1. Introduction

Ecosystem restoration has become increasingly prominent in global, national and regional treaties, coalitions and conventions. Significantly, 2021 marked the beginning of the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (UNEP and FAO Citation2020). This strategy aims to engage actors from all spheres of society to overcome political, socioeconomic and technical barriers to implementing ecosystem restoration at multiple scales. However, it demands transdisciplinary approaches to address its inherently complex and multi-dimensional implementation (Cengiz et al. Citation2019; Mansourian and Parrotta Citation2019).

Some challenges to implementing ecosystem restoration in Latin America emerge due to its particular political and social-ecological context. Major environmental challenges in Latin America occur in rural landscapes and are not related to livelihood improvements but survival; the dichotomy is survival versus conservation (Gligo Citation2001). The average percentage of Latin American people living in multi-dimensional poverty in rural areas is high (52.6%). There is a huge difference among countries. For instance, Honduras and Guatemala hold 82% and 77% of rural poor, while Uruguay and Chile only 2% and 7%, respectively (FAO Citation2018). This social problem is associated with ecological degradation since Latin America is one of the three regions where deforestation has advanced the most (FAO Citation2018). Due to the joint impacts of poverty and deforestation, the communities’ cultural identity and forms of social reproduction are weakened, given the fragmentation of their societies and landscapes.

Besides, as the total population in Latin American countries continues to increase, extensively natural ecosystems are still converted to pastures for low-density livestock and crops. The future of these ecosystems will depend on how the region responds to this conversion. In this sense, ecosystem restoration is gaining momentum on the political agenda. Thirteen of 28 Latin American countries signed an agreement in 2014 to restore 20 million hectares by 2020 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 (https://initiative20x20.org). These political aspirations have the potential to create jobs, increase environmental values and capture from 4.5 to 8.8 billion tons of annual CO2 emissions by 2030 (Suding et al. Citation2015). However, only five signatory countries currently count on a policy instrument (for example, a restoration plan) to achieve the objectives proposed (Méndez-Toribio et al. Citation2017; Assad et al. Citation2020).

This scenario has prompted Latin American scientists to rethink their paradigms as they face decades of economic crisis, poverty, social and agrarian injustice, migration, biodiversity loss, climate threats, civil wars, narcotraffic violence, and many other consequences of sustainable development goals. Thus, a perspective focusing on the interaction between social and ecological systems is emerging strongly in Latin America to understand better the complexity of this crisis, exacerbated by global climatic and ecological changes (Castro-Díaz et al. Citation2019).

Managing the current human-modified landscapes in Latin America to restore ecosystems while maintaining ecosystem services to produce human well-being is crucial to promoting win-win schemes for the environment and societies (Meyfroidt et al. Citation2010). This Special Issue presents five papers featuring cases and viewpoints of those working on ecosystem restoration to produce human well-being and associated issues such as governance and social participation in the region.

2. Linking ecosystem restoration and human well-being in Latin America

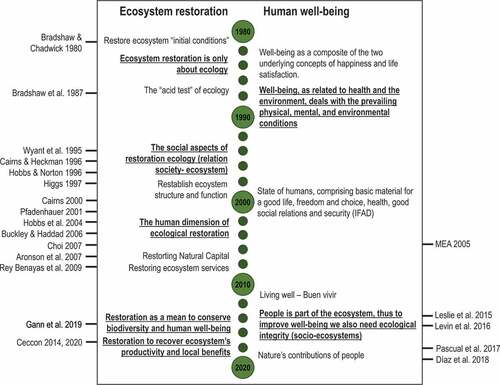

Ecological restoration consolidated as a discipline during in the last two decades of the 20th century, with some definitions by Bradshaw (and his colleagues) about restoration being the ‘acid test’ of ecology (). Since this origin, ecological restoration has considered the social aspects of human society (Wyant et al. Citation1995; Cairns and Heckman Citation1996; Hobbs and Norton Citation1996; Gann et al. Citation2019) and even its impacts on sustainable development (Urbanska et al. Citation1997). The ‘human dimension’ of restoration was brought out to discussion during the first decade of the 21st century (Pfadenhauer Citation2001; Hobbs et al. Citation2004). During this decade, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Citation2005) highlighted the importance of ecosystem services to maintain people’s well-being and poverty alleviation. By this moment, the human dimension of restoration is fully embraced in the theoretical discussion (Choi Citation2007) and also in the practice, for instance in terms to find a ‘socially strategic restoration’ (Buckley and Haddad Citation2006).

Figure 1. An schematic chronology of concepts, ideas, and topics (underlined) relating to ecosystem restoration and human well-being since the consolidation of ecological restoration as a discipline. References out of the box are examples of the topics represented among the different decades.

The ecosystem services concept gained importance in restoration when in 2009, Rey Benayas et al. (Citation2009) gave an empirical precedent on how restoration may recover biodiversity and ecosystem services, providing an implicit and subsequent link on the potential benefits of restoration on human well-being (Alexander et al. Citation2016). The use of the ecosystem services concept in the restoration context in Latin America thus came together with notions such as ‘natural capital’, ‘economic values’, and ‘tangible benefits and goods’ (e.g. Aronson et al. Citation2007; Blignaut et al. Citation2014). These notions were incorporated through programs and policies involving market-based schemes, such as payments, compensations, tax redemptions, economic incentives, and subsidies, supported by increasingly prominent global, national and regional treaties, coalitions, and conventions (e.g. Bonn Challenge and 20 × 20 Initiative).

Recently, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) proposed the term ‘nature contributions to people’ (NCP), a notion that recognises a range of representations of worldviews, interests, and values, highlighting how critical inclusive framings are to the broad political legitimacy of the international objectives and their implementation instruments (Pascual et al. Citation2017; Díaz et al. Citation2018). The NCP approach recognises the central and pervasive role that culture plays in defining all links between people and nature and elevates, emphasises, and operationalises the role of indigenous and local knowledge in understanding nature’s contribution to people (Díaz et al. Citation2018). Thus, in the NCP notion, the cultural visions permeate through and across the NCP rather than being confined to an isolated category, and the main NCP groups – rather than being independent compartments, as typically framed within the ecosystem services approach (MA 2005)—explicitly overlap. In this sense, ecosystem restoration interventions must result from decisions taken together with local inhabitants by considering their wishes, customs, spirituality, knowledge, and laws. However, this cultural dimension of ecosystem services remains less developed when compared with the ecological dimension (Musacchio Citation2013).

In the last ten years, other concepts have gained a place in the environmental discussion in Latin America and could also sound for linking ecosystem restoration and human well-being. For instance, the buen vivir, in its most general sense, constructs a life system based on the communion of beings (human and otherwise) and nature (Mahali et al. Citation2018). It points toward a correlation, complementarity and reciprocity with the rest in harmony, respect, dignity and continuous relation. In this sense, the individual is not separate from but an integral part of nature. This plural concept, still under construction, is not limited to indigenous worldviews. However, it provides a platform for a political debate on the alternatives to development, where even though there is a diversity and overlapping of different positions, there are critical elements in common, and it questions the bases of the conventional conceptions of development (Gudynas Citation2011). Another concept is ‘productive restoration’, as a strategy to recover soil productivity, together with some elements of the structure and function of the original ecosystem, to offer tangible benefits to the local population (Ceccon Citation2014, Citation2020). Productive restoration has been used in Colombia, Argentina, and Chile.

All these concepts go hand-by-hand with the principles of sustainability; but this should also be a ‘shared sustainability’ (Leff Citation2002) that summons all the social actors (governments, academics, private sector, peasants, indigenous people, citizens) to a joint effort in an operating agreement and participation in which different visions are integrated (Ceccon and DR Citation2017). Nature must maintain its quality and harmony to harbour the human being, who is an absolute part of it. Humans do not use nature (or mother earth) but instead, nurture it and allow themselves to be nurtured in the sense of mutual protection born of affection that emerges when one and the other are a constituent part (Gerritsen et al. Citation2018). Under these visions, the Earth is understood as a constantly renewing source of gifts; humans have a responsibility to reciprocate for all they have been given, while non-human species with which we share the planet are recognised as non-human persons, as relatives, and indeed as teachers (Kimmerer Citation2017).

Even with the increasing interest in academic, governmental, and non-governmental circles worldwide in developing universal definitions of well-being, searching for a theoretical definition could be fruitless in Latin America (Artaraz and Celestani Citation2015). Most restoration in Latin America occurs in poor rural areas (Chazdon et al. Citation2021). In this region, including the human dimension in the restoration is an ineludible process, and its goals and practices must be value-filled activities involving human perceptions, beliefs, emotions, knowledge, and behaviours (Higgs Citation2011). As different groups of actors rarely share the same norms and values, and power relations are unevenly distributed, conflicts around natural resource management are frequently generated, which may hinder efficient restoration (de Castro et al. Citation2016). Below we present the five papers included in this Special Issue and how they include this human dimension of restoration to embrace diverse human perceptions, to ultimately link ecosystem restoration and human well-being.

3. Studies included in this special issue

The practical approaches to link ecosystem restoration and human well-being may be diverse. The five studies in this Special Issue help address these practical approaches and help answer three main questions (). First, how have ecosystem restoration initiatives in Latin America considered ecosystem services and their contributions to the well-being of multiple social actors? Second, how have these ecosystem restoration initiatives included marginalised actors (such as women, indigenous communities, and afro-communities)? And furthermore, what are the enablers and constraints to bolster the link between ecosystem restoration and human well-being? We describe each study below and provide a comparison leading to some conclusions about reinforcing the link between ecosystem restoration and human well-being in Latin America.

Table 1. Summarised information on the three mains questions of the special issue in each paper.

Carrasco Henríquez and Mendoza Leal (Citation2021) describe the articulation of collaborative relationships between local communities and the private sector in the temperate forests of Southern Chile. Their study reveals how a group of local women (i.e. peasants and small-scale farmers) from the ‘Cordillera de Nahuelbuta’ moved forward with a restoration process that involved several stakeholders, which not only advanced ecological recovery but, most importantly, turned into a form of ‘re-communalization’, bringing well-being through building cultural identity. Using qualitative and ethnographic methodologies to collect and analyse the perspectives of various actors (including these leading women), they show that the obstacles that may impede further development and sustainability of the experience arise in the difficulties of maintaining permanent coordination with the private sector and whether they value the sustainability of these initiatives. As a result, women built a ‘restoration cooperative’. This experience is highly relevant for socio-ecological studies since restoration initiatives can integrate disparate interests responding to distinct paradigms of nature and economy.

Farinaccio et al. (Citation2021) describe a social assessment of native flora and its implications for ecological restoration in the Patagonian desertified drylands of Argentina. Through semi-structured surveys and open interviews, they show rural people’s knowledge (locally called ‘puesteros’) about the native flora, the value people give to the species and their interest in planting those species on their farms. In the surveys, puesteros mentioned 44 multipurpose species classified by their uses, while almost all of them expressed interest in planting on their farms. They found that immersed in unfavourable socio-ecological and cultural contexts, the puesteros recognise a low percentage of native useful species. At the same time, use a large proportion of exotic species as a result of the historic extermination of indigenous people and cultural erosion. However, local people expressed motivation and interest in ecosystem restoration. A cultural and productive restoration program focusing on restoration-based education may help implement these projects successfully and build well-being by strengthening local capacities, rescuing traditional knowledge, and increasing collective learning to ultimately restore the historical links between local people and the natural ecosystem.

Gómez-Ruiz et al. (Citation2022) describe how to restore the human-ecosystem link in the ecological restoration of the mangroves in Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve, in Mexico, by closely involving two local communities in all phases of the restoration process. During the planning phase, they identified local needs and interests to determine the project’s viability and performed social and ecological diagnostics to further involve community members in the restoration actions during the implementation phase. People participated in the reforestation activities and restoring water flow dynamics in parallel with training workshops focused on ecosystem services, ecological restoration, and monitoring techniques. With guidance from the project team, community members conducted initial monitoring of restoration actions four months after implementation. The local communities’ participation in all stages was fundamental to promoting an integrated and sustainable socio-ecosystem restoration process and fostering greater awareness of mangroves’ full range of services.

In the contribution by Cotroneo et al. (Citation2021), forest replacement and degradation driven by crop expansion and livestock intensification are some of the leading global socio-ecological threats severely affecting the dry Chaco region in Argentina. By involving stakeholders whose actions are decisive in dealing with the problem under analysis, the authors assessed the interactions among processes of multiple dimensions and spatial scales, currently controlling communal forest degradation in 11 peasant communities in Santiago del Estero province. Then, by reconstructing the historical processes undergone by these communities over the last century, they showed how different system settings have conducted to the system collapse (forests and community loss) or strengthened its adaptive capacity facing natural disturbances (droughts) and anthropogenic stressors (economic shocks, land disputes). The study unveils system attributes related to native resource management and economic diversification on the farm, family and community structure, and social networking with peasant organisations and other institutions, which are crucial for building social-ecological resilience. Thus, its results explain why forest (protection) law and state subsidies for sustainable management have been insufficient and suggest some insights to reorient them and promote restoration.

Finally, Aguiar et al. (Citation2021) present a perspective piece of work on the challenges and options to foster the link between forest and landscape restoration to human well-being in Latin America. They describe how the particularities of the Latin American context in terms of how we practice and evaluate the impacts of ecological restoration determine four challenges to better link forest restoration and human well-being in Latin America: (1) the high dependence of local communities and countries’ economies on natural resources, (2) conflicts over land tenure and access, (3) divergence in perceptions and values, and (4) the fragility of public institutions and policies. Finding an equitable and legitimate balance between global interests and urgency and increasing local well-being is the main challenge of forest restoration in Latin America to tackle by implementing instruments and approaches recently organised under transformative governance.

4. Concluding remarks

Attempts to contribute to human well-being require disaggregated analyses that recognise the different groups who benefit from each ecosystem service, the access mechanisms determining who benefits, and the individual contexts and aspirations determining how well-being is improved. The ecological and political dimensions of ecosystem restoration should be integrated, considering the mutual influences between political control, the social distribution of access to natural resources, and the associated biophysical processes. Because the practice of ecological restoration presents a series of issues and uncertainties, it requires ongoing learning and negotiation instead of a unique solution for a single problem. In this sense, ecological restoration must be a humanistic project to reach new human values regarding nature (Ceccon et al. Citation2020). Including the human dimension in restoration is an inescapable process, and its goals and practices must be value-filled activities involving human perceptions, beliefs, emotions, knowledge, and behaviours. Engagement could be broadened and deepened to reinforce the link between ecosystem restoration and human well-being, reinforcing networks of scientific persons and programs which may directly connect to essential issues to human well-being (e.g. linking to Future Earth 2013). Furthermore, ecosystem restoration in Latin America needs to be more strongly transdisciplinary and include the highest possible levels of governmental actors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguiar S, Mastrángelo ME, Brancalion PH, Meli P. 2021. Transformative governance for linking forest and landscape restoration to human well-being in Latin America. Ecosystem and People. 17:523–538. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1976838.

- Alexander S, Aronson J, Whaley O, Lamb D. 2016. The relationship between ecological restoration and the ecosystem services concept. Ecology and Society. 21(1):34. doi:10.5751/ES-08288-210134.

- Aronson J, Milton SJ, Blignaut JN. 2007. Restoring natural capital: science, business and practice. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Artaraz K, Celestani M. 2015. Suma qamaña in Bolivia. Indigenous understandings of well-being in their contribution to a post-Neoliberalism paradigm. Lat Am Perspect. 204(42):216–233. doi:10.1177/0094582X14547501.

- Assad ED, Costa LC, Martins S, Calmon M, Feltran-Barbiera R, Campanili M, Nobre CA. 2020. Role of the ABC plan and planaveg in the adaptation of crop and cattle farming to climate change. Working Paper. São Paulo, Brazil: WRI Brasil. Available online at: https://wribrasil.org.br/pt/publicacoes

- Blignaut J, Aronson J, de Groot R. 2014. Restoration of natural capital: a key strategy on the path to sustainability. Ecol Eng. 65:54–61. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.09.003.

- Bradshaw AD. 1987. Restoration: an acid test for ecologyIn: Jordan WR, Gilpin ME Aber JDRestoration Ecology. Cambridge UK:Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–29.

- Bradshaw AD, Chadwick MJ. 1980. The restoration of lands: the ecology and reclamation of derelict and degraded land. California: University California Press.

- Buckley M, Haddad BM. 2006. Socially strategic ecological restoration: a game-theoretic analysis shortened: socially strategic restoration. Environ Manage. 38:48–61. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0165-7.

- Cairns J. 2000. Setting ecological restoration goals for technical feasibility and scientific validity. Ecol Eng. 15:171–180. doi:10.1016/S0925-8574(00)00068-9.

- Cairns J, Heckman JR. 1996. Restoration ecology: the state of an emerging field. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 21:167–189. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.21.1.167.

- Carrasco Henríquez N, Mendoza Leal C. 2021. Restoration as a re-commoning process. Territorial initiative and global conditions in the process of water recovery in the ‘Cordillera de Nahuelbuta. Chile, Ecosystems and People. 17:556–573. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1993345.

- Castro-Díaz R, Perevochtchikova M, Roulier C, Anderson CB. 2019. Studying social-ecological systems from the perspective of social sciences in Latin America. In: Castro-Díaz R, Perevochtchikova M, Roulier C, Anderson CB, editors. Social-ecological sysTems of latin america: complexities and challenges. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; p. 73–93.

- Ceccon E. 2014. Restauración En bosques tropicales: fundamentos ecológicos, prácticos y sociales. Mexico City (Mexico): Ediciones Díaz de Santos.

- Ceccon E. 2020. Productive restoration as a tool for socio-ecological landscape conservation: the case of “La Montaña” in Guerrero, Mexico. In: Baldauf C, editor. Participatory biodiversity conservation. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG. pp. 113–128.

- Ceccon E, DR P (coords.). 2017. Beyond restoration ecology: social perspectives in Latin America and the Caribbean. Buenos Aires (Argentina): Vázquez Mazzini Editores.

- Ceccon E, Rodríguez León CH, Pérez DR. 2020. Could 2021–2030 be the decade to couple new human values with ecological restoration? Valuable insights and actions are emerging from the Colombian Amazon. Restoration Ecology. 28:1036–1041. doi:10.1111/rec.13233.

- Cengiz S, Atmiş E, Görmüş S. 2019. The impact of economic growth oriented development policies on landscape changes in Istanbul Province in Turkey. Land Use Policy. 87:104086. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104086.

- Chazdon RL, Wilson SJ, Brondizio E, Guariguata MR, Herbohn J. 2021. Key challenges for governing forest and landscape restoration across different contexts. Land Use Policy. 104:104854. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104854.

- Choi YD. 2007. Restoration ecology to the future: a call for new paradigm. Restoration Ecology. 15:351–353. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.2007.00224.x.

- Cotroneo SM, Jacobo EJ, Brassiolo MM. 2021. Degradation processes and adaptive strategies in communal forests of Argentine dry Chaco. Integrating Stakeholder Knowledge and Perceptions, Ecosystems and People. 17:507–522. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1972042.

- de Castro F, Hogenboom B, Baud M, editors. 2016. Environmental governance in Latin America. Hampshire UK: Palgrave McMillan.

- Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López B, Watson RT, Molnár Z, Hill R, Chan KMA, Baste IA, Brauman KA, et al. 2018. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science. 359(6373):270–272. doi:10.1126/science.aap8826.

- FAO. 2018. Panorama de la pobreza rural en América Latina y el Caribe 2018. Rome (Italy): CEPAL - Naciones Unidas; p. 112.

- Farinaccio FM, Ceccon E, Pérez DR. 2021. Starting points for the restoration of desertified drylands: puesteros’ cultural values in the use of native flora. Ecosystems and People. 17:476–490. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1968035.

- Gann GD, McDonald T, Walder B, Aronson J, Nelson CR, Jonson J, Hallett JG, Eisenberg C, Guariguata MR, Liu J, et al. 2019. International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. In: Restoration ecology S1-S46. 2nd ed. doi:10.1111/rec.13035.

- Gerritsen PRW, Rist S, Morales Hernández J. 2018. Multifuncionalidad, sustentabilidad y buen vivir. Miradas desde Bolivia y México. In: Ponce NT, editor. Departamento de ecología y recursos naturales – IMECBIO, centro universitario de la costa. Sur, Universidad de Guadalajara: Guadalajara; p. 350.

- Gligo N. 2001. La dimensión Ambiental en el desarrollo de América Latina. Santiago (Chile): CEPAL - Naciones Unidas.

- Gómez-Ruiz PA, Betancourth-Buitrago RA, Arteaga-Cote M, Carbajal-Borges JP, Teutli-Hernández C, Laffon-Leal S. 2022. Fostering a participatory process for ecological restoration of mangroves in pantanos de centla biosphere reserve (Tabasco, Mexico). Ecosystems and People. 18:112–118. doi:10.1080/26395916.2022.2032358.

- Gudynas E. 2011. Buen Vivir: today’s tomorrow. Development. 54:441–447. doi:10.1057/dev.2011.86.

- Higgs ES. 1997. What is good ecological restoration? Conservation Biology. 11:338–348. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.95311.x.

- Higgs ES. 2011. Foreword to human dimensions of ecological restoration: integrating science, nature and culture. David E, Hjerpe EE Abrams J, editors. Washington D.C: Island Press.

- Hobbs RJ, Davis MA, Slobodkin LB, Lackey RT, Halvorson W, Throop W. 2004. Restoration ecology; the challenge of social values and expectations. Front Ecol Environ. 2:43–44. doi:10.2307/3868294.

- Hobbs RJ, Norton DA. 1996. Towards a conceptual framework for restoration ecology. Restoration Ecology. 4:93–110. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.1996.tb00112.x.

- Kimmerer RW. 2017. The covenant of reciprocity. In: Hart J, editor. The Wiley Blackwell companion to religion and ecology. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; p. 368–381.

- Leff E. 2002. La transición Hacia el desarrollo sustentable: perspectivas de América Latina y el Caribe 6. Mexico City (Mexico): Instituto Nacional de Ecología.

- Leslie HM, Basurto X, Nenadovic M, Sievanen L, Cavanaugh KC, Cota-Nieto JJ, Erisman BE. 2015. Operationalising the social-ecological systems framework to assess sustainability. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 112:5979–5984. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414640112.

- Levin PS, Breslow SJ, Harvey CJ, Norman KC, Poe MR, Williams GD, Plummer ML. 2016. Conceptualisation of social-ecological systems of the California current: an examination of interdisciplinary science supporting ecosystem-based management. Coastal Management. 44:397–408. doi:10.1080/08920753.2016.1208036.

- Mahali A, Lynch I, Fadiji AW, Tolla T, Khumalo S, Naicker S. 2018. Networks of well-being in the global South: a critical review of current scholarship. J Dev Soc. 34:373–400. doi:10.1177/0169796X18786137.

- Mansourian S, Parrotta J. 2019. From addressing symptoms to tackling the illness: reversing forest loss and degradation. Environmental Science & Policy. 101:262–265. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2019.08.007.

- Méndez-Toribio M, Martínez-Garza C, Ceccon E, Guariguata MR. 2017. Planes actuals de restauración ecológica en Latinoamérica: avances y omisiones. Rev Cienc Ambient. 51:1–30. doi:10.15359/rca.51-2.1.

- Meyfroidt P, Rudel TK, Lambin EF. 2010. Forest transitions, trade, and the global displacement of land use. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:20917–20922. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014773107.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. Washington (DC): Island Press; 137 pp.

- Musacchio LR. 2013. Cultivating deep care: integrating landscape ecological research into the cultural dimension of ecosystem services. Landsc Ecol. 28:1025–1038. doi:10.1007/s10980-013-9907-8.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Díaz S, Pataki G, Stenseke M, Watosn RT, Dessane EB, Islar M, Kelemen E, Maris V, et al. 2017. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach. Current Opinion in Environment and Sustainability. 26-27:7–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006.

- Pfadenhauer J. 2001. Some remarks on the socio-cultural background of restoration ecology. Restoration Ecology. 9:220–229. doi:10.1046/j.1526-100x.2001.009002220.x.

- Rey Benayas JM, Newton AC, Días A, Bullock JM. 2009. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: a meta-analysis. Science. 325:1121–1124. doi:10.1126/science.1172460.

- Suding K, Higgs E, Palmer M, Baird Callicott J, Anderson CB, Baker M, Gutrich JJ, Hondula KL, LaFevor MC, Larson BMH, et al. 2015. Committing to ecological restoration. Science. 348:6235. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4216.

- UNEP and FAO. 2020. Strategy for the UN decade on ecosystem restoration. united nations environment programme (UNEP) and food and agriculture organization of the united nations (FAO). Nairobi and Rome. https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/strategy.

- Urbanska KM, Webb NR, Edwars PJ. 1997. Restoration ecology and sustainable development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wyant JG, Meganck RA, Ham SH. 1995. A planning and decision-making framework for ecological restoration. Environ Manage. 19:789–796. doi:10.1007/BF02471932.