ABSTRACT

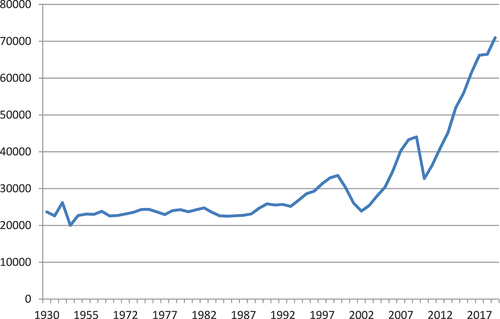

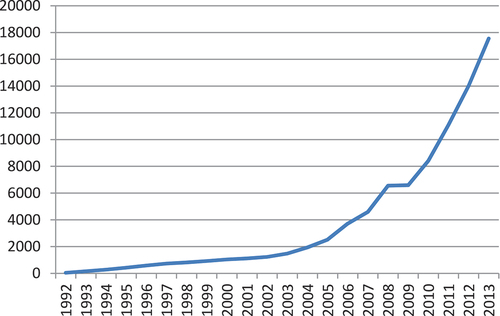

This paper provides an insight into the framework employed to revisit Mongolian modern history. The term “environmental disaster” signifies the social process of entanglement in human-environmental interactions, emphasizing the failure of human actions. The Mongolian pastoral society is vulnerable to various kinds of disasters, among which the most problematic is dzud (cold and snow disaster), resulting in heavy damage to livestock. A severe disaster can be a cue to initiate social change, which emerges at the phase of resilience, as disasters may be recognized as a result of social instability. Although there were two severe dzud, the total number of livestock was relatively stable during the collectivization era (1959–1992). After the collapse of the socialist regime and the end of economic dependency on the USSR, the nation’s total number of livestock increased until 1999. However, it saw a sharp decrease during the nationwide dzud (in 1999–2002), which continued for three years. This unprecedented dzud also brought about a change in pastoralism. Nowadays, even the people in pastoral lands depend on imported commodities associated with globalization. The rural landscape in Outer Mongolia has changed into two types: suburban areas, including areas around cities and near major roads; and remote areas, including typical Mongolian rural areas that do not have up-to-date socio-economic services. This distinction makes it a complex situation, especially when the questions of disasters arise for the Mongolian people.

1. Introduction

This paper provides insight into the issues of Mongolian modern disaster history. As the introductory paper in the special issue of “Policy-Related Environmental Disaster and the Socio-Cultural Impacts in Mongolia,” it provides the informative framework of guiding the other papers in the issue.

It would be challenging to identify the difficulties that have occurred among the Mongolian people, as well as disasters, without understanding the chronological challenges and the corresponding pastoral culture the land has experienced over the past centuries. Contemporary social scientists believe that not just one natural calamity makes for a disaster, but rather a range of natural hazard that surpasses human capacities and institutionsFootnote1. Thus, the term “environmental disaster” has been adopted, which is not restricted to a simple “natural disaster,” but also encompasses social processes that are intertwined with human-environmental interactions, while emphasizing the failure of such interactions. Incidentally, the local people think of disaster as natural hazards related to their pastoral activities, making it an environmental disaster.

In Mongolia, nomadic pastoralism is not only a cultural tradition, but also an economic branch of industrialization throughout the 20th century. This paper discusses environmental disasters associated with agricultural policies and urbanization during the socialist regime. It also discusses the increase in the political-economic relations with China in the 21st century, in tandem with an overview of Mongolian history and pastoralism.

2. Natural environment and pastoralism in Mongolia

The Mongolian plateau, where the Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolian autonomous regions are located, is a land mainly used for pastoralismFootnote2. Mongolian pastoralists usually keep five types of livestock: sheep, goats, cattle, horses, and camels. Each livestock is used in accordance with their features, such as for subsistence use, or for trade to obtain essential commodities that are difficult to produce in the Mongolian plateau (, ). The Mongolians also keep a variety of livestock to enable risk management, as to avoid losing all livestock in case of a disaster. For example, goats are more vulnerable to cold than sheep, though they can endure drought more easily. Cattle are more susceptible to deep snowfall than horses, although horses tend to stray away from pastoral camps when strong winds blow. In Mongolia, such phenomena are common, as discussed later.

Table 1. Usage of Mongolian livestock for subsistence use and MSU.

Table 2. Comparison of average area of pasture, number of livestock and livestock density.

The Mongolian plateau is a temperate steppe dominated by grasses such as StipaFootnote3. Although such grasses are generally not edible for human consumption, livestock rely on them and they can be converted into food, drink, and clothing for pastoralists. The Mongolian meteorological characteristics include dry and cold temperatures, with the mean annual air temperature in Ulaanbaatar as low as −0.1°C, and a mean annual precipitation of 281 mm. The lowest air temperature recorded was −55.3°C in Zuungobi, in 1976, while the highest air temperature was 44.0°C in Darkhan, in 1999Footnote4. Precipitation is mainly observed in the summer, especially from June to August.

Mongolians follow mobile pastoralism (nomadism), moving their flocks and houses between two to four times a year. Some of the reasons for nomadism include making sure the grass, a remarkable source of fodder, is not affected by the temperate steppe, especially in the case of wealthy pastoralists who own many livestock. Another reason is that the seasons change the suitability of places. For example, accessibility to water is the most important factor in summer, while cold protection is the most important in winter. Therefore, in summers, the lower basins are more suitable, while in winters, the severe cold forces the pastoralists to move to the southern hillside. Contrastingly, pastoralists face a lack of water in the summer. In addition, pastoralists often conduct irregular and frequent movements called otor, to avoid disaster occurrences, or to have livestock eat more grass than usual.

The daily labor is organized and divided according to the logic of pastoralism. The minimum social unit of Mongolian pastoral society is a household that includes a married couple and their unmarried children living in a ger (a tent with a wooden frame and felt covers), which is usually gifted by their parents for their marriage. In regards to labor, a flock of sheep or goats with less than 1000 heads can be managed by a herder riding on a horse. The number of livestock in a typical household is usually less than that, as a “1000 household keeper” is associated with very wealthy people. Sometimes, a group of small-scale household keepers form a group to compose a large-scale flock, in order to save on the labor required to manage everyday grazingFootnote5. Such a herding group, called a hot ail, shares camp sites and seasonal movement. Beyond the hot ail, another herding group, called the saahalt ail, is organized to save labor for milking cattleFootnote6. On the other hand, rich herders and organizations, like local governments with many livestock, tend to entrust poorer pastoralists with herding duties, who in turn use the milk for freeFootnote7.

Regarding economic aspects, the Mongolian pastoralists were not self-sufficient, at least not during the Qing dynasty era. Mongolian pastoralists were geopolitically adjacent to the massive Chinese agrarian society to the south, which facilitated the finding of stable trading partners. Tea was the principal good produced in southwestern China, including the Sichuan province. Although a staple beverage, it must have been difficult surviving on solely Mongolian milk tea. Thus, Mongolian pastoralists may have also traded with different communities for various other commodities. A book published in the early 20th century reported that even poor pastoralists habitually drank tea.Footnote8 Therefore, it can be concluded that the Mongolian pastoralists depended overall on trade for other commodities.

In addition to livestock, Mongolian pastoralists sold wool (including cashmere) and hide, in order to purchase commodities such as tea, grains, and miscellaneous daily goods. At that time, it was difficult for pastoralists to engage in long-distance trade with mainland China by themselves. Therefore, trade was operated by the Han Chinese merchant companies whose staff visited Mongolian pastures until the People’s Revolution in 1921 in Outer Mongolia, and the 1940s in Inner MongoliaFootnote9. Although they have been criticized for their excessive profits, the merchants enabled the Mongolian pastoralists to specialize in pastoralismFootnote10. However, there were some exceptions. Horchin Mongolians in the southeastern part of Inner Mongolia were semi-agricultural from the 17th century, and an incarnation Lama organized pastoralists to engage in long-distance transportation of goods to repair a monasteryFootnote11.

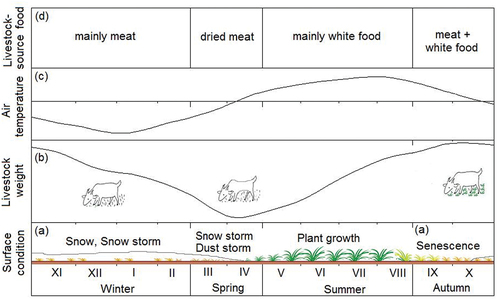

3. Natural disasters in Mongolian pastoral society

Mongolian pastoral society is vulnerable to a few natural disasters. It relies on natural grass that grows in the temperate steppe, whose production is not aplenty. The period of growth for natural grass in the Mongolian Plateau is only between May and September () due to its cold and dry climate. Therefore, livestock must eat grass that has dried out on the surface of the land from late autumn to early spring. As the temperature of this period is extremely low, animals and humans alike need a sufficient caloric intake to maintain their body temperature. Moreover, early spring is the season of reproduction in livestock. Taking such situations into consideration, surviving the harsh winter is critical. Otherwise, the pastoralists lose a number of livestock. Thus, natural disasters are a cause of mass livestock loss in Mongolia.

Figure 1. Relationship between Mongolian natural environment, pastoralists’ food and livestock weight.

As Shinoda points out, major disasters in Mongolia include the “4Ds”: drought, dust storms, dzud (cold and snow disaster), and desertificationFootnote12. These disasters are interrelated. First, drought occurs due to low rainfall in summer, as is often the case with drylands. The annual variability of rainfall is rather large in MongoliaFootnote13. Subsequently, the decline in soil moisture owing to drought causes dust storms to occur more easily. Simultaneously, drought causes the height of grass to be lower than average. As a result, the possibility of dzud, mainly caused by cold temperature and snowfall in winter and spring, also increases because shorter grass is harder to reach and this lack of grass worsens the nutrition of livestock. Shinoda refers to this sequence from drought to dust and dzud as “memory process.”Footnote14 Finally, if the frequency of drought years increases, owing to global warming or overgrazing, desertification occurs in that region.

Among these disasters, the most problematic is dzud, as it causes heavy damages to pastoralism. Historically, dzud has happened regardless of the social system of the time. However, its frequency and scale seem to vary over time, as mentioned below.

Dzud is not just a synonym for extreme climate phenomena, including heavy snow, as Natsagdorj points out. Pastoralists traditionally recognize dzud as natural and weather conditions that cause significant animal lossFootnote15. This can be a result of animal weight loss due to non-accessibility and shortage of pasture forage and water in the winter-spring season. As such, animal loss is the key concept of dzud.

Komiyama enumerates five types of dzud, among which the first three are often mentioned by MongoliansFootnote16. Firstly, black dzud, caused by a shortage of precipitation (snowfall), weakens livestock. White dzud is caused by heavy snowfall that prevents livestock from eating grasses under the snow. Additionally, iron dzud causes snow melting in the daytime, which gets frozen later and prevents livestock from eating the grasses. Cold dzud is caused by extremely cold chills. Finally, windy dzud is caused by prolonged storms.

In sum, dzud is a human-related phenomenon that causes damage to human activity (pastoralism). Moreover, it may be true that all kinds of disasters are related to human activity; otherwise, it is just an extreme natural phenomenon.

A disaster cycle has three phases, all of which relate to the vulnerability of the nature-society system: exposure (pre-event), sensitivity (the event), and resilience (post-event)Footnote17. As for dzud, exposure can be influenced by avoidance behavior such as otor or weather forecast. Sensitivity can be influenced by preparatory actions such as accumulation of hay or preparation of the livestock pen. Resilience can be influenced by some policies such as aid for purchasing new livestock or tax exemption on livestock. Needless to say, such influencing factors have had close relationships with the social system at the time because policies have drastically varied according to changes in the social system in both Outer and Inner Mongolia. In the next section, the history of Mongolian pastoralism and disasters will be briefly depicted, based on the Outer Mongolian periodization, while the situation of Inner Mongolia will be mentioned as a reference.

3.1. Before the Mongolian people’s revolution (−1921)

As Sneath points out, Mongolian pastoralism in the pre-collectivization era can be depicted as a range of productive activity bound by two ideal poles: the “yield-focused” mode, and the “subsistence” modeFootnote18. The “yield-focused” mode made use of a relatively large amount of movement in order to gain the maximum return on the herd-wealth. It was based on the ownership of large numbers of animals, utilizing hired labor and entrusting them to pastoralist families who were under the supervision of the owners. On the other hand, the “subsistence” mode was oriented toward satisfying domestic requirements and was characterized by each pastoral family owing and herding relatively small numbers of several species of domestic livestock.

To explain his model, Sneath took the example of a former temple banner that Simukov researched in 1935Footnote19. This model is needed to understand Mongolian pastoralism at the time, although the word “subsistence” could be a little exaggerated. Even families with a small number of livestock purchased commodities from Han Chinese merchants, so their pastoralism was not an activity of subsistence in the strict sense.

Prior to the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912, there were jasag banners governed by hereditary nobles, and amban banners governed by the vicegerents of the Qing emperor, in addition to temple banners that were ruled by the reincarnations in MongoliaFootnote20. The social conditions differed accordingly because the rulers of each banner were independently responsible for their social order. For example, pastures of temple banners tended to be utilized by the temple unitarily, while pastures of some jasag banners were divided by groups of noblemen and their subordinate peopleFootnote21.

Legally, movement across the boundaries of banners was prohibitedFootnote22. However, in reality, this prohibition was not enforced as long as pastoralists did not attempt to remove themselves from the jurisdiction of their bannersFootnote23. Therefore, if needed, they moved across the border for otor, in case of disasters such as dzud.

For example, the banner of Togtohtur, in the eastern part of Outer Mongolia, was subjected to an extreme drought and dzud in 1851. Pastoralists of the banner fled to the adjacent Barga Mongolian territory in Inner Mongolia. Later, Togtohtur succeeded in reducing various types of corvees assigned to his banner. A series of economic and cultural reforms were then planned and conducted in order to recover the losses incurred to the budget and life as a result of dzudFootnote24.

The collapse of the Qing dynasty was a meaningful event as it initiated social separation between northern (Outer) and southern (Inner) Mongolia. The People’s Revolution was the second event that made Outer Mongolia virtually independent of the Republic of China, both politically and economically.

3.2. Disasters before collectivization (1921-1959)

After the Mongolian People’s Revolution, Outer Mongolia underwent a few socialist reforms in the 1920s and the 1930s. Livestock owned by lords and temples were confiscated, Han Chinese merchants were expelled, resulting debts were defaulted, and administrative units’ names and territories were changed. Moreover, socialistic collectivization was attempted in the early 1930s, though it failed soon owing to the pastoralists’ strong oppositionFootnote25. However, newly established districts (sum) throughout the country in the early 1930s mostly survived until today. These districts, which are smaller than former banners, started to regulate the areas of pastoralists’ seasonal movementFootnote26. However, the small size of the new districts might not have been an issue as “subsistence” pastoralists who engaged in minimal movements, in both distance and frequency, gained predominance following the socialist reformsFootnote27.

As Sneath points out, pastoralists of “subsistence” tend to save up livestock, while “yield-focused” ones tend to sell as much livestock as possibleFootnote28. At first glance, the former appears to be increasing their assets. However, judging from the whole system, it is not likely that pastoralists of “subsistence” could become a majority. An increasing number of livestock means increasing the need for grass, thus increasing the sensitivity to dzud.

The present southeastern region of Sukhbaatar province was called Dariganga stock farm in Qing dynasty, where the livestock of the imperial family were herded by designated pastoral families who were administered by an ambanFootnote29. After 1912, this area was renamed as Dariganga banner as it came under the rule of Outer Mongolian Bogd Haan’s governmentFootnote30, who was the newly appointed jasag of the bannerFootnote31. This area continued to be untouched shortly after the People’s Revolution because the living standard of Dariganga was much better than that of surrounding banners, as a result of the legacy of being imperial property. However, after this area was severely damaged by 1923–24 dzud, the Dariganga banner was divided into 18 small districts, similar to other local administrative systemsFootnote32. Thus, in Mongolia’s case, a severe disaster like dzud can be a cue for social change, which emerges at the phase of resilience.

At the same time, disasters may be recognized as a result of social instability, as well as extreme climate phenomena, which affect sensitivity. As Komiyama points out, one of the most damaging dzud in Outer Mongolia after 1940 occurred in 1944–45, during the later stages of the Second World WarFootnote33. Additionally, a severe dzud in the central part of Inner Mongolia, that will be discussed in the next chapter, occurred in 1977–78, in the final year of the Cultural RevolutionFootnote34.

3.3. Disasters and socialist collectivization (1959-1992)

After WW2, Outer MongoliaFootnote35 was incorporated into the economic bloc of the USSR. The role of Outer Mongolia was to supply livestock for meat and other products, such as hide, wool, cashmere, and casing. After the 1970s, mineral products such as copper, uranium, and fluorspar were added as Mongolia’s export goodsFootnote36. In return, Mongolia imported gasoline, light oil, and machines through barter trade from the USSR.

The collectivization of pastoralism began at the end of the 1950s, centralizing the right of property on livestock and the right of decision on pastoral management to the state organization, mainly because the former economic plan was not accomplished in the realm of pastoralism. As collectivization of this time succeeded without pastoralists’ strong opposition, the rate of organization became as high as 97.7% in 1959, only a year after the start of collectivization. The territory of a negdel (collective) corresponded to an existing district and was usually spatially divided into brigades. The Mongolian pastoralism of this era can be referred to as the maximization of the “yield-focused” mode, as Sneath points outFootnote37. Outer Mongolia as a whole became similar to former large-scale livestock owners such as lords or temples. They needed to produce as much livestock as possible in order to be able to purchase a variety of commodities from the USSR through barter trade, instead of from Han Chinese merchants as prior to the People’s Revolution. The technology used by Mongolian collectives also resembled that of former large-scale livestock owners. They regulated seasonal movement and organized large flocks composed of a single kind of livestock.

It is interesting to note that the total number of livestock was relatively stable during the collectivization period. Severe dzud occurred only twice, in 1967–68 and in 1976–77, although additional reports also mention other yearsFootnote38.

There were several factors that could have affected the low occurrence of dzud during the collectivization period. Firstly, the number of livestock that had to survive winter was relatively small and stable, as a considerable number of them were exported before winter. Secondly, winter pens were constructed and fodder was prepared by negdel, while special pasturelands reserved only for otor in case of dzud were designated by the central government. Finally, logistics were also assumed by the national sector. Therefore, pastoralists who were laborers of negdel were able to dedicate themselves to herding flocks at the most ecologically suitable pasture regardless of remoteness from markets.

However, even such preferable conditions could not prevent dzud. For example, the Hongor district of the former Dariganga banner area was dissolved in 1968 because its livestock was drastically decreased by the 1967–68 dzud. Meanwhile, the number and weight of commodities that pastoralist households utilized increased, such as beds made of steel pipes, glass windows set at the ceiling of tents, or porcelain dishes. These items were made in countries within the economic bloc of the USSR, most of which were located in central-eastern Europe and imported into Mongolia along the official distribution network.

During the collectivization era, sedentary dwellings were constructed in cities and centers of state farms, as well as negdel. However, pastoralists in Outer Mongolia did not become sedentary like the Buryats in the USSRFootnote39.

Additionally, in the central part of Inner Mongolia, full-scale sedentarization of pastoralism did not occur until the 1980s, even though the number of seasonal movements considerably decreased after the socialist revolution of 1949 and the ensuing social reformFootnote40. In 1977–78, a severe dzud occurred in the central part of Inner MongoliaFootnote41. The high density of livestock, caused by the low sale rate in autumn during the Cultural Revolution, was pointed out as the reason for this dzudFootnote42.

To recover quickly from this dzud, the privatization of common livestock owned by the people’s commune and the sedentarization of pastoralists were undertaken by local governments. These policies coincided with the reform and door-opening policies at the national level, which Deng Xiaoping employed after the end of the Cultural Revolution. Therefore, the right of pasture use was given to each household, as well as livestock. The right of pasture use was substantialized during the 1990s, when pastoralists built and began to live in sedentary houses made of brick, while enclosing all of their pastures with barbed wire. As pastures were divided according to each household and the number of livestock recovered, the possibility of organizing hot ail became smaller. Simultaneously, they could sell more livestock to the domestic market. Pastoralists who held rather large pasture areas, such as the northern part of the Shiliingol league, became rich, hiring live-in pastoral laborers who came from poorer areas of Inner MongoliaFootnote43.

3.4. Transitional period (1992-2002)

The collapse of the USSR at the end of 1991 immediately influenced Outer Mongolia, which relied on the Soviets both politically and economically. Even in the realm of pastoralism, democratization took place. The abolishment of negdel and state farms was initiated in 1992, which led to the disappearance of leadership in economic activities and the distribution of public assets, such as livestock and pens for winter for individual pastoralists. However, pastures have not yet been privatized, and the sizes of administrative units have remained unchanged since the early 1930s. At the same time, the former barter trade system collapsed and the distribution system in Outer Mongolia was blocked. Such social circumstances led to freedom of movement and the sale of livestock, which had a double meaning for pastoralists. In one sense, they were able to keep livestock as they wanted and move freely. In another sense, they became free of distribution networks and were able to ship their produce and purchase necessities from outside.

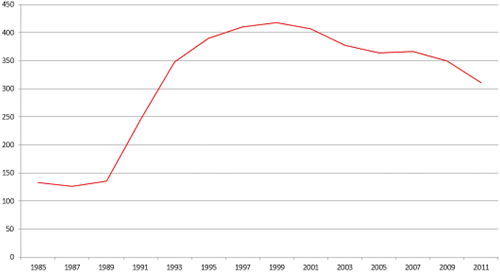

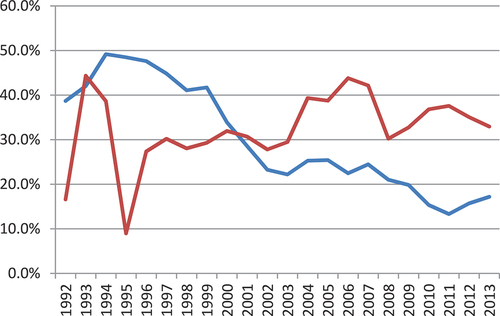

Fernandez-Gimenez pointed out that in the Bayanhongor province, livestock herded by pastoralists tended to be concentrated near roads and district centers in the mid-1990s. Ozaki points out that in Ongon, seasonal movement patterns of pastoralists who kept a relatively large number of livestock were basically the same as that of the collectivization eraFootnote44. On the other hand, Fernandez-Gimenez further pointed out that absentee-owned livestock tended to be concentrated on wealthier pastoralists who were famous for their pastoral skillsFootnote45. Similarly, Ozaki pointed out that less experienced people who became pastoralists after the 1990s due to bad economic situations such as unemployment, tended to join wealthy and experienced pastoralists’ hot ailFootnote46. They hoped to increase the number of their livestock for meat, relying on experienced pastoralists’ skills and infrastructures such as winter pens that they obtained at the collapse of negdel. These trends show that a few pastoralists wanted to increase their livestock, even utilizing technologies of “yield-focused” mode, while their products could not be sold as in the collectivization era. As Mongolia suffers from severe cases of foot-and-mouth disease, it is difficult to sign health requirements for the export of cloven-hoofed animals with foreign countriesFootnote47. Therefore, cashmere was almost the only profitable livestock-related export during the transitional period.

Therefore, pastoralism in Outer Mongolia shifted more or less to that of “subsistence” mode, though they were not satisfied with the lifestyle they regarded as a recession. As a result, the nation’s total number of livestock increased to reach 33.57 million in 1999. However, it sharply decreased in the nationwide dzud, which lasted for three continuous years. In 2002, it declined to the same level as that of 1989. This unprecedented dzud also brought about a change in pastoralism in Outer Mongolia. For example, population inflow into Ulaanbaatar has acceleratedFootnote48, as small-scale pastoralists who lost most of their livestock gave up pastoralism, which required a considerable number of livestock as capital stock.

3.5. Today (2002-)

Just after the end of the dzud, nominal GDP in Mongolia jumped up because the price of mineral products generally increased. Simultaneously, a considerable amount of investment in mining development was introduced from outside the country. As a result, the production of gold dust was reinforced, while new mines of copper, coal, petroleum, and so on were newly opened. Mineral products other than gold were mostly exported directly to China, which was in the middle of a construction boom. Thus, newly opened mines were generally located near the border with China.

A variety of infrastructure was constructed using the abundant income, such as buildings in Ulaanbaatar, paved roads interlinking major cities across the country, as well as coverage of cellular phones in sedentary areas and along major roads. Simultaneously, the market function of cities and nationwide distribution networks were restored, although costs for transportation are now to be incurred by individuals involved, unlike during the collectivization era.

Today, affluent commodities are mainly imported from foreign countries into cities. For example, generators, cellular phones, satellite TV sets, and automobiles are now indispensable to pastoralists at large, even if the herding camp may be out of service.

Under such circumstances, pastures in Outer Mongolia are spatially divided into two types: suburban areas, which are composed of areas around cities and nearby major roads, and remote areas, which are typical Mongolian rural areas and inconvenient for up-to-date socio-economic services. The characteristics of the former are the availability of cellular phones, convenient roads, and markets in the cities, all of which came into existence after the 1999–2002 dzud.

Regarding the commercialization of livestock products, there are some differences today as compared to the pre-collectivization era. Liquid dairy products such as airag (fermented mare’s milk) and cow’s milk were commercialized during the collectivization era, when urbanization took place under state policy. It was also a time when the number city dwellers who purchased such dairy products increased. After the collapse of collectivization, the production and sale of such products was handled by individual pastoralists, although it was not easy because they lacked measures of transportation and information on consumers. However, after 2000, pastoralists in suburban areas found that the sale of dairy products became profitable. The use of cellular phones to take orders, as well as the short distances from cities to save time and transportation fees were the exclusive merits of suburban areas. As such, suburban pastoralists, as well as remote pastoralists, were able obtain extra income from the sale of dairy products, in addition to livestock and cashmere.

Therefore, suburban areas emerged after the dzud, where pastoralists could earn more income than those in remote areas with the same number of livestock. This was due to the fact that the sales of dairy products and cashmere did not necessarily reduce the number of livestock, unlike sales of livestock themselves for producing meat. However, suburban areas are not always suitable for every pastoralist. The privatization of pastures is not legally allowed in Outer Mongolia and there is no way to prevent the inflow of pastoralists into suburban areas, even if the density of livestock and pastoralists becomes too high and hinders ensuring that all livestock survive the winter. For example, a wealthy pastoralist who lived in a suburban pasture near the central city of Bulgan province complained that as many as 4000 livestock of 20 hot ail existed year-round within a 2 km radius from his winter camp. He said he was unable to move away for fear that someone would move into his winter camp pasture while he was gone. Options available to him were to either purchase enough hay for winter or to entrust a part of his livestock to pastoralists living outside the region, as countermeasures for dzud. Therefore, there are some wealthy pastoralists who deliberately prefer remote areas. On the other hand, poor pastoralists cannot help but live in suburban areas because pastoralism in remote areas tends to sell on a large scale with small profits. Thus, it requires a larger management scale, that is, a larger number of livestock.

Although it remains ambiguous whether pastoralism in suburban areas is generally more vulnerable to a disaster than that in remote areas, the damage can be very serious if a large-scale disaster occurs in such a crowded area.

For example, an extremely strong storm accompanied a blizzard and dust storm in the eastern area of Mongolia on 26-May 272,008. This windy dzud caused the death of 243,000 animals, which was the most severe damage since the 1980sFootnote49. As it happened without noticeable precursors, except for a weather forecast that had been announced several days before, most pastoralists did not pay heed to itFootnote50. Damage to suburban areas surrounding a small mining village of Berh, where the blizzard was extremely severe, caused the death of seven pastoralists and 11,000 animalsFootnote51.

After the dzud and because a proportion of sheep and goats could now breed twice a year, the total number of livestock began increasing again from 1999 to 2002 at an accelerated pace. However, another nationwide dzud occurred in the winter of 2009–2010, which killed 11.3 million (26%) of livestock in Outer Mongolia (Nakamura, Citation2019)Footnote52. According to OCHA, the causes of this dzud include: 1) the summer drought affecting many parts of the country; 2) an increased national herd, especially in goat population, with cashmere as a “cash crop”; 3) unusually cold winter in many areas for a long period; 4) frequent and heavy snowfall, preventing access to winter grazing; and 5) lack of stored hay for distribution and sale, as a series of good summers resulted in a poor market for hayFootnote53. However, the dzud of 2009–2010 attracted much less attention than the dzud from 1999 to 2002, which was referred to as equaling the dzud of 1944–1945, in spite of OCHA’s appeal. Sternberg points out that drought, socio-economic forces, and resource management practices are major contributory factors, while the extreme winter was the immediate cause of the 2010 dzud. Furthermore, a great increase in animals without an expansion of essential inputs such as water points, transport, winter fodder, and emergency support led to livestock intensification and potential overgrazingFootnote54. However, the common opinion of the relevant people who engaged in international aid was that “Mongolia is not poor, how it decides to use its mineral wealth is the question”Footnote55.

On the other hand, the effect of otor, which was conducted as a measure of escaping the dzud, was questioned partly because of the unprecedented number of livestock. Fernandez-Gimenez et al. points out that at a local spatial level and short (one winter) time period, otor is adaptive and beneficial for the herders making the move, and can be harmful and potentially maladaptive for those receiving otor herdersFootnote56.

However, the total number of livestock began to increase shortly after the dzud of 2009–10, as quickly as before the dzud. Therefore, we can conclude that the impact of 2009–10 dzud was not as severe as to change the total system of Outer Mongolian pastoralism.

Meanwhile, there was also the penetration of infrastructure development and market economy into pastoral areas in Inner Mongolia. The cue was China’s Western Development policy, which started in 2000 to simultaneously target economic development and environmental protection. As a result, the area’s economic structure changed drastically. Today, in both Inner and Outer Mongolia, the main industry is not pastoralism, but mining, although the process of change was not the same for both.

Under sedentary pastoralism using pastures allotted to each pastoralist household and relying on purchased hay for the winter, dzud did not occur in the winter of 1999–2000. However, this did not mean that was no disaster occurred. A severe dust storm that arose in Inner Mongolia hit Beijing in the autumn of 1999Footnote57. The central government was shocked and attributed the disaster to pastoralists’ inappropriate destruction of the environment with overgrazing, which in turn made them considerably poorer, as Han Chinese tended to regard minority cultures as backwardsFootnote58.

Important policies of China’s Western Development were centered on the construction of infrastructure and the protection of the natural environment. Therefore, railways, roads, and airports are being constructed at a rapid pace. Among the policies for the protection of natural environment, the most conspicuous one was the “environmental migration” by which pastoralists moved to newly constructed villages near cities with a considerable subsidization. Grazing outside was also bannedFootnote59, and requirement for balancing the carrying capacity and livestock were more influential in a vast area. However, these policies tended to be implemented as measures for poverty programs or tourism promotion by local governmentsFootnote60. In some cases, they eagerly clamped down the violators of the policy, as penalty charges were treated as income for the local governmentFootnote61.

As a result, the number of pastoralist livestock declined, with some exceptions. One such case was that the area of pasture that pastoralist households kept varied according to the location of the county (sum) and population density. Another case was that the number of camels and horses were not calculated in order to balance the carrying capacity and livestock because they were targets of the protection policy. Moreover, in some districts, the requirement for balancing the carrying capacity and livestock was not strictly introduced for a variety of reasons, in comparison with the ban on grazing outsideFootnote62.

As such, suburban areas emerged in Inner Mongolia, whereas the movement of pastoralists was restricted without borrowing or inheriting others’ pastures. In Inner Mongolia, suburban areas are characterized by extra measures to obtain cash income in favor of the location of nearby cities, such as operating tourist camps and selling airag. For pastoralists living in remote areas of Inner Mongolia, sellable products are basically the same as those of Outer Mongolia, even though almost all roads are paved and coverage of cellular phones is much widerFootnote63.

In Outer Mongolia, the national average MSU/ha was 0.65 in 2013, with a slight increase from 0.63 at the end of 1999. Therefore, we can distinguish that the livestock densities of some places in Outer and Inner Mongolia are getting increasingly more comparable, both being affected by national and local policies directed at pastoralistsFootnote64.

At the same time, it is also noticeable that different policies in Outer and Inner Mongolia after 2000 produced the same result. The two of them were affected by the similar economic conditions of significant investment from outside the pastoral societies. This is the case for the emergence of suburban areas, although remote areas still account for over 90% of both Inner and Outer MongoliaFootnote65.

4. About this special issue

The purpose of this special issue, “Policy Related Environmental Disaster and the Socio-Cultural Impacts in Mongolia,” is to discuss the socio-ecological conditions, under both stable and volatile settings, from the local community level to the larger Northeast Asian contexts. The pastoral economy in Mongolia has traditionally provided people with a source of livelihood and a cultural identity. Although there is no denying the importance of the historical-ethnographic approach, a study on environmental disasters would be a useful guide to comprehend its contemporary dynamism, including pastoral resilience and vulnerabilities. Pastoralism was industrialized during the socialist regime, and related policies have transformed it in many fields. Additionally, the development of energy resources sustaining the Mongolian economy drastically affected the sustainability of the rural community in the socialist era. Changes such as the collapse of the socialist regime, China’s influence, and climate change have further transformed Mongolia in the past fifty years. The government’s response to these changes led to the introduction of policies, some of which were more reasonable than others, that fostered environmental changes and disasters. Ethnographic research by anthropologists and sociologists identifies these issues and examines local and regional correlations. The aim of this special issue is to uncover the interactions among policy, environment, and culture in Mongolia and beyond.

The first introductory paper, “Environmental disaster in Mongolian modern history,” by Ozaki Takahiro and Hiroki Takakura, provides the framework of environmental disasters in Mongolian modern history. It highlights the key concepts that signify the social conflict in human and environmental interactions, and emphasizes the failure of human actions. While the authors explore the features of local disasters in 20th-century history, they also argue how disaster and the corresponding policies affect the pastoral society by identifying two types of rural landscapes that make disaster recovery difficult.

The second paper, “Dzud and the industrialization of pastoralism in socialist Mongolia,” by Takahiro Tomita, critically investigates the archetypal Mongolian natural disaster called dzud, which leads to the loss of livestock during extreme winters, from a long-term perspective. Earlier researchers have discussed dzud in the context of post-socialist democratization and recent climate change, but Tomita examines the historical socio-economic background. Although the socialist regime, during its term, successfully concealed the damage caused by dzud from the public by manipulating national statistics, this paper uncovers the issue by focusing on local districts and communities. Tomita traces the industrialization of animal husbandry, focusing on the demand for livestock from domestic and foreign urban markets in the socialist era. This demand altered the pastoralists’ behavior toward breeding livestock – by beginning to focus on sex, age, herd structure, and type. Herders began to reduce the number of castrated males, while they increased the number of adult female cattle and young livestock in their fold. These behaviors resulted in an increase in their vulnerability to dzud. The recent dzud disaster was more the result of socialist policies and the corresponding practices of herders’ than that of a natural hazard.

The third paper, “Negotiating the coexistence of mining and pastoralism in Mongolia,” by Byambajav Dalaibuyan, describes the complex aspects of the mining industry, administration, and local communities, whose collaboration is the basis for sustainable development in Mongolia after the collapse of the socialist regime. The author describes the recently established juridical institute, the local level agreement (LLA), related to sustainable development of mining in Mongolia, which explores conditions for the success of local pastoral communities. The mining industry began during the socialist era with strong initiatives from the government, but with the local pastoralists holding a peripheral position. Dalaibuyan investigates the changes in the legal framework correlated to the emergence of the post-socialist civil society. He emphasizes how continuous negotiation and multilayered stakeholder involvement can lead to mutual trust and sustainable development of mining for pastoralists. Nevertheless, the idea of introducing the LLA was derived from the conflict between the indigenous peoples of Canada and Australia and the respective mining industries in those places. The case study investigates the Mongolian context, but it inevitably correlates it with the global trends in the mining industry.

The last paper, “Forest-steppe fires as moving disasters in the Mongolian-Russian borderland,” by Mari Kazato and Battur Soyollkham, highlights transboundary disasters and adaptations on a local scale. As this introduction reveals, conventional studies on disasters in Mongolia have primarily focused on dzud as a domestic phenomenon related to the environment and pastoralism. In contrast, forest-steppe fires spread across state borders. While studies have observed it on a macro-scale from Russia to China and Japan, they have inadvertently overlooked the local impact of these fires on Mongolia. The authors clearly explain the reason fire hazards have disastrous impacts on local pastoral societies in relation to the season of the outbreak and the subsistence calendar of animal husbandry. In addition, they describe the countermeasures taken by the local government and people against these fires, particularly the ecological knowledge and practice of backfire to protect pasture land, which is a unique ethnographic contribution in this field. Finally, they compare the impact of the fires on Inner Mongolia, with its higher population density and industry, and Outer Mongolia, proving that natural hazards differ according to the socio-cultural and economic conditions.

Photo 1. Chinese ox-wagon team at the Riverside of Nugas Gol, July 121931.

These papers, therefore, examine how policies and local socio-cultural behaviors mediate the impact of disasters, from both historical and contemporary perspectives. The editors of this special issue hope that all the papers renew interest in the historical depth of the traditional human-environmental interaction of Mongolian pastoralists with the complex institutional policies. Additionally, this special issue provides a new perspective on Northeast Asian environmental politics.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes for Humanities (NIHU) Transdisciplinary Project “Northeast Asia AREA Studies.” The international collaboration between Mongolia and Japan scholarship enables the implementation of this special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Takahiro Ozaki

Takahiro Ozaki is a cultural anthropologist and has been carrying out research about Mongolian pastoralists’ strategies in pastoralism, focusing on their diachronic change from 1990s to now, which is mainly caused by the penetration of the market economy in pastoral societies.

Hiroki Takakura

Hiroki Takakura is a social anthropologist studying Northeast Asian ethnography. He has been engaging in disaster studies related to the Arctic Climate Change and to the 3.11 Japan earthquake and tsunami.

Notes

1. Hoffman and Oliver-Smith, Catastrophe & Culture, 23–47.

2. As described, this special issue mainly discusses the situation of Outer Mongolia. However, the paper of Kazato and Soyollkham partly refers to the situation of Inner Mongolia. Therefore, this paper also refers to the situation of Inner Mongolia as a comparison example.

3. Undarmaa et al., Rangeland Ecosystems of Mongolia, 126–127.

4. Ibid., 82.

5. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 59–62.

6. Vreeland, Mongol community and kinship, 37–38.

7. Ibid., 35, 101–103; Toshimitsu, “Mongol ni okeru kachiku,” 154–156.

8. Kashiwabara and Hamada, Mouko chishi, 288.

9. Goto, Mouko no yuboku shakai, 231–265; and Institute of History, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Mongol shi, 273–278.

10. Matsui, Yuboku to iu bunka, 19–25, 92–94.

11. Burensain, Kingendai ni okeru Mongol, 157–159; and Vreeland, Mongol Community and Kinship, 114.

12. Shinoda, “Evolving a Multi-hazard Focused,” 73.

13. Sneath, “Spatial Mobility and Inner,” 269–273.

14. Shinoda, “Evolving a Multi-hazard Focused,” 81.

15. Natsagdorj, “Some Aspects of Assessment,” 4.

16. Komiyama, “Actual Damage to Mongolian,” 74–75.

17. Shinoda, “Evolving a Multi-hazard Focused,” 89.

18. Sneath, “Spatial Mobility and Inner,” 225–227.

19. Ibid., 222–225. Simukov’s original article was included in his writings which was newly published by National Museum of Ethnology as an e-publication. (Simukov, “Materialy po kochevomu bytu,” 472–473)

20. Kashiwabara and Hamada, Mouko chishi, 1077–1082.

21. Oka, “Mongol ni okeru chihou,” 209–233.

22. Tayama, Shindai ni okeru mouko, 232–233.

23. Vreeland, Mongol Community and Kinship, 17.

24. Hagihara, “Paradigms of the Mongol,” 216.

25. Institute of History, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Mongol Shi, 299–317.

26. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no Bokuchiku, 29–30, 66–68.

27. Sneath, “Spatial Mobility and Inner,” 231–232.

28. Ibid., 225–232.

29. Kashiwabara and Hamada, Mouko chishi, 560–561.

30. Jebtsundamba Khutughtu VIII was the most important person in Oouter Mongolian Buddism who became Bodg Haan, after the disposal of Qing emperor as Mongolian haan.

31. Sonomdagwa, Mongol ulsyn zasag zahirgaany, 163–164.

32. Jamsran, Dariganga, 17.

33. Komiyama, “Actual Damage to Mongolian,” 76–77.

34. Abaga Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui, Abaga qizhi, 36.

35. Outer Mongolia’s official name was “Mongolian People’s Republic” from 1924 to 1992.

36. Mining development started from the 5th five-year plan of 1970. For example, Erdenet’s copper and molybdenum mine started digging at 1973. (Yasuda, Mongol keizai nyumon, 48, 55–57)

37. Sneath, “Spatial Mobility and Inner,” 230–232.

38. Komiyama, “Actual Damage to Mongolian,” 76.

39. Sneath, “Spatial Mobility and Inner,” 78–83.

40. Li et al., “Changes in the Nomadic,” 65–68.

41. For example, livestock loss rate in Bogd-uul county of Abaga banner was as high as 91.95%, which was the 4th worst among the counties of Abaga banner. (Meng, Dianxing caoyuan chumuye ji, 81).

42. Meng, Dianxing caoyuan chumuye ji, 9.

43. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 29–30, 169–172.

44. Fernandez-Gimenez, “Sustaining the Steppes,” 335; and Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 76–77, 111.

45. Fernandez-Gimenez, “Reconsidering the Role of,” 17.

46. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 71–76.

47. While Russia has been continuing to import raw meat (including livestock) from Mongolia after the collapse of USSR, China started to import only heat-treated meat from Mongolia as late as 2015. (JICA Office in Mongolia, Newsletter: March 2016, 1.)

48. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) called this phenomenon “mass exodus”. (OCHA, Mongolia Dzud Appeal, 5.)

49. Tsogt et al., Tsag agaarin gamshigt uzegdel, 2–4.

50. Ibid., 66–68.

51. According to the local official, the blizzard occurred in a belt-like area with just 30–50 km width including Berh and nearly half of the livestock died in the suburban area. (Ozaki, “Analysis on a Report,” 21–22.)

52. Nakamura, “Lessons and Prospects of Research on Herders’,” 104.

53. OCHA, Mongolia Dzud Appeal, 15.

54. Sternberg, “Unravelling Mongolia’s Extreme Winter,” 79.

55. Ibid., 83.

56. Fernandez-Gimenez et al., “Cross-boundary and Cross-level Dynamics,” 847.

57. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 267–269.

58. Shinejilt, “Chugoku seibu henkyo to,” 18–19. On the other hand, Mongolian pastoralists tended to attribute the cause of degradation of pasture to sedentary pastoralism which went against their cultural tradition, as well as cultivation which prevailed in inner Mongolia during the 20th century and made the pastoral area narrower. (Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 268–269)

59. Banning of grazing outside introduced by local government varies in duration, from all-year to seasonal such as in winter. (Nemekhjargal, “Uchi Mongol jichiku ni,” 33–34.)

60. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 270–273.

61. See note 42 above.

62. Ozaki, Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku, 374–380.

63. Ibid., 291–316.

64. Ibid., 396.

65. Ibid., 394–395.

Bibliography

- Abaga Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui. Abaga qizhi (Topograohy of Abaga Banner). Hohhot: Neimenggu renmin shubanshe, 2001.

- Batoyun, T., et al. “Who Is Making Airag (Fermented Mare’s Milk)?: A Nationwide Survey on Traditional Food in Mongolia.” Nomadic Peoples 19, no. 1 (2015): 7–29. doi:10.3197/np.2015.190103.

- Bedunah, D., and S. Schmidt. “Rangelands of Gobi Gurvan Saikhan National Conservation Park, Mongolia.” Rangelands 22, no. 4 (2000): 18–24. doi:10.2458/azu_rangelands_v22i4_bedunah.

- Burensain. Kingendai ni okeru Mongol jin noko sonraku shakai no keisei (The Formation of Mongolian Peasant Village Society in Modern Age). Tokyo: Kazama shobo, 2003.

- Fernandez-Gimenez, M. E. “Reconsidering the Role of Absentee Herd Owners: A View from Mongolia.” Human Ecology 27, no. 1 (1999a): 1–27. doi:10.1023/A:1018757632589.

- Fernandez-Gimenez, M. E. “Sustaining the Steppes: A Geographical History of Pastoral Land Use in Mongolia.” The Geographical Review 89, no. 3 (1999b): 315–342. doi:10.2307/216154.

- Fernandez-Gimenez, M. E., B. Batkhishig, and B. Batbuyan. “Cross-boundary and Cross-level Dynamics Increase Vulnerability to Severe Winter Storms (Dzud) in Mongolia.” Global Environmental Change 22 (2012): 836–851. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.

- Goto, T. Mouko no yuboku shakai (Nomadic Society of Mongolia). Tokyo: Seikatsusha, 1942.

- Hagihara, M. “Paradigms of the Mongol Study: About the Teachings of TO-WANG: Teaching about the Nomadic Life in Khalkha-Mongolia during the 19th Century.” Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology Special, Issue 20, no. 1999 (1999): 213–285. doi:10.15021/00003525.

- Hoffman, M., and A. Oliver-Smith. Catastrophe & Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 2002.

- Institute of History, Mongolian Academy of Sciences. Mongol Shi (History of Mongolian People’s Republic). Vol. 2. translated by H. Futaki, H. Imaizumi, and K. Okada. Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1988.

- Jamsran, L. Dariganga. Ulaanbaatar: No Publisher, 1990.

- JICA Office in Mongolia. Newsletter: March 2016. Ulaanbaatar: JICA Office in Mongolia, 2016. https://www.jica.go.jp/mongolia/office/others/ku57pq00000ryrvg-att/newsletter_201603.pdf

- Kashiwabara, T., and J. Hamada. Mouko Chishi (Topography of Mongolia). Vol. 3. Tokyo: Fuzanbo, 1919.

- Komiyama, H. “Actual Damage to Mongolian Animal Husbandry Due to 2000-2002 Dzud Disaster.” Bulletin of JAMS 35 (2005): 73–85.

- Li, O., R. Ma, and J. R. Simpson. “Changes in the Nomadic Pattern and Its Impact on the Inner Mongolian Steppe Grassland Ecosystem.” Nomadic Peoples 33 (1993): 63–72.

- Matsui, T. Yuboku to iu bunka (The Culture of Nomadism). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2001.

- Meng, S. Dianxing caoyuan chumuye ji “sanmu” wenti yanjiu (Research of Pastoralism in a Typical Pasture and Three Problems in Pastoralism). Hohhot: Neimenggu Jaoyu Chubanshe, 2011.

- Nakamura, H. “Lessons and Prospects of Research on Herders’ Adaptive and Recovery Behavior to Natural Disasters: Case of Dzud in Mongolia.” Journal of JAALS 29, no. 3 (2019): 103–113.

- Natsagdorj, L. “Some Aspects of Assessment of the Dzud Phenomena.” Papers in Meteorology and Hydrology 23, no. 3 (2001): 3–18.

- Nemekhjargal. “Uchi Mongol jichiku ni okeru “kinboku” seisaku ni kansuru ichi kousatsu (A Discussion about the Policy for Banning of Grazing outside in IMAR).” Asia daigaku daigakuin keizaigaku kenkyu ronshu 30 (2006): 23–48.

- Nishiaki, Y., H. Mikuni, and Y. Ogawa. Catalogue of the Namio Egami Collection, Part 1: Inner Mongolia. Tokyo: The Unversity Museum, The University of Tokyo, 2011. http://umdb.um.u-tokyo.ac.jp/DKoukoga/Inner_Mongolia/top.php

- Oka, H. “Mongol ni okeru chihou shakai no dentouteki kousei tan’I otog, bag ni tsuite: Mongol koku Hentii aimag, Galshar sum chosa hokoku (A Discussion about Otog and Bag Which Was Traditional Units of Local Society in Mongolia: A Research Report of Galshar Sum, Hentii Aimag, Mongolia).” Mongol Kenkyu Ronshu: Tohoku Daigaku Tohoku Asia Kenkyu Center, Mongol Kenkyu Seika Hokoku 1 (2002): 209–233.

- Ozaki, T. “Household, Kinship and Local Community.” In Mongol No Kazoku to Community Kaihatsu (Family and Community Development in Mongolia), edited by M. Shimazaki and K. Nagasawa, 51–73. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyosonsha, 1999.

- Ozaki, T. “Analysis on A Report of Natural Disaster in Mongolia: A Case Study of Storm (Shuurga) in May 2008.” Kadai Shigaku 57 (2010): 9–23.

- Ozaki, T. “Kousa hasseiiki deno hitobito no kurashi to sabakuka (Peoples’ Lives and Desertification in Generating Areas of Dust Storm).” In Kousa: kenkou, seikatsu kankyo heno eikyo to taisaku (Dust Storm: Effects and Countermeasures to Health and Life Environment), edited by Y. Kurosaki, Y. Kurozawa, M. Shinoda, and N. Yamanaka, 27–36. Tokyo: Maruzen, 2016.

- Ozaki, T. Gendai Mongol no bokuchiku senryaku: taisei hendou to shizen saigai no hikaku minzokushi (Pastoral Strategies in Modern Mongolia: Comparative Ethnography of Regime Transformation and Natural Disaster). Fukyosha: Tokyo, 2019.

- Shinejilt. “Chugoku seibu henkyo to “Seitai Imin” (Chinese Western Frontier and “Environmental Migration”).” In Chugoku no kankyo seisaku: seitai imin (Environmental Policy in China: Environmental Migration), edited by Y. Konagaya, Shinejilt, and M. Nakao, 1–32. Kyoto: Showado, 2005.

- Shinoda, M. “Evolving a Multi-hazard Focused Approach for Arid Eurasia.” In Climate Hazard Crises in Asian Societies and Environments, edited by T. Sternberg, 73–102. Oxford: Routledge, 2017.

- Simukov, A. D. “Materialy po kochevomu bytu naseleniia MNR. II: Kochevki Ubur-Khangaiskogo aimaga MNR (Materials on the Nomadic Life of the Population in Mongolian People’s Republic. II: Nomads of Ovorhangai Province in Mongolian People’s Republic).” In A. D. Simukov Works about Mongolia and for Mongolia, edited by Y. Konagaya, S. Bayaraa, and I. Lkhagvasuren, 470–479. Vol. 2. Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology, 2007. doi:10.15021/00008740.

- Sneath, D. “Spatial Mobility and Inner Asian Pastoralism.” In The End of Nomadism? edited by C. Humphrey and D. Sneath, 218–277. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Sonomdagwa, T. Mongol ulsyn zasag zahirgaany zohion baiguulalyn o’orchilol (Change in Composition of Administrative System). Ulaanbaatar: Shinechlel, undesnii arhibyn gazar, 1998.

- Sternberg, T. “Unravelling Mongolia’s Extreme Winter Disaster of 2010.” Nomadic Peoples 14, no. 1 (2010): 72–86. doi:10.3167/np.2010.140105.

- Tayama, S. Shindai ni okeru mouko no shakai seido (Mongolian Social System in Qing Dynasty). Tokyo: Bunkyo Shoin, 1954.

- Toshimitsu, Y. “Mongol ni okeru kachiku yotaku no kanko ((Custom of Livestock Entrustment).” Shirin 69, no. 5 (1986): 140–164.

- Tsogt, J., T. Monhjargal, and D. Sukhbaatar. Tsag agaarin gamshigt uzegdel (Meteorological Disaster Event). Ulaanbaatar: Ontsgoi Baidlin Yoronhii Gazar, 2008.

- Undarmaa, J., K. Tamura, L. Natsagdorj, and N. Yamanaka, eds. Rangeland Ecosystems of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar: Munhiin Useg, 2018.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Mongolia Dzud Appeal. New York: United Nations, 2010. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/B116C168D22EBC9CC1257720004C8A4D-Full_Appeal.pdf

- Vreeland, H. H. Mongol Community and Kinship Structure. New Haven: HRAF, 1953.

- Yasuda, O. Mongol keizai nyumon (Introduction of Mongolian Economy). Tokyo: Nihon Hyoronsha, 1996.