ABSTRACT

The human impact on nature has now reached a level at which the well-being of future human society is at risk. Therefore, transformative change in society is needed. Environmental assessments contribute to shaping environmental policy, potentially leveraging transformative change. Red Lists are a key information source on the state of biodiversity. Our aim was to study the Red List authors’ perceptions of how Red Lists contribute to leveraging sustainability changes. We interviewed 15 of the authors of the forest and peatland sections of the Finnish Red List of Ecosystems 2018. We used the framework of sustainability leverage points to locate sustainability changes that Red Lists have leveraged in the social part of the Finnish social-ecological system. Our results show how the assessors perceived the influence of the Red Lists at most of the leverage points, including the deepest ones, and how these influences simultaneously co-exist in several leverage points. The most prominent sustainability changes were linked with legislation and information flows, whereas current paradigms, system goals and legislation appeared to prevent Red Lists from leveraging sustainability changes in Finland. We conclude that the production and dissemination processes of Red List knowledge can make an important contribution to sustainability changes.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

No country in the world has succeeded in providing welfare for its citizens without transgressing the biophysical boundaries of sustainability (O’Neill et al. Citation2018). The actions of current society deteriorate biodiversity, challenge the living conditions for humanity and predicate that achieving sustainability goals for 2030 and beyond requires transformative change (IPBES Citation2019). The global community has committed to halting biodiversity loss (Convention on Biological Diversity Citation1992) and has agreed that transformative change, ‘a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values’, is needed (IPBES Citation2019). The current speed of loss makes finding political solutions to conserve biodiversity critical. Could environmental assessments contribute to changing these trajectories?

Science-based knowledge of the decline of biodiversity keeps accumulating, and different biodiversity measures report on the ongoing sixth mass extinction (Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 Citation2020). However, it is not possible to measure all biodiversity (Mora et al. Citation2011). Therefore, various ways of assessing the state of biodiversity have been developed. The Red List of Threatened Species and the Red List of Ecosystems (we refer to both of these and their different versions with the ‘Red List’), developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), are one of the most comprehensive sources of knowledge for measuring the state of biodiversity. Thanks to the Red Lists, we know which ecosystems are threatened in more than 100 countries (Bland et al. Citation2019). Abundant knowledge exists on the mechanisms and drivers of biodiversity loss as well as potential solutions for halting the loss (GBO−5 2020). Food production, forestry and urban development are behind population declines of the majority of the Red-Listed species (Maxwell et al. Citation2016), and 75% of the planet’s surface is under substantial human influence (Venter et al. Citation2016). However, many solutions are not possible without deep transformative change in society (IPBES Citation2019). For example, Otero et al. (Citation2020) challenge the economic growth paradigm as incompatible with halting biodiversity loss.

Here, we study the influence of the Red Lists, considering that science and society are co-created. Knowledge is a product and is constitutive of society; science shapes society, but society also shapes science. For example, framing and measuring environmental problems have effects on how they are governed (Lidskog Citation2014). Red Lists impact society, not just environmental policy, in multiple ways. The Red Lists work as indicators of the state of nature, which can be used strategically to connect and disconnect science and policy (Rabaud et al. Citation2020). The Red Lists have been attributed a role in enhancing the perception of biodiversity loss as a severe global environmental problem (Lidskog Citation2014). In addition, IUCN has a role in leading the adoption of policies, analyses and norms of the conservation community worldwide (Stuart et al. Citation2017). The Red Lists of Ecosystems have been used to guide national legislation, land-use planning, monitoring and land management (Bland et al. Citation2019).

Our study case is on the Finnish Red Lists of Ecosystems. In Finland, societal discourse relating to the vulnerability of species and ecosystems can be traced back to the making of Red Lists (altogether, there have been eight assessments since the 1980s) that have defined and publicised the concepts of vulnerable and endangered species and ecosystems, even though the public may be unaware of this background. Thus, Red Lists are heavily involved in creating societal weight for conserving nature. The list of vulnerable species in the appendix of the Finnish Nature Conservation Decree has been taken nearly directly from the Red List of Species 2010 and updated based on the 2019 evaluation (Ministry of Environment and Finnish Environment Institute Citation2021). Red Lists, however, are only one part of the process preceded and followed by, as well as coincidental to, numerous other products and processes concerning nature conservation and sustainability.

The implications of the Red Lists for leveraging sustainability, as far as we know, have not been studied before. We focus on Red List assessors, who are well-placed to follow the use and production of the Red Lists. We used Meadows’ (Citation1999) sustainability leverage points to analyse places or ways in which the Red Lists have and could leverage changes. We study how the Red Lists of Ecosystems have leveraged sustainability changes by qualitatively analysing interviews with authors of the forest and peatland sections of the Finnish Red List of Ecosystems 2018 (Kontula and Raunio Citation2019).

2. Analytical framework

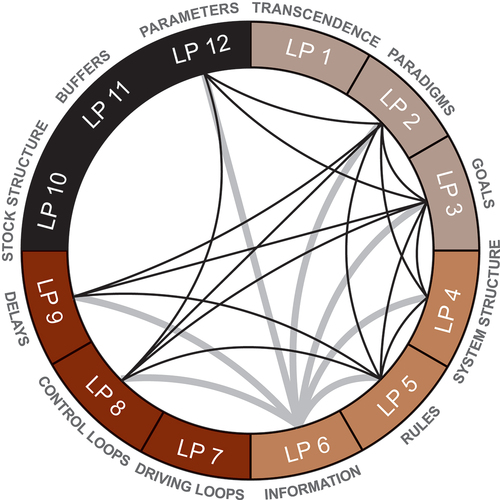

The context for our article is necessary system-wide transformative change or sustainability transformation, which is multi-sectoral, future oriented and unprecedented in its magnitude. However, there are no clear criteria for measuring such change (Salomaa and Juhola Citation2020). Studying past events and multiple smaller sustainability changes can enlighten how environmental assessments contribute to systemic changes. In the analysis we focus on these sustainability changes. We have chosen to use Meadows’ (Citation1999) leverage points (LPs) as an analytical lens () because they describe places or ways to change the whole system.

Table 1. Meadows’ (Citation1999) conceptual framework of leverage points for sustainability and practical examples of it in social-ecological system. In parenthesis short versions for the leverage points that are used in further figures. In the analysis we focused on the social part of the social-ecological system, therefore the examples relating to the ecological part are italicised.

The leverage points framework consists of 12 leverage points that are places or ways to intervene in which a small change may lead to large changes in the system as a whole. The deepest, most powerful leverage points are in changing paradigms and system goals. Deeper leverage points (smaller numbers), representing the intent and design of the system, determine what interventions are possible at the shallower end (bigger numbers) (Abson et al. Citation2017). The shallowest leverage points seldom change behaviour in significant and long-lasting ways, although interventions at these levels often play a critical role in practical and immediate contexts. Still, adjustments to shallow leverage points may ultimately alter the deepest ones, and such interactions are understudied (Abson et al. Citation2017; Dorninger et al. Citation2020). Meadows (Citation1999) underlined that leverage points are based on reasoning and work in progress. Thus, their order is open to discussion and can vary. Others have found Meadows’ framework both suitable (e.g. Lidgren et al. Citation2006; Manlosa et al. Citation2019; Dorninger et al. Citation2020; Rosengren et al. Citation2020; Davila et al. Citation2021; Fischer et al. Citation2022) and not ideal (Chan et al. Citation2020) for various analyses of transformations towards sustainability.

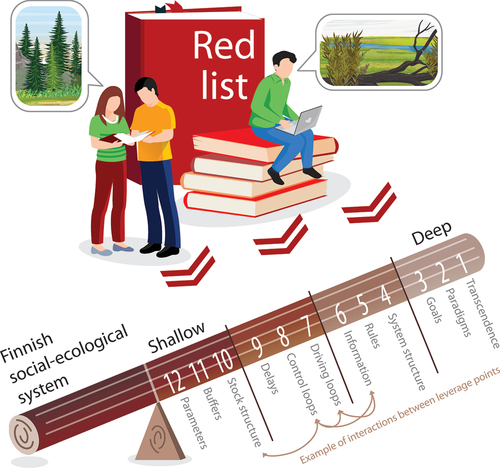

Red Lists and society affect each other in intertwined processes to potentially leverage sustainability (Lidskog Citation2014; Stuart et al. Citation2017; Bland et al. Citation2019; Rabaud et al. Citation2020). We used Meadows’ leverage points framework () to examine how the Red Lists reach different leverage points. illustrates our analytical framework.

Figure 1. Analytical framework: the assessors’ perceptions of how the forest and peatland sections of the Red Lists of Ecosystems leverage sustainability changes in the Finnish social-ecological system. The bidirectional arrows represent an example of potential interactions between leverage points that we studied through co-codings. Full names of leverage points are given in .

The heterogeneous use of the leverage points framework highlights the importance of reflecting upon the central concepts of the study, such as what the system is (Leventon et al. (Citation2021). Herein, the examined system was the Finnish social-ecological system. In the analysis, we focused on the social part of the social-ecological system (recognising that this concept is only one way to see the world) to better address the deepest leverage points, but acknowledging that the Red Lists are inherently ecological assessments and more likely to influence ecological part of the system at shallower leverage points. Even though we focus on the social part in the analysis, we briefly discuss the ecological part of the system in the overview of results and return to the impacts on the wider social-ecological system in the Discussion section. Much of the earlier leverage point research concerns place-based social-ecological systems (e.g. Fischer et al. Citation2022). In our case, the Red Lists can be seen as a part of the social system; at the same time, it is a part of the knowledge sub-system.

3. Materials and methods

3.1 Context: Red Lists and Finnish assessors, and forest and peatland ecosystems

The primary goal of the Red Lists of Ecosystems is to assess the risks of ecosystem collapse (Keith et al. Citation2015). The assessments are based on standardised, systematic criteria, aim to be objective, transparent and reproducible (Mace et al. Citation2008), are characterised by a massive network of contributing authors and use of extensive data sources. In addition to the global Red Lists, there are regional and national lists. Red Lists thus officially aim to produce objective knowledge. However, as their names imply, they seem to be developed to increase interest and spark feelings of an emergency.

The threat status of ecosystems has been evaluated twice in Finland, in a pioneering national effort in 2008, and in 2018, following the IUCN standards that had been published three years earlier (Bland et al. Citation2015). The latter assessment was exceptionally broad, covering all the main groups of habitat (ecosystem) types, further subdivided into 388 distinct habitat types covering the whole country, apart from heavily human-modified environments (Kontula and Raunio Citation2019). The second assessment was produced between 2016–2018. The process was steered and funded by the Ministry of the Environment and coordinated by the Finnish Environment Institute. The Ministry of Environment is responsible for legislative and policy preparation for the government and parliament concerning biodiversity and environmental protection. There were 120 experts from several research institutions, universities and public authorities (Appendix 1) who took part in eight assessor groups, among which we focused on peatland and forest ecosystems. The Red Lists of Ecosystems are available on the internet, and these written reports consist of a general part that explains the method and summarises the results, and a second part that describes the habitats, their spatial distributions at a coarse level and their threat classification with associated justifications.

The second Red List’s evaluations were based on changes in habitat area and quality over the last 50 years and since the preindustrial era (ca. 1750s). Data sources varied from remote-sensing data to detailed inventories of specific habitat types, but assessment decisions in many cases ultimately relied on expert opinion. Habitat types were classified as data deficient, least concern, near threatened, vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered; the latter three comprise threatened habitats. Apart from the actual threat status, the assessment contains information on current trends (improving, stable or deteriorating) as well as predictions of future changes for each habitat type. Based on the results, the author groups proposed recommendations for actions to improve the status of the threatened habitat types.

Forest and peatland (also called mire) are two key Finnish land ecosystems based on area coverage and socio-political context. These habitat types cover most of the land ecosystems in Finland (Kontula and Raunio Citation2019). They appear as an intertwined mosaic in the landscape, and actions in one affect the other. Despite their commonness, forests have the second-largest share of habitat types classified as threatened (76% out of 34 habitat types assessed), preceded only by semi-natural grasslands (Kontula and Raunio Citation2019). Of the 69 peatland habitat types assessed, 57% were classified as threatened (Kontula and Raunio Citation2019). Forests and peatlands are mainly threatened by the overexploitation of natural resources, with forestry practices affecting both. Over half of all peatlands have been drained to improve forestry productivity, while others have been cleared for agriculture and peat extraction (Turunen Citation2008). Because of the long history and economic, social and cultural importance of the utilisation of these habitat types, conservation of both forests and peatlands is highly politicised (Kröger and Raitio Citation2017; Salomaa et al. Citation2018).

We studied perceptions of the Red List assessors, which means that there are some surmountable uncertainties as to whether sustainability changes are actually taking place. The assessors have critical positions in the conservation science-policy interface, given that Finland has a small group of central actors. We intentionally chose to interview only knowledge producers, and despite their perceptions on the impact of knowledge may be incomplete we believe that the perceptions of the interviewees regarding past events reflect events of reality. In addition to being Red List assessors, the assessors have different roles in society, including at universities and in various societies and interacting with politicians. They encounter and work with different stakeholder groups regarding the habitats in which they have expertise.

3.2 Interview data and analysis

Salomaa conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 Red List assessors: 8 out of 16 active members of the peatland author group, 5 out of 15 members of the forest author group and 2 interviewees outside these groups who had knowledge on the coordination of the Red Lists. Invitations were first sent via the groups’ secretaries, and then reminder(s) were sent directly to the assessors’ email addresses. The interviews covered multiple broad themes surrounding the Red Lists, including successfulness and use of Red Lists, transformative change and the potential role of Red Lists in it (see interview guide in Appendix 2). We did not directly ask about specific leverage points, except regarding LP6 (i.e. information producers, use, users, society’s view of nature knowledge and the assessor’s own role in disseminating knowledge). The questions concentrated more on the impacts of the Red Lists to society than vice versa, but the latter was directly asked with a specific example related to recent events. Questions regarding Red Lists were oriented both to the past and the future. We provided a definition of transformative change (sustainability transformation), but did not introduce Meadows’ framework. Interviews were conducted between March and June 2019, relatively soon after the publication of the Red List of Ecosystems in December 2018. They lasted from 39 to 87 minutes (average 56 minutes). The interviews were conducted in the interviewee’s office or home office, on the university premises or by phone. The interviews were conducted in Finnish, recorded and transcribed. Arponen was a supplementary member of the steering group for the Assessment of threatened habitat types in Finland, 2016–2018, which deepened the understanding of the study context. Arponen was not paid for this work.

We analysed the data using qualitative content analysis. First, we derived a general background for a more detailed analysis by summarising answers whether the Red Lists could impact transformative change. It was sometimes difficult to know whether interviewees were talking about the Red Lists of Threatened Species, Red Lists of Ecosystems, or a certain version of them, as many of them have been involved with several assessments.

We used leverage points as the initial codes in the first round of coding, which corresponds to directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). This coding was done using Atlas.ti. We used Meadows (Citation1999) operational definitions for how to apply each leverage point to the social part of the system in qualitative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). We also took guidance for our coding from previous studies that used Meadow’s framework as a starting point for qualitative coding (Lidgren et al. Citation2006; Carey and Crammond Citation2015). We did not assess the strength of impact on leveraging sustainability but coded fitting sections equally on leverage points in this first round. In the examination of the Red Lists, LP6 is self-evidently central. According to Abson et al. (Citation2017; referring also to Berkes Citation2009), the way that knowledge is created, shared and utilised in society influences transformation processes and has the potential to influence all leverage points. Even though the Red Lists can be undeniably classified as knowledge, we were interested in their wider contribution to change and did not focus only on LP6.

We delimited our analysis to system-level changes and excluded the individual level (regarding mainly LP1: The power to transcend paradigms). All Red List-related results could have been coded under LP8: The Strength of negative feedback loops, because Meadows (Citation1999) listed monitoring systems on environmental damage there and Red Lists could be seen as monitoring systems, but we chose not to because it would not have been informative for our analysis. In the second round of coding, we re-coded all sections relating to the Red Lists manually and condensed their content. We excluded the text on leverage points within the ecological system only (nature as biological stock, and hence, the ultimate impacts on ecosystem health, population sizes etc., spanning LP7–12). Third, we condensed the texts and grouped them into themes within each leverage point inductively. When condensing the data, we described variations between interviewees when variations were prominent, whereas on other occasions, we described the dominant content. Then, we summarised the main content of a theme into a representative subheading. While writing the results section, we identified overlapping codings under different leverage points, or where the content was otherwise suitable for other leverage points, and marked these as co-codings.

Then, we classified themes into three categories based on our interpretation of whether the condensed data showed 1) to have leveraged sustainability changes, 2) to have failed to leverage sustainability changes or even prevented them or 3) if the effect was ambiguous. Here, we defined a change to be large enough if Red Lists had changed how the social part of the system worked (Meadows Citation1999). Some of these main themes are joint between multiple leverage points, meaning that there were so many co-codings or a lack of specification that it was impossible to separate the content based on leverage points.

In the Results section, we present the results for each leverage point, indicating co-codings with other leverage points in parentheses and in . Even though co-coding does not directly demonstrate an interaction between leverage points, we view co-existence as notable because it shows potential interaction. If the whole theme was co-coded with another leverage point, we state this in parentheses in the first sentence after the subtitle. If a leverage point number is listed in a sentence, only that part of the results was co-coded with the leverage point. Those marked with ‘see also’ co-exist in more indirect ways, for example, when we linked the results with the original meaning of leverage points as coined by Meadows. LP6 co-exists with all leverage points for which we had results. LP1, LP7, LP10 and LP11 had fewer than three coded text parts each, so these were not included for further analysis.

4. Results

4.1 Overview of the perceptions of Red Lists’ impact on transformative change

Interviewees saw Red Lists as one factor potentially causing transformative change, especially by providing evidence of the unsustainability of the current lifestyles. Notably, one interviewee explained that conclusions relating to the need for transformative change were halted by the employer; these were not commissioned in the assessment. The interviewees felt Red Lists had advanced conservation of peatlands and forests, and the adoption of the concept of threatened ecosystems, as well as increased the general knowledge base. In particular, interviewees perceived Red Lists as a central knowledge base for land-use planning: Red Lists’ recommendations can affect natural resource use by altering detrimental actions in specific habitats, or lead to considering larger area assemblages in planning. This fresh knowledge can be used by governments, affect decisions through experts, cause changes in legislation, increase worry about the state of biodiversity and change voting behaviour. They said it could help recognise trade-offs between biodiversity and climate solutions and advance the development of new practices in forestry and agriculture. In general, the change caused by the Red Lists was not perceived as fully transformative because, for example, legislation is still sectoral and harmful subsidies are a magnitude greater than conservation funding.

4.2 Perceptions of changes at leverage points

4.2.1 Red Lists have leveraged and failed to leverage change

Our analysis showed that Red Lists have leveraged sustainability changes at LP5: The rules of the system and LP6: The structure of information flows. They have failed to leverage sustainability changes at LP2: The mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises, LP3: The goals of the system and LP5: The rules of the system. summarises the main results. Next, we elaborate on the most prominent themes highlighted in (other themes can be found in Appendix 3). There were numerous co-codings and other co-existence of leverage points (), which are also marked in the text.

Table 2. Main findings of the Red Lists leveraging change, identified at the level of each leverage point by Meadows (Citation1999). Full names of leverage points are given in . All the themes are also linked to LP6, even though they are not marked in the Table. The most prominent themes are in bolded italics. (Data regarding ecological system only were excluded from the analysis.).

4.2.2 Economy-driven paradigms and goals dominate

This is a joint theme between LP2 and LP3 (theme co-coded with LP6; see also LP5). This theme shows that the Red Lists have failed to leverage sustainability changes, at least partly because paradigms and system goals are dominated by economy-driven ones. In other words, the paradigm of using nature is stronger than saving it (co-coded with LP12; see also LP8 and LP4). Paradigms and goals vary between different groups. These groups see the use value of the Red Lists differently, as illustrated by the following quote.

Environmental authorities and non-governmental organisations, they see this [the Red List] apparently as useful, and there can be some people with no particular stance on it –. And then it is detrimental to those building pulp mills and wanting to increase the use of wood and to politicians and stakeholders representing certain aims. (I4_forest)(LP2 and LP3; co-coded with LP6; see also LP5)

Interviewees articulated many concerns related to economics. For example, companies are unwilling to make costly changes without a global shift in practices. The environmental administration is underfunded, for both conservation and creation of the Red Lists (LP12; see also LP8). Attractiveness and structure of incentive systems, cost-efficiency as a criterion for prioritising conservation actions, and the costliness of fieldwork were also discussed. Nonetheless, some interviewees claimed that the forestry sector and peat industry, the main users of the focus ecosystems, took the results of the Red Lists seriously. Red Lists, as sources of new information, have the potential to increase awareness, wake people up to the changes in ecosystems and alter paradigms and goals.

4.2.3 The Red Lists have affected rules

This theme concerns LP5 (theme co-coded with LP6). The Red Lists have caused changes in the Forest Act and the Environmental Protection Act, several national conservation programmes and strategies and management recommendations. Both the Red Lists’ making processes and their recommendations have had an impact on rules (see also LP9), however the interviewees’ perceptions of the strength of the impact varied.

Importantly, interviewees described that the Environmental Protection Act now grants peat extraction permits only when nationally or locally significant nature values are not destroyed due to the making of the first Red List on peatlands. The key recommendation to direct extractive use to altered peatlands was written in the National Peatland Strategy, which was later used in the creation of the Environmental Protection Act. In addition, interviewees illustrated that the threatened ecosystem concept has been used in legal decisions as a part of the overall considerations, for example, of peat extraction permits, even before the latest changes in legislation. An example of an impact mechanism from the Red List to legislation was given by an assessor who had participated in producing recommendations for the development of the legislation.

Directly after the first Red List of Ecosystems, we did a separate publication – where we gave very tangible guidelines on how the Forest Act, or the Nature Conservation Act or the Water Act should be developed in order to improve the status of ecosystems I6_peatland. (LP5, co-coded with LP6; see also LP3 and LP4)

The most noted strategies that were affected by the Red Lists were the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, the National Peatland Strategy, the Proposal of the Mire Conservation Group for Supplemental Mire Conservation and their follow-ups. The impact of the Red List is visible, for example, in the selection of sites in the Proposal for Supplemental Mire Conservation. Likewise, interviewees described that management recommendations, such as forestry guidelines on state land and certification schemes, were affected by the Red Lists but these recommendations might not always be followed.

The Red Lists are used in the implementation of planning, for example, in land-use planning, environmental impact assessments and Natura 2000 appropriate assessments. For example, the Red Lists of Ecosystems have contributed to improved quality of nature surveys for land-use planning. In general, threat status was seen as an important tool for prioritising conservation, restoration and other land uses.

4.2.4 Gaps remain in the rules

This theme concerns LP5 (theme co-coded with LP6). Red Lists have failed to leverage sustainability changes because the rules do not comprehensively protect ecosystems. The legislation is sectoral and the Red Listing does not protect ecosystems from harmful development. The potential legislation for ecological compensation was seen as a possible partial solution to improve consideration of nature (LP8; see also LP2 and LP3). Notably, some interviewees argued that legislation does not protect ecosystems systematically for political reasons. Two interviewees explained that certain peatland ecosystems were not included in the Forest Act, possibly for political reasons (LP2 and LP3). In addition, one claimed that the definition of ‘habitats of special importance’ in the Forest Act, which designates these habitats as being small in area or having little significance for forestry purposes, has stemmed from economic interests (LP2 and LP3).

4.2.5 Knowledge has transferred to the public and decision making

This theme concerns LP6 (theme co-coded with LP4 and LP5). Red Lists have leveraged sustainability changes by becoming a new source of information for many different audiences. The people in environmental administration use the Red Lists as facts without making a fuss. There are several routes for the Red List knowledge to be used for administrative purposes: coordinated dissemination efforts, such as policy briefs, different proposals and parliamentary committee reports. Having the same people in different working groups enables brokering knowledge (see also LP3), as do meetings with NGOs and members of parliament. In addition, a couple of interviewees saw themselves as having a role in political discussions. However, the most impactful ways to influence decision making have been personal contact with various ministers, said an experienced interviewee. Also, the Red Lists have received visibility in the media, the second ecosystem assessment more so than the first, although some felt that the media’s attention span covered only the day of publication. Potentially thanks to Red Listing processes, biodiversity loss has been a general discussion topic, even in the latest elections (LP2 and LP3).

Perceptions of the Red Lists’ value to common people varied from people being indifferent to trusting that it was a good quality tool (LP2). Several interviewees stressed that Red Lists are meant for everybody. They explained that the second Red List of Ecosystems is colossal, 1300 pages, but the recommendations are simple and only a couple of pages long. Interviewees identified specific groups, such as scientists, decision makers, public authorities, ministries, lawmakers, those who have work responsibilities relating to nature, those who work with communities, land-use planners, regional organisations, consults, forest owners, Forest Centres and NGOs (LP4) as users of the information. Some summed up that the Red Lists are basically meant for a small group that is already educated on the topic, which especially concerns the recommendations. However, interviewees described that recommendations for action are at a general level and do not guide the decision maker on what to do; knowledge of alternative measures and policies, associated costs and detailed target features and spatial locations are needed (LP8).

4.2.6 Whether others than experts should participate in knowledge production was inconclusive

This theme concerns LP6 (theme co-coded with LP2 and LP3). This theme has ambiguous but potentially strong positive or negative effects on leveraging sustainability. It was agreed that research institutes, universities and the Finnish State Forest Organisation should participate in the Red Lists assessments. However, some mentioned several additional knowledge producers. Nature enthusiasts, who monitor nature as a hobby, were mostly welcomed and even said to be vital, although more so for species assessments than for ecosystems. Locals holding knowledge of the place and its history, NGOs, scientific societies, municipalities as well as those who do practical work in the environmental and natural resources sectors were also mentioned. The potential usefulness of citizen science was mentioned several times. However, one interviewee contradicted this by questioning the objectivity of nature enthusiasts and nature NGOs.

One interviewee pondered that comments could have been solicited from different stakeholder groups during the process, while another said that sometimes industry purposefully tries to mess things up. While some saw implementable recommendations, others were afraid that political interests would influence knowledge production, specifically in the forest sector (LP2). The forest sector strongly criticised the first Red List of Ecosystems, especially the transparency of expert evaluations.

… the results were even forbidden to be presented somewhere, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry objected to presenting them anywhere. (I5_forest) (LP6; see also LP2 and LP3)

Consequently, it was demanded that a member of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry be added to the Red List author group. They were later added along with a member of the Ministry of the Environment. In the end, they did not influence the outcome of the second Red List of Ecosystems, according to the interviewees. The interviewees pointed out that in a follow-up process that involved producing an action plan for habitat types, a variety of stakeholders were involved who softened the recommendations and made them less effective but more easily implemented (LP2).

5. Discussion

5.1 Red Lists leveraging and not leveraging sustainability changes

Our results show that the Red Lists are perceived to have leveraged sustainability changes in the social part of the Finnish social-ecological system. Perhaps surprisingly, we found that the Red Lists were linked to most of the leverage points. This indicates that Red Lists have the potential to leverage broader changes than have been realised. The contribution of Red Lists is not solely based on knowledge itself but rather on the processes of producing and disseminating it and on the various ways that the assessors are present in the science-policy interface, thus co-creating knowledge and society. The Red Lists, as other biodiversity assessments, are important monitoring systems, which ultimately leverage changes also in the ecological part of the system.

All leverage points for which we have results were co-coded with other leverage points. These co-codings show places that should be further examined for potential interactions. In some cases, our results show clear interactions, or even ‘chains of leverage’ (Fischer and Riechers Citation2019) between leverage points. For example, Red List knowledge could flow (LP6) into potential legislation (LP5) on ecological compensation (LP8), which could in turn increase the appreciation of nature and thus affect paradigms and goals (LP2 and LP3). Our results demonstrate how sustainability changes are leveraged and prevented by multiple coexisting and potentially interacting phenomena: the Red Lists have a role to play with more leverage points than just those at the shallow end of the list. O’Brien and Sygna (Citation2013) have argued that being numeric indicators, the Red Lists correspond to shallow leverage points, even though they acknowledge the importance of interactions between different leverage points. Our results support the idea that adjustments in even the simplest parameters may ultimately shift the mindset of actors and alter the intent of the system (Abson et al. Citation2017).

In the following, we emphasise the results that have importance for transformative change beyond smaller sustainability changes and conventional biodiversity conservation. They are focused on past events but show dynamics that may be important for future transformative change.

Lidskog (Citation2014) suggested that wider knowledge of the biodiversity loss problem provided by Red Lists could contribute to changing the dominant goal and paradigm, but our results indicate that economy-driven paradigms and system goals have prevented the Red Lists from leveraging sustainability changes. Similarly, Fischer et al. (Citation2022) found that in agricultural systems, paradigms and goals were short-term and capitalist profit driven. In a global survey, Rose et al. (Citation2018) found that perceived reasons for not incorporating conservation science into policy were associated with a low political priority of conservation. In addition, the dominance of the economic growth paradigm has been linked with a disconnection from nature (e.g. Pyle Citation2003), which has altered the capacity to sustain societal developments (Folke et al. Citation2011).

According to our results and previous literature, including the Finnish legislative, strategy and management recommendations texts, the Red Lists have leveraged sustainability changes at the rules of the system. Laws are fundamental components of sustainable pathways (Chan et al. Citation2020). Our results discuss how the Red Lists have affected especially the Environment Protection Act and the Forest Act. Affirming the results, the CitationEnvironmental Protection Act (527/2014) grants peat extraction permits only when nationally or locally significant nature values are not destroyed, and in evaluating the significance, the threat status of peatland species and ecosystems should be considered (see also Salomaa et al. Citation2018). Likewise, the Amendment to the Forest Act (Citation1085/2013), included the addition of some peatland habitats to the list of habitats with special values. In line with the results, the National Biodiversity Strategy (Finnish Government Citation2012) and National Action Plan (Citation2013–2020) directly refer to the Red Lists. The Proposal for Supplemental Mire Conservation could have also been noteworthy regarding the impacts of the Red Lists, but the planned conservation programme was politically halted (Salomaa et al. Citation2018).

Still, the all-encompassing threat to biodiversity that Red Lists describe has not resulted in holistic legislation prioritising nature over its use in Finland. Notably, in the interviews, there was an indication that political interests might have affected the formulation of existing legislation. Some actors may have an interest in orchestrating science to support certain aims (Lidskog Citation2014).

Our results describe several audiences and routes for Red List knowledge to decision making. Developing and sustaining relationships between knowledge producers and users and building systems for evidence use are some key factors for improving the use of evidence in policy (Nutley et al. Citation2019). Red Lists have a gatekeeping-like role in the social-ecological system; what is highlighted by them is more likely to be discussed in the next steps of the policy process, and consequently, to be targeted and affected by interventions. The lack of exact spatial data may be one of the reasons why knowledge is not used more widely in private sector decision making. Additionally, social or organisational norms may be reasons why existing knowledge remains unused (Pynnönen et al. Citation2019).

Also literature from other countries demonstrates that Red List knowledge has been transferred to the public, decision making and elsewhere. The application of Red Lists in legislative and policy use, monitoring and reporting biodiversity, design and management of protected areas, creating action plans for threatened species, prioritisation for conservation, restoration and development, land- and water-use planning, supporting management, for community projects and industry use, have been documented and predicted (Gustafsson and Lidskog Citation2013; Keith et al. Citation2015; Bland et al. Citation2019). Still, the Red Lists of Ecosystems could be better operationalised in policy instruments in different policy fields (Alaniz et al. Citation2019).

The Red Lists’ main goal – to assess risks to biodiversity – was reflected in the reluctance of several interviewees to engage stakeholders with political interest in the knowledge production but rather in the follow-up processes. Inclusion of stakeholders in knowledge co-production is called for in sustainability sciences (Clark et al. Citation2016; Miller and Wyborn Citation2020), but this is not unproblematic, as politics are involved in knowledge design (Miller and Wyborn Citation2020). Notably, based on the interviews, some actors from the forest industry would have wanted to affect the Red Lists’ production or at least questioned its accuracy. Rabaud et al. (Citation2020) found that Red List producers and users highlighted its scientific quality and disconnection from policy as giving it greater legitimacy and credibility; this independence is demanded by society. However, Gustafsson and Lidskog (Citation2013) and Jørstad and Skogen (Citation2010) found that Red Lists and governmental work were co-produced and thus didn’t follow a linear model where knowledge production precedes policy.

The Red Lists of Ecosystems have highlighted ecosystems as entities that should be governed, while the recommendations and their dissemination touch upon the questions of who should govern them (Turnhout et al. Citation2016). Based on our results, Red Lists are established and their use in existing Finnish institutions has been normalised, even though there have been attempts to obstruct this, as the critique of the first Red List of forest ecosystems shows. Red Lists knowledge has importance for possible transformative change, but only to the extent it gets taken up into the ways that publics engage with, deliberate and debate that knowledge and its relationship to power and how both knowledge and power should be put to use to construct and empower institutions to facilitate sustainability (Miller and Wyborn Citation2020). Notably, our results also show that environmental assessments affect interpersonal interactions, which can impact the dissemination of ideas and awaken interest in and awareness for the urgency of environmental problems (Riousset et al. Citation2017).

5.2 Reflection on our approach

We found Meadows’ framework useful for analysing if and where Red Lists have leveraged sustainability changes. As our aim goes beyond identifying leverage points, we do not argue that Meadows’ framework is the best way to identify them.

Despite a moderate response rate and sampling only the forest and peatland sections of the Red Lists, we expect that the assessors have adequately reflected on the interplay between Red Lists and Finnish society, due to their central position and relations with a breadth of stakeholder groups and the importance of the selected ecosystems. The results on leveraging sustainability could have been more comprehensive if we had interviewed assessors of other ecosystems, where the drivers and pressures of biodiversity loss are (partly) different. Our results reflect the perspectives of the interviewees, whose expertise is on ecosystems, and future research should also analyse the perceptions of other relevant actor groups that may be much more heterogeneous. Our selection may have left some social processes unnoticed, but for our research questions, this selection of interviewees was suitable, because other stakeholder groups might not be aware of the content of Red Lists. In the worst-case scenario, they might even question the importance of conservation to begin with. Our research does not account for all other intervening factors that also shape conservation policies.

A technical difficulty involved synthesising the results from 12 leverage points and their co-existence into an article format. Even though we did not find results on LP1, LP7, LP10 and LP11, these could have been found with other respondent groups or with alternative analytical choices, such as better including the ecological side of the system. Positive feedback loops (LP7) in the social system may be challenging to identify and thus unlikely to appear using general interview questions on a group of biodiversity experts. Unlike Chan et al. (Citation2020), we do not see an issue with placing competing goals of groups in LP2 and LP3; instead, we see they are implicit in it. For the paradigms and goals of the system to change, new paradigms and goals to replace them come from people with values that diverge from the dominant ones. Few codings of LP6 related to accountability, which was a central part of the original leverage point (Meadows Citation1999). This may illustrate how accountability for ecosystem loss is weak in our study system, or possibly that our method did not capture this. The lack of agreement over methods to assess transformative change makes our assessment somewhat subjective, but Fischer et al. (Citation2022) used a similar classification. Importantly, our results describe data relating to Red Lists; thus, many potential results on leverage points for transformative change were excluded from this paper if they did not have a connection with Red Lists.

To consider the applicability of the results outside Finland, one should remember Finland’s sparse population, large coverage of forests, peatlands and lakes, importance of forestry as an economic sector, rather long tradition of using knowledge regarding nature in governance, low corruption and strong democratic governance. Naturally, Finnish Red List use differs from the Red Lists in other countries. For example, awareness raising in zoos and donor funding (Betts et al. Citation2019) were not mentioned in our interviews.

6. Conclusions

Our results imply that Red Lists’ production and dissemination processes reach several interacting leverage points and could potentially contribute to transformative change. Thus, Red Lists can provide guidance on which parts of society need to be redesigned (Meadows Citation2001) to reduce harmful impacts on nature and at the same time increase positive impacts in certain areas. Therefore, changing the way Red Lists are produced has the potential to shape change. For example, their recommendations for action could have a wider scope. More diverse assessor groups could add societal relevance to the recommendations, however, our results indicate a need for caution if the assessor base is to be widened.

Our results from a Finnish context show how Red Lists have potential to leverage sustainability changes, especially at the level of paradigms, system goals, legislation and information flows. Nevertheless, none of them dominated the results, instead, we found several coexisting changes across the leverage point hierarchy. We hope our results will help enlighten the role of environmental assessments in advancing transformative change.

Ethics declarations

This research adheres to the ethical principles of research with human participants and to an ethical review in the human sciences in Finland (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK guidelines 2019). According to these guidelines, this research involving human subjects should not have obtained formal, prospective approval from an independent ethics committee, but verbal informed consent was obtained. This research adheres to the General Data Protection Regulation.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (300.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers and Janina Käyhkö, Sari Pynnönen, Heidi Tuhkanen and PONTE research seminar for their helpful comments and suggestions. We thank the interviewees for their input. was made by Joel Kanerva/Infograafikko.

Both authors were supported by the Koneen Säätiö (Kone Foundation). AS got funding also from the Academy of Finland Grant no. 338557 and the Strategic Research Council Grant no. 312624. Open access funded by Helsinki University Library.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2023.2222185

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abson DJ, Fischer J, Leventon J, Newig J, Schomerus T, Vilsmaier U, von Wehrden H, Abernethy P, Ives CD, Jager NW, et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio. 46(1):30–13. doi:10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Alaniz AJ, Pérez‐Quezada JF, Galleguillos M, Vásquez AE, Keith DA. 2019. Operationalizing the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems in public policy. Conserv Lett. 12(5):e12665. doi:10.1111/conl.12665.

- Amendment to the Forest Act (1085/2013).

- Berkes F. 2009. Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J Environ Manage. 90(5):1692–1702. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001.

- Betts J, Young RP, Hilton-Taylor C, Hoffmann M, Rodr´ıguez JP, Stuart SN, Milner-Gulland EJ. 2019. A framework for evaluating the impact of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Conserv Biol. 34(3):632–643. doi:10.1111/cobi.13454.

- Bland LM, Bland LM, Keith DA, Miller RM, Murray NJ, Rodríguez JP. 2015. Guidelines for the application of IUCN Red List of Ecosystems categories and criteria, Version 1.0. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. doi:10.2305/IUCN.CH.2016.RLE.1.en.

- Bland LM, Nicholson E, Miller RM, Andrade A, Carré A, Etter A, Ferrer‐Paris JR, Herrera B, Kontula T, Lindgaard A, et al. 2019. Impacts of the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems on conservation policy and practice. Conserv Lett. 12(5):e12666. doi:10.1111/conl.12666.

- Carey G, Crammond B. 2015. Systems change for the social determinants of health. BMC Public Health. 15(1):662. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1979-8.

- Chan KMA, Boyd DR, Gould RK, Jetzkowitz J, Liu J, Muraca B, Naidoo R, Olmsted P, Satterfield T, Selomane O, et al. 2020. Levers and leverage points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2(3):693–717. doi:10.1002/pan3.10124.

- Clark WC, van Kerkhoff L, Lebel L, Gallopin GC. 2016. Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. PNAS. 113(17):4570–4578. doi:10.1073/pnas.1601266113.

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 1992. The convention on biological diversity. Nairobi: United Nations Environmental Program.

- Davila F, Plant R, Jacobs B. 2021. Biodiversity revisited through systems thinking. Environ Conserv. 48:16–24. doi:10.1017/S0376892920000508.

- Dorninger C, Abson DJ, Apetrei CI, Derwort P, Ives CD, Klaniecki K, Lam DPM, Langsenlehner M, Riechers M, Spittler N, et al. 2020. Leverage points for sustainability transformation: a review on interventions in food and energy systems. Ecol Econ. 171:106570. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106570.

- Environmental Protection Act (527/2014).

- Finnish Government. 2012. Government resolution on the strategy for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in Finland for the years 2012–2020. Saving Nature for People.

- Fischer J, Abson DJ, Dorresteijn I, Hanspach J, Hartel T, Jannik Schultner J, Sherren K. 2022. Using a leverage points perspective to compare social-ecological systems: a case study on rural landscapes. Ecosyst People. 18(1):119–130. doi:10.1080/26395916.2022.2032357.

- Fischer J, Riechers M. 2019. A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 1(1):115–120. doi:10.1002/pan3.13.

- Folke C, Jansson Å, Rockström J, Olsson P, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Crépin A-S, Daily G, Danell K, Ebbesson J, et al. 2011. Reconnecting to the biosphere. Ambio. 40(7):719. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0184-y.

- Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. 2020. Secretariat of the convention on biological diversity.

- Gustafsson KM, Lidskog R. 2013. Boundary work, hybrid practices, and portable representations: an analysis of global and national coproductions of Red Lists. Nat Cult. 8(1):30–52. doi:10.3167/nc.2013.080103.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- [IPBES] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat.

- Jørstad E, Skogen K. 2010. The Norwegian Red List between science and policy. Environ Sci. Policy. 13(2):115–122. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2009.12.003.

- Keith DA, Rodríguez JP, Brooks TM, Burgman MA, Barrow EG, Bland L, Comer PJ, Franklin J, Link J, McCarthy MA, et al. 2015. The IUCN Red List of Ecosystems: motivations, challenges, and applications. Conserv Lett. 8(3):214–226. doi:10.1111/conl.12167.

- Kontula T, Raunio A. 2019. Threatened habitat types in Finland 2018 - Red List of habitats results and basis for assessment. The Finnish Environment 2.

- Kröger M, Raitio K. 2017. Finnish forest policy in the era of bioeconomy: a pathway to sustainability? For Policy Econ. 77:6–15. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2016.12.003.

- Leventon J, Abson DJ, Lang DJ. 2021. Leverage points for sustainability transformations: nine guiding questions for sustainability science and practice. Sustain Sci. 16(3):721–726. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00961-8.

- Lidgren A, Rodhe H, Huisingh D. 2006. A systemic approach to incorporate sustainability into university courses and curricula. J Clean Prod. 14(9–11):797–809. doi:10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2005.12.011.

- Lidskog R. 2014. Representing and regulating nature: boundary organisations, portable representations, and the science-policy interface. Environ Polit. 24(4):670–687. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.898820.

- Mace GM, Collar NJ, Gaston KJ, Hilton-Taylor C, Akçakaya HR, Leader-Williams N, Milner-Gulland EJ, Stuart SN. 2008. Quantification of extinction risk: iUCN’s system for classifying threatened species. Conserv Biol. 22(6):1424–1442. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01044.x.

- Manlosa AO, Schultner J, Dorresteijn I, Fischer J. 2019. Leverage points for improving gender equality and human well-being in a smallholder farming context. Sustain Sci. 14:529–541. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0636-4.

- Maxwell SL, Fuller RA, Brooks TM, Watson JEM. 2016. Biodiversity: the ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature. 536(7615):143–145. doi:10.1038/536143a.

- Meadows D 2001. Dancing with systems. Whole Earth. 106:58–63.

- Meadows DH. 1999. Leverage points – places to intervene in a system. Hartland, VT: The Sustainability Institute.

- Miller CA, Wyborn C. 2020. Co-production in global sustainability: histories and theories. Environ Sci. Policy. 113:88–95. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.016.

- Ministry of Environment and Finnish Environment Institute. 2021, Oct 26. Uhanalaiset lajit [Vulnerable species]. https://www.ymparisto.fi/fi-fi/luonto/lajit/uhanalaiset_lajit.

- Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S, Simpson, AGB, Worm B. 2011. How many species are there on earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol. 9(8):e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.

- National Action Plan. 2013–2020. National action plan for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in Finland 2013–2020. Saving Nature for People.

- Nutley S, Boaz A, Davies H, Fraser A. 2019. New development: what works now? Continuity and change in the use of evidence to improve public policy and service delivery. Public Money Manag. 39(4):310–316. doi:10.1080/09540962.2019.1598202.

- O’Brien K, Sygna L. 2013. Responding to climate change: the three spheres of transformation. Proc Conf Transform Chang Clim. 16–23.

- O’Neill DW, Fanning AL, Lamb WF, Steinberger JK. 2018. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat Sustain. 1:88–95. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4.

- Otero I, Farrell KN, Pueyo S, Kallis G, Kehoe L, Haberl H, Plutzar C, Hobson P, García‐Márquez J, Rodríguez‐Labajos B, et al. 2020. Biodiversity policy beyond economic growth. Conserv Lett. 13(4):e12713. doi:10.1111/conl.12713.

- Pyle RM. 2003. Nature matrix: reconnecting people and nature. Oryx. 37(2):206–214. doi:10.1017/S0030605303000383.

- Pynnönen S, Salomaa A, Rantala S, Hujala T. 2019. Technical and social knowledge discontinuities in the multi-objective management of private forests in Finland. Land Use Policy. 88:104156. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104156.

- Rabaud S, Coreau A, Mermet L. 2020. Red lists of threatened species—Indicators with the potential to act as strategic circuit breakers between science and policy. Environ Sci. Policy. 113:72–79. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.04.003.

- Riousset P, Flachsland C, Kowarsch M. 2017. Global environmental assessments: impact mechanisms. Environ Science & Policy. 77:260–267. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.02.006.

- Rose DC, Sutherland WJ, Amano T, González-Varo JP, Robertson RJ, Simmons BI, Wauchope HS, Kovacs E, Durán AP, Vadrot ABM, et al. 2018. The major barriers to evidence-informed conservation policy and possible solutions. Conserv Lett. 11(5):e12564. doi:10.1111/conl.12564.

- Rosengren LM, Raymond CM, Sell M, Vihinen H. 2020. Identifying leverage points for strengthening adaptive capacity to climate change. Ecosyst People. 16(1):427–444. doi:10.1080/26395916.2020.1857439.

- Salomaa A, Juhola S. 2020. How to assess sustainability transformations: a review. Global Sustainability. 3(e24):1–12. doi:10.1017/sus.2020.17.

- Salomaa A, Paloniemi R, Ekroos A. 2018. The case of conflicting Finnish peatland management – Skewed representation of nature, participation and policy instruments. J Environ Manage. 223(1):694–702. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.048.

- Stuart SN, et al. 2017. IUCN’s encounter with 007: safeguarding consensus for conservation. Oryx. 53(4):741–747. doi:10.1017/s0030605317001557.

- Turnhout E, Dewulf A, Hulme M. 2016. What does policy-relevant global environmental knowledge do? The cases of climate and biodiversity. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 18:65–72. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.09.004.

- Turunen J. 2008. Development of Finnish peatland area and carbon storage. Boreal Environ Res. 13:319–334.

- Venter O, Sanderson EW, Magrach A, Allan JR, Beher J, Jones KR, Possingham HP, Laurance WF, Wood P, Fekete BM, et al. 2016. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat Commun. 7(1):12558. doi:10.1038/ncomms12558.