ABSTRACT

Forest-steppe fires (i.e., wildfires on grassland or forest) have serious impacts on ecosystems and economies in many countries. Many researchers, such as ecologists, meteorologists, geographers, and economists, have studied the causes and results of such wildfires from macro viewpoints. However, prior studies on the social impacts of disasters in Mongolia have mainly focused on zuds, which are harsh snow storms that occur regularly and affect the entire country. In contrast, forest-steppe fires have a limited range and are generally restricted to a certain part of the country, specifically the forest-steppe zone. This study describes the impact of fires and firefighting activities in Mongolia, focusing on the eastern borderland between Russia and China.

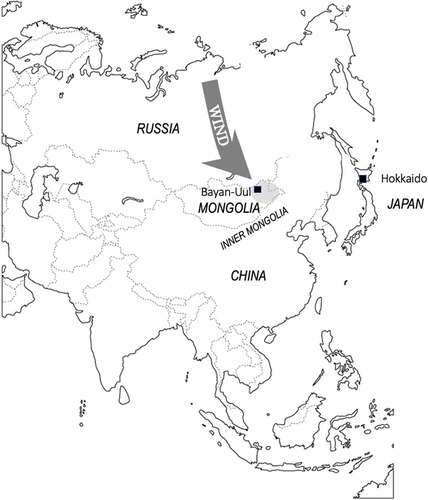

The main case study was conducted in Eastern Mongolia bordering Russia; however, as forest-steppe fires are moving disasters, fires occasionally cross social boundaries and both domestic and international borders. Additionally, as fires move with the wind, some fires that impact Mongolia originate in Russia.

We found a high contrast between damaged and non-damaged places in terms of the loss incurred as a result of the fire. Whether an area is affected depends not only on its distance from fires’ points of origin but also on fire path and speed, which are influenced by wind direction, geography, road network (which can operate as natural and human-made firebreak or fire blocker) and human efforts.

1 Introduction

Massive wildfires, such as the Amazon wildfire in 2019, the Australia wildfire in 2019–2020, and the California wildfires in 2020–2021, have a big impact on the global environment. Their greenhouse emission possibly accelerates the global warming processFootnote1. In Mongolia, although forest-steppe fires have historically been annual occurrences, their frequency, scale, and level of disturbance to ecological balance have increased since 2000Footnote2.

Forest-steppe fires occur in the Siberian taiga every year, and the prevailing winds, which blow from north to south, cause the fires to move from the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as “Russia”) to Mongolia and/or to the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as “Inner Mongolia”). Sometimes, smoke from the fires occasionally travels to Hokkaido, Japan, which may include yellow dustFootnote3.

Fires occur in Northeast Asia every spring and autumn when the temperature rises and forests and grasslands are dry due to less rainfall and snowFootnote4. Mongolians divide a year into four seasons based on the Mongolian lunar calendar, starting in spring (approximately from the middle of February to the middle of May), followed by summer (middle of May–middle of August) and autumn (middle of August–middle of November), and ending in winter (middle of November–middle of February)Footnote5. The primary source of precipitation is rain during the summer, and the secondary source is snow in winter. In contrast, spring and autumn are dry seasons; thus, spring and autumn represent fire seasons.

Forest-steppe fires occur widely across Northeast Asia, including regions of Russia, Inner Mongolia, and Mongolia. HayasakaFootnote6 performed remote sensing analysis in Sakha, Siberia, from 2002–2010, using long-term weather data from 1830 to 2010. The findings suggested that drought conditions and temperature changes cause intense fires in Russia. These fires move south unless they are extinguished, as the winds generally blow from north to south. Regarding fires in Inner Mongolia, Liu et alFootnote7. researched the relationship between climate and fire occurrence using satellite imagery for the period 2000–2014. The research area was Hulun Buir League (“league” is the Inner Mongolian equivalent to the Mongolian aimag, which means “province”), Inner Mongolia. The authors observed 5,565 fires throughout the research period and found two hotspots in the area in terms of fire frequencyFootnote8. Hulun Buir League borders Dornod Province, Mongolia; furthermore, the shape of Hulun Buir League resembles a peninsula that is surrounded by Mongolian territory.

Forest-steppe fires impact not only the ecosystem but also civil society and local people’s socio-economic lives, such as animal husbandry in Mongolia. Fires harm not only pasture but also livestock, wooden shelters, and residences, such as mobile tents called gers. Thus, according to Nyamjav et al.Footnote9, the Mongolian government has been creating forest-management policies since 1925. Since 1995, the government has enacted forest laws with support, both in regard to policy-making and budget, from international organizations such as the German Technological CooperationFootnote10.

Nasanbat and OchirkhuyagFootnote11 identified fire hotspots in Mongolia to develop a wildfire-distribution map of eastern Mongolia (comprising Dornod, Hentii, and Suhbaatar provinces). They divided the area into five levels of risk, and the highest risk zones were concentrated in the borderlands with Russia and China, respectively. They explained the causes and behaviors of the fires, dividing fire causes into “human behavior,” “natural behavior,” and “other.” It is noteworthy that the last one is described as “wildfire from neighboring country expand to the study area” in a figure, but no other information such as the fire’s country of origin was provided. Therefore, we describe fire behavior to include transboundary movement based on local knowledge.

Occasionally, with suitable conditions such as sufficient firepower and correct wind direction, smoke from Siberian fires can travel across the sea to Hokkaido, Japan, bringing pollutants such as PM2.5Footnote12. This shows that fires can be local and domestic disasters as well as moving and transnational disasters.

Prior anthropological and economic studies on disasters in Mongolia have mainly focused on zuds, which is a Mongolian term for a harsh winter characterized by low temperatures and large snowfalls; such winters can cause major damage to the country’s animal husbandry sectorFootnote13. Zuds regularly cause widespread damage across the entire country; however, fires occur every year, can concentrate in forest-steppe zones in the northern part of the country along the Russian border, and are also mobile. In this study, we focus on the following three characteristics of fires: their annual occurrence, mobility, and concentration of damage.

The aims of this study are: (1) to evaluate fires’ effect on a local pastoral society in eastern Mongolia (particularly their impact on animal husbandry, which represents the subsistence economy for the society), and (2) to describe how fires affect external areas, including neighboring countries; fires occur everywhere in Northeast Asia, but they move one-way from north to south determined by the wind direction. The case study area is eastern Mongolia, one of the countries that receives fires from Russia, and Inner Mongolia, which receives fires from Mongolia.

The present authors are an anthropologist and an economist, respectively, and we adopt a micro perspective to observe individual herders’ behaviors and decisions when their holdings are threatened by fires.

2 Materials and methods

First, our study settings were so chosen because they are located on a major fire route in Northeast Asia. Second, the research period commenced in 2015, and our field research finished in 2018; over the last two decades (from 2000 to 2021), 2015 was the year with the largest number of fires in Mongolia. Third, four methods of investigation were used in this research: photo-elicitation, anthropological observation, semi-structured interviews, and document reviews. Informed consent was obtained from our interviewees after an oral explanation of the purposes of our research. Furthermore, we observed the Japanese Society of Cultural Anthropology Code of Ethics.

We conducted fieldwork at fire-affected sites and governmental organizations, and we also reviewed statistics, newspaper reports, and academic articles. Accordingly, this study presents a combination of data, with the authors’ recorded data being used primarily and documented data secondarily.

The research for this study was mainly conducted in Mongolia. The main fire-case-study site was Bayan-Uul District (sum), Dornod Province, Mongolia (hereinafter referred to as “Bayan-Uul District”) ().

The field-research period was 2015–2018. The field research was conducted at three sites. Below, we provide a chronological description of the research process.

The first field research was conducted on May 7–10, 2015, in Bayan-Uul District. The second author conducted photo-elicitation research and anthropological participant observations in the same district. The aim was to determine the actual local impacts of forest-steppe fires and to clarify local governments’ efforts to address fires.

Bayan-Uul District is a remote area, 600 km from Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar; it is located in the Russian borderlands, at the south end of the Siberian taiga forest, and is a fire hotspotFootnote14. According to reports for Bayan-Uul District, two wildfires originating from Russian forests impacted the area in 2015; the specific dates were April 14 and 19, respectively.

The district is 562,300 ha in area and, by the end of 2014, had a population of 4,469 people and 81,649 livestockFootnote15. Most residents are nomadic pastoralists relying on pastureland, and livestock management is performed by the entire household (households in Mongolia are basically nuclear families, with 3.6 people per household on averageFootnote16). Regarding ethnicity, 80% of the population is Buryat-Mongols, a sub-ethnic group of Mongols originally from Russia. In 2014, Mongolia’s population density was 2.0 people/km2, one of the lowest populated in the world, and the Dornod Province had the 3rd lowest population density (0.6 population/km2) of 22 provinces (21 provinces and Ulaanbaatar city) in MongoliaFootnote17; this means that the local labor force available for firefighting is small.

The second author interviewed residents regarding the damage caused by the recent fires, fire-extinguishing activities, and advance preparations for fires, using photos taken with a digital camera one week after the fires had been extinguished at certain sites.

The second field research was conducted on August 8 2017, in the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. The first author and the second author both visited NEMA to conduct a semi-structured interview with a staff member, ND (alias), to understand the situation regarding fires throughout Mongolia and the measures NEMA, as a central government organization, takes to address the fires’ impact.

The third field research was conducted on August 14–16, 2018, in Zuun Uzemchin Banner, China, which is located southeast of Mongolia. The first author visited Zuun Uzemchin Banner to conduct semi-structured interviews with local herders to determine the situation on the Chinese side of the border regarding fires.

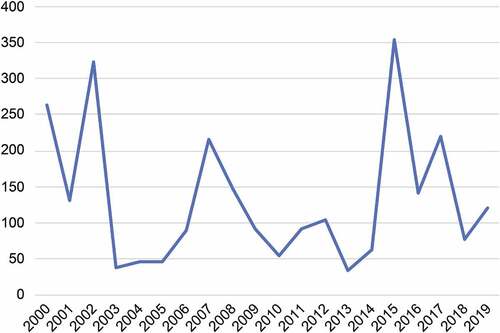

This study used National Statistical Office of Mongolia (NSOM) statistics sourced from the NEMA database titled “Annual Number of Forest Fires by Country, Region, Aimag, and Capital City,” updated on June 29 2021. According to the NSOM, during 2000–2019, a total of 2,652 forest-steppe fires occurred in Mongolia, giving an average of 132.6 fires per year. In general, 50–60 large forest fires and 80–100 large steppe fires occur annually in Mongolia.

3 Disasters in Mongolia

According to NEMA, eight types of natural disasters occur in Mongolia: earthquakes, forest-steppe fires, infectious diseases, snowstorms and sandstorms, zuds, flooding and other water-related disasters, droughts, and desertificationFootnote18. Mongolia’s natural environment and the seasonality of its subsistence economy mean natural disasters can have significant impacts. Mongolia’s natural environment is generally characterized by dryness and low temperatures. We showed in which season the natural disasters are most likely to occur in . It can be seen from this table that from spring to autumn, there is a high risk of various natural disasters, including forest-steppe fires.

Table 1. Natural disasters of each season.

Mongolian nomadic herders, who regularly move their gers, can use their mobility to avoid the dangers of various disasters. However, it is difficult to move in spring as it is the birthing season for all livestock (cattle, horses, sheep, goats, camels), and many newborn animals cannot walk at high speeds over long distances. Forest-steppe fires begin in approximately March every year, a time when herders cannot easily move their livestock. However, when the fire’s movement speed exceeds the pastoralists’ escape speed, it is necessary to take measures to control the fire.

According to ND, the NEMA staff member, most fires in Northeast Asia are human-made, being ignited by cigarettes and bonfires lit by people working in forests and grasslands or by the heat of stove ash emitted outdoors from gers. The fires then move from north to south as a result of the prevailing winds. Fires do not spread in grasslands and rocky places but move along forests. Fires from Russia can travel across the border to Mongolia or China. To prevent fires, regular meetings are held among neighboring municipal heads and heads of state, though the details are kept as diplomatic secrets.

To determine the frequency of fires in Mongolia, we can examine the NSOM’s data for the number of forest-steppe fires over the last 20 years, from 2000 to 2019 ().

Between this period, 2015 was the year with the highest number of fires, with 354 cases (this represents 13.3% of the total number of forest-steppe fires throughout 2000–2019 [2,652]). This suggests the fires of 2015 caused significant loss to the Mongolian economy, especially livestock husbandry. In 2015 and 2002, the total number of fires nationwide exceeded 300, while in 2000, 2007, and 2017, there were more than 200.

We now consider differences across areas. The NSOM divides Mongolia into five regions: “Western,” “Khangai” (meaning “forest-steppe” in Mongolian), “Central,” “Eastern,” and “Ulaanbaatar” (the capital of Mongolia), respectively. The sorting criterion is socio-natural mixed because each region is composed of provinces but is not strictly divided by vegetation zones. Additionally, different vegetation types are distributed like patches, and the natural environment changes gradually in each region and beyond the regions. However, the number of fires in Khangai is comparatively large, at 762 (representing 28.7% of the Mongolian total). Furthermore, as forest-steppe vegetation develops in patches in provinces and can extend beyond province borders, there are also forest-steppe areas outside the provinces in the Khangai region. Next, focusing on borderlands, shows that provinces bordering foreign countries, especially Russia have a high frequency of fire.

Table 2. Fire frequency and borders.

Just six Mongolian provinces (27.2%) border Russia, but these provinces account for 46.9% (112) of the fires. In brief, the above data indicate that fires often occur in northern Mongolia along the Mongolian-Russian border because the forest and forest-steppe are predominant in these areas.

The opposite folk concept to khangai is govi, which means “desert” or “desert-steppe.” Desert dominates the southern part of Mongolia, including the Mongolia-China borderlands. Five Mongolian provinces include “govi” in their name: Dornogovi, Dundgovi, Umnugovi, Govi-sumber and Govi-altai, among which four border China. Only three fires occurred in these four provinces from 2000 to 2019, representing 0.11% of the total number of fires nationally.

The degree of damage an area experiences from fires increases as fire durations, area burned, and fire frequency increase. For example, according to ND, 195 fires occurred in Mongolia from January 1 to August 3 2017(the date we conducted the interview). While 2017 had fewer fires than 2015 (), the 2017 fire sites were concentrated in the forest areas of Selenge, Bulgan, and Töv provinces, which were difficult for firefighters to access; as a result, fire extinguishing was delayed, and the combustion area expanded. NEMA consequently asked the military to dispatch a helicopter to access the sites. As firefighting against forest-steppe fire mainly involves setting firebreaks to prevent the fire from encroaching herders’ campsites and the surrounding pasture, it is necessary to get a labor force at the fire site quickly. Water buckets or hoses are generally not effective against forest-steppe fires.

Fire-extinguishing activities are supervised by NEMA, which cooperates with the military, fire departments, and local governments. When compared with zuds, forest-steppe fires occur in a limited area, but since many fires occur across the border from Russia, they are concentrated along the border and can become international situations. To fight forest-steppe fires, cooperation among NEMA, central governmental organizations, the military, and local governments is essential.

4 Fires in a pastoral area in Mongolia

4.1 Bayan-Uul District, Dornod Province; Fires in spring 2015

The research period for this study commenced in 2015, which was a critical year for fire studies because, at the national level, 2015 featured the most fires and the worst fire-related damage over the last two decades (2000–2019). Specifically for the Dornod Province, 2015 was the worst year for fires between 2010 and 2021. The research site was Bayan-Uul District, a borderland to Russia and an area that is far from Ulaanbaatar. Its location is vulnerable to Siberian forest fires, which can directly cross the border into the district; however, despite this, the area has little firefighting labor and equipment.

Bayan-Uul District is 562,300 ha in area, which is divided into the district center (approximately 1,000 ha), pasture (426,600 ha; 75.9%) and forest (135,700 ha; 24.1%)Footnote19. The district center includes a school, a hospital, the district government office, and other services. The pasture is occupied by herder families.

According to Bayan-Uul District statistics, by the end of 2014, the district had a population of 4,469 people and 81,649 livestock. Half of the population stays in the district center, while the others herd livestock in the pasture area. In 2014, there were 446 herder households, and each kept 183 animals on average. The district economy depends mainly on animal husbandry (approximately 80%), with wood logging, carpentry, and family vegetable growing representing the other common occupationsFootnote20.

The major ethnic group of Bayan-Uul is Buryat-Mongols, and their homeland or place of origin is located in Russia, just beyond the border. The herders are nomadic pastoralists who rely on pasture, and livestock management is performed by each member of the household. Mongolian nomadic herders principally move their campsite each season or more, but Bayan-Uul herders move less frequently and smaller distances when compared with Mongols in other provinces. They only move twice each year for a distance of 10 km, as they stay in summer and autumn campsites for six months and winter and spring campsites for six months. This practice may be because of the abundant pasture available to them and the influence of the sedentary lifestyle adopted in Russia around 1900 when they moved Russia to Mongolia.

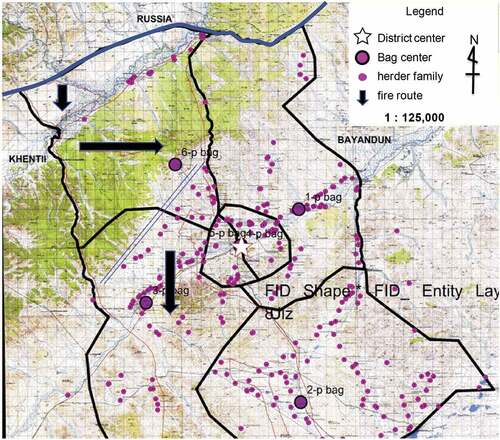

According to a government report for Bayan-Uul District, 25 forest-steppe fires occurred from 2010–2016 ().

Table 3. Fires and their characteristics in Bayan-Uul district 2010–2016.

Fire frequency varied between years, with the minimum being one fire (2014) and the maximum being seven fires (2016). It usually takes 1–3 days to control a fire, but there were three cases of fires lasting 10 days or more. Most fires originated from the north. Bayan-Uul district is divided into six bags; a bag is the smallest administrative unit in Mongolia. Regarding ignition points in Bayan-Uul District, 12 fires were concentrated in Bag-1 and Bag-6, located in the northern part of Bayan-Uul District, bordering Russia, and are areas where forests develop (). Bag-4 and Bag-5 are located at the center of the district area, which is a settlement area. The other bags, Bag-2 and Bag-3, are pastoral areas and located in the south. Regarding fires with external origins, five originated in domestic neighboring districts and provinces, and three originated in Russia. In terms of loss, in 14 fires, both forests and grasslands were lost.

Figure 3. Map of Bayan-Uul district.

The following description is in . In 2015, Bayan-Uul District was struck by four fires. Notably, the first two spring fires were unusually large among the four fires in 2015 as well as among all the fires in the period of 2010–2016. They had long durations, were of Russian origin, and burned many hectares of forest and pasture. The direct cost of fighting these two fires in 2015 represented 62.6% (these two fires cost 34,743,000 MNT, approximately 175,12 USD) of the total costs during 2010–2016 (56,381,000 MNT, approximately 28,418 USD). The first fire continued for 18 days (13–30 April) and the second for 11 days (April 20–30). According to , these two fires burned 109,393 ha of forest and 119,000 ha of forest, respectively, and a total of 204,000 ha of grassland, representing 323,000 ha in total. Overall, 55.6% of the district area, including forest, pasture, and livestock shelters, was burned ().

Critical factors affecting fire quality after ignition can be generally divided into three categories; burnable plant material, climate, and topographyFootnote21. We suggest that a wider perspective of the effects of expanding fires be adopted, with social and economic factors being added. In this study, we elaborate on fire factors to understand the situation of fires and fire-extinguishing activities as follows; 1) local natural environments, such as wind direction and topography, 2) social factors, such as road arrangements, 3) subsistence elements, such as land use and seasonality of livestock production, and 4) local knowledge of the environment.

The following describes the damage inflicted by forest-steppe fires in Mongolia, as well as the coping strategies applied, taking as an example the two major fires that occurred in Bayan-Uul District in 2015.

4.2 Case study of two large fires, April 13–30 and April 20–31, 2015

The first fire to affect Bayan-Uul District in 2015 (hereinafter referred to as Fire-1) arrived in the district on April 13, originating from Russia. Then, on April 20, while Fire-1 was still burning, another fire (hereinafter referred to as Fire-2) arrived in Bayan-Uul District from Russia. The duration of Fire-1 was 18 days (from April 13 to 30), and the duration of Fire-2 was 11 days (from April 20 to 31). Both were controlled by April 30. The total duration of the fire damage was 18 days.

Every spring, herders become aware of fires through visual and olfactory signs. Even when a fire is burning far away, with a suitable wind direction and strength, people will see a low haze in the sky and smell smoke. Some fires reach people’s campsites, but others go to other places or are extinguished.

Herders notice and observe fire signs such as a cloudy sky and a smell of smoke a few days before a fire enters the district, though fire cannot be seen in daytime, even when burning nearby. Herders cannot escape from fire because fires move at high speed; fire comes to your place suddenly and is unpredictable. Moreover, herders cannot abandon their gers and livestock shelters. In addition, bringing all the animals to a safe place quicker than the fire moves is impossible.

An overview of the fire is shown in , which presents a map of the Bayan-Uul District. Fires move through forest and grassland; forest becomes particularly flammable when temperatures rise.

Fire-1 burned the forest for the first three days (April 13 − 15) and then moved to the grassland, where the herders graze and use livestock, for the next three days (April 16–18). Specifically, the fire’s movement burning the forest and grassland was from Bag-6, through Bag-3, to Bag-1 (in ). The burned areas were most of Bag-6 and Bag-3 and the forest and grassland west of Bag-2. In particular, in Bag-3, the living areas of many herders were burned, and the damage was extensive.

Considering the overall district, the greatest fire-related losses concerned animal husbandries, such as winter pasture, shelter, hay, and livestock ().

However, the livestock loss represented just 0.6% of the district’s total animal numbers, and no human lives were lost (). The district center was saved. There was a high level of livestock concentration in the district center, and the pasture surrounding the district center was consequently overgrazed; this overgrazing (no grass to burn) prevented the wildfire’s entry into the district center.

Table 4. Fire loss in Bayan-Uul district by Fire-1.

Firefighting was executed from April 13 to April 30 (18 days). Direct expenses and financing related to firefighting are shown in .

Table 5. Firefighting-related expenses and financing.

Most expenses were related to motor fuel and food supply. The district government let people firefight with their own vehicles. Though the government gave fuel, many car and motorcycle tires were damaged by the heat. People’s clothes and boots were also damaged. The district officials were in charge of fire observation and firefighting for 24 hours. It was supported by 20 people from the Central Emergency commission led by the District governor. According to a district staff member, 769 people were conscripted to fight the fire, including firefighters from Ulaanbaatar, the center of the Dornod Province, and local individuals. Overall, 140 vehicles and motorbikes were used during the firefighting.

4.3 Wildfires’ effect on subsistence: pasture and animal husbandry

We observed six households located in Bag-3 to evaluate the effect of fires on pasture and livestock husbandry.

Interestingly, burned pasture appeared multicolored, generally showing hues of yellow, green, and dark green. Spring is the season of sprouting, and green is the color of newly growing grasses. On the contrary, yellow is the color of last year’s grass. The yellow areas were those that were not burned. New grass was also growing in this area, but they were invisible under the long and older grasses. The green areas were burned areas on which only new grasses had grown since the fire. The dark green areas were burned areas with stone and less vegetation. Horses, sheep, and goats were pasturing in the green area (burned pasture, new grass). Cows were on the yellow pasture (unburned pasture, old grass). The herders said that cows could not eat short grass, so they stayed in the old pasture. Cows collect grass by rolling it with their tongues; in contrast, other animals use their teeth to bite and pull grass from the ground. Some cows’ bodies and faces were covered with soot from the burned grass. Firefighters had experienced eye problems from similar conditions.

The biggest loss was to pasture and shelter. For example, Household-BB (the head of the household was BB, a 56-year-old male; the number of livestock in December 2015 was 273) lost their pasture and were forced to leave their winter shelter; the household began to use their summer shelter. Both Household-BM (household head was BM, a 57-year-old male; the number of livestock in December 2015 was 678) and Household-JG (household head was JG, a 33-year-old male; the number of livestock in December 2015 was 232) lost not only their pasture, but also their winter shelters, which they were using at that time, and were forced to move to unburned pasture.

Shelters are made from wood, which burns easily. Inside winter shelters, dry dung is spread as bedding to protect animals from the cold. As a result of this proliferation of dung, which is also used as a fuel in Mongolia, once started, a fire in a shelter can continue for many days. shows a case of dung continuing to burn two weeks after the fire had passed.

Although herders usually stay in winter camps and use winter shelters during the fire season, they also have summer shelters. However, summer shelters are not warm enough for newborn animals. Losing winter shelters during the livestock-birthing period creates difficulties for herders. For this reason, Household-JG left their burnt pasture and shelter and moved their ger and livestock to Household-BT’s (BT was a 49-year-old male in 2015; belonging to Bag-3; the number of livestock in December 2015 was 220) shelter, sharing the pasture and shelter. JG built a temporary shelter for sheep and goats next to BT’s shelter and used BT’s animal dung for bedding his livestock.

Regarding livestock loss, as shown in , all herders experienced relatively low losses, the exception being household-BM, which lost eight out of 70 horses; specifically, four mares, two young horses, and two yearlings died while in the pasture. These horses belonged to a new young stallion’s herd, who was absent from the herd when the fire came. Usually, horse herds escape from fire by themselves. Regarding cattle, household-BB lost 20 cows, as these cows could not be found when the fire came because BB prioritized saving the shelter but not each cow. Household-BM, whose shelter was burnt, decided to release their cows from the shelter, and thus, only two cows died after the fire’s front line passed.

When the second author visited household JG’s new campsite after the fire, JG’s wife was feeding baby goats with cows’ milk. She stated that the mother goat was skinny and had less milk this year because the pasture was lost and also that the animals were weakened because they had lost their winter shelter.

Although animal shelters were burnt, human residences such as gers and log houses were saved where possible. For example, BB’s livestock died near BB’s ger, but the ger and other property were saved. For the case of Household BTA (Head of household is BTA, no more information about them), 50 firefighters with four fire extinguishers came to their campsite, and firefighters saved their ger by spraying water on it. However, while the firefighters were resting, BTA’s shelter burned, and some of his livestock died inside the shelter.

4.4 Fire movement and laborers’ dilemma: A case study of a herder household

This section describes two days of the fire’s movement, including route and speed, burning situation, and herders’ understanding of the situations and decisions at key moments, but we do not distinct Fire-1 or Fire-2 because both fires are active during the period and we do not know which one. The section focuses on Household BT, a herder located in Bag-3 (“3-p bag,” which means 3rd bag in Mongolian in ), Bayan-Uul District, Dornod Province. BT’s winter pasture was located 30 km southwest of the district center. BT employed three laborers as herders, and he was in Ulaanbaatar on business on the first day of the fire.

We interviewed hired laborers using a photo-elicitation method. We showed records of the fire’s movement and burn path, and the herders explained their thoughts at key moments in the fire’s movement.

One of BT’s hired herders working in Bayan-Uul said, “After 4–5 days of signs of smoke in the north, the wildfire arrived in our pasture on April 18 and remained until the morning of April 19. I heard the fire came from Russia by traveling west of Ulkhan Mountain.”

At noon on April 18, the fire came from the north, crossing Ulz River near an old bridge, and then divided into two parts. One part moved in the direction of the Urt River, while the other moved toward Bayan-Uul Mountain (). The wind was not high, but the fire itself was creating a wind, which made the fire bigger. Some places were left unburned while the fire advanced to the south.

At approximately 11 am, laborers working for BT herded cows driven back from the pasture to the shelter because of the fire. These cows were at risk of running into the fire and burning themselves. The fire itself could not be seen because of smoke and dust. It took 2–3 hours for the fire to arrive from the river.

From the morning of April 18, the hired laborers began reporting to BT, who was in Ulaanbaatar, 600 km from the site, on the coming fire.

On the same day, the district’s 5–6 firefighters visited BT’s campsite to protect BT’s ger and properties as well as the whole district function. The fire was moving from west to east; the fire front was at Bag-3, where BT stayed, and the fire was about to approach the district center (). To protect the district, district firefighters tried to protect the eastern side of the district center area. Household BT supported their activity with hospitality by letting them take a rest and providing meals at their ger, as they themselves also have experience firefighting for their campsite and Bayan-Uul district.

Laborers were busy cleaning horse dung around the campsite and putting soil on the high grasses to prevent them from burning. A laborer thought of moving the livestock temporarily to already burned areas to steer them away from the approaching fire. He eventually decided against this because it was difficult for animals to stay in the burnt area as the air was too polluted. His second thought was to move the herd to the district center, running them far away from the fire. In any case, the laborers never thought that extinguishing the fire was possible.

A hired herder said, “after more than 10 hours driving from Ulaanbaatar, BT, the herd owner, arrived early on the morning of April 19th with four friends. Although most of the fire had passed through at that time, BT decided to extinguish the fire using hand tools only. At that time, two fires were coming to their campsite from the south, and a slow wind was blowing from the north, which helped a lot, and firefighting took just half a day.” They also saved a neighbor’s pasture (the household head was JD, a 60-year-old male; the number of livestock in December 2015 was 385).

This case is an example of autonomous firefighting activities.

4.5 Firefighting

At the fire site, herders whose campsites were in the path of the coming fire spread water in the forests through bucket chains and cut firebreaks in the grassland. However, it is not easy to prevent the fire from burning your campsite and extinguish the fire center in the forest at the same time. For example, while a herder named Tseden was away fighting the fire in the north, his calves burned inside the shelter at his campsite.

A problem peculiar to the pastoral area is that the fire season is the same as the birthing season for livestock, such as cows, horses, goats, sheep, and camels. Thus, herders are busy caring for birthing and newborn animals during this time, and the presence of newborn animals in the herd also means that the herd cannot travel long distances or move rapidly. Furthermore, if the herd is evacuated, the herders must find a warm shelter for their newborn animals; thus, their options are restricted.

For this reason, firefighters and volunteers from Dornod Province Center and Ulaanbaatar arrived to help fight the fires. Dornod Province contributed 2.8 times as much as the District government to the fire-extinguishing budget (). Although most local herders have difficulty participating in firefighting activities due to the needs of their herds, a total of 769 people from local settlements engaged in fire-extinguishing activities. The fire-extinguishing budget was spent mainly on fuel for vehicles and motorbikes and food for people.

To understand the response of the central government, we conducted an interview with a NEMA staff member. NEMA takes charge of fire-disaster management in Mongolia. At local governments’ request, NEMA and local governments cooperate on disaster prevention. The emergency organization system resembles a military structure. Scientific skills and knowledge are important for firefighting, as science and technology are used to predict fires’ paths, and equipment such as fire engines will be dispatched if the site is near Ulaanbaatar. Aside from formal firefighters, volunteers and soldiers can also be dispatched to fight fires.

The above described the actions taken in Bayan-Uul District to combat the two biggest fires of 2015. In (Bayan-Uul District, Citation2015) was the most serious year for fires, and the year with the greatest fire-related damage, since 2010, and many measures were taken to fight the fires.

4.6 Measures to reduce fire damage

In cases when it is impossible to extinguish a wildfire, the aim of firefighting is to limit the fire’s spread and to save herders’ camps and pastures. For herder campsites, efforts focus on preventing the fire from coming within 10-meter-diameters of livestock shelters in spring camps, which herders use during fires. For pastures, firefighters try to save pastures for the coming summer. The measures focus on controlling the speed and path of the fire and turning the fire route away from herders’ present camps and summer pastures.

For the fires of spring 2015, firefighters first tried to contain the fire in the forest and set a protection line. A protection line is a method to stop fires by producing an artificial fire called a backfire in front of the wildfire. Backfire burns fuels before the wildfire consumes them to continue spreading. In this case, the proposed protection line was drawn across Bag-6 and Bag-3 (represented by the double blue lines in ), but disagreements arose regarding where and how to set the protection line. They needed to deliberate carefully as using backfire risks the opposite of the intended effect; a backfire could be absorbed into the wildfire itself.

Second, they tried to stop the fire using a natural firebreak. At the top of Bayan-Uul Mountain, located west of the district center, people tried to extinguish the fire with human effort. The top of Bayan-Uul Mountain is rocky, bare, and has little grass, and its unique topography and gap of vegetation can work as a firebreak. As fire slowed down in such conditions, people waited for the fire to arrive there to fight it effectively. They made brooms from sticks and rubber spatulas from old tires, which they used to beat the fire.

Moreover, some pasture areas north of the district center were plowed to create a firebreak. These secondary measures partially succeeded and saved the district center.

Local residents organized special groups to fight the fires. Each firefighter group, named “van,” comprised 15 people and three fire-blowers with other equipment. Meanwhile, herder households also organized themselves into fire groups, which moved with the fires’ frontlines and worked to save gers, livestock, and shelters.

Moreover, each herder household implemented independent fire-damage-reducing measures before, during, and after the fire. Fire-damage-reducing factors can be divided into two categories: natural and human factors.

To illustrate the effect of natural factors, we describe below the experience of Household-BT during the fires and analyze how natural factors reduced the fire damage incurred to this household’s holdings. BT’s ger and livestock shelter survived the fire, along with a small fraction of pasture. As a result of this remaining pasture, Household BT could stay in their pasture area and did not require emergency evacuation. Household BT employed three laborers who lived together at BT’s campsite. According to one hired laborer, five physical and natural factors (PNFs) had notable influences on the fire’s behavior.

PNF 1. Geography: There was a rocky mountain on the north side of BT’s spring campsite, which slowed the fire’s speed. In addition, the mountain had little grass. Both inclination and the rocky surface can represent obstacles to fires’ movement.

PNF 2. Fire speed: At the time the fire passed BT’s campsite, its speed was low. If the fire’s speed had been higher, it could have easily crossed obstacles and breaks.

PNF 3. Fire center: A moving fire has a center and outskirts. Only the outskirts of the fire reached BT’s campsite, and thus, the intensity of the fire at the campsite was comparatively weak.

PNF 4. Time: The fire reached BT’s campsite at night; fire speeds are usually lower at night.

PNF 5. Road: There was a road close to the campsite, which blocked the fire. A road has no flammable material on its surface and can act as a firebreak ().

Additionally, it was assumed that wind speed was low.

Next, the following artificial factors (AFs) or human efforts to prevent fire spread were present.

AF 1. Fire-prevention zones: Fire-prevention zones are trenches that are dug around the campsite, which include gers, livestock shelters, and surrounding land for animals to spend time during nighttime. Such a fire zone saved household-BT’s ger from fire coming from the north while the herder family was fighting the fire on the south-eastern part of the campsite.

AF 2. Tractor cultivation: Local governments organize a tractor to plow a circle around each herder’s ger and shelter before the fire season to prevent spring fires from reaching the gers and shelters ().

Each household pays for the service (in autumn 2014, the fee was MNT 20,000 per family in Bag-3). One herder who did not use the service lost his ger and shelter during the fire.

AF 3. Grass cutting: In autumn 2014, a 50-meter ring of grass around the ger and livestock shelter was cut; this removed potential fuel for the fire.

AF 4. Horse dung absence: Horse dung can easily catch fire, and because it is lightweight, it can be blown with the wind, further spreading the fire. Herders removed it before the fire. Household-BT never allowed horses close to the north side of the winter shelter.

AF 5. Log barrier: Placing logs around gers, as wood is harder to be burnt than grasses, though there grow thin grasses around gers because of feet tramps (). Big thick logs are good material to prevent fire, which can be found in the Mongolian natural environment.

AF 6. Fire extinguisher: After the fire, household-BT bought a fire extinguisher of the type used by firefighters; this can represent an important AF in future fires.

In this chapter, “Fires in a Pastoral Area in Mongolia,” we described and analyzed six points relating to two large fires that occurred in Bayan-Uul District in 2015. Wildfires affected the area’s subsistence economy, causing damage to pasture, animals, and shelters. Fire peak at one place or duration of fire burning at nearby your campsite is short in time. In BT’s case, it was 18 hours; herders should aim to rapidly determine the status of coming fires and should quickly decide whether to escape or perform firefighting. For those, herders have traditional fire-reduction measures. We can call them “indigenous ecological knowledge” in general, but there were successful cases where herders could protect most properties, while others were not successful. Thus, this study showed local prevention methods linked with various fire situations in order to share better methods of responding to fires.

In the following chapters, we consider fires from a macro viewpoint or transboundary context.

5 Conclusion

The aims of this study were 1) to evaluate the effect of wildfires on a local pastoral society in eastern Mongolia, especially the impact on animal husbandry, which represents the area’s subsistence economy, and 2) to describe how such fires impact external areas, including neighboring countries.

First, we should highlight that fires always occur as a result of human activities, such as throwing cigarette butts in dry areas. Fires move with the wind; in northeastern Asia, the prevailing winds blow from the north to the south. Some fires are ignited by local people, while other fires are ignited by other people, including close neighbors, residents of neighboring districts or provinces, and also neighboring countries.

Regarding fires in a pastoral area in Mongolia, we clarified that wildfires affect subsistence, damaging pasture, animals, and shelters. Fires are disasters that can happen in a short time. In the case of BT, a herder in Bayan-Uul District, less than a day passed between the time the fire arrived and the time it was extinguished. Herders should quickly decide if they should escape from the fire with their livestock or fight the fire. We found herders use indigenous ecological knowledge to understand fire situations and to take measures to reduce fire-related losses.

Herders in Bayan-Uul know, through their lifetime experience, that the largest spring fires in 2015 came from Russia and that other fires arrive from bordering districts and provinces. They also know that if there is evidence of a fire upwind in their location, it may come to their lands sooner or later. Herders use all five senses to detect fires (e.g., smelling smoke, viewing a hazy sky, and feeling pain in one’s eyes due to smoke); this is because fires usually cannot be seen during the daytime, especially steppe fires, which smolder, making it difficult to view a flame. Furthermore, fires are annual disasters that occur every season that features warm weather and low precipitation (i.e., spring and autumn). It is impossible to remove the risk of fire, but Mongolian herders must do their best to prevent fire, escape from it and, as a last resort, fight it.

Russia, Mongolia, and China border each other and are linked by a natural environment that features forests, steppes, and winds. Thus, fires can travel from one country to the other. Any natural fire-prevention factors for fighting fire should be sought. First are the mountains. It is good to fight with fire when near a bare mountain top. The first reason is that mountains naturally prevent fires from moving. The second reason is that there are no plants on the mountain top; there is nothing to be burnt there. Second are roads; these work as firebreaks. Third, the time of day must be considered. It is good to fight with fire at night when the wind is usually weak compared with daytime. Herders should also consider fire risks when building their winter shelters.

Mongolian areas experience few deaths from fires, both in regard to locals and livestock, because of the regions’ low population density and grassland-sharing system, as well as the transfer of knowledge and skills across generations and cultural support available for people in need. Furthermore, areas can recover quickly from fire damage, as rains in summer cause the grass to grow, which restores the pastures ().

Fires travel at high speeds, causing damage over just a small number of days; meanwhile, recovery from fire loss can also be quick, taking just a few months. In contrast, the damage caused by zuds to animal husbandry can last for years.

As forest-steppe fires spread beyond social boundaries such as household pastures, districts, provinces, and national borders, cooperation among families, administrative units, and national bodies is necessary to address the associated threat. In the case of large fires, because of a shortage of firefighting labor in the countryside, firefighters from cities and volunteers gather at local fire sites. Sometimes, disagreements arise regarding how firefighting activities should proceed, but all involved should nevertheless cooperate at the firefighting site.

In summary, this study described how local people and government bodies in Mongolia prepare for and combat fires occasionally crossing the border from abroad and their relationships with neighbors and neighboring countries. In particular, we presented a case study of cooperation and conflicts among stakeholders concerning firefighting in the northeastern borderlands of Mongolia and surrounding areas.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes for the Humanities’ “Area Studies Project for Northeast Asia” at the Center for Northeast Asian Studies, Tohoku University. The authors are grateful to the administration and herders of Bayan-Uul District, Dornod Province, Mongolia, and the National Emergency Management Agency of Mongolia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mari Kazato

Mari Kazato is an anthropologist. She holds her Ph.D. in Human and Environmental Studies from Kyoto University. Her research interests focus on the subsistence economy, material culture and social changes in Mongolia, and post-socialist societies in Eurasia. Email: [email protected] Reserchmap: https://researchmap.jp/read0110336

Battur Soyollham

Battur Soyollkham is a Mongolian agricultural economist. He is from the eastern part of Mongolia. He holds his Ph.D. from Hokkaido University. His research includes nomadic economy and risk management. He mainly works to connect Mongolia with international businesses and researchers. Email: [email protected] Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/battur.soyollkham.9

Notes

1. For example, CitationJapan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), “Visualization of California wildfires by earth observatory satellites, Seen from Space 2020.”

2. Nasanbat and Ochirkhuyag, “Wild Fire Risk Map in the Eastern Steppe of Mongolia Using Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis.”

3. Ikeda and Tanimoto, “Exceedances of Air Quality Standard Level of PM2.5 in Japan Caused by Siberian wildfires.”

4. For example, Nasanbat and Ochirkhuyag, “Wild Fire Risk Map in the Eastern Steppe of Mongolia Using Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis,”469–470; Li et al., “Influence of Land Use on Grassland Fire Occurrence in Northeastern Inner Mongolia,” 4.

5. Tsedenbal, “XVII Jarny Sharagchin Tuulai Jiliin Mongol Zurhain Tsag Toony Bichig, Toorgiin Chuluuny Zurlaga.”

6. Haysaka, “Vegetation Fire Incidence in Russia.”

7. Liu et al. “Climate and Grassland Fire in HulunBuir.”

8. Ibid., 5–7.

9. Nyamjav et al., “Forest Fire Situation in Mongolia.”

10. Nyamjav et al., “Forest Fire Situation in Mongolia,” 6.

11. See above 2.

12. CitationJapan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), “Air Pollutants Across Borders”; Ikeda and Tanimoto, “Exceedances of Air Quality in Japan”; Takemura, “Smoke from Siberian Fire comes to Hokkaido.”

13. Battur et al., “Changes of Mongolian Nomads in Recovery from ‘Dzud 2000’”; Ozaki and Takakura, “Policy Related Environmental Disaster and Socio-Cultural Impacts in Mongolia.”

14. Nasanbat and Ochirkhuyag, “Wild Fire Risk Map in the Eastern Steppe of Mongolia Using Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis,” 470; Liu et al., “Climate and Grassland Fire,” 5–7.

15. Bayan-Uul District, “Statistics of Bayan-Uul District.”

16. The authors calculated the average household size based on the data; NSOM, “Mongolian Statistical Yearbook 2012,” 7.

17. NSOM, “Mongolian Statistical Yearbook 2014,” 13.

18. Enkhtsolmon, “How to prevent disaster and fire.”

19. Dornod Aimgiin Ulsyn Burtgeliin Heltes, “Online Reference System.”

20. See above 15.

21. Goldammer et al., “Defense of Villages, Farms and Other Rural Assets against Wildfires,” 15–16.

Bibliography

- Bayan-Uul District. “Statistics of Bayan-Uul District. (We Visited the Bayan-Uul District Government Office to Read These Statistics as Their Internal Document).” (2015).

- Battur, S., E. Shiga, and S. Yoshinaka. ““Saigai kaihukuki ni okeru Mongol koku yuboku keiei no henka: Chikushu kosei nohenka to sono yoin ni chakumoku site” [The Changes Implemented by Mongolian Nomads in the Process of Recovering from the Winter Disaster ‘Dzud 2000’].” The Frontiers of Agricultural Economics 15, no. 1 (2010): 74–83.

- Dornod Aimgiin Ulsyn Burtgeliin Heltes. “Onlain Lavlagaany System” [“Online Reference System”]. Accessed October 3, 2016. http://ubh.dd.gov.mn/?page_id=691.

- Enkhtsolmon, G. “Gamshgaas hamgaalah, gal tuimriin ayuulaas uridchilan sergiileh arga hemjee [“How to Prevent Disaster and Fire”]. NEMA [Niisleliin Ontsgoi Baidlyn Gazar]”. We visited the NEMA office to be given this electric file as an internal document 2016

- Goldammer, J. G., I. Mitsopoulos, B. Oyunsanaa, and P. Sheldon. “Huduu oron nutgiin irged, nutgiin udirdlaguudad zuriulsan Oi, heeriin tuimrees uridchilan sergiileh hamgaalah garyn avlaga [“Forest and Steppe Fire Prevention and Protection Guide for Rural Residents and Local Authorities”]”. Global Fire Monitoring Center. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://gfmc.online/wp-content/uploads/Village-Defense-Guidelines-MON.pdf.

- Hayasaka, H. “Recent Vegetation Fire Incidence in Russia.” Global Environmental Research 15, no. 1 (2011): 5–13.

- Ikeda, K., and H. Tanimoto. “Exceedances of Air Quality Standard Level of Pm 2.5 in Japan Caused by Siberian Wildfires.” Environmental Research Letters 10, no. 10 (2015): 1–9. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/10/105001.

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). “Visualization of California Wildfires by Earth Observatory Satellites, Seen from Space 2020.” In Earth Observation Research Center (EORC). Space Technology Directorare I, 2020. [Accessed on August 25, 2022]. https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/en/earthview/2020/tp200928.html

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). “Air Pollutants across Borders Observed from Space, Seen from Space 2014.” In Earth Observation Research Center (EORC). Space Technology Directorare I, 2014. [Accessed on August 25, 2022]. https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/en/earthview/2014/tp140319.html

- Khatanzorig, A. 2017. “Mongolia and Russia Discuss Forest Fire Prevention Issues.” Montsame, October 17. https://www.montsame.mn/jp/read/131933.

- Li, Y., J. Zhao, X. Guo, Z. Zhang, G. Tan, and J. Yang. “The Influence of Land Use on the Grassland Fire Occurrence in the Northeastern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China.” Sensors 437 (2017): 1–19.

- Liu, M., J. Zhao, X. Guo, Z. Zhang, G. Tan, and J. Yang. “Study on Climate and Grassland Fire in HulunBuir, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China.” Sensors 616 (2017): 17(3).

- Nasanbat, E., and L. Ochirkhuyag. “Wild Fire Risk Map in the Eastern Steppe of Mongolia Using Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis.” The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLI-B1, 2016 XXIII ISPRS Congress, 12–19 July 2016, Prague, Czech Republic (2016): 469–473.

- National Statistics Office of Mongolia. “Annual Number of Forest Fires by Country, Region, Aimag, and Capital City.” 2020. https://www.1212.mn//tables.aspx?tbl_id=DT_NSO_2400_005V1&SOUM_select_all=1&SOUMSingleSelect=&YearY_select_all=1&YearYSingleSelect=&viewtype=table

- National Statistics Office of Mongolia. Mongolian Statistical Yearbook 2014. National Statistics Office of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar, 2015.

- National Statistics Office of Mongolia. “Mongolian Statistical Information Service.” 2022. [Accessed Jul 10, 2022]. https://www.1212.mn

- Nyamjav, B., J. G. Goldammer, and H. Uibrig. “The Forest Fire Situation in Mongolia.” International Forest Fire News 36 (2007): 46–66.

- Ozaki, T., and H. Takakura. “Policy Related Environmental Disaster and the Socio-Cultural Impacts in Mongolia.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies (2021): 1–21.

- Takemura, T. 2018. “Shiberia shinrin kasai no kemuri ga Hokkaido he hirai” [Smoke of Siberian forest fire comes to Hokkaido]. Yahoo! News Japan. April 27. https://news.yahoo.co.jp/byline/takemuratoshihiko/20180427-00084525/

- Tsedenbal, Y. XVII Jarny Sharagchin Tuulai Jiliin Mongol Zurhain Tsag Toony Bichig, Toorgiin Chuluuny Zurlaga. “Mongolian traditional Astrology Calendar of the rabbit year, 1999-2000.” Ulaanbaatar: Ongi Hevleliin Gazar, 1998.