ABSTRACT

The Tsitsa River catchment is a complex social-ecological system (cSES) in a rural area of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa and the site of the Tsitsa Project (TP); a multi-stakeholder, transdisciplinary landscape restoration project aiming to improve sustainable livelihoods and ecological infrastructure. We investigated transformation mechanisms in a framing of multidimensional linkages, including the recognition of differentiated scales and levels. Linkages were analysed through the development of two vignettes: 1) a citizen technician employed to monitor sediment loads in rivers to inform landscape restoration activities (local scale); and 2) a senior government official responsible for (regional scale) operational and on-the-ground restoration initiatives. Vignette data were generated during a workshop, from TP researcher reflexivity, and interviews with the TP Catchment Coordinator and vignette subjects. Data were analysed and presented: i) as a heuristic diagram, ii) through a narrative, and iii) as a matrix table. Each analysis incorporated a different conceptualisation of scale in relation to four social processes related to transformative change: learning, agency, power and structure. Transformation is demonstrated and leverage points and areas of intractability for promoting and constraining future transformation towards social-ecological sustainability, were identified respectively. Further, we suggest that an understanding of transformative processes was enriched and nuanced by combining a triad of complementary analytical exercises. These allowed a focus on unique stories and contexts, but also the identification of generalisable patterns and mechanisms.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

The magnitude and urgency of social-ecological sustainability challenges facing our planet calls for transformative change (Leach et al. Citation2012; Moore et al. Citation2014). Transformative change is characterised by societal triple-loop learning (Tosey et al. Citation2012), moving from changes in established paradigms (single-loop learning) towards reframing challenging established beliefs (double-loop learning) towards structural change and new ways of knowing, creating meaning and doing (triple-loop learning) (Pahl-Wostl Citation2009).

Researchers are studying transformative mechanisms or change processes in a wide range of social-ecological contexts around the world, including for example, in marine resource management (Gelcich et al. Citation2010; Cinner and Barnes Citation2019), climate change mitigation and adaptation (Macintyre et al. Citation2018; Fedele et al. Citation2019; Colloff et al. Citation2020), agri-food systems (Pesanayi and Weaver Citation2016; Pereira et al. Citation2018; Guerrero Lara et al. Citation2019) and rural development (Oteros-Rozas et al. Citation2019; Flood et al. Citation2022; Tajima et al. Citation2022). These social-ecological systems (SES), (sensu Folke Citation2006; see also Biggs et al. Citation2021; Partelow Citation2018), are characterised specifically by their fundamental complexity (sensu Cilliers Citation2000; Preiser et al. Citation2018), and we designate them as complex social-ecological systems (cSESs). Their problems are characteristically ‘wicked’ (Rittel and Webber Citation1973). We address transformations related to the problems facing an ecologically and socially vulnerable rural landscape in the Eastern Cape of South Africa.

We have chosen to pay particular attention to transformations in boundary zones, where intersectionality, relationality, and interdependencies among and between social and ecological elements of a system, are at play (Palmer et al. Citation2015; Kurian et al. Citation2016). Boundary interactions play a critical role in shaping the resilience, adaptability, and sustainability of cSESs (Preiser et al. Citation2018). Sustainability science and global change cSES research has been critiqued for paying insufficient attention to the social process aspects of transformative change (for example: Cote and Nightingale (Citation2012); Fibinyi et al. (Citation2014); Olsson et al. (Citation2015)). To address this gap, we apply a conceptual framework of four interdependent transformative social processes that can be observed and analysed in cSESs: namely learning, power, agency and structure. Selecting these particular social processes emerged from a larger project of which this research formed part (), and each has a rich lineage of literature. Lotz-Sisitka et al. (Citationunder review) provides a detailed review of the four social process concepts in the context of cSES transformations. Here, we briefly outline how we understand and use the four concepts in our analysis:

Learning: Iterative meaning-making processes that emerge through individual or collective activities within a historical social-cultural-historical context (Engeström et al. Citation2016; Pesanayi and Weaver Citation2016; Lotz-Sisitka et al. Citation2017). We recognise single, double and triple-loop learning (Pahl-Wostl Citation2009).

Power: we draw on Bhaskar’s (Citation2016) concept of power having two forms: the oppressive and/or domination forms of ‘power-over’ (Power-2) and the emancipatory power or capacity of the agent to confront oppressive power to change their situation (Power-1) (Bhaskar Citation2008).

Agency: the ability of a person to act of their own free will. The ‘capacity of persons to transform existing states of affairs (i.e. how things are)’ (Harvey Citation2002, p. 173). We draw on theories of transformative agency, that is developed as people collectively learn how to overcome tensions and contradictions related to their practice (Sannino et al. Citation2016). We also recognise relational agency, enhancing our actions by engaging the capacity of others (i.e. drawing on social capital) (Cleaver Citation2007; Edwards Citation2017).

Structure: Here we again draw on Bhaskar (Citation2016) who explains structures as intersecting patterns of social mechanisms (e.g. social organisation, norms, rules and institutions), that along with natural structures (e.g. the earth, ecosystems and governing laws of physics, chemistry and biology), produce the current configuration of social-ecological systems. Structure manifests from a micro-level of interpersonal relationships to a macro-level of global systems. Structural mechanisms are often the underlying forces driving, for example, ecological tipping points (Milkoreit et al. Citation2018), colonial histories (Glenn Citation2015), geo-politics (Singh and Bourgouin Citation2013), and entrenched capitalist economic systems (Klein Citation2014), which interact to produce the cSES challenges we are now facing. For this study, we primarily focus on the structures in which our research participants were embedded.

Box 1. The research context of this case study (for the full workshop report see Appendix 1).

In addition to the boundaries between social processes, we are attentive to boundaries related to scale – which strongly influences elements and processes in cSESs. Transformation literature emphasises the importance of considering mainly spatial, temporal (Folke et al. Citation2005; Shah et al. Citation2018; Schlüter et al. Citation2019), and to a lesser degree, other scale dimensions (Cash et al. Citation2006) to understand and influence transformative processes in cSESs. Transformative change is therefore multi-scalar (Moore et al. Citation2014). We differentiate scales, and levels within scales (Cash et al. Citation2006; Poteete Citation2012). Scale refers to broad scale categories including eco-spatial, temporal, jurisdictional, institutional, management, networks/relational, and knowledge scale. Levels refer to sub-categories within each broad scale category for example, globe, regions, landscapes and patches are levels within the eco-spatial scale. Similarly, annual, seasonal, quarterly and daily are levels within the temporal scale. Despite the emphasis on the multi-scalar nature of transformation, little has been written on how social processes driving transformation relate to different scale categories and levels. We have constructed an analytical matrix of scales and levels, mapped systematically in relation to the four social processes, and we populated the matrix from the vignette narratives of change from two study-site actors. We show how the matrix can assist in identifying intervention or leverage points (sensu Meadows Citation2009), specific points in a system where relatively less effort could create significant change and support transformation. The leverage points concept helps us to focus on the operational arena, where insights into the transformative social process concepts can enable change.

Rural landscapes are strongly influenced by change at various scales (Huber-Sannwald et al. Citation2012; Flood et al. Citation2022), and our interest is in transformative processes in the rural landscape of the Tsitsa River catchment (‘the catchment’ from here), Eastern Cape, South Africa. The catchment is the site of the Tsitsa Project (TP), a transdisciplinary, social-ecological restoration project, that involves government personnel, researchers, NGOs and communities, who collaborate to improve sustainable livelihoods and ecological infrastructure (Cockburn et al. Citation2018).

We recognise that evidence of transformation in cSESs can be hard to identify, especially since transformation takes time to emerge (Westley et al. Citation2013). Therefore, we have explored a nuanced, more fine-grained exploration of evidence, for example at different scales and levels, in a case study founded on transformative intent. We offer this case from a position of on-going reflexivity and learning as a team working in an embedded way in the landscape. We note the importance of humility and provisionality in knowledge creation processes in cSESs (Palmer et al. Citation2015). In this spirit, we are suggesting that elements of transformation have been initiated in the Tsitsa Project, and we offer a window into an on-going transformation process as it is unfolding.

The purpose of this paper is therefore to contribute to a deeper understanding of transformation in complex social-ecological systems, with a particular focus on the social dimensions of such change processes, and how these are influenced by multiple scales and levels. This paper and the particular focus on the social processes and their role in transformation emerged from broader research process outlined in .

Case and context

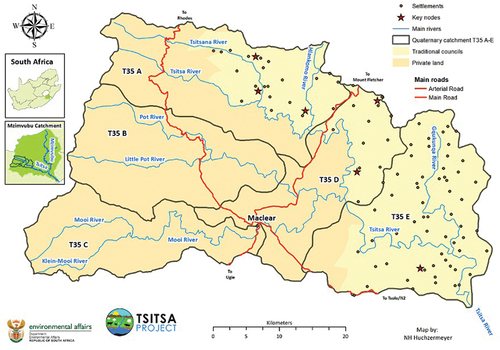

Transformation is an essential characteristic of progress towards a desired future distinctly different from the present (Olsson et al. Citation2014) and is therefore at the heart of the TP vision: ‘to support sustainable livelihoods for local people through integrated landscape management that strives for resilient social-ecological systems and which fosters equity in access to ecosystem services’ (Cockburn et al. Citation2018; Powell et al. Citation2018, p. 84). This is challenging given that the Eastern Cape is one of the poorest provinces of South Africa. The catchment () partly falls within the former Transkei, an area that was allocated for the settlement of black South Africans of Xhosa descent, during Apartheid. The eastern catchment predominantly comprises a rural population dependent on State social welfare, livestock husbandry and small-scale or subsistence farming practices (Hodgson Citation2017). Commercial forestry and farming comprise much of the western area of the catchment. Land and water governance are effected through a system of national, provincial and local government institutions interacting with traditional councils (chiefdoms).

Figure 1. The Tsitsa river catchment comprising five quaternary catchments (T35A-E) approximately half of which is governed under traditional authorities.

The Tsitsa River is a major tributary of the Mzimvubu River, the largest unimpounded river in South Africa. In 2014, the State, through its Department of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation proposed the Mzimvubu Water Project (Le Roux et al. Citation2008) to construct two large dams (not yet built at the time of writing). The project was hailed as a key solution to water supply, alleviating critical poverty, unemployment (job creation through the project) and energy production through hydro-electric power (Department of Water and Sanitation) (Department of Water and Sanitation DWS Citation2016). The catchment landscape is fragile, comprising highly erodible duplex soils (Le Roux et al. Citation2008; Le Roux Citation2018) and degraded grasslands due to a legacy of poor communal rangeland management (Grant and Johnson Citation2019). As a result, there was concern that the proposed dams would silt up prematurely and drastically reduce their lifespan unless efforts were made to restore the ecological infrastructure of the landscape (Cockburn et al. Citation2018; Tsitsa Project Citation2019). Despite the promise of the dams remaining in political rhetoric (recurring State of the Nation Addresses (SONAs)), investment into a research-informed restoration project was initiated by the Department of Environment Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) (Powell et al. Citation2018, p. 84).

The planning and implementation work in the TP is informed by transdisciplinary research led by Rhodes University with some contribution from University of Fort Hare and the University of the Free State. The coordination of catchment-based implementation is managed by an NGO (LIMA) and DEFF’s regional office. Different restoration themes are championed by six working groups, known as communities of practice (CoPs) (sensu Wenger Citation1998): Sediments (biophysical focus on river and landscape health), Grass and Fire (bio-physical focus on grassland condition and social-ecological focus on rangeland management), Livelihoods (social-ecological focus), Governance (political ecology focus on enabling participatory governance capacity), Knowledge and Learning (cross-cutting knowledge management, capacity development and participatory monitoring evaluation reflection and learning), and the Systems Praxis (cross-cutting systems thinking and praxis). Together these CoPs support project activities towards achieving the TP vision.

Methods and approach

This study employed narrative research (Flick Citation2021) as overarching methodology within which vignettes were used as an effective process tracking method to surface data related to transformation. Miles, Huberman and Saldaña describe a vignette as a ‘…focussed description of a series of events taken to be representative, typical, or emblematic [of] the case you are doing’ (Miles et al. Citation2014, p. 81). Narratives, stories, and vignettes have been increasingly used as evidence for understanding environmental governance (Koch et al. Citation2021) and transformation in SESs (Ammann Citation2018; Biggs et al. Citation2021; Ling and Pang Citation2022). Researchers have found these methods to be particularly effective in tracing the intangible processes of transformations, providing rich descriptions of individual experiences and identifying patterns and relationships that may not be apparent through quantitative methods alone (Bercht Citation2021; Koch et al. Citation2021).

Scholars have used vignettes in two main ways. Firstly, as brief hypothetical narratives that portray fictitious characters in specific situations utilised to elicit responses in interviews (Ling and Pang Citation2022). This has proven an effective way to examine people’s attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs, especially in relation to sensitive topics (Hughes and Huby Citation2004). Secondly, and the approach adopted in this study, vignettes have been employed as a storytelling technique for recording data gathered from research in concise depictions or sketches (Blodgett et al. Citation2011). When viewed as narrative depictions, vignettes can serve as a platform for members of a community to have a first-hand say in the research, making it more approachable for those who have a tangible interest in the study (Blodgett et al. Citation2011; Ling and Pang Citation2022). We therefore employed a collaborative vignette method (Miles and Huberman Citation1994), where researchers vignette subjects participated in the co-development, enrichment and validation of vignettes.

Studies in sustainability science and resilience show how the agency and strategic actions of individuals contributes to transformation in cSESs (Fabricius et al. Citation2007; Westley et al. Citation2013; Dias and Partidário Citation2018). We present vignettes of two individuals to demonstrate evidence of transformation catalysed in part by the TP. The data for the case study vignettes were collected sequentially from three sources: 1) group discussions that took place during a WEF Nexus workshop (12–15 November 2019, , Appendix 1); 2) a key informant interview (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2015) with the Tsitsa Project (TP) Catchment Coordinator (referenced below as ‘Interview 1: Nosiseko’); and 3) validation interviews with the vignette subjects (referenced below as ‘Interview 2: Ntombi’, and ‘Interview 3: Mark’).

Group discussions: Tsitsa Project members who participated in the WEF Nexus workshop (see ), including researchers and post-graduate scholars contributed to discussions to develop a first draft of the transformation vignettes. Discussions focussed on gathering examples of each of the four transformative social process concepts, learning, agency, power and structure related to the two vignette subjects. Workshop notes of these collective experience contributions were further developed from the experiential knowledge of authors (20 years of cumulative TP engaged research experience). Identifying how these concepts manifested and related to each other enabled the first draft vignette to be structured as a flowing narrative of transformation for each subject. In a similar manner, a matrix of the Cash et al. (Citation2006) scales and levels, against the four transformative social process concepts, was constructed, and populated from the vignette narratives and the author’s experience of the TP. The matrix enabled us to disaggregate the narrative and then analyse how the elements were related to scale and level. As TP researchers, the authors were directly involved individually or in combinations, in most of the engaged research processes that aimed to shift the Tsitsa River cSES towards the project vision. To mitigate against potential bias to overemphasise evidence of positive transformation in the results, we relied on member checking through validation interviews and critical reflexive practice within the author team and broader project consortium.

Key informant interview: The TP Catchment Coordinator was identified and interviewed as a key informant to further verify and deepen the vignettes. Being embedded in the case study catchment, the Catchment Coordinator had developed strong relationships with the vignette subjects and was familiar with their transformation stories. Draft vignettes developed during the workshop were used in the interview as mirror data (Sannino Citation2015) to validate and stimulate their further development.

Validation interviews: The Catchment co-ordinator, and another co-author presented the analytical table and the narratives, to the two vignette subjects individually. They narrated the observations, memories, and logic from which the table and narratives were built. The vignette subjects both listened carefully and validated, added to, or in the case of one interpretation, slightly softened a critical tone of each component of the analysis.

Research ethics clearance was obtained from the Rhodes University Human Research Ethics Committee (Code: ED18030202).

Developing an iterative analytical lens

Transformation is fundamentally a process of change, a journey through time, space and relationality. Signposts of directional change are at best nuanced and usually obscure – unsurprisingly in non-linear cSES contexts. As researchers, we each experienced our own transformations and were witness to transformations during the Tsitsa Project, that were difficult to ‘pin down’. The first finding in this paper records discovering a way to reveal subtle realities of change.

Drawing on the notion of triangulation (Campbell et al. Citation2020) we followed an emergent process of method-making. The starting conditions in the WEF nexus workshop () included: participants searching to develop relevant case studies; the four social transformation concepts of learning, agency, power and structure and a common understanding of people embedded in landscapes as cSESs. The lemniscate (infinity symbol) was suggested as a heuristic with four identifiable ‘zones’ (top and bottom, left and right) – connected seamlessly, with the inherent possibility of identifying process, points of feedback, and iterative cycling – consistent with cSES thinking (Gunderson et al. Citation2022). We all located the four social transformation concepts to these zones, conscious that their positioning was somewhat arbitrary, but with a broad narrative logic: structure as a reifying slow zone, into which learning acts as a disruptor, encouraging agency, which challenges power – which is reified in structure. We selected narrative as an anchoring starting point and overarching methodology – seeking to elicit nuanced perspectives from personal stories. The idea of ‘vignettes’ offered intimacy and subtlety. We could identify TP participants with contrasting lemniscate ‘footprints’, but we raised the question of scale – how could two small stories reflect transformative potential and reality? This led us to Cash et al.’s (Citation2006) rich analytical framework of scale – also consistent with cSES thinking.

We then used these in an iterative, three-way process that was systemic through following the lemniscate heuristic, and systematic through building the scale matrix, held together by narrative vignettes.

Findings

The 3-way findings

Findings are presented in three ways: 1) as heuristic diagrams (), 2) as narrative vignettes that refer to events in the heuristic diagrams, and 3) as tables () that comprise a structured analysis of the four transformative change processes (learning, agency, power and structure) related to the linked conceptualisations of scale and level.

Figure 2. Vignette 1: the transformation story of Ntombi, a local woman employed as a citizen technician on the Tsitsa Project. A series of events relating to the four concepts of transformation (learning, agency, power and structure) have been included as boxes along the transformative cycle. The events are referred to in the text using codes (V1a–j). Shaded lemniscates indicate/acknowledge historical and future cycles of transformation.

Figure 3. Vignette 2: the transformation story of Mark, a senior manager in the Department of Environment Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) responsible for the operation of the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) in the Tsitsa river catchment. A series of events relating to the four concepts of transformation (learning, agency, power and structure) have been included as boxes along the transformative cycle. The events are referred to in the text using codes (V2a–j). Shaded lemniscates indicate/acknowledge historical and future cycles of transformation.

Table 1. Cross-scale/level analysis of vignette 1: Ntombi. In the analysis, we use the Cash et al. (Citation2006) recognition of levels within scales, as well as multi- and cross-scale interactions, to relate scale to the four social system process elements of structure, learning, agency and power. In each cell, examples at each scale may refer to one of more levels.

Table 2. Cross-scale/level analysis of vignette 2: Mark. In the analysis, we use the Cash et al. (Citation2006) recognition of levels within scales, as well as multi- and cross-scale interactions, to relate scale to the four social system process elements of structure, learning, agency and power. In each cell, examples at each scale may refer to one of more levels.

Each vignette is a distinct ‘transformation story’ unfolding across scales. Vignette 1 is the story of a local woman employed as a Citizen Technician on the TP (). Vignette 2 is the story of the Regional Programme Leader and Chief Directorate of Natural Resource Management in the Eastern Cape (), who is one of the leading figures in the TP. The heuristic diagrams use the infinity or lemniscate symbol to represent the interrelatedness of the four analytical concepts, formulated as ‘change processes’ (sensu Lotz-Sisitka et al. Citationunder review), used to explore transformation. Despite the visual continuity of the lemniscate, we note clearly that learning, the development and enactment of agency, growing and shifting power relations and changes in socio-material structure do not necessarily occur in a specific sequence, nor are transformations linear. Furthermore, while the figures might only hint at temporality, such as the history of learning, agency, power and structure, as well as future shifts and trajectories of transformation, the timeline is a critical scalar aspect of the analysis ().

We conclude the findings section with a synthesis of multi-dimensional insights across the three analytical forms, the vignettes, and the scale and transformation concepts.

An individual capacity development story: from taking water samples for sediment analysis to speaking at an international conference.

The TP provided employment for catchment residents as Citizen Technicians – citizen scientists tasked with collecting and monitoring sediment loads in rivers (Bannatyne et al. Citation2017) (V1a). We provide a vignette of a Citizen Technician, Ntombi and her transformation story (). Ntombi is a respected village resident, well connected into family and community. She isi-Xhosa speaking, with functional English. At the start of the TP, as a housewife with no experience of speaking to groups of people, it would have been hard to imagine her explaining sediment loads in the river to a group of researchers or speaking at an international restoration conference. But she did. The iterative analytical lens scrutinises the domains of transformation in her story, and the connections between them.

As an influential transdisciplinary project with local empowerment and capacity-building intent, the TP created engagement spaces to promote Citizen Technician empowerment through learning. These included but were not limited to: induction training into sediment monitoring, village-level planning workshops and capacity development modules (V1b). Apart from learning the scientific process of sediment monitoring, Ntombi learned about erosion, sediment and the river in the context of the landscape and also to represent the TP in other engagements (Mtati Citation2020). Her social capital (relational agency) amongst fellow Citizen Technicians grew, ‘… they [citizen technician colleagues] are now close to my heart’ (Interview 2: Ntombi). As Ntombi’s knowledge and relational agency increased within the TP, she was increasingly called upon to represent and present the work of Citizen Technicians in workshops and even an international restoration conference (V1d). This empowering journey is related to the intentionally transdisciplinary TP commitment.

Her status of being ‘employed’ provided her with increased recognition, respect and voice among some members of her community (V1c). Ntombi invested money into her family and children’s education (V1d). Some community members viewed her employment with jealousy or mocked her for not showing more signs of her wealth: ‘why did she not have more nice things if she is getting money’ (Interview 1: Nosiseko).

Ntombi’s identity and confidence to engage and have her voice heard (with and by researchers, community members and traditional leaders), no matter how big the crowd or powerful the stakeholders, was further developed through her mastery of her monitoring praxis, engagement in TP activities and her existing and increasing involvement in community processes (traditional headman meetings, acting as the secretary to the headman, church events and funerals) (V1e). Subsequently, when Ntombi did miss an important local meeting, community members would complain about her absence, ‘… we miss your voice’ (Interview 2: Ntombi).

The TP provided more opportunities for Ntombi to unlock, develop and exercise her existing agency (V1f). For example, she engaged actively in planning processes (e.g. decision-making during Village-level Planning Workshops, Climate Change Adaptation Workshops and multi-stakeholder Science Management Meetings), presented at an international conference (Society for Ecological Restoration (SER) Citation2019) and was active in TP advocacy, for example participating in roadshows. Community meetings are traditionally male dominated in amaXhosa societies and characterised by oppressive power relations. Here, only women who are married and confident are heard. Drawing on her growing knowledge capacity, relational and social capital, and agency, Ntombi was able to engage and influence decision-making processes and challenge injustices outside of TP engagements (e.g. raising issues and challenging contentious decisions in headman meetings) (V1g and V1h). ‘Ntombi is the type of person that will stand up for the truth, no matter what other people feel about it’ (Interview 1: Nosiseko). This is evidence of her shifting top-down oppressive power relations towards emancipatory power relations.

The TP as a powerful structure carries a reputation (history of collective experiences), state support, expectations, materials and an extensive community of practice (V1i). The TP can draw people in (perceived opportunity for employment or change) or push people away (disillusioned history of unmet expectations). The TP’s inclusive approach to engagements and promotion of epistemic justice (Fricker Citation2007; German and Taye Citation2008; Glass and Newman Citation2015), challenged (or contrasted with) traditional ways of doing things (formal, rigid structures characterised by oppressive power dynamics) for example, by providing spaces for youth and women to participate in decision-making processes.

From managing alien invasive plant clearing to becoming a state-community mediator ensuring benefits from land restoration to local people.

The TP arose out of the opportunity to apply a national Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) for landscape restoration (http://www.epwp.gov.za/) in the Tsitsa River catchment. The EPWP is a government initiative aimed at creating job opportunities for unemployed individuals through public sector projects. The resulting TP has the complex aim of initiating and supporting change towards restored landscape systems, that better support local livelihoods and well-being (Cockburn et al. Citation2018). Mark is a senior operations manager in DEFF, responsible for ensuring EPWP activities proceed efficiently. Mark is bilingual in isi-Xhosa and English, with isi-Xhosa as his home language. He has a background in natural science, and at the start of the TP had a focussed commitment to efficient landscape restoration through clearing alien vegetation to increase river flow, and surface-based erosion control. His work was administratively complicated, with clear benchmarks of areas cleared and restoration structures in place. There was little room for social awareness, or recognition of the links between restoration and livelihoods – beyond the base-level paid to EPWP workers. He became responsible for connecting EPWP activities with TP research. At the start of the TP, it would have been hard to imagine Mark with a passionate interest in local livelihoods and the holistic well-being of catchment residents. illustrates the vignette of Mark, and his transformation story.

DEFF has a long history of using EPWP in landscape restoration, mainly through clearing alien invasive plants (Powell et al. Citation2018) (V2a): Mark is the senior civil servant in the Eastern Cape Province with responsibility for the operational efficiency of EPWP. The benefit of EPWP has historically simply been in terms of area of aliens cleared, and hours of work remunerated. The TP explicitly links EPWP national and regionally organised activities to the local people. Restoration investment in the TP was initially envisaged as large-scale, high-cost construction of gabions in large erosion gullies upstream of the proposed dam with little emphasis on local benefits.

Early in the TP, one engagement with local communities focussed on the collaborative development of a local Catchment Management Strategy for the Tsitsa River Catchment, through a series of workshops, using an Adaptive Planning Process (APP) (Palmer et al. Citation2018; Palmer and Munnik Citation2018) (V2b). The APP workshops were designed to lay a foundation for the emergence of local participatory governance capacity.

Mark attended two APP workshops and became frustrated that participants spent a lot of time questioning the proposed dam, when he (representing DEFF) was interested in restoration (V2c). There was a tension between his motive (a workshop focussing on restoration) and those of the community members (multiple motives, including those related to benefits and grievances about the proposed dam). He lost confidence in the governance engagement process. Nonetheless, Mark engaged with this tension by persevering through his active involvement in the TP (V2c+). He asked the TP Governance Research Community of Practice to engage with operational teams across the province to explore making TP learning more practically aligned with DEFF EPWP operations. With the encouragement of the National Operations Director, a cSES and APP learning workshop (Kingsford and Biggs Citation2012) was held for civil servants from three regions, one of them the Eastern Cape.

DEFF has regular Management, Research and Planning (MaReP) meetings. At the 2016, TP-focussed MaReP, Mark strongly supported a call for the DEFF Natural Resource Management Directorate to formally commit to processes of engagement and learning with local communities (V2d): This was a key moment of change and transformation that was enabled by Mark engaging with tension evidenced during the first APP workshop. A beautiful moment of transgressive change occurred when an operational manager read a poem he had written about his discomfort with the deep problems faced by EPWP workers. Poems are not a usual MaReP phenomenon.

A conscious change of attitude toward the involvement of local people resulted in Mark using his position to influence communication patterns and act as the linking agent for the TP – particularly between TP researchers, DEFF operational civil servants, restoration implementers, other government agencies, local traditional leaders and the national Head Office of the DEFF Natural Resources Management Directorate (V2e). For example, TP research that analysed the consequences of remuneration practices drew attention to the difficulties faced by participants in EPWP, and suggested pathways to improved practice (Wolff et al. Citation2019).

At this generative point, cycles of learning began to unlock agency (V2f). Several TP research Communities of Practice collaborated in integrated landscape planning, linked to the emergence of both participatory governance and diverse livelihoods. A TP Catchment Coordinator was appointed leading to active facilitation of a growing collaborative TP network. Mark continued to play a central connecting role in aligning EPWP operations with the TP. Regular engagement with the Catchment Co-ordinator was key to active responsiveness.

Local needs started to have a greater influence on the location and form of EPWP activities (V2g): Staff from the organisations that locally implement EPWP work attended TP learning events and engaged in integrated spatial planning. Most recently, six local people were employed as Catchment Liaison Officers. They work actively between the TP and local residents.

However, the national DEFF is a large powerful government structure that is slow to change. (V2h): Mark has had limited success in ensuring efficient, timely EPWP payments to workers (this issue was reemphasised in the validation interview (Interview 3: Mark)). So, while at the TP scale there is support and responsive flexibility, there is no evidence of national government levers having engaged with transformative change, halfway through a 10-year project. DEFF is at the centre of TP power-relations (V2i): The TP and EPWP are both governed by DEFF. There has been slow change in improved benefit to local people from EPWP employment and faster change in benefit directly from TP (local residents employed in various monitoring positions with benefits that outweigh those accrued from EPWP employment).

Multi-dimensional insights across vignettes, scales, and transformative concepts

The detailed analytical work presented in enables a focus on inter- and intra-scale linkages in transformative processes. This focus is valuable both in understanding transformative processes and informing action to intervene at leverage points in the system to promote transformative change. However, looking at the scales separately through the table leaves these frictions between the scales somewhat out of sight, as does the separate presentation of the two vignettes. We now tie the analysis together by identifying three multi-dimensional insights which cut across the vignettes, scales and transformative concepts, illustrating them with examples.

Firstly, not all scales are equally important in terms of transformation: this analytical approach is useful in helping researchers to ask, ‘When is which scale important and why?’

In this analysis, we have made the multiple different scales and levels explicit which allows an easier ‘contextual check’ of which scales and levels might be important for transformation, as was evident in each vignette. For example, in Vignette 2, it becomes apparent that a key focus of Mark’s work is to actively manage the landscape across eco-spatial scales, jurisdictional scales and management scales, while needing to also account for temporal, institutional and knowledge scales in terms of decision-making. Mark clearly needs to bring together multiple resources and sectors under the banner of ‘landscape restoration’. Following the three-way analysis, we see the complexity of his role. The vignette notes: ‘His work was administratively complicated, with clear benchmarks of areas cleared and restoration structures in place. There was little room for social awareness, or recognition of the links between restoration and livelihoods’. In , at the intersection of Learning and the Knowledge scale, Specific level, Mark addresses the link between restoration practice and both ecological and social wellbeing. The learning translates to agency at point V2d (), where Mark is deeply affected by emerging narratives about the difficulties experienced by restoration workers when payment processes are interrupted. His personal agency is mobilised to engage with EPWP payment processes.

We are also able to identify ‘sticking points’: for example, the intractable barriers of DFFE bureaucracy which resist the realisation of true benefits at the Local level – Jurisdictional scale; and ‘positive leverage points’: for example, the Eco-spatial scale as a framing for the TP, which brought actors across Jurisdictional and Knowledge scales together into transformative learning process.

Exploring interlinkages between and within scale serves to highlight both intractable barriers and opportune transformative leverage points both of which are important in supporting transformation in cSES contexts.

Secondly, if we want to understand transformative processes in cSESs, then we need to have a more nuanced understanding of the role that individuals play at various dimensional linkages among scales.

We see that Ntombi and Mark’s work in the TP required them to engage as individuals and within collectives across levels within several scales including the eco-spatial (e.g. monitoring sediment at the patch level, contributing to landscape-level planning), the jurisdictional (participating in local institutional processes, engaging in national-level meetings and conferences). If they had stayed within their original ‘level’ within one or two scales, the transformative processes they are a part of would have been much less likely to begin unfolding. This highlights the role of catalytic individuals, or boundary spanners, who are able to traverse scales- and levels.

For example, Mark’s narrative in Vignette 2 revealed a gap between research and operations and a subtle transformation linking them. Mark’s transformation and agentive role as a boundary spanner occurred when he first recognised the importance of communities (in particular, considering community voice) in supporting and sustaining landscape restoration processes (1st ‘aha’ moment and learning, see V2e). This realisation came from paying attention to researchers and in acknowledging that (2nd ‘aha’ moment and learning, see V2c+), and as a result, he increased his support of research processes in the TP. This is an example of how learning was catalysed by active engagement with a tension or contradiction – namely the tension between Mark’s initial motive for engagements to focus only on restoration activities, and the inclusive intent of the APP workshops that recognised multiple and diverse motives of community members often unrelated to restoration activities.

Thirdly, the scale concepts are linked differentially to the transformation concepts – some scales interlink more strongly with particular transformation concepts and vice versa.

We see evident links between: the institutional scale and structure; the eco-spatial, jurisdictional, and knowledge scales with learning; the networks/relational and knowledge scales with agency; and the jurisdictional and management scales with power. The temporal scale influences pervasively, linking and influencing all aspects of transformation.

To further unpack this insight, we focus on the points where the eco-spatial, jurisdictional, and knowledge scales interlink, which is where transformative learning is most likely needed and takes place. It is at the interlinkage points between these three scales that we are able to identify intractable barriers as well as intervention points likely to yield high impact. It is around these intervention or leverage points where learning is needed (e.g. see Cockburn et al. (Citation2018)). Furthermore, by looking at these interlinkage points as a function of multiple scales and levels, we gain a deeper insight into how they operate in the system. However, this is made difficult by the very different nature of scales. Eco-spatial scales are empirically connected without gaps and are an easily understandable organising scale (e.g. rivers are connected across landscapes, sediment processes occur from upstream to downstream, erosion from high to low elevation, etc.). However, there is a patchiness and fluidity in social scales (e.g. patchiness of urban settlements, of knowledge, of management action, etc.). This patchiness is not often in sync with bio-physical elements and processes which creates a tension between these two scales, exemplified in the widely recognised difficulty of addressing sustainability challenges associated with cSESs (van Oosten Citation2013). Therefore, bringing together the scales and the four concepts deepens our analysis of these challenges.

For example, in Ntombi’s narrative in Vignette 1 (), we see specific interlinkages in how Ntombi’s bio-physical practice of monitoring sediment linked with social processes (e.g. participation in learning spaces and agency development and enactment to influence TP project level processes at a Management scale). In the TP, despite deep understandings of the bio-physical (e.g. sediment movement) and social processes (e.g. participatory governance), there remains a gap in our understanding of the interlinkages and relationships between these processes. However, we recognise that it is in these gaps that transformative learning is likely occurring (e.g. Ntombi’s learning about sediment movement was deeply linked into her learning and agency development about her role in the project and the community). Therefore, paying attention to and directing interventions into these gaps holds potential to support transformation in the catchment.

Discussion

Transformation in the Tsitsa Project

Complex sustainability challenges emanate from the intersection of land, water and livelihoods in the Tsitsa River catchment. Local community residents are variously reliant on natural resources from the landscape for water, energy (firewood) and food needs (Sigwela et al. Citation2017). In the communal part of the catchment, social grants, wages (e.g. from EPWP work), and cash remittances play a significant role in providing financial income to households, but there is still significant reliance on the landscape for water, energy and food needs. In the privately owned, commercial part of the catchment, residents and farmers generate income from farming activities reliant on land and water resources, and the economies in small local towns are reliant on the agricultural industry.

The two cross-level vignettes from the Tsitsa Project offer insights into transformation processes in the context of cSESs. Ntombi and Mark are both directly involved in natural resource management activities that seek to address sustainability challenges related to landscape restoration and livelihood development. Ntombi is employed to monitor sediment loads in the rivers to inform landscape restoration activities, and Mark manages a large landscape restoration initiative actively implementing on-the-ground restoration initiatives. What we see from their stories as told in the vignettes, is that to bring about the ambitious vision of the Tsitsa Project, transformation within the cSES is necessary and is starting to emerge. Where these early signs of transformation are emerging is significant: they are located in the boundary zones, tensions, and interlinkages between different scales and levels, resource interests and stakeholders, knowledge forms, etc. This supports the supposition laid out by (Lotz-Sisitka et al. Citationunder review), that studying transformative processes within cSESs offer important opportunities for research and learning and beyond that, highlight leverage points for intervention and change (Meadows Citation2009; Fischer and Riechers Citation2019).

Not only do the vignettes show that there is value in studying and supporting transformative processes within the cSESs, but it is also clear from Ntombi’ and Mark’s stories, that it is within the boundaries between levels and scales that the deepest challenges are located, offering the most important opportunities for learning and change. We have previously argued that the Tsitsa Project team are ‘navigating a bumpy terrain of dialectic tensions’, i.e. tensions between different knowledge systems, between power differentials, and between the different interests and cultures of participating stakeholders (Cockburn et al. Citation2018, p. 1). The vignettes presented here demonstrate that this metaphor still holds in the Tsitsa Project and that understanding and supporting the change processes in these boundary zones (Lindley and Lotz-Sisitka Citation2019) or zones of tension is key. Tension in these zones should not be conflated with ‘conflict’ in the adversarial sense, which undermines collaborative effort towards transformation (Fienitz and Siebert Citation2022). Rather, tensions are ‘conflicts of motive’ between actors that if engaged with may catalyse expansive learning and transformative agency (sensu Engeström Citation2017). Moreover, the two vignettes come together at the regional/landscape levels, showing special potential for the boundary spaces at this level of Eco-spatial Scale in which to catalyse transformation. Below we further discuss the (1) interlinkages of the two vignettes at these levels, after which (2) we unpack the design of learning spaces when bringing people into learning-oriented conversation in new configurations. Finally, we reflect on (3) the methodological contribution of this study, i.e. the value of combining different analytical tools to develop a deeper and more nuanced understanding of transformation, is discussed.

Interlinkages between levels and vignettes

Ntombi and Mark’s stories are primarily located at a specific level (within the Eco-spatial Scale), from which they move into other levels where they interlink. At the Eco-spatial Scale, Ntombi’s story is primarily located at the patch/landscape level, but through her engagement with the TP, she has become involved at landscape, regional and even global levels. Mark’s story is primarily located at a landscape/regional level and through his engagements with the TP, he has come to have a more direct interaction at the patch/landscape and at regional and global levels. The two vignettes therefore interlink at the landscape/regional level. The bringing together of people by the TP at this level has created tensions which are important learning opportunities (Cockburn et al. Citation2018) and has created space for transformative power and agency to emerge. Similar interlinkages of levels, and resultant pockets of transformation, are evident within other scales including: Jurisdictional (with the formation of novel governance configurations); Management (through integrated landscape restoration planning processes); and Networks/Relational (through knowledge networks cross-level social capital growth (Cockburn et al. Citation2020)) scales.

Two particular practices also emerge as critical at the landscape/regional level. Firstly, the bottlenecks in payment of local people for EPWP work (and work in the TP), and the inherent bureaucratic challenges which make this a contentious and ethical challenge. Secondly, the creation and facilitation of various learning platforms by TP researchers has brought people together in new configurations. The payment system is both empowering and disempowering: while the work opportunities in the TP have catalysed Ntombi’s agency and transformative power, the payment bottlenecks caused by the bureaucratic system of state financial management are evidence of deep structural constraints which are deeply disempowering to local people reliant on this source of income. Mark’s story shows a recognition of the importance of working more closely and respectfully with local people, including paying them more reliably for their work, but responding to this is difficult because of structural constraints – a gap between insight and enacted transformation. What we see here are important interplays between agency, power and structure across scales/levels, and the potential of learning processes as facilitated by the TP as a transdisciplinary research intervention to a) surface these interplays and tensions, and b) potentially create windows of opportunity to start addressing the deep structural constraints.

The learning platforms facilitated by the TP supported the emergence of hybrid governance formations. Hybrid governance formations combine hierarchical, traditional and other decentralised and adaptive forms of governance structures together to support a more integrated and dynamic approach to address sustainability challenges (Pahl-Wostl Citation2015, Citation2019). For example, the TP has facilitated multi-stakeholder engagements and learning within annual/bi-annual Science-Management Meetings, so-called ‘B-team meetings’ which bring various local and provincial government officials together; regional integrated planning meetings for natural resource management and restoration; and village-level integrated planning meetings for natural resource management and restoration. Multi-stakeholder learning platforms have potential to bring about transformation as shown in Mark’s story and in other contexts (Kuenkel Citation2019). Limitations to convening and the function of these platforms also exist. It is difficult to get stakeholders together across the large Eco-spatial scale of the project, cross-stakeholder learning spaces are difficult to facilitate, and the learning processes can be slow and resource-intensive. These appear to be recurring challenges in large-scale transdisciplinary research interventions (Mutahara et al. Citation2020; Horcea-Milcu et al. Citation2022), particularly in African contexts (Shackleton et al. Citation2023). Despite these difficulties, the active engagement of stakeholders in these events and processes indicates the need for, and interest in, bringing together of people in new configurations. We discuss the importance of design and facilitation of such spaces in further detail below.

Design of learning spaces when bringing people into learning-oriented conversation in new configurations

The design of learning spaces, when bringing local people, researchers, and Natural Resource Management officials into learning-oriented conversation, in new ways/configurations, is important. Certain characteristics of these spaces have made them fertile learning environments. Careful and strong facilitation is required: to be sensitive and inclusive of local traditions (e.g. opening engagements with a song and/or a prayer), to take account of different languages (ensure translation), to intentionally build a common understanding of relevant terminology (Palmer et al. Citation2022), to temper dominant actors (e.g. powerful government officials and senior researchers) (Herrero et al. Citation2018), and to be alert to, and actively draw in quieter voices. Incorporating diverse pedagogical approaches (e.g. balancing conventional knowledge transfer media presentations and reports) with creative forms of social learning facilitation (role-playing, embodied learning and arts-based expression and learning) is required to foster social learning among people with different ways of knowing and educational levels (Wals et al. Citation2009). Treating different ways of knowing and forms of knowledge (e.g. scientific knowledge and local knowledge) equally is key to promoting epistemic justice (Fricker Citation2017) and strengthening the adaptive approaches required for sustainability pathways (Williams et al. Citation2020). The TP design approach fosters trust and enables people to feel safe to open up and share diverse views. The TP has attempted to formalise these characteristics and principles to guide the design and facilitation of its engagements (Weaver et al. Citation2019). Although effective for promoting transformation, to authentically work in this manner is a slow and time-consuming process (Palmer et al. Citation2021; Horcea-Milcu et al. Citation2022).

Besides learning and agency development, ongoing interactions in these spaces have built social capital in the form of relational agency, trust and knowledge networks – all of which are critical to formalising governance structures and decision-making (Stern and Baird Citation2015; Rapp Citation2020). There is potential for these emergent learning structures to serve as incubators of hybrid governance structures (Pahl-Wostl Citation2019).

It is inevitable that new and diverse configurations of people co-operating on complex sustainability challenges will bring about conflicts of motives and tensions. Tensions are manifestations of underlying contradictions (Engeström Citation2017) and are real opportunities for learning and change (Sannino et al. Citation2016; Sannino and Engeström Citation2018). Careful design of learning spaces (e.g. drawing on the theory of expansive learning and the principle of double stimulation (sensu Sannino Citation2015)) to actively surface contradictions, challenge entrenched unstainable practices and collectively interrogate and design ways to overcome these contradictions can stimulate expansive learning, transformative agency and reconfigured practices (Engeström Citation2011; Sannino et al. Citation2016).

Methodological contributions

To study and enable transformations in cSESs, requires an acknowledgement of reality as complex, which has important methodological implications (Palmer et al. Citation2015; Preiser et al. Citation2018). One of these implications is that insights and understanding of systems emerge from different perspectives and different kinds of knowledge, i.e. a pluralistic orientation to knowing and navigating systems is necessary (van Kerkhoff Citation2014). Moreover, analyses ought to be multi-dimensional, to avoid the pitfalls of narrow analyses (Poteete Citation2012).

We therefore intentionally used three different forms of analysis to develop a more comprehensive, multi-dimensional understanding of two transformative processes occurring in the TP, drawing directly on the knowledge and experience of key actors in the system through the development of vignettes. The visual heuristics provide an overview of the transformation pathways and interrelating concepts of learning, agency, power and structure. The narrative provides a flowing story that personalises the transformation process for the reader. Lastly the tables, which form an analytical matrix between scale concepts and transformation concepts, bring some of the complexity back into the analysis and are key to deepening the analysis by explicitly linking scale and transformation concepts to the vignettes.

This is a potentially useful methodological contribution to cSES research, because the unpacking, and re-packing, of the multiple scales helps us to systematically unpack the intertwined nature of the cSESs. This unpacking has enabled a tracking of nuanced change processes across agency, learning, power and structure, and a systemic navigating of transformation pathways, as they unfold across levels and scales of complex systems. Moreover, the process itself was of value to participants, particularly the development and validation of vignettes. Indeed, transdisciplinary research strives for deep inclusion of non-academic actors beyond problem framing and outcomes assessment (Osinski Citation2021). Through the vignette validation process, we found that the participants appreciated the process. It enabled them to step back and see the value and transformative potential of their work. Both vignette subjects and we, as researchers, played a role in shaping the TP’s vision. The validation was therefore, not only of the data and findings of the vignettes, but of the work being done towards achieving TP vision.

A final reflection on the potential methodological contribution we offer here is an acknowledgement of the preliminary and incomplete nature of this analysis, and with that, the value of ‘a certain slowness’ (Cilliers Citation2006) in engaging with cSES issues. We see this as an initial step to understanding and supporting transformation in the TP, as part of creating enabling conditions for transformation to take place, recognising that it can be slow, iterative, non-linear, and hard to see and track. We have attempted an analysis that is both multi-dimensional and deep, which has enabled us to identify both intractable barriers to and leverage points for transformation (Abson et al. Citation2017).

While there is a certain urgency that comes with the depth of sustainability challenges facing humanity, there is also immense value in slower processes of analysis and change, as noted by Cilliers (Citation2006, p. 2): ‘A slower approach is necessary, not only for the survival of certain important values or because of romantic ideals, but also because it allows us to cope with the demands of a complex world in a better way’. We suggest that our study has resulted in a rich and emergent outcome from the analytical attention we have paid to the multiple dimensions of scale and transformation.

Conclusion

The need to understand and enable transformative processes in cSESs is widely acknowledged. Yet analytical tools to conduct research and support change processes in such complex, transdisciplinary, and multi-dimensional contexts remain limited. In this study, we sought to explore transformations in boundary zones between social processes (learning, power, agency and structure), and scales. Having worked in a complexity-aware manner, we have i) presented empirically derived insights on how multiple scales, and the levels within them, influence transformation processes; and ii) developed a nuanced analytical method for illuminating interlinkages between concepts of scale, and concepts of transformation.

We developed the analysis in a co-constructive manner, starting with narrative vignettes of two local actors, involved in a landscape restoration initiative, whom we regarded as catalytic individuals. By structuring narrative vignettes concurrently through both the TP timeline and interactions between four social processes, we arrived at two stories of transformational change. Ntombi, moved from being a conventional village person, to becoming a skilled citizen-technician, who was able to speak into spaces right up to an international conference. Mark moved from the baseline of being an operationally focussed bio-physical manager, to becoming someone thinking in a more integrated manner with a real social concern for livelihoods. Vignette narratives structured through the combination of the TP project timeline and the four interacting social processes revealed the value of studying and supporting transformative processes within cSESs. We then added the further boundary dimension of scales and their various levels. A matrix of scales versus social processes, populated from the timeline – social process narratives, produce a map of intersecting influences on transformation. It became clear that boundary zones between social processes, and between levels and scales, were indeed the locations of deep challenge, and concomitantly provided transformational opportunity. We conclude that if transformation is a goal of an intervention, then it is vital to pay careful attention to boundary zones in the configuration, design and facilitation of learning processes.

Moreover, we found that not all scales are equally important in terms of transformation and suggest that this analytical approach is useful in helping researchers to ask, ‘When is which scale important and why?’ The analysis also showed that scale concepts are linked differentially to the transformation concepts, i.e. that some scales interlink more strongly with some of the transformation concepts, and vice versa.

We suggest that our analytical approach has highlighted the importance of tracing and understanding the multi-dimensional linkages among and between scales, levels and social processes, providing texture to the bumpy terrain (sensu Cockburn et al. Citation2018) of a transformative process in a cSES. The resultant nuanced grasp of the transformational terrain can guide identifying entry points for interventions that aim to support change.

Appendix

Download PDF (885.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2023.2278307

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abson DJ, Fischer J, Leventon J, Newig J, Schomerus T, Vilsmaier U, von Wehrden H, Abernethy P, Ives CD, Jager NW, et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio. 46(1):30–20. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Ammann M. 2018. Leadership for learning as experience: introducing the use of vignettes for research on leadership experiences in schools. Int J Qual. 17(1):160940691881640. doi: 10.1177/1609406918816409.

- Bannatyne LJ, Rowntree KM, van der Waal BW, Nyamela N. 2017. Design and implementation of a citizen technician–based suspended sediment monitoring network: lessons from the Tsitsa river catchment, South Africa, Water SA. South Afr Water Res Commission. 43(3):365–377. doi: 10.4314/wsa.v43i3.01.

- Bercht AL. 2021. How qualitative approaches matter in climate and ocean change research: uncovering contradictions about climate concern. Global Environ Change. 70. Art. 102326. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102326.

- Bhaskar R. 2008. Dialectic: the pulse of freedom, dialectic: the pulse of freedom. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. doi: 10.4324/9780203892633.

- Bhaskar R. 2016. Enlightened common sense: the philosophy of critical realism. Mervyn Hartwig editors. Kindle. Oxon: Routledge.

- Biggs R, de Vos A, Preiser R, Clements H, Maciejewski K, Schlüter M. 2021. The Routledge handbook of research methods for social-ecological systems. Routledge.

- Blodgett A, Schinke RJ, Smith B, Peltier D, Corbiere R. 2011. In indigenous words: the use of vignettes as a narrative strategy for capturing aboriginal community members’ research reflections. Qual Inq. 17(7):1–12. doi: 10.1177/1077800411409885.

- Campbell R, Goodman-Williams R, Feeney H, Fehler-Cabral G. 2020. Assessing triangulation across methodologies, methods, and stakeholder groups: the joys, woes, and politics of interpreting convergent and divergent data. Am J Eval. 41(1):125–144. doi: 10.1177/1098214018804195.

- Cash DW, Neil Adger W, Berkes F, Garden P, Lebel L, Olsson P, Pritchard L, Young O. 2006. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecol Soc. 11(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-01759-110208.

- Cilliers P. 2000. What can we learn from a theory of complexity? Emergence. 2(1):23–33. doi: 10.1207/S15327000EM0201_03.

- Cilliers P. 2006. On the importance of a certain slowness, E: CO emergence. Complexity Organ. 8(3):105–112. doi: 10.1017/S0012217300015043.

- Cinner JE, Barnes ML. 2019. Social dimensions of resilience in social-ecological systems. One Earth. 1(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.08.003.

- Cleaver F. 2007. Understanding agency in collective action. J Human Dev. 8(2):223–244. doi: 10.1080/14649880701371067.

- Clifford-Holmes JK, Palmer CG, de Wet CJ, Slinger JH. 2016. Operational manifestations of institutional dysfunction in post-apartheid South Africa. Water Policy. 18(4):998–1014. doi: 10.2166/wp.2016.211.

- Cockburn J, Palmer C, Biggs H, Rosenberg E. 2018. Navigating multiple tensions for engaged praxis in a complex social-ecological system. Land. 7(4):129. doi: 10.3390/land7040129.

- Cockburn J, Rosenberg E, Copteros A, Cornelius SF, Libala N, Metcalfe L, van der Waal B. 2020. A relational approach to landscape stewardship. Land. 9(7):224. doi: 10.3390/land9070224.

- Colloff MJ, Wise RM, Palomo I, Lavorel S, Pascual U. 2020. Nature’s contribution to adaptation: insights from examples of the transformation of social-ecological systems. Ecosyst People. 16(1):137–150. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2020.1754919.

- Cote M, Nightingale AJ. 2012. Resilience thinking meets social theory, progress in human geography. Prog Hum Geogr. 36(4):475–489. SAGE Publications, Sage UK: London, England. doi: 10.1177/0309132511425708.

- Dias J, Partidário M. 2018. Mind the gap: the potential transformative capacity of social innovation. Sustainability. 11(16):4465. doi: 10.3390/su11164465.

- [DWS] Department of Water and Sanitation. (2016). Invitation to submit written comments in terms of section 110 of the National Water Act 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) on the proposed Mzimbubu Water Project and the environmental impact assessment relating thereto. South Africa: Gov Gaz. p. 12. [accessed 2020 July 24]. www.gpwonline.co.za.

- Edwards A. 2017. Working relationally in and across practices: a cultural-historical approach to collaboration, working relationally in and across practices: a cultural-historical approach to collaboration. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316275184.

- Engeström Y. 2011. From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory Psychol. 21(5):598–628. doi: 10.1177/0959354311419252.

- Engeström Y. 2017. Formative interventions for global needs: towards second generation change laboratories (CL-2). Helsinki: CRADLE, University of Helsinki.

- Engeström Y, Sannino A, Bal A, Lotz-Sisitka H, Pesanayi T, Chikunda C, Lesama MF, Picinatto AC, Querol MP, Jin Lee Y. 2016. Agentive learning for sustainability and equity: communities, cooperatives and social movements as emerging foci of the learning Sciences. In: The International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS); p. 1048–1054. [accessed 2018 Nov 10]. https://repository.isls.org/bitstream/1/372/1/165.pdf.

- Fabricius C, Folke C, Cundill G, and Schultz L. 2007. Powerless spectators, coping actors, and adaptive co- managers: a synthesis of the role of communities in ecosystem management. Ecol Soc. 12(1):29. [online]. doi: 10.5751/ES-02072-120129.

- Fedele G, Donatti CI, Harvey CA, Hannah L, Hole DG. 2019. Transformative adaptation to climate change for sustainable social-ecological systems. Environ Sci Policy. 101:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.07.001.

- Fibinyi M, Evans L, Foale SJ. 2014. Social-ecological systems, social diversity, and power: insights from anthropology and political ecology. Ecol Soc. 19(4):28. doi: 10.5751/ES-07029-190428.

- Fienitz M, Siebert R. 2022. “It is a total drama”: land use conflicts in local land use actors experience. Land. 11(5):602. doi: 10.3390/land11050602.

- Fischer J, Riechers M. 2019. A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 1(1):115–120. doi: 10.1002/pan3.13.

- Flick U. 2021. An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

- Flood K, Mahon M, McDonagh J. 2022. Everyday resilience: rural communities as agents of change in peatland social-ecological systems. J Rural Stud. 96:316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.11.008.

- Folke C. 2006. Resilience: the emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob Environ Chan. 16(3):253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002.

- Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 30(1):441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511.

- Fricker M. 2007. Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001.

- Fricker M. 2017. Evolving concepts of epistemic injustice. In: Kidd IJ Medina J, and Pohlhaus G Jr, editors. Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice. Routledge; p. 53–60. [accessed 2020 July 27]. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/110047/http://www.routledge.com/[email protected]://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/.

- Gelcich S, Hughes TP, Olsson P, Folke C, Defeo O, Fernández M, Foale S, Gunderson LH, Scheffer M, Steneck RS, et al. 2010. Navigating transformations in governance of Chilean marine coastal resources. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 107(39):16794–16799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012021107.

- German L, Taye H. 2008. A framework for evaluating effectiveness and inclusiveness of collective action in watershed management. J Int Dev. 20(1):99–116. doi: 10.1002/jid.1430.

- Glass RD, Newman A. 2015. Ethical and epistemic dilemmas in knowledge production: addressing their intersection in collaborative, community-based research. Theory Res Educ. 13(1):23–37. doi: 10.1177/1477878515571178.

- Glenn EN. 2015. Settler colonialism as structure, sociology of race and ethnicity. Social Race Ethnicity. 1(1):52–72. SAGE PublicationsSage CA: Los Angeles, CA. doi: 10.1177/2332649214560440.

- Grant R, Johnson R. 2019. Grazing and fire management plan phase 1 TSITSA PROJECT.

- Guerrero Lara L, Pereira LM, Ravera F, Jiménez-Aceituno A. 2019. Flipping the tortilla: social-ecological innovations and traditional ecological knowledge for more sustainable agri-food systems in Spain. Sustainability. 11(5):1222. doi: 10.3390/su11051222.

- Gunderson LH, Allen CR, Garmestani AG, editors. 2022. Applied panarchy: applications and diffusion across disciplines. Washington: Island Press.

- Harvey DL. 2002. Agency and community: a critical realist paradigm, journal for the theory of social behaviour. John Wiley Sons, Ltd. 32(2):163–194+i. doi: 10.1111/1468-5914.00182.

- Herrero P, Dedeurwaerdere T, Osinski A. 2018. Design features for social learning in transformative transdisciplinary research. Sustain Sci. 15(2):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0641-7.

- Hodgson DL. 2017. Demographic change in the upper Tsitsa Catchment: the integration of census and land cover data for 2001 and 2011 [ Master’s thesis]. Rhodes University.

- Horcea-Milcu A, Leventon J, Lang DJ. 2022. Making transdisciplinarity happen: Phase 0, or before the beginning. Environ Sci Policy. 136:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2022.05.019.

- Huber-Sannwald E, Palacios MR, Moreno JTA, Braasch M, Peña RMM, Verduzco JGDA, Santos KM. 2012. Navigating challenges and opportunities of land degradation and sustainable livelihood development in dryland social–ecological systems: a case study from Mexico. Phil Trans R Soc B. 367(1606):3158–3177. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0349.

- Hughes R, Huby M. 2004. The construction and interpretation of vignettes in social research. Soc Work Soc Sci Rev. 11(1):36–51. doi: 10.1921/17466105.11.1.36.

- Kingsford RT, Biggs HC. 2012. Strategic adaptive management guidelines for effective conservation of freshwater ecosystems in and around protected areas of the world. Sydney: IUCN WCPA Freshwater Taskforce, Austrailian Wetlands and Rivers Centre.

- Klein N. 2014. This changes everything: capitalism vs. the climate. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Koch L, Gorris P, Pahl-Wostl C. 2021. Narratives, narrations and social structure in environmental governance. Glob Environ Chan. 69:102317. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102317.

- Kuenkel P. 2019. Stewarding sustainability transformations in multi-stakeholder collaboration. In: Stewarding sustainability transformations. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-03691-1_6

- Kurian M, Ardakanian R, Gonçalves Veiga L, Meyer K. 2016. Institutions and the Nexus approach. In: Resources, services and risks. SpringerBriefs in environmental science. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28706-5_2

- Leach M, Rockström J, Raskin P, Scoones I, Stirling AC, Smith A, Thompson J, Millstone E, Ely A, Arond E, et al. 2012. Transforming innovation for sustainability, ecology and society. Resilience Alliance. 17(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-04933-170211.

- Le Roux JJ. 2018. Sediment yield potential in South Africa’s only large river network without a dam: implications for water resource management. Land Degrad Dev. 29(3):765–775. doi: 10.1002/ldr.2753.

- Le Roux JJ, Morgenthal TL, Malherbe J, Pretorius DJ, Sumner PD. 2008. Water erosion prediction at a national scale for South Africa. Water SA. 34(3):305–314. doi: 10.4314/wsa.v34i3.180623.

- Lindley D, Lotz-Sisitka H. 2019. Expansive social learning, morphogenesis and reflexive action in an organisation responding to wetland degradation. Sustainability. 11(4230):4230. doi: 10.3390/su11154230.

- Ling HL, Pang MF. 2022. A vignette-based transformative multiphase mixed methods interventional study featuring venn diagram joint displays: financial education with Hong Kong early adolescent ethnic minority students. J Mix Methods Res. 16(1):130–149. doi: 10.1177/1558689821989834.

- Lotz-Sisitka H, Mukute M, Chikunda C, Baloi A, Pesanayi T. 2017. Transgressing the norm: transformative agency in community-based learning for sustainability in southern African contexts. Int Rev Educ. 63(6):897–914. doi: 10.1007/s11159-017-9689-3.

- Lotz-Sisitka H, Pahl-Wostl C, Meissner R, Scholtz G, Cockburn J, Stuart-Hill S. under review. Towards qualitative cross case analysis of transformative processes in the face of resource Nexus challenges.

- Macintyre T, Lotz-Sisitka H, Wals A, Vogel C, Tassone V. 2018. Towards transformative social learning on the path to 1.5 degrees. Curr Opin Env Sust. 31:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.003.

- Meadows DH. 2009. Thinking in systems: a primer. Vermont: Earthscan.

- Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ. 2015. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. 2014. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. In: 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

- Milkoreit M, Hodbod J, Baggio J, Benessaiah K, Calderón R, Calderón-Contreras C, Donges JF, Mathias J-D, Rocha JC, Schoon M, et al. 2018. Defining tipping points for social-ecological systems scholarship—an interdisciplinary literature review. Environ Res Lett. 13(3):33005. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaaa75.

- Moore ML, Tjornbo O, Enfors E, Knapp C, Hodbod J, Baggio JA, Norström A, Olsson P, Biggs D. 2014. Studying the complexity of change: toward an analytical framework for understanding deliberate social-ecological transformations. Ecology And Society. 19(4). doi: 10.5751/ES-06966-190454.

- Mtati N. 2020. Towards realising the benefits of citizen participation in environmental monitoring: a case study in an Eastern Cape natural resource management programme [ Master’s thesis]. Rhodes University.

- Mutahara M, Warner JF, Khan MSA. 2020. Multi-stakeholder participation for sustainable delta management: a challenge of the socio-technical transformation in the management practices in Bangladesh. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 27(7):611–624. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2020.1722278.

- Olsson P, Galaz V, Boonstra WJ. 2014. Sustainability transformations: a resilience perspective. Ecol Soc. 19(4):1. doi: 10.5751/ES-06799-190401.

- Olsson L, Jerneck A, Thoren H, Persson J, O’Byrne D. 2015. Why resilience is unappealing to social science: theoretical and empirical investigations of the scientific use of resilience, science advances. Am Assoc Adv Sci. 1(4):e1400217. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400217.

- Osinski A. 2021. Towards a critical sustainability science? Participation of disadvantaged actors and power relations in transdisciplinary research. Sustainability. 13(3):1266. doi: 10.3390/su13031266.

- Oteros-Rozas E, Ravera F, García-Llorente M. 2019. How does agroecology contribute to the transitions towards social-ecological sustainability? Sustainability. 11(16):4372. doi: 10.3390/su11164372.

- Pahl-Wostl C. 2009. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob Environ Chan. 19(3):354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001.