ABSTRACT

The article examines the evolution of Vietnam–China relations in the post-Cold War to identify the factors that shapes its dynamics. It finds that the bilateral relations have been significantly changed overtime, from strategic antagonism to ideology-shared partnership and subsequently from economic sistership to security rivalry. The two countries’ worldviews have gradually diverged. Given geographical nearness is a constant, such a course is driven by the interactions of four factours, including shifts in security environment, internal factional politics, economic calculations, and rising nationalism. At different points of time, some factor rises dominantly and these others matter less. However, it is observed that since the normalization in 1991 shared ideology figured less and less significantly.

1 Introduction

The last decade has witnessed increased interest in making sense of Vietnam–China relationship from policy and academic circles. Not only has the rise of China and its effects on regional politics drawn much attention, but how Vietnam stood at the fault line of an epochal power shift is also a source of academic inquiry. Rising tensions in the South China Sea were of particular concern as any conflict outbreak there would have had serious repercussions on regional stability and global sea-borne commerce. It remains intriguing to many regional watchers how two ideologically similar and economically knotted neighbors had failed to find solutions to their disagreements over an array of remote, small, and barren features in the middle of the sea between them.

The evolving Vietnam–China relationship has raised several challenges to existing theoretical paradigms. First, though identifying themselves as communist countries, Vietnam and China have increasingly become distant strategically. Second, increased economic interdependence has not brought about pacifying effects as liberalists argue. Vietnam and China clash with each other more often in the South China Sea, which is called as the East Sea in Vietnam and the South Sea in China. Third, though public sentiment has turned sour in both countries, the political elites on both sides attempted to keep a lid on it. Lastly, the extent to which an extensive web of party-to-party dialogs impacted on overall relations remains understudied.

The article is purported to explain the Vietnam–China relations in the post-Cold War from the four-factor analysis, including security and international environment, domestic politics, economic interests and people’s perception and identity. To this end, it traces the evolution of Vietnam–China relations throughout the course of history to find out the interplay of the four factors. The article argues that the four factors are critical to understand the nature of the relationship, but their influences have varied at different times. Over the long course, security is always the most fundamental determinant in Vietnam’s relations with China, though political opportunism and economic pragmatism may come to the fore under some circumstances.

2 Four determinants of Vietnam-China relations

2.1 Security and international environment

Security no doubt features significantly in the relations of two neighboring countries. The combination of the asymmetry of power and geographical proximity created a permanent concern of the smaller neighbor and inherent sense of superiority on the other side. It has been the case of Vietnam’s dealings with China throughout the course of history. The sense of insecurity was ingrained in the history textbooks, which always reminds schoolboys and girls about the legendary King An Duong of the Au Lac Kingdom, who lowered his guard on his enemy’s deceptive reconciliatory scheme and lost his kingdom to the northern empire, Nan Yue. The fall of Au Lac in 179 BC is often marked as the beginning of the darkest chapter in the history of Vietnam resulting in 1000 years of Chinese suzeraintyFootnote1 The account was also engraved in national history as a life-or-death lesson of being watchful against the northerners’ hidden aggressive attemptsFootnote2

For China, Vietnam is often viewed as part of the empire, or its sphere of influence. In the feudal time, Chinese imperial courts expected that rulers in the southern realm paid respect and tribute to the Central Kingdom. In the modern world, the Chinese communists sought to have preeminent influence over their Vietnamese comrades. They competed with the Soviet Union to assist the Vietnamese communists to fight against France and the US. When Vietnam decided to side with the Soviet Union in 1978 and overthrow the China-backed Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, Beijing was enraged and waged a border war against Vietnam in 1979.

The resumption of relations in 1991 dismantled some imminent concerns but not the root cause of suspicion. Vietnam’s vulnerability remained. Unsettled land border, disputes over offshore features in the Paracels and Spratlys, and maritime boundaries remained contentious points between two neighbors. There is genuine concern about the possibility that China would resort to force to settle the existing disputes. On the other side, though having no interest in reverting to “teeth and lips” relationsFootnote3, Beijing did not want Vietnam to move far away from the Chinese orbit. Any military bases of other powers on Vietnamese soil would complicate China’s defense calculations. In the modern world, Vietnam’s security is not as dismay as in the past as it had choices to balance against the Chinese power.

2.2 Domestic politics

It is often argued that foreign policy is the extension of domestic politics. Logically, domestic agendas serve as significant determinant of the foreign policy in most countries as most leaders are chosen by the country’s constituents and often seek to retain political power and maintain policy coalitionsFootnote4 Also, the decision-making process is often heavily influenced by a range of domestic actors such as the heads of state and government, institutions like ministries, agencies, businesses, or interest groups operating in the one political and legal environment. One country’s political system clearly shapes its fundamental international interests and the way the foreign policy is deliberated and made. Vietnam and China are not exceptions.

The similarity in political ideals and system has been glue for Vietnam and China in many circumstances. Both countries have been ruled by the Communist Parties single-handedly, which were de facto allies in the early days of the Cold War. The ideological ties were supported by personal ties between the founding fathers of the respective communist parties, Ho Chi Minh and Mao-Ze Dong, in 1940s. The sense of comradeship in the class struggle and the common resentment against Western supremacy served as the driving force for their solidarityFootnote5 Ideology was also an important catalyst for normalization of relations in 1991. Both communist parties shared interests in resisting the triumphalism of the liberal democratic ideal after the Cold WarFootnote6 However, it remains unclear how communist ideology would work at time of rising nationalism or when their national interests are at odds.

It is important to note that ruling communist parties in both China and Vietnam were not monolithic as they appeared publicly. The demise of paramount revolutionary leaders, such as Dang Xiaoping in China and Le Duan in Vietnam, gave room for factionalism. Within the party structure, different coalitions with different policy orientations arose, though they all swear allegiance to the party. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was allegedly divided between “elitist” and “populist” coalitions, or between liberal-minded reformist and conservative hard-liner campsFootnote7 Inside the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP), the line was drawn between the “conservatives” and modernizersFootnote8, or between conservative ideologues and nationalist pragmatistsFootnote9 Interaction between different factions, either as competition for power, or consensus-making on specific policy issues and how they should appear to the public basically defined the party’s politics and policy orientations. In both China and Vietnam, intra-party politics is more important than populism.

2.3 Economic interests

International relations theorists often disagree with each other about the impacts of trade and economic relations. The liberalists often argue that economic interdependence would serve as a brake on warlike intents. It means the more the countries trade with each other, the less the possibility of war. However, realists like Kenneth Waltz argue that “interdependent states whose relations remain unregulated must experience and will occasionally fall into violence.” He continues, “if interdependence grows at a pace that exceeds the development of central control, then the interdependence hastens the occasion of war.”Footnote10 The case of Vietnam and China would indicate that liberalism has some limits.

As the Cold War ended, the economic factor increasingly mattered in Vietnam–China relations. In the past, economic ties between China and North Vietnam were limited and one-sided. Vietnam was a net recipient of China’s food and economic aid. As relations were normalized in 1991, border trade was resumed and expanded quickly as discussed in subsequent sections. Infrastructural connectivity was extended through roads and rails. The two sides are important to each other economically in three aspects, developmental thinking, physical connectivity, and global supply chains. The expanded economic ties have added another layer of complexity to the two neighbors’ already-complex relations. While they serve as glue for most of the time, they could be seen as a source of division in time of tensions.

2.4 People’s perceptions and identity

Perceptions and identity are often the factors which are understudied in the field of international relations. The key reason is perhaps perception and identity are very fluid concepts which are not easy to be identified, measured, and analyzed. The causal links between what are considered as perceptions and identity and the choice of foreign policy options are often difficult to identify. Defined as perception of one’s very self in relations with others, national identity has often been constructed through a long course of history and in a specific geographical setting and has significant influence over the way one state contemporarily views others and behaves internationally.

The case of Vietnam and China illustrates that perception and identity matter in their relations. Obviously, both can be understood as having multiple identities, including self-positioning (for example, China as the central kingdom, Vietnam as the southern country), ideology-based identification (socialist states), or geographical identity (Vietnam as a Southeast Asian nation, while China is the northern power), or developmental identity (both Vietnam and China consider themselves as developing countries). Depending on these different identities, Vietnam and China behave similarly and yet differently. As socialist countries, they share the goal of perpetuating the communist rule in their own countries and struggling against so-called “peaceful evolutions”, attempts to overthrow the communist rule by provoking popular uprisings by the West. As developing countries, they push for a positive trading system that gives preferential treatment to less developed states and a relaxation of CO2 emissions.

Yet, the identity of Vietnam as a nation has been defined by multiple struggles against China throughout the course of history. For the Vietnamese, China is the most common reference point. The Vietnamese consider themselves as Southerners, and the China as Northerners. The Chinese have always regarded themselves as the Central Kingdom while the Vietnamese consider themselves as the rulers of the southern land. In the Vietnamese history textbooks, there have been ample references to heroic and patriotic resistance against the invaders of the north. This national consciousness is behind modern days nationalism in both countries which has shaped their international conduct.

Based on these four factors, the next sections will investigate Vietnam-China relations chronologically to measure how these four factors have unfolded to shape the interactions between the two countries. It is clear that these four factors have interacted. From the vantage point of four factor analysis, Vietnam-China’s relations in the post Cold War can be divided into different periods where one or two factors might be more prominent than the others. Between 1991 and 2000, in the uncertain world after the setback of the communist movement, shared communist ideology figured significantly in the interactions between two neighbors, prompting them to normalize and consolidate political ties. That laid the ground for booming economic relations in the first decade in the 21st century. However, it is observed that despite increased economic interdependence, Hanoi remained worried about imbalance of power in the region and China’s designs in the South China Sea. Since 2009, China’s overt assertiveness and aggressiveness in the maritime domain caused uneasiness in Hanoi. Along the path, Hanoi increasingly associated with international law, global rules and norms, and became more determined to build up its own resilience and a network of multiple free trade agreements (FTAs) to dilute China’s economic clout.

3 Comrades in an uncertain world: surviving globalization

In the post-Cold War, domestic politics, especially the concerns about regime security, were of paramount importance to both Vietnam and China. The breakdown of the socialist bloc in Eastern and Central Europe resulted in a thaw between the two neighbors, who saw each other as de facto ideolgical allies in the triumphalism of liberal democracy. Vietnam and China moved to normalize their relations after the official visit of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam Do Muoi and Head of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) Vo Van Kiet to China in November 1991 after over a decade of hostilityFootnote11

The tyranny of circumstance created a convergence of interests. China needed Vietnam for influencing Cambodia affairs, stabilizing its southern border, and resisting the pressure from the West after the Tiananmen crisis. On the part of Vietnam, the dire economic situation and decline in the Soviet Union’s economic support prompted Hanoi to break political isolation and economic embargo imposed against it. Vietnam’s withdrawal from Cambodia activated party channels for dialogue with China over the settlement of the conflict. Ending hostility with China had been considered as a foreign policy priority since the 6th Party Congress in 1986. The Party’s Political Report off 1986 stated,

We hold that the time has come for the two sides [Vietnam and China] to enter into negotiations to solve both immediate and long-term problems in relations between the two countries. Once again, we officially declare that Vietnam is ready to negotiate with China at any time, any level and in any place to normalize the relations between the two countries (emphasis added)Footnote12

In the post-Cold War period, Vietnam and China are two remaining socialist states, but not allies. As the South Union collapsed and Cambodia was handed over to the UN trusteeship, Vietnam emerged as a normal state without a patron and not as a client state. Facing a loss of orientation and with insecurity, some conservative ideologues in Vietnam wanted to roll back relations with China to the “lips and teeth” relationship of the past. However, their Chinese counterparts showed no interest in reviving the ideal of an “alliance” among Asian socialist statesFootnote13 The joint communiqué issued after the meeting of senior leaders of the two countries in September 1990 stressed the principles of respecting each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, noninterference into one another’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefits, and peaceful co-existence. It also said that two communist parties of Vietnam and China will restore normal relations on the basis of independence, self-reliance, complete equality, and noninterference into each other’s affairs (Nhan Dan, November 111,991). It meant that Vietnam and China entered a new form of equal relationship, which might not have existed before.

As animosity receded, relations between Vietnam and China gradually warmed up. The exchange of visits between Vietnamese and Chinese leaders was routinized as they communicated their expectations of the relationship and discussed expanding cooperation. China appeared sensitive to Vietnam’s security concerns by accepting three working groups to discuss solutions to the disputes over the land border, the maritime boundary in the Gulf of Tonkin, and maritime issues in the South China Sea proper. In exchange, Vietnam accepted the one-China principle, and shared views with China on mostly contested international affairs, especially against US “interference”. Border trade was resumed and grew quickly from US$31 million in 1991 to US$600 million in 1992 to US$ 1 billion in 1995 and 1.4 billion in 1997 and 2.46 billion in 2000. In 1992, in fear of a massive influx of Chinese consumer goods, Vietnam adopted a protectionist policy to ban 17 imported goods from ChinaFootnote14 Also, Vietnam was reluctant to accept Chinese investment, especially in the border areas, even though such infrastructural upgrade in these regions would facilitate tradeFootnote15 By the end of 2000, Chinese investment in Vietnam accounted to US$180 million with over 80 projectsFootnote16

However, the economic factor was however not the determining factor shaping Vietnam-China relations in this period. Trade with Vietnam was important to some southern Chinese provinces but relatively insignificant to China overall. From the Vietnamese side, though there was much potential to trade with China, the Vietnamese authorities were reluctant to reach out to China. The anxiety about Chinese economic domination was clearly a factor tempering Hanoi’s opening up to China economicallyFootnote17 It was actually the convergence of political interest, as reflected in the common need to maintain communist rule in the two countries that dominated the relationship. The two sides no longer considered their relations as “lips and teeth” but were “linked by mountains and rivers” (proximity) and “similar conditions”. An article in Nhan Dan Newspaper on October 16, 1998 indicated four areas of similarities between the two countries,

persistence in pursuing socialism according to each country’s situation; juggling economic development and stabilizing the local political situation; the simultaneous mobilization of domestic resources and maximization of international cooperation; and last but not least, the efforts to ensuring the continuation of communist leadershipFootnote18

Most significantly, the two countries, especially the conservative circles, shared concerns about “peaceful evolutions”, which is the code word for attempts to undermine the communist rule by the US and other western powers through the spreading of democratic values. After the Tiananmen crisis, Chinese officials were critical and vigilent of Western’s attempts to impose the democratic and human rights normsFootnote19 However, Beijing was reluctant to shoulder the burder of socialist internationalism as the Soviet Union did. The main reason was that it wanted to trade with the West. Though not preferring an alliance, China still wanted to maintain a relatively close relationship with Vietnam, and not to let it fall into the influence of hostile power.

After normalization, the two countries established a range of institutionalized dialogs at four levels. The regular exchange of high-level visits by heads of the parties and governments was the most importantFootnote20 Between 1991 and 2000, 13 visits by senior leaders were made, and dozens of joint statements were issued. Such dialogs set out major principles and directions for the relationship, which would be implemented by lower-level meetings. The two sides also set up meetings at ministerial, vice-ministerial and expert (working group) levels to find ways to expand cooperation and resolve “issues left by history”, i.e., territorial and maritime disputes. It is observable that under the top level, dialogue at lower levels between two countries expanded quickly. In 1998, more than 100 delegations of two countries visited each other.

Party-to-party ties were rather unique to Vietnam-China relationship. Regular high-level party leaders’ meetings were ceremonious, but they served as venues for communicating strategic reassurance. On the part of China its peaceful intentions and commitment to resolve disputes by peaceful means was communicated. Vietnam communicated its independent strategic posture, and that it would not be a ground for hostile powers against China’s national interests. Specific issues in resolving disputes and expanding cooperation was left to governmental meetings at different levels, and the remaining contentious issues would be elevated to high-level leaders’ meetings for political decisions. Such a modus operandi yielded concrete results such as the reestablishment of rail service between Guang xi (China) to Lang Son (Vietnam) in 1996, and the agreements resolving the land border and the Gulf of Tonkin boundary dispute in 1999 and 2000 respectively.

A strong institutional foundation provided a basis for trust-building and expanded cooperation. The year of 2000 marked a milestone in Vietnam–China relations. The two sides signed the Joint Statement on Comprehensive Cooperation between Vietnam and China in the new century” which proposed all-round cooperation. In 1999, during the visit of Secretary General Le Kha Phieu to Beijing, a motto, usually refered to as “16 golden words” was adopted for their relationship, it called for “friendly neighborliness, comprehensive cooperation, long-term stability, and furture-forward looking.”Footnote21 Prominent scholar of the Vietnam-China relationship, Brantly Womack, viewed such progress as “normalcy” as bilateral relations evolved from confrontation to “normalcy” or “mature asymemtry” where mutual understanding and expectations have been establishedFootnote22

Though much characterized in ideological term, Vietnam–China relations in the first decade after the Cold War fundamentally operated on a nationalist and pragmatic basis. The ideological factor had little impact on the key tenets of two countries’ foreign policies. Socialism serves mostly as a rationale for sustaining the communist rule internally in both countries, not as a tool of foreign policy. Specifically, China’s benign and cooperative behavior in this period stemmed from its strategic interest in maintaining peaceful environment and neighborhood to focus on development. The perceived hostile attitude of the Western powers made China more receptive to Southeast Asian countries’ interests. In this period, China actively reached out to ASEAN and played a constructive role in managing the effects of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997.

Though some ideological conservatives in Hanoi still preferred some form of socialist solidarity, Vietnamese nationalist elites increasingly realized that China’s foreign policy was guided by its national interests, not by ideology. Though courting China ideologically, Vietnam did not acquiesce in its claims to sovereignty over the Paracels and Spratlys and did not accommodate China’s demand to drop the Paracels from the agenda of the joint working group on “maritime-related issues”. Hanoi increasingly associated its interests with international law and stood firmly against any acts deemed as an infringement of its maritime interests. While expanding cooperation with China, Vietnam also moved to seek admission to ASEAN and improve its relations with Western countries, including its old foe, the US. Vietnam’s isolation symbolically ended in 1995 when Vietnam joined ASEAN, normalized relations with the United States, and signed framework agreement with the European Union. Beijing did not try to block Hanoi’s efforts to diversify its foreign affairs portfolios. Fundamentally, in the first decade after the Cold War, Vietnam and China estalished the foundation for the modern relationship between two independent sovereign states.

4 Expanding economic ties

Turning to the 21st century, Vietnam and China gradually shifted to a new phase where economic interdependence featured more significantly but political resentment gradually surfaced. As a rising power, China was seen expanding its interests and flexing its political and economic clout to seek its own sphere of influence. As China’s power grew, Vietnam like other ASEAN states was naturally drawn closely to the Chinese center of gravity, and at the same time, was concerned about Beijing’s intention to seek regional domination. A rising China offered enormous opportunities for trade and investments. At the same time it appeared threatening to many. China promised a peaceful rise, but small neigbours were increasingly concerned about its behavior.

Both Hanoi and Beijing needed economic development to legitimize the communist rule. The policy of openness and integration plugged two countries into the global value chain which in turn entangled the two economies. After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China leveraged its enormous potentials and global markets to become a global manufacturing powerhouse. Regional economies, including Vietnam, became naturally more dependent on China in terms of trade, investments, and tourism. Observably, Vietnam followed much of China’s economic footpath, seeking international economic integration.Footnote23 After signing a bilateral trade agreement with the United States in 2000, Vietnam proceeded with the next objective, gaining membership at the World Trade Organization. As a result, the Vietnamese and Chinese economies became linked bilaterally, and multilaterally.

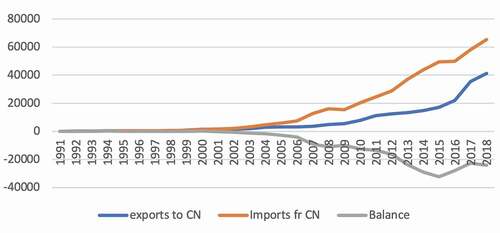

The first decade of the new century witnessed greater economic ties between Vietnam and China, but wider political divergence between the two. Trade between them increased quickly from US$3.0 billion in 2001 to 3.6 billion in 2002, 4.9 billion in 2003, 20.7 billion in 2008 and 27.3 billion in 2010, 58 billion in 2014. In 2010, trade with China accounted for 17% of Vietnam total foreign trade ee . In 2004, China became Vietnam’s largest trading partner. Notably, since 2001, Vietnam faced a chronic and unhealthy trade deficit with China, which was markedly different from the previous period when Vietnam enjoyed a favorable trade balance with China. The trade deficit with China rose from 0.2 billion in 2001 to more than 20 USD billion in 2012, and 28.9 USD billion in 2014 (see ).Footnote24 However, China still lagged other countries (South Korea, Japan, Singapore) in terms of direct foreign investments into Vietnam.

Figure 1. Vietnam’s trade from China, period between 2000 and 2018.

Table 1. List of vietnam’s FTAs, December 2018

Though the balance of accounts tipped favorably toward China, the Vietnamese leadership was little concerned initially. It was obvious that Vietnam had to use its surplus with other partners to compensate for its deficit with China. There were warnings about Vietnam’s trade dependence on China. Concerns were not just about the unhealthy trade deficit. Japan-based Economist Tran Van Tho points out that the mode of trade between Vietnam and China was also abnormal and harmful as Vietnam exported mostly raw materials (e.g., coal, minerals, rubber) and imported from China higher value-added products (e.g., machinery and spares, iron and steel, and consumer goods). As the terms of trade for raw materials declined, this problem was only worsening. Also, Vietnam also relied on China for a range of intermediary products such as leathers, yarns and garments and consumer goodsFootnote25 Around 50% of the inputs to Vietnam’s garment and textile industry are composed of imports from ChinaFootnote26 Chinese companies have won most of the EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) contracts for Vietnam’s key industrial projectsFootnote27 Still, Vietnamese officials believed that such dependent relations are necessary at the early stage of development, and still benefit Vietnam.

The trade relations between Vietnam and China in the first decade of the 21st century indicated that both countries put the emphasis on development. It was first and foremost facilitated by “never-been-better” political relations between the two countries after the conclusion of the agreements on the land border and maritime delimitation in the Gulf of Tonkin. The good political environment and high level of trust removed obstacles along the border and facilitated trade ties between the two countriesFootnote28 Second, import expansion in both countries was fueled by sustained economic growth in two countries. China became the most important market for Vietnamese agricultural products, including cassava and cassava products, coal, rubber, and rice. In return, it provided input materials for Vietnam’s expanding manufacturing, including mobile phones and electronic parts, garments and textiles for apparels, and leather for its footwear industry. In 2013, China accounted for 35% of Vietnam’s imports of machine, equipment, tools, and instrumentsFootnote29 The difference in development levels made the two economies complementary and geographical proximity also served to facilitate trade. As mentioned above, continuous trade growth between Vietnam and China was fostered by the deeper integration of both countries into the global production network and value-added chain through a range of free trade regimes.

5 Hanoi’s persistent security uneasiness

Yet, greater interdependence in terms of trade and economy did not remove suspicion of the nationalist circle in Vietnam. Though the disputes over the land border and maritime delimitation in the Gulf of Tonkin were by and large settled by 2000, concerns in Hanoi were about a set of intractable sovereignty and maritime disputes in its eastern maritime domain, the South China Sea. Also, strategists in Hanoi were worried about China’s increased influence across Southeast Asia. In private talks in Washington D.C., they conveyed their concern that the US was absorbed on the war on terror, leaving a vacuum in Southeast Asia for China to fill.

There was pressure on Hanoi to increase cooperation with US to balance China’s growing influence. This trend became more pronounced in 2003 when the Central Committee of the CPV adopted Resolution No.8 on the strategy to defend the country in the new situation. Moving away from the ideal of socialist solidarity, the resolution introduced two new concepts “doi tac” (objects of cooperation or partners) and “doi tuong” (objects of struggle). The former was defined as “anyone who respects our independence and sovereignty, establishes and expands friendly, equal and mutually beneficial relations with Vietnam.” The latter referred to “any force that plans and acts against the objectives we (Vietnam) uphold in the course of national construction and defense.”Footnote30 It should be noted that the resolution did not see any country as purely “doi tac” or “doi tuong” but argued that a country could be both a partner in some policy areas and an object of struggle for Vietnam in others:

With the objects of struggle, we can find areas of cooperation; with the partners, there exist interests that are contradictory and different from those of ours. We should be aware of these, thus overcoming the two tendencies, namely lacking vigilance and showing rigidity in our perception, design, and implementation of specific policiesFootnote31

The resolution also instructed,

With the objects of struggle, we can find areas of cooperation; with partners, there are interests that are contradictory and different from ours. We should be aware of these, thus overcoming the two tendencies, namely lacking vigilance and showing rigidity in our perception, design, and implementation of specific policiesFootnote32

Clearly, the resolution departed from an ideology-based perception and a clear-cut distinction between “friend” and “foe” in foreign affairs. It was indicative that national interest (independence and sovereignty, mutually beneficial relations), rather than socialist ideals, guided its foreign policy behavior, when to cooperate and when to stand up. China was no longer a mere partner or collaborator, and the US was no longer just a challenger.

Against this backdrop, Vietnam-China relations were by and large governed by pragmatism rather than shared ideals. Rising China must be balanced. Consequently, Hanoi started engaging in nascent security cooperation with its old foe, the US. Hanoi for the first time in November 2003 sent its Minister of Defense Pham Van Tra to WashingtonFootnote33 One week later, the USS Vandergrift FFG 48, made the first visit of a US Navy vessel to Ho Chi minh City, since 1975. Moreover, Vietnam started cooperating with the United States in counter terrorism, anti-drug smuggling, de-mining, search and rescue, and disaster reliefFootnote34 In the second half of 2003, the Vietnamese Ministers of trade, planning and investment, and foreign affairs, as well as the Vietnamese Deputy Prime Minister traveled to WashingtonFootnote35

Still, Vietnam kept an eye on China while trying to reach out to the United States and other powers for uncertain strategic contingencies. To get the balance right between economic and security needs, Hanoi deliberately restricted military cooperation with United States because it was afraid of sending “a wrong signal” to BeijingFootnote36 Also, while sending a senior leader to Washington, Hanoi also arranged a visit by other senior leaders to Beijing. The reason was not to maintain a position of equidistance between two great powers, but to keep the US in the region as a counterweight to China’s rising power.

6 Maritime contestation

For most the 2000s, the trade deficit with China was viewed largely as a necessity. The dominant view is that steady increases in imports were attributed to the need to build up the country’s manufacturing base and capacity. From the economic standpoint, China was a competitive provider of inexpensive and suitable technologies, machines, and tools for Vietnam’s key industries. Vietnam sat in the middle of the production network, importing inputs from China and processing them into final products for export to US and European Union markets. Therefore, the trade deficit with China was viewed in perspective as Vietnam enjoyed a surplus with the US and the European UnionFootnote37 China clearly benefited from such relations and viewed them in the same way.

However, stronger economic ties between two neighbors could not prevent the deterioration of relations due to rising tensions in the South China Sea. Since 2007, Vietnam was concerned about China’s efforts to block its oil and gas activities in the area it considered as legitimate continental shelf under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In 2009, the tensions in the maritime domain surfaced when Vietnam lodged its submissions to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf and China published the nine-dash line map in its responding note verbales to the Secretary General of the United Nations. Since then, China deployed a large fleet of its maritime law enforcement and maritime milita vessels to enforce this expansive claim. On the other end, Vietnam utilized many channels, both bilaterally and multilaterally, to call for respect for UNCLOS and to highlight Beijing’s unlawful claims and coercive behavior with the hope that internaional public opinion would constrain China.

Tensions culminated in mid-2014 when China deployed the giant Haiyang Shiyou 981 oil-rig to the waters Vietnam considered its Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf off the city of Da Nang. China’s move resulted in a two-month stand-off between Vietnamese and Chinese vessels in the vicinity of the Paracel Islands. During this period, China temporarily halted credit lines to engineering, procurement, and construction contracts (EPC) in VietnamFootnote38 The flow of Chinese tourists was also reduced. In August 2014, right after the rig was withdrawn, the number of Chinese tourist arrivals fell by halfFootnote39 The incident prompted unprecedented a public discourse about the extent and repercussions of Vietnam’s economic vulnerabilities vis-à-vis China. There were apprehensions and many calls for the government to do what they called, “exiting the Chinese orbit.”

At the same time, cyber space was flooded with comments and complaints about China’s toxic products as well as sub-primed infrastructure projects built on Chinese loans, particularly the elevated train in Hanoi. All these reinforced Vietnam’s popular resentment toward China as a whole and suspicion of Chinese infrastructure initiatives such as the One Belt One Road (OBOR) and the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB). Vietnamese scholars questioned such initiatives, regarding them as conduit of Chinese geostrategic ambitionsFootnote40

No doubt, China’s actions in the maritime domain also generated an unspoken sense of economic insecurity in Hanoi. In the row with Japan over its arrest of a captain of a Chinese fishing boat in the vicinity of the Senkaku Islands in 2010, China exerted leverage on Tokyo by halting shipments of rare earths, an essential material for an array of manufactured products such as hybrid cars, wind turbines, and guided missiles, to Japan. This restriction was applied to Japan exclusively as shipments of rare earths were still going to Singapore, Hong Kong and other destinationsFootnote41 In the Scarborough Shoal stand-off in mid-2012, China suspended buying bananas from the Philippines, blaming the quality of the shipments. Such action caused significant damage to the Philippines’ banana farmers, which exported 30% of their products to ChinaFootnote42 Though China denied that this was related to the territorial spat, it was indicative that Beijing was more than willing to use economic clout against its adversaries in territorial disputes. China’s economic coerciveness against Japan and the Philippines generated unease among Vietnamese political elites. In December 2012, Vietnamese Ambassador to the United States Pham Quang Vinh warned China against using trade as weapon to force other countries to change their approaches and to back down from their territorial positionsFootnote43 Hanoi was clearly worried that Vietnam would be the next target of China’s economic manipulation and trade dependence would tie its hands, as was the case of the legal option.

7 Diverging worldviews and incompatible world orders

Three decades after the Cold War, Vietnam and China diverged in their worldviews. Though the two ruling communist parties maintained a range of dialogs, ideology mattered less and less in the foreign affairs of both Vietnam and China, and in their relations. Tensions have been simmering in the South China Sea over the last decade without much hope for peaceful settlements in the near future. Wielding more economic and military power, China increasingly asserted itself as the central power in the Asia-Pacific and aggressively projected its influence in the maritime domain at the expense against existing rules and norms. In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping introduced the One Belt One Road Initiative which aimed to establish land and maritime corridors to link up various parts of the Eurasian landmass to the Chinese core. Although the scheme was later re-branded as the Belt and Roads Initiative (BRI), it reflected Beijing’s ambition to create a China-centric world system.

Since opening up to the world, Hanoi gradually adopted internationalism. In 2011, Vietnam was committed to pursue full integration with the world, which means greater cooperation with the western world. Domestically, Vietnam remained a socialist state ruled by the Communist Party of Vietnam. However, internationally, Vietnam no longer viewed itself as a vanguard socialist state and increasingly positioned itself as a small-and medium sized Southeast Asian nation, which sought all resources possible for national development. In the broader world, Vietnam did not jump on China’s bandwagon and in many circumstances opted for upholding existing internaional law and norms against the latter. The South China Sea is a case in point where Vietnam aligned its claims to the letter and the spirit of UNCLOS and stood firm against China’s hegemonic attempts. In this regard, Vietnam is closer to the Western world than China, prefering the maintenance of a rules-based order.

Particularly, in the economic sphere, Vietnam attempted to reduce its reliance on China. Hanoi’s remedy to its economic vulnerability was not to reduce its trade with China but to diversify its supply chains and markets. After joining the WTO in 2007, Vietnam actively sought to develop a range of free trade agreements (FTA) with the world’s key economiesFootnote44 Negotiations were accelerated between the period between 2012 and 2015. By the end of 2015, Vietnam concluded most of its major FTA negotiations, except the FTA with Israel, EVFTA, RCEP and FTAAP. A short summary at this point showed that, for just a decade, Vietnam achieved FTA arrangements with 55 countries (See )Footnote45 This figure was indicative of Vietnam’s extraordinary commitments to deep international economic integration.

Among these FTAs, the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (FTA) was considered the most important to Vietnam. Generally, the TPP is considered as a critical element of the US’ rebalancing to Asia-Pacific, and the primary vehicle for Washington to shape regional trade rules in the face of rising China. The TPP is far more than just a mere FTA that liberalizes trade in goods and services, as its implementation will necessitate domestic economic and political reforms leading to a more competitive economic environmentFootnote46 The most difficult changes for Vietnam (as well as China), as required by the TPP, are the removal of non-market preferential treatments of state-owned enterprises and the establishment of independent unions to protect the fundamental labor rights and to ensure collective bargaining. In addition, there are a range of TPP principles to ensure fair competition, protection of investors’ rights, protection of copy and patent rights, and environmental sustainability. These institutional reforms are clearly not always compatible with the main tenets of the socialist regime’s traditional governance structure.

Nonetheless, in the longer term, such reforms were necessary to strengthen the economy that had been ravaged by a large but inefficient SOE sector and rampant corruption. Vietnam was seen as the biggest benefactor of the TPP with greater access to advanced members’ markets for its principal products such as aquatic and agricultural products, textile and garments, shoes and leather, and electronic devices. TPP’s “yarn forward” rules of origin regulation, which requires that only yarns made by TPP members may be sold onto the TPP markets, may cause difficulties for Vietnam in the short run. To meet this requirement, Vietnamese producers have to look beyond cheap Chinese yarn to find suppliers in the TPP countries. However, in the longer term, the TPP will help Vietnam attract foreign direct investment and assist it with the development of domestic industries as well as the diversification of Vietnam’s economy away from the current level of dependence on Chinese trade (The Saigon Times, October 12, Citation2015). In other words, the TPP promises to advantage Vietnam at the expense of other competitors including China and provide it with a range of alternatives beyond the China choice.

As mentioned above, by mid-2015, the Vietnamese leadership had to weigh the benefits and risks and decide whether to walk away for the sake of the regime itself or joint the TPP to make the country more prosperous and stronger. The trip by party chief Nguyen Phu Trong to Washington in July 2015 apparently cleared final obstacles to make Vietnam one of the founding members of the TPP. In early 2016, when the CPV was about to convene the 12th National Party Congress, its Central Committee discussed the result of the TPP negotiation and finally approved the signature of the TPP agreementFootnote47 This reflected a broad-based consensus among the Vietnamese leadership on integration into the US-led economic system. A new course has been set in motion. While Hanoi still maintains its strategic autonomy, economically it has already rebalanced to the West. The change was obviously prompted by the internal need to modernize the country and enable it to cope with increased threats and risks emanated from an assertive China. With all these expectation, Trump’s decision to withdraw from the TPP caused enormous disappointment in Vietnam. Vietnamese leaders on several occasions directly called on the US administration to come back to the TPP (Nikkei Asian Review, November 232,017; AFP, September 142,018). Even when the US left, Vietnam showed a high level of determination to work with its partners, particularly Japan, Australia, and Canada, salvage this trade agreement, which was later renamed as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific PartnershipFootnote48

Though being aware of this vulnerability, the Vietnamese government has not shunned China economically. Vietnam still welcomed foreign investments from China. It also allowed the usage of Chinese currency, yuan, as means of payment in 7 provinces bordering China. Hanoi participated in the ASEAN-centered initiative on Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and took part in discussions on China’s infrastructural development initiatives. During visit of party chief Nguyen Phu Trong to Beijing in April 2015, Vietnam and China agreed to establish a task force for infrastructure and financial cooperationFootnote49 It was clear that in a thirst for infrastructure development, Vietnam did not want to be left out from these China-led groupings and miss any source of finance at a time of global economic difficulty, especially at a time Vietnam would not be able to borrow from the Western countries with preferential rates. Despite such efforts, Vietnam’s participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiatives has been rather shallow, as compared to its Southeast Asian neighbors such as Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia and even Indonesia. Rather than looking for new projects, Vietnam pushed for alignments between the existing “two corridors, one economic belt” and China’s proposed BRI. The Vietnamese government was obviously more cautious than ever with Chinese loans. In August 2016, Quang Ninh province reportedly withdrew from its proposal to obtain loans from China to build the highway from Van Don to Mong Cai because of “worries about Chinese contractors”. Instead, it sought domestic investors for the projectFootnote50 Since then, there has been a public debate about the implications of Chinese loans, citing a range of risks from obligations to involve Chinese enterprises, possible influx of Chinese workers, high interest rates, lack of transparency, as well as weaknesses on the part of Vietnam to manage such risks. It is observed that since 2014, the government was under increased scrutiny from the pubic in its economic relations with China. In June 2018, Vietnam’s National Assembly had to put off a project to build four special economic zones in the face of a rising tide of popular anger which was regarded these zones as giving way to Chinese penetration iinto Vietnam.

It is also noted that the Vietnamese leadership has been keen on their economic reform agenda to strengthen economic self-reliance. After a decade-long delay, Vietnam gradually intensified crackdowns on corruption, initiated the privatization of state-owned companies, narrowed the range of banned and restrictive industries, trimmed the administrative procedures for economic activities, and most importantly pushed for the expansion of the private sector. In June 2017, at the fifth plenary of the Central Committee, the Vietnamese leadership adopted Resolution No.10 to develop the private economy. This resolution was indicative of consensus in the Vietnamese political circle about the significance of the private sector to the overall economy, which is considered as “an important engine for economic development.”Footnote51 It was realized long ago that Vietnam’s major vulnerability was its weak supporting industries in its export-oriented development model. As mentioned above, it was Vietnam’s reliance on manufacturing inputs from China for its main export industries, including textile, garments, footwear, … All these were indicative of a fundamental shift toward a greater focus on domestic reforms to strengthen the foundations of the national economy amidst global uncertainties.

8 Conclusion

Vietnam-China relations has shown complexity that it cannot be explained by any single theory of international relations. In the post-Cold War, such relations have evolved from hostility to friendship, from economic estrangement to interconnectedness, and then from camaraderie to increased antagonism. These changes have been determined by the interplay of four facters including security and international environment, domestic politics, economic interests and people’s perception and identity. It was obvious that ideology-based solidarity matters less and less in defining their relationship and economic and political pragmatism became increasingly influential.

The fall of the socialist bloc and the Soviet Union provided a new context. As ideology's influence declined in their foreign affairs, Vietnam and China became two independent states. The shared ideal of communism clearly created a common sense of purpose, but it no longer dictated both countries’ foreign policy, and delineated the terms of their relationship. It was the common effort to defend communist rule and the shared objective to maintain a stable neighborhood for economic development, which was the key source of legitimacy for both communist parties. This convergence of strategic interest brought the two countries closer and facilitated the settlement of long-standing disputes over the land border and maritime boundary in the Gulf of Tonkin.

After political reconciliation, economic pragmatism dictated the terms of Vietnam-China relations for most the first decade of the 21st century. Both countries adopted market-based economic reforms but retained a strong state role through various means. With the opening-up and complementary nature of the two economies, the two countries were increasingly linked economically through trade and investment. Though being uneasy about China’s greater regional clout, Vietnam accepted an increased trade deficit with China as it was seen as necessary to build up its manufacturing base for the sake of economic development. China became Vietnam’s biggest trading partner and tried to use its economic leverage to get favorable terms in economic relations and impose its political will if needed.

The subsequent events in the 2010s were indicative of Vietnam’s core interests, which was to guard its sovereignty against China. China’s assertiveness in the maritime domain gradually undermined Hanoi’s strategic trust in Beijing. There were real concerns in Hanoi about its weakened position in the South China Sea vis-à-vis China due to security vulnerability and economic dependency. Beijing’s manipulation of economic power for political ends exacerbated Hanoi’s concerns about its vulnerabilities and economic dependency at a time of economic openness. After all, neither ideology nor economic interdependence can constrain China’s geopolitical ambition. Vietnam’s response to increased challenges from China is not only to seek diversification to reduce the impacts of China’s power but also to build up its resilience and capacity to weather external changes. That difference will continue to define Vietnam-China relations in decades to come.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Do Thanh Hai

Dr. Do Thanh Hai is a Non-Resident Fellow at the East Sea Institute of the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam (DAV). He obtained his doctorate from the Australian National University. He is the author of Vietnam and the South China Sea published by Routledge in 2017 and co-editor of The South China Sea published by Routledge in 2019 and Maritime Issues and Regional Order in the Indo-Pacific published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2021. The opinions expressed in the article are solely the author’s own, which do not necessarily reflect the views of his institutions. The author would like to thank Prof. Akio Takahara (University of Tokyo), Prof. Leszek Buszynski (Australian National University), and Dr. Yongwook Ryu (Singapore National University) for their comments and suggestions to improve the article.

Notes

1 Quynh, Dai cuong Lich su Viet Nam [Introduction to History of Vietnam], 59–60.

2 Nguyen, “No than An Duong Vuong – Tu Huyen thoai den Su that Lich su” [King An Duong’s magic crossbow – From Myth to Historical Reality].

3 In the Second Indochina War, given the shared communist ideology, the Chinese propaganda often described Vietnam and China were “as close as lips and teeth”.

4 See Neack, The New Foreign Policy- power seeking in a globalized era (2nd Ed.).

5 Womack, China and Vietnam: Politics of Asymmetry, 164.

6 Hayton, Vietnam and the United States: An Emerging Security Partnership, 10–1.

7 See Lai, “‘One party, two coalitions’ – China’s factional politics”.

8 See Vuving, “Vietnam: A Tale of Four Players.”

9 See Do, Vietnam and the South China Sea: Politics, Security and Legality.

10 Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 138.

11 Nguyen, Quan he Viet-Trung truoc su troi day cua Trung Quoc [Vietnam-China relations at a time of China’s rise], 44.

12 Thayer, “Coping with China,” 352.

13 Womack, China and Vietnam: Politics of Asymmetry, 214.

14 Womack, “Sino-Vietnamese border trade: The edge of normalization,” 506.

15 Womack, China and Vietnam: Politics of Asymmetry, 216.

16 Cheng, “Sino-Vietnamese relations in early twenty-first century,” 385.

17 See more Gu and Womack, “Border Cooperation between China and Vietnam in the 1990s”.

18 Quoted in Guan, “Vietnam-China Relations since the End of the Cold War,” 1137.

19 Cheng, “Sino-Vietnamese Relations in Early Twenty-first Century,” 384.

20 See the full list of high-level visits between Vietnam and China between 1991 and 2006 in Hiep, “Vietnam’s Hedging Strategy against China since Normalization,” 347.

21 Tran, “Quan he Viet Nam – Trung Quoc: Nhin lai va Di toi,” [Vietnam-China relations: Review and a look forward]. The Vietnamese version is “Lang gieng huu nghi, Hop tac toan dien, On dinh lau dai, Huong toi tuong lai.” The Chinese version is “long-term, stable, future-oriented, good-neighborly and all-round cooperative relations.”

22 Womack, “Sino-Vietnamese Border Trade: The Edge of Normalization”, 212–3.

23 Resolution No.07-NQ/TW on International Economic Integration, November 272,001.

24 Yang, “China-Vietnam Relational Asymmetries,” 135; Pham Huyen, “20 ty USD tu Trung Quoc vao Viet Nam di dau mat?” [US$20bn from China to Vietnam: Where has it gone?]. The deficit is higher according to the Chinese statistics. There is a big difference between Vietnamese and Chinese figures. In 2014, the Vietnamese figure of Vietnam’s deficit to China was US$28.9 billion, while the Chinese figure was US$43.8 billion. The Chinese figure may include unregistered cross border trade or smuggles.

25 See Tran, “Viet Nam 40 nam qua va nhung nam toi: Can mot nen kinh te thi truong dinh huong phat trien,” [Vietnam in last 40 years and years to come: In need of a development-oriented market economy].

26 “Nguyen phu lieu det may: 48% nhap tu Trung Quoc,” [Textile and garment industry materials: 48% imported from China].

27 Hiep, “Vietnam: Under the Weight of China”.

28 Phan, “Dac trung cua thuong mai Trung-Viet va phan tich nguyen nhan cua no,” [Characteristics of Vietnam-China trade relations and its reasons]. Vietnam Institute of China Studies, September 8, (Phan, Citation2010).

29 Hiep, Living Next to the Giant: The Political Economy of Vietnam’s Relations with China under Doi Moi, 102.

30 Mai, “Van de doi tac-doi tuong trong chien luoc bao ve To quoc,” [Partners and object of struggle in the strategy to defend the country].

31 Thayer, “Vietnamese Diplomacy, 1975-2015: From Member of the Socialist Camp to Proactive International Integration,” 10.

32 Ibid.

33 Thayer, “Vietnamese Diplomacy, (Thayer, Citation1975–Citation2015): From Member of the Socialist Camp to Proactive International Integration,” 10.

34 Storey, “Vietnam and the United States Citation2004–Citation2005: Still Sensitive, but Moving Forward,” 6.

35 Vuving, “Strategy and Evolution of Vietnam’s China Policy: A Changing Mixture of Pathways,” 818.

36 US Embassy in Hanoi, “ASEAN Partnership, Human Rights Dialogue, Embassy Compound discussed with Assistant Foreign Minister”.

37 Nguyen, “Tai sao Viet Nam lai nhap sieu manh tu Trung Quoc”.

38 Bowring, “Vietnam Yields Cautionary Tale over Chinese Investment”.

39 Vu and Nguyen, “The (Citation2014) Oil Rig Crisis and Its Implications for Vietnam-China Relations,” 85.

40 Denyer, “China’s Assertiveness Pushes Vietnam toward an Old Foe, the United States”.

41 Bradsher, “Amid tension, China blocks vital exports to Japan”.

42 “The China-Philippines Banana War”.

43 “Vietnam Says China Must Avoid Trade Weapon in Maritime Spat”.

44 In addition to the ASEAN-led FTAs, Vietnam has negotiated a range of FTAs with Japan, Chile, South Korea, Laos, Eurasian Economic Union (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Armenia), European Free Trade Association – EFTR (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland), and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (Canada, Mexico, Peru, Chile, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Vietnam).

45 An, “Trien vong thuong mai Viet Nam ‘sang’ chua tung co voi 14 hiep dinh thuong mai tu do sap hoan tat,” [Prospect of Vietnam’s trade has never been bright with 14 FTAs in completion].

46 “The Pact is a Win for Prosperity and Peace”.

47 “Thong bao hoi nghi lan thu 14 Ban Chap hanh Trung Uong Dang khoa XI,” [Notification of 14th Plenum of 11th Central Committee].

48 Tuan Minh, “Vietnam works with Other Countries to save TPP: Spokesperson”.

49 Abe and Tomiyama, “China, Vietnam to cooperate on new trade corridor”.

50 Ca, “Quang ninh tu choi vay 7000 ty: Lo ngai nha thau Trung Quoc,” [Quang Ninh Provice refusing to borrơ 7000 bn: Concerns about Chinese sub-contractors]. t 2016.

51 Communist Party of Vietnam, “Resolution No. 10”.

Bibliography

- Abe, T., and A. Tomiyama. 2015. “China, Vietnam to Cooperate on New Trade Corridor.” Nikkei Asian Review, April 8. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/China-Vietnam-to-cooperate-on-new-trade-corridor.

- An, C. 2016. “Trien Vong Thuong Mai Viet Nam ‘Sang’ Chua Tung Co Voi 14 Hiep Dinh Thuong Mai Tu Do Sap Hoan Tat” [Prospect of Vietnam’s trade has never been bright with 14 FTAs in completion]. Cafef, February 2. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://cafef.vn/vi-mo-dau-tu/trien-vong-thuong-mai-viet-nam-sang-chua-tung-co-voi-14-hiep-dinh-thuong-mai-tu-do-sap-hoan-tat-20160201094551931.chn

- Bowring, G. 2014. “Vietnam Yields Cautionary Tale over Chinese Investment.” Financial Times, November 27. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/6ea71dd6-ccea-3779-87be-d4654fc9379b

- Bradsher, K. 2010. “Amid Tension, China Blocks Vital Exports to Japan.” The New York Times, September 22. Accessd May 8, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/24/business/global/24rare.html

- Ca, S. “Quang Ninh Tu Choi Vay 7000 Ty: Lo Ngai Nha Thau Trung Quoc” [Quang Ninh Provice refusing to borrow 7000 bn: Concerns about Chinese sub-contractors]. Bao Dat Viet [Viet Fartherland], August 8, 2016. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://datviet.trithuccuocsong.vn/chinh-tri-xa-hoi/tin-tuc-thoi-su/quang-ninh-tu-choi-vay-7000-ty-lo-ngai-nha-thau-tq-3315899/t

- Cheng, J. Y. S. “Sino-Vietnamese Relations in Early Twenty-first Century.” Asian Survey 51, no. 2 (2011): 379–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2011.51.2.379.

- “The China-Philippines Banana War.” The Asia Sentinel, June 6, 2012.

- Communist Party of Vietnam. “Resolution No. 10.” Central Committee. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://tulieuvankien.dangcongsan.vn/he-thong-van-ban/van-ban-cua-dang/nghi-quyet-so-10-nqtw-ngay-362017-hoi-nghi-lan-thu-nam-ban-chap-hanh-trung-uong-dang-khoa-xii-ve-phat-trien-kinh-te-tu-3222.

- Denyer, S. 2015. “China’s Assertiveness Pushes Vietnam toward an Old Foe, the United States.” The Washington Post, December 28. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/chinas-assertiveness-pushes-vietnam-toward-an-old-foe-the-united-states/2015/12/28/15392522-97aa-11e5-b499-76cbec161973_story.html

- Do, T. H. Vietnam and the South China Sea: Politics, Security and Legality. Routledge: Oxon, 2017.

- Gu, X., and B. Womack. “Border Cooperation between China and Vietnam in the 1990s.” Asian Survey 40, no. 6 (2000): 1042–1058. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3021201.

- Guan, A. G. “Vietnam-China Relations since the End of the Cold War.” Asian Survey 38, no. 12 (1998): 1122–1141. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2645825.

- Hayton, B. Vietnam and the United States: An Emerging Security Partnership. United States Studies Centre, November 2015.

- Hiep, L. H. “Vietnam: Under the Weight of China.” East Asia Forum, November 27, 2011. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/08/27/vietnam-under-the-weight-of-china/

- Hiep, L. H. “Vietnam’s Hedging Strategy against China since Normalization.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 35, no. 3 (2013): 333–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1355/cs35-3b.

- Hiep, L. H. Living Next to the Giant: The Political Economy of Vietnam’s Relations with China under Moi. ISEAS Publisher: Singapore, 2017.

- Lai, A. 2012. “‘One Party, Two Coalitions’ – China’s Factional Politics.” CNN, November 9.

- Mai, X. B. “Van De Tac-doi Tuong Trong Chien Luoc Bao Ve to Quoc” [Partners and object of struggle in the strategy to defend the country]. Tap chi Cong san [Communist Review], January 31, 2015. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/nghien-cu/-/2018/31758/van-de-doi-tac—doi-tuong-trong-chien-luoc-bao-ve-to-quoc.aspx

- Neack, L. The New Foreign Policy- Power Seeking in a Globalized Era. 2nd ed. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008.

- Nguyen, D. L. Quan He Viet-Trung Truoc Su Troi Day Cua Trung Quoc [Vietnam-china Relations at a Time of China’s Rise]. Tu Dien Bach Khoa Publisher: Hanoi, 2013.

- Nguyen, M. C. 2011 “Tai Sao Viet Nam Lai Nhap Sieu Manh Tu Trung Quoc” [Why Vietnam suffered huge deficit from China]. Dan Tri [People’s Knowledge], June 6. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://dantri.com.vn/kinh-doanh/tai-sao-viet-nam-lai-nhap-sieu-manh-tu-trung-quoc-1307662036.htm

- Nguyen, Q. H. 2014. “No than an Duong Vuong – Tu Huyen Thoai Den Su that Lich Su” [King An Duong’s magic crossbow – From Myth to Historical Reality], Vietnam National Museum of History, December 15. Accessed May 4, 2021. http://baotanglichsu.vn/vi/Articles/3096/17444/no-than-an-duong-vuong-tu-huyen-thoai-djen-su-that-lich-su.html

- “Nguyen Phu Lieu Det May: 48% Nhap Tu Trung Quoc” [Textile and garment industry materials: 48% imported from China]. Tuoi Tre [The Youth], April 3, 2015.

- “The Pact Is a Win for Prosperity and Peace.” Nikkei Asian Review, October 8, 2015.

- Pham, H. “20 Ty USD Tu Trung Quoc Vao Viet Nam Di Dau Mat?” [US$20bn from China to Vietnam: Where has it gone?] Vietnamnet, May 5, 2015. Accessed February 2, 2021. http://m.vietnamnet.vn/vn/kinh-doanh/234657/20-ty-usd-tu-trung-quoc-vao-viet-nam-di-dau-mat.html.

- Phan, K. N. “Dac Trung Cua Thuong Mai Trung-Viet Va Phan Tich Nguyen Nhan Cua No” [Characteristics of Vietnam-China trade relations and its reasons]. Vietnam Institute of China Studies, September 8 (2010). Accessed May 12, 2021. http://vnics.org.vn/Default.aspx?ctl=Article&aID=201

- Storey, I. “Vietnam and the United States 2004–2005: Still Sensitive, but Moving Forward.” APCSS Special Assessment, February 2005.

- Thayer, C. A. Coping with China, 351–367. Singapore: Southeast Asian Affairs, 1994.

- Thayer, C. A. “Upholding State Sovereignty through Global Integration: Remaking of the Vietnamese National Security Policy.” Paper presented at the Workshop on Vietnam, East Asia and Beyond, Hong Kong, December 11–12, 2008.

- Thayer, C. A. “Vietnamese Diplomacy, 1975-2015: From Member of the Socialist Camp to Proactive International Integration.” paper presented at the International Conference on Vietnam: 40 Years of Reunification, Development, and Integration (1975-2015), Thu Dau Mot University, Binh Duong, April 25, 2015.

- “Thong Bao Hoi Nghi Lan Thu 14 Ban Chap Hanh Trung Uong Dang Khoa XI” [Notification of 14th Plenum of 11th Central Committee]. Nhan Dan [The People Daily], January 13, 2016.

- Tran, T. Q. “Quan He Vietnam Va Trung Quoc: Nhin Lai Và Huong Toi” [Vietnam-China relations: Review and a look forward]. Tap Chi Cong san [Communist Review], October 8, 2011. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/hoat-ong-cua-lanh-ao-ang-nha-nuoc/-/2018/13168/quan-he-viet-nam-%E2%80%93-trung-quoc–nhin-lai-va-di-toi.aspx

- Tran, V. T. “Viet Nam 40 Nam Qua Va Nhung Nam Toi: Can Mot Nen Kinh Te Thi Truong Dinh Huong Phat Trien” [Vietnam in last 40 years and years to come: In need of a development-oriented market economy]. Thoi Dai Moi [New Era], No.33 (July 2015): 13–64.

- Tuan, M. 2017. “Vietnam Works with Other Countries to Save TPP: Spokesperson.” Bizlive, February 10. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://nhipsongdoanhnghiep.cuocsongantoan.vn/biznews/vietnam-works-with-other-countries-to-save-tpp-spokesperson-2455773.html?allowmobile=true&trang=3

- US Embassy in Hanoi. “ASEAN Partnership, Human Rights Dialogue, Embassy Compound Discussed with Assistant Foreign Minister.” Cable (released by Wikileaks), Accessed October 27, 2005. http://wikileaks.org/cable/2005/10/05HANOI2857.html

- “Possible Impacts of TPP on Vietnam.” The Saigon Times, October 12, 2015

- Vu, T. M., and T. T. Nguyen. “The 2014 Oil Rig Crisis and Its Implications for Vietnam-China Relations.” In Vietnam’s Foreign Policy under Moi, edited by L. H. Hiep and A. Tsvetov, 72–95. Singapore: ISEAS Publisher, 2018.

- Vuving, A. “Strategy and Evolution of Vietnam’s China Policy: A Changing Mixture of Pathways.” Asian Survey 46, no. 6 (2006): 805–824. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2006.46.6.805.

- Vuving, A. Vietnam: A Tale of Four Players, 367–391. Singapore: Southeast Asian Affairs, 2010.

- Waltz, K. Theory of International Politics. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979.

- Womack, B. “Sino-Vietnamese Border Trade: The Edge of Normalization.” Asian Survey 34, no. 6 (1994): ?–?. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2645337.

- Womack, B. China and Vietnam: Politics of Asymmetry. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2016.

- Yang, A. H. “China-Vietnam Relational Asymmetries.” In Power in a Changing World Economy: Lessons from East Asia, edited by J. C. Benjamin and E. M. P. Chiu, 125–143. London: Routledge, 2014.