ABSTRACT

Production of livestock in urban spaces is a common phenomenon globally, particularly in the Global South. Livestock provides multiple benefits to society yet its production in urban spaces can result in adverse impacts to residents that can trigger conflicts. Understanding of the ecosystem services and disservices of livestock from the perspectives of residents can inform inclusive local management plans. Using household surveys and key informant interviews, this study sought to examine the contribution of livestock to owners, and perceptions of livestock services and disservices among non-livestock owners and key informants in Makhanda, a medium-sized South African town. Livestock owners derived multiple benefits from their livestock, including provisioning services such as meat, milk, skins and draught, and use livestock and livestock products in cultural activities such as rituals, bride price payments and funerals that are key elements of local identity. Among residents, there were marked differences in perceptions on the services and disservices of livestock which points to potential conflicts over urban land use and the need for addressing trade-offs. A key trade-off for local municipal authorities is addressing hunger and poverty by supporting well-regulated urban livestock production versus managing potential livestock disservices such as injuries to humans, livestock-vehicle collisions, health hazards and damage to urban green infrastructure. The trade-offs should be understood and considered by local authorities and residents as a basis for collectively developing strategies that can integrate livelihoods and cultural realities to balance competing demands for urban spaces including livestock production and other uses.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Globally, livestock production is a key livelihood strategy for many communities and its contribution can be seen in the range of benefits derived from livestock such as meat, milk, blood, dung, draught, and use in cultural activities (Shackleton et al. Citation2005; Herrero et al. Citation2009; Alarcón et al. Citation2017; Ryschawy et al. Citation2016; Du-Pont et al. Citation2020). However, until recently, livestock production has been regarded as a livelihood activity practised more in rural areas than urban ones. Yet, with growing urbanisation, along with global calls for greater localisation of food production systems, food sovereignty and urban sustainability, there is increasing academic, policy and practical interest in urban agriculture, including urban livestock husbandry (Lee-Smith Citation2010; Siegner et al. Citation2018). Especially without sufficient formal economic opportunities, many urban poor in the Global South engage in livestock husbandry for home consumption and cash income generation (Guendel and Richards Citation2002; Thys et al. Citation2005; Foeken and Ouwor Citation2008; Thornton Citation2008; Davenport et al. Citation2011) and for use in traditional activities and rituals linked to cultural identity (Beudou et al. Citation2017; Cundill et al. Citation2017). However, evidence also shows the involvement of the well-off in urban livestock production (Davenport and Gambiza Citation2009) and a growing demand for land for livestock husbandry by the urban working-class (Jacobs Citation2018), highlighting livestock production’s role in providing economic opportunities.

Despite growing evidence of widespread livestock husbandry in urban areas, this is mostly understood from studies of small-scale and monogastric livestock systems, characterised by the rearing of pigs, poultry and rabbits (Schiere and van der Hoek Citation2001). Monogastric farming is often practiced in contexts of limited space, in the absence of rangelands and where there is abundant food waste, which allows the establishment of backyard systems. Monogastric livestock often depend on food waste from households, restaurants and from industrial processes such as breweries or canning factories (Schiere and van der Hoek Citation2001; Doron Citation2020). Yet in South Africa, the context is largely different, where large stock (cattle, goats, sheep and donkeys) in urban settings graze in designated grazing areas known as commonages (Davenport and Gambiza Citation2009), and in undesignated spaces such as street verges, sports fields, public parks and servitudes. Moreover, in South Africa there are marked disparities in green urban infrastructure along economic and racial lines, a legacy of Apartheid-era spatial planning (Venter et al. Citation2020; Shackleton and Gwedla Citation2021). These disparities have implications for managing urban spaces equitably, including grazing resources for livestock. Further, urban areas are characterised by diverse cultural, economic and social milieus, imbued with varied interests and perceptions on livestock production and use (Alarcón et al. Citation2017). Therefore, considering the range of perceptions of livestock keeping in urban contexts, and how these might influence urban policy and planning, is an important subject.

An understanding of the perceptions of livestock in urban contexts is of paramount importance because livestock can provide both services and disservices to the larger urban community (Herrero et al. Citation2013; Alarcón et al. Citation2017; Shackleton et al. Citation2017; Doron Citation2020). The contribution of livestock to human wellbeing is well documented, including provision of milk and meat, manure, skins, manure for biomass energy, draught power and a store of wealth, pride and social standing (Shackleton et al. Citation2005; Amadou et al. Citation2012; Herrero et al. Citation2013; Behera et al. Citation2015; Du-Pont et al. Citation2020). The value of livestock to society is also demonstrated by the number of households involved in and economic value derived from livestock production. In Niamey, Niger, up to 80% of households engage in livestock husbandry for its provisioning services (Graefe et al. Citation2008). In Uganda, Lee-Smith (Citation2010) shows that the proportion of urban and peri-urban households involved in livestock production increased from 30% in 1991 to 56% in 2003. Davenport and Gambiza (Citation2009) estimate the annual net value of livestock (including savings value accrued to livestock) per owning household to range between R6,308 (US$ 809) and R9,707 (US$1,244) in Grahamstown and Riebeek East, South Africa.

However, in the process of providing these benefits, livestock can have adverse impacts on society and the environment. Keeping livestock in urban spaces has historically been contested due to perceived harmful impacts on health and well-being. Negative impacts of livestock include bad smells and nuisance from dung, noise and transmission of diseases (McClintock et al. Citation2014), injury to humans (Doron Citation2020), abandoned animals in cities (Withnall Citation2019) and damage to trees and lawns in streets, parks and gardens (Richardson and Shackleton Citation2014; Shackleton et al. Citation2017; Shackleton and Njwaxu Citation2021). Free-roaming livestock in urban areas may also forage in rubbish bins in search of food and thereby spread litter and pollute the vicinity (Lyytimäki and Sipilä Citation2009). Livestock can also result in production of dust due to trampling in enclosures, soil compaction and lower water infiltration capacity (Lyytimäki et al. Citation2008). Given these concerns, urban livestock production is often viewed as problematic, a sign of poverty and unprogressive for modernity agendas (Doron Citation2020). This mantra partly explains the lack of support and subsequent neglect of livestock keeping in urban settings (Schiere and van der Hoek Citation2001).

Because of their diverse cultural, economic and social backgrounds, perceptions and needs, urban residents can hold varied perspectives on the services and disservices of livestock in urban areas. These varied perspectives are likely to be particularly stark in a country like South Africa characterised by socio-economic and cultural disparities that are also reflected in available green infrastructure (Venter et al. Citation2020; Shackleton and Gwedla Citation2021). Subsequently, urban authorities are faced with a challenging task of developing infrastructure and providing opportunities to meet the needs of different groups of residents.

However, the presence of livestock production in urban areas can reconfigure urban landscapes that may present a conundrum for urban authorities with regards to designing livestock management strategies that minimise inter – and intra-community conflicts. Such conflicts can emerge from competition for the use of urban space among residents, the limited role of livestock farmers in council decisions that can directly affect them (Paniagua Citation2014) and concerns over public health (Butler Citation2012). One of the first steps in designing equitable policies is to simultaneously consider how services and disservices of livestock are perceived by residents as a basis for informing livestock management options that account for all users of urban spaces. Within this context, the aim of this paper is to examine the contribution of livestock to owners’ livelihoods and the perceptions of urban livestock ecosystem services and disservices by non-livestock owners. The main questions included (1) what are the provisioning and cultural benefits to owners, (2) what are perceived livestock ecosystem services (and by who), (3) what are the perceived livestock ecosystem disservices (and by who), (4) and why do these perceptions vary?

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area

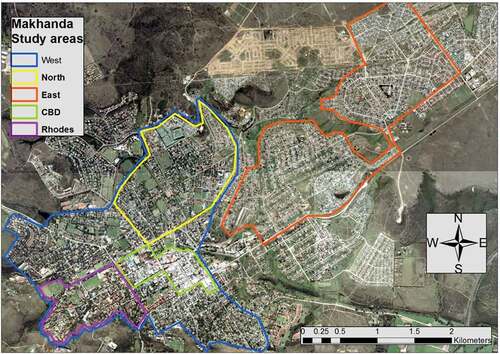

The study was conducted in Makhanda (33◦ 31ʹ S, 26◦ 53ʹ E), a medium-sized town in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa (). The town receives a mean annual precipitation of 670 mm with most of it (60%) in summer (October-March), but there is marked variability, and droughts are common. The dominant biome in Makhanda is Albany Thicket, but the town has a highly diverse environment and vegetation including grasslands, thornveld and thicket because it is surrounded by several mountain ranges (Mucina and Rutherford Citation2006)

Figure 1. Location of Makhanda in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa (Note: Makhanda was previously known as Grahamstown; Gqeberha was previously known as Port Elizabeth).

The population of Makhanda is about 70000, distributed across the four main population groups of South Africa as roughly 73% Black African, 11% White, 14% Coloured and 1% Indian or Asian (Statistics South Africa Citation2012). Recognising the problematics of such racial categorisations, we define Whites as those of European ancestry and Blacks as those of African descent consistent with national level separation in equity discourses and government census documents (Statistics South Africa Citation2012). Consistent with trends in the Eastern Cape province, education levels are very low with a correspondingly high unemployment rate of about 33%. About 6% of the population is illiterate and only 15% has tertiary level education while 24% has a school-leaving certificate qualification (Statistics South Africa Citation2012). With a high unemployment rate, a significant proportion of the population is poor as illustrated by a sizeable proportion (41%) of households that are dependent on state social grants. However, these figures are an estimate for the whole Makhanda population thereby concealing income group disparities.

Like many South African cities, Makhanda’s urban geographical setting is shaped by spatial politics of the colonial and apartheid eras (Venter et al. Citation2020; Shackleton and Gwedla Citation2021). The well-off western side, formerly reserved for white residents, is characterised by highly educated and salaried households. The area has big gardens and large green spaces, including grassy verges, street trees, parks and sports fields (). The Central Business District (CBD) is located on the western side of the town. While the CBD area is racially diverse, it is still dominated by white households, most of whom do not have a cultural connection with livestock. Very few households in Makhanda West keep livestock, and those who do, mainly keep poultry. The poorer eastern side of Makhanda (), locally known as the township, is largely occupied by black households. It is characterised by low education levels with a correspondingly high unemployment rate and dependence on social grants (Statistics South Africa Citation2012). It is characterised by small houses, a sizeable number of informal housing areas, small gardens and few public green spaces (Davenport et al. Citation2012).

Figure 2. Map of Makhanda showing Makhanda West (North, Rhodes and Central Business District) and Makhanda East.

It is estimated that about 263 households, all located in Makhanda East, are involved in livestock husbandry and keep their animals on peri-urban municipal commonages (Davenport et al. Citation2012). About 6,686 ha of local commonage is available for livestock grazing. Davenport et al. (Citation2012) reported 1,850 cattle and 1,915 sheep and goats, whilst the number of donkeys was unknown. The commonages, divided into three sections, are under the notional management of the Parks and Recreation Department of the municipality under the Community and Social Services Executive. The commonages are located on the peri-urban fringe. Constraints such as lack of funding and poor governance structures are behind poor management of designated grazing areas. Evidence of land degradation due to livestock overgrazing in peri-urban commonages, and theft of livestock and infrastructure (fences and poles) have been reported (Davenport et al. Citation2012). These challenges have been compounded by recurrent droughts, which means animals tend to freely move to undesignated areas of the town including sports fields, parks, and streets as they seek forage. In some cases, subsistence farmers deliberately let their animals roam freely instead of managing them on the commonages (Shackleton et al. Citation2017).

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected using surveys and key informant interviews between May and July in 2015. The first survey focussed specifically on livestock owning households, using a snowball sampling strategy. A referral method was used because livestock owners live in an integrated way alongside non-livestock owners which made it difficult to identify them. Forty-one owning households, representing about 16% of livestock owners were interviewed in the local language, isiXhosa. The first section of the questionnaire was designed to collect information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, including age, gender, household size, employment status and dependence on social grants. The second section collected information on provisioning services and financial (subsistence and cash income) values of livestock over the preceding 12 months. Questions were designed to gather information on livestock types, herd sizes, provisioning services of livestock using a checklist, frequency of use, whether livestock were kept for cultural, subsistence or commercial purposes and unit of prices of animals or animal products and services (e.g. meat, hide and transport) if marketed. The respondents were asked to indicate and explain in depth the uses of livestock in cultural activities.

The second survey was administered to a stratified random selection of 100 non-livestock owners to explore perceptions on the services and disservices associated with livestock. Using ArcGIS 10 the city was stratified into two, namely Makhanda East consisting of low-income residential areas (townships) and informal settlements, and Makhanda West consisting of the Central Business District, affluent western and northern residential areas, and Rhodes University. Thereafter, a 20 m by 20 m fishnet was superimposed over each and a randomised selection of cells was made, with 40 in Makhanda East and 60 in Makhanda West. Since homesteads in Makhanda West are generally larger than those in the East, more cells were selected in Makhanda West. However, an equal number of households was selected for interviews from both sides of town. The non-livestock owning respondents were asked to provide their views towards livestock in urban settings with respect to (i) whether or not they feel livestock husbandry in urban settings is appropriate, (ii) the perceived services and disservices associated with livestock husbandry in the town, and (iii) whether livestock husbandry is a properly managed sector, with responses on a three-point scale (agreed, neutral or disagree). In the interests of keeping the surveys short and reducing research fatigue, we did not collect detailed socio-demographic information of as we deemed this less relevant for the non-owners. We were interested more in their perceptions and experiences than economic issues (as in the case of livestock owners).

Personal interviews were held with four key informants from local institutions; the South African Police Service (SAPS), Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) and Rhodes University Health Services and the Safety, Health and Environment units. Informants from these institutions were chosen because of the respective institutions’ involvement in societal relations, animal welfare, human health care and environmental management issues. All interviews were conducted in compliance with Rhodes University ethical research guidelines including observance of anonymity of respondents, confidentiality of responses, prior informed consent, and the right for respondents to withdraw from the study at any point without any negative repercussions. The research was granted ethical approval by the Department of Environmental Science Ethics Committee in 2015.

2.3. Data analysis

All the survey responses were entered into Microsoft Excel for cleaning and basic summaries. Descriptive statistics, including report counts and proportions in the form of tables and figures were used to present socio-demographic profile of the respondents, the proportion of livestock-owning households citing various provisioning and cultural services of livestock and the proportion of non-livestock owners citing services and disservices of livestock. Differences in responses between Makhanda East and West were tested by means of Chi-squared tests. The economic value of livestock to owners was estimated as the mean gross incomes from home consumption and cash sales. The value of livestock and livestock products consumed at home or sold was calculated by multiplying the total number of animals (or animal products) slaughtered or sold per year by the average local market price for the respective livestock type. Calculation of mean livestock values for owning households excluded labour costs given high unemployment in the area, which translate to few opportunities for external labour. The rand-dollar exchange rate at the time of study in 2015 was approximately US$1 = R12.00.

An inductive content analysis was used to analyse respondents’ perceptions on livestock ecosystem services and disservices. The text was first coded and categorised in terms of the perceived services and disservices. Following this step, the codes were further categorised into code categories to allow further summarisation of data. The services were coded into provisioning services (meat provision, milk, skin, manure and draught) and cultural services (rituals, funerals, lobolo, weddings and others). Text on respondents’ views on disservices was coded as foraging in rubbish bins, damage to green spaces, animal-vehicle accidents, bad odour and injury to humans. Descriptive statistics were used to indicate how the perceptions differed by demographic group, and Chi-squared tests were applied to disaggregate findings by respondent group. Data from interviews were used as a source of narrative data to enrich interpretation of quantitative data from surveys. This is presented in the form of quotes from key informants. Discussions covered potential factors, drawn from the literature (Stemler Citation2000) that may have some influence on the nature of the responses by the different demographic group.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographics of livestock-owning and non-owning households

Out of all the livestock owning households surveyed, 80% of the respondents were male, while there was an almost equal distribution of females (52%) and males (48%) among respondents from non-livestock households, and more females than males for key informants (). Three out of four key informants were females. The age of the non-livestock owning respondents ranged from 18 years to over 50 years old, which eliminated any chance of bias. About 79% of respondents interviewed in the livestock-owning households were unemployed, which is more than the provincial average unemployment rate of 32.5% (Statistics South Africa Citation2012) and about two-thirds of the households (66%) received government social welfare grants (childcare, disability, child foster and old age grants). Household size varied from 1–18, with an average of 5.4 ± 3.6 persons.

Table 1. Summary of samples

3.2. Livestock ownership, uses and value

Among all the livestock-owning households 73% owned cattle, 22% owned goats and two households had donkeys. A total of 385 animals were owned by households, and out of this 74% were cattle, 19% goats and the remaining 7% were donkeys. On average, households owned about 9.3 ± 11.8 animals, ranging from 2 to 30 animals. About two-thirds (66%) of the households said they practiced livestock husbandry for subsistence purposes, while 10% did so solely for cash income generation, and 24% kept livestock for both. Households used cattle manure to improve soil fertility in home gardens and sometimes offered it to neighbours at no cost. In a few instances, cow dung was used to coat firewood to make fires burn longer. Excess manure was dumped at open sites within the neighbourhood. Animal skins were used by some households after an animal was slaughtered for subsistence or cultural purposes. Skins were used for decoration, as mats or split into strips to make ropes. Some households gave away the skins to neighbours or relatives ().

The annual subsistence and cash value of livestock was estimated at R6,423 (US$535) per livestock-owning household. Cattle, either slaughtered or live, were sold at varying prices ranging from R5,000 (US$417) to R10,000 (US$833) per animal depending on the sex and age of the animal. Female and young cattle fetched higher market prices than males and old cattle. The selling of livestock was not a regular livelihood activity but was situational, that is, it was mainly done in instances of social and economic stresses such as ill-health, death, or loss of employment in the family, and to pay for school fees and other household needs like health-related costs.

Livestock was also used for several cultural events but slaughter for ancestral rituals was reported by a larger proportion (73%) of livestock owners than for funerals, weddings and lobolo (formally accepted vernacular term for bride price in rural southern Africa) (). Funerals, birthdays and weddings were considered important but owners preferred not to slaughter their own livestock for such, but to buy livestock for these events. For rituals, the respondents reported the use of cattle and goats for Imbeleko (a Xhosa ceremony to introduce family members to their ancestors) and Imigidi (a traditional initiation ceremony). In traditional rituals, such as installation of ancestral spirits, animals (usually goats) were slaughtered as an offering in worship of the ancestors. The use of livestock in cultural events such as brewing of traditional beer and birthdays, was reported by a few respondents. It was also reported that livestock ownership symbolised high social status, particularly for owners with large herds who offered their livestock to other families for certain cultural activities such as rituals and funerals

.3.3. Non-livestock owners’ perceptions on livestock ecosystem services

Non-owners reported that on average they noticed livestock at least three times a week in the residential areas of both Makhanda West and Makhanda East and relatively less so in the CBD and at Rhodes University (). Frequent sightings of livestock in residential areas could be explained by the existence of more green spaces and vegetation compared to the mostly built-up infrastructure of the CBD.

Non-livestock owning residents were asked whether they perceived livestock as providing provisioning and cultural services in urban areas. Almost two-thirds (65%) agreed that livestock provided provisioning services. However, disaggregation of the findings by respondent group () shows that more respondents in Makhanda East (80%) than in Makhanda West (61%) agreed that livestock provided provisioning services such as meat, milk and skins (χ2 = 22.0; p < 0.0001). While there were no marked differences in the proportion of respondents who disagreed, a quarter of Makhanda West respondents were unsure compared to only 5% for Makhanda East. When asked about the perceived services of livestock, more respondents in Makhanda West (68%) than in Makhanda East (55%) cited manure, while more East (45%) than West (32%) respondents cited draught power. About three-quarters of all respondents agreed that livestock provided cultural services (ritual slaughter, funerals and other traditional events) but a significantly bigger proportion (χ2 = 20.3; p < 0.0001) of respondents in the low-income areas (90%) were in agreement than in the high-income areas (71%). The proportion of respondents who disagreed or were unsure was higher for the high-income respondents (18% and 14%) than the low-income respondents (only 5%).

3.4. Non-livestock owners’ perceptions on livestock disservices

In both Makhanda West and Makhanda East a substantial proportion (>80%) of respondents reported that the main ecosystem disservice associated with livestock husbandry was foraging in rubbish bins and damage to green spaces which reduced their aesthetic appeal and functionality (). Overall, there was no significant difference between Makhanda and East and West in the proportion of respondents reporting different disservices (χ2 = 5.7; p > 0.05).

Table 2. Proportion (%) of respondents citing ecosystem disservices of livestock husbandry in Makhanda

It was also reported that livestock on roads posed a hazard, leading to the risks of livestock-vehicle collisions but more respondents in Makhanda West (65%) than in Makhanda East (50%) felt this. Other adverse impacts of livestock mentioned included bad odour and injuries to humans but slightly more respondents from the East than the West reported so. Taken together, there were no huge disparities in the proportion of respondents between Makhanda West and East citing disservices except for one disservice (livestock-vehicle collisions) where 15% more respondents in Makhanda West perceived livestock as a major cause of vehicle accidents (). The perceived disservices were also echoed by key informants, as illustrated in these quotes:

‘Livestock are a danger in the cities, I once was involved in a car accident because the car was trying to avoid hitting a donkey on the road’. (South African Police Services official)

‘The main problems with having livestock in the city is that they can cause accidents, damage people’s gardens as well as cause various health issues.’ (Rhodes University Safety, Health and Environment official)

‘Their presence in an urban setting poses a danger to the public and a danger to the livestock themselves’. (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals official)

‘Where I live there is a dumping ground that attracts livestock and I feel this is dangerous for the small children running around. Also, I think animal dung is a health hazard for the general population’. (Rhodes University Health Services official)

3.5. Non-livestock owners’ perceptions on livestock husbandry in urban settings

More respondents in Makhanda West (66%) than in Makhanda East (25%) disagreed with the practice of livestock husbandry in urban settlements (). Relative to low-income areas, more respondents from high-income areas believed livestock were dangerous (73%), a nuisance (66%), unappealing in towns (53%) and were poorly managed. Although many Makhanda East respondents acknowledged that livestock were dangerous (70%) in urban settings, many supported livestock husbandry and perceived livestock as appealing (60%), and well-managed (55%) compared to high-income respondents ().

Many felt that livestock husbandry should not be part of urban space as reflected in the following statements from key informants:

‘I have not seen any cases of injury from livestock in my profession, only dog bites. But my personal opinion is that livestock do not belong in towns’. (Rhodes University Health Services official informant)

‘As much as livestock may be beneficial to the community, they do not belong in urban areas’. (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals official)

‘Livestock do not belong in the urban areas, Grahamstown has communal farms that’s where they belong in these communal farms.’ (South African Police Services official)

However, one key informant was very positive about livestock husbandry in urban spaces as reflected in the following statement:

‘Legally livestock do not belong here, but personally I like having them on my street. I like the smell and ambience you get from having animals around when they are not opening rubbish bags and spreading the rubbish of course. I do understand that some people don’t know how to respond to animals and might feel threatened … especially with bullocks with horns.’ (Rhodes University Safety, Health and Environment official)

4. Discussion

4.1. Livestock ecosystem services

A substantial number of livestock-owning households owned large stock (cattle). The use of multiple goods and services provided by livestock such as meat, milk, skins and draught power are consistent with the literature on the benefits of livestock in South Africa (Shackleton et al. Citation2005; Davenport et al. Citation2012; Thondhlana et al. Citation2012; Du-Pont et al. Citation2020) and elsewhere (Ryschawy et al. Citation2016; Alarcón et al. Citation2017). The mean annual direct use value of livestock per household (R6,423) (US$535) is comparable to the value range (R2,605 – R9,753) (US$186 – US$697) reported by Herd-Hoare and Shackleton (Citation2020) in three rural villages in the same province of South Africa, and the R4,973 by Shackleton et al. (Citation2005) in Limpopo Province. However, it is lower than the R6,308 – R9,707 (US$809 –US$1,244) estimated by Davenport and Gambiza (Citation2009) in Makhanda and the R15,608 (US$1,115) reported by Du-Pont et al. (Citation2020). These differences could be explained by contextual factors including the diversity of income sources available to livestock owners, price inflation and the type, size, gender and age of livestock sold. Considering that livestock incomes can contribute up to 16% of total household incomes of urban livestock owners (Davenport et al. Citation2012), urban livestock husbandry represents an important source of livelihood. However, the importance of social grants as a primary income for the unemployed should not be overlooked (Thornton Citation2008).

Besides subsistence use of livestock, the use of livestock for cultural activities was common, including ritual slaughter, funerals and bride price payment. These findings confirm well-known links between livestock husbandry and cultural traditions and identity, even in the urban context (Thys et al. Citation2005; Thornton Citation2008). For example, among the Xhosa people of South Africa, livestock, in particular cattle and goats, form the lenses through which culture and identity are constituted (Ainslie Citation2005a; Cundill et al. Citation2017). Ritual slaughter of cattle and goats for cultural activities such as communicating with and showing gratitude to ancestors, chasing bad omens and evil spirits, lwaluko (male circumcision), and payment of lobolo (bride price) is common and forms part of Xhosa identity (Du-Pont et al. Citation2020). Onyango (Citation2016) also notes that note bride price payment remains a common practice in many traditional African societies and is centred on building a relationship between the bridegroom and bride’s family. However, the practice of paying the bride price in the form of livestock is increasingly questioned due to its entrenchment of patriarchal practices and tendency to be commercialised (replacement of livestock with cash payment), with adverse impacts on women, including treatment of women as property and the girls as investment opportunities, forced marriages, family conflicts, gender-based violence, and loss of female control over their bodies and property rights (Anderson Citation2007, Citation2014; Onyango Citation2016).

4.2. Perceptions of livestock ecosystem services and disservices among non-livestock owners

Three key findings that have implications for livestock husbandry in urban settings were noted among non-livestock owners. First, though there was a general agreement on the provisioning services of livestock, more respondents from low-income areas than from well-off neighbourhoods reported so. Second, concerning provisioning services to non-livestock owners, more well-off than low-income respondents perceived that livestock provided manure to local areas while more low-income than well-off respondents cited draught. Third, there were no marked differences in the perceptions on disservices between Makhanda West and East residents except for livestock-vehicle accidents which was reported more by the former than the latter. This could be explained by a higher rate of car ownership and use of cars for transport in the West than in the East.

These findings point to heterogeneity in views on livestock ecosystem services, and it turn, on how to manage livestock husbandry in city spaces. For example, while there was a general agreement that livestock provided services, there was limited consensus regarding the nature of these services to different people and livestock husbandry in cities more generally. This disproportion might be influenced by the proximity of these respondents to areas where livestock raising is predominant and cultural connections to livestock hence is more acceptable than for the well-off residents. More positive perceptions of and support for livestock husbandry in urban settings by low-income respondents could be attributed to many Xhosa households found in low-income areas. The Xhosa communities have a long tradition of keeping livestock for subsistence and cultural purposes (Ainslie Citation2005b, Citation2013; Thornton Citation2008). In contrast, high-income areas are generally characterised by people with a more western worldview. Thus, it is likely they might view roaming animals as lacking proper care and ritual slaughter of livestock as exhibiting ‘barbaric’ behaviours (Ballard Citation2010). Those who are against urban livestock husbandry tend to perceive livestock disservices are intolerable and incompatible with modern codes and ethics (Ballard Citation2010; Doron Citation2020). It is worthwhile to note that the perceptions of key informants were somewhat reflective of their professions and the values their organisations represent. The South African Police official highlighted livestock-vehicle accidents as a disservice, a Safety, health and environment official mentioned accidents, damage to gardens and health concerns, while an official representing prevention of cruelty to animals talked about danger to both the public and the animals themselves. A health service official referred to the potential danger to humans when livestock forage in dumps, and the potential health hazard from animal dung. This illustrates how values, experience and interests might shape the perceived services and disservices of livestock, and the need to understand them as basis for developing equitable policies and measures for managing and regulating city spaces.

The diverse views on urban livestock husbandry could also be attributed to the colonial era spatial politics that translated into segregated urban planning (Parry and van Eeden Citation2015; Strauss Citation2019). In South Africa, low-income residential areas are characterised by smaller green spaces and less green infrastructure compared to more affluent residential areas (Venter et al. Citation2020). This situation has obvious negative implications on available grazing resources for livestock and environmental justice in urban spaces. Given the fewer green spaces in low-income neighbourhoods where livestock husbandry is concentrated, livestock is likely to roam private and public spaces such as residential areas and recreational parks. This is certainly the situation in our case study where available commonages are insufficient to meet the grazing need, and are not well-managed (Davenport et al. Citation2012). This situation is compounded by poor grazing management owing to lack of funding and poor governance structures. For Davenport et al. (Citation2011,Citation2012) provide evidence of land degradation of the commonages due to overgrazing. Further, there are reports of infrastructure damage, including theft of fences and poles which means livestock cannot be contained in commonages. In addition, persistent droughts have also meant that high-income residential areas tend to have ‘greener pastures’ than low-income neighbourhoods due to availability of bigger green spaces and tree-lined streets. Therefore, livestock tend to move to other neighbourhoods seeking forage and, in some cases, livestock owners voluntarily allow their animals to roam freely rather than keep them on the commonages. Uncontrolled roaming of livestock can result in damage to urban parks (Shackleton et al. Citation2017; Shackleton and Njwaxu Citation2021), damage to street trees (Richardson and Shackleton Citation2014), foraging in bins which can result in unsightly streets, and pose the risk of livestock-vehicle accidents. These livestock ecosystem disservices could perpetuate negative feelings about livestock husbandry in urban spaces and conflicting views on how livestock should be managed in these spaces. Further, the differences in perceptions could be explained by cultural nuances. Most residents in Makhanda West are not livestock owners and do not have a cultural connection to livestock, while their counterparts in the East do.

4.3. Dealing with livestock husbandry trade-offs

The persistent effect of differentiated urban spatial planning cannot be ignored, if urban spaces are to be socially meaningful and environmentally-just spaces for all residents (Venter et al. Citation2020). This means that urban livestock husbandry should be considered a legitimate socio-economic and cultural activity that entails trade-offs. Consideration of trade-offs can allow urban planners to consider the varied positive and negative impacts of livestock husbandry in urban spaces, with a view to making urban spaces functional for residents and socially-just. Ignoring or failing to fully understand these trade-offs might result in urban policies, such as a ban on livestock in urban spaces, without providing alternative grazing land, that perpetuate inequality between the well-off and poor communities, an undesirable social outcome in a country already battling high levels of inequality.

In embracing livestock husbandry and its trade-offs, there is a need to consider the mismatch in the scale of the trade-offs. The benefits or services of livestock identified in this study accrue mostly to livestock-owning households although there is some donation of some products, such as dung, to non-owning households and some are likely to receive meat at rituals and celebrations. However, the disservices are felt by the community at large which means that the livestock owners experience the benefits but not the full costs. Such a consideration could allow urban planners and managers to balance divergent preferences and priorities in urban spaces and recognise the point at which the trade-offs are acceptable by different groups of residents. Second, it is important to consider the socially embedded values and complexities of livestock husbandry. In other words, people are likely to experience, perceive and understand the services and disservices of livestock husbandry in urban spaces differently, as shaped by a complex interaction of social, economic and spatial factors that have their roots in the historical past (Shackleton et al. Citation2017). For example, Shackleton et al. (Citation2017) argue that urban municipal environmental management policies focussed on tree planting for decorating cities rather than investing in efforts to create inclusive spaces are likely to fail from multiple perspectives. If livestock husbandry is not considered in planning processes, urban greening efforts such as tree planting might fail due to animal damage as previously reported (Richardson and Shackleton Citation2014; Shackleton et al. Citation2017; Shackleton and Njwaxu Citation2021) which may result in wasteful expenditure and exacerbate negative perceptions of livestock husbandry (Butler Citation2012). Further, efforts to manage urban spaces might be undermined by lack of interest and participation by groups who make their livelihood from livestock husbandry and who may perceive urban spatial policies as exclusionary. This might be a disservice to efforts aimed at transforming urban spaces as integrative and inclusive (Venter et al. Citation2020).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we posit that it is important for city planners and managers to consider the trade-offs inherent in spatial planning in urban areas that are integrative of livestock husbandry. Given the diversity of perceptions on the matter, difficult decisions and choices have to be made, but involvement of residents representing different demographic groups and other stakeholders with an interest in community-engaged processes for transforming cities could allow multiple viewpoints to be reflected, and decisions to be acceptable to all (Landman Citation2016; Shackleton and Njwaxu Citation2021). In assessing the trade-offs between livestock services and disservices, it is important to use different methods of assessments given that some services, such as cultural services, might be not amenable to conventional quantitative cost-benefit analyses methods (Leach et al. Citation2013). Doing so might allow recognition of the socio-economic contexts within which the livestock services and disservices are experienced, perceived and contested or understood. We believe this could allow recognition of the complexity of urban environments as socially embedded spaces, and offer opportunities for genuine reflections, drafting of socially meaningful and environmentally-just policies and responsible actions by both city authorities and residents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the handling editor and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainslie A. 2005a. Keeping cattle? The politics of value in the communal areas of the Eastern Cape province, South Africa [PhD thesis]. London: University of London; p. 389.

- Ainslie A. 2005b. Farming cattle, cultivating relationships: cattle ownership and cultural politics in the Peddie District, Eastern Cape. Soc Dyn. 31:129–156. doi:10.1080/02533950508628699.

- Ainslie A. 2013. The sociocultural contexts and meanings associated with livestock keeping in rural South Africa. Af J Range Forage Sci. 30:35–38. doi:10.2989/10220119.2013.770066.

- Alarcón P, Fèvre E, Muinde P, Murungi MK, Kiambi S, Akoko J, Rushton J. 2017. Urban livestock keeping in the city of Nairobi: diversity of production systems, supply chains, and their disease management and risks. Front Vet Sci. 4:171. doi:10.3389/fvets.2017.00171

- Amadou H, Dossa LH, Lompo DJ-P, Abdulkadir A, Schlecht E. 2012. A comparison between urban livestock production strategies in Burkina Faso, Mali and Nigeria in West Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. 4(7):1631–1642. doi:10.1007/s11250-012-0118-0

- Anderson S. 2007. The economics of dowry and brideprice. J Econom Perspect. 21(4):151–174. doi:10.1257/jep.21.4.151

- Anderson S. 2014. Human capital effects of marriage payments. IZA World Labor. 77:1–10. [accessed 2021 Aug 17]. https://wol.iza.org/articles/human-capital-effects-of-marriage-payments.

- Ballard R. 2010. ‘Slaughter in the suburbs’: livestock slaughter and race in post-apartheid cities. Ethn Racial Stud. 33(6):1069–1087. doi:10.1080/01419870903477320

- Behera B, Rahut DB, Jeetendra A, Ali A. 2015. Household collection and use of biomass resources in South Asia. Energy. 85:468–480. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.03.059.

- Beudou J, Martin G, Ryschawy J. 2017. Cultural and territorial vitality services play a key role in livestock agroecological transition in France. Agronom Sustain Dev. 37(36):1–11. doi:10.1007/s13593-017-0436-8

- Butler WH. 2012. Welcoming animals back to the city: navigating the tensions of urban livestock through municipal ordinances. Journal Agric, Food Syst Commun Dev. 2(2):193–215. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2012.022.003

- Cundill G, Bezerra JC, De Vos A, Ntingana N. 2017. Beyond benefit sharing: place attachment and the importance of access to protected areas for surrounding communities. Ecosyst Serv. 28:140–148. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.03.011.

- Davenport NA, Gambiza J. 2009. Municipal commonage policy and livestock owners: findings from the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Land Use Policy. 26(3):513–520. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.07.007

- Davenport NA, Shackleton CM, Gambiza J. 2012. The direct use value of municipal commonage goods and services to urban households in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Land Use Policy. 29:548–557. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.09.008.

- Davenport N, Gambiza J, Shackleton CM. 2011. Use and users of municipal commonage around three small towns in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Environ Manage. 92:1149–1460. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.003.

- Doron A. 2020. Stench and sensibilities: on living with waste, animals and microbes in India. Australian J Anthrolpol. 32:23–41. doi:10.1111/taja.12380.

- Du-Pont T, Vilakazi M, Thondhlana G, Vedeld P. 2020. Livestock income and household welfare for communities adjacent to the great Fish River Nature Reserve, South Africa. Environ Dev. 33:100508. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100508.

- Foeken DWJ, Ouwor SO. 2008. Farming as a livelihood source for the urban poor of Nakuru, Kenya. GeoForum. 39:1978–1990. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.07.011.

- Graefe S, Schlecht E, Buerkert A. 2008. Opportunities and challenges of urban and peri-urban agriculture in Niamey, Niger. Outlook Agric. 37(1):47–56. doi:10.5367/000000008783883564

- Guendel S, Richards W. 2002. Peri-urban and urban livestock keeping in East Africa - a coping strategy for the poor. Scoping Study Comm DFID Nat Res Inst. 31 .

- Herd-Hoare S, Shackleton CM. 2020. Integrating ecosystem services and disservices in valuing smallholder livestock and poultry production in three villages in South Africa. Land. 9:9) 294. doi:10.3390/land9090294

- Herrero M, Grace D, Njuki J, Johnson N, Enahoro D, Silvestri S, Rufino M. 2013. The roles of livestock in developing countries. Animal. 7(1):3–18. doi:10.1017/S1751731112001954

- Herrero M, Thornton PK, Gerber P, Reid RS. 2009. Livestock, livelihoods and the environment: understanding the trade-offs. Curren Opin Environ Sustain. 1(2):111–120. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2009.10.003

- Jacobs R. 2018. An urban proletariat with peasant characteristics: land occupations and livestock raising in South Africa. J Peasant Stud. 45(5–6):884–903. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1312354

- Landman K. 2016. The transformation of public space in South Africa and the role of urban design. Urban Design Int. 21:78–92. doi:10.1057/udi.2015.24.

- Leach M, Raworth K, Rockström J. 2013. Between social and planetary boundaries: navigating pathways in the safe and just space for humanity. In: World Social Science Report 2013: changing Global Environments. Paris: OECD Publishing, Paris/UNESCO Publishing 84–89 . doi:10.1787/9789264203419-10-en

- Lee-Smith D. 2010. Cities feeding people: an update on urban agriculture in equatorial Africa. Environ Urban. 22(2):483–499. doi:10.1177/0956247810377383

- Lyytimäki J, Petersen LK, Normander B, Bezák P. 2008. Nature as a nuisance? Ecosystem services and disservices to urban lifestyle. Environ Sci. 5(3):161–172. doi:10.1080/15693430802055524

- Lyytimäki J, Sipilä M. 2009. Hopping on one leg–The challenge of ecosystem disservices for urban green management. Urban For Urban Greening. 8(4):309–315. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2009.09.003

- McClintock N, Pallana E, Wooten H. 2014. Urban livestock ownership, management, and regulation in the United States: an exploratory survey and research agenda. Land Use Policy. 38:426–440. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.12.006.

- Mucina L, Rutherford MC. 2006. . The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. . Pretoria, South Africa: South African National Biodiversity Institute. viii + 807 .

- Onyango E. 2016. The negative consequences of dowry payment on women and society. Priscilla Pap. 30:1. [accessed 2021 Aug 17]. https://www.cbeinternational.org/resource/article/priscilla-papers-academic-journal/negative-consequences-dowry-payment-women-and.

- Paniagua Á. 2014. Perspectives of livestock farmers in an urbanized environment. Land. 3:19–33. doi:10.3390/land3010019

- Parry K, van Eeden A. 2015. Measuring racial residential segregation at different geographic scales in Cape Town and Johannesburg. South Af Geograph J. 97(1):31–49. doi:10.1080/03736245.2014.924868

- Richardson E, Shackleton CM. 2014. The extent, causes and local perceptions of street tree damage in small towns in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Urban For Urban Greening. 13:425–432. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2014.04.003.

- Ryschawy J, Disenhaus C, Bertrand S, Allaire G, Aznar O, Plantureux S, Josien E, Guinot C, Lasseur J, Perrot C, et al. 2016. Assessing multiple goods and services derived from livestock farming on a nation-wide gradient. Animal. 11(10):1861–1872. doi:10.1017/S1751731117000829

- Schiere H, van der Hoek R. 2001. Livestock keeping in urban areas: a review of traditional technologies based on literature and field experiences. Food & Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Animal Production and Health Paper, 151.

- Shackleton CM, Guild J, Bromham B, Impey S, Jarrett M, Ngubane M, Steijl K. 2017. How compatible are urban livestock and urban green spaces and trees? An assessment in a medium-sized South African town. Int J Sustain Urban Dev. 9:243–252. doi:10.1080/19463138.2017.1314968.

- Shackleton CM, Gwedla N. 2021. The legacy effects of colonial and apartheid imprints on urban greening in South Africa: spaces, species and suitability. Fron Ecol Evol. 8:579813. doi:10.3389/fevo.2020.579813.

- Shackleton CM, Njwaxu A. 2021. Does the absence of community involvement underpin the demise of urban neighbourhood parks in the Eastern Cape, South Africa? Landsc Urban Plan. 207:104006. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.104006.

- Shackleton CM, Shackleton SE, Netshiluvhi TR, Mathabela FR. 2005. The contribution and direct-use value of livestock to rural livelihoods in the Sand River catchment, South Africa. Af J Range Forage Sci. 22(2):127–140. doi:10.2989/10220110509485870

- Siegner A, Sowerwine J, Acey C. 2018. Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the Nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: a systematic review. Sustainability. 10(9):2988. doi:10.3390/su10092988

- Statistics South Africa. 2012. Census 2011: census in brief. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Stemler S. 2000. An overview of content analysis. Pract Assess, Res, Evaluat. 7(17) :1–6.

- Strauss M. 2019. A historical exposition of spatial injustice and segregated urban settlement in South Africa. Fundamina. 25(2):135–168. doi:10.17159/2411-7870/2019/v25n2a6

- Thondhlana G, Vedeld P, Shackleton S. 2012. Natural resource use, incomes and dependence amongst the San and Mier communities bordering Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park in the southern Kalahari, South Africa. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 19(5):460–470. doi:10.1080/13504509.2012.708908

- Thornton A. 2008. Beyond the metropolis: small town case studies of urban and peri-urban agriculture in South Africa. Urban Forum. 19:243–262. doi:10.1007/s12132-008-9036-7.

- Thys E, Oueadraogo M, Speybroeck N, Geerts S. 2005. Socio-economic determinants of urban household livestock keeping in semi-arid Western Africa. J Arid Environ. 63(2):475–496. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.03.019

- Venter ZS, Shackleton CM, Van Staden F, Selomane O, Masterson VA. 2020. Green Apartheid: urban green infrastructure remains unequally distributed across income and race geographies in South Africa. Landsc Urban Plan. 203:103889. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103889.

- Withnall A. 2019. Inside India’s plastic cows: how sacred animals are left to line their stomachs with polythene. [accessed 2021 Aug 18]. https://bit.ly/3luRB6M.