Abstract

The long-term care environments in which older persons with dementia live could have an effect on residents and staff. The purpose of this study was to evaluate renovations to a long-term care center for individuals with advanced dementia using a multi-method approach. Renovations included lighting, design elements to reduce noise, and exit-seeking behaviors, along with attempting to create a more home-like environment through smaller dining spaces and other changes. Results revealed that while some aspects of the renovations were rated by staff as being positive, little impact could be found for residents based on in-unit observations or standard assessments.

Introduction

The environmental design of long-term care homes may have significant impacts on the well-being of persons living with dementia who live there as well as the staff working with them. As such, there is an increased interest in redesigning and renovating existing long-term care spaces for residents with dementia, particularly since residents with some form of cognitive impairment make up the majority of residents residing in long-term care (Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citationn.d.-a). Special attention needs to be taken to the physical design of spaces to accommodate the unique needs of people living with dementia. Examples include: designing to account for common behaviors (e.g., agitation, aggression, exit-seeking) that could be triggered by the spaces where they live (e.g., loud noises, inappropriate lighting, doorway design); enable wayfinding, autonomy, and physical function; and to enhance social interactions and quality of life (Chaudhury et al., Citation2018).

In their systematic review, of 66 studies, Joseph et al. (Citation2016) identified many possible environmental elements that could have positive effects on residents as well as staff including unit size, lighting, visual barriers that hide exits, social space, flooring, temperature, and noise. However, they also stated that it is often difficult to assess the environment independent of other factors in the studies examined. In addition, there has been less focus on staff than on residents.

Similarly, in their review, Chaudhury et al. (Citation2018) identified several beneficial design features, primarily in cross-sectional studies, such as sensory stimulation, spatial layout, and home-like character. The term “home-like,” as it currently tends to be used within the long-term care sector, can refer to esthetic features like furnishings or décor, as well as features related to the size of the spaces, privacy, or the number of residents cared for together (Chaudhury et al., Citation2018). These authors identified a need for pre- and post-methodologies and longitudinal studies to fully assess the benefits of these environmental factors. Two studies that have examined home-like settings longitudinally have found some improvements for residents (Morgan-Brown et al., Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2010). However, as mentioned above, even longitudinal studies can be confounded by other changes that occur at the same time as the physical changes (Joseph et al., Citation2016). For example, in the Morgan-Brown et al. (Citation2013) and Smith et al. (Citation2010) studies, there were also major changes in how the staff and residents interacted, particularly at mealtimes. In addition, in the Morgan-Brown et al. (Citation2013) study none of the residents were the same between the pre and post-measurements, so resident characteristics might have affected the outcomes which were measured.

Facility redesigns and renovations offer important naturalistic opportunities for researchers interested in exploring the potential effects of the physical environment, as existing facilities seek ways to improve their physical settings without having to create completely new buildings. The objective of the present multi-method study was to examine the effects of renovations to a dementia special care center on residents and staff. More specifically, our research questions were related to determining whether the design features [e.g., lighting, acoustics, camouflaged exit doors, and the more home-like features (smaller dining spaces, furnishings, and finishes)] of the new spaces would result in improvements for residents as well as those working in the spaces. We also examined whether the original goals of the design for residents (e.g., greater autonomy and activity, less reactive behaviors, better quality of life) and staff (e.g., better working conditions, utilization of new technology) were met.

Methods

Setting

The study took place in a residential healthcare facility in one Canadian Prairie city. The renovations occurred in the facility’s four long-term care units for residents living with advanced dementia.

Renovations

The designers and administrators sought to improve well-being and work conditions through division of each unit into smaller five resident “households,” circadian lighting, biophilic and other wayfinding elements including personalization of room entrances, residential looking finishes, camouflaged exits, and a more centralized nursing station. A main design intention was to create a more home-like environment. The design team expected that the renovations would increase resident activity, and decrease resident agitation and stress. In addition, the renovations were expected to enhance the efficiency of care work (e.g., improved workflow) and benefit the well-being and satisfaction of staff.

Significant elements of the renovations included: upgrading current finishes and furniture, adding new technologies (e.g., staff communication technology), and replacing the single large dining/recreation and lounge spaces per unit with three smaller lounge/dining spaces. The designers also inserted a new pavilion and outdoor courtyard space between the units for both spontaneous and planned recreational activities. Unfortunately, due to numerous renovation delays and pandemic restrictions, the pavilion and courtyard spaces were not included in this research. Furthermore, one of the four special care units was not wholly renovated during the final data collection, so only three could be studied after the renovations. See for renovation elements and for photos.

Appendix 1. Listing of all substantive elements involved in the renovations of the existing units.

Appendix 2. Photos of some of the spaces before and after the renovations, as well as some of the new design elements.

Study design

The team collected data before (spring/summer 2017) and after (spring/summer 2019) renovations. Because of the lengthy time between data collection phases, both resident and staff cohorts were not identical at both time points. Data on several variables were collected both before and after the renovations, whereas data on other variables were only collected post-renovations (e.g., survey questions about the resulting units). Multiple methods permitted triangulation of findings. Of note, the research team was not involved in the renovation design planning.

Participants

During data collection pre-renovation, 53 residents (59% female, average age 79 years) lived in the four special care units. This was lower than the maximum capacity of 60 because new admissions were on hold due to the impending renovations. After the renovations, in the three studied units, there were 44 residents (69% female, average age of 81 years), 16 of whom had lived in the units before the renovations.

All staff who worked on the units were eligible to participate in surveys before and after the renovations, including healthcare aides, nurses, clerical partners, patient care managers, recreation facilitators, and allied health professionals. According to human resource records, there were 84 and 82 staff working on the units, respectively, before and after the renovations.

Data collection methods

Resident characteristics

Aggregated chart data were provided to the researchers to protect resident privacy and align with the ethics protocol. The data included residents’ sex, age, and several relevant scales from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set 2.0 (RAI-MDS; Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citationn.d.-b): aggressive behavior, cognitive performance, pain, social engagement, depression, activities of daily living (ADL; long and short form), and ADL self-performance. These data were collected as part of routine resident assessments (i.e., not by the research team).

Staff surveys

The online surveys included questions (modified from a survey used by Newsham et al., Citation2013) at both time points on job satisfaction and demands; time spent in various work spaces and in different types of activities; and perceptions of environmental aspects of working conditions. After the renovations, staff were also asked about the effects of the renovation on residents as well as on their own work, the home-like nature of the spaces, and any perceived changes in care or recreation. Most questions were closed-ended, with a few open-ended comments and responses.

Behavioral mapping

Daily living behavior and space utilization were measured within the special care units. Before and after renovations, trained research staff mapped behaviors at 30-min intervals for 5 days (weekday and weekend), from 6 a.m. until 12 a.m. In both cases, mapping was done in summer (June 2017 and July 2019, before the pandemic). Observers moved unobtrusively through the hallways and “public” areas of the units. On a paper copy of the floor plan, each observer recorded (coded) behaviors of individuals in particular locations (see for details). No further identifying features were included, to protect confidentiality and privacy; as such, we are unable to differentiate between residents, staff, or visitors, for codes that could apply to all. Bathing suites and resident rooms were considered private spaces. Resident rooms would only be observed if the door was wide open and someone was clearly there. All paper-based recordings of observations were digitized to geo-located spaces using QGIS (software for spatial data).

Table 1. Behavior codes used.

Acoustic information

During weekdays, acoustic measurements (in dBA) were taken in several spaces before and after the renovations. Data were collected using a Rion NL-42 acoustic meter positioned at standing ear height (1,500 mm), at about 1:30 p.m., for a period of 10 min.

Lighting

Before and after the renovations, lighting was measured in several locations using a handheld light meter (Konica Minolta CL-70F Illuminance Meter), in the morning (about 9:30 a.m.) and afternoon (about 1:30 p.m.). For each location, readings were taken at a seated and standing eye level, for brightness, correlated color temperature (color hue of the light), and the color rendering index (ability of the lighting to show objects in their true colors, as they would appear in natural lighting).

Statistical analyses

Frequencies were calculated for all quantitative survey variables. When statistically comparing survey data before and after the renovations, independent sample t-test were used because the samples were non-identical at the two time points (respondents were not identifiable because surveys were anonymous). When the data were not normally distributed Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Tests were used. When applicable, statistical testing was also done using z-tests for proportions for binary data.

Heat maps were created from the behavioral mapping observations to show where and how people were using spaces within the units. To perform statistical testing, z-tests were used for statistical comparisons of before and after proportions, based on location and type of activity observed.

For the acoustic information, all data points for a specific type of location for all units were compared before and after renovations, using Mann–Whitney Rank Sum tests because the data were not normal. For the lighting variables, descriptive statistics were generated for each type of space at the different times of the day, for both time points.

Results

Resident characteristics

Residents of the units before the renovations ranged in age from 63 to 94, and after the renovations, the age range was 62–92. The average age was two years higher (81 vs. 79) in residents after the renovations. presents resident characteristics based on the various RAI-MDS scales. Cognitively, the residents had similar scores based on mean values, whereas pain scores seemed to be slightly better after the renovations. Other variables were similar at both time points, although there might have been subtle differences between scores. Contrary to expectations, aggressive behavior did not appear to be lower after the renovations. Likewise, social engagement scores were quite low and tended to be lower after the renovations.

Table 2. Resident characteristics drawn from the Resident Assessment Instrument-Minimum Data Set (RAI-MDS).

Staff surveys

Respondents

Before and after the renovations, 41 and 44 staff, respectively, completed at least some questions from the survey. details their characteristics. There were no statistically significant differences in respondent characteristics before and after the renovations, except for time working at the healthcare facility (shorter after renovations) and usual shift worked (fewer worked on day shifts and more worked mixed shifts after the renovations). Of the 44 respondents who completed the post-renovation survey, 41 had worked on the units before the renovations.

Table 3. Descriptive characteristics of the staff participants of the survey before and after the renovations (N: number of responses).

Impact of the renovation on residents according to staff

As seen in , the majority of staff members reported positive effects of the renovations on residents’: quality of life, mental stimulation, emotional well-being, quality of interaction with other residents, staff and family/friends, amount of interaction with other residents, staff and family/friends, and access to recreational opportunities. There were also several questions where the median response was that of “no impact” on residents’: safety, autonomy and independence, physical activity, access to outdoor space, dining experience, and challenging or responsive behaviors. There were no questions where the median response for the renovation impact indicated a negative response. However, all questions had at least some participants who chose negative responses.

Table 4. Impact of renovation on residents as per staff.

Table 5. Percent (%) use of spaces (based on observed codes), before and after the renovations.

Renovations and resident needs according to staff

Staff most commonly reported that the renovated spaces met residents’ needs (“agree” = 45.2%), but 35.7% indicated a “neutral” response. In open-ended comments, some of the latter elaborated that this was because they saw “no noticeable difference” compared to the previous spaces, whereas others perceived both positive and negative aspects (i.e., balancing out to “neutral”). For example, some commented on the renovated dining areas being challenging for group activities, but “easier to provide quiet spaces without having to utilize resident rooms.”

Other perceptions also varied between respondents. For instance, having fewer individuals in each dining area, for one respondent, meant that “I’ve completed less PPCO [Protection for Persons in Care Office] reports as residents are not all clustered together in one dining area.” A contrasting opinion was that “due to closer proximity, the residents have nowhere to go to get away from each other, leading to negative interactions.”

Positive comments about the post-renovation space overall included that it is a “better environment for the residents,” “a more appealing look to visitors and staff,” and “I see benefits in the homey like decor and less stimulation overload.” Other positive comments included: “safe and organized,” “the new renovations are great in terms of the rooms,” and “more space for wandering/walking.”

However, some staff expressed a strong sentiment that the renovation was not suitable for the residents living in the unit, as exemplified by this quote:

“The designer of the unit lacked insight into the safety needs of the current residents on the unit. The unit was designed for a higher functioning resident.”

Home-like nature of spaces

When asked whether the renovated space was home-like the most common response was “agree” (45.2%), followed closely by “neutral” (38.1%). Positive items noted by respondents included: photographs in the display cabinets, customized doors, furniture, “lovely windows with a view,” and greater quiet. Negative comments pointed to the layout still being hospital-like, and that the lounge area was not home-like because of the sensory bubble tubes.

Staff’s own work

Staff were asked about the impact of the renovation on their own work, with responses again varying (). The most common response to questions about the sense of safety at work was “no impact” (47.6%), although 33.3% reported a “positive impact,” and 16.7% reported a “negative” or “very negative” impact. Choking risks for residents were mentioned in one comment because of the “dining room being separated huge safety risk—cannot watch all residents.” Another respondent commented that because “residents are able to see into the med[ication] room and can be a trigger for responsive behaviors.” In addition, one respondent wrote the “nursing station looks like teller window at a bank and central location; can trigger responsive behaviors.”

“For enjoyment of time with residents,” more than half (59.5%) of respondents reported that the renovation had a “positive” or “very positive” impact, with <10% reporting negative impact. Digital photograph frames (outside resident rooms) were mentioned as both positive and negative in the following comment from one respondent: “the digital pictures provide an opportunity to interact with residents, but they are often not working.”

Appendix 3. Impact of renovations on staff’s own work.

Staff were also asked about the impact of the new communication system (Vocera Smartbadge) on their work. Most staff indicated positive (43.9%) or very positive (31.7%) impact. Positive comments were related to saving time, the ability to call for help in an emergency, and easier communication. One person went as far as writing: “Vocera is awesome at work best thing ever.” Negative aspects included staff not wearing the equipment, and occasional connection issues.

Job satisfaction and demands

There were no differences in respondents’ ratings of job satisfaction, stressfulness of their job, and extent of conflicting demands from other people (p > 0.3).

Time in places where staff work

At both time points, staff reported spending most of their time in the nursing area, resident common areas, and resident rooms. Similar percentages of time were reported before and after renovations.

Time spent in various types of activities

After the renovations staff reported spending almost twice as much time on resident personal care as compared to those responding to this question before the renovations (30.2 vs. 14.5%). Similarly, staff reported spending more time assisting with meal times after (15.0%) as compared to before (8.8%) the renovations. The opposite was true for computer work whereby there was more reported time before (11.8%) vs. after (6.1%). Statistics were also conducted with a subsample of those who identified as nurses or health care aides; findings were essentially the same.

Changes in care or recreation

Almost half (42.5%) of respondents reported having changed their approach to resident care between the two time points, which may have reflected some parallel efforts during these years to train staff in newer and more flexible care approaches suitable for persons with dementia. One respondent however specifically mentioned: “the new layout of the ward has given the nurse(s) a more open approach to care.”

Just over half (53.8%) of staff believed there had been a change in recreation. Several commented that the renovated unit was less spacious, “awkward and small,” making it difficult for residents with wheelchairs or walkers to move around (especially in the dining area), and making recreation more challenging. In contrast, one respondent commented that “because of the more intimate and secluded seating areas there is more one on one interaction with the residents,” and another wrote that it is now “easier to provide smaller group activities.” Another respondent expressed that “walking is still great as the hallways are long and they can walk around in the loop.”

Environmental aspects of working conditions

Many environmental aspects were rated in a more positive light after the renovations compared to before, although some of the variables were still rated as “somewhat unsatisfactory” or “neutral” (). No post-renovation ratings were significantly worse according to median scores. Staff were asked in this section about the degree to which the physical environment of the newly renovated unit interfered with or enhanced their ability to perform their job duties. The most common response was “no impact” (31.7%).

Appendix 4. Environmental aspects of working conditions before and after the renovations.

Behavior mapping for all users (residents, staff, and visitors)

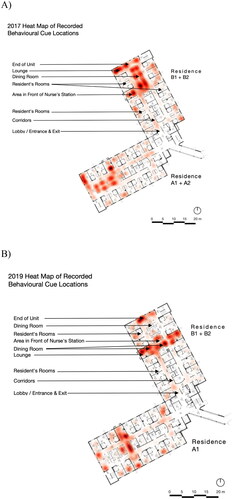

Locations ()

Hallway use increased significantly by 11.2%. Spaces with decreased use included: end of unit (by 5.2%), dining rooms (by 3.0%), nursing stations (by 1.7%), and front of nursing stations (by 0.4%).

Activities/behaviors

Several activities/behaviors were significantly lower after the renovations (): charting (by 2.3%), elopement (by 0.6%), eating/drinking (by 2.6%), leisure (by 4.2%), talking (by 5.4%), and being mobile (by 3.0%). Proportionately, several activities increased after the renovations: medication administration (by 0.6%), physical care (by 8.5%), and being stationary (by 7.1%).

Table 6. Percent of codes that were labeled for the following activities/codes before and after the renovations.

Heat maps

See for the before and after heat maps, with all units combined from each time point. Note that in 2017 there were four units assessed, but in 2019 only three units were assessed; due to this, intensities are higher in 2017 overall. One space of note is the dining room near the end of the unit. It did not appear to be used as much as the others after the renovations.

Acoustic information

Noise levels are shown in for key spaces that were affected by the renovations. Before the renovations, noise levels were comparable for these types of long-term care spaces (Chaudhury et al., Citation2018). All spaces in the units were significantly quieter after the renovations. However, these spaces were still louder after the renovations, compared to what would be recommended for a residential space (Chaudhury et al., Citation2018).

Table 7. Levels of sound by space before and after the renovations.

Lighting

Lighting improved dramatically in the dining spaces in terms of level (brightness) and color temperature (). Before the renovations, lighting levels were quite consistent, with a warm or yellowish hue, regardless of the time of day. Circadian lighting boxes added to the dining room ceiling resulted in the color tuning better mimicking outdoor conditions, with the lighting being much cooler or bluer during the day.

Table 8. Lighting values for the dining rooms and hallway spot measurement locations before and after the renovations during the morning (about 9:00 a.m.) and afternoon (about 1:30 p.m.).

The lighting system in hallways was not changed but lighting levels improved somewhat, likely due to re-lamping and cleaning. The color remained relatively consistent, with a tendency toward a consistent warm color.

Color rendering index values before the renovations could be considered to be in the good (80–90) range (Westinghouse, Citationn.d.). The color rendering in dining spaces improved, with the average moving to excellent (>90) (Westinghouse, Citationn.d.). The hallway values remained stable as good.

Discussion

Staff

Generally, the renovations were viewed positively by staff. Environmental aspects of their working conditions were rated slightly more positively after the renovations in terms of esthetic appearance, conversation privacy, and noise associated with conversations or patient vocalizations. Most staff also reported that the renovation improved their enjoyment of time with residents. The introduction of the staff communication technology system was also positively received. In contrast, job satisfaction and demands remained similar, and sense of safety was mostly unaffected.

One change related to staff work was resident care. Data from both the observations and surveys concur that staff were spending more time providing care after the renovations. It is unclear whether this increase in care provision was connected to the renovations and their effects on workflow/productivity, the fact that residents needed more care over time, or other factors such as the introduction of new staff training. In a focus group study in Canada and Sweden, staff believed that a better ambience would likely help staff provide better resident care and improve job satisfaction (Lee et al., Citation2021). Cross-sectional studies that have examined staff outcomes of environmental designs have been related to facility size, unit type, and the use of mechanical lifts (Joseph et al., Citation2016). Chaudhury et al. (Citation2017) examined staff practices and perspectives related to a dining room renovation via survey. Staff in their study identified many improvements including the general ambience, “homelikeness,” lighting, and noise levels. Care services did not appear to change very much but there may have been a ceiling effect as they noted that scores were high before the renovations and hence had little room for improvement. Importantly, statistical testing was not done on their survey responses, so it is unclear which findings might have reached statistical significance.

Residents

Based on the RAI-MDS data and behavior mapping, the findings do not indicate an overall positive effect of the renovations on the residents. Contrary to the hopes of the designers and administrators, it did not appear that engagement was higher, nor were residents more mobile. In terms of responsive behaviors, vocalizations were higher, the tendency toward aggression was not changed, although elopement was lower, potentially indicating an improvement.

Staff reported most commonly that the renovation had “no impact” on residents’ safety, autonomy and independence, physical activity, dining experience, and challenging or responsive behaviors. However, staff did perceive many positive impacts on residents’: quality of life, mental stimulation, quality and number of interactions with others, and access to recreation facilities. It is possible that staff were envisioning these as potential benefits associated with the pavilion, which we were unable to study, because these responses do not match with the findings from the RAI-MDS or behavior mapping data mentioned above (e.g., engagement). In addition, staff may have been biased toward positive perceptions because the facility promoted how beneficial the renovations would be. This points to the possible impact of expressed expectations perceived by the employer influencing staff perceptions.

A study in Australia examined the effects on residents with dementia when they were moved from a traditional institutional setting into cottages that accommodated 15 residents (Smith et al., Citation2010). Behavior mapping showed that resident engagement had improved in that study. It is important to point out that in addition to the changed setting (institutional to a small home-like setting), there were also changes in staffing and training, such that staff in the new cottages interacted with residents in many more ways, including eating meals with residents. Meals changed as well, from institutional meals in a large dining room to a “home-style kitchen” whereby care staff prepared the meals (Smith et al., Citation2010).

A study in Ireland which seems more in line with our project because new buildings were not constructed, also found that engagement was better in residents in the more home-like unit (Morgan-Brown et al., Citation2013). Again, there are some key differences between our study and the Irish study in that there was a kitchen added to the living space in the Irish study. Residents could be engaged in activities related to food preparation. Also, none of the residents were the same in the pre and post-comparisons that were made, so differences between pre and post could be attributed to the characteristics of the residents, rather than changes in how the residents engaged in response to the new design.

It is often challenging to compare studies because of resident characteristics, which are often not reported. Residents with dementia can be extremely heterogeneous in their characteristics (e.g., cognition and mobility). These characteristics could impact on their ability to engage in a variety of ways.

Overarching design-related findings

Family unit/home-like and smaller dining/lounge spaces

Approximately half of staff believed the renovated space was home-like, with another third indicating a neutral response. A major aspect of the design to invoke a home-like feel involved creating five person groupings in small dining rooms and lounges. Although the new spaces may have meant that certain residents could be kept separate from each other (and so lessen potential for conflicts), the smaller spaces may have limited their ability to be used for leisure purposes, or to facilitate visits with family and friends. In part, this might explain why we observed fewer behaviors that were categorized as involving leisure after the renovations. Some staff also reported that the small spaces actually kept some residents closer together during meals (which could have increased conflict). Residents’ own behavior and characteristics, as mentioned above, did not evidence positive change over the two periods, so direct effects of a home-like design on them are unclear.

An unintended consequence of creating three dining spaces instead of one larger space on a unit, without a change in staffing, was greater potential for choking going unnoticed. Perhaps because of this, one of the dining rooms nearest the end of unit was used less frequently, somewhat defeating the purpose behind the creation of these smaller family group spaces for eating.

Smaller home-like spaces are often advocated as a major improvement for residents, although evidence is usually derived from cross-sectional studies and the findings tend to be mixed (Chaudhury et al., Citation2018; Joseph et al., Citation2016). Our own findings add to existing literature by indicating some advantages and disadvantages of creating smaller groupings. However, the renovations examined in our project did not actually result in distinct, and completely separated spaces, as described in Smith et al. (Citation2010) study, and so the units still retained many institutional design elements (e.g., long hallways). These hallways could have benefits for providing good spaces for walking but are certainly unlike hallways in a typical house or apartment.

Noise

Clearly long-term care facilities would like to reduce institutional noises (carts, alarms, work conversations) that do not benefit residents (Graham, Citation2020). Based on objective measurements and subjective reports from staff, the units were quieter following the renovations in our study. Quieter places could have resulted from the smaller groupings of individuals in some spaces (e.g., dining rooms), and how the spaces (walls, ceilings, etc.) were finished. Resident vocalizations did not contribute to this; if anything, our behavioral mapping found that these behaviors, while infrequent, were higher after the renovations.

Noise levels have been associated with quality of life (Garcia et al., Citation2012; Garre-Olmo et al., Citation2012) and specific resident behaviors (e.g., social interaction, agitation, wandering; Chaudhury et al., Citation2018). Whereas staff reports of greater quiet in the units might have contributed to their more positive views of the renovations, the effects on residents are unclear. Social engagement did not increase, and aggression did not decrease. Movement on the units did decrease, but we cannot necessarily attribute all of that to resident wandering, because of the nature of our behavioral mapping methods.

Lighting

There were clear improvements in the lighting of the units in the dining/lounge spaces, in terms of brightness and color. Given that residents spend a considerable amount of time in these areas, this could be beneficial for their quality of life from a circadian rhythm perspective (Canazei et al., CitationIn Press; Goudriaan et al., Citation2021). In our study, there were no differences in before and after renovation daytime sleeping, so it is unclear whether the circadian effects of the lighting achieved their purported possibilities for residents.

While some researchers have suggested that more appropriate lighting could have positive impacts on residents with dementia (Chaudhury et al., Citation2018; Figueiro et al., Citation2014; Garre-Olmo et al., Citation2012; Joseph et al., Citation2016), a recent systematic review of randomized trials by Canazei et al. (CitationIn Press) found insufficient evidence for light therapies (including room light interventions) improving circadian activity or night time sleep parameters in persons with dementia. They also found that most intervention studies were of low quality due to the risk of bias and had small sample sizes. Another systematic review of lighting studies (randomized, non-randomized, qualitative, etc.) by Goudriaan et al. (Citation2021) found no conclusive evidence related to circadian rhythms or challenging behaviors.

Suitability of the design for residents of special care units

An issue that arose frequently for staff in our study was whether several aspects of the design were appropriate for the residents who live in the units. Several suggested that the residents’ advanced dementia states meant they would benefit less from environmental design changes. This may align with what Garcia et al. (Citation2012) found through focus groups with family and staff: “Human environments [e.g., consistent and sufficient staffing] were perceived to be more important than physical environments” for residents (Garcia et al., Citation2012, p. 753). Although our data might support this, it is also possible that stigmatizing attitudes toward individuals with cognitive impairment (Bond, Citation1992) shape care interactions to such an extent that residents are unable to benefit from design changes.

Limitations and strengths

Because of renovation-related delays, our examination of the renovated spaces did not include a new activity pavilion/courtyard, that was to facilitate spontaneous recreation. This might have shaped staff tendencies to report no changes in resident autonomy. However, this study is still valuable as many long-term care homes might want to make similar home-like renovations without having the ability to add very large indoor and outdoor spaces for recreational use by residents.

Many factors may have acted as confounding variables, making it difficult to discern whether certain changes or lack of changes, could be associated with the renovated spaces alone. For instance, a flexible policy for meals for residents was introduced, major staff upheavals occurred due to unprecedented reorganization of the health region, and staff training on interacting with residents was introduced. Also, because of the longitudinal nature of the study, there were also factors related to residents, such as new residents with possibly different characteristics after the renovations, and residents whose conditions might have progressed during the renovations. Having a comparable control group would have provided more rigor to the examination of resident and staff effects. A final limitation is that it was not possible to receive detailed feedback from the residents on specific elements of the design, so we had to rely on staff as proxies.

This study has many strengths including (1) pre and post-data were collected for several variables; (2) triangulation between multiple methods such as self-reported questionnaires, systematic observation of occupant behavior, objectively measured environmental outcomes, and the use of the staff surveys, to examine several aspects of their working conditions. Environmental effects on staff have been previously identified as a gap in this field (Joseph et al., Citation2016).

Conclusions

This ambitious renovation project to improve the living environment for residents living with advanced dementia and the staff who work with them was only partially successful in achieving its desired effects. While staff reported many positive aspects of the renovations for themselves (e.g., working conditions, staff communication technology), and residents (e.g., quality of life, renovation meeting residents’ needs), and objective measures indicated that noise levels were reduced and lighting was improved, few positive effects were directly identifiable for the residents. For example, we did not find that residents showed greater autonomy or activity levels. In addition, while exit-seeking behaviors were reduced, other reactive behaviors (e.g., aggression and vocalizations) were not. In terms of whether a more home-like environment was created, we received many positive comments from the staff, but others felt there were many tradeoffs in this particular renovation that prevented this from happening. While there is increasing interest in renovating long-term care spaces, there is a dearth of evidence on what specific design features can be linked to improved quality of life for residents and improved working conditions for staff. More high-quality longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether renovations have intended outcomes for both residents and staff of dementia care units.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba [E2016:084 (HS19958) and E2017:026 (HS20611)].

Author contributions

MMP drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. All authors were involved throughout the project in study design, data collection, and analysis, as well as interpretation of findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants for taking the time to be a part of this project. We also want to acknowledge the following people for their instrumental roles in data collection and/or data analysis: Ryan Coates, Tasha De Luca, Kelsey Grabowski, Kate Grisim, Bhuvan Mahana, Ellyn Madison, Natalia Reyes, and Desiree Theriault. We acknowledge the help of Rasheda Rabbani at the George & Fay Yee Centre for Healthcare Innovation at the University of Manitoba for statistical consulting services. Staff from the facility and an advisory committee from the facility were also of great assistance to the team in conducting this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bond, J. (1992). The medicalization of dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 6(4), 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/0890-4065(92)90020-7

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (n.d.-a). Dementia in long-term care [Report]. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (n.d.-b). RAI MDS 2.0 Canadian version. https://www.cihi.ca/en/manuals-and-forms-for-continuing-and-residential-care-interrai-assessors

- Canazei, M., Papousek, I., & Weiss, E. M. (In Press). Light intervention effects on circadian activity rhythm parameters and nighttime sleep in dementia assessed by wrist actigraphy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab168

- Chaudhury, H., Cooke, H. A., Cowie, H., & Razaghi, L. (2018). The influence of the physical environment on residents with dementia in long-term care settings: A review of the empirical literature. The Gerontologist, 58(5), e325–e337. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw259

- Chaudhury, H., Hung, L., Rust, T., & Wu, S. (2017). Do physical environmental changes make a difference? Supporting person-centered care at mealtimes in nursing homes. Dementia, 16(7), 878–896. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215622839

- Figueiro, M. G., Plitnick, B. A., Lok, A., Jones, G. E., Higgins, P., Hornick, T. R., & Rea, M. S. (2014). Tailored lighting intervention improves measures of sleep, depression, and agitation in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia living in long-term care facilities. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 1527–1537. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S68557

- Garcia, L., Hébert, M., Kozak, J., Sénécal, I., Slaughter, S., Aminzadeh, F., Dalziel, W., Charles, J., & Eliasziw, M. (2012). Perceptions of family and staff on the role of the environment in long-term care homes for people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(5), 753–765. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211002675

- Garre-Olmo, J., López‐Pousa, S., Turon-Estrada, A., Juvinyà, D., Ballester, D., & Vilalta-Franch, J. (2012). Environmental determinants of quality of life in nursing home residents with severe dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(7), 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04040.x

- Goudriaan, I., van Boekel, L. C., Verbiest, M., van Hoof, J., & Luijkx, K. G. (2021). Dementia enlightened?! A systematic literature review of the influence of indoor environmental light on the health of older persons with dementia in long-term care facilities. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 16, 909–937. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S297865

- Graham, M. E. (2020). Long-term care as contested acoustical space: Exploring resident relationships and identities in sound. Building Acoustics, 27(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1351010X19890478

- Joseph, A., Choi, Y. S., & Quan, X. (2016). Impact of the physical environment of residential health, care, and support facilities (RHCSF) on staff and residents: A systematic review of the literature. Environment and Behavior, 48(10), 1203–1241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515597027

- Lee, S. Y., Hung, L., Chaudhury, H., & Morelli, A. (2021). Staff perspectives on the role of physical environment in long-term care facilities on dementia care in Canada and Sweden. Dementia, 20(7), 2558–2572. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211003994

- Morgan-Brown, M., Newton, R., & Ormerod, M. (2013). Engaging life in two Irish nursing home units for people with dementia: quantitative comparisons before and after implementing household environments. Aging & Mental Health, 17(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.717250

- Newsham, G. R., Birt, B. J., Arsenault, C., Thompson, A. J. L., Veitch, J. A., Mancini, S., Galasiu, A. D., Gover, B. N., MacDonald, I. A., & Burns, G. J. (2013). Do ‘green’ buildings have better indoor environments? New evidence. Building Research & Information, 41(4), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2013.789951

- Smith, R., Mathews, R. M., & Gresham, M. (2010). Pre- and postoccupancy evaluation of new dementia care cottages. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 25(3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317509357735

- Westinghouse (n.d.). Lighting education – Color rendering index. https://www.westinghouselighting.com/lighting-education/color-rendering-index-cri.aspx