ABSTRACT

As place-based philanthropic institutions, community foundations have generated an inextricable linkage between community development initiatives and local funders that, when bolstered by robust data, drives innovative approaches to community needs and quantifiable improvements across community wellbeing indicators. Growing out of an innovative partnership with the Athens Area Community Foundation, the Athens Wellbeing Project applies collaborative cross-sector approaches to data collection and analysis that guide Athens-area community development initiatives. The Athens Wellbeing Project model is adaptive to changes in community needs, using the Social Determinants of Health as a framework to define dimensions of wellbeing that inform subsequent iterations of data collection. This case study discusses how the Athens Wellbeing Project’s connection to local stakeholders, development of a robust data collection tool, and partnership with a place-based philanthropic institution have led to improved quality of life in the community and the establishment of sustainable data-driven decision making in key anchor institutions.

Introduction

Sustained cross-sector stakeholder engagement and collaboration is a critical component of addressing the social determinants of health (Rural Health Information Hub, Citation2021). To achieve this, an innovative and strategic partnership was formed between the Athens Area Community Foundation (AACF) and the Athens Wellbeing Project (AWP) in 2016. This unique location-based philanthropic collaboration was created to collect meaningful local data to support community development through informed decision-making, improved service delivery, and increased community quality of life (The Athens Wellbeing Project, Citationn.d.). By design, AWP collects new data biennially (or every 3 years when the second year is a Census year) via surveys to fill gaps left by existing data sources and is used to inform and evaluate policies, assist with accreditation processes, and bolster grant proposals. It identifies community strengths, disparities, and areas for improvement. In addition to the AACF, these data are utilized by AWP institutional partners, including the local school district, unified government, police department, housing authority, major local hospitals, and the University of Georgia.

In its role as a public grantmaking institution, AACF is a trusted leader, partner, and guide for local philanthropy (Athens Area Community Foundation, Citation2021). Through engagement with nonprofits and key stakeholders, it creates a better understanding of the existing resources and needs in the community. Maintaining a data-driven approach, AACF uses AWP data to match philanthropic assets to the organizations best suited for addressing community needs. AACF funds are in turn used to financially support AWP in a symbiotic relationship, wherein financial contributions from the community foundation support the AWP’s collection and analysis of data, cycling back to inform AACF’s grantmaking across the region.

Recognizing that improving community quality of life requires a multifaceted approach, AWP focuses on five domains: health, housing, education, civic vitality, and safety. Each is singularly important while being inextricably interdependent (Martsolf et al., Citation2018). Although these domains remain consistent across survey iterations, the survey is an evolving document that adapts to meet community needs. The results of each survey inform the next iteration. By building a data set that tracks changes in key indicators of community wellbeing year upon year, the data produced in the partnership between the Athens Wellbeing Project and the Athens Area Community Foundation (AACF) provide unique insight into the ever-evolving needs of the community and create benchmarks for endeavors related to childcare, healthcare access, food security, affordable housing, and transportation, all of which inform the direction of community grantmaking.

When data inform philanthropy, it ensures that the efforts of partners lead to well-coordinated, inclusive action with enhanced and lasting impact (Gaddy & Scott, Citation2020; Greco et al., Citation2015; Greenhalgh & Montgomery, Citation2020; Ridzi, Citation2021). The innovative and strategic partnership between AACF and AWP lends itself to this and, in just 5 years, has proven itself to be an integral part of the Athens-Clarke County community. The success of this partnership highlights the importance of including local data in philanthropy and community development efforts to craft the most effective and responsive solutions to community needs (Aspen Institute, Citation2022). Moreover, this collaboration is replicable and may serve as a model for other community foundations (Ridzi, Citation2021).

Materials and Methods

In the spring of 2016, several major public institutions convened for a meeting to discuss a new collaboration. The meeting, held at the Athens Area Community Foundation, became the genesis for a partnership that would quickly become known as the Athens Wellbeing Project. These institutions were community partners that often worked together, at least tangentially, if not in direct collaboration, for delivery of service. They included the regional C ommunity F oundation and United Way, the municipal government, local hospital systems, the school district, the Housing Authority, and the University of Georgia. AWP differentiates institutions that do and do not contribute financially to the project. Those that do contribute are referred to as Institutional Partners. Those that do not are referred to as stakeholders.

These institutional partners settled on several shared challenges related to data collection, data use and data sharing, and general barriers in their own organizational capacity to collect and analyze data that then informed their mission-driven work. It was clear that while there were many existing and useful secondary data sources that they had historically relied upon (including Census and American Community Survey data, upon others), there remained significant gaps in their understanding of the local community across domains that included health, housing, community safety, education, and social capital. Concurrent to this shared recognition of data challenges and the need for more localized information in the area of human service delivery, was a shared commitment to breaking down informational barriers between these institutions and improving outcomes for the greater Athens community across a multitude of health and wellbeing outcomes for the populations served. It was decided that the AWP research team would be stewards of the data by not only collecting data but also cleaning, coding, and analyzing data, creating reports, and providing context for institutional partners and stakeholders as needed. Partners and stakeholders facilitated data collection by sending survey links via e-mail listservs, sharing calls to participate in social media streams, and allowing the research team to collect data on location and at events, constituting a convenience sample of Athenians. The team also provides presentations to partners, stakeholders, other organizations, and community members.

These data protocols were developed as a requirement for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Under the devised protocols, only de-identified data that are aggregated to sample and subsample stratifications of at least 30 responses are shared and reported publicly. Individual level household data are never shared. Data collection is conducted using an encrypted and password protected Qualtrics platform. Data are stored there and on servers at UGA that are password protected. Anyone with access to the data has received CITI training and has been listed on the IRB at UGA. Those are the only people that have access to the sample data with any identifying information. The level of analysis is household and we do not collect identity, though we do have the addresses. Those data are not shared or reported in any way.

In addition to the partners, scientists in public health, geography, and public policy from the University of Georgia were engaged. This team of scientists has been engaged with recent need assessments in the community for several stakeholders (including the hospital systems) and saw an opportunity to convene with this group of leaders and institutions to bring their scientific methods and skill sets to solving many of the issues described around data collection above. The combination of institutional representation and buy-in, shared commitments to closing gaps in understanding across domains, and the expertise of the researchers created an opportunity for the Athens Wellbeing Project to take shape under the leadership of the Community Foundation in partnership with the research team. What has resulted, and is further discussed in the Results and Discussion sections, is a representative dataset that has transformed (for the better) our community’s ability to engage in place-based philanthropy and human service delivery.

Given that the researchers and institutional stakeholders recognized the importance of capturing the overall wellbeing of the community. Aligning their vision with the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2030 Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework, which emerged as a priority (Healthy People, Citation2030, 2022). The five determinants of health are as follows: (1) economic stability, (2) education access and quality, (3) health-care access and quality, (4) neighborhood and built environment, and (5) social and community context, were modified to create AWP’s five domains of community wellbeing (Healthy People, Citation2030, 2022). These include (1) civic vitality, (2) community safety, (3) health, (4) housing, and (5) lifelong learning. There is representation from at least one organization for each of these among the AWP institutional stakeholders.

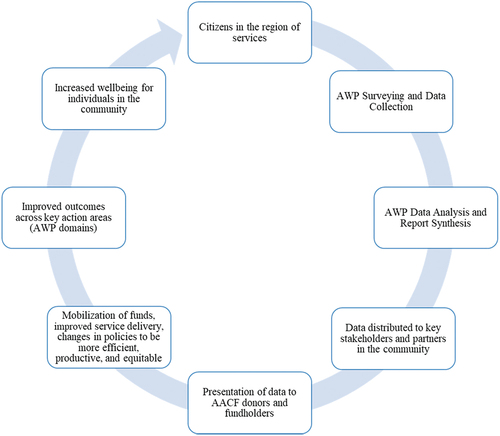

The kickoff meeting in 2016 – the beginning of the partnership and collaboration among stakeholders that is now known as the Athens Wellbeing Project – has given way to a stream of place-based work that is the bedrock of strategic philanthropy in the community of Athens, Georgia. With regard to the essential ingredients of such a sustained and rigorous collaboration, four key components are necessary: 1) Community Foundation championship; 2) financial commitment from operating budgets of stakeholders; 3) leadership buy-in across sectors; and 4) scientific rigor. The mission of AWP is “to empower the Athens community with meaningful data that will lead to more informed decision making, improvements in service delivery, and greater quality of life for citizens.” The theory of change is included in .

Figure 1. The Athens wellbeing project’s theory of change, detailing the evolution of data collect, analysis, and use.

AWP Research Team and Survey Instrument

The AWP research team is led by a Principal Investigator (PI) who specializes in policy and program evaluation, community needs assessments, and vulnerable populations. The PI serves as the convener for other researchers on the team when necessary for research and analysis planning and execution, and also connects to all institutional stakeholders that invest in the project. The Athens Area Community Foundation maintains a very close working relationship with the PI on its research team, meeting at least monthly together to share data and engage in planning for stakeholder engagement and data transparency.

In addition to the Principal Investigator, the AWP research team includes experts in survey design, geospatial data, evaluation, and sampling design. Members of this team represent, respectfully, the University of Georgia’s School of Public and International Affairs, Department of Geography, and College of Public Health, as well as independent consultants with experience in sampling design. Additionally, several graduate research assistants from the University of Georgia’s College of Public Health are engaged in the project, under the supervision of the PI. During periods of data collection, AWP also employs a project manager to oversee data collection and operations in the field.

The survey instrument was developed by the research team in conjunction with representatives from each of the institutional stakeholders. The instrument, which is estimated to take 20 min by Qualtrics’ AI function, was specifically designed to collect information not available from other secondary data sources. Where available, validated measures from other nationally representative surveys were utilized to ensure the validity and reliability, as well as to allow for comparisons between Athens-Clarke County and other locations. The full AWP 3.0 survey is presented in Appendix A. Prior iterations of the survey, as well as additional data, reports, white papers, and other items released by the Athens Wellbeing Project are available at http://www.athenswellbeingproject.org.

The survey instrument contains a section with questions from each domain, as well as a demographic section at the beginning. The most recent version, AWP 3.0, which was still in the field at the time this article was written, also includes a suite of questions about COVID-19. shows each of the five domains with their SDOH counterparts, as well as the community partners, and a selection of survey questions, the responses to which are all an integral part of the AAC mission of strategic philanthropy that is place-based.

Table 1. The five domains, plus the COVID-19 suite, and their counterparts from the social determinants of health framework, the community partners that represent them, and a sample of questions for each domain from the AWP 3.0 survey instrument.

Surveys were made available to respondents both electronically and via paper. Individuals could access the survey through a number of routes: hyperlink and URL, by sending a text to a phone number that would respond with a direct link, by requesting a paper copy of the survey, or via iPads that were made available at various times and locations around the county.

In its first two iterations, AWP employed a random sample of ACC residents stratified by the type of dwelling: single family, apartment/condominium, and mobile homes. On several occasions, feedback from community members included the question “Why don’t you want to hear from me?” In order to address this and ensure representativeness, in AWPs third iteration, all households were invited to participate in the survey in addition to the random sample. Our sampling design expert was tasked with comparing the full sample with the random sample and creating sample weights as needed to ensure representativeness. For all three iterations, a census sampling approach was utilized to ensure representation from historically excluded populations: people who are unhoused, people who are living in public housing, older adults, and Latino families. Households in the random sample were provided with a unique survey identification number (ID) via postcard. Household IDs were used to ensure no household responded more than once and that survey responses were, in fact, from households within the sample. In prior iterations, door-to-door data collection teams of University of Georgia students, led by Neighborhood Leaders, followed up with households to increase responses.

To increase community trust and buy-in, the AWP research team is working with the Athens-Clarke County Neighborhood Leaders (NLs). Neighborhood leaders are individuals who are of the community, in the community, and for the community in Athens, working alongside Family Connection, a state-wide network of partners working within local communities to improve outcomes for families and children, to better serve their neighborhoods and connect residents to resources, services, and information procured by Family Connection. The Family Connection Program, funded by the Athens-Clarke County Unified Government’s Prosperity Package, is led by Family Connection-Communities in Schools of Athens and operated as an initiative of Athens-Clarke County’s Mayor and Commission as a hyperlocal, relationships-based approach to addressing poverty, income inequality, and social inequity in the community. One individual is employed full-time as a Neighborhood Leader (NL) in each of the 16 elementary school zones, blending a community outreach approach with individual case management support for the residents of each zone. NLs primarily focus on reducing barriers to access and cultivating relationships with individuals, families, organizations, and businesses in the zones they serve. They achieve this by communicating neighborhood and county news, assisting with things, such as applying for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) enrollment, and more. They serve as representatives of the AWP, using relationships to share information about the survey and its importance for those to whom the research team is unfamiliar. NLs are deeply connected to their hyper-local community, and their support has been instrumental in AWP’s data collection success.

Using a mixed methods approach, AWP collects both qualitative and quantitative data. Once the data were collected, they were cleaned and coded for analysis. Sample weights were created by the research team to increase the representativeness of the sample. In AWP 2.0, the resulting sample had a margin of error of ±3%. Additional variables for the analysis were created (e.g. a poverty measure using income and household size). Summary statistics were estimated for all variables in the sample, for the full sample and for sub categorizations. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to further understand the findings.

The data presented were descriptive in nature. Measures were presented for the full sample and by subcategorization for comparison purposes. AWP data are meant to be used in conjunction with other existing data sources (primary, secondary, quantitative, or qualitative) in order to get the most comprehensive and robust understanding possible of outcomes of interest and general levels of wellbeing in the Athens-Clarke community. Where possible, data visualizations were used for ease of interpretation. The goal of the research team was to create ease in accessibility and to leverage the data to create information so that it would then turn the information into knowledge useful to stakeholders and community members. Full tables of descriptive statistics were made available in an online appendix and upon request. The Social Mapping Atlas was also created using secondary data and is available through the Athens Wellbeing Project website, a tool that allows users to layer data at the elementary school zone level (Community Mapping Lab, Citation2020).

In addition to its primary data collection and analyses, the Athens Wellbeing Project integrates data from secondary sources and websites into its analyses, allowing for more robust reporting. For example, utilization of the Athens Clarke County Homeless Point in Time Count provided an integral perspective to supplement the housing domain. The research team used the Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning site to identify Quality Rated (QR) child care centers and called each center to understand QR child care availability. Additionally, data from another AWP project, the Behavioral Health Community Needs Assessment, were used to report how many behavioral health providers were offering medication assisted treatment (Bagwell-Adams et al., Citation2021).

Results

Currently, in its third iteration, the Athens Wellbeing Project is thriving in the Athens-Clarke County Community (Athens Wellbeing Project, Citationn.d.). AWP 1.0 (2016) garnered 1,354 responses, 2.0 (2018) received 1,078 responses, and 3.0 (2021) received 3997 household responses with margins of error of 3%, 3%, and 2%, respectively. AWP data have been used in dozens of white papers, technical reports, posters, and presentations. Institutional partners as well as several community stakeholders and leaders have utilized the data and continue to do so. AWP’s partners have designated funds for AWP into their yearly operational expenses, creating a continuous and recurring pool of funds independent from grants. This creates a commitment to AWP’s institutionalization in the Athens Community. Combined with the addition of new institutional partners, like Athens’ two major hospitals following the first iteration, this system creates a strong and sustainable baseline of support for the project, creating a long-term resource for the community.

When the Clarke County School District was planning to open a community-based health clinic, AWP data informed their decision about its location. This partnership with the school district and the partnerships created with the other institutional partners are unique in the sustained engagement across AWP iterations. When the Cancer Foundation of Northeast Georgia evaluated its ability to help families of those living through cancer, AWP data showed that the amount the Foundation had previously provided was not adequate and the disbursement amount increased (The Cancer Foundation of Northeast Georgia, Citationn.d.). When the COVID-19 pandemic began, members of the AWP research team presented data to the Mayor and Commission and School District regarding how families with children might be impacted by school and childcare closures (Michaux, Citation2022). To access these data, the Unified Government, alongside area nonprofits, was able to quickly mobilize efforts to improve access to food, reduce barriers to access public transportation, and better understand the imminent needs of families with children.

More recently, AWP data were readily available in a time of crisis, allowing decision-makers to understand the immediate landscape in a way that other, larger data sources, such as the US census, were unable to. For example, in the 2018–2019 data collection period (n = 1078), AWP data showed that 30% (n = 323) of Athenian households report working more than 40 h per week; 50% (n = 539) have no paid sick leave, paid vacation time, or family leave; and 73% (n = 786) have trouble when trying to take time off work to take care of personal or family matters. Further, 33% of the households (n = 355) sometimes or often could not afford a balanced meal (100% of the students in the Clarke County School District are eligible to receive free breakfast and lunch) and 75% (n = 808) worry about how they would pay for an unexpected medical bill (Athens Wellbeing Project, Citationn.d.). All this information was critical for community leaders to understand the repercussions of actions taken to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and allowed them to proactively mitigate issues to the best of their ability.

Creature Comforts, a local brewery that has prioritized philanthropy as a part of their corporate philosophy, has used AWP data in its two most recent iterations of the Get Comfortable campaign (Creature Comforts, Citationn.d.). This endeavor supports local nonprofit organizations’ work and is, at the time this article was written, focusing on improving third-grade literacy among Athens-Clarke County youth. AWP data have also been used for strategic planning and grant applications for organizations, such as Books for Keeps, Athens Community Council on Aging, Athens Eats Together, and the Foodbank of Northeast Georgia.

In 2019, the Athens Area Community Foundation hosted the Georgia Grantmakers Alliance in Athens for a place-based tour of philanthropic endeavors in the community. The tour showcased various organizations and opportunities for philanthropic partnerships across the Athens community, most notably highlighting the Athens Wellbeing Project’s collection and utilization of representative local data. While it was the Athens Area Community Foundation’s established history of place-based philanthropy that drew initial interest to the region, the addition of the Athens Wellbeing Project’s data collection and utilization function helped to present Athens as a city primed for further investments in the place-based philanthropic landscape. Following this meeting, the Pittulloch Foundation, a private foundation based out of Atlanta, approached the Athens Area Community Foundation with the concept of Resilient Georgia, a statewide organization recruiting pilot regions for participation in a two-year trauma-informed care grant with the goal of aligning public and private efforts and resources to support resiliency initiatives for a 0–26 audience (Resilient Georgia, Citation2022). The pilot program, which was applied for and secured in the fall of 2019 using key data from the Athens Wellbeing Project’s survey, led to continued collaboration between the Athens Area Community Foundation and the Athens Wellbeing Project as key partners on the grant. This partnership led to the creation of regional resources, a Behavioral Health Community Needs Assessment (BHCNA), and various training offerings that have occurred throughout the region under the purview of this grant. Notably, the BHCNA, which was designed and implemented by the AWP, provided an inventory of local behavioral health providers that yielded key insights into the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the behavioral health sector and brought about data-driven funding to several local providers (Bagwell-Adams et al., Citation2021). This grant is another example of the collective impact that can be derived from the partnership of data and philanthropy. Since the initial two-year pilot was granted in 2019, the coalition, now known as Resilient Northeast Georgia, has secured additional two years of funding for trauma-informed capacity building, garnering $600,000 in funding for trauma-informed initiatives in the region over a four-year period (Resilient Northeast Georgia, Citation2022). The success of the AACF-AWP partnership as key conveners in this grant opportunity has led to the expansion of the region of service from the original six counties to twelve counties. Following the first iteration, AWP data were used to enumerate the coalition’s impact on the region, providing objective measures of success that helped secure the extended funding.

Discussion

The benefits of the partnership between the Athens Wellbeing Project and the Athens Area Community Foundation are numerous. The community foundation works in tandem with AWP to accomplish its philanthropic aims; AWP is made possible in turn by the championship and leadership of AACF. AWP provides AACF with data and information that bolsters the foundation’s ability to achieve its mission and infuse strategy into the millions of dollars of funding that are allocated to local nonprofits each year. Implementing this data-driven approach to philanthropy connects the community foundation’s assets to high-priority areas of need in a community, leading to the mobilization of resources toward ultimately improving outcomes across the five AWP domains.

All of this lends itself to fulfilling the AWP Theory of Change, illustrated in . As shown in the Materials and Methods section above, this Theory of Change begins with a cache of representative, household level data, sourced directly from citizens in the community across the five domains (Athens Wellbeing Project, Citationn.d.), which are developed into outputs that may serve as a guide for the AACF’s local philanthropy, directing its leadership across the community and driving its partnerships with local organizations. This is achieved through local, representative data sets that assess gaps in services, needs in the community, and policies that help or hinder efforts to address these needs. The Athens Area Community Foundation has used AWP data to guide the direction of philanthropic initiatives (Athens Area Community Foundation, Citation2021). The information collected by the Athens Wellbeing Project is transformed and tailored to the needs and interests of AACF’s donors and fundholders who are seeking direction for their giving, providing an individualized, data-driven approach to local philanthropy. From there, funds are allocated and mobilized toward the areas of greatest need and potential for growth in the community. These efforts make the delivery of services through community organizations more equitable, efficient, and effective.

The goal of these efforts is to cultivate improved outcomes in the community across many areas of household life. The AWP-AACF partnership is designed to facilitate a focus on the overall wellbeing of the community by leveraging the expertise and science of AWP research into the funding arm of the community foundation. In effect, this is local, place-based philanthropy at its core. The data are representative information from a representative snapshot of the community, with great care taken to understand and represent the most vulnerable populations in Athens-Clarke County. AWP 3.0 built on the data collected in the first two iterations, maintaining the random sample of single family homes, condo and apartment units, mobile homes, as well as the census sampling of special populations within the catchment area. A key change in AWP’s third iteration was the expansion of survey inclusion to all residents of Athens Clarke County. Thus, through a mixed-methods approach that combined random sampling, convenience sampling, and the Census as a secondary data source, the survey was able to derive a complex, representative dataset reflective of the intricacies and intersectionality of the population measured. Data-driven philanthropy is only as useful as the quality of information used to drive decision making, so the confidence that philanthropic entities have in the information they use must be well placed. Over time, through the first three iterations and beyond, a longitudinal snapshot of wellbeing will be leveraged to understand changes in community health and other outcomes. The commitment to a partnership that is sustainable over many iterations is critical to facilitate an in-depth understanding of wellbeing over time.

COVID-19: Opportunities for AWP to assist community pandemic responsiveness

As an independent data-gathering entity that is championed by but not guided by AACF, AWP was able to inform rapid, data-driven action in a timely manner when COVID-19 struck in early 2020. In this capacity, AWP procured data that allowed AACF to quickly and effectively mobilize resources toward needs that are determined from the community (Ridzi, Citation2021).

Pivoting during the COVID-19 pandemic to adjust to changes in the philanthropic and social landscape, the Athens Wellbeing Project and the Athens Area Community Foundation commissioned the Behavioral Health Community Needs Assessment (BHCNA), which was conducted using funds from the partners’ trauma-informed care grant (Resilient Northeast Georgia, Citation2022). The BHCNA provided real-time data from behavioral health providers on the effects of the pandemic on supply chain issues, service barriers, and the psychological effects of isolation and fear on both clients and staff (Bagwell-Adams et al., Citation2021). This report produced timely and relevant data on the needs and experiences of behavioral health-care staff and highlighted the importance of community data as a tool for leaders and decision makers contending with the effects of lockdowns, supply shortages, and the behavioral health crisis (Ridzi, Citation2021). Having this information readily available expedited local grantmaking, informing AACF of the needs of local providers and leading to a series of microgrants to support telehealth utilization and staff training (Resilient Northeast Georgia, Citation2022).

The relationship between AWP and AACF has produced sustainable cross-sector partnerships between mental and primary health providers and community leaders, research institutions, and local businesses, leading to collaborative efforts rooted across anchor institutions (Martsolf et al., Citation2018). This allows the AACF-AWP dyad to react swiftly and appropriately to needs in the community, tethering the collective impact achieved through the behavioral health grant to strong leadership where trust exists between institutional leaders and with the community at large. The mutually beneficial relationship between AACF and AWP can demonstrate to other communities how local data drive action, providing a model for response tested during the COVID-19 pandemic and proven successful in addressing the needs of the community.

Barriers and Challenges

While other communities have faced similar problems in collecting and utilizing data to guide decisions, the unique combination of factors present in the Athens community has produced a series of unique challenges to the project (Fehler-Cabral et al., Citation2016; Greenhalgh & Montgomery, Citation2020; Jones, Citation2021; Squire, Citation2021). AWP has experienced barriers that exist due to community dynamics, including but not limited to an oversaturation of nonprofit organizations, high rates of intergenerational poverty, engagement fatigue, financial uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic, confidentiality concerns surrounding the collection and analysis of data, and a model built around an inherently complex concept that can be difficult to explain and quantify to stakeholders and funders. Despite best efforts to remain apolitical, some topics and questions are inherently tied to local, state, and national issues. Both the social and political landscapes may impact responses (Greene, Citation2021).

Although the project is local in nature, national and state issues and landscape affect its ability to collect data and influence local outcomes (Mack et al., Citation2014). Locally, there has been a great deal of turnover in leadership, including five police chiefs, three housing directors, two mayors, five assistant city managers, and three superintendents. The return on investment for institutional stakeholders is less tangible, such that much of what the survey measures are the indirect results of programs and policies. Therefore, changes in leadership are an ongoing barrier, impacting all aspects from buy-in and trust, to support and data utilization (Wu, Citation2021). With incoming leaders, it is imperative to the longevity of AWP in its current capacity to communicate the importance of the project as a function of strategic philanthropy and community outreach; conveying this understanding supports the continuous and consistent levels of institutional buy-in among key stakeholders, despite changes in leadership.

A related challenge is the work required to please a number of strong and distinct stakeholders (Smarick, Citation2021). Forming the survey to do what organizations need it to do takes a great deal of time and finesse. Being associated with the University of Georgia also evokes the ongoing town-gown dynamic between the University and residents and organizations, emphasizing the tensions that exist between universities and the communities in which they function (Smarick, Citation2021). Building trust and rapport has been a critical component of AWP’s ability to be successful in this setting, as strong community relationships can help offset some of this tension (Mack et al., Citation2014).

While the barriers outlined in this case study are not resolved to completion by the efforts put forth by this collaboration, the progress made toward long-term systemic change is noteworthy to discuss in the context of the partnership’s ongoing initiatives. The nature of place-based philanthropic work requires analysis of the barriers and challenges as a core element of strategic planning in the ongoing efforts of this philanthropic partnership, without which the process may become ill-suited for addressing specific local needs. When devising the protocols for conducting, analyzing, and disseminating the findings from the AWP data, an intimate knowledge of the barriers to uptake and use of the data must be accounted for in the planning process to minimize misuse and retain the community trust and rapport that is central to the success of this partnership. This involves leveraging the Athens Area Community Foundation’s role as a trusted leader, partner, and guide for local philanthropy alongside Athens Wellbeing Project’s data-driven understanding of community trends to predict and resolve relational challenges and barriers to action that may arise during the process. The resulting data utilization practices and outcomes are therefore more competent in effecting meaningful local change that is tailored to the community and primed for greater impact. Although this partnership cannot monolithically resolve barriers like town-gown tensions, policy and leadership challenges, or the unique place-based obstacles that are at play locally as a result of existing systemic factors, the intentionality of the planning process and the nature of the AACF-AWP partnership is making strides in bringing awareness to these issues and better equipping local stakeholders and decision-makers to take data-driven action toward more sustainable resolution of these issues.

Limitations

The Athens Wellbeing Project is in its sixth year and third survey iteration. Its relative newness is a limitation, as brand recognition and community member buy-in is still in progress. It is often difficult to show causality because the sample population is different between each iteration and, therefore, many of the causal criteria are unable to be met. Though most of the questions have remained the same, there have been slight changes and refinements made over the years; questions that are new or altered are more difficult to assess longitudinally. As with many things nowadays, changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic have vastly changed the way AWP is implemented, presenting new and unexpected challenges. Confidentiality is a common concern among respondents. Data are aggregated in such a way that no responses can be associated with a specific household.

It is important to note that although the research team views AWP data as a community good, there is potential for data misuse. When data are presented or applied improperly (e.g. partially or out of context) they can be harmful. In order to deter potential misuse, like use for redlining or for the creation of harmful policy, the AWP research team stewards usage of the data within the community.

Conclusion

The partnership forged between the Athens Area Community Foundation and the Athens Wellbeing Project creates a unique setting in which place-based philanthropy and local data can intermingle. This intersection guides community development initiatives in a dynamic and innovative direction, allowing for real-time adaptation to the ever-changing needs of the community. In this model, local data-driven solutions are leveraged in response to local problems, allowing for a nimble community response drawing from existing resources. The Athens Wellbeing Project collects and analyzes local data across its predetermined domains, covering gaps in data collection usually underrepresented by larger data collection programs and yielding data that uniquely capture life and wellbeing in the Athens community.

In a complimentary role, the Athens Area Community Foundation serves as an apolitical entity that reflects the interests of the community in which it operates and in doing so, acts as a trusted community leader, partner for nonprofits, and guide for philanthropy. Utilizing the data collected and analyzed by the Athens Wellbeing Project, the community foundation uses data on community needs to inform grantmaking and advise donors within the community, cyclically leading to improvements to wellbeing that can be captured in subsequent iterations of the Athens Wellbeing Project.

In other communities with established philanthropic institutions, we believe this model to be highly adaptable and replicable. The trust and relationships built by community foundations are amenable to the needs of robust local data programs, as they provide linkage to partner institutions, funding opportunities from local donors and the specific knowledge of the community necessary for initial strategic planning. The return on investment from funding and supporting a local data project is indispensable for communities involved in place-based philanthropy, providing evidence-based direction for future endeavors and honing the institution’s ability to address needs in the community with efficacy.

Acknowledgements

The Athens Wellbeing Project is made possible and funded by the Athens Area Community Foundation, Athens-Clarke County Unified Government, the Athens-Clarke County Police Department, Clarke County School District, St. Mary’s Health Care System, Piedmont Athens Regional Medical Center, the Athens Housing Authority, and the University of Georgia. The Athens Wellbeing Project also received strategic support from community stakeholders, Family Connection-Communities in Schools of Athens, Envision Athens, and the United Way of Northeast Georgia. The authors also acknowledge The University of Georgia College of Public Health and the UGA Vice President’s Office for Public Service and Outreach (Dr. Jennifer Frum), the Athens Wellbeing Research Team (Dr. Jerry Shannon, GIS Mapping, UGA Department of Geography; Dr. Amanda Abraham, Survey Instrument Design, UGA School of Public and International Affairs), the AWP Intern Team (George Alexander, Ji Hyun Bae, Rebecca Baskam, Kaitlyn Catapano, Philip Elliott, Aria Kumar, Riddhi Patel, Tanaya Sanikapally), AWP’s consultants (Celia Eicheldinger, Sampling Design Expert; Jacob Lambeck, MPA, AWP 3.0 Project Manager), and the Family Connection-Communities in Schools’ Neighborhood Leaders. Additional support was provided by the Athens Area Community Foundation’s staff and board (including significant leadership from past board member Ed Perkins, Strategic Philanthropy Chair). Lastly, the authors acknowledge Resilient Georgia for their funding support and their commitment to building a more resilient state of Georgia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aspen Institute. (2022). Community development philanthropy. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/programs/community-strategies-group/community-development-philanthropy/

- Athens Area Community Foundation. (2021). Athens Area Community Foundation homepage. athensareacf.org

- Athens Wellbeing Project. (n.d.). The Athens Wellbeing Project homepage. http://www.athenswellbeingproject.org/

- Bagwell-Adams, G., Bramlett, M., Lambeck, M. P. H., MPA, J., Huang, H., & Lysaught, M. (2021). Behavioral health community needs assessment. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57b5f410bebafb4c9d9065d0/t/60a506c6884aac7377fad8f8/1621427912123/AWP_BHCNA_4.14.21.pdf

- The Cancer Foundation of Northeast Georgia. (n.d.). Homepage. http://www.cancerfoundationofnega.org/

- Community Mapping Lab. (2020). Athens Social Atlas. https://comapuga.shinyapps.io/AthensSocialAtlas/

- Creature Comforts. (n.d.). Get comfortable. https://getcurious.com/get-comfortable/.

- Fehler-Cabral, G., James, J., Long, M., & Preskill, H. (2016). The art and science of place-based philanthropy: Themes from a national convening [Article]. The Foundation Review, 8(2), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1300

- Gaddy, M., & Scott, K. (2020). Principles for advancing equitable data practice. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/principles-advancing-equitable-data-practice

- Greco, L., Grieve, M., & Goldstein, I. (2015). Investing in community change: An evaluation of a decade of data-driven grantmaking [Article]. The Foundation Review, 7(3), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1254

- Greene, J. P. (2021). Navigating the financial, political, and information constraints on large-scale philanthropy. Getting Place-Based Philanthropy Right, Issue. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/navigating-the-financial-political-and-information-constraints-on-large-scale-philanthropy/

- Greenhalgh, C., & Montgomery, P. (2020). A systematic review of the barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by philanthropists when determining which charities (including health charities or programmes) to fund [article]. Systematic Reviews, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01448-w

- Healthy People 2030. (2022). Social Determinants of Health. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Jones, J. (2021). Philanthropic support for a research-practice partnership. The Future of Children, 31(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2021.0006

- Mack, K. P., Preskill, H., Keddy, J., & Jhawar, M.-M. K. (2014). Redefining expectations for place-based philanthropy [Article]. The Foundation Review, 6(4), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1224

- Martsolf, G. R., Sloan, J., Villarruel, A., Mason, D., & Sullivan, C. (2018). Promoting a culture of health through cross-sector collaborations. Health Promotion Practice, 19(5), 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839918772284

- Michaux, S. (2022). Data for the people: Athens Wellbeing Project helps pinpoint areas of civic concern. https://research.uga.edu/news/data-for-the-people-athens-wellbeing-project-helps-pinpoint-areas-of-civic-concern/.

- Resilient Georgia. (2022). Resilient Georgia homepage. https://www.resilientga.org/

- Resilient Northeast Georgia, M. (2022). Resilient Northeast Georgia homepage. resilientnortheastgeorgia.org

- Ridzi, F. (2021). Place-based philanthropy and measuring community well being in the age of COVID-19. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 5(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-021-00124-8

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2021). Developing cross-sector partnerships to address social determinants of health. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/sdoh/4/cross-sector-partnerships

- Smarick, A. (2021). A humble approach to place-based urban education philanthropy: Empowering individuals, associations, and local government entities to lead incremental, sustainable change in their communities. Getting Place-Based Philanthropy Right, Issue. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/a-humble-approach-to-place-based-urban-education-philanthropy-empowering-individuals-associations-and-local-government-entities-to-lead-incremental-sustainable-change-in-their-communities/

- Squire, J. (2021). Five lessons for successful place-based philanthropy in rural communities. Getting Place-Based Philanthropy Right, Issue. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=edshol&AN=edshol.hein.amenin.aeiadsz0001.2&site=eds-live&custid=uga1

- Wu, V. C.-S. (2021). The geography and disparities of community philanthropy: A community assessment model of needs, resources, and ecological environment [Report]. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 32(2), 351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00180-x