ABSTRACT

Netflix’s globally oriented French products are commercially bound to negotiate between producing locally legible and internationally acceptable gender types. This article spotlights variations in representing the French romantic hero – traditionally a gallant séducteur – to a global audience hypersensitive to notions of toxic masculinity in two post-#MeToo Netflix Original French romantic comedy narratives: the series Plan cœur/The Hook-Up Plan (2018–2021) and the film Je ne suis pas un homme facile/I Am Not an Easy Man (Eléonore Pourriat, 2018). Noting that Netflix is now the key export channel for French romcoms, the article draws primarily on textual analysis, while also leveraging psychoanalytic and affective theories, to argue that the platform’s impetus to make French masculinity in particular more widely palatable, and (so) appeal to emergent popular feminism, has the potential to reconfigure parameters of legitimate gender norms, French and beyond.

During the 2010s, French romantic comedy consolidated an already healthy domestic performance established by the genre from the moment of its emergence in the late 1990s and especially throughout the 2000s. Meanwhile, however, the French genre’s earlier export success – epitomised and catalysed by the global blockbuster Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain/Amélie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001) – on the whole petered out (Harrod Citation2020, 102–103). This change correlates with a significant dip in the popularity of romcom as an internationally circulating theatrical genre since the accelerated rollout of digital streaming platforms in the early 2010s. Thus, not one of the 100 highest-grossing films of all time in the genre was made after 2012.Footnote1 While romcom had spread wings across the televisual sector earlier, notably through such influential and highly viewed female-centric HBO shows as Sex and the City (1998–2004) and later Girls (2012–2017), and although domestic productions continue to draw substantial returns at many home box offices, since the early to mid-2010s the transnational genre has migrated online to a significant degree – both as a feature-length narrative form and through adaptation to the serial format. This may be something of a recent tendency for other international audiovisual genres as well (narratives focusing on teens and young people stand out); however, Netflix’s 2018 ‘Summer of Love’ season marks the notable shift in romcom’s positioning, by making the genre central to its offering. More recently, a list ranking 100 internationally produced Netflix Original romances was updated in February 2023.Footnote2 Over the same period, stand-out romantic comedy series available on the platform include Master of None (Netflix, 2015–2021), created by the (since #MeToo) infamous US comedian Aziz Ansari and heralding the platform’s turn towards popular ‘quality’ programming, notably in comedy (Jenner Citation2018, 24), or from outside the USA examples such as the Norwegian Home for Christmas (Netflix, 2019–2020), the British Lovesick (Channel 4/Netflix, 2014–2018) or the LGBTQ+-inflected Korean Joahamyeon Ullineun/Love Alarm (Netflix, 2019). Also deserving of a mention in an analysis of postnational Frenchness is the French-set (though US-originated) Emily in Paris (Netflix, 2020–), a culture-clash comedy with romantic elements widely discussed and often decried on social media and in the mainstream press for its caricatured, touristic, antiseptic and (especially in Season 1) whitewashed vision of the French capital. Likewise, at the time of writing, contemporary French romantic comedy exists in the eyes of the rest of the world almost exclusively through streaming platforms.

Despite conforming to global trends for other non-anglophone romcoms, the bifurcation between French films of the genre designed for export and others – though it was first identified as emergent just before the streaming era in relation to earlier French (co-)produced but anglophone (or silent) films such as The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2008) or Julie Delpy’s duo 2 Days in Paris (2007) and 2 Days in New York (2015) (Harrod Citation2015, 212–213) – is now strikingly pronounced. Enabled by the delocalisation of internet-based viewing, the split can nevertheless also be ascribed to the renewed conservatism if not populism intermittently traded in by many French romcoms outside those on streaming platforms (for instance, La Famille Bélier/The Bélier Family [Éric Lartigau, 2014] or Chic! [Jérôme Cornuau, 2015]), which may be off-putting to the relatively elite global audience for foreign-language fare (Harrod Citation2020). This observation highlights the reactionary nature of certain pockets of French culture, notably those connected to gender identities. It also points to the way that Netflix French romcoms – which here stand as emblematic of those produced by comparable streaming platforms, such as Amazon Prime, that have begun to adopt Netflix’s approach – represent but one carefully calibrated strand within French depictions of the genders, as well as within Gallic coupledom and courting practices more generally.Footnote3

In fact, it should be noted that an entire genre cannot be reduced to the binary of retreatist nationalism versus aspiration to mass international exposure either, since genres denote not fixed categories but ever-shifting horizons of expectation. Even at the time of writing, the presence of a film such as Mia Hanson-Løve’s independently produced, festival-decorated Un beau matin/One Fine Morning (2022) on international cinema screens speaks to the fact that French romcom (still) haunts many corners of film production globally and accordingly refuses to be pinned down too firmly in character (cf. Deleyto Citation2009). Despite a second plotline focused on the challenging topic of caring for a cognitively impaired elderly parent, this modestly exported auteur film about a couple uniting despite the man being married engages many of the genre’s classic modalities via its plot focused on reconciliation through romance against numerous odds, and it is not transparently concerned with any issues of either national or more cosmopolitan identity as such at the diegetic level. However, it is in products targeting a large mainstream audience that this article is interested. Specifically, it considers the particularities of how a national audiovisual genre, the French romcom, is reimagined when it is produced by Netflix (and potentially other streaming platforms following suit) with a transnational audience in mind: when it is postnational, in the terms laid out by the Introduction to this Special Issue.Footnote4 Specifically, it spotlights variations in representing the French romantic hero – traditionally a gallant séducteur descended from the medieval romance (ballad) – to a global audience hypersensitive to notions of toxic masculinity, in two post-#MeToo Netflix Original French romcom narratives: the series Plan cœur/The Hook-Up Plan (2018–2022) and the film Je ne suis pas un homme facile/I Am Not an Easy Man (Eléonore Pourriat, 2018).Footnote5 To this end, it first adumbrates recent developments in presenting the genders in romantic comedy, and their scholarly interpretation, before homing in on the French context and case studies. I draw on psychoanalytic and affective theories to argue that, while commercially driven, the platform’s impetus to make French masculinity in particular more widely palatable, and (so) appeal to emergent popular feminism, has the potential to reconfigure parameters of legitimate gender norms (French and beyond).

‘Head trauma and time-loops’Footnote6

The rhetoric of crisis in discussions of romance has become increasingly widespread in the last decade or so, in both academic and more mainstream discourse (Harrod, Leonard, and Negra Citation2021, 1–12). Likewise, romantic comedy is now routinely labelled ‘post-epitaph’ (Cobb and Negra Citation2017) or ‘post-romantic’ (San Filippo Citation2021). As Tamar Jeffers McDonald (Citation2019) has noted, the genre has a history of provoking such morbid pronouncements, among which the most infamous is perhaps Henderson’s (Citation1978) erroneous prediction of its certain disappearance in the wake of the sexual revolution. Jeffers McDonald pinpoints the relevance of Henderson’s rationalisation that ‘there can be no romantic comedy without strong heroes’ to the contemporary ‘crisis’ context. That is, at its heart, romantic discourse relies on gender differentiation to hook viewers into its genre-work of bringing together characters whose allure to one another lies in their mutual otherness. This sits ill with a contemporary culture that not only shuns the mystery associated with romance in favour of relational transparency and open communication but also condemns, if not execrates, such traditionally ‘masculine’ values as mastery and rampant sexuality – especially since #MeToo.

Allusion to this movement provides an obvious bridge to considering how such issues may be multiplied in the Gallic context, in view of the attitudes towards courting harboured by some French women that the campaign uncovered. Thus, a letter published in Le Monde on 9 January 2018 in which various well-known and other women expressed their opposition to #MeToo, on the grounds that men’s ability to approach or ‘pester’ [importuner] women was essential to sexual freedom (Alévêque Citation2018), was quickly caricatured by a largely scornful global (Anglo-led) mediasphere ‘the French response to #MeToo’. Such a reductive label ignored the fact that most of this letter’s signatories – like its unfortunate figurehead, the star actor Catherine Deneuve (and to a lesser extent internationally the writer Catherine Millet) – were middle aged or older. The caricature ignored, too, the many other French movements singing from the same hymn sheet as #MeToo – among them the French equivalent hashtag #BalanceTonPorc [squeal on your pig] – that gained visibility in the following weeks. Considering such details suggests that a generational divide within France intersects with national differences on this issue, even as this divide itself speaks to the accelerated influence of Anglo-American cultures there in recent decades. Indeed, the changing contours of desirable French masculinity accompanying the translocalisation of the ‘intimate public sphere’ (Berlant Citation2008, vii–viii) had already been graphically demonstrated by the sensational 2011 scandal that saw French Socialist Party candidate and head of the International Monetary Fund Dominique Strauss-Kahn ignominiously arrested in New York. Strauss-Kahn was shamed by the global media following claims of sexual assault against hotel worker Nafissatou Diallo and the ensuing accounts of his libertine customs (further accusations of assault, lurid tales of sex parties and orgies) that poured out. More recently, the international opprobrium towards a form of masculinity defined by unbridled male sexuality and games of seduction that by their nature rely on negotiated power imbalances has only multiplied with the much-mediatised publication of sensational accounts denouncing public figures as socially sanctioned paedophiles (the politician Olivier Duhamel and the writer Gabriel Matzneff) and/or rapists. Figures from the French film industry have been prominent in varying ways across these categories, among them the actors Richard Berry and Gérard Depardieu, the state film financing body president Dominique Boutonnat and the directors Christophe Ruggia and Roman Polanski.

How can romantic comedy mediate a version of masculine seduction whose identity is under negotiation, if not in open disarray? In particular, how can the genre sell a French masculinity coruscated and vituperated by the international media in international markets, while remaining legible, or reconcilable with lived gender realities, domestically – in other words, maintaining appeal for the primary market while also being ‘transnational from the outset’ (Jenner Citation2018, 212; original emphasis)? Mareike Jenner (189) adopts Joana Breidenbach and Ina Zukrigl’s concept of a ‘dance of cultures’, wherein sometimes ‘otherness’ is embraced or tamed and at other moments resisted, to describe Netflix texts. While it is precisely this that is meant by my claim that the streaming platform’s products are postnational in their positioning vis-à-vis audiences – they are constructed to identify themselves as and with their national culture but in selective ways that also resonate elsewhere – the dance promises to be particularly elaborate when performed by the French romcom.

Jeffers McDonald identifies one response offered by Netflix and other romcoms to the contemporary conundrum that chimes strongly with the French-produced subgroup: a turn to tropes designed to palliate masculine otherness and neutralise any threatening qualities. On the one hand, she notes the frequency of romcoms dealing with teenagers, whose lack of life experience allows the plot to bypass cynicism, while the male characters’ youth offsets the masterful aspects of any romantic gallantry. French cinema does not share Hollywood’s long tradition of ‘teenpics’, for reasons historically ascribable to its older cinemagoing public, and this trend has not caught on substantially in French romcoms even on Netflix. However, the self-explanatory plot of the film MILF (Axelle Laffont, 2018) does strategically deploy youthful male protagonists while exploiting the French tradition for pairing them with sexually experienced older women, courting feminist credentials in the process.Footnote7 Of more relevance to the French context, however, is Jeffers McDonald’s observation that plots featuring fantasy or time-travel and other kinds of mentally altered states (including ‘disturbed’ thoughts and behaviours) also recur in films from What Men Want (Adam Shankman, 2019) to I Feel Pretty (Abby Kohn and Marc Silverstein, 2018) and The Kissing Booth (Vince Marcello, 2018, a Netflix Original production) as a means by which to bracket apart and thus create fresh space for highly differentiated gender roles. These are repeat traits of French romcoms on Netflix. For example, one of the earliest examples to feature on the platform, Blockbuster (2018), tempers its celebration of a couple directly resulting from the male protagonist Jérémy’s (Syrus Shahidi) pavement harassment of women through the distancing use of both embedded home movie footage and especially retro fantastic elements drawn from superhero and comic book culture. While Netflix’s contract to license Blockbuster worldwide was not renewed on expiry in 2021, when it disappeared from the platform, a comparable film available through it at the time of writing is Un peu, beaucoup, aveuglément/Blind Date (2015): the story of a ‘mansplaining’ agoraphobic inventor (Clovis Cornillac) who falls for his next-door neighbour via conversations across their party wall. In this case, the protagonist’s unwillingness to leave his apartment, where he surrounds himself with retro music and analogue technologies, aligns him more figuratively with a time-space removed from contemporary realities.Footnote8

Not unlike the populist romcoms dotting the contemporary landscape elsewhere, these non-Netflix-produced (but Netflix-distributed) films smack of a backlash against the cultural injunction to repudiate conventions widely seen as outmoded in the international community – in this case those enshrining, respectively, male libertinage and patriarchal control. However, the post-#MeToo Netflix Original television series and film that provide the focus of this article offer significantly more complex examples of the arm’s-length approach to constructing French romantic masculinity. The comparison of these that follows is informed by a conception of ‘legitimate’ identities as constructed across different cultural texts, including spanning the film–television divide, as streaming platforms’ undiscriminating approach to format and content diversity in any case increasingly invites.

Postmodernity and anachronism in Plan cœur

Comprising three seasons (eight episodes in Season 1 and six in 2 and 3) of between 22 and 32 minutes, plus a lockdown special of 49 minutes, Plan cœur was the second Netflix Original French series to be broadcast after the critically poorly received Depardieu vehicle Marseille (two seasons between 2016 and 2018). Its French title, a reversal of the French slang expression for a purely sexual ‘hookup’ [plan cul] instead foregrounding matters of the heart [cœur], refers to a high concept that, we shall see, offers a framework for exploring anxieties about masculinity worked through principally via its male lead Jules (Mark Ruchmann). Entirely lost in the English translation, this wordplay heralds a narrative focus on transactional sex that turns into a love affair. Because this plot device runs its course during Season 1, my analysis is initially and most substantially focused accordingly.

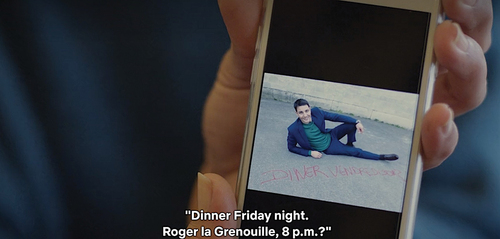

Throughout Season 1, handsome Jules plays to stereotypes of French galanterie and seduction but with a modern nuance. He is introduced to viewers and to the female lead Elsa (Zita Hanrot) in Episode 1 when the latter, drunk, mislays her phone at a party and Jules returns it. Arranging to meet Elsa to hand over the device in the romantic tourist setting of Place de l’Hôtel de Ville, where she works, Jules is immediately friendly, explaining that he couldn’t help but notice her the night before (this line comically undercut by the detail that she left vomiting out of the window of her shared Uber!), then proposing they have a coffee. Although Elsa declines, she later finds photos of Jules on her phone with a dinner invitation chalked on the pavement and wall beside him. Because her drunken behaviour is but one manifestation of difficulties she is having getting over an ex, Maxime (Guillaume Labbé), who dumped her, Elsa’s close female friends Milou (Joséphine Draï) and Charlotte (Sabrina Ouazani) encourage her to accept. The female protagonist is initially alarmed by Jules’s naked enthusiasm to sleep with her but succumbs by date three (S01, E03). Meanwhile, it has been revealed to viewers that Jules is a sex worker hired by Charlotte to help Elsa get over Maxime. While Charlotte envisaged sex helping Elsa regain confidence, instead – following a well-worn romcom script seen in films from Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall, 1990) to L’Arnacœur/Heartbreaker (Pascal Chaumeil, 2010), or the more melodramatic Cliente/A French Gigolo (Josiane Balasko, 2008) – the deception scenario morphs into reality when she and Jules find themselves physically drawn to one another and he starts to court her ‘for real’, despite the complexities of having to maintain a false persona (his real name is Julio Saldenha and he is not, of course, a teacher, as he has been claiming). Only at the end of the season does a furious Elsa discover the subterfuge; the final episode leaves Jules waiting in vain in a bar for her, and the three friends estranged after a bitter slanging match.

Making Jules an escort allows the character to conform superficially to the demands of the romance plot while his core person can be shielded from the less desirable aspects of the Casanova identity. What is more, the series is explicit about the new ambivalence of virile ‘romantic’ masculinity, repeatedly distancing its manifestations as passé and/or illusory. Thus, when the trio of girlfriends discover the photos of Jules at l’Hôtel de Ville on Elsa’s phone, while Charlotte – who choreographed and took them – evokes the highly nostalgic Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain positively as a keynote romantic comparison, Elsa reacts with distaste (S01, E01).Footnote9 Specifically, Elsa suggests that Jules’s pose, reclining on the floor in expensive-looking clothing (), makes him look like a GQ cover model with teeth that are too white. Adding that he probably wears ‘dick-hugging’ white Y-fronts [des moule-bite], she describes the setup as ‘extremely off-putting’ [une mise en scène hypermalaisante], with the French word choices emphasising both the discomfort (malaise) recurrent in (post-)#MeToo discussions of inappropriate displays of male sexuality, and also the staged nature of identity and romance (mise en scène).

Figure 1. Jules’s (Mark Ruchmann) ‘come hither’ look makes Zita Hanrot’s Elsa want to run a mile in Plan cœur (S01, E01).

Jules’s gallant persona is rendered all the more ridiculous when confronted with Elsa’s pointedly unfussy frankness and even ‘gross-out’ femininity (Strimpel Citation2016), a value typically associated with recent female-led Anglo-American postfeminist television shows from the aforementioned Girls to Broad City (Comedy Central, 2014–2019), Insecure (HBO, 2016–2021) and Fleabag (BBC3/Amazon Prime, 2016–2019), which are among Plan cœur’s most direct predecessor models. Thus, when Jules suggests they take a carousel ride after their first meeting, the hung-over Elsa says this might make her vomit again; or on their first date, when he removes her large glasses to gaze deep into her eyes, she protests she can’t see, blinking like a mole, then leaves him nonplussed by revealing that her voracious appetite for heavy meat dishes has led to her being nicknamed ‘Madame Porc’ (literally ‘Mrs Pig’, clearly evoking Miss Piggy) (S01, E01). The specificity of this detail cannot help but partially reorient the referential sphere of glossy anglophone television series towards a grotesque tradition associated par excellence with France via Mikhail Bakhtin’s theorisation of the medieval carnival through the prism of Rabelaisian comedy. Yet this has been famously taken up, in turn, by Kathleen Rowe Karlyn’s (Citation1995) work on unruly femininity in ‘global’ (US) film and television comedy, in which Miss Piggy serves as an emblematic figure, illustrating the long and complex history of cultural (and critical) intermixing. In any case, Elsa rejects ‘feminine’ self-surveillance when it comes to decorum as well as grooming. Typically wearing baggy sweaters, she is a far cry from the ideal of the neatly turned out Parisienne embodied by stars such as Catherine Deneuve, in earlier decades, or in more recent French romcoms by Sophie Marceau. It is the tall and well-proportioned Jules – and later Maxime, undergoing a moderate makeover to try to win Elsa back (S02, E02) – who is immaculately presented and self-governing, in a reversal that is still quite novel within French regimes of gender visibility.

Equally importantly, as well as being played for comedy, Jules’s patently tiresome insistence on lunging in for kisses when Elsa has given clear signals of discouragement is mitigated by knowledge that his interest is (initially) professional – the writers make sure to have him stipulate early on that his golden rule is never having sex unless the client wants to. All this paves the way for the revelation some episodes in that Jules is actually only a sex worker to help look after his mother, a concierge left near destitute by his father’s untimely death (S01, E04) (and secondarily, we find out in Season 2, pursue a creative career in music); masculinising the archetype of the tart with a heart, he takes on an endearing folkloric identity consonant with his ultra-ordinary – albeit pseudonymous – name, Jules Dupont. All these details banish any suggestion of rape culture that his behaviour could otherwise evoke. In other words, they create circumstances in which he can continue peddling his seductive pretence, until Elsa is finally won over by it (E03). Notably, she is impressed when he takes her backstage to a theatrical rehearsal that introduces the possibility of defamiliarisation propitious for romance (Illouz Citation1997, 26) – Elsa ruminates, ‘I hardly notice this city any more […] it’s a shame’, – in a sequence that underscores the mode’s inauthenticity by multiplying the layers of staging.Footnote10

The above example suggests the extent to which Plan cœur is reflexive in its recourse to ‘ImpersoNation’ (Elsaesser Citation2013), or playing up externally resonant features for export, in representing Paris as the timeless City of Love – but also a more modern glamorous playground for well-dressed and nice-looking twenty- and thirty-somethings (the title sequence featuring both tourist sites and bright night-time lights particularly milks the cliché). Jules’s elaborate performance to get Elsa into bed is no less obviously nationally accented in its redolence of the libertine tradition that was influential in eighteenth-century France, a chronotope further evoked by the decision to open the entire series with a shot of Jules passing through a dark red and gilt door to be received by a woman into an enclosed boudoir-like space reminiscent of the sets of Maison close (Canal+, 2010, 2013), about an eponymous fictionalised nineteenth-century Parisian brothel. A pretext not for literal time-travel but rather for anachronistic patterns of behaviour, the plot device constructs a genre-world that is both geo-culturally and temporally marked as ‘other’, in ways that cannot be parsed.

A contrario, the ongoing legacy of libertinage in contemporary Gallic culture is neatly illustrated by the fact that in a tribune published in Le Monde in 2011 the sociologist Irene Théry described what she saw as an impasse in French feminism, torn between a desire for equal rights and, in her words, ‘the surprise of stolen kisses’; what is more, when questioned about the statement seven years later, Théry stood by it (in Chemin Citation2018).Footnote11 This phrase refers to Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s well-known painting from the late 1780s, ‘Le Baiser à la dérobée’/‘The Stolen Kiss’, which adorns the cover of several editions of Choderlos de Laclos’s even more famous epistolary novel of libertinage from 1782, Les Liaisons dangereuses/Dangerous Liaisons. As Manon Garcia, Eva Illouz, and Camille Robcis (Citation2021) point out, the valorisation of kisses that, like Jules’s, are ‘stolen’ through pressure and pursuit – in other words, unbridled desire – is both a highly classed idea in France and one associable with a certain, older generation raised on post-Freudian theories about the damage of repression. These were adopted widely by the French bourgeois intelligentsia of the middle to latter part of the twentieth century – the same profile as the group of women behind the letter in Le Monde reacting to #MeToo. Such a comparison throws into relief the fact that this aspect of French culture intersects only partially and uneasily with the global postfeminist value of female sex positivity tacitly endorsed by Charlotte’s initial conviction that Elsa has every right to a satisfying bout of no-strings sex as a means of self-empowerment following a period of unhappiness. French openness about sex can therefore only be appropriated for Netflix’s (and Canal+’s, with Maison close) targeting of a postnational audience because this strategy also relies on a postmodern referentiality to delocalised (media) cultures (Jenner Citation2018, 227), obscuring specific histories. By sleight of hand, in this way, Plan cœur offers a wolf in sheep’s clothing: in Season 1, French otherness is tamed by being packaged with certain reassuringly familiar features of the series.

Among such overdetermined features of a major strand of Netflix fictions from multiple territories is a style which might be summarised as ostentatiously mediated. In common with numerous youth-focused and -oriented series set in affluent milieus from the Spanish Elite (2018–) to the Mexican Control Z (2020–2022, heavily indebted to the pre-Netflix Gossip Girl franchise) or the aforementioned Korean Joahamyeon Ullineun, among many others, screens are both omnipresent in Plan cœur’s mise en scène and central to its plot. More novelly, in many such fictions and extensively in Plan cœur, other aspects of digital culture bleed into its cinematography and form more generally in different ways. Thus, beyond the image’s already digital status and (to the keen eye) appearance, Plan cœur occasionally adopts an augmented reality approach quite popular on streaming platforms in which emojis or other computer-generated symbols escape the confines of embedded screens to invade the rest of the image, as well as deploying tricks such as speeding up or, less often, slowing down footage; split screens; a rapid editing rate; and a notably jerky handheld camera. The impression of jitteriness created aligns the world of Plan cœur with the temporally syncopated click-and-swipe experience of a digital device interface – especially in scenes simultaneously conveying its young female protagonists’ nervous energy.

The perhaps unexpected linkage of Jules’s ‘other half’ Elsa to traditionally masculine technological culture proves, however, quite superficial. This is typical of the way that altogether, postmodern surface details in Plan cœur (S01) – which also encompass dialogue stuffed with globally recognisable pop cultural references, often in English – mainly work to gloss underlying retro ideologies. In the first place, it is in fact Elsa’s lack of mastery over her mobile phone that provides the plot motor for the show. Alongside this detail, the opening shot of the series shows the character asleep in an unflattering position, snoring, with her mouth open and glasses askew (). She is covered with shame to be awoken by her therapist father welcoming his first clients to the living room-waiting room which she should have vacated earlier, also providing the show’s signature extract on the Netflix menu interface. Wholly embodying the ‘combination of post-feminist sophistication, romantic aspirations, and embarrassing physicality that has become a regular convention of twenty-first century [Hollywood] rom-coms’ (Deleyto Citation2011), Elsa is more specifically a successor to Bridget Jones. Suddenly single at 30, she is propelled into crisis mode, living on her father’s sofa as she works an uninspiring low-rung job at the Paris City Hall. Debasing herself by sending sexualised and/or aggressive messages to Maxime (including once by accident, continuing the theme of technological mismanagement), Elsa belies her insistence to Jules that she thinks women are perfectly happy single (S01, E01). She moreover at once evokes both a more locally inflected behemoth romcom heroine figure who has already been made an explicit reference point in the dialogue, Amélie Poulain, and also the ‘precarious girl’ of twenty-first-century anglophone television, whose abjection (vomiting, drooling) is reappropriated to signal not carnivalesque subversion or the explosion of feminist mystique but vulnerability (Wanzo Citation2016). Worse, the message that single women go hand in hand with emotional damage and even court physical risk is reinforced via the other female protagonists, as successful architect Milou’s excessively caustic, hard-bitten style of interaction with her supportive nurse boyfriend Antoine (Syrus Shahidi) is explained by the dramatic revelation that an earlier partner abandoned her at the altar, and Charlotte is preyed upon by a taxi driver (S01, E05). The latter’s consequent development in Season 2 of a female-only taxi service with an anglicised name, Pinkars, speaks to the post-2010 declarative popular feminist zeitgeist identified by theorists of postfeminism including Sarah Banet-Weiser or Rosalind Gill and resumed in transnational television studies under the banner of ‘emergent feminism’ (Nygaard and Lagerwey Citation2021, 33). However, the suggestion that single women are highly vulnerable in the first place feeds into an older discourse of panic-mongering designed to keep them at home; once again, the show is contradictory since Elsa had earlier offered a smart rejoinder to Jules’s offer to walk her home, ‘I can go home all by myself like a big girl’.Footnote12 In general, while it is closely allied with the narrative goals of romantic comedy as such, the borderline pathologisation of female singledom as part and parcel of the valorisation of strong, protective heroes is among Plan cœur’s most conservative manoeuvres.

Figure 2. More abject than Bridget Jones, Elsa’s identity as precarious singleton is constructed through belittling body comedy (S01, E01).

While it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss later seasons in as much depth, it is worth briefly considering the evolution of the male lead and attendant ideological discourses after Season 1, including questions of medium specificity that relate to constructions of both genre and gender. Season 1 is the most unapologetically romantic of the three. This is partly down to romance’s inherent status as endlessly deferred (Mitchell Citation1966): a narrative of pursuit and courtship. In her work on Master of None, Beatriz Oria (Citation2021) perceptively points out the way in which formal delay of the romantic resolution across episodes speaks to Berlantian ‘crisis ordinariness’, or the recognition of the implausibility of extant ideals – among which those of masculinity are salient – such that continuing to go after them can itself be read as self-evidently pathological (figurative ‘head trauma’). By Season 2, on the other hand, Elsa and Jules are together and he has taken on the ‘squeaky clean […] white knight’ identity embodied by 1990s Anglo-American romcom leads such as Hugh Grant (Hess Citation2020), explicitly evoked as a comparison point by the series’s Netflix (UK) teaser (); for instance, he ferries her around on his bike in the manner of a modern-day horseback chevalier (S02, E01) or offers physical gestures of strength, protectiveness and affection ().Footnote13 Accordingly, in this season obstacles to the central couple’s union are increasingly contingent, flimsy and implausible because Jules has assumed much of his earlier pretend identity, maintaining the more acceptably selfless and courteous aspects of chivalry while, importantly, downplaying its manipulative overtones. This is achievable because after Season 1 Jules’s gallantry is counterbalanced by an amplified sensitivity present in germ from the start through his caring attitude towards his mother. By Season 2, Episode 4, during a rift with Elsa, the broken-heartedness typically associated with the ‘new man’ in romcoms and other ‘chick’ texts (Burns Citation2011) is on full display as he plants himself prostrate on the sofa in the front room to receive concerned visitors. The casting of the slim-built Ruchmann and his metrosexual costuming in close-fitting suits or torso-hugging T-shirts, as well as a soft-voiced and for the most part smouldering performance of seduction, had also already opened the door to the possibility of expanding Jules’s feminisation. The class intersectionality of this styling, already apparent through the tastefully expensive-looking clothes and décor associated with Jules (sophisticated charcoal fabric on his body tones with a chocolate brown leather sofa), comes into relief by recalling the wide association of bourgeois consumer culture with women since at least the nineteenth century depicted by Émile Zola’s 1883 novel Au bonheur des dames/The Ladies’ Paradise.

Figures 3 and 4. Both paratextual (UK teaser) and textual (S02, E02) elements of Plan cœur evoke the white knight archetype in connection with Jules.

Moving forward in terms of referentiality, the neutralisation of traditionally masculine traits in Jules’s characterisation is neatly encapsulated by his increasing association with electronic music throughout the course of the series.Footnote14 As Birgit Richard and Heinz Hermann Kruger have argued, techno, ‘with its emphasis on the sheer fun of dancing and on body movement […,] is a less misogynist culture’ than other styles of dance music and altogether unificatory in its listener address (Richard and Kruger Citation1998, 168–169, 162) – Jules’s signature track by Frédéric Magnon, which has gained some popularity on YouTube, is aptly named ‘Close to Me’ – notably mirroring digital streaming platforms’ uncoupling from material bodies (nation among them). Alongside female-accented plot elements such as Season 3’s sympathetic depiction of abortion (for Milou) and breast cancer (for Charlotte) and the overall amplified importance of feminist sorority later in the series, Jules’s updating speaks to a familiar trajectory traced by series on streaming platforms, evolving over different seasons to better fit the demands of their producer-distributor and its international audiences. But the change also underlines the way in which the postnationally inflected surface sheen ultimately reworks the deeper-rooted structure it started off by merely adorning. The central narrative arc may appear utopian, yet it is also performative since audiovisual fictions ‘define and demonstrate socially sanctioned ways of falling in love’ (Wright-Wexman Citation1993, ix).

With this in mind, the ethnicities of the (gendered) characters analysed here as enacting these ‘ways of falling in love’ are of some note, as a key aspect of their legitimising work. Plan cœur’s three female leads mimic the black blanc beur trio associated with ‘authentic’ Frenchness on the world stage by the blockbuster success of banlieue drama La Haine (Mathieu Kassovitz, 1995) (). The authenticity of such a multi-racial representation was questionable from the outset, not least in view of Kassovitz’s White (though Jewish) identity, and Plan cœur’s key creative team provides no divergence from this model. While a 2021 report on Netflix’s diversity record carried out by USC Annenberg on the company’s behalf connects a statistical lack of diversity in front of the camera to the still too homogenous identities of personnel behind it (see Boorstin Citation2021), in the case of Plan cœur, diversity of representation is also qualitatively superficial. This is because wider cultural issues connected to non-Gallic ethnicities are almost entirely absent from the plot – and entirely so from Elsa’s narrative as the daughter of a Black father and a White mother styled entirely according to European codes of beauty, including through hair-straightening. Nor is it incidental that the four principal men in Plan cœur are less racially diverse, with protagonist Jules being of Portuguese heritage and only Syrus Shahidi – who is of Iranian descent but who plays Charlotte’s brother, the putatively second- or third-generation North African Antoine Ben Smirès – departing from White Frenchness. Given the historical position of women as objects of exchange in both family- and nation-building, multiplying the ethnicities of women rather than their male counterparts in métissage plots (which in and of themselves have become less unusual in post-2010 French romcoms, in line with statistical realities) arguably ticks diversity boxes while posing little fundamental challenge to republican French universalism – especially when we consider the increasingly unmarked absorption of beur identities (unlike Black ones) into onscreen visual displays of Frenchness. Further, Antoine, as a professional nurse, is by far the most feminised of all the male characters, sloughing off his potential toxicity from Blockbuster and ensuring no spectre of patriarchal Islamic culture colours his persona. Tempering ethnic differences in such ways denies visibility to minority French identities as experienced by real subjects. In the universalist context that conceptualises France as an ethnically homogenous community, this has been equated with denying them rights (Macé Citation2007). Yet the approach is simultaneously typical of many contemporary television series from elsewhere in the Global North:Footnote16 just as ‘global’-feminist sex positivity updates a Gallic drive to valorise carnality in Plan cœur, the narrative’s deployment of multi-ethnic characters ‘operat[ing] within [privileged] White people’s cultural norms’ (in particular, the palatial dimensions of Elsa’s father’s flat articulate classless fantasies) speaks to a ‘quality’ comedy ‘aesthetics of Whiteness’ now common even in anglophone series featuring non-White characters (Nygaard and Lagerwey Citation2021, 12–14).Footnote17 The obvious interpretation is to see the series’s racially mixed casting as profit driven. Theatrically released films including comedies featuring different ethnicities from both France (see Rosello Citation2018) and the USA (Asava Citation2017) have enjoyed considerable international success, Intouchables/Untouchable (Eric Nakache and Olivier Toledano, 2011) being a well-known Gallic example from this millennium. Regarding the specific choice of Hanrot for the female lead, if it has been argued that mixed bodies have been commodified within and as emblems of global capitalism (in Asava Citation2017, 6), this is no doubt especially true in the context of the international, i.e. multi-racial, market of streaming platforms (cf. Nygaard and Lagerwey Citation2021, 51). If the series’s blend of contemporary film and television genres with eighteenth-century literature displays a postmodern tendency to collapse together histories, the show equally erases the particularities of its colonial past in favour of a commodified ‘plastic representation’ (Warner Citation2017) of multi-ethnic France.

Figures 5 and 6. A poster for Plan cœur recalls and feminises the black blanc beur triptych of La Haine.Footnote15

Anxiety and atemporality in Je ne suis pas un homme facile

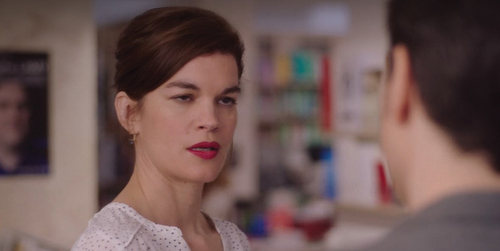

While Plan cœur can be read through reference to metaphorical time-travel and head trauma, Je ne suis pas un homme facile is much more literal in its deployment of these tropes to stage its battle-of-the-sexes love story. Based on a short film named Majorité opprimée/Oppressed Majority (2010) by openly feminist writer Eléonore Pourriat, the feature opens with a focus on skirt-chasing forty-something Damien (Vincent Elbaz). After a prologue and a brief scene with his psychiatrist (played by Pourriat), we see Damien at work proposing an app that tracks male sexual prowess; when asked by a female colleague about targeting women, he quips that they are well represented, ‘blonde, brunette, Asian…’ [blonde, brune, asiatique…] – in other words, as objects. While good-looking, immaculately dressed and charming Damien’s jokey belittlement of women goes down well in the male-dominated office, it grates more loudly in a subsequent scene at a book launch for his best friend, Christophe (Pierre Bénézit), where he attempts to flirt with an editorial assistant, Alexandra (Marie-Sophie Ferdane). Entreating the tall and glamorous woman to repeat the name of the drink she is offering with a polite smile, a mimosa, because ‘your mouth makes a pretty heart-shape’, he is met with an eye-roll and the cold shoulder.Footnote18 Forced to try the same line on a more willing victim, Damien exhibits behaviour no less theatricalised than Jules’s, a typical mode of expression in situations where Frenchmen’s social experiences of dominant mores are mismatched with their internal understandings of their identities (Lapeyronnie and Courtois Citation2008, 17). The scene addresses the same ‘enlightened’ feminist position addressed by those featuring Jules’s outmoded seduction techniques, situating the viewer as in on the joke about these men with no clue as to their obsolescence. Indeed, the dismayed female visage is a repeat marker of the affect of cringe, and the concomitant tone of disapproval, established by this duo of romcoms featuring retro French masculinity as an identity ripe for reconfiguration (). While the effects of texts on audiences remain speculative, it is apt to mention one Twitter user’s comment that Je ne suis pas un homme facile ‘makes the smile freeze on your face’, in an apparent demonstration of Linda Williams’s well-known (Citation1991) account of how body genres such as melodrama and (later theorists would add) comedy work by inducing a kind of affective mimicry in their spectator.Footnote19

Figure 8. Alexandra of Je ne suis pas un homme facile rolls her eyes and turns away from Damien’s (Vincent Elbaz) tired chat-up lines.

Soon after thus being set up as a Lothario, Damien walks into a lamp post and hits his head while ogling some teenage girls, only to wake up and discover the world has become a matriarchal society, in which he suffers forms of oppression women report encountering daily, from being expected to dress a certain way () to being aggressively harassed. In the foreground romcom plot, Alexandra is now the successful novelist for whom Christophe works in a lower-rung job, until his need to take time off for paternity leave means Damien steps into the role, as well as becoming his boss’s sexual plaything. In this way, the majority of Je ne suis pas un homme facile’s narrative takes place in a world in which pronounced gender difference is still entirely preserved – perhaps unsurprisingly, given that this is arguably a prerequisite for romance as traditionally understood and packaged in mass popular formats. In one sense, the matriarchy provides a means of getting around the nonviability of former coupling structures: swapping gender roles makes space through humorous reversals for passé dynamics that would otherwise be anathema to many contemporary Netflix audiences. Moreover, as in Plan cœur, the trope of fantasy allows Damien’s ‘red-blooded’ masculinity to be at once neutralised and still preserved to an extent. For instance, he loses his cool on one occasion in the face of his parents’ constant hints that he should find a girlfriend, insisting that he has plenty all over Paris and indeed the highest condom use rate of the city! Indeed, while both Plan cœur and Je ne suis pas un homme facile may be internationally palatable texts with something for everyone to take away from them, they still retain the recognisably culturally Gallic feature of centralising sex, as the glue bringing together the main characters.

Nevertheless, although its predecessor short film was made in 2010 (but only received widespread attention in 2014 when English subtitles were added), what makes Je ne suis pas un homme facile a post-#MeToo product is the fact that something like those events seems to be going on in the society to which Damien is transported, where there are background references to new charges being levelled against female public figures by male victims, while Damien joins a ‘masculinist’ protest group called Nichons-nous Partout (roughly, ‘Busting through Barriers’, as the French is an exhortation to ‘slip into every space’ but plays on the word nichon, meaning ‘boob’) that absurdly wear fake breasts at public events, presumably in reference to the real feminist group La Barbe [The Beard], who do the same with beards. Altogether, the film’s action, in forcing a male to undergo gendered indignities familiar to women, may offer catharsis to female viewers. Like Plan cœur, it subverts the male gaze, including coinciding with the series in featuring a (now more extensive) male makeover, as Damien is forced to review his wardrobe and (like Maxime) depilate his body. However, its political subtext is surely a call for greater equality and mutual respect between the genders, since simply by reversing the poles of the male–female binary the narrative suggests that inequality as such only breeds oppression. This message is not merely spoon-fed to the viewer but rather graphically figured by the work of a mise en scène that denaturalises the submissive role Damien is forced to inhabit: the impracticality of tiny shorts at work is brought home when they are paired with manly legs, however shapely and shaven (see ). By the end of the film, even Damien appears to have made this realisation through the lived experience of its consequences, since Alexandra is now magically transported to his world to find him protesting for women’s rights.

It is also highly suggestive that the opening interaction with his therapist shows Damien discussing symptoms, including protracted toothbrushing, consistent with OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder, also in evidence afflicting the retro male hero of Un peu, beaucoup, aveuglément). The juxtaposition of this scene with the mimosa incident in which his seduction technique falls flat points to a masculinity in crisis, flailing to reassert itself, for OCD is clinically associated with both control and narcissism. In other words, just as his innate ‘feminine side’ was already signalled by the same markers of metrosexual androgyny displayed by Jules (sharp suits, slim physique, soft voice), Damien was pathological before being hit on the head and the off-kilter world to which he travels holds up a glass through which to see contemporary (French) society refracted. Nowhere is this more apparent than in a scene in which he and Alexandra visit a gay nightclub self-reflexively named Recto Verso, and, not for the first time in the film, a canted camera angle uses spatial imbalance to evoke historical temporality askew (). Describing the action of both Je ne suis pas un homme facile and Plan cœur through the phrase out of time takes on a double meaning here: not only are the worlds evoked at the start of each narrative marked by lag, then later by other elements of temporal confusion, situating them firmly outside contemporary social reality, but time has also run out for anachronistic masculinities within them – as stridently proclaimed by the hashtag that followed on the heels of #MeToo, #Time’sUp.

Figure 10. A canted angle speaks to a world both out of kilter and out of step with contemporary norms.

The focus on male suffering in both narratives but especially Je ne suis pas un homme facile (), meanwhile, also has a certain French lineage established by mega-star actors from Jean Gabin to Depardieu. Yet the Netflix film trades in a postmodern reflexivity only slightly less declarative than the television series’s, which undercuts the possibility of sincere melodramatic engagement. For instance, Damien ‘turns on the waterworks’ in the film only in order to get a concierge to help him when he is locked out, in a parody of so-called feminine wiles. Elsewhere, once again the over-determination of Paris as a romantic location is the subject of winking acknowledgement, as Damien reflects, ‘When you’re in love in Paris, you’re like a tourist’.Footnote20 Although relentless explicit call-outs to other screen fictions often seen in streaming platforms’ products are here absent, the choice to cast Elbaz is likely to resonate at home by ironically invoking his repeat roles as a regressive if loveable male in comedies such as Ma Vie en l’air/Where is the Love? (Rémi Bezançon, 2005) and Daddy Cool (Maxime Govare, 2017). The casting of forthright and sexually taboo-busting feminist comedian Blanche Gardin in a supporting role as Damien’s acquaintance Sybil is even more tongue-in-cheek, since she is first seen lapping up the protagonist’s chat-up lines before being reinvented in the matriarchal world as a lecherous woman who takes Damien to a (male) striptease-club, initiates boisterous sex, then refuses to sleep with him because of his body hair.Footnote21 That such allusions wink to domestic audiences may reflect the contrasting production circumstances between Plan cœur, dreamed up by British co-creator Chris Lang in collaboration with French colleagues including director Noémie Saglio, and the more home-grown, auteur-led Je ne suis pas un homme facile, but it also offers a potential ironic outlet for French viewers alienated by moralising.

Figure 11. Publicity for Je ne suis pas un homme facile offers a gently parodic take on French male suffering.Footnote22

On the other hand, just as Elbaz’s North African Jewish roots were foregrounded in his star identity through his most famous role in the major hit film series La Vérité si je mens/Would I Lie to You? (1997–2012), centred around this community, multiculturalism is also championed by this film – and more explicitly in opposition to French universalism than was the case in Plan cœur – in the form of a scene showing distressed veiled men being aggressively hounded out of public space. This detail suggests a closer allegiance with ‘global’ (neo)liberal values than republican ones. Interestingly, a number of French user reviews available on the website Allocine.com, one of the few sources of aggregated qualitative data for products on French Netflix, pick out this episode for censure: ‘Jiminou76’ reports that ‘seeing intolerance towards the veil through the prism of sexism’ literally made them leave the room, while ‘Raphaël P’ (who awards the film 0.5 out of 5 stars) is moved to cite a Slate magazine writer’s sceptical remark that ‘Apparently we shouldn’t ignore the testimonies of women who claim wearing the veil allows them to live in a certain peace. Peace may mean a bit more freedom but it doesn’t equate to equality or emancipation’.Footnote23 As the reference to this article reflects, the wearing of the veil is a hotly contested issue in French – as well as global – cultures, as numerous well-publicised legal tussles and instances of protest about the right to the hijab in public space attest. In this context, what Noël Burch (Citation2008) calls the ‘literary salon’ feminism also described earlier in relation to an older, highly educated French female demographic behind the opposition to #MeToo, has been seen as an alibi for the kind of monocultural hegemony many have accused so-called universalist credos of masking (Burch Citation2008; see also Abu-Lughod Citation2013) – a positioning that Je ne suis pas un homme facile resists.

Similarly, the comparison with Gabin or Depardieu, both figureheads for working-class male suffering, further foregrounds by way of contrast the extent to which the knowing sensibility typical of much postmodern comedy, which both permeates Je ne suis pas un homme facile and is particularly embodied by ‘world-travelling’ metropolitan dandy Damien/Elbaz, by tacitly appealing to specific knowledge and taste, is intimately bound up with Netflix’s translocally elite positioning.Footnote24 As a paid subscription platform, in other words, Netflix offers a propitious home for romcom in general, in the first place as a genre typically centralising the personal lives of the wealthy, but also a highly self-reflexive one ideally placed to appeal to global culture-literate cosmopolitan elites. Unsurprising, then, to find a (relatively rare) French review of the film by right-wing newspaper Le Figaro excoriating its ‘political correctness’ (Benedetti Citation2018), as this is widely viewed as a US import. In fact, Je ne suis pas un homme facile is unusual in scoring more highly in user reviews on the international, almost exclusively anglophone site IMDb (where it averaged 6.3 out of 10) than on Allocine.com (where it averaged only 5.8). More, then, than Plan cœur with its timid and ambivalent repudiation of retro French gallantry – and which accordingly conformed to the usual pattern of scoring higher on Allocine.com (average rating 7.8). than on IMDb (average rating 7.2) – the explicitly, didactically progressive Je ne suis pas un homme facile’s principal appeal lies with Netflix’s international audience. Despite – or perhaps because of – its entirely domestic roots as an adaptation of a French short film, the feature represents a more fully postnational product.

***

Before concluding, it is worth lingering on ways in which self-awareness ties in not just with the travel of products into international markets, but also with intratextual time-travel tropes in the fictions analysed in this article – an apprehension with implications for how relevant texts interpellate, and construct anew, postnational communities. Both Steve Neale (Citation1986) and René Thoreau Bruckner (Citation2015) have analysed time-travel films in terms of a desire to return to our own origins, an Oedipal drive laid bare by the plot of one of the most successful of such films of all time, Robert Zemeckis’s 1985 classic Back to the Future, where the main character nearly marries his mother in the past. Further, as Bruckner (6) observes, the time-traveller gains the advantage of superior knowledge, a knowledge achieved through a splitting of the self (i.e. present, time-travelling self and past, innocent self) that also recalls psychoanalytic theory. Neale (Citation1986, 12–16), in fact, suggests the whole driving force of the popular genres of both melodrama and comedy is to satisfy a wish to return to a nostalgic fantasy of childhood characterised by union with the mother, a state of total satisfaction and dyadic fusion – also a common post-Freudian view of romance. Time-travel films, for Neale, simply literalise this wish. Given that his analysis notes that the protagonists of melodrama seek to construct the world itself in their own image as a kind of stand-in for maternal plenitude, very often following creative professions (16), it is not incidental that Jules of Plan cœur is a musician and Damien of Je ne suis pas un homme facile designs an app to mirror, track and influence human behaviour – sexual mores, no less – while the hyper-masculine figure embodied by Alexandra for the majority of that film is a writer, and also focused on sexuality and relationships. The collision with a lamp post as Damien admires teenaged girls can be seen from this perspective to figure the disjuncture between his worldview and recalcitrant realities. Narratives involving time-travel offer, then, narcissistic potential for recreating the self in an improved version, rewriting the past by returning to the primal scene evoked by Constance Penley in her work on cognate sci-fi films (in Bruckner Citation2015, 6). In Je ne suis pas un homme facile the trauma of gender difference is overtly situated as the root of Damien’s neuroses, since the film’s prologue – directly preceding the scene with his therapist – shows him in nursery school as a small boy, where both the audience and a little girl he likes laugh at him for wearing a dress in the school play. Shot in ironic sepia, this scene telegraphs trauma through a zoom in to the diminutive Damien’s own horror-struck countenance, as he stands marooned on a stage that is suddenly gapingly empty, followed by a series of dissolves shuffling between close-ups of cruelly laughing onlookers. Later, in another instance of the neurotic compulsion to return to dissatisfactory histories, a universal primal scene is rescripted, as Alexandra tells Damien that in her world the women were physically stronger when humans lived in caves because they bore children, so became the hunter-gatherers. Plan cœur is no less obsessed with origins stories. Here, the ending of Season 3 figuratively reworks the series’s own televisual past, to the extent that in its final episode Elsa tells Milou about Jules’s restaging of their initial encounter, which we see in flashback, therefore doubly deferred. He has sent her a photo of him on her phone imitating the original one via which he approached her; now, though, the dinner date details are overwritten with a suggestive invitation to join him ‘on the trail of our story’ ().Footnote25 In this way, the potentially creepy, stalkerish and literally profit-driven elements of his original pursuit of Elsa are redeployed as a gesture of selfless love, as she explains that Jules’s act is part of a campaign to cheer her up about the fertility struggles that are a motor of conflict in Season 3.

In all these examples, the splitting of the masculine figure carves out a space for the recuperation of a more loveable self while retaining much of its familiar, chequered, guise: for rewriting the past to rewrite the present and future. This is also the work effected by these texts at the level of (post)national identity-formation, in constructing a Gallic masculinity evolving seamlessly from its own cultural history but better attuned to modern sexual and other norms. And what better emblem for this newly globalised national identity than the baby Jules and Elsa adopt from Brazil and bring back to France at the end of Season 3, at once focalising a global theme and figuring the cultural hybridisation of (post)national bodies (including through a form of ‘first-world’ cultural appropriation)? To underline the point, the new arrival is dressed in a South American-style knitted bonnet to maintain some (surface) trappings – the new parents earnestly report – of his heritage.Footnote26

The limits of these romcoms’ progressive politics, often owing to their inextricability from commercial motives, have been signalled at every turn in this article. As well as propping up a shallow conception of ethnic diversity and so intersectional feminism, discourses of popular (post)feminism – like those of ‘progress’ itself – have been salient here, as an increasingly ‘splashy’ alibi of capitalism (Aschoff Citation2015, 27–28). Nevertheless, my comments on national self-reinvention nonetheless make clear the potentially fundamental nature of the negotiations of French masculinity in which these fictions engage. In both cases, Frenchness is produced with a variegated but cosmopolitan export market at the forefront of considerations, resulting in narratives that underline but also transcend local markers and values in constructing gender roles. However, Je ne suis pas un homme facile is more radical than Plan cœur in its questioning of the status quo. The series’s sheen of global modernity remains extremely flimsy when it comes to not only race but ultimately gender too, as the space for autocritique is closed down after Season 1 by the evacuation of ‘toxic’ masculinity from the French romantic hero: fantasy and reality are collapsed together diegetically. In contrast, just as it tackles intersections between feminism and race directly, Je ne suis pas un homme facile also maintains a much more critical edge towards contemporary French masculinity by holding its predominant genre world (the fantasy) up as a foil to the real one seen in the opening sequences and the closing shots of the film. In other words, realities are never wished away wholly. Continuing to advertise its status as a symbolic means to engage with the everyday, the film opens up a gap between different visions of Frenchness. It does not reimagine history in wilful ignorance of the tenacious structures of oppression this has put in place but rather points towards a path for slowly beginning to shift them.

Popular feminism is an affective value which gains in postnational translatability what it loses in intellectual depth by being emptied of most of its socio-political specificity. The texts analysed in this article demonstrate that the collision of gender norms from different cultures does represent an opportunity to promote greater gender equality that is taken up differently by individual artefacts. Since cultural texts’ affective tone is linked to genre tropes (here, repeat instances of calling out misogyny or celebrating equality), these determine narratives’ ‘general disposition or orientation towards [their] audience and the world’ (Ngai Citation2007, 28). The generic standardisation of social norms in postnational texts can therefore apostrophise new groups and create international communities based – to paraphrase Charles Acland – on felt recognition.Footnote27 Moreover, the mainstream format, drawing a wide viewership by achieving its ideological critique through humour, offers at least a possible means to reach beyond the closed circles of extremely ideologically homogeneous groups preaching only to themselves that are too often the by-products of culture wars, and of the increasingly polarised views of gender roles characterising the Western world at the present moment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mary Harrod

Mary Harrod is Associate Professor in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Warwick. She has published widely in the areas of transnational screen cultures and gender issues in film and television, with a principal focus on popular screen fiction from Europe, especially France, and the USA. With Ginette Vincendeau, she is co-Chief General Editor of French Screen Studies.

Notes

1. “Top Grossing Romantic Comedy Films of All Time” (listchallenges.com).

2. “The Best and Worst Romantic Movies on Netflix, Ranked” (insider.com).

3. See for example Amazon Prime’s ‘original’ Forte/Ballsy Girl (2020).

4. See also Harrod and Moine (Citation2023).

5. For accounts of French gallantry, see Habib (Citation2006) and Viala (Citation2008).

6. The phrase is taken from Jeffers McDonald (Citation2019).

7. The featuring of characters in their early twenties in Friendzone (Charles Van Tieghem, 2021) (also distributed but not originally produced by Netflix) may also suggest a move to rejuvenate the genre, while the high concept title undercuts this male protagonist’s virility from the outset.

8. For an extended discussion of Un peu, beaucoup, aveuglément from the overlapping perspective of postfeminist culture, see Harrod (Citation2022).

9. The comparison is particularly cogent since the location’s Carrousel de la Belle Époque is visible in the background when Jules and Elsa first meet, just as Amélie Poulain leads her love object on a trail past similar rides.

10. ‘Je la regarde plus cette ville […] c’est dommage’.

11. ‘la surprise délicieuse des baisers volés.’

12. ‘Je peux rentrer toute seule, comme une grande.’

13. The Hook-Up Plan | Teaser [HD] | Netflix – Bing video. At the same time, whereas Jules’s characterisation in Season 1 downplayed while maintaining virile masculinity, in Season 3 Maxime comes to embody a caricatured ‘toxic’ alpha male, with the series relying on comic exaggeration to blunt misogyny’s menacing edge, before his female friends explicitly re-educate him.

14. It can be no accident that Season 1, Episode 2 first introduces us to Jules composing in front of a poster for Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999), a film iconically associated with the jostling for supremacy of older ‘virile’ and more contemporary, ‘effeminate’ masculinities.

15. Poster sourced from https://nexttimeonblog.com/hook-up-plan-cute-rom-com/.

16. In contrast, the single-season French Netflix multicultural romcom series Drôle/Standing Up (2022) broadens the archetype of the French romantic hero seen on streaming platforms to include a beur character (see Harrod Citation2023), while still oscillating between gender differentiation and a ‘postfeminist’ post-racial ethic of sameness which is itself problematic. Black romantic heroes are generally rarer in French representational regimes as a whole, but do appear occasionally in culture clash comedies including romantic elements, either with a socio-realist bent (Samba [Nakache and Toledano, 2014, featuring a severely socially disempowered migrant character played by Omar Sy) or directed by a Black filmmaker (La Première Étoile/Meet the Elizabeths [Lucien Jean-Baptiste, 2009], Il a déjà tes yeux/He Even Has Your Eyes [Jean-Baptiste, 2016, available on Netflix]).

17. Plan cœur fulfils almost all the criteria of the ‘Horrible White People’ shows that Taylor Nygaard and Jorie Lagerwey (2021) accuse of covertly propping up White supremacy whatever the skin colour of protagonists: ‘affluent, liberal, urban-dwelling, highly educated characters […;] high production values on a streaming platform’. It also contains elements of the final trait listed, ‘bleak, self-critical comedy’ (often romantic [4]), but this is ultimately abandoned in favour of a more traditionally postfeminist focus on growth and positivity now dated in US culture. The series is also retro in including queer characters only in very secondary roles.

18. ‘ta bouche forme un cœur, c’est joli.’

19. ‘te congela la sonrisa’, Santiago Poza, Spain, 28 February 2022, https://twitter.com/sin_ofender_t/status/1498228516277600259. Searching Twitter for allusions to this film in English, French or Spanish attests to highly international engagement with Je ne suis pas un homme facile, including a number of screenings in Latin American countries that used it as a stimulus for discussion of gender roles.

20. ‘Quand on est amoureux à Paris on est comme des touristes.’

21. Thanks to Ginette Vincendeau for familiarising me with Gardin.

22. Poster sourced from https://fr.flixable.com/title/i-am-not-an-easy-man/.

23. ‘voir l’intolérance au voile par le prisme du sexisme’; ‘Nous ne pouvons également ignorer ces témoignages de femmes disant que porter leur voile leur garantit une forme de tranquillité. Tranquillité signifie un peu plus de liberté, mais aucune égalité, aucune émancipation.’

24. On Gabin, see Vincendeau (Citation1995; Citation2000, 59–81) and on Depardieu’s latter career, Moine (Citation2017, 79).

25. ‘sur les traces de notre histoire.’

26. Interestingly, South America is even more openly subsumed under French identity in Season 2 when it is revealed that, instead of moving to Buenos Aires in retaliation for her female friends’ ruse, Elsa has simply rented a flat in Paris’s Rue de Buenos Aires.

27. Acland (Citation2005, 239) discusses ‘felt internationalism’.

References

- Abu-Lughod, L. 2013. Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard UP.

- Acland, C. 2005. Screen Traffic: Movies, Multiplexes, and Global Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Alévêque, A. 2018. “Nous défendons une liberté d’importuner, indispensable à la liberté sexuelle.” Le Monde, January 9.

- Asava, Z. 2017. Mixed Race Cinemas: Multiracial Dynamics in America and France. London: Bloomsbury.

- Aschoff, N. 2015. The New Prophets of Capital. London and New York: Verso.

- Benedetti, A. 2018. “Je ne suis pas un homme facile: l’ultime naufrage du politiquement correct.” Le Figaro, July 5. https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/2018/07/05/31003-20180705ARTFIG00193-je-ne-suis-pas-un-homme-l-ultime-naufrage-du-politiquement-correct.php.

- Berlant, L. 2008. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Boorstin, J. 2021. “Netflix Will Spend $100 Million to Improve Diversity on Film Following Equity Study.” CNBC Online. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/02/26/netflix-will-spend-100-million-to-improve-diversity-on-film-following-equity-study.html#:~:text=The%20USC%20Annenberg%20Inclusion%20Initiative%20produces%20regular%20reports,disabilities%29%2C%2019%20showed%20improvement%20over%20the%20two-year%20period.

- Bruckner, R. T. 2015. “‘Why Did You Have to Turn on the Machine?’: The Spirals of Time-Travel Romance.” Cinema Journal 54 (2): 1–23.

- Burch, N. 2008. “‘Pudeur’ et ‘libertinage’, Retour sur le foulard, abusivement appelé ‘voile’.” Mauvaise Herbe (Blog), April 11. https://mauvaiseherbe.wordpress.com/2008/04/11/%c2%ab-pudeur-%c2%bb-et-%c2%ab-libertinage-%c2%bb-retour-sur-le-foulard-abusivement-appele-%c2%ab-voile-%c2%bb/.

- Burns, A. 2011. “‘Tell Me All about Your New Man’: (Re)Constructing Masculinity in Contemporary Chick Texts.” Networking Knowledge: Journal of theMeCCSA Postgraduate Network 4 (1). https://ojs.meccsa.org.uk/index.php/netknow/article/view/65/65.

- Chemin, A. 2018. “Le « féminisme à la française », selon la sociologue Irène Théry.” Le Monde, February 1. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2018/02/01/le-feminisme-a-la-francaise-selon-la-sociologue-irene-thery_5250434_3232.html?fbclid=IwAR3q-eHsvlS1ci8jnH0ZDlcXryodYHGecJsCAhwGC5-VGFAqWa6d5BnCL7c.

- Cobb, S., and D. Negra. 2017. “‘I Hate to Be the Feminist Here…’: Reading the Post-Epitaph Chick Flick.” Continuum 31 (6): 757–766.

- Deleyto, C. 2009. The Secret Life of Romantic Comedy. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

- Deleyto, C. 2011. “The Comic, the Serious and the Middle: Desire and Space in Contemporary Film Comedy.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies 2 (1). http://jprstudies.org/2011/10/the-comic-the-serious-andthe-middle-desire-and-space-in-contemporary-film-romantic-comedy-by-celestino-deleyto/.

- Elsaesser, T. 2013. “ImpersoNations: National Cinema, Historical Imaginaries and New Cinema Europe.” Mise au point 5. https://doi.org/10.4000/map.1480.

- Garcia, M., E. Illouz, and C. Robcis. 2021. “Changing Norms of Sexual Consent in Contemporary France.” Online Round Table, New York University, March 24.

- Habib, C. 2006. Galanterie française. Paris: Gallimard.

- Harrod, M. 2015. From France with Love: Gender and Identity in French Romantic Comedy. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Harrod, M. 2020. “‘Money Can’t Buy Me Love’: Radical Right-Wing Populism in French Romantic Comedies of the 2010s.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 18 (1): 101–118.

- Harrod, M. 2022. “Nostalgia, Melancholy, Trauma: Backlash Postfeminism in Contemporary French Screen Romance.” Nottingham French Studies 61 (3): 208–226.

- Harrod, M. 2023. “From ImpersoNation to ImPosture: (Sub)urban Fantasy in Fanny Herrero’s Dix pour cent and Drôle.” In Is It French? Popular Postnational Screen Fiction from France, edited by M. Harrod and R. Moine. London: Palgrave. Forthcoming.

- Harrod, M., S. Leonard, and D. Negra. 2021. “Introduction: Romance and Social Bonding in Contemporary Culture – Before and After COVID-19.” In Imagining “We” in the Age of “I”: Romance and Social Bonding in Contemporary Culture, edited by M. Harrod, S. Leonard, and D. Negra, 1–28. London and New York: Routledge.

- Harrod, M., R. Moine. 2023. “Introduction: The Expanding Imagination of Mainstream French Films and Television Series.” In Is It French? Popular Postnational Screen Fiction from France, edited by M. Harrod and R. Moine. London: Palgrave. Forthcoming.

- Henderson, B. 1978. “Romantic Comedy Today: Semi-Tough or Impossible.” Film Quarterly 31 (4): 11–23.

- Hess, A. 2020. “Hugh Grant’s Undoing: How Romcom Leading Men Embraced the Dark Side.” The Guardian, November 30. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/nov/30/hugh-grants-undoing-how-romcom-leading-men-embraced-the-dark-side.

- Illouz, E. 1997. Constructing the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Jeffers McDonald, T. 2019. “Romantic Comedy Today: Teenagers, Head Trauma and Time- Loops?” Paper delivered at Imagining “We” in the Age of “I” study day, Warwick, UK, March 29.

- Jenner, M. 2018. Netflix and the Re-Invention of Television. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lapeyronnie, D., and L. Courtois. 2008. Ghetto urbain: ségrégation, violence, pauvreté en France aujourd’hui. Paris: Laffont.

- Macé, É. 2007. “Des ‘minorités visibles’ aux néo-stéréotypes.” Journal des anthropologues (Hors–série): 69–87.

- Mitchell, J. 1966. “Women: The Longest Revolution.” New Left Review 40 (1). https://newleftreview.org/issues/i40/articles/juliet-mitchell-women-the-longest-revolution.

- Moine, R. 2017. “Sous le signe de l’excès: le « troisième âge » de Depardieu entre déchéance at rejuvénilisation.” In L’Âge des stars: des images à l’épreuve du vieillissement, edited by Charles-Antoine Courcoux, Gwénaëlle le Gras, and Raphaëlle Moine, 76–93. Lausanne: Éditions l’Âge d’Homme.

- Neale, S. 1986. “Melodrama and Tears.” Screen 27 (6): 6–23.

- Ngai, S. 2007. Ugly Feelings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nygaard, T., and J. Lagerwey. 2021. Horrible White People: Gender, Genre, and Television’s Precarious Whiteness. New York: New York University Press.

- Oria, B. 2021. “Facing the Fig Tree: Representations of Contemporary Intimacy Culture in Master of None.” In Imagining “We” in the Age of “I”: Romance and Social Bonding in Contemporary Culture, edited by Mary Harrod, Suzanne Leonard, and Diane Negra, 77–92. London and New York: Routledge.

- Richard, B., and H. H. Kruger. 1998. “Raver’s Paradise? German Youth Cultures in the 1990s.” In Cool Places: Geographies of Youth Cultures, edited by T. Skelton and G. Valentine, 162–175. London: Routledge.

- Rosello, M. 2018. “L’émergence des comédies communautaires dans le cinéma français: ambiguïtés et paradoxes.” Studies in French Cinema 18 (1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14715880.2016.1264752.

- Rowe Karlyn, K. 1995. The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- San Filippo, M. 2021. After “Happily Ever After”: Romantic Comedy in the Post-Romantic Age. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Strimpel, Z. 2016. “Welcome to the New Feminism – Where the Aim Is to Gross You Out.” The Conversation, September 28. https://theconversation.com/welcome-to-the-new-feminism-where-the-aim-is-to-gross-you-out-65579?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20September%2029%202016%20-%205698&utm_content=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20September%2029%202016%20-%205698+CID_43598ef8db1ceef290ee416355a3b818&utm_source=campaign_monitor_uk&utm_term=gross-out%20feminism.

- Viala, A. 2008. La France galante: essai historique sur une catégorie culturelle, de ses origines jusqu’à la Révolution. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

- Vincendeau, G. 1995. “Gérard Depardieu: The Axiom of Contemporary French Cinema.” Screen 34 (4): 343–361.

- Vincendeau, G. 2000. Stars and Stardom in French Cinema. London: Bloomsbury.

- Wanzo, R. 2016. “Precarious-Girl Comedy: Issa Rae, Lena Dunham, and Abjection Aesthetics.” Camera Obscura 31 (2): 29.

- Warner, K. J. 2017. “In the Time of Plastic Representation.” Film Quarterly 71 (2): 32–37. https://filmquarterly.org/2017/12/04/in-the-time-of-plastic-representation/.

- Williams, L. 1991. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” Film Quarterly 44 (4): 2–13.

- Wright-Wexman, V. 1993. Creating the Couple: Love, Marriage, and Hollywood Performance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.