ABSTRACT

Urban forests are characterized by relationships between people and trees, where urban trees provide benefits to people and people make decisions impacting trees. People’s perceptions of urban forests are related to the cognitive processes that underpin benefits received from trees, while also influencing support for or against trees and their management. A growing literature has considered urban forest perceptions, but most studies are limited to a single geographic area and focus on socio-economic influences, with less consideration of location and cultural influences. This study explores the relationship between where people live, the language they speak, and multiple perception responses associated with urban forests (i.e. values, beliefs, trust, satisfaction) to better understand commonalities and differences across distinct geographic settings and populations. We conducted an online survey about urban forest perceptions in three Canadian urban regions, allowing us to explore perceptions between regions, locations on an urban gradient and language spoken. We found geographic and language differences primary for beliefs held about urban trees and trust in municipal government’s decision-making about those trees, while values and satisfaction with trees and their management were more stable across geographic settings and language spoken. Our findings suggest that some perceptions vary between populations. Additionally, our findings reinforce the need for urban forest managers to understand the specific perceptions held by different populations, rather than assume universality of perception, to ensure specific and differential urban forest management objectives are in place to supports local people and ecological elements.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Urban ecosystems are socio-ecological systems defined by relationships between people and ecological elements. Urban ecological elements provide many benefits to humans, including positively contributing to health and well-being (Tyrväinen et al. Citation2014; Turner-Skoff and Cavender Citation2019; Wolf et al. Citation2020). For example, tree shade can reduce exposure to ultraviolet radiation, a major cause of skin cancer, and time in urban nature can improve cognitive function (Wolf et al. Citation2020). People, in turn, make decisions that impact ecological structure and function. Perceptions of urban ecosystems, defined as the ways people cognitively process information about their experiences with urban ecological elements and landscapes (Rossi et al. Citation2015), are key to understanding socio-ecological interactions as they express the range of human meanings associated with ecosystems and the encounters people have with elements of those systems. For example, perceptions underpin the psychological and health responses people have to ecological elements (van den Berg et al. Citation2019; Whitburn et al. Citation2019).

Knowledge of perceptions can help understand decisions, including support for different management priorities, that impact ecosystems. In urban ecosystems, whether people support tree planting, what types of trees people choose to plant and whether they remove trees is influenced by their perceptions, including their attitudes towards urban trees, preferences for different tree types, beliefs about the benefits and costs of trees, and values associated with urban trees (Lohr et al. Citation2004; Schroeder et al. Citation2006; Avolio et al. Citation2015; Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019; Shackleton and Mograbi Citation2020). Thus, perceptions are fundamental to how people interact with ecosystems (Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019). This knowledge is also needed to design policy and programs that support both people and ecological elements (Jones et al. Citation2013). For example, a municipality planting large shade trees may support its ecological goals for greater carbon storage and temperature regulation, but negatively impact people’s support for management and the trees if most have preferences for smaller stature trees (Conway and Bang Citation2014).

Perceptions also underpin rationales behind ecosystem management strategies that reflect ecosystem values (i.e. how people perceive the importance of, and the abstract meanings people attach to, ecosystems; Stern et al. Citation1995; Dietz et al. Citation2005; Kendal et al. Citation2015). Two common frameworks that advance specific sets of ecosystem values include ecosystem services (i.e. the functions of ecosystems that provide benefits to humans; Dobbs et al. Citation2014; Baumeister et al. Citation2022) and nature’s contributions to people (i.e. ecosystem services through a human cultural lens; Díaz et al. Citation2018). Research examining what ecosystem benefits and contributions people perceive can be used to further generate support for management, while making management more responsive to local communities.

Perception research conceptualizes notions of how something is being perceived, cognitive constructs that may be generated in the person perceiving, and the perception responses being studied. The Cognitive Model can be a useful way to distinguish perceptions and constructs in terms of their level of abstraction, number, and ease of change, among other characteristics (; Stern et al. Citation1995; Schultz and Zelezny Citation1999; Rossi et al. Citation2015; Kendal et al. Citation2022). In this model, values and beliefs refer to more abstract cognitive constructs, with values reflecting what is important to people, while beliefs represent things that people accept are true, or the positive or negative consequences of something. Values and beliefs are fewer in number than other perceptions, tend to develop over long time periods, and are fundamental to how people define themselves, so they are not easily changed (Stern et al. Citation1995; Schultz and Zelezny Citation1999). On the other hand, attitudes and preferences refer to people’s judgments or disposition towards things and how much people like something. These are more numerous and concrete than values and beliefs, which also influence them. Two examples of attitudes are trust and satisfaction. Trust in relation to urban trees can be measured as the degree to which an actor is expected to make good decisions about trees (Kendal et al. Citation2022), while satisfaction reflects how well people’s experiences match their expectations (Tung and Ritchie Citation2011). These constructs are widely used in many disciplines, including environmental and natural sciences, such as environmental geography, environmental psychology, or environmental sociology (Kendal et al. Citation2022).

Figure 1. Perceptions included in this study, derived from the Cognitive Model that differentiates perceptions based on level of abstraction, stability, and number (Stern et al. Citation1995; Schultz and Zelezny, Citation1999; Tung and Ritchie, Citation2011; Kendal et al. Citation2022).

Urban forests, including trees in parks, along streets, on private property and in other urban settings, are often the most visible component of urban ecosystems (FAO Citation2016). The benefits provided by urban forests have been extensively examined, primarily through an ecosystem services framework. This includes a growing body of research examining the cultural ecosystem services of urban forests that are associated with a variety of physical and mental health outcomes (Wolf et al. Citation2020; Baumeister et al. Citation2022; O’Brien et al. Citation2022). Many cities are now investing in their urban forests to increase ecosystem service provisioning in general, and specifically because of the health benefits (Wolf et al. Citation2020). Knowledge of urban forest perceptions across diverse populations is needed to better understand the pathways that lead to experienced benefits, decisions people are making about their own trees, and level of support for urban forest management that can produce desired benefits (Kendal et al. Citation2022).

Urban forest perceptions have been measured in various ways (Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022), with perceptions of urban tree benefits and preferences for specific species traits frequently considered in this literature (e.g. Lohr et al. Citation2004; Schroeder et al. Citation2006; Zhang and Zheng Citation2011; Avolio et al. Citation2015). However, many terms have been used to measure different aspects of urban ecosystem perceptions, often in overlapping and/or in inconsistent ways. For example, benefits, beliefs, services, and values are used interchangeably in the urban forest literature, making comparisons across studies challenging (Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022).

Although socio-demographic factors are commonly explored influences on urban forest perceptions, geographic location has been found to be equally or more influential (Avolio et al. Citation2015; Krajter Ostoić et al. Citation2017; Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019; Baumeister et al. Citation2022). For example, Krajter Ostoić et al. (Citation2017) found more variation in perceptions between countries than differences associated with socio-demographics, while Avolio et al. (Citation2015) showed that within a metropolitan area, location was as important as socio-demographics on perception responses.

Our understanding of geographic influence on urban forest, and more generally urban ecosystem, perceptions is limited, however, as most studies focus on a single city or a specific area within one city (Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022). Only a few studies have considered how perception responses vary by location (e.g. multiple cities or urban regions; Schroeder et al. Citation2006, US and England; Shackleton and Mograbi Citation2020, South Africa and Zimbabwe; Krajter Ostoić et al. Citation2017 Southeastern European countries) or across different urban contexts (e.g. different areas of an urban region; Kendal et al. Citation2022; Su et al. Citation2022). Moreover, the studies that have compared different locations typically have not included multiple perception responses (e.g. values, beliefs, trust, and satisfaction; Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022).

Location likely plays a role in perceptions because the abundance, distribution, and diversity of urban forests varies between cities (Jenerette et al. Citation2016). There are also differences within urban areas, often related to urban form and neighborhood socio-demographics (Conway and Hackworth Citation2007; Landry and Chakraborty Citation2009; Pham et al. Citation2017; Landry et al. Citation2020; Quinton et al. Citation2022; Threlfall et al. Citation2022). Thus, not all residents within the same urban region, much less in locations that are geographically separated, experience the same urban forest, which likely influences at least some perceptions.

Limited attention has also been given to measures of culture within the urban forest perception literature, although culture identity is related to many perception responses (Taylor Citation1994). Recent findings suggest language spoken may be an influential dimension of culture that is associated with specific values held about urban nature spaces and urban forests (Egerer et al. Citation2019; Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022; Su et al. Citation2022). This may be because language broadly structures the ways different cultures understand the relationship between people and the natural world (Coscieme et al. Citation2020) and, more specifically, language spoken reflects social integration, which includes relationships with local government and sources of information (Jay and Schraml Citation2009; Su et al. Citation2022). However, urban forest perception differences by language spoken have not been explored across multiple perception measures.

This study begins to address gaps in our understanding of the relationship between where people live, the language they speak, and the multiple perception responses associated with urban forests through a survey conducted in three Canadian urban regions centered around the cities of Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver. The research was driven by two questions: (1) are there differences in perceptions related to geographic setting, focusing on differences between urban regions and location on an urban gradient within each region, and (2) are there differences in perceptions held by people who speak English or French, Canada’s two official languages, and/or other languages? To address the first question, we compared perceptions across the three urban regions as well as four municipal contexts using an urban gradient classification that went from inner urban cores through to urban municipalities outside the official metropolitan boundary. For the second question, we compared the language people speak based responses to a language(s) spoken question on the survey. The Montreal region’s population is comprised mostly of Francophones, while Toronto and Vancouver regions’ population primarily speak English, although all three regions include people who speak both official languages and/or whose first language is neither.

We hypothesize that our values and beliefs responses will not differ by geographic setting since our constructs of values and beliefs are conceptualized to be minimally influenced by day-to-day conditions or experiences with urban trees (Kendal et al. Citation2022). On the other hand, we hypothesize that trust in municipalities and satisfaction with urban trees and their management will vary by geographic setting because they are more likely to reflect current conditions and recent experiences with urban trees (Krajter Ostoić et al. Citation2017; Kendal et al. Citation2022; Coleman et al. Citation2023). Additionally, the notion of trust in the institutions in charge of urban forest management is grounded in the governance dynamics between communities and their government institutions (Levi and Stoker Citation2000; Keele Citation2007), with previous research suggesting that trust in institutions varies across Canada (Cotter Citation2015). We also hypothesize differences across all perception measures by language, as suggested by Egerer et al. (Citation2019). While language is a component of cultural identity often associated with values and beliefs (Taylor Citation1994), it also influences sources of information and relationship to one’s community and institutions (Bridgman et al. Citation2022). Thus, with our focus on Canada’s official languages, we anticipate language spoken to influence both abstract and more concrete perceptions.

This comparative study contributes to a better understanding of commonalities and differences in urban forest perceptions across distinct geographic settings and language populations. The findings advance knowledge about the cognitive links between people and urban ecosystems that facilitate positive health outcomes and support for urban ecosystem management.

2. Methods

2.1. Study areas

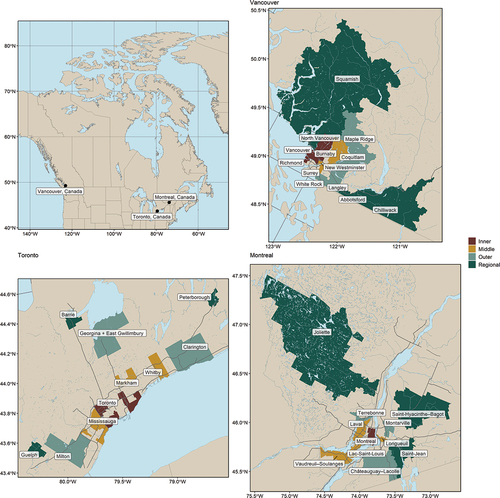

We conducted this study in three of the largest urban regions in Canada: Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver (). Each region is defined by the metropolitan area and the economically and socially connected urban municipalities just outside it. Thus, each region captures a gradient of high-density inner urban cores through to peri-urban municipalities on the outer edge of the metropolitan area, as well as surrounding regional cities. Regional cities tend to be relatively small (populations of 100,000 or less) and have close ties to the metropolitan area. Focusing on the three regions allowed us to explore different geographic settings as well as language differences: 75% of the residents in the Montreal metropolitan area primarily speak French, while in the Toronto and Vancouver metropolitan areas, 80% and 78%, respectively, primarily speak English (Statistics Canada Citation2021a). Additionally, numerous people speak more than one language and for many, French or English is a second language.

Figure 2. Surveyed areas reflecting different municipal contexts (inner cores, middle, outer and regional cities) of the urban regions of Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver.

The Montreal region (Quebec) is located along the St. Lawrence River, with a warm summer continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb). The urban region that includes Toronto (Ontario) is located just North of Lake Ontario, with a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa). Both Montreal and Toronto are located in the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone. On the West Coast of Canada, Vancouver (British Columbia) has a moderate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), with many microclimates across the region, and falls within the Pacific Maritime Ecozone.

Across the three regions, urban forest management occurs primarily at the municipal level, although characteristics of that management differ within and between regions. Moreover, the City of Montreal is divided into 19 boroughs, which are typically also involved in urban forest management. While the extent, species, and structure of the urban forest also varies within and between the regions, canopy cover or other comparable urban forest data do not exist for all study area municipalities, particularly for the outer municipalities and regional cities included in this study.

The study areas also include diverse populations. For example, the Montreal metropolitan area population is 27% visible minorities and 25% immigrants (Statistics Canada Citation2021a, Citation2021c). In metropolitan Toronto and Vancouver, visible minorities represent 57% and 54% of the population, respectively, while 49% and 44% are immigrants. The urban municipalities outside the official metropolitan boundary, however, tend to have fewer visible minorities and immigrants, and a higher percentage of French or English speakers. For example, only 6% of the population in Joliette, located outside of Montreal (see ), are immigrants and 30% are immigrants in Abbotsford, located outside of Vancouver.

2.2. Survey design, sampling strategy, and recruitment

Our study draws on a survey conducted in the three regions using a systematic, random, and probabilistic sampling approach (Dillman et al. Citation2014). Our sampling focused on capturing different contexts along an urban gradient within each region (Dobbs et al. Citation2014; Kendal et al. Citation2022). Thus, in each region one high-density urban core (inner municipalities), three mid-density suburban (middle municipalities), three low-density peri-urban (outer municipalities), and three urban municipalities beyond the official metropolitan area (regional municipalities) were targeted, aiming for 2,000 respondents per region. Specific municipalities were identified based on their relative location and demographics, to capture the geographic extent of the region (). Due to differences in municipal populations, we joined or split some municipalities to obtain complementary responses (see Supplementary Material for additional information).

We sought responses from a diverse range of people using an electronic panel survey, an internet-based data collection technique that sends survey invitations to a socio-demographically representative group of potential participants (Dillman et al. Citation2014). We used a panel managed by a market research company with access to more than one million panelists in Canada (Asking Canadians®, www.askingcanadians.com). The respondents were compensated with a nominal fee. The survey in Toronto was conducted from 25 May to 11 June 2021, while the surveys in Montreal and Vancouver were conducted from 2 June to 13 July 2022. The surveys in Toronto and Vancouver were delivered only in English. The survey in Montreal was available in English and French. The French language version was translated from the original English by a co-author who is fluent in both languages and then reviewed by other co-authors who are also fluent in French. All geographic sampling quotas by municipality context were either met or surpassed (see Supplement Material). Ethics approval to conduct the survey research was provided by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (no. 40945).

2.3. Survey content

The survey contained questions based on the Cognitive Model developed by Kendal et al. (Citation2022). This allowed us to capture multiple perception responses (values, beliefs, trust in the municipality, and satisfaction) related to urban trees and municipal management of them () in a way that is comparable with other urban forest perception studies (Kendal et al. Citation2022; Su et al. Citation2022).

To measure values, we adapted the Valued Attributes of Landscape Scale (VALS; Kendal et al. Citation2015). The VALS is a psychometric measure of people’s environmental values that is more contextual than typical measures, which are usually focused on abstract notions of nature (e.g. ‘I value nature in general’). In contrast, the VALS is focused on the reasons for valuing concrete aspects of nature, such as particular natural elements or landscapes (e.g. ‘I value the urban forest because it connects me to nature’). We adapted the VALS scale to use 16 items, with each item rated by the degree of importance the respondents place on it in, using a 5-point scale.

We measured beliefs, by adapting existing lists of the negative and positive aspects of urban forests and urban trees compiled by Kendal et al. (Citation2022). This integration of measures resulted in 13 items reflecting positive beliefs (e.g. ‘Trees provide shade’) and 13 for negative beliefs (e.g. ‘Trees block water pipes and drains’) about the consequences of having trees in urban areas. Each item was rated by the degree of agreement on a 5-point Likert-based scale.

Grounded in the concept of trust in public institutions (Levi and Stoker Citation2000), we used the measure trust in the municipality in charge of urban trees developed by Kendal et al. (Citation2022). The measure of trust in municipality includes six items reflecting different aspects of urban tree decision-making (e.g. ‘I expect that the local government will make the right decision regarding trees’) and inclusion (e.g. ‘Listens to the public’) rated by the degree of agreement on a 5-point Likert-based scale.

To measure satisfaction with urban trees and their management we used two scales from Kendal et al. (Citation2022). The satisfaction with urban trees scale and the satisfaction with urban trees management scale are measures of satisfaction with the ecological and social aspects of urban trees in their living context, which is more concrete than some recently used urban forestry satisfaction measures (e.g. Coleman et al. Citation2023). The satisfaction with urban trees scale is an 8-item scale that includes items such as diversity and abundance (e.g. ‘Right number of trees for area’). The satisfaction with urban trees management scale is an 8-item scale that included items such as appropriate maintenance and equitable planting (e.g. ‘Timely replacement of trees that have been removed’). All satisfaction items are rated on a 5-point scale.

We measured language in two ways to explore differences that may be associated with the official government language to build on previous research suggesting that language spoken, as a measure of cultural identity, is related to perception responses (Egerer et al. Citation2019; Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022; Su et al. Citation2022). All participants were asked about the language they primarily speak at home. First, we created a variable with an English category and a French category applicable to all three regions; this variable did not consider the language used to complete the survey, and respondents who do not speak one of Canada’s official languages at home were excluded. Second, a variable reflecting French as a second language (FSL) in Montreal or English as a second language (ESL) in Toronto and Vancouver, resulting in F/ESL and non-F/ESL categories, allowed us to explore people who whose first language is not the official language of their region. We also collected basic demographic data for context about our survey sample and compared it with Statistics Canada Citation2016 census data to understand the representativeness of our sample population.

2.4. Data analysis

The measures of values, beliefs, trust, and satisfaction were analyzed with factor analysis to simplify the dimensions of the multi-item scales (Kaiser Citation1974). Following previous results with these measures by Kendal et al. (Citation2022), we used a confirmatory factor analysis approach with the cfa function in the lavaan package (v. 0.6–9) in R v. 4.1.2 (R Core Team Citation2022). We then averaged the items that loaded on each factor to generate new variables. Factor reliability was calculated using the fa.parallel function with an oblimin rotation (appropriate for rating scales) as well as the alpha function from the psych package (v. 1.9).

Details of the confirmatory factors analysis are in the Supplementary Materials. The modified VALS scale results in four value factors, or themes, that people attribute to urban forests, labelled cultural values (e.g. ‘Learning about cultural traditions’), social values (e.g. ‘Spaces for people to interact and socialize’), identity values (e.g. ‘Make the city more welcoming’), and natural values (e.g. ‘Habitat for rare or threatened plants, birds, and animals’). The beliefs items divide into two factors, labelled negative beliefs (e.g. ‘Trees cause mess’) and positive beliefs (e.g. ‘Trees are calming’). Municipal trust is also represented by two factors: procedural fairness (e.g. ‘Listens to the public’) and competency (e.g. ‘Make the right decisions’). The satisfaction with urban trees items divide into two factors, called satisfaction with amenity aspects (e.g. ‘Attractiveness (looks good)’) and ecology aspects (e.g. ‘Habitat (trees that provide shelter or food for animals)’). Finally, three factors represent the satisfaction with management items, labelled appropriate (e.g. ‘Appropriate management of living trees (pruning, watering, etc.)’, timely (e.g. ‘Timely replacement of trees that have been removed’), and sufficient (e.g. ‘Equitable planting of trees, across all neighborhoods so everybody has a tree near them’).

We evaluated the mean differences of the perception factors by geographic setting and our two measures of language. While all the measures tested positive for non-normality using standard tests, we deemed it adequate to conduct parametric tests given that large datasets can usually justify assumptions of symmetry and balance across variable groupings in simple means differences parametric statistical testing (Hair et al. Citation2014; Rosner Citation2015). To evaluate the relative contribution and potential interaction effect of urban region (i.e. Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver) and municipal context (i.e. inner, middle, outer, and regional), we performed 2-way ANOVAs. For our binary language measures, we conducted t-tests. We also created violin plots, which show the distribution of the data, to visualize the comparisons between the various factors. These visuals were created using the ggplot2 package (v. 3.4.2) in R v. 4.1.2 (R Core Team Citation2022).

3. Results

We collected data from 5,455 respondents. In some cases, a respondent did not complete all questions, with an average number of responses per question being 1,701 (SD = 6.88) in Montreal, 2,011 (SD = 10.72) in Toronto, and 1,732 (SD = 7.09) in Vancouver. The demographic profiles of the responses were similar to their corresponding metropolitan areas, with some exceptions (). The response sample had a higher education-level and age, a lower number of French/English as second language respondents, and a lower number of Indigenous respondents. However, these differences may, in part, reflect the inclusion of regional cities and only a sub-set of metropolitan-based municipalities in our sample.

Table 1. Demographic and cultural profile of survey sample for Montreal (n = 1,703), Toronto (n = 2,015), and Vancouver (n = 1,737) regions and census data for the metropolitan areas.

Overall, most respondents assigned a high level of importance to our values measures, with slightly higher importance associated with the social and natural value factors, as compared to the cultural and identity value factors (; full results in Supplementary Material). There was higher agreement with positive beliefs than negative beliefs, while both trust factors had average response scores that indicated moderate agreement. The mean satisfaction score for the tree amenity factor was higher than for the tree ecology factor, while the three management factors had lower average satisfaction scores.

Table 2. Average responses for value, beliefs, trust, and satisfaction factors, measured from 1 (low importance/agreement/satisfaction) to 5 (high importance/agreement/satisfaction).

3.1. Geographic setting

Results from 2-way ANOVAs for the geographic variables found some significant variations between geographic settings (). Surprisingly, both social values and natural values were significant for the interaction term between urban region and municipal context. For social values, the violin plots show Montreal with the highest average importance score for inner municipalities as compared to other municipal contexts (), while Toronto and Vancouver have slightly higher average importance scores in municipal contexts beyond the inner municipality. For natural values, a pattern of importance scores increasing from inner through to regional municipal contexts exists for all regions, but where the increase occurs varies (): Montreal respondents from inner, middle and outer municipalities have assigned very similar importance, and a higher average importance for regional municipalities; Toronto respondents from inner and middle municipal contexts assigned relatively low importance and respondents from outer and regional municipalities gave higher importance scores; while Vancouver respondents in the inner municipality gave the lowest average importance score but higher importance was assigned by respondents in the three other municipal contexts. Finally, cultural values are moderately significant for region and weakly significant for municipal context, although a very small magnitude of difference between average responses exists.

Figure 3. Violin plots showing survey respondents assignment of importance for statements loading on each of the urban forest values factors, aggregated by the four municipal contexts (inner, middle, outer, regional), in each of the three regions (Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver). The average (circle), interquartile range (box), and overall data distribution are depicted (Montreal n = 1,703; Toronto n = 2,015; Vancouver n = 1,737).

Table 3. 2-way ANOVA results for the geographic variables and perception measures.

Significant differences in the geographic interaction term were also found for both negative and positive beliefs. For negative beliefs, the violin plots show Montreal respondents in inner, middle, and outer municipalities had the lowest agreement (; i.e. lower negative beliefs). Interestingly, the same occurred for positive beliefs (i.e. lower positive beliefs). Toronto shows a decrease in agreement scores for negative beliefs between respondents from inner/middle and outer/regional municipalities. Both Vancouver and Montreal respondents from regional municipalities assigned higher agreement scores than those from outer municipalities. The factor positive beliefs has a pattern similar to natural values (), with increasing average agreement scores from respondents in inner through regional municipalities in Toronto and Vancouver but little variation observed in the Montreal region across municipal contexts.

Figure 4. Violin plots showing survey respondents level of agreement for statements loading on each of the urban forest beliefs and trust in municipality factors, aggregated by the four municipal contexts (inner, middle, outer, regional), in each of the three regions (Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver). The average (circle), median (line), interquartile range (box), and overall data distribution are depicted (Montreal n = 1,703; Toronto n = 2,015; Vancouver n = 1,737).

Municipal trust in procedural fairness is weakly significant for municipal context (). Montreal respondents from outer and regional municipalities had higher agreement while Vancouver outer municipal respondents had lower agreement as compared to the respondents from the inner/middle municipalities (). There are also weak significant differences for the competency factor interaction term. The violin plots show Montreal respondents indicated higher agreement than the other two regions across all municipal contexts, with an increasing trend from inner through regional municipalities (). Toronto respondents assigned lower agreement scores than the other two regions, while both Toronto and Vancouver respondents from outer municipalities have slightly lower average agreement as compared to those in other municipal contexts.

Across the five satisfaction factors, three show significant difference by region, but not municipal context or the interaction term: tree satisfaction ecology, management satisfaction timely, and management satisfaction sufficient (). For the ecology factor, Montreal has lower satisfaction scores for inner through outer municipalities than the other regions based on the violin plots (), and for timely Montreal has lower scores for middle municipalities, while Toronto has higher satisfaction from inner and middle municipality respondents. For the sufficient management factor, responses from Toronto gave slightly higher satisfaction scores for inner and middle, while Vancouver is lower for regional municipalities. Tree satisfaction amenity is weakly significant by municipal context, while management satisfaction appropriate has a weakly significant interaction term ().

Figure 5. Violin plots showing survey respondents level of satisfaction for statements loading on each of the urban forest satisfaction factors, aggregated by the four municipal contexts (inner, middle, outer, regional), in each of the three regions (Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver). The average (circle), median (line), interquartile range (box), and overall data distribution are depicted (Montreal n = 1,703; Toronto n = 2,015; Vancouver n = 1,737).

3.2. Language

The four values themes did not show significant differences associated with either of the language variables (). Similar to the geographic variables, there was more variation in responses for the two beliefs factors. For the first language variable (English or French speakers), those who spoke French at home had lower agreement with negative beliefs items and also slightly lower agreement with positive belief items (). For the second language variable, F/ESL speakers had slightly higher agreement with negative beliefs and similar agreement as non-F/ESL speakers for positive beliefs ().

Figure 6. Violin plots for survey responses to statements loading on each of the urban forest values, beliefs, trust and satisfaction measures, separated by English and French speakers. The average (circle), median (line), interquartile range (box), and overall data distribution are depicted (n = 5,455).

Figure 7. Violin plots for survey responses to statements loading on each of the urban forest values, beliefs, trust and satisfaction measures, separated by French or English as a second language (F/ESL) and non-F/ESL speakers. The average (circle), median (line), interquartile range (box), and overall data distribution are depicted (n = 5,455).

The trust competency factor was also significantly different for both language variables while trust in procedural fairness was only found to have a weak significant association with the official language variable (English or French speakers; ). Respondents whose primary language is French responded with higher agreement than English language responses/speakers, while F/ESL respondents had higher agreement than non-F/ESL respondents related to competency.

Interestingly, variations in satisfaction related to the language variables were minimal. There was no significant difference for tree amenity, while tree ecology satisfaction was significantly higher among English speaking respondents across all urban regions (). There was moderate to weak significance for timely management across both language measures: English language speakers and F/ESL has higher satisfaction than French language speaker and non-F/ESL respondents. F/ESL respondents also had higher satisfaction with appropriate management and English language speakers had higher satisfaction with sufficient management ().

4. Discussion

Understanding perceptions is one way to integrate the human drivers of ecosystems into policy and management. While public engagement and participation is important in specific decision-making and policy-development contexts (Baumeister et al. Citation2022; Zaman et al. Citation2022), large-scale assessments of perceptions are useful to help identify the range of human meanings associated with ecosystems, while providing a basis to further consider needs and different management strategies (Stern et al. Citation1995; Dietz et al. Citation2005; Avolio et al. Citation2015; Kendal et al. Citation2015; Díaz et al. Citation2018; Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019; Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022).

Using the Cognitive Model, which differentiates perceptions and constructs according to their level of abstraction and other characteristics, we were able to explore which perceptions are more uniformly held and which ones vary across populations. In particular, the different measures of urban forest perceptions have varied associations with region, municipal context, and language spoken. These results highlight the importance of considering multiple components of perceptions to have a fuller view of people’s cognitive associations, as well as illustrating the ways some perceptions may be more variable across populations. We discuss key findings below and then highlight implications for ecosystem management.

4.1. Key findings

The four value factors received moderate to high importance scores from most respondents, with social and natural values rated as more important than cultural or identity values. These results are similar to previous findings in Australia (Kendal et al. Citation2022), reinforcing the notion that people often hold multiple values related to the urban forest. Similarly, our finding that respondents have higher agreement with positive beliefs about trees than negative beliefs is also supported by previous studies (Lohr et al. Citation2004; Schroeder et al. Citation2006; Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019; Drew-Smythe et al. Citation2023). Finally, several of the trust and satisfaction factors have relatively broad response distributions indicating a high level of response variation, possibility illustrating the more individual nature of the measures, as compared to values and beliefs (Kendal et al. Citation2022).

Our results also indicate that perceptions held by people in different geographic areas may be varied, even within the same country, complementing differences found in other multi-national studies (Schroeder et al. Citation2006; Krajter Ostoić et al. Citation2017; Shackleton and Mograbi Citation2020). Alternatively, we found fewer significant differences in perceptions associated with language than expected, or as compared to previous research focusing on values (Egerer et al. Citation2019; Ordóñez Barona et al. Citation2022; Su et al. Citation2022). These findings are discussed in more detail below.

On the one hand, our hypothesis that values and beliefs would not vary with geographic setting but would vary by language spoken was not supported by the findings. Interestingly, there was variation in natural values by geographic setting, which may reflect differences in the importance of trees within the broader environment and/or characteristics of the trees themselves. Drawing on similar findings in Toronto, Su et al. (Citation2022), suggest people’s experiences with urban trees in less dense urban areas may translate into abstract perceptions that lean towards conserving the natural characteristics of these forests. Alternatively, people who already hold these perceptions may choose to live in these lower density contexts (Baumeister et al. Citation2022).

The differences in beliefs we found by municipal context, may more directly reflect experiences. For example, trees in inner urban cores may be more likely to have negative outcomes due to amplified urban stressors than trees in the lower-density outer municipalities (Kirkpatrick et al. Citation2012). Thus, the dominant discourse in inner urban cores may focus more on the negative aspects of urban trees (e.g. high tree mortality, higher risk of tree collapse, more tree-human-infrastructure conflicts; Kirkpatrick et al. Citation2012), and direct negative experiences may be more common as well (Zhang and Zheng Citation2011; Kirkpatrick et al. Citation2012; Baumeister et al. Citation2022). Further examination of residency characteristics, such as years in urban/rural areas and the ecological characteristics of these settings may help us better understand why such differences arise and the stability of these abstract perception measures.

Lower agreement with both negative beliefs and positive beliefs in Montreal, as compared to the Toronto and Vancouver regions, indicates regional differences that may partially reflect the difference in dominant language between Montreal and the other two regions. Previous research suggests that cultural differences underpin differences in urban forest perceptions between countries (Schroeder et al. Citation2006; Krajter Ostoić et al. Citation2017; Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019). In our work, French language speakers expressed lower agreement with both negative and positive beliefs and the dominance of French-speakers in Montreal provides support that cultural differences may underpin the regional variation.

Complementarily, our focus on Canada’s two official languages may have dampened differences in values due to cultural associations with languages, as other similar studies have examined language spoken classified by world region (Egerer et al. Citation2019; Su et al. Citation2022). Alternatively, the two languages we focused on share a Western/European cultural worldview. Language is also just one measure of identity. Further examination of characteristics of respondents, such as by complementing language spoken with ethnicity, immigration pathways, and other measures of cultural identity may help us better understand when perception differences arise at the individual level.

Our hypothesis that trust and satisfaction measures would vary by urban region and municipal context was also only partially supported, as there were few differences by municipal context. This is surprising because the municipal context reflects urban form, which potentially influences ownership patterns, canopy cover extent, and other socio-ecological characteristics of the urban forest. However, the municipal competency trust factor variation across urban regions reflects the greatest magnitude of difference between geographic settings for all perceptions measured.

Interestingly, while Montreal had the highest average agreement with the competency factor, respondents from Montreal gave lower satisfaction scores for two of the management satisfaction factors (timely and sufficient) in inner through outer municipalities. These findings broadly support our trust and satisfaction measures as capturing distinct aspects of perceptions. One possibility is that the trust measures are more reflective of people’s general trust in their local government, which may reflect broader governance dynamics between communities and their government institutions. On the other hand, satisfaction with management scores may be more specifically influenced by people’s day-to-day experiences with trees (Schroeder et al. Citation2006; Kirkpatrick et al. Citation2012).

Research on trust in Canada shows regional variations, with residents of Montreal, and the province of Quebec more broadly, often expressing particularly low levels of trust in institutions (e.g. banks, police) and generalized measures of community trust (Kazemipur Citation2006; Cotter Citation2015). Bridgman et al. (Citation2022) also found French speakers in Quebec expressed lower levels of social trust as compared to English speakers, opposite our findings. The difference may be because we asked about trust in the municipality rather than non-municipal institutions (Cotter Citation2015) or the commonly asked generalized social trust question (Bridgman et al. Citation2022). Additionally, Proof Strategies (Citation2022) report stronger levels of trust in both federal and provincial leaders and non-governmental institutions by Quebecers in 2022, which is aligned with our municipal-level findings. While French language speakers may express lower trust in general due to language-based exclusion and historical minority status at the national-level in Canada (Bridgman et al. Citation2022), speaking the official language throughout the Montreal urban region may support a stronger connection to local government that translates into greater trust in relation to urban tree decisions.

Fewer significant associations exist for satisfaction measures, suggesting these are less a reflection of geographic setting, broad cultural identity, or language-driven relationships with local government. It is possible that satisfaction is more aligned with individuals’ experiences with trees at neighborhood or property scales (Coleman et al. Citation2023). Some studies have found low or moderate satisfaction with urban trees or their management in multiple settings (Krajter Ostoić et al. Citation2017; Gwedla and Shackleton Citation2019), while others capture a diversity of satisfaction-levels (Kendal et al. Citation2022), suggesting regional variations exist in some contexts. However, the specific satisfaction measures have varied by study, which limited comparisons. More research should explore our concrete measure of satisfaction at finer scales to better understand the role of local trees on satisfaction with trees and their management.

4.2. Implications for management

Understanding peoples’ perceptions enriches urban ecosystem management by enhancing knowledge about how people assign meaning to what they experience, as well as what they desire from the ecosystem and its management. Inclusion of this information into management can support both people and ecological features (Jones et al. Citation2013).

The variations in responses between our perception measures illustrate that positive perceptions of an ecosystem in general may not translate into equally positive perceptions of its management, and there may be variation even within perception types. This was clear from our findings related to higher satisfaction with trees and lower satisfaction with their management. Understanding these nuances can inform development of urban ecosystem management objectives to ensure support by and for local populations. For example, our respondents expressed relatively high importance for social and natural values over cultural and identity values, which suggests prioritizing management to support social interactions and ecologically healthy urban forests. In practice, this could be reflected in objectives like designing public spaces with seating next to trees and planting species that support native wildlife.

Incorporating an understanding of public perceptions also supports management that can address more than just the most common perception, providing guidance on how to develop and implement differential management objectives and strategies. For example, our findings about beliefs show people who live in inner urban areas are more likely to have negative beliefs about trees. This suggests tree risks and disservices need to be proactively managed in these areas to minimize public complaints, alongside providing information about how to successfully steward trees and reduce disservices in denser urban locations. Such information may be less relevant to people living outside urban areas because they have less agreement with negative beliefs about trees, so should not be a prioritized objective.

Our findings related to attitudes, which refer to the concrete ways people are disposed towards ecosystems, can be used to identify more immediate urban forest management issues. The satisfaction with the way public institutions make decisions about trees finding supports the need for greater outreach and participatory decision-making processes to ensure ongoing public support for management. More specifically, our findings demonstrate that language spoken is related to trust in the competency of government decision-makers. Thus, urban forest managers need to engage diverse groups through communication channels that are not limited to the official language; communicating in the languages people primarily speak will potentially reach different audiences and support a process of trust building.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to our understanding of the multiple ways people perceive urban forests, and how they differ across geographic settings and by language spoken, even within the same country. Key findings included geographic and language-based differences for beliefs about trees and trust in local decision-makers, but fewer differences for values people hold about trees or their satisfaction with trees or their management. When significant differences occur by geographic setting, region was more frequently associated with response differences than the urban context. Our findings indicate the need to understand multiple perceptions to identify key urban ecosystem management objectives that support people and trees. For urban forest managers, addressing negative beliefs in denser urban areas through tree stewardship and education is more important than in less built-up environments. Finally, participatory decision-making that can incorporate people who speak different languages is important to increase satisfaction with management and build trust.

Our study included survey data that had consistent measures of perception responses, but we lacked comparable data on other socio-ecological aspects of the urban forest, such as characteristics of the urban forest itself. Future research should examine how urban forest conditions (e.g. abundance, diversity) may influence community perceptions. This study was also conducted towards the end of and after COVID-related restrictions were lifted, so future research could explore whether perceptions change as we move further from COVID-19 pandemic-related effects.

As municipalities work to grow the urban forest to increase human health and wellbeing, our findings add to the growing body of literature that indicates different populations perceive urban forests in various ways. Many of these perceptions are not universal. Understanding local perceptions is important to assess community support and anticipated benefits. Finally, on-going communication with communities in multiple languages, and stronger community participation programs in urban forestry, may help transform some negative perceptions into positive ones and build stronger relationships between local governments and communities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2024.2355272

Additional information

Funding

References

- Avolio ML, Pataki DE, Pincetl S, Gillespie TW, Jenerette GD, McCarthy HR. 2015. Understanding preferences for tree attributes: the relative effects of socio-economic and local environmental factors. Urban Ecosyst. 18(1):73–18. doi: 10.1007/s11252-014-0388-6.

- Baumeister CF, Gerstenberg T, Plieninger T, Schraml U. 2022. Geography of disservices in urban forests: public participation mapping for closing the loop. Ecosyst People. 18(1):44–63. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2021.2021289.

- Bridgman A, Nadeau R, Dietlind S. 2022. A distinct society? Understanding social distrust in Quebec. Can J Polit Sci. 55(1):107–127. doi: 10.1017/S0008423921000780.

- Coleman AF, Eisenman TS, Locke DH, Harper RW. 2023. Exploring links between resident satisfaction and participation in an urban tree planting initiative. Cities. 134:104195. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2023.104195.

- Conway TM, Bang E. 2014. Willing partners? Residential support for municipal urban forestry policies. Urban For Urban Greening. 13(2):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2014.02.003.

- Conway TM, Hackworth J. 2007. Urban pattern and land cover variation in the Greater Toronto Area. Can Geogr. 51(1):43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2007.00164.x.

- Coscieme L, Hyldmo HD, Fernández-Llamazaresc A, Palomo I, Mwampambae TH, Selomane O, Sitas N, Jaureguiberry P, Valle M, Lim M. 2020. Multiple conceptualizations of nature are key to inclusivity and legitimacy in global environmental governance. Environ Sci Policy. 104:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.10.018.

- Cotter A. 2015. La confiance du public envers les institutions canadiennes. Mettre l’accent sur les Canadiens: résultats de l’Enquête sociale générale. Statistique Canada. https://www.ledevoir.com/documents/pdf/statcan_confiance.pdf.

- Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López B, Watson RT, Molnár Z, Hill R, Chan KM, Baste IA, Brauman KA. 2018. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science. 359(6373):270–272. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8826.

- Dietz T, Fitzgerald A, Shwom R. 2005. Environmental values. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 30(1):335–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144444.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. 2014. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. Fourth ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley and Sons, Inc; p. 528.

- Dobbs C, Nitschke CR, Kendal D, Davies ZG. 2014. Global drivers and tradeoffs of three urban vegetation ecosystem services. PLOS ONE. 9(11):e113000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113000.

- Drew-Smythe JJ, Davila YC, McLean CM, Hingee MC, Murray ML, Webb JK, Krix DW, Murray BR. 2023. Community perceptions of ecosystem services and disservices linked to urban tree plantings. Urban For Urban Greening. 82:127870. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2023.127870.

- Egerer M, Ordóñez C, Lin BB, Kendal D. 2019. Multicultural gardeners and park users benefit from and attach diverse values to urban nature spaces. Urban For Urban Greening. 46:126445. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126445.

- FAO. 2016. Guidelines on urban and peri-urban forestry. Forestry paper No. 178. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations; [accessed 2022 Dec]. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6210e.pdf.

- Gwedla N, Shackleton CM. 2019. Perceptions and preferences for urban trees across multiple socio-economic contexts in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Landsc Urban Plan. 189:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.05.001.

- Hair JJ, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. 2014. Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition. 7th ed. pp. 846. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Education.

- Jay M, Schraml U. 2009. Understanding the role of urban forests for migrants: uses, perception and integrative potential. Urban For Urban Greening. 8(4):283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2009.07.003.

- Jenerette GD, Clarke LW, Avolio ML, Pataki DE, Gillespie TW, Pincetl S, Nowak DJ, Hutyra LR, McHale M, McFadden JP, et al. 2016. Climate tolerances and trait choices shape continental patterns of urban tree biodiversity. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 25(11):1367–1376. doi: 10.1111/geb.12499.

- Jones RE, Davis KL, Bradford J. 2013. The value of trees: factors influencing homeowner support for protecting local urban trees. Environ Behav. 45(5):650–676. doi: 10.1177/0013916512439409.

- Kaiser HF. 1974. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 39(1):31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02291575.

- Kazemipur A. 2006. A Canadian exceptionalism? Trust and diversity in Canadian Cities. J Int Migr Integr. 7(2):219–240. 22. doi: 10.1007/s12134-006-1010-4.

- Keele L. 2007. Social capital and the dynamics of trust in government. Am J Pol Sci. 51(2):241–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00248.x.

- Kendal D, Ford RM, Anderson NM, Farrar A. 2015. The VALS: a new tool to measure people’s general valued attributes of landscapes. J Environ Manage. 163(Supplement C):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.017.

- Kendal D, Ordóñez C, Davern M, Fuller RA, Hochili DF, van der Ree R, Livesley SJ, Threlfall CG. 2022. Public satisfaction with urban trees and their management: the role of values, beliefs, knowledge, and trust. Urban For Urban Greening. 73:127623. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127623.

- Kirkpatrick JB, Davison A, Daniels GD. 2012. Resident attitudes towards trees influence the planting and removal of different types of trees in eastern Australian cities. Landsc Urban Plan. 107(2):147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.015.

- Krajter Ostoić S, Konijnendijk van den Bosch CC, Vuletić D, Stevanov M, Živojinović I, Mutabdžija-Bećirović S, Lazarević J, Stojanova B, Blagojević D, Stojanovska M, et al. 2017. Citizens’ perception of and satisfaction with urban forests and green space: results from selected Southeast European cities. Urban For Urban Greening. 23:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.02.005.

- Landry SM, Chakraborty J. 2009. Street trees and equity: evaluating the spatial distribution of an urban amenity. Environ Plan A. 41(11):2651–2670. doi: 10.1068/a41236.

- Landry F, Dupras J, Messier C. 2020. Convergence of urban forest and socio-economic indicators of resilience: a study of environmental inequality in four major cities in eastern Canada. Landsc Urban Plan. 202:103856. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103856.

- Levi M, Stoker L. 2000. Political trust and trustworthiness. Annu Rev Polit Sci (Palo Alto). 3(1):475–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475.

- Lohr V, Pearson-Mims C, Tarnai J, Dillman D. 2004. How urban residents rate and rank the benefits and problems associated with trees in cities. Arboric Urban For. 30(1):28–35. doi: 10.48044/jauf.2004.004.

- O’Brien LE, Urbanek RE, Gregory JD. 2022. Ecological functions and human benefits of urban forests. Urban For Urban Greening. 75:127707. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127707.

- Ordóñez Barona C, Wolf K, Kowalski JM, Kendal D, Byrne JA, Conway TM. 2022. Diversity in public perception of urban forests and trees: a critical review. Landsc Urban Plan. 226:104466. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104466.

- Pham T-T-H, Apparicio P, Landry S, Lewnard J. 2017. Disentangling the effects of urban form and socio-demographic context on street tree cover: a multi-level analysis from Montréal. Landsc Urban Plan. 157:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.09.001.

- Proof Strategies. 2022. CanTrust index- 2022 report. https://proofagency.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Proof-Strategies-CanTrust-Index-2022.pdf.

- Quinton J, Nesbitt L, Czekajlo A. 2022. Wealthy, educated, and … non-millennial? Variable patterns of distributional inequity in 31 Canadian cities. Landsc Urban Plan. 227:104535. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104535.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Rosner B, editor. 2015. Fundamentals of biostatistics 888. Boston (MA): BrooksCole.

- Rossi SD, Byrne JA, Pickering CM, Reser J. 2015. ‘Seeing red’ in national parks: how visitors’ values affect perceptions and park experiences. Geoforum. 66:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.009.

- Schroeder H, Flannigan J, Coles R. 2006. Residents’ attitudes toward street trees in the UK and US communities. J Arboricult Urban For. 32(5):236–246. doi: 10.48044/jauf.2006.030.

- Schultz PW, Zelezny L. 1999. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J Environ Psychol. 19(3):255–265. doi: 10.1006/jevp.1999.0129.

- Shackleton CM, Mograbi PJ. 2020. Meeting a diversity of needs through a diversity of species: urban residents’ favourite and disliked tree species across eleven towns in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Urban For Urban Greening. 48:126507. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126507.

- Statistics Canada. 2021a. Citizenship, place of birth, and immigrant status for the population in private households of Canada in Census Metropolitan Areas, 2016. [accessed 2022 Dec]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/98-500/007/98-500-x2021007-eng.cfm.

- Statistics Canada. 2021b. Population and dwelling counts, Canada, provinces, and territories. [accessed 2022 Mar]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810000101.

- Statistics Canada. 2021c. Visible minority person – definition and statistics. [accessed 2022 Jan]. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DECandId=45152.

- Stern PC, Kalof L, Dietz T, Guagnano GA. 1995. Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J Appl Soc Psychol. 25(18):1611–1636. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02636.x.

- Su K, Ordóñez C, Regier K, Conway TM. 2022. Values and beliefs about urban forests from diverse urban contexts and populations in the Greater Toronto Area. Urban For Urban Greening. 72:127589. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127589.

- Taylor C. 1994. Multiculturalism 192. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

- Threlfall CG, Gunn LD, Davern M, Kendal D. 2022. Beyond the luxury effect: individual and structural drivers lead to ‘urban forest inequity’ in public street trees in Melbourne, Australia. Landsc Urban Plan. 218:104311. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104311.

- Tung VWS, Ritchie JRB. 2011. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann Tour Res. 38(4):1367–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.009.

- Turner-Skoff JB, Cavender N. 2019. The benefits of trees for livable and sustainable communities. Plants People Planet. 1(4):323–335. doi: 10.1002/ppp3.39.

- Tyrväinen L, Ojala A, Korpela K, Lanki T, Tsunetsugu Y, Kagawa T. 2014. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J Environ Psychol. 38:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.005.

- van den Berg MM, van Poppel M, van Kamp I, Ruijsbroek A, Triguero-Mas M, Gidlow C, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Gražulevičiene R, van Mechelen W, Kruize H. 2019. Do physical activity, social cohesion, and loneliness mediate the association between time spent visiting green space and mental health? Environ Behav. 51(2):144–166. doi: 10.1177/0013916517738563.

- Whitburn J, Linklater WL, Milfont TL. 2019. Exposure to urban nature and tree planting are related to pro-environmental behavior via connection to nature, the use of nature for psychological restoration, and environmental attitudes. Environ Behav. 51(7):787–810. doi: 10.1177/0013916517751009.

- Wolf KL, Lam ST, McKeen JK, Richardson GR, van den Bosch M, Bardekjian AC. 2020. Urban trees and human health: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(12):4371. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124371.

- Zaman S, Korpilo S, Horcea-Milcu A-I, Raymond C. 2022. Associations between landscape values, self-reported knowledge, and land-use: a public participation GIS assessment. Ecosyst People. 18(1):212–225. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2022.2052749.

- Zhang Y, Zheng B. 2011. Assessments of citizen willingness to support urban forestry: an empirical study in Alabama. Arboric Urban For. 37(3):118–125. doi: 10.48044/jauf.2011.016.