ABSTRACT

Waste segregation is an important component in the waste management chain as it makes it possible to realize effective Reuse, Recycling and Recovery (RRR). Unfortunately, it has received little attention and is normally informally practiced in most developing countries (DC). It is also affected by lack of awareness, weak regulatory frameworks and enforcement, lack of economic incentive and a low priority in planning. This study was conducted in Kimara ward in Dar es Salaam city in Tanzania. It employed interviews, household surveys and waste measurements, to establish the potential for RRR as well as the underlying factors that are related to the community perspectives and strategies for enhancement of RRR. Results show that the generation rate was 0.53 kg/Cap.day and the main type was food waste (>60% of the composition by weight). The study revealed further that reuse and recycling of plastics, electronics and metals are informally practiced and the selling chain is from household to waste collectors to recycling centers and finally to industries. The potential for RRR was found to be high but, it is affected by lack of facilities, inadequate enforcement of the policy as well as lack of awareness and strategies for its promotion. Community perceptions on what could be done to improve segregation include the provision of facilities for waste segregation and financial returns to the community from recycling business could promote RRR. Formulation of strategies to formalize and mainstream RRR into training programmes and adequate enforcement mechanisms are some of the recommended policy actions.

1. Introduction

Proper Solid Waste Management (SWM) is crucial for environmental protection and the well-being of human beings. If waste is improperly managed may contaminate soils, water and air thereby affecting the quality of life. Improperly managed waste may also create nuisance and make human beings feel uncomfortable. The main components of SWM are generation, collection, transportation and disposal. Generation of waste is an important stage where by source reduction strategies can be implemented. However for effective management there is a growing interest for waste minimization through reuse and recycling which necessitates incorporation of waste segregation in the waste management stream (Oberlin, Citation2013). When done properly, source waste segregation may reduce volumes of waste to be handled which would ultimately improve the collection and disposal efficiency. In addition, waste segregation at source may ease handling and processing, enhance the potential for resource recovery, fosters reuse and recycling and reduce operational costs. Literature has reported waste segregation as key for effective recycling program. Stoeva & Alriksson, (Citation2017) stress the importance of waste segregation at household level and underscore its contribution in fostering high rates of recycling and reuse. Furthermore literature indicates that a sustainable recycling programs among other factors highly depend on waste segregation (Troschinetz & Mihelcic, Citation2009). In fact, scholars express that waste segregation is an important step in a road map to circular economy (Maletz et al., Citation2018).

According to Armijo De Vega et al. (Citation2008) and Donnini Mancini et al. (Citation2007), waste reuse, recycling and recovery (RRR), if well planned and managed, can reduce the amount of waste to be disposed of by up to 65% of the total waste generated. Literature indicates that waste recovery and reuse also can yield direct economic benefits (Batool et al., Citation2008; A. Kumar et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2012) and help in the protection of public health and environment (A. Kumar et al., Citation2017; Saphores et al., Citation2012). With effective recycling program whereby all the recyclables are taken on board, it is possible to significantly reduce the volumes of waste. For instance, studies indicate that recycling of e-waste only (the fastest growing waste stream in the world) is reported to reduce the volumes of waste significantly (Li et al., Citation2015; Saphores et al., Citation2012). Recycling of plastics wastes, the other large waste stream, is also mentioned to reduce waste volume (Al-Salem et al., Citation2009). Waste reuse and recycling can contribute to income generation and may help to reduce complications in handing and disposing of huge volume of solid wastes (Matter et al., Citation2013; Wilson et al., Citation2006). Therefore, incorporating waste segregation at generation point, collection and disposal stages can promote SW reuse and recycling and may lead to economic and environmental benefits.

Recognizing the importance of waste segregation and recycling, many countries have put in place strategies to improve this practice. Some of these strategies involve policy reforms, review of governance structures and improving public awareness. In developed countries for instance, RRR has been promoted through development of policies and legislation, regional coordination across local jurisdictions and innovative governance structures. Some of the real examples are recycling of wood and electronics in the United States (Falk & McKeever, Citation2004; Kang & Schoenung, Citation2005; A. Kumar et al., Citation2017) and the recycling of plastics and packaging and demolition of waste in Europe (Bing et al., Citation2016; Da Cruz et al., Citation2014; Jeffrey, Citation2011). However, in many DC, waste segregation and recycling has not received adequate attention by the waste management authorities. Thus it is only informally practiced (Chi et al., Citation2011; Wilson et al., Citation2006). This suggests a lack of awareness (Babaei et al., Citation2015), weak regulatory frameworks (Yu et al., Citation2010), lack of economic incentives (Suttibak & Nitivattananon, Citation2008) and lack of priority in planning processes and enforcement (Al-Maaded et al., Citation2012; Darby & Obara, Citation2005; Skinner et al., Citation2010).

In terms of literature, many studies on waste segregation have been undertaken globally. It is clear that waste segregation has a substantial contribution to effective waste management. Literature indicates that waste segregation has a contribution to effective hospital waste management (K. M. Johnson et al., Citation2013), can lead to enhanced energy recovery from waste (Rajkamal et al., Citation2014); may improve recycling process (Stoeva & Alriksson, Citation2017). For successive waste segregation and recycling, effective policies on waste segregation have been pointed to be key (Matsumoto, Citation2011). In DC waste segregation has been lagging behind due to low level of awareness (Babazadeh et al., Citation2020; B. S. Kumar et al., Citation2017), lack of willingness (Gyimah et al., Citation2019) and low financing (S. Kumar et al., Citation2017) to mention just a few. However, literature from DC specifically from sub-Saharan Africa is still inadequate specifically with regard to best models for implementing recycling program, the limitations and potentials for waste segregation and recycling, strategies for behavioral change and the feasible technologies for RRR. Tanzania is one of such countries with limited information on waste segregation and recycling. Despite the presence of several studies on solid waste management in Tanzania, there is limited information on factors and reasons for non-segregation of waste at household level and possible strategies for enhancing waste segregation and recycling.

Studies on waste management practices indicate that waste segregation in many DC including Tanzania is not adequately implemented but instead waste is all mixed up (Agbefe et al., Citation2019). Lack of waste segregation at source and on the subsequent stages of waste management has been the main challenge. As a result, collection of waste and recycling becomes inefficient. Mixing of waste complicates handling and separation of the recyclables becomes difficult. Lack of recycling denies the opportunity for waste volume reduction and necessitates a significant proportion of the generated waste to be collected, transported and disposed of.

This article presents factors that contribute to inadequate waste segregation and recycling by highlighting the level of the practice, and discusses the community perceptions on what can be done to enhance waste segregation. It examines waste segregation practices including the potential for resource recovery as observed in Dar es Salaam, the commercial capital of Tanzania. It identifies the existing gaps in practice, policy frameworks and management aspects and provides recommendations for possible policy changes.

2 Methodology

2.1 Description of the study area

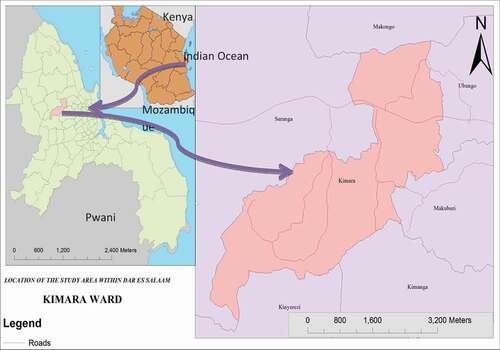

Kimara ward is an area located at coordinates 6°47′42″S 39°15′58″E, within Ubungo Municipality in Dar es Salaam city () with a total area of 13.76 km2 and a population of 94,955 residents and 23,159 households (2018 estimated population based on 2012 census growth rate). The ward has about six sub-wards. The study was undertaken in two sub-wards namely Kimara Baruti and Kilungure A. These were randomly selected to represent the remaining sub-wards. The total number of households in the sub-wards is estimated to be 5046. The housing pattern is irregular and the mode of lease is multiple tenants per house (average of three households per house), therefore a total of 1682 houses were included in the study.

High population density and topographical considerations were among the factors for choice of this case study area. High population suggest high waste generation rates and more pronounced waste management problems, while topography has implication on the operational activities related to waste management. It was learnt that Kimara has an undulating terrain such that movement of pollutants from high to low elevation is possible. The main land use category is residential but within the area informal urban agriculture is also practiced. The main source of income is engagement in small scale business and employment in both formal and informal sectors.

2.2 Data collection and analysis

The study employed four data collection methods which are interviews, household surveys, waste measurements and field visits to the recycling centers. Interviews (60 sessions) were meant to track the existing knowledge from the purposively selected key informants that included the community leaders and waste recyclers. A sample of 60 was achieved as there was no new information that could be derived beyond that level and this was considered a point of data saturation. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to obtain information pertaining to the practice, challenges and factors affecting waste separation and recycling. Second, a survey of 200 (which is 12% of the houses in the selected sub-wards) systematically randomly selected (k = 4) houses in Kimara (selected two sub-wards) was undertaken using a structured questionnaire to collect information on household-level practices, challenges and attitudes on waste management. The sample size for survey was considered adequate to depict the real situation as the household characteristics are almost homogenous.

The reported information was substantiated with site observations where waste storage, accumulation and handling at site were tracked. Surveys were meant to track the practice and obtain a quantifiable estimate that represents the rest of the households. Additionally, a separate survey of 300 (the 200 houses mentioned above plus additional 100 houses) was made to determine the resident’s preferences with series of choice experiment. The choice experiment was meant to understand the perception on what would make a change with regard to segregation. Thirdly, measurements of waste streams at 80 (randomly selected) houses were done to understand the generation and composition of waste and the potential for recycling and recovery. To achieve this, houses were provided with plastic bags for waste collection and thereafter, the volumes and weights were measured. To obtain the weights and volumes of individual constituents (organic food waste, glass, plastics, paper, pampers, electronic wastes, textiles, metal/tins, aluminium, sweepings and ashes) of waste were sorted. Measurements were meant to detect changes in terms consumption and production that might have been affected by the known municipal waste composition range of values. Fourthly, a field visit to an informal recycling centers (n = 4) to collect information on the daily volume, composition, and price of recyclables was made. Daily records of the recyclables from the centers were collected, organized and analyzed. This exercise was done to learn of the factors influencing the informal recycling practice in relation to the household practices. The use of multiple methods for data collection was meant to ensure all the possible contradictions are well understood (Phellas et al., Citation2011).

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20, whereby descriptive analysis (comparison of data from of the survey data) was done. The information collected through interviews was analyzed using content analysis technique whereby unit and categories were set, coded and thereafter themes identified. Secondary information obtained from the collection centre was computed to obtain compositions and thereafter a comparative analysis was done.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Waste generation and composition

The average solid waste generation rate for Kimara was established to be 0.53 Kg/capita/day (n = 470, sd 0.26). This slightly exceeds the rates for Dar es Salaam city (0.4 Kg/capita/day) reported in the previous literature (Kaseva & Mbuligwe, Citation2005; Oberlin, Citation2013). This difference may reflect increased waste generation as the community members improve living standards and experience changes in consumption lifestyle (Abd’razack et al., Citation2013; Strahl, Citation2003).

In terms of the waste composition, food waste constitutes the highest composition value by weight, volume and density (). This is in agreement with the composition values of waste from previous studies especially for organic waste (Mbuligwe et al., Citation2002; Mgimba & Sanga, Citation2016). However there is a slight deviation for composition values of other types of waste such as papers and plastics. The difference may be attributed by in the type of economic activities, changes in lifestyle as well as the presence of informal recycling practice that may reduce amount of recyclables from the waste stream. With regard to waste composition, the unique observation was the presence of baby pampers and diapers. This is explained by the changes in lifestyle whereby the use of diapers and pampers in now gaining interest in most DC.

Table 1. Household solid waste average composition values for Kimara, Dar es Salaam

This type of waste is of interest because it demands special attention with regard to its disposal (Khoo et al., Citation2019). Field observation indicated that pampers and diapers were both handled and disposed of in unhygienic manner such that the public may face high public health risk from fecal contamination via direct personal contact, contact with contaminated soil and water ingestion (Jesca & Junior, Citation2015). Recyclables (aluminum/tins/metals, plastics) are part of the composition suggesting that they are mixed at source with other types of waste than being collected for recycling purposes. According to the results, if all the recyclables are effectively segregated for reuse and recycling, volume of waste would be reduced by more than 65%. But this is not realized because the current practice of mixing all the waste precludes this.

3.2 Solid waste segregation, reuse and recycling

There is no segregation of waste in Kimara but RRR takes place informally at different levels. The potential recyclables or recoverable waste components as reported in the interviews include food waste among others (e.g. plastics, metals, electronic waste). Results show that about 35% of the respondents indicated to reuse the recoverable waste (food waste) for feeding animals and other reuse purposes, 34% would give freely to waste pickers and only 20% would sell to waste collectors asTable indicated in . A significant proportion of recyclables was observed to be freely given to recyclers which suggest that recycling business is non-economically viable and community members do not consider selling recyclables as an important source income. Therefore, waste recycling was affected by both the community’s perceived value of recyclables and the practice of mixing all waste components.

Table 2. Handling of the recyclables at households in Kimara

These findings shows that composition of household waste is amenable to a substantial amount of resource recovery, that is re-use, recycling and recovery (Oberlin, Citation2013). However, despite the potential for nutrient and energy recovery from organic waste, none of the respondents indicated to have invested on resource recovery such as production of biogas. Therefore, the potential of organic waste as a source for nutrient and energy (Idowu et al., Citation2017; Kjerstadius et al., Citation2015; Uçkun Kiran et al., Citation2014) is not fully exploited probably due to lack of technology and awareness.

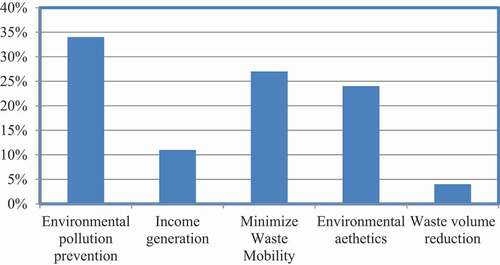

Despite the fact that waste is not segregated, recycling is to some extent informally practiced through waste pickers-recyclers route whereby recyclables are picked by waste pickers and sold to the recyclers. Community members are involved in the recycling chain through either picking or allowing waste pickers to sell the recyclables. represents the motives of the community members to undertake waste recycling. Results show that community members resort to do recycling for pollution prevention purposes (34% of the respondents), reduced waste mobility from one household to another (27% of the respondents), income generation (11% of the respondents) and environmental aesthetics (24% of the respondents). While it is expected that recycling for income generation would be the motivation factor for low-income earners (Asibey et al., Citation2020), it seems that the sense of commitment to prevent pollution overrides all the factors. This is consistent with findings from studies conducted in Malasyia and Ethiopia where by intrinsic motivation and individual commitments were highlighted as the main motivational factors (Aini et al., Citation2002; Tadesse, Citation2009). The finding is also more or less similar and inconsistent with a study conducted in China whereby strong social network had an influence on the waste segregation behavior (Ling et al., Citation2021).

Considering the reasons as to why people do not segregate their waste, high cost for installation and lack of facilities and equipment, low volumes of recyclabl; and lack of awareness were mentioned (). This finding is similar to those reported in other countries, for example, (Otitoju & Seng, Citation2014) and (Desa et al., Citation2011) in Malaysia (Banga, Citation2011), in Uganda (Babaei et al., Citation2015), in Iran (Macawile & SiaSu, Citation2009), in the Philippines, and (Malik et al., Citation2015) in India. Although scholars in Tanzania do not provide reasons for not segregating, the available literature indicates that there is negative attitude towards segregation (Mbuligwe et al., Citation2002). This is confirmed with findings from this study whereby 22% of the respondents indicated to be unaware. The guideline for SWM in Tanzania tasks a household to ensure that they manage waste from generation points to the transfer station where the waste is collected and hauled to the disposal sites. In this regard provision of facilities for waste segregation which is entirely a responsibility of the households. Therefore management of waste at household level is entirely a responsibility of the respective members with the exception of raising awareness and enforcement of laws which are entrusted on the local government.

Table 3. (a) Reasons for non-segregation of HSW; (b) residents’ attitudes on items to promote waste segregation; (c) source segregation choice experiments: Kimara Ward

displays Kimara residents’ perception on changes that might promote waste segregation in the ward. The figures in column 2 represent the percentage of survey respondents who agree, strongly agree, or very strongly agree that the item listed in column 1 “may promote solid waste segregation at the source (in your household).” More Kimara households (84% of the respondents) agree that provision of physical items to facilitate segregation—specifically bags and bins—would promote segregation than would waste management modifications such as changes on the frequency of collection or the way waste collection charges are judged. A large percentage (72% of respondents) also agrees that providing returns of revenues from waste recovery to households would increase household segregation. For example, several physical facilities that might improve waste segregation identified in represent an attribute important to waste segregation. Most residents indicated that they agreed that the free provision of bins may promote waste segregation in household. This is in agreement with findings reported by Kumar & Nandini (Citation2013), Norkhadijah et al. (Citation2014) and Sin-Yee & Sheau-Ting (Citation2016). Two-thirds agreed that neighborhood collection points may promote such segregation. These constitute two different levels of the physical facility attribute. Neither free bins nor neighborhood collection represents a third level of the attribute. No one would prefer that level by itself, but some may accept it as part of a package of interventions if the other interventions were favorable. For instance, the potential to earn financial returns from waste segregation and recycling represents the revenue attribute. This revenue could be returned to the household (which 72% of households favor) or returned to the local government (which only 41% of residents favor). These two possibilities represent two levels of the revenue attribute. In addition, the third level of the revenue attribute could be “no revenue” either to the resident or to the local government. Some residents may prefer a package of interventions with no distribution of revenue if it brought good facilities to the household or neighborhood compared to a package that brought no facilities or the wrong kind of facilities. Others may prefer a package with no facilities if it also brought revenue.

Survey choice experiments present different hypothetical packages of attributes and different levels of these attributes, and ask respondents to select the alternative packages they most prefer. Respondents cannot cherry-pick the attribute levels they most prefer in each experiment—the best revenue and best facility in the above example—but instead must choose among the alternative combinations each experiment offers. By presenting multiple experiments with different combinations of attribute levels, recording the choice in each experiment, and analyzing the responses with a conditional logit statistical model (Louviere et al., Citation2000);, one can estimate the relative importance respondents place on each attribute.

displays the output from the statistical analysis. The categorical attributes in column 1 are modeled with a weighted coded-effect approach, which allows inclusion of all levels of each categorical variable instead of omitting the level for each attribute that serves as the respective base case as is done in a more typical approach using dummy variables; that is, the weighted approach allows reporting of coefficients for each of the levels presented in the bottom four attributes of (te Grotenhuis et al., Citation2017; Louviere et al., Citation2000; F. R. Johnson et al., Citation2006; Viney et al., Citation2002). The second column presents the odds-ratios for the independent variables. These capture the change in the likelihood of choosing an alternative as the value of a variable changes, holding other variables constant. Thus, an odds ratio below 1.0 for a particular variable indicates a lower likelihood of choosing an alternative with higher levels of that variable (negative relationship) and those above 1.0 a higher likelihood (positive relationship). The respective logit coefficients appear in column 3 (they equal the natural log of the respective odds-ratio). The fourth column reports the statistical significance of each odds-ratio/logit coefficient.

Starting at the top of , the cost-collect attribute exhibits a value of 0.5, confirming an obvious dislike of higher monthly costs of collection (remembering that the cost-collect attribute appears in the model in units of thousands of Tanzania shillings). The next three items represent the levels of the frequency of waste collection attribute, with only the low frequency (waste collection two times/month) marginally significant at the 0.1 level. The 0.83 odds-ratio for collectfreq-2 indicates a dislike of low frequency waste collection. The two levels of the penalty attribute also appear only marginally significant at the 0.1 level, with the 0.92 odds-ratio for the penalty-low level indicating an aversion to lower penalties in favor of higher penalties represented by penalty-high, a counterintuitive result possibly reflecting a belief that higher penalties will motivate neighbors to separate the waste. All of the levels of the revenue attribute appear highly significant. The dislike of sharing revenues with the household or mtaa (sub ward) (revenue-household and revenue-govt) results from the framing of the choice experiments, where revenue-none represents the status quo. This echoes related work (Wernstedt et al., Citation2019) that has found that a large proportion of households in Dar es Salaam indicate a preference for the status quo, an important risk averting strategy that will complicate any intervention in waste collection that depends on changing respondents’ behavior. Finally, the three levels of the facilities attribute appearing at the bottom of appear statistically significant at the 0.01 level, suggesting that residents favor the provision of bins and neighborhood collection points (facilities-bin and facilities-neighbor) and dislike the lack of incentives (facilities-none).

The regression results in also allow estimation of both the relative priority of specific characteristics of the waste collection and source segregation system compared to other characteristics and the economic value that individuals place on those characteristics. For the former, the relative ratio of regression coefficients (not the ratio of the odds-ratios appearing in , but rather the ratio of the regression coefficients in column 3 from which the odds-ratios are calculated) reveals their relative weighting. For instance, offering segregation bins to increase segregation has about the same priority as establishing neighborhood collection points at which residents can deposit separated material, and each appears more than ten times as important as instituting a low penalty to encourage segregation. The ratio of the logit coefficient for any attribute level to the logit coefficient for the cost attribute indicates the economic value of that attribute level in thousands of Tanzania shillings. Thus, receiving segregation bins offers an equivalent economic value of 2,850 TSh/month. In addition, cutting waste collection to two collections per month has an equivalent economic cost of almost 300 TSh/month.

3.3 Potential for waste recycling and resource recovery

Informal recycling centers situated along the main trunk road were observed during the fieldworks. The normal practice is that, recyclables from households and undesignated dumping sites are collected by waste pickers and sold to the recycling centers (who act as middlemen in this business), who eventually sells them to the recyclers (Industries). The recycling centers by middlemen are unregistered and the business is informal. At the surveyed centers, the type, amount and price for selling the waste are recorded in .

Table 4. Practice on recyclables at the collection centers

Results indicate that a total of 333.5 kg is collected each day at the centers (collected by middlemen). This weight is higher than expected () especially when food waste is not collected at the centers and is not part of the recorded weight. This may have been attributed by the contribution of recyclables from neighboring wards other than Kimara as the business is not restricted to the ward. The recycling centers by middlemen are located along a main road providing easy access through all means of transport. Records for recyclable from the centers, shows that steel, plastics bottles and batteries are the components with relatively higher composition by weight while brass, copper and radiators have relatively higher prices. Food waste does not appear in the composition at the centers because in most cases is reused at household level for animal feeding (). These findings are less similar to those reported by Oberlin (Citation2013), who indicated that food waste was the most potential waste category for recycling. Comparing the amount of recyclables with Kinondoni another part of the Dar es Salaam city, the findings are similar for the aluminum composition (1.5% in Kimara versus 2.3% in Kinondoni) and dissimilar for the plastics (28.9% in Kimara than 9.67% in Kinondoni). Despite this situation, findings from the recycling centers suggest that there is higher potential for recycling. This fact is substantiated by another finding in Mexico where waste potential for recycling was 65% (Armijo De Vega et al., Citation2008). This potential for recycling together with the other two Rs needs to be harnessed so that RRR is effectively realized.

Interviews with government officials revealed that one of the factors affecting RRR in Dar es Salaam is lack of strategies. Literature highlights the importance of adequate strategies to promote the practice (Wichai-utcha & Chavalparit, Citation2019). The potential of RRR can be enhanced with increased economic incentives, increased awareness, better coordinated legislation and improved institutional arrangements, adequate enforcement and more effective promotion strategies. Abila (Citation2018), Shaw and Maynard (Citation2008), and Yau (Citation2010) stress on the importance of collective action and role of economic incentive in waste management; Banga (Citation2011) emphasizes on the importance of increased awareness and sense of ownership for waste segregation to be integrated in the management chain; and Otitoju and Seng (Citation2014) highlights on the need for effective policies and legislation coupled with adequate enforcement. All these suggest a need for effective governance in waste management.

3.4 Policy framework on solid waste segregation

Waste management is guided by the Local Government Act of 1982, Section 55, and the Environment Management Act of 2004 whereby Local Governments are given the mandate and responsibility to manage waste. This includes provision of facilities for management and ensuring that there is favorable environment for the stakeholders (private sector, NGOs, producers, vendors and transporters) involved in waste management. The Local Government is also mandated to establish bylaws to ensure smooth operation and management in their areas of jurisdiction. The central government through the Vice President’s office (Division of Environment) is responsible for the formulation of policies and regulations as well as for providing guidance to the Local Government.

Waste management is also guided by the Public Health Act, 2009 which links the Ministry of Health to the issue of waste management. Despite the presence of clear policies to govern the management of waste (including RRR), there are challenges on implementation. Interviews with the Government officials established that lack of resources, weak coordination among various actors are among the hindering factors for successful implementation (Abd Manaf et al., Citation2009; Buenrostro & Bocco, Citation2003; Shekdar, Citation2009; Zurbrugg, Citation2002). Although most of the Municipal and District Councils have enacted bylaws to provide specific directives and penalties, the challenge remains to be lack of adequate enforcement. This is consistent with scholarly findings by (Jha et al., Citation2011; Periathamby et al., Citation2009) who also highlighted on lack of enforcement as an obstacle to effective waste management.

Guidance on waste segregation and use of separate collection containers are well stipulated in the Environmental Management Act, 2004. In addition, the Hazardous Waste Management Regulation (2009) mandates the local authorities to ensure adequate and appropriate segregation and recycling facilities as well as training and adequate provision of personal protective gears. However in this study, it was observed that, few of the surveyed households in the study area had containers for waste segregation which suggests weakness in the enforcement of the regulations as pointed above.

To support the implementation of the policies and regulations and attain sustainable waste management (including RRR), several strategies have been attempted. In 1998, the Ministry of Health established sanitation and cleanliness competitions for municipal and town councils to encourage proper waste management practices by providing rewards for best performers. However, inadequate resources have limited the effectiveness of this initiative. In addition, reforms to the management cycle have been sought and currently there is an interest in public private partnerships where the aim is to bring the private sector into a more active role in the SW management chain, including the collection, recycling and disposal of waste. Despite the existence of the public private partnership policy since 2010, its implementation continues to face challenges and inadequate operationalization.

With regard to hazardous waste management, the country has a guideline that provides principles for governing source segregation, with a special emphasis on hazardous waste. But the translation of the guideline into actual practice is yet to be realized. Ineffectiveness in management of hazardous waste suggests high public health risks and environmental problems associated with poor waste management. In Tanzania, waste segregation is inadequately reinforced at all stages starting from the household, collection to disposal. As revealed in the interviews, major issues that need urgent attention are inefficient coordination among various actors, financial constraints, lack of capacity, poor accessibility and poor governance.

4 Conclusion

Waste RRR in Dar es Salaam and Tanzania in general is affected by inadequate segregation at all levels of the management chain. Despite the huge potential, RRR remains untapped. As a result, efforts towards effective waste management involving sustainable resource recovery become unfruitful. Literature suggest that tapping this potential could lead to income generation, reduced cost for handling waste, a cleaner, healthier natural environment and improved aesthetics. As pointed out in this article, negative attitude towards waste segregation; perceived high cost for segregation facilities and lack of awareness on waste segregation are among the factors affecting segregation practice. Lack of effective policies and guideline, lack of effective strategies and inadequate enforcement are considered to be the main challenges associated with the governance support. These factors need a thorough analysis and consideration for effective RRR scale up. Similarly, it is essential to incorporate the community perceptions on what they think would be done to enhance waste segregation. In this article it has been pointed out that, provision of free waste collection bins; availing financial returns to the community members from recycling business; and establishment of low penalties for noncompliance would help in promoting waste segregation behavior. Although some of these might not work, they are useful inputs towards establishment of sustainable strategies.

Promotion of waste segregation and recycling practices requires proper policies and guidelines and their adequate enforcement. Policy options that include provision of economic incentives for reuse and recycling as highlighted by scholars, would also suit the purpose (Boonrod et al., Citation2015; Yau, Citation2010). Therefore, transformations in the management cycle need to start with policy reviews to incorporate policy options related to promotion and formalization of recycling practice and provision of economic incentives. Formalization and proper coordination of all actors at all levels, enhancing the quality of education through tailor made curriculums, are some of the essential ingredients for effective waste management.

Competing interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Solid waste management remains a challenge in many developing countries. Despite the extensive research that have been undertaken, there is limited knowledge on the factors affecting waste segregation at source and the locally informed strategies for its enhancement. Findings indicate that lack of awareness, financial constraints, inadequate enforcement of policies and inadequate promotion strategies are among the hindering factors. Community perspectives on what could be done revealed that provision of facilities for waste segregation and financial returns to the community from the recycling business would promote waste segregation and recycling. Formulation of strategies to formalize and mainstreame RRR into training programmes and operationalization of adequate enforcement mechanisms are some of the recommended policy actions

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jacob M. Kihila

Jacob Kihila is an Environmental Engineer with a PhD in Environmental Science and Engineering. He is a Registered Professional Environmental Engineer and Registered Environmental expert (EIA and Audit) with more than 16 years of experience in the field of water and sanitation and environmental management. He has particular skills in projects design, planning and management; design and construction of water and sanitation facilities; water quality monitoring and pollution control; environmental management plans, environmental impact assessments (EIAs); community facilitation and mobilizations; capacity building; participatory rural appraisal methods. His areas of specialization include water and sanitation, water and wastewater treatment; environmental assessments, disaster management and climate change.

His areas of research include water reuse, affordable sanitation technologies, water and wastewater treatment, resources recovery from waste and wastewater.

References

- Abd Manaf, L., Samah, M. A. A., & Zukki, N. I. M. (2009). Municipal solid waste management in Malaysia: Practices and challenges. Waste Management, 29(11), 2902–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2008.07.015

- Abd’razack, N., Ludin, A., & Umaru, E. (2013). Ecological footprint, lifestyle and consumption pattern in Nigeria. American-Eurasian Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Science, 13(4), 425–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2013.13.04.1943

- Abila, B. (2018). Households’ perception of financial incentives in endorsing sustainable waste recycling in Nigeria. Recycling, 3(2), 28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling3020028

- Agbefe, L. E., Lawson, E. T., & Yirenya-Tawiah, D. (2019). Awareness on waste segregation at source and willingness to pay for collection service in selected markets in Ga West Municipality, Accra, Ghana. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 21(4), 905–914. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-019-00849-x

- Aini, M. S., Fakhru’l-Razi, A., Lad, S. M., & Hashim, A. H. (2002). Practices, attitudes and motives for domestic waste recycling. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 9(3), 232–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500209470119

- Al-Maaded, M., Madi, N., Kahraman, R., Hodzic, A., & Ozerkan, N. (2012). An overview of solid waste management and plastic recycling in Qatar. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 20(1), 186–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-011-0332-2

- Al-Salem, S. M., Lettieri, P., & Baeyens, J. (2009). Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): A review. Waste Management, 29(10), 2625–2643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2009.06.004

- Armijo De Vega, C., Ojeda Benítez, S., & Ramírez Barreto, M. E. (2008). Solid waste characterization and recycling potential for a university campus. Waste Management, 28(1), S21–S26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2008.03.022

- Asibey, M. O., Lykke, A. M., & King, R. S. (2020). Understanding the factors for increased informal electronic waste recycling in Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2020.1755016

- Babaei, A. A., Alavi, N., Goudarzi, G., Teymouri, P., Ahmadi, K., & Rafiee, M. (2015). Household recycling knowledge, attitudes and practices towards solid waste management. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 102, 94–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.06.014

- Babazadeh, T., Nadrian, H., Mosaferi, M., & Allahverdipour, H. (2020). Challenges in household solid waste separation plan (HSWSP) at source: A qualitative study in Iran. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(2), 915–930. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0225-9

- Banga, M. (2011). Household knowledge, attitudes and practices in solid waste segregation and recycling: The case of urban Kampala. Zambia Social Science Journal, 2(1), 4. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/zssj/vol2/iss1/4/

- Batool, S. A., Chaudhry, N., & Majeed, K. (2008). Economic potential of recycling business in Lahore, Pakistan. Waste Management, 28(2), 294–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2006.12.007

- Bing, X., Bloemhof, J. M., Ramos, T. R. P., Barbosa-Povoa, A. P., Wong, C. Y., & van der Vorst, J. G. (2016). Research challenges in municipal solid waste logistics management. Waste Management, 48, 584–592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2015.11.025

- Boonrod, K., Towprayoon, S., Bonnet, S., & Tripetchkul, S. (2015). Enhancing organic waste separation at the source behavior: A case study of the application of motivation mechanisms in communities in Thailand. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 95(3), 77–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.12.002

- Buenrostro, O., & Bocco, G. (2003). Solid waste management in municipalities in Mexico: Goals and perspectives. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 39(3), 251–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-3449(03)00031-4

- Chi, X., Streicher-Porte, M., Wang, M. Y., & Reuter, M. A. (2011). Informal electronic waste recycling: A sector review with special focus on China. Waste Management, 31(4), 731–742. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.11.006

- Da Cruz, N. F., Ferreira, S., Cabral, M., Simões, P., & Marques, R. C. (2014). Packaging waste recycling in Europe: Is the industry paying for it? Waste Management, 34(2), 298–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2013.10.035

- Darby, L., & Obara, L. (2005). Household recycling behaviour and attitudes towards the disposal of small electrical and electronic equipment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 44(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2004.09.002

- Desa, A., Kadir, N. B. Y. A., & Yusooff, F. (2011). A study on the knowledge, attitudes, awareness status and behaviour concerning solid waste management. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 18, 643–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.05.095

- Donnini Mancini, S., Rodrigues Nogueira, A., Akira Kagohara, D., Saide Schwartzman, J. A., & de Mattos, T. (2007). Recycling potential of urban solid waste destined for sanitary landfills: The case of Indaiatuba, SP, Brazil. Waste Management & Research, 25(6), 517–523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242x07082113

- Falk, R. H., & McKeever, D. B. (2004, 22-24 April). RECOVERING WOOD FOR REUSE AND RECYCLING A UNITED STATES PERSPECTIVE. Paper presented at the MANAGEMENT OF RECOVERED WOOD RECYCLING, BIOENERGY AND OTHER OPTIONS, Thessaloniki.

- Gyimah, P., Mariwah, S., Antwi, K. B., & Ansah-Mensah, K. (2019). Households’ solid waste separation practices in the Cape Coast Metropolitan area, Ghana. GeoJournal, 4, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-10084-4

- Idowu, I., Li, L., Flora, J. R., Pellechia, P. J., Darko, S. A., Ro, K. S., & Berge, N. D. (2017). Hydrothermal carbonization of food waste for nutrient recovery and reuse. Waste Management, 69, 480–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.08.051

- Jeffrey, C. (2011). Construction and demolition waste recycling: A literature review. Dalhousie University’s Office of Sustainability, 35.

- Jesca, M., & Junior, M. (2015). Practices regarding disposal of soiled diapers among women of child bearing age in poor resource urban setting. Journal of Nursing & Health Sciences, 4(4), 63–67.

- Jha, A. K., Singh, S., Singh, G., & Gupta, P. K. (2011). Sustainable municipal solid waste management in low income group of cities: A review. Tropical Ecology, 52(1), 123–131. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/34213609.pdf

- Johnson, F. R., Kanninen, B., Bingham, M., & Özdemir, S. (2006). Experimental design for stated-choice studies. In Valuing environmental amenities using stated choice studies Editor Name is Barbara J. Kanninen. (pp. 159–202). Springer.

- Johnson, K. M., González, M. L., Dueñas, L., Gamero, M., Relyea, G., Luque, L. E., & Caniza, M. A. (2013). Improving waste segregation while reducing costs in a tertiary-care hospital in a lower–middle-income country in Central America. Waste Management & Research, 31(7), 733–738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X13484192

- Kang, H.-Y., & Schoenung, J. M. (2005). Electronic waste recycling: A review of U.S. infrastructure and technology options. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 45(4), 368–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2005.06.001

- Kaseva, M. E., & Mbuligwe, S. E. (2005). Appraisal of solid waste collection following private sector involvement in Dar es Salaam city, Tanzania. Habitat International, 29(2), 353–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2003.12.003

- Khoo, S. C., Phang, X. Y., Ng, C. M., Lim, K. L., Lam, S. S., & Ma, N. L. (2019). Recent technologies for treatment and recycling of used disposable baby diapers. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 123, 116–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2018.12.016

- Kjerstadius, H., Haghighatafshar, S., & Davidsson, Å. (2015). Potential for nutrient recovery and biogas production from blackwater, food waste and greywater in urban source control systems. Environmental Technology, 36(13), 1707–1720. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2015.1007089

- Kumar, A., Holuszko, M., & Espinosa, D. C. R. (2017). E-waste: An overview on generation, collection, legislation and recycling practices. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 122, 32–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.01.018

- Kumar, B. S., Varalakshmi, N., Lokeshwari, S. S., Rohit, K., & Sahana, D. (2017). Eco-friendly IOT based waste segregation and management. Paper presented at the 2017 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT). Mysuru, India.

- Kumar, M., & Nandini, N. (2013). Community attitude, perception and willingness towards solid waste management in Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 4(1), 87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160764

- Kumar, S., Smith, S. R., Fowler, G., Velis, C., Kumar, S. J., Arya, S., Rena, K. R. Cheeseman, C. (2017). Challenges and opportunities associated with waste management in India. Royal Society Open Science, 4(3), 160764. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160764

- Li, J., Yang, J., & Liu, L. (2015). Development potential of e-waste recycling industry in China. Waste Management & Research, 33(6), 533–542. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242x15584839

- Ling, M., Xu, L., & Xiang, L. (2021). Social-contextual influences on public participation in incentive programs of household waste separation. Journal of Environmental Management, 281, 111914. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111914

- Louviere, J. J., Hensher, D. A., & Swait, J. D. (2000). Stated choice methods: Analysis and applications. Cambridge university press.

- Macawile, J., & SiaSu, G. (2009). Local government officials perceptions and attitudes towards solid waste management in Dasmarinas, Cavite, Philippines. Journal of Applied Sciences in Environmental Sanitation, 4(1), 63–69. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/44003980_LOCAL_GOVERNMENT_OFFICIALS_PERCEPTIONS_AND_ATTITUDES_TOWARDS_SOLID_WASTE_MANAGEMENT_IN_DASMARINAS_CAVITE_PHILIPPINES

- Maletz, R., Dornack, C., & Ziyang, L. (2018). Source separation and recycling. Springer.

- Malik, N. K. A., Abdullah, S. H., & Manaf, L. A. (2015). Community participation on solid waste segregation through recycling programmes in Putrajaya. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 30, 10–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2015.10.002

- Matsumoto, S. (2011). Waste separation at home: Are Japanese municipal curbside recycling policies efficient? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 55(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.10.005

- Matter, A., Dietschi, M., & Zurbrügg, C. (2013). Improving the informal recycling sector through segregation of waste in the household – The case of Dhaka Bangladesh. Habitat International, 38, 150–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.06.001

- Mbuligwe, S., Kassenga, G., Kaseva, M. E., & Chaggu, E. J. (2002). Potential and constraints of composting domestic solid waste in developing countries: Findings from a pilot study in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 36(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-3449(02)00009-5

- Mgimba, C., & Sanga, A. (2016). Municipal solid waste composition characterization for sustainable management systems in Mbeya City, Tanzania. International Journal of Science, Environment and Technology, 5(1), 47–58. https://www.ijset.net/journal/834.pdfNotStartedCompletedRejected

- Norkhadijah, S. S., Mariah, H. H., Irniza, R., & Emilia, Z. (2014). Commitment, attitude and behavioural changes of the community towards a waste segregation program: A case study of Malaysia. Waste Management Environment VII, 180, 137–148.

- Oberlin, A. S. (2013). Resource recovery potential: A case study of household waste in Kinondoni municipality, Dar es Salaam. TaJONAS: Tanzania Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences, 4(1), 563–574.

- Otitoju, T. A., & Seng, L. (2014). Municipal solid waste management: Household waste segregation in Kuching South City, Sarawak, Malaysia. American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER), 3(6), 82. http://www.ajer.org/papers/v3(6)/K0368291.pdf

- Periathamby, A., Hamid, F. S., & Khidzir, K. (2009). Evolution of solid waste management in Malaysia: Impacts and implications of the solid waste bill, 2007. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 11(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-008-0231-3

- Phellas, C. N., Bloch, A., & Seale, C. (2011). Structured methods: Interviews, questionnaires and observation. Researching Society and Culture, 3, 181–205.

- Rajkamal, R., Anitha, V., Nayaki, P. G., Ramya, K., & Kayalvizhi, E. (2014). A novel approach for waste segregation at source level for effective generation of electricity—GREENBIN. Paper presented at the 2014 International Conference on Science Engineering and Management Research (ICSEMR). Chennai, India.

- Saphores, J.-D. M., Ogunseitan, O. A., & Shapiro, A. A. (2012). Willingness to engage in a pro-environmental behavior: An analysis of e-waste recycling based on a national survey of U.S. households. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 60, 49–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2011.12.003

- Shaw, P. J., & Maynard, S. J. (2008). The potential of financial incentives to enhance householders’ kerbside recycling behaviour. Waste Management, 28(10), 1732–1741. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2007.08.008

- Shekdar, A. V. (2009). Sustainable solid waste management: An integrated approach for Asian countries. Waste Management, 29(4), 1438–1448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2008.08.025

- Sin-Yee, T., & Sheau-Ting, L. (2016). Attributes in fostering waste segregation behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, 7(9), 672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18178/ijesd.2016.7.9.860

- Skinner, A., Dinter, Y., Lloyd, A., & Strothmann, P. (2010). The challenges of E-Waste Management in India: Can India draw lessons from the EU and the USA. Asien, 117(7), 26. http://asien.asienforschung.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2014/04/ASIEN_117_Skinner-Dinter-Llyod-Strothmann.pdf

- Stoeva, K., & Alriksson, S. (2017). Influence of recycling programmes on waste separation behaviour. Waste Management, 68, 732–741. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.06.005

- Strahl, H. (2003). Cultural interpretations of an emerging health problem: Blood pressure in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Anthropology & Medicine, 10(3), 309–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1364847032000133834

- Suttibak, S., & Nitivattananon, V. (2008). Assessment of factors influencing the performance of solid waste recycling programs. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 53(1–2), 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.09.004

- Tadesse, T. (2009). Environmental concern and its implication to household waste separation and disposal: Evidence from Mekelle, Ethiopia. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 53(4), 183–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.11.009

- te Grotenhuis, M., Pelzer, B., Eisinga, R., Nieuwenhuis, R., Schmidt-Catran, A., & Konig, R. (2017). When size matters: Advantages of weighted effect coding in observational studies. International Journal of Public Health, 62(1), 163–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0901-1

- Troschinetz, A. M., & Mihelcic, J. R. (2009). Sustainable recycling of municipal solid waste in developing countries. Waste Management, 29(2), 915–923. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2008.04.016

- Uçkun Kiran, E., Trzcinski, A. P., Ng, W. J., & Liu, Y. (2014). Bioconversion of food waste to energy: A review. Fuel, 134, 389–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.05.074

- Viney, R., Lancsar, E., & Louviere, J. (2002). Discrete choice experiments to measure consumer preferences for health and healthcare. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 2(4), 319–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2.4.319

- Wernstedt, K., Kihila, J. M., & Kaseva, M. (2019). Biases and environmental risks in urban Africa: Household solid waste decision-making. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1691510

- Wichai-utcha, N., & Chavalparit, O. (2019). 3Rs Policy and plastic waste management in Thailand. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 21(1), 10–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-018-0781-y

- Wilson, D. C., Velis, C., & Cheeseman, C. (2006). Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat International, 30(4), 797–808. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.09.005

- Yau, Y. (2010). Domestic waste recycling, collective action and economic incentive: The case in Hong Kong. Waste Management, 30(12), 2440–2447. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.06.009

- Yu, J., Williams, E., Ju, M., & Shao, C. (2010). Managing e-waste in China: Policies, pilot projects and alternative approaches. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 54(11), 991–999. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.02.006

- Zhang, K., Schnoor, J. L., & Zeng, E. Y. (2012). E-Waste Recycling: Where Does It Go from Here? Environmental Science & Technology, 46(20), 10861–10867. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1021/es303166s

- Zurbrugg, C. (2002). Urban solid waste management in low-income countries of Asia how to cope with the garbage crisis. Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, 1–13.