ABSTRACT

Introduction

The relationship between mining developments and local communities has been highly contested. The role of the local population in Mongolia, which is largely comprised of herder households and communities, has not been adequately recognized in government mining policy and regulations. Since 2006, mining project proponents are required to establish local level agreements (LLAs) with local host governments in Mongolia.

Objective

This paper examines how agreement mechanisms have been implemented and whether they have helped local communities protect their interests while coexisting with mining.

Methods

The paper draws on a multi-year study on LLAs in Mongolia carried out by the author between 2013 - 2018.

Results

As the Mongolian case demonstrates, legal prescription by itself will not deliver the desired outcomes of greater benefits for local communities or improved relations between these communities and developers. The negotiation of coexistence of mining and pastoralism requires iterative, multilayered processes involving the communities affected by the project. Unless the rights and claims of project-affected pastoral communities are recognized in the LLA regulations, their meaningful participation in agreement-making will remain limited.

1. Introduction

The competition and conflicts between Mongolia’s two key economic sectors over the exploitation of natural resources has been a vexing concern, especially over the last two decades. Mongolia’s mining sector has grown significantly in this time, adding stress to the pastoral economy, which has been affected by degraded pastures and increased climate hazardsFootnote1. Border closures and suspended mineral exports during China’s lockdown in early 2020 had a significant impact on Mongolia’s export earnings. This demonstrated both the economic importance and volatility of revenue from the mining sector, especially from a few large-scale coal and copper minesFootnote2. However, the pandemic had less impact on traditional livestock husbandry than on other economic activities, highlighting the role of livestock husbandry in ensuring the sustainability of livelihoodsFootnote3.

Mining activities alter the host environment and often exacerbate preexisting vulnerabilities, especially in jurisdictions where the government is unwilling or unable to safeguard against severe social and environmental externalitiesFootnote4. Research on mining activities, including large-scale, artisanal, and small-scale mining has reported negative impacts on air quality or dust, water resources, land or pasture availability, as well as on the livelihoods and well-being of Mongolian pastoralistsFootnote5. Conflicts between miners and pastoralists over the use and control of land and water resources, as well as grievances about the distributive and procedural fairness, have increased in frequency since the early-2000sFootnote6. Known as the River Movements, Mongolia’s first environmental movements were organized by semi-nomadic pastoralists to confront the fast expansion of mining activitiesFootnote7. Local NGOs and donor organizations advocated amendments to national laws and regulations, in addition to international voluntary codes of practice, in order to avoid mining-community conflicts, reduce negative impacts, increase local development benefits, and support sustainable livelihoods in local communities. Agreement-making between mining companies and “host” local governments was one of the policy interventions adopted by the Mongolian state. This was in parallel with developments in other mining economies where local level agreements, known under a range of terms such as Impact Benefit Agreements and Community Development Agreements, emerged as an important new form of governance. In Australia and Canada, it is now standard practice for legally binding agreements to be negotiated between Indigenous communities and resource companies from the early stages of exploration. Numerous examples of LLAs in various forms can also be found in countries as varied as Papua New Guinea, Ghana, Russia, Peru, and the Philippines. Though the uptake of LLAs in Mongolia has been inconsistent, some large-scale mining projects, such as Oyu Tolgoi Mine, Tavantolgoi Mine and Khushuut Mine, along with many other mining and mineral exploration companies have established LLAs in the past decade.

This paper contributes to a growing body of literature on the opportunities and limitations for the participation of pastoralists in project-specific negotiations and dialogue processes in Mongolia. Recent research has explored frameworks for conflict resolution between miners and pastoralistsFootnote8, the role of transnational institutions and norms in protecting pastoralists’ rightsFootnote9, and effects of corporate approaches to building good community relationsFootnote10. Although LLAs are one of a few mechanisms available to local mining-affected communities for negotiating their terms of coexistence with mining, it has not been examined systematically or in conjunction with the above-mentioned literature. By exploring the historical context of this mechanism, analyzing its use in project-specific negotiation processes, and engaging with previous research, this paper informs of the current development of strategies for promoting dialogue between mining and pastoralism, better agreement-making practices in Mongolia and, by extension, in other emerging mining economies.

The paper draws on a multi-year study on the negotiation of an agreement (“Oyu Tolgoi Umnugovi Cooperation Agreement”) between the Oyu Tolgoi mine and local stakeholders in the Umnugovi aimag (province) between 2013 − 2015. It also draws on corollary research on local level agreements (LLAs) in Mongolia carried out in the same period, as well as a further study undertaken in Mongolia by the author in between 2017–2018. The author, who at the time was an independent researcher attached to a university-based research institute, had access to observe negotiation meetings of the Oyu Tolgoi Cooperation Agreement. In this capacity, he conducted in-depth, iterative interviews with key personnel who were involved in these negotiations.

In the next section, this paper sets the scene for the following discussion by highlighting the role of pastoralists in Mongolia’s mining regime. In the subsequent sections, this paper will: (a) present quantitative data on LLAs “on the ground” experience in Mongolia and address the question on how these agreements have been utilized; (b) provide two short case studies as illustrations of the different circumstances in which LLAs have been adopted; (c) examine the case of the negotiation and implementation of LLAs established between Oyu Tolgoi Mine and local governments and communities in the South Gobi.

2. Local level agreements in the mining industry

Over the last two decades, LLAs between companies and proximal, often land-connected, communities have emerged as an important form of governance in the global mining sectorFootnote11.

Negotiated agreements between mineral project proponents and project-affected communities and their representatives first emerged and became standard in Canada and Australia. Agreements between Indigenous peoples and project proponents in these countries were born out of a history of conflict, and have been negotiated extensively over the past three decades. Consequently, these two countries have provided significant research and practical expertise in agreement-making. The idea of negotiated arrangements with local stakeholders in mining as good practice began diffusing into international academic and policy discourse communities when major international initiatives were first adopted in the early 2000s to address sustainable mining development.

Three main overlapping rationales have been put forward for promoting the use of LLAs: (a) to reduce the risk of conflict by ensuring that contentious issues are identified and addressed through agreed processes, and that there is local support for a project going ahead; (b) to provide a vehicle for delivering economic and other benefits to impacted communities; and (c) to give developers, communities, and in some cases governments, greater certainty about the commitments and obligations of the other signatoriesFootnote12. There is a growing body of literature and evidence from international practice which indicates that, under appropriate conditions, LLAs can contribute to economic, environmental, and cultural sustainability for host communities. It can do so by increasing local governance participation and benefits from development, with a commensurate reduction in mining related conflictsFootnote13.

The literature is expanding to explore the challenges and issues that can arise in harnessing the potential of LLAs, such as asymmetry of information and capacity between the agreement parties, women’s participation, and general implementationFootnote14. Some recent research has also investigated the contextual factors – social, legal, and institutional – that contribute to or inhibit effective agreementsFootnote15. In the Russian Arctic, a number of factors such as companies’ compliance with international financial institutions, regional frameworks for indigenous rights, and local communities’ collective activism, affect how local benefit-sharing agreements are negotiated and implementedFootnote16.

3. Mongolia’s mining regime and the role of pastoralists

Large-scale exploration and mining operations commenced in Mongolia in the 1970s and were mostly supported by the Soviet Union and other Comecon countries. Consequently, copper and coal became major sources of export revenue in the 1980s, accounting for approximately 40% of Mongolia’s total exportsFootnote17. In the post-socialist period, Mongolia experienced a severe economic crisis. Attracting private sector participation in mining activities, particularly in “quick-to-production gold mines,” was a key target of the Mongolian government’s investment policy. The new pro-reform government that formed in 1996 developed a new Minerals Law as part of its economic liberalization policy. The following five years (1997 − 2001) saw a 17-fold increase in the number of exploration licenses issued by the Mongolian government. This exploration boom led to the development of many new mining projects in Mongolia, which also correlated with the rapid industrialization and urbanization in China and the corresponding demand for raw materials. The global commodity boom, fueled by China’s industrial expansion, enabled Mongolia to enjoy high mining-driven economic growth rates starting with the mid-2000sFootnote18.

Pastoralists were of peripheral importance in mining policy decision-making. In the socialist era, mines were developed according to the government central planning processes and, for larger scale mines, in response to the supply and demand for minerals within the socialist bloc. In the centrally planned economy, mines were developed as economic and administrative institutions. Erdenet, the second largest city in Mongolia, and several towns were developed as part of the mining development during the socialist era. The construction of mines, satellite towns, and new settlements were celebrated as the culmination of social progress, collectivism, and a new way of life within the nation previously defined by nomadic culture. The state gradually surrendered its authority as a central planner in the post-socialist era. However, the role of local governments and pastoralists in decision-making regarding mineral resources remained of secondary importance.

Pastoralists’ access to pasture land as a shared resource is defined by customary land tenure arrangements at the local level. Consequently, the bulk of grazing lands, as well as surface and ground water, are subject to government ownership and non-exclusive use. Moreover, when mining and other rights are granted to project proponents, herders do not have exclusive rights. The Minerals Law of 1994 and 1997 did not require government agencies and project proponents to provide any prior notice or consultation activities before the issuance of exploration and mining licenses. The Law on Environmental Impact Assessment approved in 1998 required the “opinions of residents in the project area to be attached to a detailed environmental impact assessment,” but did not specify any consultation procedures or what “opinions” entailed.

In the post-socialist era, the paternalistic role of the state was no longer viable in the mining context. Many state-owned enterprises, including mines, faced financial difficulties and were fully or partially privatized in the 1990s. In the absence of investments, many remote state-owned mines shrunk significantly and often ceased to operate. Private mining companies operating in the 1990s were mostly small and medium-sized Mongolian, Chinese, and Russian gold mining companies, and showed no interest in building good relationships with traditional land users or pastoralistsFootnote19. More importantly, as private businesses, they did not seek to build mines as economic and administrative institutions. Acknowledgment and recognition of, much less compensation for, pastoralists’ land rights were limited. Outdated technology and weak government monitoring could not avoid serious negative environmental impacts in many localities, especially the degradation of many rivers, creeks, and springs. Pastoralists in mining-affected areas generally had no voice in the matter and were powerless in making it ceaseFootnote20. In the mid-2000s, pastoralists’ resistance movements, the River Movements, emerged nationwide in response to the threats to the local environment and livelihoods posed by miningFootnote21. These movements advocated for a new law that would prohibit mineral exploration and mining activities in river headwaters and forest reserves, which was ultimately enacted in 2009.

In parallel with local resistance, at the onset of a global mining boom, the adequacy of existing legal and policy frameworks to secure fair economic benefits for the country, especially from large-scale mining projects, became a key political issue. Under growing public pressure, the Mongolian Parliament passed a new Minerals Law in 2006, reinstating certain powers of intervention of the state in the organization of the mining sector, including local governmentsFootnote22. Under the new Minerals Law, the Minerals Resources Authority of Mongolia (MRAM) is obligated to provide written notice of an exploration license application to aimag (provincial) governors, requesting formal approval. The governor’s response to the MRAM request for consent normally requires consultation with the Citizens Representatives’ Khural (CRK) of the respective aimag and “host” soums within 30 days. Thus, the new law provides local governments, particularly the aimag government, with the means to influence the central government’s decisions regarding resource development. However, the law did not change the lack of participation of project-affected local population in the government’s decision-making process on mineral exploration and mining.

The discussion of the new Minerals Law provided an opportunity for local NGOs to launch an advocacy campaign for a mandatory requirement for local authorities to negotiate Participation Agreements with companies as part of the mine licensing process. Local NGOs presented the Participation Agreements as international good practice that had proven to be effective for promoting local community participation in the approval process of resource development projects. They argued that agreements would help avoid the negative impacts on the rights and livelihoods of pastoralists. The Mongolian parliament approved the requirement for the Participation Agreements recommended by the NGO in 2006, along with other amendments to the Minerals Law. However, the initial intention of the NGOs to mandate the Participation Agreements to support community approval in mining was not substantiated. The vague provision of Article 33 of the previous law, that required mine license holders to coordinate their operation with local administrations, was extended into Article 42 of the new law. This new law stated: “A license holder shall work in cooperation with the local administrative bodies and conclude agreements on issues of environmental protection, mine exploitation, infrastructure development in relation to the mine-site development and job creation.” (42.1)

While the original intention of the Participation Agreements advocated by local NGOs in 2006 was to ensure that local project-affected populations were consulted and involved in decision-making processes on resource development projects, the Minerals Law highlighted only benefit-sharing. The state has primarily promoted LLAs as a mechanism to smooth state-investor relations and as a way to delegate its authority to manage socio-environmental and redistributive claims onto mining companiesFootnote23. This has been evident in subsequent efforts by local NGOs and some legislators to make LLAs more effective by linking them with other key legal and institutional arrangements for the mining sector. An attempt was made in 2014 to include a statement into the State Policy on the Mining Sector of Mongolia (2014–2024), a guiding document for legislative reforms. This statement expressed that, in order to support local development, mining companies and local governments should enter agreements in a transparent and participatory manner. However, this initiative failed to gain support during ensuing parliamentary discussions. Furthermore, a Model Agreement was approved by the Mongolian government in March 2016. The Model Agreement focused on the scope of agreements in accordance with the Minerals Law. On the process of agreement-making, the Model Agreement recommended establishing a Cooperation Committee, comprised of 9 members representing local populations, to monitor the negotiation and implementation of agreements. While the Model Agreement has been used as a starting point in some aimags and soums, in many cases it is not referenced by local governments at all. Once more, the state has been “strategically absent” in establishing mechanisms or institutions empowered or equipped to oversee local level agreement processes, leaving local project-affected communities with little recourseFootnote24.

4. Current LLA practice in Mongolia

The only consolidated public source of information about agreements and contracts between mining companies and local authorities are the annual Mongolian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) reports which, since 2011, have included a section on LLAs. In 2011, 149 of the 200 companies that responded to an EITI questionnaire reported that they had agreements with local governments. In most cases, however, these were simple contracts setting out payments for the use of water and land. Only the titles of 11 agreements (reported by 10 companies) referred to cooperation. , which is sourced from the EITI annual reports for the years 2011–16, points to a slight increase in the number of LLAs being reported over these years. The Table further shows that most LLAs in Mongolia are: (a) established between mining project developers rather than exploration companies; (b) prevalent in soums rather than aimags; and (c) of relatively short duration, typically a year or less.

Table 1. LLAs reported in the Mongolian EITI reports (2011–2016)

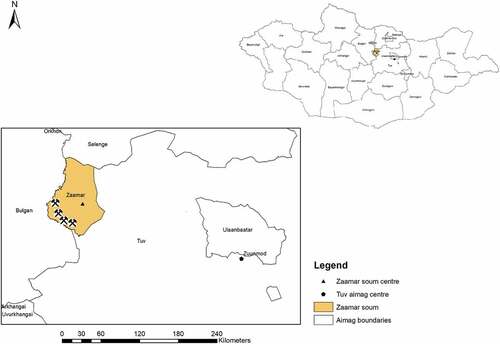

Further analysis of the data indicates a marked geographical concentration in the distribution of LLAs. In 2016, there were 2021 valid exploration licenses and 1558 valid mining licenses in force, distributed across 250 soums (76% of all soums in Mongolia) (M.EITI, 2017). However, the great majority of these soums were not parties to a LLA, nor were the aimags in which they were located. In fact, 60% of the LLAs listed in the EITI reports were established in just four aimags (Tuv, Bulgan, Dornogovi, Khentii). Another 30% of the listed LLAs reports were established in two neighboring soums, (the Zaamar soum of the Tuv aimag and the Buregkhangai soum of the Bulgan aimag).

As noted, aimag governments have been less engaged in LLAs. Analysis of 19 LLAs involving aimag governments, either as bipartite or tripartite agreements, confirms two patterns. First, some aimag governments became major beneficiaries of relatively large-scale or regionally significant resource projects, such as the giant copper-gold project of Oyu Tolgoi in Umnugovi aimag and the large coal mine in Khovd aimag in the far west of the country. Second, according to interviews with local government representatives during fieldwork, some aimag governments, such as Bayankhongor and Dornogovi, took a proactive, top-down approach, encouraging or insisting that companies, regardless of their project type and size, enter LLAs in order to secure local benefits. In practice, the top-down approach has tended to provide companies with little help in establishing and securing good relationships with host soum and local communities. This was a result of a lack of commitment and capacity of the aimag governments to involve these other actors in the LLA process and outcomes. In a small number of cases, this issue has been addressed via tripartite agreements (aimag, soum, company), as demonstrated by the Khushuut case discussed in the next section. Another important issue arose in the case of those aimags where there were many small to medium-sized resource projects. LLAs were established extensively without adequate preparation by some aimag and soum governments which hosted many resource projects. For example, 40 LLAs were signed in just one day in the Dornogovi aimag in 2015, according a local government representative.

It was clear from the interviews conducted with various “key informants” that, in many cases, neither local governments nor companies saw a strong business case for entering into an LLA. Companies, for their part, have mostly viewed LLAs as a government imposition and an additional cost to be avoided, if possible. Some local level governments seem to regard LLAs as useful for extracting commitments from companies, but this is far from a universal view. The national government has also demonstrated a definite ambivalence about LLAs, as evidenced by its reluctance to take steps to strengthen the legislation, as well as the lack of initiatives to promote the use of LLAs. The lack of transparency regarding the process whereby agreements have been reached and the content of these agreements have also been an issue.

5. The case of Zaamar and Khushuut mines

Since the 1990s, the Zaamar soum has experienced the environmentally devastating impact of Mongolia’s gold rush (). During the mid-2000s, several thousand artisanal miners and approximately 40 mining companies dug for gold on soum land at the peak of the gold rush, in what is widely regarded as one of the most negative examples of environmental legacy in Mongolia. As a result, the soum government and mining companies operating in the territory have received heightened scrutiny. The issue of adequate rehabilitation of mined land was most frequently raised when the key dimensions of responsible mining activities were discussed with local government officials and community members. According to the soum governor, while some mining companies have shown significant improvements in land rehabilitation, other companies continue to exhibit noncompliance with laws and standards, instigating community grievances and protests against both the soum government and mining companies.

From the soum government’s perspective, Zaamar gained little from the revenue that the central government accrued during the gold rush. The lack of significant benefits from mining on local development, especially the absence of contribution to local social infrastructure and public amenities, has been a serious public grievance in the Zaamar soum. During the gold rush, there were no formal or consistent mechanisms for interacting with mining companies. Instead, mining companies provided money for one-off and sporadic activities requested or demanded by soum government officials, such as donations, public facility renovations, public festive events, scholarships, and aid to poor households.

In 2013, the soum government drafted an LLA template, requiring mining companies to support local infrastructure development and undertake adequate steps for land rehabilitation. Each company was asked to choose a project to support the soum government’s annual plan, which varied according to the mining project scale and company capacity. A range of projects, such as adding an extension to a hospital, installing street lights, building a community center, and establishing a local resort, have been directly implemented by mining companies since 2013. The agreements also enabled the soum’s CRK to conduct biannual reviews of land rehabilitation progress of each mining company operating in Zaamar. Based on the review results, it is then decided whether to continue mining under a LLA with the same companies the following year. The consistent approach of the soum government, applied to all mining companies, places those that decline to negotiate an LLA at a disadvantage.

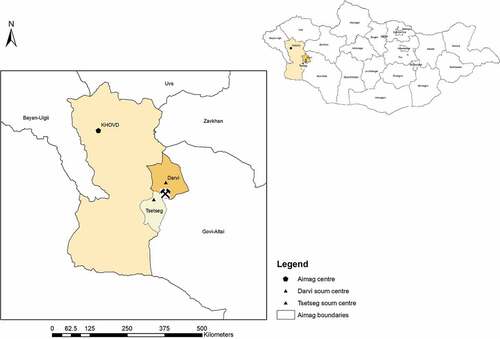

Unlike the case of Zaamar, where multiple small mines established agreements with the soum government, the first LLA of the Khushuut mine was with the Khovd aimag government in 2014 (). The agreement included relatively detailed provisions on local content, annual financial benefits, and local government responsibilities to support operational certainty. Unlike the agreements discussed above, it also contained detailed provisions on agreement breaches, dispute resolution, and the company’s right to refrain from paying the annual financial benefits if there are business interruptions caused by local protests or changes in government policy. These provisions reflect, in part, the company’s need to address two key challenges that the Khushuut project has faced in the past seven years. First, the project has generated considerable political controversy and media attention. It was expected to become one of the largest mining projects in the western region of Mongolia and the first large-scale extractive project for the Khovd aimag. The rapidly growing economy and surging demand for coal from the steel industry in China’s adjacent Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region were the key factors driving investment in Khushuut. This context prompted the national government to seek a direct ownership stake under the Minerals Law provision on strategically important deposits. In response, the company halted operations in 2013, pending clarity regarding the uncertainty created by the government’s equity aspirations.

Secondly, since its inception, the project has encountered considerable interruptions due to protests by local pastoralists, reflecting community grievances regarding the lack of consultation. In response, by 2012, the company had established several narrowly structured agreements with the Khovd aimag, Darvi and Tsetseg soums, and the Khushuut village adjacent to the mine, none of which are in the public domain. Despite establishing these separate agreements focusing on social support and philanthropic programs, the company still faced considerable local community and political opposition. For instance, protests by local pastoralists delayed the company’s exploration project for water to support a power plant and coal washery. The interests of the Khovd aimag administration, which focused on accruing broad regional benefits, in addition to the interests of the soum governments, focusing on tangible infrastructure and local socioeconomic benefits, did not often align.

As the only active development in the region, Khushuut became the largest local private employer and purchaser, creating substantial local livelihood dependence. Consequently, the mining halt and employee layoffs had a major effect on the local economy, placing considerable pressure on the local government to resolve these issues and strike a new agreement. In exchange for the company’s obligations to increase the project’s local content and financial contribution, the aimag government committed to coordinating relations among the soum government, local communities, and the company. It also took the responsibility of jointly managing local grievances and opposition against the Khushuut project. Furthermore, the new agreement persuaded the central government that broad local support for resumed mining existed. Accordingly, the government provided its support for recommencing development without government equity. Unlike the previous agreements, the Khovd aimag administration carried out activities to inform the public about the new agreement and obtain opinions from different parties, including local pastoralists and the Khushuut village, the community most affected by the mining activity. Nevertheless, the company’s commitments and obligations remain broadly defined, and the agreement contains no clear arrangements for addressing the specific concerns of local pastoralists and the Khushuut village.

6. The Oyu Tolgoi mine and negotiation of coexistence

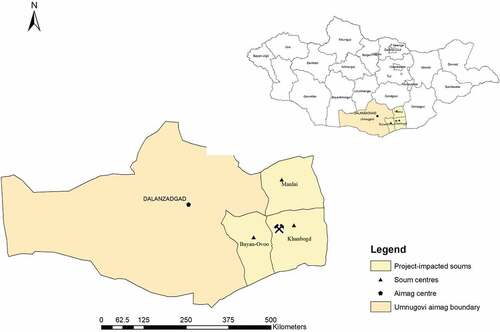

Located in the South Gobi Desert region of Mongolia, approximately 550 km south of the capital city and 80 km north of the Mongolia−China border, Oyu Tolgoi is one of the world’s largest known copper-gold deposits, with an expected mine life of more than 30 years. The Oyu Tolgoi mining project is located within the boundary of the Khanbogd soum ().

In March 2003, the exploration program of the Canada-based Ivanhoe Mines discovered the full extent of Oyu Tolgoi’s reserves and established it as one of the world’s largest copper-gold porphyry systems. In 2006, the global mining corporation Rio Tinto agreed to form a strategic partnership with Ivanhoe Mines to jointly construct and operate the mine complex. The initial national-level investment agreement (IA) for the development of Oyu Tolgoi was signed between the Government of Mongolia and Ivanhoe Mines in 2009. The agreement stipulated that the Government of Mongolia would hold 34% ownership in the development and collect royalties and taxes on mining revenues. It also outlined investments in infrastructure, as well as environmental and employment requirements associated with the project. The IA also contained a section on commitments related to regional development, which required the mining company to inform, compensate, and consult with local citizens directly and indirectly impacted by the Oyu Tolgoi mining project.

Chapter 4 of the Oyu Tolgoi IA is devoted to regional development, wherein the operator is obliged to establish cooperation agreements with local administrative organizations in accordance with Article 42 of the Minerals Law. This requirement was in line with Rio Tinto’s community policy, which defined community agreements as key to gaining a social license to operate. However, the Oyu Tolgoi’s cooperation agreement required a broad scope to incorporate regional (Umnugovi aimag), local (Khanbogd and two other project-impacted soum), and community concerns (directly impacted pastoralists). Unlike the Minerals Law, which confined the extent of the agreement to environmental protection and the mine’s contribution to infrastructure development and local employment, the IA defined the scope of the Oyu Tolgoi cooperation agreement relatively broad. More specifically, it included the establishment of local development and participation funds, local participation committees, and local environmental monitoring committees.

High expectations among local government and population, as well as unmet promises made by the project developers, accumulated since the deposit was discovered in 2001. Among such unmet promises, a particularly cogent one was the project of a town model of the future Khanbogd that developers presented several times, to allegedly win local government and community support more easily. This was in line with the common expectation that the small village of Khanbogd could be completely transformed by the massive mine. One indication of such high expectations from the project was a 2007 open letter from a group of local government and community leaders in Khanbogd, sent to the national government to urge it to continue negotiations with the project’s proponents.

Moreover, when major site development and construction work at Oyu Tolgoi commenced in 2010, inevitably causing significant land disruptions and economic displacement, speculation intensified regarding the project’s impact and benefits for the region and local communitiesFootnote25. While the ways in which the project could benefit the national economy were the focus of the broader discussion, local governments and herders wanted to receive assurance of environmental security and direct benefits. Regarding the project’s local development contribution, a common understanding of large-scale industrial projects during the Soviet era largely remained, viewed as an economic and administrative institution that takes care of the adjacent population. The local government began to express its frustration with the lack of commitment and action on the company’s part to invest in regional and local development. The example of how the city of Erdenet was developed by the Erdenet Mine in the Soviet period was often cited.

For the company, working with local government authorities in a friendly and timely manner was important for obtaining project-related approvals, such as for land and water use, and for avoiding unnecessary bureaucratic delays and community discontent. Moreover, the company was obligated to comply with international financial institutions’ lending standards for managing environmental and social risks, as well as the impacts of mining.

Pastoralists in the Khanbogd soum were the most affected by the Oyu Tolgoi mining operation. Their main concerns included loss and fragmentation of pastureland, increased dust from road traffic affecting animal health, and hazards presented by unfenced or unrehabilitated quarries. The mining project also used brackish groundwater from deep basins that raised concerns over its impact on drinking water. Although Rio Tinto contended that these basins were not connected to the shallow aquifer systems that provided drinking water for people and livestock, the widely shared anxiety among the local community persistedFootnote26.

In 2012, herders in two subdistricts bordering the Oyu Tolgoi mine submitted a complaint regarding adequate compensation for their displacement and resettlement. It was presented to the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), one of Oyu Tolgoi’s international lenders, with assistance from Oyu Tolgoi Watch, a Mongolian NGO based in the capital city. With this complaint unresolved, the group submitted another grievance in February 2013, claiming that the local Undai River system was being severely compromised as a result being diverted. The IFC Ombudsman determined that this complaint met its eligibility criteria, and the dispute resolution process began with a series of meetings between the herders and Rio Tinto representatives, facilitated by independent mediators.

Thus, in parallel with an LLA negotiation, a dispute resolution process facilitated by a CAO mediation team began in August 2013. Several meetings were held between the company’s community relations team and the “Elected Herders Team” (EHT), for which members were elected from each bagh (counties within the soum) to represent the local herders in the Khanbogd soum. The negotiations were at times protracted and difficult, continuing throughout 2014 and 2015. However, they also yielded some tangible outcomes. For example, in September 2013, the parties involved signed an agreement to allow herders’ grazing access to certain parts of the Oyu Tolgoi mining operation. The parties also agreed to engage an independent expert panel to assess the adequacy of the company’s mitigation measures to avoid or reduce the impact on the herders’ pastures, access to water, and water qualityFootnote27. However, pastoralists involved in the CAO process did not perceive these dispute resolution negotiations as part of the regional cooperation agreement process, and there was no engagement from neither the Khanbogd soum, nor the Umnugovi aimag administration.

The final draft of the Cooperation Agreement was signed in April 2015 by Oyu Tolgoi, the Umnugovi aimag, and the Khanbogd soum. Investment in basic social services and physical infrastructure was the main priority of aimag officials, while the company and the soum were more concerned about addressing negative impacts on project-affected local population and ensuring their sustainable livelihoods. As a result of iterative discussions, the agreement prioritized water management, environmental management, traditional animal husbandry and pastureland management, national history, culture, and tourism. It also prioritizes basic social services (e.g., healthcare, education, vocational training, and employment), local business development and procurement, and infrastructure and capital projects. The company is obligated to provide annual financial contributions into a publicly transparent and strongly governed trust fund that considers and finances projects and programs proposed by local authorities, organizations, and community members. Financing decisions require the guidance of a “relationship committee” and the governance of a complementary trust fund board, both of which include aimag, soum, and company representation.

At the same time, the company and local herders were negotiating their differences via the CAO facilitated dispute resolution process. However, numerous meetings between the two parties did not yield an agreement. Local herders involved in meetings expressed disappointment with a lack of outcomes from protracted dispute resolution meetings, while other herders began to question the CAO process. The mine and local community parties realized that the soum government was essential for resolving the disputeFootnote28. In 2015, the Khanbogd soum government joined the parties’ initiative to establish a tripartite council. Prior to this, the soum government established an interim cooperation agreement with the company in 2014 and had strong interest in harmonizing their relationship to increase development benefits. Comprising equal numbers of representatives from the local herders, the soum government, and the company, the tripartite council presented a more sustainable and formal platform for dialogue and dispute resolutionFootnote29. After a joint fact-finding process to assess Oyu Tolgoi’s impact on the livelihoods of the herders and the adequacy of the compensation processes with the assistance of independent experts, the tripartite council reached the final dispute resolution agreement in May 2017. It included additional compensation for project-affected herders, joint projects on protection of pastureland and water, participatory monitoring programs, and other commitments to support the sustainability of herder livelihoods such as the creation of a supply chain for producers of livestock-originated raw materialsFootnote30. Though the CAO complaint was closed in March 2019, the parties to the tripartite council agreed to continue its role to support dialogue and cooperation between the mine and local pastoralists.

7. Discussion

The three cases discussed in the previous sections demonstrate that the existing legal framework for LLAs in Mongolia limit the meaningful participation of project-affected communities. In most cases, LLAs in Mongolia are contrary to agreement-making practices in many other countries where project-affected local populations are the main parties to agreements and directly engage in negotiations. With the exception of Oyu Tolgoi, participation of local pastoralists in the negotiation and implementation of LLAs was minimal. In Oyu Tolgoi’s case, the CAO complaint and dispute resolution process resulted in a community-based formal agreement. While a number of factors, such as involvement of local government, skillful mediation, and the company’s commitment contributed to reaching an agreement, the company and the local government’s acceptance of project-affected pastoralists as a distinct group with legitimate rights and claims was crucialFootnote31. The CAO complaint process and the tripartite council are promising models for conflict resolution in Mongolia and emerging economiesFootnote32. However, a lack of recognition of the rights and claims of project-affected local populations as a distinct group in the broader local community by the state, local government, and companies may present a major challenge in the adoption of the model.

The legal framework for LLAs has been overly focused on prescribing what should and should not be in LLAs, at the expense of fostering good processes, relationships, and well governed implementation. Research shows that the company’s effective communication contributed to the formulation of positive perceptions and trust among local pastoralists in MongoliaFootnote33. When parties to an LLA have contentment thrust upon them, or are under pressure to “tick the box” of having an agreement in place, they will be more likely to view the process in purely transactional terms, rather than as an opportunity to secure their own strategic self-interest. This can have perverse consequences such as corruption, rent seeking and intimidating, or deceptive behavior by parties seeking to force an outcome. More emphasis on ensuring that LLAs comply with agreed upon procedural fairness would allow context-specific content to emerge in due course and provide more space, as well as incentives for the development of long-term collaborative relationships.

LLAs should be considered only part of a “supporting architecture” for positive, sustainable relations between mining and pastoralism. This can include mechanisms for the protection of pastoralists’ rights, consultation during the project approval processes, participatory and community-based socio-environmental impact assessment and monitoring, transparency laws, and conflict mediation institutions. In the absence of these enabling factors, the inclusivity and sustainability of dialogue between mining and pastoralism becomes primarily dependent on project-specific accountability mechanisms and the “enlightened self-interest” of mining companies. The supporting architecture of legal and institutional mechanisms are crucial for avoiding the exacerbation of preexisting vulnerabilities among Mongolian pastoralists.

8. Conclusion

LLAs are one of a few mechanisms available for affected local communities to negotiate their terms of coexistence with mining. As the Mongolian case demonstrates, legal prescription by itself will not deliver the desired outcomes of greater benefits for local communities and improved relations between these communities and developers. Oyu Tolgoi’s case demonstrates that the negotiation of long-term coexistence of mining and community requires iterative, multilayered processes involving communities affected by the project. Unless the rights and claims of project-affected pastoral communities are recognized in the LLA regulations, their meaningful participation in agreement-making will remain limited.

Geolocation information

Khanbogd, Oyu Tolgoi, Mongolia

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Byambajav Dalaibuyan

Dr.Byambajav Dalaibuyan is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies, Tohoku University and an Honorary Research Fellow of the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining (CSRM), Sustainable Minerals Institute of UQ. He is also the Director of the Mongolian Institute for Innovative Policies. Byambajav has worked on research projects exploring agreement-making in mining, community engagement and local development, and mining governance during the past 10 years.

Notes

1. Kakinuma et al., “Mongolian Pastoral System,” 12.

2. Dorjdari, “Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic,” 1.

3. Sternberg et al., “COVID-19 Resilience,” 146.

4. Lèbre et al., “Social and Environmental Complexities,” 2.

5. Cane et al., “Responsible Mining in Mongolia.”

6. Byambajav, “River Movements.”

7. Ibid.

8. Lezak et al., “Frameworks for Conflict Mediation.”

9. Lander et al., “Authority and claim-making,” 7.

10. Fraser et al., “Shared Value.”

11. O’Faircheallaigh, “Community Development Agreements.”

12. Brereton et al., “Good Practice Notes.”

13. See note 11 above.

14. Keenan et al., “Company–Community Agreements.”

15. Szoke-Burke and Werker, “Multistakeholder Institutions.”

16. Sulyandziga, “Agreements in Russian Arctic.”

17. Savada and Worden, “Mongolia: Country Study.”

18. Chuluundorj and Danzanbaljir, “Financing Mongolia’s.”

19. Byambajav, “Mobilizing against Dispossession.”

20. Upton, “Resistance and Pastoral Livelihoods,” 239.

21. See note 6 above.

22. Reeves, “Sino-Mongolian Relations.”

23. See note 9 above.

24. Hatcher, “Global Norm Domestication.”

25. Jackson, “Abstracting Water.”

26. Ibid.

27. Sternberg et al, “A South Gobi Solution.”

28. Ibid., 535.

29. Blessing and Daitch, “How Mongolian Herders.”

30. Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, “Conclusion Report,” 1 − 10.

31. Lander et al., “Authority and Claim-Making.”

32. See note 8 above.

33. Lavdmaa et al., “Trust in a Mining Company.”

Bibliography

- Blessing, J., and S. Daitch. “How Mongolian Herders Reached a Historic Agreement to Address Grievances with Oyu Tolgoi Gold and Copper Mine: An Interview with Nandia Batsaikhan.” April 10, 2018. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://goxi.org/blog/how-mongolian-herders-reached-a-historic-agreement-to-address

- Brereton, D., J. Owen, and J. Kim. “World Bank Extractive Industries Source Book: Good Practice Notes on Community Development Agreements.” Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, 2011. Accessed 15 November 2020. https://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/Portals/0/docs/CSRM-CDA-report.pdf

- Byambajav, D. “Mobilizing against Dispossession: Gold Mining and a Local Resistance Movement in Mongolia.” Journal of the Center for Northern Humanities 5, no. 1 (2012): 13–32.

- Byambajav, D. “The River Movements’ Struggle in Mongolia.” Social Movement Studies 14, no. 1 (2015): 92–97. doi:10.1080/14742837.2013.877387.

- Cane, I., A. Schleger, S. Ali, D. Kemp, N. McIntyre, P. McKenna, A. Lechner, B. Dalaibuyan, K. Lahiri-Dutt, and N. Bulovic. Responsible Mining in Mongolia: Enhancing Positive Engagement. Brisbane: Sustainable Minerals Institute, 2015.

- Chuluundorj, K., and E. Danzanbaljir. “Financing Mongolia’s Mineral Growth.” Inner Asia 16, no. 2 (2014): 275–300. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340019.

- Compliance Advisor Ombudsman. “Oyu Tolgoi 01 & 02/Southern Gobi Dispute Resolution Conclusion Report.” May. 2020. Accessed February 12, 2021. http://www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/CAOMongolia_Conclusion_Rpt_2020-05-ENG.pdf

- Dorjdari, N. “Mongolia: Updated Assessment of the Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Extractive Sector and Resource Governance.” Natural Resources Governance Institute Briefing, October 28, 2020. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://resourcegovernance.org/analysis-tools/publications/mongolia-updated-assessment-coronavirus-extractive

- Dupuy, K. E. “Community Development Requirements in Mining Laws.” Extractive Industries and Society 1, no. 2 (2014): 200–215. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.04.007.

- Fraser, J., N. Kunz, and B. Bulgan. “Can Mineral Exploration Projects Create and Share Value with Communities? A Case Study from Mongolia.” Resources Policy 63, no. 4 (2019): 101455. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.101455.

- Hatcher, P. “Global Norm Domestication and Selective Compliance: The Case of Mongolia’s Oyu Tolgoi Mine.” Environmental Policy and Governance 30, no. 5 (2020): 252–262. doi:10.1002/eet.1906.

- High, M. Fear and Fortune: Spirit Worlds and Emerging Economies in the Mongolian Gold Rush. Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2017.

- Jackson, S. “Abstracting Water to Extract Minerals in Mongolia’s South Gobi Province.” Water Alternatives 11, no. 2 (2018): 336–356.

- Kakinuma, K., A. Yanagawa, T. Sasaki, M. P. Rao, and S. Kanae. “Socio-ecological Interactions in A Changing Climate: A Review of the Mongolian Pastoral System.” Sustainability 11, no. 5883 (2019): 1–17. doi:10.3390/su11215883.

- Keenan, J., D. Kemp, and R. Ramsay. “Company–Community Agreements, Gender and Development.” Journal of Business Ethics 4, no. 135 (2016): 607–615. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2376-4.

- Lander, J., P. Hatcher, D. Bebbington, A. Bebbingtond, and G. Bankse. “Troubling the Idealised Pageantry of Extractive Conflicts: Comparative Insights on Authority and Claim-making from Papua New Guinea, Mongolia and El Salvador.” World Development 140, no. 105372 (2021): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105372.

- Langton, M., and J. Longbottom, eds. Community Futures, Legal Architecture: Foundations for Indigenous Peoples in the Global Mining Boom. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Lavdmaa, D., B. Bolorchimeg, and M. Ishikawa. “Effect of Local Community’s Environmental Perception on Trust in A Mining Company: A Case Study in Mongolia.” Sustainability 10, no. 3 (2018): 1–12.

- Lèbre, É., M. Stringer, K. Svobodova, J. R. Owen, D. Kemp, C. Côte, A. Arratia-Solar, and R. K. Valenta. “The Social and Environmental Complexities of Extracting Energy Transition Metals.” Nature Communications 11, no. 4823 (2020): 1–7. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18661-9.

- Lezak, S., A. Ahearn, F. McConnell, and T. Sternberg. “Frameworks for Conflict Mediation in International Infrastructure Development: A Comparative Overview and Critical Appraisal.” Journal of Cleaner Production 239, no. 1 (2019): 118099. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118099.

- O’Faircheallaigh, C. “Aboriginal-mining Company Contractual Agreements in Australia and Canada: Implications for Political Autonomy and Community Development.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement 30, no. 1–2 (2010): 69–86. doi:10.1080/02255189.2010.9669282.

- O’Faircheallaigh, C. “Community Development Agreements in the Mining Industry: An Emerging Global Phenomenon.” Community Development 44, no. 2 (2013): 222–238. doi:10.1080/15575330.2012.705872.

- Owen, J. R., and K. Kemp. “Social Licence and Mining: A Critical Perspective.” Resources Policy 38, no. 1 (2013): 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.06.016.

- Oyu Tolgoi Watch, Accountability Counsel, Urgewald, CEE Bankwatch Network, London Mining Network, and Bank Information Center. “A Useless Sham: A Review of the Oyu Tolgoi Copper/Gold Mine Environmental and Social Impact Assessment.” December, 2012. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/a-useless-sham-OT-ESIA-review-14Dec2012.pdf

- Reeves, J. “Sino-Mongolian Relations and Mongolia’s Non-traditional Security.” Central Asian Survey 32, no. 2 (2012): 175–188.

- Savada, A. M., and R. L. Worden. Mongolia: A Country Study. Washington, D.C: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 1991.

- Sternberg, T., A. Ahearn, and F. McConnell. “From Conflict to A Community Development Agreement: A South Gobi Solution.” Community Development Journal 55, no. 3 (2020): 533–538. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsz018.

- Sternberg, T., B. Batbuyan, B.-E. Battsengel, and E. Sainbayar. “Research Report: COVID-19 Resilience in Mongolian Pastoral Communities.” Nomadic Peoples 25, no. 1 (2021): 141–147. doi:10.3197/np.2021.250117.

- Sulyandziga, L. “Indigenous Peoples and Extractive Industry Encounters: Benefit-sharing Agreements in Russian Arctic.” Polar Science 21, no. 1 (2019): 68–74. doi:10.1016/j.polar.2018.12.002.

- Szoke-Burke, S., and E. Werker. “Benefit Sharing, Power, and the Performance of Multi-stakeholder Institutions at Ghana’s Ahafo Mine.” Resources Policy 71, no. 101969 (2021): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101969.

- Upton, C. “Mining, Resistance and Pastoral Livelihoods in Contemporary Mongolia.” In Change in Democratic Mongolia: Social Relations, Health, Mobile Pastoralism, and Mining, edited by J. Dierkes, 223–248. Leiden: Brill, 2012.