ABSTRACT

The vulnerability of the Amazon has widely increased with the COVID-19 global pandemic and with the dismantlement of environmental protection policies in Brazil during the Bolsonaro administration. By contrast, local initiatives focusing on sustainable production, conservation, enhancing local people’s quality of life, and supporting a more inclusive economy have emerged throughout the region and are building resilience in face of these disruptions. They represent seeds for transformation towards more sustainable trajectories from the ground up. In this context, women play a significant role, but their actions and voices are poorly understood, studied, or even considered. In this article, we use a novel approach to engage and highlight women’s experiences by connecting decolonial and process-relational perspectives. Decolonial and process-relational thinking are closely linked in many ways, including in that they embrace difference as a mode of experiencing social-ecological relations. One particular aspect of this link is the shared focus on liminal thinking or thinking from the borders, what we call ‘betweenness’. In our decolonial praxis, we highlight women’s perspectives on their particular and diverse ways of life in the Amazon as they confront diverse pressures. To this end, we collaborated with 39 women from Santarém and neighboring towns in western Pará through participant observation, semi-structured interviews and facilitated dialogues. We discuss their perspectives on regional transformation, particularly the expansion of large-scale agribusiness around rural communities, and their understanding and responses to these changes. We reflect on the mutual learning experience resulting from the transdisciplinary engagement between researchers and collaborators.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction ~ on (her-)stories

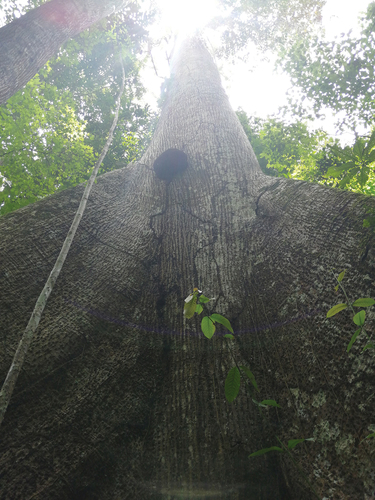

It is not easy to understand the Amazon’s irreducible lattice of rivers, forests, animals, weather systems, diverse peoples and cultures, all historically intertwined within national and global economies. Many smells can be carried away with the wind, unnoticed by the agitated minds of the townspeople. There are diverse sounds brought by animals, insects, and invertebrates, and there are changing lights, engaging with the trees, exposing big and small lives. The untouchable and invisible are also present. The stories, legends, traditions, cults, and visions of those living entangled with the forest. For women living in and by the forest, each of these elements is an integrated part of their everyday lives. In turn, the sounds of the Amazon, its infinity of smells, and its embedded people form what we still have, know, and do not know of as the largest rainforest in the world. Some of the women this article focuses on are part of the forest, including islands of forest surrounded by pasture and agriculture, others live in farm-lots opened in decades past; and yet others live in the urban centers, but they are all involved in one way or another with agricultural and forest activities, including processing products and participating in farmers’ markets. Several of the women involved in this study are leaders of women associations in the region. Many of them are first- or second-generation colonists, those who arrived with their families attracted by agrarian reform programs during the 1970s and 1980s. They have seen and have been part of the regional transformation and have come to assume forefront roles in resisting oppressions and pursuing more sustainable livelihoods. Here we take a gendered perspective to discuss their entanglement within the larger social-ecological transformations of the region. We apply this perspective to the Amazonian context, whose landscape configuration can only be understood through the history of human activity (Erickson Citation2008; Ross Citation2017), in which women played a major role ().

Figure 2. Vegetable garden near a woman’s house in a rural settlement in the Mojuí dos Campos-PA region.

Figure 3. Cucumber harvest in a vegetable garden inside a woman’s productive backyard within a community of the Flona Tapajós-PA conservation Unit.

Women’s relationship with plants and animals is part of their everyday life. As we will see through the article, many of the women who collaborated on this work considered the knowledge they carry to be matriarchal and nature based. Knowledge about the seasons of the forest, ‘fully’-’dry’, winter-summer indicate when to seed, harvest, where to extract products and which. The singing of the birds can have many meanings – from dangerous animals in the surroundings to the coming of rain or the dry season. The knowledge of forest medicine and the knowledge of forest spirits are used for blessings and to heal the sickness of the body and soul. Women have faced many challenges that jeopardize their little-regarded knowledge and ways of life. In parallel, the Amazon has been disrespected and seen as an empty space to be explored in the name of development (Moran Citation1996; Denevan Citation2014; Salles Citation2022).

Women represent more than 48% of the farming labor force across low-income countries (FAO Citation2021). They are also responsible for household activities and holders of local knowledge in relation to agriculture or extractivism due to their historical practices (Alvares Citation1995; Karam Citation2004; Chaves and de Assis César Citation2019). Yet, their key role is overlooked and not sufficiently understood. Recent research has shown that women play an essential role in securing food and agricultural diversity in the Amazon, ensuring rural families’ permanence in the field and promoting women’s inclusion in local governance and regional organizations (Freitas et al. Citation2020; Brondizio et al. Citation2021). They also play a role as healers, which is why, most often, medicinal and ornamental plants are close to the women’s homes, which helps them carry out their multiple activities simultaneously (Murrieta and WinklerPrins Citation2009). We argue here that their practices offer interesting and important insights into resisting the causes that have recently led to forest degradation and into establishing more sustainable pathways forward. Listening to their voices will help us see and understand critical pieces in the conservation and potential transformations towards sustainability in the Amazon.

Listening to the voice of the Amazon herself is to understand she as a living system, which in the perspective proposed here is an entanglement of relationships between humans, non-humans and the spiritual world. A system that intertwines, modifies, collaborates, observes, experiences, transforms, and only exists from its constitution through these relationships (). Therefore, we will discuss in this article how decolonial and process-relational thinking – can open up new possibilities for feeling, thinking, doing science and becoming in the process. We believe these perspectives can contribute significantly to transdisciplinary research and, perhaps, to rethinking what transformations for sustainability are or can be from the inside out.

Figure 5. Collaborators preparing andiroba oil in a community of the Flona Tapajós conservation Unit.

In the next section, we first explain: a. decoloniality as a praxis, which in this paper is applied in two ways – first, as a conceptual and methodological approach, and second, as part of an ethnographic approach to bring forward the perspectives and voices of collaborating women in the Amazon; b. we present the concept of becoming, from process-relational perspectives; c. we show what these two concepts in conversation can bring to transdisciplinary sustainability science when used together.

1.1. Her-stories ~ decoloniality

We use decoloniality-as-praxis throughout the research process to imagine and act on other forms of doing (and writing) research (Smith Citation1997; Mignolo Citation2009) than hegemonic approaches. Decolonial practices are opposed to and seek to denounce colonial practices which reproduce the power imbalances imposed by the colonial order, dismissing local knowledge and imposing western abstractions universally. Decoloniality as a praxis demands continuous observance and reflexivity in which unlearning and critical examination are at the center of our thinking and actions since most of us have been socialized in the western system of thought, which structures schools and universities. It requires decentralizing western rationalities and offering space for other ways of knowing, being, relating and doing science – and can ultimately serve as an instrument for social action (Freire Citation1970; Gadotti Citation1996; Wynter Citation2003; Pashby et al. Citation2021; Hayes et al. Citation2022).

In Latin America and the Caribbean, Franz Fanon, through lived experience and language, invited readers to rethink ontologies in light of coloniality and the search for decolonization (Fanon Citation2008). Quijano (Citation2000), paved the way for decolonial thinking, developing concepts such as the coloniality of power – elaborated further by Walter Mignolo (Citation2007, Citation2009, Citation2011) as the constitutive characteristic of the coloniality-modernity nexus, which means that there is no modernity without coloniality. From this perspective, modernity is only possible through the logic of domination, oppression and exclusion of the other founded by the colonial power, often subtly presented. Therefore, to analyse the cultural, economic, political and social dimensions of modern logic, the concept of coloniality of power is central. Grosfoguel (Citation2008) presents coloniality as a concept that makes it possible to understand the continuity of the colonial legacy and forms of domination after the end of colonial empires. Thus, to break with coloniality in terms of political and onto-epistemic power requires a process of decoloniality, not decolonization – the latter is the undoing of colonialism, whereby a nation establishes and maintains its domination of territories.

Decolonial thinking is also essential to deconstructing a colonial image of Southern women. To make sense of the multiple roles and identities that women are a part of we make use of a border-thinking perspective called ‘dwelling in the border’ (Anzaldúa Citation1987). Dwelling in the border is a necessary prerequisite for engaging in border thinking. It is a painful place where one lives, thinks and feels differently and rescues subaltern knowledge and perspectives to challenge hegemonic onto-epistemologies. In this way, being indigenous, afro, mestiza, Latina, or rural means to exist in the pluriverse, this is a world of many worlds, diverse from the modern-colonial concept of the universe, with universal truths (Escobar Citation2016). The decolonial perspective through border thinking recognizes the act of resistance and resignification of the women who collaborated in this research within the painful fracture of colonization (Anzaldúa Citation1987; Lugones Citation1992, Citation2010).

Border thinking is not about geographic borders but a possibility for a critical rethinking of geopolitics, the political body of knowledge, identity, modern/colonial foundations, the analysis of the political economy, and gender (Anzaldúa Citation1987; Mignolo and Tlostanova Citation2006; Lugones Citation2010). Border thinking through dwelling in the border sheds light on the internal and external spaces between different worlds, a mestiza consciousness (Cusicanqui Citation2018) or similar to the concept of double consciousness, conceptualized by the African-American sociologist W.E.B. Dubois (Mignolo and Tlostanova Citation2006; Falcón Citation2008). As Mignolo and Tlostanova (Citation2006, p. 218–219) point out, border thinking proposes how to deal with the ‘imperial sedimentation while at the same time breaking free of the spell and the enchantment of imperial modernity’. Feelings, emotions, violence, vulnerabilities, consciousness and unconsciousness, and subjective forms of imperialism/coloniality are an essential part of what shapes those who live on the border, in-the-between.

1.2. Process-relational - Women-Amazon-Research(ers)

In sustainability science, scholars have considered not only the complex characteristics of socioecologial system (SES) but also focused on understanding the entanglement of interactions between nature and humans (Berkes et al. Citation2000). Conceptual and empirical studies of SES have increased focus on the relationality of these interactions (Cooke et al. Citation2016; Cockburn et al. Citation2018, Citation2020; Stenseke Citation2018; Mancilla García et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Process-relational approaches are currently also defended in other fields, as presented by Mancilla García et al. (Citation2020b). Mancilla García et al. (Citation2020b) argue that process-relational thinking understands the socioecological system as a single realm. They do not exist separately and interact with each other, but the socioecological is constituted through processes and encounters. In this view of reality, relations have causal agency and are prior to objects whose identities are formed by those same relations. Consequently, the ontological understanding of the social and the ecological can only occur in relation to each other (Mancilla García et al. Citation2020b, p. 4).

The entangled understanding of the Amazon could only be understood if we consider the human activity that has shaped her (Erickson Citation2008; Ross Citation2017). Hence, these activities are characteristic of the existence of the Amazon and the women who inhabit her – they become one. This resonates with Hertz et al.’s (Citation2020, p. 330) questioning of whether we ‘can really understand and explain what a social-ecological landscape is without taking into account constantly changing past and present processes of interaction, that at any moment influence, support, enable and condition – and ultimately define what the communities and the forest are’. Processes unfold in different ways, they are recursive: product and producer of what we typically see as context. In reconfiguring new possibilities, processes create the present moment, which reverberates in time and space, creating new processes (or possible new futures). The processes of change become a fundamental element in understanding these women, their actions, and/or lack of them.

From a process-relational thinking perspective, a unique subject (the womenatureFootnote1) is inherited from previous experiences; however, both are also producing a ‘novel togetherness’ (Whitehead Citation1929). They are not simply ‘one’, but ‘many’ and in this ‘manyness’, they are becoming one. The immediacy of womenature subjective experience is constituted not only by the environment they live in but by their personal past, culture, knowledge and techniques, unconscious memories of the past, by the society in which they were born. In the case of the Amazon, the same occurs; the territory she also habits as the home of billions of species, the enchanted (the spiritual world), microscopic societies that form a larger society, that form other societies, that form the biome where we dwell within the larger society called Earth.

In a mirrored way, this article only exists because of the various processes of becoming. Through the leading author’s relationships with the women, but above all, through the constitutive relationships of women with the Amazon – and vice-versa. Everything is an ingression of possibilities that always occur in the present moment, feeling and experiencing the past moment with the entities, communities, and societies around us and within. At every moment, we are always choosing, nature ~ the Amazon chooses too; we live in the process of entangling realities of agency, decisions and possibilities – this research itself, becoming what it is through the feeling we experienced with many, women, co-authors, editors and including the Amazon. We ended up sharing certain characteristics from those many entities (Whitehead Citation1929) that turned us into one more – a possibility of one more world inside the world.

1.3. Decoloniality & process-relational – the betweenness and how it can contribute to transformative processes and transdisciplinary research

Transdisciplinary research is fundamentally based on knowledge co-production integrating a plurality of epistemologies (Sellberg et al. Citation2021; Hakkarainen et al. Citation2022). According to Hakkarainen et al. (Citation2022), transdisciplinary research has the potential to accelerate transformations – understood as fundamental changes in technological, economic, and social factors, including paradigms, goals, and values intended to advance more socially-just and environmentally sustainable system. Recent academic discussions within transdisciplinary sustainability science point to a growing ‘relational turn’, as, for example, the special issue on relational values in COSUST attests of. These discussions seek to understand in-depth human-nature relationships (Gallegos-Riofrio et al. Citation2022; Mancilla García et al. Citation2020b; West et al. Citation2020; Walsh et al. Citation2021; Eyster et al. Citation2023). However, one of the major challenges in transdisciplinary research, as exposed by Chilisa (Citation2017), is how to conduct research that enables equality in the decisions around framing research topics, methodologies, and strategies among academics, practitioners, and local communities (Chilisa Citation2017). Additionally, Sellberg et al. (Citation2021) present challenges of the current dominant academic environments and the institutions that do not support transdisciplinary research flourishing.

We would like to build on these concepts with the suggested perspective of betweenness to comprehend the women who worked with us, their knowledge and the Amazon more profoundly. Every entity, including the Amazon forest herself, is a fundamental part of the unfolding process of becoming, a process that never ends and offers many possibilities in the practice of these women and their multiple living spaces. It also opens spaces up to think about the present and future in a plural way, pluriversal ways of living and being – which is not separated from the research process. Therefore, rethinking the research’s methodological approach, how it is conceived, elaborated, and conducted, becomes fundamental in transdisciplinary research – which will be further elaborated in part 3 under ‘Methods and Analysis’ of this article.

Transformation is addressed here specifically as actions to create a more sustainable, fair, and equitable world. This includes considering the research itself as part of an ethic-onto-epistemology (Barad Citation2007) where the added decolonial lens helps understand how hegemonic science has been built upon the philosophical paradigm of positivist/dualistic position (and is still influenced by it). Our position stands at odds with the ontological stance of positivism that has dominated modern science and which considers reality as objective and available for discovery by using universal laws and methods, generally focusing on identifying explanatory associations or causal relationships through quantitative measurement (Smith Citation1997; Turyahikayo Citation2021). In this perspective, people’s opinions, values, and beliefs about reality can be wrong and stand no relation to science and knowledge. In other words, knowledge must be observable and measurable based on analyses that allow positivist scientific predictions that use deductive reasoning (Smith Citation1997; Turyahikayo Citation2021).

‘Sound science’, conceptualized by Stengers (Citation2018, p. 23), refers to this phenomenon meaning that, ‘only sciences that can prove things, that is, that can evoke facts as authoritative, are worthy enough to avoid disqualification’. Science here is presented as rational, objective, and universally true, and thus will eventually replace all other forms of knowledge. Transdisciplinarity will only be possible if we break the patterns that reinforce power asymmetries outside and inside science. Every type of relationship is loaded with power, for this reason, different actors, including us researchers, need to be careful not only in how we relate to each other (Bieling et al. Citation2020; West et al. Citation2020; Sellberg et al. Citation2021; Staffa et al. Citation2022), but also, how our relationships take place. In this sense, the concept of betweenness is highly relevant within transdisciplinary science and practice as it recognizes structural power systems inside and outside academia. Moreover, the in-between position of researchers and collaborators offers possibilities for being comfortable positions with shady boundaries, such as researcher and apprentice, in which transdisciplinarity occurs through horizontal exchanges of knowledge.

Finally, ‘in-betweenness’ - this portrays living between worlds, in rural areas, but also in urban centers; the traditional and the ‘modern’ and recognizes movement/mobility as part of women’s autonomy and agency. This movement/mobility involves their very being (and becoming), and this includes their resistance and struggle against the events that impact their lives, cultures and environments. Women express the reality of experiences in between places and conditions, in the act of resisting oppression that happens between worlds. They are also the many peoples, places, beings, memories, enchanted who shaped them; the ‘manys’ of the world itself are who they are and whom they are becoming. Women are an act by which many of the universes become one, and by becoming one, the diversity of things in the universe has increased by one. The betweenness reflects not only the processes of women and the Amazon who are collaborating in this research but the process of doing this research itself – being changed by ‘womenature’, and becoming a (better) researcher(s) – enabling the transformation processes to happen.

2. The Amazon in this research

The research was carried out in Santarém, Belterra, and Mojuí dos Campos, municipalities of western Pará, in Brazil, where individuals and groups of women have increasingly been agents of local transformation in supporting their households and communities in sustainable land-use practices, associativism, and activities aggregating value to their knowledge, biodiversity, and resources. Since the 1960s, the Santarém region has been targeted by development projects and has hosted several modalities of agrarian reform settlements occupied by both family and agro-industrial farms (Dalazen et al. Citation2020). After 2000, mechanized soybean production and the migration of capitalized farmers caused intense and rapid land-use and land-cover changes, affecting population dynamics and the landscape configuration (Adams Citation2008; Coelho-Júnior et al. Citation2022).

Nevertheless, this region is constituted by a mosaic of protected and unprotected areas, indigenous lands, afro-descendants lands, and riverine territories, with high ethnic, cultural, social, and ecological diversity, and as such, the region is of fundamental importance for the strengthening of conservation practices and policies. Women dwell in this region themselves by participating in associations, cooperatives and community-based initiatives confronting agribusiness, mining, loggers, and large corporations. The prominent role of women in place-based sustainable initiatives in the region is in line with the AGENTSFootnote2 database, which reveals a high representation of women’s networks in the Amazon (Brondizio et al. Citation2021). In this database, women’s networks, small groups for agroecological production, and women’s associations had high representativity, especially around Santarém, the little piece of the Amazon experienced by the authors ().

3. Methods and analysis

3.1. Decoloniality and process-relational perspectives in research design as a way to transform

Methodologies are essential for decolonial praxis, and it is, therefore, essential to rethink them. The research method in decolonial praxis requires a non-negotiable commitment to collective methodological liberation, in addition to asking for the necessary flexibility to seek alternatives to anti-extractivist research. As Smith (Citation1997) puts it, the decolonial praxis advocates for alternatives and culturally appropriate methods and ‘needs a radical compassion that reaches out, that seeks collaboration, and that is open to possibilities’ (Smith Citation1997, p. xvi).

Fieldwork supporting this study was carried out between December 2019 and April 2020, in two expeditions. First, a group of researchers from the AGENTS project invited women and men leaders to participate in a workshop to present their initiatives, discuss challenges and opportunities, and help the project to map other initiatives in the Amazon.Footnote3 This event was followed by field visits that opened opportunities for the development of the lead author´s master dissertation entitled ‘Understanding women stewardship in the Amazon: a decolonial-process-relation perspective’ (Sonetti-González Citation2020), in which this article is inspired.

This research follows the principles of Participatory Action Research (PAR) (Fals-Borda Citation1987, Citation1991). PAR is characterized by overcoming the binary position of subject-object, therefore, engaging with women as collaborators – rather than informants or objects (Vásquez-Fernández et al. Citation2018). It is committed to changing different levels of society so that the most exploited classes can consciously assume their role as actors in history. It is, ultimately, an attempt at non-exploitative patterns of life (Moreno-Cely Citation2021). PAR also focuses on the praxis of methodological liberation from theory to practice and back again (Freire Citation1970) – contributing to the women’s agenda in their own way, contributing to their liberation.

To do this practically, the lead author and collaborators relied on mutual participation and reflection; we had informal conversations about the situation of women in the social and political spheres, and also about life and living the different realities and the realities of their differences, as well as the challenges and alternatives that we face as rural women, as community leaders or as researchers, with a mutual and genuine interest. These conversations took place in different spaces, at farmers’ markets, at social gatherings, and the women´s homes. They helped to promote self-reflection about the realities, knowledge, and solutions that we seek and put into practice every day. The lead author also cooked out with collaborators, took river bath, and made buriti (Mauritia flexuosa) and andiroba oil (Carapa guianensis) with them. This relationship building or this process of creating relation(onal)shipsFootnote4 is an attempt at a less extractive way of doing research than traditional approaches, as the objective was to feel the women´s realities and let them feel and exchange with the lead author. The conversations were rich, relaxed, and more fluid during these activities on both sides.

From conversations, new questions emerged, and a reformulation of the initial ideas was necessary to respect relational accountability (Wilson Citation2001). From the empathic involvement in these processes or the ‘vivencias’, the lead author critically evaluated during her fieldwork the possible results together with the collaborators through conversations (Fals-Borda Citation1987; Fals Borda and Moncayo Citation2009). Having them as allies in the analysis of first observations, impressions and the pre-analysis not only empowered them as collaborators but included their knowledge in a horizontal way. The alignment between knowledge and practice has long been called for as part of transdisciplinary research (Gibbons Citation1999). Opening space for the co-creation of a unique Latin American ‘folk-science’ (Fals-Borda and Mora-Osejo Citation2007), through a sentipensante praxis – using the mind and the heart together throughout the research processes (Fals-Borda Citation1987). To integrate this into the research practice, the collaborators and the leading author practiced vivencias (in English it would be ‘experiencing’). Las vivencias is the soul of PAR and is found in the researcher’s personality and commitment. A vivencia is literally something like has been lived, a life experience and in PAR, particularly, an experience that comes from the heart and the head at the same time, an intellectual and sentimental experience. Practicing vivencias requires the researcher to base their observations on conviviality with communities. It is a basis to promote self-reflection about realities, knowledge, and solutions sought and put into practice every day.

In addition to conversations and vivencias, 34 semi-structured interviews were conducted with local actors, including government agents, NGOs, academics, and 22 people who self-identify as women − 19 of them identified farming as their primary activity – although all of them confirmed having either vegetable gardens or small poultry production in their backyards. In total, 14 initiatives and social movements and five farmers’ market were visited. The final results of the analysis were validated by collaborators with whom the lead author worked during fieldwork (leaders of women’s associations in the region of focus in this study). Furthermore, a copy of the master’s thesis was given to these leaders and most collaborating women during the final meeting of the AGENTS in August 2022 in the city of Santarém-PA to present the main results of the project to local partners. We were also curious to understand what this experience was like for some of the women. Although we did not have the opportunity to ask every one of them, those who were closest to the lead author throughout her thesis process shared some of their reflections, which are presented in the next section.

3.2. Analysis

Informed by collaborative reflections during fieldwork, field interviews were transcribed and analyzed through the ‘hybrid form of the thematic analysis’ suggested by Boyatzis (Citation1998, p. 51). This analysis type is recommended when one group has been studied to identify meaningful themes. The analyses were carried out with the help of another member of the AGENTS project.

The care, ethics and commitment before, during and after the research processes reflect the possibility of an activated consciousness of care. A possibility of collective emancipation, a decolonial praxis beyond ethics – a journey of decolonizing ourselves. Haraway (Citation1988, p. 583) gives us a glimpse of this experience when she asks us to look at, ‘the loving care people might take to learn how to see faithfully from another’s point of view’. That could also be seen as a ‘care for our abstractions’- the drops of realities experienced (what does ‘data collection’ mean if not abstractions?).

4. Results & discussion on processes of changing

4.1. Strategies of resistance

We present in this section some of the themes resulting from the analysis, highlighting the perspectives of women on their particular and diverse ways of life in the Amazon as womenature - a system that lives in its becoming resistance.

Women in Santarém and neighbouring municipalities face different forms of violence (Chaves and de Assis César Citation2019). Violence against their bodies through domestic and social violence but also through violence in their territories, with the advance of agribusiness that strongly impacts them. Indeed, during our conversations, women who live in different parts of the region (in urban areas, rural areas, rural settlements and protected areas) were unanimous in saying that the diverse impacts of agribusiness in the region have been the main reason for rural communities’ disappearance. As we can observe in the following quotes, the advance of agribusiness is especially affecting women in the region and creating a cycle of vulnerability in the large centers of the region:

Women are the most affected [by soy production], as they suffer from the impacts of this production and [suffer because of] the impacts on their families. (MA28)

If a neighbour says they will not sell their place, the big farmers will buy the farm next door, then the bees, the chickens will die [because of the agrotoxics], and the person will get angry and end up selling it. […] Then the poison reaches the person, and what happens? They will move to Santarém’s periphery, but with that money, they are unable to buy a house […], and the family has to return to the community or go to a more distant one, but the settlements have no road, no water, no school … (MA3)

However, their statements always draw attention to their relational perspectives and the best care women have for nature.

We must think about the well-being of everyone and respect our life, the life of nature, because if we don’t have this awareness, we will end up killing ourselves… It is important that people make this reflection and have a new education, right? Educate ourselves so we can live longer with our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren… Because if we think about this new lifestyle of these large-scale producers, who have more conditions than us, if everyone uses pesticides, who will survive afterwards? (MA20)

The woman is more careful, she better identifies the development of the plant. My brother and my sons plant cassava in any way, but if they plant it any way, the cassava will grow all messed up and when it comes the time to pull it up, it will be a problem. So we women, learn that most of the time, people call this a grave, but we don’t. The grave is for the dead, we call it the plant’s cradle because from there, the plant will grow and develop – if you say it’s a grave, she will die! (MA3)

Women are converting challenges into opportunities for resistance and are developing a range of creative actions to support their way of living, which serves as a basis for social transformation. Even under the pressures of modernity and hegemonic socio-economic processes, communities maintain their cultural and spiritual practices associated with natural landscapes (Merçon et al. Citation2019). In this process, there is, however, recognition of the need for strengthening women’s organization and the sharing of collective experiences and ways of living. While the development of associations dates back to the 1970s in the Amazon, women’s organization through associations is something relatively new, but has been increasingly structured over the last few years. Relationships with other women and their networks are also fundamental to their agency and have the potential to strengthen their agency, which can occur through participation in social movements such as women’s associations, cooperatives, or unions. Here, it is crucial to understand that these social networks are socioecological networks, as women bring to them their socioecological identities constituted from the relationships with the environment where they live and experience their lives; it is their very entanglement as womenature that is brought to these social gatherings. Most importantly, despite their in-betweenness experiences, living or experiencing their lives in rural and urban areas, these women base their identities on their practices, in other words, their ‘nature’ identities are inscribed in their ‘women’ identities. The increased participation of women inside their communities and social movements is something that Escobar (Citation2017, p. 16) calls ‘processes of “matriarchalization”’.

We [women part of the association] work and produce as “family farmers” with agroecological practices because we have been fought so much against agribusiness, which brought pesticides to our region, but we want to do differently, we want to be the resistance. (MA32).

Through the quotes above, we realize that not everyone in the region plants with the care that women do. Reports are that most men want to plant a single crop and use agrochemicals, which would guarantee a higher income. Many women, however, refuse to produce in this manner. Yet, it is important to put this into context so that the confrontation between different perspectives is better understood. Indeed, even within agroecological farmers’ markets, there is a tendency for the individual capitalist way of thinking to override the principles of solidarity economy upheld by those participating, and as MA12 puts it, embodying the practices of resistance in their very participation in the farmers’ markets is an essential part of their practice.

We have to be careful not to romanticize too much this cooperation between them [women] because it could be lost at some point. For example, here at the fair, what we are reinforcing this year are the principles of solidarity economy, this fair has a political stamp - we are the resistance! We are not here at the fair just to sell products, but also to be a space for the family farming to show itself. (MA12)

4.2. Women embody a social-ecological systems

Relationships are perceived by women as essential to resist in their territory. This can be framed as an ‘embodied’ connection, suggesting that humans are immersed in their environment mentally, materially, and physically (Cooke et al. Citation2016). This is particularly important in the case of women, who build these connections not only for their social relationships but also as a survival strategy. The betweenness perspective can help us highlight that ‘connections’ are not an interaction between two entities but rather an entangled and intrinsic existence of people and places. Part of this entangled is also the spiritual world and the entities of the forest ‘os encantados’ (the enchanted).

In an environment of constant and perennial changes, innovating becomes a recurring action. The reconfiguration of products and elements of nature contributes to food diversity, which occurs mainly through the reconfiguration of natural elements such as the production of açaí coffee, different types of cassava flour, bread, jams, juices, and spices, among others. The collaborators usually experiment with new ‘formulas’ in the production of foods – as explained by MA14,

Each one [of us] has our curiosity and knowledge; then we end up sharing our knowledge. A formula is achieved, and everyone wants to test it! For example, I come and say look what I did, and I did it like this, like that, and then the other will try it. But each one also has its own way, and each test it differently [the recipes]. (MA14)

This process of trial and error, evolution, and observance, not only contributes to food diversity but also to local biodiversity. The Amazon thus comes into being as it is due to the relationships that constitute it, including the human-imprinted relationships. This process occurs throughout the Amazon, represented in diverse Indigenous agricultural systems around the region of Rio Negro. It enriches the local biodiversity, and its characteristic is the coadaptation between these peoples and the Amazon (Cunha Citation2014; Almeida and Udry Citation2019; Cunha et al. Citation2022). Finally, changes such as climate change or land-use change impact women’s lives within and in the landscape as well as their production. Thus, they proactively seek alternatives to overcome the new challenges, mainly through their network of relationships.

4.3. Praxis ~ the lead author reflecting on the action of carrying out this study in the Amazon with collaborating women

Being with women collaborators from around Santarém region made me reflect on many of my positions and questions as a student – at the time – of a master’s degree. This reflection became almost an anguish about what to do and how to do ethical research faithful to the women who were collaborating with me. I, then, because of our conversations and their guidance, changed everything. I changed. I realized that the ‘in-betweenness’ made sense during the fieldwork. Also, beyond reflections, I was experiencing vivenciando becoming a new person in each and every moment. Once again, since I moved out of Brazil, I felt my mixed-race conscience. Despite my family belonging to a working-class, being the granddaughter of indigenous people, I am a white woman from the Center-South, the country’s wealthiest region. I then remained in my trouble of ‘representing’ a university in northern Europe and being recognized as such. This awareness made me have a radical commitment to the Amazon and the women who had such an impact on me. The Amazon embraced me, and in this embrace, she changed me forever; it was the second time I was experiencing her. The women welcomed me not just for a few hours but into their homes, routines, and lives – for weeks, without wanting anything in return. Affection and community increased my universe by one and made me a researcher.

4.4. Women leaders confronting pressures and gender discrimination on the ground, and the research process

Although we did not have the opportunity to return to all the collaborating women who participated in this research, those closest throughout the lead author’s master thesis process were asked if they would share their perspectives and feelings regarding this process. Some of the questions that served as a basis for the reflections were: how did they see this experience? What could have influenced them? How do they think they influenced the leading author? The project AGENTS? We leave the passages here for the active reflection of the readers.

MA2: For me, it was very good, because I saw that you had an idea of the women here, but when you arrived, you saw that it was something else. You’ve seen that the women here are massacred and commanded by the men. We do not have study, neither we have resources. So, I think it impacted you to see this reality; not everything they say is true. And also to show that the women here are not weak. They do everything as men do … They do not achieve much, though, but they fight! So, this was good for me because you had the opportunity to see things here, how our reality is here, and you also showed that you are not weak; it is not just because you have an education that you are weak. You went through many barriers here to do your study. Because you were surprised here with what you came to do, but at no time did you fall. As I told you, I have guided you – no, you are not going to do what you came here to do, but I will point you to other things and other people so that you can do your work to come to a good conclusion. And that for me was very good to see that you did it and I am happy about it. I am waiting for you here for you to come here to harvest again in the garden with me and go to the fair! We are standing here working!

MA18: So your work with the association was very gratifying. We talked a lot. I mainly managed to get new experiences with you, with your words, when we sat down to talk… we were going through a kind of difficult time that period you came… but it was very gratifying to welcome you to my mother’s house and ours… she never forgets about you she always asks how you are … So we only have good memories, and we get new acquaintances not only me but other women too … They always talk about you. So you marked a lot here with us, the conversations we had. And we are always available for you.

MA33: This research awakens a much greater feeling within us of the value we have as women working in local organizations in the Amazon. […] We have a sense of responsibility – the work we do, the cause we defend – that moves us. Everything that we dream of, we dream together. We dream of a better world, and we are resisting through the means we have. For example, here we live in a country that thinks a lot about capital and capitalism, but does nothing about the people, about human beings, about preserving the Amazon and valuing human beings… I look at myself as part of the Amazon and also value those who fight here […] because we fight ‘the capital’, with what we have: our dreams, our actions of struggle on our daily resistance. Promoting agroecology is also a way to resist because it opposes the agribusiness. Through this research and questions, we manage to see us contributing socially, environmentally, and culturally in the places where we live; our importance and the importance of strengthening other women. Not only on the issue of the impact of agribusiness on our lives, which causes a lot of damage, but also in this fight to combat violence against women – we are violated many times, our rights… We are not only suffering domestic violence, but we suffer political violence in the spaces we occupy. And all this battle, your research helped me to see all this …

5. Conclusion

The most recent women’s movements have been heavily involved in political reflections on the impossibility of separating the process of decolonization from the ‘depatriarchalization’ of thought, knowledge, and structures in Latin America but elsewhere (Verschuur and Destremau Citation2012). For this reason, this research focused on movements, relations, and practices of women in the Amazon that play a fundamental role in resisting ideological, political, economic, and social orders linked to the commodification of land, food, and nature. In addition, women have challenged some traditional social roles, opening new possibilities, and acquiring opportunities with innovation and hope for more sustainable futures. In a setting dominated by pressure and oppression, where large-scale farmers are leading economic, environmental, and social changes, inequalities are being perpetuated. Thus, identification and understanding of women’s role in guaranteeing food, biocultural diversity and bioeconomy are imperative in a world of constant changes and the face of eminent jeopardies of the Amazon forest. Above all, as a final mark, even under the impacts of modernity and the hegemonic socio-economic processes of change, these women keep their cultural and spiritual practices intertwined with nature – moving through and in the borders, oppressed by the colonial matrix of power, becoming and resisting. Ultimately, this article attempts to advance the discussion on transformation to transdisciplinary of transdisciplinary research. It offers one way to think about transformation through the concept of the betweenness – feeling-thinking together, us researchers from academia and our collaborators, researchers from life and allowing all of us into a relational research process, becoming one, every single moment.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the rural women who welcomed us, especially the leading author, who lived in the house of some of them while she was in the Santarém region. We are grateful for their collaboration throughout the process that originates in this article. We recognize that they should participate as co-authors. We are thankful for the greatness of the Amazon rainforest that welcomes and offers everything for free - including knowledge. She is a fundamental part of this research and collaborated with it in different ways. We are indebted to two anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable comments and suggestions on the first version of this manuscript. We are thankful for the Swedish Council for Higher Education (UHR), through the Minor Field Studies (MFS) program, which selected the lead author’s master’s thesis for a grant to cover some of the cost during her fieldwork. We are thankful for the support of the Belmont Forum, NORFACE, and the International Science Council’s T2S Program and the national funders supporting the AGENTS project, in particular FAPESP (Brazil), National Science Foundation (USA), NWO (The Netherlands), and Vetenskapsra°det (Sweden), and to the European Commission through Horizon 2020. We are also thankful for the support of Indiana University’s Emerging Areas of Research program for the project Sustainable Food System Science. We are indebted to the support of all individuals, communities, and organizations who have been collaborating with us in the Amazon. The views and ideas expressed in the paper are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Our intention here is not to create a single group of identities. There is a plurality of identities of women and people who identify as women in the Amazon. Our intention is to present a new perspective in which one cannot talk about these women without inserting them in the context where they live and the practices they do daily – to consider their relations with their places and practices is fundamental to understanding their specific identities, whether indigenous, extractivist, quilombolas, farmer, housewife, etc. When we talk about these women, we are also talking about the Amazon and vice versa – the womanature.

2. This study is part of the AGENTS project ‘Amazonian Governance to Enable Transformations to Sustainability’, which is a research project that aims at documenting, analyzing, and bringing visibility to sustainability-oriented place-based initiatives advancing social and environmental goals in the Amazon region (www.agents.casel.indiana.edu). The project involves collaboration from Indiana University (USA), the University of Campinas (Brazil), the University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands), Stockholm University and the Swedish Agricultural University (Sweden). The leading author participated in this project as a master’s student (Stockholm University), and most of the co-authors took part in the project.

4. This refers to the experience of doing research by being a researcher that sentipensa (Fals-Borda Citation1987), using an abstraction that becomes an experience which allows itself to be shaped, be influenced, and influence. A process that connects us to possibilities that may or may not become our future – those are the means by which the Pluriverse has its solidarity (re-reading Whitehead Citation1929 through the notion of pluriverse).

References

- Adams RT. 2008. Large‐scale mechanized soybean farmers in Amazônia: new ways of experiencing land. Cult Agric. 30(1‐2):32–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-486X.2008.00005.x.

- Almeida J, Udry M. 2019. Sistemas agrícolas tradicionais no Brasil. Área de Informação da Sede-Livro científico (ALICE).

- Alvares MLM, editor. 1995. A mulher existe?: uma contribuição ao estudo da mulher e gênero na Amazônia. Belém (PA): GEPEM.

- Anzaldúa G. 1987. Borderlands: the new mestiza. San Francisco (CA): Aunt Lute Books.

- Barad K. 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Berkes F, Folke C, Colding J, editors. 2000. Linking social and ecological systems: management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511541957.

- Bieling C, Eser U, Plieninger T. 2020. Towards a better understanding of values in sustainability transformations: ethical perspectives on landscape stewardship. Ecosyst People. 16(1):188–196. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2020.1786165.

- Boyatzis RE. 1998. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Brondizio ES, Andersson K, de Castro F, Futemma C, Salk C, Tengö M, Londres M, Tourne DC, González TS, Molina-Garzón A, et al. 2021. Making place-based sustainability initiatives visible in the Brazilian Amazon. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 49:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2021.03.007.

- Chaves FN, de Assis César MR. 2019. O silenciamento histórico das mulheres da Amazônia brasileira. Revista Extraprensa. 12(2):138–156. doi: 10.11606/extraprensa2019.157418.

- Chilisa B. 2017. Decolonizing transdisciplinary research approaches: an African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustain Sci. 12(5):813–827. doi: 10.1007/s11625-017-0461-1.

- Cockburn J, Cundill G, Shackleton S, Rouget M. 2018. Towards place-based research to support social–ecological stewardship. Sustainability. 10(5):1434. doi: 10.3390/su10051434.

- Cockburn J, Rosenberg E, Copteros A, Cornelius SFA, Libala N, Metcalfe L, van der Waal B. 2020. A relational approach to landscape stewardship: towards a new perspective for multi-actor collaboration. Land. 9(7):224. doi: 10.3390/land9070224.

- Coelho-Junior MG, Valdiones AP, Shimbo JZ, Silgueiro V, Rosa M, Marques CDL, Oliveira M, Araújo S, Azevedo T. 2022. Unmasking the impunity of illegal deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: a call for enforcement and accountability. Environ Res Lett. 17(4):041001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac5193.

- Cooke B, West S, Boonstra WJ. 2016. Dwelling in the biosphere: exploring an embodied human–environment connection in resilience thinking. Sustain Sci. 11(5):831–843. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0367-3.

- Cunha MC, ed. 2014. Políticas culturais e povos indígenas: uma introdução. Políticas Culturais e povos indígenas. São Paulo, Brasil: Cultura Acadêmica.

- Cunha MCD, Magalhães SB, Adams C. 2022. Povos tradicionais e biodiversidade no Brasil [recurso eletrônico]: contribuições dos povos indígenas, quilombolas e comunidades tradicionais para a biodiversidade, políticas e ameaças. São Paulo: SBPC.

- Cusicanqui SR. 2018. Un mundo ch’ixi es posible. Ensayos desde un presente en crisis. Buenos Aires: Tinta y Limón.

- Dalazen GB, de Freitas Sia E, Mota CM, Bentes JR, de Barros IBA. 2020. A Avaliação Econômica Do Sistema De Aquaponia Familiar Em Santarém, Oeste Do Pará. Revista Agroecossistemas. 11(2):40–56. doi: 10.18542/ragros.v11i2.9077.

- Denevan WM. 2014. Estimating Amazonian indian numbers in 1492. J Lat Am Geogr. 13(2):207–221. doi: 10.1353/lag.2014.0036.

- Erickson C. 2008. Amazonia: the historical ecology of a domesticated landscape. In: Handbook of South American archaeology. Springer Publisher; p. 157–183. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_11.

- Escobar A. 2016. Thinking-feeling with the Earth: territorial struggles and the ontological dimension of the epistemologies of the south. AIBR, Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana. 11(1):11–32. doi: 10.11156/aibr.110102e.

- Escobar A. 2017. Response: design for/by [and from] the ‘global south’. Des Philos Pap. 15(1):39–49. doi: 10.1080/14487136.2017.1301016.

- Eyster HN, Satterfield T, Chan KM. 2023. Empirical examples demonstrate how relational thinking might enrich science and practice. People Nat. 5(2):455–469. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10453.

- Falcón SM. 2008. Mestiza double consciousness: the voices of afro-Peruvian women on gendered racism. Gender Soc. 22(5):660–680. doi: 10.1177/0891243208321274.

- Fals-Borda O. 1987. The application of participatory action-research in Latin America. Int Sociol. 2(4):329–347. doi: 10.1177/026858098700200401.

- Fals-Borda O. 1991. Some basic ingredients. In: Fals-Borda O, Rahman MA, editors. Action and knowledge: breaking the monopoly with participatory action-research. New York (NY): Apex Press; p. 3–12.

- Fals Borda O, Moncayo VM. 2009. Una sociología sentipensante para América Latina. Buenos Aires: Siglo del hombre.

- Fals-Borda O, Mora-Osejo LE. 2007. Beyond eurocentrism: systematic knowledge in a tropical context. In: Santos BV, editor. Cognitive justice in a global world: prudent knowledges for a decent life. Lanham (MD): Lexigton Books; p. 397–406.

- Fanon F. 2008. Black skin, white masks. New York (NY): Grove press.

- FAO. 2021. Why is gender equality and rural women’s empowerment central to the work of FAO? [accessed 2023 Mar 02]. https://www.fao.org/gender/background/en/.

- Freire P. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York (NY): Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Freitas CT, Espírito-Santo HM, Campos-Silva JV, Peres CA, Lopes PF. 2020. Resource co-management as a step towards gender equity in fisheries. Ecol Econ. 176:106709. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106709.

- Gadotti M. 1996. Pedagogy of praxis: a dialectical philosophy of education. New York (NY): Suny Press.

- Gallegos-Riofrio CA, Zent E, Gould RK. 2022. The importance of Latin American scholarship-and-practice for the relational turn in sustainability science: a reply to West et al. (2020). Ecosyst People. 18(1):478–483.

- Gibbons M. 1999. Science’s new social contract with society. Nature. 402:C81–C84. doi: 10.1038/35011576.

- Grosfoguel R. 2008. Para descolonizar os estudos de economia política e os estudos pós-coloniais: transmodernidade, pensamento de fronteira e colonialidade global. Revista crítica de ciências sociais. 80(80):115–147. doi: 10.4000/rccs.697.

- Hakkarainen V, Mäkinen‐Rostedt K, Horcea‐Milcu A, D’amato D, Jämsä J, Soini K. 2022. Transdisciplinary research in natural resources management: towards an integrative and transformative use of co‐concepts. Sustain Dev. 30(2):309–325. doi: 10.1002/sd.2276.

- Haraway D. 1988. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Stud. 14(3):575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066.

- Hayes A, Lomer S, Taha SH. 2022. Epistemological process towards decolonial praxis and epistemic inequality of an international student. Educ Rev. 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2022.2115463.

- Hertz T, Garcia MM, Schlüter M, Muraca B. 2020. From nouns to verbs: how process ontologies enhance our understanding of social‐ecological systems understood as complex adaptive systems. People Nat. 2(2):328–338. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10079.

- Karam KF. 2004. A mulher na agricultura orgânica e em novas ruralidades. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Estud Fem. 12(1):360. doi: 10.1590/S0104-026X2004000100016.

- Lugones M. 1992. On Borderlands/La frontera. An interpretative analysis. Hypathia. 7(4):31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.1992.tb00715.x.

- Lugones M. 2010. Toward a decolonial feminism. Hypatia. 25(4):742–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01137.x.

- Mancilla García M, Hertz T, Schlüter M. 2020a. Towards a process epistemology for the analysis of social-ecological system. Environ Values. 29(2):221–239. doi: 10.3197/096327119X15579936382608.

- Mancilla García M, Hertz T, Schlüter M, Preiser R, Woermann M. 2020b. Adopting process-relational perspectives to tackle the challenges of social-ecological systems research. Ecol Soc. 25(1): doi: 10.5751/ES-11425-250129.

- Merçon J, Vetter S, Tengö M, Cocks M, Balvanera P, Rosell JA, Ayala- Orozco B. 2019. From local landscapes to international policy: contributions of the biocultural paradigm to global sustainability. Glob Sustain. 2:1–11.

- Mignolo WD. 2007. Delinking: the rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality. Cult Stud. 21(2–3):449–514. doi: 10.1080/09502380601162647.

- Mignolo WD. 2009. Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom. Theory. Theor Cult Soc. 26(7–8):159–181. doi: 10.1177/0263276409349275.

- Mignolo WD. 2011. Geopolitics of sensing and knowing: on (de) coloniality, border thinking and epistemic disobedience. Postcolonial Studies. 14(3):273–283. doi: 10.1080/13688790.2011.613105.

- Mignolo WD, Tlostanova MV. 2006. Theorizing from the borders: shifting to geo-and body-politics of knowledge. Eur J Soc Theory. 9(2):205–221. doi: 10.1177/1368431006063333.

- Moran EF. 1996. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Tropical deforestation: the human dimension. New York (NY): Columbia University Press.

- Moreno-Cely A, Cuajera-Nahui D, Escobar-Vasquez CG, Vanwing T, Tapia-Ponce N. 2021. Breaking monologues in collaborative research: bridging knowledge systems through a listening-based dialogue of wisdom approach. Sustain Sci. 16(3):919–931. doi: 10.1007/s11625-021-00937-8.

- Murrieta R, WinklerPrins A. 2009. ‘I love flowers’: home gardens, aesthetics and gender roles in a riverine caboclo community in the lower Amazon, Brazil. In: Adams C, Murrieta R, Neves W, Harris M, editors. Amazon peasant societies in a changing environment: political ecology, invisibility and modernity in the rainforest. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 259–277.

- Pashby K, Da Costa M, Sund L, Corcoran SL. 2021. Resourcing an ethical global issues pedagogy with secondary teachers in Northern Europe. In Teaching and learning practices that promote sustainable development and active citizenship. IGI Global; p. 47–66. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-4402-0.ch003.

- Quijano A. 2000. Coloniality of power and eurocentrism in Latin America. Int Sociol. 15(2):215–232. doi: 10.1177/0268580900015002005.

- Ross E. 2017. Amazon rainforest was shaped by an ancient hunger for fruits and nuts. Nature News, Springer Nature. 3:2. doi: 10.1038/nature.2017.21576.

- Salles JM. 2022. Arrabalde – Em busca da Amazônia. São Paulo (SP): Cia. Das Letras.

- Sellberg MM, Cockburn J, Holden PB, Lam DP. 2021. Towards a caring transdisciplinary research practice: navigating science, society and self. Ecosyst People. 17(1):292–305. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2021.1931452.

- Smith LT. 1997. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. New Zeeland: Zed Books Ltd.

- Sonetti-González T 2020. Understanding women’s stewardship in the Amazon. A decolonial-process-relational perspective. Master’s thesis. Stockholm. Stockholm Resilience Center. DiVA, id: diva2:1518533.

- Staffa RK, Riechers M, Martín-López B. 2022. A feminist ethos for caring knowledge production in transdisciplinary sustainability science. Sustain Sci. 17(1):45–63. doi: 10.1007/s11625-021-01064-0.

- Stengers I. 2018. Another science is possible: a manifesto for slow science. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons.

- Stenseke M. 2018. Connecting ‘relational values’ and relational landscape approaches. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 35:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.025.

- Turyahikayo E. 2021. Philosophical paradigms as the bases for knowledge management research and practice. Knowl Manag E-Learn. 13(2):209–224.

- Vásquez-Fernández AM, Hajjar R, Sangama MI, Lizardo RS, Pinedo MP, Innes JL, Kozak RA. 2018. Co-creating and decolonizing a methodology using indigenist approaches: alliance with the Asheninka and yine-yami peoples of the Peruvian Amazon. ACME An Int J Crit Infrastruct Geographies. 17(3):720–749.

- Verschuur C, Destremau B. 2012. Féminismes décoloniaux, genre et développement. Revue Tiers Monde. 1(1):7–18. doi: 10.3917/rtm.209.0007.

- Walsh Z, Böhme J, Wamsler C. 2021. Towards a relational paradigm in sustainability research, practice, and education. Ambio. 50(1):74–84. doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01322-y.

- West S, Haider LJ, Stålhammar S, Woroniecki S. 2020. A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst People. 16(1):304–325. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417.

- Whitehead AN. 1929. Process and reality. New York (NY): Simon and Schuster.

- Wilson S. 2001. What is an indigenous research methodology? Can J Native Edu. 25(2):175–180.

- Wynter S. 2003. Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: towards the human, after man, its overrepresentation—an argument. CR. 3(3):257–337.