ABSTRACT

The transformations required to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals across the African continent demand new ways of mobilising, weaving together, and applying knowledge. Research, policymaking, planning, and action must be effectively inter-linked to address complex sustainability challenges and the different needs and interests of societal actors. Transdisciplinarity (TD) – the co-production of knowledge across disciplines and with non-academic actors – offers a promising, holistic approach to foster such transformations. Yet, despite increased application of TD over the past two decades, disciplinary and sectoral silos persist. TD is not well embedded in African academic institutions and, consequently, much SDG-related research is too narrowly framed and divorced from the action space to be effective. There is an urgent need to work collectively across disciplines and society for transformation towards more sustainable and equitable development pathways. Capacities to undertake collaborative, impactful research must be strengthened, and changes in research culture are needed to support relationship building. We explore these issues by drawing on two recent online social learning processes with researchers and practitioners working on sustainability issues and TD. In each process, we built on actors’ own experiences of TD by investigating institutional, practical, and theoretical challenges and enablers of TD. Here, we synthesise our learnings, alongside key literature, and explore avenues to better: a) promote and support TD within academic institutions across Africa; b) resource TD for sustainable partnerships, and c) strengthen TD practices and impacts to support transformation to sustainability across diverse places and contexts.

Edited by:

1. Introduction

Humanity is currently facing unprecedented sustainability challenges that are multifaceted, interconnected, and dynamic (Liu et al. Citation2015; Brondízio et al. Citation2019; Risopoulos-Pichler et al. Citation2020; Folke et al. Citation2021). The evidence for human-nature connectedness is mounting as climate change, biodiversity loss, and zoonotic diseases in the context of high levels of inequality and unsustainable economic growth precipitate considerable hardships, deaths, displacement, and costly economic and infrastructural losses (Steffen et al. Citation2015a; Future Earth Citation2020; Thorn et al. Citation2020; Lawler et al. Citation2021). In Africa, major demographic transitions, notably rapid urbanisation, are compounding persistent historical inequalities and exploitation, resulting in critical development challenges such as malnutrition, high levels of unemployment, and limited access to education, public infrastructure, and social services (Juju et al. Citation2020; Thorn et al. Citation2021). Without sustainability and equity, development becomes self-destructive as it threatens to undermine the fundamental life-support system upon which humanity relies (Steffen et al. Citation2018; Lenton et al. Citation2019; Rockström et al. Citation2021; Armstrong McKay et al. Citation2022).

In response to these challenges, governments globally have agreed on a collective set of aspirations articulated as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 17 SDGs represent an ambitious effort to achieve sustainability through an evidence-based framework for development planning until 2030 (United Nations General Assembly Citation2015; Wackernagel et al. Citation2017). These goals recognise that human development and well-being rely on the healthy functioning of the earth’s ecological and geophysical systems and the collective prosperity of all peoples (Griggs et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Barnosky et al. Citation2014; Steffen et al. Citation2018). The SDGs provide a normative framework aimed at addressing complex development challenges within recognised planetary boundaries and transforming society in ways that put an end to poverty, conserve ecosystems and improve health and well-being for all (Steffen et al. Citation2015b; UNDP Citation2018). While the SDGs put forward global sustainability ambitions, concerns have been raised about their coordinated implementation across Africa (Juju et al. Citation2020). While achieving the SDGs seems a daunting task, it is critical for securing the future of African people and nature. Africa consists of young and dynamic populations with rich cultural and ecological diversity that can contribute to this imperative.

The SDGs have been critiqued for their lack of integration and for reinforcing siloed approaches, pointing to a need for understanding sustainability challenges and ecosystem management in more integrated ways. Thus, realising the SDGs requires new ways of generating and implementing knowledge linked to actions that work with the complex, interconnected nature of social-ecological systems and the diverse perspectives, needs and interests of different societal actors (Hadorn et al. Citation2006; Seidl et al. Citation2013; OECD Citation2020; Yamazumi Citation2020). Disciplinary approaches to knowledge production have yielded considerable advances and benefits that underpin societal progress, especially in medical science and computing, for example. Yet, this disciplinary specialisation can also silo knowledge, creating blind spots regarding the interconnections between nature, people, and their knowledge systems and culture (Kinzig Citation2001). This contributes to maintaining and creating power imbalances that fuel the extreme economic inequities that undermine key life-support systems (Brondízio et al. Citation2019). SDG-related research needs to be more broadly framed and directly engaged with action arenas to address interconnected challenges (McGowan et al. Citation2019). Consequently, there is a growing need for transformative, inclusive, and decolonised forms of knowledge production, tied to learning and shifting values and behaviours, to shape new, more sustainable policies, processes, and practices across Africa (Vogel and O’Brien Citation2022).

Transdisciplinarity (TD), including knowledge co-production and co-design, offers a promising approach to facilitate the type of knowledge production needed to support more equitable and sustainable development pathways in Africa, as well as a way to apply the interconnected, nexus framings so necessary for solving complex sustainability challenges (Steger et al. Citation2021). We understand TD to encompass ways of undertaking research that intentionally transcends the boundaries within science and between science and other social and economic spheres, to connect knowledge with action (Klein Citation2013; Knapp et al. Citation2019). TD entails tackling complex and contextually contingent problems, valuing epistemological plurality, and actively involving knowledge holders from outside of academia – operating in civil society organisations, government, business, and industry – in processes of reflection, formulating questions, selecting methods, collecting and analysing data, sharing, learning and producing new knowledge (Darbellay Citation2015; Fam et al. Citation2018). Experiential and practice-based knowledge is considered of equal value to scientific knowledge in framing questions, collecting data, sense-making, and developing and testing potential responses to complex problems. TD is thereby a social process of collaborative problem-solving and mutual learning. TD is designed to characterise and tackle problems of shared concern and co-produce solution-oriented, socially robust, and scientifically defensible knowledge in ways that build the legitimacy, ownership and operationalisation or enactment of that knowledge (Popa et al. Citation2015; Scholz and Steiner Citation2015). TD and knowledge co-production processes are framed by and respond to real-world challenges and are increasingly recognised as essential for achieving the SDGs (McGowan et al. Citation2019; Schneider et al. Citation2019; Thondhlana et al. Citation2021). The diversity of perspectives and heterogeneity of people involved is a key feature of TD (Steger et al. Citation2021), while the superiority of academic knowledge is challenged (Lutz and Neis Citation2008; Lotz-Sisitka et al. Citation2015). By emphasising the relational nature of sustainability knowledge, TD facilitates new cross-cutting networks to respond to emergent challenges (Bergmann et al. Citation2012). TD, when mindfully applied, can also provide a route towards transformative change at multiple scales from local to national by enabling learning, altering power dynamics and building collective and individual agency to tackle complex sustainability problems (Marshall et al. Citation2018).

Despite increasing recognition of the value of TD, disciplinary, organisational and sector silos and fragmentation persist, making more inclusive and transformative ways of producing actionable knowledge difficult (Lawrence et al. Citation2022). Few universities nurture the critical skills and mindsets that enable the relational capacities, reflexivity, communication skills and empathy required for TD work (Fam et al. Citation2018; Salgado et al. Citation2018). There is, thus, an urgent need to further understand how to work across disciplines and other ways of knowing to build more inclusive and just development pathways. Building such development pathways entails the intentional and collective sequencing of evidence-based actions and innovations, implemented progressively depending on emerging future dynamics (Aguiar et al. Citation2020). It also requires surfacing and challenging existing power asymmetries in how knowledge is mobilised, produced, and applied, and who benefits or is burdened by the application (Lotz-Sisitka et al. Citation2015). Given the escalated impacts from extreme climate events and compounded poverty and inequality, there is an urgency to strengthen capacities to undertake this type of collaborative research.

Recognising this need for change in how research of and for sustainability is undertaken and in strengthening the capacities to undertake collaborative and impactful research, this paper advances an understanding of TD that recognises the diversity of local contexts across the African continent. We lay out a set of institutional, resourcing, and praxis priorities to promote and support excellent TD research in African universities. Such change is essential to foster the institutional culture, support structures, and trusting partnerships within and outside the academy that are needed to address complex sustainability problems. We draw on six case studies and the conversations, observations, and insights from two independent social learning processes held in 2020 and 2021 (during the COVID-19 pandemic). Each process involved a series of online workshops with a range of actors directly concerned with sustainability issues to explore how to achieve transdisciplinary research that tackles sustainability concerns and builds trusting, collaborative partnership for transformative change. We built on participants’ own experiences of engaging in TD by exploring institutional, funding, and theoretical and praxis challenges and enablers of TD, as well as potential options for improving practice, recognising that these categories are highly interconnected.

This paper proceeds by describing the two collaborative learning processes. In the sections that follow, we synthesise insights and reflections surfaced from the learning processes, alongside key literature, in a narrative in which we explore avenues to better embed TD in African academic institutions and support more transformative practice. Specifically, we offer suggestions on how to better: a) promote and support TD within academic institutions across Africa; b) resource TD for sustainable partnerships, and c) strengthen TD practice and impacts to support transformation to sustainability across diverse places and contexts. We conclude the paper with a set of summarised recommendations on how to support TD practice and multi-scalar partnerships across Africa and beyond.

2. Description of the social learning processes

The two multi-actor engagement and collective (social) learning processes that provide the insights and learnings for this paper were designed for different purposes and operated at different scales. The first process described below – the SDG summit workshops – included presentation of six case studies from across Southern and Eastern Africa and African and international discussants and participants. It thus provided a macro-level perspective on TD practice in Africa and beyond. The second process – the Berg-Breede community of practice (COP) - involved online reflections with actors working within a catchment area in the Western Cape of South Africa, thus delivering a deeper understanding and more context-specific insights on TD, with strong representation from practitioners. Despite the differences, both processes ultimately aimed to explore ways to improve TD practice for more impactful and transformative outcomes that help progress the SDGs. Both surfaced common issues and priorities.

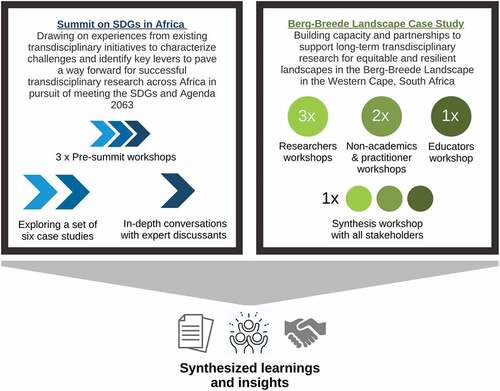

The first learning process involved co-developing a ‘positioning paper’ and two sessions for a Summit on the SDGs in Africa hosted by the University of Cape Town in September 2021. We hosted three pre-Summit workshops to prepare for the paper and the Summit sessions (). In the first two workshops (21–22 June) presenters shared six case studies (see supplementary material), focusing on the challenges and enablers of TD research for achieving the SDGs in Africa. A template was provided for these presentations, so each covered the theoretical, practice, and institutional challenges and enablers identified in the cases. This facilitated the discussion of the cases in breakout groups and the ready extraction of key learnings later captured in the positioning paper. We also drew on in-depth conversations with expert discussants (African and international) in a third workshop. This workshop focussed on TD scholarship, theory, and praxis and the institutional and funding environments for TD. We invited two speakers linked to international funding organisations to explore the views of funders alongside those of researchers in a panel discussion. Thirty-three participants representing senior academics, early career researchers, research managers and some practitioners and research funders all of whom work in the broad area of sustainability participated. We also gained further insights from the Summit workshops where we explored and imagined the TD space we wanted and suggested specific actions that could be taken to support this vision (see http://www.sdgsafricasummit.uct.ac.za for more information on the Summit; and https://sites.google.com/view/sdgsummit-tt4 for details on Thematic Track 4 on Transdisciplinary and Engaged Research). For these, all the participants (70) were from African institutions.

Figure 1. Summary of the SDG Summit and Berg-Breede catchment multi-actor social learning processes.

The second learning process, which we call the Berg-Breede community of practice ran throughout 2021. It involved a series of seven workshops () aimed at improving our understanding of how best to conduct useful, meaningful, and equitable long-term transdisciplinary research, while engaging in a landscape with multiple competing social-ecological interests, over-pressured resources, and high levels of inequity. There are multiple projects that use TD approaches to address sustainability and equity issues in this catchment, but coordination is poor and impacts fuzzy. The workshop series was, therefore, seen as an opportunity for collective reflection and learning from previous and current landscape-related research, in terms of a) the capacity to implement transdisciplinary research, and b) the ways of working with multiple stakeholders to create lasting partnerships and maximise research uptake and impact. The first three workshops targeted TD researchers from Western Cape academic institutions with research experience in the Berg-Breede catchment. The next two workshops involved practitioners working in the catchment, and the third educators who train sustainability scientists in tertiary institutions. These interactive workshops provided each actor group with a safe space for sharing their experiences with TD research and to surface practical short- and long-term options for addressing identified challenges. Numbers varied across workshops but altogether, some 30 people participated. All groups were brought together in a final workshop to synthesise and validate the knowledge and understanding from the workshop series.

3. Learning insights and outcomes

3.1. Reconfiguring academic institutions to foster TD

Despite TD being promoted for the last 20 years as an approach to undertaking societally relevant research that addresses sustainability, researchers adopting this research practice continue to face multiple hurdles (Care et al. Citation2021). Institutional, epistemological, and methodological barriers of the ‘old academy’ undermine the imperative to change, sometimes despite TD being advocated by university leadership (Pollet and Huyse Citation2019). In this section, we highlight institutional considerations, priorities and enablers identified from our workshops under three main sections and offer suggestions to pave the way forward for successful support of TD research that contributes towards African universities being better equipped to address the SDGs and facilitate transformative change.

3.1.1. Institutional culture: towards a more mutually respectful and caring environment

Working across disciplines is not yet the norm within many academic institutions in Africa, and collaboration with partners outside of academia remains rare. Researchers who are leading the charge in this regard are often stretched to balance their TD aspirations with those of the ‘old academy’ (Pollet and Huyse Citation2019; Fam et al. Citation2020; Risopoulos-Pichler et al. Citation2020). In this context, a challenge mentioned by many participants at our workshops was opposition from disciplinary-focussed colleagues, who buy into the common misconception that TD research lacks rigour, is anecdotal and unscientific, or that a TD framing could become the dominant research paradigm in the university and secure more resources than traditional, discipline-focused approaches. In some cases, it was reported that such scepticism may be backed up within the power hierarchies, for example by heads of departments and deans, who prioritise disciplinary specialisation over interdisciplinary and TD research. As one of our participants noted ‘our institutions tend to be locked in hierarchies and a hegemonic understanding of disciplines and power. For example, rewarding competition and grit in academia and science can discourage vulnerable and open relationships. Finding ways to humanise institutions by breaking down those hierarchies and focusing on relationship building with all its inherent vulnerabilities and biases can help to overcome hurdles in implementing TD’. Furthermore, TD practice is often seen as an ‘add-on’ process for peripheral impact work which is not central to academic research, and that seeking solutions to complex societal and social-ecological problems lies outside the realm of university work. The consensus in our workshops was that many of our academic colleagues are still distrustful of TD in terms of its value, quality and advocacy role. A culture of assumed superiority of theoretical research over applied research is still strong in many academic institutions. This can permeate widely to undermine collaboration, isolate TD researchers, and erode confidence in their chosen approach.

Given this situation, there is an urgent need to promote a culture and ethics of respect, appreciation, collegiality, relationality, and care for TD work at all levels of the institution as well as nurture respect for interdisciplinary and TD research as valid and valuable knowledge production processes (Care et al. Citation2021; Sellberg et al. Citation2021). One of our participants highlighted that: ‘if we want TD to be effective we need to look at the culture of institutions in a deeper way and change that culture’. A culture change to address concerns related to TD could be engendered through better communication around the role and place of TD in the academy. For example, the principles of TD recognise that there is space for multiple forms of knowledge and research within academic institutions (Lawrence et al. Citation2022). This idea of a pluralistic way of undertaking research is exemplified in a statement by Nicolescu (Citation2002, 44–45): ‘Transdisciplinarity is nourished by disciplinarity. In turn, disciplinarity is clarified by transdisciplinary knowledge in a new and fertile way’. In one workshop discussion, it was raised that when we advocate for TD, we must ensure that it does not become exclusionary and hegemonic, falling into the disciplinary trap. As one participant put it: ‘we (TD researchers) seek to enrich not annihilate knowledge’. TD should be seen as a way to ‘empower universities to act as change agents and respond to societal challenges’ more directly than other research approaches (https://www.uu.nl/en/research/transdisciplinary-field-guide) and as complementary to other ways of generating knowledge. Without promotion of engaged scholarship, universities are unlikely to move beyond ‘the well-honed academic habit of studying problems without emphasising solutions’ which ‘is ever more troubling in today’s world’ (Hart et al. Citation2016, p. 2). To move forward, universities need to promote TD work more actively, and in non-threatening ways, through annual sharing forums, news articles and awards: ‘we need case studies from within our universities to demonstrate/illustrate what can be done’; ‘a prize for the best TD research project could raise awareness in the university for this type of research and its possibilities’.

In addition, physical spaces for scholarly exchange, peer-to-peer informal mentoring programmes, training workshops, discussion and learning platforms, summer schools, and co-supervision across disciplines, all mentioned by participants, could build community and confidence among postgraduate students, early career, mid-career, and senior researchers. To improve collaboration and knowledge co-production, cross-institutional ‘communities of practice’ (COPs) or working groups (often called ‘third spaces’) can bring together researchers, practitioners and other communities into learning spaces that are welcoming to all (Cundill et al. Citation2015; see Roux et al. Citation2020 for an example). This range of assemblages can support relationships and ways of working at the intersection of practices and disciplines, which are agile and critical, instead of siloing TD (Hart et al. Citation2016; Hart and Silka Citation2020; Chambers et al. Citation2022).

Mentorship and peer support are highly sought by those currently engaging in TD work; as one participant said: ‘as a young researcher, it’s very important to be in a space where you are comfortable because when you are so overwhelmed it’s easy to pause and seek support … that comfortable space should be created by your seniors’. Most existing forms of academic supervision and line management do not provide the caring support TD requires. We need to mentor scholars through the practical and emotional challenges that result from working with complex, often conflictual problems, multiple perspectives and views, difficult power dynamics, and often high levels of injustice. A quote from one of our participants highlights the ‘need to invest in sustaining the courage, vision, reflexivity and (methodological) agility required to do this work’. To make this type of mentorship effective, we need a set of flexible structures that incentivise, legitimise and reward mentorship for those engaging in TD, including acknowledging the time required to undertake this work. Establishing, growing, and sustaining communities of practice/working groups for those involved in TD across the academy would assist with this. For senior staff in African universities who are burdened with multiple roles and responsibilities, including heavy teaching loads, engaging in TD work requires building well-capacitated teams and support networks. This entails finding new and creative ways to include students in research, curriculum design and teaching to share the burden and at the same time grow their capacity. To support TD, we need more diverse, distributed leadership and co-supervision arrangements (e.g. advisory panels, potentially including people from multiple faculties and beyond the academy) to bring different perspectives, skills, and personalities into the research and mentorship process (Fam et al. Citation2020).

3.1.2. Creating enabling structural and administrative systems

The current structure of most African universities caters primarily for disciplinary focused departments situated within distinctive faculties that tend to operate autonomously with limited interdepartmental and faculty communication (Armitage et al. Citation2019). A cluster of challenges generated by this ‘siloed’ structure, and associated administrative systems, were identified in our workshops, both for individuals and groupings within departments wishing to undertake TD as well as research institutes that work across departments, faculties, and even universities. The most mentioned challenges related to how the current structure promotes competition for resources, creates resistance to collaboration and co-authorship, makes administration complex and slow, heightens power hierarchies, and complicates student registration and examination. For example, faculty specific funding flows and distribution, ethics approval, and thesis styles and timeframes often act as disincentives for collaboration. Other structural and administrative challenges related to TD include intellectual property policies preventing data sharing, funding constraints, ethics requirements that do not cater for emergent TD research and the traditional academic reward system which is discussed further below (section 3.1.3). Regarding current structural inflexibilities, one participant mentioned: ‘we need to transform institutions to be sufficiently dynamic and relational in order to enable research that is not fully protectable; that responds, or has to respond, to conditions that are not controlled, both socially and epistemically by scientists solely’.

Addressing these structural challenges could include clearer roadmaps for TD students related to where to register, thesis requirements, training opportunities, and ethical clearance; ‘we need to change how we support and assess students – there are rigid ideas of what students have to do’. Some workshop participants suggested higher-level structures to coordinate TD work, including a postgraduate school of TD. Others were wary about creating formal structures that separate out TD in its own potentially siloed space and recommended, rather, the informal spaces mentioned in the previous section: “I can see already (and I’m not being critical now, I’m just observing) ‘you’ have started creating a discipline around TD”. Others argued that TD requires new, distributed, collective leadership forms as described by Fam et al. (Citation2020) and Care et al. (Citation2021) which can drive the changes needed. The latter authors mention how they had instituted a ‘Careoperative’ as a living experiment to provide a forum to change the work environment and to offer collegiate support. This model recognises that unblocking deeply embedded systemic challenges in academic structures (Fam et al. Citation2020) needs to happen simultaneously with the cultural transformations mentioned in the previous section to have the desired impact (Sellberg et al. Citation2021). Hart et al. (Citation2016), drawing together experiences from six United States of America academic institutions with transdisciplinary sustainability science initiatives, provide evidence that some academic institutions are slowly learning how to support more collaborative work, and while difficult, it is possible with patience and well-targeted resources and support. There are a growing number of initiatives to learn from.

3.1.3. Recognition, promotion, and career development

The longer timelines required for impactful TD, including the extended time needed before peer-review publications can be produced, are generally not fully appreciated within universities. As a result, TD research is often poorly rewarded and incentivised. This can deter early career researchers from pursuing TD approaches and impede career progression of established researchers who practise deep TD. Changes to promotion criteria should, at the very least, include more comprehensive, qualitative and fewer data-dependent measures in alignment with the Leiden Manifesto (www.leiden manifesto.org) and the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA, https://sfdora.org/). One of our participants commented that ‘we need more creative approaches to assessment that consider levels of engagement and collaboration’. Co-development of more holistic assessment indicators that capture both scholarly outputs and levels of inclusivity in research, deep societal engagement, transformative impacts, popular knowledge products and the new type of leadership critical for effective TD research could provide a way forward (Keeler and Locke Citation2022). In the words of one of our participants ‘TD research has to be evaluated differently from disciplinary research, and the onus is now on us … . to begin to develop an evaluation rubric that takes account of process (as an important step for the quality of TD)… we need to start developing indicators that integrate elements of social, economic, and ecological’. Teamwork and multi-authored papers, book chapters and books need to be valued as much as single-authored papers. Non-academic knowledge outputs (e.g. films, videos, co-written policy or business briefs, manuals, news articles, reports, comics and animations) also need more recognition, including greater interaction with the arts as a means of including a diversity of perspectives (Steelman et al. Citation2019). Greater appreciation of the risk-taking, creative thinking and tenacity attributes of TD researchers that are so important in creating the spaces and approaches that can reshape universities to meet sustainability demands is needed (Hart et al. Citation2016). Moreover, we saw a strongly gendered and career stage bias in TD work, with women and early to mid-career researchers often promoting and holding the TD space (also reflected in the authorship of this paper), along with the additional responsibilities and emotional burdens such work brings. Reorienting what is recognised and awarded as excellence in universities could help in acknowledging this important pioneering role and the extra work and dedication required to build collaboration across disciplines and with societal actors. While there is some progress towards this – e.g. several of the African participants’ universities recognise the DORA principles – rollout is slow, and the necessary widening of the criteria for promotion is still distant. Implementing university-level systems that support TD are thus urgently needed to incentivise established researchers, keep early career researchers in the academic realm, and create the conditions for thought-leadership on complex sustainability problems (Keeler and Locke Citation2022).

3.2. Funding TD for sustaining knowledge co-production partnerships

One of the most frequently expressed challenges raised in both learning processes was the need for appropriate and longer-term funding to facilitate TD research that builds the trusting relationships needed to effect transformative change. Funding, both in terms of limited amounts and the short duration of many funding cycles, continues to be a limitation that can stifle the kind of iterative, responsive research required to achieve the SDGs. ‘You get three years funding to work on a specific area but if you work with communities, there are a lot of things involved – it’s difficult to do everything in the time available’. Sufficient and sustained resource flows in terms of financing, and human capital, is critical for the slow process of TD research (OECD Citation2020). However, many current resourcing mechanisms remain untransformed (Decade of Global Sustainability Science Action (2020–2030)). This is, in part, because researchers and practitioners, especially from the Global South, are seldom engaged in the conceptualisation of high-level funding strategies, and so the realities of this type of work are not always fully appreciated. One of the primary outputs from the Berg-Breede learning process was a policy brief directed at funders that outlines researcher and practitioner concerns and the options that can engender the systems-level change needed (https://sites.google.com/view/berg-breede/project-resources).

Transforming funding models to better support TD requires action at multiple levels. International, national, and university funding mechanisms need to reconfigure how funding is structured; who determines the scope of the funding calls and the length of the funding period; who is involved in funding applications; and how researchers and their institutions (e.g. grants offices) are supported within and across institutions and communities of practice. Funders interested in supporting TD should work together to devise integrated mechanisms for supporting transformative research, such as blended funding approaches, partnerships between research and development funders, and dialogues with academic institutions to find ways to resource the changes needed. Adequate resources also are needed to capture and make visible the value and impacts of projects for local partners and national or international efforts like the SDGs, well beyond the scope and lifespan of a project. This involves allocating resources for regular and strategic communication, capacity building, reflection and horizon scanning for all participants and key knowledge users.

3.2.1. Towards flexible, reflexive, and sustained funding for TD

Flexibility of funding models, as well as institutional flexibility to administer projects, are critical in terms of enabling project co-design and co-implementation (Lawrence et al. Citation2022). Workshop participants highlighted how crucial flexibility is. For example one mentioned that ‘funders demand a lot of certainty, which if you work with complex problem situations you can’t always give them’ while another said ‘the funder determines the trajectory of particular research areas … And in so doing, there are normally project-tight guidelines which eventually leaves very little room, not only into spaces where you can learn about work which has been done before and which is ongoing, but also kind of limits your ability to collaborate’. Locking project teams into log frames and timelines prevents them from building trust and effectively co-designing strategies for transformative outcomes. Extending inception phases can provide project partners with adequate space and time to consult with each other, and develop deeper relationships. A slower start also provides the opportunity to understand end-user needs more fully, develop shared visions and objectives, and refine project activities, outcomes, and evaluation techniques. Given that much TD work for the SDGs in Africa takes place in soft-funded institutes, which operate differently to departments, funders need to consider different modes of funding that are flexible enough to accommodate context-specific institutional needs (e.g. funding mechanisms that can assist with supporting core institutional costs and salaries to build continuity between projects).

Funders that a) support reflexivity and flexibility through the co-design of their funding arrangements (e.g. through the constructive use of Theory of Change methodologies (Global Environment Facility Citation2019)); b) give room for experimentation, learning and adaptation; and c) recognise non-academic partners as project investigators were noted as being key enablers of TD. Some funders specifically look for ‘coalitions of actors’ in project proposals and grant flexibility in the redistribution of budget between categories while the project is running. Developing and iteratively revisiting a Theory of Change can help articulate a shared framing and set of objectives, manage expectations, and help guide and evaluate the work. This requires resources to bring project team members together face-to-face for both formal and informal interactions.

Within the university, a key bureaucratic hurdle once funding is secured is the structure of faculty financing which can make the transfer of finance across faculties problematic. Cross-faculty research required university-wide financial and administrative support. However, university-level research funding offices tend to view national research funding as the only funding instrument that requires their support. Other financial hurdles include difficulties with paying non-academic actors and for events in community contexts. More flexibility is needed in payment systems and in the turnaround time for paying local participants, and external entities need to be better recognised as legitimate service providers, though for example, establishing Memorandums of Understanding. In soft-funded research entities, investment in salaries and bridging funding can improve the ability of TD researchers to co-design, implement, evaluate, and improve research; build sustainable and trusting relationships with key actors; and promote impactful outcomes. Salaried positions also enable soft-funded researchers to invest more time in developing robust project pre-proposals, to bring their knowledge and expertise to a wider range of projects (including minimally funded projects), and to inform and support changes to policy and practice within their institutions and externally. The importance of moving beyond short-term contracts to more sustained ways to support TD work has also been highlighted by Fam et al. (Citation2020).

In addition to working with funders, TD researchers need to be strategic about co-funding and pooling resources between different partners and projects. Working collectively to crowd in resources to sustain the work beyond the initial funding can help to ensure continuity in places and partnerships. This requires time for project staff to wrap up effectively when the funding ends, while sowing the seeds for future collaborative work. Often projects have little funding and space for a considered wind-down, even though this is essential.

Funding that spans long-term (>3 years) time horizons helps solidify TD partnerships; improves the depth of project information; enables project findings to be properly synthesised, communicated, and acted on; and bridges gaps between shorter projects (OECD Citation2020; Biggs et al. Citation2022; Lawrence et al. Citation2022). Longer-term so-called ‘Research Chairs’ with salary, postgraduate and project funding provide an encouraging funding model for TD, for example, the South African Research Chairs Initiative and the international AXA Research Chairs. These Chairs (which can be extended up to 15 years) have made it possible for Chair-holders to sustain TD research, often place-based, over the time spans required to build trust and effect impact. Longer-term funding should also apply to fellowships that, if extended to be between 3–5 years, can incentivise early-career researchers to engage in this kind of research

3.2.2. Promoting equitable distribution of funding

In the Berg-Breede learning process, particularly, the issue of equitable distribution of research funding was raised both by researchers who had been part of large international projects and by practitioners who often felt ‘used’ without compensation in TD research processes. To overcome such inequities in funding agendas and remuneration processes, all voices need to be adequately represented in funding discussions, particularly those most embedded in local contexts. Creating equivalent pay scales and project co-leadership across Global North-South divides can counter narratives that researchers in the Global South need capacities built, enhance southern intellectual leadership, and reduce ‘helicopter research’ (Haelewaters et al. Citation2021).

3.2.3. Financing bridging roles

Workshop participants spoke about the crucial enabling role of intermediaries or brokers working to bridge divides between multiple actors, the academy and civil society organisations; within and across soft-funded research entities; and between researchers from different disciplines. Such brokers operating at the research-policy-practice interface are not consistently recognised as playing legitimate roles in projects. Universities and funders should consider financing formal and informal knowledge brokers to serve as central contact points for TD researchers within and beyond universities and practitioner groups (Roux et al. Citation2017; Biggs et al. Citation2022). These brokers serve vital functions as they connect researchers for new projects, support engaged scholarship, capture and act on researcher feedback, and provide administrative support for TD projects.

3.3. Strengthening TD practice for transformative change towards achieving the SDGs

In practice, TD is about impacting and facilitating change through knowledge co-development that is inclusive, authentic, and empowering (Schneider et al. Citation2019; Manuel-Navarrete et al. Citation2021). This is more difficult than it sounds and generally requires working with the messiness and diversity of reality and often with irresolvable complexity, uncertainty and dissensus (Montuori Citation2013; Rogers et al. Citation2013). It is thus necessary to ‘foreground the “who and why” of the TD research before diving into the what and the how’. Researchers and partners need to find a common focus, concepts and theories, terminology and language that brings together different knowledge streams and perspectives (e.g. practical, Indigenous, scientific, African philosophy). One of our participants explained ‘unless we find different vocabularies to begin to make sense of our own experiences, we are actually reproducing the same thing we are actually trying to critique … ’. The fundamentals of how we frame and theorise TD in the African context thus impact the ability of this approach to help facilitate the implementation of the SDGs. We discussed these issues in our workshops and hosted a panel discussion during the final workshop of the SDG Summit learning process on what it means to do TD research in Africa, bringing in ideas of decolonisation and African philosophy. Below, we discuss four broad categories of praxis considerations from our workshops.

3.3.1. Context specificity and recognising multiple knowledge and value systems

A hallmark of TD research is that it is context-sensitive and responsive to grounded and lived realities (de Vos et al. Citation2019). Part of this context sensitivity is that TD involves recognising, valuing, and drawing from embodied knowledge systems, including indigenous knowledge systems. When engaging in TD for sustainability in Africa, workshop participants emphasised that it is important to understand the cultural context and historical injustices perpetuating the inequalities experienced today. Research collaborations therefore need to build on and respect existing knowledge frameworks and processes while being mindful that the legacy of past power structures may have influenced how research is framed and positioned (i.e. the research may have been framed for rather than by or with non-academic actors). TD foregrounds the notion of epistemic parity (Heath and Mormina Citation2022), i.e. the fair and equitable consideration of African- and Western-derived ways of knowing in co-designing research, selecting methods of enquiry, tools, and analytical frames (Konadu-Osei et al. Citation2022). Thus, instead of relying only on, or adapting methods based in western science, TD researchers should consider context-congruent philosophies rooted in Africa to guide their thinking about lines and methods of inquiry, critique their epistemological assumptions and advance theoretical developments from the Global South (Nabudere Citation2012; Chillisa Citation2017; Konadu-Osei et al. Citation2022). One of our participants remarked ‘studying in Africa should contribute to humanity’s thinking’.

That said, the underlying assumptions that frame one’s understanding of Africa – the language and methodology used – are important to unpack before undertaking TD research. A key message from our workshops was that research in and on Africa is often based on a conceptualisation of Africa that originates from the Global North and hinders the continent from taking up a central role in global scholarship. There is a need to increase and improve engagement with history, identity politics, gender sensitivities, ethics, patriarchal, or other power dynamics, and explore and potentially shift the various motivations and incentives for participating in knowledge co-production work. ‘What we want to do is have Africa contribute to thinking in the world, not just be a place where ideas and concepts from the Global North are implemented. In order to do that, we need to adopt a pluriversal approach which allows us to theorise through Africa instead of theorising only for Africa’. Since TD research necessarily involves actors outside of academia, a reflexive TD researcher should seek to understand better the ontologies (what is reality, ways of being) of the research context (Wolff et al. Citation2019). Recognising the need for transforming how we think about knowledge and research in non-western contexts, one of our participants highlighted that ‘what really makes quality transdisciplinary work is transformative knowledge that leads to transformative action’.

3.3.2. Scaling from local to global and global to local

As mentioned above, TD research is essentially place-based and context cognisant (Daudin et al. Citation2021). However, workshop participants emphasised that to progress the SDGs and transformation, it is essential to take the findings to a larger scale and into the higher-level scientific, policy and financing agenda, but that this can be difficult: ‘I think that’s the one point I’m getting very strongly, is the difficulty when it’s framed at one scale, but is of relevance to another, but that relevance is hard to translate’. Programmes that foster TD can embed or link to people or institutions across the region, nationally and internationally to translate the learnings rooted in local contexts into the global agenda. We need to address issues of scaling and application to draw more global or generally applicable lessons from studies that are – necessarily and appropriately – place-based and embedded in a local context (Riddell and Moore Citation2015; Odume et al. Citation2021; Thiam et al. Citation2021).

In the same vein, translating knowledge and understanding of complex social-ecological systems into concrete recommendations and policy applications remains challenging. TD is focused on wicked problems and grand challenges and is required to contribute solutions (Knapp et al. Citation2019). This can bring to the fore issues of power relations regarding who gets to make recommendations and who can and should apply them (Marshall et al. Citation2018). Again, communities of practice might derive focus and momentum from engagement with local, national, and international priorities through nested learning and governance networks (Cundill et al. Citation2015; Vincent et al. Citation2018). The SDGs are a prime example of priorities that allow engagement at various scales, from local communities to global concerns.

3.3.3. Common framing, language, and authenticity by focusing on mutually identified concerns

There is a need to be deliberate in how we approach our research practice – this is especially necessary when considering how to close the ‘academic-practitioner’ gap (Knapp et al. Citation2019). For TD researchers and participants from multiple backgrounds to work together effectively, conceptual frameworks that cut across disciplinary silos can facilitate integration (Schneider et al. Citation2019). Authenticity and honesty are critical in TD research. These can only be achieved when all actors find a shared language and common set of concepts that they all care about and understand, and when the meaning of certain commonly used terms or words is carefully questioned. This is far from trivial as highlighted by one participant: ‘we need to question the origin of the language we use when we think about TD’. Different disciplines use specific terminology or underlying theoretical or conceptual frameworks, which may be impenetrable to non-specialists. Such challenges are exacerbated when working with actors from outside academia, who may use narratives, descriptions and concepts embedded within local cultures. When working with actors who may not be familiar with academic concepts, the use of boundary objects (e.g. frameworks, concepts, models, field notes, dramas, songs, and maps) can help focus attention, centre cooperation, and enable mutual learning, communication and negotiation across groups (Star and Griesemer Citation1989; Lundgren Citation2021; Steger et al. Citation2022).

Many researchers feel poorly equipped to navigate the complex, often hidden power dynamics that characterise multi-actor spaces (Knapp et al. Citation2019). These power relations often dominate the problem-framing process and prioritising activities and outputs. Creating novel and safe spaces for collaboration with external actors is critical to fostering TD work. Embedding these spaces in the context of the addressed problems is particularly productive (e.g. examples shared included creating a floating workshop to discuss issues related to joint water security or holding ‘workshops’ that involve walking through landscapes to see challenges first-hand). The use of creative, imaginative, and engaging methods (e.g. theatre, drawing, acting, participatory mapping or murals) helps to create a sense of openness and safety to share or raise contentious issues or imaginaries (Brown et al. Citation2017; Galafassi et al. Citation2018; Pereira et al. Citation2019; Thorn et al. Citation2020). Art-based methods and games (e.g. musical theatre, animations, dance, and exploring soundscapes) remain essential communication tools that can prompt transformational change. Some examples that were shared included the use of theatre and soundscapes: we partnered with an NPO who developed the stories [from fishers] into a musical theatre production that was done with the community and discussed; one facilitator who was very energetic did this amazing rain soundscape after which she went on to ask ‘what does it mean to you’ of each individual. And how amazing it was that we had such varied responses”. Such methods have been shown to help work through linguistic and cultural differences and conceptual or discursive barriers (Steelman et al. Citation2019; Ball et al. Citation2021).

3.3.4. Inclusiveness, creativity, and reflexivity

TD processes need to be inclusive. It is important to cultivate long-term collaborative partnerships across various organisational levels and spatial scales (Prell et al. Citation2021). Having a set of pre-existing relationships helps to ‘hit the ground running’ and to bring in additional collaborators as the project evolves. Enrolling and supporting a range of influential champions (e.g. traditional leaders, teachers, and city councillors) in the TD process is thus an important enabler. It will assist to cope with the turnover of staff and leaders which can cause difficulties and discontinuities. Open and frequent communication is key to building and the sustaining momentum needed to keep partners engaged.

An essential feature of collaborative research is that openness to new knowledge and reflexivity is built into the research process (Knaggård et al. Citation2018). This facilitates adaptation in the research agenda and process in response to emerging knowledge, new perspectives, and changing environmental and social conditions (de Vos et al. Citation2021). Such agility requires long timeframes that allow the relationships underpinning scholarly research to develop and for research trajectories to iterate and adapt. It also requires a fluidity of roles, especially considering the need for methodological agility and diversity of skills and techniques (Knaggård et al. Citation2018; de Vos et al. Citation2021). Different people and partners will be engaged and involved to varying depths throughout the collaboration (Prell et al. Citation2021). There is, thus, a need to constantly adapt terms and concepts, objectives (for the project) and methodologies in an ever-changing project landscape, as one participant summed up: ‘we need to take the onus of being more creative’ in all stages of a project. In collaborative adaptive management, for example, multi-actor groups (e.g. scientists, managers, and communities) engage in multiple cycles of problem framing, interventions, learning and adaptation (Jack et al. Citation2020). The funding constraints to achieving such inclusiveness have been highlighted in the previous section.

4. Conclusion

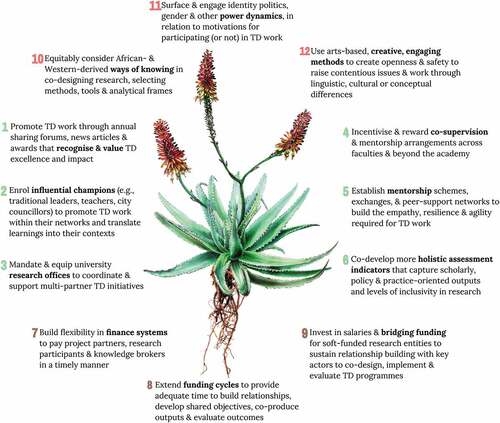

To realise the ambitions of the SDGs and associated transformative change, new research and learning approaches are required that can address complex sustainability challenges at different scales and link to policy and action (McGowan et al. Citation2019). Our work with multiple actors prior to and at the SDG Summit and in the Berg-Breede catchment helped us imagine the ‘TD space we want’ and brought us closer to possible pathways by which change can be enacted. We have synthesised and condensed our learnings according to our three thematic areas, namely a) promote and support TD within academic institutions, b) resource TD for sustainable partnerships and, c) improve practices and impacts to support the transformation, into 12 recommendations which we discuss below (; Appendix 3 in the supplementary materials).

Figure 2. Twelve recommendations emerging from our learning processes for creating the ‘TD space we want’. Numbers 1–6 in the green font represent recommendations related to “Reconfiguring academic institutions to foster TD” (which we visualise as the core or stem of the aloe); numbers 7–9 in brown font represent recommendations related to “Funding TD for sustaining knowledge co-production partnerships” (which we visualise as the aloe roots which feed the plant); and numbers 10–12 in red font relate to ways to strengthen TD practice for transformative (the flowers of the aloe).

To foster TD in African academic institutions, innovative structures and processes are needed to address the required institutional and cultural change. A new culture of care, relationality, respect, mentorship and distributed leadership will provide the environment for boundary pushing research, collaboration and reflexivity, and embed project co-design and knowledge co-production. This means equipping university research offices to champion a range of TD initiatives including, for example, cross-faculty communities of practice, sharing and awareness raising events, and proposal development as well as drive the structural changes needed to support TD research (e.g. in financial systems, ethics procedures). More creative assessment of researchers and innovative, collaborative supervision and mentorship will help grow TD research and capacity, while investment is required in training the next generation of TD researchers who can engage in advocacy and relationship building to drive the changes needed. Universities also need to reach beyond the academy to guide their research agenda and partner with influential champions who can also promote collaborative partnerships and research in their own spaces: ‘I think it’s a fundamentally critical thing that we have societal partners working with us at the outset because they’re heard differently in the university space than how we are heard’. These changes are core to progressing transformative TD work, and so we have positioned them at the heart of the aloe in (lessons 1–6).

Innovative TD work cannot happen without the underpinning resources that universities and funding agencies need to provide if they are serious about promoting relational knowledge building and contributing to sustainable development and transformative change (, lessons 7–9). This means modifying current funding processes and structures to a) support the required institutional change and capacity development; b) enable meaningful engagement with non-academic actors and their concerns in an on-going way through longer-term funding and resourcing knowledge brokers; c) create the flexibility and time in projects to pursue new directions as they emerge as well as co-develop actions that are pluralistic, negotiated, equitable and practical; and d) allocate finances to provide greater continuity for researchers in soft-funded institutes who are often leading this work. To achieve this requires more engagement and dialogue between funders, academic leadership, researchers, community champions and practitioners. There is a need to move beyond the situation in which ‘the funder says “here’s what we can fund” and every year or whatever they say “fill in this evaluation form or report in this template”’ towards ‘a two-way street built on trust and agility’.

The complex and reflexive nature of TD means that researchers and collaborators should be constantly reflecting on how they can improve their practice. Critical areas emerging from our learning processes are presented in (lessons 10–12). TD not only presents an opportunity to work beyond the academy, it is also an important entry point for decolonising research, policies and practice by including African philosophies, worldviews, and ways of knowing; an area that was recognised as requiring further research and theorising. Epistemic pluralism and methodological agility need to be a part of research practice to support collaborative work within and between diverse contexts and actors. This requires building relationships within the TD space – with knowledge-holders and users, communities, and policy makers – through networks and innovative third spaces that are accessible and non-threatening and that allow for expression of different actors’ perspectives, knowledge systems, needs, and interests. Such safe spaces also provide the opportunity to work through identity politics, gender issues and power dynamics all of which can act as hindrances to transformative change. An important message from our workshops was that these spaces and issues can be opened up further through the use of generative arts-based methods that create a sense of safety and depersonalisation to raise contentious issues and work through linguistic, cultural or conceptual differences.

Together the above themes will be increasingly critical for African researchers, funders, policy makers, society, practitioners, and other actors to reflect on and action in order to progress transformative solutions to emerging sustainability challenges across the African continent in years to come. As articulated by one of our participants ‘together, we need to build solidarity and connectivity to disrupt, and we need to be bold. The moment is now to be bold’.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (661.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants in the two social learning processes whose time and input led to rich and engaging discussions and informed the body of insights provided in this positioning paper. For the SDG Summit pre-workshops we were fortunate to field contributions from a wide range of perspectives, including academics, practitioners, funders, and government, spanning nine countries across Africa, North America, and Europe. We would like to give special thanks to our case study presenters and discussants, who provided additional time and input to share their wealth of knowledge and experience. Thanks also to our excellent facilitator, Lucy O’Keeffe. We acknowledge the research office of University of Cape Town for support. Similarly, we would like to thank all the participants who attended the series of Berg-Breede workshops over 2021. Special thanks to Tali Hoffman for transforming the learning insights into information briefs targeted at Funders as well as Researchers & Practitioners. The Berg-Breede workshops were funded through an NRF (National Research Foundation of South Africa) Community of Practice partnership for advancing transformative social learning and transdisciplinary sustainable development actions hosted by the Environmental Learning Research Centre at Rhodes University. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent those of the NRF. The lists in Appendix 2 provide the names of workshop contributors separated by social learning processes.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2022.2164798

Disclosure statement

Nadia Sitas is an Editorial Board Member for Ecosystems and People but was blinded from the peer-review process for this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguiar APD, Collste D, Harmáčková ZV, Pereira L, Selomane O, Galafassi D, Van Vuuren D, Van Der Leeuw S. 2020. Co-designing global target-seeking scenarios: a cross-scale participatory process for capturing multiple perspectives on pathways to sustainability. Global Environ Change. 65:102198. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102198.

- Armitage D, Arends J, Barlow NL, Closs A, Cloutis GA, Cowley M, Davis C, Dunlop SD, Ganowski S, Hings C, et al. 2019. Applying a “theory of change” process to facilitate transdisciplinary sustainability education. Ecol Soc. 24(3): doi:10.5751/ES-11121-240320.

- Armstrong McKay DI, Staal A, Abrams JF, Winkelmann R, Sakschewski B, Loriani S, Fetzer I, Cornell SE, Rockström J, Lenton TM. 2022. Exceeding 1.5° C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science. 377(6611):7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950.

- Ball S, Leach B, Bousfield J, Smith P, Marjanovic S. 2021. Arts-based approaches to public engagement with research. Lessons from a rapid review. Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK: THIS Institute and RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA194-1.html

- Barnosky AD, Brown JH, Daily GC, Dirzo R, Ehrlich AH, Ehrlich PR, Eronen JT, Fortelius M, Hadly EA, Leopold EB, et al. 2014. Introducing the scientific consensus on maintaining humanity’s life support systems in the 21st century: information for policy makers. Anthropocene Rev. 1(1):78–16. doi:10.1177/2053019613516290.

- Bergmann M, Jahn T, Knobloch T, Krohn W, Pohl C, Schramm E. 2012. Methods for transdisciplinary research: a primer for practice. Frankfurt, Germany: Campus Verlag GmbH.

- Beyond the Academy. 2022. Guidebook for the Engaged University: best Practices for Reforming Systems of Reward, Fostering Engaged Leadership, and Promoting ActionOriented Scholarship Keeler BL, Locke C, editors. http://beyondtheacademynetwork.org/guidebook/.

- Biggs R, Clements HS, Cumming GS, Cundill G, de Vos A, Hamann M, Luvuno L, Roux DJ, Selomane O, Blanchard R, et al. 2022. Social-ecological change: insights from the Southern African program on ecosystem change and society. Ecosyst People. 18(1):447–468. doi:10.1080/26395916.2022.2097478.

- Brown K, Eernstman N, Huke AR, Reding N. 2017. The drama of resilience: learning, doing, and sharing for sustainability. Ecol Soc. 22(2):8. doi:10.5751/ES-09145-220208.

- Care O, Bernstein MJ, Chapman M, Diaz Reviriego I, Dressler G, Felipe-Lucia MR, Friis C, Graham S, Hänke H, Haider LJ, et al. 2021. Creating leadership collectives for sustainability transformations. Sustainability Sci. 16:703–708. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00909-y.

- Chambers JM, Wyborn C, Klenk NL, Ryan M, Serban A, Bennett NJ, Brennan R, Charli-Joseph L, Fernández-Giménez ME, Galvin KA, et al. 2022. Co-productive agility and four collaborative pathways to sustainability transformations. Global Environ Change. 72:102422. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102422.

- Chillisa B. 2017. Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: an African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustainability Sci. 12:813–827. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0461-1.

- Cundill G, Roux DJ, Parker JN. 2015. Nurturing communities of practice for transdisciplinary research. Ecol Soc. 20(2):22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26270207.

- Darbellay F. 2015. Rethinking inter-and transdisciplinarity: undisciplined knowledge and the emergence of a new thought style. Futures. 65:163–174. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2014.10.009.

- Daudin K, Weber C, Colin F, Cernesson F, Maurel P, Derolez V. 2021. The collaborative process in environmental projects, a place-based coevolution perspective. Sustainability. 13(15):8526. doi:10.3390/su13158526.

- de Vos A, Biggs R, Preiser R. 2019. Methods for understanding social-ecological systems: a review of place-based studies. Ecol Soc. 24(4): doi:10.5751/ES-11236-240416.

- de Vos A, Maciejewski K, Bodin Ö, Norström A, Schlüter M, Tengö M. 2021. The practice and design of social-ecological systems research. In: Biggs R, De Vos A, Preiser R, Clements H, Maciejewski K, and Schlüter M, editors. The Routledge handbook of research methods for social-ecological systems. London: Taylor & Francis; p. 526.

- Fam D, Clarke E, Freeth R, Derwort P, Klaniecki K, Kater‐wettstädt L, Juarez‐bourke S, Hilser S, Peukert D, Meyer E, et al. 2020. Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research and practice: balancing expectations of the ‘old’ academy with the future model of universities as ‘problem solvers’. High Educ Q. 74(1):19–34. doi:10.1111/hequ.12225.

- Fam D, Neuhauser L, Gibbs P, editors. 2018. Transdisciplinary theory, practice and education: the art of collaborative research and collective learning. Springer Cham. doi:10/1007/978-3-319-93743-4

- Folke C, Polasky S, Rockström J, Galaz V, Westley F, Lamont M, Scheffer M, Österblom H, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, et al. 2021. Our future in the anthropocene biosphere. Ambio. 50:834–869. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01544-8.

- Future Earth. 2020. Our future on earth 2020. Future Earth. https://futureearth.org/publications/our-future-on-earth/.

- Galafassi D, Kagan S, Milkoreit M, Heras M, Bilodeau C, Bourke SJ, Merrie A, Guerrero L, Pétursdóttir G, Tàbara JD. 2018. ‘Raising the temperature’: the arts on a warming planet. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 31:71–79. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.010.

- Global Environment Facility. 2019. Theory of Change Primer (GEF/STAP/C.57/inf.04). GEF Council Meeting, Washington, D.C., USA. https://www.thegef.org/council-meeting-documents/theory-change-primer

- Griggs D, Stafford-Smith M, Gaffney O, Rockström J, Öhman MC, Shyamsundar P, Steffen W, Glaser G, Kanie N, Noble I. 2013. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature. 495(7441):305–307. doi:10.1038/495305a.

- Griggs D, Stafford-Smith M, Rockström J, Öhman MC, Gaffney O, Glaser G, Kanie N, Noble I, Steffen W, Shyamsundar P. 2014. An integrated framework for sustainable development goals. Ecol Soc. 19(4):49. doi:10.5751/ES-07082-190449.

- Hadorn GH, Bradley D, Pohl C, Rist S, Wiesmann U. 2006. Implications of transdisciplinarity for sustainability research. Ecol econ. 60(1):119–128. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.12.002.

- Haelewaters D, Hofmann TA, Romero-Olivares AL, Schwartz R. 2021. Ten Simple rules for Global North researchers to stop perpetuating helicopter research in the Global South. PLoS Comput Biol. 17(8):e1009277. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009277.

- Hart DD, Buizer JL, Foley JA, Gilbert LE, Graumlich LJ, Kapuscinski AR, Kramer JG, Palmer MA, Peart DR, Silka L, et al. 2016. Mobilizing the power of higher education to tackle the grand challenge of sustainability: lessons from novel initiatives. Elementa. 2016:000090. doi:10.12952/journal.elementa.000090.

- Hart DD, Silka L. 2020. Rebuilding the ivory tower: a bottom-up experiment in aligning research with societal needs. The University of Maine, DigitalCommons@UMaine. hrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1118&context=mitchellcenter_pubs.

- Heath C, Mormina M. 2022. Moving from collaboration to co-production in international research. Eur J Dev Res. 1–12. doi:10.1057/s41287-022-00552-y.

- IPBES. 2019. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In: Brondízio ES, Settele J, Díaz S, Ngo HT, editors. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat; p. 1148. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3831673.

- Jack CD, Jones R, Burgin L, Daron J. 2020. Climate risk narratives: an iterative reflective process for co-producing and integrating climate knowledge. Clim Risk Manage. 29:100239. doi:10.1016/j.crm.2020.100239.

- Juju D, Baffoe G, Lam RD, Karanja A, Naidoo M, Ahmed A, Jarzebski MP, Saito O, Fukushi K, Takeuchi K, et al. 2020. Sustainability challenges in sub-Saharan Africa in the context of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). In: Gasparatos A, Ahmed A, Naidoo M, Karanja A, Fukushi K, Saito O, Takeuchi K, editors. Sustainability challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa I. Springer; pp. 3–50. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-4458-3_1.

- Kinzig AP. 2001. Bridging disciplinary divides to address environmental and intellectual challenges. Ecosystems. 4(8):709–715. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0039-7.

- Klein JT. 2013. The transdisciplinary moment(um). Integr Rev. 9(2):189–199.

- Knaggård Å, Ness B, Harnesk D. 2018. Finding an academic space: reflexivity among sustainability researchers. Ecol Soc. 23(4): doi:10.5751/ES-10505-230420.

- Knapp CN, Reid RS, Fernández-Giménez ME, Klein JA, Galvin KA. 2019. Placing transdisciplinarity in context: a review of approaches to connect scholars, society and action. Sustainability. 11(18):4899. doi:10.3390/su11184899.

- Konadu-Osei OA, Boroş S, Bosch A. 2022. Methodological decolonisation and local epistemologies in business ethics research. J Bus Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-022-05220-z.

- Lawler OK, Allan HL, Baxter PW, Castagnino R, Tor MC, Dann LE, Hungerford J, Karmacharya D, Lloyd TJ, López-Jara MJ, et al. 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic is intricately linked to biodiversity loss and ecosystem health. Lancet Planet Health. 5(11):e840–850. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00258-8.

- Lawrence MG, Williams S, Nanz P, Renn O. 2022. Characteristics, potentials, and challenges of transdisciplinary research. One Earth. 5(1):44–61. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2021.12.010.

- Lenton TM, Rockström J, Gaffney O, Rahmstorf S, Richardson K, Steffen W, Schellnhuber HJ. 2019. Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. Nature. 575(7784):592–595. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0.

- Liu J, Mooney H, Hull V, Davis SJ, Gaskell J, Hertel T, Lubchenco J, Seto KC, Gleick P, Kremen C, et al. 2015. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science. 347(6225):1258832. doi:10.1126/science.1258832.

- Lotz-Sisitka H, Wals AE, Kronlid D, McGarry D. 2015. Transformative, transgressive social learning: rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 16:73–80. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.018.

- Lundgren J. 2021. The grand concepts of environmental studies boundary objects between disciplines and policymakers. J Environ Stud Sci. 11(1):93–100. doi:10.1007/s13412-020-00585-x.

- Lutz JS, Neis B, editors. 2008. Making and moving knowledge: interdisciplinary and community-based research for a world on the edge. Québec, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Manuel-Navarrete D, Buzinde C, Swanson T. 2021. Fostering horizontal knowledge co-production with indigenous people by leveraging researchers’ transdisciplinary intentions. Ecol Soc. 26(2): doi:10.5751/ES-12265-260222.

- Marshall F, Dolley J, Priya R. 2018. Transdisciplinary research as transformative space making for sustainability. Ecol Soc. 23(3): doi:10.5751/ES-10249-230308.

- McGowan PJ, Stewart GB, Long G, Grainger MJ. 2019. An imperfect vision of indivisibility in the sustainable development goals. Nat Sustainability. 2(1):43–45. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0190-1.

- Montuori A. 2013. Complexity and transdisciplinarity: reflections on theory and practice. World Futures. 69(4–6):200–230. doi:10.1080/02604027.2013.803349.

- Nabudere DW. 2012. Afrikology and transdisciplinarity: a restorative epistemology. Pretoria, South Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa.

- Nicolescu B. 2002. Manifesto of transdisciplinarity. Albany, USA: State University of New York Press.

- Odume ON, Amaka-Otchere ABK, Onyima BN, Aziz F, Kushitor B, Thiam S. 2021. Pathways, contextual and cross-scale dynamics of science-policy-society interactions in transdisciplinary research in African cities. Environ Sci Policy. 125:116–125. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2021.08.014.

- OECD. 2020. Addressing societal challenges using transdisciplinary research. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Paper, 88. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/0ca0ca45-en.

- Pereira L, Sitas N, Ravera F, Jimenez-Aceituno A, Merrie A, Kapuscinski AR, Locke KA, Moore M-L. 2019. Building capacities for transformative change towards sustainability: imagination in intergovernmental science-policy scenario processes. Elementa. 7:35. doi:10.1525/elementa.374.

- Pollet I, Huyse H. 2019. Universities and global challenges: redesigning university development cooperation in the SDG era. Leuven, Belgium: KU Leuven and HIVA Research Institute for Work and Society. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/2957662?limo=0.

- Popa F, Guillermin M, Dedeurwaerdere T. 2015. A pragmatist approach to transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: from complex systems theory to reflexive science. Futures. 65:45–56. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2014.02.002.

- Prell C, Hesed CDM, Johnson K, Paolisso M, Teodoro JD, Van Dolah E. 2021. Transdisciplinarity and shifting network boundaries: the challenges of studying an evolving stakeholder network in participatory settings. Field Methods. 33(4):405–416. doi:10.1177/1525822X20983984.

- Riddell D, Moore ML. 2015. Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: advancing systemic social innovation and the learning processes to support it. Technical Report in the Journal of Corporate Citizenship.

- Risopoulos-Pichler F, Daghofer F, Steiner G. 2020. Competences for solving complex problems: a cross-sectional survey on higher education for sustainability learning and transdisciplinarity. Sustainability. 12(15):6016. doi:10.3390/su12156016.

- Rockström J, Gupta J, Lenton TM, Qin D, Lade SJ, Abrams JF, Jacobson L, Rocha JC, Zimm C, Bai X, et al. 2021. Identifying a safe and just corridor for people and the planet. Earth’s Future. 9(4):e2020EF001866. doi:10.1029/2020EF001866.

- Rogers KH, Luton R, Biggs H, Biggs R, Blignaut S, Choles AG, Palmer CG, Tangwe P. 2013. Fostering complexity thinking in action research for change in social–ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 18(2) doi:10.5751/ES-05330-180231.

- Roux D, Clements H, Currie B, Fritz H, Gordon P, Kruger N, Freitag S. 2020. The GRIN meeting: a ‘third place’ for managers and scholars of social-ecological systems. S Afr J Sci. 116(3–4):1–2. doi:10.17159/sajs.2020/7598.

- Roux DJ, Nel JL, Cundill G, O’Farrell P, Fabricius C. 2017. Transdisciplinary research for systemic change: who to learn with, what to learn about and how to learn. Sustainability Sci. 12(5):711–726. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0446-0.

- Salgado FP, Abbott D, Wilson G. 2018. Dimensions of professional competences for interventions towards sustainability. Sustainability Sci. 13(1):163–177. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0439-z.

- Schneider F, Giger M, Harari N, Moser S, Oberlack C, Providoli I, Schmid L, Tribaldos T, Zimmermann A. 2019. Transdisciplinary co-production of knowledge and sustainability transformations: three generic mechanisms of impact generation. Environ Sci Policy. 102:26–35. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2019.08.017.

- Scholz RW, Steiner G. 2015. The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: part I—theoretical foundations. Sustainability Sci. 10(4):527–544. doi:10.1007/s11625-015-0326-4.

- Seidl R, Brand FS, Stauffacher M, Krütli P, Le QB, Spörri A, Meylan G, Moser C, Gonzalez MB, Scholz RW. 2013. Science with society in the anthropocene. Ambio. 42(1):5–12. doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0363-5.

- Sellberg MM, Cockburn J, Holden PB, Lam DPM. 2021. Towards a caring transdisciplinary research practice: navigating science, society and self. Ecosyst People. 17(1):292–305. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1931452.

- Star SL, Griesemer JR. 1989. Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Soc Stud Sci. 19(3):387–420. doi:10.1177/030631289019003001.

- Steelman TA, Andrews E, Baines S, Bharadwaj L, Bjornson ER, Bradford L, Cardinal K, Carriere G, Fresque-Baxter J, Jardine TD, et al. 2019. Identifying transformational space for transdisciplinarity: using art to access the hidden third. Sustainability Sci. 14(3):771–790. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0644-4.

- Steffen W, Broadgate W, Deutsch L, Gaffney O, Ludwig C. 2015a. The trajectory of the anthropocene: the great acceleration. Anthropocene Rev. 2(1):81–98. doi:10.1177/2053019614564785.

- Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, de Vries W, de Wit CA, et al. 2015b. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 347(6223):6223. doi:10.1126/science.1259855.

- Steffen W, Rockström J, Richardson K, Lenton TM, Folke C, Liverman D, Summerhayes CP, Barnosky AD, Cornell SE, Crucifix M, et al. 2018. Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115(33):8252–8259. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810141115.

- Steger C, Boone RB, Warkineh Dullo B, Evangelista P, Alemu S, Gebrehiwot K, Klein JA. 2022. Collaborative agent-based modelling for managing shrub encroachment in an Afroalpine grassland. J Environ Manage. 316:115040. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115040.