ABSTRACT

Ai Weiwei positions himself first and foremost as a thinker, driven by curiosity and even selfishness, and not shying away from ridicule. Through immersion and direct response to different, unfamiliar conditions, he aims to defamiliarize pre-set thinking, not letting himself be trapped by rationality and led by simplified, predetermined conclusions about the world. Despite the self-proclaimed selfishness at their core, Ai’s artistic acts become selfless through resonance, inviting the viewer into his thought experiments with the world, which he engages with as if the world were a readymade. This conversation departed from the transnational film Tree (2021), where Ai meticulously documents the work of Brazilian and Chinese artisans in creating his 32-metre iron sculpture Pequi Tree (2018–2020). We began with political curiosity as a creative driver for the artist, the influence of Duchamp and Warhol, and the choice of the audiovisual medium to reflect reality. The conversation branched out to consider aesthetics, tying the issue of aestheticization to Ai’s role as a public intellectual, from an earlier refusal of aesthetics or ‘beautification’ in the interest of unmediated transparency to the realization that new aesthetics are needed for new publics.

Introduction

Ai Weiwei’s documentary filmmaking has been received as sitting between art and activism, or artivism (Kara Citation2015). Still, he positions himself first and foremost as a thinker, driven by curiosity and even selfishness – as he constantly reiterates – and not shying away from ridicule. His statements that his filmmaking and acts in general are fueled by political curiosity and that his approach to life aligns with personal learning goals are well documented.Footnote1 For Ai, his acts are not intended for impact, nor do they aim to be artistic – they are conceptual interventions intent on expanding ‘reality’ whenever for him a sense of reality must be produced. Through immersion and direct response to different, unfamiliar conditions, the aim is to defamiliarize pre-set thinking, not letting himself be trapped by rationality and led by simplified, predetermined conclusions about the world, and, in the process, acting on and helping to shape more equitable social worlds. Despite the self-proclaimed selfishness at their core, Ai’s artistic acts become selfless through resonance, inviting the viewer into his thought experiments with the world, which he engages with as if the world (be it China or the West) were a readymade, as a problem to be experienced, and elevating it to the status of art.

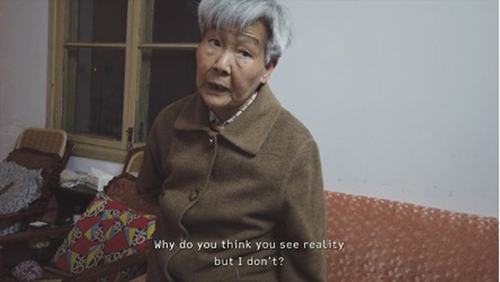

Linked to a Warholian idea of ceaseless documentation, Ai’s filming practice explicitly seeks to be responsive and truthfully reflect reality. Frequently, recording an event or fact on film is for Ai the most direct way to achieve this ‘reality’ or ‘truth’ effect. In collaboration with his brother Ai Dan, his first documentary was Eat, Drink, and Be Merry (2003), about the SARS epidemic in 2002. Intended for a domestic Chinese audience, the purpose of the many documentaries Ai filmed before he left China for Europe in 2015 was to enlarge the public sphere by speaking previously unheard truth to power. In documentaries such as Lao ma ti hua [Disturbing the Peace] (2009), Ai’s videographers film the Chinese authorities filming Ai – what the authorities’ cameras are filming will not be exposed to the public, but Ai’s footage will. What Ai visually documented, exposed and made visible through digital platforms would otherwise be removed from the field of vision by autocratic visualizers. Especially once they were subtitled in English and uploaded on YouTube, these earlier documentaries empowered a full-scale transnational collective media experience beyond the boundaries of the Chinese nation. What belongs to the public should be made public.

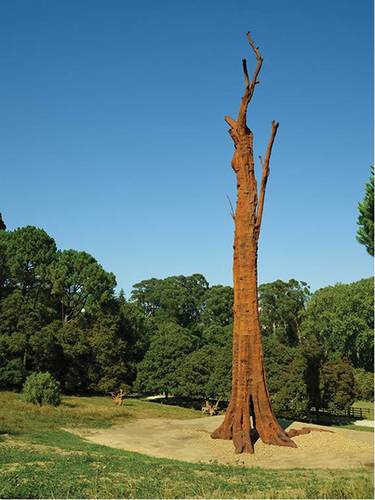

The following conversation with Ai Weiwei, which took place at his house in Montemor-o-Novo, Portugal, in August 2021, departed from his transnational film Tree (2021) (). The film meticulously documents the work of Brazilian and Chinese artisans in creating his 32-metre iron sculpture Pequi Tree (2018–2020) (), from molding, casting, and welding to assembly, from the depths of the Bahian rainforest and the Hebei province of northern China to Porto, Portugal, where both a 26-minute video excerpt of the film and the sculpture were first exhibited at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art (Ai Weiwei: Entrelaçar/Intertwine, 23 July 2021–9 July 2022). Tree extends for around four and a half hours to reflect an objective as possible view of the process that resulted in the monumental sculpture Pequi Tree. Ai describes the film as a work he made primarily for himself, guided by his curiosity, besides the obligation he felt to expand reality in the Anthropocene by telling the story of that dying tree against the backdrop of the deforestation of the Atlantic Forest. When the tree was being molded and cast, he also wanted to go through these processes to feel that reality; his own body was molded and cast for the plaster sculpture Two Figures (2018).

Figure 1. Tree (Citation2021). Photo credit courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio.

Figure 3. Pequi Tree (2018–20). Photo credit courtesy of Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art and Ai Weiwei Studio.

We began with political curiosity as a creative driver for Ai, the influence of Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, and the choice of the audiovisual medium to reflect reality and expand the imagination. For example, Coronation (2020) was remotely directed by Ai using footage recorded by ordinary citizens living in Wuhan during the Covid-19 outbreak in the spring of 2020 (). The centrality of the concept of ‘reality’ to Ai’s art connects to freedom – the freedom to document, to visually record, reality. As Ai noted in an interview with Andrew Solomon, freedom is not absolute; it always requires new definitions: ‘Freedom is not given as a gift. There’s no way we can just give up our responsibility’ (Weiwei Citation2020, 12). For him, it is the artist’s responsibility to document for future generations a key historical moment that is unfolding and whose reach is still uncertain.

The conversation branched out to consider aesthetics, tying this issue to Ai as a public intellectual who, as Sandra Ponzanesi describes, ‘navigates the terrain between individual expression and collective action’ (Citation2019, 216). His earlier films needed to be edited fast and then uploaded as soon as possible – simply put, ‘press record’ was his artistic manifesto. Envisioning a film as an aesthetic product resulting from editing, postproduction, color grading, and sound mixing was not a priority. This ‘press record’ anti-visual-effects vision and get-it-out-there-as-soon-as-possible approach have changed as Ai’s circumstances changed. Human Flow (2017), for example, was filmed for the most part using mobile phones, handheld cameras, and drones in the style of cinema verité (Zimanyi Citation2019). Still, the outcome of documenting that harsh reality is what we would characterize as ‘beautiful’ cinematography. In addition, in the case of Ai’s documentaries on the global refugee ‘crisis,’ he draws on his own experience of displacement in response to being questioned about a potential appropriation and silencing of the voices of the refugees, which links to the ethical considerations involved in engaging with documentary subjects (for example, in the late 1980s, the filmmaker Alan Rosenthal influentially argued for a documentary ethics, noting that ‘the question of ethics is at the root of any consideration of how a documentary works’; accordingly, ‘the filmmaker should treat people in films so as to avoid exploiting them and causing them unnecessary suffering’ [Citation1988, 245]). The aestheticization of reality connects to the ambivalence many have noted in documentary filmmaking, between the pull to document and raise awareness and to entertain through ‘beautiful’ images. We considered this issue regarding the themed-based social investigations that became Ai’s transnational documentaries, from an earlier refusal of aesthetics or ‘beautification’ in the interest of unmediated transparency – in Ai’s words, a rejection, in the form of film, of ‘a mediocre government and social aesthetics’ to unsettle a ‘social ideology’ out of step with reality (Citation2011, 8) – to the realization that new aesthetics are needed for new publics .

When we consider Ai’s documentary work, initially focused on denouncing Chinese authoritarianism and censorship and in defence of human rights and freedom of speech, then tackling the violences of the global refugee ‘crisis’ and the precarities brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic and, more recently, intent on expanding our planetary imagination in the Anthropocene, it might seem that each concept leads him in a different direction. Yet, his role as a public intellectual in speaking truth to power, but not necessarily standing in opposition to power – what has made him an ‘intellectual icon of global stature’ (Ponzanesi Citation2019, 206) – has remained consistent. If, as Byung-Chul Han points out, ‘[t]oday’s crisis of community is a crisis of resonance (Citation2020, 11), the resonance that Ai’s intellectual interventions invite can be a corrective to the ‘strangeness of the world’ (Rosa Citation2019). Entanglement and connectedness, in the sense of living with and through various ‘crises’ as a global community, either as recognizing ‘planetary entanglements’ (Mbembe Citation2021) or learning to ‘stay with the trouble’ (Haraway Citation2016), have been core ontological-ethical principles of Ai’s acts as a public intellectual throughout the years. The ‘trouble’ Donna Haraway refers to relates to contemplating and living in our damaged Earth, devastated by climate change, to vulnerability and loss brought on by planetary metamorphoses in the Anthropocene, and to the ‘strangeness’ we find in the world – now seemingly in perpetual, profound ‘crisis’ – and the attendant anxieties which, in the words of Hartmut Rosa, ‘prevent the subject from opening it up to, tuning into, or becoming involved in the world’ and making her ‘incapable of encounter, even immobilized’ (Citation2019, 121). Haraway explains what she means by ‘staying with the trouble’: it ‘means making oddkin; (…) require[ing] each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become – with each other or not at all’ (Citation2016, 4). Ai Weiwei uncompromisingly builds on this idea of common humanity, taking in the world as a readymade and opening it up for encounter.

In this respect, the choice of a museum in Portugal as an exhibition venue for Pequi Tree adds a transtemporal dimension to the ongoing destruction of the Brazilian rainforest for farming and excessive harvesting that both the monumental sculpture and its accompanying documentary Tree point to. Like the Caryocar brasiliense (pequi tree), the Paubrasilia echinate (brazilwood), another tree species endemic to the Atlantic Forest, was exploited by the Portuguese colonizers in the sixteenth century. The transcontinental and transnational movements that Tree painstakingly documents so that Pequi Tree could be exhibited in Portugal – and that Ai refers to in the following conversation – are material and symbolic. They are integral to the extractive economies that continue to mine natural resources and artisanal, Indigenous knowledge from the global south, an ongoing process since the sixteenth century, and capitalise on the cheap human labour and mass production capabilities of the ‘factory of the world’ (Ai’s own words) that is China.

Ana Cristina Mendes

***

ACM

On several occasions, you have talked about how curiosity leads your art, about how your art connects to finding out more about yourself, about how you want to put yourself in unfamiliar situations and not let yourself follow predetermined conclusions. How does this tie in with the transnationalism of your filmmaking?

Ai Weiwei

We accept a lot of our existence because that’s very safe. But you don’t know what you are missing while you’re trying to be safe. You set yourself up in a different, unfamiliar condition to realize who you are. I forced myself to go to different locations. I spent about forty years in China, another twelve years in New York, and now I am in Europe. I don’t have a sense of place that I can really feel I would like to settle in. I have never owned a property, nor do I have a sense of property, of owning a key to the door of a house, and I have never really felt any place to be my home.

ACM

This brings to mind your film Fairytale (2008) and the idea of the thought experiment of enabling 1,001 Chinese citizens who had never travelled outside of their country to experience other contexts and travel to Kassel, Germany, for Documenta 12 in 2007. But in New York, in a sort of self-imposed exile, you were miserable.

Ai Weiwei

It’s true, I was tired and bored, but I was excited because I had come from China. I had lived in a black hole with my father [the renowned poet Ai Qing] for years [because of the late 1960s and early 1970s policy known as ‘The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement’]. From that, I jumped to skyscrapers. I stayed there for 12 years, from 24 to 36 years old. I had decided never to go back to China, but my father was getting old, so I moved back and spent another twenty-two years in China.

ACM

Your use of video while in New York, from 1981 to 1993, comes across as a simple way of documenting your everyday life, with no intention of incorporating it into an artwork or using video as a medium of expression. This continued for many years – and perhaps still does to some extent. Even with your documentary Lao ma ti hua [Disturbing the Peace], when you went to Chengdu in 2009 to testify on behalf of the earthquake activist Tan Zuoren, you brought photographic and video-recording devices along, and your team filmed the entire process, as was customary, but not with the intention to produce a film. Do you now see yourself as a filmmaker?

Ai Weiwei

I never think of myself as an intentional director or that I want to make a film. I enrolled in film school in 1978, but I never wanted to be a director. As an artist, I like to respond more directly, directly reflect on something, rather than make a piece to reflect something or manipulate something for the camera.

ACM

Duchamp and Warhol: how influential were they for you in terms of your art?

Ai Weiwei

Duchamp had a strong imprint on me, but only for a short time. It’s like when you open a beer bottle. You need that tool to help you, but once you open the bottle, you drink the beer and you no longer need that bottle opener in your hands. The moment is to enjoy the beer. Art can be attitude and gesture, and even unnecessary – Duchamp opened that. With Duchamp, art became about concepts, putting the brain to work, working with the intellect as a poet would do. For him, art was not about visual effects or using visuals to illustrate or express ideas. He opened up practices in European visual culture, and I developed that into a lifestyle or attitude, which can be seen as political. I did not take a urinal as a readymade, I took China as a readymade, or tradition or the West’s political condition as a readymade. Duchamp’s gestures fitted me very well.

ACM

From what I’ve read, Warhol was influential in terms of your practice and process of non-stop documentation, which began when you were living in New York’s Lower East Side, when you moved from the medium of sketching to photography – a medium you felt was closer to reality.

Ai Weiwei

Warhol was very important for me not so much because of his art, which is not particularly interesting to me, but because he was the first artist to understand mass media. He recorded images and situations for no purpose at all. He was taking selfies before social media, fifty years ahead of his time. He sensed the future: plastic culture. Today people are heavily consumerist, but they also have become consumer products. They have become very plastic because they repeat the same things over and over; they have the same dreams and fear the same things. The pandemic has made things worse as everything is just so unified by corporate culture, advertising, and political parties. There is no individual spiritual life anymore. You are either on the right or the left. You are forced to be standing on just one side. It’s so powerful that you’ll be crushed if you stand outside.

ACM

Speaking of the pandemic, in your film Coronation you can see traces of Warhol in the resignification of the film’s title when you reuse the Coca Cola logo.

Ai Weiwei

Warhol is the most relevant product of American culture. America hasn’t produced a second person like Warhol. And that reflects American culture: it ended up with Warhol. About Coronation’s title, I always joke about contemporary culture. In almost all my works, I have a cynical reference to contemporary culture that is there to be identified.

ACM

Your irreverent Coronation title reminds me of your Han Jar Overpainted with Coca-Cola Logo. What do tradition and heritage mean to you?

Ai Weiwei

Heritage, for me, is a part of you that gets lost. You don’t know you have it. I grew up during Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The idea was to break away from heritage because we had to destroy the old world to build up a new one. Of course, that destroyed not just the old world but our memory. We became a generation with no memory. ‘New’ became the new religion, a new temple. After I went back to China, I realized I hated what was happening. That China was not the China I knew before. That China was an entirely new world. It was like early capitalism, repeating that old dream of getting rich fast. There was nothing new for me there, no spiritual life, nothing interesting. So, I got involved in collecting old artefacts because there are so many layers to China. We really must understand the past to understand our position now. I went to antique shops every day, going through thousands and thousands of artefacts, from the beginning of China’s history, five to six thousand years ago, trying to name them and find out relations. I wanted to know how the dynasties changed, the motifs changed, the artisans changed, the material changed, the style changed. It was so fascinating to see such a highly developed human culture that had been completely destroyed, and then a new one started and became fashionable. It’s like a book with chapters so vividly different that they can be independent narratives. That gave me a powerful perspective on visual culture.

ACM

When you collected those artefacts, it was not actually to destroy them. After all, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn was not an iconoclastic gesture.

Ai Weiwei

No, I didn’t mean to destroy any of those artefacts. I am eager to give my own interpretation. What I really want to destroy are fixed ideas, not objects. It is not against authoritarianism or some -ism. It’s really about me; it always comes back to me. It is about my understanding, my language, or my appreciation because those are all so conditioned and fixed. They should not necessarily be that way. The breaking of the vases was not meant to be art. When I went back to China, I never wanted to have an exhibition there. It’s not possible. I bought a lot of those cases to make a series and make my brother happy. I told him to try to capture me with a Nikon camera. Once you push it, you can take six frames. I asked him: ‘Are you ready?’ He said: ‘Yes.’ With the first click of the camera, the vase fell to the ground. Unfortunately, he didn’t catch that first one with the camera. I realized that from the clicking sound. I said: ‘I think you missed it.’ I told him: ‘Let’s make sure we get the second one.’ And he captured it. So, it’s not art. I don’t consider it art. It’s just some acts that were recorded and put in the drawer.

ACM

In an interview, you noted that your enrollment at the Beijing Film Academy ‘was not so much due to an interest in film as it was a means to “escape society”’ (Citation2011, xviii).Footnote2 And yet, while you never set out to be a filmmaker and think of yourself as a filmmaker, your filmography includes dozens of titles to date. How do you find yourself continuously moving from political curiosity to the filmic language, from the concept to the audiovisual medium?

Ai Weiwei

I am still making films, but I always say this will be the last one. Then something jumps out, and the best way to narrate the story is to film it. For me, it’s very natural. When you’re hungry, you eat, or when you’re thirsty, you drink. It is that simple. It is about documenting because very often what we have experienced, we don’t really know. But if we look at the documentation, that is another reality. The real reality is heartless; it doesn’t really care. The facts don’t care, but we try to find the truth in the facts. When we are recording, we are recording the facts. When we make a two-year-long story fit into 120 minutes or 90 minutes, that’s not about facts anymore: it’s a narrative, like a novel or a poem. The truth will come from the facts, from an objective view. For example, the film I’m doing now [Tree] is about a tree cast in Brazil, made in China. That film, which is around four-and-a-half hours long, is quite an objective story of the process.

ACM

The film can try to be objective, but you needed to edit it.

Ai Weiwei

Because you have hundreds or even thousands of hours of recording. You must sacrifice a lot.

ACM

But editing is interpretation. It’s your interpretation.

Ai Weiwei

Editing is a very strong act of choice. That choice you can see as an interpretation because you must select. You try to lead the viewer, or you’re trying to use the viewers’ view to lead yourself.

ACM

Between 2019 and 2021, you made an astounding number of films: The Rest, Rohingya, Vivos, Coronation, Cockroach …

Ai Weiwei

I’m a maniac. My stupidity pushed me into a deep hole.

ACM

Your curiosity.

Ai Weiwei

No, it’s really stupidity. I love to get involved, totally involved. I always think this will be my last film. I want to have the feeling of total involvement before death.

ACM

How do you judge a medium’s formal potential and affordances when choosing different media to show reality?

Ai Weiwei

You need a vocabulary to create a meaningful sentence. But, of course, you don’t want to use existing vocabulary because you have thought about it; you have questioned it. That means you have to set up a totally unknown condition for yourself, very possibly a very awkward condition, like casting a standing tree in the middle of the Brazilian rainforest, 30-some meters high. To take that time and effort to cast something like that is to set up a possibility to develop that vocabulary. To cast the pequi tree, I needed to get travel visas to Brazil for a group of people I had been working with in China. We had to ship all the necessary materials from China and get permission for our lorries. There was a lot of research, waiting and frustration involved. All those issues built up. It was not about the tree anymore. It was about globalization, bureaucracy, state policy and how difficult it was to actually do the work. You must make sure the artisans do not feel totally lost, so you needed architects and engineers in Brazil to supervise the work and calculate the possibilities. Not to mention that this hollow tree had three two-meter-long snakes – one red, one black and one green – bats and millions of bees living inside. You’re not casting a tree just from the outside but also from the inside. You must work double, and the inside of the tree was very difficult to cast. It takes a lot of work to think about how to cast something; to structure it in silicone, take it down, clean it, ship it back to China, iron cast every piece, and weld it to make a tree. It was impossible to sense the work beforehand because the tree was very irregular – after all, trees are organic. We had to measure every layer to make sure we could put the solid pieces back later, inside and outside. Everything had to be marked and measured (). We had to build a three-meter-deep foundation for Serralves to show the tree, just like a swimming pool. But I had set up this simple concept, to cast the tree, and I could not change my idea. It didn’t matter how long it took or how much effort it needed. That was all part of the process. That’s how the object Pequi Tree was made involving three continents: with natural resources from Brazil and human labor in China, in a small Chinese town that has been making iron castings for 100 years. After that, we reassembled the tree at Serralves for cultural consumption in Europe. I could not show it in China. There, they would never understand it. Maybe they could, but my name cannot be mentioned under this regime.

ACM

Why did you choose to engage with this tree? Was it because, following Duchamp’s conceptual approach to art, the artwork Pequi Tree developed after this fortuitous encounter with the dying tree – an encounter between you and the tree that attached layers of meaning to that entity as objet trouvé? Following your casting of this hollow, over 800-year-old pequi tree in Trancoso, Bahia, in 2017, after days of heavy rain, the original tree collapsed in 2020. Or perhaps you choose to cast the tree and painstakingly visually record the process of molding, casting, and welding it to prevent it from lapsing into oblivion (in fact, the species is almost extinct) out of a desire to perpetuate its spirit as it was nearing its death? Because, even if you replicated the tree and arranged for its different parts to be reassembled and exhibited in a museum context, the tree will not be eternal, subject as it is to rusting and other forms of decay, exposed to the natural elements and disassembly/reassembly.

Ai Weiwei

I didn’t really have a reason to support my act. Every reason I give for wanting to film is to simplify or fall into the trap of rationality. In life, we always try to make sense, to simplify into categories. Our language is a tool for us to think. Emotion is not a language yet, but once it becomes a language, we are being regulated. Language is a dictator: it dictates our behavior, our way of thinking and our conclusions. It simplifies our emotions because we are using an accepted language that cannot really carry emotions. As an artist, I’m always interested in dealing with language because a concept must also be a language, right? A human’s mind is very narrow; it doesn’t matter how much we think we understand the universe. Our knowledge comes from constructions. We know there’s a lot beyond that, but we cannot really know what it is. The film about the process of casting the pequi tree in Brazil is a film I made for myself. I feel very emotional about the production. Nobody would even care about the tree if I didn’t make the film, right? Before the film existed, how would you care about that tree standing there? For me, it was absolutely an obligation to tell the story of that tree, but, basically, it was always oriented by my curiosity. In that sense, I am very selfish. I demand answers. I demand to go through the process to feel it. Sometimes this means being ridiculous, but I think ridicule is a part of intelligence. If you are not afraid to be ridiculous by putting yourself in an awkward situation, you realize that is reality. Ridiculous is reality sometimes.

ACM

That idea of ridiculous being reality reminded me of your parody of Gangnam Style in your 2012 video Caonima Style, which was banned in China … . And sometimes, as you have pointed out about the refugee ‘crisis’ in Europe, reality is surreal. The situation you encountered in Lesbos in 2015, which prompted you to film Human Flow, was surreal. You repeated this idea many times in interviews: that reality was surreal, resonating with a surrealistic montage. The refugees you saw arriving on rubber boats, people in desperate need of hospitality, inhabiting the image of the Mediterranean touristic resort – that surreal reality needed to be documented. Even after moving your studio there and making Human Flow, it still did not look real.

Ai Weiwei

That reality was beyond the imagination. Why does reality become surreal? Because you already have a fixed understanding of reality in that place: of a nice life and kind, open-hearted people. Then you see a boat coming in, with lots of men, women, and children. And nobody cared about them. They just stayed on the shore. That was then; now, it’s much worse. They push those boats away before they get close to the border. Thousands of people have drowned trying to reach Europe. This is unacceptable. This is surreal. It’s two pictures that do not go together. If I didn’t go to Lesbos, if I didn’t film it, if I didn’t see it with my own eyes, I would be led by a common conclusion. But once you go there, you feel you must use your voice because that’s honest recording.

ACM

Your voice, or the refugees’ voices?

Ai Weiwei

They – the refugees’ voices and mine – become one for survival. I’m also a refugee. I cannot live where I grew up.

ACM

Can we go back to the controversy surrounding your reenactment in Lesbos of Alan Kurdi’s image and the accusations of appropriation?

Ai Weiwei

Culture, for me, means misinterpretation, a wrong interpretation. Cultural exchange is a misinterpretation. Everything is a readymade for me. I would put myself in the same condition as refugees to question that condition because I do not want to shy away from that. Most people would say: ‘Oh, you cannot touch that.’ Liberty means to question; otherwise, you don’t have liberty. If you have a taboo, that’s not liberty. Of course, you need to be respectful. But, in that case, I didn’t respect the situation because I was on the shore in Lesbos, seeing people coming off the boats, hundreds of them, thousands of them. For The Rest and Human Flow, I talked to and interviewed them. They told me their daughters had drowned, their relatives had drowned. So many people drowned. Are we listening? Are the Europeans listening? No. They used the sentiment of outrage for that boy, Alan, who looks a little bit like a white boy.

ACM

You cannot see his face.

Ai Weiwei

The colors of his clothes are very much like the colors of Pepsi: blue and red. I just had to study why that image became so popular. I was teaching [at the Berlin University of the Arts], and as an assignment I said, ‘Let’s study that image.’ His brother is 50 meters away, in between rocks, also dead. Nobody cared about capturing the image of his brother because that image is not perfect. It is all about the visual when thousands of kids are dying. About the reenactment: it was not even my intention to do that. An Indian magazine [India Today] was doing a story about me, and they wanted to use an image for the cover. I asked them, ‘What do you want me to do?’

ACM

The Alan Kurdi reenactment was not your idea?

Ai Weiwei

Oh no, but the media doesn’t care. The photographer asked me, ‘Do you know the Alan Kurdi image? Can you do something like this?’ I was hesitant because I didn’t want to lay on the beach – it was very rocky, you know? I knew that image, but I didn’t know it was so popular. As an artist, I did not have any problem doing that pose. The photographer went back to India. I did not see the magazine article, and he never sent me the cover image. He then said the image had been leaked on the internet. This was very strange. There were a lot of arguments about this. I still don’t want to know why. What’s the problem? I am an artist. I think it’s just hypocrisy to say, ‘Oh, you cannot do that.’ That is not a clear reason for me.

ACM

Especially regarding your transnational documentaries on the refugee ‘crisis,’ the issue of aesthetics – more precisely, the aestheticization of reality – seems to be a recurrent one in interviews. In your earlier documentaries, we sensed that, for you, a way to fight fascism and authoritarianism was through rejecting the appropriation of aesthetics by unceasingly bearing witness to reality and engaging in unrelenting documentation. You were not deliberate regarding matters of aesthetic judgment – the recording was the artistic and political intervention in the public sphere. While your earlier films were rough and raw, your more recent films have stunning, beautiful images, in the sense of being more aesthetically pleasing. Could you expand on how – and if – ‘beautifying’ remains a loaded word for you today? Do you find yourself now pursuing any kind of visual effect in these transnational projects?

Ai Weiwei

Roughness or un-roughness is, for me, the same when making a film. In the early films, we had to do them for the next day to put them online. We wanted people to see the images, so we only needed a sketch. Now we have time to show the films in theatres or film festivals. We must respect people’s watching habits. Westerners eat at a table, using plates and knives and forks. A more expensive restaurant only uses larger plates. This does not mean that the food is better, but people appreciate that. So, it depends if you want to eat your grandma’s food, which is many times better, or you want to go to a luxurious restaurant. It is a matter of experiencing a situation differently. A so-called good image means nothing to me. Every part of nature, every leaf, every piece of grass, is much more beautiful than visual effects.

ACM

Human Flow, The Rest, Rohingya, Coronation, and Cockroach have different distributions and scales of postproduction from your pre-2015 documentaries, which necessarily come with costs. This process is very different from, for example, that of the documentary Lao ma ti hua, which you ‘distributed widely and without cost around the nation, almost to anyone who requested it over Twitter’ (Weiwei Citation2011, xxiii). The transnational documentaries, perhaps because their intended audience is global, are supported by key players in the entertainment industry, such as the BFI, and distributed by major film studios, such as Lionsgate Films for Human Flow, or available for rent or purchase via your website Ai Weiwei Films (www.aiweiwei.com) on iTunes, Amazon, Google Play, and Vimeo On Demand. In practical terms, this means you have to pay to access these latest films.

Ai Weiwei

This is not about money. The payment is for respect. It’s like the higher doorsteps we have in Chinese houses. Today, everything’s too convenient. You can just grab everything. We set a small charge to access the films, like what you’d pay for a coffee in New York or London. We give a lot to people for free, for screenings in many universities and organizations in poorer countries. But you must set up something to show respect. We wanted to make this a little formal. We could put the films on YouTube for free, but people are just in and out, they’re not really watching. On Vimeo, they are also maybe not watching. We made films that cost hundreds of thousands, and some films may have only 200 people watching. Some of them, like Rohingya [about the Rohingyas who fled violence and persecution in Myanmar in 2017 to seek refuge in Bangladesh], only a few hundred people watched it, probably not even that much. It’s very little. We never see the money.

ACM

In your speaking truth to power, in your confrontation of and non-cooperation with power structures, in your flipping the middle finger to authority, you have put yourself at significant personal risk. You have discussed the difference between being fearless (what you look like) and fearless (how you actually feel). As a politically engaged figure, you often appeared on screen, challenging authority directly or conducting interviews during your investigations. Do you see yourself as a public intellectual?

Ai Weiwei

I would like to be a public intellectual, but what I care about the most is being intellectual. Public for me means that you are not hiding. Publicity, I will say, put me in a safer situation in China. I was in the spotlight, not in the shadow, so they could not do anything secret to me. I wanted to be really public because it gave me a sense of security back then. I did not want to disappear without people knowing. In the West, they make you public anyway, with all the interviews. I never asked for an interview. I never called a journalist in my life, nor a museum curator. If you stayed with me for a month or a year, you would see that my phone never rings and I never call anybody. I’m the kind of person who is comfortable feeding chickens, collecting eggs, picking up fruits, and watering the plants. I also love writing and like to do interviews. It is like writing: it’s about direct responses. That’s why I respect writers. My father was a writer, and I have just finished my memoir [1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows: A Memoir], which is coming out in November [2021]. That book took me ten years. I feel very accomplished. I have come a long way as a writer. I always like to make an argument, without which there cannot be intellectual exchange.

ACM

Do you strive for public impact as an intellectual?

Ai Weiwei

Not necessarily. I want to challenge ideas, not necessarily to have an impact. Without identity, we cannot call ourselves individuals. You are an individual because you have an identity. You have an identity because you have your intellect. If you don’t have those, I think your life is not worth living. Of course, most people are not even conscious of this. But I am conscious of this. I always try to find out who I am. For that, I must put myself in strange, awkward situations, such as talking to you.

Filmography

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2003. Eat, Drink, and Be Merry. China: Ai Weiwei Studio.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2008. Fairytale. China: Ai Weiwei Studio.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2009. Lao ma ti hua/Disturbing the Peace. China: Ai Weiwei Studio.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2014. Ai Weiwei’s Appeal ¥15,220,910.50. China: Ai Weiwei Studio.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2017. Human Flow. Germany: 24 Media Production Company/AC Films/Ai Weiwei Studio.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2019. The Rest. Germany: AWW Germany/AWWF/ART Foundation.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2020. Cockroach. Hong Kong/Germany: AWW Germany.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2020. Coronation. Germany: AWW Germany.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2020. Vivos. Germany: AWW Germany.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2021. Rohingya. Germany: AWW Germany.

Weiwei, Ai, dir. 2021. Tree. n/a: Ai Weiwei Studio.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Cristina Mendes

Ana Cristina Mendes is Associate Professor of English Studies at the School of Arts and Humanities of the University of Lisbon. She uses cultural and postcolonial studies to examine literary and screen texts (in particular, intermedia adaptations) as venues for resistant knowledge formations in order to expand upon theories of epistemic injustice. Her research interests are visual culture, postcolonial theory, adaptation studies, and Victorian afterlives.

Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei (*1957, Beijing) lives and works in multiple locations, including Beijing (China), Berlin (Germany), Cambridge (UK) and Lisbon (Portugal). He is a multimedia artist who also works in film, writing, and social media.

Notes

1. See, for example, Ai’s interview with Tim Marlow: ‘I have to have my understanding and perspective about what kind of world we live in, so it’s really about how I understand the situation’ (Weiwei Citation2020, 57).

2. Quoted in Karen Smith’s Ai Weiwei (New York: Phaidon, 2009), 64.

References

- Han, B.-C. 2020. The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present. Cambridge: Polity.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Kara, S. 2015. “Rebels without Regret: Documentary Artivism in the Digital Age.” Studies in Documentary Film 9 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1080/17503280.2014.1002250.

- Mbembe, A. 2021. Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ponzanesi, S. 2019. “The Art of Dissent: Ai Weiwei, Rebel with a Cause.” In Culture, Citizenship and Human Rights, edited by R. Buikema, A. Buyse, and A. Robben, 215–236. London: Routledge.

- Rosa, H. 2019. Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, Trans. J. Wagner. Cambridge: Polity.

- Rosenthal, A. 1988. New Challenges for Documentary. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Weiwei, A. 2011. Ai Weiwei’s Blog Writings, Interviews, and Digital Rants, 2006–2009, Ed. and trans. L. Ambrozy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Weiwei, A. 2020. Conversations: Ai Weiwei. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Weiwei, A. 2021. 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows: A Memoir. New York: Crown.

- Zimanyi, E. 2019. “Human Flow: Thinking with and through Ai Weiwei’s Defamiliarizing Gaze.” Visual Anthropology 32 (3–4): 377–379. doi:10.1080/08949468.2019.1637691.