Abstract

Overcoming pandemics call for immediate and dedicated public health policy solutions. This study analyzes the public health policies introduced in the province of Ontario in Canada, and the country of Scotland in the United Kingdom, in a bid to address the COVID-19 pandemic. We focus on regional policy design by the key health policy decision makers and examine the influence of gender in the solutions introduced by these policy leaders. Drawing from the concept of feminist sociological institutionalism, we argue that that the solutions directed at curbing COVID-19, which was led by a female health minister in Ontario, and a female health secretary in Scotland, did not conform to gendered expectations. While the gendering of institutions is often streamlined to achieve gender equality and consider female issues, the study shows that undivided attention was dedicated to curbing COVID-19, without opportunistic interference and taking advantage of a political window.

1. Introduction

The debilitating effects of COVID-19 pandemic spurred many leaders across the world to swiftly initiate policy measures to contain the spread of the virus. Commentators from mainstream media, social media, and academia have observed the outstanding performances of female political leaders in managing the effects of the pandemic. In this article, we address the question–did female policy leaders at the regional level conform to gendered expectations in developing policy solutions for combatting the COVID-19 pandemic? And if not, why? By gendered expectations, we refer to the notions that women prioritize interactions over agency and decisiveness (Bruckmüller and Branscombe Citation2010; Larsson and Alvinius Citation2020) and seek to legitimize their political power by feminizing public policy (Bashevkin, Citation2009; D’Amico Citation2010). With the conceptual framework of feminist institutionalism, our study investigates the cases of female leadership in Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom, and the regional policy response to the pandemic. We examine whether gender was a primary component of the key policies introduced in the time of the pandemic by the health minister of Ontario province, and by the health secretary in the country of Scotland, as the leaders grappled to make sense of the nature, extent, and effects of COVID-19 pandemic. We also argue that institutional changes, which advance gender equality and female leadership, empower female policy leaders to perform their assignments without prevarication.

The next section presents the conceptual framework, feminist institutionalism, and the literature on gender and COVID-19. This is followed by the methodology employed for the research. Afterwards, we relay accounts of how the women health policy leaders addressed COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario and Scotland. The section after this presents an analysis of the case studies and we argue that the leaders focused the public health policies on COVID-19, and did not take advantage of the pandemic to divert attention to women’s issues unrelated to their health policy portfolio. We explain that the reason for this is because their political institutions have existing provisions for addressing women’s issues and also, the institutional changes at the macro and micro level have enabled the leaders to focus policies on the key health concerns. The last section concludes the paper and maintains that policy design by female leaders in the time of uncertainty will not necessarily focus on gender considerations nor rely on it for legitimacy.

2. Literature background

2.1. A feminist sociological institutionalist approach

We adopt a feminist institutionalism approach for analyzing the factor of gender in policymaking for combating the coronavirus pandemic. In particular, we draw from the feminist perspective of sociological institutionalism. A feminist sociological institutional perspective offers a viewpoint that allows the analysis of how gender shapes institutions and how institutions have impacted and changed gender norms (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Citation2010). Sociological Institutionalism (SI) argues that institutions are essential because they are not only made up of formal rules and practices but also “embedded with symbol systems, cognitive scripts and moral templates” that shape the behavior of their members (ibid). Political actors are therefore not just rational beings, but social actors that exist within institutional contexts, conforming to the logic of appropriateness in their actions (Hall and Taylor, Citation1996; Minto and Mergaert Citation2018). The presence of gender lens in this perspective allows the framing of the formal advancements made in gender issues in Western nations. This is because the constitutive gender equality norm of liberal societal contexts has informed the removal of many sexist institutional barriers and increased the presence of women bodies in positions of power over time. Historical records show that there is an increase of female presence in leadership (Hoogensen and Solheim Citation2006; Runyan Citation2019). This argument, however, does not presuppose an end of gender disparity or inequality even in the most liberal nations as women still grapple with persistent gender pay gaps and covert sexism (Auspurg, Hinz, and Sauer Citation2017; Lips Citation2013; Jeffreys Citation2014).

A feminist SI perspective enables the exploration of the macro and micro levels of change from conformity with traditional institutional gender norms and practices (DiMaggio and Powel, Citation1991), so that one can interrogate the level and extent of the impact of gender integration processes. Changes at the macro levels are often readily and directly associated with formal rules (Bjarnegård and Kenny Citation2016; Evans and Kenny Citation2020), whereas the gendered perceptions of individuals at the micro level, go a long way to influence “how things are done” within the institution (Lowndes, Citation2014, 685). Therefore, micro perspectives, even if they go unnoticed for a while, have gendered consequences (Bjarnegård and Kenny Citation2016). More importantly, SI considers institutions from the context of macro and micro level linkages (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Citation2010). Institutional effects are not presented or examined through the isolation of rules, norms, and values at the macro level, nor through the isolation of the conduct of individuals at the micro level. A feminist SI approach emphasizes the “distinctive … relationship between institutions and individual action,” which is buffered by “formal and informal collections of interrelated norms, rules, and routines, understandings and … acceptable behavior of members” (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Citation2010, 255). As such, bridging the macro and micro levels aids the understanding of institutions and identification of shortcomings in institutional change.

For example, institutional gender culture has evolved and enabled women to embrace opportunities and make inroads into positions of leadership and power, as evident in the two case studies; Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom, yet, from a micro perspective, gendered perceptions sometimes continue to inform the explorations of leadership capabilities. This points to the feedback loop associated with the link between practices at the micro level and formal rules introduced at the macro level. According to Evans and Kenny (Citation2020), individual action which are in line with formal rules, can reinforce institutional changes at the macro level. This shows that the impact of formal rules that are initiated to change gender perceptions and attain gender equality, is dependent on changes to individual practices at the micro-level. In similar vein, the likelihood of changes to gender perspective at the micro-level is dependent on the introduction of formal rules at the macro-level. Based on this, the experience of female leaders will likely be defined by the intersection of changes in the formal rules at the macro-level and micro-level perspectives.

In a time of crisis, people experience events amidst uncertainties, and they become expectant and anxious for the leaders to take urgent action (Boin Citation2019; Boin and ‘t Hart Citation2007). While the responsibility to take urgent action rests squarely on the leader, the individual will mostly act within the ambit of institutional rules, as discussed above. Institutional rules constrain actors in their understanding and compliance with what is appropriate or inappropriate (Evans and Kenny Citation2020). According to Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell (Citation2010), “institutions and individual action are … mutually constitutive” (256), so that institutions can also be shaped by the individuals and groups who embody and enact the institutional norms. Consequently, a leader’s action in a time of crisis, is conditioned by the institution, while the institution is also being shaped by the collection of individual dispositions. Thus, the consideration of the interaction of the institutional norms, values, and rules at the macro level, and individual action at the micro level, is essential to examining the action of leaders in crisis situations.

2.2. COVID-19 and female leadership

In many articles relating to COVID-19 and gender, the analytical lens turns to the impact of the pandemic on women. The emaciation of reproductive health services, escalation of domestic violence, and a heightened triple burden consisting of official work demands, household work demands, and community volunteering demands, are some of the impacts that are highlighted when considering the COVID-19 pandemic from a gender perspective (Gausman and Langer Citation2020; UNDP Citation2020). Women often bear the brunt of unabated economic inequality. In the advent of a pandemic, the unequal access to financial resources limits their choices for seeking protection from microbes that pose a danger to their health, and from acquaintances that may pose a danger to their emotional and/or physical health (Branicki Citation2020; Gausman and Langer Citation2020; Murkherjee Citation2007). In the past “women of childbearing age and pregnant women suffered some of the worst effects from the (influenza) pandemic with approximately one third becoming infected” (Almond, 2006 cited in Garthwaite Citation2008). While scientific and technological advancements limit the rate of deadly infection, in present times, pandemics can exacerbate existing economic inequality and perpetuate negative health conditions and outcomes for women (Kristal and Yaish Citation2020; Kate Power Citation2020). Findings on how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting women show that more women have lost their income or earned less as a result of COVID-19 (Kristal and Yaish Citation2020). Also, women are sleeping less and the burden to care for family members is worsening their mental health. These concerns are deserving of utmost attention from political leaders, as they point to the malaise resulting from the pandemic based on gender. However, in addition to these impacts, it is important to consider the place, roles, and opportunities for female leadership in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What does it mean to be a female leader in the time of a pandemic? Coscieme et al. (Citation2020) reports on a comparative study of how the leaders of 35 countries fared in their response to the pandemic. The study differentiated the countries by the gender of the leaders and assessed certain indices including, the number of deaths that occurred in the countries due to COVID-19, the number of days from first reported death, peaks in daily deaths, and number of deaths per capita. The findings show that COVID-19 fatality was demonstrably lower and occurred for a shorter period in countries led by women than in countries led by men. The authors conclude that the observed differences can be attributed to the policy goal of social wellbeing adopted by most female leaders, but often eschewed by male leaders, whose preference lingered on economic growth.

An explanation of leadership performance, which is steeped in gender difference, is not new. There are earlier studies that examine why women rise to positions of power in the time of crisis and how they fare during the crisis (Bruckmüller et al. Citation2014; Ryan et al. Citation2016; Sergent and Stajkovic Citation2020) Many of these studies stress the perception of differences in leadership styles of women and men. While men are perceived to be assertive, risk takers, decisive, and competitive, women are seen to be caring, convivial, and collaborative. Another aspect to this line of research is the glass cliff phenomenon, whereby the appointment of women as leaders in times of crisis can result in leadership failure and likely jeopardizing future leadership opportunities (Bruckmüller et al. Citation2014). The female leaders in our study were in their position of power before the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, and contrary to the effect of the glass cliff, they are highly lauded for their performance in managing the pandemic. Female leadership qualities have been extolled in several academic and media news outlets (Huang Citation2020; Chamorro-Premuzic and Wittenberg-Cox Citation2020; Fioramonti, Coscieme, and Trebeck Citation2020; Marks Citation2020; Taub Citation2020), and naturally, the achievements of the female leaders have been mostly summarized to be as a result of their gender. This is a limitation in the literature. By narrowing the explanation of female leadership performance to gender, the factors influencing or enabling female leadership performance are often disregarded. This study addresses the gap in the literature, and we consider institutional changes as a reason for the focused performance of female leaders in addressing the challenge of COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methodology

To carry out the research, we employed a comparative case study approach. The selection of the cases is informed by the gender similarity associated with the elected member of the regional parliament in charge of the health portfolio, and the similarities in the health system in Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom, as shown in . Additionally, we considered the similarities in the policies introduced by the health ministers to manage public health in their respective regions, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across countries and continents, and leaving in its paths, lost lives and lost livelihoods. These similar cases are aimed to be informative (Swanborn Citation2010). They are employed to demonstrate how female political leaders adhere to their assigned portfolio and abstain from deferring to gender issues in seeking legitimacy for their decisions, because of institutional influence on female leadership. A possible shortcoming of the use of most similar cases is the lack of opportunity for examining instances where female leaders have relied on their gender and leaned toward gender issues in a bid to enforce COVID-19 pandemic restrictions within their jurisdiction. However, since the COVID-19 and female leadership is an emerging area of inquiry, it is better to proceed with a small number of cases and to focus on specific observations that minimize variations between cases (Gerring Citation2017; Swanborn Citation2010).

Table 1. Health System and Health-Related Information for Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom.

The two cases were analyzed through document analysis. We identified specific documents that were released by the offices of the health minister in Ontario, and health secretary in Scotland, on the official website of the Government of Ontario and the Scottish Government, respectively. The selection of documents from government sources helps to ensure the use of reliable sources. The documents selected were based on the date of authorship, and we focused on the documents that were produced between the day of the first public announcement on action taken to address the pandemic and the declaration of lockdowns. We focused on this period primarily because in the literature, it is seen as critical in determining the fatality of the pandemic and how long it would take the community to recover from the effects of the pandemic. Another reason is because after the declaration of lockdown, overall management of the pandemic shifted to the ambit of the heads of the regional governments. As such, decisions taken after the lockdown can be deferred more to the Premier Doug and the First Minister Nicolas Sturgeon in Ontario and Scotland, respectively. In the case of Ontario, we identified and downloaded 18 official statements and press releases from the Ontario government’s website. With regards to Scotland, we used 16 documents published by the UK and Scottish government on their official actions in response to the challenge of the pandemic. The documents were analyzed based on the consideration of whether female leaders took proactive decisions and if they sought to legitimize their political power by feminizing public policy. As such, we identified the health policy decisions in the documents issued by the female leaders. The targets for the policies were also identified from the documents, to show whether the policies were only targeted at women, or if they addressed the public health of the general population, in line with their assigned portfolio and the task of overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic.

We are aware that this study is at the sub-national level and thus, has limitations on how far we can attribute an action or policy to the portfolio minister. We have therefore highlighted specific actions that were implemented at these sub-national levels. Also, we know that limiting the period of analysis to the day of lockdown will not show whether there were references to gender issues later on. However, focusing on the period between when COVID-19 was first given policy attention and the day that local lockdown became effective, shows a time when their personal leadership qualities are mostly exhibited, because uncertainties are high and the leaders are placed in the heat of making decisions on how to fight against the pandemic.

4. Case studies

4.1. Ontario, Canada

The first presumptive case of COVID-19 in the province of Ontario was announced in January 2020. Ontario is led by a provincial government that holds the authority to make policies and laws for managing the health of Canadian citizens and residents living within the province of Ontario. The health minister in Ontario is Honorable Christine Elliot. She also supports the Premier of the province, Honorable Doug Ford, as the Deputy Premier.

Whilst there was yet any record of COVID-19 infection in Ontario, the Minister issued a formal announcement on the coordinating efforts to be engaged by the federal and provincial governments in monitoring the risks of COVID-19 infection. When multiple presumptive cases began to emerge in the province in early February, the office of the Health Minister set out to arrange regular briefings with journalists in a bid to keep residents up to date on the state of the infected persons, concerns of community transmission, as well as to notify the general public on the measures being undertaken by the regional government. At this time, the public messaging on COVID-19 reiterated that “the risk to Ontarians remains low” (Queen’s Printer for Ontario Citation2020a, 1). This message sought to calm residents and allow businesses and individuals, go about their regular routines. By February 26, there was beginning to be a sense of certainty in the occurrence of COVID-19 in Ontario, as a definite positive case of COVID-19 had been reported. In the next eight days, the number of confirmed cases increased by more than 600%. As an immediate response to this occurrence, the Minister unveiled specific enhanced measures that established new coordinating units that will pull together essential expertise across the health sector. The measures also prioritized preparedness and prompt response across all cadres of health management units in the province. This new coordinated response put in place a Command Table to lead Ontario’s response to COVID-19, five regional planning and implementation tables to implement provincial strategies with the support of local health units, a specific Ministry’s Emergency Operations Center, a Scientific Table for provision of scientific and technical guidance, a dedicated Ethics Table for ethical guidance, a focused Sector/Issues Specific Tables for addressing particular and evolving concerns, and distinct Collaboration Tables. The enhanced response shows the reporting structure for the regional health units under the management of the health ministers. It also highlights the networking structure for the Ministry of health, health-related institutions, and affiliate sectors.

Following the establishment of a reporting structure, the Minister proceeded to prevent the flow of infected persons or items into Ontario. The policy solution extended by the Minister of Health and her counterpart, the Minister of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries, Honorable Lisa MacLeod, was aimed at switching sources of tourism business into the province, as the official tourism agency was advised to direct its marketing at other Canadian provinces and countries without high records of COVID-19 cases. In addition, a dedicated website went live, where up-to-date information on the status of the province could be accessed by any member of the public. The Ministry of Health also continued hosting regular media briefings with the Chief Medical Officer, Dr David Williams, and the Associate Chief Medical officer, Dr. Barbara Yaffe, fielding questions from journalists. The public messaging at this point centered on taking precautionary measures, particularly handwashing.

On March 12, 2020 all publicly funded primary and secondary schools were ordered to close. With this essential drastic measure, the curtain was drawn on the preceding precautionary measures and giving assurances of a low risk of exposure to the novel coronavirus in Ontario. Already, some European countries were witnessing a very sharp increase in the infection and mortality rates and this informed the Minister to mute the initial perception on the level of risk. Chiefly, the policy direction changed significantly after the Canadian Prime Minister’s wife, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau contracted the coronavirus while on an official trip to the United Kingdom (BBC Citation2020). This incident, along with the escalating spread of COVID-19 infection internationally and locally showed that the province was heading for a difficult time. The Ministry set all guns blazing without holding back and promptly announced all the necessary measures for the onset of the “alternate normal” much needed to combat the coronavirus. On March 16, 2020 in line with the advice of the Chief Medical Officer, any gathering of more than 50 people was to be avoided across Ontario. Also, all recreational programs and libraries, all private schools, all daycares, all churches and other faith settings closed their doors. Non-essential visits to all long-time care homes was banned. All bars and restaurants had to shut down services with the exception of food delivery activities.

These decisions were part of an encompassing response to containing the spread of the virus and protecting the health of Ontarians. Another crucial public policy put in place was the extension of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) to persons waiting to qualify for the program and those who would never have met requirements for qualification. The policy gave vital assurance to the public that they would be taken care of at limited or no cost to them or their family, if they fall sick. This ensured that persons with the virus were willing to go to clinics and be taken out of the community, thereby reducing the transmission of COVID-19 in communities across Ontario. There was also a timely response to unfolding events as the spread of the virus evolved into a pandemic, and this highlights how the province was prepared and highly responsive in taking on the first wave of COVID-19 infection. In the words of Honorable Christine Elliott, "[t]he health and well-being of Ontarians … was (the) government’s number one priority" (Queen’s Printer for Ontario Citation2020b).

4.2. Scotland, United Kingdom

The Scottish government, as a devolved administration, is responsible for the issues of health, among others, to the Scottish people. So, with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite overarching policies that were made by the United Kingdom government, it had its team of experts that oversaw policy decisions and steered, and continues to steer, Scotland through the pandemic. This team is headed by the women in positions of the First Minister, Chief Medical Officer (until her resignation in April 2020), Deputy Chief Medical officer and Health Secretary. This is not to discount the fact that the Scottish Government COVID-19 Advisory group responsible for analyzing and interpreting the scientific and technical aspects and processes necessary for understanding the pandemic and advising the government and the people of Scotland, is headed by a man and has more male members than female members. Nonetheless, female leaders are at the helm of affairs and have depicted the insignificance of gender as a factor in leadership capabilities.

Scotland recorded its first positive case of the COVID-19 virus on the 1st of March 2020, after the first British death from the virus was reported on the 28th of February (The Scottish Governmen). By the 3rd of March, the governments of the United Kingdom, including Scotland, published an action plan for tackling the virus which outlined a collective approach to the epidemic. The plan focused on an initial aim of containing the spread of the virus and a subsequent stage by stage response to the situation depending on how the spread of the virus evolved (The Department of Health and Social Care Citation2020). Advice from the scientific experts encouraged efforts toward delaying the peak of the outbreak for as long as possible to avoid this overlapping with the seasonal flu and overwhelming the National Health Service (NHS). Consequently, the governments’ campaign involved advice on the 20-second hand washing, discouragement of unnecessary travel which also meant working from home as much as possible, and social distancing (ibid). The principal goal was captured in the phrase "protect the NHS, save lives." The eventual total lockdown measures for the country was announced on the 23rd of March.

Within the context of these countrywide measures by the government of the UK, Scotland, under the leadership of its First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, the Health Secretary, Jeane Freeman and Chief Medical Officer, Catherine Calderwood, adopted its specific internal policies that reinforced the efforts against the pandemic. These efforts have resulted in more success in containing the virus and reducing the infection and COVID-19 related death rate in Scotland. For one, Scotland quickly launched a method of community testing in February when there was a realization that infection by the virus was spreading and set up the world’s first drive-through testing center (Mark et al. Citation2020). Although this was seen as one of the early factors of success in Scotland’s battle to contain the virus, community testing was abandoned by the UK government, including Scotland, by the middle of March to concentrate on testing in hospital and other Healthcare settings (Marshall Citation2020). This was due to a lack of resources to keep up despite the cost-effectiveness and other benefits of the method. Also, while the UK government announced lockdown measures on the 23rd of May, Scotland went into full lockdown from the same day. Some experts have argued that this early lockdown is responsible for Scotland’s lower death rate compared to the rest parts of the UK. (McArdle, Citation2020). In fact, as of April, the rate of the spread of the virus in Scotland was believed to be six to seven days behind London (ibid).

Furthermore, the creation of the COVID-19 scientific advisory group by the First Minister to supplement advice coming from the national government further display the dynamic leadership in Scotland during the pandemic. This gave Scotland an additional source of scientific knowledge and reinforced its moves in tackling the pandemic. The successful development of its “Test and Protect” system which is a “test, trace, isolate and support” structure, different from England’s “Test and Trace” app is an additional factor in Scotland’s successful efforts against the COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas England’s “Test and Trace” app delayed in taking off and has been argued as not particularly successful, the “Test and Protect” system is based on old fashioned, traditional, evidence-based contact tracing which experts have agreed is significant in containing the spread of the virus (Keeling et al, Citation2020). Primarily, the Scottish system involved “testing symptomatic people, tracing contacts, isolating those who are carrying or have been exposed to the virus, and providing them with the necessary support to meet their needs” (Sridhar and Chen Citation2020) ().

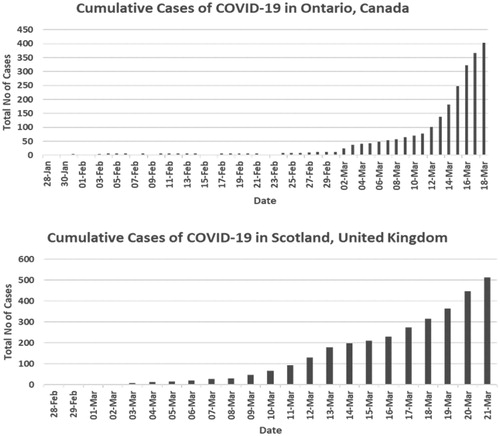

Figure 1. COVID-19 Cases in Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom. Source: Queen’s Printer for Ontario Citation2020a; The Scottish Government 2020.

5. Discussion

“Public sector workers are now more likely to be operating in environments where women are present and where gender issues have become institutionalized” (Schofield and Goodwin Citation2005, 1). The same is true for the Ontario government and the Scottish government. Honorable Christine Elliott is one of ninety-eight female members of the Ontario provincial parliament, and altogether they constitute about 40% of the members of provincial parliament (MPPs). With her cabinet ministerial appointments as the Deputy Premier and Minister of Health, she is one of seven female cabinet ministers in Ontario. Far from the “stifling decade of the ‘50 s’” (Ontario Federation of Labour Citation2007, 33), when women were forced to resign from their jobs once they got married (Findlay Citation2015), the government and political parties in Ontario have in recent times, introduced distinct measures that support women and promote women participation in politics and leading public policy.

5.1. Macro-level changes and gender effects

In 2018, the province of Ontario recorded the highest number of female MPPs across Canada. There is a consensus in the literature of how active state feminism in Ontario’s government has informed many desirable changes toward institutionalizing feminism (Briggs Citation2001; Findlay Citation2015; Collier Citation2017). The Ontario government is sometimes regarded as a sterling example of a gendered institution, as the region’s gender pay equity legislation is acclaimed to be one of the best in the world (Gunderson Citation2002; Rubery and Koukiadaki Citation2018). Similar to Ontario, the devolved government of Scotland has also made significant strides in the institutionalization of gender equality policies. A “new kind” of women politics emerged in 1997, which placed equal participation and women’s inclusion at the top of the agenda (Stirbu Citation2011, 32). The major political parties adopted measures that delivered vast opportunities and visibility for women, including a “twinning” process ensuring equal numbers of men and women are selected across constituencies, enforcing gender quota measures, and other informal methods of ensuring fielding women for political election (Kenny Citation2011; Thiec Citation2010). These measures resulted in what has been referred to as a “gender coup,” as women emerged as 50% of elected members from one of the political parties, the Scottish Labor Party, and 42.9% of the Scottish National Party (Kenny Citation2011). Till date, the presence of women in the Scottish parliament has remained above 30% (Stirbu Citation2011) and the Scottish parliament ranks 3rd internationally for women political empowerment (Wilson Citation2018). These progressive measures, along with the steady increase in the adoption of gender policies by the United Kingdom, have enabled the institutionalization of a gender progressive setting where women’s presence in positions of power and leading policy decisions, has become a norm. While the adept performances of the health minister of Scotland, Jeanne Freeman, and Ontario’s health secretary, Christine Elliott may be evidence of the remarkable leadership capabilities of women, they more adequately reflect the extent of institutional changes in gender norms and practices in the respective jurisdictions. The changes in institutional rules, norms, and values have paved the way for women to rise to leadership positions, and also laid the foundation for female leaders to perform leadership roles, not only because they are women, but on the account of their qualifications, experience, and competitiveness. As shown in , the two female leaders have acquired professional experience, political leadership experience, and won regional elections. Being that the institutions already embrace the cause of women’s equality and addresses pertinent female policy issues, the female leaders had been spared the dilemma of representing their appointments and policy decisions, as totems to only female constituents, or for solely advancing feminist agendas despite assuming the office for far-reaching assignments as the policy leaders responsible for protecting the health of the general public. Following this, their decisions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which are highlighted in , did not focus on feminist special interests, or the promotion of a pre-designed policy preference. Instead, they reflect a reliance and emphasis on the assigned portfolio and positioning as the primary leaders of their respective ministry of health. An example of this emphasis can be seen in the statements below, on the focus of the actions led by the health ministers.

Table 2. Profile of Health ministers in Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom.

Table 3. Pre-Lockdown Interventions in Ontario, Canada and Scotland, United Kingdom to Prevent Spread of COVID-19 Infections.

Since we first learned of COVID-19, Ontario has been diligently monitoring the developing situation and taking decisive action to contain the spread of this new virus and ensure the province’s health care system is ready for any scenario. As the situation continues to change, the province is actively working with our partners at all levels in the health care system to implement enhanced measures and update protocols and procedures as necessary (Government of Ontario Citation2020b, 1).

We are expecting an outbreak and are working hard to ensure we have plans in place to contain it as best we can. The NHS and Health Protection Scotland have an established plan to respond to anyone who becomes unwell. Scotland is well-prepared for a significant outbreak of coronavirus. (Scottish Government Citation2020b, 1)

This sense of direction and individuality limits distractions and derailments, and it allows optimal distancing from single issue movements (Chappell Citation2002; Findlay Citation2015; Liu Citation2019). Thus, in handling the problem of COVID-19, the challenge was not approached simply in the context of being female leaders in the time of a pandemic, but as leaders committed to the charge of overcoming the pandemic.

5.2. Micro-Perspectives and gender effects

The literature on COVID-19 and female leadership often places gender at the epicenter of the performance of female world leaders, however, the individual statements and central messaging of the leading women have not always aligned with the claims ascribed to the explanations for the outstanding performance. For example, the Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand has not inferred that her gender is the reason for the impressive pandemic outcome in the country, and neither has Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany. Also, President Tsai Ing-Wen of Taiwan did not refer to her gender in her personal account of how Taiwan surmounted the challenges of COVID-19 (Ing-Wen Citation2020). Many authors hail these national leaders for being female leaders, and rightly so, however, the institutional changes achieved in their jurisdictions should not be neglected. Substantial changes at the macro and micro levels have contributed to extricating overt impediments that would have limited the possibility for celebrating their sterling performances. In Ontario and Scotland, there have been marked changes at the macro level of the institution through rules, norms, and values. Women in politics, and women as policy decision makers are no longer unusual sights, and this reflects the advancement in gender equality.

To a large extent, there are changes at the micro level of the institutions through shifts in the perceptions of individuals and groups. Prejudices about whether a woman qualifies to be at the forefront of a challenge or cause, have been considerably altered, thereby preventing repressions or outright neglect of commands given by the leaders. In Ontario, the creation of the reporting and collaborative structure for reducing morbidity and mortality during the pandemic, remained in place throughout the pre-lockdown period. The structure was not thwarted, and neither was the Honorable Elliott’s proactiveness regarded as unbecoming because of her gender. Instead, the provincial and municipal health officials have worked in line with the instructions they received from the Minister, and this enabled the policies that were introduced, to be implemented as elucidated by the provincial health authority. As noted by Honorable Elliott,

Ontario’s public health system has shown remarkable responsiveness to the … novel coronavirus. That’s in large part thanks to the dedication of the province’s public health officials and everyone working on the front lines of our health care system, all of whom are effectively monitoring for, detecting and containing this virus (Government of Ontario Citation2020c, p. 1)

In Scotland, the commencement of community testing in February 2020 was based on the policy decision made by the health secretary, and undoubtedly, the compliance of Scotland’s street-level officials. The policy was implemented by the officials without recourse to excusing themselves because of the gender of the decision maker. For example, two days after the identification of the first symptomatic case, Honorable Freeman noted that “[f]ollowing confirmation, contact tracing has now been completed by the local health protection team.” (Scottish Government Citation2020c, 1). This relative alignment of “both micro-and macro-level interactions” (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Citation2010, 575) serves as a form of reliable backing that aids the leaders in functioning comfortably and determinedly. Without this reliance, the female leaders might have had to find a foundation or platform from which to elicit legitimacy. This could have meant diverting attention to only women issues, in order to find a voice for providing the needed leadership in the time of a pandemic. However, in the two cases of this study, this was not so, since institutional support at the macro and micro levels provided the anchor from which they could perform their professional roles and be respected for the offices they occupy.

5.3. Coupling the macro and micro level changes

It is arguable that despite the changes on the macro level of institutional gender practices, subtle gender stereotypes persist, not only institutionally, but also independently. Macro and micro level changes need to be coupled for individual performances to be viewed outside of gendered understandings of capability. This would enable the awareness of the agency that the presence of women leaders and their performances in office produce, and how despite this agency, women have not appropriated this at a time of national emergencies, but displayed the capabilities that are not based on categorical attributes, but sound individual competence.

While there is evidence of continued government efforts in addressing gender issues such as the existent gender pay gap, unpaid care work, and gender related domestic violence, in both Scotland and Ontario (Engender Citation2015; Burman and Johnstone Citation2015; Kahan et al. Citation2020), the possibility of substantive progress in achieving gender equality and equity will be limited without the continued alignment of institutional changes at the macro level and changes in the interpretations of the perceived performances of women in executive positions. Nonetheless, we do not discount the increasing visibility of women bodies in positions of power, which attest to the impact of institutionalized changes in gender norms and practices at the micro and macro levels in the two subnational locations. As we can see, the measures introduced by the women health policy leaders to combat the pandemic were targeted at ensuring the safety of the people and seeking to restore the country and province to normalcy. They were not directed at appropriating the agency presented by the situation for tabling a gender agenda. With respect to centralizing the analysis of the performances of female world leaders during the pandemic mostly on gender, this, we argue, leans toward gender essentialism i.e. emphasizing universal innate feminine traits. This approach limits the observation of the individual abilities of the women as competent leaders who are serving to the best of their abilities in a global emergency. The focus should be more on the individual women and their effectiveness, rather than on gender categorization.

6. Conclusion

This research set out to explore whether gender was a key concern of female leaders in their policy decisions for combating the COVID-19 pandemic, and if not, why was this so. Using the province of Ontario and country of Scotland as case studies, we engaged the literature on gender and policy during the pandemic and noted that the literature reflects the analysis of leadership capabilities of female leaders in terms of gendered attributes and how these attributes have influenced their performances. We argued that the tendency to place gender at the center of focus in these analyses may acknowledge the agency produced at this time but tends toward continued gender essentialism which does not acknowledge the individual leadership capabilities of the female leaders. Adopting a feminist sociological institutionalism as the theoretical lens for exploring the cases of Scotland, United Kingdom and Ontario, Canada, the study has shown how significant strides in the institutionalization of norms and values of equality in the form of policies have opened up opportunities for women to occupy positions of power and leadership. The institutionalized changes at the macro level of formal institutions have also produced changes at the micro level, and these changes have made the presence and leadership of women an accepted phenomenon, and not an aberration. This enabled the female leaders to focus on providing leadership that has been evidenced in Ontario and Scotland during the time of national emergency without open resistance from subordinates. They have also not needed to appropriate the agency provided with the pandemic to push gender agendas but focused on providing the leadership needed to help steer their provinces out of the pandemic.

Documenting and reporting on female leadership performance, solely from a gender perspective, may itself be detrimental to the possibility of women attaining senior policy leadership positions. This is because their competence and experience may be overlooked in the consideration of their eligibility for these senior leadership positions. Therefore, the emphasis should be on professional progress. In addition, the finding from this study is an indication that in settings where gender policies have been institutionalized, female policy leaders do not need to hinge their legitimacy on gender in designing policies, but aim to address specific policy problems in line with their assigned policy portfolio. These recommendations corroborate findings in the literature. Studies show that evaluation that is based on gender can reinforce gender stereotypes and limit the rise of female officials to top positions (Bauer Citation2015; Ely and Rhode Citation2010). The latter recommendation is in line with findings in the study of female national leaders (Skyes Citation2013; Trimble Citation2018), which show that limited reliance on gender for eliciting legitimacy, fosters political success. In conclusion, it is necessary to avoid gender categorization of leadership abilities and undermining professional contributions of female policy leaders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1880803)

References

- Auspurg, K., T. Hinz, and C. Sauer. 2017. “Why Should Women Get Less? Evidence on the Gender Pay Gap from Multifactorial Survey Experiments.” American Sociological Review 82 (1): 179–210. doi:10.1177/0003122416683393.

- Bashevkin, S. 2009. Women, Power, Politics: The Hidden Story of Canada's Unfinished Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bauer, N. M. 2015. “Who Stereotypes Female Candidates? Identifying Individual Differences in Feminine Stereotype Reliance.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 3 (1): 94–110. doi:10.1080/21565503.2014.992794.

- BBC. 2020. Canadian PM Trudeau’s Wife Tests Positive for Coronavirus. Accessed 29 July 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-51,860,702.

- Bjarnegård, E.Kenny. and Meryl, M. 2016. “Comparing Candidate Selection: A.” Government and Opposition 51 (3): 370–392. doi:10.1017/gov.2016.4.

- Boin, A. 2019. “The Transboundary Crisis: Why we Are Unprepared for the Road Ahead.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 27 (1): 94–99. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12241.

- Boin, A., and P. ‘t Hart. 2007. “The Crisis Approach.” In: Handbook of Disaster Research. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. New York, NY: Springer.

- Branicki, L. J. 2020. “COVID‐19, Ethics of Care and Feminist Crisis Management.” Gender, Work and Organization 27(5): 872-883. doi:10.1111/gwao.12491.

- Briggs, C. 2001. Fighting for Women’s Equality. The Federal Women’s Bureau, 1945–1967: An Example of Early State Feminism in Canada. PhD Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo.

- Bruckmüller, S., and N. R. Branscombe. 2010. “The Glass Cliff: When and Why Women Are Selected as Leaders in Crisis Contexts.” The British Journal of Social Psychology 49 (Pt 3): 433–451. doi:10.1348/014466609X466594.

- Bruckmüller, S., M. K. Ryan, F. Rink, and S. A. Haslam. 2014. “Beyond the Glass Ceiling: The Glass Cliff and Its Lessons for Organizational Policy.” Social Issues and Policy Review 8 (1): 202–232. doi:10.1111/sipr.12006.

- Burman, M., and J. Johnstone. 2015. “High Hopes? The Gender Equality Duty and Its Impact on Responses to Gender-Based Violence.” Policy & Politics 43 (1): 45–60.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., and A. Wittenberg-Cox. 2020. Will the Pandemic Reshape Notions of Female Leadership? Harvard Business Review, June 26, 2020.

- Chappell, L. 2002. Gendering Government: Feminist Engagement with the State in Australia and Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Collier, C. N. 2017. “A Path Well Travelled or Hope on the Horizon.” In The Politics of Ontario edited by Collier, C.N. and Malloy, J. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Coscieme, L., L. Fioramonti, L. F. Mortensen, K. E. Pickett, I. Kubiszewski, H. Lovins, J. McGlade, et al. 2020. “Women in Power: Female Leadership and Public Health Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” MedRxiv. Accessed July 29, 2020.10.1101/2020.07.13.20152397.

- D’Amico, F. 2010. “Women National Leaders.” In: Politics and Sexuality and Gender. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DiMaggio, P., and W. Powell. 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Elliott and MacLeod. 2020. Statement: Statement from Minister Elliott and Minister MacLeod on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Accessed July 11, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/mtc/en/2020/03/statement-from-minister-elliott-and-minister-macleod-on-the-2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19.html.

- Ely, R. J., and D. L. Rhode. 2010. “Women and Leadership: Defining the Challenges.” In Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice: An HBS Centennial Colloquium, edited by Nohria, N. and Knuran, R. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

- Engender, 2015. A widening gap: women and welfare reform. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.engender.org.uk/content/publications/A-Widening-Gap---Women-and-Welfare-Reform.pdf

- Evans, E., and M. Kenny. 2020. “Doing Politics Differently? Applying a Feminist Institutionalist Lens to the U.K. Women’s Equality Party.” Politics & Gender 16 (1): 26–47. doi:10.1017/S1743923X1900045X.

- Findlay, T. 2015. Femocratic Administration: Gender, Governance, and Democracy in Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Fioramonti, L., L. Coscieme, and K. Trebeck. 2020. Women in Power: It’s a Matter of Life and Death. Social Europe June 1, 2020, Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.socialeurope.eu/women-in-power-its-a-matter-of-life-and-death.

- Garthwaite, D. 2008. The Effect of In-Utero Conditions on Long Term Health: Evidence from the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Accessed November 6, 2020. http://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/garthwaite/htm/fetal_stress_garthwaite_053008.pdf.

- Gausman, J., and A. Langer. 2020. “Sex and Gender Disparities in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Women’s Health 29 (4): 465–466. doi:10.1089/jwh.2020.8472.

- Gerring, J. 2017. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Government of Ontario. 2020a. COVID-19 case data: All Ontario. Accessed November 1, 2020. https://covid-19.ontario.ca/data

- Government of Ontario. 2020b. Statement from Minister Elliott and Minister Romano on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Accessed November 5, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/en/statement/56,303/statement-from-minister-elliott-and-minister-macleod-on-the-2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-1.

- Government of Ontario. 2020c. Ontario’s Public Health System Keeping the Public Safe. Accessed November 4, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/en/statement/55,610/ontarios-public-health-system-keeping-the-public-safe.

- Gunderson, M. 2002. “The Evolution and Mechanics of Pay Equity in Ontario.” Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques 28 (1): 117–131. doi:10.2307/3552165.

- Hall, P. A., and R. C. P. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936–957. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x.

- Hoogensen, G., and B. O. Solheim. 2006. Women in Power: World Leaders since 1960. Colorado: Westview Press.

- Huang, P. H. 2020. Put more women in charge and other leadership lessons from COVID-19. University of Colorado Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 20–21 10.2139/ssrn.3604783.

- Ing-Wen, Tsai. 2020. President of Taiwan: How My Country Prevented a Major Outbreak of COVID-19. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://time.com/collection/finding-hope-coronavirus-pandemic/5,820,596/taiwan-coronavirus-lessons/.

- Jeffreys, S. 2014. Beauty and Misogyny: Harmful Cultural Practices in the West. London: Routledge.

- Kahan, D., D. Lamanna, T. Rajakulendran, A. Noble, and V. Stergiopoulos. 2020. “Implementing a trauma-informed intervention for homeless female survivors of gender-based violence: Lessons learned in a large Canadian urban centre .” Health & Social Care in the Community 28 (3): 823–832. doi:10.1111/hsc.12913.

- Kate Power. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Increased the Care Burden of Women and Families.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 67–73. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561.

- Keeling, M. J., T. D. Hollingsworth, and J. M. Read. 2020. “Efficacy of Contact Tracing for the Containment of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74 (10): 861–866. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214051.

- Kenny, M. 2011. “Gender and Institutions of Political Recruitment: Candidate Selection in Post-Devolution Scotland.” In: Gender, Politics and Institutions, edited by Krook M.L., Mackay F. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kristal, T., and M. Yaish. 2020. “Does the Coronavirus Pandemic Level the Gender Inequality Curve? (It Doesn’t).” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 68: 100520–100525. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100520.

- Larsson, G., and A. Alvinius. 2020. “Comparison within Gender and between Female and Male Leaders in Female-Dominated, Male-Dominated and Mixed-Gender Work Environments.” Journal of Gender Studies 29 (7): 739–750. doi:10.1080/09589236.2019.1638233.

- Lips, H. M. 2013. “The Gender Pay Gap: Challenging the Rationalizations. Perceived Equity, Discrimination, and the Limits of Human Capital Models.” Sex Roles 68 (3–4): 169–185. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0165-z.

- Liu, S. S. 2019. “Cracking Gender Stereotypes? Challenges Women Political Leaders Face.” Political Insight 10 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1177/2041905819838147.

- Lowndes, V. 2014. “How Are Things Done around Here? Uncovering Institutional Rules and Their Gendered Effects.” Politics & Gender 10 (04): 685–691. doi:10.1017/S1743923X1400049X.

- Mackay, F., M. Kenny, and L. Chappell. 2010. “New Institutionalism through a Gender Lens: Towards a Feminist Institutionalism?” International Political Science Review 31 (5): 573–588. doi:10.1177/0192512110388788.

- Mark, Kate, Katie Steel, Janet Stevenson, Christine Evans, Duncan McCormick, Lorna Willocks, Alison McCallum, et al. 2020. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Community Testing Team in Scotland: A 14-Day Review, 6 to 20 February 2020.” Eurosurveillance 25 (12): 1–6. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.12.2000217.

- Marks, Z. 2020. In a global emergency, women are showing how to lead. Washington Post April 21, 2020, Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/21/global-emergency-women-are-showing-how-lead/.

- Marshal, M. 2020. Scotland could eliminate the coronavirus if it weren’t for England. New Scientist October 19, 2020, Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2247462-scotland-could-eliminate-the-coronavirus-if-it-werent-for-england/.

- McArdle, H. 2020. Coronavirus in Scotland: 'Early' lockdown means death rate will be lower than rest of UK. Herald Scotland April 1, 2020. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/coronavirus/18348311.coronavirus-scotland-early-lockdown-means-death-rate-will-lower-rest-uk/.

- Minto, R., and L. Mergaert. 2018. “Gender Mainstreaming and Evaluation in the EU: comparative Perspectives from Feminist Institutionalism.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 20 (2): 204–220. doi:10.1080/14616742.2018.1440181.

- Murkherjee, J. S. 2007. “Structural Violence, Poverty and the AIDS Pandemic.” Development 50 (2): 115–121.

- National Records of Scotland, 2020. Stats at a Glance: Infographics and Visualizations. Accessed December 28, 2020, https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/stats-at-a-glance/infographics-and-visualisations#rgar-2018.

- Ontario Federation of Labour. 2007. 1900–2000: A Century of Women and Work. Toronto: Ontario Federation of Labour and the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre.

- Ontario Ministry of Finance 2020. Ontario Fact Sheet. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/ecupdates/factsheet.html

- Public Health Ontario. 2020. Data and Analysis. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/ Public Health Scotland. 2020. Data and intelligence. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/index.asp

- Queen’s Printer for Ontario. 2020a. Ontario Confirms Presumptive Case of COVID-19: All Protocols Followed and Risk to Ontarians Remains Low. Accessed July 11, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2020/02/ontario-confirms-presumptive-case-of-covid-19.html

- Queen’s Printer for Ontario. 2020b. Ontario Expands Coverage for Care: Enhanced Health Care Coverage Critical to Support Efforts to Contain COVID-19. Accessed July 11, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2020/03/ontario-expands-coverage-for-care.html

- Rubery, J., and A. Koukiadaki. 2018. “Institutional Interactions in Gender Pay Equity: A Call for Inclusive, Equal and Transparent Labour Markets.” University of Oxford Human Rights Hub Journal 1: 115–142.

- Runyan, A. S. 2019. Global Gender Politics. New York: Routledge.

- Ryan, M. K., S. A. Haslam, T. Morgenroth, F. Rink, J. Stoker, and K. Peters. 2016. “Getting on top of the Glass Cliff: Reviewing a Decade of Evidence, Explanations, and Impact.” The Leadership Quarterly 27 (3): 446–455. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.10.008.

- Schofield, T., and S. Goodwin. 2005. “Gender Politics and Public Policy Making: Prospects for Advancing Gender Equality.” Policy and Society 24 (4): 25–44. doi:10.1016/S1449-4035(05)70067-9.

- Scottish Government. 2020a. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Daily data for Scotland. Accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-daily-data-for-scotland/.

- Scottish Government 2020b. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Speech by Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport 3 March. Accessed November 4, 2020. https://www.gov.scot/publications/novel-coronavirus-covid-19-update/.

- Scottish Government. 2020c. Preparations for coronavirus stepped up. Accessed November 5, 2020. https://www.gov.scot/news/preparations-for-coronavirus-stepped-up/.

- Sergent, K., and A. D. Stajkovic. 2020. “ Women’s Leadership is Associated with Fewer Deaths During the COVID-19 Crisis: Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of United States Governors.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 105 (8): 771–783. doi:10.1037/apl0000577.

- Skyes, P. L. 2013. “Gendering Prime Ministerial Power.” In Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Strangio, P. ‘t Hart P. & Walter, J. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sridhar, D., and A. Chen. 2020. “Why Scotland’s Slow and Steady Approach to Covid-19 is Working.” BMJ 370: 1-2. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2669.

- Statistics Canada. 2020. Data. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data?text=ontario&geoname=A0002.

- Stirbu, D. S. 2011. “Female Representation beyond Westminster: Lessons from Scotland and Wales.” Political Insight 2 (3): 32–33. doi:10.1111/j.2041-9066.2011.00085.x.

- Swanborn, P. G. 2010. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Taub, A. 2020. Why Are Women-Led Nations Doing Better With Covid-19? New York Times May 15, 2020, Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/world/coronavirus-women-leaders.html.

- Trimble, L. 2018. Ms. Prime Minister: Gender, Media, and Leadership. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- The Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. Policy Paper: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Action Plan. Accessed July 28, 2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-action-plan.

- The Scottish Government. 2019. Scottish Government’s Response to the National Advisory Council on Women and Girls. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-governments-response-national-advisory-council-women-girls/.

- Thiec, A. 2010. “Women and Politics in Post Devolution Scotland.” Caliban 27 (27): 177–190. 2119 doi:10.4000/caliban.2119

- UNDP. 2020., The Economic Impacts of Covid-19 and Gender Inequality Recommendations for Policymakers. Panama: United Nations Development Programme.

- Wilson, J. 2018. Scotland Third in the World for Women’s Political Representation. Accessed July 28, 2020. http://angelacrawleymp.com/scotland-third-world-womens-political-representation/