Abstract

The pandemic sweeping the world, COVID-19, has rendered a large proportion of the workforce unable to commute to work, as to mitigate the spread of the virus. This has resulted in both employers and employees seeking alternative work arrangements, especially in a fast-paced metropolitan like Hong Kong. Due to the pandemic, most if not all workers experienced work from home (WFH). Hence WFH has become a policy priority for most governments. In doing so, the policies must be made keeping in mind the practicality for both employers and employees. However, this current situation provides unique insight into how well working from home works, and may play a vital role in future policies that reshape the current structure of working hours, possibly allowing for more flexibility. Using an exploratory framework and a SWOT analysis, this study investigates the continuing experience of the employer and employees face in Hong Kong. A critical insight and related recommendations have been developed for future policy decisions. It will also critically investigate if this work arrangement will remain as a transitory element responding to the exceptional circumstances, or whether it could be a permanent arrangement.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19), a pandemic sweeping across the globe, has challenged society in ways once considered unimaginable, forcing people to reconsider a wide variety of practices, from work, to leisure, to basic travel and daily tasks. Not only has this had individual impacts, but it has also impacted countries as a whole from an economic standpoint, bringing an array of economic sectors to a complete standstill. While there was a lot anticipated and there were countless warnings, especially from those working in public health, the challenge remained as a substantial change which requires planning, training, and facilitating. While the society did mentally prepare, the extent and solution still remained unthinkable and remains to be a big challenge. COVID-19 is a new disease that has begun circulating in the human population since December 2019. It is part of the coronavirus family, the same group of viruses that caused the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in South East Asia in 2002 and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in 2012. Currently, the known main mode of transmission is through respiratory droplets, and hence is considered to spread through close contact with other people. At present, the only tools to combat the viral spread are using masks properly, introduction of social distancing measures, and practice of good hand hygiene (Centre for Health Protection [CHP] Citation2020a). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a global health emergency on 31 January 2020 (World Health Organisation Citation2020). Since then, the virus has spread rapidly.

The virus has vastly spread worldwide, with over 60 million confirmed cases and over 1.4 million confirmed deaths as of 26 November 2020, and the number has been increasing consistently (World Health Organisation Citation2020). As the coronavirus continues to spread across the world, some governments worldwide have imposed and re-imposed strict lockdowns with the closure of non-essential businesses and banned non-essential gatherings from keeping hospitals from the threats of being overwhelmed due to COVID-19. Many of their counterparts have urged their citizens to stay at home as much as possible and practice social distancing to limit face-to-face interactions with others. At this time, authorities and organizers of mass gathering events are encouraged to carry out a risk assessment in the context of the pandemic for their events to protect people from harm. For instance, the WHO has released a risk assessment tool for stakeholders to use to assess the safety of any mass gatherings that are to take place. This tool involves three pillars of assessment, namely: Risk Evaluation; Risk Mitigation; and Risk Communication. Once data is filled into these categories, data is automatically filled into a Decision Matrix which assesses the total risk score (from 0 to 5) against the total mitigation score (%) and categorizes the overall risk of transmission and spread from very low to very high. Besides, employers are also advised to carry out a coronavirus-specific risk assessment of the workplace, taking each individual into account, to determine the safety of their employees working on-site. Businesses in the UK are required to openly share the risk assessment results with the workforce (HM Government Citation2020). This might be because offices are among the top three places to get infected with COVID-19, according to Dr Zhong Nanshan, a renowned respiratory disease expert (Hong Kong Economic Times Limited Citation2020). If the risk is too significant, employers are forced to accept alternative working methods, by practicing social distancing at work or implementing WFH.

Before the pandemic, discussions on the future of work-life were unclear and often questioned. COVID-19 forced a decision upon people, and with the world having to adapt quickly, many businesses opted to try WFH. The WFH practices have been employed widely, as can be seen in the U.S., where studies show in May 2020, 35.2% of the workforce worked from home, an increase from 8.2% in February. Furthermore, 71.7% of workers that WFH found that they could work effectively (Bick, Blandin, and Mertens Citation2020). In some places, WFH guidelines were given by governments, where government employees WFH while advisory notices were sent to employers of private organizations, as a precaution to prevent further spread by reducing social contact (Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government [HKSAR Government] Citation2020a).

Before the pandemic, the idea of WFH was a fantasy to many people, but such practice was considered not practicable for heavily populated cities like Hong Kong. This is principally because home working requires a quiet and dedicated space to perform work duties, which can be a real challenge for those living in tiny homes. Hong Kong is undoubtedly famous for having tiny homes, in which the average living space per person was only 161 sq ft. in 2018 (Task Force on Land Supply Citation2018), which is about 25% lower than Tokyo and 60% lower than Singapore (Ng Citation2018). Over the years, there has been a belief throughout the city that workers need to be physically present in the office to carry out the job. Now that the pandemic has forced a trial run for WFH in the city, for many, it is their first time to work remotely and to a large extent it is proving to be successful. Therefore, a unique opportunity to assess the possibility of having WFH as one of the future working models for such a densely populated city has high impact. Being one of the first studies in this area, we aim to analyze three different dimensions. Firstly, this study attempts to enhance the understanding of WFH, including the factors that influence WFH and the practicality and effectiveness of this work arrangement. Secondly, the scrutiny of the WFH’s potential outcomes on workers’ work and life domains, such as flexibility and work motivation. Finally, our investigation in the context of Hong Kong adds distinctions to the record of Hong Kong’s response to the COVID-19 crisis, which is substantially believed to be victorious due to strong “community capacity” or social mobilization (Hartley and Jarvis Citation2020; Wan et al. Citation2020). The rest of this paper has the following structure. The next section discusses the COVID-19 pandemic and WFH in Hong Kong, with attention to WFH arrangements during the epidemic in Hong Kong. Next, in order to enhance the understanding of the WFH concept, this paper presents an overview of WFH. Subsequently, the framework of the study and a SWOT analysis for the investigation of WFH is presented, followed by a discussion of Hong Kong's WFH experience. The final section includes the conclusion, policy implications and recommendations.

COVID-19 pandemic and work from home in Hong Kong

Many places have been adopting different means to deal and defend themselves against the COVID-19 pandemic, and Hong Kong is no exception. Hong Kong was among one of the first places in the world hit by the disease, where the city announced its first confirmed case of COVID-19 as early as 23 January 2020 (HKSAR Government Citation2020b). Since the beginning of the outbreak, the city has experienced four waves of infections, and the third wave is by far the most severe while the fourth wave is being experienced at the time of writing. In response to the epidemic, Hong Kong has taken quite a different approach compared to its counterparts. The city has not enforced a complete lockdown; instead, a series of measures have been implemented, which include public-gathering limits, suspended schools, special work arrangements including WFH and remote working for civil servants and appeal to private sector organizations to make similar arrangements as far as practicable, etc. (HKSAR Government Citation2020c). At first, the city seemed to be able to contain the spread of the disease and keep its infection numbers relatively low. Prior to the third wave of infections, there was a relatively small number of infected cases and few deaths in the city (Cheng, Cheung, and Magramo Citation2020). Things gradually returned to normal, where schools reopened and restrictions on social distancing were eased. The city was hailed as a success when it came to managing the spread of COVID-19 (Marlow Citation2020; Saiidi Citation2020). Some gave credit to the quick action on the COVID-19 crisis of the city’s government. At the same time, others tended to give credit to the community, with the public having no confidence in the city’s government and taking matters into their own hands (Cheung and Wong Citation2020; Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute [HKPORI] Citation2020a). However, in early July, the COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong started soaring. The situation exponentially deteriorated, stricter measures were rolled out to control the spread of the virus, such as the new rules on mandatory mask-wearing in all public places, etc. (Ting, Cheung, & Cheng, Cheung, and Magramo Citation2020). However, some government regulations like the suspension of dine-in services sparked intense controversy, especially from those that could not WFH due to the nature of their work, citing inconvenience and lack of places to eat (Choy Citation2020). The government then backtracked and decided to resume daytime dine-in services merely a day after the new regulation came into force (RTHK Citation2020a). The infection finally began to go down in late August, some anti-epidemic measures were gradually eased. Unfortunately, the number of confirmed cases surged again since mid-November, with 6,040 confirmed cases recorded as of 27 November 2020, while the death toll climbed to 108 (CHP Citation2020c). The city has been struggling to cope with the fourth wave of infection at the time of writing.

Hong Kong, like most places, has long been following a standard practice to work in a formal office environment, where 85% of surveyed Hong Kong employees reported that they are required to work at the office during regular office hours with no flexible working options being offered, in a cross-regional survey on the global employment trend back in 2018 (Randstad Hong Kong, n.d.). It can be seen that only a small proportion of people had the experience and opportunities of WFH before the pandemic. The survey findings are consistent with a document prepared by the city’s government back in the early 2000s, suggesting that teleworking would not become the mainstream in Hong Kong in the short to medium term (Planning Department Citation2002). However, the spread of the coronavirus has, in fact, brought about unexpected changes to people’s lives in many ways, one of which is driving people worldwide to WFH, Hong Kong being no exception. At the start of the pandemic—the first wave of infection in Hong Kong—civil servants (excluding those providing emergency and essential public services) and publicly funded university staff were the first batch of employees allowed to WFH, as a measure to mitigate the spread of the virus. Some private companies, such as HSBC and Standard Chartered among many others, also allowed their back-office employees to WFH (RTHK Citation2020b). The decision to adopt special work arrangements is adjusted for each wave of the infection, depending on the severity, see .

Table 1. Timeline of Work from Home during COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

Working after the post-outbreak era may be the time to pay attention to the working alternative that organizations are going to take. For example, 9GAG, a Hong Kong based leading online platform, appears to be the first company in the city to shift toward WFH permanently (Chan Citation2020). Even more astonishing is that a survey conducted during the second wave of the infection in Hong Kong shows that most employees surveyed had experienced WFH for at least one day a week (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute Citation2020b), and expected to continue WFH for at least one or two days per week after the pandemic (Wong and Cheung Citation2020). The city has had the opportunity to experience a large proportion of the working population WFH, and this has triggered a new round of debate on the practicality of such work practice. Some have raised concerns on the productivity of employees (Gorlick Citation2020), while others have advocated that WFH not only enhances productivity of employees (Baker, Avery, and Crawford Citation2007), but also offers greater flexibility in work arrangements and fosters better work-life balance (WLB) (Dizaho, Salleh, and Abdullah Citation2017). WFH in Hong Kong, which was initiated in response to the pandemic, is in fact, being absorbed smoothly owing to the international standards of technology the people enjoy.

Work from home: an overview

WFH, is currently known as an alternative working to minimize the risk of COVID-19 infection. However, WFH is not new and has been brought to the attention of several schools of thought for many years. The WFH concept was initially mentioned by Nilles (Citation1988) dating back to 1973, known as “telecommuting” or “telework” (Messenger and Gschwind Citation2016). WFH has been defined in various terms over the four decades, namely remote work, flexible workplace, telework, telecommuting, e–working. These terms refer to the ability of employees to work in flexible workplaces, especially at home, by using technology execute work duties (Gajendran and Harrison Citation2007; Grant et al. Citation2019). Gajendran and Harrison (Citation2007) described telecommuting as “an alternative work arrangement in which employees perform tasks elsewhere that are normally done in primary or central workplaces, for at least some portion of their work schedule, using electronic media to interact with others inside and outside the organization,” notably, they indicated that “elsewhere” refers to “home” (1525).

A recent study by Dingel and Neiman (Citation2020) uncovered that 37% of the job could be completed at home during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., such as financial work, business management, professional and scientific services. Some jobs, especially those related to healthcare, farming and hospitality cannot be performed at home. Although the acceptance of WFH has increased worldwide, academics argue regarding its pros and cons.

WFH has beneficial effects for both employers and employees. The advantages, include and are not limited to reduced commuting time, avoiding office politics, using less office space, increased motivation, improved gender diversity (e.g. women and careers), healthier workforces with less absenteeism and turnover, higher talent retention, job satisfaction, and better productivity (Mello Citation2007; Robertson, Maynard, and McDevitt Citation2003). Studies indicated evidence for these benefits; for example, the research in the Greater Dublin Area by Caulfield (Citation2015) found employees saving travel time and value of travel time. Some studies point out that telework can reduce turnover rate and increase employees’ productivity, job engagement, and job performance (Collins and Moschler Citation2009; Delanoeije and Verbruggen Citation2020). Similarly, e–working can increase productivity, flexibility, job satisfaction, WLB, including reducing work-life conflict and commuting (Grant et al. Citation2019). Additionally, Purwanto et al. (Citation2020) argued that WFH could support employees in terms of flexible time to complete the work and save money for commuting to work.

Conversely, the drawbacks of WFH, include the blurred line between work and family, distractions, social isolation, employees bearing the costs related to WFH. According to Purwanto et al. (Citation2020), there are certain drawbacks of WFH, such as employees working at home have to pay for electricity and the internet costs themselves. Collins and Moschler (Citation2009) found that workers were isolated from their coworkers, and managers concerned about reductions in productivity while working from home. Moreover, the relationship between coworkers could also be harmed (Gajendran and Harrison Citation2007). Employees might be distracted by the presence of young children or family members while working at home (Baruch Citation2000; Kazekami Citation2020) along with blurred boundaries between work and family life lead to overwork (Grant et al. Citation2019). In a similar vein, the management of boundaries between work and family of remote workers studied by Eddleston and Mulki (Citation2017) revealed that WFH relates to the inability of remote workers to disengage from work.

Studies have shown that WLB can be enhanced by working from home. Similarly, Grant et al. (Citation2013) stated that e-working would improve WLB, and e-workers found it possible to combine work-life and non-work life. E–workers found that their productivity was improved by e–working (Grant et al. Citation2019). Bloom et al. (Citation2015) found job satisfaction to increase by working from home. WFH is also positively associated with family-life satisfaction (Arntz, Sarra, and Berlingieri Citation2019; Virick, DaSilva, and Arrington Citation2010). Kazekami (Citation2020) studied the productivity of workers in Japan and discovered that telework increases life satisfaction.

WFH has become a policy priority for most governments to cope with the pandemic. In doing so, the policies must be made keeping in mind the practicality for both employers and employees as there will be some consequences for the two groups in one way or another.

Work from home: a framework of investigation

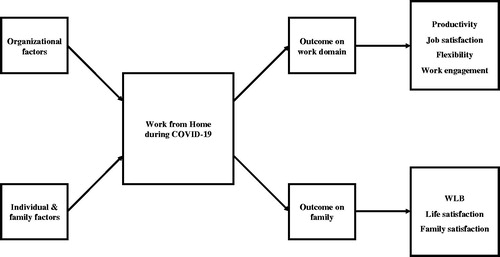

The framework for this present study was developed based on the review on WFH, teleworking, telecommuting, e–working, flexible workplace, and remote work. The framework is thus drawn to guide the investigation of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong, in order to examine if this work arrangement will remain as a transitory element responding to the exceptional circumstances, or whether it could be a permanent arrangement. Firstly, in the proposed framework, two factors—organizational and individual-family—are linked to WFH. The authors aim to scrutinize how these factors influenced WFH. Secondly, in order to explore the impacts of WFH on work and life domains, it is connected to the respective outcomes on work and life domains that are embodied in specific aspects. More descriptions of the elements in the framework as shown in , are described in the following section.

There are two main factors that will be taken into consideration by the workers when working from home. “Organizational factors” would initially be involved in the work of the employees. Studies discussed that organizational factors are crucial for WFH arrangements (e.g. Baker, Avery, and Crawford Citation2007; Grant et al. Citation2019). Examples include but are not limited to employers supporting employees demands while working from home, cost of facilities related to WFH, training in the use of technology, as well as organizational communication. Other support for the WFH arrangements, include employee well-being and IT support from the organization etc. (Baker, Avery, and Crawford Citation2007). Organizational trust and trust by managers are some other organizational factors. As found in previous research, organizational trust and trust by managers are correlated with the WFH outcome. The studies by Baruch (Citation2000), Grant et al. (Citation2019) and Baker, Avery, and Crawford (Citation2007) found that a culture of trust in an organization—trust by colleagues and managers—is needed for teleworking and e-working. Based on previous studies, these factors were found to be closely correlated with WFH.

As indicated in previous studies, WFH is influenced not only by organizational factors but also by “individual and family factors” (Baker, Avery, and Crawford Citation2007; Solís Citation2016). Baruch (Citation2000) suggested some factors that need to be addressed for teleworking, such as “self-discipline, self-motivation, ability to work independently, tenacity, self-organization, self-confidence, time management skills, computer literacy knowledge” (43–44). A study revealed that the number of working days and the time a person spent in teleworking also has an impact on work-family conflict (Solís Citation2016). In addition to individual factors, family factors also have an influence on WFH. For example, household characteristics such as size of the living area, number of family members sharing the same accommodation and the number and age of children in the household are considered as family factors influencing WFH (Baker, Avery, and Crawford Citation2007). Moreover, WFH can also be influenced by the individual working space available in the house and the number of people present when working at home (Baruch Citation2000; Shaw, Andrey, and Johnson Citation2003).

The outcome of WFH can be considered in two domains which are the outcomes on “work domain” and “life domain.” Research studies reveal that WFH has positive outcomes on work domain, i.e. productivity, job satisfaction, flexibility, and work engagement. Productivity was improved by adopting telework, e-working and telecommuting, particularly of creative tasks (Dutcher Citation2012; Grant, Wallace, and Spurgeon Citation2013). WFH is also believed to increase job satisfaction and studies have shown that the relationship between teleworking and job satisfaction is interrelated (Troup and Rose Citation2012; Bae and Kim Citation2016; Smith, Patmos, and Pitts Citation2018). WFH also impacts the flexibility and work engagement as it allows workers to enjoy more flexible time to complete their work and does not require them to follow office hours (Grant et al. Citation2019; Purwanto et al. Citation2020). WFH and teleworking also positively affect employees’ work engagement (Gerards, de Grip, and Baudewijns Citation2018; Sardeshmukh, Sharma, and Golden Citation2012). However, WFH has also been argued to have an adverse outcome on the work domain, which is negatively associated with work motivation, e.g. WFH can lose employees’ work motivation because they have to bear the cost related to WFH (Purwanto et al. Citation2020).

Studies indicated that WFH has both negative and positive outcomes on life domain. Life domain could include WLB, life satisfaction, and family satisfaction. WLB may refer to work-family interference, work-family balance, family satisfaction, and life satisfaction (Gregory and Milner Citation2009; Kalliath and Brough Citation2008). Some studies uncovered that WFH had negative effects on the domain of life. For example, Grant et al. (Citation2019) uncovered that e-workers find it difficult to manage boundaries between working and non-working time resulting in a tendency to overwork. Others uncovered that there were blurred boundaries between work and family life (Grant et al. Citation2013) and may lead to overwork and in turn reduce WLB. Nevertheless, several studies found that WFH is positively associated with family and life satisfaction (Eddleston and Mulki Citation2017; Virick, DaSilva, and Arrington Citation2010). Arntz et al. (Citation2019) discovered that WFH tends to increase childless male workers’ life satisfaction. Moreover, it has been found that WLB is also positively associated with life and family satisfaction (Chan et al. Citation2016; Noda Citation2020).

The exploitation of the exploratory framework combined with a SWOT analysis will help investigate the ongoing experience of employers and employees and further a good understanding of the real situation of WFH in Hong Kong.

SWOT analysis

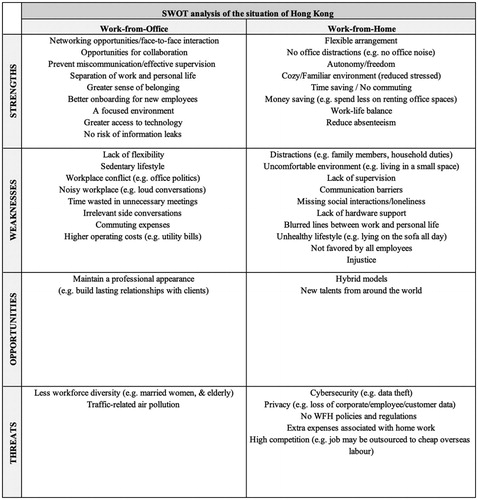

Based on the initial evidence of WFH adopted by the workforce coming from different sectors, Hong Kong does have the potential to make WFH far more commonplace, taking the availability of technology into account. The city is considered as one of the most technologically advanced places in the world, with approximately 92% of its population being internet users (The World Bank Group Citation2020). It is very likely that most people in Hong Kong already have the necessary technology, i.e. reliable internet connection, to WFH. However, it seems hard for majority of the population to carve out a dedicated workspace at tiny homes. Since WFH is relatively new for Hong Kong, it is essential to identify the potential and pitfalls of WFH by using a SWOT analysis that might help to scrutinize the WFH situation in Hong Kong. The analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of WFH with particular focus on Hong Kong, were carried out, as are presented in a self-explanatory .

Discussion

COVID-19 gave the world an option to experience WFH, which had long been a desired work option for many especially in a place like Hong Kong where increasingly dual family workforce exists. The responsibility of aged parents and/or young children coupled with demanding work environment has been a challenge questioning the WLB of Hong Kong workforce. Based on preliminary studies on the employers’ and employees’ reactions to WFH in Hong Kong, it appears that the initial reactions to the changed working format has been favorable. However, looking past this superficial satisfaction, there are many gaps in the current WFH structure, and consequently, there is more dissatisfaction with the lack of policies to conduct effective home working.

Hand in hand with the effectiveness of the WFH practices, the opinion of the people WFH is essential to consider. Looking at the opinions received in the early days of the practice, an overwhelming majority of opinions were positive. A study conducted in April 2020 showed that over 80% of workers preferred at least partial WFH measures in place, with numbers varying in how many days a week that should be, suggesting a preference for a mixed mode of working. The most common reasons for this, shown, were more time to rest (72.2% strongly agree), decreased work related stress (63.8% strongly agree), and improvement in WLB (60.7% strongly agree). Opinions also showed employers in a favorable light, with 45% of respondents agreed that employers provide adequate support to execute an effective WFH strategy (Wong and Cheung Citation2020). However, while this was the most popular opinion, it does not express the majority view, suggesting that even in the early days there was room to improve. This can be seen in the same study, with majority of respondents agreeing to all the challenges addressed, including lack of hardware, disturbance from family, and poor communication with colleagues. Another study highlighted the health benefits of WFH, with over 80% of workers feeling mentally relaxed while working at home. This study also highlighted workers favoring and supporting WFH measures (73%), flextime (83%), and compressed working hours (77%) (Sun Life Citation2020).

Despite the early overall favorability seen from Hong Kong workers for WFH practices, it is clear that there are glaring issues that need to be addressed. A study highlights unhappiness with the internal infrastructure, such as either no or limited access to resources such as office documents (FastLane Citation2020). This could suggest a level of ill preparedness for this situation, however considering this is a new work practice the degree of preparedness is limited, both for employers and employees. This has resulted in inconsistent or delayed output from the employees and lack of flexibility, and tolerance by employers. It can be argued that employers might have been making efforts, but there has been a lack of uniformity, with only 32% of employers investing in new forms of communication technology, and even less in other areas (FastLane Citation2020). Another study suggests that the unique working situation of Hong Kong makes WFH less favorable for workers, with workers missing the distinction of personal and professional spaces. The survey finds, “employees 35 years and older had to juggle between home and work commitments simultaneously”, citing a possible reason for this added difficulty being that people in this region tend to live in multi-generational households, which also leads to less space when compared to their western counterparts, hence creating many distractions and imbalance between work and home life. Furthermore, the same study finds that 68% of the workers missed going to the office and missed human interaction, the professional environment, and face to face interaction for better collaboration (JLL Citation2020).

Another evidence is that civil servants in Hong Kong were allowed to WFH during the city outbreak, various government departments provided information technology support such as newly installed computers, mobile devices or other equipment, software along with enhanced capacities of communications, networks, or databases for their staff to WFH efficiently. Similar to the studies by Baker, Avery, and Crawford (Citation2007), and Grant et al. (Citation2019) it is revealed that organizational factors such as support from organizations, influence WFH. However, there are many confidential documents which might not be convenient for the civil servants to access via the government intranets and servers through virtual private networks (VPNs) for delivering emails along with storage and retrieval of information when WFH (HKSAR Government Citation2020j). Further, as Baker, Avery, and Crawford (Citation2007) pointed out, WFH can be affected by individual and family factors. Some civil servants in Hong Kong have young children and as they WFH they had to look after their children (Tsang Citation2020). While WFH-related assistance from organizations exists, but workers may experience difficulties in accessing information from the organization and this might be challenging.

While the special work arrangement allowed people to WFH to mitigate the outbreak in Hong Kong, the current WFH procedure lacks clear guidelines. For instance, there was a controversy and confusion whether adverse weather conditions would require workers to work at home or would they be eligible for time off like it was in the traditional work arrangement (Ng Citation2020a). Thus clear guidelines or explicit direction is essential.

In addition to Hong Kong, there are other Asian countries which have experienced the new normal workplace, WFH. This has affected workers, both in work as well as personal spheres. In Singapore, WFH is seen to increase the workers’ stress even more, as is revealed by a study which revealed that WFH workers were more stressed than the COVID-19 front-line workers (Teo Citation2020). Similarly, in India, WFH made 67% of the people suffer from sleep deprivation especially during the period of lockdown and in the absence of maids to help with housework which resulted in their dealing with all the domestic tasks concurrently with their work (Times of India Citation2020). WFH employees in Hong Kong, as in Singapore and India, were found to experience more stress, fear regarding job security, felt anxious, lonely, burnt out. As evident from a survey conducted between May and July 2020 by the Mental Health Association of Hong Kong, 87% of respondents were found to have symptoms of stress (Ng Citation2020b; Tam Citation2020). WFH in the COVID-19 era seems to have many negative consequences on workers’ life domain. Nonetheless, through the time of the pandemic, WFH has reshaped the traditional way of working into a potential future of work.

Conclusion

Research make it evident that the once desired, highly favorable, WFH has not proved to be one of the best options for majority of Hong Kong workforce. Interest in WFH remains, but not in its current form. Better guidelines and policies from the government should be in place to properly regulate and make WFH feasible. One area of policy where planning and implementation is an absolute necessity is guidance into adapting to remote online work. The decision to suspend in-person meetings and working was implemented swiftly, but without any guidance, of how to do so. Workers are unaware about what WFH entails and lack resources required for this change, like software, access to official documents and proper working space. Proper training is required if this practice is to be a feasible option or the new normal. Possibly the working balance will be visible post-pandemic when WFH is not a forced mandate, rather a flexible option.

Recommendations

The below recommendations include a series of possible actions that could be taken by the Government to make WFH more feasible in a local context.

1. In the short run, the Government should consider:

• Introducing a formal WFH guideline for employees and employers;

• Taking COVID-19 risk assessment into account when developing the guidelines;

• Providing different guidelines to different sectors;

• Allowing employees’ expectations in the guidelines;

• Specifying minimal requirements for technology training for virtual office; and for technical facilities for WFH.

2. In the long run, the Government should consider:

• Reexamining the possibility of remote working to become the new normal;

• Reviewing the current labor legislation and to ensure the labor insurance policies are extended to home working;

• To encourage small and medium enterprises to adopt WFH measures by providing subsidy and other incentives;

• Strengthening the ongoing Distance Business Program; and

• To further promote family-friendly employment practices.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arntz, M., B. Y. Sarra, and F. Berlingieri. 2019. “Working from Home: Heterogeneous Effects on Hours Worked and Wages.” ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No. Mannheim, Germany, 19-015. Retrieved from 10.2139/ssrn.3383408.

- Bae, K. B., and D. Kim. 2016. “The Impact of Decoupling of Telework on Job Satisfaction in U.S. federal Agencies: does Gender Matter?” The American Review of Public Administration 46 (3): 356–371. doi:10.1177/0275074016637183.

- Baker, E., G. C. Avery, and J. Crawford. 2007. “Satisfaction and Perceived Productivity When Professionals Work from Home.” Research & Practice in Human Resource Management 15 (1): 37–62.

- Baruch, Y. (2000). Teleworking: benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 15(1), 34–49. doi:10.1111/1468-005x.00063

- Bick, A., A. Blandin, and K. Mertens. 2020. “Work from Home After the COVID-19 Outbreak.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP15000. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3650114

- Bloom, N., J. Liang, J. Roberts, and Z. J. Ying. 2015. “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130 (1): 165–218. doi:10.1093/qje/qju032.

- Bray, C. 2020. “HSBC to Let Hong Kong Employees Work Up to Four Days a Week at Home.” South China Morning Post, November 18. https://www.scmp.com/business/banking-finance/article/31,10,379/hsbc-let-hong-kong-employees-work-four-days-week-home

- Caulfield, B. 2015. “Does It Pay to Work from Home? Examining the Factors Influencing Working from Home in the Greater Dublin Area.” Case Studies on Transport Policy 3 (2): 206–214. doi:10.1016/j.cstp.2015.04.004.

- Centre for Health Protection. 2020a. Frequently asked questions on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Accessed 9 June. https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/features/102624.html#F

- Centre for Health Protection. 2020b. Latest situation of cases of COVID-19 (as of 9 August 2020). Accessed 9 August. https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/local_situation_covid19_en.pdf

- Centre for Health Protection. 2020c. Latest situation of cases of COVID-19 (as of 19 August 2020). Accessed 19 August. https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/local_situation_covid19_en.pdf

- Chan, S. 2020. 9gag announces work from home forever. Accessed 25 May. https://www.humanresourcesonline.net/9gag-announces-work-from-home-forever

- Chan, X. W., T. Kalliath, P. Brough, O.-L. Siu, M. P. O’Driscoll, and C. Timms. 2016. “Work–Family Enrichment and Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Work–Life Balance.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27 (15): 1755–1776. doi:10.1080/09585192.2015.1075574.

- Cheng, L., E. Cheung, and K. Magramo. 2020. Coronavirus: Cluster at Hong Kong elderly care home where operator may have ignored guidelines pushes number of new cases in city to 24. Accessed 8 July. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3092289/coronavirus-hong-kong-has-another-14-cases-covid

- Cheung, T., and N. Wong. 2020. Coronavirus: Hong Kong residents unhappy with Covid-19 response – and surgical masks one big reason why, Post survey shows. Accessed 1 April. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3077761/coronavirus-post-poll-shows-hong-kong-residents-unhappy.

- Choy, G. 2020. “Coronavirus: Hong Kong’s Workers Have Lunch in Parks, Construction Sites, as Dine-In Ban Kicks in Amid Third Wave.” Accessed 29 July. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/30,95,175/coronavirus-hong-kongs-workers-have-lunch-parks

- Collins, J. H., and J. J. Moschler. 2009. “The Benefits and Limitations of Telecommuting.” Defense AR Journal 16 (1): 55–66.

- Delanoeije, J., and M. Verbruggen. 2020. “Between-Person and Within-Person Effects of Telework: A Quasi-Field Experiment.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 29 (6): 795–808. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2020.1774557.

- Dingel, J. I., and B. Neiman. 2020. “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” Journal of Public Economics 189: 104235. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235.

- Dizaho, E. K., Salleh, R. and Abdullah, A. 2017. “Achieveing Work Life Balance Through Flexible Work Schedules and Arrangements.” Global Business & Management Research 9 (1s): 455–465.

- Dutcher, E. G. 2012. “The Effects of Telecommuting on Productivity: An Experimental Examination. The Role of Dull and Creative Tasks.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 84 (1): 355–363. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2012.04.009.

- Eddleston, K. A., and J. Mulki. 2017. “Toward Understanding Remote Workers’ Management of Work–Family Boundaries: The Complexity of Workplace Embeddedness.” Group & Organization Management 42 (3): 346–387. doi:10.1177/1059601115619548.

- FastLane 2020. “Infographic: Work From Home Hong Kong Survey COVID-19.” Accessed 29 April. https://fastlanepro.hk/work-from-home-hong-kong-infographic/

- Gajendran, R. S., and D. A. Harrison. 2007. “The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 92 (6): 1524–1541. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524.

- Gerards, R., A. de Grip, and C. Baudewijns. 2018. “Do New Ways of Working Increase Work Engagement?” Personnel Review 47 (2): 517–534. doi:10.1108/PR-02-2017-0050.

- Gorlick, A. 2020. “The Productivity Pitfalls of Working from Home in the Age of COVID-19.” Stanford News. Accessed 17 June 2020. https://news.stanford.edu/2020/03/30/productivity-pitfalls-working-home-age-covid-19/

- Grant, C., Wallace, L., & Spurgeon, P. (2013). An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker's job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Employee Relations, 35, 527–546. doi:10.1108/ER-08-2012-0059

- Grant, C. A., L. M. Wallace, P. C. Spurgeon, C. Tramontano, and M. Charalampous. 2019. “Construction and Initial Validation of the e-Work Life Scale to Measure Remote e-Working.” Employee Relations 41 (1): 16–33. doi:10.1108/ER-09-2017-0229.

- Gregory, A., and S. Milner. 2009. “Editorial: Work-Life Balance: A Matter of Choice?” Gender, Work & Organization 16 (1): 1–13. http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/1737/. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00429.x.

- Hartley, K., and D. S. L. Jarvis. 2020. “Policymaking in a Low-Trust State: legitimacy, State Capacity, and Responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong.” Policy and Society 39 (3): 403–423. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791.

- HM Government. 2020. “Working Safely During COVID-19 in Offices and Contact Centres.” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5eb97e7686650c278d4496ea/working-safely-during-covid-19-offices-contact-centres-041120.pdf

- Hong Kong Economic Times Limited. 2020. 【肺炎疫情】鍾南山列3大傳染高危場所 排第一是電梯(更新版). Accessed 3 April 2020. https://bit.ly/3gjMjbZ

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (HKPORI). 2020a. “On the whole, do you trust the HKSAR Government?” (Per Poll). Accessed 20 March 2020. https://www.pori.hk/pop-poll/hksarg/k001

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute 2020b. 新冠肺炎對工作影響意見調查. Accessed 21 May 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cfd1ba6a7117c000170d7aa/t/5ec5fdb28e5b9f5b9fad0447/1590033846783/GM_Covid19_presentation+by+pori.pdf

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020a. “Special Work Arrangement for Government Employees.” Accessed 19 July 2020. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202007/19/P2020071900482.htm

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020b. “Health Declaration Applies to XRL.” Accessed 23 January 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2020/01/20200123/20200123_203125_697.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020c. “Special Work Arrangement for Government Departments.” Accessed 28 January 2020. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202001/28/P2020012800310.htm

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020d. “Further Measures to Fight Virus.” Accessed 28 January 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2020/01/20200128/20200128_182923_787.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020e. 公務員下周首階段回復正常上班. Accessed 28 April 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/chi/2020/04/20200428/20200428_103401_785.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020f. “Govt Work Arrangement Announced.” Accessed 19 July 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/chi/2020/07/20200719/20200719_172804_522.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020g. “Public Services to be Adjusted.” Accessed 21 March 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2020/03/20200321/20200321_195107_148.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020h. 公務員不適合一刀切在家工作. Accessed 13 July 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/chi/2020/07/20200713/20200713_211603_613.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020i. “Resuming Public Services Backed.” Accessed 2 March 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/chi/2020/03/20200302/20200302_142856_640.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020j. “LCQ2: Information technology Support for Government Personnel Working from Home.” Accessed 13 May 2020. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202005/13/P2020051300327.htm

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020k. “Special Work Arrangement for Government Employees to be Extended.” Press Releases - HKSAR Government. Accessed 6 August 2020. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202008/06/P2020080600379.htm?fontSize=1

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020l. “Public Services to Resume.” Hong Kong’s Information Services Department. Accessed 20 August 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2020/08/20200820/20200820_182511_834.html?type=category&name=covid19&tl=t

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020m. “CSB Reminds Departments to Handle Work Arrangements for Employees With Flexibility.” Press Releases - HKSAR Government. Accessed 20 November 2020. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202011/20/P2020112000698.htm?fontSize=1

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2020n. “Special Work Arrangements for Government Employees.” Press Releases - HKSAR Government. Accessed 30 November 2020. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202011/30/P2020113000552.htm

- Hong Kongers Prefer Working in the Office | Randstad Hong Kong. Randstad Hong Kong, Limited. Accessed 15 November 2020, from Randstad Hong Kong. n.d. https://www.randstad.com.hk/about-us/news/working-at-the-office-a-popular-concept-among-hongkongers-randstad-workmonitor-research/.

- JLL 2020. “Home and Away: The new workplace hybrid?” Accessed July 2020. https://www.jll.com.hk/content/dam/jll-com/documents/pdf/research/apac/ap/jll-research-home-and-away-jul-2020-latest.pdf

- Kalliath, T., and P. Brough. 2008. “Work-Life Balance: A Review of the Meaning of the Balance Construct.” Journal of Management & Organization 14 (3): 323–327. doi:10.5172/jmo.837.14.3.323.

- Kazekami, S. 2020. “Mechanisms to Improve Labor Productivity by Performing Telework.” Telecommunications Policy 44 (2): 101868. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101868.

- Marlow, I. 2020. “Hong Kong Shutdown a Lesson to the World in Halting Virus.” Accessed 16 March 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-16/hong-kong-shutdown-is-a-lesson-to-the-world-in-halting-the-virus

- Mello, J. A. 2007. “Managing Telework Programs Effectively.” Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 19 (4): 247–261. doi:10.1007/s10672-007-9051-1.

- Messenger, J. C., and L. Gschwind. 2016. “Three Generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (r)Evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office.” New Technology, Work and Employment 31 (3): 195–208. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12073.

- Ng, K. C. 2020a. “Do Hong Kong’s Work-From-Home Employees Get a Day Off When Typhoon Signal No 8 Is in Force?” Accessed 18 August 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/30,97,872/hong-kong-braces-higos-will-teleworkers-still-have-work-when

- Ng, K. C. 2020b. “Coronavirus: 87 Per cent of Hong Kong Employees Suffering Work Stress During Covid-19 Pandemic, Survey Finds.” Accessed August 2 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/30,95,716/coronavirus-87-cent-hong-kong-employees-suffering

- Ng, N. 2018. “Hong Kong’s Small Flats ‘To Get Even Smaller’, Hitting Quality of Life.” Accessed 24 November 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/economy/article/21,42,165/hong-kongs-small-flats-get-even-smaller-hitting-quality-life

- Nilles, J. M. 1988. “Traffic Reduction by Telecommuting: A Status Review and Selected Bibliography.” Transportation Research Part A: General 22 (4): 301–317. doi:10.1016/0191-2607(88)90008-8.

- Noda, H. 2020. “Work–Life Balance and Life Satisfaction in OECD Countries: A Cross-Sectional Analysis.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (4): 1325–1348. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00131-9.

- Now News. 2020a. 調查:近七成受訪社福員工不滿機構防疫措施. Accessed 5 March 2020. https://news.now.com/home/local/player?newsId=3,83,093

- Now News. 2020b.賽馬會:必要人員外員工下周一起在家工作. Accessed 20 March 2020. https://news.now.com/home/local/player?newsId=3,85,104

- Pao, Ming. 2020. 陳肇始籲僱主推在家工作 公務員局大學發指引 - 2,02,01,125 - 要聞. 明報新聞網 - 每日明報 Daily News, November 25. https://bit.ly/33GGZKL

- Planning Department. 2002. “Working Paper No. 23 Study of the Impacts of Information Technology on Planning.” July 2020. https://www.pland.gov.hk/pland_en/p_study/comp_s/hk2030/eng/wpapers/pdf/workingPaper_23.pdf

- Purwanto, A., M. Asbari, M. Fahlevi, A. Mufid, E. Agistiawati, Y. Cahyono, and P. Suryani. 2020. “Impact of Work from Home (WFH) on Indonesian Teachers’ Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 29 (5): 6235–6244.

- Robertson, M. M., W. S. Maynard, and J. R. McDevitt. 2003. “Telecommuting: Managing the Safety of Workers in Home Office Environments.” Professional Safety 48 (4): 30–36.

- RTHK 2020a. “Govt Reverses Daytime Ban at Restaurants.” Accessed 30 Jul 2020. https://news.rthk.hk/rthk/en/component/k2/1540748-20200730.htm

- RTHK 2020b. “Government Workers Can Work from Home: Govt.” Accessed 28 Jan 2020. https://news.rthk.hk/rthk/en/component/k2/1505218-20200128.htm

- Saiidi, U. 2020. “How Hong Kong Beat Coronavirus and Avoided Lockdown.” Accessed 2 July 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/03/how-hong-kong-beat-coronavirus-and-avoided-lockdown.html

- Sardeshmukh, S. R., D. Sharma, and T. D. Golden. 2012. “Impact of Telework on Exhaustion and Job Engagement: A Job Demands and Job Resources Model.” New Technology, Work and Employment 27 (3): 193–207. doi:10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x.

- Shaw, S. M., J. Andrey, and L. C. Johnson. 2003. “The Struggle for Life Balance: work, Family, and Leisure in the Lives of Women Teleworkers.” World Leisure Journal 45 (4): 15–29. doi:10.1080/04419057.2003.9674333.

- Smith, S. A., A. Patmos, and M. J. Pitts. 2018. “Communication and Teleworking: A Study of Communication Channel Satisfaction, Personality, and Job Satisfaction for Teleworking Employees.” International Journal of Business Communication 55 (1): 44–68. doi:10.1177/2329488415589101.

- Solís, M. S. (2016). Telework: conditions that have a positive and negative impact on the work-family conflict. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 29(4), 435–449.

- Sun Life 2020. Accessed 20 May. Health Conscious Office Workers Appreciate Benefits of Working from Home. Retrieved from https://www.sunlife.com.hk/en/about-us/newsroom/news-releases/2020/health-conscious-office-workers/

- Tam, L. 2020. Accessed 17 August. Mental health and working from home: what companies can do to help staff amid prolonged Covid-19 disruption. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/health-wellness/article/30,97,606/mental-health-and-working-home-what-companies-can-do-help

- Task Force on Land Supply 2018. “Land for Hong Kong: Our Home, Our Say! (Rep.).” Accessed 30 Nov 2020. https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr17-18/english/panels/dev/papers/dev20180529-booklet201804-e.pdf

- Teo, J. 2020. “More Working from Home Feel Stressed Than Those on Covid-19 Front Line: Survey.” Accessed 19 Aug 2020. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/more-work-from-homers-feel-stressed-than-front-line-workers-singapore-survey-on

- The World Bank Group. 2020. “Individuals Using the Internet (% of population) - Hong Kong SAR, China, Bahrain | Data.” Accessed 24 Nov 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=HK-BH&most_recent_value_desc=true

- Times of India. 2020. “Work from Home is Making 67% Indians Suffer from Sleep Deprivation, Says Study.” Accessed 14 April 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/relationships/work/work-from-home-is-making-67-indian-suffer-from-sleep-deprivation-says-study/articleshow/75126242.cms

- Ting, V., E. Cheung, and L. Cheng. 2020. “Hong Kong Third Wave: Government Tightens Preventive Measures as Number of Covid-19 Cases Hits Record High of 113.” Accessed 22 July 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3094186/hong-kong-third-wave-covid-19-cases-top-previous

- Troup, C., and J. Rose. 2012. “Working from Home: Do Formal or Informal Telework Arrangements Provide Better Work–Family Outcomes?” Community Work & Family 15 (4): 471–486. doi:10.1080/13668803.2012.724220.

- Tsang, D. 2020. “Coronavirus: Working from Home a New, Occasionally Frustrating, Experience for Hongkongers Used to Rhythms of Office Life.” Accessed 2 Feb 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-economy/article/30,48,557/coronavirus-working-home-novel-occasionally

- Virick, M., N. DaSilva, and K. Arrington. 2010. “Moderators of the Curvilinear Relation between Extent of Telecommuting and Job and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Performance Outcome Orientation and Worker Type.” Human Relations 63 (1): 137–154. doi:10.1177/0018726709349198.

- Wan, K.-M., L. K.-K. Ho, N. W. M. Wong, and A. Chiu. 2020. “Fighting COVID-19 in Hong Kong: The Effects of Community and Social Mobilization.” World Development 134: 105055. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105055.

- Wong, H. K. A., and J. Cheung. 2020. “Survey Findings on Working from Home Under COVID19.” Lingnan University. Accessed 20 May 2020. https://www.ln.edu.hk/f/upload/48,728/Survey%20findings%20on%20Work%20From%20Home_Eng.pdf

- World Health Organisation 2020. “COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global Research and Innovation Forum.” Accessed 12 Feb 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum

- World Health Organization 2020. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 202.” Accessed 9 Aug 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/2,02,00,809-covid-19-sitrep-202.pdf?sfvrsn=2c7459f6_2