Abstract

The global reach of COVID-19 presents opportunities to compare policy responses to the pandemic and the role of knowledge across political contexts. This article examines the case of Vietnam’s COVID-19 response. Recognized for its early effectiveness, Vietnam exhibits the standard characteristics of unitary states but has also engaged communities, strengthening the legitimacy of and buy-in to response efforts. This article identifies six factors that shaped Vietnam’s response to the pandemic: (i) command-and-control governance, (ii) extensive preparation, (iii) fostering cooperative sentiment and solidarity, (iv) political readiness and communication, (v) policy coordination, and (vi) adaptation. The article contributes to practical discussions about country-specific responses to the pandemic, and to scholarship on policy effectiveness and success within the policy sciences and public management.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is not merely a public health crisis but also raises questions about the management of uncertainty during novel crises and, more profoundly, public trust in expertise and governance under such circumstances. Referencing statistics about COVID-19 is a fraught undertaking, as they change daily; at the time of this article’s drafting, the number of cases worldwide was roughly 92 million.Footnote1 The perils of studying a crisis before its conclusion are well known. Nevertheless, the motivation behind this article is that there are lessons to take from early-stage crisis response, not only about public health but also about governance more generally.

This article seeks to identify such lessons in a country, Vietnam, with relative success in COVID-19 containment and mitigation. As the site where SARS was first recognized by the WHO in 2003, Vietnam has a curious recent history with pandemics (WHO Citation2003) – one that serves its preparation, as later described. Further, as a lower-middle-income country with a single-party authoritarian governance system, Vietnam is also comparable in case context to numerous other countries in the developing world.

This article has two aims: (i) to document Vietnam’s response strategies during the initial stages of the worldwide outbreak (roughly between January 2020 and October 2020); and (ii) to identify and reflect upon underlying factors that shaped Vietnam’s relatively effective response to the pandemic, with a focus on policy learning and lesson-drawing. Given these aims, the article contributes to scholarly debates about country-specific responses, which now constitute a rapidly growing body of literature (for case-based studies see Capano (Citation2020) (Italy), Hartley and Jarvis (Citation2020) (Hong Kong), Taneja and Bali (Citation2021), and Woo (Citation2020) (Singapore)). The conceptual approach of this article also engages with recent scholarship in public management focused on studying policy effectiveness, policy successes, and their determinants (Bali, Capano, and Ramesh Citation2019; Compton and ‘t Hart Citation2019; Douglas et al. Citation2019; Luetjens, Mintrom, and ‘t Hart Citation2019). In particular, it is appropriate to acknowledge the literature on policy effectiveness for a pandemic response (Baekkeskov and Öberg Citation2017; Moghadas et al. Citation2011; Bootsma and Ferguson Citation2007; Ferguson et al. Citation2006) and the growing policy-centered literature on response effectiveness for COVID-19 specifically (see, for example, the special issue of Policy and Society journal as summarized by Capano et al. Citation2020).

Among the useful frameworks for examining policy effectiveness (including FitzGerald, O’Malley, and Broin Citation2019; Nicklin Citation2019; Wolman Citation1981), we select that of Compton and ‘t Hart (Citation2019) to discuss Vietnam’s effectiveness across four dimensions: programmatic, processual, political, and temporal. These elements encompass factors that were critical to the early success in pandemic response achieved in Vietnam and other countries, including the content and mechanics of policies, the process by which the problem was understood and framed for policy response, and the power dynamics shaping the practice of policy development and implementation; given the collective breadth of these factors, the Compton and ‘t Hart framework offers the most comprehensive approach to analyzing the Vietnam case. Additionally, the framework adds a temporal dimension to Marsh and McConnell (Citation2010) framework, which includes the first three of these dimensions; consideration of a temporal dimension is warranted given the rapid emergence of the pandemic and the limited timeframe over which governments mobilized in response.

This article proceeds with a description of the Vietnam case, summarizing the country’s COVID-19 response policy history. This is followed by a discussion of six factors that were identified by this study to have substantially shaped Vietnam’s response. The concluding discussion draws on A brief set of lessons is drawn from this analysis.

2. Vietnam’s policy interventions to control COVID-19

2.1. Initial conditions

Vietnam’s COVID-19 outbreak was exceptionally modest in severity despite factors placing the country at, particularly high risk. As of 14 January, Vietnam has reported only 1521 infections, a majority of which (54%) were quarantined upon entry at the border and thus posed no risk to the general population. In Vietnam, months-long periods without community transmission have been punctuated by brief and rapidly contained outbreaks resulting in low mortality rates.Footnote2

The country’s early containment of the pandemic was unexpected given that Vietnam shares a border with China (where the pandemic is reported to have originated) and that China accounts for the highest number of visitors to Vietnam among all countries (nearly double the next highest country, South Korea, according to the most recent official statisticsFootnote3). Further, the initial outbreak occurred around the time of the Vietnamese new year, when a large share of the country’s 97 million inhabitants travel domestically and internationally. Compounding this challenge is the fact that two-thirds of cases in Vietnam were detected among people with no symptoms.Footnote4

Vietnam undertook preparations to manage COVID-19 even before the first case appeared in the country. As rumors emerged from China about a new respiratory disease, Vietnam tightened quarantine at the Vietnam-China border (3 January). Initial diagnosis and treatment guidelines were issued on 16 January and surveillance guidelines on 21 January.Footnote5

2.2. First wave

Vietnam’s first wave of COVID-19 infections began on 23 January, when a man from Wuhan was diagnosed. During this wave, 16 cases were confirmed, including eight inbound passengers and eight individuals from the community; the final case in this wave was detected on 12 February.

During this period, the main source of infection was China, so public health measures were initially focused on flights originating in China. These included strict port-of-entry screening procedures and mandatory health declarations by passengers, isolation of suspected cases, and eventually complete bans on flights to and from Wuhan and other affected areas. On 3 February, in response to the rapid rise of cases in China, Vietnam imposed a quarantine on all incoming passengers from COVID-19 affected areas in China, and later expanded the quarantine requirement to passengers arriving from Daegu, South Korea (another early COVID-19 “hot spot”).

Vietnam’s internal response to this first wave included measures to enhance cooperation among provinces and the assignment of responsibility for elements of response to various central ministries and agencies. Additional measures were instituted to prevent the virus from spreading into communities, including quarantine, isolation of suspected cases, voluntary isolation (for more distant contacts), and, in one case, the lockdown of a commune for three weeks due to an identified cluster of infections. Related measures were imposed to prevent hoarding and price-gouging for basic personal protection equipment (PPE) like face masks and hand sanitizer, while a transparent communication campaign was rolled out to inform the population.

2.3. Second wave

Over the period between the country’s first and second wave, Vietnam had a three-week stretch with no new infections. During this time, the government expanded travel restrictions from severely affected countries (e.g. South Korea, Iran, and Italy) and maintained school closures. However, compliance with mask-wearing and restrictions on gatherings began to slacken over time.

Vietnam’s second wave of infections began on 6 March. The growing number of asymptomatic inbound passengers who were later diagnosed with COVID-19 and capable of spreading it into communities captured the attention of policymakers. In several cases, people carrying COVID-19 were circulating for weeks before their cases were detected. However, once they were detected, Vietnam’s intensive contact-tracing and quarantine efforts were triggered to contain the spread. Vietnam imposed a 14-day mandatory quarantine administered in government facilities for all inbound passengers (starting 21 March) and suspended entry of all foreigners beginning on 22 March, eventually suspending all incoming commercial flights.

By this time, the disease had begun spreading in the community. In several disease clusters, no index case could be identified. When a large infection cluster was discovered at the largest hospital in the capital Hanoi in late March, more than 53,000 people were thought to have been at risk for exposure. Authorities quarantined nearly 29,000 people and performed 23,000 tests among health workers, patients, visitors, and the community surrounding the hospital, even locking down the hospital for several days. Ultimately, 45 cases were linked to this cluster including 28 employees of a food service contractor.

To contain further community spread during this second wave, schools remained closed and mass gatherings were prohibited from 28 March to 15 April. In addition, starting 1 April, the government imposed a two-week nationwide social distancing policy and restrictions on interprovincial travel. The government worked with retailers to ensure that the distribution of essential food and other items would not be disrupted. To prepare for a large number of cases, the government also issued guidance for hospital management on how to screen patients and prevent infection among health workers. Temporary field hospitals were established. Social distancing measures were extended another week until there was evidence of no new community transmission. Measures began to be lifted on 23 April. By early May, schools resumed operation, and by early June, bars and nightclubs were allowed to reopen. Life returned to relative normal within the country, even as COVID-19 raged in many other countries.

2.4. Continued measures

Into late July, Vietnam was maintaining restrictions on foreigners entering the country (with exceptions for diplomats and technical experts), but the government also arranged flights to repatriate large numbers of Vietnamese citizens stuck in countries around the world. Quarantine was still mandatory for all inbound passengers and for people crossing land or sea borders. While masks were still recommended, especially on public transport, they were no longer mandated and mask-wearing was no longer strictly enforced. Vigilance continued in testing and contact-tracing, and violations of quarantine and illegal entry across land borders were prosecuted.

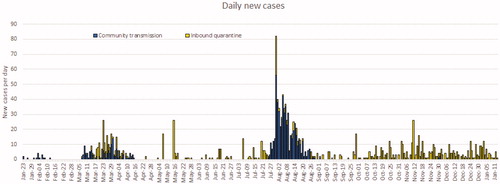

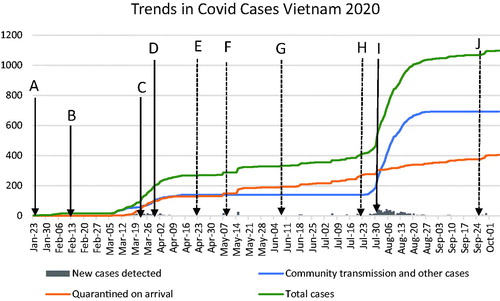

Nevertheless, on 25 July, after 99 days without community transmission, a new COVID-19 case was confirmed in Da Nang, with no known index case nor the history of international travel. Two dozen non-Vietnamese individuals who evaded quarantine were also found in neighboring provinces and immediately tested and quarantined. Thus, Vietnam’s robust mitigation efforts were rebooted. Contact tracing immediately identified over 100 people to be tested and 50 people to be put into isolation, with numbers increasing over time. The Da Nang airport was closed and two hospitals were locked down. Advisory teams and representatives of the central government were sent from Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City to guide local public health workers in door-to-door screening exercises to identify symptomatic individuals for testing. Masks reemerged throughout the country and trips to Da Nang, a popular beach destination in the summer, were canceled. Rapid public health response to COVID-19 played an important role in reducing community transmission across Vietnam (see and ; ).

Figure 1. Timeline of Vietnam’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic (first 8 months). Note: solid vertical lines corresponding to the letters indicate the institution of a given containment measure, and dashed or gray lines indicate a removal of a given containment measure.

Table 1. Overview of Vietnam government’s initial response (corresponding to ).

3. Success factors for COVID-19 mitigation

In turning to an examination of underlying factors that facilitated Vietnam’s policy response to the pandemic, this sections’ goal is two-fold. First, it aims to identify factors that allowed Vietnam to effectively design and implement the measures described in the previous section. Second, it aims to identify emerging propositions from Vietnam’s experience of continued mitigation of COVID-19 that can be instructive to other countries in how similar crises can be approached in the future. These are necessary first steps in lesson drawing or policy learning.

Scholars have cataloged Vietnam’s policy response, with success attributed to a variety of factors, including “mass mobilization of the health care system, public employees, and the security forces, combined with an energetic and creative public education campaign” (Black Citation2020); swift policy action, prioritization of public health above economic considerations, and the deployment of government and civil society organizations in a “whole of society” approach (IMF Citation2020); mobilization of the political system and a “proactive and comprehensive” response by the healthcare system (Hoang et al. Citation2020); and preparation, mass testing, and isolation (Quach and Hoang Citation2020).

This study extends this emerging literature by deepening the discussion of governance-related success factors, with supporting information derived from official documents, academic literature, and press publications; interviews were conducted to clarify findings and generate additional insights. Interviewees include public policy experts specializing in Vietnam, government officials, and stakeholders working across various health agencies. Factors examined are: (i) command-and-control governance, (ii) extensive preparation, (iii) fostering cooperative sentiment and solidarity, (iv) political readiness and communication, (v) policy coordination, and (vi) adaptation. It is noted that these six factors are emerging propositions that should be interrogated further in comparative studies and as the pandemic’s impact becomes clearer. Furthermore, the novelty of our analysis lies in the collective analysis of the below factors, which bring already existing information together with insights offered by interviewees.

(i) Command-and-control governance. The command-and-control architecture of Vietnam’s administrative systems facilitated more effective coordination to manage activities for pandemic mitigation; these included isolation of positive or at-risk cases, surveillance, restrictions on movement, and targeted mobilization of resources to high-need areas. Strict controls at national borders controls at provincial borders during a particularly uncertain period in March 2020, and the quarantine or isolation of individuals, hospitals, and entire localities where outbreaks were discovered were the cornerstones of top-down mitigation efforts (Nguyen and Vu Citation2020; Pham et al. Citation2020; Thanh et al. Citation2020). The same spirit of command-and-control governance is also predicted to serve the post-pandemic economic recovery effort through fiscal stimulus and public investment (Morisset Citation2020).

Vietnam has a history of tightly coordinated crisis responses, with the same command-and-control approach used in response to the initial outbreaks of Avian Influenza (2003–2004). Indeed, the country’s COVID-19 mitigation approach reflects the institutional vestiges of socialism (Vu Citation2009): the absence of local input, little involvement of private citizens, and low reliance on social or market demand. At the same time, Vietnam’s administrative structures played a role in virus containment and mitigation. Vietnam’s communist organizational structures extend to the city block and village hamlet. These structures are somewhat loose, but can quickly be mobilized to inform the community in a crisis, conduct contact tracing, or investigate matters related to individuals’ travels or evasion of quarantine procedures. The consequent rise of a “power narrative” enabled an environment where “central officials asserted their power and control over the situation, regardless of the reality on the ground” (Vu Citation2009, 22).

At a higher level, the Vietnam case illustrates that central and local pandemic response efforts were effectively harmonized, facilitated in large part by the unitary state apparatus through which policies are coordinated horizontally across central government units and vertically from central to local levels. The case is a stark contrast to some countries like the United States, where central control and coordination during the early stages of the pandemic were weak, inconsistent, and self-contradictory, leading to catastrophic levels of infection and fatality (Rocco, Béland, and Waddan Citation2020). It is appropriate, however, to acknowledge that central-local coordination can be a challenge even within unitary systems, if not for political reasons then for managerial and institutional ones. Accordingly, Vietnam’s unitary system is no guarantee of tight vertical coordination on all policy matters, nor should it be presented as a fail-proof model for replication. For example, Fritzen (Citation2005) notes that Vietnam’s anti-corruption initiatives failed to be fully implemented at the local level due to deficiencies in policy design and institutional settings that weakened compliance incentives. While the issue of corruption may be considered a uniquely challenging coordination task given local leaders’ predictable resistance to self-policing, Vietnam’s experience illustrates that a unitary state apparatus cannot be considered a categorical necessity in coordinating policy implementation. Nevertheless, evidence indicates that in the case of pandemic response, rapid and effective policy coordination owes at least some debt to the unitary system.

(ii) Extensive preparation. Vietnam was relatively well prepared to manage the COVID-19 pandemic by virtue of its capacity, expertise, and coordination practices across the health sector. Much of this preparatory posture is the product of decades of engagement with global health organizations. For example, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have been working with government and local organizations in Vietnam since 1998 (CDC Citation2019), providing guidance on issues like disease screening, prevention, and laboratory capacity, among others. Vietnam’s willingness to observe globally recommended protocols also enhanced its COVID-19 preparedness. An example is the World Health Organization’s (WHO) longstanding recommendations about pandemics preparedness, which were embraced by Vietnam’s government and effectively informed its response strategy (Quach and Hoang Citation2020); this guidance included not only response capacity but also scenario and preparedness planning, networking among public health facilities, and contact-tracing systems. The WHO recommendations embrace a “one health” approach that emphasizes interdisciplinary perspectives across all health and social sciences (El Zowalaty and Järhult Citation2020; Kelly et al. Citation2017). To institutionalize and coordinate its response in accordance with these principles, Vietnam established a formal committee for a pandemic response as early as the 30th of January (Nguyen et al. Citation2020).

While Vietnam was largely successful at the early stages of the pandemic, readiness was not necessarily uniform across all dimensions of society. For example, Tran, Hoang, et al. (Citation2020) argue that operational readiness among grassroots health providers was only moderately effective, with less relative vulnerability among organizations in urban areas and Northern regions. Local and “grassroots” providers include pharmacies, community health centers, providers of traditional medicine, and other organizations involved in the detection and reporting that Tran, Vu, et al. (Citation2020) argue are crucial for serving vulnerable populations like laborers and workers. According to Hoang (Citation2021), “the grassroots health system mobilized and prioritized all its [Vietnam’s] financial resources (from the State budget and contributions from donors, charity funds, and community people) to make ready essential equipment, medicines, and medical supplies for prevention and control of the epidemic” (1). As such, the Vietnam case illustrates how preparation was aligned across public and private organizations – a point that is later elaborated in the fifth factor.

Additionally, it should be noted that Vietnam’s preparation emerged also from its experience in responding to past healthcare crises. Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries have a well-documented history with pandemics, including SARS, Avian Influenza, and Swine Flu. Once again, Vietnam’s global engagement in the management of pandemics has a deep legacy. In 2003–2004, the World Bank, the European Union, and the government of Japan provided support for Vietnam’s Avian Influenza recovery efforts, including the capacity for veterinary diagnostics and surveillance (Vu Citation2009).Footnote6 Experiences with pandemics have led to the longer-term development not only of institutional preparedness (Thu Citation2020) but also of “social memory,” which has been shown instrumental in nudging people to adopt protective behaviors and heed official regulations and guidance in other COVID-19 response contexts (Hartley and Jarvis Citation2020) and reflects the contribution of Vietnam’s public.

(iii) Fostering cooperative sentiment and solidarity. The Vietnam government’s ability to rally the public around sentiments like nationalism and heroism in the fight against a common enemy (Le Citation2020; Vu and Tran Citation2020) was a powerful force in generating solidarity and support for response measures. This can be traced in part to regional politics; Vietnam has long-running territorial disputes with China concerning the sovereignty over islands in the South China Sea (Cotillon Citation2017; Thayer Citation2011), priming the public with what was already a skeptical view of China grounded in historical factors (Hoang Citation2019; Vu Citation2014). The early narrative about COVID-19 was that it was a disease originating in China, like SARS. The political corollary was that if the Vietnam government allowed the disease to invade from China, the public would be substantially disappointed with the government.

This kind of political motivation for the government’s pandemic response is not without precedent. According to Vu (Citation2009), in 2003–2004 “the nationalist narrative tried to convince the Vietnamese that a victory over the AI [Avian Influenza] epidemic was a matter of national pride and honor for Vietnam” (25). The current COVID-19 success may be leading to warmer political sentiments on the part of the public. According to Luong (Citation2020), “a renewed trust in the government also surfaced. Known in recent years as a regime with little tolerance for political dissent, the Vietnamese government and its medical apparatus have received considerable praise at home and abroad for their expediency [in COVID-19 response]” (46).

Beyond these political factors, social solidarity and unity have arguably played a substantial role (Huynh Citation2020; Trevisan, Le, and Le Citation2020). These sentiments imply an attitude of self-sacrifice on behalf of the broader community, a value that may be explained in part through Vietnam’s socialist history and decades-long struggle for sovereignty. It is important, however, not to allow this grander narrative to minimize the practical individual motivation to keep family, friends, and neighbors safe through social distancing and other measures. According to Trevisan, Le, and Le (Citation2020), “reports from the media indicate that, in time of severe crisis, people in many countries may be willing and prepared to accept more restrictive actions to save lives” (1153). As willingness to embrace social distancing was credited with helping mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in Vietnam (Nguyen et al. Citation2020), examinations of the underlying motivation should acknowledge nationalism and solidarity as important but not sole determinants of effectiveness. The relationship between these factors and human or institutional behaviors deserves further research.

(iv) Political readiness and communication. From the inception of the pandemic, Vietnam demonstrated political readiness and communication capacities to mitigate COVID-19 (Bui et al. Citation2020; Huynh Citation2020; Trevisan, Le, and Le Citation2020). According to La et al. (Citation2020), “timely communication on any developments of the outbreak from the government and the media, combined with up-to-date research on the new virus by the Vietnamese science community, have altogether provided reliable sources of information” (2931). This use of social media and ‘science journalism’ was effective in informing the general public, with particular messages for subgroups of the population having certain needs. According to Le (Citation2020), “responses were also tailored to speak to the needs of targeted groups, including older people.” In contrast to the Chinese approach of controlling information flow, Vietnamese authorities appeared to prioritize transparency and allowed information exchange through social media channels like Facebook; this approach exhibited how Vietnam, in the words of Le and Nguyen (Citation2020), combined democratic principles with authoritarian practice in a way that fostered trust and government legitimacy among the public. Long-time Vietnam expert Adam Fforde captured the tenuous balance between popular distrust and legal compliance in the following statement:

As such, it combined consensual popular compliance (and so more and better selfpolicing) with sound policies with both societal and leadership pressure upon officials to ‘step up’. Popular authorisation, responding to political signals that deployed deep and powerful meanings, therefore increased the power of the state; officials in the public health sector, a sector riddled by corruption, were therefore praised and criticised in ways that worked in Vietnam for the Vietnamese. This has led to success ‘so far’. (Fforde Citation2020)

The credibility of Vietnam’s government and public health communication efforts was also strengthened by the public’s perception about Vietnam’s improved governance. According to Nguyen and Malesky (Citation2020), “Vietnam’s strengthened state capacity during these past months is the culmination of a deliberate, sustained effort to improve governance…upward trends in healthcare access, transparency, and overall local governance suggest that effective local-central coordination plays an important role implementing national policies” (n.p.). At a broad level, the case illustrates that source credibility and trust in government are crucial factors in crisis moments that call for public communications to influence behavior.

(v) Cross-sector cooperation. The fifth success factor explored in this study concerns the role of cooperation among government, the private sector, civil society, and individuals (Duong, Le, and Bui Citation2020; La et al. Citation2020). The collaborative model is reflected in the country’s multi-sectoral approach, as described by Bui et al. (Citation2020): “emergency control measures in the epidemic areas and integration of resources from multiple sectors including health, mass media, transportation, education, public affairs, and defense” (1). Drawing on knowledge resources and capacities from across multiple sectors and ministries, the Vietnam government was able to understand the complexities of the pandemic and recognize how it would impact multiple facets of society. Enabling this “whole-of-society” model (IMF Citation2020) was a “synchronous” strategy that emerged from the collective and often self-sacrificial efforts of various stakeholders and communities (Nguyen et al. Citation2020). Bui et al. (Citation2020, 4) provide a graphic that maps various collaborators and their role in the coordinated national response, accounting for nearly all major national ministries, industry, and the business sector.

(vi) Adaptation. Finally, Vietnam has exhibited adaptive capabilities in its COVID-19 response. Vietnam’s early response, including the period prior to mandatory quarantine for incoming passengers, did not exhibit the type of adaptation that later characterized its more successful response. Early cases of COVID-19 exhibited some notable patterns. Vietnam’s first two cases came from China, and after contact tracing, authorities were able to identify a hotel receptionist infected by these individuals. However, there was no additional identified transmission – a peculiarity given that these individuals traveled extensively around the country before developing symptoms. In another case, an American citizen traveling from Wuhan to Ho Chi Minh City in early January 2020 moved around freely within the country for two weeks before being admitted to the hospital. This was then followed by 12 cases in a single commune in Vinh Phuc, including several Vietnamese workers returning from Wuhan to visit family during the Tet holiday and transmission cases in the community they visited.

These instances – neither of which resulted in further transmission – exhibit that, even in a setting established to detect cases and mitigate transmission, the immediacy and unexpectedness of an acute-onset crisis left some period of time in which few systematic response efforts were made. Nevertheless, Vietnam eventually adapted, even without a significant increase in cases, by instituting stricter measures based on scientific and epidemiological data. The government paid close attention to new knowledge and evidence as it emerged, and appeared to incorporate the findings into evolving sets of interventions (Nguyen et al. Citation2020). According to Acosta and Nestore (Citation2020), “As COVID-19 evolved, both central and local governments continually amended and created new policies” (3). Examples of such efforts are the creation of web pages and mobile applications, the collection and analysis of data to inform preventive or anticipatory exercises, and targeted isolation and quarantine measures for higher-risk areas. The training of healthcare professionals, including those operating at various levels of the health system, also enabled Vietnam to adjust capacity where needed in accordance with updated response guidelines (Nguyen et al. Citation2020). While these approaches reflected due preparedness, it was the flexibility and capacity to respond rapidly and decisively in most policy arenas that helped Vietnam stay ahead of the pandemic’s progression through three waves.

4. Conclusion: assessing effectiveness in policy responses

The primary focus of this article has been to trace Vietnam’s policy responses to the pandemic and identify factors that enabled these responses to be designed and implemented. As shows, by conventional public health standards (i.e. community transmission and the total number of cases) Vietnam’s initial response to the pandemic was effective. The country’s health system, which differs from that of many other countries with similar levels of economic development (e.g. India, Indonesia, and the Philippines) was not unduly stressed for capacity and expertise by the pandemic. However, assessing the success and effectiveness of public policies is more difficult for an ongoing rather than one-time crisis; indeed, there remains uncertainty about the continued spread of COVID-19, and countries around the world continue to experience additional waves of transmission after successful initial containment. Moreover, competing narratives and metrics of success (e.g. the tradeoff between potentially life-saving shutdowns and economic continuity) are beyond the scope of this article but are material factors in the analysis of how success is socially and politically constructed. Despite these methodological challenges, this analysis of Vietnam’s pandemic responses illustrates some lessons for responding to future crises.

Compton and ‘t Hart (Citation2019) offer a useful framework that this study uses to frame the following analysis. The framework focuses on identifying success across four dimensions, as described in . On programmatic, processual, and political dimensions, Vietnam’s early responses were largely effective. Regarding the programmatic dimension, Vietnam limited the rise of case counts and curbed community outbreaks. In October 2020, roughly ten months after the virus began measurably spreading around the world, Vietnam was one of the few low middle-income countries with a relatively small number of cases (1098). Moreover, Vietnam managed the pandemic better than other major economies in Asia having broadly similar levels of economic development (e.g. India, Indonesia, and the Philippines). On the processual dimension, despite geographical variations in “grassroots” preparedness as described in Section 3, containment measures were largely perceived as fair and just. This is arguably attributable in part to efforts by the government to foster cooperative national sentiment and solidarity. It is difficult to assess effectiveness on the political dimension given the absence of electoral competition in Vietnam. However, there is some evidence of general trust in government and public support for measures introduced,Footnote7 sustained in part by consistent, targeted, and credible communication throughout the pandemic. The temporal dimension is better assessed at a later time, as the nature of the virus and conditions “on the ground” appear to be constantly changing. However, it is reasonable to anticipate that Vietnam would perform well on the temporal dimension; as and the discussion in the preceding section highlight, the country has been quick to adjust and calibrate existing measures in response to new outbreaks.

Table 2. Dimensions of policy effectiveness in Vietnam case.

It is appropriate to note where Vietnam’s COVID-19 response challenges and other shortcomings still exist. First, hospitals and healthcare providers should continue to be incentivized to maintain diligence and observe protocols and procedures, a challenging task to maintain over time given the resources needed and the pressure to relax amidst extended periods of successful containment. Second, the type of weak governance capacities characterizing many middle-income countries (Rani, Nusrat, and Hawken Citation2012; Block and Mills Citation2003) may surface in the course of Vietnam’s response to future outbreaks; an example is a case, already mentioned, in which two dozen people were able to evade quarantine when crossing the land border. Third, while sustained economic growth and low infection count have helped strengthen the government’s legitimacy, it is uncertain how long personally restrictive and economically burdensome measures will be perceived by the public as reasonable and fair. This is a challenge that is relevant in any society but invites observation in the Vietnam case due to the country’s political system and use of collective narrative to generate support and compliance for such measures. Other issues of concern include lapses in diligence in properly and consistently wearing masks in public spaces. There is also lingering concern about the country’s long borders, which compound opportunities for malfeasance as people arriving illegally seek to evade quarantine. When apprehended by border authorities, some arrivals offer bribes to overlook the absence of proof that they served quarantine, including when registering at hotels or with local police. Finally, there is the possibility that hospitals are not thorough in ordering testing for patients with possible COVID-19 symptoms. This is one of the factors that led to the aforementioned Da Nang outbreak, as some early cases exhibited symptoms but doctors were unduly optimistic about the country’s containment and thus did not order tests. These challenges range from the high-level and broad to the micro-level and managerial. Despite Vietnam’s success, it is crucial for the country not to lose focus – even as containment and mitigation efforts grow more costly and inconvenient and measures are undertaken to re-start the economy (e.g. relaxing mask mandates and allowing international travel).

In closing, this study makes two contributions. First, the academic literature exhibits how a commonly used framework for analyzing policy success can systematically categorize insights derived from inductive examination and reflection about policy issues of many types (not only public health and pandemic response). While the study illuminates pathways for policy effectiveness that are unique to a particular type of political-administrative system (i.e. a one-party unitary state), some of the more technical aspects of policy response, such as policy preparation and capacity to integrate new data and feedback into policy designs and calibrations, are applicable to a variety of political-administrative settings and can be studied as such. This proposition suggests opportunities for further research comparing policy responses within and across system types, enriching long-running debates about the influence of political and institutional variables. Concerning the second contribution, to both the academic literature and body of practical knowledge this study offers a wide-ranging account of policy-related (non-clinical) factors that in combination helped to contain and mitigate the pandemic. These insights can be instructive for Vietnam’s response to future health crises and also offer insights for other countries. At the same time, it will be important for policy learning and transfer activities to note the particularities of the Vietnam case with regard to the political system, national history and its impact on culture and solidarity, and other factors that hinder generalizability. To facilitate more rigorous lesson-drawing, the insights of this study will require empirical examination in heterodox policy contexts and over a longer period of time, as the crisis and its fallout further unfold.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html accessed 10 Jan 2021

2 Source: Rapid Response Information Team of the COVID-19 pandemic control National Steering Committee of the General Department of Preventive Medicine. SARS COVID-19 Webpage. Figure on cases by age group.

Accessed on 19 July 2020. https://ncov.vncdc.gov.vn/pages/viet-nam-1.html

3 Source: Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. https://vietnamtourism.gov.vn/english/index.php/cat/15 Accessed on 13 Jan 2021.

4 For additional and updated statistics, see: https://ncov.moh.gov.vn/web/guest/trang-chu and https://ncov.vncdc.gov.vn/pages/viet-nam-3.html

5 La et al. (Citation2020, 8)

6 For COVID-19, the World Bank and government of Australia have pledged funding for economic recovery efforts (World Bank Citation2020a) and the World Bank has developed policy guidance for Vietnam’s efforts to manage the economic effects of COVID-19 (World Bank Citation2020b).

References

- Acosta, M., and M. Nestore. 2020. “Comparing Public Policy Implementation in Taiwan and Vietnam in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Review.” SocArXiv 2020 (4): 1–7. https://philpapers.org/rec/ACOCPP.

- Baekkeskov, E., and P. Öberg. 2017. “Freezing Deliberation through Public Expert Advice.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (7): 1006–1026. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1170192.

- Bali, A. S., G. Capano, and M. Ramesh. 2019. “Anticipating and Designing for Policy Effectiveness.” Policy and Society 38 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/14494035.2019.1579502.

- Black, G. 2020. “Vietnam May Have the Most Effective Response to Covid-19.” The Nation, April 24. https://www.thenation.com/article/world/coronavirus-vietnam-quarantine-mobilization/

- Block, M. A. G., and A. Mills. 2003. “Assessing Capacity for Health Policy and Systems Research in Low and Middle Income Countries.” Health Research Policy and Systems 1 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-1-1.

- Bootsma, M. C., and N. M. Ferguson. 2007. “The Effect of Public Health Measures on the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in US Cities.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (18): 7588–7593. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611071104.

- Bui, T. T. H., N. Q. La, T. Mirzoev, T. T. Nguyen, Q. T. Pham, and C. D. Phung. 2020. “Combating the COVID-19 Epidemic: Experiences from Vietnam.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (9): 3125. doi:10.3390/ijerph17093125.

- Capano, G. 2020. “Policy Design and State Capacity in the COVID-19 Emergency in Italy: If You Are Not Prepared for the (un) Expected, You Can Be Only What You Already Are.” Policy and Society 39 (3): 326–344. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783790.

- Capano, G., M. Howlett, D. S. Jarvis, M. Ramesh, and N. Goyal. 2020. “Mobilizing Policy (in) Capacity to Fight COVID-19: Understanding Variations in State Responses.” Policy and Society 39 (3): 285–308. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1787628.

- CDC. 2019. “CDC in Vietnam”. CDC. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/79172

- Compton, M., and P. T. ‘t Hart, (Eds.). 2019. Great Policy Successes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- Cotillon, H. 2017. “Territorial Disputes and Nationalism: A Comparative Case Study of China and Vietnam.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 36 (1): 51–88. doi:10.1177/186810341703600103.

- Douglas, S., P. ‘t Hart, C. Ansell, L. B. Andersen, M. Flinders, B. Head, D. Moynihan, et al. 2019. “Towards Positive Public Administration: A Manifesto.” Positive Public Administration. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336362499_Towards_Positive_Public_Administration_A_Manifesto

- Duong, D. M., V. T. Le, and T. T. H. Bui. 2020. “Controlling the COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam: Lessons from a Limited Resource Country.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 32 (4): 161–162. doi:1010539520927290.

- El Zowalaty, M. E., and J. D. Järhult. 2020. “From SARS to COVID-19: A Previously Unknown SARS-Related Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of Pandemic Potential Infecting Humans - Call for a One Health Approach.” One Health 9: 100124. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100124.

- Ferguson, N. M., D. A. Cummings, C. Fraser, J. C. Cajka, P. C. Cooley, and D. S. Burke. 2006. “Strategies for Mitigating an Influenza pandemic.” Nature 442 (7101): 448–452. doi:10.1038/nature04795.

- Fforde, A. 2020. “Vietnam and COVID-19: More Mark (Zuckerberg) than Marx.” Melbourne Asia Review, October 29. https://melbourneasiareview.edu.au/vietnam-and-covid-19-more-mark-zuckerberg-than-marx/?print=pdf

- FitzGerald, C., E. O’Malley, and D. Ó. Broin. 2019. “Policy Success/Policy Failure: A Framework for Understanding Policy Choices.” Administration 67 (2): 1–24. doi:10.2478/admin-2019-0011.

- Fritzen, S. 2005. “The ‘Misery’ of Implementation: Governance, Institutions and anti-Corruption in Vietnam.” In Governance, Institutions and anti-Corruption in Asia New Zealand Asia Institute. Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland; Chengchi, Taiwan: National Chengchi University.

- Hartley, K., and D. S. Jarvis. 2020. “Policymaking in a Low-Trust State: Legitimacy, State Capacity, and Responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong.” Policy and Society 39 (3): 403–421. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791.

- Hoang, P. 2019. “Domestic Protests and Foreign Policy: An Examination of anti-China Protests in Vietnam and Vietnamese Policy towards China regarding the South China Sea.” Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs 6 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1177/2347797019826747.

- Hoang, V. M. 2021. “Proactive and Comprehensive Community Health Actions to Fight the COVID‐19 Epidemic: Initial Lessons from Vietnam.” The Journal of Rural Health 37 (1): 148. doi:10.1111/jrh.12430.

- Hoang, V. M., H. H. Hoang, Q. L. Khuong, N. Q. La, and T. T. H. Tran. 2020. “Describing the Pattern of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Vietnam.” Global Health Action 13 (1): 1776526. doi:10.1080/16549716.2020.1776526.

- Huynh, T. L. D. 2020. “The COVID-19 Containment in Vietnam: What Are we Doing?” Journal of Global Health 10 (1): 010338. doi:10.7189/jogh.10.010338.

- IMF. 2020. “Vietnam’s Success in Containing COVID-19 Offers Roadmap for Other Developing Countries.” International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/29/na062920-vietnams-success-in-containing-covid19-offers-roadmap-for-other-developing-countries

- Kelly, T. R., W. B. Karesh, C. K. Johnson, K. V. Gilardi, S. J. Anthony, T. Goldstein, S. H. Olson, C. Machalaba, and J. A. Mazet. 2017. “One Health Proof of Concept: Bringing a Transdisciplinary Approach to Surveillance for Zoonotic Viruses at the Human-Wild Animal Interface.” Preventive Veterinary Medicine 137 (B): 112–118. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.11.023.

- La, V.-P., T.-H. Pham, M.-T. Ho, M.-H. Nguyen, K.-L. P. Nguyen, T.-T. Vuong, H.-K. T. Nguyen, et al. 2020. “Policy Response, Social Media and Science Journalism for the Sustainability of the Public Health System amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Vietnam Lessons.” Sustainability 12 (7): 2931. doi:10.3390/su12072931.

- Le, L. 2020. “Nationalism, Heroism and Media in Vietnam’s War on COVID-19.” East Asia Forum, June 24. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/06/24/nationalism-heroism-and-media-in-vietnams-war-on-covid-19/

- Le, T. T. 2020. “Social Responses for Older People in COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience from Vietnam.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 63 (6–7): 682–687. doi:10.1080/01634372.2020.1773596.

- Le, T. V., and H. Q. Nguyen. 2020. “How Vietnam Learned from China’s Coronavirus Mistakes.” The Diplomat, March 17. https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/how-vietnam-learned-from-chinas-coronavirus-mistakes/

- Luetjens, J., M. Mintrom, and P. ‘t Hart. 2019. Successful Public Policy: Lessons from Australia and New Zealand. Acton, Australia: ANU Press.

- Luong, T. 2020. “COVID-19 Dispatches from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.” Anthropology Now 12 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1080/19428200.2020.1761209.

- Marsh, D., and A. McConnell. 2010. “Towards a Framework for Establishing Policy Success.” Public Administration 88 (2): 564–583. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01803.x.

- Moghadas, S. M., N. J. Pizzi, J. Wu, S. E. Tamblyn, and D. N. Fisman. 2011. “Canada in the Face of the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic.” Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 5 (2): 83–88. doi:10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00184.x.

- Morisset, J. 2020. “Vietnam: Potential Policies Responses to the COVID-19 Epidemic.” World Bank Group. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/33779

- Nguyen, T. H., and D. C. Vu. 2020. “Summary of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Vietnam–Lessons and Suggestions.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 37: 101651. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101651.

- Nguyen, T. M., and E. Malesky. 2020. “Reopening Vietnam: How the Country’s Improving Governance Helped It Weather the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/05/20/reopening-vietnam-how-the-countrys-improving-governance-helped-it-weather-the-covid-19-pandemic/?utm_source=feedblitz&utm_medium=FeedBlitzRss&utm_campaign=brookingsrss/topfeeds/latestfrombrookings

- Nguyen, V. H., V. M. Hoang, A. T. M. Dao, H. L. Nguyen, V. T. Nguyen, P. T. Nguyen, Q. K. Le, P. M. Le, and S. Gilmour. 2020. “An Adaptive Model of Health System Organization and Responses Helped Vietnam to Successfully Halt the Covid‐19 Pandemic: What Lessons Can Be Learned from a Resource‐Constrained Country.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 35 (5): 988–992. doi:10.1002/hpm.3004.

- Nicklin, G. 2019. “Dynamic Narrative: A New Framework for Policy Success.” International Review of Public Policy 1 (2): 173–193. doi:10.4000/irpp.550.

- Pham, T. D., T. L. Dao, D. T. Nguyen, T. T. Dao, Q. H. Dang, X. C. Do, V. D. Pham, et al. 2020. “Epidemiological Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients in Vietnam and a Description of Disease Control and Prevention Measures in Thai Binh Province.” Preprints, May 11. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202005.0197/v1

- Quach, H.-L., and N.-A. Hoang. 2020. “COVID-19 in Vietnam: A Lesson of Pre-Preparation.” Journal of Clinical Virology 127: 104379. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104379.

- Rani, M., S. Nusrat, and L. H. Hawken. 2012. “A Qualitative Study of Governance of Evolving Response to Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Current Status, Risks and Options.” BMC Public Health 12 (1): 877. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-877.

- Rocco, P., D. Béland, and A. Waddan. 2020. “Stuck in Neutral? Federalism, Policy Instruments, and Counter-Cyclical Responses to COVID-19 in the United States.” Policy and Society 39 (3): 458–477. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783793.

- Taneja, P., and A. S. Bali. 2021. “India’s Domestic and Foreign Policy Responses to COVID-19.” The Round Table. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/00358533.2021.1875685.

- Thanh, H. N., T. N. Van, H. N. T. Thu, B. N. Van, B. D. Thanh, H. P. T. Thu, A. N. T. Kieu, et al. 2020. “Outbreak Investigation for COVID-19 in Northern Vietnam.” The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 20 (5): 535–536. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30159-6.

- Thayer, C. A. 2011. “The Tyranny of Geography: Vietnamese Strategies to Constrain China in the South China Sea.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 33 (3): 348–369. doi: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41446234.

- Thu, H. L. 2020. “Vietnam: A Successful Battle against the Virus.” Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/vietnam-successful-battle-against-virus

- Tran, B. X., M. T. Hoang, H. Q. Pham, C. L. Hoang, H. T. Le, C. A. Latkin, C. S. Ho, and R. C. Ho. 2020. “The Operational Readiness Capacities of the Grassroots Health System in Responses to Epidemics: Implications for COVID-19 Control in Vietnam.” Journal of Global Health 10 (1): 011006. doi:10.7189/jogh.10.011006.

- Tran, B. X., G. T. Vu, C. A. Latkin, H. Q. Pham, H. T. Phan, H. T. Le, and R. C. Ho. 2020. “Characterize Health and Economic Vulnerabilities of Workers to Control the Emergence of COVID-19 in an Industrial Zone in Vietnam.” Safety Science 129: 104811. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104811.

- Trevisan, M., L. C. Le, and A. V. Le. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic: A View from Vietnam.” American Journal of Public Health 110 (8): 1152–1153. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305751.

- Vu, T. 2009. The Political Economy of Avian Influenza Response and Control in Vietnam. Brighton, UK: STEPS Centre. STEPS Working Paper 19.

- Vu, T. 2014. “The Party vs. the People: Anti-China Nationalism in Contemporary Vietnam.” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 9 (4): 33–66. doi:10.1525/vs.2014.9.4.33.

- Vu, M., and B. T. Tran. 2020. “The Secret to Vietnam’s COVID-19 Response Success.” The Diplomat, April 18. https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/the-secret-to-vietnams-covid-19-response-success/

- WHO. 2003. “WHO Issues a Global Alert about Cases of Atypical Pneumonia.” World Health Organization, May 14. http://www.who.int/csr/sarsarchive/2003_03_12/en/

- Wolman, H. 1981. “The Determinants of Program Success and Failure.” Journal of Public Policy 1 (4): 433–464. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00002336.

- Woo, J.J., 2020. Policy capacity and Singapore's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy and Society, 39(3), pp.345–362.

- World Bank. 2020a. “World Bank Group, Australia to Support Vietnam Mitigate Impacts of COVID-19 and Facilitate Economic Recovery.” https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/24/world-bank-group-australia-to-support-vietnam-mitigate-impacts-of-covid-19-and-facilitate-economic-recovery

- World Bank. 2020b. “COVID-19 Policy Response Notes for Vietnam.” https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33998/COVID-19-Policy-Response-Notes-for-Vietnam-Compilation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y