ABSTRACT

This study investigates the relationship between the socialist industrialization of pastoralism in Mongolia and the government’s perception of severe winter disasters (dzud), as well as the countermeasures taken against them. It aims to do so by focusing on pastoral production and dzud’s impact under pastoral cooperatives (negdel). During the collective period from the late 1950s to the early 1990s, the government regarded dzud as the greatest threat to the livestock sector and explored ways to prevent and mitigate the ensuing damage. In theory, public regulation and support for dzud prevention and mitigation could decrease the frequency and severity of a large-scale dzud that may affect the entire country. However, dzud occurred occasionally at the province (aimag) or district (sum) level and had a serious impact on pastoral production in rural areas. In addition to the positive aspects of local society and larger structures, such as rescue and recovery, there was also a negative side to the industrialization of pastoralism, such as decreased resilience to dzud damage. Along with the expansion of pastoral production for domestic and foreign urban consumers, the consistent demand for individuals and pastoral cooperatives to achieve strict production quotas, regardless of any conditions, has exacerbated the damage from dzud. That is, the slump in rural pastoral production during the collective period may have been caused by the interaction between the damage from dzud and the problems concerning the labor production system that was revised in response to the challenges of industrialization under pastoral cooperatives.

1. Introduction

The well-known Japanese phrase “disasters strike when people lose memory of the previous one” shows that people are quick to forget past disastersFootnote1. This only means that humans are forgetful creatures. The timeframes in which natural processes unfold vary considerably from those in which human decision-making takes place. Humans can adapt socially and culturally to their environment through considerable trial and error. Thus, Mongolian pastoralists have developed the knowledge, techniques, customs, and institutions to survive the extreme natural environment, characterized by a dry and cold climate, through trial and error.

To put it simply, the water and material cycle in the Mongolian grassland is understood as annual and seasonal fluctuations of precipitation and temperature that are concurrent with the fluctuations of soil moisture and vegetation conditions that affect the growth of livestock. This, in turn, affects humansFootnote2. Mongolian pastoralists have adapted to the uncertain climate and environmental conditions by creating a highly mobile subsistence and lifestyle. However, socio-economic changes such as demographics (population increase, population concentration in urban areas), the commercialization of agricultural and livestock products, the transformation of natural resource use and the management system have had a great influence on the interrelationship between land, livestock, and people, due to the urban and industrial developments that began in the mid-20th century. This study aims to investigate how these socio-economic changes that occurred in the process of the socialist modernization have proven to be beneficial and/or detrimental to the pre-modern relationship between land, livestock, and people. It will do so by focusing on the interaction between pastoral development and natural disasters in the socialist era, especially in the collective period. The collective period here refers to a period of 30 years from approximately the late 1950s, when pastoral cooperatives (negdel) and state farms (sangiin aj akhui) were established nationwide, to the early 1990s, when they were dismantled.

At the end of the 19th century, Mongolia was already exporting large amounts of livestock to ChinaFootnote3. In the early 1940s, during World War II and corresponding to the socialist era, meat (live animals), fur, leather, and butter began to be procured by the state. These livestock products then began to be produced as food and industrial materials for domestic and foreign urban populations. After the collectivization of agriculture and pastoralism in the late 1950s, pastoral cooperatives engaged mainly in pastoral production, while state farms engaged in grain and vegetable production, and stock farming, which were heavily dependent on fodder and corrals. Following World War II, Mongolia’s population increased rapidly, especially in urban areas. Urban dwellers accounted for only 21.6% of the total population in 1956. However, the urban population exceeded the rural population in the late 1970s and reached 57% of the total population in 1989Footnote4. In addition to the increased mouths to feed in the country, the export of livestock products and goods manufactured from them steadily increased in order to carry out Mongolia’s role in the socialist division of labor since joining the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in 1962. Those exports accounted for 82.9% of the total exports in 1977Footnote5. In the mid-1980s, stagnant production forced Mongolia to limit the export of raw livestock materials in order to meet the rapidly increasing demand for meat and dairy products resulted from the growth of the domestic urban population. The rapid increase in the procurement and export of livestock products during and after World War II, especially during the collective period, likely led to a historic maximization of pastoral production for the domestic and foreign urban populationsFootnote6. First, it should be emphasized that pastoral production, a major industry in Mongolia, played a dominant role in exports to the Soviet Union and other socialist countries, as well as ensuring that there was adequate domestic food supply. Second, this industrialization of pastoralism had a great impact not only on livestock raising and livestock product use, but also on the relationship between people and the environment, including natural hazardsFootnote7.

Dzud is a Mongolian term indicating harsh winter conditions (e.g., deep snow and severe cold) that result in an increase in livestock mortality. Mongolia is characterized by a harsh environment with a cold and arid climate. The combination of summer droughts and dzud in the winter is believed to lead to a massive reduction in the number of livestock. Since the mid-20th century, dzud became a quantitatively and qualitatively measurable “natural disaster,” produced by the interaction of social and natural forcesFootnote8. Mongolian pastoralists attempted to reduce dzud risks and mitigate its impact by flexibly using migration and settlement. However, contrary to expectations, dzud occurred during the collective period as well.

In Mongolia, the results of climate change, such as warming and drying, have gradually emerged over the past 60 yearsFootnote9. Dzud has already increased in frequency since the 1950s, a period which corresponds to the beginning of collectivized agriculture in MongoliaFootnote10. Public regulation and support for dzud prevention and mitigation could decrease the frequency of a large-scale dzud affecting the entire country. However, from a regional point of view, dzud occurs occasionally at the province (aimag) or district (sum) level and has a serious impact on the pastoral production in rural areas. Although some previous studies on dzud reported their occurrence and severity during the collective period, most only referred to them as data to show that the frequency of destructive dzud increased after the collapse of agricultural collectivesFootnote11. Meanwhile, limited research has explored the environmental and socio-economic changes or events of the socialist era.

Few studies have investigated how states, local governments, and herder households have understood and responded to dzud under the collective regimeFootnote12. The collectivization in the late 1950s caused a decline in a range of seasonal movements within districts or subdistricts, which were territories that corresponded to pastoral cooperatives. Instead, a complete land-use system within each district’s territory (pastoral cooperative) was formedFootnote13. In order to cope with the risks of environmental changes and anthropogenic influences, pastoral cooperatives encouraged herders to move more frequently and use limited resources efficiently. This was based on the strategy of mainly sedentarizing, such as introducing reproductive management, winter shelters, wells, and fodder use. Pastoral cooperatives also enabled cross-boundary movement from the affected areas to other areas in case of dzud or droughtFootnote14.

Previous studies on today’s dzud have also regarded governmental control and support for reducing dzud risks, including cross-boundary movement, fodder preparation, livestock care, and management during the collective period, to have contributed to the prevention and mitigation of damage from drought and dzudFootnote15. However, it is difficult to judge the socialist industrialization as enabling people to cooperate and overcome the hazards of drought and dzud through solely examining one perspective. Due to the fact that excessive livestock procurement aggravated and prolonged the impact of dzud on rural pastoral production, this matter will be discussed more in depth in upcoming sections.

This paper aims to describe the relationship between the socialist industrialization of pastoralism in Mongolia and the growing demand for livestock products as food and industrial materials since the mid-20th century. It also aims to analyze the government’s perception of dzud and the countermeasures taken against it, by focusing on pastoral production and dzud’s impact under pastoral cooperatives. In addition, this paper intends to explore the influences of socio-economic and environmental changes since the mid-20th century on traditional human–environmental relations. The objectives of this paper are threefold. First, it provides an overview of the characteristics of dzud and drought in Mongolian pastoral society. Second, it examines the actual conditions of dzud and their impact on state policy during the collective period by focusing on the 1967–1968 dzud, which was one of the turning points in establishing a framework for dzud recognition and response that is still in place. Finally, it explores the production, distribution, and sale of livestock products (especially meat) and dzud damage, including its impact on the former under pastoral cooperatives through an analysis of both document and field data. This study examines the positive and negative aspects of the struggles against dzud in the socialist era, which are closely related to the recognition of and countermeasures against dzud in present-day Mongolia.

2. Defining dzud for Mongolian pastoralists

2.1. Cold and dry environment and pastoralism in Mongolia

Grasslands (steppes) are widely distributed in the mid-latitudinal regions of Eurasia. It is difficult to grow grains and vegetables in such arid and semi-arid lands. Thus, people have raised multiple species of gregarious ungulates, including sheep, goats, cattle (yak), horses, and camels, and have used them for food (meat, dairy products), living materials, fuel, riding, and transportation.

In Mongolia, located at the eastern end of the Eurasian Steppe, the seasonal characteristics of the warm-wet and cold-dry alternating yearly cycles are closely related to the pastoral system. Mongolia has a dry continental climate, which is typically characterized by a wide temperature range, low precipitation, and low humidity. However, most of the annual precipitation (258.5 mm) is concentrated in the short period from April to September, and thus, livestock increase in weight by grazing on rich pastures from spring to autumn. Subsequently, from winter to spring, they gradually lose weight and energy reserves because of the low temperature and drying vegetationFootnote16. Therefore, the key strategy of Mongolian pastoralists is to build up livestock during the warm season and protect them from the harsh winter climate during the cold season. However, in Mongolia, the annual precipitation and temperature fluctuate even in the same area. Consequently, herders sometimes cannot raise livestock as planned. Dzud and drought are the most significant determinants.

Anomalous climatic conditions such as deep snow, severe cold, and storms lead to reduced accessibility and availability of pastures. Ultimately, they lead to significant livestock mortality during winter and springFootnote17. Livestock are most vulnerable to these climate changes particularly during spring, when their physical strength and weight are at the lowest. These climatic conditions are the first causes of dzud. Socio-economic factors, such as overgrazing, poor pasture management, and lack of preparation for the winter also affect the existence and extent of dzud damage. There are various types of dzud that result from combinations of snow/ice cover, lack of pasture, and stormy weatherFootnote18. White dzud involves deep snow covering the grass, while black dzud refers to shortage of drinking water for livestock due to lack of snow. Hoofed dzud occurs when too many heads of livestock are in a single location with sparse grasses.

Droughts, which are caused by high temperatures and little rainfall during the summer, reduce pasture production and limit livestock growth. Although droughts result in little livestock mortality in the growing season alone, they exacerbate the influence of severe winter conditions. However, Sternberg casts doubt on a drought–dzud linkage based on an investigation of causality between the two in Mongolia, pointing out that the link between drought and other events needs to be identified at a more local scaleFootnote19.

2.2. Recurring dzud damage

Dzud have caused serious damage to Mongolian pastoralists. Harayama found descriptions of heavy snow resembling dzud in history and travel literature. For example, Yuanshi, an official Chinese historical work, describes how many people suffered from famine because 90% of their livestock was lost due to heavy snow during the winter of 1335Footnote20.

Even today, dzud is a fundamental issue affecting the fate of pastoral production in Mongolia. Komiyama identified the years when major dzud occurred by referencing related domestic reports and literature: 1945, 1968, 1977, 2000, 2001, and 2002Footnote21. Furthermore, Komiyama later revised the major dzud years based on the criterion of the mortality rate of adult livestock exceeding 10% in 1943, 1945, 1950, 1968, 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2010Footnote22. Considering the fact that the number of major dzud that have occurred since 1992 has already reached the number of such events between 1940 and 1991, it can be argued that large-scale dzud occurred more frequently following Mongolia’s transition from socialism to capitalism.

However, this does not necessarily mean that the impact of dzud was relatively minor during the socialist era. In particular, the 1944–1945 dzud killed 8.08 million livestock (33.2% of the national herd), the highest herd mortality rate in Mongolia since recordkeeping beganFootnote23. On the other hand, this paper focuses on the 1967–1968 dzud, despite the fact that the number of livestock deaths (2.66 million) is less than half than that of the 1944–1945 dzud. The problem lies not only in the extent of the dzud damage, but also in the period of the 1960s, when the dzud occurred. At that time, the Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR) had just implemented its fourth Five-Year Plan (1966–1970) with the slogan “accomplish socialism,” which attempted to create more extensive and mechanized agricultural production. This was brought on by the necessity of feeding urban populations, which had dramatically increased in tandem with improvements to infrastructure and industrial development in Ulaanbaatar and secondary cities since the end of World War II. Furthermore, after Mongolia joined the CMEA in 1962, the demand for livestock products as food and raw industrial materials increased within and outside the MPRFootnote24. In such a situation, the 1967–1968 dzud might have had a great impact on both the state and the individual. What did the dzud of the 1960s, which peaked between 1967–1968, mean for individuals and for large-scale state policy? How did dzud affect the social and economic development of the MPR? Before examining dzud damage and its influences during the collective period, this paper briefly reviews the countermeasures undertaken against drought and dzud at that time.

2.3. Efforts for dzud prevention and mitigation under the collective regime

Three countermeasures against dzud under the collective regime were introduced: (1) building disaster prevention infrastructure, such as the construction of shelters, the excavation of wells, and the compilation of forage stock; (2) advertising through mass media, such as newspapers and radio; and (3) developing a verification system based on scientific data.

In Mongolia, roofed wooden shelters have been constructed in campsites in winter and spring since the 1940s, in order to protect livestock from severe winter conditionsFootnote25. By the collective period, winter shelters were already widespread nationwide, and the government had taken on the challenge to improve shelter quality and increase their numbers. The excavation of wells around winter campsites meant that there were not enough watering places aimed at preventing the exhaustion of livestock from a lack of water due to little snowfall. This fixed pastoral land used during cold periods was supported by hay and fodder stocking, which was based on annual plans that met the demands of each province and district. It was also supported by the nationwide fodder supply from the northern region, as well as the abundance of grass in the southern regionFootnote26. Regarding fodder use, wheat bran has been widely used as fodder since the introduction and expansion of crop cultivationFootnote27. In this way, the material basis for the prevention and mitigation of damage from severe environmental conditions developed rapidly.

Meanwhile, government measures, rules, knowledge, and skills designed to prevent and mitigate dzud damage were conveyed to people through mass media, such as pamphlets, newspapers, radio, and movies. Spokespersons dispatched from the center of provinces and districts to rural areas held seminars for herders on how to deal with severe winter conditions. They explained the cautious measures required to protect livestock during the cold period and gave helpful examples of advanced initiatives in other regions (e.g., feeding and watering livestock, utilizing dead livestock products). Moreover, real-time information on pastoral production and advanced initiatives across the state were also introduced in Unen, a newspaper published by the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party. At the time of the 1967–1968 dzud, the paper contained sensational headlines, such as “Much Remains to Be Done for the Complete Overwinter,” or “Now is the Time to Protect Babies in the Wombs of Livestock” ().

The mechanisms and influence of droughts and dzud were verified based on scientific data. The number of meteorological observation points increased significantly in order to record precipitation, temperature, and vegetation at the level of each district. In 1966, the Institution of Meteorology and Hydrology, which adopted standard methods of observation, forecasting, and warning for droughts and dzud, was established with the assistance of the Soviet UnionFootnote28. In addition, livestock statistics were refined to record the details of births and deaths at the district level (pastoral cooperatives), and to understand the actual conditions of dzud and its influence on pastoral production in local society.

As mentioned above, countermeasures against dzud were established under the collective regime. Although physical and institutional support from the government and agricultural collectives contributed to the decreasing frequency and severity of dzud, socialist Mongolia could not eradicate the damage from severe winter weather conditions, despite these efforts. At the regional level, dzud continued to occur and occasionally caused serious damage to livestock and people’s livelihoods during the collective periodFootnote29. Accordingly, this study examines what dzud meant for the people living in rural areas, through the industrialization of pastoralism undertaken during the collective period.

3. Methods and study sites

Little research has been conducted on dzud in socialist Mongolia, except for domestic research conducted by public research organizations such as the government and universities at that time. The lack of research, as well as the restrictions on research materials, have made it difficult to study dzud in socialist Mongolia. Dzud and droughts occur more frequently than earthquakes in Mongolia and repeatedly cause damageFootnote30; thus, they have become commonplace. There is no fundamental difference between the death of livestock in dzud, and that in every winter and spring, making it difficult to determine the extent of dzud. Therefore, the year when major dzud occur varies significantly among the international and domestic reportsFootnote31. Furthermore, the fact that not all communities experience dzud in the same way or to the same extent makes it challenging to examine the damage to rural areas.

Accordingly, this study examines dzud damage and its influence during the collective period from both local and national perspectives, based on administrative documents and local statistics in the national archives of Mongolia and the Bulgan provincial archives. It is also based on interviews of former members of pastoral cooperatives within the research areas. The following section describes the characteristics of dzud as natural disasters, built under the state’s initiative, and countermeasures against them. A particular challenge of this study is to conduct a statistical analysis based on local livestock statistics (malin “A” dans) in order to clarify pastoral production and the damage inflicted by dzud in each pastoral cooperative. When pastoral production in rural areas was collectivized in the late 1950s, the territories of pastoral cooperatives and those of sub-organizational units called brigad were made to correspond to those of districts (sum) and sub-districts (bag) in order to promote the integration of the administrative and economic system. At the same time, most of the livestock privately owned by herders were transferred to the collective property of each pastoral cooperative, and only a few livestock remained in their handsFootnote32. As a result, pastoral production in rural areas was conducted based on each pastoral cooperative and this sub-organizational units. Since the 1960s until today, human and livestock population surveys have been conducted once a year in each district and sub-district, which corresponded to pastoral cooperatives or state farms. These local livestock statistics contain both static data, including species, sex, age, and mating status of livestock owned by public agencies and individuals, as well as dynamic data, including birth, death, national procurement, and local consumption of livestock.

This analysis based on each district/pastoral cooperative may reveal dzud’s influences on local pastoral production and is a convincing argument. However, caution should also be exercised in terms of the accuracy and credibility of these local statistics. A method of examining the information gathered through statistical analysis in combination with interviews with former members of pastoral cooperatives was adopted.

Although the total number of dzud that occurred after 1967–1968 and until agricultural collectives were dismantled in 1991 is unknown, the years when the death rate (DR) of livestock (number of deaths/previous year’s total livestock × 100) exceeded 10% can be regarded as those when dzud occurred – in 1972, 1976, 1977, 1980, 1983, 1984, and 1985Footnote33. The DR of livestock in the winter of 1976–1977 was the highest (17%). Thus, the 1976–1977 dzud can be considered a national-scale dzud. In 1976–1977, a large number of livestock died in the central region, including Tov, Dundgovi, Bulgan, and Arkhangai. Bulgan province, which experienced a large-scale dzud for the second straight year, lost 142,000 livestock (14% of its provincial herds) from 1975 to 1977Footnote34. In this study, a case study of dzud damage and its influence on raising and using livestock in the pastoral cooperatives of Bulgan is discussed. Bulgan was extensively damaged from the 1967–1968 and the 1976–1977 dzud. The Buregkhangai district was particularly selected because it was relatively less affected by the reorganization of local administrative units, and many documents remained at the study sites (). In the following section, the implications for state policy of the dzud of the 1960s, which peaked in 1967–1968, are considered.

4. Results

4.1. The modern conception of the dzud and overcoming it

After the collectivization of pastoralism, the demand for livestock products as food and raw industrial materials increased within and outside Mongolia, while the large and small-scale dzud that occurred successively in the 1960s were regarded as major barriers to economic growth. According to a study by ChoijirjavFootnote35, the MPR conducted the first detailed examination of dzud at various places nationwide during the winter of 1963–1964. A major issue that emerged from this investigation was that there were no national guidelines on how to distinguish the characteristics of dzud. Therefore, from 1966 to 1967, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Department of Meteorology and Hydrology took the initiative to develop criteria for distinguishing dzud, which were established in January 1968. The report of the State Commission on the 1967–1968 dzud appointed by the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party’s Central Committee (hereafter, “the Report”) states that a specialist team dispatched by this commission conducted the first national survey of dzud damage based on the criteria, although its details are unknown.

According to the Report, the 1967–1968 dzud caused mass deaths of livestock and had a serious impact on not only pastoral production, but also people’s livelihoods in most regions of the MPR (13 of 18 provinces at that time). The western and southern regions of Zabkhan, Govi-Altai, Bayankhongor, Ovorkhangai, and Omnogovi, were the most affected by the 1967–1968 dzud. The drought of 1967, which resulted in the reduction of rainfall by half during the spring and summer, compounded the damage from the severe winter conditions, such as heavy snow and cold temperatures.

The state commission on the 1967–1968 dzud estimated that 3.22 million heads of livestock died from November 1967 to May 1968. The most prevalent cause of death was starvation (45%), followed by severe cold (28.6%). Other causes included a lack of water, infectious diseases, and improper feeding. The breakdown of livestock deaths was 0.81 million adults (2 years old or older), 0.91 million offspring (1 year old, born in the spring of 1967), and 1.5 million new-borns (0-year-old, born in the spring of 1968). Thus, the vulnerability to dzud, or how much one is likely to be affected by natural hazards, of immature livestock ranging from 0 to 1 year old is relatively high. Livestock deaths due to the 1967–1968 dzud were concentrated on both pastoral cooperatives (88.9%) and individuals who raised private livestock for self-sufficiency (10.1%). There was little damage to stock farming, both for state farms (0.5%) and for agricultural machinery stations (0.2%)Footnote36.

It should be noted that the Report emphasized not only meteorological conditions, but also human errors as causes of the destructive dzud, such as insufficient preparation for the winter and spring. While the Report appreciated that the collectivization of agriculture, and pastoralism enabled the mitigation of damage from severe winter conditions, it also criticized the insufficient preparation for winter periods, including fattening, fodder stock, and construction of winter shelters. This lack of preparation increased dzud damage in the most affected provinces. A similar contention is found in the book Problems Concerning the Dzud: Learning from the Experience of Herders, published in 1969, as follows:

The traditional image of dzud as the wrath of gods beyond human reach is becoming old-fashioned, and now we understand that dzud is closely related to natural hazards (baigaliin bersheel) and economic preparation.

Dzud does not only refer to severe winter conditions such as heavy/light snowfall, low temperature, and stormy weather. Dzud indicates that these natural hazards caused mass deaths of livestock and damage to peoples’ livelihoods because of insufficient preparation for them. […]

Dzud does not need to occur. It will disappear when physical and mental preparation are accomplishedFootnote37.

What is worth noting here is that natural hazards and disasters (damage to livestock and people’s livelihoods) are distinguished, and dzud is understood in the latter senseFootnote38. Furthermore, dzud as “the natural disaster” is caused not only by environmental factors, but also by socio-economic factors, with the latter having been deemed more crucial. Thus, it has been established that the damage caused by dzud must be eradicated through the implementation of scientifically correct measures to protect livestock from severe winter conditions. The idea that natural hazards can be overcome by human efforts overlaps with the view on nature in the Soviet Union and in China after World War IIFootnote39. As the domestic and international demand for livestock and livestock products has progressively increased, dzud damage has become a serious problem not only for individuals and pastoral cooperatives, but also for the state, as well as other socialist countries. Subsequently, the influence of dzud on the pastoral production under the collective regime through the local statistical analysis will be examined.

4.2. The production and reproduction of livestock

4.2.1. Overview of pastoral production in rural areas

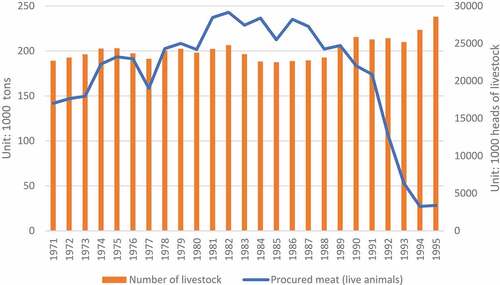

Since joining the CMEA in 1962, the MPR expanded exports of livestock products as food and raw industrial materials to the Soviet Union and other socialist countries. In the socialist division of labor, Mongolia was responsible for exporting raw materials and products made from livestock products – mainly meat, fur, and leather. Furthermore, the domestic demand for meat and dairy products in Mongolia increased due to the rapid increase in the urban population caused by the construction of infrastructure and industrial development in Ulaanbaatar and secondary cities. Along these lines, meat production in rural areas has had to address two challenges: exports, and domestic food supply. illustrates the total number of national herds and the amount of meat (live animals) procured by the state from 1971 to 1995. According to this figure, the amount of meat procured by the state peaked in the early 1980s, but then declined, with the tendency to increase during the collective period. Meanwhile, the total number of animals in the national herd was almost stagnant or slightly decreased in the 1980s. In other words, while the growth of the total number of livestock was sluggish, the state implemented excessive procurement of livestock. The rapid expansion of pastoral production took a heavy toll on herders. While the government strengthened the labor and work discipline in pastoral cooperatives, it also imposed restrictions on individual households’ raising livestock for self-consumption, such as tightening restrictions on the number of private livestock owned or by procuring livestock products from them.

How much livestock products did each pastoral cooperative produce in a year? shows the value of livestock products in 1983, in 11 districts of the Bulgan Province which were pastoral cooperatives. In all districts, meat (live animals) sales accounted for most of the income from livestock products. In particular, the sales of sheep and cattle were large. This reflects pastoral policies since the third Five-Year Plan (1961–1965) focused on increasing sheep and cattle. Although horses, in particular castrated males, were also procured for meat, they were mainly used for riding and transportationFootnote40. Wool and cashmere were mostly sold as fur, while raw milk, butter, and casein were sold as dairy products. As mentioned above, although various livestock products such as meat, fur, leather, and dairy products were produced in each district/pastoral cooperative, the main income source was the sale of meat (live animals).

Table 1. Sales amount of livestock products in pastoral cooperatives of Bulgan province in 1983unit: MNT

4.2.2. The production and reproduction of livestock

This section discusses dzud damage and its influence on raising and using livestock in the pastoral cooperative based on the study site. The cycle of reproduction and growth of sheep, goats, and cattle, which were the main sources of meat (live animals), is briefly examined. Furthermore, its relationship with national procurement and local consumption will also be explored.

Female sheep and goats usually give birth in spring when they are 2 years old. Female cattle first experience calving at the age of 3. While females were kept for the purpose of reproduction, young males, except for a few sires, were mostly procured for the state and local areas. The average age of the national procurement of sheep and goats was 1 year old (born in the previous year), and that of cattle was 2 years old (born two years previous). According to Bazarsad, a veterinarian in the pastoral cooperative, sheep, goats and cattle could be fattened for another year. However, the procurement of young livestock that have room to grow became institutionalized in order to achieve quotas for meat, as well as to cut labor costs during the collective period. After procuring livestock throughout each district in the early summer (mid-May), several groups consisting of young men transported herds to the food complex in Ulaanbaatar and other secondary cities for growing and fattening for approximately half a year. According to Poloo, who engaged in raising sheep and goats in pastoral cooperatives, livestock consumed within local areas included aged females whose fertility or teeth had declined, as well as the sick and injured ones that were not expected to grow any further. Nevertheless, the exact details of these practices are unknown. Accordingly, with the expanding international and domestic food demand, male sheep, goats, and cattle were commercialized as the main targets of national procurement, with a decrease in the slaughter age. A large number of females were kept in order to expand the means of reproduction of the herd.

4.2.3. The death rate and birth rate of livestock when the dzud occurred

What kind of impact did dzud have on pastoral production in rural areas? From 1952 to 1985, the DR in Bulgan exceeded 15% only twice, once in 1968 and then in 1977. This a more substantial rate than the criteria previously mentioned. Thus, it is thought that the impact of the national-scale dzud events of 1967–1968 and 1976–1977 were particularly severe. However, not all districts in the region experienced dzud in the same way or to the same extent. Even in the 1976–1977 dzud, which had the highest DR of livestock during that period, the number of livestock increased in 4 out of 16 districts in the Bulgan province. Although a 2009–2010 study reported that damage to livestock also varied among neighboring districtsFootnote41, the same tendency was found among other pastoral cooperatives with similar institutions and countermeasures against dzud.

Looking at the DR of livestock based on species, the DR of small livestock (bog), such as sheep and goats, is high, and the DR of large livestock (bod), such as cattle and horses, is relatively lowFootnote42. When comparing the DR in the dzud events of 1967–1968 and 1976–1977 with the average DR between 1952 and 1985, cattle were found to be more vulnerable to dzud than horses (). Furthermore, the majority of dead livestock were immature young livestock that were 0–1 year old. In 1976–1977, 0–1 year old livestock accounted for 71.9% of the overall death of livestock, totaling 182,710 in Bulgan. This feature of vulnerability to dzud of immature young livestock was also seen in the 1967–1968 dzudFootnote43.

Table 2. Death rate of livestock in Bulgan province.

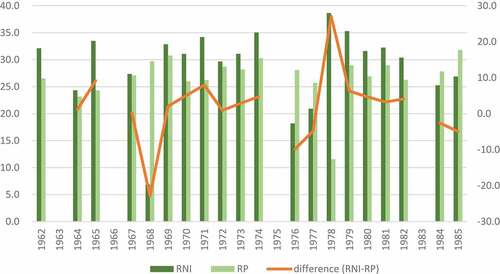

Dzud affects not only livestock mortality but also livestock fertility. Severe winter conditions, such as heavy snow and low temperatures, increase the risk of infertility and miscarriage. The birthrate (BR) of livestock (number of births/previous year’s total livestock × 100) may also decline below that of normal years. When dzud occurred, the rate of natural increase (RNI) of livestock (BR–DR) declined significantly. Although there were a few cases in which the RNI dropped below zero, it is thought that the most affected districts (pastoral cooperatives) had difficulty providing livestock.

4.2.4. The dzud damage and procurement of livestock

During times of dzud, the livestock procurement quota became a heavy burden for affected areas because the RNI declinedFootnote44. For example, in the dzud events of 1967–1968 and 1976–1977, Buregkhangai experienced an average rate of national/local procurement (RP) of livestock (number of livestock procured for the state and local areas in a year/previous year’s livestock × 100) exceeding the RNI by 22.9% and 4.8%, respectively (). This indicates that pastoral cooperatives implemented severe livestock procurement measures that, in turn, could have reduced livestock population growth. Similar issues were mentioned in the Report on the 1967–1968 dzud. The report assumed that the long-term decline in pastoral productivity was unavoidable because dams and immature young livestock had to be given up due to the shortfall in livestock procurement during that year. On the other hand, it should be noted here that the livestock procurement quota was reduced the following year in order to restore the decrease in 1976–1977. The livestock procurement quota was reduced to less than half the average in Buregkhangai. However, subsequent livestock procurement was carried out on a scale larger than 25% of the previous year’s total livestock. For unknown reasons, in Buregkhangai, livestock were procured in 1984 and 1985 on a scale that exceeded the natural rate of increase (). Although small, fast-growing livestock accounted for most of the dead livestock, it remains questionable whether the measures were adequate to restore the dzud damage to livestock. While the MPR had been struggling against dzud as a natural disaster since the 1960s, dzud damage to rural pastoral production became more serious because of excessive livestock procurement.

5. Discussion and conclusions

5.1. Socio-economic changes and disaster response in Mongolia in the mid-20th century

As Oliver-Smith and Hoffman explain: “Disaster exposes the way in which people construct or frame their peril, the way they perceive their environment and their subsistence, and the way they invent explanation, constitute their morality, and project their continuity and promise into the future.”Footnote45 Mongolian pastoralists have developed the knowledge, techniques, customs, and institutions to survive the extreme natural environment characterized by a dry and cold climate through trial and error. The MPR expanded exports of livestock products as food and raw industrial materials to the Soviet Union and other socialist countries during the collective period. Furthermore, the domestic demand for meat and dairy products in Mongolia increased due to the rapid increase in the urban population in Ulaanbaatar and secondary cities. With the circumstances surrounding rural pastoral production becoming more critical, the government came to regard dzud as the greatest threat to the livestock sector and explored ways to prevent and mitigate its damage. In Mongolia, during the collective period, the environmental and anthropogenic factors of dzud were identified, and the latter were emphasized. From an official point of view, dzud damage to livestock and human lives was not necessarily unavoidable. It was believed that the negative effects of natural hazards could be mitigated or eliminated through human effort, and people were also required to think and act along these lines. While Templer et al. presented the view that the loss of animals resulting from extreme winter conditions was insured by the state livestock insuranceFootnote46, Nakamura pointed out that there is a case in which herders were made to shoulder the responsibility for losses from dzudFootnote47. The idea that nature was plastic and capable of being dominated by human reason was inextricably linked to the notion of development to maximize agricultural and pastoral production through the efficient and effective use of the natural environment. It could be said that the influence of the natural environment on human society was considered less serious.

5.2. Dzud as a complex socioecological phenomenon

Have agricultural collectives succeeded in mitigating damage from dzud? The answer is both yes and no. Pastoral cooperatives could have decreased the occurrence of destructive dzud affecting the entire country twice, both in 1967–1968 and 1976–1977, by taking physically and institutionally effective countermeasures. Shinoda and Morinaga reported that the number of livestock deaths was relatively low in the 1967–1968 and 1976–1977 dzud, which were more severe than the 2000–2001 dzud in terms of climate conditions, with sufficient hay and fodder availableFootnote48. However, it was impossible to completely eradicate the damage caused by dzud. Dzud occurred occasionally at the province or district level and had a serious impact on pastoral production in rural areas. The government criticized the delay in production and livestock deaths caused by severe winter conditions, such as the fault and negligence of local governments and agricultural collectivesFootnote49. Through statistical analysis, it was found that dzud occurred periodically and caused enormous damage in Bulgan. When dzud occurred, the RNI of livestock declined as the DR of livestock increased, especially in immature young sheep, goats, and cattle. A lower BR of livestock was also observed.

Concurrently, focusing on the relationship between the dzud damage and livestock procurement reveals not only the positives for local society and larger structures, such as rescue and recovery, but also a negative side, such as decreased resilience to dzud damage. As non-pastoralist populations and urbanization progressed, young male sheep, goats, and cattle were mainly procured for urban consumers, while females accounted for the large majority of total livestock in order to expand the herd’s reproduction capacity. Although it was believed that Mongolia had a relatively higher proportion of castrated males in comparison to other pastoral societiesFootnote50, there was almost no room for keeping redundant castrated males in rural pastoral production during the collective period. Pastoral cooperatives’ herd composition, which was largely comprised of adult females and immature livestock, led to a significant decrease in the RNI (increase in death rate of livestock and in the risk of infertility and miscarriage) when dzud occurred. Furthermore, young females intended for breeding were procured in order to compensate for the lack of castrated males during recovery from dzud damage. This excessive livestock procurement prolonged the impact of dzud and contributed to the plateau or decrease in the number of livestockFootnote51.

Recent studies on the destructive dzud events from 1999 to 2002 and in 2009–2010 have examined the mechanisms behind droughts and dzud, herders’ vulnerability, and governmental responses, through collaborations across different research fields, such as climatology, ecology, and cultural anthropologyFootnote52. Dzud has thus been found to be a complex socio-ecological phenomenonFootnote53. The vulnerability of Mongolian pastoralists to dzud is attributed both to global warming and drying, as well as to the socio-economic conditions produced after the democratization and economic liberalization in the early 1990sFootnote54. The fact that both environmental and socio-economic factors cause dzud is applicable to not only the present, but also to the past. Regarding the latter, this paper pointed out that with the expansion of pastoral production for domestic and foreign urban consumers, the consistent demand for individuals and pastoral cooperatives to achieve strict production quotas, regardless of any conditions, exacerbated the damage from dzud. That is, the slump in rural pastoral production during the collective period may have been caused by the interaction between the damage from dzud and the problems concerning the labor production system revised for responding to the challenges of industrialization under pastoral cooperatives. Unbalanced urban and rural populations placed a burden on rural pastoral production, which remains unchanged. The rapid increase in the demand for food and raw industrial materials in domestic and foreign urban areas changed not only the way livestock are raised and used, but also the government and people’s perception of dzud, countermeasures against them, and the nature of the damage they inflict.

Acknowledgement

This article contains revised and expanded material from “Mongorusougen ni okeru bokuchikumin to sizensaigai: Shakaishugiki no kansetsugai no jittai oyobi sonoeikyo,” which was originally published in Ristumeikan Pan-Pacific Civilization Studies, Vol. 3 (2019). I really appreciate for Professor Hiroki Takakura and Takahiro Ozaki, and two reviewers of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Takahiro Tomita

Takahiro Tomita is an assistant professor at Ritsumeikan Global Innovation Research Organization at Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan. He received his Ph.D. from the graduate school of Core Ethics and Frontier Sciences at Ritsumeikan University. His research interest centers on the relationship between people and the environment in modern Mongolia. His major publications include: “A Conflict between Migration and Settlement? Pasture Usage and Management in Post-Socialist Mongolia,” (The Central Asiatic Roots of Ottoman Culture, İSTESOB, 2014); “20seiki no Mongoru ni okeru ningen-kankyokankei: Bokuchiku no shudanka wo meguru rekisijinruigakuteki kenkyu” [Transformation of human–environmental relations in Mongolia during the 20th century: From the historical anthropology of agricultural collectivization], (co-edited, Ibou no doujidai, Ibunsha, 2017, in Japanese); and “Milk and Socialism: The Changing Use of Dairy Products in Rural Mongolia,” Ritsumeikan Pan-Pacific Civilization Studies, Vol. 4 (Yuzankaku, 2020, in Japanese).

Notes

1. Terada, Tensai to kokubo, 10–11.

2. Fujita et al., Mongoru, 22.

3. Sneath, “Land Use, the Environment and Development,” 447.

4. State Statistical Office of the MPR, National Economy of the MPR for 70 Years, 15.

5. Iida, “Gendai mongoru bokuchikugyo no mondaiten,” 15.

6. Even today, 30 years after the transition to the market economy, the exports of meat have not yet reached the levels of the collective period.

7. Mongolia tried to respond to the challenges of industrialization during the socialist era, while retaining traditional characteristics such as land sharing and high mobility (Fukui, “Bokuchikushakai heno apro-chi to kadai,” 11–16). Therefore, in this paper, livestock raising and use of livestock products during the socialist era are referred to as “industrialization of pastoralism” to distinguish it from modern livestock farming.

8. Oliver-Smith, “Theorizing Disasters,” 34.

9. Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism, Mongolia: Assessment Report, 13; and Shinoda, “Evolving a Multi-Hazard Focused Approach,” 76–77.

10. Fernández-Giménez, Batkhishig, and Batbuyan, “Cross-Boundary and Cross-Level Dynamics,” 836.

11. Templer et al., “The Changing Significance of Risk”; Komiyama, “Actual Damage to Mongolian Animal Husbandry”; and Jirigala et al, “Effects of Meteorological Factors.”

12. Fernández-Giménez, “Sustaining the Steppes”; and Nakamura, “Konzetsu to taisho.”

13. Sneath, “Spatial Mobility and Inner Asian Pastoralism,” 233–236; and Tomita, “20seiki no Mongoru ni okeru ningen-kankyokankei,” 161–166.

14. Fernández-Giménez, “Sustaining the Steppes,” 329–335; and Nakamura, “Konzetsu to taisho,” 47–56.

15. Janes and Chuluundorj, Making Disasters; Murphy, “Disaster, Mobility, and the Moral Economy of Exchange,” 307–308; and Eriksen, “Limitations of Wintering Away,” 93–94.

16. Bat-Oyun et al., “Who is Making Airag,” 8–9.

17. Shinoda, “Evolving a Multi-Hazard Focused Approach,” 77.

18. Shinoda and Morinaga, “Mongorukoku ni okeru kishousaigai no soukikeikai sisutemu no kouchiku ni mukete,” 940.

19. Sternberg, “Investigating Links Between Drought and Dzud,” 35.

20. Harayama, “Mongoru yuboku keizai no zeijakusei nituite no oboegaki,” 365.

21. Komiyama, “Mongorukoku chikusangyou ga koumutta 2000-2002nen zodo (kansetsugai) no jittai,” 76.

22. Komiyama, “Mongorukoku no 2010nen zodo (kansetsugai) wo furikaeru,” 34.

23. Ibid., 34.

24. Tomita, “Transformation of human-environmental relations,” 160.

25. Fernández-Giménez, “Sustaining the Steppes,” 315–342.

26. Nakamura, “Konzetsu to taisho,” 54.

27. Konagaya, “Mongoru bokuchiku sisutemu no tokuchou to henyou,” 38.

28. Shinoda and Morinaga, “Mongorukoku ni okeru kishousaigai no soukikeikai sisutemu no kouchiku ni mukete,” 934.

29. Templer et al., “The Changing Significance of Risk”; Komiyama, “Mongorukoku chikusangyou ga koumutta 2000-2002nen zodo (kansetsugai) no jittai”; and Jirigala et al., “Mongorukoku ni okeru zodohigai no chiikitokusei.”

30. In Mongolia, earthquakes, floods, forest fires, and dust storms are also regarded as serious natural disasters other than dzud and drought. For example, destructive earthquakes occurred in the northern and western regions in 1905 and 1957 in the 20th century (Ohya, “Mongoru ni jisindansou wo ou,” 37). There is concern about the risk of earthquakes in Ulaanbaatar. On January 12, 2021, an earthquake with a magnitude 6.5 occurred, with its epicenter at Khovsgol lake in north-western Mongolia, resulting in damaged buildings and roads in surrounding areas and in Ulaanbaatar, located about 600 km from the epicenter.

31. See note 21 above.

32. With the first revision of the pastoral cooperative model charter in 1959, the maximum number of privately owned livestock was limited to 50–75 per household. During the collective period, while raising public livestock was the top priority for pastoral cooperatives, raising private livestock was essentially positioned as a means of addressing the individual household’s food demand.

33. They almost correspond to the years when the large-scale dzud occurred, as estimated by Komiyama, “Mongorukoku chikusangyou ga koumutta 2000-2002nen zodo (kansetsugai) no jittai.”

34. In Bulgan, a high DR of livestock (14.7%) was also observed in the year immediately preceding (1967) the 1967/1968 dzud. At least in Bulgan, the occurrence of large-scale dzud for the second straight year is considered to be the reason for the particularly severe damage of the 1967/1968 and 1976/1977 dzud.

35. Choijirjav, Zudin tukhai zarim asuudal, 11.

36. The agricultural machinery station that corresponds to the machine tractor station (MTC) in Soviet Union was a state enterprise that provided services such as hay and fodder supply, the construction of shelters, the excavation of wells, and artificial breeding (Sakamoto, Mongoru no seiji to Keizai, 85).

37. Choijirjav, Zudin tukhai zarim asuudal, 10–11.

38. Natural hazards are naturally occurring physical phenomena such as severe and extreme weather and climate events. Natural hazards cause disasters that bring about destructive consequences for humans and other animals.

39. Murphy, Rationality and Nature, 5; and Nakamura, “Konzetsu to taisho,” 46–47.

40. There were relatively high sales of horse as meat in the areas that were active in the production of fermented mare’s milk (airag) such as Saikhan and Mogod.

41. Ozaki, “Zodo (kansetsugai) to Mongoru chihoushakai,” 24–26; and Du et al., “Kishousaigai no chiikisa wo umu shakaitekiyouin,” 2.

42. The Report on the 1967/1968 dzud also indicated that species of livestock most vulnerable to the dzud were goats, sheep, cattle, horses, and camels in that order.

43. For example, in 1976/1977, the DR (45.2%) exceeded the BR (30.8%), and the RNI was negative (−14.4%) in Dashinchilen, which was one of the most affected areas.

44. In Bulgan, considering that the average RNI was 28% during the collective period, it is surprising that the RP was 25%. At the district level, there was little difference in the RP between Buregkhangai (25.1%) and Mogod (25.7%). In this way, without regard to the production situation of each district, high quotas were allotted.

45. Oliver-Smith and Hoffman, “Introduction,” 6.

46. Templer et al., “The Changing Significance of Risk,” 111–112.

47. Nakamura, “Konzetsu to taisho,” 47.

48. Shinoda and Morinaga, “Mongorukoku ni okeru kishousaigai no soukikeikai sisutemu no kouchiku ni mukete,” 947.

49. Batmonkh, Jambin Batmonkh Enzetsuhoukoku, 57.

50. Konagaya, “Mongoru bokuchiku sisutemu no tokuchou to henyou,” 36–37.

51. Miaki, “Bokuchiku to shokuseikatsu,” 84.

52. Templer et al., “The Changing Significance of Risk”; Fernández-Giménez, Batkhishig, and Batbuyan, “Cross-Boundary and Cross-Level Dynamics”; Shinoda, “Evolving a Multi-hazard Focused Approach”; and Fujita et al., Mongoru.

53. Fernández-Giménez, Batkhishig, and Batbuyan, “Cross-Boundary and Cross-Level Dynamics,” 838..

54. Shinoda and Morinaga, “Mongorukoku ni okeru kishousaigai no soukikeikai sisutemu no kouchiku ni mukete,” 946–947.

Bibliography

- Batmonkh, J. Jambin Batmonkh enzetsuhoukoku [The Speeches of Jambin Batmonkh]. Translated by T. Matsuda. Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1987.

- Bat-Oyun, T., B. Erdenetsetseg, M. Shinoda, T. Ozaki, and Y. Morinaga. “Who Is Making Airag (Fermented Mare’s Milk)? A Nationwide Survey of Traditional Food in Mongolia.” Nomadic Peoples 19, no. 1 (2015): pp. 7–29. doi:10.3197/np.2015.190103.

- Bulgan Prefectual Archives. Jiliin etssiin mal toollogin material [Livestock Statistics in the End of Year]. Ф.1 Д.2 ХН.425-477.

- Choijirjav, K. Zudin tukhai zarim asuudal ba malchdin turshlagaas [Problems Concerning the Dzud: Learning from the Experience of Herders]. National Publishing Office: Ulaanbaatar, 1969.

- Du, C., M. Shinoda, H. Komiyama, T. Ozaki, and K. Suzuki. “Kishousaigai no chiikisa wo umu shakaitekiyouin [Social Factors Accounting for Local Differences in the Damage Caused by A Meteorological Disaster: A Case Study of the 2009–2010 Dzud in Mongolia].” Journal of Arid Land Studies 27, no. 1 (2017): 1–8. doi:10.14976/jals.27.1_1.

- Eriksen, A. “The Limitations of Wintering Away from Customary Pastures in Relation to Dzud in Mongolia’s Gobi Region.” Nomadic Peoples 24, no. 1 (2020): 86–110. doi:10.3197/np.2020.240105.

- Fernández-Giménez, M. E. “Sustaining the Steppes: A Geographical History of Pastoral Land Use in Mongolia.” The Geographical Review 89, no. 3 (1999): 315–342. doi:10.2307/216154.

- Fernández-Giménez, M. E., B. Batkhishig, and B. Batbuyan. “Cross-Boundary and Cross-Level Dynamics Increase Vulnerability to Severe Winter Disasters (Dzud) in Mongolia.” Global Environmental Change 22, no. 4 (2012): 836–851. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.001.

- Fujita, N., S. Kato, E. Kusano, and R. Koda. Mongoru: sougenseitaikeinettowa-ku no houkai to saisei [Mongolia: Collapse and Restoration of Ecosystem Networks with Human Activity]. Kyoto University Press: Kyoto, 2013.

- Fukui, K. “Bokuchikushakai heno apro-chi to kadai [Research Approaches to Pastoral Society and Their Problems].” in Bokuchikubunnka no genzou [Images of Pastoral Society], edited by K. Fukui and Y. Tani, 3–60. Tokyo: Nihonhousoushuppankyokai, 1987.

- Harayama, A. “Mongoru yuboku keizai no zeijakusei ni tuite no oboegaki [Memorandum on the Vulnerability of the Mongol Pastoral Economy].” Journal of the Society of Oriental Research 41, no. 2 (1982): 363–370.

- Iida, Y. “Gendai mongoru bokuchikugyo no mondaiten [Some Difficulties of the Livestock Sector in Mongolia].” Journal of Mongolian Studies 13 (1990): 2–39.

- Janes, C., and O. Chuluundorj. Making Disasters: Climate Change, Neoliberal Governance, and Livelihood Insecurity on the Mongolian Steppe. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press, 2015.

- Komiyama, H. “Mongorukoku chikusangyou ga koumutta 2000-2002nen zodo (kansetsugai) no jittai [Actual Damage to Mongolian Animal Husbandry Due to 2000–2002 Dzud Disaster].” Bulletin of Japanese Association for Mongolian Studies 35 (2005): 73–85.

- Komiyama, H. “Mongorukoku no 2010nen zodo (kansetsugai) wo furikaeru [Looking Back on the 2010 Dzud in Mongolia].” Nihon to Mongol [Japan and Mongolia] 35 (2013): 33–38.

- Konagaya, Y. “Mongoru bokuchiku sisutemu no tokuchou to henyou [Characteristics and Transformation of Pastoral System in Mongolia].” E-Journal GEO 2, no. 1 (2007): 34–42. doi:10.4157/ejgeo.2.34.

- Miaki, T. “Bokuchiku to shokuseikatsu [Pastoralism and Food]. In Mongoru nyumon [Introduction to Mongolia], edited by Japan Mongolia Cross Link Association, 53–108. Tokyo: Sanseido, 1993.

- Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism, Mongolia. Mongolia: Assessment Report on Climate Change 2009. Mongolia: Ulaanbaatar: Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism, 2009. https://www.preventionweb.net/go/12564

- Murphy, D. “Disaster, Mobility, and the Moral Economy of Exchange in Mongolian Pastoralism.” Nomadic Peoples 22, no. 2 (2018): 304–329. doi:10.3197/np.2018.220207.

- Murphy, R. Rationality and Nature: A Sociological Inquiry into A Changing Relationship. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994.

- Nakamura, T. “Konzetsu to taisho: Mongorukoku sabakuchiiki ni okeru zodo (kansetsugai) taisaku [‘eradication’ and ‘Management’: Measures against the Dzud (Cold and Snow Damage) in the Desert Area of Mongolia].” In Ajia no Seitaikiki to Jizokukanousei: ‘Field’ kara no ‘Sustainability’ ron [Ecological Crisis and Sustainability in Asia: A Synthesis of Field Studies], edited by K. Otsuka, 39–72. Chiba: IDE-JETRO, 2015.

- National Archives of Mongolia. 1967–1968 oni zudtai temtssen ajlin dungiin tukhai ulsin komissin tailan. Х.356 Д.1 ХН.107.

- National Archives of Mongolia. 1983 Bulgan aimagiin KHAA-n negdluudiin 1983 oni jiliin etssiin tailan balansin negdsen tovchoo. Х.356 Д.2 ХН.492.

- Ohya, S. ““Mongoru Ni Jisindansou Wo Ou [Tracing an Earthquake Fault in Mongolia].” Chishitsu News 617 (2006): 24–40. https://www.gsj.jp/data/chishitsunews/06_01_03.pdf.

- Oliver-Smith, A. “Theorizing Disasters: Nature, Power, and Culture.” In Catastrophe and Culture, edited by A. Oliver-Smith and S. Hoffman, 23–48. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 2002.

- Oliver-Smith, A., and S. Hoffman. “Introduction: Why Anthropologists Should Study Disasters.” In Catastrophe and Culture, edited by A. Oliver-Smith and S. Hoffman, 3–22. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 2002.

- Onishi, J. T., M. Senge, and S. Samdan. “Mongorukoku ni okeru zodohigai no chiikitokusei [Effects of Meteorological Factors on Dzud Damage in Mongolia].” IDRE Journal 283 (2013): 33–40. doi:10.11408/jsidre.81.527.

- Ozaki, T. “Zodo (kansetsugai) to Mongoru chihoushakai [Dzud (Cold and Snow Damage) and Local Society: A Case Study of Bulgan Prefecture in the 2009/2010 Winter].” Kadai-Shigaku 58 (2011): pp. 15–33.

- Sakamoto, K. Mongoru no seiji to Keizai [Political Economy of MPR]. IDE-JETRO: Tokyo, 1969.

- Shinoda, M. “Kansouchisaigaigaku no taikeika (1) [Integrating Dryland Disaster Science (1): An Overview].” Proceedings of the General Meeting of the Association of Japanese Geographers, no. 2017 (2017a): 100022. doi:10.14866/ajg.2017a.0_100022.

- Shinoda, M. “Evolving a Multi-Hazard Focused Approach for Arid Eurasia.” In Climate Hazard Crises in Asian Societies and Environments, edited by T. Sternberg, 73–102. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017b.

- Shinoda, M., and Y. Morinaga. “Mongorukoku ni okeru kishousaigai no soukikeikai sisutemu no kouchiku ni mukete [Developing a Combined Drought-dzud Early Warning System in Mongolia].” Geographical Review of Japan 78, no. 13 (2005): 928–950. doi:10.4157/grj.78.13_928.

- Sneath, D. “Spatial Mobility and Inner Asian Pastoralism.” In The End of Nomadism? Society, State, and the Environment in Inner Asia, edited by C. Humphrey and D. Sneath, 218–277. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Sneath, D. “Land Use, the Environment and Development in Post-Socialist Mongolia.” Oxford Development Studies 31, no. 4 (2003): 441–459. doi:10.1080/1360081032000146627.

- State Statistical Office of Mongolia. Agriculture in Mongolia: 1971-1995. Ulaanbaatar: State Statistical Office of Mongolia, 1996.

- State Statistical Office of the MPR. National Economy of the MPR for 70 Years: 1921–1991. Ulaanbaatar: State Statistical Office of the MPR, 1991.

- Sternberg, T. “Investigating the Presumed Casual Links between Drought and Dzud in Mongolia.” Natural Hazards 92, no. S1 (2018): 27–43. doi:10.1007/s11069-017-2848-9.

- Templer, G., J. Swift, and P. Payne. “The Changing Significance of Risk in the Mongolian Pastoral Economy.” Nomadic Peoples 33 (1993): 105–122.

- Terada, T. Tensai to Kokubo [Natural Disasters and National Defense]. Kodansha: Tokyo, 2011.

- Tomita, T. “20seiki no Mongoru ni okeru ningen-kankyokankei: Bokuchiku no shudanka wo meguru rekisijinruigakuteki kenkyu1 [Transformation of Human-environmental Relations in Mongolia during the 20th Century: From the Historical Anthropology of Agricultural Collectivization].” In Ibou no doujidai [Alternative Look at the Contemporary], edited by K. Watanabe, C. Ishida, and T. Tomita, 141–172. Tokyo: Ibunsha, 2017.