ABSTRACT

Though the concept of place-based philanthropy is common parlance in community development scholarship and practice, there is still uncertainty around its meaning due to the multidisciplinary nature of its study and definitional variation among and between scholars and practitioners. This article presents findings from a recently edited volume created by a binational research team. Ten cases of philanthropic initiatives were explored to develop a transnational understanding of foundation engagement in place-based philanthropy. Place-based philanthropy was explored by considering collaboration with other stakeholders, initiative evaluation, systems change efforts, and issues of power, equity, and justice. Our findings suggest that place-based philanthropy among foundations is heterogeneous. While some foundations adhere to traditional forms of place-based philanthropy, others are pushing the boundaries of this type of work. This article urges both academics and practitioners to reimagine place-based philanthropy for transformative purposes.

Introduction: A new look at place-based philanthropy

According to Manuel Castells, “the most fundamental contradiction in our globalized, urbanized, networked world” is that “in a world constructed around the logic of the space of flows, people make their living in the space of places” (Castells, Citation2010, p. xxix). Place still matters. This claim is supported by the continued emphasis on place by philanthropic foundations in their community development efforts. Though North American place-based philanthropy can be traced back to the Ford Foundation’s Gray Areas project in the 1960s, place became a cornerstone of philanthropic community development with Comprehensive Community Initiatives in the 1990s (Martinez-Cosio & Rabinowitz Bussell, Citation2013; Pill, Citation2019). And yet, the multidisciplinary nature of academic studies and conceptual variation among and between practitioners and scholars has created a field riddled with multiple typologies and definitions of “the philanthropy of place” (Pill, Citation2019).

Driven by the hypothesis that place is a significant unit of analysis in North American contexts and place-based philanthropy presents a unique force in local development, we explored ten cases from Canada and the US. These cases highlighted potentially innovative philanthropic approaches to analytically and practically mobilizing place for social justice and environmental stewardship. The goal of this study was less about contrasting unique national place-based approaches, and more about mining cases for transnational learning and mutual knowledge of place-based philanthropy. The following five questions guided research and analysis of the case studies: 1) How do foundations understand place-based work, and how does this influence the scale of their work? 2) What kind of collaboration occurs in place-based initiatives and is it unique in the context of community development? 3) How do foundations assess the impact of their place-based approaches? 4) How do foundations advance equity or social justice through place-based work? and 5) What is innovative about the operation of place-based foundations and how do they shape their field or change systems?

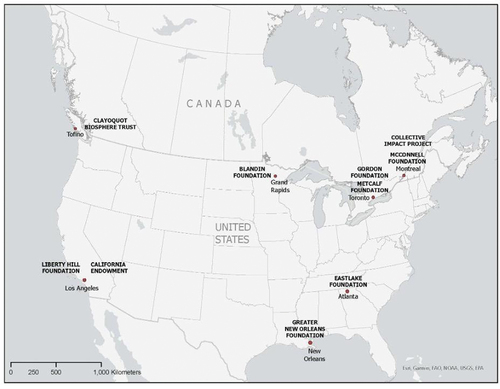

Through these questions we uncovered foundations’ understandings of their role(s) as community development stakeholders and their views on the importance of place to those efforts. While other stakeholder voices – residents, public officials, and smaller nonprofits – were absent from our analysis, our focus on foundations allowed a more robust understanding of place-based initiatives from the perspective of organizations that are highly influential in the design, implementation, and evaluation of this work. We chose ten such cases—five in each country – which included a mix of geographic locations and foundation types. These foundations discussed include Centraide of Greater Montreal, Clayoquot Biosphere Trust, Gordon Foundation, McConnell Foundation, and Metcalf Foundation from Canada and Blandin Foundation, East Lake Foundation, Greater New Orleans Foundation, Liberty Hill Foundation, and the California Endowment from the US.

In the following sections, we outline our methodology and findings to contribute to a deeper, more nuanced conception of place-based philanthropy. To provide context, we begin with an outline of academic and practice-oriented literature on place-based philanthropy from Canada and the US. This is followed by a discussion of our research methodology and presentation of the findings from our analysis of the ten case studies. We conclude with broader lessons learned on the importance of place-based philanthropy in Canadian and US contexts.

Review of the literature on place and place-based philanthropy

The Canadian and US literature on place-based philanthropy is largely practice-oriented gray literature written about specific initiatives. This group of literature presents recommendations for current and future community development efforts. A smaller body of peer-reviewed academic literature critically analyzes the role of philanthropic foundations within broader place-based efforts. The review that follows in this paper draws on both sets of literature to understand why place is an important concept in philanthropic community development, what constitutes forms of place-based philanthropy, and how foundations engage with contemporary issues in place-based intervention such as environmental sustainability, urban innovation, and power, equity, and justice.

Why place?

Place has recently taken on renewed importance with the reshaping of public sector roles, reductions in publicly funded and provided services and development, and the emergence of new forms of governance such as public-private partnerships (Perry & Mazany, Citation2014). Local neighborhoods have increasingly become spaces for experimentation with innovative practices in revitalization and bottom-up approaches (Phillips et al., Citation2011). Place-based approaches have been used to address previous failures of policy and interventions to address the issues of historically underserved groups. Place-based work is also utilized to confront contemporary issues of uneven development and episodic austerity on the part of state, province, and federal governments. Finally, place-based strategies are driven by the realization that social and economic inequalities are concentrated in places and an awareness that inequalities require holistic approaches to address complex and compounding issues (Institute for Voluntary Action Research, Citation2015; Oosterlynck et al., Citation2013; Phillips & Scaife, Citation2017).

Place-based efforts typically focus on the work of development in a geographic area small enough to create relevant and productive social, economic, and cultural ties, and allow stakeholders to take advantage of community-based assets and relationships (Markey, Citation2010; Theodos, Citation2021). Though place is geographically rooted, it is not solely spatial. In philanthropic initiatives, place is defined in one of three overlapping ways. The term place can describe a location defined by its disparities, in which foundation support is concentrated. Place can also be a social locale where foundations build relationships and form networks. Finally, place can refer to a locus of identity and belonging where foundations are driven by loyalty or responsibility to other stakeholders (Williamson et al., Citation2021). Place can also be understood as part of a system or ecology of collaboration (Institute for Voluntary Action Research, Citation2015) or a location where innovation is tested (Davies, Citation2017).

Community foundations and other public charities – such as public foundations or United Ways – are more likely than other foundations to utilize place-based approaches (Colinvaux, Citation2018; Davies, Citation2017; Harrow et al., Citation2016; Phillips, Citation2018; Pill, Citation2019; Waldrip et al., Citation2022).Footnote1 Community foundations and United Ways differ from other foundations – such as private, corporate, and family – in their service to a specific geographic location, receipt of donations from multiple donors, and the requirement to meet the public support test (Carman, Citation2001). These two types of embedded foundations seek to build relationships and pool resources with residents while leading broader stakeholder conversations (Allen-Meares et al., Citation2011). This requires them to fill multiple roles in community development including mobilizer, facilitator, collaborator, convener, and agenda-setter (Azevedo et al., Citation2022; Waldrip et al., Citation2022). These organizations are more intimately familiar with community needs, have deeper local networks, and exhibit more credibility and trust. These traits allowed them to more quickly respond to the COVID-19 pandemic (Azevedo et al., Citation2022). However, it should be noted that some community foundations prioritize growing endowments and fostering relationships with donors over taking strong leadership roles in underserved communities (Millesen & Martin, Citation2014; Phillips, Citation2018).

Other types of foundations also engage in place-based work. Private family foundations are deeply connected to communities and prefer place-based engagement (Boris et al., Citation2015; Born, Citation2020). National private foundations became involved in place-based philanthropy during the Civil Rights era of the mid-twentieth century through efforts in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods (Ferris & Hopkins, Citation2015b). However, this focus among national foundations has stagnated due to the time requirements and complexity of place-based work (R. J. Reid et al., Citation2022) and their top-down approach does not readily lend itself to authentic community engagement (R. J. Reid et al., Citation2020). Despite this, some national funders have transitioned to use of donor-advised funds to give local funders increased control (Colinvaux, Citation2018).

Therefore, place-based approaches appear to be based more on internal and external conditions instead of foundation type (Taylor & Buckly, Citation2017). Place-based strategies might be chosen based on the foundation’s view of their role among other stakeholders in the policy or discursive context of their region (Phillips & Scaife, Citation2017; Taylor & Buckly, Citation2017) or the foundation’s endowment size and lifecycle stage (Graddy & Morgan, Citation2006; Phillips, Citation2018; Phillips et al., Citation2011). Place-based work can also be enacted due to the economic and political issues, assets, and challenges in the targeted place (Burns & Brown, Citation2012; Institute for Voluntary Action Research, Citation2015; Karlström et al., Citation2007; Phillips et al., Citation2011) or the existence of funding networks in a locality that provide for effective partnerships (Burns & Brown, Citation2012; Fehler-Cabral et al., Citation2016; Mack et al., Citation2014).

Traditional place-based philanthropy

The term place-based philanthropy categorizes a broad range of foundation efforts in community development (Martinez-Cosio & Rabinowitz Bussell, Citation2013), but some claim it should refer specifically to holistic, collaborative initiatives for systems change (Murdoch, Citation2007). Others argue that place-based philanthropy is characterized by long-term approaches to relationship and capacity building (Karlström et al., Citation2007), or active engagement with residents (Fehler-Cabral et al., Citation2016). Traditional definitions are unified in their focus on long-term engagement with historically underserved communities.

Most scholars agree that traditional North American place-based philanthropy began with the Ford Foundation’s Gray Areas program in the 1960s, which created community agencies to increase participation of residents in initiatives in underserved neighborhoods. Activism from residents led to the end of many of the federally funded Community Action Agencies and engendered a shift to establishing community development corporations (CDCs)Footnote2 to attract capital, investors, and middle-class residents to urban communities (Melish, Citation2010; Pill, Citation2019). Though this history is associated with place-based philanthropy, Comprehensive Community Initiatives (CCIs) of the 1990s are most representative of foundation engagement with place. CCIs are holistic approaches to community and systems change that address multiple issues of low-income neighborhoods while engaging community residents (Kubisch et al., Citation2010; Martinez-Cosio & Rabinowitz Bussell, Citation2013). CCIs have continued into the present, receiving $5.9 billion in funding in 2015 alone (Thomson, Citation2021). In Canada, this type of philanthropic work has not fully established itself, though a significant example is the Vibrant Communities initiativeFootnote3 supported by the McConnell Foundation (Cabaj, Citation2011; Gamble, Citation2010).

New typologies of place-based philanthropy

Multiple typologies have emerged to define and describe place-based philanthropy. Taylor and Buckly (Citation2017) developed a three-pronged typology to understand the endemic poverty that directs place-based work. Place-based philanthropy can be guided by the idea that disadvantage is focused in places and change requires development and capacity building. Alternatively, place-based philanthropy sometimes understands poverty as an outcome of systems failures and envisions change through resident empowerment and participation in initiatives. Lastly, place-based philanthropy might view inequalities as structural concerns that should be addressed through economic and built environment revitalization. Another typology described place-based initiatives as one of three forms. Place-based work can be host-led initiatives that have a short-term focus on a single geographic area. Furthermore, they might manifest as embedded philanthropy where local foundations engage in long-term work with neighborhoods to overcome power dynamics. The most radical form of place-based work are community wealth-building initiatives that utilize anchor institutions to enact transformative change in local economic systems (Pill, Citation2019).

Place-based philanthropic community development has faced criticism. For instance, a 2010 review of 48 sites in the US found that many initiatives succeeded in providing resources, altering the built environment, and developing capacity, but they did not significantly improve neighborhood outcomes (Kubisch et al., Citation2010). Critiques such as these have catalyzed studies focused on improving place-based initiative theory and design (Burns & Brown, Citation2012; Siegel et al., Citation2015) and increased calls for better field knowledge and longitudinal data to fully understand initiative outcomes (Kelly et al., Citation2019; Theodos, Citation2021).

Some scholars criticize the hyper-localism of place-based philanthropy, claiming that community development must align with metropolitan, regional, or national goals and policies on housing and economic development (Dewar, Citation2010; Ferris & Hopkins, Citation2015a; Hopkins, Citation2015; Taylor & Buckly, Citation2017). This realignment could create cohesion between different scales of policymaking and practice. Alternatively, alignment with regional or national goals could benefit local stakeholders through access to resources and influence for systems or policy change (Hopkins, Citation2015). Foundations have responded by shifting place-based efforts toward promotion of more equitable regional economic growth that provides greater control and better quality of life to residents (Markley et al., Citation2016).

Place-based philanthropy and contemporary issues

Place-based philanthropy and environmental sustainability

Place-based philanthropy has expanded beyond traditional definitions in other ways (Fehler-Cabral et al., Citation2016; Kerman & Miller, Citation2022). Place-based philanthropy is beginning to address environmental sustainability to support climate mitigation and adaptation efforts in urban areas (Colting-Stol, Citation2020), in front-line communities (Alongi & Tilghman, Citation2021), and for Indigenous land rights and land management strategies (Dunsky Energy Consulting, Citation2020). This trend is better documented in Canada. A report from 2013 identified several Canadian foundations experimenting with pilot programs, social enterprise alternatives, cross-sector coalitions, and support for research, education, and advocacy to address issues related to planning, food systems, active and public transportation, redesign of public spaces, management of urban growth and greenspace, and climate change mitigation (Tomalty, Citation2013). The report concluded that issues of impact and scalability persist similar to traditional place-based philanthropic efforts.

Place-based philanthropy and urban innovation

Another trend emerging in place-based philanthropy is urban innovation. Through cross-sector partnerships, these new forms of governance are said to provide services and development more effectively than government (Oosterlynck et al., Citation2013) and with greater public participation (Cattacin & Zimmer, Citation2016; Rizzo & Deserti, Citation2017). Urban innovation focuses on physical space through the concepts of civic commons (Evergreen, Citation2017; Horwitz & Woolner, Citation2016) and placemaking (Silberberg & Lorah, Citation2013) to signify community stewardship of places, social inclusion, and accessibility to public space and governance. These initiatives have become common in both Canada and the US, though the most notable examples – Reimagining the Civic CommonsFootnote4 (Gaynair et al., Citation2020) and the Bass Center for Transformative PlacemakingFootnote5 (Brookings Institution, Citationn.d.) – are from the latter. Whereas many foundations focus efforts on urban places, very few invest in rural place-based philanthropy. Rural communities have unique needs and suffer significant challenges such as economic restructuring and population decline. Though foundations have largely been absent from rural places, these communities could benefit significantly from philanthropic support (B. Reid et al., Citation2022; R. J. Reid et al., Citation2020).

Place-based philanthropy and power, equity, and justice

Power, equity, and justice have become prominent issues in place-based philanthropy over the last decade as residents from underserved communities have demanded recognition (Ferris & Hopkins, Citation2015b; Squires et al., Citation2022) in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement (Kraeger, Citation2022). Foundations themselves have faced increased criticism because of their alignment with private sector interests and a market-based focus (Kraeger & Robichau, Citation2017). Scholars likewise critique the lack of accountability to residents and public officials among foundations (Seibert, Citation2019). Place-based philanthropic initiatives have also raised questions about foundation paternalism in initiative goal setting and design (Thomson, Citation2021). Critiques of foundation transparency and accountability have shed new light on lack of sustained engagement or participation with residents in philanthropic-supported development (Kraeger & Robichau, Citation2017; Seibert, Citation2019) and some critics have called for foundations to move beyond grantmaking to share power through deliberation and co-creation of funding priorities and decisions (Kraeger, Citation2022; National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Citation2020).

Some place-based foundations have recognized that attention to resident engagement in community organizing, political constituency building, and leadership development not only increases resident influence, but also creates more relevant, accountable, and sustainable initiatives (Ferris & Hopkins, Citation2015b; Lifshitz, Citation2022; Theodos, Citation2021). The resulting initiatives have been called “community ownership” (Pill, Citation2019) or transformative place-based philanthropy (Phillips & Scaife, Citation2017). The transformative framing has become increasingly important in creating initiatives of and with communities – instead of for communities – to democratize place-based philanthropic initiatives (Phillips, Citation2018). While this shift demonstrates promise in terms of equity and justice, scholars have found that resident ownership and voice in place-based philanthropy vary among foundations with very few holding these ideas as primary goals (Scally et al., Citation2020; Theodos, Citation2021). Most researchers still agree that the long-term success of place-based philanthropy is dependent on increased transparency, dialog, and trust among local partners (Brown, Citation2012; Karlström et al., Citation2007; Taylor & Buckly, Citation2017).

Framing place-based philanthropy for transnational comparison

The literature review points to an emerging understanding of place-based philanthropy that is more complex than traditional definitions. While community development and neighborhood revitalization continue to be central to these initiatives, issues of regional development and policy, environmental sustainability, urban innovation, and equity, power, and justice are shaping new understandings of place-based work. Our own conception of place-based philanthropy makes room for the complexity of these multiple definitions, while considering other framings lacking representation in the literature such as rural and Indigenous initiatives. We also emphasize the under-researched role and impact of foundations in place-based work (Rocco, Citation2016).

Overview of research methods and case studies

We used case study analysis to conduct our research. Case studies enable researchers to answer specific questions through detailed studies of the processes and contexts of single or multiple organizations (Meyer, Citation2001). While there is considerable flexibility with the research design of case study analysis (Yin, Citation2009; Yin et al., Citation1985), the focus and purpose of the study should be clearly defined (Yin et al., Citation1985). Given our focus on understanding how foundations define and operationalize place-based philanthropy and the difficulty in quantifying such questions, we determined that case study analysis was the appropriate research methodology.

Using the definitions discussed in the literature review, we deductively chose ten cases to explore place-based philanthropy in Canada and the US. Cases were chosen for their potentially innovative place-based approaches to pursuing social justice and equity. A search was performed using academic and practice-based literature, as well as the Internet, to find foundations meeting this requirement. This resulted in a list of 147 foundations. We created a matrix using concepts from the literature to narrow down our preliminary list of potential case studies. We used matrix concepts – such as community engagement or participation, capacity building, convening, advocacy, evaluation and adaptability, collaboration, attention to scale, systemic change or impact, and long-term commitment – to search foundation websites for initiatives that transcend grantmaking. The goal of this process was not to validate actual foundation practice, but rather to determine intentions. This search narrowed the list to 32 foundations in the two countries.

Finally, a transnational comparison of the foundations was performed to make final decisions on the inclusion of cases that represented a diversity of approaches and perspectives. The goal was to find unique cases that would produce lessons for academics and practitioners in both countries. We sought to include place-based philanthropic initiatives reflecting a diversity of geographies including urban, rural, and First Nations lands in the Southern, Midwestern, and Western US and Eastern, Western, and Northern Canada. We likewise looked for diverse foundation types including public, community, private, and family foundations. Finally, we sought a mix of well-known and lesser-known foundations and selected a range of foundations based on endowment sizes and initiative scales (neighborhood, city, region, and nation). The Canadian cases included Centraide of Greater Montreal, Clayoquot Biosphere Trust, Gordon Foundation, McConnell Foundation, and Metcalf Foundation. The US cases included the Blandin Foundation, East Lake Foundation, Greater New Orleans Foundation, Liberty Hill Foundation, and the California Endowment. shows the geographic diversity of the case studies and provides an overview of the cases.

Table 1. Overview of case studies.

After the ten foundations were selected, we ensured consistency across case studies by using the research questions listed above as a template. Because the project started at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we sought information on changes in foundation operations as well. Each case study relied on academic literature, gray papers, and interviews with foundation staff and/or leadership to understand conceptualizations of, and approaches to, place and place-based work. These sources also illuminated how different understandings of place and place-based philanthropy affect foundation collaboration with other stakeholders, evaluation of initiatives, understandings of equity, power, and justice, and work in systems change. The next section summarizes analytical findings based on these ten case studies.

Place-based philanthropy in Canadian and U.S. Foundations

The ten cases were diverse in terms of geography, endowment size, scale of initiatives, and focus of place-based work. As such, analysis of these cases uncovered valuable themes for clarifying foundations’ conceptualizations of place-based philanthropy. To interrogate these themes in a coherent manner, this section is organized in the same order as the introductory research questions. The section begins with an analysis of how foundations understand place-based work. This is followed by discussions of collaboration for systems change, initiative evaluation, and approaches to addressing equity, power, and justice.

Foundation understandings of place-based philanthropy

The understandings of place and place-based philanthropy represented among the selected foundations were complex and multi-faceted. Most understandings conformed to the typology suggested by Williamson et al. (Citation2021)—place as location, locale, and identity or belonging. Multiple foundations understood place as a location defined by inequality for the purposes of poverty reduction. One example is the California Endowment’s Building Healthy Communities initiative in the US. The California Endowment is a large foundation focused on health inequities with an endowment of more than $3 billion and over 200 staff members. It works to impact health outcomes in low-income neighborhoods in California cities by reducing poverty through promotion of civic activism, reimagining public education and justice system institutions, and addressing food deserts and other forms of community wellness.

Almost all foundations in our study defined place as a social locale. This is discussed in more depth in the section on collaboration below. Two of the foundations communicated a conception of place as an identity or sense of belonging. These were for the most part community and family foundations, which scholars note have deeper connections to places (Boris et al., Citation2015; Born, Citation2020; Davies, Citation2017; Harrow et al., Citation2016; Phillips, Citation2018; Pill, Citation2019). These foundations developed a concern for a larger ecosystem consisting of social, ecological, and cultural stakeholders through engagement with places facing natural disasters (as with the Greater New Orleans Foundation) or economic instability (as with the Blandin Foundation). These two cases suggest an addition to the typology proposed by Williamson et al. (Citation2021): place as an ecosystem.

The foundations’ reasons for engaging in place-based work were as heterogeneous as their understandings of place as a concept. Place-based work for many foundations was undergirded by their commitment to a theory of change. A few foundations, such as the East Lake Foundation in the US, followed the trajectory of traditional place-based philanthropy by pursuing alteration of the built environment to improve neighborhood outcomes. The East Lake Foundation began with a focus on physical revitalization in Atlanta, Georgia, and ultimately created a national model implemented in 28 different neighborhoods. Some foundations pursued place-based work to challenge and reform traditional municipal practices and governance regimes. Most of the foundations in the study assumed that change occurs through community empowerment and pursued goals of resident engagement, organizing, and leadership development to build greater capacity in communities. However, the means of empowerment differed from case to case. Centraide of Greater Montreal in Canada and the Blandin Foundation in the US worked directly with communities to support empowerment. For Centraide, this included providing financial support and other resources for community-determined goals. Whereas the Blandin Foundation, a family foundation focused on portions of rural Minnesota, invested in robust leadership development and community capacity building. Two other foundations, Liberty Hill Foundation and the California Endowment in the US, focused on increasing political representation through activism and changing policy through resident action. Liberty Hill, a social justice foundation in Los Angeles, co-produced programs with youth organizers and trained community activists for local boards and commissions. Similarly, the California Endowment worked with residents to develop and implement policies and practices that would enable underserved communities to thrive. Still another foundation, the Greater New Orleans Foundation, engaged in resident scienceFootnote6 to foster understanding and cohabitation with a broader ecosystem.

Place-based collaboration for systems change

In collaborating for systems change, foundations pursued a variety of different roles and leveraged multiple types of relationships to achieve diverse goals. Foundation collaboration with public agencies, other foundations, nonprofit organizations, and community-based stakeholders led to performance of multiple functions including agenda-setter, knowledge-broker, convenor, capacity builder, and co-producer. The choice of role(s) was determined by several factors including desired outcomes, approach to neighborhood change, importance given to specific stakeholders, and foundation motivations and history. These roles were also shaped by the type of systems change pursued by foundations whether it be economic systems change, structural change and alteration of power dynamics, or policy change. Two examples described below demonstrate how foundations’ role(s) in collaboration were shaped by their focus on systems change.

The Liberty Hill Foundation and the California Endowment in the US are following similar trajectories for systems change, possibly due to their close working relationship on multiple projects. Both foundations are working to support changes in public policy through several roles. The foundations understand themselves as convenors between residents, donors, and policymakers. However, their deep engagement with communities necessitates acting as capacity builders and co-producers to empower residents in policy change goals. Both foundations are pursuing co-creative, deliberative processes (Kraeger, Citation2022; National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Citation2020) to transform systems. Liberty Hill leverages relationships and networks to shift power dynamics in the Los Angeles political system and the California Endowment attempts to shift the discourse on healthcare from commodity to human rights.

Another example that illustrates place-based systems change is Centraide of Greater Montreal’s work with the Collective Impact Project, a funder collaborative initiated by Centraide to intensify support for neighborhood development. Centraide convened a group of funders and provided them an opportunity to learn about place-based work through direct engagement in it. This convening was enhanced through development of relationships between the funding group and local stakeholders. Centraide utilizes this model of collaboration to reshape local practices for better community outcomes. Much like Liberty Hill and the California Endowment, this convening role and deep engagement with communities takes them into other roles such as capacity builder.

Though we have provided only a couple of examples of how foundations collaborate in place, they suggest that the type(s) of collaboration taken on by foundations relies heavily on their goals and assumptions about how systems change occurs. Other systems change goals were found among the case studies. The US-based East Lake Foundation scaled up its place-based practice from a local initiative in Atlanta to a national strategy called Purpose Built Communities. The Greater New Orleans Foundation in the US shares its knowledge of place-based practice to assist in disaster relief and recovery in the greater Gulf of Mexico region. Finally, the McConnell Foundation in Canada is working to change local systems through urban innovation which it defines as systems transformation to address inequality and climate change. All these examples required the foundations to fill different roles in multiple types of collaboration with local, regional, and national stakeholders.

Place-based initiative evaluation

As discussed above, place-based philanthropy has struggled to generate data that can be used for field building cross-site comparisons (Kelly et al., Citation2019; Theodos, Citation2021) due to the diverse goals, motivations, and theories of change inherent to foundations’ work. We were not positioned to evaluate foundations’ outcomes, but instead sought to understand how and why place-based foundations evaluated their initiatives. Some foundations collected descriptive neighborhood-level data to prove model efficacy. For instance, the Greater New Orleans Foundation in the US reported outcomes in housing production after Hurricane Katrina to signify their contribution to rebuilding neighborhoods. The East Lake Foundation in the US gathered education, income, employment, and housing data to assert its contribution to neighborhood stability. Other foundations – such as Liberty Hill Foundation in the US and Centraide of Greater Montreal in Canada – used evaluation as a tool for greater resident engagement by allowing communities to determine outcomes and providing room for qualitative forms of data. Still others evaluated their role in place-based work to assist knowledge sharing among foundations. This final form aligns with a major trend in place-based initiative evaluation and is considered by some scholars to be the most effective form when intervening in complex systems (Patrizi et al., Citation2013).

Two foundations from the ten case studies stand out in terms of place-based evaluation. The California Endowment in the US has dedicated significant amounts of funding to evaluation. The scale of funding has allowed it to perform all three types of evaluation listed above. These efforts have produced frequent, comprehensive evaluations of their contributions to policy change, role in place-based work, and engagement with communities (for examples see: California Endowment, Citation2016, Citation2020; Ito et al., Citation2018). This is a level of evaluation that most foundations would struggle to replicate. Though much smaller in size, the Blandin Foundation in the US created an accountability model – the Mountain of Accountability framework (Patton & Blandin Foundation, Citation2014) – that is far-reaching in terms of its attention to transparency with multiple stakeholders including donors, grantees, and community residents. As the field of place-based philanthropy transitions toward more substantial conversations about equity, power, and justice, accountability to community members will become far more important (Beer et al., Citation2021). This model of accountability will likely become an exemplar for challenging power dynamics and moving toward equity in initiative evaluation.

Facing issues of equity, power, and justice

Equity, power, and justice have become central to discussions of place-based philanthropy, especially after the disproportionate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on low-income and communities of color (Bielak et al., Citation2021; Kelly et al., Citation2019; Kraeger, Citation2022; Scally et al., Citation2020). The case studies discussed in this article vary widely in their engagement with equity, power, and justice. All foundations consider the crux of their work to be the creation of more equitable outcomes whether it be the US-based California Endowment’s interventions in health, the Greater New Orleans Foundation’s programs for disaster recovery, or the East Lake Foundation’s initiatives in housing and education. Many of the foundations understand community engagement to be integral to their work, but definitions of engagement vary widely between community-informed and community-owned (Attygale, Citation2020) and most foundations have yet to transform place-based philanthropy by conceding control over initiative design and implementation (Scally et al., Citation2020; Theodos, Citation2021).

Despite these trends, a couple of our cases have experimented with practices which not only seek to achieve equity and justice while addressing power dynamics, but also transform the philanthropic sector itself. Some foundations have sought equity in matters of funding. Both the Liberty Hill Foundation and Blandin Foundation in the US have established community-controlled forms of funding decision-making and the Greater New Orleans Foundation in the US has attempted to democratize philanthropy through annual giving events that allow smaller donations and community control over funding areas. Others such as Liberty Hill Foundation and the California Endowment in the U.S. have taken a bottom-up approach to policy change by training community residents to lead in political processes. Possibly most transformative is Liberty Hill’s recognition of its own positionality in racist, classist, and colonial dynamics of philanthropy. Their staff and leadership have regular discussions about the organization’s positionality and make attempts to educate other funding organizations about these dynamics. The case of Liberty Hill Foundation, in particular, demonstrates the importance of equity through transparent power building, sharing, and wielding (National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Citation2020).

Environmental sustainability

Although the literature on place-based philanthropy has been slow to address environmental sustainability, our cases highlight attention to this issue of equity for non-human stakeholders. The selected foundation initiatives exhibited multiple tactics in this regard. Some of the foundations in this study worked toward the resiliency of places affected by climate change, promoted sustainability and adaptation in urban development strategies, and created environmental education programs. Though place-based foundations have been slow to incorporate environmental issues into their initiatives, they will likely become more prominent as foundations incorporate goals of regional and national stakeholders.

Conclusion: Future of place-based philanthropy

The previous section presented findings from a comprehensive anthology recently produced by our binational research team. A critical summary of the academic and practice-based literature from Canada and the US was presented to understand how place-based philanthropy has been conceptualized, what it entails, and how new issues are being explored and addressed in community development. Based on this body of literature, our team selected ten cases—five from each country – and analyzed them to illuminate how foundations understand their place-based work, as well as how that conceptualization informs their efforts in collaboration, evaluation, and working toward equity and justice.

There were limitations to our study. Due to time and funding constraints, we were unable to incorporate the perspectives of community residents who experience and live with the outcomes of place-based initiatives. Our findings on systems change, collaboration, and equity, power, and justice must be taken at face value as one side of these conversations. Nonetheless, the foundations’ perspectives on place-based philanthropy presented here produced knowledge and lessons important for advancing the field toward shared visions of local development. Furthermore, foundation relationships with private and public sector actors are noticeably missing from this conversation. Though many cases from our study engage with stakeholders from all sectors, the nature of our research questions pushed our analysis in the direction of understanding relationships with other stakeholders, especially community residents. Future research should examine the role of foundations in urban governance regimes and evaluate place-based philanthropy from the perspectives of residents and local stakeholders affected by initiatives.

The aim of this article was to consolidate findings that could further scholarship and applied work in place-based philanthropy. Additionally, its focus on equity, power, and justice was meant to be a call to action for the field. Though the literature is beginning to address these issues because of recent social and political movements and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the field is behind in this regard. In fact, much of what we found from the analysis of our case studies was far from revolutionary or disruptive of social, economic, and political systems. This could be due to the positionality of place-based foundations in these exact systems or the fragmentation of individual initiatives in geographic places where multiple efforts exist. The point of this critique is not to disregard the positive aspects of place-based philanthropy, or even to suggest the end of these types of strategies. Rather, it is to draw attention to the limitations of these types of initiatives, just as we have highlighted their strengths.

In the future, place-based philanthropy must move beyond solely funding change and engagement that merely informs residents. This type of place-based work does not have the ability to bring about systems change and draws our attention to the looming presence of the “local trap,” whereby place-based initiatives are deemed inherently sustainable and just (Purcell, Citation2006). The existing literature and our cases affirm that the field is moving away from this type of place-based work but is still not completely free of it. Place-based foundations must also pay greater attention to the ways in which their own efforts and operations reinforce systems of domination and marginalization including neoliberalism, neo-colonialism, environmental injustice, racial injustice, and more. Chen Duxiu suggests that we need a “final ethical awakening” – after the scientific and political awakenings – that allows society to pursue “universal values of freedom and equality” (Xu, Citation2018, p. 168). This final awakening allows us to reimagine place-based philanthropy to be truly transformative by challenging power dynamics and marginalization, offering accountable co-produced initiatives, and engaging with broader ecosystems of human and non-human stakeholders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Key differences between community foundations and United Ways exist. United Ways cover more geographic area, direct more total funding to communities, and work primarily in human services. Community foundations address more community development issues and spend more funding per capita than United Ways. For more, see Waldrip et al. (Citation2022).

2. Community development corporations (CDCs) are nonprofit organizations that provide programs and services to a specific neighborhood and frequently develop affordable housing. They act as intermediaries between communities and larger nonprofits, such as foundations.

3. Vibrant Communities was a poverty-reduction initiative in 13 Canadian communities. For more information see: https://mcconnellfoundation.ca/initiative/vibrant-communities/.

4. Reimagining the Civic Commons is a national initiative in the U.S. funded by the JPB, Knight, Kresge, and Rockefeller Foundations to revitalize public spaces and increase public participation, equity, and sustainability in communities. For more information see: https://civiccommons.us/app/uploads/2018/01/Project-Backgrounder.pdf.

5. The Bass Center is a Brookings Institute funded initiative that champions placemaking for social, economic, and environmental transformation. For more information see: https://www.brookings.edu/about-the-bass-center/.

6. Resident science uses public participation to conduct scientific examinations.

References

- Allen-Meares, P., Gant, L., & Shanks, T. (2011). Embedded foundations: Advancing community change and empowerment. The Foundation Review, 2(3), 7. https://doi.org/10.4087/FOUNDATIONREVIEW-D-10-00010

- Alongi, T., & Tilghman, L. (2021). Time to act: How philanthropy must address the climate crisis. FSG.

- Attygale, L. (2020). Understanding community-led approaches to community change. Tamarack Institute. https://www.tamarackcommunity.ca/hubfs/Resources/Publications/2020%20PAPER%20%7C%20Understanding%20Community-Led%20Approaches.pdf?hsCtaTracking=15a5334b-43c5-4723-8e97-8e3553f0e40a%7Cc3943068-2f66-42fc-841c-04112489389e

- Azevedo, L., Bell, A., & Medina, P. (2022). Community foundations provide collaborative responses and local leadership in midst of COVID‐19. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32(3), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21490

- Beer, T., Patrizi, P., & Coffman, J. (2021). Holding foundations accountable for equity commitments. The Foundation Review, 13(2), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1565

- Bielak, B., Isom, D., Michieka, M., & Breen, B. (2021). Race and place-based philanthropy: Learnings from funders focused on equitable impact. Bridgespan.

- Boris, E. T., De Vita, C. J., & Gaddy, M. (2015). The National Center for Family Philanthropy’s 2015 trends study: Results of the first national benchmark survey of family foundations. National Center for Family Philanthropy and Urban Institute.

- Born, J. (2020). National Center for Family Philanthropy’s trends 2020: Results of the second national benchmark survey of family foundations. National Center for Family Philanthropy.

- Brookings Institution. (n.d.). About the bass centre. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/about-the-bass-center/

- Brown, P. (2012). Changemaking: Building strategic competence. The Foundation Review, 4(1), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.4087/FOUNDATIONREVIEW-D-11-00033

- Burns, T., & Brown, P. (2012). Final report: Lessons from a national scan of comprehensive place-based philanthropic initiatives. (Report prepared for the Heinz endowments). Urban Ventures Group.

- Cabaj, M. (2011). Cities reducing poverty: How vibrant communities are creating comprehensive solutions to the most complex problems of our time. Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement.

- California Endowment. (2016). A new power grid: Building healthy communities at year 5. Retrieved February 14, 2021, from https://california.foundationcenter.org/reports/a-new-power-grid-building-healthy-communities-at-year-5/

- California Endowment. (2020). Building healthy communities: A decade in review. Retrieved January 2, 2022, from https://www.calendow.org/app/uploads/2021/04/The_California_Endowment_Decade_In_Review_2010_2020_Executive_Report.pdf

- Carman, J. G. (2001). Community foundations: A growing resource for community development. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 12(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.12102

- Castells, M. (2010). The rise of the network society (2nd ed., Vol. 1). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cattacin, S., & Zimmer, A. (2016). Urban governance and social innovations. In T. Brandsen, S. Cattacin, A. Evers, & A. Zimmer (Eds.), Social innovations in the urban context (pp. 21–44). Springer International.

- Colinvaux, R. (2018). Defending place-based philanthropy by defining the community foundation. BYU Law Review, 1.

- Colting-Stol, J. (2020). Foundations and climate action: Exploratory research. PhiLab Research Paper #, 21.

- Davies, R. (2017). Giving a sense of place. Philanthropy and the future of UK civic identity. Charities Aid Foundation.

- Dewar, T. (2010). Aligning with outside resources and power. In A. C. Kubisch, P. Auspos, P. Brown, & T. Dewar (Eds.), Voices from the field III: Lessons and challenges from two decades of community change efforts (pp. 77–88). Aspen Institute.

- Dunsky Energy Consulting. (2020). Building Canada’s low carbon future: Opportunities for the philanthropic sector. Report prepared for Environment Funders Canada.

- Evergreen. (2017). Towards a civic commons strategy (Report to JW McConnell Family Foundation).

- Fehler-Cabral, G., James, J., Preskill, H., & Long, M. (2016). The art and science of place-based philanthropy: Themes from a national convening. The Foundation Review, 8(2), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1300

- Ferris, J. M., & Hopkins, E. (2015a). Moving forward: Addressing spatially-concentrated poverty in the 21st Century. In E. M. Hopkins & J. M. Ferris (Eds.), Place-based initiatives in the context of public policy and market: Moving to higher ground (pp. 83–86). Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California.

- Ferris, J. M., & Hopkins, E. (2015b). Place-based initiatives: Lessons from five decades of experimentation and experience. The Foundation Review, 7(4), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1269

- Gamble, J. (2010). Evaluating vibrant communities 2002–2010. Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement.

- Gaynair, G., Treskon, M., Schilling, J., & Velasco, G. (2020). Civic assets for more equitable cities. Urban Institute.

- Graddy, E. A., & Morgan, D. L. (2006). Community foundations, organizational strategy, and public policy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(4), 605–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764006289769

- Harrow, J., Jung, T., Phillips, S. D., & Phillips, S. D. (2016). Community foundations: Agility in the duality of foundation and community. In T. Jung & J. Harrow (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philanthropy (pp. 308–321). Routledge.

- Hopkins, E. M. (2015). The state of place-based initiatives. In E. M. Hopkins & J. M. Ferris (Eds.), Place-based initiatives in the context of public policy and markets: Moving to higher ground (pp. 9–30). Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California.

- Horwitz, S., & Woolner, G. (2016). Canadian placemaking: Overview and action. Co*Lab.

- Institute for Voluntary Action Research. (2015). Place-based funding: A briefing paper. Institute for Voluntary Action Research.

- Ito, J., Pastor, M., Lin, M., & Lopez, M. (2018). A pivot to power: Lessons from the California endowment’s building healthy communities about place, health and philanthropy.

- Karlström, M., Brown, P., Chaskin, R., & Richman, H. (2007). Embedded philanthropy and community change [Issue brief]. Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago. http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/publications/ChapinHallDocument_2.pdf

- Kelly, T., Brown, P., Yu, H. C., & Colombo, M. (2019). Evaluating for the bigger picture: Breaking through the learning and evaluation barriers to advancing community systems-change field knowledge. The Foundation Review, 11(2), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1469

- Kerman, B., & Miller, C. (2022). A promising place-based collaborative impact investing fund strengthens community and informs philanthropic practice. The Foundation Review, 14(4), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1631

- Kraeger, P. (2022). Shifting philanthropic engagement: Moving from funding to deliberation in the eras of the COVID-19 global pandemic and black lives matter. Local Development and Society, 3(2), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2021.1939766

- Kraeger, P., & Robichau, R. (2017). Questioning stakeholder legitimacy: A philanthropic accountability model. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 39(4), 470–519.

- Kubisch, A. C., Auspos, P., Brown, P., & Dewar, T. (2010). Voices from the field III: Lessons and challenges from two decades of community change efforts. Aspen Institute.

- Lifshitz, C. C. (2022). Philanthropy-government collaborations in urban renewal and community development: Two case studies from Israel’s periphery. Local Development and Society, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2022.2157743

- Mack, K. P., Preskill, H., Keddy, J., & Jhawar, M. K. (2014). Redefining expectations for place-based philanthropy. The Foundation Review, 6(4), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1224

- Markey, S. (2010). Primer on place-based development. Simon Fraser University.

- Markley, D., Topolsky, J., Macke, D., Green, T., & Feierabend, K. (2016). A new domain for place-rooted foundations: Economic development philanthropy. The Foundation Review, 8(3), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1316

- Martinez-Cosio, M., & Rabinowitz Bussell, M. (2013). Catalysts for change: 21st century philanthropy and community development. Routledge.

- Melish, T. J. (2010). Maximum feasible participation of the poor: New governance, new accountability, and a 21st Century war on the sources of poverty. Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal, 13, 1–134.

- Meyer, C. B. (2001). A case in case study methodology. Field Methods, 13(4), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X0101300402

- Millesen, J. L., & Martin, E. C. (2014). Community foundation strategy: Doing good and the moderating effects of fear, tradition, and serendipity. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(5), 832–849. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013486195

- Murdoch, J. (2007). The place-based strategic philanthropy model. Research brief. The Center for Urban Economics.

- National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. (2020). Power moves: Your essential philanthropy assessment guide for equity and justice. https://www.ncfp.org/knowledge/power-moves-your-essential-philanthropy-assessment-guide-for-equity-and-justice-2/

- Oosterlynck, S., Kazepov, Y., Novy, A., Cools, P., Barberis, E., Wukovitsch, F., Sarius, T., & Leubolt, B. (2013). The butterfly and the elephant: Local social innovation, the welfare state and new poverty dynamics. ImPRovE. Discussion Paper No. 13/03. Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy – University of Antwerp.

- Patrizi, P., Thompson, E. H., Coffman, J., & Beer, T. (2013). Eyes wide open: Learning as strategy under conditions of complexity and uncertainty. The Foundation Review, 5(3), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1170

- Patton, M. Q., & Blandin Foundation. (2014). Mountain of accountability: Pursuing mission through learning, exploration and development. Retrieved January 25, 2021, from https://blandinfoundation.org/content/uploads/vy/Final_Mountain_6-5.pdf

- Perry, D. C., & Mazany, T. (2014). The second century: Community foundations as foundations of community. In T. Mazany & D. C. Perry (Eds.), Here for good: Community foundations and the challenges of the 21st Century (pp. 3–25). ME Sharpe.

- Phillips, S. (2018). The new place of place in philanthropy: Community foundations and the community building movement [Poster presentation]. The International Society for Third Sector Research (ISTR), Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Phillips, S., Jung, T., & Harrow, J. (2011). Community foundations as community leaders? Comparing developments in Canada and the United Kingdom [Poster presentation]. Annual Meeting of ARNOVA, Toronto.

- Phillips, S., & Scaife, W. (2017). Has philanthropy found its place? place-based philanthropy for community building in Australia and Canada [Poster presentation]. Annual ARNOVA Conference, Grand Rapids, MI.

- Pill, M. C. (2019). Embedding in the city? Locating civil society in the philanthropy of place. Community Development Journal, 54(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsx020

- Purcell, M. (2006). Urban democracy and the local trap. Urban Studies, 43(11), 1921–1941. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600897826

- Reid, B., Butters, L., & Vodden, K. (2022). Employment-related geographic mobility (E-RGM), place attachment, and philanthropy: Interconnections and implications for rural community well-being in Newfoundland and Labrador. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 5(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-021-00139-1

- Reid, R. J., Palmer, E. A., Reid, M. R., & Murillo, X. L. (2020). Rural Foundation Collaboration: “Houston we have a problem”. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 5(2), 273–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-020-00089-0

- Reid, R. J., Reid, M. R., & Murillo, X. L. (2022). Place-based philanthropy: Who is that in my backyard? Local Development and Society, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2022.2107945

- Rizzo, F., & Deserti, A. (2017). Cities and regions development. In D. Domanski & C. Kaletka (Eds.), Exploring the research landscape of social innovation – a deliverable of the project Social Innovation Community (SIC) (pp. 84–101). Sozialforschungsstelle.

- Rocco, M. (2016). Partnership, philanthropy and innovation: 21st century revitalization in legacy cities. [ Publicly accessible penn dissertations]. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1977

- Scally, C. P., Lo, L., Pettit, K. L. S., Anoll, C., & Scott, K. (2020). Driving systems change forward, leveraging multisite, cross-sector initiatives to change systems, advance racial equity and shift power. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and Urban Institute.

- Seibert, K. (2019). Giving under the microscope: Philanthropy, legitimacy and a new era of scrutiny. Third Sector Review, 25(1), 123–141.

- Siegel, B., Winey, D., & Kornetsky, A. (2015). Pathways to systems change: The design of multisite, cross-sector initiatives. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Community Development Investment Center Working Paper Series.

- Silberberg, S., & Lorah, K. (2013). Places in the making: How placemaking builds places and communities. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Squires, E., Markey, S., & Gibson, R. (2022). Place-based environmental philanthropy: The role of community-based organizations in the Skeena Watershed. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 13(2), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjnser585

- Taylor, M., & Buckly, E. (2017). Historical review of place-based approaches. Lankelly Chase.

- Theodos, B. (2021). Examining the assumptions behind place-based programs. Urban Institute.

- Thomson, D. E. (2021). Philanthropic funding for community and economic development: Exploring potential for influencing policy and governance. Urban Affairs Review, 57(6), 1483–1523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087420926698

- Tomalty, R. (2013). Sustainable cities: The role for philanthropy in promoting urban sustainability. Canadian Environmental Grantmakers Network.

- Waldrip, K., Paarlberg, L. E., LePere Schloop, M., & Sexton, D. (2022). Philanthropic capital for communities: A comparative analysis of community foundation and united way grantmaking. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/28852/PhilanthropicCapitalforCD_2205_Final.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Williamson, A., Luke, B., & Furneaux, C. (2021). Perceptions and conceptions of ‘place’ in Australian public foundations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(6), 1125–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764021998461

- Xu, J. (2018). Rethinking China’s rise: A liberal critique. Cambridge University Press.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. In Applied social research series (4th ed., Vol. 5). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yin, R. K., Bateman, P. G., & Moore, G. B. (1985). Case studies and organizational innovation: Strengthening the connection. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization, 6(3), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554708500600303