Abstract

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a type of large vessel vasculitis, and it involves the aorta, large vessels and terminal branches of the external carotid artery, especially the temporal artery. Temporal artery biopsy is a simple tool for the diagnosis of vasculitis, however, the histopathological findings do not always differentiate between the small-vessel vasculitis and GCA. We report the case of 72-year-old male who initially had a clinical diagnosis of GCA, then in the course of treatment, diagnostic histopathological approach revealed the necrotizing vasculitis with bronchocentric granulomatosis in the inflammatory nodule of the lung. The manifestations of patients with systemic vasculitis represent the disorders of multiple organ systems thus are diverse and may vary through the course of the disease. Presentation of unexpected features such as insufficient response to antibiotics, sinusitis, runny nose, discomfort of frontal region or pachymeningitis which anticipates re-evaluation of systemic vasculitis that may lead us to an appropriate diagnosis and the treatment.

1. Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most frequent type of large vessel vasculitis, it involves the aorta and large vessels of terminal branches of the external carotid artery especially the temporal artery [Citation1]. Temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is a simple tool for the diagnosis of vasculitis, however, the histopathological findings do not always differentiate between the necrotizing vasculitis and classic GCA [Citation2]. There have been several case reports that describe patients diagnosed with GCA who later developed granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) [Citation3]. Some authors proposed polyangiitis overlap syndrome as systemic vasculitis that does not fit into a single category of classical vasculitis classification [Citation4]. Clinical features of such overlapping disorders have not been well documented.

2. Case report

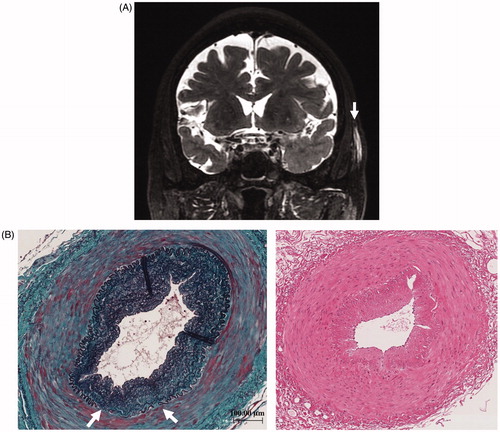

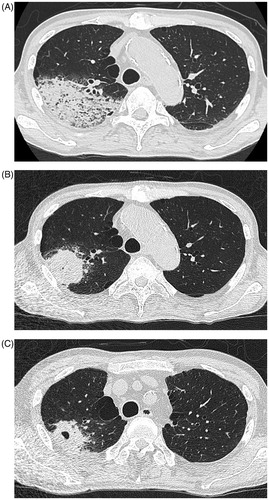

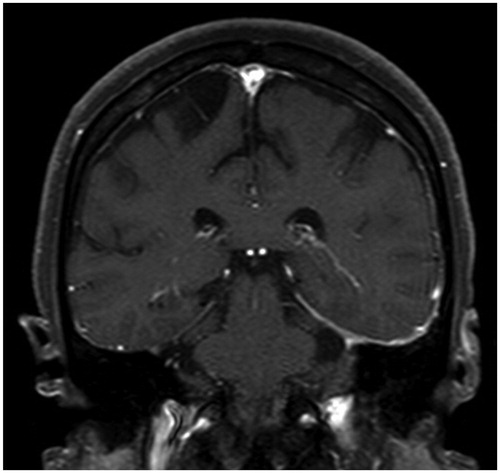

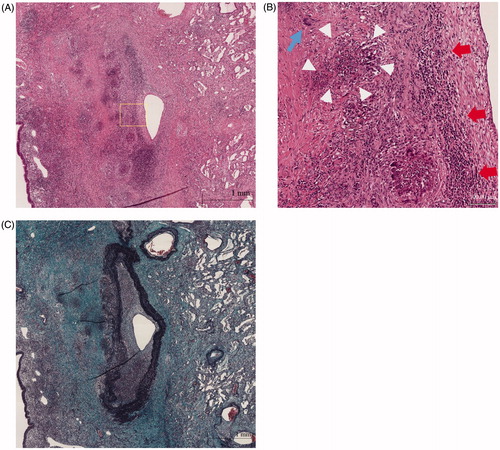

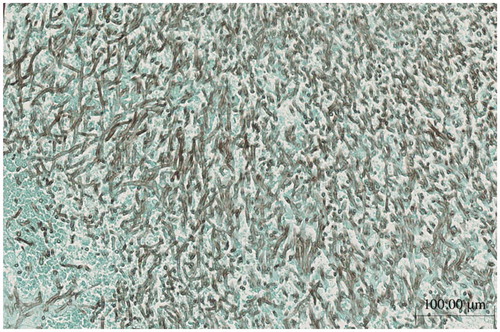

A 72-year-old male was referred to our department for the evaluation of episodes sustained left temporal and occipital severe pain and moderate degree of jaw claudication for 2 months. He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome for years and his previous doctor had treated him with oral glucocorticoid, prednisolone (PSL) 10 mg/day few days before for those clinical signs. His physical examination showed weakness of left temporal artery pulsation without visual symptoms, hearing disorders or arthralgia. He had a low-grade fever; blood pressure and heart rate were normal. Laboratory tests revealed high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 32 mm/h; elevated serum C-reactive protein level, 2.74 mg/dl and platelet depletion, 8.8 × 104/μL. Myeloperoxidase (MPO)-anti neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) was positive with the titer of 17 U/mL (ELISA) while proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCA was negative. Although microscopic hematuria was noted, no other abnormality of urine sediment and kidney function observed (serum creatinine was 0.76 mg/dL). Enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed subcutaneous swelling and partial vascular flow void signal on the left temporal artery (). Biopsy specimen from the left temporal artery revealed the intimal fibrous thickening, small rupture and fibrotic change of internal elastic lamina (). Potentially due to the previous and concurrent glucocorticoid therapy, the biopsy specimen included neither inflammatory cell infiltration nor giant cell; however, our decision was the histopathology is still consistent with GCA. We administrated high dose PSL (60 mg/day) for 2 weeks then gradually decreased the dose. Along the therapy, his clinical symptoms and laboratory tests were significantly improved. When the patient was treated with 20 mg/day of PSL, he presented pneumonitis and severe septic shock caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection confirmed by blood culture with no upper respiratory tract symptoms. While the sepsis treatment was successfully managed, administration of 20 mg/day of PSL was continued and the inflammatory cavitary lesion was remained in his right upper lobe (). The patient had a sporadic relapsing fever, however diagnostic fever workup such as blood and urinary culture, measurement of β-D-glucan, aspergillus, cytomegalovirus and cryptococcus antigenemia test provided no clue and C-reactive protein level fluctuated from 0.40 to 5.99 mg/dL. It was still difficult to totally exclude a possibility that the lung cavity was formed by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonitis, we prescribed levofloxacin (500 mg/day), itraconazole (200 mg/day) and PSL (10 mg/day) as outpatient treatment. When dose of PSL was tapered to 9 mg/day, the patient presented an exacerbation of headache and very slight nasal discharge with elevated C-reactive protein (12.50 mg/dL) and MPO-ANCA (7.0 U/mL) level; and that cavitary lesion of the lung became more apparent meanwhile he has no upper respiratory tract symptoms (). MRI of the head revealed new lesion of hypertrophic pachymeningitis () and right sinusitis. The constellation of clinical, laboratory and radiographic findings suggested GCA/GPA overlap syndrome which lead us to re-evaluation of organ manifestations. Finally, at 5 months after GCA diagnosis, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) was performed for the histological diagnosis and also as a diagnostic treatment, the findings demonstrated the necrotizing vasculitis with bronchocentric granulomatosis (). Increased dosage of PSL to 20 mg/day gave him a dramatic improvement in his clinical manifestations.

Figure 1. (A) The fat-suppression T1-weighted MRI showing subcutaneous thickening and partial vascular flow void signal that correspond with left temporal artery; arrow. (B) Left temporal artery biopsy (TAB) revealed the intimal fibrous thickening, small rupture and fibrotic change of internal elastic lamina (left panel; Elastica-Masson staining, white arrows). No apparent inflammatory cell infiltration or giant cell (right panel; Hematoxylin and Eosin staining).

Figure 2. (A) Chest CT; at the onset of severe pneumonitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (B) Chest CT; inflammatory cavitary lesion was remained in right upper lobe after sepsis treatment. (C) Chest CT; obvious cavitary lung lesion in the right upper lobe.

Figure 3. Contrast enhanced T1-weighted MRI showing enhancement of the dura beneath the left temporal lobe, compatible to hypertrophic pachymeningitis.

Figure 4. (A) Histopathology of lung lesion in right upper lobe (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining). (B) Higher power field of (A); diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes and necrotizing vasculitis with bronchocentric granulomatosis. Giant cell (blue arrow), inflammatory cells (red arrows), fibrinoid degeneration (circle of white arrowheads). (C) Histopathology of lung lesion in right upper lobe (Elastica Masson staining).

3. Discussion

GCA is an idiopathic granulomatous vasculitis primarily involving medium and large size vessels with a tendency to involve extracranial branches of the carotid arteries [Citation5]. Clinical features of GCA typically include low-grade fever, headache, temporal artery tenderness, acute vision loss, strokes, jaw claudication or polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) [Citation6–8], and headache and fever are the most prominent symptoms at onset [Citation9]. Temporal artery biopsy is the current gold standard for the diagnosis of GCA and also reported to be a diagnostic tool for systematic necrotizing vasculitis [Citation2,Citation10], admitting that negative TAB is observed in 20% up to 40% of GCA patient [Citation11]. In accordance with this notion, our interpretation of the TAB pathology was controversial; the small rupture and fibrotic change of internal elastic lamina could be an age-associated change and absence of apparent inflammatory cell infiltration or giant cell could be related to preceded steroid therapy.

GPA typically involves the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidney with varying degrees of vasculitis and GPA is usually associated with ANCA especially PR3-ANCA. Headache could be a common initial manifestation in GPA, however pulmonary infiltrate or sinusitis is more common symptoms [Citation12]. Our patient fulfilled only one criteria of 1990 ACR criteria for GPA (urinary sediment) and did not fulfill any criteria of ACR/EULAR Provisional 2017 Classification for GPA meanwhile the patient met the 1990 ACR criteria for GCA and even met the 2016 revised ACR criteria for GCA at the onset of treatment. ANCA-associated large vessel disease has been reported [Citation13], and those cases are usually involved thoracic or abdominal aorta, or a branched artery and has occurred in people younger as well as older than 50 years. As far as we are aware, there are few GPA cases reported that the large-sized vessel vasculitis with p-ANCA or MPO-ANCA positive [Citation14–16]. Thus, even negative TAB was obtained, it remains a possibility that our patient is a simple GPA from the onset.

Bradley and Pinals first reported GCA patient with pulmonary nodules, although they did not diagnose the case with overlapping of GCA and GPA [Citation17]. Several polyangiitis overlap syndrome have been reported, however, to the best of our knowledge, there are few reports of polyangiitis overlap syndrome involving GCA and GPA [Citation18]. Moreover, although MPO-ANCA-positive GPA is the predominant subtype (44.7–54.6%) among Japanese and Chinese patients [Citation19,Citation20], GCA preceding ‘MPO-ANCA-positive’ GPA as in the present case has not been reported so far.

A turning point for the diagnosis of GCA/GPA overlap syndrome was the depiction of hypertrophic pachymeningitis revealed by contrast-enhanced MRI in the workup for the exacerbated headache. Headache is quite a common symptom and it constitutes a major manifestation of GCA at the same time. Therefore, it had been difficult to further examination for the other causes behind GCA. Even a common manifestation, if it is accompanied by some abnormalities in laboratory test, active examinations, e.g. MRI imaging may provide us a valuable information.

On the other hand, we could not determine the primary disease process of the cavitary lung lesion even we obtained histopathological findings. We could not clearly exclude the possibility of infection as a cause of the cavity formation since the patient had developed life-threatening septic shock on the background of myelodysplastic syndrome. This may prevent us from reaching the appropriate therapy for the GPA. Indeed, there was compelling evidence for a concomitant pulmonary aspergillus infection in our patient (). Mechele and Stephen described a patient with GPA/EGPA polyangiitis overlap syndrome who is also histopathologically diagnosed concomitant aspergillus pulmonary infection [Citation5]. Interestingly, clinical improvement was acquired by strengthening immunosuppressive therapy (anti IL-5 therapy and azathioprine), while in the situation of corticosteroids and antifungal therapy could not obtain therapeutic effect. Although there is no reliable evidence, it is suggested that aspergillus infection occurred secondarily in the cavity, which had been formed by vasculitic pathophysiology of GPA in this case.

Figure 5. Concomitant aspergillus infection observed in granulomatous lesion in the lung parenchyma (Grocott staining).

In conclusion, the symptoms of patients with systemic vasculitis can present with a multitude of symptoms involving multiple organ systems that might alter subsequently, therefore when we detect those features such as insufficient response to antibiotics, sinusitis, runny nose, discomfort of frontal region or hypertrophic pachymeningitis even if it might seem common clinical course or signs we should continuously evaluate those signs and not exclude possibility of another diagnosis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Katsuyama T, Sada KE, Makino H. Current concept and epidemiology of systemic vasculitides. Allergol Int. 2014;63:505–513.

- Hamidou MA, Moreau A, Toquet C, et al. Temporal arteritis associated with systemic necrotizing vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2165–2169.

- Nishino H, DeRemee RA, Rubino FA, et al. Wegener's granulomatosis associated with vasculitis of the temporal artery: report of five cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:115–121.

- Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, et al. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2016;315:2442–2458.

- Quan MV, Frankel SK, Maleki-Fischbach M, et al. A rare case report of polyangiitis overlap syndrome: granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:181.

- Nesher G, Breuer GS. Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: 2016 update. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2016;7:e0035.

- Nesher G, Berkun Y, Mates M, et al. Risk factors for cranial ischemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Medicine. 2004;83:114–122.

- Gonzalez-Gay MA, Barros S, Lopez-Diaz MJ, et al. Giant cell arteritis: disease patterns of clinical presentation in a series of 240 patients. Medicine. 2005;84:269–276.

- Sun F, Ma S, Zheng W, et al. A retrospective study of Chinese patients with Giant cell arteritis (GCA): clinical features and factors associated with severe ischemic manifestations. Medicine. 2016;95:e3213.

- Généreau T, Lotholary O, Pottier MA, et al. Temporal artery biopsy: a diagnostic tool for systemic necrotizing vasculitis. French Vasculitis Study Group. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2674–2681.

- Bornstein G, Barshack I, Koren-Morag N, et al. Negative temporal artery biopsy: predicitive factors for giant cell arteritis diagnosis and alternate diagnoses of patient without arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:2819–2824.

- Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Katz P, et al. Wegener's granulomatosis: prospective clinical and therapeutic experience with 85 patients for 21 years. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:76–85.

- Chirinos JA, Tamariz LJ, Lopes G, et al. Large vessel involvement in ANCA-associated vasculitides: report of a case and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23:152–159.

- Carels T, Verbeken E, Blockmans D, et al. p-ANCA-associated periaortitis with histological proof of Wegener's granulomatosis: case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:83–86.

- Dábague J, Arévalo RM, García-Torres R, et al. Takayasu's arteritis and Wegener's granulomatosis. A coincidental case. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13:413–414.

- Shitrit D, Shitrit AB, Starobin D, et al. Large vessel aneurysms in Wegener's granulomatosis. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:856–858.

- Bradley JD, Pinals RS, Blumenfeld HB, et al. Giant cell arteritis with pulmonary nodules. Am J Med. 1984;77:135–140.

- Hassane HH, Beg MM, Siva C, et al. Co-presentation of giant cell arteritis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a case report and review of literature. Am J Case Rep. 2018;6:651–655.

- Ono N, Niiro H, Ueda A, et al. Characteristics of MPO‐ANCA‐positive granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a retrospective multi‐centre study in Japan. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:555–559.

- Chen M, Yu F, Zhang Y, et al. Characteristics of Chinese patients with Wegener's granulomatosis with anti‐myeloperoxidase autoantibodies. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2225–2229.