ABSTRACT

The social and cultural elements of human interactions with nature remain among the least-studied and least understood elements of social-ecological systems. Although the conceptual framework of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) provides an entry point into assessing nature’s contributions to people (NCP), at face value IPBES has limited capacity to capture subjective elements of values and culture as influences on important socio-cultural processes that underpin social-ecological interactions. We propose that integrating cultural ecosystem services more explicitly into the IPBES conceptual framework can help fill its existing gaps by 1) elucidating the social-cultural mechanisms that underpin the production and valuation of non-material NCP, 2) explaining the role of heterogeneity in cultural, social and environmental processes, 3) identifying the two-way interactions between nature and people that co-produce NCP, and 4) identifying synergies between the IPBES conceptual framework and the cultural ecosystem services approach that will facilitate the application of the IPBES framework in more diverse settings. We use recently published work on cultural ecosystem services associated with birds to illustrate our suggestions in action. Assessing social-ecological systems through this adapted framework makes implicit connections easier to draw out, thereby providing holistic insight into the feedbacks and linkages that should be considered at all levels of environmental decision-making.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

As natural systems become increasingly threatened by global changes induced by anthropogenic activities, efforts to understand the complex relationships between people and nature have become a global priority. As a result, there has been a rapid expansion of frameworks and knowledge networks that explore sustainable interactions between social and ecological systems (Borie and Hulme Citation2015). One of the dominant influences on social-ecological systems approaches over the last two decades has been the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA). The MA described social-ecological interactions through the lens of ecosystem services, defined as the innate characteristics, functions or processes of the environment that produce benefits that contribute to human wellbeing (Daily Citation1997; MA Citation2005).

Ecosystem benefits can be measured in numerous ways (e.g. through economic, ecological and socio-cultural values), but economic metrics have been the primary method for communicating information about ecosystem services and promoting environmental considerations in policy agendas (Costanza et al. Citation2017; Anderson et al. Citation2022). The dominant rationale for quantifying nature in economic terms has been that it facilitates the inclusion of natural values in economic decision-making; it is often argued that if ecosystem goods and services are not measured in economic terms, they will not be sufficiently included in economic decisions that have environmental impacts. For example, the true costs of forest loss may be much higher than the timber value of the trees if services such as climate regulation and water production are included in the analysis. However, the use of economic metrics has also been criticised for promoting an anthropocentric, utilitarian perspective on people’s relationships with nature that ignores intrinsic and relational values (Chan et al. Citation2012; Schröter et al. Citation2014; Costanza et al. Citation2017).

Biophysical and, to a lesser extent, socio-cultural approaches to valuing nature have become more prevalent, especially due to recent criticisms (Anderson et al. Citation2022). These criticisms argue that relying solely on economic valuations of ecosystems undermines sustainability and biodiversity efforts by overlooking vital subjective values and cultural aspects (e.g. a sense of place) that underpin human reliance on ecosystems but are challenging to quantify in economic assessments (Pascual et al. Citation2023). Cultural ecosystem services are particularly at risk of being disregarded given that their contribution to the non-material benefits people obtain from ecosystems are often difficult to evaluate. These benefits include spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation and aesthetic experiences (Haines-Young and Potschin Citation2012). Non-monetary approaches for describing the relationships that define social-ecological systems have therefore sought to address the under-representation of the interactions that drive dynamic feedbacks between and within social-ecological systems (Masterson et al. Citation2019).

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) was initiated in 2012 to strengthen the interface between science and policy to promote the sustainable use of biodiversity and further its contributions to human wellbeing (Díaz et al. Citation2015). One of the major advances of IPBES was the production of a novel conceptual framework for evaluating and communicating social-ecological dynamics. This framework brought social-ecological systems thinking into the mainstream by producing policy-relevant knowledge on the contributions of nature to society; and critically, by exploring the context-specific social and environmental parameters that regulate these contributions (Borie and Hulme Citation2015, Díaz et al. Citation2015; Kenter Citation2018).

Recent iterations of the IPBES conceptual framework specifically seek to address perceived limitations associated with ecosystem service-related frameworks (e.g. MA, Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) (Haines-Young and Potschin Citation2012)) by expanding on the concept of ecosystem services to emphasize ‘nature’s contributions to people’ (NCP) in recognition of a need for a broader framing of people’s relationship with nature (Kenter Citation2018; Maes et al. Citation2018). In the IPBES conceptual framework, NCP are situated as a conduit between nature and good quality of life, and defined as ‘all the contributions, both positive and negative, of living nature to people’s quality of life’ (Pascual et al. Citation2017; Díaz et al. Citation2019). IPBES identifies two conceptual approaches for reporting NCP: the generalising perspective and the context-specific perspective. The generalising perspective provides standardised reporting categories of 18 NCP, which broadly encompass regulating, material and non-material NCP (Díaz et al. Citation2018). By contrast, the context-specific perspective is intended to be fit-for-purpose and ensures that conservation and management efforts are contextually appropriate and consider the unique characteristics of each ecosystem and the needs of local communities (Díaz et al. Citation2018). Combining these perspectives through an interwoven approach (Hill et al. Citation2021) enables global trends in NCP production to be explored within specific contexts that generate distinct knowledge systems and worldviews. Implicit in these approaches is the recognition that the importance a person ascribes to NCP is strongly influenced by that individual’s perceptions, shared beliefs, customs, behaviours, worldviews and knowledge systems; and that these are produced through socio-cultural co-construction (Bennett et al. Citation2016; Fischer and Eastwood Citation2016; Brondizio et al. Citation2019).

Since its conceptualization, the IPBES conceptual framework has supported significant advances in our understanding of social-ecological systems, and has been applied to promote the equitable distribution of NCP (Chaplin-Kramer et al. Citation2019; Schröter et al. Citation2020), improve understanding of landscape-scale decisions (Ellis et al. Citation2019; Topp et al. Citation2021) and encourage deeper insight into important links between local knowledge systems, governance and biodiversity management (Tengö et al. Citation2017) among other inclusive and interdisciplinary uses (Hill et al. Citation2021).

Despite these important contributions to our understanding of human-nature interactions, the conceptual reframing of ecosystem services as NCP has also been contentious and the benefits of the IPBES conceptual framework over previous alternatives have been questioned (Braat Citation2018; de Groot et al. Citation2018; Faith Citation2018; Maes et al. Citation2018; Peterson et al. Citation2018). Among the specific concerns raised about the IPBES conceptual framework is the limited incorporation of explicit feedbacks from society to nature and from nature to society that contribute to people’s quality of life (Peterson et al. Citation2018; Mastrángelo et al. Citation2019). As a result, the framing of ‘nature’s contributions to people’ may underemphasize the multi-directional flow of interactions between nature and people, suggesting that social-ecological feedbacks are not fully incorporated in the IPBES conceptual framework (O’Connor and Kenter Citation2019). Moreover, while an individual’s social-cultural context is widely recognised as a critical influence on the production of NCP, these interactions are not explicitly located within causal diagrams of the IPBES conceptual framework and rather, are assumed to underpin all interactions between people and nature (Kenter Citation2018). As a result, important, complex social-cultural-ecological interactions may be under-represented in these assessments (Muradian and Gómez-Baggethun Citation2021).

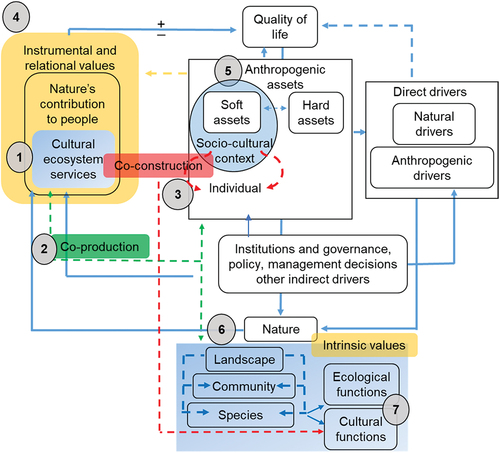

Understanding the intersection between the ecosystem services concept and the IPBES conceptual framework – two perspectives that have both been critiqued for missing elements – is critical in advancing our understanding of social-ecological systems. We propose that integrating cultural ecosystem services into the IPBES conceptual framework more explicitly can help fill existing gaps in the IPBES framework without losing the valuable knowledge developed through the MA/CICES ecosystem services approach. Important gaps that this approach can fill include 1) elucidating the social-cultural mechanisms that underpin the production and valuation of non-material NCP, 2) explaining the role and importance of heterogeneity in cultural, social and environmental processes, 3) identifying the two-way interactions between nature and people that co-produce NCP, and 4) identifying synergies between the IPBES conceptual framework and the cultural ecosystem services approach that enable the application of the IPBES conceptual framework in more diverse settings. We first present and explain the additions that we found it necessary to make to the IPBES conceptual framework in order to specifically link cultural ecosystem services with the IPBES framework. These are informed by current literature, and empirical support for the proposed modifications is outlined in . We then use our series of recent analyses describing the cultural ecosystem services associated with birds as a case study to show how the modifications that we have used can be operationalized to provide deeper insights into social-ecological dynamics.

Table 1. Details of the additions made to the IPBES framework to integrate cultural ecosystem services, the gaps these additions may fill and mechanisms and examples of these concepts. The numbers in the Table correspond to the numbers in .

Figure 1. Modified IPBES framework for exploring social-ecological interactions associated with cultural ecosystem services. This framework amends and elaborates on eight components and linkages: (1) cultural ecosystem service; (2) co-production; (3) co-construction; (4) ecosystem values; (5) anthropogenic assets (hard and soft); (6) nature; and (7) ecological and cultural functions. Further detail on each of these 7 elements is provided in .

Unifying nature’s contributions to people and cultural ecosystem services

The IPBES conceptual framework offers a useful entry point for presenting important linkages and interactions between social and ecological systems that goes beyond a simple representation of the flow of benefits from ecological systems to social systems (MA Citation2005; Díaz et al. Citation2015). In traditional cascade-model assessment, the benefits that cultural ecosystem services deliver to people are challenging to quantify as they do not conform to traditional economic or ecological metrics (Chan et al. Citation2012), and consequently are often overlooked or underestimated (Cheng et al. Citation2019). In contrast, the IPBES conceptual framework is well positioned to improve integration of the cultural benefits people receive from nature via non-material NCP and explicit pluralistic valuation processes (Díaz et al. Citation2015; Pascual et al. Citation2023). However, there are persistent knowledge gaps for integrating cultural benefits into assessments, which limits our understanding of their contributions to human well-being and sustainable development. Indeed, a recent assessment by IPBES (Pascual et al. Citation2023) found that the cultural perspectives (i.e. perspectives embedded in an individual’s socialization) that are critical for describing non-material NCP are frequently overlooked. We propose a modified framework that maps cultural ecosystem services onto the IPBES conceptual framework ( and ). While this approach is rooted in a context-specific perspective, we argue that the explicit inclusion of concepts like co-production (i.e. the interaction between social and ecological systems that produce NCP) and co-construction (i.e. the interaction between individuals and their society that affect their held values) (Fischer and Eastwood Citation2016), are also critical in making the distinction between the benefits that non-material NCP provide and the socio-cultural contexts that drive demand for these contributions. Explicit inclusion of these concepts also enables the generalizing perspective associated with IPBES to be woven together with context-specific perspectives (Hill et al. Citation2021). Integrating cultural ecosystem services with the IPBES conceptual framework makes it easier to explore the mechanisms that underpin socio-cultural perspectives and interrogate critical issues for biodiversity and human wellbeing. This perspective piece is thus not positioned as a critique of the IPBES conceptual framework, but rather, presents an attempt to explore how gaps identified in the IPBES conceptual framework can be approached through the cultural ecosystem services perspective. Drawing out implicit connections relating to the provision of cultural ecosystem services promotes a more holistic understanding of human-nature interactions that produce NCP within the IPBES conceptual framework.

IPBES’ conceptual framework serves as a broad analytical and conceptual tool that can be applied as a boundary object for place-based research (Virapongse et al. Citation2016), and as such, was designed to be generic and generalizable. Some of the most critical additions to the IPBES framework that we found necessary in order to fully incorporate cultural ecosystem services included (1) recognising an important additional linkage between anthropogenic assets, nature, and its subsequent effect on NCP; (2) connecting co-construction and co-production; (3) greater recognition of the relevance of culture and socio-cultural context (including soft assets such as values, norms, beliefs and traditions, place attachment, and the types of knowledge people hold) as influences on the importance ascribed to environmental and ecological elements; and (4) explicit recognition of the connections between quality of life, governance, and nature. The modifications made to the framework, and the logic underlying them, are explained in more detail in .

Operationalising the combined framework using birds as a case study

The cultural ecosystem services provided by birds in South Africa offer a useful case study with which to explore our modified assessment framework. South Africa is a highly diverse country in both social and ecological realms. Birds are prevalent and conspicuous, and hold high cultural significance in different ways for different communities. South Africa’s birdlife is highly diverse, with 856 species recorded, 68 of which are endemic (Taylor Citation2018). Birds in South Africa, contribute regulating (e.g. pest control and waste decomposition), provisioning (e.g. supply of food, pollination) and cultural services (e.g. aesthetics, religious beliefs) (Sekercioglu Citation2006; Cox et al. Citation2018).

Zoeller et al (Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022, Citation2023) used an adaptation of Q-factor analysis (Stephenson Citation1953) to evaluate peoples’ perceptions of the cultural traits that underpin cultural ecosystem services provided by birds. Specifically, 401 socio-economically diverse ecosystem users in South Africa were asked to rank a random selection of 30 bird species on a scale of 1–10, and then identify the traits of species that contributed to their score (see Table S1 for a list of these traits). This score was used to quantify intangible benefits associated with birds, and the traits identified by respondents provided insight into the cultural functions that underpin cultural ecosystem service production. This research was undertaken under a classical Millennium Assessment/CICES-type cultural ecosystem services paradigm, which we then attempted to integrate more tightly with the IPBES conceptual framework.

In the following discussion we use the numbering sequence presented in and and outline (1) the gaps the modified framework addresses within the context of case study, (2) the specific application of the addition in our example, and (3) how considering this addition is relevant to the IPBES agenda.

Cultural ecosystem services

Understanding the intersection between the ecosystem services approach and the IPBES conceptual framework clarifies how social-ecological interactions produce cultural ecosystem services in a culturally diverse society. The relevance of cultural diversity for outcomes of interest (e.g. human wellbeing or choices about environmental management) depends on how, where, and when cultural differences result in differences in human-nature interactions. Evaluating human-nature interactions through the lens of cultural ecosystem further enables the relational nature of these interactions to be established. In this context, we adopt the typology of human-nature relational models proposed by Muradian and Pascual (Citation2018), which, in part, stresses that understanding different social-cultural contexts that underpin human nature relationships is crucial. Ignoring cultural differences has been recognised as a considerable risk within IPBES conceptual framework (Díaz et al. Citation2018), but relevant distinctions are seldom included in assessments (Dunkley et al. Citation2018). For example, differences in views of owls as either providers of pest control services or birds of ill omen may lead to proactive management for owls (e.g. nest box provision or reductions in rodenticide use) on one hand or persecution of owls (poisoning, nest destruction) on the other, with consequences for human health via rodent-carried diseases such as Toxoplasmosis.

Co-production

In our modified framework, the cultural ecosystem services provided by birds arise through an interaction between anthropogenic assets and nature that contributes to quality of life via co-construction and subsequently co-production (, point 2). Intra-system interactions will be explored in greater detail under co-construction and anthropogenic assets (i.e. social systems), and nature (i.e. ecological systems).

Incorporating co-production expands the current representation of NCP production as unidirectional in the IPBES conceptual framework. It makes it easier to unpack different components of social and ecological systems, identify gaps related to the two-way interactions between social and ecological systems, and explore how heterogeneity in each system influences co-production of NCP.

The critical role of social-ecological interactions in the co-production of NCP is widely recognised, and has given rise to the concept of People’s Contributions to Nature (PCN). PCN asserts that people play a vital role in shaping ecosystem dynamics and as such, need to be explicitly included in assessments of NCP (Larson et al. Citation2023). While many existing approaches provide important local or regional information on the cyclical relationship between NCP, PCN and co-production, a thorough understanding of these social-ecological processes is sparse in regions with limited representation in the IPBES assessment (e.g. sub-Saharan African and Eastern Europe) (McElwee et al. Citation2020). Including co-production in the modified framework also supports exploration of the secondary top-down influences of institutional perspectives in managing the relationship between nature and human well-being. This can provide important insight into the production of NCP in different contexts and at different scales. For example, Zoeller et al. (Citation2022) found that the co-production of cultural ecosystem services associated with birds is informed by specific scales and levels in ecological systems, and by identification with specific socio-cultural constructs in social systems (Zoeller et al. Citation2021). Specifically, 401 bird species provided six ‘cultural functions’ that underpin non-material NCP, such as aesthetic experiences, connection to place and cultural experiences. These traits include visual traits, negative visual and behavioural traits, movement and ecological traits, place association and abundance indicators, common traits and behavioural traits (Table S1). Different traits resonated with different socio-demographic groups of people; suggesting that the NCP associated with these traits were co-produced both from variation in human community in social systems, and variation in landscapes, communities and species in ecological systems () (Zoeller et al. Citation2022).

Co-construction

Integrating differences in views, traditions and culture into assessment frameworks facilitates a deeper understanding of heterogeneity in how people and nature interact, and whether or how it matters (Muradian and Pascual Citation2018). To understand human-nature interactions through this relational approached, it is thus critical to assess the interaction between individuals and their society that influence how they relate to nature through their values. This interaction is commonly referred to as co-construction. Acknowledging social-ecological diversity and heterogeneity is a critical tenet of the IPBES conceptual approach, and has been advocated for across numerous assessments over multiple years (Borie and Hulme Citation2015; Díaz et al. Citation2019; Pascual et al. Citation2023). Indeed, a priority aim for IPBES is to include knowledge systems of indigenous people and local communities in their assessments (McElwee et al. Citation2020); and the influence of cultural context on perceptions of cultural ecosystem services has been demonstrated (Kilonzi and Ota Citation2019), providing important insights into shared underlying values. Including explicit feedbacks that capture heterogeneity in cultural context is thus essential to achieve the aims and outcomes set out by IPBES.

One approach for including heterogeneity in the IPBES conceptual framework is to disaggregate ecosystem users based on socially constructed subgroups to account for the potential influence of coconstruction on the way people value ecosystem services (Lele et al. Citation2013; Lau et al. Citation2018). Accounting for co-construction is particularly important in a multicultural country like South Africa, which recognises 11 official languages and four distinct self-identified ethnic groups: Black (80.6%), Coloured (i.e. person of mixed ancestry) (8.7%), Indian/Asian (2.5%) and White (8.1%) (Census Citation2011). Given this socio-cultural heterogeneity of South Africa’s population, it is critical to understand how social-cultural contexts informs people’s relationship with nature to promote equitable management of natural systems. When disaggregating individuals according to their age, gender, race, language, and education, Zoeller et al. (Citation2021) found significant variation in how people value cultural traits associated with birds (Figure S1). Their results suggested that the coproduction of cultural ecosystem services and the coconstruction of their values are mediated by socio-cultural constructs (Scholte et al. Citation2015; Fischer and Eastwood Citation2016). Integrating co-construction of values has been identified as critical for progressing the IPBES agenda of including local knowledge systems into their assessments (Anderson et al. Citation2022; Termansen et al. Citation2022) and this can be facilitated using the integrated approach outlined in this paper (, point 3). For example, disaggregating ecosystem users according to key markers of their identify to better understand their social-cultural context can elucidate how they might interact with their environment and how that interaction co-produces NCP (Muradian and Pascual Citation2018).

Values

Understanding how and why human values for ecosystems are formed is of critical importance to the IPBES agenda (Pascual et al. Citation2023). In a recent assessment, IPBES emphasized the need to incorporate culture and its influence on values in their conceptual framework to mitigate against the detrimental effect of evaluating nature through purely economic or biophysical measures (Pascual et al. Citation2023). Cultural underpinnings were recognized as critical in how values are formed through their contribution to the value hierarchy – that is, that specific values of nature and NCP are nested within broad values (guiding life principles), which are informed by worldviews (the lens through which the world is perceived via co-construction with cultural traditions and languages) (Anderson et al. Citation2022), enabling diverse perspectives to guide plural valuations of nature (Hill et al. Citation2021). However, explicit links between the co-construction of worldviews and their influence on values have not yet been captured, despite recognition of the importance of these links. For example, Schroter et al. (Citation2021) developed indicators to capture relational values associated with physical and psychological recreational experiences that are fundamental to quality of life and identified the importance of cultural diversity in evaluating NCP, but cultural context was not explored in detail.

To explore how values are formed from a cultural ecosystem services perspective, we highlighted in Point 2 that the cultural ecosystem services associated with birds are co-produced, which in turn is influenced by the co-construction of held values (Jones et al. Citation2021; Zoeller et al. Citation2021). This suggests that co-construction is a critical filter for understanding assigned values, as represented in . Moreover, since cultural ecosystem services are strongly aligned with non-material contributions to people, understanding their influence on quality of life relies on capturing pluralistic values that reflect elements of cultural identity (Pascual et al. Citation2023).

Zoeller et al. (Citation2020) described a novel approach for capturing value pluralism by assessing the values people assign to the cultural traits associated with bird species using socio-cultural valuation methods. These values correspond with different dimensions of specific values (i.e. relational, instrumental and intrinsic). For example, they found that traits associated with a species inherent ecology (e.g. flight, foraging behaviour and adaptability) were assigned significantly higher values than traits that produced a negatively perceived relational value (specifically, negative visual and negative behavioural traits) and traits that produced instrumental values (such as food). Since the values people assigned to bird species differed according to key elements of an individual’s identity (described in Section 3), it is critical that ecosystem values are understood through the lens of individuals’ specific socio-cultural characteristics. Addressing ecosystem values in this way contributes to the growing body of research that recognizes the critical importance of including plural values and diverse worldviews and knowledge systems in assessing nature’s contributions to people (Pascual et al. Citation2023).

Anthropogenic assets (hard and soft)

Under the IPBES framework, anthropogenic assets are an umbrella term used to describe all of humanity’s capital, including built infrastructure, knowledge, technology and financial assets (Díaz et al. Citation2015). However, grouping together all anthropogenic assets risks minimising the extent to which nuanced social processes influence the co-production of NCP (Bruley et al. Citation2021). As a result, the relative contributions of different social components within anthropogenic assets are often not rigorously assessed. To address this, we divided anthropogenic assets into their hard and soft components (Anderies et al. Citation2004) (, point 5). In so doing, we were able to identify that soft assets (i.e. values, norms, beliefs and tradition, place attachment and the type of knowledge people hold) are critical in co-producing cultural ecosystem services (Zoeller et al. Citation2021). Conversely, hard assets, such as infrastructure, did not appear to affect how people valued cultural ecosystem services associated with birds since there were no differences in ecosystem service values among individuals who lived at different locations along a rural-urban gradient of decreasing infrastructure (Zoeller et al. Citation2021). While the relationship between urban-rural location and how people assign values to ecosystems needs to be tested in other systems to explore the generality of these findings, with other studies showing differences between urban and rural valuation (Lapointe et al. Citation2020), it is evident that separation of hard (e.g. infrastructure) and soft (e.g. place attachment) elements of the environment is necessary in the IPBES conceptual framework to understand the weighted contributions of both to NCP co-production.

Nature

The IPBES conceptual framework recognizes that nature is inherently complex and comprises diverse organisms that interact at different scales and levels (Diaz et al. Citation2015). The complexity of nature is regarded as valuable in and of itself, and does not require human-driven processes to realise its intrinsic value (Díaz et al. Citation2015, Topp et al. Citation2021). This approach departs from traditional ecosystem services framing, which focuses on safeguarding the sustainable provision of nature’s services to people, and not the conservation of nature for nature’s sake (Schröter et al. Citation2014). By overlaying cultural ecosystem services onto the IPBES conceptual framework, we can identify connections between the complexity of nature that exists to support internal biophysical processes, and human-driven processes that produce NCP (, point 6). However, the links and trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services and their interaction with social systems have not been well documented (Kosanic and Petzold Citation2020), and the term nature itself has been criticised for underestimating the extent to which natural systems and social systems interact and influence each other (Peterson et al. Citation2018). Understanding and managing the dependence of social systems on natural systems supports sustainable interactions between people and nature (Turner Citation1997; Clark and Harley Citation2020), and feedbacks between these systems have been identified as a persistent gap in the IPBES framework (Mastrángelo et al. Citation2019).

Approaching this gap through the cultural ecosystem services perspective clarifies the critical role that ecological and social complexity play in the production of benefits that people receive from nature. Zoeller et al. (Citation2022) found that benefits that appear to be linked to species and communities are in fact produced from multi-level (birds to ecosystems) and multi-scale (site to landscape) interactions. Consequently, management initiatives that that aim to safeguard processes that contribute to NCP also need to consider cascade effects on other NCP over multiple levels and scales. These findings provide evidence that the co-production of cultural ecosystem services associated with birds is dependent on feedbacks between multi-scale and multi-level variation in ecological systems and different components of anthropogenic assets in social systems. Exploring the relative weight of each component in social-ecological interactions is critical in future IPBES assessments to identify specific feedbacks between social and ecological systems (Mastrángelo et al. Citation2019).

Ecological and cultural functions

Ecosystem functions underpin complex processes that contribute to people’s quality of life (de Groot et al. Citation2002). The critical role of ecological functions has been widely recognised since the popularisation of community ecology (Bellwood et al. Citation2019), but the importance of cultural functions has received limited attention. Cultural functions represent a critical interface between social and ecological systems, and understanding the mechanistic and cultural processes supporting their production is necessary to improve the aim of the IPBES framework of integrating a diverse range of knowledge systems and stakeholders. This claim can be tested and operationalised using birds as a case in point.

Birds provide a diverse range of ecosystem functions (Sekercioglu Citation2006). The identification of these functions has enabled bird species to be allocated into specific functional groups, traditionally inferred from their diet (Sekercioglu Citation2006, Cumming and Child, Citation2009). For example, frugivores are categorised according to their primary function of seed dispersal (Sekercioglu Citation2006). However, birds also provide a range of cultural functions that are not captured in traditional functional assessments. Using a database of avian cultural traits identified by ecosystem users, Zoeller et al. (Citation2020) explored whether a consistent typology of cultural functional groups could be developed. They found strong evidence for cultural functional groups that identify clusters of subjective human response to species traits. These groupings reflect both the species themselves and the socio-cultural systems that influence human perceptions. Social systems clearly exert an important influence on human perceptions of ecological systems and on management actions, but these feedbacks are not explicitly incorporated into IPBES frameworks. The addition of cultural functional groups to the IPBES framework can offer important insights into how the interactions between social and ecological systems produce cultural functions, and the indirect effects that anthropogenic processes have on governance and management of natural resources.

Discussion

We have shown how mapping cultural ecosystem services onto the IPBES framework can contribute usefully to the development of more rigorous approaches to measuring and evaluating important social-ecological interactions. Drawing on principles from the IPBES conceptual framework, the ecosystem services concept and ancillary literature, we suggest an approach to social-ecological assessments that incorporates important feedbacks and mechanisms that have not previously been explicitly integrated. The IPBES conceptual framework has been a valuable addition to our understanding of social-ecological systems, with the additions outlined in our modified framework providing an approach for comprehensively assessing complex interactions that can be interwoven in context-specific situations.

Incorporating and advancing important concepts in our modified framework addresses many of the limitations associated with capturing cultural values within the IPBES framework. While many of the additions we propose to the conceptual framework are already implicit within it, explicitly identifying these concepts and processes and locating them within the framework facilitates a formal and replicable approach for assessing social-ecological systems in different contexts. For example, our inclusion of linkages between anthropogenic assets and nature embeds context-specific cultural, social and environmental processes that co-produce NCP in the IPBES conceptual framework (Bruley et al. Citation2021). Operationalising these linkages in our case study enabled us to determine that interactions within and between anthropogenic assets and nature influence how NCP are co-produced, and specifically, that heterogeneity in social-cultural contexts and variation in scales and levels play in integral role in co-production. In tandem with the addition of co-production in our modified framework is the influence of co-construction on ecosystem values. Relational values in particular are a product of how people relate to specific aspects of their environment and are therefore, by definition, perception-based and pluralistic in nature (Stenseke Citation2018). Despite widespread acceptance that value pluralism is influenced by people’s specific cultural context, most assessments tend to adopt a socially aggregated approach that assumes a homogenous community with identical values (Stenseke Citation2018). By applying the modified framework to our case study, we demonstrated that disaggregating ecosystem users according to individual’s socio-cultural context enabled diverse values to be captured and moreover, promotes equity in nature stewardship (Pascual et al. Citation2017; Sarkki and Acosta García Citation2019).

While this framework was produced by interrogating the cultural ecosystem services associated with birds, we argue that it can be operationalized in a variety of contexts. For example, institutions seeking advice on best practice conservation initiatives for local marine ecosystem might use this framework to identify critical entry points for promoting conservation initiatives by targeting the ecological attributes that generate valuable NCP for ecosystem users. This information can be developed by 1) determining the NCP that are generated in these systems through targeted interviews or surveys, and elucidating the ecological attributes that underpin the production of those NCP (e.g. fish communities that produce recreational benefits and provide a source of food), 2) identifying the human community that benefits from these NCP, the context in which these NCP are co-produced, and the extent to which these actors impact ecosystem dynamics via PCN (e.g. local fishers who generate an income from catch but reduce the stock of the system’s top predator, thereby impacting the ecosystem’s food chain), 3) exploring the socio-demographic context of human communities that underpin the co-construction of values associated with the ecosystem (e.g. gender, language, history on the land), and 4) undertaking a pluralistic valuation approach of to identify the range of values present in the system, and determine where those values align or are in potential conflict (e.g. instrumental values associated with fish stock, relational values like recreation and sense of place associated with fishing). Decisions that consider not only the NCP that the ecosystem generates, but also the characteristics of the human community that enable that NCP to be co-produced, can help foster long-term support of conservation initiatives by appealing to the deeply entrenched values of the local population. In this way, both nature’s contributions to people and people’s contributions to nature can be assessed, promoting stewardship of important natural resources and providing vital contributions to people’s wellbeing (Larson et al. Citation2023). This approach further supports the IPBES agenda of departing from traditional neoliberal conservation which frequently promotes a simplified and often ineffective perspective on conservation (Allen Citation2018).

In addition to advancing our understanding of critical social-ecological interactions and feedbacks, mapping cultural ecosystem services onto the IPBES conceptual framework can have practical applications in various domains that have been identified as the primary focus of IPBES to address the complex challenges of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation (Díaz et al. Citation2019). These domains include policy, science-policy interfaces, and scientific research. For example, the approach outlined in this paper may give policymakers a more comprehensive understanding of the demand for and delivery of benefits that ecosystems provide to communities by exploring the characteristics of both human community and nature that co-produce NCP. This knowledge can inform policy decisions related to land use, conservation, and natural resource management (Asah et al. Citation2014). Similarly, mapping cultural ecosystem services onto the IPBES conceptual framework can help resolve ambiguity about how people value non-material NCP. Recognising that different ecosystem users perceive and engage with the environment in different ways, as shown here, promotes the use of complementary valuation techniques that elicit multiple values and support the inclusion of plural perspectives in valuations and the commensurability of different value types (Termansen et al. Citation2022). This advance can help scientists, policymakers, and local communities to bridge the gap between technical ecological knowledge and the cultural significance of ecosystems (Borie and Hulme Citation2015).

Although the modifications we found necessary to make to the IPBES framework have broad general relevance, specific interactions in social and ecological systems identified in our case study may have limited generalizability. For example, Zoeller et al. (Citation2021) described specific elements of people’s socio-cultural context that mediated the ways in which people engage with nature. However, it is likely that the elements of people’s identity that influence their interaction with nature will change depending on the community in question or the scale at which NCP co-production is assessed (Lau et al. Citation2018; Lapointe et al. Citation2019). Similarly, the components of nature that people preferentially engage with may differ depending on the system under assessment. For example, Bartelet et al. (Citation2022) found that the benefits people received from cultural services associated with coral reefs in Australia did not reflect the condition of the ecological system. This implies that subjective human responses to environmental conditions are critical in understanding how an ecosystem is valued and how feedbacks between social and ecological systems are formed. For this reason, the practical application of this adapted framework may face implementation barriers given the challenge of integrating nuanced socio-cultural perspectives in regulatory, institutional, or political decisions. Despite these limitations, the modified framework has potential to advance a more general understanding of the social-ecological interactions that contribute to people’s quality of life, and moreover, provides a standard for assessing these interactions.

Summary

Since the release of the MA 17 years ago, approaches to understanding social-ecological interactions have shifted from utilitarian approaches to valuing ecosystem services (Costanza et al. Citation1997) to approaches that situate culture as the dominant driver of interactions between nature and people (Diaz et al. Citation2015). Despite these significant advances, the ways in which we conceptualise social-ecological interactions are still being refined. Critical gaps persist in our understanding of people’s relationship with nature (Maes et al. Citation2018), and one of the most important of these is our limited understanding of feedback between social and ecological systems (Mastrángelo et al. Citation2019). Beyond its intended use to facilitate the assessment of biodiversity and ecosystem services, our adapted IPBES conceptual framework can be applied in context-specific assessments to define key components and interactions (specifically, two-way human-nature interactions), and provide a more rigorous understanding of the social-cultural mechanisms that underpin NCP production and the ways in which they are valued. This ensures that the wealth of knowledge that has been developed on cultural ecosystem services can be applied under new assessment frameworks. Further, assessing social-ecological systems through this adapted framework enables implicit connections to be drawn out, thereby providing holistic insight into the feedbacks and linkages that should be considered at all levels of environmental decision-making.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (297.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2024.2329576

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen K. 2018. Why exchange values are not environmental values: explaining the problem with neoliberal conservation. Conserv Soc. 16(3):243. doi: 10.4103/cs.cs_17_68.

- Anderies JM, Janssen MA, Ostrom E. 2004. A framework to analyze the robustness of social-ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecol Soc. 9(1):18–13. doi: 10.5751/ES-00610-090118.

- Anderson CB, Athayde S, Raymond CM, Vatn A, Arias P, Gould RK, Kenter J, Muraca B, Sachdeva S, Samakov A, et al. 2022. Chapter 2: conceptualizing the diverse values of nature and their contributions to people. In: Balvanera P, Pascual U, Christie M, Baptiste B, González-Jiménez D, editors. Methodological assessment report on the diverse values and valuation of nature of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6493134.

- Asah ST, Guerry AD, Blahna DJ, Lawler JJ. 2014. Perception, acquisition and use of ecosystem services: human behavior, and ecosystem management and policy implications. Ecosyst Serv. 10:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.003.

- Bartelet HA, Barnes ML, Zoeller KC, Cumming GS. 2022. Social adaptation can reduce the strength of social–ecological feedbacks from ecosystem degradation. People Nat. 4:856–865.

- Bellwood DR, Streit RP, Brandl SJ, Tebbett SB, Graham N, Graham N. 2019. The meaning of the term ‘function’ in ecology: a coral reef perspective. Funct Ecol. 33(6):948–961. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13265.

- Bennett EM, Solan M, Biggs R, McPhearson T, Norström AV, Olsson P, Pereira L, Peterson GD, Raudsepp‐Hearne C, Biermann F. 2016. Bright spots: seeds of a good anthropocene. Front Ecol Environ. 14(8):441–448. doi: 10.1002/fee.1309.

- Borie M, Hulme M. 2015. Framing global biodiversity: IPBES between mother earth and ecosystem services. Environ Sci Policy. 54:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2015.05.009.

- Braat LC. 2018. Five reasons why the science publication “assessing nature’s contributions to people”(Diaz et al. 2018) would not have been accepted in ecosystem services. Ecosyst Serv. 30:A1–A2. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.02.002.

- Brondizio ES, Settele J, Díaz S, Ngo HT, editors. 2019. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3831673.

- Bruley E, Locatelli B, Lavorel S. 2021. Nature’s contributions to people: coproducing quality of life from multifunctional landscapes. Ecol Soc. 26(1):12. doi: 10.5751/ES-12031-260112.

- Census. 2011. South Africa: Statistics South Africa.

- Chan KM, Satterfield T, Goldstein J. 2012. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol Econ. 74:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.11.011.

- Chaplin-Kramer R, Sharp RP, Weil C, Bennett EM, Pascual U, Arkema KK, Brauman KA, Bryant BP, Guerry AD, Haddad NM. 2019. Global modeling of nature’s contributions to people. Science. 366(6462):255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw3372.

- Cheng X, Van Damme S, Li L, Uyttenhove P. 2019. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: a review of methods. Ecosyst Serv. 37:100925. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100925.

- Clark WC, Harley AG. 2020. Sustainability science: toward a synthesis. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 45(1):331–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-043621.

- Costanza R, d’Arge R, De Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O’neill RV, Paruelo J. 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 387:253–260. doi: 10.1038/387253a0.

- Costanza R, De Groot R, Braat L, Kubiszewski I, Fioramonti L, Sutton P, Farber S, Grasso M. 2017. Twenty years of ecosystem services: how far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst Serv. 28:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.008.

- Cox DTC, Hudson HL, Plummer KE, Siriwardena GM, Anderson K, Hancock S, Devine-Wright P, Gaston KJ, MacIvor JS, MacIvor JS. 2018. Covariation in urban birds providing cultural services or disservices and people. J Appl Ecol. 55(5):2308–2319. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13146.

- Cumming GS, Child MF. 2009. Contrasting spatial patterns of taxonomic and functional richness offer insights into potential loss of ecosystem services. Phil Trans R Soc B. 364:1683–1692.

- Daily GC. 1997. Nature’s services : societal dependence on natural ecosystems. Washington DC: Island Press.

- de Groot R, Costanza R, Braat L, Brander L, Burkhard B, Carrascosa J, Crossman N, Egoh B, Geneletti D, Hansjuergens B. 2018. Ecosystem services are nature’s contributions to people: response to: assessing nature’s contributions to people. Sci Prog. 359:270–272.

- de Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ. 2002. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ. 41(3):393–408. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7.

- Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Adhikari JR, Arico S, Báldi A. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework—connecting nature and people. Curr Opin Sust. 14:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002.

- Diaz S, Demissew S, Joly C, Lonsdale WM, Larigauderie A. 2015. A Rosetta Stone for nature’s benefits to people. PLoS Biol. 13(1):e1002040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002040.

- Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López B, Watson RT, Molnár Z, Hill R, Chan KM, Baste IA, Brauman KA. 2018. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science. 359(6373):270–272. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8826.

- Díaz SM, Settele J, Brondízio E, Ngo H, Guèze M, Agard J, Arneth A, Balvanera P, Brauman K, Butchart S. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3553579.

- Dunkley R, Baker S, Constant N, Sanderson-Bellamy A. 2018. Enabling the IPBES conceptual framework to work across knowledge boundaries. Int Environ Agreements. 18(6):779–799. doi: 10.1007/s10784-018-9415-z.

- Ellis EC, Pascual U, Mertz O. 2019. Ecosystem services and nature’s contribution to people: negotiating diverse values and trade-offs in land systems. Curr Opin Sust. 38:3886–3894. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.05.001.

- Faith DP. 2018. Avoiding paradigm drifts in IPBES: reconciling “nature’s contributions to people,” biodiversity, and ecosystem services. Ecol Soc. 23(2): doi: 10.5751/ES-10195-230240.

- Fischer A, Eastwood A. 2016. Coproduction of ecosystem services as human–nature interactions—an analytical framework. Land Use Policy. 52:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.004.

- Haines-Young R, Potschin M. 2012. Common international classification of ecosystem services. Nottingham: Centre for Environmental Management, University of Nottingham.

- Haller-Bull V, Rovenskaya E. 2019. Optimizing functional groups in ecosystem models: case study of the great barrier reef. Ecol Modell. 411:108806. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2019.108806.

- Hill R, Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Molnár Z, Van Velden J. 2021. Nature’s contributions to people: weaving plural perspectives. One Earth. 4:910–915. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.009.

- Jones L, Boeri M, Christie M, Durance I, Evans KL, Fletcher D, Harrison L, Jorgensen A, Masante D, McGinlay J, et al. 2021. Can we model cultural ecosystem services, and are we measuring the right things? People Nat. 4(1):166–179. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10271.

- Kenter JO. 2018. IPBES: Don’t throw out the baby whilst keeping the bathwater; put people’s values central, not nature’s contributions. Ecosyst Serv. 33:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.08.002.

- Kilonzi F, Ota T. 2019. Influence of cultural contexts on the appreciation of different cultural ecosystem services based on social network analysis. One Ecosyst. 4. doi: 10.3897/oneeco.4.e33368.

- Kosanic A, Petzold J. 2020. A systematic review of cultural ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Ecosyst Serv. 45:101168. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101168.

- Lapointe M, Cumming GS, Gurney GG. 2019. Comparing ecosystem service preferences between urban and rural dwellers. BioScience. 69(2):108–116. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biy151.

- Lapointe M, Gurney GG, Cumming GS. 2020. Urbanization alters ecosystem service preferences in a small Island developing state. Ecosyst Serv. 43:101109. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101109.

- Larson S, Jarvis D, Stoeckl N, Barrowei R, Coleman B, Groves D, Hunter J, Lee M, Markham M, Larson A, et al. 2023. Piecemeal stewardship activities miss numerous social and environmental benefits associated with culturally appropriate ways of caring for country. J Environ Manage. 326:116750. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116750.

- Lau JD, Hicks CC, Gurney GG, Cinner JE. 2018. Disaggregating ecosystem service values and priorities by wealth, age, and education. Ecosyst Serv. 29:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.12.005.

- Lele S, Springate-Baginski O, Lakerveld RP, Deb D, Dash P. 2013. Ecosystem services: origins, contributions, pitfalls, and alternatives. Conserv Soc. 11(4):343–358. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.125752.

- MA. 2005. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. Washington: Island Press.

- Maes J, Burkhard B, Geneletti D. 2018. Ecosystem services are inclusive and deliver multiple values. A comment on the concept of nature’s contributions to people. One Ecosyst. 3:e24720. doi: 10.3897/oneeco.3.e24720.

- Masterson VA, Vetter S, Chaigneau T, Daw TM, Selomane O, Hamann M, Wong GY, Mellegård V, Cocks M, Tengö M. 2019. Revisiting the relationships between human well-being and ecosystems in dynamic social-ecological systems: implications for stewardship and development. Global Sustainability. 2. doi: 10.1017/sus.2019.5.

- Mastrángelo ME, Pérez-Harguindeguy N, Enrico L, Bennett E, Lavorel S, Cumming GS, Abeygunawardane D, Amarilla LD, Burkhard B, Egoh BN, et al. 2019. Key knowledge gaps to achieve global sustainability goals. Nat Sustain. 2(12):1115–1121. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0412-1.

- McElwee P, Fernández‐Llamazares Á, Aumeeruddy‐Thomas Y, Babai D, Bates P, Galvin K, Guèze M, Liu J, Molnár Z, Ngo HT, et al. 2020. Working with Indigenous and Local Knowledge (ILK) in large‐scale ecological assessments: reviewing the experience of the IPBES global assessment. J Appl Ecol. 57(9):1666–1676. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13705.

- Muradian R, Gómez-Baggethun E. 2021. Beyond ecosystem services and nature’s contributions: Is it time to leave utilitarian environmentalism behind? Ecol Econ. 185. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107038.

- Muradian R, Pascual U. 2018. A typology of elementary forms of human-nature relations: a contribution to the valuation debate. Curr Opin Sust. 35:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.014.

- O’Connor S, Kenter JO. 2019. Making intrinsic values work; integrating intrinsic values of the more-than-human world through the life framework of values. Sustainability Sci. 14(5):1247–1265. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00715-7.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Christie M et al. 2023. Editorial overview: Leveraging the multiple values of nature for transformative change to just and sustainable futures — Insights from the IPBES Values Assessment. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 64:101359.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Díaz S, Pataki G, Roth E, Stenseke M, Watson RT, Başak Dessane E, Islar M, Kelemen E, et al. 2017. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach. Curr Opin Sust. 26-27:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006.

- Peterson GD, Harmáčková ZV, Meacham M, Queiroz C, Jiménez-Aceituno A, Kuiper JJ, Malmborg K, Sitas N, Bennett EM. 2018. Welcoming different perspectives in IPBES: “Nature’s contributions to people” and “ecosystem services”. Ecol Soc. 23(1): doi: 10.5751/ES-10134-230139.

- Sarkki S, Acosta García N. 2019. Merging social equity and conservation goals in IPBES. Conserv Biol. 33(5):1214–1218. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13297.

- Scholte SSK, van Teeffelen AJA, Verburg PH. 2015. Integrating socio-cultural perspectives into ecosystem service valuation: a review of concepts and methods. Ecol Econ. 114:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.007.

- Schröter M, Başak E, Christie M, Church A, Keune H, Osipova E, Oteros-Rozas E, Sievers-Glotzbach S, van Oudenhoven APE, Balvanera P, et al. 2020. Indicators for relational values of nature’s contributions to good quality of life: the IPBES approach for Europe and central Asia. Ecosyst People. 16(1):50–69. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2019.1703039.

- Schroter M, Egli L, Bruning L, Seppelt R. 2021. Distinguishing anthropogenic and natural contributions to coproduction of national crop yields globally. Sci Rep. 11(1):10821. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90340-1.

- Schröter M, van der Zanden EH, van Oudenhoven APE, Remme RP, Serna-Chavez HM, de Groot RS, Opdam P. 2014. Ecosystem services as a contested concept: a synthesis of critique and counter-arguments. Conserv Lett. 7(6):514–523. doi: 10.1111/conl.12091.

- Sekercioglu CH. 2006. Increasing awareness of avian ecological function. Trends Ecol Evol. 21(8):464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.007.

- Stenseke M. 2018. Connecting ‘relational values’ and relational landscape approaches. Curr Opin Sust. 35:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.025.

- Stephenson W. 1953. The study of behavior; Q-technique and its methodology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Taylor MR, Peacock F. 2018. The state of South Africa’s bird report 2018. Johannesburg, South Africa: BirdLife South Africa.

- Tengö M, Hill R, Malmer P, Raymond CM, Spierenburg M, Danielsen F, Elmqvist T, Folke C. 2017. Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Curr Opin Sust. 26:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.005.

- Termansen M, Jacobs S, Mwampamba TH, Ahn S, Castro A, Dendoncker N, Ghazi H, Gundimeda H, Huambachano M, Lee H, et al. 2022. Chapter 3. The potential of valuation. In: Balvanera P, Pascual U, Christie M, Baptiste B, and González-Jiménez D, editors. Methodological assessment report on the diverse values and valuation of nature of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6521298.

- Topp E, Loos J, Martín-López B. 2021. Decision-making for nature’s contributions to people in the cape floristic region: the role of values, rules and knowledge. Sustain Sci. 17:1–22. doi:10.1007/s11625-020-00896-6.

- Turner BL. 1997. The sustainability principle in global agendas: implications for understanding land-Use/Cover change. Geogr J. 163(2):133–140. doi: 10.2307/3060176.

- Virapongse A, Brooks S, Metcalf EC, Zedalis M, Gosz J, Kliskey A, Alessa L. 2016. A social-ecological systems approach for environmental management. J Environ Manage. 178:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.028.

- Zoeller KC, Cumming GS. 2023. Cultural functional groups associated with birds relate closely to avian ecological functions and services. Ecosyst Serv. 60:60. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2023.101519.

- Zoeller KC, Gurney GG, Cumming GS. 2022. The influence of landscape context on the production of cultural ecosystem services. Landscape Ecol. 37(3):883–894. doi: 10.1007/s10980-022-01412-0.

- Zoeller KC, Gurney GG, Heydinger J, Cumming GS. 2020. Defining cultural functional groups based on perceived traits assigned to birds. Ecosyst Serv. 44:101138. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101138.

- Zoeller KC, Gurney GG, Marshall N, Cumming GS. 2021. The role of socio-demographic characteristics in mediating relationships between people and nature. Ecol Soc. 26(3): doi: 10.5751/ES-12664-260320.