ABSTRACT

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has evolved to a leading subject for both academic research and management practice. Although several standpoints exist to approach theoretical and practical implementation issues, however, CSR is, mostly, perceived as a managerial tactic that integrates and deals with sustainability challenge. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has already attempted to align its policy with United Nation’s (UN’s) latest sustainability mandates and, specifically, with UN's 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development. In that respect, the Organization has committed itself to establish a sustainable maritime transportation system by founding sustainability initiatives in a wider CSR framework. Further to a study carried out to 50 tanker and dry bulk maritime companies, the aim of this study is to investigate and discuss restricting factors and driving forces associated with the implementation of CSR in shipping. Chi-square independence test and contingency coefficient statistical measures are employed to test formulated hypotheses. Findings imply that lack of training and appreciation of long-term benefits that CSR can bring to an organization constitutes a significant discouraging factor to CSR engagement. In terms of CSR drivers, increased trust and improved company's image and relationships with key stakeholders represent a key motivating factor to CSR implementation.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a broad subject that has, progressively, been extended and established itself into the current business mindset. Regulatory developments and greater environmental sensitivity have transformed contemporary business operational mentality. Therefore, it has been recognized that private entities, along with their profit making character, have a critical role to play in preserving earth’s natural resources and communities’ well-being (McElhaney Citation2009). On the contrary, from a more cynical view, it has been admitted that the primal objective for business is to utilize its available resources and operate in a way that profit maximization is achieved. However, a more ethical approach supports that every enterprise should view itself as a public entity and performs in a way that financial pursuits are achieved, as long as they are balanced with its social contribution. Further searching of the literature, it has been ascertained that CSR refers to a multilateral issue, which incorporates a combination of moral, academic and financial orientations (Aras and Crowther Citation2008). However, regardless the angle that somebody approaches CSR, globalization, evolving business operating models, technological advances, developments in international law and greater connectivity among stakeholders across the world have placed multidimensional challenges for today’s businesses (Kytle and Ruggie Citation2005).

As a result, increasing interdependencies and interconnections among various entities have generated additional risks for organizations. Especially, for international industries, like shipping, the world seems too small to hide (Kytle and Ruggie Citation2005). Shipping is perhaps the most internationally minded and heavily regulated industry in the world. Thus, irrespective the worldwide growing CSR and sustainability tendencies, the maritime world have always been accustomed to such themes. Dealing with subjects such as, health, safety and environmental protection, supplier management, seamen labour rights, energy efficiency and emissions reduction refer to challenges that have, continuously, held a prominent place into the daily task agenda of ship managers (IMO Citation2013). Moreover, the management of ships refers to a complex and multifaceted task where maritime activities take place in an international environment, among entities and individuals that come from a variety of backgrounds, with diverse and sometimes conflicting chases. In addition to that feature, an additional element of shipping, which diversifies its nature from other industries, relates to the great exposure and interaction with international, regional and local cultures, regulatory regimes and stakeholders interests (Coady et al. Citation2013).

Adopting a CSR policy, measurement and reporting programme is not a straightforward process and there are several drivers and barriers influencing its implementation (Agudo-Valiente, Garcés-Ayerbe, and Salvador-Figueras Citation2017). The lack of a strategic management commitment to implement CSR, lack of resources, inadequate knowledge and regulatory inadequacy are some of the factors that deter CSR implementation (Gligor-Cimpoieru and Munteanu Citation2015). On the other hand, improved relationships with stakeholders, enhanced employee relations, improved company’s image, reduced operating costs and improved efficiency are acknowledged as reasons that stimulate CSR engagement (Timane Citation2012). With regard to the shipping industry, and unlike to land-based industries, where CSR practices are at a more developed state, there is not much available research on the perceived barriers and drivers from CSR engagement (Fafaliou, Lekakou, and Theotokas Citation2006).

Further to the above discussion, this paper investigates perceived barriers and drivers to be accrued by CSR implementation, as experienced by maritime companies operating in the dry bulk and tanker shipping sector.

Literature review

CSR is a multilateral issue and, as stressed previously, there is not a commonly agreed definition on that theme. However, and consistent with the current integrated approach to sustainability, CSR is mostly approached as “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” (Aras and Crowther 2008, 11). Investigating the roots of CSR we conclude that it does refer to a newly launched idea and, as such, its origins are traced back in the “social contract” theory (Davis Citation1973). As implied by this approach, businesses should think and act in an ethical and legitimate manner and, within that context, a socially responsible behaviour requires involvement and contribution of corporations to society (Moir Citation2001). Closely related to “social contract” theory lays also the “Iron law of Responsibility” approach. Such principle assumes that private enterprises poses power, which should be analogous to their obligations to society. As such, companies that maintain such power are expected to contribute and advance society’s welfare (Okoye Citation2009). In another perspective, it has been argued that CSR has its roots in the stakeholder theory (Asif et al. Citation2011). In that sense, managing and maintaining good relationships with stakeholders is expected to add value to the company by the increased trust and reduced risks born by business interaction with such affected parties (Brown and Forster Citation2013). In a more modern perspective, CSR is seen as a business model approach to deal with sustainability developments and associated regulatory mandates in an integrated manner (Alhaddi Citation2015).

Continuing our journey into CSR setting, it has been observed growing environmental concerns and the need to consider business impacts in an integrated manner (namely, from a social, economic and environmental angle) have transformed CSR thinking to a managerial tool that embraces and deals with sustainability challenges (Bhagwat Citation2011, March). Further to that, approximating and understanding contemporary sustainability developments facilitates the appreciation of subsequent CSR evolution. As literature review reveals, CSR inclinations have been growing simultaneously to unceasing global sustainability trends and, thus, have become an increasingly expanded concept in business setting (IMO Citation2013). CSR has been, quite often, brought to the forefront of the international community as an essential success component of every sustainability initiative. Within the business context, the European Commission has stressed the usefulness of CSR as a management tool that enables business to operate sustainably and beyond compliance with minimum regulatory requirements (European Commission Citation2001). In line with European Commission, United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), on February 2013, expressed the opinion that CSR can be thought as the vehicle of private firms to achieve their economic, social and environmental pursuits (UNIDO Brussels – United Nations Industrial Development Organization Citation2018). Furthermore, CSR constitutes an established tactic and integral component of business management and improvement cycle. In that sense, it has been, frequently, argued in the business arena that: you cannot manage what you cannot measure. (Hoekstra et al. Citation2014). In addition, disclosure on social, environmental and economic facts is greatly seen by firms, stakeholders and governmental or non-governmental organization as a mechanism of transparency and practice to identify and communicate positive and negative business impacts (O’Rourke Citation2004). However, while reporting a firm’s overall performance does not refer to a recent practice, though, employing a standardised CSR reporting method represents a tactic that first appeared at the end of the 1990’s (Juščius, Šneiderienė, and Griauslytė Citation2014). Nevertheless, CSR measurement and reporting refer to a growing business trend and governmental or non-governmental policy (O’Rourke Citation2004).

Despite the recognized positive impact of CSR within an organization’s function, there are several factors discouraging company’s decision to establish of a CSR policy, measurement and reporting programme. Firstly, the non-inclusion of CSR principles into company’s strategic objectives has been argued to form a vital barrier to CSR implementation. Ineffective dissemination of CSR within an organization is, generally, attributed to the reason that neither has been set as strategic priority for the company nor has been incorporated to its strategic objectives (Emezi Citation2014). Moreover, management principles recognize corporate culture and senior management commitment as a fundamental element of success for every major strategic and policy initiative within an organization. A corporation that shorts a senior cultural identity and ideology to recognize CSR values and long-term benefits it can bring to organization constitutes a deterrent factor that discourages its adoption (Hakala Citation2015). Exploring further CSR barriers, it has been claimed that increased organizational costs and lack of financial support has been considered as another obstacle to CSR implementation. CSR venture is, frequently, seen by organizations as a costly activity with undetermined short-term and long-term benefits. As an extension to that is further added the lack of adequate resources (i.e., personnel) to facilitate effective CSR implementation (Shen, Govindan, and Shankar Citation2015). Another significant barrier to CSR undertaking is the lack of adequate knowledge and education of managers on that theme. Insufficient theoretical and practical CSR knowledge is seen as a common disadvantage of higher staff, which prevents the adoption of CSR policy (Laudal Citation2011). The non-existence of a mandatory regulatory regime refers to another factor that prevents CSR adoption. Although there is a lot of interest and partnering on CSR among various instruments and institutions, they all maintain a voluntary and recommendatory profile, which does not force companies to implement CSR (Steurer Citation2010).

On the other hand, there is a growing motivation on behalf of organizations to engage with CSR and, as such, there are significant benefits justifying the implementation of a CSR policy and reporting programme. A CSR programme is believed to improve company’s ethics, economic transparency and efficiency. In that sense, spreading CSR values across employees and organization functions is expected to increase loyalty, stimulate innovation and reduce risks (Gligor-Cimpoieru and Munteanu Citation2015). Other studies view CSR as a strategic tool that facilitates stakeholder management. In a continuous changing and multilateral business environment, CSR can assure company’s viability, through increased trust and improved company’s image and relationships with key stakeholders (Mbogoh and Ogutu Citation2017). In another perspective, CSR is expected to sustain business legitimacy. A perceived benefit in this area is considered to be the enhancement of company’s ability to deal with regulatory requirements and avoid legitimate sanctions (Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler Citation2008). Improved health, safety and environmental performance, refers to another driving force, which, indirectly, is linked to CSR implementation. In that respect, a strategic CSR approach, focused on occupational health, safety and environmental aspects, is expected to raise employer’s image, increase public appreciation, diffuse openness and no blame philosophy and influence a more positive employee behaviour and attitude toward health, safety and environmental matters (Sowden and Sinha Citation2005). Furthermore, company’s employees seemed to respond positively to CSR activities and increase their confidence to their employer. Thus, benefits in this area derive by the improved relationship and increased trust between company and its employees, which, subsequently affects, positively, individual and organizational performance (West, Hillenbrand, and Money Citation2015).

In the maritime context, CSR has been steadily making its presence. The introduction of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, and 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), refers to a significant regulatory development, which has, furthermore, triggered a drastic diffusion of CSR in shipping. In line with this view is International Maritime Organization’s (IMO’s) statement, made during IMO World Maritime Day symposium, on 26 September 2013, through which, the Organization emphasized its vision and commitment to establish a CSR mindset in shipping. Moreover, CSR has been recognized by IMO as a vital component for the achievement of a sustainable shipping industry (IMO Citation2013). However, comparing to other industries, research on CSR implementation in shipping is somehow fragmented and recent (Fafaliou, Lekakou, and Theotokas Citation2006). In a study carried out at the Baltic Sea maritime companies, CSR has been, mainly, viewed as a mean to improve company’s environmental performance and quality of provided service (Kunnaala, Lappalainen, and Storgärd Citation2013). In the same context, Progoulaki and Roe (Citation2011) suggest that CSR is viewed by shipping companies as a mean to distinguish their service to customers and assure environmental compliance and efficiency. Moreover, Coady et al. (Citation2013) support that CSR in shipping is mostly understood as a regulatory compliance issue to deal with statutory maritime legislation, rather than a managerial approach to embrace wider social, environmental and economic challenges. To sum up, Lund-Thomsen, Poulsen, and Ackrill (Citation2016) suggest that, with the exception of the container and cruise sectors, which appear to be at more advanced state, there is not much research undertaken to investigate shipping companies’ perceptions over the drivers and barriers influencing their decision to adopt a CSR policy and reporting programme.

In the light of identified gaps and current growing expansion of CSR in shipping, the aim of this paper is to investigate barriers and drivers experienced by CSR implementation into the tanker and dry bulk shipping sector.

Hypotheses development

Barriers to CSR implementation

Organizational culture has become a highly ambiguous term and major area of concern for corporations and researchers and, as such, several viewpoints have been used to set its intellectual foundations (Ouchi and Wilkins Citation1985). However, establishing a common meaning and consensus is not a straightforward task as there are a wide range of contradicting definitions and approaches to describe organizational culture, which, moreover, serve different purposes and motives (Daugherty Citation2007). In a broad and widely adopted standpoint, organizational culture is defined as the norms, climate and practices that organizations’ embrace to achieve their business objectives (O’Donnell and Boyle Citation2003). It is also viewed as a tool that organizations can use to shape behaviours and adapt to the external environment and challenges. Strategic management is seen as the vehicle that transmits the elements of corporate culture to employees and characterizes the whole organizational behaviour in the respective market sector (Tasgit, Şentürk, and Ergün Citation2017). Decision to adopt a CSR policy is strongly affected by organizational culture. In particular, a corporate culture and attitude that does not encompass CSR elements will, inevitably, constitute a significant barrier to CSR implementation and diffusion within organization’s operating practices (Valkovičová Citation2018). Organizational culture is reflected and constitutes the pillar of every major initiative and pursuit within an organization. Therefore, the lack of a corporate culture, founded on CSR values, represents a foremost discouraging factor for the non-adoption of a CSR initiative within the company (Lee and Kim Citation2017).

Senior management commitment is closely related to organizational culture and represents a critical factor for the success of a CSR undertaking. Management executives have a crucial role to play in formulating organization’s principles and their values and beliefs will be significantly reflected into organization’s processes and social concerns (Swanson Citation2008). Top managers lead people and, therefore, their personal involvement is essential in order to convince and motivate their subordinates. A lack of senior management appreciation and commitment to CSR values will definitely discourage mid and low level employees (Valkovičová Citation2018). Senior management leadership and commitment is a determinant for the success of every major business initiative. The lack awareness of the benefits that CSR principles could bring to the organization and a sole profit maximizing objective is considered to be the most important factor that discourages shipping companies to adopt a CSR strategy, measurement and reporting programme (Shen, Govindan, and Shankar Citation2015). Top management commitment and sincere belief to CSR values are elements that differentiate symbolic and genuine CSR initiatives, which, furthermore, determine the subsequent successful CSR implementation (Gligor-Cimpoieru and Munteanu Citation2015). With regard to the shipping industry, the lack of CSR recognition and support from top management has been, highly, indicated as a barrier to CSR implementation by shipping companies. In particular, the absence of a corporate culture and commitment by senior managers to appreciate accrued benefits and, thus, adopt CSR is significantly seen as a major restraining factor to CSR implementation by shipping companies (Yuen and Lim Citation2016). It is, thus, hypothesised that:

H1: Adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme is more likely to be discouraged by the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment on CSR.

Drivers to CSR implementation

Business decisions and operations bear impacts and affect people’s lives, either individually or as part of a group. Companies are not isolated entities functioning outside the real world and societal system. On the contrary, they form part of community and, thus, are frequently held accountable for their social and environmental impacts. The theory of stakeholder management constitutes an integral part of CSR philosophy and it is imperative for a socially responsible firm to listen the issues raised by the society (Network for Business Sustainability Citation2012). As previously noted, business actions involve risks. One of these risks, namely, the social risk, arises when business activities generate an impact and inconvenience for a stakeholder who, consequently, applies pressure on the company to change its policies or practices. In that sense, adoption of a CSR strategy and reporting programme has proved to be a useful tool in the hands of organizations in their attempt to improve relationships with stakeholders and enhance company’s ability to manage corporate risks (Kytle and Ruggie Citation2005). According to O’Rourke (Citation2004) study, managing external impacts and establishing partnerships and relationships is of paramount importance for enterprises’ continuity. In that sense, adoption and implementation of a CSR programme needs to be carefully designed, evaluated and feedback communicated to key stakeholders. Further to that approximation, stakeholder theorists support that companies, in their effort to add value to the bottom line of the company, place great emphasis on managing stakeholder relationships through CSR activities (Brown and Forster Citation2013). Therefore, stakeholder management is considered central component of CSR and thus, depending on stakeholders’ interests and concerns, firms should maintain an open dialogue and create strong partnerships with affected stakeholder groups (Kakabadse, Rozuel, and Lee-Davies Citation2005).

As far as the maritime industry is concerned, it has been recognized that effective ocean governance requires the engagement of various stakeholders with a genuine interest in shipping. Therefore, policy-making initiatives in shipping necessitate involvement of more opinions, through extended stakeholder engagement (Roe Citation2013). Maritime stakeholders have been showing a growing interest toward CSR issues and, in particular, for the ethical and social performance of shipping companies. For example, pilotage companies in Finland comply with CSR governmental requirements and have adopted CSR reporting practices (Kunnaala, Lappalainen, and Storgärd Citation2013). Fafaliou, Lekakou, and Theotokas (Citation2006) support that maritime stakeholders, such as, shippers, show a growing interest in CSR policies and initiatives adopted by shipping companies. In view of sustainability pressures, maritime stakeholders demand for greater transparency and accountability on behalf of shipping companies, in terms of their social and environmental performance. Commercial viability of the company is significantly influenced by the way stakeholders perceive its social profile (Poulovassilis and Meidanis Citation2013). Further to the stakeholder issue, a study carried out for the CSR application in the Baltic Sea Maritime sector showed that CSR and sustainability issues, have been, increasingly, attracting the attention of various stakeholders. Increasing customer trust, loyalty and the probabilities to attract new charterers and expand their business are considered to be the main gains to be acquired by company’s engagement with CSR activities. In addition, in this study, shipping companies expressed the belief that company’s trust and reputation in the market improves significantly when engaging with CSR activities (Kunnaala, Lappalainen, and Storgärd Citation2013). As such, the following hypothesis has been developed:

H2: Adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme is more likely to be motivated by the increased trust and improved image and relationships it will bring with stakeholders.

Methodology

Research design

The aim of our study is to describe a social phenomenon and connect what is known with what can be learnt through our research findings. A quantitative research approach and strategy has been adopted and, as such, our study begins deductively with review of existing literature and available theories. Literature review resulted into the formulation of two hypotheses with regard to perceived restraining factors and driving forces of CSR implementation in shipping. A questionnaire survey was conducted in order to gather data and provide an understanding of the relationships between variables testing, thus, our formulated hypotheses. Descriptive and inferential statistics, subsequently, are used to interpret raw data and determine the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variables (Soiferman Citation2010).

Targeted sample group and data collection method

Our survey sample comprises 50 shipping companies, based on 14 countries worldwide and having assumed the technical management of tankers and/or bulk carrier ships. Management of other ship types (i.e., passenger or cruise ships) was also acceptable; however, it was a requirement that company’s fleet should include at least tankers and/or bulk carrier ships. The survey incorporates demographical data (i.e., respondents’ working department, numbers of employees and managed ships, types of vessels under management, etc.). Other, sections incorporate questions related to CSR awareness, adoption of a CSR policy, perceived barriers and drivers to be encountered in the adoption of a CSR policy, measurement and reporting programme, etc. The respondents were asked to rate their preference on a five point-Likert (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and a Yes/I am not sure/No, scale. An electronic self-administered questionnaire was sent to employees working in various departments, such as, technical, safety & quality, operations, accounting/management and supply.

summarizes our research hypotheses and corresponding variables incorporated in our survey and data analysis.

Table 1. Independent and dependent variables and corresponding hypotheses.

Data analysis

The type of variables and nature of collected data form the basis for the selection of the most appropriate data analysis method. Due to the reason that our data are categorical, measured on a nominal scale, chi-square test of independence was employed to test the existence of a statistically significant relationship between variables. Chi-square test of independence is a significance statistic measure that enables us to test hypotheses about variables measured at a nominal level. Specifically, when the p-value is < 0.05 (where 0.05 = a, refers to the level of significance), the null hypothesis is rejected and alternative hypothesis is retained (McHugh Citation2013). Furthermore, the strength of identified relationships between variables is tested using contingency coefficient (C) measure. C values range between −1 and 1. Values close to −1 imply a strong negative relationship, while values close to 1 indicate a strong positive association. Values close to 0 imply no association between variables (www.empirical-methods.hslu.ch, Citation2018). The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 for windows was used for conducting our statistical analysis.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Demographics

Out of the total 50 respondents, the majority of them are males (76%), while with the remaining 24% being females. 66% of the respondents aged over 40 years old, with the majority of them (64%) being employed in the QHSE department. With regard to the companies’ size, 52% of companies manage a fleet that ranges between 1 and 40 ships. It is also worth mentioning that a high rate of companies (34%) manages a fleet that surpasses 60 vessels. Moreover, 58% of companies’ employees (both at the office and ashore personnel) exceed 251 persons. Concerning companies’ management “style”, the highest participants’ rate (48%) refers to ship owning companies performing exclusive technical management services to a sole ship owner, while 22% represent third-party ship management companies performing technical management services to various ship owners. With regard to the types of managed ships, the majority of them (74%) manage tankers, gas carrier and dry bulk ships, while 4% manage passenger/cruise ships, additionally to their dry and tanker managed fleet. From the demographical data can be concluded that our sample deals with a wide range of companies’ size and there is an ample diversity, in terms of management “style” and types of managed ships. Furthermore, the fact that respondents are mostly occupied in the QHSE department implies a good level of understanding and familiarity to CSR issues. Moreover, the majority of companies are based in Norway (22%) and Greece (20%), while 10% are based in Italy, Turkey, Monaco, Sweden and Belgium. Such wide-ranging companies’ base country (14 countries worldwide in total) differentiates research results and, thus, does not constrain our survey latitude and judgments to the framework of a single country or district.

Barriers and drivers to CSR implementation

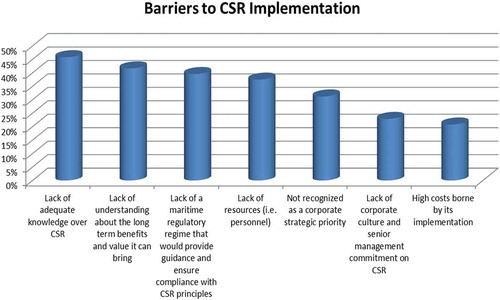

The majority of participants (94%) answered that they are personally aware of CSR theme, while a small rate (6%) replied that they were not aware. Furthermore, 82% of companies have adopted CSR policy/principles into their ship management practices. Such results imply that CSR has been, steadily, increasing, its presence into the shipping industry. A contrasting feature is that although the majority of the companies have adopted CSR (82%); however, only 16% of them generate a stand-alone CSR report as a mean to communicate their overall performance. According to results, the majority of them (72%) prefer to produce an integrated health, safety & environmental report. In addition to that, only 2% of companies have been officially certified against a CSR Standard, while the majority of them (62%) found to be officially certified against ISO14001 environmental Standard. Top management/Board of directors is the most ranked recipient of such report (95%), while a small rate of companies chooses to communicate such report to the industry/press (18%). It is worth noting here that company’s employees (71%) and charterers (63%) are highly indicated as receivers of companies’ overall performance report. With regard to perceived barriers to the adoption of a CSR policy, measurement and reporting programme, the lack of adequate knowledge on CSR issues appears to be the greater barrier (46%). The lack of appreciation for the long-term benefits that CSR can bring to the organization refers to the second barrier to CSR implementation (42%). In addition, the lack of a maritime regulatory regime to provide guidance on CSR implementation (40%) and the shortage of resources (38%) represent the third and fourth discouraging factors to CSR implementation. It is worth mentioning at this point that the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment (23%) does not look to be highly perceived as a barrier to CSR adoption. A synopsis of perceived barriers is presented in .

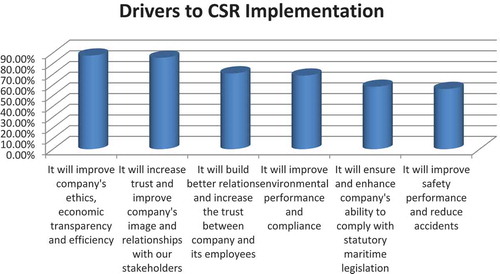

Improved ethical, economic transparency and efficiency is considered to be the greater factor to encourage adoption of a CSR policy, measurement and reporting programme (87%). Increased trust and improved company’s image and relationships with stakeholders, is ranked second in terms of its motivation to CSR implementation (85%). Moreover, establishment of better relationships and trust between company and its employees (70%) and improved environmental performance and compliance (68%) refer to the third and fourth CSR driving factor. Enhanced company’s ability to comply with maritime legislation (58%) and improved safety performance (56%) are the less rated motivating factors to CSR implementation. depicts perceived drivers to CSR implementation by companies.

Hypotheses testing results

Testing results of hypothesis 1 – H1

Further to the application of chi-square test of independence, obtained p-value is 0.250 > a. Such a result implies the lack of a statistically significant relationship between variables, with a = 0.05, being the level of significance. As such, adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme is not likely to be discouraged by the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment on CSR. Therefore, the null hypothesis is retained (X2 (4) = 5,388, p = 0.250). Furthermore, as per contingency coefficient measure, the estimated C value is 0,318. Such result suggests a weak association between selected variables (CSR adoption by company and the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment on CSR). Additionally, due to the reason that such association between variables is not statistically significant (since p > 0.05) it is, further, assumed that no consistency exists between the lack of corporate culture and senior management commitment (independent variable) and the adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme by companies (dependent variable).

Testing results of hypothesis 2 – H2

Applying chi-square test of independence measure of association, the p-value is 0.005 < a. Such a finding demonstrates that, at the level of significance a = 0.05, there is a statistically significant relationship between variables. Further to that, adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme is more likely to be motivated by the increased trust and improved image and relationships it will bring with stakeholders. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected (X2 (4) = 15,033, p = 0.005). From the application of contingency coefficient measure, the estimated C value is 0,488. Such result signifies a positive relationship between increased trust and improved image and relationships CSR can bring with stakeholders (independent variable) and the adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme by companies (dependent variable). As such, it is expected that further reinforcing stakeholders expectations and positive attitude on CSR will, equitably, stimulate adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme by shipping companies.

summarizes the results from the application of chi-square test of independence and Contingency Coefficient (C) measures.

Table 2. Application of chi-square test of independence and contingency coefficient (C).

Discussion

This study focused on the barriers and drivers encountered by the implementation of CSR in international shipping and, in particular, by shipping companies operating in the tanker and dry bulk maritime sector. As indicated by the literature review, nowadays, there are significant arguments and developments that urge the application of CSR in the shipping industry. However, contrary to our initial argumentation, the quantitative analysis showed that companies rank the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment as the sixth hierarchical factor (23%) that discourages the adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme. Similarly, alternative hypothesis H1 was rejected (p = 0.250 > 0.05). Such a finding is, potentially, explained by the judgment that shipping operations have, since a long time, been regulated by several Codes, Conventions and other maritime industry Standards. Therefore, companies place most of their efforts to cope with such regulatory burden, rather than advancing business through the implementation of CSR concept and practices (Yuen and Lim Citation2016). In addition, the low rate of companies’ certification against a CSR Standard (2%) and the low percentage of companies that generate a stand-alone CSR report (16%) demonstrate that CSR in the shipping sector still maintains a voluntary and informal character. Further to that, the, relatively, recent to the shipping industry (tanker and dry bulk sector), introduction of CSR notion justifies the fact that companies have not developed yet adequate knowledge over CSR principles and standards. Moreover, such recent application of CSR in shipping is logical to be supplemented by the lack of in-depth research to reveal and notify about the long-term benefits and value that CSR can bring to the organization (Lund-Thomsen, Poulsen, and Ackrill Citation2016). Therefore, in such a, somewhat, immature and emerging ground of maritime CSR, the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment is, subsequently, perceived as secondary barrier to discourage CSR implementation.

According to the literature review, adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme has proved to be a useful tool in the hands of organizations and supplement their attempt to manage relationships with stakeholders (Kunnaala, Lappalainen, and Storgärd Citation2013). Research findings lend support to our literature review assumptions by backing the view that shipping companies recognize the increased trust and improved company’s image and relationships with stakeholders as a significant benefit to be accrued by the implementation of a CSR policy and reporting programme. Similarly, alternative hypothesis H2, has been verified (p = 0.005 < 0.05). As a matter of fact, shipping companies have been, regularly, dealing with a variety of stakeholders, such as Flag Administrations, Port State Controls, Labour Unions and Industry Associations (Roe Citation2013). In that sense, and among increasing pressures and regulatory developments, stakeholders have raised their expectations for greater accountability, environmental consciousness and operating efficiency. Further to the stakeholder issue, company’s employees are considered to be important stakeholders. As per our findings, CSR is perceived to increase trust and improve relations between company and its employees and, therefore, such element should be carefully weighted by management. Therefore, assessing and eliminating risks ensued by the interaction with those entities (such as, loss of trust and commercial viability, detention of a ship and damage of company’s image, imposed fines from statutory violations, etc.), is imperative in order to ensure business viability (Poulovassilis and Meidanis Citation2013). Moreover, increased customer trust and improved image and reputation are perceived as significant gain that motivates shipping companies to implement CSR (Kunnaala, Lappalainen, and Storgärd Citation2013). In line with this assumption, our study findings have also identified a strong positive relationship between CSR adoption by companies and the increased trust and improved company’s image and relationships with its stakeholders (C = 0,488). Such result implies that a more positive and encouraging attitude of key maritime stakeholders towards CSR would, positively, motivate and boost CSR adoption by shipping companies.

Implications, limitations and future research

Implications

This research addressed the barriers and drivers associated with the implementation of CSR in the maritime sector. Given the fact that this is one of the few studies that have investigated CSR drivers and barriers in the tanker and dry bulk shipping sector, it has contributed to the limited former research and enhanced our knowledge in that area. First, based on the research findings, this study advances theoretical knowledge by clarifying that the lack of corporate culture and senior management commitment is not perceived as major restricting factor to CSR implementation. In contrast, lack of adequate knowledge on CSR theme and unawareness on the benefits that can bring to the company, are highly viewed as barriers to CSR initiatives. Moreover, in the area of driving factors, our knowledge is enriched from the fact that stakeholders turn out to be a key driving feature to stimulate CSR implementation. Second, research findings and output from consequent deductions can be fruitful for policy makers. Being mindful of this study, policy makers can direct their efforts and formulate policy that deal with the core of the issue. As such, they can develop programme that assist shipping companies to overcome their restricted knowledge and lack of in depth familiarization with CSR subject. Furthermore, the benefits to be accrued by CSR engagement can be used by policy makers as a mean to promulgate CSR in shipping. In particular, benefits that lay in the area of stronger relationships and improved company’s image with stakeholders should be further promoted and urged in shipping. Third, understanding drivers and barriers stressed in this study, ship managers become aware and can, therefore, try to find for solutions that overcome their weaknesses. Their focus should be in the area of CSR training and education, along with the identification and appreciation of the long-term benefits that CSR policy and reporting can bring to their business sustainability. Likewise, stakeholder engagement and collaboration, accompanied by effective communication and reporting of their CSR activities, should be seen as important driving factors and areas of further improvement for effective CSR implementation.

Limitations and future research

Despite the above contributions, there are some limitations to this study that need to be considered. Firstly, applicability of the results is limited to the context of a single group, namely, shipping companies. Therefore, future study is recommended with the aim to expand research sample range and investigate CSR perceptions and present expectations of other maritime stakeholders, such as, Flag Administrations, charterers, Port States, suppliers, etc. Secondly, due to the reason that the sample size was dedicated to one shipping sector (tanker and dry bulk), research findings do not allow comparisons with other shipping segments (i.e., cruise, container, offshore, etc.). As a result, the sample size and deductions are appropriate for grouped and not for subgroup data analysis. To overcome such limitation, future research is advisable by expanding the sample scope and, therefore, taking into account other maritime segments. Thirdly, this study is not concerned with solutions to overcome CSR barriers. Moreover, it does not discuss methods to better manage and propagate benefits from CSR engagement. Thus, additional research is suggested with the aim to provide practical solutions to overcome identified barriers and uphold benefits to be emanated by effective CSR implementation.

Conclusions

This paper investigates and discusses perceived barriers and drivers to be encountered by CSR implementation in the tanker and dry bulk shipping sector. Contrary to other industries, where CSR is at a more advanced state, the shipping industry shows gradual signs of engagement with CSR activities. A contributory factor towards this direction has been the introduction of United Nation’s SDGs, which have already opened the door for governments to embed CSR management and reporting systems in their future regulations and policies. The IMO has been fully harmonized with such international trends and, through its positive thinking for a sustainable transportation system, has already envisaged its vision to diffuse CSR principles as the vehicle to the achievement of a sustainable shipping industry (IMO Citation2013).

From reviewing existing literature, seven barriers and six drivers were identified and, based on those assumptions, two research hypotheses were developed. According to study results, the lack of training, education and awareness on CSR benefits, along with the inadequate regulatory regime were highly identified as barriers to CSR engagement. Consequently, the lack of a corporate culture and senior management commitment was not perceived to be a significant contributory factor to discourage the adoption of a CSR policy and reporting programme. In terms of the benefits to motivate CSR undertaking, increased trust and improved relationships with stakeholders proved to be a substantial driving force. Additionally, improved ethics, economic transparency and relations with employees are highly ranked as CSR motivating factors.

A noteworthy implication of this study lays on the need to provide further education and training related to CSR theme. Empirical results suggest that shipping companies require more information and practical knowledge on CSR. Therefore, further instructions and guidance should be provided in order to facilitate effective CSR implementation, which should be not, necessarily, supplemented by the establishment of a new statutory CSR regime. Moreover, the limited knowledge of the long-term benefits that CSR can bring to an organization is another weighty element that discourages CSR undertaking and needs to be assessed. In contrast, effective stakeholders’ management and building of partnerships turns out to be a significant encouraging factor for CSR engagement. Policy makers should assess and promote this driving force and, along with the provision of customized guidance and training on CSR, assist maritime companies to cope with CSR challenges. Future research is recommended with the aim to provide solutions on how to overcome CSR barriers and, in addition, identify methods to, effectively, promote driving forces.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank shipping companies for participating in the survey and offering their valuable assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agudo-Valiente, J. M., C. Garcés-Ayerbe, and M. Salvador-Figueras. 2017. “Corporate Social Responsibility Drivers and Barriers According to Managers’ Perception; Evidence from Spanish Firms.” Sustainability 9 (10): 1821. doi:10.3390/su9101821.

- Alhaddi, H. 2015. “Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review.” Business and Management Studies 1 (2): 6–10. doi:10.11114/bms.v1i2.752.

- Aras, G., and D. Crowther. 2008. Corporate Social Responsibility. David Crowther, Guler Aras & Ventus Publishing Aps. London: Bookboon.

- Asif, M., C. Searcy, A. Zutshi, and O. A. M. Fisscher. 2011. “An-Integrated-Management-Systems-Approach-To-CSR.pdf, an Integrated Management Systems Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 25 February 2017. Accessed 25 March 2018. http://www.spolecenskaodpovednostfirem.cz/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/

- Bhagwat, P. (2011, March). Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the Articles and Case Studies: Inclusive & Sustainable Growth Conference (Vol. 1, No. 1).

- Brown, J. A., and W. R. Forster. 2013. “CSR and Stakeholder Theory: A Tale of Adam Smith.” Journal of Business Ethics 112 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1251-4.

- Coady, L., J. Lister, C. Strandberg, and Y. Ota. 2013. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in the International Shipping Sector. A Phase, 2.

- Daugherty, L. 2007. Defining Corporate Culture: How Social Scientists Define Culture, Values and Tradeoffs among Them. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Davis, K. 1973. “The Case for and against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities.” Academy of Management Journal 16 (2): 312–322.

- Emezi, C. N. 2014. “Corporate Social Responsibility: A Strategic Tool to Achieve Corporate Objective.” Responsibility & Sustainability 2 (3): 43–56.

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Employment. (2001). Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility: Green Paper. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Fafaliou, I., M. Lekakou, and I. Theotokas. 2006. “Is the European Shipping Industry Aware of Corporate Social Responsibility? The Case of the Greek-Owned Short Sea Shipping Companies.” Marine Policy 30. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2005.03.003.

- Gligor-Cimpoieru, D. C., and V. P. Munteanu. 2015. “CSR Benefits and Costs in a Strategic Approach. Annals of the University of Craiova.” Economic Sciences Series 1 (43): 93–103.

- Hakala, S. 2015. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Culture in Corporate Restructuring - The Case of an Insurance Sector Acquisition.” Uppsala. http: //stud.epsilon.slu.se.

- Hoekstra, R., J. P. Smits, K. Boone, W. van Everdingen, F. Mawire, B. Buck, and K. Kriege (2014). Reporting on Sustainable Development at National, Company and Product Levels: The Potential for Alignment of Measurement Systems in a Post-2015 World. Rice terraces growing the improved Biramphul-3 variety of rice. This variety was developed together with farmers, using a participatory plant breeding methodology. Begnas Village, Kaski District, Nepal. Credit: Bioversity International/J. Zucker.

- International Maritime Organization. 2013. A Concept of a Sustainable Maritime Transportation System, Sustainable Development: IMO’s Contribution beyond RIO+20, Published on World maritime Day.

- Juščius, V., A. Šneiderienė, and J. Griauslytė. 2014. “Assessment of the Benefits of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports as One of the Marketing Tools.” Regional Formation and Development Studies 11 (3): 88–99. doi:10.15181/rfds.v11i3.612.

- Kakabadse, N. K., C. Rozuel, and L. Lee-Davies. 2005. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Stakeholder Approach: A Conceptual Review.” International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics 1 (4): 277–302. doi:10.1504/IJBGE.2005.006733.

- Kunnaala, V. H., J. Lappalainen, and J. Storgärd. (2013, June). Corporate Social Responsibility in the Baltic Sea Maritime Sector. In IMISS2013-Proceedings of the international scientific meeting for corporate social responsibility (CSR) in shipping, 2nd international maritime incident and near miss reporting conference (pp. 11–12). Kotka, Finland.

- Kurucz, E. C., B. A. Colbert, and D. Wheeler. 2008. “The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility.” In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, edited by A. Crane, D. Matten, A. McWilliams, J. Moon, and D. S. Siegel. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211593.003.0004

- Kytle, B., and J. G. Ruggie. 2005. “Corporate Social Responsibility as Risk Management: A Model for Multinationals.” Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper No. 10. Cambridge, MA: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Comments may be directed to the authors.

- Laudal, T. 2011. “Drivers and Barriers of CSR and the Size and Internationalization of Firms.” Social Responsibility Journal 7 (2): 234–256. doi:10.1108/17471111111141512.

- Lee, M., and H. Kim. 2017. “Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea.” Sustainability 9 (10): 1883. doi:10.3390/su9101883.

- Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Chi-square contingency. Accessed 10 September 2018. https://www.empirical-methods.hslu.ch/decisiontree/relationship/chi-square-contingency/

- Lund-Thomsen, P., R. T. Poulsen, and R. Ackrill. 2016. “Corporate Social Responsibility in the International Shipping Industry: State-Of-The-Art, Current Challenges and Future Directions.” The Journal of Sustainable Mobility 3 (2): 3–13. doi:10.9774/GLEAF.2350.2016.de.00002.

- Mbogoh, E., and M. Ogutu. 2017. “Challenges of Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies by Commercial Banks in Kenya.” Journal of Business and Strategic Management 2 (2): 1–16.

- McElhaney, K. 2009. “A Strategic Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility.” Leader to Leader (2009 (52): 30–36. doi:10.1002/ltl.327.

- McHugh, M. L. 2013. “The Chi-Square Test of Independence.” Biochemia medica: Biochemia medica 23 (2): 143–149. doi:10.11613/issn.1846-7482.

- Moir, L. 2001. “What Do We Mean by Corporate Social Responsibility?” Corporate Governance: the International Journal of Business in Society 1 (2): 16–22. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000005486.

- Network for Business Sustainability, A Systematic Approach to Stakeholder Engagement, like the One Outlined in This Guide, Can Bring Genuine Business Benefits. NBS 14 September 2012. Accessed 10 March 2018 http://nbs.net/wp-content/uploads/Community-Engagement-Guide.pdf

- O’Donnell, O., and R. Boyle. 2003. Understanding and Managing Organizational Culture.

- O’Rourke, D. 2004. “Opportunities and Obstacles for Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in Developing Countries.” The World Bank Group Œ Corporate Social Responsibility Practice Mar 27: 39–40.

- Okoye, A. 2009. “Theorising Corporate Social Responsibility as an Essentially Contested Concept: Is a Definition Necessary?.” Journal of Business Ethics 89 (4): 613–627. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-0021-9.

- Ouchi, W. G., and A. L. Wilkins. 1985. “Organizational Culture.” Annual Review of Sociology 11 (1): 457–483. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.11.080185.002325.

- Poulovassilis, A., and S. Meidanis (2013). Sustainability of shipping–Addressing Corporate Social Responsibility through Management Systems. Saatavilla. Accessed 02 August 2013] http://www.commonlawgic.org/sustainabilityof-shipping.html

- Progoulaki, M., and M. Roe. 2011. “Dealing with Multicultural Human Resources in a Socially Responsible Manner: A Focus on the Maritime Industry.” WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs 10 (1): 7–23. doi:10.1007/s13437-011-0003-0.

- Roe, M. (2013). “Professor, Plymouth University, Maritime Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility in Shipping – Process Rather than Formimiss 2013.” Proceedings of the International Scientific Meeting for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Shipping 2nd International Maritime Incident and Near Miss Reporting Conference, Kotka, Finland, 11–12 June 2013

- Shen, L., K. Govindan, and M. Shankar. 2015. “Evaluation of Barriers of Corporate Social Responsibility Using an Analytical Hierarchy Process under a Fuzzy environment—A Textile Case.” Sustainability 7 (3): 3493–3514. doi:10.3390/su7033493.

- Soiferman, L. K. 2010. “Compare and Contrast Inductive and Deductive Research Approaches.” Online Submission.

- Sowden, P., and S. Sinha. 2005. Promoting Health and Safety as a Key Goal of the Corporate Social Responsibility Agenda. HSE Books.

- Steurer, R. 2010. “The Role of Governments in Corporate Social Responsibility: Characterising Public Policies on CSR in Europe.” Policy Sciences 43 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1007/s11077-009-9084-4.

- Swanson, D. L. 2008. “Top Managers as Drivers for Corporate Social Responsibility.” In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, edited by A. Crane, D. Matten, A. McWilliams, J. Moon, and D. S. Siegel. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211593.003.0010

- Tasgit, Y. E., F. K. Şentürk, and E. Ergün. 2017. “Corporate Culture and Business Strategy: Which Strategies Can Be Applied More Easily in Which Culture?.” International Journal of Business and Social Science 8 (6): 80–91.

- Timane, R. 2012. “Business Advantages of Corporate Social Responsibility: Cases from India.” SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2180500.

- UNIDO Brussels - United Nations Industrial Development Organization. CSR will help enterprises achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Posted by UNIDO 9 February 2015. Accessed16 June 2018 https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/unido/blog/csr-will-help-enterprises-achieve-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs

- Valkovičová, M. 2018. “Barriers of Corporate Social Responsibility Implementation in Slovak Construction Enterprises.” International Journal for Research in Social Science and Humanities (ISSN: 2208-2697) 4 (1): 12–22.

- West, B., C. Hillenbrand, and K. Money. 2015. “Building Employee Relationships through Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Social Cynicism and Reward for Application.” Group & Organization Management 40 (3): 295–322. doi:10.1177/1059601114560062.

- Yuen, K. F., and J. M. Lim. 2016. “Barriers to the Implementation of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility in Shipping.” The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 32 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.ajsl.2016.03.006.