Abstract

Governments across the globe have expressed their interest in forms of codesign and coproduction as a useful tool for crafting policy solutions. Genuine relationships between partners are seen as an important way to build meaningful and lasting impact for policy. One area of interest in this space has been on how researchers and policymakers can work better together to design and produce more evidence-based policies. For many practitioners and researchers, knowledge coproduction is presented as a panacea to the ongoing challenges of research translation. It is positioned as assisting in building more meaningful, trusting relationships which, in turn, support the development of more effective policy solutions. Using the insider experience of a coproduced government project in Queensland, Australia, this paper reflects on the realities and tensions between this idealism associated with policy co-production methodologies and the ongoing messiness of public policy practice. Beginning with an overview of the literature on coproduction, followed by a brief introduction to the case and the method used, the paper concludes by highlighting the strengths, facilitators and benefits of the approach while raising questions about whether coproduction is a panacea to research translation concerns or a placebo. The answer, we argue, lies more in how success is defined than any concrete solution.

1. Introduction

Knowledge coproduction has been an area of interest to policymakers over the last decade (Loeffler Citation2021). However, much of the focus has been on the inclusion of citizens and external stakeholders. A smaller body of work explores the role of co-producing knowledge between academics and researchers for policy (Ward et al. Citation2021; Hartley and Benington Citation2000; Buick et al. Citation2016). The desire to engage with research and expert knowledge gained prominence in response to the push for evidence-based policy that became popular in the UK under the Blair/Brown Labor governments (1997–2010). It has been a significant part of the narrative in Australia as well (Head Citation2016; Cairney Citation2014). Premised on the idea that policy should be driven by research and rigorous evidence, rather than ideology, the evidence-based policy appears to be an obvious goal for any government. Research engagement is one iteration of this evidence-based policy debate (Geddes, Dommett, and Prosser Citation2018). There have been countless studies into the use (or lack thereof) of research in policy (Some examples include Cherney et al. Citation2015; Langer, Tripney, and Gough Citation2016; Nutley, Huw, and Davies Citation2007; Orton et al. Citation2011).

However, despite best intentions, the evidence-based policy remains an elusive and complex ideal. Blame has been laid at the feet of governments for poor implementation or overly ideological decision-making. It has equally been apportioned to academics, seen as poor communicators or focused on abstract and abstruse ideals (Choi et al. Citation2005; Head Citation2015; Newman Citation2014). Solutions tend to fall into one of two overarching camps. The first recommending that academics improve how they translate their work and increase accessibility (Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016; Pearce and Oliver Citation2017; Ingold and Monaghan Citation2016) including discussions around effective boundary work (Hoppe Citation2010; Swedlow Citation2007)or brokerage (Bammer, Michaux, and Sanson Citation2010; Parkhurst Citation2016; Ward, House, and Hamer Citation2009). The second some argue that academics and government should work collaboratively to co-produce knowledge and produce meaningful outputs and outcomes (Western Citation2019; Matthews et al. Citation2018; Shergold Citation2013; Williams Citation2012). This work focuses on these boundaries, including the knowledge translation barriers between researchers and government, with the aim of developing more evidence-based policy. Using a case study of a government – academic research and evaluation partnership in Queensland, we examine the realities and tensions of working in the often competing worlds of government policymaking and academic research.

2. Policy problem

This paper argues that the difference between seeing knowledge coproduction as a tool for research translation as opposed to generating a more collaborative response to policy problems is an important policy concern in itself. Geddes, Dommett, and Prosser (Citation2018) make the point that coproduction is about more than facilitating acceptance of academic research; it also provides an avenue for the creation of knowledge which is of value to both parties. Researchers are encouraged to develop research that is “tailored to or conscious of policy questions and parliamentary requirements” (Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016, 269–70). Western (Citation2019) similarly promotes the value of “effective partnership[s] between researchers and others, oriented to solving practical problems, with a durable relationship between organizations that goes beyond individuals” (21). The use of coproduction, as opposed to a more instrumental process of research translation, is presented as a deeper, more meaningful way of engaging with policy problems (Cairney, Oliver, and Wellstead Citation2016; Haynes et al. Citation2012; Arend Citation2014; Weible et al. Citation2012). It can assist in “building shared understanding, personal trust and relationships that can circumvent usual barriers around the accessibility of research” (Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016, 269). Walter, Davies, and Nutley (Citation2003) state that it can lead to “deep and enduring partnerships” that will facilitate better translation of research to the local context and also presents opportunities for policymakers to discuss risk and implications (60). “Participants also described spin-off benefits, especially the development of enhanced networks, new learning and skills” (2003, 60)

In addition to these proposed benefits, there is also some discussion in the literature about the possible barriers to successful coproduction of knowledge. Flinders, Wood and Cunningham (Citation2016), for example, express that there is a risk that embarking upon coproduction can “create high expectations about the potential outcomes of projects that have self-consciously ‘co-productive’ elements to them; expectations that may be unrealistic” (269). This can be best managed by expectations management. Buick et al. (Citation2016) recommend doing this by establishing a common purpose at the beginning, with shared goals and objectives (2016). They also recommend establishing supportive architecture and regular communication. Part of this is “identify[ing] what success looks like for both parties” (Buick et al. Citation2016, 45).

The management of expectations and early identification of desired outcomes can be challenging, however, given the significant power imbalance between the commissioner of the research – commonly government- and the research partners. Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham (Citation2016) point to the fact that, at the end of the day, “the choices of what information is used, and which policy recommendations are actually implemented rests with the project initiators” (272). Buick et al. (Citation2016) themselves acknowledge that the government may use their ‘veto power’ over the contracts to shape their preferred outcome (Buick et al. Citation2016, 38). The risks inherent in this power imbalance also means, for many researchers, coproduced research can be undervalued in the academic sphere (Swedlow Citation2007). The “pressure to ‘frame’ or ‘interpret’ the research findings in a certain way can be significant” (Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016, 275) and working closely with policymakers can call into question a researcher’s independence. This can lead to the production of separate rather than joint outputs (Amabile et al. Citation2001; Hartley and Benington Citation2000). In practice this may involve government ‘allowing’ researchers to produce academic outputs in addition to the reports and policy documents that are the expected results of the project.

This is important as, increasingly, research impact is an expectation for academic research. In the UK the Research Evaluation Framework increasingly looks to evaluate impact as well as scientific quality (Smith, Ward, and House Citation2011). Researchers are expected to engage in public engagement and knowledge exchange on a much wider scale than only a decade ago (Smith and Bandola-Gill Citation2020). A part of this has included bringing the ‘end users’ of research including governments, industry, philanthropy and civil society in the process. Coproduction rather than one-off consultations and siloed conversations are increasingly seen as necessary ingredients to more effective research translation and impact (Evans and Terrey Citation2016; Blomkamp Citation2018). As Western (Citation2019, 21) argues the ”fundamental goal (for university research today) is to design elements of the research ecosystem to produce outcomes that all participants (policymakers, service deliverers, researchers, civil society organizations and other stakeholders) value”. Consequently, researchers need to listen and build partnerships rather than expecting to talk and be heard by stakeholders, especially the government.

To date, there has been little empirical research which meaningfully explores the practices of knowledge coproduction and whether there are any particular ingredients for success (Geddes, Dommett, and Prosser Citation2018) Some notable exceptions include the work being done by Oliver and colleagues on the challenges of co-production in research more broadly (Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019; Cairney and Oliver Citation2020) and Boaz et al. (Citation2021) on the erosion over time from coproduction to more instrumental knowledge exchange. Buick et al. (Citation2016) are an Australian example, wherein the authors reflect on their own experiences in a co-production partnership between three universities and the Australian Public Service Commission. These bodies of work provide insight into the often competing political, policy and academic expectations the authors experienced throughout the project. What is clear is that coproduction of knowledge is not, in and of itself, a solution to the development of evidence-based policy. It may however represent a valuable tool in the arsenal of researchers wishing to have an impact on policy design and implementation. To continue to build on this body of knowledge, this paper will also explore the practice of coproduction using an insider, auto ethnographic account. The aim of these reflections is to highlight some of the key facilitators and barriers that emerged and provide a more nuanced reflection on whether this approach to research engagement can play a role in the development of better policy.

3. The case

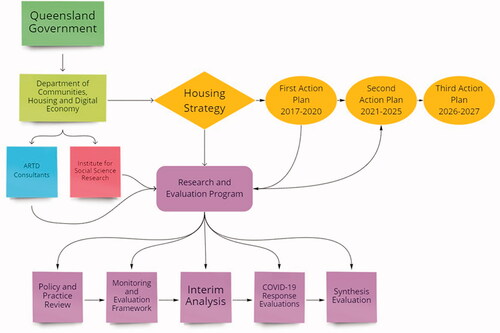

The case this project explores is the Research and Evaluation Program (the R&E Program) of the Queensland Government’s Housing Strategy 2017–2027 (Housing Strategy). In November 2019, the University of Queensland, through the Institute for Social Science Research (ISSR), formed a collaboration with ARTD Consultants to implement the Program (UQ-ARTD). One of the authors of this paper, Professor Tim Reddel, was project lead for the Program, in collaboration with Dr. Emily Verstege of ARTD. Their role was to co-produce and deliver a flexible monitoring and evaluation framework for the Housing Strategy. Professor Reddel received permission for the Department to collect data on the process and practices involved in developing the R&E Program. The results of this insider research form the empirical database for this paper.

The R&E Program is a long-term funded partnership project (defined as a formalized network designed to manage inter-organizational relationships of stakeholders to assess, define and implement necessary action Lewis 2009). This partnership ran from November 2019 to June 2021 between The University of Queensland (UQ) in collaboration with ARTD Consultants and the Queensland Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy (the Department) to support the Housing Strategy’s policy research and evaluation activities.

The Housing Strategy is being operationalized through three action plans, specifying in multi-year installments, what the Government will do over 10 years (2017–2027). The first Action Plan (2017–2020), had a dual focus on economic development and service reform through increasing housing supply and more person-centred service delivery and product offerings. Actions were targeted at providing pathways out of homelessness into stable housing, and from social housing into the private rental market and home ownership.

The Housing Strategy aimed to address long-term policy legacies including housing stress and promoting economic and social participation for disadvantaged people and communities (Hollander Citation1992; Marston Citation2000). This added a degree of policy and political complexity. A key component of the R&E Program was therefore a focus on partnering with officials and key stakeholders to increase the evidence base and build new, collaborative working arrangements with the Department across all aspects of the Housing Strategy ().

The focus on knowledge coproduction is reflected in the key Strategy documents and the agreed project plan between the Department and UQ-ARTD as the following quote from the project plan highlights:

’Our partnership approach will prioritise strong foundations for working together with the Department as well as a future focus on how an ongoing research agenda can realise longer term benefits for Queenslanders. Partnership development activities will continue through 2020, with a sustained emphasis on codesign of a comprehensive research program for the Department’.

The UQ-ARTD team was expected to coproduce three important policy products for the R&E Program. The first was an interim analysis on the progress of the Housing Strategy. The second is a policy and practice review that benchmarked the Housing Strategy against comparable jurisdictions undertaking housing system reform. Finally, a flexible monitoring and evaluation framework for the Housing Strategy. This study details how the R&E program was developed through co-design and co-production with the Department and the UQ-ARTD team. It will include a discussion of the barriers and facilitators to achieving an outcome that created value and supported the development of evidence-based policy. It will do this using an ethnographic insider approach, sharing the reflections of one of the key collaborators on this project.

4. Research approach

Undertaking research as an insider has many advantages, such as ease of access, the opportunity to make positive change in one’s own setting and examine the micro behaviors and processes that influence outcomes. However, it also raises complex ethical and methodological issues arising from undertaking the study from an “insider” perspective and generates debates about the insider/outsider relationship (Atkins and Wallace Citation2012). The “insider” perspective of this study was managed by balancing “distancing” with intensity/engagement during data collection i.e. balancing subjective (emic) with objective (etic) perspectives; understanding and managing the inevitable conflicts and biases; accepting multiple realities from the variety of participants and interests involved in the research and recognizing their positionality (Kanuha Citation2000; Asselin Citation2003). Understanding this positionality was a foundational principle for this research. The lead researcher had significant experience over many years as a senior public official in both the Queensland and Australian public sectors. These roles included senior leadership positions in central agencies and social policy departments from 1991 until 2010 in the Queensland public sector and from 2010 until 2019 in the Australian Public Service. The breadth of this experience provided extensive knowledge of public administration and policy-making processes in Queensland and nationally. While this wide-ranging experience provided important and critical perspectives, it also highlighted his privileged position within the bureaucracy and the policy-making process. In order to avoid the risks of conducting research in a well-known setting, which may lead a researcher to make policy, organizational or personal assumptions and identify themes, issues or problems prematurely without deeper examination the researcher engaged in peer reflection with a coauthor to challenge their assumptions (Orr and Bennett Citation2009). The engagement and questioning approach was designed to enable the researcher to recognize the knowledge gained and to be able to situate it within the broader research–practice gap landscape (Alvesson, Hardy, and Harley Citation2008). This was further supported by the lead researcher working as an “authorized outsider” rather than an official member of the organization. These two strategies were able to address some key challenges for insider research, such as role identity and boundary conflict, questions of confidentiality, managing power relations, and impartiality.

The purpose of the case study was to highlight some of the barriers and facilitators to knowledge coproduction in policy. Three primary sources of data were accessed for this study. First, documentation concerning the case study including official reports and briefings, submissions, evaluations and policy and discussion papers. Second, direct engagement and discussions with key participants (officials and external stakeholders) involved in the case study. Third, and observation of and participation in meetings, interactions between groups and individuals involved in the case study. Where necessary, permission was sought and gained from relevant authorities for access to the official documentation. As Yin (Citation2009) suggests single cases such as the Partnership are appropriate as a test of existing theory and practice. There are some methodological limitations to this research given the subjective nature of a case study approach. However, there is no intention to generalize from the data; rather, we present a case study that both complements previous research and offers alternative experiences. The case study presentation complemented by the key themes presented in the literature review supports the paper’s central purpose of highlighting the practical and systemic barriers and facilitators of effective knowledge coproduction.

5. Discussion

Given that the Government was introducing a new focus for the Housing Strategy, it was agreed that the project required deep and sustained engagement with stakeholders to meet the goal of building an evidence base to effectively drive reform. Indeed, the Department was having discussions with external stakeholders including non-government agencies, advocacy groups and researchers throughout 2017 and 2018 about the opportunities the Housing Strategy presented for a different approach to research and evaluation partnerships that was focused on stakeholder engagement and evidence. While coproduction was not a commonly used term in the Queensland public policy context, working with external expertise to provide a rigorous evidence base that integrated stakeholder engagement was seen by the Department’s senior leadership a key direction to pursue. This was reflected in the Housing Strategy’s First Action Plan’s initiative to establish a Housing and Homelessness Research Alliance to better support targeted research, analysis and evaluation. Ultimately the Research Alliance was discontinued, but the action’s intent was subsumed, and arguably extended by the establishment of the R&E Program with UQ-ARTD in 2019. Rather than a more formal approach, wherein research was a unidirectional input into the policy process, it was agreed to instead undertake a more collaborative approach to the design and production of policy and evaluation.

5.1. Coproduction in practice

Professor Reddel and Dr. Verstege were embedded with the Department for regular periods each week from November 2019 until March 2020 and were able to build relationships, provide practical support and understand not just the policy intent but the real-time experience of departmental officials and stakeholders in implementing the Housing Strategy. Rather than engaging with Departmental officials and stakeholders in formal meetings and events only, it was important that researchers were available and participated directly in policy discussions often in ad hoc and informal settings. These discussions provided opportunities to work through policy design and implementation challenges. One example was the approach to the Housing Strategy’s Aboriginal and Torres Islander Housing Action Plan and its promotion of homeownership in remote communities. Discussions occurred between the research team and departmental officials outside formal workshops and meetings about the implementation status and outcomes of the reforms. This ‘back and forth’ highlighted that understanding and assessing such complex and longstanding policy requires researchers to be open to being challenged about their research-driven assessments and listen to stakeholder views to build a realistic and multi-faceted evidence base.

This practical research and policy approach also included more strategic support for the Department’s submission to the Queensland State Budget process through the Interim Analysis of the Housing Strategy’s First Action Plan, the policy and practice review which showcased back to the Department and stakeholders how the Department’s current and planned activities under the Strategy aligned with trends in housing policy trends in other Australian and international jurisdictions; and highlighting key data gaps and opportunities through an initial data audit of the Department policies and programs. These research products (and the subsequent evaluations of the Department’s COVID-19 responses to the residential rental and homelessness sectors) were key elements of the Department’s stakeholder consultations to inform the development of the Strategy’s Second Action Plan.

This iterative, adaptive and times “messy” story differs from traditional research-policy translation/impact approaches by largely rejecting a quasi-rational policy thinking into which evidence from the researcher can just slot in a predetermined policy product or approach (Smith and Stewart, Citation2017). In this view, research is translated, effectively or otherwise, to a presumed audience that is interested. This is still a commonly used model, even though policy analysis has, for decades, demonstrated that policymaking does not happen in this rational way (Cairney, Oliver, and Wellstead Citation2016). Policymakers and their delivery systems are comprised of a diverse set of institutions and instruments such as complex grant programs and contracts with third parties, direct payments to citizens, regulatory systems and strategic partnerships to design and deliver public goods and services. These systems are characterized by institutional “adhocracy” resulting in confusion, conflict, and ubiquitous turf wars between stakeholders (Parsons Citation1995). It also highlights the importance of understanding the informal side of policymaking, the “work” that happens behind the scenes that facilitate the design and production of policy outcomes. Navigating this complexity is a key challenge for collaborative research and policy projects.

5.2. Navigating the informal side of policymaking

A benefit of the coproduced policy is the ability to participate in informal discussions. This allows the researchers to better navigate stakeholder expectations and determine what policy issues were best to focus on and what was off-limits. Engaging different officials at various organizational levels with responsibilities for policy development, program design and delivery was a central tenet of the UQ-ARTD team’s approach to the R&E Program. What was discovered was a broad spectrum of differing views on key concepts such as “success”, “indicators” and “outcomes”. These challenges were largely able to be addressed through discussions with departmental officials, many of these ad hoc and random. For example, the analysis of the rights and interests of people living in manufactured homes and retirement villages relied on formal and informal discussions with officials and representatives of sector advocacy and peak bodies. These findings, complemented by a review of the Government’s legislative reforms, were highlighted in the interim analysis of the First Action Plan.

This highlights the important role the UQ-ARTD research team played in bridging the policy-research divide while simultaneously traversing the differing organizational perspectives across the Department’s policy, program and service delivery functions. These informal discussions were supported by opportunities to participate in more formal negotiations. The UQ-ARTD research team participated in regular Steering Committee meetings, chaired by the Deputy Director-General, and had an opportunity to brief the Minister for Housing and Public Works and the Ministerial Housing Council of key external stakeholders several times. This enabled direct engagement with senior officials to debate, discuss, test, and authorize key directions for the program; and requiring distributed governance across the program’s eco-system of the department and sector stakeholders (or at the very least the department). Departmental officials with different functional responsibilities at delivery, program, or policy levels or at different levels of seniority all had distinctive perspectives on the key priorities for the Action Plan and R&E Program. Similarly, external stakeholders including peak advocacy bodies and service providers had diverse views. The Program’s Steering Committee, weekly “catch ups” with key officials, regular engagement with external stakeholders and formal workshops, while not perfectly “joined up” provided a platform to navigate these “voices” together. It also highlighted the importance of finding ways to actively work through issues and problems with stakeholders before decisions were made and reports delivered.

A further benefit of the co-production approach was the ability to adapt when confronted by external pressures. Like many projects, this project was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This required the team to pivot to a new focus from mid-2020, including reviewing and supporting the Department’s urgent regulatory and service responses. This resulted in transitioning away from new research for the Housing Strategy to the development of post-implementation reviews of the Department’s responses to COVID-19 in the residential rental tenancies and homelessness sectors. What this meant was that research activities were realigned with emerging priorities and strategic directions. The UQ-ARTD research team and the Department were able to renegotiate and reassess what was a valuable outcome for the collaboration. Changes in policy direction are common, even if not as significant in most cases as with COVID-19. This is not to say that the reassessment of desired outcomes was a straightforward process and it required significant institutional knowledge on behalf of the UQ-ARTD research team. This was facilitated by the extensive experience and understanding of public policy held within the UQ ARTD team. Professor Reddel’s previous experience as a senior official in the Queensland and Australian public service provided insights and importantly critical empathy for the inevitable changes in expectations delays and frustrations with the overall process. Dr. Verstege’s position as an experienced commercial consultant understood the importance of delivering on the agreed priorities and products of the Program. Given the inevitable “back and forth” process of negotiation, the ability to understand and empathize with the demands of the policy environment was essential.

The ability of the UQ-ARTD research team to negotiate the outcomes of the partnership is not to say that the process was not challenging and at times confusing, exacerbated by both departmental officials and the UQ-ARTD team working remotely with limited direct face to face contact. In addition, delays due to the Queensland State election in early October 2020 and associated machinery of government changes for the Department (from Housing and Public Works to Communities, Housing and Digital Economy), State Budget in early December 2020 and the late December 2020–January 2021 shut down period meant that the data gathering and policy engagement was more sporadic and difficult especially in working with officials and some external stakeholders. What it meant was that this was not a fatal blow?

A final, important component was that the UQ-ARTD research team had limited requirements outside of the partnership. In many cases of policy/research collaboration, there is also a need for academic partners to be able to publish results in academic journals. While this was not a formal element of this project, the Department has been supportive of ISSR and ARTD communicating key findings of the Program and lessons from the partnership.Footnote1 This allows the academic staff working within ISSR a more flexible “identity” than may be achievable in more traditional research environments within the university (Henkel Citation2005).

6. New directions and recommendations for improvement

In conclusion, we suggest the case presented in this paper points to some new directions and recommendations for understanding knowledge coproduction in policy. First, this case highlights that successful policy impact is not just about achieving narrowly defined outcomes, but also about working with stakeholders directly and acting where needed, as an external expert and “critical friend” to progress actions demonstrate lessons learned and the range of possible options to achieve often diverse outcomes between stakeholders (McConnell Citation2010). Coproducing the R&E Program required focused, realistic and challenging conversations between different stakeholders within the Department. The fundamental method was spending dedicated time one-on-one with staff at all levels, talking to external stakeholders, conducting formal workshops, ad-hoc discussions in combination with the analysis of available data and evidence. This approach demonstrated that the research team wanted to engage, understand the Department’s business, and could add value. It also helped to unseat any preconceived assumptions based on a research agenda or an assumed understanding of current policy issues and political context.

The significant cost of participation for researchers is also an important challenge to coproduction. Those who lack practical knowledge and experience in the policy process will likely struggle to operate in this environment. The commonality is important between the policymakers and the researcher as, when these were not present, “policy officials reported a much greater likelihood of tension, conflict and, ultimately, the demise of research collaborations” (Arend Citation2014, 626–27). Clearly, there are knowledge requirements for working with the government or any other external body to help researchers understand how to navigate this environment. Different parts of government also serve different purposes, a departmental evaluation is likely to be very different from submission to an Inquiry or collaborating on a White Paper. Some arenas are more political, others more evidence-focused. Different departments themselves may hold very different relationships with evidence and hierarchies of evidence. We would argue that this case shows that empathy with the inherent changeability of the political environment is a key requirement for meaningful knowledge coproduction for policy. The disruptive nature of changing policies, the demands of budgets and elections, and the turnover of public service staff makes this attribute critical (Martin, Currie, and Lockett Citation2011). The decision making process can be significantly influenced by “factors such as the current political environment, the capacity of the government to implement unpopular decisions and the government’s desire to “be seen” to be addressing an issue quickly” (Arend Citation2014, 623).

Finally, the costs for researchers interested in engaging in coproduction also need to be understood as differing across the career life cycle and institutional demands of the researcher. Consultants and senior, tenured academics operate from a very different base than those of early or even mid-career researchers. The ability to adapt to shifting demands, leaving incomplete and often unpublishable research, is likely to have a far more significant impact on those still establishing themselves in research. Acknowledging this is critical, particularly given the ongoing focus on research impact that is emerging in government funding and within academic institutions. As the impact agenda continues to grow, in Australian research and beyond, finding ways to recognize and accommodate these different needs will influence how projects are structured and training provided moving forward.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brad Mccoy, Emily Verstege and Dave Porter for their helpful comments and conversations that have shaped this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ISSR and ARTD have published key updates and lessons learnt from the R&E program through their respective communication channels including newsletters and annual reports.

References

- Alvesson, Mats, Cynthia Hardy, and Bill Harley. 2008. “Reflecting on Reflexivity: Reflexive Textual Practices in Organization and Management Theory.” Journal of Management Studies 45 (3): 480–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00765.x.

- Atkins, L., and S. Wallace. 2012. “Insider Research.” In Qualitative Research in Education. Research Methods in Education, 47–64. London: SAGE.

- Amabile, Teresa M., Chelley Patterson, Jennifer Mueller, Tom Wojcik, Paul W. Odomirok, Mel Marsh, and Steven J. Kramer. 2001. “Academic-Practitioner Collaboration in Management Research: A Case of Cross-Profession Collaboration.” Academy of Management Journal 44 (2): 418–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/3069464.

- Arend, Jenny van der. 2014. “Bridging the Research/Policy Gap: Policy Officials’ Perspectives on the Barriers and Facilitators to Effective Links between Academic and Policy Worlds.” Policy Studies 35 (6): 611–630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2014.971731.

- Ashcraft, Laura Ellen, Deirdre A. Quinn, and Ross C. Brownson. 2020. “Strategies for Effective Dissemination of Research to United States Policymakers: A Systematic Review.” Implementation Science 15 (1): 89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01046-3.

- Asselin, Marilyn E. 2003. “Insider Research: Issues to Consider When Doing Qualitative Research in your Own Setting.” Journal for Nurses in Staff Development19 (2): 99–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00124645-200303000-00008.

- Bammer, G., A. Michaux, and A. Sanson. 2010. Bridging the “Know-Do” Gap: Knowledge Brokering to Improve Child Wellbeing. Canberra, Australia: ANU E Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=IdzUvb9EswwC.

- Blomkamp, E. 2018. “The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 77 (4): 729–743. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12310.

- Boaz, A., R. Borst, M. Kok, and A. O’Shea. 2021. “How Far Does an Emphasis on Stakeholder Engagement and Co-Production in Research Present a Threat to Academic Identity and Autonomy? A Prospective Study across Five European Countries.” Research Evaluation. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvab013.

- Buick, Fiona, Deborah Blackman, Janine O’Flynn, Michael O'Donnell, and Damian West. 2016. “Effective Practitioner-Scholar Relationships: Lessons from a Coproduction Partnership.” Public Administration Review 76 (1): 35–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12481.

- Cairney, Paul. 2014. “Evidence-Based Policymaking: If You Want to Inject More Science into Policymaking You Need to Know the Science of Policymaking.” Political Studies Association Annual Conference, Manchester. Accessed 16 November 2014. https://paulcairney.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/cairney-psa-2014-ebpm-5-3-14.pdf

- Cairney, Paul, and Kathryn Oliver. 2020. “How Should Academics Engage in Policymaking to Achieve Impact?” Political Studies Review 18 (2): 228–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807714.

- Cairney, Paul, Kathryn Oliver, and Adam Wellstead. 2016. “To Bridge the Divide between Evidence and Policy: Reduce Ambiguity as Much as Uncertainty.” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 399–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12555.

- Cherney, Adrian, Brian Head, Jenny Povey, Michele Ferguson, and Paul Boreham. 2015. “Use of Academic Social Research by Public Officials: Exploring Preferences and Constraints That Impact on Research Use.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 11 (2): 169–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X14138926450067.

- Choi, Bernard C. K., Tikki Pang, Vivian Lin, Pekka Puska, Gregory Sherman, Michael Goddard, Michael J. Ackland, et al. 2005. “Can Scientists and Policy Makers Work Together?” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59 (8): 632–637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.031765.

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2019. Our Public Service, Our Future: Independent Review of the Australian Public Service. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth.

- Evans, M., and N. Terrey. 2016. “Co-Design with Citizens and Stakeholders.” In Evidence-Based Policy Making in the Social Sciences: Methods That Matter, edited by G. Stoker and M. Evans, 243–262. London: Palgrave.

- Flinders, Matthew, Matthew Wood, and Malaika Cunningham. 2016. “The Politics of Co-Production: Risks, Limits and Pollution.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 12 (2): 261–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14412037949967.

- Geddes, Marc, Katharine Dommett, and Brenton Prosser. 2018. “A Recipe for Impact? Exploring Knowledge Requirements in the UK Parliament and Beyond.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 14 (2): 259–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/174426417X14945838375115.

- Hartley, Jean, and John Benington. 2000. “Co-Research: A New Methodology for New Times.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 9 (4): 463–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320050203085.

- Haynes, A., Gemma E. Derrick, Sally Redman, Wayne D. Hall, James A. Gillespie, Simon Chapman, and Heidi Sturk. 2012. “Identifying Trustworthy Experts: How Do Policymakers Find and Assess Public Health Researchers Worth Consulting or Collaborating with?” PLOS One 7 (3): e32665. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032665.

- Head, Brian. 2015. “Relationships between Policy Academics and Public Servants: Learning at a Distance?” Australian Journal of Public Administration 74 (1): 5–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12133.

- Head, Brian. 2016. “Toward More ‘Evidence-Informed’ Policy Making?” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 472–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12475.

- Henkel, Mary. 2005. “Academic Identity and Autonomy in a Changing Policy Environment.” Higher Education 49 (1–2): 155–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2919-1.

- Hollander, R. 1992. “Negotiating Housing Policy: The Queensland Housing Commission and Federal, State and Local Government.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 51 (3): 342–353. https://doiorg.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/10.1111/j.1467-8500.1992.tb02620.x. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.1992.tb02620.x.

- Hoppe, Robert. 2010. “From ‘Knowledge Use’ towards ‘Boundary Work’: Sketch of an Emerging New Agenda for Inquiry into Science-Policy Interaction.” In Knowledge Democracy: Consequences for Science, Politics, and Media, edited by Roeland J in ’t Veld. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Ingold, Jo, and Mark Monaghan. 2016. “Evidence Translation: An Exploration of Policy Makers’ Use of Evidence.” Policy & Politics 44 (2): 171–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/147084414X13988707323088.

- Kanuha, Valli Kalei. 2000. “Being’ Native versus ‘Going Native’: Conducting Social Work Research as an Insider - Document - Gale Academic OneFile.” Social Work 45 (5): 439–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/45.5.439.

- Langer, Laurenz, Janice Tripney, and David Gough. 2016. The Science of Using Science: Researching the Use of Research Evidence in Decision-Making. London: Social Science Research Unit EPPI-Centre UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

- Loeffler, Elke. 2021. “The Future of Co-Production: Policies, Strategies and Research Needs.” In Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes, 395–427. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55509-2_7.

- Marston, Greg. 2000. “Metaphor, Morality and Myth: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Public Housing Policy in Queensland.” Critical Social Policy 20 (3): 349–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830002000305.

- Martin, Graham, Graeme Currie, and Andy Lockett. 2011. “Prospects for Knowledge Exchange in Health Policy and Management: Institutional and Epistemic Boundaries.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 16 (4): 211–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010132.

- Matthews, Peter, Rutherfoord Robert, Connelly Steve, Richardson Liz, Durose Catherine, and Vanderhoven Dave. 2018. “Everyday Stories of Impact: Interpreting Knowledge Exchange in the Contemporary University.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 14 (4): 665–682. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/174426417X14982110094140.

- McConnell, Allan. 2010. Understanding Policy Success: Rethinking Public Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Newman, Joshua. 2014. “Revisiting the ‘Two Communities’ Metaphor of Research Utilisation.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 27 (7): 614–627. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-04-2014-0056.

- Newman, Joshua. 2020. “Increasing the Ability of Government Agencies to Undertake Evidence-Informed Policymaking.” Evidence Base 2: 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.21307/eb-2020-005.

- Nutley, Isabel, Sandra M., Walter Huw, and T. O. Davies. 2007. Using Evidence: How Research Can Inform Public Services. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Oliver, Kathryn, Anita Kothari, and Nicholas Mays. 2019. “The Dark Side of Coproduction: Do the Costs Outweigh the Benefits for Health Research?” Health Research Policy and Systems 17 (1): 33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3.

- Orr, Kevin, and Mike Bennett. 2009. “Reflexivity in the Co-Production of Academic-Practitioner Research.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 4 (1): 85–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640910951462.

- Orton, L., F. Lloyd-Williams, D. Taylor-Robinson, M. O’Flaherty, and S. Capewell. 2011. “The Use of Research Evidence in Public Health Decision Making Processes: Systematic Review.” PLOS One 6 (7): e21704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021704.

- Parkhurst, Justin. 2016. The Politics of Evidence: From Evidence-Based Policy to the Good Governance of Evidence. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Parsons, Wayne. 1995. Public Policy: An Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Policy Analysis. Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar Pub.

- Pearce, Warren, and Kathryn Oliver. 2017. “Three Lessons from Evidence-Based Medicine and Policy: Increase Transparency, Balance Inputs and Understand Power.” Palgrave Communications 3: 43.

- Shergold, Peter. 2013. “Governing through Collaboration.” In Collaborative Governance: A New Era of Public Policy in Australia?, edited by Janine O’Flynn and John Wanna, 13-22, Canberra, Australia, ANU Press.

- Smith, Katherine, and Justyna Bandola-Gill. 2020. The Impact Agenda: Controversies, Consequences and Challenges. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Smith, K. E., and E. Stewart. 2017. “We Need to Talk about Impact: Why Social Policy Academics Need to Engage with the UK's Research Impact Agenda.” Journal of Social Policy 46 (1): 109–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000283.

- Smith, Simon, Vicky Ward, and Allan House. 2011. “Impact’ in the Proposals for the UK’s Research Excellence Framework: Shifting the Boundaries of Academic Autonomy.” Research Policy 40 (10): 1369–1379. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.026.

- Swedlow, Brendon. 2007. “Using the Boundaries of Science to Do Boundary-Work among Scientists: Pollution and Purity Claims.” Science and Public Policy 34 (9): 633–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/030234207X264953.

- Walter, Isabel, Huw Davies, and Sandra Nutley. 2003. “Increasing Research Impact through Partnerships: Evidence from outside Health Care.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 8 (2_suppl): 58–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/135581903322405180.

- Ward, V., A. House, and S. Hamer. 2009. “Knowledge Brokering: Exploring the Process of Transferring Knowledge into Action.” BMC Health Services Research 9 (1): 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-12.

- Ward, Vicky, Tricia Tooman, Benet Reid, Huw Davies, and Martin Marshall. 2021. “Embedding Researchers into Organisations: A Study of the Features of Embedded Research Initiatives.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice ) 1–22.

- Weible, Christopher M., Tanya Heikkila, Peter deLeon, and Paul A. Sabatier. 2012. “Understanding and Influencing the Policy Process.” Policy Sciences 45 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-011-9143-5.

- Western, Mark. 2019. “How to Increase the Relevance and Use of Social and Behavioral Science: Lessons for Policy-Makers, Researchers and Others.” Justice Evaluation Journal 2 (1): 18–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24751979.2019.1600381.

- Williams, Paul. 2012. Collaboration in Public Policy and Practice: Perspectives on Boundary Spanners. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Yin, R. 2009. Case Study Research and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Inc.