ABSTRACT

Despite increasing efforts by research and policy to approach sustainability, human impact on nonhuman nature is intensifying the current social-ecological crisis. To foster sustainability transformation, there is a need to re-think qualities of human-nature connections which calls for relational discourses that provide alternatives to the predominance of mindsets postulating a human-nature divide. Against this backdrop, this conceptual paper introduces ‘human-nature resonance’ as a relational account that provides system, target, and transformation knowledge for sustainability transformation. The paper argues that the social-ecological crisis has one of its root causes in mute human-nature relations. On this basis, it is illustrated how the social-ecological crisis is only slightly affecting the behaviours of Western societies, which are subsequently failing to establish responsive human-nature relations. Considering that mute relations are fostered by making the world constantly available, the non-affective human-nature relation can be traced back to a lack of material and moral boundaries of nonhuman nature perceived as a lifeless object of infinite availability. For strengthening human-nature resonance, the paper calls for the vision of human-nature partnership neglecting hierarchical human-nature relations. To strengthen the human-nature partnership, nature will speak with an own voice by assigning her legal personhood, agency, and soulfulness. Furthermore, human self-efficacy needs to be strengthened to listen to nature by nourishing internal relational capacities such as compassion and self-worth. Future work on human-nature resonance can integrate basic and applied inter- and transdisciplinary research which links natural and social sciences, Western and Indigenous ontologies, and the scientific world of logos and transcendental wisdom.

Edited by:

1. Introduction

Despite increasing efforts by research and policy to approach sustainability, society’s impact on nonhuman nature is intensifying the ecological crisis such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion (Steffen et al. Citation2015; Martin et al. Citation2016; Zeng et al. Citation2020). For a significant turnaround, current sustainability research calls for engagement with fundamental paradigms as ‘deep’ leverage points for transformational change (Meadows Citation1999; Abson et al. Citation2017; Leventon et al. Citation2021), addressing particularly paradigms and visions of the system associated with human-nature relations (Ives et al. Citation2018; Riechers et al. Citation2021; Chapin et al. Citation2022). Such research should reflect on how to overcome dichotomies between society-nature and human-nonhuman (Martin et al. Citation2016; West et al. Citation2020) mirrored in current scientific concepts such as ecosystem services emphasising the utilitarian value of nonhuman nature serving humanity to foster economic growth and prosperity (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). It is argued that the modern human/nature dichotomy has arisen from the Greek philosophical traditions of Aristotle and Judaeo-Christian mythologies, which define human mind and reason as being either superior or inferior vis-à-vis everything else, whereby mind and reason are considered to be in opposition to nonhuman nature. This human-nature dualism in Western culture was made explicit in the Age of the Enlightenment by Rene Descartes (1596–1650), considering nonhuman nature to be mindless, lifeless and non-agentic, a soulless object that can be instrumentally controlled, manipulated, and mastered to meet human needs (see for an overview of the history of human-nature relation Plesa Citation2019; Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021).

The manipulation and mastering of nonhuman nature by human activities describe dominant human-nature relations found in Western and industrial societies, assigning nonhuman nature, in particular utilitarian values, and resulting in unprecedented environmental changes (Muhar and Böck Citation2018; Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). These changes are bringing about the transcendence of planetary boundaries and threatening human’s safe-operating space (Rockström et al. Citation2009; Steffen et al. Citation2015a). Scholars argue that, in particular, human modes of production and consumption cause fundamental shifts in the status and functioning of the Earth system (Steffen et al. Citation2015b; Folke et al. Citation2021). In order to avoid continuation of the trend that humans are negatively impacting the planet, thereby threatening our home, Folke et al. (Citation2021) emphasise that humans need to realise that society is part of, intertwined with and reliant on the biosphere, pointing out the interconnection between local events and global challenges that shape one another. However, it is argued that the global perspective of concepts such as planetary boundaries only slightly affects human’s immediate living environment (Cooke et al. Citation2016). To make the abstractness of planetary boundaries comprehensible, Cooke et al. (Citation2016) argue for a dwelling perspective based on the ideas of Ingold (Citation2011). By emphasising mental and embodied qualities of human – environment (re-)connection, the dwelling perspective suggests ‘that earth stewardship has to come, in part, from people’s involvement and experience of their lifeworld’ (Cooke et al. Citation2016, p. 839). However, if aiming to translate global into local sustainability through people’s engagement in their intimate environment, we need to ask how individuals are relating to modern worldviews that ignore human’s embedding into the biosphere (Folke et al. Citation2011)? Or to formulate it more directly, how are individual or collective actors, both relevant for sustainability transformation (O’Brien Citation2018; Wamsler et al. Citation2021), affected by the social-ecological crisis in a Western lifeworld, and how can they respond to it beyond the paradigm of Mastery over nature threatening human’s safe-operating space?

In order to gain a better understanding of human-nature connections and its needed qualities to respond to the sustainability crisis, there is a call for relational approaches in sustainability science (Walsh et al. Citation2020; West et al. Citation2020). In normative terms, such relations consider qualities of human-nature processes and outcomes that foster a flourishing life for nonhuman and human nature and overcome hierarchical human-nature relations lacking limits to exploit and control nonhuman nature (Chan et al. Citation2018; Enqvist et al. Citation2018). An understanding of human-nature relations beyond dualistic and utilitarian approaches is in particular meaningful for the Western living environment, which is characterised by a paradigm of human-nature divide (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021) and intensifying the global social-ecological crisis through its predominant understanding of development linked to economic growth and acceleration (Brand et al. Citation2021).

Considering the need to focus on human-nature relations from a dwelling perspective (Cooke et al. Citation2016), the social-ecological crisis can be explained by a resonance dilemma, which argues that sustainability challenges do not affect most people’s everyday lives enough (Meyer Citation2015). The term resonance is taken up by only a few sustainability scholars to describe the lack of consternation of individual and collective actors vis-à-vis today’s environmental challenges due to, for example, ignorance (Weder and Voci Citation2021) or illogical thinking (Bush Citation2014). Further studies work with resonance terminology to identify solutions to overcome the gap between scientific knowledge and actions (Hall et al. Citation2017) by, for example, streamlining the supply of and demand for governance through credibility and salience (Peña Citation2018). However, either these sustainability studies use resonance as a metaphor without any deeper conceptual grounding for sustainability transformations (Bush Citation2014; Weder and Voci Citation2021) or the embedded theory does not aim at a relational human-nature discourse to overcome the hierarchical human-nature divide (Hall et al. Citation2017; Peña Citation2018).

When looking for frameworks having the potential to describe non-hierarchical relations that modern societies maintain, such as with nonhuman nature, the theory of resonance developed by Rosa (Citation2019) provides a comprehensive approach. The social science theory linked to Critical Theory aims at providing a solution for acceleration-orientated modern societies characterised by an increasing alienation from body, work, and nature, for example. The term resonance is adapted from physics describing relations between a subject and an object as a co-vibrating system in which both sides mutually reinforce one another. Rosa (Citation2019) uses the term as a metaphor to describe responsive relations between humans and the world whereby resonance is the positive counter-term for alienation leading to mute relations. In this regard, the theory has a descriptive and normative character, describing the quality of relations and providing a normative ‘metacriterion of successful life’ (Rosa Citation2019, p. 451). A range of researchers values the theory of resonance for its innovative and comprehensive approach in academia and beyond. It is valued for its critical and comprehensive reflection of modern society and our multi-faceted economic, social, and environmental crisis as symptoms of an increasing alienation. These researchers argue that the theory has the capacity to overcome the Cartesian dualism existing between individuals, society, and nature (Fuchs Citation2020; Masquelier Citation2020; Susen Citation2020). However, due to its comprehensive character, there is a need to further specify the theory for everyday practices and its contribution to transformational change (Masquelier Citation2020).

This research gap paves the way to enrich the resonance theory as a relational human-nature account for sustainability science. In doing so, I acknowledge that I, as an adult German citizen living and working in a Western, industrialised country in Europe, have been instilled thereby with a certain cultural background and understanding of human-nature relations which differs from social paradigms found in other parts of the world. In Section 2 I lay out the theoretical ground-work introducing the resonance theory by Rosa (Citation2019). In Section 3 I elaborate on the concept of human-nature resonance and discuss it in Section 4. Conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2. Theoretical grounding – the resonance theory

The starting point of Rosa’s (Citation2019) work on the sociology of human relations with the world is that the quality of a good human life is not simply dependent on the amount of available resources or options; rather, it is in particular influenced by how humans relate to the world. Describing different forms of world-relations, the opposition between resonance and alienation establishes the conceptual basis for the theory. Resonance can be read as the quality of relations that ‘(…) rest on the idea of an intrinsic connection or correspondence, a mutual reaction in the sense of a genuine response’ (Rosa Citation2019, p. 58, emphasis in original). According to Rosa (Citation2019), the mindset of world scope enlargement corresponds to an attitude of making the world instrumentally available, editing and optimising it by, for example, increasing commodities and options for action through technology and money, which leads to mute relations. Mute relations comprise relations with objects such as resources, instruments or causal links that can be controlled, exploited and/or dominated. Thus, resonating relations demand that subjects and objects are relatively autonomous and have a significant degree of independence while being, at the same time, intertwined with each other. Therefore, resonance should not be interpreted as an echo but describes responsive relations, which requires that subject and the world ‘each speak in their own voice’ (Rosa Citation2019, p. 174).

Based on theories of empathy and mirror neurons (nerve cells that show the same pattern of activity from the brain of the one observing an action as the one conducting it) as well as relating to research in the field of self-efficacy, Rosa (Citation2019) defines resonance as a specifically cognitive, affective, and bodily relationship to the world in which subjects are touched and occasionally even ‘shaken’ down to the neural level by certain segments of the world, but at the same time are also themselves ‘responsively’, actively, and influentially related to the world and experience themselves as effective in it ‒ this is the nature of the responsive relation or ‘vibrating wire’ between subject and world (Rosa Citation2019, p. 163). Thus, resonance requires first to be touched (i.e. affected) by an object, followed in a second step by a non-instrumental answer described as a responsive self-efficacy emphasising the capacity to affect a relating entity without dominating or commanding it. A third key characteristic of resonance is a moment of adaptive transformation in which both relating entities mutually transform themselves and their relation with each other. The process of transformation is not necessarily life-changing but can include daily resonance experiences that shape how a social subject is relating to a segment of the world (Rosa Citation2019).

All in all, due to the comprehensive analysis of the various relations humans hold with the world, Rosa (Citation2019) is not elaborating the role of human-nature resonance in detail, also not referring to sustainability science. Therefore, the next section conceptualises how the theory of resonance can be specified for human-nature relations in light of the social-ecological crisis, referring thereby to research from sustainability science. This paper adds to existing sustainability literature dealing with the term of resonance by providing a comprehensive concept that contributes to a relevant societal system knowledge (what is), target knowledge (what should be), and transformation knowledge (how to go there) (Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn Citation2007). In particular, the paper aims at contributing to the recent relational discourses in sustainability science (Walsh et al. Citation2020; West et al. Citation2020; Böhme et al. Citation2022) providing alternatives for hierarchical relations between human and nonhuman nature (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021) and considering the interplay between internal and external sustainability transformations (Ives et al. Citation2020; Wamsler et al. Citation2021; Böhme et al. Citation2022).

3. Human-nature resonance in times of the social-ecological crisis

Following the ideas by Rosa (Citation2019) to describe the quality of relations humans hold with their world, the concept of human-nature resonance reflects on the social-ecological crisis as the result of mute non-affective and thus non-responsive human-nature relations in the context of Western living worlds (system knowledge, see Section 3.1). From a social theory perspective, ‘affection’ and ‘affect’ are ‘fundamental because they describe – in this generality – all that can happen to human and nonhuman entities (…)’. (Saar et al. Citation2021, p. 75) In terms of human-nature resonance ‘affection’ and ‘affect’ are understood as a change in the state of the relating entity that has concrete effect on the individual or collective practices (McCormack Citation2003; Thoburn Citation2007). I argue that the lack of affection traces back to hierarchical human-nature relations muting nonhuman nature’s voice by disrespecting her material and immaterial limits. At the same time, human nature is muted by avoiding affection and lacking openness to listen to nonhuman nature’s responses while disrespecting her unavailability. According to Rosa (Citation2020) unavailability exemplifies the needed societal balance between making the world visible and accessible without making it constantly available, which leads to mute relations. Based on these elaborations, I explore in Section 3.2 alternatives for hierarchical worldviews of human-nature relations by elaborating on the vision of human-nature partnership as part of a good life and guiding societal principle that paves the ground for shifting from mute to resonating human-nature relations (target knowledge). By neglecting dominance and exploitation, the human-nature partnership acknowledges that both relating entities can speak with an own voice and are open to listen to each other. How human and nonhuman self-efficacy to listen and respond to each other can be strengthened (transformation knowledge), I elaborate in Section 3.3. In this context, I reflect on Indigenous ontologies to strengthen nonhuman nature’s voice. Human capacities to hear and respond to nature’s voice are explored based on ideas of ecopsychology and inner transformations. By referring to these approaches, crucial and timely relational discourses in sustainability science are taken into account (Ives et al. Citation2020; Walsh et al. Citation2020; Wamsler & Bristow, Citation2022; Böhme et al. Citation2022).

provides an overview of the main pillars of the resonance theory by Rosa (Citation2019, Citation2020) and its translation into human-nature resonance for sustainability science, which I develop in depth in the subsequent sections. In this regard, I have to add that the order of resonance pillars illustrated in is not identical with the one by Rosa (Citation2019) describing a flow from affect, response, to transformation. However, by placing ‘transformation’ before ‘response’ puts emphasis on the need to rethink current system goals and paradigms of human-nature relations as a major precondition to foster responses that bring deep changes towards sustainability (cf. Abson et al. Citation2017; Ives et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. Main terms of the resonance theory and their embedding into human-nature resonance.

3.1 The social-ecological crisis resulting from mute human-nature relations

3.1.1 The role of affect in human-nature resonance

Despite increasing impacts from the social-ecological crisis and international policy goals to combat them (e.g. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals or the Paris Climate Agreement), current policy responses have insufficient capacity to foster deep transformation such as decarbonisation (Scott and Gössling Citation2021; Stammer et al. Citation2021). Also, on the individual level, there is a lack of adequate pro-environmental response to the crisis, taking into account some of the most efficient climate-friendly behaviours such as car-free existence, cutbacks in air travel or following a plant-based diet (Ivanova et al. Citation2020). In this regard, current German statistics, as an example of a Western living environment, suggest an increase in car use per 1,000 inhabitants from 532 to 580 between 2000 and 2020 (Federal Environment Agency Citation2021). Furthermore, the frequency of flights saw a new record in 2019 (Destatis Citation2020) and only 3% of the German population is vegan (Brandt Citation2020). Against this backdrop, these non-responsive human-nature relations can be interpreted as a result of a deficit of affections vis-à-vis the social-ecological crisis in Western lifeworld. Thereby human-nature resonance links to affect studies found in relational sustainability discourses (Walsh et al. Citation2020), whereby a stream of research differentiates between affect, emotions and cognition to describe more precisely that affect appears before it can be translated into a knowable cognition and emotion (Massumi Citation2002; Maller Citation2018). In fact, Rosa (Citation2019) also emphasises that resonance should not be understood as an emotional state but as a type of relation which remains open to its emotional content.

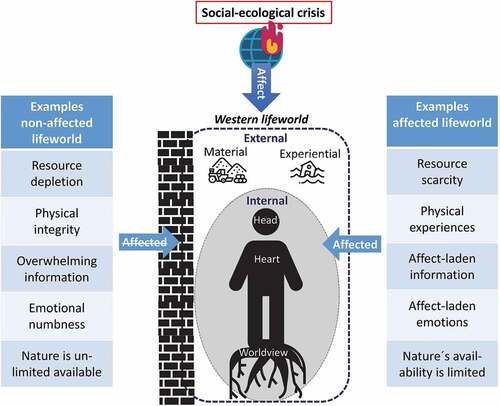

Human-nature resonance considers internal and external approaches for how the social-ecological crisis will eventually affect the Western living environment, thereby providing system knowledge to explore insufficient responses to the social-ecological crisis. It must be mentioned that these examples of being affected are not and cannot be conclusive, taking into account the dynamic and complex nature of the social-ecological crisis. Nevertheless, in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of various potential affections, I apply the structure of human-nature connections by Ives et al. (Citation2018), which takes into account the breadth of external (material, experiential) and internal (cognitive, emotional, philosophical) dimensions.

3.1.2 A lack of external and internal affection vis-à-vis the social-ecological crisis

Material human-nature connections describe the consumption of goods and materials supplied by nonhuman nature (e.g. food, fibre) (Ives et al. Citation2018). In the context of human-nature resonance, material affection vis-à-vis the social-ecological crisis describes how we deal with the finite supply of natural resources, considering our material dependence on nonhuman nature which is becoming increasingly neglected in an era of rapid urbanisation, technologisation, and globalisation of capital (cf. Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). Although the current COVID-19 pandemic or the Ukraine–Russia crisis have rendered visible the material vulnerability of the global flow of goods, such as food- and energy supply chains (Singh et al. Citation2021; Shams Esfandabadi et al. Citation2022), Western societies merely acknowledge the finiteness of nature’s material resources suggesting a mute material human-nature relation. For instance, research suggests that the European Green Deal policy, which is aiming for a carbon-neutrality continent by 2050, is failing to pave the way towards structural changes for a post-carbon economy. It even intensifies global and unjust material nature exploitation and destruction due to a lack of long-term European vision beyond market-based solutions and unjust exploitative geopolitical targets (Pianta and Lucchese Citation2020; Dunlap and Laratte Citation2022).

In fact, the world scope enlargement as a major driver for mute relations (Rosa Citation2019) can also be read as an enlargement of global resources that materially disconnect Western populations from nonhuman nature. In sustainability science, global linkages between distant places shaping interdependences between local and global sustainability are referred to as telecoupling, whereby this ‘global inter-regional connectedness’ (Kissinger et al. Citation2011, cited in Newig et al. Citation2020, p. 1) can be reflected as a driver for material human-nature alienation. This can be traced back to the complex and distant worldwide supply chains making it almost impossible for consumers to comprehend the ecological and social conditions of the production of material goods (Boström Citation2020). Furthermore, mass and excess consumption is part of modern life reinforced by institutions following a pro-growth paradigm crucial to stabilising the capitalist economic system (Welzer Citation2011; Boström Citation2020). In this context, I argue that the focus of sustainability research on material human-nature resonance of Western growth- and acceleration-oriented societies is in fact meaningful. Thus, Western everyday material life is shaped by an imperial mode of living. This concept describes how the Western mode of production and living, which is mainly found in the Global North, fosters the exploitation of social and ecological resources of distant places to secure itself a high standard of living (Brand et al. Citation2021b). By doing so, an imperial mode of living neglects societies’ material interdependence with the biosphere (Folke et al. Citation2021), externalises the negative impacts of Western lifestyles to less-developed countries (Lessenich Citation2019), and harms planetary justice (Biermann and Kalfagianni Citation2020).

This material indifference towards nature’s limited resources fosters the trend that the consequences of the social-ecological crisis have hardly been experienced physically (i.e. by bodily experiencing floods or heat waves) in the living environment of Western societies in the past. However, this is changing rapidly. For instance, while the Climate Risk Index shows that between 1999 and 2018 in particular poor countries including Puerto Rico, Myanmar, and Haiti have been most impacted by extreme weather events, in 2018 also high-income countries such as Germany and Japan belong to the most affected countries suffering from heatwaves as a result of climate change (Eckstein et al. Citation2020). Thus, in experiential terms, it can be expected that the social-ecological crisis, particularly in reference to climate change (IPCC Citation2021), will increasingly affect Western living environments. This calls for quick responses towards sustainability transformation to overcome the material and experiential indifference, which can be interpreted as mute human-nature intra-actions that neglect the deep impacts that human actions evoke (Böhme et al. Citation2022). In contrast to ‘interaction’, ‘(…) which assumes that there are separate individual agencies that precede their interaction, the notion of intra-action recognizes that distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action’ (Barad Citation2007, p. 33), emphasising that distinct’ agencies are not existing as individual elements but are mutually entangled (Barad Citation2007).

To avoid intensification of the harmful external consequences by the social-ecological crisis and to bridge the physical distance between affected and non-affected relating entities, research and media take on an important role in informing the public of the social-ecological crisis. In the course of technological developments such as remote sensing or social media, sustainability orientated knowledge and information for decision makers and citizens is more comprehensive than ever before (Seppelt and Cumming Citation2016; Folke et al. Citation2021). In fact, the current nature awareness study in Germany, which takes place every two years, shows, for the first time since the beginning of the study in 2009, a significant increase in awareness of biodiversity including aspects such as sufficient knowledge, coherent attitudes, and readiness for acting pro-environmentally (BMU Citation2020). But why is there, despite a public pro-environmental orientation no significant turnaround (see Section 3.1.1)? Through the lens of the resonance theory, the lack of affection can be interpreted by taking into account two major preconditions for resonance: unavailability and openness (Rosa Citation2019, Citation2020).

In terms of unavailability, a major prerequisite of resonating relations is a certain degree of autonomy to touch and be touched (Rosa Citation2019). However, nonhuman nature’s autonomy is blocked by disrespecting limits of her material and immaterial availability. Thus, nature’s exploitation and utilisation is based on the worldview that nonhuman nature predominantly holds instrumental value and lacks agency, intelligence, and sentience, thereby ‘dehumanising’ and limiting empathy towards her (Fiske Citation2009; Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). Furthermore, for developing resonating relations according to Rosa (Citation2019), the subject needs to have a certain degree of openness towards the relating segment of the world. In the context of human-nature relations, human openness towards nature can be assumed when following the biophilia hypothesis. This idea suggests that human beings possess as a consequence of evolution an instinctive affective-tendency to connect with nonhuman nature (Wilson Citation1984). However, today there is a risk of mass ignorance in everyday life concerning human’s destruction of the natural world (Boström Citation2020). Mentally, this can be explained by the complexity of the crisis and often overwhelming images such as burning forests or floods, leading to mental coping mechanisms driven by increased stress and anxiety thereby fostering denial and avoidance as well as a decrease in empathy and compassion (Wamsler & Bristow, Citation2022). Lacking limits of nonhuman nature’s availability and human internal relational capacities to overcome emotional numbness and information that lacks affect can be considered as a root cause for mute human-nature relations (see ). To foster a re-framing of hierarchical human-nature relations and dystopic futures calls for positive visions that inspire innovative thinking and ideas for a good life for human and nonhuman nature (Chapin et al. Citation2011; Bennett et al. Citation2016; McPhearson et al. Citation2016). What a positive vision for human-nature resonance could look like, I explore in the next section.

3.2 Fostering resonance by targeting human-nature partnership

To overcome the mental infrastructure shaped by the demand to secure Western living standards through economic growth, consumerism, optimisation, progress and non-existing limits, positive visions of a good life beyond materialistic lifestyles are needed (Welzer Citation2011). These can be informed by worldviews found in the Global South (e.g. Buen vivir, Taoism) grounding a good life in solidarity, ethical values, reciprocity, and human’s embedding within nonhuman nature (Brand et al. Citation2021). By taking into account the fact that lacking affections by the social-ecological crisis can be traced back to hierarchical human-nature relations (see Section 3.1.2), the need for considering limits of nature’s material and immaterial availability becomes obvious. In fact, human-nature resonance is linked with the concept of unavailability as a basic prerequisite for resonance (Rosa Citation2020). In this regard, mute relations can be traced back to human efforts to increase the availability of the world by making it visible, accessible, controllable, and useable (Rosa Citation2020).

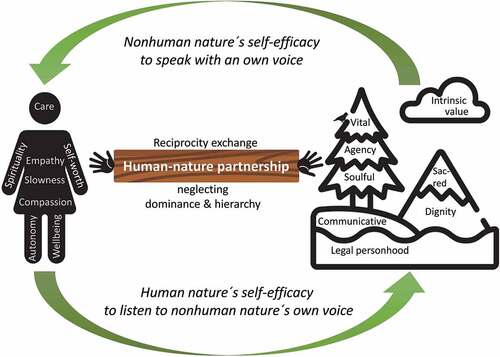

Limits of nature’s availability can be embedded into the positive vision of human-nature partnership, which consider nonhuman nature as a relating subject (not object) having agency (De Groot Citation1992; Muradian and Pascual Citation2018). Human-nature partnership characterises then the system intent and its values, goals, and norms (cf. Abson et al. Citation2017) that are needed to transform human-nature relations from mute to resonating qualities. Qualities of human-nature partnership point out the capacity that both human and nonhuman nature have the right to speak with an own voice (cf. Rosa Citation2020) and thus to flourish, respecting that both sides as well as their relations hold intrinsic value and are related to each other through a reciprocity exchange of giving and taking while neglecting dominance and hierarchy (De Groot Citation1992). The reciprocity exchange of giving and taking can also be an important pillar for strengthening human openness to become affected by and respond to the crisis with sustainability transformation. Thus, while humans respond to the social-ecological crisis through sustainability actions, they can also receive a positive response by nonhuman nature in external or internal terms. In material terms, for instance, by applying sustainable farming techniques that are good for human and nonhuman nature (McKenzie and Williams Citation2015); in internal terms, by being proud of the positive effects of pro-environmental behaviour on others (Landmann Citation2020). Experiencing that sustainable actions are not necessarily acts of self-limitation but an added value of quality of life is crucial for fostering sustainable development (Martin et al. Citation2016). Therefore, through human-nature resonance, sustainability is not experienced as a burden but as a basic component for a good life. It addresses a relational approach to planetary health emphasising that personal human wellbeing is interrelated with societal and ecological wellbeing, which provides an explanation for why transformations to sustainable lifestyles matter (Böhme et al. Citation2022). However, this will need an increase in human and nonhuman self-efficacy to step out of the Western societal paradigm of economic growth and acceleration promoting materialism, consumerism, and individualism and constraining relational qualities such as kindness, empathy, compassion and mental health (Welzer Citation2011; Ives et al. Citation2020; Wamsler & Bristow, Citation2022). This increase in self-efficacy can be read through the lens of the resonance theory to nourish nonhuman nature to speak with an own voice, which is heard and responded to by humanity fostering and implementing actions for sustainability transformation. How such transformation knowledge can be approached through the concept of human-nature resonance, I explore in the next section.

3.3 Increasing human and nonhuman self-efficacy to foster human-nature resonance

3.3.1 Nonhuman nature´s self-efficacy to speak with an own voice

Despite the finiteness of natural resources, Western societies are rarely impacted due to their imperial mode of living and rendering nonhuman nature constantly materially accessible (see Section 3.1). In this regard, societal boundaries are required to keep within the safe operating space of planetary boundaries emphasising the need for a policy of self-limitation (Brand et al. Citation2021a). The responsibility of self-limitation as a form of autonomy can be interpreted as the freedom not to follow the modern paradigm of growth and acceleration considering self-limitation as austerity (Brand et al. Citation2021a). Autonomy must then not be interpreted as independent and individual choices neglecting external norms but enabling ‘(…) the conditions for a good life for all rooted in the actual freedom of not having to live at the expense of (human and non-human) others’ (Brand et al. Citation2021a, p. 277).

In fact, human-nature resonance considers the autonomy of human and nonhuman nature. A relational autonomy can then be interpreted as the need to perceive nonhuman nature as a vibrant being having a certain degree of autonomy and agency (or voice), which allows humans to listen and react to nature’s actions and feedback. In this regard, human-nature resonance can be linked to Indigenous ontologies describing a worldview that assigns nature agency as a communicative, vital, sacred, and soulful community member having intrinsic value to be respected and protected (Snodgrass and Tiedje Citation2008; Kealiikanakaoleohaililani and Giardina Citation2016; Kohler et al. Citation2019). Overcoming the attitude that nonhuman nature is considered to be an available and thus powerless object in Western societies addresses the need to give her legal personhood, which is the approach in Ecuador, India, or New Zealand (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021). In moral-relational terms, an inclusion of nonhuman entities in the community of justice secures nature’s dignity and thus self-efficacy to flourish (Fulfer Citation2013). In recent years, a re-thinking seems to be taking place in Western countries. For instance, the European Economic and Social Committee Citation2020 published a study that advocates the fundamental rights of nonhuman nature, which is recently also emphasised in current sustainability research (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021; Pope et al. Citation2021). Acknowledging diverse knowledge systems in science and policy beyond Western worldviews and practices can then strengthen to raise the voice of nonhuman nature for a relational paradigm in sustainability science (cf. Brand et al. Citation2021; Böhme et al. Citation2022). However, to deeply listen to nonhuman nature, an increase in internal relational capacities of human nature is needed as well, which I discuss in the next section.

3.3.2 Humanity´s self-efficacy to speak with an own voice

Recognising the urgency for sustainability transformation, a growing body of sustainability research calls for consideration of the role of internal transformation (Wamsler et al. Citation2018; Ives et al. Citation2020; Woiwode et al. Citation2021). Said urgency becomes also evident in this paper arguing that the social-ecological crisis is caused by a lack of internal affection blocked by a lack of openness to listen to nonhuman-nature’s voice calling for the need to respect limits of her availability. For instance, in the course of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Txai Suruí, an activist from the Brazilian Amazon, warned that ‘The Earth is speaking: she tells us we have no more time’ (Zarraga Citation2021). That humanity is running out of time to adapt to the climate crisis and to secure human and nonhuman nature’s wellbeing is also warned in the current IPCC (Citation2021) report. In order to listen to this urgency, a shift from a morality of care rather than utility is needed (Jax et al. Citation2018; Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021) that is linked with internal relational capacities of compassion and empathy with oneself, other people and the world as a crucial skill for supporting harmonious human-nature relations (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021; Wamsler et al. Citation2020).

In this regard, to listen to the needs of nonhuman and human nature, the mutual entanglement between the external and internal world plays a crucial role. According to ecopsychology, which reflects on transpersonal relationality and the need within modern society for an affective relational extension to encourage connectedness to nature (Adams Citation2012), the instrumentalisation of the external environment is mirrored in a mute relation with one’s inner world and vice versa, whereby human connection with nonhuman nature can for instance be constrained by an inner feeling of meaninglessness, anxiety, and powerlessness, which inhibits improvement of one’s own life (Softas-Nall and Woody Citation2017). This calls for the development of a transpersonal relationality that transcends human-centeredness, a trait that inhibits the fullness of human-beings and deep relations (Adams Citation2010; Palamos, Citation2016). ‘The industrialised individual is not lacking in terms of an “inner emptiness”, then, but rather an affective relational extension’. (Kidner Citation2001, cited in Adams Citation2012, p. 220, italics in original). In fact, similar to the work from ecopsychology (Kamitsis & FrancisSnell et al. Citation2011; Fulfer Citation2013), also Rosa (Citation2019) sees the risk of mute relations within modern societies, characterised by rational and instrumental relations, and due to a loss of sensitivity to spiritual consciousness and ‘metaphysical axes of resonance’ (Rosa Citation2019, p. 40, italics in original).

Taking the interplay between internal and external worlds seriously, a change in values of nonhuman nature from instrumental to intrinsic values requires an internal human capacity for self-affection describing a mode of self-worth (see ). In this regard, it has to be emphasised that intrinsic value and self-worth is neither understood as a form of ego-centric or individualistic character, which is criticised as an anti-ecological way of being (Adams Citation2010; Parry Citation2016; Fisher Citation2019). Nor is it defined as instrumentalised self-worth aiming at self-optimisation (e.g. in terms of attractiveness, performance), leading to a mute relationship with oneself (Rosa Citation2019). Internal self-affection in the frame of human-nature resonance refers to a mode of self-respect and self-compassion that shows appreciation for his or her own being (Reser Citation1995; Hay Citation2005). Cultivating reciprocal relations thus includes an internal human healing process by means of ‘(…) slowness, humility, creativity, embodied and direct engagement, dreaming, dancing, attentiveness, open-heartedness, open-mindedness, gratitude, partnership working, staying flexible, and listening as part of this new way of being’ (Warber et al. Citation2020, p. 226)'. On a structural level, this will need to bridge the split between external and internal dimensions refocusing the current emphasis on technological solutions for the crisis to the role of inner dimensions to overcome mental barriers constraining fundamental changes towards sustainability. This includes, for instance, professional training to reduce negative impacts of climate change threats on mental health and transformative leaders informed about psychological barriers blocking internal affections by the social-ecological crisis (Wamsler & Bristow, Citation2022). Thus, if for instance climate anxiety is blocking or motivating sustainable behaviour, it harkens back to the personal inability to cope with such threats (Clayton Citation2020). Through the lens of the resonance theory (Rosa Citation2019) what is required then is a balance between the openness to being affected by threatening information and the self-efficacy to regulate one’s inner world in order to avoid, for example, media overload leading to climate anxiety (cf. Wamlser & Bristow, Citation2022). Speaking with an own voice to foster human-nature resonance then means as well to be a good partner for oneself as a precognition to foster a shift of individuals and groups ‘(…) from being seen as “objects to be changed” (…) to viewing themselves as subjects or agents of change who are capable of contributing to systemic transformations’ (O’Brien Citation2018, p. 157).

4. Discussion

Since conceptual debates on relational discourses in sustainability science are in their infancy (Walsh et al. Citation2020; West et al. Citation2020), the overall objective of the paper has been to translate the resonance theory by Rosa (Citation2019) into human-nature resonance as a relational account for sustainability science contributing to system, target, and transformation knowledge. In this regard, I have explored the lack of external and internal affections within the social-ecological crisis in Western societies as a potential explanation for missing transformational change (system knowledge, see Section 3.1). This lack of affection can be traced back to disrespecting limits of nonhuman nature’s material and immaterial availability muting her voice. To overcome these mute relations, I call for a positive vision of human-nature partnership as part of a good life (target knowledge, see Section 3.2). To explore potential pathways towards human-nature resonance, the paper reflects on Indigenous ontologies calling for a societal paradigm shift that increases nonhuman nature’s self-efficacy to speak with an own voice by assigning her legal personhood, agency, and soulfulness (transformative knowledge, see Section 3.3). In this regard, the concept of human-nature resonance enhances ideas of ‘(…) ecological justice, which evokes notions of reciprocity and care for humans and non-human entities, and so requires the exploration of new regulations and procedures for recognizing and managing the rights of the non-human’ (McPhearson et al. Citation2021, p. 9). This will require as well the strengthening of human’s internal self-efficacy to cope with the complexity of the crisis and to listen to nonhuman nature’s voice developing capacities such as empathy compassion, and self-worth.

As a relational account for sustainability science, the concept of human-nature resonance draws attention to the need to assume a relational perspective for our daily actions and political agendas which supersede individual responsibility for and promotion of solidarity among human and nonhuman beings who are affected by unsustainable Western modes of living. Thereby, I support the demand by Kueffer et al. (Citation2019) that what is required in the face of the complexity and urgency of the social-ecological crisis is a broadening of the concept of system, target, and transformation knowledge which takes into account the fact that knowledge production should not be dissociated from virtue ethics and relational qualities such as compassion or humility. How human-nature resonance contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the various forms of knowledge, I discuss in the upcoming sections. In this regard, it has to be emphasised that I do not claim to provide any definite knowledge regarding what human-nature resonance actually means; rather, I see its exploration as a process (cf. Kueffer et al. Citation2019). Therefore, I explore potential scopes of its application and advancement in the next sections as well.

4.1 Affection and self-efficacy to foster our sustainability system and transformation knowledge

A major focus of sustainability science is set on the production of system knowledge to better capture multi-scale and temporal environmental impacts by human actions. However, Kueffer et al. (Citation2019) argue that there is a risk of over-generalisation and -simplification of the complexity of social-ecological systems whereby, at the same time, research needs to deal with ignorance towards the social-ecological crisis on the part of humans as ambiguous and irrational beings who need to respond to it. In the face of these scientific challenges, human-nature resonance provides a framework that links transformative turning points (i.e. affect) of substantial external incidents and internal mindsets with actual behaviour as an expression of self-efficacy to listen to system knowledge and respond to the sustainability crisis; this is an approach that can be of merit to future relational sustainability science (Hertz et al. Citation2020; Raymond et al. Citation2021).

Human-nature resonance thereby aims not only to answer the crucial question why and in which contexts people resonate with, and thus engage in, everyday sustainability practices (Meyer Citation2015), but also how these can be fostered by the interruption of unsustainable routines and unconscious behaviours (Woiwode et al. Citation2021). These behaviours are embedded in a web of internal and external relations (Wamsler et al. Citation2022). To study the interplay between affect and responses through a relational lens, various spheres of resonance and their dynamic, nonlinear, and continuous flow mutually constituting one another can be taken into account. According to Rosa (Citation2019), these spheres include horizontal (family, friendship and politics), diagonal (relations with objects including work, school, sports and consumption) and vertical (transcendental relations with religion, art, history) resonance axes. These relations can describe any (de-)stabilisation of the individual’s sustainability response in conjunction with collective structures and practices, for instance, in terms of social relations (i.e. horizontal axis) such as lack of social support in sustainable dietary changes (Werner and Risius Citation2021) or spatial qualities (i.e. diagonal axis) such as strategic urban design fostering collectively sustainable change (Kaaronen and Rietveld Citation2021), or spiritual crises (i.e. vertical axis), such as populations that are disillusioned by an unsustainable lifestyle postulated in modern societies (Brand et al. Citation2021).

In order to systematically capture the complexity and dynamic of transformative turning points, qualitative methods in particular are meaningful; this includes focus groups or narrative interviews (Muhar and Böck Citation2018; West et al. Citation2020), which also take into consideration process-related long-term studies analysing respective cases confronted with changing phases in life or environments that can foster adaptions of unsustainable habits (Linder et al. Citation2021). To comprehensively capture a process-relational approach, current research calls for a post-qualitative inquiry into qualitative methodology (Wu et al. Citation2018; Darnhofer Citation2021; St. Pierre Citation2021). For instance, a post-qualitative inquiry approach suggests that it would be advantageous to rethink interviews from a point-of-view of intra-action such as between human–human or human–materiality (Bodén Citation2015). Intraviews include agential spaces and processes such as walking through parks or buildings, eliciting relational material, and embodied and affected responses (Kuntz and Presnall Citation2012). For the operationalisation of human-nature resonance, the potential web of external and internal affections (see section 3.1) can be used to define settings for intraviews or guiding questions along focus groups identifying, for instance, external affective experiences of embodied human-food relations at urban gardens (Artmann et al. Citation2021) or internal affective Indigenous knowledge translated into storytelling, fostering a spiritual understanding of nonhuman nature (McMillen et al. Citation2020). In this regard, human-nature resonance calls for transdisciplinary research and the increasing importance to translate scientific findings into more relational knowledge that touches the heads, hearts and souls of people (cf. Vogel and O’Brien Citation2021, see also , Section 3.1.2).

4.2 Human-nature partnership for nourishing sustainability target knowledge

Kueffer et al. (Citation2019) argue that sustainability science needs to critically reflect target knowledge and its underlying ethical reasoning to overcome unsustainable worldviews and values such as neglecting the dignity of all living beings. In fact, human–nature resonance provides an ethical framework based on the vision of human-nature partnership as guiding system intent ascribing nature relational qualities such as intrinsic values, sentience, and intelligence. In this regard, human-nature resonance is a call to overcome the modern societies´ acceleration paradigm requiring them to make the world increasingly visible and recognisable through a constant forward development in technologies, knowledge and projects generating alienation (Rosa Citation2020). Thus, technological innovations and increasing knowledge often reflect hierarchical human-nature relations. For instance, just recently, the first pig-to-human heart transplant took place (Reardon Citation2022), positioning the survival of the human over the animal through medical innovation. A stream of sustainable science criticises in this context that, in addition to more knowledge, more practical wisdom is required, which includes ‘(…) moral/ethical judgments about why and how certain ends are pursued or not’ (Fazey et al. Citation2020, p. 12). In terms of the vision of human–nature partnership, it is then not about understanding nonhuman nature by fully knowing or identifying with her, but co-existing with nature in a spiritual and lovely companionship considering nonhuman nature as a lively being (De Groot Citation1992).

However, how can the target of human–nature partnership be translated into daily lives? So far, the debates on human-nature partnerships are particularly discussed on a conceptual basis (De Groot Citation1992; Flint et al. Citation2013; Muradian and Pascual Citation2018), calling for a translation into daily routines in order to, for example, reflect on what exactly the human-nature partnership means in terms of atmospheric pollution due to air travel (De Groot et al. Citation2011). Referring to the example of just preservations as an approach to balancing protection and the use of nonhuman nature overcoming human exceptionalism, Treves et al. (Citation2019, p. 14) call for the appointing of human advocate-trustees for nonhuman nature who ‘(…) understand ecology, ethics, and the manifold, complex, dynamic interactions between humans and non-humans’. To operationalise such trustees for human-nature partnership, both basic and applied research is required. From a basic research perspective, the human-nature partnership embeds interdisciplinary research that, for instance, links social science with natural sciences such as plant cognition supporting an ontological shift to also acknowledge the agency and sentience of plants (Stephens et al. Citation2019). From an applied research approach, affect-laden experiential interventions with individual and collective actors (e.g. planners, policy makers), such as role playing, can support a more-than human perspective. For example, in the intervention ‘The Council of All Beings’, humans are invited to experience human-nature intra-actions bodily and emotionally by slipping into the role of nonhuman beings (e.g. plants, animals, landscape features) (Macy and Brown Citation2014). The human-nature resonance concept can then provide a basis for structuring the group reflection exercises exploring how participants in the role of nature become externally and internally affected in their daily human lives, thereby identifying how humanity can listen to nonhuman nature beyond domination and exploitation thereof.

5. Conclusion

Despite the general public and political agreement that a sustainability transformation is needed, fundamental responses are still lacking ‒ as if this social-ecological crisis were still too abstract and less urgent in the Western lifeworld. The question is: Do we have the time and, in particular, the moral courage to counteract the social-ecological crisis before it shakes all strata of populations and endangers this beautiful life on earth by rendering nonhuman nature extensively and forcefully available for human’s insatiable material needs? Would it instead not be more joyful and morally justifiable to acknowledge nonhuman nature’s dignity, relational and intrinsic value in our daily lives now and beyond any dystopian future? As a major leverage for sustainability transformation, current sustainability research proposes advancement of relational approaches overcoming hierarchical human-nature connections. Against this backdrop, by further elaborating the theory of resonance by Rosa (Citation2019) from the field of sociology, I introduce in this paper the relational account ‘human-nature resonance’ providing system, target and transformation knowledge for sustainability science. In the focus of the concept lies the hypothesis that the social-ecological crisis is harking back to non-affective and thus non-responsive mute human-nature relations in the living world of Westerners.

By suggesting a framework for analysing how Western societies become externally and internally (non-)affected by the social-ecological crisis, I visualise the need for an increased affection so that limits of nonhuman nature’s material and immaterial availability are respected. This will require a fundamental mindshift in Western societies from perceiving nonhuman nature as an object to be used and manipulated to a soulful family member that holds legal personhood, agency, dignity, and intrinsic value to speak with an own voice. The success of such a fundamental shift will strongly depend on human individual and collective internal capacities to listen to nonhuman nature by nourishing empathy and compassion beyond the Western mental infrastructure shaped by acceleration, economic growth, consumerism, individualism, instrumentalisation, and competition. In fact, human-nature resonance can then be experienced as a good life.

The paper invites further basic and empirical inter- and transdisciplinary sustainability research in the context of human-nature resonance to foster a dialogue between natural and social sciences, Western and Indigenous ontologies of nonhuman nature, and its various meanings of autonomy and justice, as well as between the scientific world of logos and transcendental wisdom.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful and supportive comments on an earlier draft. I am also very grateful for comments by the URBNANCE team and the advisory partners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abson DJ, Fischer J, Leventon J, Newig J, Schomerus T, Vilsmaier U, von Wehrden H, Abernethy P, Ives CD, Jager NW, et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio. 46(1):30–15. doi:10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Adams WW. 2010. Bashō’s therapy for narcissus: nature as intimate other and transpersonal self. J Humanist Psychol. 50(1):38–64. doi:10.1177/0022167809338316.

- Adams M. 2012. A social engagement: how ecopsychology can benefit from dialogue with the social sciences. Ecopsychology. 4(3):216–222. doi:10.1089/eco.2012.0037.

- Artmann M, Sartison K, Ives CD. 2021. Urban gardening as a means for fostering embodied urban human–food connection? A case study on urban vegetable gardens in Germany. Sustainability Sci. 16(3):967–981. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00911-4.

- Barad KM. 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bennett EM, Solan M, Biggs R, McPhearson T, Norström AV, Olsson P, Pereira L, Peterson GD, Raudsepp‐hearne C, Biermann F, et al. 2016. Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Front Ecol Environ. 14(8):441–448. doi:10.1002/fee.1309.

- Biermann F, Kalfagianni A. 2020. Planetary justice: a research framework. Earth Syst Governance. 6:100049. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2020.100049.

- BMU. 2020. Naturbewusstsein 2019. Bevölkerungsumfrage Zu Natur Und Biologischer Vielfalt. https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/naturbewusstsein_2019_bf.pdf

- Bodén L. 2015. The presence of school absenteeism: exploring methodologies for researching the material-discursive practice of school absence registration. Cult Stud ↔ Crit Methodol. 15(3):192–202. doi:10.1177/1532708614557325.

- Böhme J, Walsh Z, Wamsler C. 2022. Sustainable lifestyles: towards a relational approach. Sustainability Sci. 17(5):2063–2076. doi:10.1007/s11625-022-01117-y.

- Boström M. 2020. The social life of mass and excess consumption. Environ Sociol. 6(3):268–278. doi:10.1080/23251042.2020.1755001.

- Brand U, Muraca B, Pineault É, Sahakian M, Schaffartzik A, Novy A, Streissler C, Haberl H, Asara V, Dietz K, et al. 2021a. From planetary to societal boundaries: an argument for collectively defined self-limitation. Sustainability. 17(1):265–292. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.1940754.

- Brandt M 2020. Fleischverzicht ist in Deutschland immer noch die Ausnahme. https://de.statista.com/infografik/23079/umfrage-zu-vegetarischer-veganer-ernaehrung/

- Brand U, Wissen M, King ZM. 2021b. The imperial mode of living: everyday life and the ecological crisis of capitalism. Brooklyn: Verso Books.

- Bush A 2014. Spaces of resonance–towards a complex adaptive systems-based theory of action for sustainability. 338542 Bytes. 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.816955

- Chan KM, Gould RK, Pascual U. 2018. Editorial overview: relational values: what are they, and what’s the fuss about? Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 35:A1–7. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.11.003.

- Chapin FS, Power ME, Pickett STA, Freitag A, Reynolds JA, Jackson RB, Lodge DM, Duke C, Collins SL, Power AG, et al. 2011. Earth stewardship: science for action to sustain the human-earth system. Ecosphere. 2(8):art89. doi:10.1890/ES11-00166.1.

- Chapin FS, Weber EU, Bennett EM, Biggs R, van den Bergh J, Adger WN, Crépin A-S, Polasky S, Folke C, Scheffer M, et al. 2022. Earth stewardship: shaping a sustainable future through interacting policy and norm shifts. Ambio. 51(9):1907–1920. doi:10.1007/s13280-022-01721-3.

- Clayton S. 2020. Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J Anxiety Disord. 74:102263. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263.

- Cooke B, West S, Boonstra WJ. 2016. Dwelling in the biosphere: exploring an embodied human–environment connection in resilience thinking. Sustainability Sci. 11(5):831–843. doi:10.1007/s11625-016-0367-3.

- Darnhofer I. 2021. Farming resilience: from maintaining states towards shaping transformative change processes. Sustainability. 13(6):3387. doi:10.3390/su13063387.

- de Groot WT. 1992. Environmental science theory: concepts and methods in a one-world, problem-oriented paradigm. Elsevier. http://www.123library.org/book_details/?id=41106

- de Groot M, Drenthen M, de Groot WT, Center for Environmental Philosophy, The University of North Texas. 2011. Public visions of the human/nature relationship and their implications for environmental ethics. Environ Ethics. 33(1):25–44. doi:10.5840/enviroethics20113314.

- Destatis. 2020. Weiteres Rekordjahr: 124,4 Millionen Fluggäste starteten 2019 von deutschen Flug. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2020/02/PD20_050_464.html

- Dunlap A, Laratte L. 2022. European Green Deal necropolitics: exploring ‘green’ energy transition, degrowth & infrastructural colonization. Polit Geogr. 97:102640. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102640.

- Eckstein D, Künzel V, Schäfer L, Winges M. 2020. Global climate risk index. Who suffers most from extreme weather events? Weather-related loss events in 2018 and 1999 to 2018. Germanwatch e.V.

- Enqvist PJ, West S, Masterson VA, Haider LJ, Svedin U, Tengö M. 2018. Stewardship as a boundary object for sustainability research: linking care, knowledge and agency. Landsc Urban Plan. 179:17–37. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.005.

- European Economic and Social Committee. 2020. Towards an EU charter of the fundamental rights of nature. https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-03-20-586-en-n.pdf

- Fazey I, Schäpke N, Caniglia G, Hodgson A, Kendrick I, Lyon C, Page G, Patterson J, Riedy C, Strasser T, et al. 2020. Transforming knowledge systems for life on Earth: Visions of future systems and how to get there. Energy Research & Social Science. 70:101724. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101724.

- Federal Environment Agency. 2021. Mobilität privater Haushalte. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/private-haushalte-konsum/mobilitaet-privater-haushalte#-hoher-motorisierungsgrad

- Fisher A. 2019. Ecopsychology as decolonial praxis. Ecopsychology. 11(3):145–155. doi:10.1089/eco.2019.0008.

- Fiske ST. 2009. From dehumanization and objectification to rehumanization: neuroimaging studies on the building blocks of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1167(1):31–34. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04544.x.

- Flint CG, Kunze I, Muhar A, Yoshida Y, Penker M. 2013. Exploring empirical typologies of human–nature relationships and linkages to the ecosystem services concept. Landsc Urban Plan. 120:208–217. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.09.002.

- Folke C, Jansson Å, Rockström J, Olsson P, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Crépin A-S, Daily G, Danell K, Ebbesson J, et al. 2011. Reconnecting to the biosphere. AMBIO. 40(7):719. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0184-y.

- Folke C, Polasky S, Rockström J, Galaz V, Westley F, Lamont M, Scheffer M, Österblom H, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, et al. 2021. Our future in the Anthropocene biosphere. Ambio. 50(4):834–869. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01544-8.

- Fuchs A. 2020. Resonance: a normative category or figure of uncertainty? On reading Hartmut Rosa with Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. J Political Power. 13(3):1–13. doi:10.1080/2158379X.2020.1828756.

- Fulfer F. 2013. The capabilities approach to justice and the flourishing of nonsentient life. Ethics Environ. 18(1):19. doi:10.2979/ethicsenviro.18.1.19.

- Gagné J, Krause L-K. 2021. Einend oder spaltend? Klimaschutz und gesellschaftlicher Zusammenhalt in Deutschland. More in Common e. V.

- Hall DM, Feldpausch-Parker A, Peterson TR, Stephens JC, Wilson EJ. 2017. Social-ecological system resonance: a theoretical framework for brokering sustainable solutions. Sustainability Sci. 12(3):381–392. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0424-6.

- Hay R. 2005. Becoming ecosynchronous, part 1. The root causes of our unsustainable way of life. Sustain Dev. 13(5):311–325. doi:10.1002/sd.256.

- Hertz T, Mancilla Garcia M, Schlüter M, Muraca B. 2020. From nouns to verbs: how process ontologies enhance our understanding of social‐ecological systems understood as complex adaptive systems. People Nat. 2(2):328–338. doi:10.1002/pan3.10079.

- Ingold T. 2011. The perception of the environment: essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- IPCC. 2021. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. contribution of Working Group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

- Ivanova D, Barrett J, Wiedenhofer D, Macura B, Callaghan M, Creutzig F. 2020. Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environ Res Lett. 15(9):093001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab8589.

- Ives CD, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H, Dorninger C, Klaniecki K, Fischer J. 2018. Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustainability Sci. 13(5):1389–1397. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9.

- Ives CD, Freeth R, Fischer J. 2020. Inside-out sustainability: the neglect of inner worlds. Ambio. 49(1):208–217. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01187-w.

- Jax K, Calestani M, Chan KM, Eser U, Keune H, Muraca B, O’Brien L, Potthast T, Voget-Kleschin L, Wittmer H. 2018. Caring for nature matters: a relational approach for understanding nature’s contributions to human well-being. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 35:22–29. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.009.

- Kaaronen RO, Rietveld E. 2021. Practical lessons for creating affordance-based interventions for sustainable behavior change. One Earth. 4(10):1412–1424. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2021.09.013.

- Kealiikanakaoleohaililani K, Giardina CP. 2016. Embracing the sacred: an indigenous framework for tomorrow’s sustainability science. Sustainability Sci. 11(1):57–67. doi:10.1007/s11625-015-0343-3.

- Kidner D 2001. Nature and psyche: radical environmentalism and the politics of subjectivity. New York, NY: SUNY.

- Kissinger M, Rees WE, Timmer V 2011. Interregional sustainability: Governance and policy in an ecologically interdependent world. Environmental Science & Policy. 14(8):965–976.

- Kohler F, Holland TG, Kotiaho JS, Desrousseaux M, Potts MD. 2019. Embracing diverse worldviews to share planet Earth. Conserv Biol. 33(5):1014–1022. doi:10.1111/cobi.13304.

- Kueffer C, Schneider F, Wiesmann U. 2019. Addressing sustainability challenges with a broader concept of systems, target, and transformation knowledge. GAIA - Ecological Perspect Sci Soc. 28(4):386–388. doi:10.14512/gaia.28.4.12.

- Kuntz AM, Presnall MM. 2012. Wandering the tactical: from interview to intraview. Qual In. 18(9):732–744. doi:10.1177/1077800412453016.

- Landmann H. 2020. Emotions in the context of environmental protection: theoretical considerations concerning emotion types, eliciting processes, and affect. Umweltpsychologie. 24(2):61–73.

- Lessenich S. 2019. Living well at others’ expense: the hidden costs of western prosperity. Medford, MA: Polity.

- Leventon J, Duşe IA, Horcea-Milcu A-I. 2021. Leveraging biodiversity action from plural values: transformations of governance systems. Front Ecol Evol. 9:609853. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.609853.

- Linder N, Giusti M, Samuelsson K, Barthel S. 2021. Pro-environmental habits: an underexplored research agenda in sustainability science. Ambio. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01619-6.

- Macy J, Brown MY. 2014. Coming back to life: the updated guide to the work that reconnects. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

- Maller C. 2018. Healthy urban environments: more-than-human theories. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, Earthscan from Routledge.

- Martin J-L, Maris V, Simberloff DS. 2016. The need to respect nature and its limits challenges society and conservation science. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 113(22):6105–6112. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525003113.

- Masquelier C. 2020. Book review: Hartmut Rosa, resonance: a sociology of our relationship to the world. Sociology. 54(4):858–860. doi:10.1177/0038038519899344.

- Massumi B. 2002. Parables for the virtual: movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822383574.

- McCormack DP. 2003. An event of geographical ethics in spaces of affect. Trans Inst Brit Geogr. 28(4):488–507. doi:10.1111/j.0020-2754.2003.00106.x.

- McKenzie FC, Williams J. 2015. Sustainable food production: constraints, challenges and choices by 2050. Food Sec. 7(2):221–233. doi:10.1007/s12571-015-0441-1.

- McMillen HL, Campbell LK, Svendsen ES, Kealiikanakaoleohaililani K, Francisco KS, Giardina CP. 2020. Biocultural stewardship, Indigenous and local ecological knowledge, and the urban crucible. Ecol Soc. 25(2):art9. doi:10.5751/ES-11386-250209.

- McPhearson T, Iwaniec DM, Bai X. 2016. Positive visions for guiding urban transformations toward sustainable futures. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 22:33–40. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.004.

- McPhearson T, Raymond M, Gulsrud C, Albert N, Coles C, Fagerholm N, Nagatsu N, Olafsson M, S. A, Soininen N, et al. 2021. Radical changes are needed for transformations to a good Anthropocene. Npj Urban Sustainability. 1(1):5. doi:10.1038/s42949-021-00017-x.

- Meadows D. 1999. Leverage points: places to intervene in a system. Hartland: The Sustainability Institute.

- Meyer JM. 2015. Engaging the everyday: environmental social criticism and the resonance dilemma. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

- Muhar A, Böck K. 2018. Mastery over nature as a paradox: societally implemented but individually rejected. J Environ Plann Manage. 61(5–6):994–1010. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1334633.

- Muradian R, Gómez-Baggethun E. 2021. Beyond ecosystem services and nature’s contributions: is it time to leave utilitarian environmentalism behind? Ecol Econ. 185:107038. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107038.

- Muradian R, Pascual U. 2018. A typology of elementary forms of human-nature relations: a contribution to the valuation debate. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 35:8–14. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.014.

- Newig J, Challies E, Cotta B, Lenschow A, Schilling-Vacaflor A. 2020. Governing global telecoupling toward environmental sustainability. Ecol Soc. 25(4):art21. doi:10.5751/ES-11844-250421.

- O’Brien K. 2018. Is the 1.5°C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 31:153–160. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.04.010.

- Palamos K 2016. Nature, human ecopsychological consciousness and the evolution of paradigm change in the face of current ecological crisis. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies. 35:2. doi:10.24972/ijts.2016.35.2.88.

- Parry GA. 2016. Ecopsychology: remembering the true source of our consciousness. Cosm Hist. 12(2):226–236.

- Peña AM. 2018. The politics of resonance: transnational sustainability governance in Argentina: sustainability governance in Argentina. Regul Gov. 12(1):150–170. doi:10.1111/rego.12111.

- Pianta M, Lucchese M. 2020. Rethinking the European Green Deal: an industrial policy for a just transition in Europe. Rev Radic Polit Econ. 52(4):633–641. doi:10.1177/0486613420938207.

- Plesa P. 2019. A theoretical foundation for ecopsychology: looking at ecofeminist epistemology. New Ideas Psychol. 52:18–25. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.10.002.

- Pohl C, Hirsch Hadorn G. 2007. Principles for designing transdisciplinary research. oekom verlag. doi:10.14512/9783962388638.

- Pope K, Bonatti M, Sieber S. 2021. The what, who and how of socio-ecological justice: Tailoring a new justice model for earth system law. Earth System Governance. 10:100124. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2021.100124.

- Raymond CM, Kaaronen R, Giusti M, Linder N, Barthel S. 2021. Engaging with the pragmatics of relational thinking, leverage points and transformations – reply to West et al. Ecosyst People. 17(1):1–5. doi:10.1080/26395916.2020.1867645.

- Reardon S. 2022. First pig-to-human heart transplant: what can scientists learn? Nature. 601(7893):305–306. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00111-9.

- Reser JP. 1995. Whither environmental psychology? The transpersonal ecopsychology crossroads. J Environ Psychol. 15(3):235–257. doi:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90006-3.

- Riechers M, Loos J, Balázsi Á, García-Llorente M, Bieling C, Burgos-Ayala A, Chakroun L, Mattijssen TJM, Muhr MM, Pérez-Ramírez I, et al. 2021. Key advantages of the leverage points perspective to shape human-nature relations. Ecosyst People. 17(1):205–214. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1912829.

- Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, Chapin FSI, Lambin E, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, et al. 2009. Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol Soc. 14(2):art32. doi:10.5751/ES-03180-140232.

- Rosa H. 2019. Resonance: a sociology of the relationship to the world. Medford, MA: Polity Press.

- Rosa H. 2020. Unverfügbarkeit. Medford, MA: Suhrkamp.

- Saar M. 2021. Power, affect, society: critical theory and the challenges of (Neo-)Spinozism. In: Fünfgeld H, Henning C, and Bueno A, editors. Critical theory and new materialisms. London: Routledge; p. 71–83.

- Scott D, Gössling S. 2021. From Djerba to Glasgow: have declarations on tourism and climate change brought us any closer to meaningful climate action? J Sustain Tourism. 1–24. doi:10.1080/09669582.2021.2009488.

- Seppelt R, Cumming GS. 2016. Humanity’s distance to nature: time for environmental austerity? Landsc Ecol. 31(8):1645–1651. doi:10.1007/s10980-016-0423-5.

- Shams Esfandabadi Z, Ranjbari M, Scagnelli S. 2022. The imbalance of food and biofuel markets amid Ukraine-Russia crisis: a systems thinking perspective. Biofuel Res J. 9(2):1640–1647. doi:10.18331/BRJ2022.9.2.5.

- Singh S, Kumar R, Panchal R, Tiwari MK. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on logistics systems and disruptions in food supply chain. Int J Prod Res. 59(7):1993–2008. doi:10.1080/00207543.2020.1792000.

- Snell TL, Simmonds JG, Webster RS. 2011. Spirituality in the work of Theodore Roszak: implications for contemporary ecopsychology. Ecopsychology. 3(2):105–113. doi:10.1089/eco.2010.0073.

- Snodgrass J, Tiedje K. 2008. Indigenous nature reverence and conservation: seven ways of transcending an unnecessary dichotomy. J Study Religion Nat Cult. 2(1):6–29. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v2i1.6.

- Softas-Nall S, Woody WD. 2017. The loss of human connection to nature: revitalizing selfhood and meaning in life through the ideas of Rollo May. Ecopsychology. 9(4):241–252. doi:10.1089/eco.2017.0020.

- Stammer D, Engels A, Marotzke J, Gresse E, Hedemann C, Petzold J (2021). Hamburg climate futures outlook: assessing the plausibility of deep decarbonization by 2050. Version 1/2021. Universität Hamburg. doi:10.25592/UHHFDM.9104

- Steffen W, Broadgate W, Deutsch L, Gaffney O, Ludwig C. 2015a. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: the great acceleration. Anthropocene Rev. 2(1):81–98. doi:10.1177/2053019614564785.

- Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockstrom J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, de Vries W, de Wit CA, et al. 2015b. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 347(6223):1259855. doi:10.1126/science.1259855.

- Stephens A, Taket A, Gagliano M. 2019. Ecological justice for nature in critical systems thinking: ecological justice for nature. Syst Res Behav Sci. 36(1):3–19. doi:10.1002/sres.2532.

- St. Pierre EA. 2021. Why post qualitative inquiry? Qual In. 27(2):163–166. doi:10.1177/1077800420931142.

- Susen S. 2020. The resonance of resonance: critical theory as a sociology of world-relations? Int J Polit Cult Soc. 33(3):309–344. doi:10.1007/s10767-019-9313-6.

- Thoburn N. 2007. Patterns of production: cultural studies after hegemony. Theory Cult Soc. 24(3):79–94. doi:10.1177/0263276407075959.

- Treves A, Santiago-Ávila FJ, Lynn WS 2019. Just preservation. Animal Sentience. 4(27). doi:10.51291/2377-7478.1505.

- Vogel C, O’Brien K. 2021. Getting to the heart of transformation. Sustainability Sci. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-01016-8.

- Walsh Z, Böhme J, Wamsler C. 2020. Towards a relational paradigm in sustainability research, practice, andeducation. Ambio. doi:10.1007/s13280-020-01322-y.

- Wamsler C, Bristow J 2022. At the intersection of mind and climate change: integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice. Clim Change. 173(7). doi:10.1007/s10584-022-03398-9.

- Wamsler C, Brossmann J, Hendersson H, Kristjansdottir R, McDonald C, Scarampi P. 2018. Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustainability Sci. 13(1):143–162. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0428-2.

- Wamsler C, Osberg G, Osika W, Herndersson H, Mundaca L. 2021. Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: towards a new research and policy agenda. Global Environ Change. 71:102373. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102373.

- Wamsler C, Schäpke N, Fraude C, Stasiak D, Bruhn T, Lawrence M, Schroeder H, Mundaca L (2020). Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environmental Science & Policy, 112, 227–235. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.005

- Warber SL, Irvine KN, Quinn BF, Hansen AL, Hypki C, Sims E. 2020. Methods for integrating transdisciplinary teams in support of reciprocal healing: a case study. Ecopsychology. 12(3):222–230. doi:10.1089/eco.2020.0008.

- Weder F, Voci D. 2021. From ignorance to resonance: analysis of the transformative potential of dissensus and agonistic deliberation in sustainability communication. Int J Commun. 15:163–186.

- Welzer H. 2011. Mental infrastructures how growth entered the world and our souls.

- Werner A, Risius A. 2021. Motives, mentalities and dietary change: an exploration of the factors that drive and sustain alternative dietary lifestyles. Appetite. 165:105425. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2021.105425.

- West S, Haider LJ, Stålhammar S, Woroniecki S. 2020. A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst People. 16(1):304–325. doi:10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417.

- Wilson EO. 1984. Biophilia: the human bond with other species. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Woiwode C, Schäpke N, Bina O, Veciana S, Kunze I, Parodi O, Schweizer-Ries P, Wamsler C. 2021. Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustainability Sci. 16(3):841–858. doi:10.1007/s11625-020-00882-y.

- Wu J, Eaton PW, Robinson-Morris DW, Wallace MFG, Han S. 2018. Perturbing possibilities in the postqualitative turn: lessons from Taoism and Ubuntu. Int J Qual Studies Educ. 31(6):504–519. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1422289.

- Zarraga A. 2021. The Earth is speaking: she tells us we have no more time. Global Witness Blog. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/blog/earth-speaking-she-tells-us-we-have-no-more-time/