ABSTRACT

There is very little academic work on music in television series, and none on music in French television series. This article focuses on one of the most successful French television series, the eight-season-long Engrenages/Spiral (Canal+, 2005–2020). It identifies the similarities and differences between music for films and music for television series before focusing on the music composed by Stéphane Zidi for Engrenages. This combines the unusual use of gamelan instruments as musical cues with more melodic piano themes. Arguing that television series music, which might have been even more ‘unheard’ than film music, functions to shape audience perception of the characters, the article focuses on the specificities of gamelan cues and piano themes. The piano themes migrate from one character to another across the eight seasons of the series, and the article shows how this affects the narrative arc of the main character, Laure Berthaud, emphasising her rejection of (both) the conflicting roles of mother and leader.

Music in films, to reprise Claudia Gorbman’s well-known assertion, is typically unheard (Citation1987). Spectators, it is assumed, are likely to pay considerably more attention to the visual track in its construction of a narrative; the music is quite literally an accompaniment. Arguably this is even more the case for television series whose music tends to occur in short, frequently repeated bursts that are generally shorter than musical cues in films. Their function, it would seem, is to act as little more than punctuation, emphasising what spectators see in a relatively unobtrusive fashion. Unlike some films, where music is as important as the visual track – film musicals come to mind, but this is not confined to them – there are rarely musical set pieces in most television crime series. User reviews for Engrenages/Spiral (Canal+, 2005–2020), which is the focus of this article, bear this out. They do not comment significantly on the music, despite the longevity and popularity of the series. It was broadcast in 19 countries and won the International Emmy Award for Best Series in 2015, despite being a crime series firmly located in a French, indeed intensely Parisian, context with complex references to specifically French police and judicial procedures. Of the 111 user reviews on the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), only one – which gives the series 10/10 – mentions the music, and then suggests in an unfinished comment that the music is one of the series’s ‘imperfections’: ‘It is not perfect in every way – there might be minor production imperfections here and there, the music/soundtrack is not all that [sic], but the quality of everything else overshadows any minor blemishes’ (‘Cremebluray’ Citation2015). Of the 107 user reviews on the French equivalent of the IMDb, the website AlloCiné, only four mention the music, and then in passing to say somewhat unspecifically that it is good, one praising every aspect of the series, ‘even the music’, as if we might have expected the music to be bad or inconsequential. One appears to criticise the music, saying that is too basic [primaire] (LeJoker Citation2021), something I shall return to.Footnote1

Within the well-established field of music in screen studies and its attempt to make music ‘heard’, the aim of this article is twofold. Unlike academic work on film music, work on the music in television series is sparse.Footnote2 A first aim then is generic and contextual; using Engrenages as an example, it is to explore how television series music is both similar in function to film music while being distinct in specific ways. It is more repetitive, more stereotyped, and as a result arguably less imaginative and even less likely to be ‘heard’ than film music, as the user reviews mentioned above demonstrate. Its function is to bind the disparate narrative elements together, with the title theme acting as the crucible for a range of musical cues. A second aim of this article is to explore aspects of differentiation within this generic binding function. Close analysis of the musical cues shows how they can move beyond the stereotypical function of emphasising what we see – expressing character motivation or the implications of an event for example – to a more complex intensification of the narrative. The expressive function in Engrenages is largely confined to musical cues, whereas the intensive function is largely conveyed through themes.

Robynn Stilwell’s description of a theme variation as something different from a character theme and functioning more as ‘an atmospheric cue that gives a sense of mood, location, or ambience’ (Citation2011, 123) is what I understand as a musical cue. These are brief musical phrases serving to emphasise narrative events such as the police chasing criminals, or developments in character relationships such as an argument or a romantic interlude. A theme on the other hand is, in the words of Matthew Bribitzer-Stull,

a unique entity, differentiated from its musical context, and significant enough to elicit notice. To do so, a theme must employ (and retain) a variety of identifiable musical parameters. These may include, but are not limited to: contour, rhythmic content, pitch content, length, orchestration, texture, register, tempo, harmonic progression, harmonic function, and contrapuntal framework. (Bribitzer-Stull Citation2015, 34; my emphasis)

Two specificities in the music of Engrenages ‘elicit notice’. First, the unusual and extensive use of gamelan instruments as the basic tonal and percussive landscape of the series’s musical cues; second, and in marked contrast to the gamelan instruments, both in terms of timbre (tone quality) and frequency (quantity of cues), the use of melodic piano themes. The piano themes discussed below are differentiated from the gamelan tones of most of the musical cues and they have the melodic contours that the more percussive gamelan sounds do not. They ‘elicit notice’, as Bribitzer-Stull (Citation2015) puts it, precisely because of these features. The piano themes elicit notice for a second reason: initially attached to specific characters, they migrate to other characters in ways that shape audience perception of the narrative. They constitute what I have called crystal-songs (Powrie Citation2017), as I shall discuss below, their importance made all the more obvious by the contrast with the gamelan cues.

Unheard music in television series

It is worth rehearsing the differences between films and television series so as to identify how music’s binding function mentioned above – what might make the music ‘unheard’ – is necessary for the emergence of musical themes that ‘elicit notice’ from the ground of musical cues.

The major difference between films and television series is the latter’s extended form. Engrenages comprises eight seasons (2005–2020). However, unlike previously long-running and popular French television crime series, such as Navarro (TF1, 1989–2007), Maigret (Antenne 2/France 2, 1991–2005) or Commissaire Moulin (TF1, 1976–2006), with their single-episode narratives, Engrenages, much like the Corsican-based crime series Mafiosa (Canal+, 2006–2014), has long story arcs – the main one being the relationship between the two central characters, Laure and Gilou – with season-long story arcs, such as the hunt for a serial killer in Season 3 followed in Season 4 by the hunt for anti-government extremists. This structure has become the standard structure for crime series both in France (for example Braquo [Canal+, 2009–2016]; Les Témoins/Witnesses [France 2, 2015–2017]; Le Bureau des légendes/The Bureau [Canal+, 2015–2020]) and elsewhere (for example the Danish/Swedish co-production Bron/Broen/The Bridge [Danmarks Radio, 2011–2018]; Line of Duty [BBC, 2012–2021] in the UK).

The eight seasons of Engrenages, like other long-form series, develop a complex narrative, with narrative elements stretching across several episodes, across whole seasons and, in the case of the major characters, across several seasons, with the narrative arcs of the top three characters – Laure, Gilou and Joséphine – stretching across all eight seasons. This is not the only aspect of complexity. Engrenages has an extensive series world with approximately 200 characters occurring in more than two episodes, and 20 characters occurring in more than one season, leading to a broad range of characters with complex and extensive storylines. This leads to the ‘centrifugal complexity’ characteristic of complex television, a lack of a ‘narrative centre as the action traces what happens between characters and institutions as they spread outward’ (Mittell Citation2015, 222). As Kevin Donnelly points out, television is a ‘tessellated form’ (Citation2005, 111) which is built on discrete moments, even more obviously so in the case of television series:

Television is dominated less by developmental drama, as in films, but more by momentary dramatic instants. Television is fragmented within a continuous ‘flow’. This tessellated form obviates the need for lengthy sections of music designed to build continuity and reaction through successive progression. Instead, what is required is that certain moments are emphasised, noted as significant, monumentalised and aestheticised. (Donnelly Citation2005, 111)

Music’s function in a television series is much the same as in a film. It supports and punctuates what we see (Donnelly Citation2005, 113). It can separate scenes; to use the analogy of written punctuation, this might be a full stop equivalent. It can create a bridge between them, as the focus changes from one space or temporal moment to another; this would be a hyphen equivalent. In its supporting function it emphasises action and character emotions with an exclamation mark equivalent.

However, as Donnelly intimates, musical cues tend to be shorter in television series than in films, and they are more often than not musical blocks, i.e. a small set of musical themes established early on in a series and frequently repeated, not least because they accompany frequently repeated stock situations from one episode or season to the next. As a result, arguably television series music is likely to be even less ‘heard’ than film music, something that is reinforced by viewing conditions; Christopher Wiley comments on the ‘cultural tendency for viewers to be less consistent in the level of attention devoted to the (typically domestic) activity of watching television’ (Citation2011, 40). As Donnelly points out, ‘the music comes to represent the idea behind the action more than it supports the action itself’ (Citation2005, 124). This is particularly the case for surveillance and pursuit events in Engrenages, in which the music often repeats the second phrase of the title music, which I will explore below, making the event less specific and more generic as a repetition of the principal motivation of the main characters: the pursuit of lawbreakers. That said, tessellation and centrifugal fragmentation are counterbalanced by the frequently repeated musical blocks; these have a homogenising function, returning disparate narrative elements to a common musical grounding which binds them together. This function is helped by the fact that musical cues are relatively minimalist and frequently subdued, as is common in television series from the 1990s onwards. This is no doubt the reason why one user review complained that the music was ‘basic’.

The title sequence is the second major difference between a film and a series, as it always prefaces each episode, whereas a film’s title sequence only occurs once. Considerable work has been done on film title sequences.Footnote3 The major points made in relation to them are first that they function as paratexts, separate from the film while at the same time representing the film. Stanitzek and Aplevich points out how they are a ‘a locus of division: manifold differentiation somehow bridged by fragile techniques of reintegration’ (Citation2009, 44–58). Second, particularly after the pioneering work of Saul Bass in the 1950s and early 1960s, who ‘found ways to symbolically represent each film […] as a concise sign, almost a logo itself’ (Stanitzek and Aplevich Citation2009, 54), title sequences became increasingly inventive. Indeed, Stanitzek and Aplevich suggest that the title sequence in ‘even the most conventional of Hollywood movies’ can become ‘a miniature experimental film’ (Citation2009, 50).Footnote4 The same points apply to television series title sequences: they are separate while being integrated in what follows, even more so because, more frequently than in films, they often occur after a pre-credits sequence, as is the case in Engrenages; and they can be as inventive as film title sequences, as we shall see in the case of Engrenages, whose title music, as is often the case with television series, introduces musical elements that will subsequently return in the musical cues.

Work on television series title sequences has been increasing, although little has been done on the way that they set up the musical landscape.Footnote5 Engrenages’s title sequence in visual terms consists of a swirling mass of coloured letters, from which the actors’ names, series producers and finally the series title and season emerge in white. The design remained the same across all eight seasons, although the colour scheme changed: gold swirling letters for Seasons 1 and 2 and blue letters for Season 3, both on black backgrounds, followed by burgundy letters for the remaining seasons on textured backgrounds.Footnote6 The graphic play with the series title is relatively uncommon.Footnote7 While not what Stanitzek labels epideixis, ‘an exuberant cinematic celebration’ (Citation2009, 50), it is nonetheless an example of when ‘writing itself becomes image […] a moving image within an image’ (Stanitzek and Aplevich Citation2009, 56). As Monika Bednarek points out for such ‘non-narrative’ title sequences (Citation2014, 134), the use of graphic design can be sufficiently inventive that ‘music and visuals often combine to co-create meaning’ (Citation2014, 138). In the case of the title sequence for Engrenages, the spiralling letters work with the music to suggest the complex interrelations between the main characters, whose lives keep on criss-crossing professionally and affectively.

The music is structured in two sections. First there is a slow ascending motif (), which is then picked up by fast spiralling strings over a descending phrase with a melancholic semi-tonal chromatic cadence (). The Canal+ advertisement for Season 8 talks of the notes swirling and gradually resolving into an image of interlocking cogs (Canal+ Citation2020). The two motifs together arguably gesture at the series’s title; the French term engrenage in its concrete meaning indicates the meshing of two cogwheels to create movement (a gear in English), and in its figurative sense the inevitability of a situation, as for example in l’engrenage de la violence, this latter meaning leading to the English version of the title, spiral, as can be surmised from the common phrase ‘a spiral of violence’. As Janet McCabe explains, the French term

translates literally to ‘gearing’ – referring to the grinding cogs of the criminal justice process and the hidden, often corrupt, exercise of its power: wheels within wheels. It is also an expression denoting a kind of vortex from where there is no escape, and Engrenages certainly involves a swirling narrative that deals with crime, institutional cynicism and corruption where everything is inextricably entangled and everyone implicated. (McCabe Citation2012, 101)

The French term accurately identifies a key theme of the series, the interlocking, as in a puzzle, of police and criminals in cycles of violence and the gradual ‘descent’ of police methods into illegality. Cycles are, as we shall see below in relation to the gamelan music, an important component of the music.

Many of the musical cues of the series reference the two motifs of the title sequence, either directly in snippets, or in more extensive musical developments. When this does not happen, the cues often recall elements of the title music, by inverting or reversing the motifs, or using similar musical intervals. The referencing of the title music in this way is sufficiently unusual for a television series to be noticeable. The two motifs – the ascent and the descent – echo the situations the characters encounter, such as confusing evidence or political intrigue and the effect that this has on their respective teams. The first motif, which remains in the spiralling strings of the second part of the title music, also contributes to the sense of an extensive but inward-focused social network which is as dysfunctional as it is functional.

There are almost 1200 musical cues and themes over the eight seasons of Engrenages. Many of them, as mentioned above, recall either directly or indirectly the two motifs of the title sequence, with the exception of the piano themes, binding ‘tessellated’ narrative elements together. Most of the cues use gamelan instruments, and generally occur in what the composer Stéphane Zidi describes as repeated Philip Glass-like minimalist blocks.Footnote8 These are variously used in ways we might expect: to accompany moments of excitement, for example in surveillance and chase sequences; to emphasise moments of heightened emotion or relational intensity; and most frequently to bridge and bind two consecutive sequences, binding and bonding what we see on screen at both the micro level of individual narrative elements as well as the macro level of a season or a sequence of seasons. Given this binding function, then, it would be understandable that the music does not need to be ‘heard’, and that it does no more than act as muted support for screen activity. The second part of this article aims to demonstrate various ways in which this is not the case, and that hearing the music adds otherwise hidden layers of meaning to the series.

Hearing the music in Engrenages

There are significant specificities in the musical cues of Engrenages, three of which I will consider here. The first is their frequency relative to the cuing of characters; cues generally accompany the arrival of a particular character on screen, or the representation of a sudden emotion they might be feeling, thus drawing attention to that character and creating an ‘association of the music with the sight of the character in a shot’ (Gorbman Citation1987, 83). Second, instrumentation; in the case of Engrenages, as mentioned above, gamelan instruments are extensively used. Frequency and instrumentation are two aspects common to all television series. Third, I shall also consider something in Engrenages which is less common: the migration of themes – in this case piano themes – as they detach from the character we might have associated with them so as to reattach to another.

Musical cues in Engrenages vary in number according to the season (). The final three seasons have a much greater number than the first five, which underscores the increasingly melodramatic developments in the relationship between the two characters who gradually become the principal focus of the series, Laure and Gilou.

Table 1. The number of musical cues and themes in Engrenages by season.

There is a significant quantitative differentiation of such cues, however. The main characters have a very different number of musical cues and themes associated with them across the eight seasons ().

Table 2. The number of musical cues and themes associated with the main characters across the eight seasons of Engrenages.

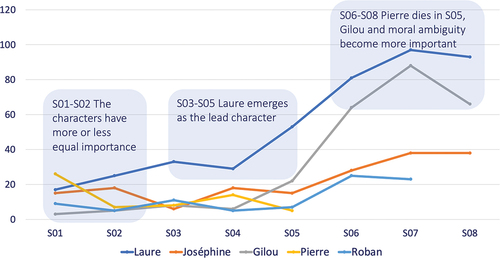

Moreover, the number and type of musical cues and themes linked to the main characters vary in individual seasons and across all the seasons, subtly conditioning audience response to those characters whether as individuals or in their relationships with other characters (see ). The most obvious shift is in Season 1, where we see that the prosecutor Pierre is accorded more musical support than Laure, who only becomes the series’s focal character from Season 2. A second marked shift occurs in Season 7, where Gilou has only nine fewer cues than Laure. It is not difficult to understand why this is the case: Pierre is narratively more important in Season 1, while by Season 7 and after Pierre’s death at the end of Season 5, Laure’s relationship with Gilou has become the central focus.

Table 3. The number of musical cues and themes per character per season in Engrenages.

The music’s frequency tells us, unsurprisingly, that some characters are more important than others in narrative terms, reinforcing what we see happening in the narrative. The series focuses on a small group of characters and their complex relationships, in particular Laure and Gilou, Pierre and Laure, and then Pierre and Joséphine. The number of cues accorded different characters encourages us to see Laure, Gilou and Joséphine as the more important characters in the narrative. However, this does not happen straightaway in the series, as we can see from the cues accorded the main characters by season (). While Laure emerges very quickly as the focal character from Season 2 onwards, the series takes some time, musically speaking, to give Gilou equal prominence in Season 5. In the first two seasons the characters have equal narrative importance. But gradually Laure emerges as the lead character, especially once Pierre half-way through Season 5, at which point the relationship between Laure and Gilou takes over as the most important relationship, its romantic basis melodramatically and musically more evident than in Seasons 1–5, and its underpinning in dubious moral and relational ambiguities to the fore.

Figure 3. The number of musical cues and themes per character across the eight seasons of Engrenages.

We could argue that this first specificity of musical cues and themes, that of frequency relative to character, is not unusual and that the frequency of the cues and themes does no more than underscore, quite literally, what the narrative is already telling us. As Kathryn Kalinak puts it, music in television series does little more than anchor the image, ‘encoding specific emotions through musical associations already operant in the culture’ (Citation1995, 89). It seems self-evident that the more a character becomes important, the more frequently they appear on screen, and therefore the more music is attached to them. The two following specificities, however, instrumentation and the migrating motif, are unusual and, to reprise Bribitzer-Sull (2015), ‘elicit notice’ in ways that frequency might not.

Most of the musical cues in the series use the tonalities of Javanese gamelan instruments, such as the bell-like gongs (bonang, kempul and kenong) and the xylophone-like metallophones (gender, saron and slenthem). Zidi chose these instruments for their other-worldly atmosphere,Footnote9 echoing the well-known use of gamelan tonalities and rhythms by French composers, starting with Debussy.

The historical context of the use of gamelan in Western music is revealing for an understanding of how Zidi uses it in Engrenages. Debussy had been fascinated by the Javanese music he heard at the Exposition universelle of 1889 in Paris. His Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) was written at the same time and shows the influence of Javanese music in his use of the pentatonic scale (Mueller Citation1986). However, it is a later piece with its curiously Chinese associations, Pagodes (1903), that demonstrates that influence more fulsomely with its pedal notes imitating the gong ageng (Parker Citation2012). Debussy was not the only French composer influenced by gamelan. Erik Satie, who had visited the same Exposition, used gamelan tonalities in his 1893 Gnossiennes (Orledge Citation1990, 190), as did Maurice Ravel in ‘Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes’ from his 1910 suite Ma mère l’Oye, telling an interviewer that the piece with ‘its tolling of temple bells, was derived from Java both harmonically and melodically’ (Orledge Citation2000, 29). Francis Poulenc heard gamelan music at the 1931 Exposition coloniale in Paris, and incorporated elements in his 1932 Concerto pour deux pianos (Reed Citation1999, 354). Olivier Messiaen’s work shows many gamelan influences (Puspita Citation2008), for example in Réveil des oiseaux for orchestra, piano and gamelan (1953), Oiseaux exotiques, again for orchestra, piano and gamelan (1956), Des canyons aux étoiles for orchestra, piano, French horn and gamelan (1974) and Un vitrail et des oiseaux for orchestra, piano and gamelan (1986), as well as one of his signature works, the 10-movement Turangalîla-Symphonie of 1949. Gamelan in Engrenages, then, for all its non-Western tonalities, is both familiar musically, as well as arguably – given the aforementioned composers’ links with the Parisian music scene – being appropriately Parisian, matching the Parisianness of the locations.

The influence of gamelan goes well beyond France, of course. Benjamin Britten, Béla Bartók, György Ligeti and Colin McPhee, amongst art music composers, have incorporated gamelan into their compositions, as well as popular music composers such as Mike Oldfield and Robert Fripp. Of particular interest in relation to Zidi’s use of gamelan is the work of minimalist composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich. As we saw above, Zidi has mentioned Glass when talking about the blocks of music composed for Engrenages.Footnote10 There is a significant difference however between Zidi’s version of gamelan and that of all the composers I have mentioned, from Debussy to Glass. Their use of gamelan is faithful to its polyphonic structures, whereas Zidi’s cues are monophonic. As we shall see, this has implications for the way we might understand the characters and their situation.

One of the main features of gamelan is its polyphonic structures, or more accurately its ‘rhythmically stratified polyphony’ (Tilley Citation2020, 266; emphasis in original). Whether one considers Debussy’s gong-like pedal notes overlayed with rapid fluctuating layers in Pagodes or Reich’s complex cyclical interlocking rhythms – for example in his 1973 Music for Pieces of Wood (Tenzer Citation2019) – the impression given is of at least two, if not more, layers of rhythm and music working together. There are ideological implications to this. Sylvia Parker points out that ‘the balanced heterophony among the various melodies reflects Javanese society, in which restrained behavior and smooth interactions are valued’ (Citation2012); the main French specialist on gamelan, Catherine Basset, points out that gamelan works towards ‘detachment from the ego and a strong sense of the collective body, an ineffable sense of being an undifferentiated part of the whole’Footnote11 (Citation2010, 148).

Zidi’s cues, however, are nearly all monophonic, generally consisting of a single gamelan instrument with a rhythmic beat. Given Engrenages’s focus on the interlocking cog-like relationships between police, lawyers and criminals, we might have expected heterophonic gamelan-related cues. The effect of the monophonic motifs is twofold: they frequently function in musical terms as the same kind of drone found in Indian music (for example with the large lute-like tanpura or the box-accordion surpeti), establishing a tonic ground or base which would normally be provided by the different notes of a scale in Western music (Courtney Citation2022). This first effect is one of bleakness that matches the gritty realism of the series. Correlatively, the second effect is one of dystopian loneliness. Whereas the polyphony of typical gamelan is a manifestation of a functioning community, so the monophony of gamelan in Engrenages arguably encourages us to see the characters as individual figures within a larger dystopian canvas.

We should not lose sight however of the main function of gamelan music: the manufacturing of otherworldly mystery, as Zidi indicates.Footnote12 Gamelan is frequently used in films to indicate exotic local colour in the narrative, for example in Bernard Herrmann’s score for Anna and the King of Siam (John Cromwell, 1946), which he described as ‘musical scenery’ (Smith Citation2002, 125), Alex North’s score for Cleopatra (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1963) or Jerry Goldsmith’s score for the China Seas-based The Sand Pebbles (Robert Wise, 1966). Gamelan is also used to indicate the mystery of other worlds, as in Mychael Danna’s music for The Time Traveller’s Wife (Robert Schwentke, 2009), especially in the pieces ‘I’m You Henry’, ‘Testing’, ‘Meadow’, complementing the piano-dominated score; or James Horner’s score for Avatar (James Cameron, 2009), in which he mixes gamelan with other ethnic instruments so as to create ‘a fusion of different worlds’ (Boucher Citation2015).

Unlike these examples, however, which are fleeting textural brushstrokes in a broader musical landscape comprising other ‘exotic’ instruments, gamelan in Engrenages is sustained throughout the eight seasons as the main sound. We could argue that a point is being made about a multi-ethnic Paris and region. However, the principal immigrant communities are North African (29.4%) and from Sub-Saharan Africa (18.2%); South-East Asian immigrants are largely Chinese, Vietnamese and Cambodian (14.2%), not Indonesian (Sagot Citation2013, 150). In that sense, the use of gamelan is more a symptom of cultural erasure (see Bakan Citation2017), unattached to its origins and denatured by its monophonic nature. The gamelan sounds float free, indiscriminately supporting actions and events by a range of characters.

What then is its function? It is unexpected but not strange, as it combines the familiar associated with Paris (and is an increasingly familiar feature as the seasons progress) with the unfamiliar sound for a crime series. But it also dislocates us from the Paris setting by its ‘exotic’ sounds, its monophonic qualities emphasising the dysfunctionally violent individualism of the main characters, whose team appears constantly to be falling apart within the broader landscape of social dysfunction of crime series more generally. The cyclical quality of the gamelan sounds, combined with their drone-like quality, structurally provides a grounding binding the ‘tessellated’ components of the series, as explained by Donnelly above. But it also constantly returns us to a curious tension between mystery and suspense on the one hand and a fatalistic sense of the inevitable on the other. And, finally, its vaguely exotic timbres function within the overall musical economy to situate the very Western piano.

I have considered the frequency of musical cues in Engrenages and the use of gamelan. The third specificity is the most interesting of these three: the transfer of a small group of piano themes as they detach from the characters we might have associated with them so as to reattach to others. Kalinak has identified this type of migrating motif in her study of the music of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (ANB/Showtime, 1990–1991):

Like the classical film, Twin Peaks recycles a limited number of distinctive themes, or leit-motifs [sic], but unlike the classical film, which uses these themes to foster identification between the spectator and specific characters, places, or even abstract ideas, Twin Peaks uses its leit-motifs to break conventional identificatory affect by setting up expectation which it then confounds. (Kalinak Citation1995, 87)

She suggests that a motif used with one character or activity and then reused with another destabilises our understanding of the characters’ emotions and motivations. In Twin Peaks, a motif that might have seemed to underscore a strong emotion resurfaces in parodic or anempathetic mode when attached to another character.

Migrating piano motifs in Engrenages do the opposite, however. They do not function like a musical version of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt to estrange or distance us from the characters and the narrative; on the contrary, they bind the characters together, counterpointing the dysfunctional individualism associated with monophonic gamelan cues. I have chosen to focus on piano themes specifically because Zidi commented that the series producers did not want the piano as an instrument (Zidi Citation2017). However, there are some 60 piano cues, either solo piano or with accompanying music, and they occur in all but one of the seasons. Unlike the gamelan cues, which are used indiscriminately where the characters are concerned, the piano themes, longer and more developed, are attached to specific characters, much like leitmotifs, and then reattached to others later in the series. As we shall see, a piano theme initially attached to Pierre in the first three seasons is also attached to Roban in Season 5. A piano theme attached to Roban in Season 4 is transferred to Laure in Season 6. A piano theme attached to Laure and her daughter Romy in Season 6 is transferred to Laure and Gilou in Seasons 7 and 8.

It is the implications of this kind of migration that interest me here, as they all have failures of relationships in common. On first hearing, they underscore and reinforce what we know to be happening in the narrative, and are therefore not used unexpectedly. As might be expected from slow and quiet mono-instrumental themes, they evoke emotive interiority, often in moments of the characters’ introspection, self-questioning and emotional fragility; they nearly always occur to accompany interior scenes, something that is typical of the use of the piano in films and series. Zidi has commented that he always returns to the piano as an instrument of choice when human emotions are to the fore, and that it contrasts with what he calls the ‘everyday madness’ of the series as a kind of call to order, a re-establishment of human priorities.Footnote13 However, their common underlying proposition that relationships are doomed unexpectedly pulls the focus of the series towards dysfunctional failure, throwing into question the romantic closure of Season 8.

The first set of piano themes most likely to ‘elicit notice’ is associated with the prosecutor Pierre, for two reasons. First, these themes most often reprise the opening motif of the title music, and second, they are frequently heard: five in Season 1, three in Season 2 and one in Season 3. We hear the first one when Pierre talks to his close friend Benoît (S01, E06, 00:02:04), then a different piano theme when he begins a series of romantic entanglements with Karine the journalist (S02, E04, 00:21:34). We return to the first piano theme emanating from the title sequence when Pierre and Laure begin their romance in the same episode (00:51:40).Footnote14 Then finally we hear the first piano theme again, although played on a gamelan gong, when he begins a romantic relationship with Joséphine (S03, E03, 00:13:08).

These relationships are all failures. Pierre is increasingly disappointed by Benoît’s questionable morality and then disappointed by the relationships he attempts with Karine, Laure and Joséphine; they do not develop as he would wish, not least because he still loves his wife. His wife also disappoints him by her active support for her father’s criminal activities. Pierre’s attempted relationships are all failures because he is unwilling to accept compromises in his sense of what is right and wrong, particularly with Joséphine, who tries to recruit him into working with her in shady contracts. Pierre’s melancholic piano themes therefore consistently carry connotations of failure and disappointment.

Judge Roban has two piano themes associated with him in Season 3. They are different from Pierre’s piano themes, as they are not based on the title sequence motifs. However, like those associated with Pierre, they also connote failures in his relationships, in this case with Arnaud, his intern, and Arnaud’s mother, Isabelle, with whom he has had a relationship in the past and with whom he attempts to reignite that relationship. We first hear Roban’s piano theme when he meets his new intern Arnaud and realises the connection with Isabelle (S03, E03, 00:08:47), and then later in the same season when Arnaud commits suicide as a result of Roban’s inflexible attitude to what is right and wrong, putting an abrupt end to his romance with Isabelle (S03, E12, 00:38:31).

Pierre and Roban appear together in the last iteration of Pierre’s piano theme in Season 5, when they look at each other across a crowded bar (see ), the camera lingering on their hesitant smiles at each other (Episode 6, 00:43:40) as we hear an extended version of Pierre’s piano theme. Pierre’s piano theme has migrated and attached to Roban, thus underscoring the failure of both men to maintain personal relationships that matter to them as a result of their commitments to their professional roles as upholders of the law.

Roban’s piano motif from Season 3 migrates to Laure at the end of Season 6 as Laure struggles to accept motherhood (Episode 12, 00:59:44), and, like the piano themes associated with Pierre and Roban, it too is associated with failure. We hear it as she runs away from the hospital where her daughter Romy is in the premature unit, as she feels that she cannot fulfil her role as mother. The piano themes in the first five seasons therefore have migrated from Pierre to Roban to Laure, and both their association with emotive interiority and their melancholic melodies reinforce the sense that all of these characters have failed in their relationships. This sense of failure is accentuated by the piano themes in Seasons 6 to 8, all of which are attached to Laure, and which, as I shall discuss in the next section, demonstrate both the yearning for escape as well as the inevitability of failure in their descending motifs.

Laure’s first major piano theme is associated with her daughter Romy (). We hear it on a number of occasions in Season 6, all connected with her daughter: when she watches Romy in the premature unit in Episode 1 (00:02:20), when she pumps breast milk in the same episode (00:49:18), when she holds Romy skin to skin to encourage her breastmilk at the end of Episode 2 (00:54:08) and when she watches Romy in her incubator in Episode 3 (00:17:09) after Brémont, the father, comments that it is good that she spends time with Romy. After the migration of Roban’s piano theme to her in Episode 12, however, and as if infected by the failure of Roban’s relationship with Isabelle following her son’s suicide, the occasions we hear the Romy piano theme are all associated with a sense of Laure’s failure as a mother. In Season 7 Episode 1 we hear it as Laure stares dejectedly at Romy’s empty cot because Brémont is looking after her (00:33:20), then in the same episode as an anguished Laure watches Brémont take Romy because she is busy (00:53:43).

Midway through the season, the Laure-Romy theme, which is heard seven times through Episodes 4 to 12, migrates to Gilou, accompanying moments when we see Laure and Gilou become close as they work together and eventually become lovers, during which time Romy is rarely seen. There are two significant exceptions, first in Season 8 Episode 1 when Brémont collects Romy and Laure is left alone in her flat, with a slow descending piano motif (00:36:00), and then later in the final episode of the season when she watches Romy playing with Brémont in the park, a scene that I will return to.

Laure’s second major piano theme is introduced in the next season and is associated with Gilou, as the two of them interrogate a suspect and he shows a caring attitude towards Laure (S07, E02, 00:41:07; ). We subsequently hear it eight times, in each case when she and Gilou are together, the narratively critical occurrence being when they make love in Season 7 Episode 9 (00:30:39).

Laure’s two major piano themes criss-cross throughout the latter half of Season 7 and the whole of Season 8. All episodes from Episode 4 onwards have an iteration of one of these two themes, and they nearly always occur when Laure and Gilou are together (). The piano themes constitute what I have called crystal-songs, musical moments that are narratively critical, fusing past, present and future (Powrie Citation2017). They crystallise turning points in the narrative. They do not illustrate or echo what we see; rather, they articulate a privileged musical moment of intense affect, standing out from other cues and themes by a combination of intensity and critical insistence. Although generally such moments are literally songs, occurring once, crystal-songs can be repeated songs and also music without lyrics, as I have argued in a discussion of the repeated piano piece ‘Mia and Sebastian’s Theme’ in Damian Chazelle’s film La La Land (2016; see Powrie Citation2023).

Table 4. Laure’s two major piano themes in Seasons 7 and 8.

The migration of the Laure-Romy theme to her relationship with Gilou is surprising, particularly given the sheer number of instances when a theme we previously associated with her daughter has now been attached to her relationship with Gilou. The piano theme we had become used to associating with Romy and Laure’s conflicting feelings about her daughter’s care over seven episodes is now exclusively cued to her relationship with Gilou. The almost total absence of scenes with her daughter pushes us to conclude that her daughter, and Laure’s role as a mother, matter much less to her than her relationship with Gilou. This is borne out by one of the two scenes in which we do see Romy.

At the end of Season 7, Laure walks happily towards Brémont and Romy playing in the park to the accompaniment, not of the Laure-Romy theme as we might have expected, but of the Laure-Gilou theme, emphasising her acceptance of Brémont as the primary carer (E12, 00:57:46; ). And at the end of the whole series, when we see Laure and Gilou walking in the crowd as they discuss their resignations, in other words when the focus is resolutely on the two of them as a couple, it is the Laure-Romy theme that we hear (S08, E10, 01:04:07; ). We might have argued that the migration of the Laure-Romy theme to a multitude of scenes with Laure and Gilou simply expresses Laure’s conflicted emotions towards Romy (as mother) and Gilou (as lover). The music underlines what we see: that Gilou is more important than Romy. Gilou has swallowed up affects associated with Romy, the contrast being obvious visually, as the green space of the park associated with family and motherhood () gives way to the anonymity of lovers in a city street ().

Does the music we hear make any difference to what we see in these two scenes? Both of them suggest visually Laure’s abdication of her role as a mother. It could be argued that we do not need the music to interpret the narrative in this way. But this view does not consider the shape of the music and its affective resonances, in other words, something beyond the frequency of musical cues and themes, and the instruments used to produce them, which was the focus of the first two parts of this article.

The shape of the musical themes: from utopian feeling to dystopian closure

Although we need to consider something other than the instruments used, nonetheless it is with them that we should start. This is because the cues are very different from the piano themes. Whether the cues are played on gamelan instruments or other instruments, they are close to gamelan music in their insistence on rhythmical motifs with minimal scale range. An example of this is a frequently occurring staccato trumpet motif (E5-E5-C5-C5-B5/F#5-F#5-C5-C5-B5), such as when Roban comments cynically on Elena’s profile as a prostitute in Season 1 Episode 1 (00:12:21), or when Joséphine is offered a job with a debarred solicitor (S01, E01, 00:34:05), or finally when Laure returns to the police station after a drubbing from Roban (S02, E06, 00:35:48). A second often-repeated motif is a tolling gamelan gong. Like the trumpet motif, it is associated with a broad range of characters. It can be a single repeated note, as when Pierre dies at the end of Season 5 Episode 6 (the note E4; 00:53:38), or when Gilou and Laure operate a surveillance on the corrupt cop Jolers at the end of Season 6 Episode 7 (F4; 00:43:07), or a two-note motif such as when Samy goes shopping in Season 2 Episode 8 (D4-E4; 00:15:58), or finally a more complex motif such as when Joséphine is accused of murdering her rapist Vern in Season 6 Episode 11 (A4-A4-A#4-A#4-A4/B4-B4-C5-C5-B4; 00:23:01).

The trumpet and gong motifs are both tightly compressed, relying generally on repeated one-note shifts (A4-A#4, B-C, D-E). As William Thompson writes, referring to David Huron’s work (Citation2001), ‘melodies that consist of a sequence of small intervals sound coherent and cohesive’ (Thompson Citation2013, 116). The frequent appeal to small intervals, in conjunction with the consistent use of gamelan, as I pointed out above, gives a sense of grounding and consistency to the series world. This contrasts markedly with the piano themes, which all range more broadly across a wide span of notes, generally more than an octave: Pierre’s piano theme, which reprises the title music, ranges from F#5-G6 (), Romy’s theme from C3-C5 () and Gilou’s from D4-G6 (). The piano themes feel as though they leap upwards only to fall sharply downwards. As Thompson says, such ‘melodic “leaps” are perceived as points of melodic accent’ (Citation2013, 116; citing Jones Citation1987) and are as a result more noticeable when contrasted with the small intervals of most of the series’s musical cues.

The piano themes are not just more noticeable by their tonality (piano rather than the more ubiquitous gamelan) but are also more significant by their form (melodic leaps, which contrast with the small intervals of most of the cues). Moreover, the melodic leaps recall the same octave+ melodic leaps in the title music (F#5-G6). Formally, this gives a sense of closure: whatever quandaries the characters might have found themselves in, the melodic leaps of the piano themes suggest the possibility of escape, the window through which the characters can escape from the imprisoning engrenages of their situations. This is best exemplified by the already mentioned final sequence of the series when Laure says to Gilou over the piano theme that she is quitting her job to avoid putting herself in danger.

The marked difference between closed-interval cues and the melodic leaps of the piano themes therefore encourages us first to hear the feelings of the characters (‘I’m desperate for a way out of here’), and second to understand the resolution of their narrative arcs as positive (‘… and as long as I can leave, all will be good’). The themes manage this by leaping up the scale. However, the themes, once they have leaped, all descend melancholically. Their cadences, the musical phrases working towards closure, as the Latin origin of the word ‘cadence’ suggests, all fall. This suggests a less positive reading of the series’s closure on the final coming together of Laure and Gilou. The fact that all of the musical themes end by falling, and that the piano themes heard in the first few seasons are all associated with disappointment and failure (of Pierre and Roban), arguably infects the later piano themes, not least because the Laure-Romy theme is also associated with Laure’s failure to be the mother she aspires to be. The closure of the series on what appears to be a positive note as Laure and Gilou manage to do what the whole series has been preparing us for, the formation of a couple, looks in this light considerably less positive. Without the music, we might have seen this closure as completely positive: Laure knows that Brémont is a good father and that Romy does not need her full-time, so that she can seek happiness with Gilou.

The migrating piano themes tell a different story, however. They connote disappointment and death. They are principally associated with Pierre and Roban, both of whom are disappointed in love and both of whom have to face death: Pierre when he is shot, Roban when he has to face the consequences of his actions after Arnaud’s suicide. Joséphine also has short descending piano phrases attached to her, and although they are less developed than the Pierre and Roban themes, they too connote the failure of relationships for her. We hear these short falling phrases frequently in Season 8, whether it is her failed heterosexual relationship with the lawyer Edelman (E01, 00:43:51), the failed lesbian relationship with Lola (E07, 00:18:37) – she says dejectedly to Edelman when Lola leaves, ‘why do we desire everything that escapes us?’Footnote15 – or, finally, her failed maternal relationship with the murdered youth Souleyman (E08, 00:18:05).

The final sequence in which Laure and Gilou meet in the Place de la République as ordinary citizens, accompanied by the Laure-Romy piano theme, but crucially without Romy and without jobs, is therefore problematic if we attend to the implications of the music. The piano theme that accompanies this closure, if we accept the music at face value, suggests a utopian heterosexual resolution of the many conflicts that the series has explored. But its plangent and haunting quality gives the game away: what feels like a satisfactory utopian closure is shot through with dystopian undercurrents of failure and loss. It is difficult to avoid the generic and gendered implications of what we are seeing: that to be happy, a woman must overcome her role as mother and leader and bury herself as anonymous lover in the crowd. If we hear the music, we recognise that escape from the engrenages comes at a cost.

Conclusion

The work on film music since the 1980s is extensive. Given the sparse amount of work on music in television series, the aim of this article, apart from exploring the music of Engrenages which has not yet been done, has been twofold: to demonstrate that music plays just as important a role in shaping our experience of a television series, and that, correlatively, its role extends beyond simply confirming what we see on screen. The music in television series, even more than the music of films, can remain ‘unheard’ by spectators. Its small musical blocks, frequently repeated, tend to function mechanically to underscore what is happening on screen, and even more mechanically, to link scenes together so that what we see appears to be less fragmented, arguably acting as a kind of uninteresting sonic glue.

The exploration of the music in Engrenages, however, shows just how much music matters. The juxtaposition of relatively unusual gamelan instrumentation with more usual melodic piano themes draws attention to the musical textures of the series and urges us to think through that juxtaposition and its potential meanings. The monophonic gamelan cues are stripped of the socially cohesive connotations of normally polyphonic gamelan music; they continuously return us to the dystopian nature of a socially divided France, while at the same time underlining the inevitability of engrenages, the interdependence and inseparability of the different social groups, constantly brought together as they struggle to determine – given that this is a crime series – their relationship to the law.

A careful analysis of the piano themes in the series shows us that what appear to be moments of potentially utopian emotion as respite from the dystopia of social fragmentation in reality construct a parallel narrative for the main characters, intensifying the dystopian ground of the musical cues. The piano themes migrate between the characters, catching them in their swirling melodic cogs, emphasising the loss and disappointment that they share. Attending to the implications of the musical themes leads us, then, to a considerably less comforting closure for this series. Over the series as a whole, the piano themes construct a shift and cluster effect; we are forced to recognise that Laure’s closing rejection of maternal and professional roles does not necessarily mean that she escapes the engrenages.

Television series

Braquo, 2009–2016. 4 seasons. Olivier Marchal. Canal+. France.

Bron/Broen, 2011–2018. 4 seasons. Hans Rosenfeldt. Sveriges Television/Danmarks Radio. Sweden/Denmark.

Le Bureau des légendes, 2015–2020. 6 seasons. Éric Rochant. Canal+. France.

Commissaire Moulin, 1976–2006. 8 seasons. Paul Andréota/Claude Boissol. TF1. France.

Engrenages, 2005–2020. 8 seasons. Alexandra Clert/Guy-Patrick Sainderichin. Canal+. France.

Line of Duty, 2012–2021. 6 seasons. Jed Mercurio. BBC. UK.

Mafiosa, 2006–2014. 5 seasons. Hugues Pagan. Canal+. France.

Maigret, 1991–2005. 14 seasons. Claire Lemouchoux. Antenne 2/France 2. France.

Navarro, 1989–2007. 16 seasons. Tito Topin/Pierre Grimblat. TF1. France.

Les Témoins, 2015–2017. 2 seasons. Hervé Hadmar/Marc Herpoux. France 2. France.

Twin Peaks, 1990–1991, 2017. 3 seasons. Mark Frost/David Lynch. ABC/Showtime. USA.

Filmography

L’Amour aller-retour, 2009. Eric Civanyan, France.

Anna and the King of Siam, 1946. John Cromwell, USA.

Avatar, 2009. James Cameron, USA.

Clara, une passion française, 2009. Sébastien Grall, France.

Cleopatra, 1963. Joseph L. Mankiewicz, USA.

La La Land, 2016. Damian Chazelle, USA/Hong Kong.

The Sand Pebbles, 1966. Robert Wise, USA.

The Time Traveller’s Wife, 2009. Robert Schwentke, USA.

Vertigo, 1958. Alfred Hitchcock, USA.

Music

Debussy, Claude. 1890. Fantaisie.

Debussy, Claude. 1903. Pagodes.

Messiaen, Olivier. 1949. Turangalîla-Symphonie.

Messiaen, Olivier. 1953. Réveil des oiseaux.

Messiaen, Olivier. 1956. Oiseaux exotiques.

Messiaen, Olivier. 1974. Des canyons aux étoiles.

Messiaen, Olivier. 1986. Un vitrail et des oiseaux.

Poulenc, Francis. 1932. Concerto pour deux pianos.

Ravel, Maurice. 1910.‘Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes’. In Ma mère l’Oye.

Reich, Steve. 1973. Music for Pieces of Wood.

Satie, Erik. 1893. Gnossiennes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Phil Powrie

Phil Powrie is Emeritus Professor of Cinema Studies at the University of Surrey. He was the Chief General Editor of French Screen Studies (formerly Studies in French Cinema, 2010–2020) and was the Chair of the British Association of Film Television and Screen Studies, 2014–2017. He has published extensively on French cinema, including French Cinema in the 1980s: Nostalgia and the Crisis of Masculinity (Clarendon, 1997), Jean-Jacques Beineix (Manchester UP, 2001), Pierre Batcheff and Stardom in 1920s French Cinema (Edinburgh UP, 2009), Music in Contemporary French Cinema: The Crystal-Song (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) and (co-authored with Marie Cadalanu) The French Film Musical (Bloomsbury, 2020). His most recent book is a collection edited with Anna Windisch and Claus Tieber, Meaningful Melodies: When Music Takes Over in Film (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

Notes

1. IMDb and AlloCiné data collected until 30 March 2022.

2. Coulthard (Citation2018) and Broad (Citation2020) are extensive and welcome explorations of music more generally in series, the former focused specifically on the female detective in crime series. See also Russo and Steenberg (Citation2016) and Coulthard et al. (Citation2018) for more general work on television crime series. There is limited work on Engrenages; see McCabe (Citation2012) and McHugh (Citation2018).

3. The most frequently referenced work is Stanitzek and Aplevich (Citation2009). See also Janin-Foucher (Citation1989), de Mourgues (Citation1994), Moinereau (Citation1995), Tylski (Citation2008), Cecchi (Citation2014), Klecker (Citation2015), Racioppi and Tremonte (Citation2014), Post (Citation2015), Zons (Citation2015), Pascal (Citation2017), Allison (Citation2020).

4. See Kirkham and Bass (Citation2011) and Horak (Citation2014). For an analysis of Bass’s famous title sequence for Hitchcock’s Vertigo, see Kirkham (Citation2009).

5. On title sequences, see Gripsrud (Citation1995), Kutnowski (Citation2008), Davison (Citation2013), Bednarek (Citation2013, Citation2014), Fahlenbrach and Flueckiger (Citation2014).

6. The titles were designed by Sylvain Lamour, film editor and specialist in visual effects. He is responsible for the main titles of several television films, such as L’Amour aller-retour/Canadian Love (Eric Civanyan, 2009, starring Audrey Fleurot, the lawyer Joséphine Karlsson in Engrenages) and Clara, une passion française (Sébastien Grall, 2009), which included in its cast Louis-Do de Lencquesaing, the lawyer Éric Edelman in Engrenages.

7. In Bednarek’s statistical study of 50 television series, only 12 ‘play primarily with the show’s title, animating it in various ways’ (Citation2014, 134).

8. Personal communication with Stéphane Zidi, 26 February 2022.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. ‘Une mise à distance de l’ego et une expérience forte du corps collectif, jusqu’à donner à sentir quelque chose du goût ineffable de l’indifférencié.’

12. Personal communication with Stéphane Zidi, 26 February 2022.

13. Ibid.

14. Time codes indicate the start of the cue.

15. ‘Pourquoi est-ce qu’on désire tout ce qui nous échappe ?’

References

- Allison, D. 2020. “You Oughta Be in Pictures: Cartoons and Caricatures in Opening Title Sequences.” Film International 18 (1): 82–88.

- Bakan, M. J. 2017. “Balinese Music, an Italian Film, and an Ethnomusicological Approach to Screen Music and Sound.” In The Routledge Companion to Screen Music and Sound, edited by Miguel Mera, Ron Sadoff, and Ben Winters, 61–71. London: Routledge.

- Basset, C. 2010. “L’univers du gamelan: opposition théorique et unicité fondamentale.” Archipel 79: 125–194.

- Bednarek, M. 2014. “‘And They All Look Just the Same’? A Quantitative Survey of Television Title Sequences.” Visual Communication 13 (2): 125–145.

- Bednarek, M. 2013. “The Television Title Sequence: A Visual Analysis of Flight of the Conchords.” In Critical Multimodal Studies of Popular Discourse, edited by Emilia Djonov and Sumin Zhao, 36–54. London: Routledge.

- Boucher, G. 2015. “From the Archives: James Horner on Creating a ‘Sound World’.” Los Angeles Times, June 23. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/herocomplex/la-et-hc-james-horner-searches-for-the-sound-of-pandora-story.html

- Bribitzer-Stull, M. 2015. Understanding the Leitmotif: From Wagner to Hollywood Film Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Broad, L. 2020. “Game of Thrones: Music in Complex TV.” Music and the Moving Image 13 (1): 21–42.

- Canal+. 2020. “De la musique à l’argot policier, Engrenages, c’est aussi une histoire de style.” https://www.canalplus.com/articles/series/de-la-musique-a-l-argot-policier-engrenages-c-est-aussi-une-histoire-de-style. Accessed 2022.

- Cecchi, A. 2014. “Creative Titles: Audiovisual Experimentation and Self-Reflexivity in Italian Industrial Films of the Economic Miracle and After.” Music, Sound and the Moving Image 8 (2): 179–194.

- Coulthard, L. 2018. “The Listening Detective: Thinking Music, Gender, and Transnational Crime’s Affective Turn.” Television & New Media 19 (6): 553–568.

- Coulthard, L., T. Horeck, B. Klinger, K. McHugh, eds. 2018. “Broken Bodies/Inquiring Minds: Women in Contemporary Transnational TV Crime Drama.” Special number of Television & New Media 19 (6): 507–514.

- Courtney, D. 2022. “Drones in Indian Music.” https://chandrakantha.com/music-and-dance/i-class-music/drones/

- ‘Cremebluray’. 2015. “10/10 and I Do Not Say This Lightly. Best Police Show Ever. The Gold Standard Itself.” Internet Movie Database, December 24. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0477507/reviews/?ref=ttqlurv

- Davison, A. 2013. “The Show Starts Here: Viewers’ Interactions with Recent Television Serials’ Main Title Sequences.” SoundEffects 3 (1–2): 7–22.

- de Mourgues, N. 1994. Le générique du film. Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck.

- Donnelly, K. 2005. The Spectre of Sound: Music in Film and Television. London: BFI.

- Fahlenbrach, K., and B. Flueckiger. 2014. “Immersive Entryways into Televisual Worlds: Affective and Aesthetic Functions of Title Sequences in Quality Series.” Projections 8 (1): 83–104.

- Gorbman, C. 1987. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Gripsrud, J. 1995. The Dynasty Years: Hollywood, Television and Critical Media Studies. London: Routledge.

- Horak, J.-C. 2014. Saul Bass: Anatomy of Film Design. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Huron, D. 2001. “Tone and Voice: A Derivation of the Rules of Voice Leading from Perceptual Principles.” Music Perception 19 (1): 1–64.

- Janin-Foucher, N. 1989. “Du générique au mot FIN. Le paratexte dans les œuvres de F. Truffaut et de J.-L. Godard (1958–1984).” PhD diss., Lyon 2.

- Jones, M. R. 1987. “Dynamic Pattern Structure in Music: Recent Theory and Research.” Perception & Psychophysics 41 (6): 621–634.

- Kalinak, K. 1995. “‘Disturbing the Guests with This Racket’: Music and Twin Peaks.” In Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to Twin Peaks, and David Livery, 82–92. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Kirkham, P. 2009. “Vertigo (Title Sequence), Alfred Hitchcock (1958).” Design and Culture 1 (2): 218–222.

- Kirkham, P., and J. Bass. 2011. Saul Bass: A Life in Film & Design. London: Laurence King.

- Klecker, C. 2015. “The Other Kind of Film Frames: A Research Report on Paratexts in Film.” Word & Image 31 (4): 402–413.

- Kutnowski, M. 2008. “Trope and Irony in the Simpsons’ Overture.” Popular Music and Society 31 (5): 599–616.

- ‘LeJoker’. 2021. “« Critique de la série. »” Allociné, May 19. https://www.allocine.fr/series/ficheserie-538/critiques/recentes/

- McCabe, J., ed. 2012. “Dossier: Exporting French Crime: The Engrenages/Spiral Dossier.” Critical Studies in Television 7 (2): 101–118.

- McHugh, K. 2018. “The Female Detective, Neurodiversity, and Felt Knowledge in Engrenages and Bron/Broen.” Television & New Media 19 (6): 535–552.

- Mittell, J. 2015. Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Storytelling. New York: New York University Press.

- Moinereau, L. 1995. Le générique de film. De la lettre à la figure. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Mueller, R. 1986. “Javanese Influence on Debussy's ‘Fantaisie’ and Beyond.” 19th-Century Music 10 (2): 157–186.

- Orledge, R. 1990. Satie the Composer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Orledge, R. 2000. “Evocations of Exoticism.” In The Cambridge Companion to Ravel, and Deborah Mawer, 27–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Parker, S. 2012. “Claude Debussy’s Gamelan.” College Music Symposium 52. https://symposium.music.org/index.php/52/item/22-claude-debussys-gamelan

- Pascal, M. 2017. “Prégénériques et génériques dans les adaptations cinématographiques québécoises.” Revue canadienne d’études cinématographiques 26 (2): 93–116.

- Post, J. 2015. “From Altered States to Altered Titles: A Close Analysis of the Title Sequence to Ken Russell’s Altered States (1981).” Journal of British Cinema and Television 12 (4): 556–571.

- Powrie, P. 2017. Music in Contemporary French Cinema: The Crystal-Song. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Powrie, P. 2023. “The Acoustic Wound: Reflections on the Crystal-Song in Five American Films.” In When Music Takes over in Film, edited by Anna Windisch, Claus Tieber, and Phil Powrie, 35–54. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Puspita, A. 2008. “The Influence of Balinese Gamelan on the Music of Olivier Messiaen.” Doctor of Musical Arts diss., University of Cincinnati.

- Racioppi, L., and C. Tremonte. 2014. “Geopolitics, Gender, and Genre: The Work of Pre-Title/Title Sequences in James Bond Films.” Journal of Film and Television 66 (2): 15–25.

- Reed, P. 1999. “Poulenc, Britten, Aldeburgh: A Chronicle.” In Francis Poulenc: Music, Art and Literature, edited by Sidney Buckland and Myriam Chimènes, 348–362. London: Routledge.

- Russo, P., L. Steenberg, eds. 2016. “The Crime Drama on Transnational Television.” Special number of New Review of Film and Television Studies 14 (3): 299–303.

- Sagot, M. 2013. “Les immigrés et leurs familles en Îles de France.” In Atlas des Franciliens, edited by François Dugeny, 147–150. Paris: Institut d’aménagement et d’urbanisme, Île de France.

- Smith, S. C. 2002. A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stanitzek, G., and N. Aplevich. 2009. “Reading the Title Sequence (Vorspann, Générique).” Cinema Journal 48 (4): 44–58.

- Stilwell, R. J. 2011. “‘Bad Wolf’: Leitmotif in Doctor Who (2005).” In Music in Television: Channels of Listening, and James Deaville, 119–141. New York: Routledge.

- Tenzer, M. 2019. “Rethinking Reich.” In That’s All It Does: Steve Reich and Balinese Gamelan, edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn, 303–322. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thompson, W. F. 2013. “Intervals and Scales.” In The Psychology of Music, and Diana Deutsch, 107–140. Amsterdam: Academic Press.

- Tilley, L. 2020. “The Draw of Balinese Rhythm.” In: The Cambridge Companion to Rhythm, edited by Russell Hartenberger and Ryan McClelland, 261–282. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tylski, A. 2008. Le générique de cinéma. Histoire et fonctions d’un fragment hybride. Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Mirail.

- Wiley, C. 2011. “Theorizing Television Music as Serial Art: Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the Narratology of Thematic Score.” In Buffy, Ballads, and Bad Guys Who Sing: Music in the Worlds of Joss Whedon, and Kendra Preston Leonard, 36–68. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

- Zidi, S. 2017. “La musique de la série Engrenages expliquée par son compositeur.” Canal+ Médias Jack, October 20. https://jack.canalplus.com/articles/lire/stephane-zidi-linterview-compositeur-d-engrenages

- Zons, A. 2015. “Projecting the Title.” Word & Image 31 (4): 442–449.