Abstract

Prior work has demonstrated that school connectedness correlates with several positive outcomes for adolescents. However, little is currently known about the efficacy of school connectedness in buffering emotionally maltreated youth from engaging in risk behaviors such as adolescent substance use. Guided by resilience theory, this study examined group differences in the protective role of school connectedness in decreasing the likelihood of substance use among emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated teens (N = 156). When considering the role of prior emotional maltreatment, results revealed that exposure to emotional maltreatment was associated with a lower likelihood of endorsing both lifetime alcohol and marijuana use (Alcohol B = −6.08, S.E. = 2.36, p = .01; Marijuana B = −8.31, S.E. = 2.90, p = .004). Results demonstrated that although school connectedness was associated with less reported substance use in non-emotionally maltreated teens (Alcohol B = −1.68, S.E. = .49, p = .001; Marijuana B = −2.81, S.E. = .72, p <.001), school connectedness was not associated with less substance use for emotionally maltreated teens in this sample. Findings demonstrate the importance of exploring the unique interplay between risk and protective factors in studies of adolescents and highlight the potential role of school connectedness in the prevention of substance use for some youth.

Exposure to emotional maltreatment (EM) at an early age has been shown to be associated with increased likelihood of engaging in risky, health-compromising behaviors during adolescence (Moran et al., Citation2004; Taillieu et al., Citation2016). Despite this fact, many adolescents exposed to stressful experiences, such as EM, achieve relatively positive outcomes and abstain from engaging in risk behaviors. These youth are commonly referred to in the literature as resilient and have been the focus of burgeoning empirical work over the past five decades (Garmezy, Citation1970; Masten & Barnes, Citation2018). Stemming from this research has emerged the resilience theory (Masten, Citation2018), a strengths-based theoretical framework that aims to highlight the processes in which protective factors weaken the relationship between exposure to adversity and negative outcomes. According to this framework, protective factors are components of an individual’s socioecological environment that directly weaken the negative impact of risk factors on behavioral outcomes through the process of a moderating effect (Zimmerman, Citation2013).

When attempting to understand which aspects of adolescents’ lives play a salient role in protecting them from engaging in risk behaviors, scholars have considered the school environment to be critical. As adolescents spend a significant portion of time at school (Roeser et al., Citation2000), it is often within the school setting that youth become engaged in prosocial activities, such as sports teams, clubs, and other extracurricular groups (Feldman & Matjasko, Citation2005). The school domain also has the capacity to provide students with positive relationships with adults (i.e., teachers, coaches, school staff) and peers, both of which have been linked with greater self-esteem and higher reported quality of life in teens (de Bruyn & van den Boom, Citation2005; Dexter et al., Citation2016; Helm, Citation2007; Kaplan & Flum, Citation2012; Knifsend et al., Citation2018; Verhoeven et al., Citation2019).

School connectedness

School connectedness involves the extent to which students experience feelings of belonging or caring at school and the degree to which students feel supported by their school community (Lohmeier & Lee, Citation2011; Osterman, Citation2000). Prior work has shown that greater school connectedness in adolescents has been associated with fewer conduct problems, increased prosocial behavior, and decreased likelihood of a range of risky behaviors, including substance use, violence perpetration, and sexual risk behavior (Bond et al., Citation2007; Brookmeyer et al., Citation2006; Loukas et al., Citation2010; McNeely et al., Citation2002; Oldfield et al., Citation2016). Despite evidence suggesting that school connectedness correlates with positive outcomes in the general adolescent population, there are certain negative early experiences that can be extremely powerful and transformative for youth development. It is unclear whether school connectedness may buffer at-risk adolescents, such as youth exposed to EM in childhood, from engaging in risk behavior.

Emotional maltreatment

The lack of understanding around the effectiveness of school connectedness in protecting emotionally maltreated youth from risk is concerning given the known consequences associated with this adverse experience (Watts et al., Citation2020). Emotional maltreatment (EM) has been defined as a pattern of behavior by a caregiver in which it is directly or indirectly communicated to the child that they are unloved, unwanted, flawed, endangered, or of value only in their ability to meet others’ needs (American Professional Society on Abuse of Children, Citation1995). When considering aspects that place teens at increased likelihood of engaging in risk behaviors, EM exposure has consistently been linked with negative outcomes, including depression (Hamilton et al., Citation2013), anxiety (Taillieu & Brownridge, Citation2013), and substance use (Rosenkranz et al., Citation2012).

Rates of EM during childhood are concerning, with approximately 14% of the U.S. population reporting previously experiencing EM perpetrated by parent or caregiver before the age of 18 (Taillieu et al., Citation2016). These rates are high relative to the prevalence rates of other forms of maltreatment in the U.S., such as exposure to physical (10.7%) or sexual abuse (7%) in childhood (American Society for the Positive Care of Children, Citation2018). Previous research has also demonstrated that compared to other forms of maltreatment, the psychiatric impacts of persistent EM may be the most pervasive (Burns et al., Citation2010; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Citation2009; Dye, Citation2019; Ju & Lee, Citation2018; Malik & Kaiser, Citation2016; Shaffer et al., Citation2009).

Despite the known prevalence of EM and the significant risk it poses to development, research has only recently focused on the unique individual impact that EM has on individuals. Prior studies investigating the effects of EM have largely examined EM in conjunction with other forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse), making it difficult to understand its unique consequences (Vahl et al., Citation2016; Watts et al., Citation2020). Another major limitation of current literature is that few studies have aimed to understand which protective factors may be most salient in buffering emotionally maltreated youth from risk. This is a major concern, as exposure to EM has been linked to a host of negative psychiatric, behavioral, and relational outcomes (Vahl et al., Citation2016; Watts et al., Citation2020) and has often shown to interfere with the cognitive and socioemotional development of youth (Hornor, Citation2012). Given the potential detrimental impact of EM, the protective factors that are successful in buffering the general population of teens from risk may have a different level of efficacy in protecting emotionally maltreated youth. For this reason, research exploring the efficacy of protective factors in mitigating risk specifically for emotionally maltreated youth is necessary to inform prevention and intervention efforts aimed at buffering youth from the impact of EM.

EM, school connectedness, and adolescent substance use

When examining the negative consequences associated with EM in childhood, substance use is one of the more frequently explored outcomes. It is pertinent to explore substance use in adolescence, as early substance use has been shown to have a wide range of negative implications on the physical and mental health of young people, including increased aggression, decreased academic performance, higher likelihood of delinquency, and greater likelihood of subsequent substance abuse in adulthood (CDC, Citation2014; Kandel, Citation1982; Moran et al., Citation2004; Rosenkranz et al., Citation2012). The link between exposure to EM and adolescent substance use has been well established and is a major public health concern (Moran et al., Citation2004; Tonmyr et al., Citation2010; Yoon et al., Citation2017). While EM has been shown to increase the likelihood of substance use in adolescence, research has shown that young people who exhibited high levels of school connectedness are significantly less likely to engage in alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substance use during adolescence than their peers with less connection to school (CDC, Citation2018a, Citationb).

To date, there has not been adequate research aimed at understanding the protective factors that decrease emotionally maltreated teens’ likelihood of engaging in substance use. Although adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) more generally have been shown to be associated with increased substance use among adolescents, less is known about the unique individual impacts of EM on substance use in early adolescents. Furthermore, although protective factors, such as school connectedness, have been associated with several positive outcomes, to date no research has explored whether there are group differences in how school connectedness is able to help buffer emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated teens from engaging in substance use. Exploring these group differences in the efficacy of school connectedness as a buffer against substance use will be instrumental in informing whether this is a construct that would be worth implementing in prevention and intervention efforts for supporting emotionally maltreated youth in abstaining from substance use.

Current study

Guided by the resilience theory, the current study aims to fill gaps in current literature by 1) exploring the links between EM, substance use, and school connectedness among a sample of urban adolescents and 2) examining group differences in the potential protective role of school connectedness in decreasing the likelihood of lifetime substance use among emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreatment urban adolescents.

Based on previous literature, it was hypothesized that for Aim 1 there would be a positive association between EM and substance use, such that adolescents who endorse experiencing EM would be significantly more likely to report using both alcohol and marijuana compared to teens who did not endorse EM. It was also hypothesized that there would be a negative association between EM and school connectedness, in that teens who endorsed EM would report lower school connectedness. Next, it was hypothesized that there would be a negative relationship between school connectedness and substance use for both emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated youth, such that adolescents who report greater school connectedness would be less likely to report both alcohol and marijuana use compared to teens who report lower levels of school connectedness. For Aim 2 it was hypothesized that school connectedness would significantly moderate the relationship between EM and substance use, such that higher school connectedness in both emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated teens would be associated with a decreased likelihood of lifetime alcohol and marijuana use.

Method

Participants and procedures

Data were collected through a cross-sectional study of youth residing in a large New England city. This study aimed to identify individual and community-based factors that promote resilience to violence among urban youth. Data were collected from 156 urban youth (62.4% male; 34.4% female; 2.6% other). For the purposes of the current study, urban youth are defined as individuals between the ages of 14 and 18 living in the context of a population-dense city. On average, participants were 15 years old (M = 15.13, SD = 1.27). Representative of urban youth in New England, approximately 46.1% of the sample identified their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latinx. In terms of race, participants were encouraged to select all racial backgrounds with which they identify. Approximately 71% of the sample identifying as African American/Black, 7% identifying as Asian, 2.6% identifying as White/Caucasian, 2.6% identifying as Native American, and 24% reported their racial identity as Other (see ).

Table 1. Demographics of study sample.

Participants were recruited from four distinct community-based, after-school organizations. To be eligible for the current study, youth must have been taking part in an after-school program from one of the four participating community-based organizations. Youth were included in the study if they were between the ages of 14 and 18 years old and were proficient in reading in English. Parents/guardians were provided with a full description of the study and an opportunity to have their child “opt out” of participating in the surveys, similar to the consent procedures used for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Brown & Grumet, Citation2009; CDC, Citation2020). All participants provided their assent before completing an anonymous paper-pencil survey and were compensated $40 for their participation.

Measures

Demographics

Adolescent participants reported on demographic information including age, race, ethnicity, identified gender, and socioeconomic status.

Emotional maltreatment

To assess exposure to EM in childhood, an item from the ACEs survey was utilized: “Did you often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special?” (Felitti et al., Citation1998). Participants responded with “yes” or “no.”

Substance use

To assess adolescent substance use, two items from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBS; CDC, Citation2008) were utilized. The items used for the current study included “during your life, on how many days have you had at least one drink of alcohol?” and “during your life, how many times have you used marijuana?” To determine lifetime use of substances, responses were dichotomized to reflect teens who have never used alcohol or marijuana (reported no past use) and teens who have ever used alcohol or marijuana in their lifetime (reported any past alcohol or marijuana use).

School connectedness

To assess school connectedness, the School Connectedness Scale (SCS; Lohmeier & Lee, Citation2011) was utilized. The SCS consists of 57 items and aims to measure the extent to which individuals feel supported and connected to their school community. Adolescents responded on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 = not at all true, to 5 = completely true. Higher scores on the SCS indicate higher levels of school connectedness. Internal consistency in the current sample was found to be acceptable (α = .93).

Data analysis

Prior to conducting analyses, data were inspected. Missing data ranged from 0% to 9%; two youth (1.3%) were missing data on the variable that assessed EM exposure, six youth (3.8%) were missing data assessing lifetime history of alcohol use, and fourteen youth (9.0%) were missing data assessing lifetime history of marijuana use. The scale assessing school connectedness was not missing any data. As the total missingness for each measure of interest was <10%, missing data were addressed using listwise deletion.

To explore Aim 1, t-tests were conducted to examine the relationship between continuous variables (i.e., school connectedness) and dichotomous variables (i.e., emotional maltreatment, alcohol use, marijuana use). Chi squares were used to examine the relationships between two dichotomous variables (EM and substance use variables). To explore Aim 2, two separate 4-step hierarchical logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether EM exposure, school connectedness, and their interaction variable, were associated with lifetime alcohol use, as well as lifetime marijuana use. For both models, in Step 1, race and socioeconomic status were entered as covariates, as theory from past research demonstrated that these covariates play an important role in impacting endorsement of school connectedness and substance use (Eisenberg et al., Citation2009; Gerra et al., Citation2020; Rice et al., Citation2008). In Step 2, school connectedness was entered. In Step 3, EM was entered. In Step 4, the interaction School Connectedness x EM was entered.

Results

Results indicated that teens in this sample experienced an average number of 3.2 total ACEs in their lifetime (SD = 2.03, range = 8), with 31.4% of participants endorsing EM specifically. Findings also showed that 51.7% of participants reported ever using alcohol in their lifetime and 52.9% of participants reported ever using marijuana in their lifetime. In this sample, the mean school connectedness score was 3.28 (SD = .57, range = 4).

For Aim 1, t-tests revealed a significant difference in school connectedness between teens who endorsed using substances (Alcohol M = 3.14, SD = .47; t(155) = 25.45, p<.001) (Marijuana M = 3.07, SD = .43; t(155) = 37.84, p<.001) and teens who did not endorse using substances (Alcohol M = 3.45, SD = .62; t(155) = 25.45, p<.001) (Marijuana M = 3.51, SD = .59; t(155) = 37.84, p<.001). As anticipated based on previous literature, greater school connectedness was linked with less lifetime substance use. Also as expected, youth who endorsed EM reported significantly lower levels of school connectedness (M = 3.15, SD = .578) than teens who did not endorse EM (M = 3.35, SD = .56; t(152) = 2.014, p = .046). Lastly, partially supporting hypotheses, total number of ACEs was positively associated with substance use (Alcohol M = 3.82, SD = 2.47.; t(155) = -31.20, p<.001) (Marijuana M = 4.01, SD = 1.69; t(155) = −38.35, p<.001), suggesting that the more total ACEs a teen experienced, the greater their likelihood of engaging in substance use. Interestingly, contrary to expected findings, Chi square analyses revealed a significant relationship between EM and substance use in the negative direction, demonstrating that teens who endorsed EM were found to be less likely to endorse engaging in lifetime substance use (Alcohol Use: X2(1, N = 156) = 67.1, p<.001; Marijuana Use: X2(1, N = 156) = 67.1, p < .001).

Alcohol use

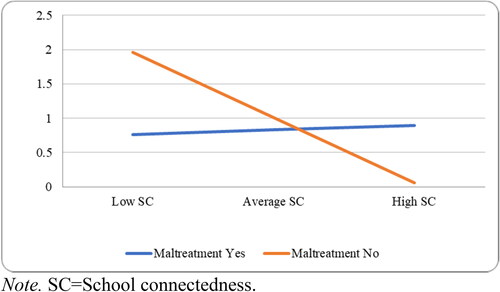

For Aim 2, results of the logistic regression model predicting likelihood of lifetime alcohol use indicated that endorsement of EM (B = −6.08, S.E. = 2.36, p = .01) and greater school connectedness (B = −1.68, S.E. = .49, p < .001) were both associated with a lower likelihood of lifetime alcohol use. In terms of the interaction effect, the interaction between school connectedness and EM yielded significant findings (B = 1.80, S.E. = .71, p = .012) (), suggesting that greater school connectedness decreases the likelihood of alcohol use in teens who were not emotionally maltreated ().

Figure 1. Interaction effect: emotional maltreatment and school connectedness on alcohol use.

Note. SC = school connectedness.

Table 2. Summary of logistic regression analysis for predicting alcohol use.

Marijuana use

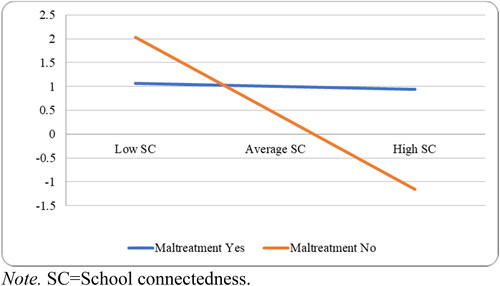

Results of the logistic regression model predicting lifetime marijuana use demonstrated that endorsement of EM (B = −8.31, S.E. = 2.90, p = .004) and greater school connectedness (B = −2.81, S.E. = .72, p <.001) were associated with a lower likelihood of lifetime marijuana use. Again, there was also a significant interaction between school connectedness and EM (B = 2.70, S.E. = .89, p = .002) (), in which greater school connectedness decreased like likelihood of marijuana use for teens who were not emotionally maltreated ().

Figure 2. Interaction effect: emotional maltreatment and school connectedness on marijuana use.

Note. SC = school connectedness.

Table 3. Summary of logistic regression analysis for predicting marijuana use.

The association between school connectedness and substance use was stronger in the expected negative direction for teens who had no history of EM, however it is important to note that school connectedness did not have a significant moderating effect on decreasing the likelihood of substance use for teens who endorsed EM. and show regression coefficients, Wald statistics, odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals for odds ratios for both regression models, while and show the plotted interaction effects.

Discussion

The current study identified whether there are group differences in the efficacy of school connectedness in buffering emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated teens from engaging in alcohol and marijuana use. Many of the bivariate relationships revealed in this sample were consistent with hypotheses based on prior literature in that greater school connectedness was associated with lower likelihood of alcohol and marijuana use and teens who endorsed EM also reported lower levels of school connectedness. The unique impact that EM has on risk behavior and youths’ abilities to initiate and maintain connections with others supported our decision to explore group differences in the moderating role of school connectedness in youth with and without exposure to EM.

The expected relationship between school connectedness and substance use was revealed, in that greater school connectedness was correlated with decreased lifetime alcohol and substance use. The results demonstrated that, as anticipated, school connectedness had a significant moderating impact in buffering non-emotionally maltreated youth from engaging in substance use. Per existing research demonstrating emotional abuse may be unique in the ways in which it impacts youth, our findings revealed an unexpected relationship wherein teens who endorsed experiencing EM showed decreased likelihood of engaging in substance use. Additionally, although school connectedness demonstrated a moderating role in buffering non-emotionally maltreated youth from substance use, there was a non-significant association between school connectedness and substance use in emotionally maltreated youth.

Consistent with results from prior literature, findings from the current study suggest that teens in urban settings are engaging in substance use at concerningly high rates (51.7% reported alcohol use and 52.9% reported marijuana use). The frequency in which EM was endorsed by participants in the current sample (31.4%) was higher than rates reported in community samples of youth (approximately 14%) (Taillieu et al., Citation2016), yet were consistent with reported rates of EM in other urban samples (Arata et al., Citation2007; Trickett et al., Citation2009).

This study also revealed expected positive associations between total number of ACEs endorsed by adolescents in the current study and their history of lifetime alcohol and marijuana use. However, contrary to expectations, EM alone was negatively associated with lifetime alcohol and marijuana use. One explanation for this unexpected finding lies in the complex relationship between and among different forms of ACEs. Prior research has noted significant overlap and frequent intercorrelation among individual ACEs. Given that EM commonly co-occurs in conjunction with other ACEs, it may be that the combination of multiple early adversities that contributes to substance use, rather than EM independently.

For Aim 1 hypotheses, it was anticipated that there would be an association between EM and adolescent substance use, such that adolescents who report EM will also report an increased likelihood of using both alcohol and marijuana compared to teens who do not report EM. While findings demonstrate somewhat unanticipated relationships, the value of the current study is that it highlights important group differences between emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated youth with respect to school connectedness and substance use. The novel results suggest that while school connectedness is associated with decreased likelihood of substance use for youth who were not emotionally maltreated, the unique nature and mechanisms involved in experiencing EM seems to impact the efficacy of school connectedness in providing a similarly protective role for maltreated youth. It is also important to consider the potential confounding variables that may be impacting emotionally maltreated youths’ ability to be protected by school connectedness in the same way as their peers. For example, as EM is often linked with greater depression in youth, the current findings may be capturing the internalizing nature of this particular sample of teens.

With respect to the negative association between school connectedness and substance use, this hypothesis was supported in that higher school connectedness was associated with decreased likelihood of teens endorsing alcohol and marijuana use. This is consistent with prior research and demonstrates that although school connectedness may vary in its efficacy for buffering certain subgroups of teens from risk, overall, it has demonstrated expected results in its association with decreased overall substance use in this sample of urban teens. When conceptualizing school connectedness as a continuous variable, it is important to note that in general, findings revealed that the greater a teen’s reported school connectedness, the lower their likelihood of endorsing substance use. These findings provide a novel contribution to extant literature, in that while this expected and well-documented relationship between school connectedness and substance use is present for teens without the powerful experience of EM in childhood, there are certain experiences youth undergo that have the ability to impact how effective school connectedness may protect them from risk.

An important factor to consider when interpreting these findings is that this sample was recruited explicitly from community-based afterschool programs. Past research has posited that participation in afterschool programs has the potential to improve teens’ social skills, self-esteem, emotional and behavioral adjustment, and school performance (Apsler, Citation2009; Durlak & Weissberg, Citation2007). Perhaps there is a component of the afterschool programs from which youth were recruited that may have an impact on emotionally maltreated teens above what school connectedness may offer, which is consequently contributing to their decreased likelihood of engaging in substance use.

It is possible that there are other confounding variables that have not been accounted for in the regression models that are playing a contributing role in these analyses. For example, increased popularity in adolescence has been shown to increase the likelihood for substance use (Fallu et al., Citation2011; Moody et al., Citation2011). As EM has been associated with several interpersonal challenges in youth, it is plausible that relational difficulties may be impacting the extent to which teens who have experienced EM are able to form strong attachments with peers. This may impact the opportunities teens have for engaging in substance use, as youth typically engage in substance use within the context of peer groups (Ennett et al., Citation2006; Valente et al., Citation2007).

Another potential explanation for these unexpected findings could be that exposure to EM causes challenges for youth to adequately establish a sense of school connectedness. It has been well established within child abuse literature that exposure to EM increases teens’ likelihood for experiencing a range of relational challenges, including a marked difficulty establishing close relationships (Reyome, Citation2010; Riggs & Kaminski, Citation2010). The profound negative impact that EM has on teens may make it exceedingly difficult for them to connect with others, such as individuals within the school community (e.g., peers, teachers, staff). A recent systematic review found that EM was associated with multiple negative outcomes in youth that have the capacity to adversely impact their functioning within the school environment including impulsivity, poor academic achievement, inattention, reduced literacy, and numerical skills difficulties (Maguire et al., Citation2015). While emotionally maltreated teens may report connectedness to school, their ability to initiate and maintain relationships at school may be inherently different than the level of connectedness that non-emotionally maltreated peers are establishing.

Strengths and limitations

By utilizing the resilience theory as a guiding framework, this study takes a strengths-based approach to identifying components of youth’s lives that promote increased well-being and buffer teens from engaging in risk behaviors. This study also provides a novel shift from the vast literature primarily examining the risks associated with maltreatment, thereby ignoring potential protective factors that may protect youth from the associated risks. Given that the majority of adolescents in the United States are members of a school community, the exploration of school connectedness as a protective factor is a component of teens’ lives that is generalizable and applicable to most youth. Thus, understanding the potential protective role of school connectedness in buffering emotionally maltreated youth from risk can be informative in creating school-based initiatives to promote connectedness within the school community for at-risk teens. This study examined the unique consequences of EM as its own entity, which is steering away from many studies that often assess the cumulative impact of multiple ACEs and addresses a major gap in resilience and childhood adversity literature. Lastly, the current study utilizes a widely diverse sample with respect to race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. This is a strength in that this sample is largely representative of an urban sample of teens, which allows for greater generalizability of findings.

Despite these strengths, there are limitations to note. First, the measures used in this study were self-reported and administered via pen and paper survey. This administration method lends itself to increased potential for human error in data collection and entry. Additionally, EM and substance use (alcohol and marijuana use) were each measured utilizing a single item. Future researchers would benefit from utilizing more comprehensive measures of EM and substance use to determine the degree to which EM and substance use was present, rather than assessing it as the presence or absence of EM or lifetime substance use. Lastly, while this study examined the impact of EM on youth, we did not account for the impact of other types of ACEs and how these other potentially co-occurring ACEs may be contributing to the relationship between EM and substance use. While there is value in accessing the unique impact of specific types of maltreatment, given that ACEs are shown to frequently co-occur (Felitti et al., Citation1998), accounting for exposure to other types of ACEs should be considered for future research.

Future directions and clinical implications

The current findings highlight the need for further exploration of pertinent protective factors for both emotionally maltreated and non-emotionally maltreated urban youth. Though school connectedness was not found to be a significant moderator for emotionally maltreated youth in this sample, it was a salient protective factor for buffering non-maltreated urban youth from engaging in substance use. Through the lens of the resilience theory, this may suggest that there is a distinct difference in the mechanisms through which protective factors are able buffer maltreated and non-maltreated youth from risk behavior. Future empirical work guided by the resilience theory framework would benefit from exploring and identifying which factors and mechanisms are salient in protecting both maltreated and non-maltreated youth from risk.

In terms of prevention and intervention efforts, results suggest that while school connectedness may be a viable target for protecting some youth from risk, it may be difficult for youth who experience EM to establish school connectedness in the same ways as their non-emotionally maltreated peers. It may be beneficial to further explore how to promote school connectedness in this subsample of maltreated youth. One avenue that may help to foster school-based protective factors for maltreated youth would be a collaboration between the child protective services and education departments; given that child protective authorities oversee programs for maltreated children, their expertise, paired with the resources available through the education departments, would likely be beneficial in promoting school-based protective factors for these youth. Future research would also benefit from identifying additional unique protective factors that help to buffer emotionally maltreated youth from engaging in risk behaviors.

Ethical standards and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at Northeastern University and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. For the informed consent process, parents/guardians were provided with a full description of the study and an opportunity to have their child “opt out” of survey participation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Madeline C. Manning

Madeline C. Manning, Ph.D. completed her doctoral degree in Counseling Psychology at Northeastern University in Boston, MA. She is currently a post-doctoral fellow in pediatric neuropsychology at Massachusetts General Hospital LEAP Program in Boston, MA.

Crosby A. Modrowski

Crosby A. Modrowski, Ph.D. graduated from the University of Utah in 2019. She currently works as a research scientist at Rhode Island Hospital and is also a consulting psychologist at the Rhode Island Family Court.

Daniel P. Aldrich

Daniel P. Aldrich, Ph.D. completed his doctoral degree in Government at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA. He is currently co-director of the Global Resilience Institute, Director of the Masters in Science in Security and Resilience Studies Program, and Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at Northeastern University in Boston, MA.

Christie J. Rizzo

Christie J. Rizzo, Ph.D. completed her doctoral degree in Clinical Psychology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, CA. She is currently Director of Counseling Psychology programs and Associate Professor of Applied Psychology in Bouve College of Health Sciences at Northeastern University in Boston, MA.

References

- American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. (1995). Psychosocial evaluation of suspected psychological maltreatment in children and adolescents. Cultic Studies Journal, 13(2), 153–170. https://pubhtml5.com/hday/tslz/basic/.

- American Society for the Positive Care of Children. (2018). https://americanspcc.org/child-abuse-statistics/.

- Apsler, R. (2009). After-school programs for adolescents: A review of evaluation research. Adolescence, 44(173), 1–19.

- Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., & O’Brien, N. (2007). Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(4), 393–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.006

- Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., & Patton, G. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), 357.e9–357.e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013

- Brookmeyer, K. A., Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: A multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 35(4), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_2

- Brown, M. M., & Grumet, J. G. (2009). School-based suicide prevention with African American youth in an urban setting. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012866

- Burns, E. E., Jackson, J. L., & Harding, H. J. (2010). Child maltreatment, emotion regulation, and posttraumatic stress: The impact of emotional abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19(8), 801–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2010.522947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/yrbss. Last updated November 22, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2014). ACEs study: violence prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/. Published April 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018a). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/adolescents.htm/. Published July 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018b). School connectedness. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/school_connectedness.htm. Published August 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). Youth risk behavior surveillance system. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm/. Last updated August 20, 2020.

- Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2009). Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. In E. A. Skinner, & M. J. Zimmer-Gembeck (Eds.), Coping and the development of regulation. New directions for child and adolescent development (2nd ed., Vol. 124, pp. 47–59). Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.242

- de Bruyn, E. H., & van den Boom, D. C. (2005). Interpersonal behavior, peer popularity and self-esteem in early adolescence. Social Development, 14(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00317.x

- Dexter, A. L., Lavigne, A. L., & de la Garza, T. O. (2016). Communicating care across culture and language: The student–teacher relationship as a site of socialization in public schools. Humanity & Society, 40(2), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616643882

- Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://www.lions-quest.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/AfterSchoolProgramsStudy2007.pdf.

- Dye, H. L. (2019). Is emotional abuse as harmful as physical and/or sexual abuse? Journal of Child Adolescent Trauma, 13(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00292-y

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. B. (2009). Mental health and academic success in college. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2191

- Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., Hussong, A., Faris, R., Foshee, V. A., Cai, L., & DuRant, R. H. (2006). The peer context of adolescent substance use: findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00127.x

- Fallu, J. S., Brière, F. N., Vitaro, F., Cantin, S., & Borge, A. I. (2011). The influence of close friends on adolescent substance use: Does popularity matter? Jahrbuch Jugendforschung, 10, 235–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93116-6_9

- Feldman, A. F., & Matjasko, J. L. (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 159–210. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075002159

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Garmezy, N. (1970). Process and reactive schizophrenia: Some conceptions and issues. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2(30), 74. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/1.2.30

- Gerra, G., Benedetti, E., Resce, G., Potente, R., Cutilli, A., & Molinaro, S. (2020). Socio- economic status, parental education, school connectedness and individual socio-cultural resources in vulnerability for drug use among students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041306

- Hamilton, J. L., Shapero, B. G., Stange, J. P., Hamlat, E. J., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2013). Emotional maltreatment, peer victimization, and depressive versus anxiety symptoms during adolescence: Hopelessness as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(3), 332–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.777916

- Helm, C. (2007). Teacher dispositions affecting self-esteem and student performance. Clearing House, 80(3), 109–110. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.80.3.109-110

- Hornor, G. (2012). Emotional maltreatment. Journal of Pediatric Health Care: Official Publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners, 26(6), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2011.05.004

- Ju, S., & Lee, Y. (2018). Developmental trajectories and longitudinal mediation effects of self- esteem, peer attachment, child maltreatment and depression on early adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.015

- Kandel, D. B. (1982). Epidemiological and psychosocial perspectives on adolescent drug use. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 21(4), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60936-5

- Kaplan, A., & Flum, H. (2012). Identity formation in educational settings: A critical focus for education in the 21st century. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37(3), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.01.005

- Knifsend, C. A., Camacho-Thompson, D. E., Juvonen, J., & Graham, S. (2018). Friends in activities, school-related affect, and academic outcomes in diverse middle schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(6), 1208–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0817-6

- Lohmeier, J. H., & Lee, S. W. (2011). A school connectedness scale for use with adolescents. Educational Research and Evaluation, 17(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2011.597108

- Loukas, A., Roalson, L. A., & Herrera, D. E. (2010). School connectedness buffers the effects of negative family relations and poor effortful control on early adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00632.x

- Maguire, S. A., Williams, B., Naughton, A. M., Cowley, L. E., Tempest, V., Mann, M. K., Teague, M., & Kemp, A. M. (2015). A systematic review of the emotional, behavioral and cognitive features exhibited by school-aged children experiencing neglect or emotional abuse. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(5), 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12227

- Malik, S., & Kaiser, A. (2016). Impact of emotional maltreatment on self-esteem among adolescents. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 66(7), 795–798.

- Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12255

- Masten, A. S., & Barnes, A. J. (2018). Resilience in children: Developmental perspectives. Children, Basel, Switzerland, 5(7), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5070098

- McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting student connectedness to school: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. The Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x

- Moody, J., Brynildsen, W. D., Osgood, D. W., Feinberg, M. E., & Gest, S. (2011). Popularity trajectories and substance use in early adolescence. Social Networks, 33(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2010.10.001

- Moran, P. B., Vuchinich, S., & Hall, N. K. (2004). Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002

- Oldfield, J., Humphrey, N., & Hebron, J. (2016). The role of parental and peer attachment relationships and school connectedness in predicting adolescent mental health outcomes. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12108

- Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367., https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003323

- Reyome, N. (2010). Childhood emotional maltreatment and later Intimate relationships: Themes from the empirical literature. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 19(2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770903539664

- Rice, M., Duck-Hee, K., Weaver, M., & Howell, C. (2008). Relationship of anger, stress, and coping with school connectedness in fourth-grade children. The Journal of School Health, 78(3), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00277.x

- Riggs, S. A., & Kaminski, P. (2010). Childhood emotional abuse, adult attachment, and depression as predictors of relational adjustment and psychological aggression. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 19(1), 75–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770903475976

- Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (2000). School as a context of social- emotional development: A summary of research findings. The Elementary School Journal, 100(5), 443–471. https://doi.org/10.1086/499650

- Rosenkranz, S. E., Muller, R. T., & Henderson, J. L. (2012). Psychological maltreatment in relation to substance use problem severity among youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(5), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.01.005

- Shaffer, A., Yates, T. M., & Egeland, B. R. (2009). The relation of emotional maltreatment to early adolescent competence: Developmental processes in a prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.005

- Taillieu, T. L., & Brownridge, D. A. (2013). Aggressive parental discipline experienced in childhood and internalizing problems in early adulthood. Journal of Family Violence, 28(5), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9513-1

- Taillieu, T. L., Brownridge, D. A., Sareen, J., & Afifi, T. O. (2016). Childhood emotional maltreatment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative adult sample from the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.07.005

- Tonmyr, L., Thornton, T., Draca, J., & Wekerle, C. (2010). A review of childhood maltreatment and adolescent substance use relationship. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 6(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.2174/157340010791792581

- Trickett, P. K., Mennen, F. E., Kim, K., & Sang, J. (2009). Emotional abuse in a sample of multiply maltreated, urban young adolescents: Issues of definition and identification. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.003

- Vahl, P., Van Damme, L., Doreleijers, T., Vermeiren, R., & Colins, O. F. (2016). The unique relation of childhood emotional maltreatment with mental health problems among detained male and female adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 62, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.10.008

- Valente, T. W., Ritt-Olson, A., Stacy, A., Unger, J. B., Okamoto, J., & Sussman, S. (2007). Peer acceleration: Effects of a social network tailored substance abuse prevention program among high-risk adolescents. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 102(11), 1804–1815. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01992.x

- Verhoeven, M., Poorthuis, A. M. G., & Volman, M. (2019). The role of school in adolescents’ identity development: A literature review. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9457-3

- Watts, J. R., O’Sullivan, D., Panlilio, C., & Daniels, A. D. (2020). Childhood emotional abuse and maladaptive coping in adults seeking treatment for substance use disorder. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 41(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12073

- Wekerle, C., Leung, E., Wall, A. M., MacMillan, H., Boyle, M., Trocmé, N., & Waechter, R. (2009). The contribution of childhood emotional abuse to teen dating violence among child protective services-involved youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.006

- Yoon, S., Kobulsky, J. M., Yoon, D., & Kim, W. (2017). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent substance use: The roles of posttraumatic stress symptoms and mother-child relationships. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.035

- Zimmerman, M. A. (2013). Resiliency theory: A strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Education & Behavior : The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 40(4), 381–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113493782