1. Introduction

As Carlo Ginsburg recently stated,

The use of war as a metaphor, during Covid-19 circumstances, set the stage for the ways in which new technologies limit individual freedoms. One could argue that there is enough control already, especially in authoritarian regimes but, as the Italian proverb says, il peggio non è mai morto (things can always get worse).

Also, staged and “performative” practices have become a tool of sociological and political activism, beginning with Erving Goffman’s work on the presentation of the self and the everyday use of masks in the social stage. I have combined these two scenarios: one is illegitimate (war), but widely invoked by the media, politicians and experts, and the other less controversial (the theatrics), though viewed as esoteric to those who are not qualified social scientists. Allow me to explain. I propose to examine the way in which the pandemic is presented as a public health issue. The strategies and tactics used to tackle the pandemic reproduce a particular way of conceiving the relationship between science, experts, citizens and politics. For this reason, we must identify the actors and characters of this drama; who are “the stars,” the cast, the extras and the technical teams without whom there is no spectacle? Who holds the authorized voice? Is it that only select characters can contribute with their opinion and advice? As in any game, everyone is assigned a role to play, but what the pandemic has shown is the deep interconnection between the actors; from hospitals and schools to stock exchanges and tourism, to racism and gender and class inequalities. This confluence of locations and actors has directly challenged democracy. We find ourselves in a state of exception that has legitimized the power and influence of experts and politicians, although society’s daily actions and organization play a central role in the problem. In short, these metaphors can be summarized regarding how power is exercised in an apparently militarized theater of operations.

2. The characters and the actors

Let’s review the actors. Of course the virus is a protagonist, even if it is a non-human actor in the dense network of this plot. SARS-Cov2, the virus that produces COVID-19, is the central character of this story. It is the star of the play, even though it communicates through others, like a specter that requires a medium. At this point in the game, we “social specialists” will have to be infinitely more modest and point out that, even without a conscience, it is not only an actor but also an agent of social change. I must say that, in contrast, social scientists, have been left without a script; those of us who should be alongside our colleagues in the health and medical sector are crouched over.

On the “front line” are the actors in the health sector, as the media and government tell us. Those leading the operations against COVID-19 are, in the social imagination, the doctors. They are the ones who directly study and observe how the virus moves, thus they are assigned the role of its main interpreters. Every day they “fight” and/or “negotiate” with it by the beds of those who have fallen ill. Their instruments of deterrence are the Intensive Care Units (ICUs) equipped with respiratory ventilators, oxygen, monitors, the energy system that keeps them functional, etc. Doctors, who are the equivalent of captains, lieutenants and colonels, are also present carrying their “weapons” and masks as they courageously fight shoulder to shoulder with their troops. In the vast majority of countries, they are as unprotected as their technical colleagues. They form “armies” that resemble those from the Battle of Ypres during World War I, where chemical warfare was born.

Beside them, or hierarchically speaking below them, are the production, support and logistics teams: nurses, stretcher bearers, ambulance drivers, cleaners … Although they make every step of the operation possible, they work anonymously, without voice or vote. They have the highest number of patients per capita under their care, although health demographics vary substantially between countries. Peripheral nations that are members of the OECD, such as Colombia and Brazil, have more doctors than nurses which exposes the poor social recognition of technical work – a characteristic of segregated and inequitable societies. For example, there are 5 nurses for every 10 doctors, according to their Ministry of Health. The average among the “core” countries within the same group, that is to say the truly rich ones, is 1 doctor for every 8.8 nurses. In war terms, they would be the equivalent of soldiers and sailors, some with a higher degree of specialization, such as Corporals. If it were a movie, their names would most likely appear in the credits at the end – in small, unreadable letters. Although their exposure to the virus is statistically greater, this “troop” is comprised of an amorphous, indistinguishable, invisible body; that is, not of individuals. Indeed, rarely is a soldier or a nurse interviewed, unless they are experiencing a serious injury and so they are visited by an officer. They are never consulted for an opinion that represents anything beyond their “personal experience,” as if they do not have the ability to think and only make automatic decisions without any useful knowledge. They respond to doctors’ orders and directions, despite knowing the patients best and having direct contact with the daily ravages of the “enemy” on their bodies. They are not asked because they are only “technicians”; supporting actors. Certainly gender and social class are determining factors in defining who has an authoritative opinion here. Nurses are viewed as “mothers” or “nuns” who accompany the sick, while drivers and stretcher-bearers are workers. Doctors, on the other hand, are the courageous and cunning warriors.

The patients are the “civilian casualties.” They appear in charts and data. Stalin is credited with the phrase “one dead is a tragedy; a million dead is a statistic.” He was right as it applies in both war and epidemics. The victims of COVID-19 are anonymous, they don’t even have faces, their identity is erased when the camera’s focus is on them from inside coffins and in bags or inside pits that resemble mouths that invite us in. Their voices and those of their families are also sporadic and do not carry much weight within the script mainly because it is assumed that they do not have the proper knowledge or understanding. Nevertheless, the disease occupies their bodies. They are the embodied virus that expresses itself through their organs; their bodies are the ones that know the pain, the terror of death that caresses their heads with every exhalation, the relief of recovery as well as the consequences of COVID-19 and its treatments. Their position locates them in a place of privilege that gives them access to a certain knowledge as their body speaks, and so it is used to test vaccines and experiment drugs, which is what they have been reduced to. They are the ones who can best teach us what palliatives do and, above all, what treatments are most dignified and humane. But these characters are only interviewed through medical examinations. Although their bodies speak and express themselves through medical data and images, their mouths remain muted.

3. The invisible actors

In a recent interview, Pierpaolo Sileri, Italy’s deputy health minister, commented that the issue with the containment measures had been that the discussion among the doctors was made public and was not kept “behind closed doors” among specialists. This had confused people: “imagine that someone requires an operation for bowel cancer and that the board of doctors has a discussion about the different alternatives with the presence of the patient. That patient may decide not to have the operation and die.” Sileri is a politician, but he is also a surgeon and a professor at the University of Tor Vergata in Rome. It is not unusual to treat the patient as ignorant and thus must heed to what the specialists say. Specialists tend to see them as invisible actors, represented by tables, charts and coefficients.

But if we advocate for a biopolitical democracy, where our body is sovereign and inalienable, we have every right and duty to participate in the discussion about our state of wellbeing; where the power politics and the State also operate. We all have gained expertise through our experience, so long ignored by modern science. Just as those who speak out in defence of the moors do not have to be ecologists nor should we pretend that, in order to discuss experimental therapies and medicines, we have to have the title of doctor. They have vast knowledge but a knowledge that is also limited. In short, we must recognize that we are all ignorant to different things.

The point is that citizens are not passive actors of medical practices. We are all more or less undisciplined regarding a doctor’s recommendations. We supplement medicines with homeopathic treatments. We smoke, even if we have high blood pressure and the doctor tells us that we are at high risk of a heart attack. We seek second and third opinions and then decide which diagnosis we believe best suits us. We can even hesitate to allow our daughters to be vaccinated against the human papillomavirus. In short, we are active actors capable of changing the development and course of the story, especially when the play does not have an a priori defined script. On many occasions we make mistakes but, even if we are treated as “extras,” we are still supporting actors.

4. Wars, intelligence and social sciences

Who is asked to do the evaluation and prepare the scenarios for strategic management? In war, generals and admirals are assigned these duties. In the case of COVID-19, it has been the epidemiologists and the virologists who provide detail and expertise on the virus. Although they do not make the final decisions, they are the only ones heard by those who do: the politicians, the ones who do not directly “talk” to the virus, but have the power to send troops, manage logistics, direct the war economy and implement coercive measures. While the politicians are, in that sense, the directors and producers of the film, the epidemic specialists propose the possible alternatives through formulas and graphic data – often with unreliable statistical evidence. It is at their discretion to adopt policies that call for individual or collective isolation and to underline the “protocols” (the most pronounced and least understood word during this pandemic) of biosecurity. Thankfully, as they do so, they help prevent mass contagion. But the reality, on which their efforts depend, finds loopholes through “people’s ignorance and irresponsibility.”

Cultural heritage and social memory have an important influence in the local evolution of the pandemic. We see it every day all over the world, from South Korea, where people have learned from the lessons of their own history to contain the virus, to the United States, which is losing its third war.

Indeed, the war on drugs declared by Richard Nixon, although it had an obvious racial and class undertone, has been conserved on the basis that repression and the total elimination of psychoactive substances will solve the social issues in question. The consensus among those who have studied the history of drugs (from coffee to heroin) points to the false premises of this policy. Evidently, this policy ignores the strategies and motivations of both, narcos and consumers.

The war in Vietnam was also lost by the US due to their complete reliance on their technical and scientific capabilities. I bring this topic to discussion because the way it became a reality resonates with the current situation. In the 1960s, the Department of Defense assembled a team of engineers and mathematicians to statistically evaluate the development of military action in real time. They collected casualty figures and data, active combatants, the enemy's firepower as well as their own, access to logistics and infrastructure, etc. Everything quantifiable was calculated and stored on magnetic tapes to be analyzed with mathematical methods of game theory, hoping that graphs would point the way to victory. The Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara (an economist with a curriculum in mathematics and ethics, a professor of numerical methods in business administration and an expert in operational analysis), was a promoter of this strategy and would request this information daily from the battalions who had to send immense amounts of data to be processed at the Pentagon. Although the data pointed to the fact that it was impossible for the National Vietnam Liberation Front to win in the face of the overwhelming technical superiority of the American army, the defeat was both painful and humiliating. In his “memoir” (In Retrospect: the Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam), McNamara accepts that two mistakes were made that proved decisive: (1) underestimating Vietnamese nationalist sentiment by reducing it to the logic of the Cold War against communism and (2) minimizing the effect of the government’s discredit on a huge number of American citizens, especially among the middle class. Neither could be interpreted from the charts and graphs; or perhaps they could have been glimpsed over but they did not have experienced interpreters who could understand what was happening. Too much “military intelligence” and not enough “social.” In fact, that has been one of the reasons why defeat remains incomprehensible to the United States public and experts alike.

Resistance to wearing masks and obeying confinement is not a matter of ignorance but of social practice. To reduce it to a social deviation is to repeat the mistakes presented in the Third World during the Cold War. How it would happen, on what scale and in what places was not foreseeable, but spontaneous civil disobedience was inevitable in the light of what we know about human behaviour from sociology, psychology, social work, history, anthropology and philosophy. In other words, it was evident to the human and social sciences, disdained by politicians who believe there is an excess in countries that need, above all, natural (applied) scientists and engineers (it has even been said that what Latin America needs are “engineer presidents”). C.P. Snow’s tale of “the two cultures” – the debacle of the British empire was due to the fact that the Imperial bureaucracy was led by “humanists” and not by engineers and scientists – attests to a long anti-historical tradition. For years, the (un)usefulness of the social sciences has been discussed in prestigious universities around Europe and the United States. Several “social studies of science and technology” programs, to cite one example relevant to the present situation, have been halted or are under permanent threat.

There is one exception to this tragedy within the social sciences: economists. They form part of the cast and even play as protagonists. Their fight is geared against the “epidemic” that attacks the markets. Their weapons are also “quantitative narratives,” that are made up of tables, algorithms, formulas and graphs. Of course they are necessary, for the reason that they have a level of experience and knowledge that they have been cultivating for decades (not centuries, as some believe) about the how’s of macroeconomics, but the scope of their understanding of social reality is far from complete and, although they acknowledge this, they remain isolated from their colleagues.

That brings us to the actors who were not selected or who have not auditioned.

The military knows very well that, especially in irregular warfare, without intelligence and counter-intelligence it is not possible to win and, therefore, it must allocate significant amounts of resources by forming groups of experts in psychological operations. The priority is undoubtedly to “win the hearts and minds” of the civilians but they must also discern the ways in which the population will react to attacks, counter-attacks and casualties, as well as the morale of citizens, troops and victims, of both their own and those of others. Here again, the war analogy touches on dangerous territory because of the resource having been systematically abused. However, we must also acknowledge that there have been successful operations as a result of it.

In the “war against COVID-19,” “intelligence” and “counter-intelligence” have an essential ally in the social studies of science and technology. It should be noted that these academics are not wise enough to advise the State, nor are they experts in the workings of society. In fact, they can serve as a variation of “counter-expert” (perhaps because of this role of being the saboteurs of the party, they are not invited). Their job is to unravel the logic and practices of those who abrogate the monopoly of knowledge. They do this by trying to understand why different cultures, communities, individuals and states exhibit distinct behaviours in similar situations. Since the 1960s, they have suspended research that does not include the participation of communities. Not only do they observe them but they also include them in their analysis with the use of methodologies such as the “Participatory Action Research.” They can therefore act as facilitators between experts and laymen.

They have also studied scientific practices, i.e. the relationships between knowledge, expertise, politics and cultures. We know that the objectivity of science is the expression of the society in which scientists reside, but that does not make it any less valid because its critics also draw from the same social source. If we are going to be meticulous, the criticism towards science also requires criticism towards its skeptics. That makes the social study of science indispensable. It may be that there is a basis for unmasking the fake news. The tables and data are loaded with moral values and cultural biases, but at the same time the “Merchands of Doubt” are knowingly dishonest, which makes them criminals. We could say that, in the game of checks and balances of knowledge, social scientists could provide aspects of judgment for decision-making by citizens and governments, fostering a dialogue with amateurs, that is, those who, although are not experts, have something relevant and pertinent to express. Some studies have made an attempt to visibilise the struggles of chronic disease patients for equity and social justice in the face of “politics of numbers and disease.” There is also evidence of the active participation of associations of patients in research projects on experimental treatments against HIV-AIDS. In other words, there is a history of actors such as those mentioned from which we could learn.

Simply put, social scientists should ensure that actors (the entire medical corps, health professionals, recovered patients, families …) are called upon. I think it is not an exaggeration to say that we social scientists have failed to act from within civil society to help defend it from the virus, from the general specialists, from the economic debacle and from the establishment of authoritarian regimes that are looming in this context of chaos. Do we not have anything to say? Does current reality surpass us and are we also only good at predicting the past? Perhaps not. We can help advocate the legitimacy of many silenced and potentially valuable voices.

In the 1990s, sociologists of scientific knowledge and natural scientists (mainly physicists) became embroiled in what came to be known as the “Science War”: it was a bitter controversy in which each side claimed a monopoly on knowledge about how science works. That war came to an end from the exhaustion as the debates ran their course. Fortunately, there were no winners or losers. Unfortunately, this resulted in empty agreements and no negotiations that would allow progress to be made in understanding a phenomenon as difficult as the production of “scientific facts” and their social use. Twenty-five years later, there are new generations who, it seems to me, are less radical and more open to the construction of spaces for discussion between former “enemies.”

COVID-19 has not materialized this collaboration, which cannot be postponed, although there are some efforts that are working in that direction. However, the pandemic has forced changes that act as catalysts, that is, accelerators of the process. The actor-virus SARS-CoV2 has forced us to explore virtual resources for education; many of which have been available and within our reach for several years. Without the crisis, this process of appropriating new ways of teaching and learning would probably have taken much longer due to the resistance of the academic communities – which are inherently conservative. More importantly, this new way of communicating has led to rethinking pedagogical practices which have been criticized for years. COVID-19 has ushered us into action, proving its role as the star of this drama.

I believe that the way in which research is conducted will also be transformed and, possibly, will encourage the formation of alliances that are needed to understand and act on the crisis. In addition to researching scientists, the social studies of science and technology will have to learn to collaborate with them in order to become more reflexive. Physicians, epidemiologists, bacteriologists, biochemists and others can learn from social scientists about the relativity of objectivity without their dependence on social contexts invalidating it. Moreover, such recognition can become an asset for its legitimacy and effectiveness.

Vice versa, us social scientists could become more humble and learn from the way knowledge is produced in laboratories and research centers. Social studies of science and technology have clearly shown that there are no isolated scientists. The greatest challenge that the construction of a “scientific fact” faces is the coordination between cultures with socially, technically and epistemologically different practices and languages. In the laboratory, significantly different communities must agree on the “translation” of information from one field of knowledge to another. Ironically, social scientists, who have shown the effectiveness of this form of social organization, are tremendously individualistic (as proven by the few papers written by more than one researcher). They too can investigate SARS-CoV2 and COVID-19, but I suspect they will have to do so alongside their medical and economic colleagues as well as by inviting the “invisible” actors.

5. The many faces of SARS-CoV2

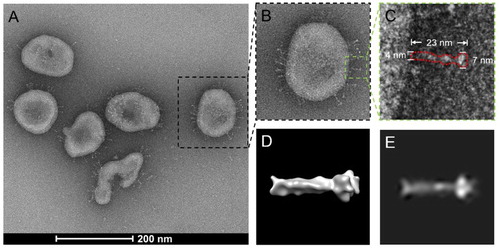

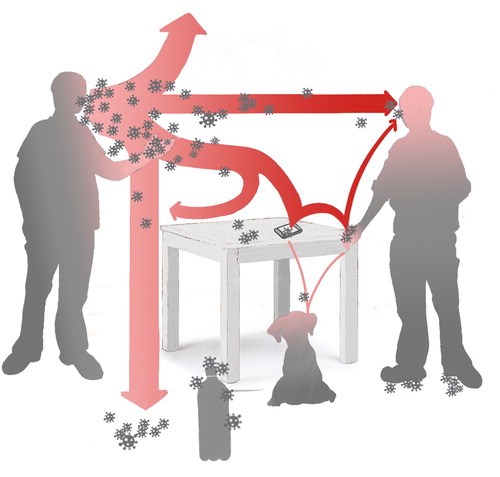

We can acknowledge that the virus is not one bug, but many, depending on who is studying and observing it. For a biochemist it is an object that kidnaps cells and interacts with other chemical and biological elements. SARS-CoV2 is “expressed” through its biochemical reactions with other physical actors and artifacts (e.g. centrifuges); they are “seen” through electron microscopes and brought to life with images that, with the help of artists, become the visual representation. In fact, there is not one, but multiple “photos” and images of the same object/virus (See –.), which leads us to ask what the “enemy” is really like, that is, who it is and what it does. The patients perhaps do not even know about SARS-CoV2, but they know very well the effects of COVID-19. They are not interested in the monitor or the molecular structure of the bug, they just want to breath normally again. Economists, workers, businessmen and finance ministers “observe” the virus through stock exchanges, investments, wages and macroeconomic indices. For States, the virus is a disruptive actor in their social order and governance. Pharmaceutical companies see a business opportunity and speculate on the stock market through premature results. Research centers and the pharmaceutical industry find fresh resources for their work thanks to the virus. For politicians, COVID-19 is seen as either an ally or an enemy for the upcoming elections.

Figure 1. Illustration created by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In https://www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/diseases-and-conditions/coronavirus/coronavirus-2020.html. Note ADGA: this is an open access image.

Figure 2. Instantaneous photo of SARS-COV2 taken with electronic microscope. Source: Liu et al. “Viral Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 with Post-Fusion Spike Revealed by Cryo-EM.” Preprint. March 5 2020. BioRxiv. Source subjected to Common Creative license.

Figure 3. Illustration of the “Structure of SARS-COV2.” Source: Estructura del coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Imagen: David S. Goodsell, RCSB Protein Data Bank; doi: 10.2210/rcsb_pdb/goodsell-gallery-019. Illustration available under Creative Commons license.

Figure 4. An infographic showing the paths that SARS-CoV-2 virions can use for transmission. Source: Patricia A.V. Piñero. “COVID-19 Contagion Paths.” April 10 2020. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COVID-19_Contagion_Paths.png. Free access image: Wikimedia states that: You do not need to obtain a specific statement of permission from the licensor(s) of the content unless you wish to use the work under different terms than the license states. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Reusing_content_outside_Wikimedia.

Figure 5. Coronavirus patients at the Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, Iran. Source: Mohsen Atayi. Mohsen Atayi. “Coronavirus patients at the Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, Iran.” March 1 2020. Wikimedia Commons. Ibidem. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Reusing_content_outside_Wikimedia.

The sick, the dead, the molecules, the ventilators, the vaccines, the doctors, the gross domestic product, the unemployment rates and the ICUs are all mediators for the virus. Similar to Rashomon the movie, all the actors have their own version of the crime, including the victim, who also communicates through a medium.

Perhaps the construction of the first atomic bomb can better illustrate what I mean. The bomb was a scientific problem of great interest to the physicists at Los Alamos, where it was designed. Truman’s reputation and prestige, seeing as he sought to be re-elected, depended on it. For the US military, she was a means to save the lives of American soldiers. For the Japanese, she was the end of the Empire and the war … The success and tragedy of the Manhattan Project – as the military operation of the atomic bomb was called – were not just “scientific” but social. There were multiple actors in that macabre play that premiered in Hiroshima, each with their own agenda. One and the same; one character with many faces of realization and tragedy.

It is evident that no social scientists were needed for those translations. However, since we are aware of the ways in which different communities organize and communicate, we could help to promote trading zones that would allow us to face a complex problem with an equally complex strategy that would enable us to seek and establish order in the midst of chaos.

6. Democracy and techno-politics

The future of many democracies depends on the experiences and interests of the “relevant actors” being represented in a parliament where knowledge is put to good use by all concerned.

The issue that I would like to touch on concerns the question of who the actors are in this story, without disregarding that there is an asymmetry in expert knowledge. A physician is best trained on how organs function, just as a physicist is better qualified to explain the half-life of a radioactive element and in what ways it can affect the environment. For this reason, their authoritative voice is privileged and may even carry greater relative weight when it comes to understanding a problem and presenting alternatives to solve it. The question here is what other persons can participate through some form of representation. In a legally democratic political system, we all have the right to partake in the decision-making process; either by voting for our representatives or directly through plebiscites and assemblies. This second option, participatory democracy, presents the risk of falling into the authoritarianism of the majority and manipulation of “public opinion,” which, thus, leads to the world of sheeps that Carlo Ginzburg talks about in a recent article. Representative democracy, on the other hand, is not perfect either because it is not exempt from similar forms of manipulation and, moreover, the connection between the citizen and the representative can be so tenuous that it only occurs during the electoral processes. When looking at scientific-political problems, one must be wary of falling into “scientific populism.” Public affairs, such as pandemics, are not exclusively scientific issues nor are they political, but rather techno-political. This implies defining the issue of who should be represented and with what level of authority. Likewise, it is very difficult to discern the mechanisms for electing representatives from different interest groups. However, as I pointed out, chronic disease patient associations have found ways to participate in their treatments. This is an example of how it is possible to give prominence to “invisible actors.”

I am not advocating civil disobedience in the face of preventive measures, or resistance actions against the State and the experts. I am describing a social phenomenon: people react, with or without permission, to any measure that concerns them. It would be better if they could take active part in the play without having to transgress the norms because there are not “trading zones” for new kinds of collaboration between laymen and experts.

When it is said that this “war” can only be won with the help of everyone, we must do so through mechanisms of social appropriation, understood not as scientific literacy which infantilizes those affected by the problem, but as processes of the co-production of knowledge and society. That is, as action where it is understood that we cannot make a clear separation between politics, science, technology and society. Each of us forms part of this unscripted play, therefore we are obliged to seek and express our own voice if we want to survive as individuals and as a community. I believe that we can only do this if we dare to think independently, with courage and without arrogance. The only thing that can protect us as individuals and as a society is not only to think and act for ourselves, but to also recognize that without the eyes of others, we are blind.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank David Edgerton, Carlo Ginzburg, Inés Elvira Mejía, Francisco Miranda M., Diana Obregón, Marco Palacios, Stefan Peters, Lisímaco Parra and Fernando Viviescas for comments and suggestions. Dani Moyano helped me with the English translation and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).