ABSTRACT

The 21st century resurgence of the political thriller genre was informed by two factors: the post 9/11 geo-politics and the new global landscape of film and television. Tehran (Kan, 2021-), the recent political thriller series from Israel on Apple TV+, offers an illuminating example of the transnationalisation of the genre. By analysing the series along with discussions on its production context and reception in Israel, Iran and internationally, we demonstrate the complex and shifting relationship between the entertainment and the political elements, which typify the genre and its global travel. Revolving around the topical geo-political issues, the series’ action-based plot delineates an Israeli military operation to neutralise the Iranian nuclear reactor, while deeper layers of the narrative point to its political aim: countering negative representations of Iran and provoking a critique of Israel’s own forms of oppression and its internal identity crisis. Placing at its centre a young Israeli female agent, whose complexity is rooted in her hybrid identity as a migrant Iranian-Jew, the series renders visible suppressed histories of Iranian-Jewry’s fractured relationship with Zionism. This, we claim, is the core of the series’ political critique, which despite its potential subversion was largely lost in the reception space.

The 21st century has seen meaningful resurgence of the political thriller genre and ‘spy narratives’ both in cinema and on television, where the genre has been dormant for several decades (Takacs Citation2012; Castrillo Citation2020). This resurgence was informed, as many scholars have noted, by two key factors: the geo-politics that developed in the aftermath of 9/11 and the new landscape of film and television production, dominated by global streaming platforms (Saunders Citation2019; Glynn and Cupples Citation2015; Castrillo and Echart Citation2015; Castrillo Citation2019, Citation2020; Takacs Citation2012; Kumar and Kundnani Citation2014). Reflecting the zeitgeist of the new millennium, these new political thrillers are marked by interconnectivity and transnationalism, both in their content and production contexts, by greater emphasis on contemporary geo-political concerns and by seemingly new gender politics, subverting the hitherto masculine typification of the genre. Tehran (Kan, 2021), the recent political thriller series from Israel to hit the global screens, offers an illuminating example of the transnationalisation of the genre and its intrinsic tensions. Purchased by Apple TV +, the series was the first non-English-speaking programme acquired by the new global platform and went on to win the Best Drama Emmy Award in 2021. Revolving around the topical geo-political issue of Iran’s nuclear power, it invites pertinent questions about the relationship between the national and the transnational and between entertainment and politics in the new transnational landscape of screen media production and consumption. As our discussion in the following pages seeks to show, while Tehran exhibits many of the generic characteristics of the 21st century political thriller, as a political text it contains a critique that emanates from the subtleties of the specific socio-political world it depicts and addresses particularly Israeli anxieties. This critique was not only often missed or overlooked in the reception space but can also be thought of as working against the action (and the thrill) that was marked as the appeal factor of its international success.

While the political thriller eludes a precise definition as a distinct genre, scholars have generally agreed that one of its salient characteristics is its close relationship with actualities – referencing, in different ways, political events and concerns at the time of production. Examining the Hollywood political thriller from its inception in the 1960s to the turn of the century, Castrillo and Echart (Citation2015) contend that what distinguishes this genre from other types of thrillers, such as crime fiction, is that its central conflict is political in nature. Politics, they claim, ‘cannot be just the backdrop or setting, but have to be inherently associated to the criminal source of conflict that creates the dramatic premise of the film’ (113). While the narratives can be fictitious to varied degrees, they all importantly ‘[travel] into the extraordinary while at the same time holding on to very concrete expectations of verisimilitude’ (109). This emphasis on verisimilitude to political atmospheres and current events is what makes the political thrillers, as the authors claim, not only a specific form of thriller narrative but also a particular kind of political text (ibid; our emphasis).

Setting the tone for the resurgence of the genre at the turn of the 21st century were American series such as 24 (20th Century Fox Television, 2001–2010), The Agency (CBS, 2001–2003), Alias (ABC, 2001–2006) and many others.Footnote1 These programmes heralded a new era of television dramas not only in terms of their narrative complexity and cinematic approaches (Jasson Citation2015), but also in relation to their thematic engagement with the War on Terror; addressing popular anxieties about the technologies and processes of globalisation through the lens of terrorism (Takacs Citation2012, 61). Many of these narratives deal with the challenges raised by homeland security, intelligence, and surveillance in the context of counter terrorism and often ‘[recognize] a world of moral ambiguity and emotional complexity’ in which lead characters, often flawed, ‘are trapped in social systems, hierarchies, or incompetent bureaucracies where doing the right thing is neither easy nor obvious’ (Castrillo Citation2019, 111).

If the political thriller genre from its onset was typified by its verisimilitude to political atmospheres, these new political thrillers exhibit what we call intensified verisimilitude – a more elaborate, detailed and immediate reference to political and geo-political current events – sometimes responding to these events in real time. This intensified verisimilitude is pivotal in marking them in the contemporary reception space not merely as entertainment thrillers, but as political texts whose effect on public opinion is worthy of serious consideration. Many scholars have addressed the relationship between programmes like 24 and Homeland (Showtime, 2011–2020) and dominant discourse of the ‘War on Terror’ led by the American administrations (Castonguay Citation2015; Kumar and Kundnani Citation2014; Takacs Citation2012; Van Veeren Citation2009; Saunders Citation2019; Pears Citation2016). Political thrillers, forming part of the emerging category of ‘geo-political television’, are increasingly seen as important objects of study for disciplines such as politics and international relations (Pears Citation2016; Saunders Citation2019).

The global expansion of (American) Subscription Video On Demand (SVOD) streaming platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple TV + has not only increased multinational circulation of American television programmes, but has also generated a significant shift in the approach to original content from around the world.Footnote2 One of the distinct characteristics of the ‘post-television’ era, as it is often called, is the ready availability of ‘foreign-language’ TV programmes that previously wouldn’t have been expected to cross borders (Lavie Citation2015). To an extent, new models of acquisition and distribution that were formed by streaming platforms disassociated both content and audiences from their geographical (regional or national) location. As Amanda Lotz noted, if historically international distribution was tied to models of national demographics, the on-demand and individual subscriber model pioneered by companies like Netflix afforded them with technologically competitive tools that ‘enable them to imagine their subscribers as transnational clusters of tastes and sensibilities’ (2021, 207). Within this new transnational media landscape, the popularity and influence of political thrillers stretched far beyond their country of origin. While still dominated by American productions, a wider and more linguistically diverse selections of titles from different countries became available on streaming platforms to an increasingly transnationalised audience.Footnote3

Israel, despite its small film and television industry, has been a notable beneficiary of this new climate, not least due to its historical production and political links with the US, and its exported thrillers were in many ways influential in shaping the trends of the new transnational political thriller. Recent years have seen a fast-growing list of original Israeli productions available on streaming platforms. Israeli espionage and war thrillers – films and tv series – are one of the prominent genres exported, with an indicative list of titles including: Prisoners of War (Hatufim, Keshet, 2009–2011), Fauda (YES, 2015–2020), Mossad 101 (Reshert, 2015–2018), False Flags (Kfulim, Keshet, 2015-), Our Boys (Ha’nearim, Keshet/ HBO, 2019), The Operative (Yuval Adler, 2019), The Angel (Ariel Vormen, 2018), The Red Sea Diving Resort (Gideon Raff, 2019), Shelter (Eran Riklis, 2017) and Hit and Run (Netflix, 2021-).

Prisoners of War (POW) and Fauda, both revolving around Israeli security forces combating what the programmes frame as Palestinian terrorism, are the most renowned of these examples. Winning sizable international viewership, critical acclaim, and scholarly attention they can be thought of as paradigm-setting in their influence on the development of the genre’s tropes and its transnational production models.Footnote4

POW, was initially sold as a format and was adapted by the creators of 24 into the American hit series Homeland. Other international adaptations followed, including the Russian series Rodina (WEIT Media, 2015) and the Indian P.O.W. – Bandi Yuddh Ke (Star Plus, 2016–2017)). Dubbed as the ‘original Homeland’, POW has since been sold in its original form to over 65 territories. Marking the first non-English speaking show aired by the US streaming platform Hulu, it was rated by the New York Times in 2019 as the best international television show of the decade, overtaking popular thrillers such as Killing Eve (BBC, 2018-), The Bridge (Bron/Broen, SVT1/DR1, 2011–2018) and Money Heist (La casa de papel, Antena3, 2017–2021) (See Hale Citation2019). Fauda was produced in a transnational market already more open to non-English speaking original productions. Created by Lior Raz and Avi Issacharoff for the Israeli satellite network YES, it was bought by Netflix in its original form in 2016, shortly after its release on Israeli television, making Fauda the first Israeli ‘Netflix Original’ production, with Netflix investing in the production of the subsequent seasons (Shechnik Citation2016 and Kamin Citation2016). According to Dana Stern, the Managing Director of Yes Studio, the model of acquisition pioneered by Netflix for Fauda was a game changer for the Israeli TV and film industry. Since its airing on Netflix, the series’ notable popularity stretched far beyond the US and Europe with its biggest fan base reported to be in India and Brazil (Wiseman Citation2021).

Tehran was conceived from the onset as a transnational co-production and was framed – looking to emulate Fauda’s model – as the next big political thriller hit coming from Israel.Footnote5 Created by Moshe Zonder, a writer on Fauda’s first season, the series was supported domestically by Kan (Hebrew for ‘Here’), the new incarnation of the Israeli public service broadcaster, and was reported to have the highest budget in Israeli television production to date.Footnote6 Cineflix Media (the UK’s largest independent TV content distributor) acquired the international distribution rights at the early stages of the series’ development and funded 40% of the production costs. A deal with Apple TV was secured shortly after the filming of the first season ended and included investment in the production of two subsequent seasons (a second season is reported to be in production at the time of writing this article) as well as the rights for international distribution. Airing on Israeli television in June 2020, the series became available internationally on the Apple TV + platform in September 2020. In Iran, where Apple TV is not available, the series was accessed by viewers through unofficial satellite services (online and telegram channels that showcase international programmes with Persian subtitles).

The success of these Israeli series invites interesting questions in relation to how the political thriller genre operates in the new transnational media landscape. If, as we suggested above, the political thriller is a particular kind of political text in which the verisimilitude to actualities is key, how might these texts be understood by transnational audiences who often lack the knowledge or lived experience of such actualities? This question becomes more pertinent when considering the curatorial strategies of VOD streaming platforms, which in eschewing traditional film and television marketing categories, often foreground the generic attributes or ‘universal’ elements of the content they showcase rather than the specific national, geographical, or socio-political contexts. In the case of political texts, the erasure of these signifiers on a paratextual level may well have significant implications for the ways these texts are approached by different ‘transnational clusters’ of viewers and the meanings they derive from them.

Studying the international popularity of Fauda, Ribke (Citation2019) suggested its success could be attributed to a degree of familiarity international audiences have with the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, due to its long-standing coverage in international media. In the case of Tehran that focuses on Israeli-Iranian relationship, which is perhaps less familiar to international audiences, the merit of the series was judged – at least in the international acquisition stage – on its mastery of the generic characteristics of the thriller: action and suspense. Tehran’s many plot twists and slick look were deemed on a par with popular genre-led American dramas and were seen to be the selling point of the series to the international market, rendering the specificities of Israeli-Iranian geo-politics ‘universal’. As Julian Leroux, the series’ international distributor, explained to the magazine Variety:

The series is really about going straight into the action. It’s a very welcoming show. That’s something that is very important for me when approaching local shows, wherever they’re coming from, having a premise which is universal … . that viewers who are not from Israel or Iran don’t need to have an [encyclopaedia] or a PhD to understand this series. (Ramachandran Citation2020).

The curatorial and marketing strategy of Apple TV +, as we will discuss later, has similarly foregrounded the generic characteristics of the series, to the extent of masking its political stand.

‘(De)othering’ Iran – intensified verisimilitude and the production of authenticity

Moving away from the more commonly represented setting of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Tehran’s socio-political focus is the is Israeli- Iranian relationship. The narrative axis revolves around an Israeli military operation to neutralise the Iranian nuclear reactor. Following the trend of the 21st century political thriller, its main protagonist is a young and relatively inexperienced female cyber-security agent, Tamar Rabinyan (Niv Sultan), who is sent on an IDF undercover mission to Iran to sabotage the national electricity grid. True to the conventions of the genre the series is packed with action sequences and plot twists; the mission goes wrong, and Tamar finds herself exposed and alone in Tehran, on the run from the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence. The plot subsequently develops into a web of betrayals and deceptions in both the Israeli and the Iranian intelligence organisations.

In terms of the series’ verisimilitude such a plotline evokes both the actualities of historical events and the militarised discourse that dominates the geo-political relations around nuclear power in the Middle East. More specifically, it references the shadow war Israel has been conducting in recent years against Iranian nuclear targets, through small-scale operations of espionage, targeted assassinations, sabotage and cyber-attacks, for which it has never formally claimed responsibility (Bergman and Kingsley Citation2021). The series’ intensified verisimilitude was revealed most vividly in April 2021, a few months after the series’ release. As if taking its cue from the fictional narrative, Israel was reported to confirm for the first time claims that it was behind a cyber-attack on Iran’s main nuclear facility Natanz, where a large-scale blackout apparently damaged the electricity grid at the site (Chulov Citation2021 and see also; Harel Citation2021). Referring to the proximity of the actual events to the fiction in Tehran, Zonder, the series’ writer and creator, said in an interview to the New York Times, ‘It was a bombing, and then an episode in our show, and then another bombing, and it kept going like this … Everyone reacted and said, “Oh, Tamar Rabinyan is working!”’ (Kamin Citation2020).

However, while the espionage mission provides the arch for the action plot, deeper layers of the narrative and the visual representation point to the series’ central aim: to ‘counter Iran’s negative image as a country whose sole goal is to destroy Israel’, as Zonder put it in an interview to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz (Stern Citation2020). Indeed, the series’ representation of the city space of Tehran and of Iranian society is largely nuanced compared to dominant portrayals of Iran in Israeli (and Western) media, which tend to present it via dichotomies of good and bad, us and them, and within paradigms of threat and alienation.

The series opens, somewhat misleadingly, by conjuring up the stereotypical and demonised image of Iran through the Israeli paranoic gaze, and by so doing sets up the worldview which it subsequently aims to challenge. For example, the first image of the city itself, seen through the eyes of Tamar, is a public execution taking place in one of the main squares (See ). The crude image validates one of the common Western stereotypes of the Ayatollah’s regime, and the casual manner with which the taxi driver refers to it gives the impression that sights of such executions are routine occasions in the city.

Yet, as the narrative develops and Tamar gradually immerses herself in the life of the city and its residents, a different image is revealed. In contrast with dominant representations of Iran in Western and Israeli media, Tehran is depicted in the series as a vibrant and pleasant city and, importantly, urban, secular and modern. Apart from the women wearing headscarves in public spaces, religion and religious practices are hardly seen to play a role in the life of the characters or in the public sphere of the city and the azan (call to prayer), so often used as a symbol of an Islamic city (Champion Citation2016), is missing from the city soundscape.

The series is also nuanced in its characterisation of Iranian protagonists, primarily Iranian agent Faraz Kamali (Shaun Toub) and Tamar’s ‘asset’ Milad (Shervin Alenabi), a young anti-regime activist. Despite being the representative of the (so-called) enemy, and in contrast to many political thrillers, Kamali’s personal life and internal conflict form a meaningful part of the narrative. Rather than confirming the stereotype of Islamic Republic officials as religious hardliners, Kamali is depicted as a secular national patriot, a man of principles who recalls the ideological spirit of the early years after the Revolution. His humanity and integrity are demonstrated, amongst other things, through the relationship with his wife, Naahid (Shila Ommi). The portrayal of their relationship exposes us to moments of intimacy, expressive use of affectionate language and mannerisms associated with the middle-class secular strata of society with its European affiliations and private subversions of the Islamic regime. These include, for example, Naahid’s avid consumption of Turkish television dramas that are very popular in contemporary Iran and are available only on satellite TV (officially forbidden by the state), or the popular pop song Age Ye Ruz (If One Day aka Occupation of the Heart, 1977) by Faramaz Aslani, that the couple share in a pivotal moment of the plot. Age Ye Ruz is one of the most recognizable and cherished Iranian love songs, and considered illegal as Aslani fled the country after the Revolution.

Milad is a young hacker and anti-regime activist that Tamar initially uses as a contact to help her break into the national electricity grid and later becomes involved with romantically. Through Milad and Tamar’s developing love story, the viewers are exposed to the socio-political struggle of young activists in Iran and to what Zonder described as Tehran’s underground avant-garde scene: ‘thriving, with lots of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll’ (Stern Citation2020). Milad and his friends represent the main stratum that formed the Green Movement that emerged following the disputed presidential election in 2009. They belong to a milieu which is predominantly middle class, intellectual, and cosmopolitan. They are fluent in English, au fait with foreign cultures, and have an outward and transnational outlook on life. While this stratum of the Iranian society is rarely depicted candidly in Iranian cinema it has been the focus of recent Iranian films reaching international circuits such as Automic Heart Mother (Madar-e Ghalb-e Atomi, Ali Ahmadzadeh, 2015) or the notable films of Asghar Farhadi Fireworks Wednesday (Chahārshanbeh Suri, 2006), A Separation (Jodāyi-ye Nāder az Simin, 2011) and Salesman (Forushande, 2016).

Such nuanced representations of Iran reflect the creators’ self-proclaimed mission to reproduce an ‘authentic image’ of the country and the unprecedented financial investment that went into this aspect of the production. While, in general, recent political thrillers tend towards greater verisimilitude of the places and cultures they depict, in the case of Tehran, the importance placed by the creators on ‘authenticity’ (of Iran, less so of Israel or the military mission) and the extent to which this was achieved is at the core of the series’ political agenda.

According to Dana Hermon, the series producer and co-creator, Tehran was based on extensive research with geopolitical and cultural experts on Iran. Diasporic Iranian advisors were employed to oversee the authenticity of the set design and use of Persian throughout the production (Kudner Citation2020, and see also interview with the director Dani Sirkin in; Shavit Citation2020). The cast included native Persian-speaking diasporic Iranian actors, such as the renown Iranian-American actors Navid Negahban and Shaun Toub and the UK-based Iranian actor Shervin Alenabi, as well as Israeli actors of Iranian (Jewish) origin Liraz Charhi and Esti Yerushalmi. The director, Dani Sirkin, and other members of the cast, including the lead actor Niv Sultan who played Tamar, studied Persian for the production. As in the case of Fauda, authentic and accurate use of the ‘Other’s’ language – in this case Persian – was a key objective and a signifier, in the creators’ mind as well as in the reception space, of the series’ complex representation of the Other. Moreover, the emphasis on the use of Persian and the collaboration with diasporic Iranians during the production was framed, by the creators, as another signifier of the series’ transnationality. In an interview to the news agency AFP, Zonder proclaimed that he likes to think about Tehran as ‘at least a cultural [Iranian-Israeli] co-production’. ‘We speak more Farsi than Hebrew in “Tehran” … so to a certain extent, I would like to think that it is an Israeli-Iranian series, although officially it is not,’ he said (Vardi Citation2020).

As location filming in Tehran itself was not possible (Israel and Iran do not have diplomatic relations) the series was filmed in Athens. Great attention was given to the set design attempting to create a close impression of the city. In many action driving shots, archival footage of contemporary Tehran was intercut with carefully framed close-ups of both interior action and exterior shots of the moving car. Detailed attention was paid to indexical signs such as clothing, street signs, the type of cars that are common in contemporary Tehran, street vendors and street food typically found in main squares, posters, public telephone booths, and the iconic blue and yellow charity boxes collecting donations for the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation.Footnote7

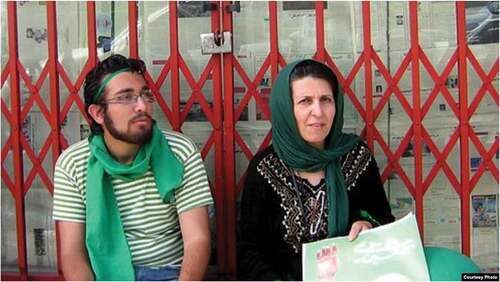

Subtle references to actual events, figures and popular culture are peppered throughout the series and cement its claim to authenticity. Milad’s physical appearance, for example, evokes the image of Sohrab Arabi, one of the iconic figures of the Green Movement (See ). Sohrab Arabi and Neda Agha Sultan were two young activists who were killed in the June protests in 2009 and came to symbolise in Iranian popular memory martyrdom, heroism, and the sacrifice of the youth. The final photograph of Sohrab with his mother wearing the green headband and scarf, in support of the Green Movement, became a symbolic reference to the movement. The resemblance between this image and Milad is illustrated in the figures below.

Figure 2. Sohrab Arabi and his mother, campaigning for Mir Hossein Mousavi. He was later found shot dead. Source: Persian Letters.

Another reference is made to what has been dubbed ‘The girls of Engelab/Revolution Street’, which symbolises the peaceful women’s protest that ensued from 2009 against religious coercion and control. The image refers to an incident where a girl took off her white scarf in protest against mandatory hijabs, while standing on an electrical box on Engelab/Revolution Street (). Starting as a digital campaign by the popular journalist Masih Alinejad in 2014, called My Stealthy Freedom Facebook page, the campaign moved physically to the streets of Tehran in 2016.

Although the image of Iran that the series presents certainly counters dominant misrepresentations and common misconceptions about Iran in Israel and in the West, it is important to note that it privileges a particular stratum of Iranian society and a specific image of Tehran that resonates with Western(ised) perspectives. In their attempt to de-Other – or ‘humanise’ as some reviews of the series put it – Iranian society, the series’ creators draw on ‘politics of sameness’ rather than more complex forms of empathy and affiliation that recognise and respect difference. The focus on the young anti-regime activists and their representation speaks to transnational sensibilities for struggles against oppression around the world and was aimed, very consciously, at drawing draw parallels with the same generation in Israel, not only in relation to the lifestyle and the rave culture depicted (popular amongst Israeli youth) but also in relation to recent socio-economic unrest and political protests that were led by Israeli activist youth in recent years. The depiction of Tehran’s modernity and the portrayal of Kamali and his wife equally aim to speak to Israeli Western imaginaries, marking Iranian society as Western (rather than Arab or Islamic) – and therefore, by implication, ‘like us’. However, where the series’ attempts to challenge the notion of Iran’s alterity does become more complex is around its critique of Israel’s dominant Zionist discourse, more specifically in its engagement with Israel’s internal identity crisis.

The Iranian Jews – fluid identities and subversion

In his study of Israel’s relationship with Iran, the historian Haggai Ram posits that while Israeli anxieties about Iran relate to legitimate geo-political and strategic concerns, the magnified scale of the threat, and the consequential construction of Iran as Israel’s radical Other, should also be understood as a reflection of Israel’s domestic crisis around its national identity and the ‘contradiction and failures’ of its project of ‘Euro-modernity’ (2009, 16). The domestic crisis that Ram (Citation2009) refers to revolves around the internal conflict between Israel’s self-perception as part of European modernity, despite its Middle Eastern geographical position and the cultural heritage of most of its population.

Tehran, we suggest, echoes this scholarly assertion. While the generic action-based plot seemingly presents a geo-political conflict over nuclear power, the details of the narrative engage, in fact, with Israel’s internal identity crisis. It does so by placing at its centre Iranian Jews. The series’ lead character – Tamar – and her operator agent Yael Kadosh (Liraz Charhi) are both, as it transpires in pivotal moments of the plot, Iranian Jews who migrated to Israel when young. Their experience of migration and the hybrid position they occupy are both key to the inciting events that propel the action plot forward and, on a thematic level, carry the series’ central message. Tamar, Yael, and Mordechai (Tamar’s father) embody and articulate in different moments not only the hybrid positionality that is often associated with the experience of migration, but also a specific ambivalent relationship with Israel’s dominant Zionist ideology and its militarist culture.

In her seminal critique of Zionism, Ella Shohat asserts that the ambivalence of the Zionist discourse around the Mizrahim (Jews originating from the MENA area) and their construction as ‘Others- within’ the Israeli national body constituted in turn a Mizrahi split subject position (Shohat Citation2006). According to Ram, in the case of Iranian Jewry, unlike Jews from the Arab Middle East, the notions of ‘exile’ and ‘homeland,’ and ‘East’ and ‘West,’ are not binary oppositions that came into conflict with each other, but rather ‘appear fluid, overlapping, and contingent’ (2009, 38).

Ram asserts:

Iranian Jewry did not, and indeed could not, fall neatly within any stable Zionist ethnic or cultural categories, hence confounding the most fundamental Zionist convictions embodied in the notion of the ‘ingathering of exiles’. To the extent that these Jews were unclassifiable in Israeli imagination, they brought to the fore—perhaps more than any other Jewish ‘diaspora’— the double-edged Zionist colonial imagination of inclusion and exclusion, of desire and anxiety, to which modern Jewish identity is (still) indebted. (ibid.)

Similarly, in his recent study of the development of the Jewish community in Iran, Lior Sternfeld (Citation2019) points to the unique fluidity of subject positions and socio-political affiliations amongst Iranian Jewry. In contrast to dominant Zionist historiography – which narrated the experience of Iranian Jews (and other Middle Eastern Jews) as a story of persecution akin to the experiences of European Jewry – Sternfeld’s research found that during the long history of Jewish presence in Iran (estimated at around 2700 years), Jews were not singled out more than any other religious minority, either positively or negatively. During the Pahlavi rule in the first part of the 20th century, the reshaping of Iran as a secular Western modernity and the return to Persian roots enabled Iranian Jews to claim older and greater belonging to the nation and to experience both prosperity and greater integration into the wider society. Political and ideological affiliations amongst the Jewish population during those years tended to correlate with that of the non-Jewish Iranian society. As in other places across the world, the communist party (Tudeh), with its ideology of inclusion, was particularly attractive to many Jews. Zionism was perceived as one of several radical political alternatives and responses and interpretations of it varied considerably between different Jewish groups. Importantly, support for the ideal of Jewish nationalism did not necessarily translate to support for immigration to Israel (Alia) and, crucially, was not perceived as replacing or contradicting sentiments of Iranian nationalism or assimilation into Iranian society. As Sternfeld put it, ‘a young Jew in Tehran at this time [mid 20th century] could be simultaneously considered an Iranian patriot, an avowed Tudehi, and a wholehearted Zionist’ (2019, 65).

Significantly, such hybrid identity positions were not particular to Jews but reflected the wider socio-political environment in Iran and how Iranian national identity has been shaped and understood over time. Scholars such as Afshin Matin-Asgari (Citation2012) and Jalal Khaleqi-Motlaq show that definitions of Iranian identity since the ancient period were inclusive and did not denote ethnicity or religious affiliation (Amanat and Vejdani Citation2012). The modern nation-building project of Reza Shah drew on these ancient Persian roots in its articulation of the inclusivity of Iranian identity and its emphasis on distinguishing Iran from the Arab Middle East (Aghaie and Marashi Citation2014).

According to Sternfeld (Citation2019), a (paradoxical) testament to the success of Reza Shah’s nation-building project could be found in the involvement of Jews in the revolution of 1978, which despite the benefits they saw under the Pahlavi rule were not overwhelmingly in support of the continuation of the monarchy. In the post-revolution period, the definition and boundaries of the Iranian nation were again under transformation. While the uncertainty that followed drove some Jews to leave (temporarily in many cases) for Israel or the US, the Jewish leadership were keen to take an active role in shaping the new national ideals under the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), not least in securing the rights of minorities and their integrated position. Indeed, some level of inclusivity which corresponds to the ethnic and religious heterogeneity of Iranian society was maintained even under the Islamic Republic rule.Footnote8 The major challenge for the Jews under the IRI was, and remains, maintaining a clear separation between Zionism and Judaism. The IRI leadership, starting with Ayatollah Khomeini several months after the revolution, has declaratively acknowledged that ‘the Jews of Iran are not Zionist’ and a discursive separation between the two terms is still dominant in the official public discourse. Yet, this remains an area of contestation for Iranian Jews who are, on occasion, suspected of collaborating with Israel and its Zionist regime and must ‘prove’ their loyalty to the Iranian nation.

The series, as we indicated above, renders these suppressed histories visible, pointing both to Iranian-Jewry’s fractured relationship with Zionism and their sense of belonging to Iran. Moreover, the hybrid identity position of its key characters serves as a narrative device that subverts and undermines the IDF mission and, by extension, the premise of the Israeli-Iranian conflict at large.

Tamar’s family story, which is revealed incrementally during the series, aims to epitomise the story of Iranian Jewry at large, featuring a family that was split by different reactions to the establishment of IRI: Tamar’s nuclear family that migrated to Israel and Tamar’s aunt Arezoo (Esti Yerushalmi) who married an Iranian Muslim and remained in Iran. When Tamar’s cover is blown and she’s on the run from the Iranian intelligence, she turns to her estranged aunt, who reluctantly offers her shelter. The reunion with her family, the re-encounter with Iranian society and the developing romantic relationship with Milad throw Tamar off the course of her military mission. The longer she stays in Iran, the more she becomes consumed by moral dilemmas and questions of loyalty, and she ultimately deserts the mission altogether. As Dana Eden, the series producer explains in a podcast interview with Haaretz, the central element in writing Tamar’s character was her experience of migration: “She is coming home … in Israel she really tried to fit in, to be part of the Israeli ethos, to become a ‘warrior’, but as soon as she arrived back home something in her ‘unsettles’ (Kudner Citation2020). Indeed, if Tamar seems at the beginning of the series to be modelled on the image of the kick-ass female Mossad agent that dominates many American and Israeli screen representations, she is revealed with the progression of the narrative to be gentler and conscientious.

The characterisation of Tamar, the female Mizrahi agent, breaks away from dominant Israeli screen representations of women in combative roles. By and large Israeli cinema and television dramas tend to engage with narratives of Israel’s national conflicts predominantly through the gaze of Ashkenazi (European) masculinity, constructed often as the normative identity that epitomises the national body. When women are seen in military or espionage roles – such as the characters of Nurit (Rona-Lee Shim’on) in Fauda or Dana in POW – they are rarely lead characters and tend to exhibit prowess and toughness associated with masculinity. The tenderness and fragile femininity that Tamar reveals is more attuned with the evolving tropes of the transnational 21st-century political thriller and crime drama genres. Her characterisation echoes previous fictional female investigators that combine professional toughness and emotional vulnerability (Steenberg and Tasker Citation2015). Tamar’s moral ambiguity and emotional complexity resonates with Homeland’s main character Carrie Maddison (Claire Danes), but unlike Carrie, whose emotional complexity is framed within her individual psychology as bi-polar, Tamar’s source of moral ambiguity is tied to the complexities of Israeli national identity and forms of Zionist cultural oppression.

Similarly, Yael, who moves seamlessly between her Israeli and Iranian identities, is revealed at the end of the series to betray the military mission (and by extension Israel). Although she exhibits little of the fragility that we see in Tamar, here as well the narrative leads us to interpret the motivation for the betrayal to be rooted in her hybrid identity position and her sense of (cultural) belonging to Iran.

Tamar’s father, Mordechai Rabinyan, who represents the generation that lived through the Pahlavi era, articulates the fractured relationship with Zionism more explicitly. In one of the most poignant scenes of the series, Mordechai is held hostage in Turkey by Kamali, as a burgeoning chip in his negotiations with the Israeli forces. Despite the brutality of the hostage situation, the dialogue between the two men, whom are of a similar generation, is surprisingly reciprocal – eliciting empathy rather than hostility in them both. Speaking to each other as contemporaneous countrymen, the conversation that unfolds reveals some of the fluidity and inclusivity of Iranian national identity and evokes an image of a better, kinder Iran that existed before the revolution. When the conversation moves to the topic of Mordechai’s immigration to Israel, Mordechai impresses upon Kamali the difficulties he and his wife had in assimilating to Israel, ‘away’, as he puts it, ‘from our precious country’. Responding to Kamali’s question ‘why did you leave anyway?’, Mordechai says:

It was my dream to come to the Holy Land, to go to Jerusalem, pray at the Western Wall. When I went to Jerusalem for the first time and saw the sacred wall and the walls the Muslims built, I burst into tears … I’m like in exile there. The longing for Iran grows stronger every year. You don’t know how hard it was.

Mordechai’s account and the emphasis he puts on religious sentiments rather than Zionist-national motives refutes the Zionist myth of a Jewish nation, its dominant narrative of worldwide (and perpetual) persecution of Jews, and its imaginary notion of ‘ingathering of exiles’ in the land of Israel. Here as well, Mordechai’s hybridity as an Iranian-Jew acts as the narrative device that diffuses the conflict. His expression of love and longing for Iran strikes a chord with Kamali’s patriotism and ideological sentiments and he spares Mordechai, letting him go at his own peril. Kamali’s final act of compassion towards Mordechai is another marker of his characterisation as conscientious and humane and stands in contrast to the cold brutality with which the actions of the Israeli security forces are represented.

It is worth noting that while Yael, Mordehai and Tamar, the Israeli-Iranian migrants, are afforded a kind of hybrid agency that diffuses the conflict, Arezoo, the Iranian Jew who remained in Iran after the 1979 revolution, is denied both agency and visibility. The depiction of Arezoo as a Muslim convert forced to live a lie falls back onto the simplistic and stereotypical image of the IRI’s oppression and obscures both the continuation of Jewish life in Iran after the revolution and the complexity and heterogeneity that is embedded in Iranian national identity, even under the IRI. Moreover, as Lior Sternfeld claimed in an interview in Haaretz, showing Arezoo giving shelter to her niece, a Zionist agent, runs the risk of reaffirming stereotypical suspicions that prevail in Iranian popular discourse about Iranian-Jews’ loyalty to Israel rather than to Iran (Aderet Citation2020). Such a portrayal undermines the delicate separation between Judaism and Zionism, which is so hard to maintain in Iranian public discourse as well as elsewhere.

Finally, the series’ first season ends with the ultimate failure of the Israel mission. Defying clear instructions from her commanders, Tamar saves Milad from being killed by a Mossad operator, and the final sequence ends on a cliff-hanger showing the two lovers escaping on his motorbike onto the dark road. Such an ending suggests a fantasy of a new future for both societies resting on an alliance of the younger generation, who share transnational sensibilities and affiliations despite being on opposite sides of the national conflict. Although the series may well develop in a different direction in its second season (yet to be released at the time of writing) by offering an imaginary path towards a different future, Tehran breaks with the recent tendency of Israeli political thrillers, including the popular Fauda and POW, to depict Israeli society as caught up in a perpetual cycle of conflict rife with moral ambiguities but with no ‘way out’ in sight.

If the symmetry in the representation of the state apparatus in both countries (as they are manifested in the actions of both security services), the familiarity that comes with the depiction of Iran’s modernity (deemed Western), and the links drawn between the youth, ‘de-Other’ Iran by provoking the viewers to think about the similarities between the two societies, the hybridity and fluidity of identity embodied by the main characters offers a more radical proposition by collapsing the distinction between the two altogether. Ultimately, the series critique could be read as a challenge to the prevailing perception of Iran as the hostile enemy and Israel’s self-perception as a peace-seeking nation as well as an attempt to destabilise the Zionist myth of a distinct and unified Israeli-Jewish identity. For the more informed viewers it can evoke historic political and ideological alliances (if secretive) between Israel and Iran during the Pahlavi era (and beyond), which rested on the mutual positionality of both countries as outsiders within the otherwise Arab Middle East.

The critique offered in the series speaks to critical voices on the Israeli left, which have been challenging Zionist hegemonic notions for several decades now – in academia and in the arts – despite the country’s overall popular shift to the right. The series’ provocation to rethink the relationship between Israel and Iran and the self-examination of Israel’s own forms of oppression, and aggression, is thus critical, yet by no means a radical message that would be excluded from the Israeli public sphere. Rather, in the contemporary phase of Israel’s internal cultural wars such a provocation was largely discounted in the Israeli reception space.

Tehran’s reception: between entertainment and politics; between the national and the transnational

The airing of Tehran on Israeli national television was accompanied by an extensive promotional campaign by Kan that included posters, promos, interviews with the creators and cast, teasers, and considerable ‘buzz’ on social media. These promotional paratexts highlight in different ways the series’ provocative suggestion of ‘de-Othering’ Iran, thus foregrounding the series’ political elements. One of the most overt examples was the promotional slogan for the series, which read: ‘Tehran is Here’ (Tehran ze Kan), playing on the double meaning of the broadcaster’s name – Kan – and the meaning of the word in Hebrew – ‘here’.

However, a survey of reviews in Israeli media reveals that much of the discussion within the reviews (and on social media) focused on the series’ generic tropes and revolved around the plausibility of the espionage mission. While the series was praised for its high production values and for the lucrative deal with Apple TV – marking yet another milestone in the international success story of Israeli television – it was primarily criticised for its lack of credibility. Comparing Tehran with Fauda or Homeland, reviewers and commentators were concerned with details of the action plot that were deemed unbelievable, such as Tamar’s behaviour as an undercover agent or lack of credible suspicion and/or brutality on the part of Iranian security forces. These ‘holes in the plot’, as they were often dubbed, were seen by some to undermine both the credibility of the series as a whole and the thrill effect of the genre. In most cases, the political critique that was embedded in the series – either its attempt to ‘de-Other’ Iran or its commentary on Israeli identity – did not generate any meaningful discussion.Footnote9 When noted by reviewers, it was mainly mentioned in relation to its hindering effect on the thrill factor that was expected from the genre.

For example, in his review in the popular Walla Culture website, Ido Yeshaio writes:

There is considerable anthropological value in a series that takes place in Iran, especially if seen through Israeli eyes, but in the parts that are recognisable to us [Israeli viewers] too many things in Tehran seem uncredible, including reasonable human behaviour. It turns anything else – the life in the city and the Iranian characters it depicts – to a fairytale, where what is probable and what is not becomes questionable … It seems that the series is so caught up in the story it is trying to tell – that deals also with Tamar’s family, a local hacker that she gets to know and his anti-regime friends – that it is ‘stuck in second gear’ even at moments that are meant to be thrilling. (our translation, Yeshaio Citation2020; see also Shalev Citation2020)

Adrian Hennigan’s critique of the series’ lack of credibility reveals the extent to which the creators’ intended production of authenticity was misread at times. Addressing the series’ representation of Iran, Hennigan writes:

The biggest problem for me … is that I never truly believed I was watching something set on the streets of Tehran … I’ve seen places in Israel with more of an Islamic vibe than the Tehran presented here, which feels pretty much like any large Western city. Yes, I’m sure you can find the occasional skateboarder on the Iranian capital’s streets, but I’m also sure there are plenty of modesty police who might have something to say about an unmarried young couple walking together, let alone kissing, in the park. (Hennigan Citation2020)

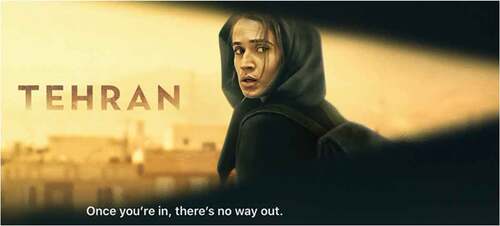

The international release of Tehran on Apple TV + revealed a somewhat reversed situation. Unlike the promotional campaign in Israel, Apple TV’s paratextual material primarily foregrounded the action and the thrill elements of the series and, as seen in the , promoted the series on its platform with the tagline: ‘Once you’re in, there’s no way out’. Presumably deemed to strike a chord of familiarity with international audiences, such imagery and tagline reverts to the orientalist stereotypical image of Iran as an Islamic threatening ‘Other’, in contrast with the series’ political agenda.

Despite this, many of the reviews that we surveyed in the English-speaking media did highlight the series’ political message, praising it as novel for offering a more humanised or complex image of Iran, or for its attempt to present an even-handed account of the Israeli-Iranian conflict by avoiding a simplistic representation of ‘good versus bad’, with some seeing it as an act of ‘Israelis reaching out to their enemy’ (See for example Mark Citation2020).

Critical reviews attuned to wider critique of Zionism and Israeli colonialism labelled the series as nostalgic and/or Orientalist in its depiction of the IRI. For example, Daniel D’Addario’s review in Variety argued that the series’ focus on Iranian Jews was nostalgic, reminiscing on a better bygone Iran that existed before the Islamic revolution, and that its depiction of contemporary Iran was ‘uncomplicated’ and adhering to American prejudices (D’Addario Citation2020). In another example, Belen Fernandez argues in her review in Middle East Eye that the series’ Orientalist approach is exposed by the privileging of a particular strata of Iranian society. Despite the creators’ claim to represent contemporary Iran realistically, Fernandez says: ‘In the end, after all, the creators of Tehran aren’t really interested in legitimising pro-government Iranians; there is a specific cohort that is deemed worthy of legitimisation and promotion to the frontlines of Iranian identity.’ (Fernandez Citation2020).

In Iran, Tehran attracted some media attention in official Iranian media as soon as its production was announced, and was subsequently available for viewing (as early as its general release worldwide) through unofficial satellite services.Footnote10 In general, Iranian media tends to cover any foreign film or television production that directly depicts Iran. The Iranian state, and right-leaning media, have always been suspicious of any foreign media that offers also Persian language content, let alone an entertaining TV series produced by Israel. Such foreign films and programmes, or foreign media networks in general, are often presented as agents in the ‘soft war’ led by superpowers such as United Kingdom or United States (and/or Israel) against Iran, whose sole purpose is corrupting the Iranian people and coaxing them to oppose the state (See Blout Citation2015; Sreberny and Khiabany Citation2021).

In this vein, Tehran was referred to from the onset as a product of Zionist propaganda, and the focus of the critique was placed on the positive representation of anti-regime activism. The conservative Iranian newspaper Keyhan, for example, published an article announcing that the Zionist regime produced a series about the seditionists in Iran, the term which was most used to describe those affiliated with the Green Movement in 2009 (Kayhan Article Citation2020). Similarly, the online publication Hamshahri suggested the series demonstrates yet more evidence of the connection between the Zionist regime and the 2009 seditionist movement (Hamshahri Article Citation2020). Other reviews that engaged more with the text itself tended to ridicule the series for its attempt to represent Iran realistically. For example, Mashregh News, called the series an action-comedy, praising the series’ production value but at the same time mocking errors in its depiction of Tehran, such as the street signs from the Apple TV + trailer, where the wrong Persian term for street is used.Footnote11 Using overt sarcasm throughout, a review in Young Journalist Club (YJC) recommended that Iranian viewers watch the programme for the sheer enjoyment of ‘the funny stunts Israel has tried to pull off’. It continues to ridicule the depiction of Iran as a horrifying place (seen in episode one), ‘the amateurish way’ some of events of the plot are constructed, and the attempt to connect with Iranian viewers by using Persian. It concludes by citing a tweet by culture and media expert Saeed Elahi, who claimed that the series is lacking research in its attempt to depict Iran realistically, and sarcastically mocking the creators by saying, ‘from Mossad, which claims to be involved in the explosion of the Natanz facility one expects better cultural product. If you had left it to your spies in Iran they would have made a better piece of work.’ (Youth Citation2020). Other reviews, which did approvingly nod to some aspects of the series – such as the set design that depicts Tehran – have ultimately ridiculed its attempt to represent the people of Iran. For example, a review in Hamshahri online states ‘[while] the costume designs can positively surprise the viewer to an extent, the way in which the citizens of Tehran relate to each other, especially the university students’ interaction, is more humorous than real’.Footnote12 Thus, although official media largely reviewed the series within the confinement of the accepted paradigm, the recurring reference to the series as humorous, comedic, or funny could be read as a deflating strategy, as the series does not easily lend itself to an anti-Iran message and therefore is harder to villainise in the usual manner.

While the reviews we surveyed by no means form an exhaustive list nor a systematic study of the series’ reception, we suggest that the differences between the reviews inside Israel, in Iran, and in the Anglo-American world point to the complex relationship between the entertainment and politics that typifies the political thriller genre. These complex relationships are played out in uneven ways across national and transnational reception spaces, and draw attention to the inverse relationship that operate at times between marketing and critical reception. As the survey of the review demonstrates, the more complex and coded political critique that is embedded in the series’ engagement with Israeli national identity and its militarist culture was largely lost both in the national and the transnational reception space. The series’ political agenda to produce a more positive and more ‘authentic’ representation of Iran was acknowledged but largely dismissed by Israeli and Iranian critics, albeit for different reasons at times.

Instead, it reverberated in the transnational exhibition space. Despite the curatorial framing of the series as entertainment – foregrounding the generic action and thrill elements – in the transnational exhibition space, the series was accredited with a certain political agency that was absent from the national context. Anglo-American critics couched it as an exhibition of Israeli well-meaning gesture to ‘humanise’ its enemy and as a call for peace. The same message was reiterated by the series’ creators on different international stages, including at the acceptance speech of the Emmy award, when the series’ executive producer Dana Eden proclaimed ‘Tehran is not only an espionage series, it’s also about understanding the human behind your enemy … I think it gives a hope for the future, and I hope that we can walk together – the Iranians and the Israelis – in Jerusalem, and in Tehran, as friends and not as enemies.’ (Spiro Citation2021).

To conclude, as a case study of transnational political thrillers Tehran demonstrates the complex and shifting relationship at play between the entertainment and the political elements, which are intrinsic to the genre and to its global travel. The formal generic elements, deemed universal by the global media gatekeepers, were the key factors that enabled the programme to travel in the first place and were central to the paratextual framing of the series by the Apple TV. In many ways, the transnational poisoning of Tehran rested upon, and benefited from, the recent global prominence of Israeli political thrillers, most notably Fauda, and their framing as entertainment. At the same time, as we hope our discussion has demonstrated, politics was central to the series not only in forming the setting and the dramatic conflict of the narrative but also in relation to the political agenda that underscored its production. As articulated clearly by the creators, their aim in making the series stretched beyond notions of sheer entertainment to the realm of political advocacy. Seeking to challenge prominent perceptions of Iran’s alterity, and to critically reflect on Israel’s own forms of oppression and militarist culture, the creators position the series as a political text that s addresses national audiences, looking (or hoping) to influence public opinion both in Israel and in Iran. Yet, critical reception both in Israeli and Iranian media seems to have undermine the series’ radical potential, either by dismissing it or belittling it, reading it primarily within entrenched political paradigms. In the international reception space reviews did nod to the series’ political gesture towards reconciliation, but similarly hardly engaged with its more subversive and coded critique of Israeli identity and culture. At least in the way it manifested itself in the Anglo-American media, and in prestigious events such as the Emmy Award ceremony, the subtle critique towards Israeli forms of oppression and aggression, that are rooted in the specificities of Zionist history, was by and large diluted to a-political well-meaning ‘call for peace’ that adheres to tropes of universal humanism. Such a message, coming from an Israeli production, seems to reenforce dominant perceptions of Israel in the West, which tend to align it with (so-called) enlightened Western democracies and positions it, in the wider context of Middle East geo-politics, as the peace-seeking party rather than the aggressor. Regardless of the critical intentions of the series’ creators, and despite the critique within the text itself, such a message works also to the advantage of the Israeli state in its competitive struggle to win international legitimacy. As Nye suggested, now more than ever global politics involves ‘verbal fighting’ among competing narratives (2011, 87). Culture is often used as tool of soft power by states (and other agencies) to circulate ideas and ideals that are deemed attractive to targeted circles of influence (84). The narrative of Israel as a liberal Western democracy has always been key to Israeli state diplomacy in the West, and a core idea/l that legitimises its presence (if not actions) in the Middle East. One of the ways in which this idea is circulated is through the embracement, in the Western reception space, of leftist Israeli films that contain different levels of critique of the state (as long as they are made by Israeli-Jews). The ability of the Israeli state to embrace these critical films is marked as a sign of its liberalism and openness. Similar dynamic was at work in the case of Tehran. At the same time that the Israeli state was engaged with an escalating ‘shadow war’ with Iran, its foreign office was embracing the series, for example by including on its official website a link to the series and a tweet feed in Persian that was seeking responses from Iranian viewers.Footnote13 Paratexts such as reviews, marketing and curation strategies are no doubt instrumental to the way audiences understand and decode films and television programmes. Yet, meaning, constantly at flux, is also contingent on individual viewers’ background and positionality. The complex reception of Tehran by reviewers that was outlined in this article, invites further audience study to assess how it was understood by both national and transnational audiences, and the extent to which it was successful in challenging stereotypes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yael Friedman

Yael Friedma is a Principal Lecturer in Film Studies and Film Practice in the School of Film, Media and Communication, at University of Portsmouth. She has studied Israeli and Palestinian cinema within the framework of transnational cinemas since she completed her PhD. on the topic of Palestinian filmmaking in Israel in 2010. Her publications on the topic include: ‘Guises of transnationalism in Israel/ Palestine: a few notes on 5 Broken Cameras’, (2015) Transnational Cinemas, 6:1, 17-32 and ‘Israeli Animation Between Escapism and Subversion’ in Stefanie Van de Peer (ed.) (2017) Animation in the Middle East: Practice and Aesthetic from Baghdad to Casablanca, London: I.B Tauris. She is currently completing a monograph on Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel for I.B Tauris, Bloomsbury (forthcoming, 2023).

Maryam Ghorbankarimi

Maryam Ghorbankarimi is lecturer in film studies at Lancaster University. She has completed her PhD in film studies at the University of Edinburgh in 2012 and her dissertation was published as a book in 2015 entitled A Colourful Presence; The Evolution of Women’s Representation in Iranian Cinema. Her current research is on transnational cinema and culture, specifically the representation of gender and sexuality in Middle Eastern cinema. Her edited volume on seminal Iranian filmmaker Rakhshan Banietemad, ReFocus: The Works of Rakhshan Banietemad was published in spring 2021. Maryam is also a filmmaker; she has made some award-winning short films in both short documentary and fiction formats.

Notes

1. Other titles include: Sleeper Cell (Showtime, 2005–2006), The Unit (CBS, 2006–2009), Traveler (ABC, 2007), Burn Notice (USA Network, 2007–2013), Nikita (CW, 2010–2013), The Blacklist (NBC, 2013–), The Americans (FX, 2013–2018), Berlin Station (Epix, 2016–2019), Rubicon (AMC, 2010), Person of Interest (CBS, 2011–2016), Homeland (Showtime, 2011–2020), Scandal (ABC, 2012–2018), House of Cards (Netflix, 2013–2018), Quantico (ABC, 2015–2018), Designated Survivor (ABC, 2016–2018), or Shooter (USA Network, 2016–2018).

2. Netflix is, to date, the most prominent example both in terms of its outreach and size of its global market and the level of investment in local productions. In her recent analysis of Netflix’s programme commissioning, Amanda Lotz found that 58% of Netflix’s co/commissions originated from outside of the US, indicating in her view ‘that multinational commissioning is not simply lip service, but can be regarded as a core strategy of the service’ (2021, 202).

3. Alongside popular European series such as Spooks (BBC, 2002–2011), Bodyguard (BBC, 2018), The Bureau (Le bureau des legends, Canal +, 2015-), Borgen (DR, 2010–2013) and Occupied (Okkupert, TV2, 2015–2019) recent international titles include series and films such as the South Korean Iris (Airiseu, KBS2 2009–2013); the Turkish The Valley of the Wolves (Kurtlar Vadisi, 2003–2005); the Indian Bard of Blood (Netflix, 2019-); South African first Netflix Original production Queen Sono (2020-); the Australian production Secret City (Foxtel, 2016); the Egyptian espionage film Escaping Tel Aviv (Welad el-Amm, Egypt, 2009) and the popular Lebanese thriller Al Hayba (MBC, 2017-).

4. For scholarly work see for example (Gertz and Yosef Citation2017; Jamal and Lavie Citation2020; Lavie and Jamal Citation2019; Munk Citation2019; Ribke Citation2019; Nir Citation2019; Zanger Citation2015).

5. See the series producer Shula Spigel account in https://www.calcalist.co.il/consumer/articles/0,7340,L-3847473,00.html.

6. Kan’s investment in the production of the first series amounted to around 8.5 million shekels (just under 2 million GBP), with an estimated cost of £300,000 per episode. Source: https://www.ynet.co.il/entertainment/article/rkT80Oe0L.

7. Introduced in 1979 after the Revolution to collect donations for the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, these charity boxes are a distinct marker of Iran and appear (somewhat excessively) in almost every exterior shot of the city.

8. Moreover, over the four decades of the IRI, Iranian nationality is still a subject of debate and negotiation, oscillating between inclusive and exclusive discourses of national identity. For example, the reformist president Mohammad Khatami promoted during his presidency (1997–2005) a more inclusive approach that relied on a ‘reconciliation of ethnicity with religion in constructing national identity’ and delineated a unique ‘Iranian-Islamic’ identity as opposed to the rest of the Islamic world (Siavoshi Citation2014, 258 and 266).

9. An exception to this was Ariana Melamed’s review in Haaretz, which praised the series’ political critique especially around its gender representation – placing at its centre a gentle female character (Melamed Citation2020) and an opinion piece by Rami Kimhi that engaged with Tamar’s Iranian origin (Kimhi Citation2021).

10. 2009 marks the launch of two Persian content TV Channels outside Iran. The first was BBC’s Persian Language News channel and the second was Farsi-1, the first international free-to-air Persian language general entertainment channel based in UAE. There are many more channels now available to video in Iran with Persian language content that are managed independent from Iran’s state Television IRIB. These foreign-run media networks are usually seen as mercenaries, agents, and dependants of superpowers such as United Kingdom or United States and/or are labelled as Zionist. The sole purpose of these media outlets is narrated as corrupting the Iranian people and coaxing them to oppose the state. See https://p.dw.com/p/LuOr.

11. In the street sign pointing to ‘Shahid Taymouri Street’ the word Jaddeh (Road) is used instead of Kuche (Alley) or Khiaban (Street). See mshrgh.ir/1049453.

12. (2020) https://hamshahrionline.ir/x6BJs.

References

- Aderet, O. 2020. “The Iranian Jews Who Joined the Islamic Revolution”, Haaretz, August 22. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-the-iranian-jews-who-joined-the-islamic-revolution-1.9088876

- Article, H. 2020. “Israeli Series Titled ‘Tehran’: Life of Anti Regime Youth from Resistance to Rock and Roll”, Hamshahri Online, April 14. https://hamshahrionline.ir/x6gFr

- Article, K. 2020. “The Production of an Israeli Series about Iranian Saditionists”, Kayhan, April 13. https://kayhan.ir/fa/news/185674/%D8%AA%D9%88%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%AF-%DB%8C%DA%A9-%D8%B3%D8%B1%DB%8C%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A6%DB%8C%D9%84%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%87-%D9%81%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%87%E2%80%8C%DA%AF%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AE%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%A7%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%A8%DB%8C-%D9%88-%D9%87%D9%86%D8%B1%DB%8C

- Bergman, Ronan and Kingsley, Patriick. “Despite Abuses of NSO Spyware, Israel Will Lobby U.S. to Defend It.” New York Times. Nov 11, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/08/world/middleeast/nso-israel-palestinians-spyware.html

- Blout, E. 2015. “Iran’s Soft War with the West: History, Myth, and Nationalism in the New Communications Age.” The SAIS Review of International Affairs 35 (2): 33–44. doi:10.1353/sais.2015.0028.

- Castonguay, J. 2015. “Fictions of Terror: Complexity, Complicity and Insecurity in ‘Homeland.’.” Cinema Journal 54 (4): 139–145. doi:10.1353/cj.2015.0045.

- Castrillo, P. 2019. “Castles and Labyrinths: Aesthetics of Power and Surveillance in Post-9/11 Television.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 47 (2): 111–119. doi:10.1080/01956051.2018.1540393.

- Castrillo, P. 2020. “The Post-9/11 American Political Thriller Film: Hollywood’s Dissident Screenplays.” Journal of Screenwriting 11 (2): 191–206. doi:10.1386/josc_00025_1.

- Castrillo, P., and P. Echart. 2015. “Towards a Narrative Definition of the American Political Thriller Film.” Communication & Society 28 (4): 109–123. doi:10.15581/003.28.4.109-123.

- Champion, M. 2016. “Tehran’s Minarets Have Gone Quiet”, Bloomberg, March 15. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2016-03-15/what-you-don-t-hear-in-tehran-is-the-call-to-prayer

- Chulov, M. 2021. “Israel Appears to Confirm It Carried Out Cyberattack on Iran Nuclear Facility”, The Guardian, April 11. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/11/israel-appears-confirm-cyberattack-iran-nuclear-facility

- D’Addario, D. 2020. “’Tehran’ Is an Uncomplicated Look at Global Conflict: TV Review”, Variety, September 25. https://variety.com/2020/tv/reviews/tehran-review-1234782496/

- Esfandiari, G. 2010. “Sohrab Arabi’s Mother: ‘If They Release All Prisoners, I’ll Forgive My Son’s Murderers”. Persian Letters. June, 6th. https://www.rferl.org/a/Sohrab_Arabis_Mother_If_They_Release_All_Prisoners_Ill_Forgive_My_Sons_Murderers/2063385.html

- Fernandez, B. 2020. “Tehran: New Israeli Spy Thriller Is Orientalist Brainwashing”, Middle East Eye, September 1. https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/tehran-new-israeli-spy-thriller-orientalist-brainwashing

- Gertz, N., and R. Yosef. 2017. “Trauma, Time, and the ‘Singular Plural’: The Israeli Television Series Fauda.” Israel Studies Review 32 (2): 1–20. doi:10.3167/isr.2017.320202.

- Glynn, K., and J. Cupples. 2015. “Negotiating and Queering US Hegemony in TV Drama: Popular Geopolitics and Cultural Studies.” Gender, Place & Culture 22 (2): 271–287.

- Hale, M. 2019. “The 30 Best International TV Shows of the Decade”, The New York Times, December 20, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/20/arts/television/best-international-tv-shows.html

- Harel, A. 2021. “Another Mysterious Iran Strike. Totally Different Circumstances”, Haaretz, June 27. https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/mysterious-iran-strike-israel-biden-bennett-1.9938574

- Hennigan, A. 2020, “‘Tehran’ on Apple TV+ Gets a Big thumbs-up – But Don’t Compare It to ‘Fauda’”, Haaretz, September. 24, https://www.haaretz.com/life/television/.premium-tehran-on-apple-tv-gets-a-big-thumbs-up-but-don-t-compare-it-to-fauda-1.9183021

- Amanat, A., and F. Vejdani, eds. 2012. Iran Facing Others: Identity Boundaries in a Historical Perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Jamal, A., and N. Lavie. 2020. “Resisting Subalternity: Palestinian Mimicry and Passing in the Israeli Cultural Industries.” Media, Culture & Society 42 (7–8, October): 1293–1308. doi:10.1177/0163443720919375.

- Jasson, M. 2015. Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York: New York University Press.

- Kamin, D. 2016. “Netflix Picks up Israeli Political Thriller ‘Fauda’.” 8 November 2016.https://variety.com/2016/tv/global/netflix-israeli-political-thriller-fauda-1201912287/

- Kamin, D. 2020. “‘Tehran’ Is the Latest Israeli Thriller, Emphasis on Thrills”, New York Times, October 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/09/arts/television/tehran.html

- Kimhi, R. 2021. “Behind Tehran Success: Israel’s Real Wonder Woman”. Haaretz, Culture supplement, November, 24. https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/opinion/.premium-1.10413637?utm_source=App_Share&utm_medium=Android_Native&utm_campaign=Share (Hebrew)

- Kudner, L. 2020. “How Has a Psychopath Managed to Control Syria for 20 Years, and What Is Israel’s Part in This?” Haaretz, June 30. https://www.haaretz.co.il/digital/podcast/weekly/.premium-PODCAST-1.8958461?utm_source=App_Share&utm_medium=Android_Native&utm_campaign=Share.(Hebrew)

- Kumar, D., and A. Kundnani. 2014. “Imagining National Security: The CIA, Hollywood, and the War on Terror.”Democratic Communiqué 26 (2): 72–83. Fall.

- Lavie, N. 2015. “Israeli Drama: Constructing the Israeli ‘Quality’ Television Series as an Art Form.” Media, Culture & Society 37 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1177/0163443714549086.

- Lavie, N., and A. Jamal. 2019. “Constructing Ethno-National Differentiation on the Set of the TV Series, Fauda.” Ethnicities 19 (6, December): 1038–1061. doi:10.1177/1468796819857180.

- Mark, K. 2020. “With Spy Series ‘Tehran,’ Israelis Reach Out to an Enemy”. The Independent (United Kingdom). September 25. Friday. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:60XF-RDG1-JBNF-W4BN-00000-00&context=1516831

- Matin-Asgari, A. 2012. “The Academic Debate on Iranian Identity: Nation and Empire Entangled.” In Iran Facing Others: Identity Boundaries in a Historical Perspective, edited by A. Amanat and F. Vejdani, 173–192. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Melamed, Ariana. 2020. “Apple TV+ Thriller ‘Tehran’ Starts Strong but Winds Up a Huge Disappointment”. Haaretz, August 2. https://www.haaretz.com/life/television/2020-08-02/ty-article/.premium/spy-thriller-tehran-starts-strong-but-winds-up-a-huge-disappointment/0000017f-dbb4-db22-a17f-ffb596250000

- Munk, Y. 2019. “Fauda: The Israeli Occupation on a Prime Time Television Drama; or, the Melodrama of the Enemy.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 17 (4): 481–495. doi:10.1080/17400309.2019.1666655.

- Nir, O. 2019. “Fauda and Crisis.” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 18 (1): 125–131. doi:10.1080/14725886.2018.1551278.

- Pears, L. 2016. “Ask the Audience: Television, Security and Homeland.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 9 (1): 76–96. doi:10.1080/17539153.2016.1147774.

- Ram, H. 2009. Iranophobia: The Logic of an Israeli Obsession. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Ramachandran, N. 2020. “ATF: Apple TV Plus Series ‘Tehran’ Season 2 in the Works”, Variety, December 3. https://uk.news.yahoo.com/atf-julien-leroux-teases-second-064828156.html

- Aghaie, K. S., and A. Marashi, eds. 2014. Rethinking Iranian Nationalism and Modernity. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Ribke, N. 2019. “Fauda Television Series and the Turning of Asymmetrical Conflict into Television Entertainment.” Media, Culture & Society 41 (8, November): 1245–1260. doi:10.1177/0163443718823142.

- Saunders, R. 2019. “Small Screen IR: A Tentative Typology of Geopolitical Television.” Geopolitics 24 (3): 691–727. doi:10.1080/14650045.2017.1389719.

- Shalev, E. 2020. “Tehran First Season – Enjoyable and Thrilling with a Big Credibility Problem,” Seret film portal, https://www.seret.co.il/critics/seriesreviews.asp?id=441. (Hebrew)

- Shavit, A. 2020. “Interview with the Director Dani Sirkin” Walla Culture, July 16. https://e.walla.co.il/item/3373456_ (Hebrew)

- Shechnik, R. 2016. “Netflix Buys Israeli Thriller Fauda”, Y Net News, August 11. https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4876301,00.html

- Shohat, E. 2006. “.” In Taboo Memories, Diasporic Voices. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Siavoshi, Susan. 2014. Construction of Iran’s National Identity: Three discourses. In Rethinking Iranian nationalism and modernity, (Eds,) Kamran Scot Aghaie and Afhsin Marashi. Austin: University of Texas.

- Spiro, A. 2021. “Israeli Thriller ‘Tehran’ Wins Best Drama at International Emmy Awards”, The Times of Israel, November23. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israeli-thriller-tehran-wins-best-drama-at-international-emmy-award/

- Sreberny, A., and G. Khiabany. 2021. “Where Is Iran?: Politics between State and Nation, inside and outside the Polity.” In Media and Mapping Practices in the Middle East and North Africa: Producing Space, edited by A. Strohmaier and A. Krewani, 261–282. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Steenberg, L., and Y. Tasker. 2015. “‘Pledge Allegiance’: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television and Homeland.” Cinema Journal 45 (4): 132–138. Summer. 10.1353/cj.2015.0042.

- Stern, I. 2020. “Can New Spy Thriller ‘Tehran’ Affect Israeli-Iranian Relations? Its Writer Hopes so,” Haaretz, July. 1. https://www.haaretz.com/misc/article-print-page/.premium.MAGAZINE-a-beautiful-and-unimaginable-iran-stars-in-this-new-israeli-tv-thriller-1.8956150

- Sternfeld, L. B. 2019. Between Iran and Zion. CITY: Stanford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Takacs, S. 2012. Terrorism TV: Popular Entertainment in Post-9/11 America. CITY: University Press of Kansas.

- Van Veeren, E. 2009. “Interrogating 24: Making Sense of US Counter-terrorism in the Global War on Terrorism.” New Political Science 31 (3, September): 361–384. doi:10.1080/07393140903105991.

- Vardi, A. 2020. “Israel’s Latest Spy Drama ‘Tehran’ Explores Nuclear Tensions”. Yahoo.com, July, 22. https://news.yahoo.com/israels-latest-spy-drama-tehran-explores-nuclear-tensions-031725772.html(Hebrew)

- Wiseman, A. 2021. “Yes Studios MD Danna Stern On The Israeli Drama Boom, The Future Of ‘Shtisel’ & ‘Fauda’ & Actors On The Rise”, Deadline, July 12. https://deadline.com/2021/07/shtisel-fauda-new-series-yes-studios-israel-drama-boom-danna-stern-1234789938/

- Yeshaio, I. 2020. “Tehran Fails Where Fauda Succeeded Massively,” Walla - Culture Magazine, June 22. https://e.walla.co.il/item/3368920(Hebrew)

- Youth Journalists Club article. 2020. “How the Zionist Series Has Turned into a Joke?” Youth Journalists Club, July 6. https://www.yjc.news/00V6hV

- Zanger, A. 2015. “Between Homeland and Prisoners of War: Remaking Terror.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 29 (5): 731–742. doi:10.1080/10304312.2015.1068733.