.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Basic Agreement on the ASEAN Industrial Cooperation Scheme.” Accessed January 10, 2021h. https://asean.org/?static_post=basic-agreement-on-the-asean-industrial-cooperation-scheme.

- ASEAN. “Chairman’s Statement of the 37th ASEAN Summit Hanoi, 12 November 2020 Cohesive and Responsive.” Accessed January 10, 2021i. https://asean.org/storage/43-Chairmans-Statement-of-37th-ASEAN-Summit-FINAL.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Declaration of ASEAN Concord II.” https://asean.org/?static_post=declaration-of-asean-concord-ii-bali-concord-ii

- ASEAN. “Declaration of the Special ASEAN Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Accessed January 10, 2021j. https://asean.org/storage/2020/04/FINAL-Declaration-of-the-Special-ASEAN-Summit-on-COVID-19.pdf.

- ASEAN. “First ASEAN Economic Ministers Plus ASEAN FTA Partners Consultations 30 August 2012, Siem Reap, Cambodia Joint Media Statement.” Accessed January 10, 2020a.https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/asean/pdfs/asean_fta_jms_1208.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Co-operation between ASEAN and the People’s Republic of China.” Accessed January 10, 2021k. https://asean.org/?static_post=asean-china-free-trade-area–2

- ASEAN. “Framework Agreement on Enhancing Economic Cooperation.” Accessed January 10, 2021l. https://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/2012/Economic/AFTA/Common_Effective_Preferential_Tariff/Framework%20Agreements%20on%20Enhancing%20ASEAN%20Economic%20Cooperation%20.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.” Accessed January 10, 2021m. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/RCEP-Guiding-Principles-public-copy.pdf.

- ASEAN. Implementation Plan of ASEAN Recovery Framework. Accessed January 10, 2021n.https://asean.org/storage/2020/11/3-FINAL-Implementation-Plan-ACRF_adopted-37th-ASEAN-Summit_121120.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Joint Leader’s Statement on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).” Accessed January 10, 2021o. https://asean.org/storage/2019/11/FINAL-RCEP-Joint-Leaders-Statement-for-3rd-RCEP-Summit.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Joint Statement of the Special ASEAN Plus Three Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Accessed January 10, 2021p. https://asean.org/storage/2020/04/Final-Joint-Statement-of-the-Special-APT-Summit-on-COVID-19.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the Establishment of the ASEAN Community.” Accessed January 10, 2021q. https://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/2015/November/KL-Declaration/KL%20Declaration%20on%20Establishment%20of%20ASEAN%20Community%202015.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement” Accessed January 10, 2020b. https://rcepsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/All-Chapters.pdf.

- ASEAN. “Summary of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.” Accessed January 10, 2021r. https://asean.org/storage/2020/11/Summary-of-the-RCEP-Agreement.pdf.

- Chia, S. Y., and M. G. Plummer. ASEAN Economic Cooperation and Integration: Progress Challenges and Future Directions. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2015.

- FOURIN, Ajia-Jidousha-Geppou [Fourin Monthly Journal of Asian Automobile Industry], 142, August 2018.

- Fukunaga, Y. “ASEAN Keizaikyodotai 2025Vision” [ASEAN Economic Community 2025 Vision]. In ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai No Sosetsu to Nihon [Creation of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan], edited by K. Ishikawa, K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, 153–168. Tokyo:Bunshindo, 2016.

- Intal, P., Y. Fukunaga, F. Kimura, P. Han, P. Dee, D. Narjoko, and S. Oum. ASEAN Rising: ASEAN and AEC beyond 2015. Jakarta: ERIA, 2014.

- Ishikawa, K. “ASEAN Keizaikoudoutai No Sousetsu to Sonoigi” [Creation of ASEAN Economic Community and Its Significance].” In ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai No Sousetsu to Nihon, edited by K. Ishikawa, K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, 25–50. Tokyo: Bunshindo: Establishment of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan, 2016.

- Ishikawa, K. “ASEAN Economic Community and Economic Integration in ASEAN.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 10 (2021).

- Ishikawa, K., K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa. ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai. [ASEAN Economic Community]. Tokyo: JETRO, 2009. eds.

- Ishikawa, K., K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, eds. ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai to Nihon [ASEAN Economic Community and Japan. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2013.

- Ishikawa, K., K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, eds. ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai No Sosetsu to Nihon. Tokyo: Bunshindo: The establishment of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan, 2016.

- Ishikawa, K., K. Umada, and T. Takahashi, eds. Mega FTA Jidai No Tsushosenryaku: Gnejo to Kadai. Bunshindo: [Trade Policy in the age of Mega FTA]. Tokyo, 2016.

- Kimura, F., ed. Korekarano Higashiajia: Hoshyu Shyugi No Taito to Mega FTAs [East Asia in the Future: The Rise of Protectionism and Mega FTAs]. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2020.

- Kimura, F., “Exit Strategies for ASEAN Member States: Keeping Production Networks Alive despite the Impending Demand Shock,” ERIA Policy Brief, No. 2020–2023. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.eria.org/uploads/media/policy-brief/Exit-Strategies-For-AMS-Keeping-Production-Networks-Alive-Despite-The-Impending-Demand-Shock.pdf.

- Ministry of [ASEAN Economic Community and Japan]Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan (METI of Japan), “Ministers’ Declaration on India’s Participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP),” Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2020/11/20201115001/20201115001-3.pdf.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of New Zealand (MFAT of NZ), “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership,” Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/CPTPP/CPTPP-Text-English.pdf.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of New Zealand (MFAT of NZ), “Text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership,” Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/about-us/who-we-are/treaties/trans-pacific-partnership-agreement-tpp/text-of-the-trans-pacific-partnership.

- Ohashi, H. Chyaina Shyokku No Keizaigaku. Keiso Shobo: [Economics of China Shock]. Tokyo, 2020.

- Pelkmans, J. The ASEAN Economic Community: A Conceptual Approach. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2016.

- Severino, R. C. Southeast Asia in Search of an ASEAN Community: Insights from the Former ASEAN Secretary-General. Institute of Southeast Asia: Singapore, 2006.

- Shimizu, K. ASEAN Ikinaikeizaikyoryoku No Seiji Keizaigaku [Political Economy of Intra-ASEAN Economic Cooperation. Kyoto: Minerva Shobo, 1998.

- Shimizu, K. “East Asian Regional Economic Cooperation,” In East Asian Regionalism from a Legal Perspective,edited by T. Nakamura, 3–24. Abindon: Routledge, 2009.

- Shimizu, K. “ASEAN to Higashiajia Keizaitougou” [ASEAN and East Asian Economic Integration].” In ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai No Sousetsu to Nihon, edited by K. Ishikawa, K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, 289–307. Tokyo: Bunshindo: Establishment of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan, 2016.

- Shimizu, K., “Countering Global Protectionism: The CPTPP and Mega-FTAs,” Trade and Economic Connectivity in the Age of Uncertainty, Panorama Insights into Asian and European Affairs, Singapore: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, August, 2019. https://www.kas.de/documents/288143/6741384/panorama_trade_KazushiShimizu_CounteringGlobalProtectionism_TheCPTPPandMega-FTAs.pdf/05e5307d-63f1-87eb-6680-5b8458836555?t=1564644939772

- Shimizu, K., “ASEAN Keizaitougou No Shinka to Amerika TPP Ridatsu” [Deepening of ASEAN Economic Integration and the US Withdrawal from the TPP]. In Korekarano Higashiajia: Hoshyu Shyugi No Taito to Mega FTAs [East Asia in the Future: The Rise of Protectionism and Mega FTAs], edited by F. Kimura, 74–106. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2020.

- Shimizu, K. Sekaikeizai to ASEAN Keizaikyoudoutai” [World Economy and ASEAN Economic Commuity. In ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai No Sousetsu to Nihon [Establishment of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan], edited by K. Ishikawa, K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, 3–24. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2016.

- Sukegawa, S. “Buppinboueki No Jiyuka Hemuketa ASEAN No Torikumi” [ASEAN’s Efforts to Liberalize Trade in Goods]. In ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai No Sousetsu to Nihon [The Establishment of ASEAN Economic Community and Japan], Edited By K. Ishikawa, K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, 69–99.Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2016.

- Sukegawa, S. “ASEAN Economic Community and Japan]“ASEAN’s Initiatives for Free Trade in East Asia under AEC.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 10 (2021).

- Sukegawa, S. Buppinboueki No Jiyuka Enkatsuka Hemuketa ASEAN No Torikumi” [ASEAN’s Efforts to Liberalize and Facilitate Trade in Goods]. In ASEAN Keizaikyodoutai to Nihon [ASEAN Economic Community and Japan], edited by K. Ishikawa, K. Shimizu, and S. Sukegawa, 43–59. Tokyo: Bunshindo, 2013.

- The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), “Economic and Trade Agreement on the government of the US and the government of China,” Accessed January 10, 2021. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/phase%20one%20agreement/Economic_And_Trade_Agreement_Between_The_United_States_And_China_Text.pdf.

- Urata, S., R. Ushiyama, and S. Kabe, eds. ASEAN Keizaitogou No Jittai. Bunshindo: [The Reality of ASEAN Economic Integration], Tokyo, 2015.