ABSTRACT

Against the backdrop of a rapidly changing security environment in East Asia, regional actors have seen a surge in “nuclear anxiety”. Worries among citizens of US allies and partners about rising nuclear threats and nuclear proliferation risks critically shape US foreign policy in East Asia. This paper thus asks: What drives nuclear anxiety in East Asia? And how can the United States most effectively resolve it? We situate nuclear anxiety in the dynamics of abandonment and entrapment that exist between allied states, as well as in the unique regional security structure, or the hub-and-spoke system in East Asia. To better understand the implications of nuclear anxiety on regional nuclear policy, we analyze the results of an original survey conducted in June 2023 across Washington’s five allies and partners in East Asia: Australia, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The survey results suggest the presence of the dynamics of both nuclear entrapment and abandonment among these regional actors, as well as mixed interests in indigenous nuclear programs. In addition, we demonstrate how citizens of East Asia evaluate possible policy options that could help Washington mitigate regional nuclear anxiety.

Introduction

In East Asia, nuclear deterrence is one of the defining axes of regional polarization (Frühling and O’Neil Citation2021; Hughes Citation2007).Footnote1 With China’s and North Korea’s growing nuclear arsenals challenging regional stability, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Australia largely rely on U.S. nuclear assurances for protection. At the same time, they must navigate complex economic and political relationships with the United States, China, and each other. These states face a difficult dilemma in attempting to manage growing “nuclear anxiety” among their publics (Tsunashima Citation2023). In this paper, we use the term “nuclear anxiety” in reference to how citizens in East Asian states understand a complex set of nuclear fears.Footnote2 These include security threats stemming from multiple regional adversaries, worries about allied nuclear proliferation,Footnote3 and concerns about (in)adequately managing the nuclear dimensions of their US security guarantees. We aim to investigate how the East Asian publics prefer to balance contrasting sets of priorities as they seek both strategic and psychological security in their emerging threat environment.

Because US allies and partners in East Asia do not possess their own nuclear weapons and thus cannot face nuclear threats with their own arsenals, a significant portion of their nuclear anxiety derives from principal-agent problems inherent in managing their nuclear relationship with the United States. These states face challenges related to the dynamics of both abandonment and entrapment. In this paper, we focus specifically on nuclear abandonment and nuclear entrapment, such that the former indicates concerns about being abandoned by the United States in the face of threats from nuclear adversaries, such as China and North Korea, whereas the latter implies being entrapped into an unwanted nuclear conflict if Washington escalates against these regional competitors.Footnote4

The current literature argues concerns about nuclear abandonment are a primary driver of proliferation, such that allied states might prefer developing their own nuclear weapons if they cannot be reassured their guarantor will follow through on its defense commitments (Debs and Monteiro Citation2016; Reiter Citation2014). Several scholars have argued such concerns are critical in South Korea’s growing interest in nuclear proliferation (M. Kim Citation2023; Ko Citation2019; Son and Yim Citation2021; Yeo Citation2023). In contrast, a growing body of scholarship suggests concerns about entrapment can also motivate nuclear proliferation and points to South Korean anxiety about whether the United States will be able to sufficiently exercise nuclear restraint (Justwan and Berejikian Citation2023; Lee Citation2023; Mount Citation2023; Sukin Citation2020; Sukin and Dalton Citation2021).Footnote5

Thus, this paper asks: What drives nuclear anxiety in East Asia? And how can the United States most effectively resolve it? To study this, we conducted a survey in June 2023 in Australia, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. We asked publics here about their perceptions of regional nuclear threats and explored how they seek reassurance in this threat environment. We argue both abandonment and entrapment concerns shape public preferences, and US policy responses to nuclear anxiety should take both kinds of pressures into account.

This paper proceeds as follows. First, the paper situates nuclear anxiety in the alliance politics literature, demonstrating that concerns about both abandonment and entrapment can undermine feelings of nuclear security. Second, we outline our use of survey experiments to study this topic. Third, we review the survey results and explain how nuclear anxiety in East Asia reflects both abandonment and entrapment considerations. Fourth, we address the potential consequences of these anxieties, exploring public attitudes about indigenous nuclear proliferation as well as the re-deployment of US nuclear weapons to East Asia. In addition, we assess intra-regional dynamics, investigating the effects of South Korean interest in nuclear proliferation on other East Asian states. Fifth, we explore how citizens of US allies and partners in East Asia seek reassurance from the United States. Finally, we synthesize these results and argue that US efforts to resolve regional nuclear security concerns should walk a fine line between resolve and restraint.

Between Abandonment and Entrapment

Snyder (Citation1984, Citation1997) describes the abandonment-entrapment dilemma as an intractable feature of alliances. Weaker states within alliances worry about their guarantor defecting from the terms of their alliance commitments.Footnote6 These defections can occur in various degrees and forms, such as exiting an alliance treaty, failing to implement commitments, or not providing support during adverse contingencies.Footnote7

On the other hand, strong allies worry about entrapment, i.e. “being dragged into a conflict over an ally’s interests that one does not share, or shares only partially” (Snyder Citation1984, 467). This alliance hazard has also been conceptualized as “entanglement” (T. Kim Citation2011, 355), a particularly risky form of the broader “entrapment” defined as “a form of undesirable entanglement in which the entangling state adopts a risky or offensive policy not specified in the alliance agreement”. Both Snyder’s and Kim’s definitions center on alliance actions occurring outside of agreed concerns.Footnote8 Sukin (Citation2020) further expands the conception of entrapment to include reckless behavior over shared interests, arguing that states might worry their allies will adopt overly offensive postures as specified within their alliance agreements. For example, State A might be concerned State B would respond to a common adversary’s aggression with nuclear use – as the guarantee specifically designed to allow – but will do so under conditions in which State A would prefer a conventional response. Together, these concepts of entrapment comprehensively capture a variety of the fears both Washington and its partners may have about being brought into unintended crises or wars as a result of their relationships.Footnote9

Scholars have explored the extent to which abandonment and entrapment inform US foreign policy. For example, Gholz et al (Citation1997) and Posen (Citation2014) argue that the case for a strategy of restraint emerges because US commitments, such as those in East Asia, risk costly entrapment.Footnote10 Against the strategy of restraint, Kim (Citation2011) and Beckley (Citation2015) argue fears of entrapment are overblown: that there were just a few historical cases where Washington was entrapped due to allies’ behavior. While powerful allies are thought to primarily worry about entrapment, weaker allies are thought to prioritize avoiding abandonment. In partnerships, abandonment concerns may be further heightened, because there is no binding security guarantee.Footnote11

IR scholars have pointed to the role of East Asia’s regional alliance structure in furthering this dynamic. In the case of East Asia, the predominant form of alliance has been the hub-and-spoke system, where the United States established bilateral partnerships with Australia (1951), Japan (1951), South Korea (1954), Taiwan (1954), and others, while these states formed lesser degree of partnerships with each other (Cha Citation2011; Ito Citation2003).Footnote12 The creation of the hub-and-spoke system can be explained by both Washington and its allies’ perspectives. From the US view, Cha (Citation2009) points to Washington’s powerplay rationale to explain this structure, arguing Washington “managed” the entrapment problem by adopting an asymmetric structure. From Washington’s allies’ perspective, Cha (Citation1999, Citation2000) demonstrates how historical animosity plays a role in preventing Washington’s East Asian partners from forming a fully-fledged multilateral alliance. Izumikawa (Citation2020) highlights the active role of Washington’s partners in strengthening their bilateral security relationships with the United States, inadvertently putting less value on their relationships with each other.

In relation to the alliance dynamics, this regional structure leads to the prioritization of abandonment in the scholarly works on the US East Asian network. For example, Reiter (Citation2014, 77) argues “smaller states in bilateral partnerships with the United States, like South Korea … and Taiwan, are less likely to fear entrapment” because the hub-and-spoke shape of the US network in East Asia means any individual state is less likely to be entrapped in another spoke’s conflict than if there were true multilateral alliances.Footnote13 With this reasoning, Reiter and others focus on East Asian states’ efforts to avoid abandonment and downgrade the possibility they might maintain entrapment concerns.

While this may be persuasive under the traditional conceptualization of entrapment – whereby it primarily entails a risk of conflict over non-shared interests – an expanded view of entrapment accounting for risky behavior within the confines of an agreed-upon partnership re-introduces the possibility of entrapment concerns even in strictly bilateral settings.Furthermore, extended nuclear deterrence makes the issues of abandonment and entrapment particularly pressing (Schelling Citation1966). This is because the destructive power of nuclear weapons magnifies the potential costs of being abandoned or entangled for both the United States and its global partners.Footnote14

Regarding alliance dynamics and nuclear deterrence in East Asia, Lanoszka (Citation2018) explores the role of abandonment threats in the reversal of nuclear programs in Japan and South Korea, among others. Gerzhoy (Citation2015) demonstrates the importance of abandonment concerns in West Germany’s nuclear reversal. Reiter (Citation2014) argues states with high abandonment fears, such as those without credible security commitments, may develop their own nuclear weapons. Debs and Monteiro (Citation2016) highlight that states under a nuclear umbrella may still have abandonment fears that drive them to develop nuclear weapons.

While these strands of literature have focused on how abandonment can drive interest in nuclear proliferation, Sukin (Citation2020) argues entrapment has similar effects. In particular, Sukin finds that the high credibility of Washington’s nuclear guarantee can paradoxically increase Seoul’s fear of entrapment and thus reinforce South Koreans’ support for nuclear proliferation. Other work has similarly pointed to the presence of entrapment concerns in South Korea, despite its bilateral alliance structure with the United States, and linked these to Seoul’s interest in nuclear proliferation (Lee Citation2023; Mount Citation2023; Sukin and Dalton Citation2021).

Recent geopolitical changes have highlighted ballooning nuclear anxiety in East Asia and increased public demand for major policy shifts on nuclear questions. For example, strong interest in nuclear proliferation and/or the re-deployment of US nuclear weapons to South Korea marks a shift in regional nuclear dynamics in response to the growing nuclear threats faced by Seoul. South Korea hosted American nuclear weapons from 1958 to 1991, during which the Park Chung-hee administration in the 1970s sought to develop its own nuclear weapons (Frühling and O’Neil Citation2021). Over the past several years, an emergent continent of policymakers has advocated for possessing indigenous nuclear weapons, with this policy now favored by more than two-thirds of the country (Dalton, Friedhoff, and Kim Citation2022). Recent commentary has emphasized how alliance dynamics shape these preferences, pointing to Washington’s untrustworthy extended deterrence and security commitments and adverse lessons drawn from the Ukraine War (M. Kim Citation2023; Brewer, Dalton, and Jones Citation2023; C.-I. Moon and Shin Citation2023; Von Hippel Citation2023). In October 2023, for instance, experts in Seoul and Washington even recommended redeploying 100 tactical nuclear weapons on South Korea’s soil (Bennett et al. Citation2023).

Even in Japan, a long-standing stalwart of the anti-nuclear movement, alliance concerns have contributed to warming attitudes about nuclear proliferation (Cheng et al. Citation2023; Machida Citation2022; Nishida Citation2023). In Taiwan, too, there is renewed interest in nuclear assurances. The United States withdrew its nuclear weapons from Taiwan in 1988 (Albright and Stricker Citation2018), but maintained its security assurances. Taiwanese expectations of the US commitment are strong (Rich, Banerjee, and Tkach Citation2023), and some experts have encouraged the redeployment of nuclear weapons on Taiwan’s soil (Codevilla Citation2021).

The AUKUS deal in Australia, in which the United States and the United Kingdom committed to providing Australia with the nuclear propulsion technology needed to power a nuclear submarine, marked a significant shift in Australia’s nuclear approach. The AUKUS deal raised concerns among many global and regional actors about the consequences of the spread of nuclear technology. For example, Indonesian experts expressed concerns about the implications for regional security, especially in relation to stability in the South China Sea (Liliansa Citation2023; Ningsih Citation2022; Nurfauzi, Lampita, and Rizky Mahendra Citation2022).Footnote15 Some experts worried the deal would undermine the NPT. China expressed particularly strong concerns, pointing to possible nuclear proliferation risks. While the initial surge of worries that the deal portended Australian nuclear weapons development has largely passed, some experts remain wary that nonproliferation controls in the pact have been insufficiently implemented (Dalton and Levite Citation2023). Others suggest the concerns could be perennial, as Australia’s fear of abandonment – which played a role in the inception of AUKUS (L. L. Cox, Cooper, and O’Connor Citation2023) – must continuously be managed.

In this paper, we explore the growing pattern of regional interest in nuclear policy, highlighting the forces of abandonment and entrapment in shaping an increasingly tense and complex nuclear security environment. In doing so, we seek to explore and explain East Asian citizens’ interests in nuclear weapons development and the re-deployment of US nuclear weapons to East Asia. We address how these citizens evaluate recommendations for US nuclear policy.

Methodology

To explore regional attitudes about nuclear policy, we focus on the phenomenon of public nuclear anxiety, exploring how citizens across East Asia view their nuclear threat environment and investigate their priorities and preferences when it comes to handling the challenges of that environment. In doing so, we align with a growing body of literature exploring the causes and consequences of public attitudes about nuclear proliferation, re-deployment, and posture in East Asia.Footnote16 To do so, the project analyses the results of a survey experiment conducted in June 2023 across five states in East Asia.

displays the distribution of respondents included in the survey.Footnote17 In each state, we capture a representative sample of the population, using quotas on respondents’ age and gender. Scholarship has found that quota-based representative samples compare favorably to other collection strategies for survey data.Footnote18 Gender and age quotas are standard in the survey literature in part because of their strong correlations with political demographics and other shaping worldviews. In addition, quotas, as opposed to are a more economical sampling method and correct for the under-representation of male and older respondents that can occur when using internet or telephone equal probability random sampling.Footnote19 Our sample includes significant variation on features other than age and gender, such as education, income, veteran status, and policy experience.Footnote20 Our respondents are also fairly knowledgeable about foreign policy, including nuclear issues.Footnote21

Table 1. Geographical breakdown of the survey sample.

Although the states in our sample do not represent the full panoply of US allies and partners in the region, they include an important sample of this broader landscape. Our dataset covers the US three tightest and most powerful treaty allies in the region: South Korea, Japan, and Australia. In addition, we study nuclear attitudes among the Taiwanese public. Although the United States has no formal security guarantee to Taiwan, it has repeatedly offered security assurances, and the US-Taiwan relationship is often thought critical to regional stability, with conflict contingencies involving Chinese claims over Taiwan featuring heavily in assessments of regional security. Finally, our sample includes Indonesia as an example of a US partner country without a US guarantee and with no explicit US assurances; this inclusion therefore allows us to explore how the alliance and partnership dynamics at the center of this study depart from the myriad security considerations that might influence the preferences and behavior of regional states lying outside of the US network.

In the following section, we review several descriptive measures of public attitudes about nuclear security. As with all surveys, these measures are imperfect. They cannot fully replicate real-world information environments. Nevertheless, they provide initial intuition for how citizens of US allies and partners are thinking about key nuclear issues. These measures offer only a snapshot of public attitudes, albeit at an important moment in time – when the salience of nuclear threats is especially high, and the United States and its partners are actively working to establish a new equilibrium. In this context, public opinion can potentially shape a set of viable policy options. Just as South Korean interest in proliferation has pushed a nuclear conversation to the national mainstage, public preferences on myriad nuclear policies around the region have – in the current political environment – the potential to become highly salient and to thereby influence national and international dialogues.

Assessing Nuclear Abandonment and Entrapment Fears

To evaluate public assessments of US credibility, we asked respondents to imagine how the United States would respond if there were a nuclear attack on their country. While the abandonment literature suggests respondents should be most worried that the United States would not step up in their defense, the entrapment approach instead predicts worries that the United States would, in fact, do so – to serious consequences.

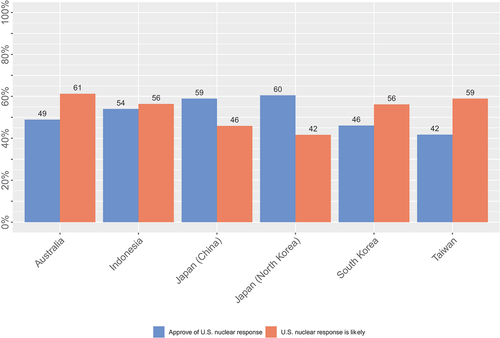

We ask respondents about how likely they find US nuclear use, inquiring: “How likely or unlikely is it that the United States would use nuclear weapons in response to … China/North Korea attacking your country with nuclear weapons?” This allows us to assess the perceived probability that the United States follows through on its defense commitments. As shown in , in every state under study except Japan, a majority of respondents anticipated a US nuclear response to the attack against their homeland.Footnote22 With the exception of Tokyo, we find relative confidence in the US guarantee and only minority concerns about nuclear abandonment.

In addition, we asked respondents if they would approve of such a response, asking “Would you approve or disapprove of the United States using nuclear weapons in response to … China/North Korea attacking your country with nuclear weapons?”Footnote23 This question departs from the traditional approach taken by studies of alliance strength and credibility – its inclusion suggests that ally reassurance should be conceptualized not just as a question of whether an ally would come to one’s aid, but also whether aid, in that specific circumstance, is desired. It thus reflects an understanding of alliances and partnerships that prioritizes agreement between states’ policy preferences and risk tolerance. It suggests entrapment should be considered a viable concern for both strong and weak partners, in multilateral and hub-and-spoke arrangements.

The reactions to this question ranged from 42% of Taiwanese respondents approving of US nuclear retaliation against China to 60% of Japanese respondents approving of US nuclear use against North Korea. This suggests there is, indeed, a notable subset of the public that prefers to avoid nuclear escalation – even in an extremely dire security situation. These respondents may believe the United States would use nuclear weapons in their country’s defense – but their distaste for this policy option means they privilege entrapment concerns over abandonment ones. The questions do not provide specific information about, for example, the number of weapons that would be used in an attack or their targets. It is possible that respondents’ preferences could reflect different interpretations of what a nuclear attack could mean.

Concerns about nuclear escalation could be linked to the nuclear taboo and other moral logics. If respondents view the use of nuclear weapons as unacceptable, this may accelerate concerns about being dragged into nuclear conflict. Indeed, Sukin (Citation2020) argues that the nuclear taboo and an aversion to nuclear use is strongest among those who fear entrapment in a US-led nuclear conflict. However, we find relatively strong support for the use of nuclear weapons in this survey. These findings are especially curious in Japan, where a long-standing moral opprobrium to nuclear weapons exists. Indeed, we find that 85% of Japanese respondents say that the use of nuclear weapons cannot be morally justified – and yet our findings show fairly strong support among Japanese respondents for the use of nuclear weapons.

demonstrates that the dynamics of both nuclear entrapment and nuclear abandonment are present in minds of citizens of US allies and partners in East Asia. These results show that confidence in the reliability of US nuclear security guarantee faces significant regional variation. In addition, we find that many US partners appear concerned about nuclear escalation. They believe the United States is likely to use nuclear weapons in response to a nuclear attack on their country, but they do not necessarily support this option.

The extreme consequences of unwanted nuclear use may cast a shadow over the management of relations with the United States (Sukin Citation2020). For example, we find that 61% of Australians were confident in the US nuclear security guarantee, but just 49% of respondents would want that guarantee to be activated in the event of a nuclear conflict. In South Korea, Taiwan, and Indonesia, fewer respondents approved of a hypothetical US nuclear response to an attack on their country than believed the United States would enact such a response.

In contrast, respondents in Japan show strong fears of nuclear abandonment. These respondents were more likely to approve of US nuclear use against either China or North Korea than they were to have confidence that the United States would actually leverage its nuclear arsenal if Japan were attacked with nuclear weapons by either adversary. Japan’s comparatively hard-line approach to nuclear use and prioritization of abandonment over entrapment could be puzzling given the strong US-Japan nuclear security guarantee and defence relationship.Footnote24 These results also contradict findings from Allison, Herzog, and Ko (Citation2022) that only a small percent of the Japanese public would support nuclear retaliation should Pyongyang attack Nagoya with nuclear weapons. This discrepancy can perhaps be explained by a few factors, including the different scopes of destruction (country vs city) and the rapidly changing security environment in the region between 2023 when our survey was conducted and 2018 when Allison et al. conducted their survey. Japan may now face more significant security concerns, making abandonment a much more serious threat.

US nuclear security assurances continue to be a cornerstone of the US network in East Asia. Confidence in the US nuclear security guarantee is currently high, as a majority of the public Australia, Indonesia, South Korea, and Taiwan anticipate the United States would use its nuclear arsenal to defend their country against nuclear threats. Although we do not ask about reduced commitments directly, it is possible that if the United States adopted policies substantially reducing its commitments in East Asia, such actions could trigger and deepen the fear of abandonment among Washington’s allies, shaking their confidence towards Washington’s nuclear security guarantee.

Potential Consequences of the Abandonment-Entrapment Dilemma

Scholars have suggested that one consequence of these nuclear anxieties is to encourage states to turn towards nuclear proliferation – either to ensure their protection in the event of abandonment (Bleek and Lorber Citation2014; Debs and Monteiro Citation2016) or to gain leverage over potentially reckless nuclear guarantors (Sukin Citation2020). These perspectives imply growing abandonment and entrapment concerns in East Asia could raise regional interest in nuclear proliferation.

Indeed, interest in nuclear proliferation has been prominent for many years in South Korea. In line with this trend, our polling shows 69% of South Koreans would be in favor of an indigenous South Korean nuclear program. While South Korean support for nuclear proliferation has garnered much attention, several of the dynamics driving this preference are also present in other East Asia states.

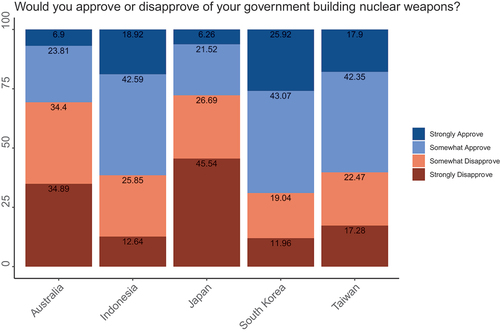

Thus, we inquire – in each state under study – about public receptivity to nuclear proliferation. These results are shown in , which displays the proportion of respondents in each state studied that support nuclear proliferation. We find limited interest in proliferation in Australia and Japan, although only a minority of respondents in both countries report they would be strongly opposed to a nuclear program. This finding aligns with Japan’s historically strong anti-nuclear views and recent Australian insistence on non-proliferation norms in response to global concerns about AUKUS.

Support for proliferation is high in Indonesia and Taiwan, with approximately 62% and 60% of respondents, respectively, expressing views in favor of the policy. In line with previous work, we find substantial interest in South Korea in nuclear proliferation. Each of these states has previously held – and then abandoned – nuclear aspirations.Footnote25 These countries vary significantly in their relationship with the United States, ranging from close treaty ally (South Korea), to possessing strong security assurances (Taiwan), to having relatively new and weak security cooperation (Indonesia). They also vary in terms of their nuclear threat exposure. South Korea and Taiwan both face significant and ongoing nuclear threats from neighboring adversaries, which demand that the countries establish nuclear security measures. Interestingly, Indonesia does not have the same pressing nuclear security concerns, although Jakarta does face continued contestation with Beijing over claims in the South China Sea. Their civilian nuclear energy assets also vary significantly: South Korea is an exporter of nuclear energy technology, while Taiwan has two operating nuclear power reactors, and Indonesia has plans to build a nuclear power reactor.

Moreover, there is variation in the perceived costs of nuclear proliferation. We find that 56% of South Koreans anticipate that nuclear proliferation would result in US sanctions, compared to 24% in Japan, 47% in Taiwan, 36% in Indonesia, and 24% in Australia. Interestingly, support for proliferation in highest in cases where there is a greater belief that proliferation would be costly.

Variation across the sample in support for proliferation suggests the observed public interest in proliferation cannot be fully encompassed by simply applying the current, dominant explanations for proliferation – which focus on features like nuclear threat, relevant industrial capabilities, and the simple presence or absence of formal security guarantees – which would not give consistent predictions across these three cases (e.g. Bleek and Lorber Citation2014). A more nuanced concept of the public’s nuclear anxieties that also considers abandonment and entrapment risks may provide a deeper explanation for when and why citizens support nuclear proliferation.

These findings suggest interest in nuclear proliferation in the region is both stronger and more widespread than previous studies have thought. This, in turn, suggests public opposition may not be a major constraint on governments seeking to establish nuclear weapons programs and could even – as may be occurring in South Korea – encourage political entrepreneurs to investigate the possibility of nuclear armament.

In , we delve further into respondents’ interest in nuclear proliferation, examining how various demographic characteristics and life experiences influence attitudes about nuclear weapons in each of the countries under study. Age is negatively correlated with pro-proliferation attitudes in Indonesia, Japan, and Taiwan (We do not find an age cohort effect in South Korea, in contrast to J.D. Kim (Citation2024)).Footnote26 In all cases except South Korea, female respondents are less supportive of nuclear proliferation. This may reflect the correlation between gender and nuclear preferences evident in other survey work on nuclear politics.Footnote27 Respondents’ level of education has no effect on their attitudes about nuclear weapons, and income has an inconsistently significant positive effect on pro-proliferation beliefs.

Table 2. Correlates of respondents’ approval for indigenous nuclear proliferation.

The relationship between proliferation and ideology varies. Conservative political opinions are correlated with pro-proliferation beliefs in Japan and South Korea but are inversely correlated with these beliefs in Taiwan. This is likely because the conservative parties in South Korea and Japan are historically associated with a greater degree of militarism, while conservatism in Taiwan is associated with greater alignment with China. Ideology has no significant effect on interest in proliferation among Australian and Indonesian respondents.

Respondents’ work experience can influence their nuclear beliefs. We find that – except in Taiwan – respondents with military experience are more likely to anticipate that they would approve if their governments sought nuclear weapons. Conscription in South Korea and Taiwan means we have a high proportion of veterans in our sample. 57% of our South Korean respondents and 49% of Taiwanese respondents are veterans, compared to 7% in Australia, 4% in Indonesia, and 2% in Japan.

Additionally, respondents who have worked in the fields of law, politics, national security, or international organizations are more likely to support proliferation in Korea and Taiwan, but those with policy experience do not have significantly different views from the broader publics in Australia and Indonesia. Respondents with policy experience may be more likely to be familiar with some of the costs of proliferation – such as the need to withdraw from the NPT or the likely imposition of sanctions – making their pro-proliferation preferences unusual. However, some previous scholarship has suggested support for nuclear proliferation may persist even in the face of significant and known costs.Footnote28 That those with policy experience advocate for proliferation may suggest the strength of these preferences.

Although respondents with experience in policy or policy-adjacent fields are not necessarily political decision-makers, they may have more similar backgrounds, knowledge, and preferences to those elite players. Investigating the views of this subsample helps us assess in what ways public preferences might be mirrored at elite levels; in the cases of South Korea and Taiwan, these findings are suggestive that elites may be more likely to support nuclear proliferation than the broader public, thereby emphasizing the importance of understanding the drivers of growing interest in nuclear weapons.

Although public interest in nuclear proliferation is only one ingredient in a complex network of incentives and disincentives, to the extent that public attitudes could encourage or enable nuclear proliferation, it should be taken as a serious threat to regional stability. This is because nuclear proliferation would be both immensely costly and dangerous. It could fracture alliances and partnerships, increase the risk of nuclear accidents or miscalculations, as well as risk preventive or pre-emptive action by adversaries.

Additionally, some scholars have argued nuclear proliferation can trigger “cascades”, where other regional states seek to match the proliferator’s new nuclear capabilities (Allison Citation2004; Carter et al. Citation2007; Clay Moltz Citation2006; Debs and Monteiro Citation2018). This research has focused primarily on adversarial dynamics, suggesting, for example, that new nuclear states may cause their adversaries to proliferate (Hughes Citation2007). Although less developed, some scholars and policymakers have suggested “friendly” cascades are also possible, warning, for example, that proliferation in South Korea could cause other regional powers to explore their own nuclear options (M. Kim Citation2023). This dynamic has been particularly highlighted in the South Korea-Japan relationship, where significant historical tensions complicate the political interaction between these states (Deacon Citation2022; Jo Citation2022).

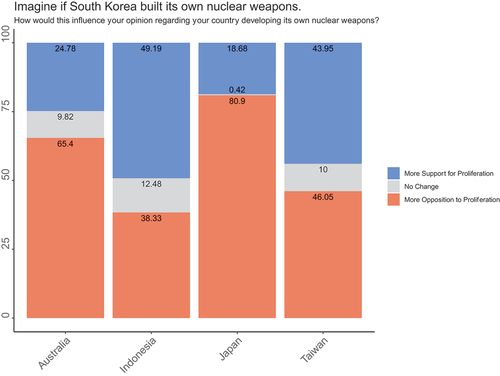

To test this argument, we asked respondents in Japan, Australia, Taiwan, and Indonesia about how they would respond to South Korean proliferation. In contrast to arguments about “falling nuclear dominoes”, our research suggests South Korean proliferation may not cause such cascade dynamics to emerge. shows the percent of respondents in each US ally and partner under study that anticipate their support for proliferation would increase, decrease, or stay the same if South Korea acquired its own nuclear weapons. In each state, only a minority of respondents believe South Korean proliferation would increase their support for their own government acquiring nuclear weapons.

In Australia and Japan, South Korean proliferation would cause the majority of respondents to be less supportive of their own governments developing nuclear weapons. These dynamics may demonstrate the capability-building features of alliances; some elements in Japan and Australia may view a South Korean arsenal as contributing to their own defence against nuclear threats from China and North Korea. This finding may reflect the emerging security environment, in which Japan-South Korea and Australia-South Korean military cooperation has recently expanded. It also suggests the regional alliance structure is under change, moving away from the hub-and-spoke system where Asian states have only “quasi-alliances” with each other (Cha Citation2000), towards a more “networked” alliance system (Dian and Meijer Citation2020; Wilkins Citation2022) or “nodal defence” where bilateral and multilateral security initiatives are intertwined (Simón, Lanoszka, and Meijer Citation2021). In Taiwan, which is a partner but not a treaty ally of the United States, this same dynamic is present to a lesser degree: More respondents believe a South Korean arsenal should reduce the need for a Taiwanese arsenal than think it should encourage Taiwanese nuclear proliferation. In Indonesia, which falls largely outside of the US network in East Asia, the reverse is true.

In South Korea, one proposed alternative to nuclear proliferation has been the deployment of US non-strategic nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula. This proposal is intended primarily to solve the abandonment problem. The forward deployment of nuclear weapons makes a nuclear guarantor more invested in the security of the host state and enables faster and more tailored nuclear response options (Fuhrmann and Sechser Citation2014; Gerzhoy Citation2015). It should therefore make the threat of nuclear use more credible. However, by this very nature, the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons does not solve – and perhaps even worsens – concerns about entrapment.

Indeed, forward-deployed weapons may make conflict more likely by a) sparking provocations upon their deployment, b) lowering response times for both the United States and its adversaries during crises, and c) lowering the barriers to US nuclear use. In addition, nuclear-sharing countries do not gain full control over the use of nuclear weapons deployed on their soil; in all cases, the United States retains the ability to use these nuclear weapons unilaterally. If there are indeed concerns about reckless decision-making by the United States, forward-deployment should do little to alleviate them.

Interest in the US deployment of nuclear weapons is substantially lower than interest in nuclear proliferation. This is shown in , which displays the percent of respondents in each country that support the US deployment of nuclear weapons in Asia. Less than 10% of Australians supported this policy, and just 23% of respondents in Taiwan suggested they would approve of this move. This finding echoes concerns about nuclear entrapment and raises questions about the extent and intensity of abandonment concerns.

Support for the deployment of US nuclear weapons to Asia was notably higher in South Korea (40%). This reflects the South Korean political environment, where several popular politicians, including at times President Yoon Suk Yeol, have advocated for the re-deployment of US nuclear weapons to South Korean soil (Shin Citation2022). However, South Koreans prefer proliferation over re-deployment, in line with the results of earlier studies (Dalton, Friedhoff, and Kim Citation2022). In addition to proliferation or re-deployment, other options have been suggested to resolve some of the stressors on South Korea’s nuclear security. This includes the pursuit of nuclear latency – or the possession of many of the technologies, materials, and expertise needed to quickly develop nuclear weapons, without actually developing them. Although we do not ask respondents directly about nuclear latency or other alternatives to nuclear proliferation, these options might be appealing to publics where we have found strong evidence of a substantial desire to address growing regional nuclear threats.

Across the samples, these findings highlight the seriousness of regional interest in proliferation – this pattern is not simply evidence of a desire for more nuclear protection (as forward-deployment would address that concern nearly as well as proliferation) – but instead signals a unique interest in indigenous nuclear proliferation. This may because proliferation resolves entrapment risks significantly more than nuclear forward-deployment, although both policies should help combat concerns about abandonment.Footnote29

Evaluating US Policy

How should the United States attempt to navigate challenges to the cohesion and strength of its East Asian network? To begin answering this question, we ask respondents to evaluate a series of proposed US policies, each of which may contribute to addressing nuclear abandonment and/or entrapment risks in East Asia.

Although public preferences are only one factor governments might account for, public attitudes can be critical to alliance (or partnership) strength. Anti-American protests in South Korea and Japan are often conceptualized as major challenges to the health of Seoul’s and Tokyo’s US alliances (Yeo Citation2011). The US deployment of THAAD to South Korea persisted despite public protests but has left a lasting legacy on South Koreans’ views of the United States (Martin Citation2017; S. Moon Citation2021). This study provides insight into how various proposed US policies might influence one impactful measure of reassurance. Overall, respondents’ preferences may indicate a desire to balance both nuclear abandonment and nuclear entrapment risks by maintaining US credibility, while encouraging the United States to demonstrate overtures of restraint.

As described in , respondents supported reinforcing communication. 61% of South Korean respondents, for example, believed Washington should increase communication with Seoul about planning for nuclear threats. Majorities in Australia, Taiwan, and Indonesia agreed. Just under half of Japanese respondents supported further communication, but this was still the most preferred choice among Washington’s nuclear policy proposals. Although we could not ask respondents about the full universe of policy options – for example, the United States could also propose diplomatic engagement with adversaries – these results may reflect evaluations of plausible steps the United States could take to alter perceptions of its credibility in East Asia.

Table 3. Respondents’ preferences on US nuclear policy proposals.

There are multiple forms of communication, with varying degrees of interaction between the relevant parties. These range from one party merely informing another to thorough and binding consultations. South Korea and Japan have both sought – and received – more extensive nuclear consultations from the US government, which could help chip away at abandonment and entrapment challenges. By strengthening ties between governments and enabling preparations for nuclear use, consultations reduce the chance of abandonment when crises occur. At the same time, consultations help governments navigate their policy preferences and express risk tolerances, highlighting not only situations in which force ought to be used, but also those in which it should not.

Although respondents express concern about entrapment, they may also be wary of disentanglement. The vast majority of respondents oppose decreases in US military presence in Asia as well as decreases in the size of the US nuclear arsenal; this reiterates that both nuclear and conventional capabilities are essential to US credibility. They are necessary to deter adversaries and could be critical to warfighting. While conventional forces act as a “tripwire”, varied nuclear capabilities are necessary for adequate nuclear planning and response.Footnote30

Disapproval of US force withdrawals could come to a head if debates about burden-sharing and hosting arrangements that were prominent during the Trump Administration were to resurface. Skepticism towards nuclear reductions could potentially complicate efforts at US participation in numerical arms control; US allies and partners could lobby against changes to the US nuclear force structure that they believe will weaken their security. While most respondents do not go so far as to desire US nuclear weapons deployments in Asia, they nevertheless do not want the existing US arsenal to be weakened, either because they fear it would reduce the credibility of US guarantees or because they worry US adversaries would be emboldened. These findings demonstrate that, although there is currently strong confidence in US nuclear assurances, this could be shattered by policy missteps that undermine alliance cohesion.

Policies that would restrain US options for nuclear use – including safeguards and doctrinal changes – were met with only lukewarm views. While a majority of respondents in Australia support such policies, Japanese opposition was clear. Meanwhile, between 40–49% of respondents in South Korea and Taiwan would support either safeguards that limit US nuclear use or a declaratory posture that would do so. While these policies might address some concerns about entrapment, they could also make abandonment more likely and could increase security risks by emboldening adversaries.

There is significant regional variation. The Australian, South Korean, and Taiwanese samples show comparatively high entrapment fears, evidenced by a greater desire for both safeguards and posture-based limitations on US nuclear use. These occur in concert with abandonment fears, shown through a strong aversion to US drawdowns of any warfighting capabilities for the Indo-Pacific theatre. These dual concerns could reflect the “frontline” status of these states to nuclear threats from China and North Korea. Reiter suggests this combination could be especially dangerous, writing: “states with high abandonment fears and high entrapment fears are more likely to acquire nuclear weapons, even if third party security commitments are offered” (Reiter Citation2014, 26).

In contrast, Japanese respondents are reluctant to accept any change to US regional posture, suggesting a precariousness to the current balance in the US-Japan relationship, echoed in the Japanese concerns reported earlier in this paper about whether the US intervention against nuclear threats is likely. In Indonesia, which lacks a formal US alliance, sentiment runs the other way – respondents are tolerant of any change to US posture, suggesting discomfort with the current US approach to regional politics. This contrast shows a key difference between close US partners and those outside of its network.

Conclusion

Using a series of surveys in Australia, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Indonesia, this paper explores patterns in public sentiments at a time of heightened nuclear anxiety around the world. We find that the citizens of US allies and partners worry about both being abandoned and being entrapped by the United States. These fears contribute to growing regional interest in nuclear proliferation, particularly in South Korea, Taiwan, and Indonesia. However, we find relatively little interest in the United States forward-deploying nuclear weapons to East Asia. In contrast to arguments about nuclear cascades, we find that the possibility of nuclear proliferation in South Korea would not necessarily increase public demand for responsive nuclear proliferation elsewhere in the region.

Although public opinion shapes – but does not determine – policy, it nevertheless provides valuable insight into how nuclear security and network management challenges are understood among US allies and partners in East Asia. Building upon this, further research may be valuable in the following five areas. First, scholarship may explore the way in which strategic and moral logics about nuclear weapons work operate simultaneously. Second, it may wish to explore more critically how the public’s nuclear anxiety shapes policy and to further investigate the differences between public opinion and elite preferences. Third, scholars could examine how the nuclear alliance dynamics articulated in this paper affect conventional security dynamics. Fourth, further research is needed to examine how changes in the perceived costs of nuclear proliferation might influence the attitudes demonstrated here. Lastly, scholars may wish to examine the causes and consequences of nuclear anxiety among other sets of US allies and partners.

These findings reveal that the United States faces a difficult set of challenges for navigating its security relationships in East Asia. Allies and partners worry about whether the United States will follow through on its security commitments – and about what will happen if it does. These dual abandonment and entrapment concerns drive growing regional interest in nuclear proliferation and may underlie expanding nuclear cooperation and consultations between the United States and its partners. However, many US nuclear policy changes risk upsetting the delicate balance of Washington’s East Asian relationships. Proposals from the redeployment of non-strategic nuclear weapons to Asia to reductions in the US nuclear arsenal are met with significant disapproval among US allies and partners. To mitigate the risks of extended nuclear deterrence, the United States should more fully understand the sources of nuclear anxiety among its allies and partners as well as develop approaches that generate coalesce between various regional powers’ nuclear policy preferences.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (82.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jonathan Baron, Annabelle Gouttebroze, Kate Hampton, Stephen Herzog, Jiyoung Ko, Karen Lin, Adrian Matak, Luis Rodriguez, Maki Sato, Michal Smetana, Yogi Sugiawan, Rahardhika Utama, and Jiahua Yue for assistance with survey translation, design, and fielding. The authors thank Lee Sang-Hyun, Van Jackson, Tanvi Kulkarni, Fang Liu, Tatsujiro Suzuki, and the team at the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for their feedback and assistance. The authors appreciate two anonymous reviewers’ insightful feedback. Any errors belong to the authors alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2024.2358596

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lauren Sukin

Lauren Sukin is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the United Kingdom.

Woohyeok Seo

Woohyeok Seo is a Ph.D. Candidate in International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the United Kingdom.

Notes

1 We include US security partners as members of this network; for example, Taiwan plays an important role in the US alliance network in East Asia even in the absence of a formal security guarantee from the United States.

2 The concept of nuclear anxiety has been utilized to capture people’s concern about a potential nuclear war and its apocalypse. The term was used initially in Psychology (Meacham Citation1964; Newcomb Citation1988) and was later adopted in International Relations (IR) (McCauley and Payne Citation2010; Sauer Citation2016; Tucker Citation1984). While “critical approaches” in IR can examine its generative role in terms of securitizing, postcolonial, and gender dynamics, we instead adopt the “problem-solving approach” to investigate how the pressures of nuclear anxiety shape citizens’ demands for their governments to solve nuclear problems (R. W. Cox Citation1981).

3 We use the term nuclear proliferation, in keeping with the scholarly literature, to mean the acquisition of an indigenous nuclear arsenal.

4 In solely using the term “entrapment”, we are collapsing what scholars have traditionally seen as entrapment – i.e. an ally being dragged into another ally’s conflict about an issue where the allies do not share interests (Snyder Citation1984) – and the “unwanted nuclear use theory”, which refers instead to disagreements about when to escalate a crisis or conflict occurring over shared interests (Sukin Citation2020).

5 Other scholars have suggested South Korea interest in proliferation is moderated by factors such as wartime exposure to violence (J. D. Kim Citation2024) or threats of sanctions in the event of proliferation (Son and Park Citation2023).

6 Similar dynamics to alliances may persist among partnerships, such as in the US-Taiwan relationship.

7 We draw a distinction between “weak” and “strong” states, as is standard in this literature. Snyder primarily uses this framework, remarking entrapment is typically “a more serious concern for the lesser allies than for the superpower” (Snyder Citation1984, 484). However, Snyder does allow for the stronger partners to worry about abandonment, writing: “when one state has a stronger strategic interest in its partner than vice versa, the first will worry more about abandonment than the second” (Snyder Citation1984, 473). Snyder suggests this is more likely to be true of so-called “lesser allies”.

8 This can emerge through a related process of “emboldenment”, where commitments to an ally increase that ally’s perceived chance of victory in a conflict and thereby “embolden” it to adopt offensive postures that could not be risked in the absence of an alliance (Beckley Citation2015).

9 Entrapment can occur not just between two countries but also in a broader alliance structure. Suppose State A has bilateral alliances with States B and C. State A’s (over)commitment to State B can trigger the fear of entrapment for State C if States A and C do not have convergent strategic interests. For this dynamic, see: Henry (Citation2020, Citation2022).

10 This relates to the idea of moral hazard, where a certain actor behaves recklessly when it is isolated from the effects of such actions. Regarding how moral hazards are at play in alliance dynamics, see: Benson (Citation2012).

11 Partnerships include treaty alliances, security assurances, and other types of defense cooperation.

12 Multilateral alliances have also intermittently emerged in the region such as ASEAN (1967), the Quad (2017), and AUKUS (2021) (Kratiuk Citation2023). The recent creations of multilateral security alliances lead scholars to providing diverse prospect of East Asian security alliances, ranging from “networked” security architecture/design (Dian and Meijer Citation2020; Wilkins Citation2022), to dual hierarchical system of the United States and China (Ikenberry Citation2016), to quasi-alliance and inherently unchanged hub-and-spoke system (Kliem Citation2020).

13 South Korea, for example, does not necessarily have commitments to defend Taiwan, and vice versa. This is unlike NATO’s arrangement, where each state is committed to the defense of each other.

14 While this literature has focused on the relationships between treaty allies, informal nuclear security guarantees can also exist between partners, such as the United States and Taiwan.

15 Indonesia used to have ambitions to develop nuclear weapons under Sukarno’s regime (Zhou Citation2019), but since the 1970s it has been committed to non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

16 See: Ko (Citation2019); Sukin (Citation2020); Sukin and Dalton (Citation2021); Son and Yim (Citation2021); Dalton, Friedhoff, and Kim (Citation2022); The Asan Institute for Policy Studies (Citation2022); Yeo (Citation2023); Kim (Citation2023); Justwan and Berejikian (Citation2023); Lee (Citation2023); Mount (Citation2023); Friedhoff (Citation2023); and Bennett et al. (Citation2023).

17 The survey was conducted using CINT’s Lucid Marketplace product. Ethics approval was provided by LSE. There is no deception. All respondents provided informed consent. See appendix in online supplementary material for details on survey text, including the consent form. The reference number for the ethics approval is “Ref: 198308”.

18 See Coppock and McClellan (Citation2019) and Peyton et al. (Citation2022).

19 See Sanders et al (Citation2007) and Yeager et al (Citation2011).

20 See Appendix A in online supplementary material.

21 See Appendix B in online supplementary material.

22 Indonesian confidence that the United States would come to their defence is notable, given limited US-Indonesia defence cooperation (The two first signed a defence cooperation agreement in 2023). US backing for Indonesian claims in the South China Sea and US antagonism towards China may create a tenuous, “de facto” nuclear security assurance – even though Indonesia is not a treaty ally.

23 For Australia, Indonesia, and Taiwan, the imagined attacker is China. Japanese respondents evaluated threats from both China and North Korea. South Korean respondents were asked about a North Korean attack.

24 Hata et al. (Citation2023), who show that Japanese citizens with high abandonment concerns are reassured by hard-line US nuclear policies.

25 On Indonesia, see Cornejo (Citation2000). On nuclear reversal, see: Levite (Citation2002); Mehta (Citation2020); and Koch (Citation2022).

26 Optimistically, cohort effects could mean that interest in proliferation will wane over time. However, youth views may also evolve over this time.

27 See: Willio and Onderco (Citation2024).

28 Sukin (Citation2020) shows the South Korean public supports nuclear proliferation even when told it would result in significant sanctions from the United States.

29 Nuclear forward-deployment should not resolve entrapment concerns but should significantly reduce abandonment concerns, as should nuclear proliferation. However, abandonment may still be a concern for nuclear-capable states, especially when facing much more powerful nuclear adversaries (such as China). Both France and the United Kingdom continue to express concerns about US abandonment despite possessing nuclear arsenals.

30 Scholars debate the reassurance value of tripwires. On tripwires, see: Reiter and Poast (Citation2021); Blankenship and Lin-Greenberg (Citation2022); Musgrave and Ward (Citation2023); and Sukin and Lanoszka (Citation2023). For challenges, see: Schelling (Citation1966); George and Smoke (Citation1974); and Snyder (Citation2015).

References

- Albright, D., and A. Stricker. 2018. Taiwan’s Former Nuclear Weapons Program: Nuclear Weapons On-Demand. Washington, DC: Institute for Science and International Security.

- Allison, G. 2004. “Opinion | a Cascade of Nuclear Proliferation.” The New York Times. sec Opinion. December 17, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/17/opinion/a-cascade-of-nuclear-proliferation.html.

- Allison, D. M., S. Herzog, and J. Ko. 2022. “Under the Umbrella: Nuclear Crises, Extended Deterrence, and Public Opinion.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 66 (10): 1766–1796. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027221100254.

- The Asan Institute for Policy Studies. 2022. “Extended Deterrence and South Korea’s Role.” https://en.asaninst.org/contents/extended-deterrence-and-south-koreas-role/.

- Beckley, M. 2015. “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of U.S. Defense Pacts.” International Security 39 (4): 7–48. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00197.

- Bennett, B., K. Choi, C. Cooper, B. Bechtol, M. H. Go, G. Jones, D. H. Cha, and Y. Yang. 2023. Options for Strengthening ROK Nuclear Assurance. S.l.: Rand Corporation.

- Benson, B. V. 2012. Constructing International Security: Alliances, Deterrence, and Moral Hazard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blankenship, B., and E. Lin-Greenberg. 2022. “Trivial Tripwires?: Military Capabilities and Alliance Reassurance.” Security Studies 31 (1): 92–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2022.2038662.

- Bleek, P. C., and E. B. Lorber. 2014. “Security Guarantees and Allied Nuclear Proliferation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58 (3): 429–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713509050.

- Brewer, E., T. Dalton, and K. Jones. 2023. “Mind the Gaps: Reading South Korea’s Emergent Proliferation Strategy.” The Washington Quarterly 46 (2): 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2226529.

- Carter, A., G. Oehler, M. Anastasio, R. Monroe, K. Payne, R. Pfaltzgraff, W. Schneider, and W. Van Cleave. 2007. Report on Discouraging a Cascade of Nuclear Weapons States. Washington, D.C: International Security Advisory Board. https://2001-2009.state.gov/documents/organization/95786.pdf.

- Cha, V. 1999. Alignment Despite Antagonism: The United States-Korea-Japan Security Triangle. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. Original print Studies of the East Asian Institute, Columbia University.

- Cha, V. 2000. “Abandonment, Entrapment, and Neoclassical Realism in Asia: The United States, Japan, and Korea.” International Studies Quarterly 44 (2): 261–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00158.

- Cha, V. 2009. “Powerplay: Origins of the U.S. Alliance System in Asia.” International Security 34 (3): 158–196. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2010.34.3.158.

- Cha, V. 2011. “Complex Patchworks: U.S. Alliances As Part of Asia’s Regional Architecture.” Asia Policy 11:27–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2011.0004.

- Cheng, Y., R. Eguchi, H. Nakagawa, T. Shibata, and A. Tago. 2023. “Another Test of Nuclear Taboo: An Experimental Study in Japan.” International Area Studies Review. November. https://doi.org/10.1177/22338659231212417.

- Clay Moltz, J. 2006. “Future Nuclear Proliferation Scenarios in Northeast Asia.” The Nonproliferation Review 13 (3): 591–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700601071769.

- Codevilla, A. 2021. “Put Nukes on Taiwan.” Hoover Institution. June 30, 2021. https://www.hoover.org/research/put-nukes-taiwan.

- Coppock, A., and O. A. McClellan. 2019. “Validating the Demographic, Political, Psychological, and Experimental Results Obtained from a New Source of Online Survey Respondents.” Research & Politics 6 (1): 205316801882217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174.

- Cornejo, R. M. 2000. “When Sukarno Sought the Bomb: Indonesian Nuclear Aspirations in the Mid‐1960s.” The Nonproliferation Review 7 (2): 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700008436808.

- Cox, R. W. 1981. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” Millennium Journal of International Studies 10 (2): 126–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298810100020501.

- Cox, L., D. Cooper, and B. O’Connor. 2023. “The AUKUS Umbrella: Australia-US Relations and Strategic Culture in the Shadow of China’s Rise.” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 78 (3): 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207020231195631.

- Dalton, T., K. Friedhoff, and L. Kim. 2022. “Thinking Nuclear: South Korean Attitudes on Nuclear Weapons.” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs. https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/thinking-nuclear-south-korean-attitudes-nuclear-weapons.

- Dalton, T., and A. Levite. 2023. “AUKUS As a Nonproliferation Standard?” Arms Control Today 53 (6): 6–11.

- Deacon, C. 2022. “(Re)producing the ‘History Problem’: Memory, Identity and the Japan-South Korea Trade Dispute.” The Pacific Review 35 (5): 789–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2021.1897652.

- Debs, A., and N. P. Monteiro. 2016. Nuclear Politics: The Strategic Causes of Proliferation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Debs, A., and N. P. Monteiro. 2018. “Cascading Chaos in Nuclear Northeast Asia.” The Washington Quarterly 41 (1): 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2018.1445902.

- Dian, M., and H. Meijer. 2020. “Networking Hegemony: Alliance Dynamics in East Asia.” International Politics 57 (2): 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-019-00190-y.

- Friedhoff, K. 2023. “Longitudinal Attitudes in South Korea on Nuclear Proliferation.” Korea Economic Institute of America (Blog). February 16, 2023. https://keia.org/the-peninsula/longitudinal-attitudes-in-south-korea-on-nuclear-proliferation/.

- Frühling, S., and A. O’Neil. 2021. Partners in Deterrence: US Nuclear Weapons and Alliances in Europe and Asia. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Fuhrmann, M., and T. S. Sechser. 2014. “Nuclear Strategy, Nonproliferation, and the Causes of Foreign Nuclear Deployments.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58 (3): 455–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713509055.

- George, A. L., and R. Smoke. 1974. Deterrence in American Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gerzhoy, G. 2015. “Alliance Coercion and Nuclear Restraint: How the United States Thwarted West Germany’s Nuclear Ambitions.” International Security 39 (4): 91–129. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00198.

- Gholz, E., D. G. Press, and H. M. Sapolsky. 1997. “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation.” International Security 21 (4): 5–48. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.21.4.5.

- Hata, M., T. Iida, Y. Izumikawa, and T. Kim. 2023. “Does a Patron State’s Hardline Posture Reassure the Public in an Allied State?” Conflict Management and Peace Science: 07388942231216733. December. https://doi.org/10.1177/07388942231216733.

- Henry, I. D. 2020. “What Allies Want: Reconsidering Loyalty, Reliability, and Alliance Interdependence.” International Security 44 (4): 45–83. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00375.

- Henry, I. D. 2022. Reliability and Alliance Interdependence: The United States and Its Allies in Asia, 1949-1969. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca London: Cornell University Press.

- Hughes, C. 2007. “North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons: Implications for the Nuclear Ambitions of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.” Asia Policy 3:75–104. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2007.0000.

- Ikenberry, G. J. 2016. “Between the Eagle and the Dragon: America, China, and Middle State Strategies in East Asia.” Political Science Quarterly 131 (1): 9–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/polq.12430.

- Ito, G. 2003. Alliance in Anxiety: Détente and the Sino-American-Japanese Triangle. East Asia. New York: Routledge.

- Izumikawa, Y. 2020. “Network Connections and the Emergence of the Hub-And-Spokes Alliance System in East Asia.” International Security 45 (2): 7–50. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00389.

- Jo, E. A. 2022. “Memory, Institutions, and the Domestic Politics of South Korean–Japanese Relations.” International Organization 76 (4): 767–798. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818322000194.

- Justwan, F., and J. D. Berejikian. 2023. “Conditional Assistance: Entrapment Concerns and Individual-Level Support for US Alliance Partners.” Journal of Global Security Studies 8 (3): ogad017. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogad017.

- Kim, J. D. 2024. “The Long-Run Impact of Childhood Wartime Violence on Preferences for Nuclear Proliferation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 68 (1): 108–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231159287.

- Kim, M. 2023. “Under What Conditions Would South Korea Go Nuclear? Seoul’s Strategic Choice on Nuclear Weapons.” Pacific Focus 38 (3): 409–431. November. https://doi.org/10.1111/pafo.12238.

- Kim, T. 2011. “Why Alliances Entangle but Seldom Entrap States.” Security Studies 20 (3): 350–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2011.599201.

- Kliem, F. 2020. “Why Quasi-Alliances Will Persist in the Indo-Pacific? The Fall and Rise of the Quad.” Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs 7 (3): 271–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347797020962620.

- Ko, J. 2019. “Alliance and Public Preference for Nuclear Forbearance: Evidence from South Korea.” Foreign Policy Analysis 15 (4): 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/ory014.

- Koch, L. L. 2022. “Holding All the Cards: Nuclear Suppliers and Nuclear Reversal.” Journal of Global Security Studies 7 (1): ogab034. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogab034.

- Kratiuk, B. 2023. “Chapter 12: Strategic Alliances and Alignments in the Indo-Pacific.” In Handbook of Indo-Pacific Studies, edited by B. Kratiuk, J. J. J. van den Bosch, A. Jaskólska, and Y. Sato, 248–266. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lanoszka, A. 2018. Atomic Assurance: The Alliance Politics of Nuclear Proliferation. 1st ed. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9781501729188.001.0001.

- Lee, K. S. 2023. “The Microfoundations of Nuclear Proliferation: Evidence from South Korea.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 35 (4): edad033. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edad033.

- Levite, A. 2002. “Never Say Never Again: Nuclear Reversal Revisited.” International Security 27 (3): 59–88. https://doi.org/10.1162/01622880260553633.

- Liliansa, D. 2023. AUKUS Two Years On: The View from Indonesia. Perth US Asia Centre. https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/AUKUS-Two-Years-on-The-View-from-Indonesia_1.pdf.

- Machida, S. 2022. “Ethnocentrism and Support for Nuclear Armament in Japan.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 7 (1): 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891120939314.

- Martin, B. 2017. “Moon Jae-In’s THAAD Conundrum: South Korea’s ‘Candlelight President’ Faces Strong Citizen Opposition on Missile Defense.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 15 (18).

- McCauley, P., and R. Payne. 2010. “The Illogic of the Biological Weapons Taboo.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 4 (1): 6–35.

- Meacham, S. 1964. “The SOCIAL ASPECTS of NUCLEAR ANXIETY.” American Journal of Psychiatry 120 (9): 837–841. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.120.9.837.

- Mehta, R. N. 2020. Delaying Doomsday: The Politics of Nuclear Reversal. Bridging the Gap. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Moon, S. 2021. “Race, Transnational Militarism, and Neocoloniality: The Politics of the THAAD Deployment in South Korea.” Security Dialogue 52 (6): 512–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/09670106211022884.

- Moon, C. I., and Y. D. Shin. 2023. “South Korea Going Nuclear?: Debates, Driving Forces, and Prospects.” China International Strategy Review 5 (2): 157–179. November. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42533-023-00143-4.

- Mount, A. 2023. “The US and South Korea: The Trouble with Nuclear Assurance.” Survival 65 (2): 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2023.2193104.

- Musgrave, P., and S. Ward. 2023. “The Tripwire Effect: Experimental Evidence Regarding U.S. Public Opinion.” Foreign Policy Analysis 19 (4): orad017. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orad017.

- Newcomb, M. D. 1988. “Nuclear Anxiety and Psychological Functioning Among Young Adults.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 9 (2): 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp0902_4.

- Ningsih, T. 2022. “Nuclear Powered Warship, Does Indonesia Need It?” Jurnal Strategi Pertahanan Laut 8 (1): 16. https://doi.org/10.33172/spl.v8i1.1039.

- Nishida, M. 2023. “Changing Security Environment in East Asia and Its Implications on Japan’s Nuclear Policy.” Journal for Peace & Nuclear Disarmament 6 (2): 327–345. November. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2023.2285024.

- Nurfauzi, A., F. Lampita, and M. Rizky Mahendra. 2022. “The Impact of AUKUS in Indonesian Perspective: Regional Military Balance and Security Dilemma.” Jurnal Sentris 3 (2): 90–103. https://doi.org/10.26593/sentris.v3i2.6079.90-103.

- Peyton, K., G. A. Huber, and A. Coppock. 2022. “The Generalizability of Online Experiments Conducted During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 9 (3): 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.17.

- Posen, B. 2014. Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Reiter, D. 2014. “Security Commitments and Nuclear Proliferation.” Foreign Policy Analysis 10 (1): 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/fpa.12004.

- Reiter, D., and P. Poast. 2021. “The Truth About Tripwires: Why Small Force Deployments Do Not Deter Aggression (Summer 2021).” https://doi.org/10.26153/TSW/13989.

- Rich, T. S., V. Banerjee, and B. Tkach. 2023. “How Has the War in Ukraine Shaped Taiwanese Concerns About Their Own Defense?” Asian Survey 63 (6): 952–979. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2023.2010035.

- Sanders, D., H. D. Clarke, M. C. Stewart, and P. Whiteley. 2007. “Does Mode Matter for Modeling Political Choice? Evidence from the 2005 British Election Study.” Political Analysis 15 (3): 257–285. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl010.

- Sauer, F. 2016. Atomic Anxiety: Deterrence, Taboo and the Non-Use of U.S. Nuclear Weapons. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schelling, T. C. 1966. Arms and Influence. Veritas, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shin, H. 2022. “South Korea’s President-Elect Wants U.S. Nuclear Bombers, Submarines to Return.” Reuters. sec Asia Pacific. April 6, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/skoreas-president-elect-wants-us-nuclear-bombers-submarines-return-2022-04-06/.

- Simón, L., A. Lanoszka, and H. Meijer. 2021. “Nodal Defence: The Changing Structure of U.S. Alliance Systems in Europe and East Asia.” Journal of Strategic Studies 44 (3): 360–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2019.1636372.

- Snyder, G. 1984. “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics.” World Politics 36 (4): 461–495. https://doi.org/10.2307/2010183.

- Snyder, G. 1997. Alliance Politics. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press.

- Snyder, G. 2015. Deterrence and Defense: Toward a Theory of National Security. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Son, S., and J. Park. 2023. “Nonproliferation Information and Attitude Change: Evidence from South Korea.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 67 (6): 1095–1127. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027221126723.

- Son, S., and M. S. Yim. 2021. “Correlates of South Korean Public Opinion on Nuclear Proliferation.” Asian Survey 61 (6): 1028–1057. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2021.1429174.

- Sukin, L. 2020. “Credible Nuclear Security Commitments Can Backfire: Explaining Domestic Support for Nuclear Weapons Acquisition in South Korea.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (6): 1011–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719888689.

- Sukin, L., and T. Dalton. 2021. “Reducing Nuclear Salience: How to Reassure Northeast Asian Allies.” The Washington Quarterly 44 (2): 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2021.1934257.

- Sukin, L., and A. Lanoszka. 2023. “Credibility in Crises: How Patrons Reassure Their Allies.” International Studies Quarterly 68 (2). forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqae062.

- Tsunashima, T. 2023. “Growing Geopolitical Risk Stoking East Asian Nuclear Concerns, Says Expert.” Nikkei Asia. November 19, 2023. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Defense/Growing-geopolitical-risk-stoking-East-Asian-nuclear-concerns-says-expert.

- Tucker, R. W. 1984. “The Nuclear Debate.” Foreign Affairs 63 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/20042082.

- Von Hippel, D. 2023. “Implications of the 2022–2023 Situation in Ukraine for Possible Nuclear Weapons Use in Northeast Asia.” Journal for Peace & Nuclear Disarmament 6 (1): 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2023.2201367.

- Wilkins, T. 2022. “A Hub-And-Spokes ‘Plus’ Model of Us Alliances in the Indo-Pacific: Towards a New ‘Networked’ Design.” Asian Affairs 53 (3): 457–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2022.2090767.

- Willio, E., and M. Onderco. 2024. “Public opinion on nuclear weapons: is there a gender gap?” In Margins to Mainstream: Advancing Intersectional Gender Analysis of Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, edited by R. Dalaqua. Geneva, Switzerland: UNIDIR.

- Yeager, D. S., J. A. Krosnick, L. Chang, H. S. Javitz, M. S. Levendusky, A. Simpser, and R. Wang. 2011. “Comparing the Accuracy of RDD Telephone Surveys and Internet Surveys Conducted with Probability and Non-Probability Samples.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (4): 709–747. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr020.

- Yeo, A. 2011. Activists, Alliances, and Anti-U.S. Base Protests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yeo, A. 2023. “Can South Korea Trust the United States?” The Washington Quarterly 46 (2): 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2226531.

- Zhou, T. 2019. “Sukarno’s Nuclear Ambitions and China: Documents from the Chinese Foreign Ministry Archives.” Indonesia 108 (1): 89–120. https://doi.org/10.1353/ind.2019.0014.